Introduction

Breast cancer remains one of the most prevalent

malignancies among women globally, with triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC) representing one of its most aggressive and

therapeutically challenging subtypes (1). TNBC accounts for approximately 15–20%

of breast cancer cases and is defined by the lack of expression of

estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (2,3). This

subtype is more commonly observed in younger women, particularly

those under 40 years of age, and is frequently associated with

early recurrence and high metastatic potential (3,4).

Patients with TNBC often face significant physical

and psychological burdens during treatment, including fatigue,

hepatic dysfunction, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Supportive

strategies, such as the administration of melatonin and silymarin,

have shown beneficial effects in reducing chemotherapy-related

fatigue and toxicity (5,6). Psychological support with agents like

crocin has also been effective in mitigating distress associated

with treatment (7). In parallel,

biological markers such as cytokeratin 18 (CK18) are under

investigation as indicators of therapeutic response, helping to

personalize treatment regimens (8).

Eribulin mesylate (Halaven®), a synthetic

analog of the natural product halichondrin B, functions as a

microtubule dynamics inhibitor and has been approved for use in

patients with advanced breast cancer (9,10).

Pivotal trials such as EMBRACE (11) and Study 301 (12) have demonstrated its clinical benefit

in metastatic breast cancer, particularly among patients previously

treated with anthracycline and taxane-based regimens.

Notably, its effectiveness may be improved when used

in combination with other agents. Its efficacy may improve when

combined with synergistic agents.

Cisplatin, a platinum-based compound, induces

cytotoxicity primarily through DNA crosslinking and inhibition of

DNA repair, resulting in tumor cell apoptosis. Although it is an

established agent in TNBC therapy, its use is often constrained by

its dose-limiting toxicities (13,14).

Nevertheless, platinum-based regimens continue to hold relevance in

TNBC treatment, with recent clinical guidelines recommending

carboplatin-taxane combinations as a neoadjuvant option for

HER2-negative and TNBC cases (15,16).

In our previous investigation (17), we demonstrated the synergistic

cytotoxic potential of eribulin combined with cisplatin in TNBC

models. Building upon those findings, the present study explores

the mechanistic basis of this synergy, particularly its

relationship with autophagy-a regulated cellular process

increasingly implicated in tumor progression and therapeutic

resistance. Given the therapeutic promise of targeting autophagy in

TNBC, we hypothesized that dual treatment with eribulin and

cisplatin could potentiate antitumor effects by modulating this

pathway.

Moreover, in light of global disparities in access

to advanced cancer therapies, particularly in low- and

middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a pressing need to

develop cost-effective treatment strategies. The use of existing,

clinically approved drugs with known safety profiles, such as

eribulin and cisplatin, offers a pragmatic avenue for broadening

treatment access and improving outcomes in resource-constrained

settings (18).

Taken together, these considerations highlight the

urgent need for treatment strategies that combine mechanistic

efficacy with cost-effectiveness, particularly in the management of

TNBC.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

All cell culture reagents, including Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and

penicillin/streptomycin, were sourced from HyClone (GE Healthcare

Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA). Trypsin-EDTA was acquired from

Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Eribulin mesylate (1 mg/vial) was generously

provided by Eisai Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and cisplatin was

obtained from JW Pharmaceutical (Seoul, Korea). The half-maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) of eribulin in

MDA-MB-231 cells was determined via CCK-8 assay after 72 h of

treatment and found to be 40.12 µM. Based on this, a concentration

of 60 µM-approximately 1.5 times the IC50- was selected

for subsequent combination experiments. This supra-physiological

dosing strategy aligns with previous mechanistic synergy studies,

such as Ko et al (17) in

TNBC cells combining eribulin and cisplatin and Swami et al

(19) demonstrating similar effects

in SK-BR-3 cells, as well as the in vitro/in vivo work by

Terashima et al (20) on

EMT/MET modulation in TNBC treated with eribulin plus S-1.

PD98059 (a MAPK inhibitor) and crystal violet dye

were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Primary antibodies against LC3-I/II (cat. no. 4108), phospho-ERK1/2

(Thr202/Tyr204; cat. no. 9101), and β-actin (cat. no. 4967) were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Additional antibodies

against ERK (SC-94) and p62 (sc-48389) were acquired from Santa

Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Secondary antibodies

conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (anti-mouse: cat. no. 7076;

anti-rabbit: cat. no. 7074) were also from Cell Signaling

Technology. Chemiluminescence reagents (Super Signal®

West Pico) and DAPI stain were provided by Thermo Fisher. CCK-8

kits were sourced from Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Japan), and

autophagy assays (ab139484) were performed using kits from Abcam

(Cambridge, MA, USA). Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kits were

obtained from Koma Biotech (Seoul, Korea).

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231, a human breast cancer cell line, was

obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank. Cells were grown in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100

µg/ml streptomycin), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), sodium bicarbonate

(1.5 g/l), and glucose (4.5 g/l). Cultures were maintained in a

humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Cell viability assay

To evaluate cytotoxicity, cells were plated at 5,000

cells per well in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight.

Treatments with test compounds were applied for 72 h. After

incubation, CCK-8 reagent (100 µl) was added, and absorbance at 450

nm was measured after a 2-h incubation using a microplate

reader.

Colony formation assay

Colony formation assays were conducted to evaluate

long-term proliferative capacity. MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at

low density in 6-well plates and treated with eribulin, cisplatin,

or their combination for 14 days. Colonies were fixed with methanol

and stained with 0.5% crystal violet.

Colonies were defined as discrete clusters

containing ≥50 cells. Due to the dispersed and small-sized colonies

formed by MDA-MB-231 cells even after 14 days, manual

quantification under a microscope was technically unfeasible. Thus,

colony numbers and areas were quantified using ImageJ software

(NIH, USA) following standard image analysis steps: conversion to

8-bit grayscale, threshold adjustment, watershed segmentation, and

automated particle counting via the ‘Analyze Particles’

function.

Western blot analysis

Cells at approximately 80% confluency were treated

and harvested. Cell lysis was performed using buffer containing

Tris, NaCl, EDTA, Triton X-100, NP-40, PI, DTT, and PMSF. Lysates

were centrifuged, and protein concentrations were measured using a

BCA protein assay kit. Protein (20 µg/lane) was resolved by

SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Blots were blocked

with 5% milk in PBST and incubated with primary antibodies

overnight. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied, and

bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence. Band

intensities were quantified and normalized to the respective

loading controls.

Annexin V/propidium iodide

staining

Apoptosis was quantified using an Annexin V-FITC/PI

kit as per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells treated for 72 h

were collected, stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI, and analyzed

via flow cytometry. Histogram analysis was done using Kaluza

software.

Autophagy detection assay

Autophagy flux was examined using Abcam's

fluorescent dye-based assay (ab139484), which selectively labels

autophagic compartments. Cells were cultured in 8-well chamber

slides and treated with the indicated compounds (100 µM) for the

specified time, fixed with paraformaldehyde, and stained with

autophagy-specific dyes according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Fluorescent signals were observed using a confocal

microscope and quantified with ImageJ.

Combination index

To assess drug synergy, the CI was computed using

the Chou-Talalay method with CompuSyn software (version 1.0,

Combosyn Inc., Paramus, NJ, USA). CI values were interpreted as

follows: CI <1 (synergy), CI=1 (additivity), and CI >1

(antagonism).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently repeated at least

three times. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 29.0 for Windows (IBM Corp.). One-way ANOVA was used with

Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference post hoc analysis. Data are

shown as the mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of eribulin and cisplatin on

cell viability and clonogenic growth

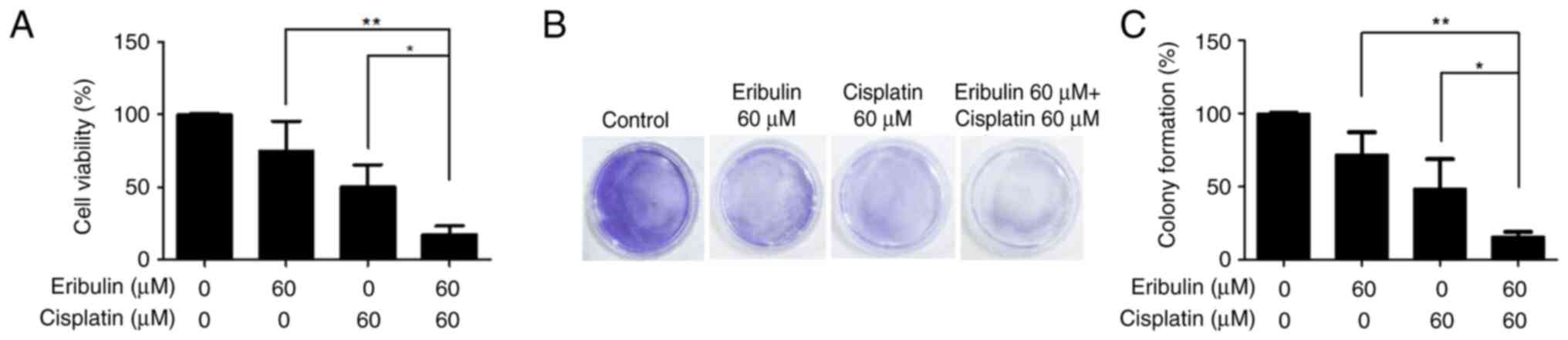

Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay

(Fig. 1A), and the synergistic

efficacy of the drug combination was further confirmed by colony

formation assays (Fig. 1B and C).

Table I summarizes the CI values

derived for the two drugs in this cell model. Single treatment with

eribulin mesylate (60 µM) decreased cell viability to 75.11±0.41%

after 72 h of exposure. Cisplatin (60 µM) single treatment showed a

reduction of 50.57±0.20%. The combination of these drugs

significantly inhibited cell viability to 17.15±0.10% (Fig. 1A). Colony-forming assays were

performed to test the ability of single cells to grow into

colonies. This drug combination synergistically inhibited colony

formation by MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1B

and C).

| Table I.CI value for the combination of

cisplatin and eribulin in MDA-MB-231 cells. |

Table I.

CI value for the combination of

cisplatin and eribulin in MDA-MB-231 cells.

| Cisplatin, µM | Eribulin, µM | CI | DRI

(cisplatin) | DRI (eribulin) |

|---|

| 20 | 10 | 2.35 | 0.74 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 20 | 3.37 | 0.39 | 1.14 |

| 60 | 60 | 0.71 | 1.39 | 3.62 |

| 140 | 140 | 0.59 | 1.68 | 2.62 |

Synergistic activation of ERK1/2 by

drug combination

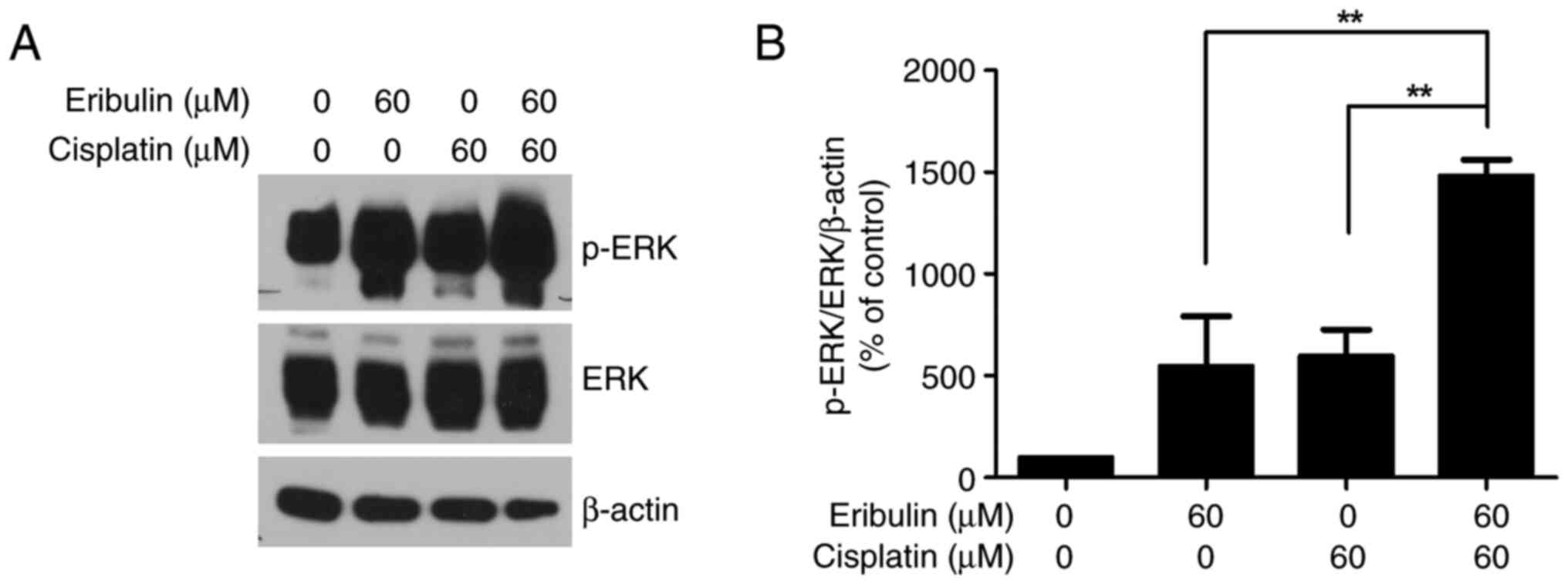

We observed that the ERK phosphorylation level

increased more than 5.5-fold in the experimental cells compared to

that in the control cells after the administration of 60 µM

eribulin for 72 h (Fig. 2A and B).

Moreover, 60 µM cisplatin increased ERK phosphorylation 6.0-fold

(Fig. 2A and B). In addition, when

cisplatin was added to eribulin, ERK activation increased by 14.8

times. When cisplatin was added to eribulin, ERK activation was

elevated 14.8-fold compared to the control, reflecting a 2.7- and

2.5-fold increase relative to eribulin and cisplatin treatment

alone, respectively. These findings confirmed that ERK1/2

activation increased synergistically with eribulin-cisplatin

combination.

Induction of autophagy by eribulin and

cisplatin

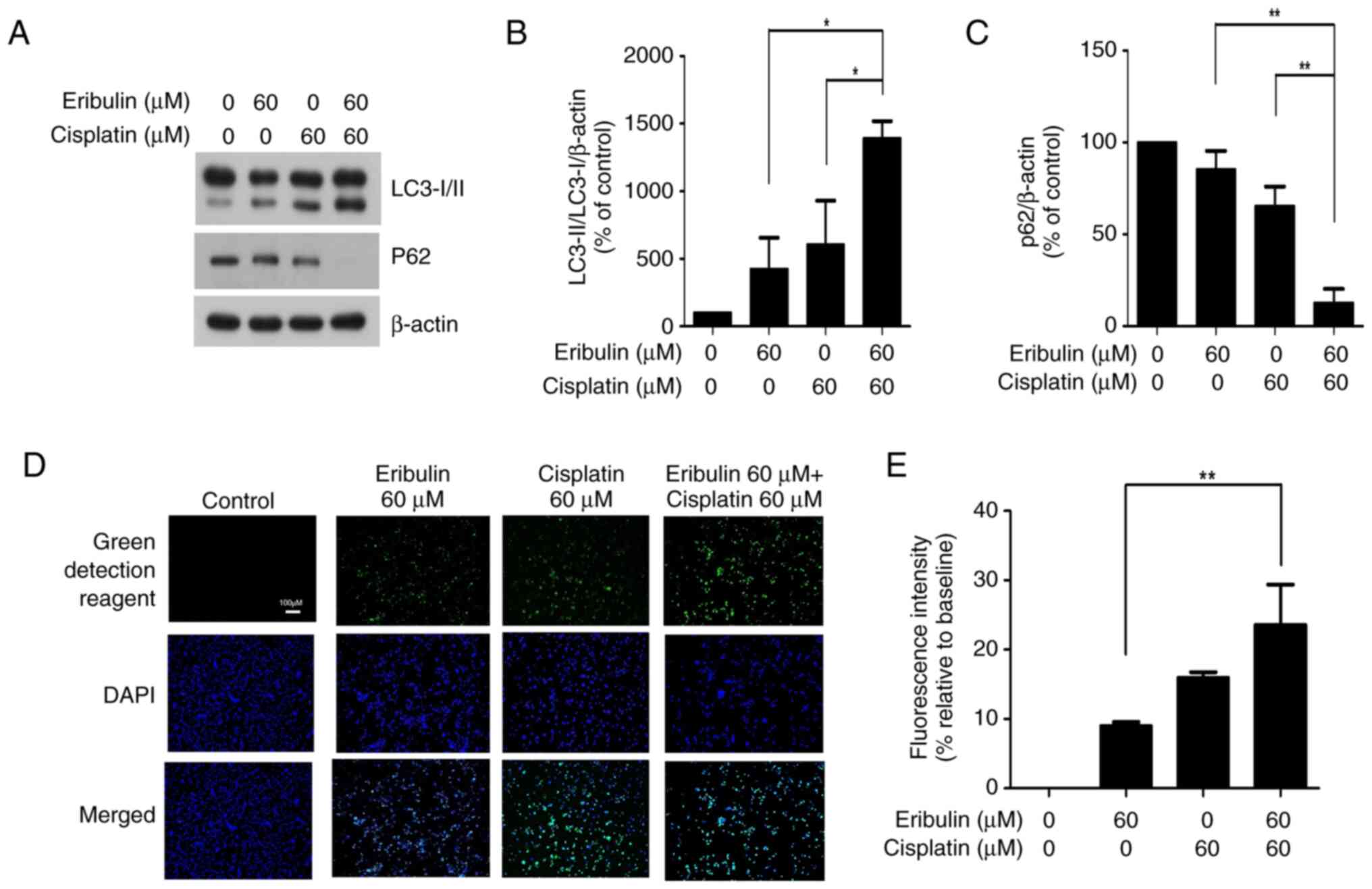

To evaluate autophagy induction, the LC3-I/II ratio

and p62 expression were measured. As autophagy markers, the

microtubule-associated protein LC3-I/II ratio and p62 expression

were determined using western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). The LC3-I/II level increased

4.3-fold in the eribulin group compared to that in the control

group. Cisplatin alone increased the expression of these parameters

by 6.1-fold; the corresponding value for eribulin-cisplatin

combination treatment was 13.9-fold, indicating a synergistic

effect (Fig. 3B). A significant

downregulation of p62 was observed following co-treatment with

eribulin and cisplatin, suggesting promoted autophagic degradation

(Fig. 3C). The corresponding values

for eribulin alone and eribulin-cisplatin combination were 9.0 and

23.6%, respectively, indicating a significant increase in

autophagic activity in the combination group compared with the

eribulin-only group (Fig. 3D and

E). Autophagic vacuole staining showed a slight increase in

autophagic activity with either eribulin or cisplatin alone,

whereas their combination resulted in a marked enhancement,

indicating cumulative autophagic activation.

Apoptosis induced by drug combination

and its dependence on autophagy

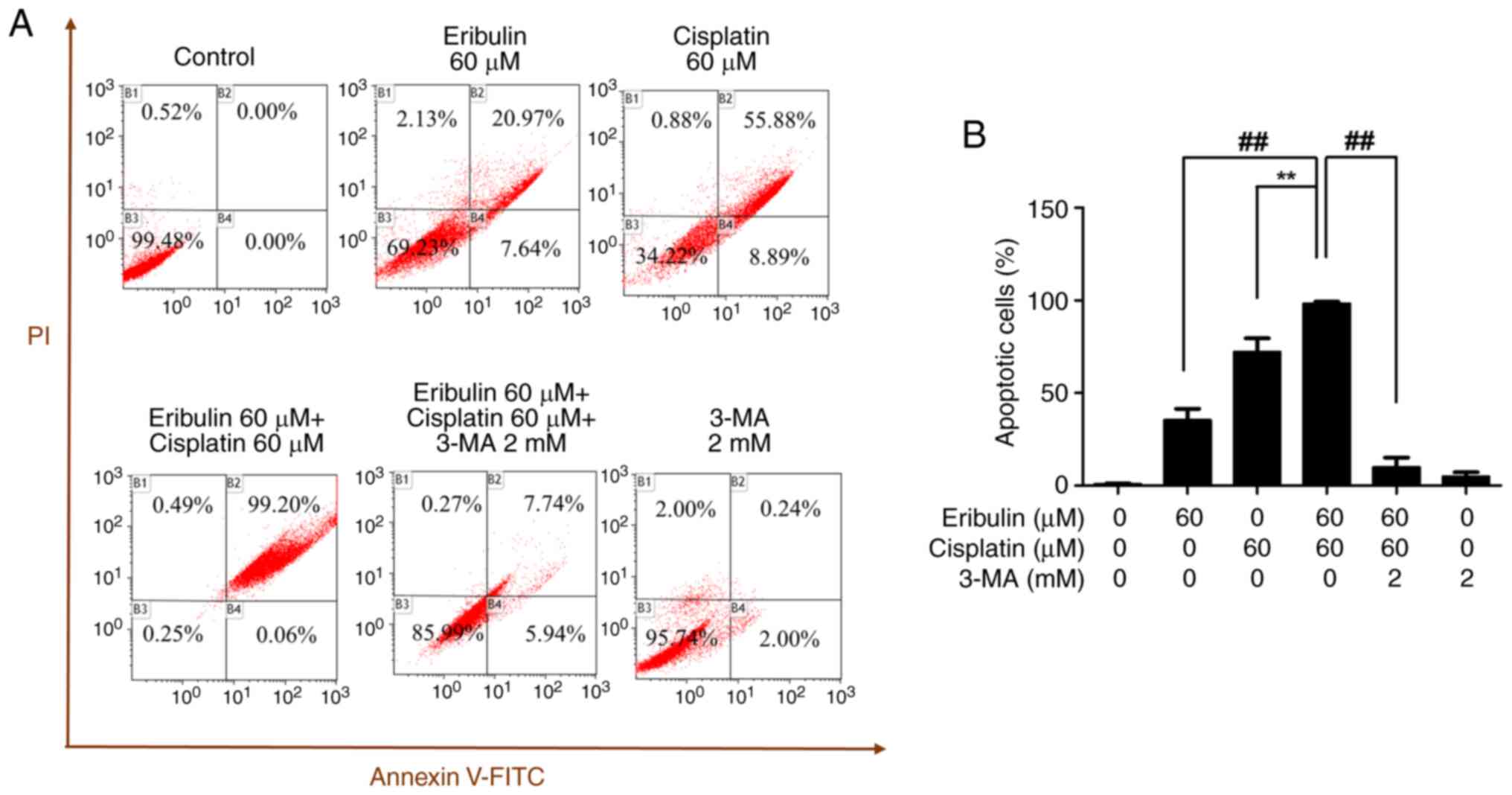

The apoptotic activity of the combination of

eribulin and cisplatin was analyzed by flow cytometry after double

staining with annexin V and propidium iodide (Fig. 4A). The apoptotic activity levels

were 28.61, 64.77, and 99.26% when the cells were treated with

eribulin alone, cisplatin alone, or a combination thereof,

respectively. Upon co-treatment with 3-methyladenine, a known

autophagy inhibitor, the apoptotic rate induced by the

eribulin-cisplatin combination significantly decreased, suggesting

that the observed cytotoxicity is dependent on autophagic

mechanisms. When 3-methyladenine samples were treated with a

combination of eribulin and cisplatin, the apoptotic cell volume

was reduced to 13.68% compared with 99.26% in the

eribulin-cisplatin combination group (Fig. 4A and B).

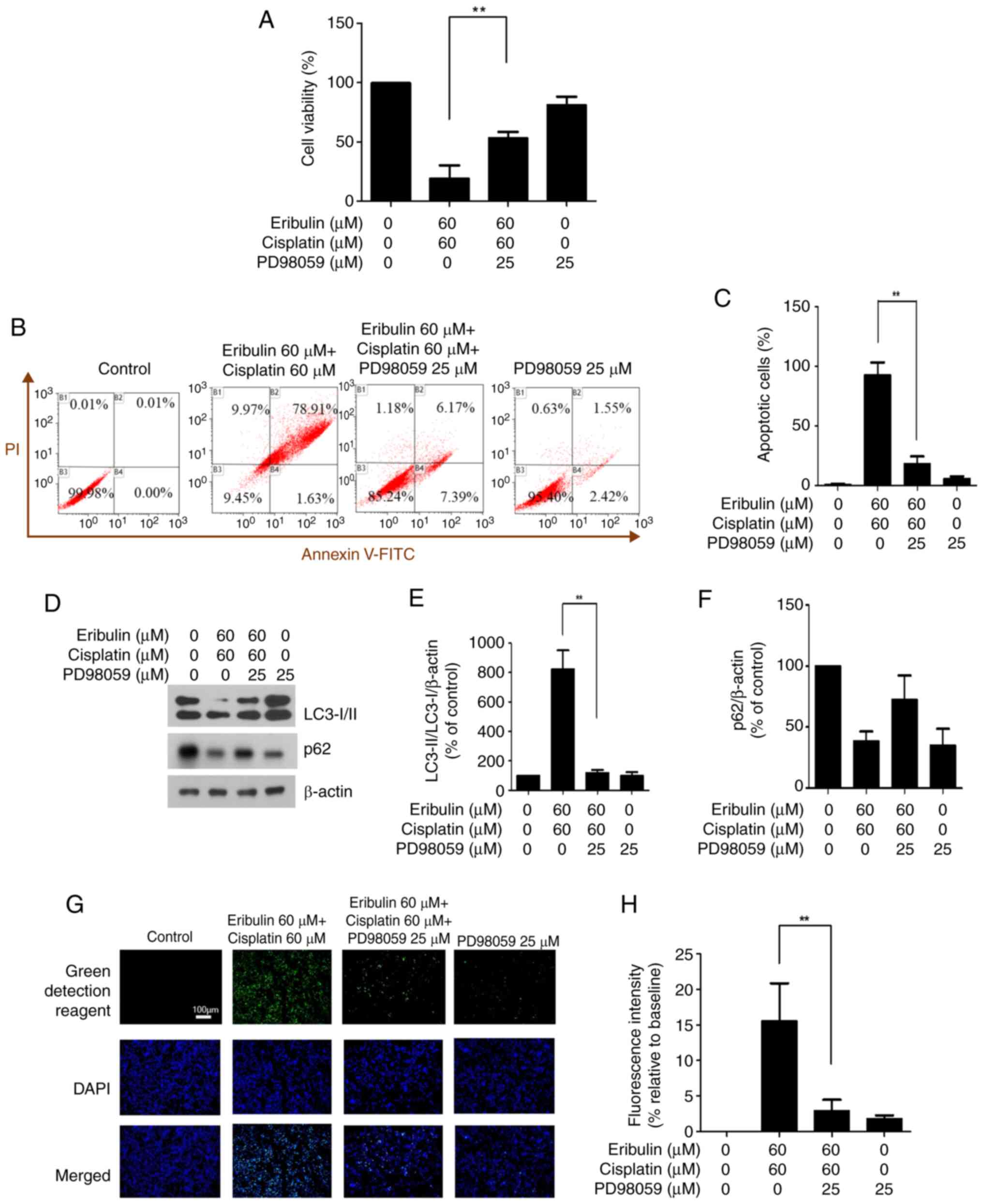

Impact of ERK inhibition on viability,

apoptosis, and autophagy

To assess the impact of ERK inhibition, cells were

pretreated with PD98059 prior to exposure to eribulin and

cisplatin, followed by a viability assessment using the CCK-8

assay. When PD98059 was combined with the two-drug combination, the

cell viability increased significantly from 33.63 to 53.37%

(Fig. 5A). Flow cytometry was used

to quantify apoptotic cells following dual labeling with Annexin V

and propidium iodide (Fig. 5B).

Compared with the eribulin and cisplatin combination group, the

apoptosis rate decreased from 92.72 to 18.01% when PD98059 was used

(Fig. 5C).

Using the control value as the reference (100%),

LC3-I/II expression was markedly increased in the eribulin plus

cisplatin group (824.99%) but was reduced to 119.30% when PD98059

was additionally administered, whereas p62 expression increased

from 38.70 to 72.59% with PD98059 treatment (Fig. 5D-F). Thus, ERK inhibition affected

the expression of autophagy-related proteins.

An autophagy assay (ab139484, Abcam) confirmed that

the levels of autophagosomes decreased when PD98059 was used in

combination with eribulin and cisplatin (Fig. 5G). Quantitative analysis of

fluorescence intensity showed consistent results, decreasing from

15.59 to 2.92% (P<0.05; Fig.

5H).

Discussion

In this study, MDA-MB-231 cells were used to

investigate the cytotoxic effect of a combination of eribulin and

cisplatin, both widely utilized in TNBC treatment. After 72 h of

treatment, significant cancer cell death was observed, mediated by

autophagy-dependent mechanisms involving ERK pathway activation.

These findings reveal a novel therapeutic vulnerability in

TNBC.

Eribulin, a microtubule-targeting agent derived from

the marine sponge Halichondria okadai, has demonstrated

clinical efficacy in breast cancer, particularly in taxane- and

anthracycline-resistant cases (21,22).

The EMBRACE trial notably supported its use in metastatic breast

cancer, with further analyses confirming its benefit in TNBC

(11). Previous studies have shown

that eribulin can synergize with various agents, including HDAC

inhibitors and RAF/MEK inhibitors, primarily through ERK pathway

inactivation (23,24). However, our study uniquely reveals

that eribulin induces cell death via ERK pathway activation,

representing, to our knowledge, the first report of this mechanism

in TNBC.

Cisplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapeutic, also

activates ERK and induces apoptosis across multiple carcinoma types

including cervical cancer (25),

hepatocellular carcinoma (26),

human glioma (27), and mouse

proximal tubule cancer (28).

Consistent with prior reports, our study confirms that ERK

activation persists in MDA-MB-231 cells following cisplatin

treatment, contributing to cell death. Remarkably, the combination

of eribulin and cisplatin further amplified this ERK-driven

autophagic response, leading to significantly enhanced cytotoxic

effects against TNBC cells.

TNBC is molecularly defined by the absence of

estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2

overexpression, rendering it unresponsive to endocrine or

HER2-targeted therapies. This receptor-negative profile contributes

to poor prognosis and compels TNBC cells to rely on alternative

survival pathways such as the MAPK/ERK axis (29,30).

Our finding that ERK activation mediates autophagy-dependent cell

death in response to the combination therapy suggests that this

pathway-typically associated with cellular adaptation and drug

resistance-may instead represent a vulnerability in TNBC (31). Furthermore, high basal autophagic

activity, often driven by MAPK/ERK signaling, has been implicated

in TNBC progression and response to therapy, indicating that

modulation of this pathway could sensitize cells to cytotoxic

agents (32,33).

Autophagy, which often intersects with apoptotic

mechanisms, is increasingly recognized as a modulator of cancer

therapy response (34,35). Our data indicate that ERK activation

is not merely associated with autophagic flux but is a functional

mediator of combination-induced cell death. This positions

ERK-mediated autophagy as a viable target for combination therapy

in TNBC, particularly in the context of eribulin and cisplatin

co-treatment (36,37).

Importantly, the clinical relevance of this

dual-agent strategy extends beyond mechanistic insights. Although

targeted therapies have revolutionized TNBC management in

high-income countries, their high cost continues to restrict access

in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (38). Given that both eribulin and

cisplatin are already approved and relatively affordable, their

combination may offer a scalable and cost-effective solution to

mitigate global disparities in breast cancer treatment (11,17,18).

This approach is consistent with current global oncology efforts

aimed at expanding access to effective therapies in

resource-limited settings.

In LMICs, financial barriers significantly limit

access to novel targeted therapies (39). The monthly cost of immune checkpoint

inhibitors or PARP inhibitors can exceed $5,000 USD, making them

unattainable for most patients (40). In contrast, cisplatin and

eribulin-being off-patent or comparatively affordable-are

frequently listed in public health formularies. For instance, in

South Korea, the cost of eribulin treatment under the national

insurance system is approximately $1,500-$2,000 USD per cycle,

substantially lower than newer biologics [HIRA (Health Insurance

Review and Assessment Service, Korea's national health technology

assessment body)]. These economic factors reinforce the feasibility

of the eribulin-cisplatin combination, especially in regions

striving to deliver cost-effective cancer care (17,18).

In summary, this is the first report demonstrating

that eribulin alone can activate the ERK pathway to induce

autophagy-mediated cytotoxicity in TNBC. These findings highlight

ERK-mediated autophagy as a promising therapeutic target and

underscore the clinical feasibility of the eribulin-cisplatin

combination in both advanced and resource-limited settings.

Nevertheless, this study has limitations. As an

in vitro investigation, it cannot fully recapitulate the

complex tumor microenvironment. In vivo validation using

xenograft models will be necessary to confirm the translational

potential of the eribulin-cisplatin combination, particularly its

impact on ERK-mediated autophagic cell death. However, the recent

NCCN guidelines supporting platinum-based neoadjuvant regimens in

TNBC provide a clinical rationale for future studies (18).

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that

ERK-driven autophagy mediates the synergistic cytotoxicity of

eribulin and cisplatin in TNBC. This mechanism highlights a

clinically feasible and cost-effective therapeutic strategy,

warranting further in vivo validation and clinical

development.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Chungnam National University.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HK and JL conceived and designed the study. HK, ML,

EC and JL contributed to the design of the methodology and

performed experiments. Data analysis and validation were conducted

by HK and JL. Software tool use and visualization were performed by

HK. The experiments were performed by ML, EC and JL, with resources

provided by ML and EC. Data curation was performed by HK, ML and

EC. HK drafted the original manuscript, and JL performed critical

review and editing. Supervision and project administration were led

by JL. Funding for the project was acquired by JL. HK and JL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

ORCID IDs: HK, 0000-0002-6621-8761; JL,

0000-0002-9345-724X; ML, 0000-0003-1732-3001; EC,

0000-0002-7281-3698.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M,

McShane LM, Allison KH, Allred DC, Bartlett JM, Bilous M,

Fitzgibbons P, et al: Recommendations for human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American society of

clinical oncology/college of American pathologists clinical

practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 31:3997–4013. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Morris GJ, Naidu S, Topham AK, Guiles F,

Xu Y, McCue P, Schwartz GF, Park PK, Rosenberg AL, Brill K and

Mitchell EP: Differences in breast carcinoma characteristics in

newly diagnosed African-American and Caucasian patients: A

single-institution compilation compared with the national cancer

institute's surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database.

Cancer. 110:876–884. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM,

Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P and Narod SA:

Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of

recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 13:4429–4434. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sedighi Pashaki A, Sheida F, Moaddab Shoar

L, Hashem T, Fazilat-Panah D, Nemati Motehaver A, Ghanbari Motlagh

A, Nikzad S, Bakhtiari M, Tapak L, et al: A randomized, controlled,

parallel-group, trial on the long-term effects of melatonin on

fatigue associated with breast cancer and its adjuvant treatments.

Integr Cancer Ther. 22:153473542311686242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Moezian GSA, Javadinia SA, Sales SS,

Fanipakdel A, Elyasi S and Karimi G: Oral silymarin formulation

efficacy in management of AC-T protocol induced hepatotoxicity in

breast cancer patients: A randomized, triple blind,

placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 28:827–835.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Salek R, Dehghani M, Mohajeri SA, Talaei

A, Fanipakdel A and Javadinia SA: Amelioration of anxiety,

depression, and chemotherapy related toxicity after crocin

administration during chemotherapy of breast cancer: A double

blind, randomized clinical trial. Phytother Res. 35:5143–5153.

2021. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fazilat-Panah D, Vakili Ahrari Roudi S,

Keramati A, Fanipakdel A, Sadeghian MH, Homaei Shandiz F,

Shahidsales S and Javadinia SA: Changes in cytokeratin 18 during

neoadjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer: A prospective study.

Iran J Pathol. 15:117–126. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Swami U, Chaudhary I, Ghalib MH and Goel

S: Eribulin-a review of preclinical and clinical studies. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 81:163–184. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mani S and Swami U: Eribulin mesilate, a

halichondrin B analogue, in the treatment of breast cancer. Drugs

Today (Barc). 46:641–653. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, Blum

JL, Vahdat LT, Petrakova K, Chollet P, Manikas A, Diéras V,

Delozier T, et al: Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of

physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer

(EMBRACE): A phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet.

377:914–923. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, Yelle L,

Perez EA, Velikova G, Olivo MS, He Y, Dutcus CE and Cortes J: Phase

III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus

capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast

cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J

Clin Oncol. 33:594–601. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ghosh S: Cisplatin: The first metal based

anticancer drug. Bioorg Chem. 88:1029252019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dasari S and Tchounwou PB: Cisplatin in

cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol.

740:364–378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang C, Xu C, Gao X and Yao Q:

Platinum-based drugs for cancer therapy and anti-tumor strategies.

Theranostics. 12:2115–2132. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lin C, Cui J, Peng Z, Qian K, Wu R, Cheng

Y and Yin W: Efficacy of platinum-based and non-platinum-based

drugs on triple-negative breast cancer: meta-analysis. Eur J Med

Res. 27:2012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ko H, Lee M, Cha E, Sul J, Park J and Lee

J: Eribulin mesylate improves cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity of

triple-negative breast cancer by extracellular signal-regulated

kinase 1/2 activation. Medicina (Kaunas). 58:4572022.

|

|

18

|

Obidiro O, Battogtokh G and Akala EO:

Triple Negative breast cancer treatment options and limitations:

Future outlook. Pharmaceutics. 15:17962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Swami U, Shah U and Goel S: Eribulin in

cancer treatment. Mar Drugs. 13:5016–5058. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Terashima M, Sakai K, Togashi Y, Hayashi

H, De Velasco MA, Tsurutani J and Nishio K: Synergistic antitumor

effects of S-1 with eribulin in vitro and in vivo for

triple-negative breast cancer cell lines. Springerplus. 3:4172014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kuznetsov G, Towle MJ, Cheng H, Kawamura

T, TenDyke K, Liu D, Kishi Y, Yu MJ and Littlefield BA: Induction

of morphological and biochemical apoptosis following prolonged

mitotic blockage by halichondrin B macrocyclic ketone analog E7389.

Cancer Res. 64:5760–5766. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Okouneva T, Azarenko O, Wilson L,

Littlefield BA and Jordan MA: Inhibition of centromere dynamics by

eribulin (E7389) during mitotic metaphase. Mol Cancer Ther.

7:2003–2011. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ono H, Sowa Y, Horinaka M, Iizumi Y,

Watanabe M, Morita M, Nishimoto E, Taguchi T and Sakai T: The

histone deacetylase inhibitor OBP-801 and eribulin synergistically

inhibit the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells with the

suppression of survivin, Bcl-xL, and the MAPK pathway. Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 171:43–52. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ono H, Horinaka M, Sukeno M, Morita M,

Yasuda S, Nishimoto E, Konishi E and Sakai T: Novel RAF/MEK

inhibitor CH5126766/VS-6766 has efficacy in combination with

eribulin for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer

Sci. 112:4166–4175. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang X, Martindale JL and Holbrook NJ:

Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J

Biol Chem. 275:39435–39443. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guégan JP, Ezan F, Théret N, Langouët S

and Baffet G: MAPK signaling in cisplatin-induced death:

Predominant role of ERK1 over ERK2 in human hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 34:38–47. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Choi BK, Choi CH, Oh HL and Kim YK: Role

of ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis in A172 human

glioma cells. Neurotoxicology. 25:915–924. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Arany I, Megyesi JK, Kaneto H, Price PM

and Safirstein RL: Cisplatin-induced cell death is EGFR/src/ERK

signaling dependent in mouse proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol

Renal Physiol. 287:F543–F549. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders

ME and Gianni L: Triple-negative breast cancer: Challenges and

opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

13:674–690. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Giltnane JM and Balko JM: Rationale for

targeting the Ras/MAPK pathway in triple-negative breast cancer.

Discov Med. 17:275–283. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sivaprasad U and Basu A: Inhibition of ERK

attenuates autophagy and potentiates tumour necrosis

factor-alpha-induced cell death in MCF-7 cells. J Cell Mol Med.

12:1265–1271. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yu S, Cao Z, Cai F, Yao Y, Chang X, Wang

X, Zhuang H and Hua ZC: ADT-OH exhibits anti-metastatic activity on

triple-negative breast cancer by combinatorial targeting of

autophagy and mitochondrial fission. Cell Death Dis. 15:4632024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Han Y, Fan S, Qin T, Yang J, Sun Y, Lu Y,

Mao J and Li L: Role of autophagy in breast cancer and breast

cancer stem cells (review). Int J Oncol. 52:1057–1070.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Eisenberg-Lerner A, Bialik S, Simon HU and

Kimchi A: Life and death partners: Apoptosis, autophagy and the

cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ. 16:966–975. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rosenfeldt MT and Ryan KM: The multiple

roles of autophagy in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 32:955–963. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gewirtz DA: The four faces of autophagy:

Implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 74:647–651. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

World Health Organization, . Global breast

cancer initiative implementation framework: Assessing,

strengthening and scaling up of services for the early detection

and management of breast cancer: Executive summary. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2023

|

|

39

|

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A,

Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Gralow JR, Cardoso F, Siesling S

and Soerjomataram I: Current and future burden of breast cancer:

Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 66:15–23. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Goldstein DA, Chen Q, Ayer T, Howard DH,

Lipscomb J, El-Rayes BF and Flowers CR: First- and second-line

bevacizumab in addition to chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal

cancer: A United States-based cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin

Oncol. 33:1112–1118. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|