Introduction

Globally, the burden of cancer incidence and death

is increasing rapidly (1). Cancer

is a complex disease and there is no single treatment that is

effective for all types (2,3). With an estimated 1,414,259 new cases

worldwide each year, prostate cancer (PC) is the second most

frequent malignancy and the top cause of death for men worldwide

(4). The average age at diagnosis

is 66 years old, and PC incidence and mortality rise with age

globally (3). There are 158.3 new

cases diagnosed per 100,000 males, with 293,818 additional cases

projected by 2040 (5). Moreover,

African-American men have been reported to experience higher

incidence rates and roughly double the mortality rate from PC than

Caucasian men. This discrepancy has been explained by social,

environmental and genetic variations (2).

PC that is detected early may not show any symptoms,

often advances slowly and may be treated with little-to-no

intervention. The most frequent symptoms, however, are nocturia,

increased frequency of urine and difficulty urinating, which are

indicative of prostatic enlargement. In more advanced stages of the

disease, patients may experience back discomfort and urine

retention due to metastasis to the axis skeleton, the most common

site of bone metastatic disease (6).

The risk of PC is notably influenced by diet and

exercise. For example, dietary factors are associated with the

observed variations in PC incidence rates between countries and

ethnic groups (7,8). However, the majority of studies

concentrate on the genes implicated in the inherited form of PC as

well as the mutations that take place in the acquired form

(6,7). Therefore, a thorough analysis of PC

epidemiology and risk factors may aid in understanding the

relationship between genetic abnormalities and the function of the

environment in causing these alterations and/or encouraging tumor

progression. These differences in PC incidence imply that the

etiology of PC is markedly influenced by environmental variables.

However, underdiagnosis, disparities in screening techniques and

access to healthcare may also contribute to variations in incidence

(6).

Due to several biological and tumor

microenvironmental factors, PC presents substantial treatment

challenges. For example, prostate tumors often have a low tumor

mutational burden, meaning that the immune system targets fewer

neoantigens (9). Furthermore,

immunosuppressive cells, such regulatory T cells, tumor-associated

macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, are present in

the PC immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. The normal immune

response against cancer cells is hampered by these cells, which

produce a ‘cold’ tumor environment with limited immune cell

penetration (10). Furthermore,

although androgen deprivation therapy is initially successful,

certain patients experience resistance to the treatment, which can

result in metastatic castration-resistant PC. Changes in the tumor

microenvironment and immune evasion strategies are associated with

this development (11).

Using immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines,

chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatment and combination

medicines, immunotherapy offers potential treatments by using the

immune system to target and kill cancer cells. By reducing

antitumor immune responses or modifying tumor immunogenicity,

several immune system components cooperate to either protect the

host against necessary tumor progression, enhance tumor escape, or

both (12). This process is known

as cancer immuno-altering (12,13).

Immune spots, which are resistant cell surface receptors that

regulate the suppression or activation of immune reactions, serve

an important role in different phases of the immune responses. For

example, both PD-1 (Programmed Death-1) and cytotoxic

T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 CTLA4, prevent overactivation of

the immune system once binding to their ligands (14). The optimum outcome for controlling

tumors is immune system activation (13). In addition to surgery, chemotherapy,

radiation and targeted medicines, cancer immunotherapy has become a

crucial therapeutic approach. Furthermore, cancer immunotherapy has

demonstrated encouraging outcomes with several cancer types and can

be used in conjunction with other treatments. Consequently,

immunotherapy has been reported to have notable benefits: In one

study (15) immunotherapy improved

lung cancer treatment PD-1 inhibitor to standard chemotherapy,

increased objective response rate and progression free survival. In

addition, another study showed that combining immunotherapy with

radiation enhance anti-tumor immune response through increasing the

release of tumor antigen following radiation (16).

A subset of lymphocytes, known as natural killer

(NK) cells, is essential to the innate immune response against

malignancies and infections (17,18).

NK cells are able to recognize and target cancerous and

contaminated cells (19,20), and ~90% of the circulating NK cell

population is made up of CD56 and CD16 cells, which cause cell

lysis by releasing cytolytic granules that include granzyme and

perforin. Together, NK cells and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) cause target

cells to undergo apoptosis (21,22).

For aberrant cells, NK cells increase antibody-mediated

cytotoxicity and cytotoxic T lymphocytes act in a similar manner

(23).

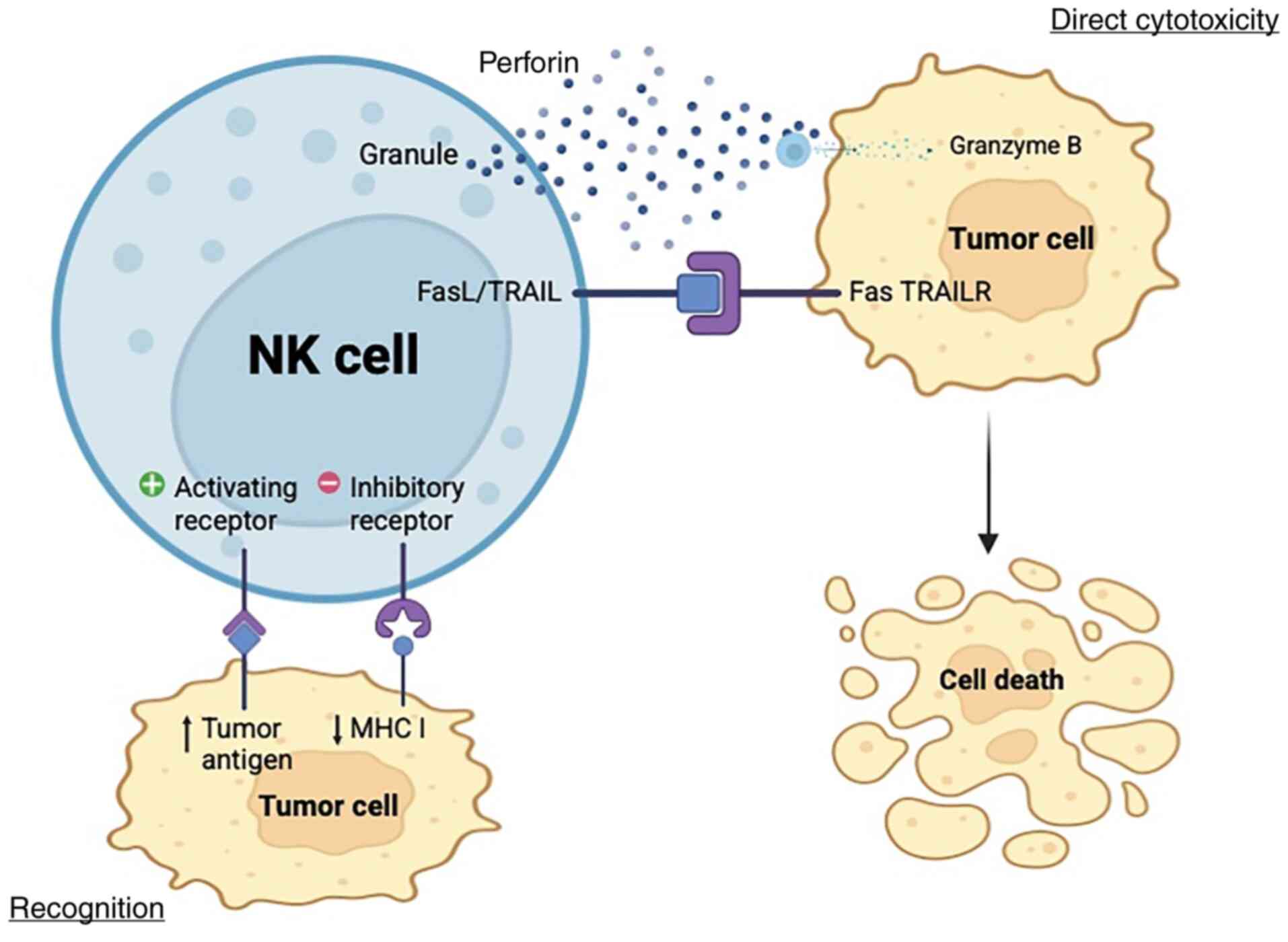

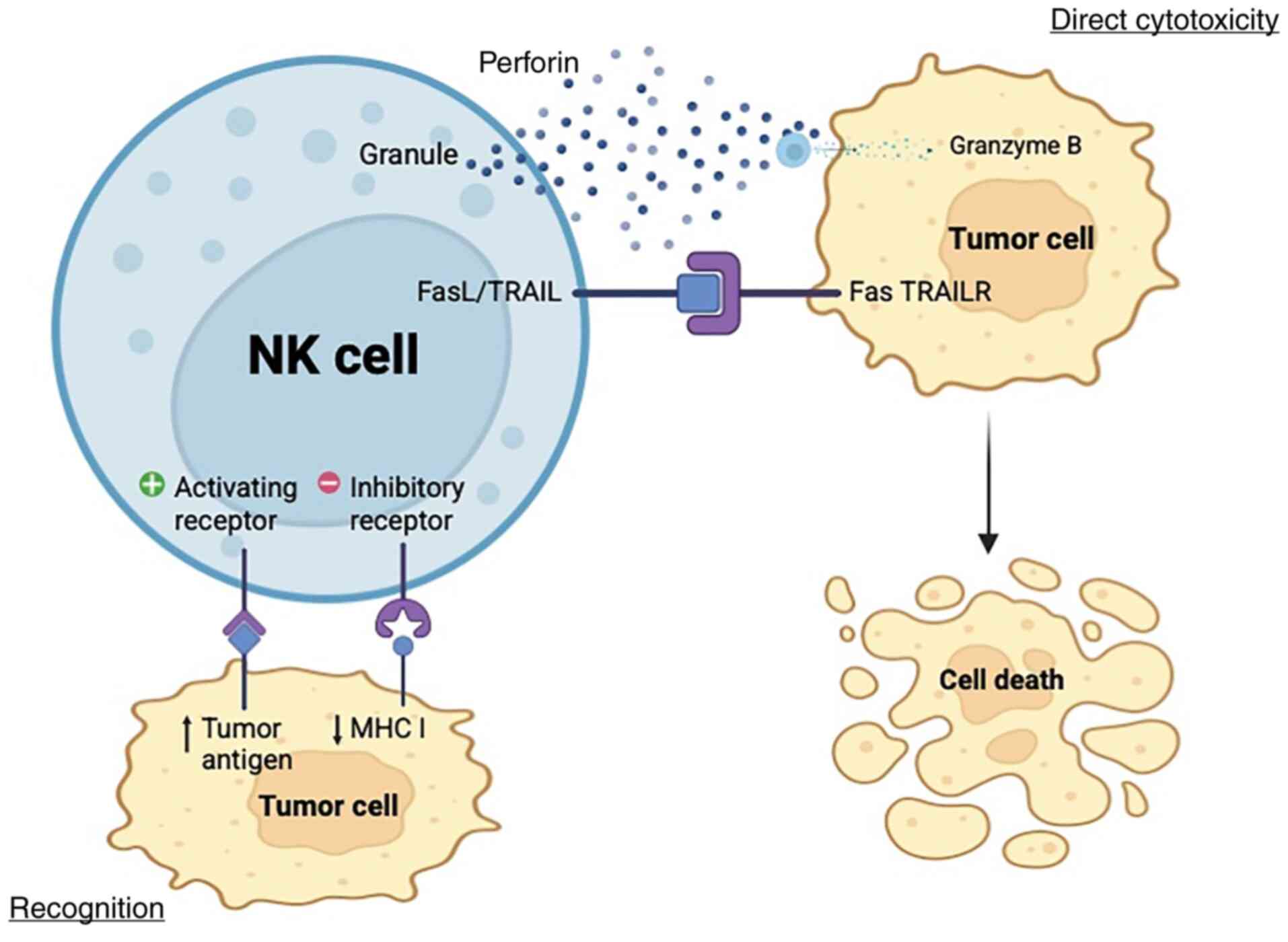

NK cells help to defend the body against foreign

(pathogens) and endogenous (cancer) threats. Extensive research has

been performed with the goal of identifying an efficient method for

targeting impacted cells by utilizing NK cell pathways (24) (Fig.

1). However, notwithstanding the promising results of this

research, tumor cells develop a defense mechanism that thwarts the

cytotoxicity caused by NK cells (25,26).

| Figure 1.Cytotoxicity mechanism of NK cells.

By evaluating the net input of activating and inhibitory signals

from target cells through NK cell surface receptors, NK cells

discriminate healthy cells from target cells. However, several

tumors develop mechanisms to escape NK cell immune responses by

modifying their cell surface molecules, such as low immunogenicity.

Following the identification of the target cell by NK cells, the

stimulation domain is activated. This is initiated by the secretion

of a cytolytic enzyme, known as perforin, stored in NK cell

vesicles. Perforin creates pores in the cell membrane of the target

cell, allowing the passage of granzymes into the target cell and

starting protein digestion (cytolysis). NK cells express TRAIL and

FasL, which interact with TRAIL receptors and FAS ligands in cancer

cells, respectively. This interaction results in cell death,

signaling complex stimulating apoptosis. NK, natural killer; TRAIL,

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand; TRAILR, TRAIL receptor; MHC,

major histocompatibility complex; FasL, FAS ligand. Created in

BioRender.com. |

Research is investigating the use of NK cells to

treat (27–29) PC. NK cells can directly target and

eliminate PC cells, resulting in direct tumor cytotoxicity.

Moreover, research has reported that, both in vitro and

in vivo, genetically modified NK cells, such as

prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted chimeric antigen

receptor-NK cells, have strong cytotoxic effects on PC cells. They

can specifically identify and eliminate PSMA-expressing PC cells,

providing a targeted therapy strategy. Therefore, these altered NK

cells may be employed as an ‘off-the-shelf’ therapeutic option,

enabling a sustainable and economical treatment technique (27).

Additionally, PC cells usually develop defenses

against immune detection, such as by producing soluble NK cell

receptor D (NKG2D) ligands to obstruct the recognition of NK cells.

However, NK cells can adapt to these challenges, and strategies are

being developed to make them more effective against these tumor

escape tactics (28). Investigating

NK cell function against PC is challenging as they produce TGF-β,

IL-10 and regulatory T cells, inhibiting NK activation, and have

low infiltration of NK cells making it hard to study their direct

interaction with PC. PC is a useful model for researching NK

cell-mediated therapy, for example due to the immune

microenvironment dynamics, in which PC tumors are distinguished by

a distinct immune milieu that consists of both immuno-suppressive

and immune-activating components (29–32).

As studies have reported that NK cells in patients with PC

frequently have compromised cytotoxic function, this environment

offers a realistic setting for researching how NK cells interact

with tumor cells and the factors determining their efficacy

(29,33). This malfunction provides a clear

target for therapeutic intervention trials targeted at restoring NK

cell activity and is associated with the course of the disease.

Furthermore, research employing preclinical models has reported

that NK cells are capable of efficiently inhibiting the

proliferation of PC cells resistant to castration. These results

highlight how effective NK cell-based treatments can be in treating

advanced PC (30). Nevertheless, PC

uses several strategies to avoid immune monitoring, especially from

NK cells. These tactics include modulating the expression of NK

cell receptors, secreting immunosuppressive substances and changing

the expression of ligands (28). PC

cells can decrease the expression of ligands such NKG2D and DNAX

accessory molecule 1 that are recognized by NK cell receptors.

Moreover, immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGF-β are abundant in

the tumor microenvironment. The release of TGF-β causes the

activating receptors of NK cells, including NK cell P30-related

protein and NKG2D, to be downregulated, which reduces the cytotoxic

effects (31). Furthermore, PC can

cause NK cells to exhibit a fatigued phenotype, which is typified

by decreased activating receptor expression and decreased cytotoxic

activity. This fatigue is associated with NK cells expressing more

inhibitory receptors, such as T cell immunoglobulin mucin 3 and

programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), which results in weakened

antitumor responses (32).

Additionally, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on

cancer cells may be upregulated in PC with hypoxic circumstances.

Immune evasion is facilitated by the inhibition of the cytotoxic

function of NK cells caused by the interaction between PD-L1 and

its receptor PD-1 (34).

Finally, due to their ability to treat numerous

diseases, several plants are regarded as useful therapeutic

instruments in a wide range of medical disorders. Moreover,

different medicinal plants have been used worldwide to alleviate

the symptoms of several illnesses for millennia (35). One well-known example with a wide

range of applications is Nigella sativa, also known as dark

cumin. For two millennia, populations around the world have

utilized this plant, a dicotyledon of the Ranunculaceae

family, as a snack, spice and nutritional supplement (36). Thymoquinone (TQ), the main active

ingredient in the black seeds, has garnered interest in both

traditional medicine and contemporary therapeutic research

(37,38). Therefore, the present study aimed to

assess how TQ, which comprises ~40% of Nigella sativa

(38), affects the cytotoxic

activity of NK cells against the PC3-RFP cell line. The results

could aid in comprehending the potential therapeutic impact of TQ

on NK cells for cell-based immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Blood collection

Blood samples were collected at King Abdulaziz

University Hospital (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) between August and

November 2021 from 10 healthy volunteers six male, four female and

aged 25–45 years in EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer) and used for NK cell

isolation. All experiments were performed at King Faisal Specialist

Hospital and Research Centre (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia). Inclusion

criteria for enrolled participants include general good health with

no chronic diseases, recent infections and immunosuppressive

medication or vaccination. Exclusion criteria were smoking,

pregnancy or breastfeeding, autoimmune disease and malignancy.

MACS positive isolation

NK cells were purified by positive selection of CD56

cells (CD56 MicroBeads, human, 130-050-401, Miltenyi biotec) and

MACS column (130-042-201, Miltenyi biotec, USA) was used according

to the manufacturer's instruction.

Cell lines and culture

Transfected PC3 cells with red fluorescence (PC3-RFP

cells) with the pDSRed-monomer-Hyg-C1 plasmid to produce

hygromycin-resistant cells that express RFP were provided by

AlShaibi et al (39). The

cells were stored at King Fahd Medical Research Center (Jeddah,

Saudi Arabia) and used in the present study.

PC3-RFP cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM

(cat. no. 11965118; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), with sodium

pyruvate L-glutamine and Phenol Red, and supplemented with 10%

penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/ml; cat. no. 15140122; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). NK cells were cultured in NK MACS Medium

(cat. no. 130-092-657; Miltneyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG),

supplemented with 20% FBS (cat. no. 12103C; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA),

IL-2 (human animal-component free, recombinant, expressed in E.

coli, ≥98%; cat. no. SRP3085; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The cells

were routinely maintained in humidified incubator at 37°C and 5%

CO2.

TQ preparation

TQ (cat. no. 274666-1G; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

was prepared by dissolving 4.926 mg TQ crystal in 10 µl anhydrous

dimethyl sulfoxide (≥99.9%; cat. no. 276855; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) and 9,990 µl NK medium to yield a stock solution. The final

DMSO concentration in all TQ working solutions (50 and 25 µM) was

0.1%. Vehicle controls containing 0.1% DMSO in NK medium without TQ

were included in all experiments.

Cell cytotoxicity of TQ on tumor

(PC3-RFP) and NK cells

Cell cytotoxicity was analyzed using the

CytoTox® 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit

(Promega Corporation). Briefly, PC3-RFP was plated at a density of

15×103 cells per well in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and

incubated overnight at room temperature. Subsequently, NK cells

were co-cultured at an effector cell/target cell ratio of 1:2 in

the presence of different concentrations (25 and 50 µM) of TQ for 5

h. CytoTox 96 lysis buffer was added and incubated for 45 min at

room temperature. CytoTox 96 reagent was then added to each well

and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, and then

the stop solution was added. The absorbance was measured at 680 and

490 nm.

Flow cytometry

Following positive selection of NK cells were

stained with CD56-PE (DAKO; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at 25°C for

30 min in the dark. The cells were then analyzed using flow

cytometry (Novocyte Flow Cytometer; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Phycoerythrin (PE) detection channel was the analyte detector,

CD56-PE was the analyte reporter, and NovoExpress software (version

1.6.3; Agilent Technologies, Inc.)used for data acquisition and

analysis.

ELISA

PC-3-RFP and NK cells (1:2; 15–30×103)

were cocultured in the presence of TQ for 5 h at 37°C. Cell-free

supernatants were harvested and ELISA was used for detection of

IFN-α (Human IFN-α ELISA Kit; cat. no. BMS216 Invitrogen™; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), granzyme B [Human granzymes B (Gzms-B)

ELISA kit; cat. no. E0899Hu; Shanghai Korain Biotech Co., Ltd.] and

perforin [Human Perforin/Pore-forming protein (PF/PFP) ELISA Kit;

cat. no. E0070Hu; Shanghai Korain Biotech Co., Ltd.] were used.

Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (IBM

Corp.) and the results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation of three independent experiments. Statistical

significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance and

Tukey's multiple comparison test. Spearman correlation coefficient

was used for correlation tests. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

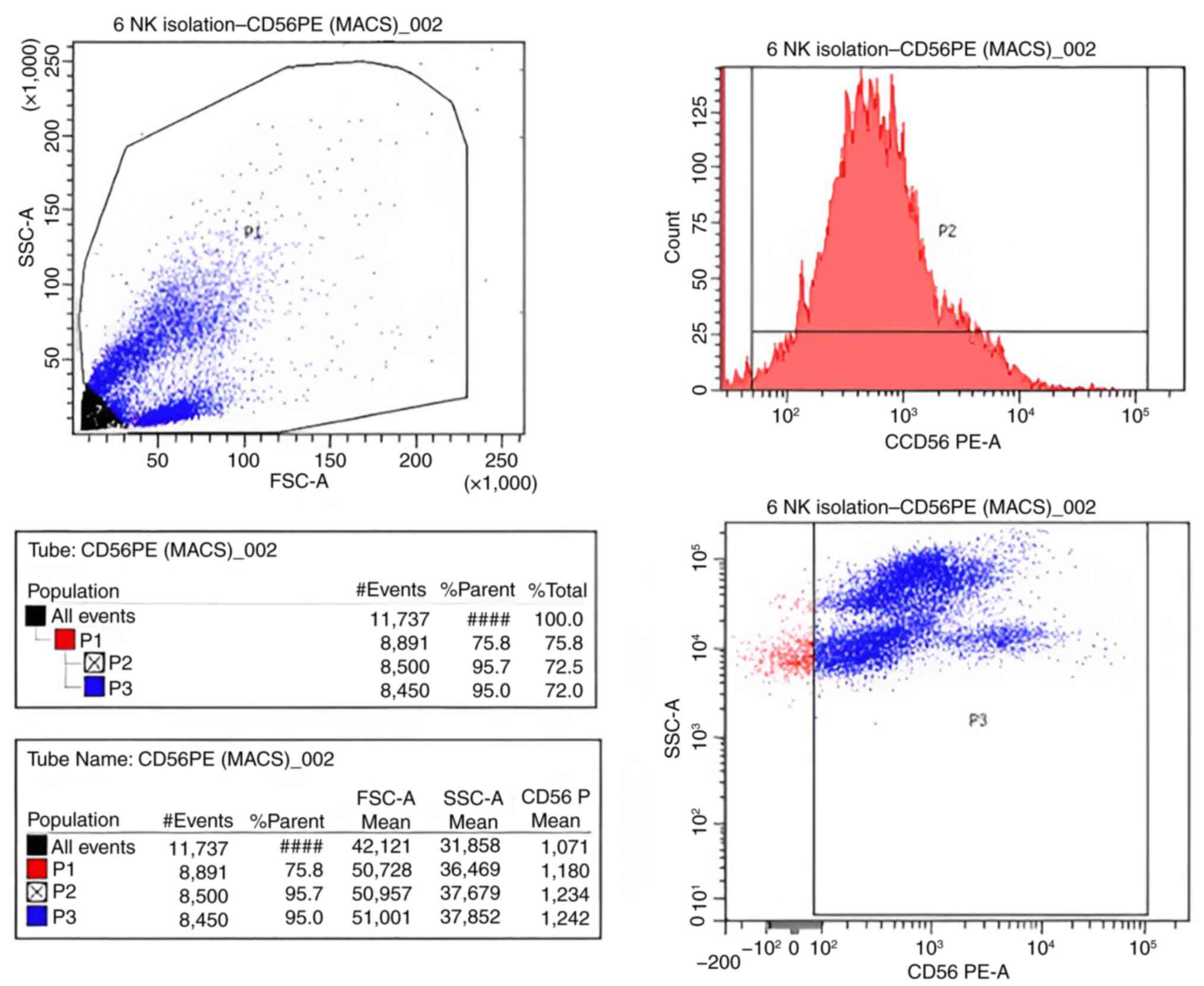

Flow cytometry analysis

Using flow cytometry, the positivity of CD56 was

determined to assess the purity of the isolated NK cells by

comparison with the defined cutoff values obtained with unstained

control cells. The NK cell purity was 95.7% (Fig. 2).

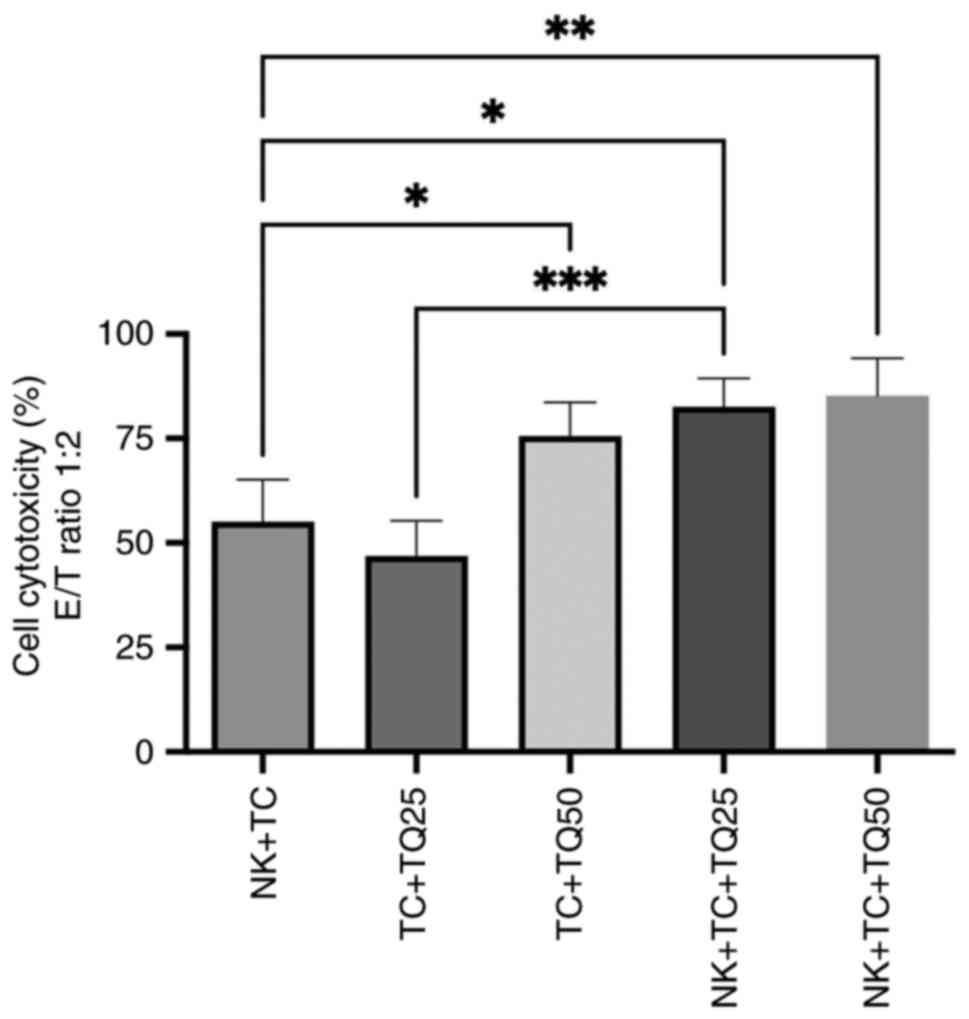

Cytotoxic effect of TQ on NK cells

with PC3-RFP

The cytotoxicity of NK cells was evaluated in

co-culture with PC3-RFP cells. The effector (NK cells) and target

(PC3-RFP) ratio was 1:2 and different concentrations of TQ (25 and

50 µM) were added in the culture. In the presence of TQ, there was

a significant increase in NK cell cytotoxicity: Both concentrations

of TQ (25 and 50 µM) significantly upregulated NK cell cytotoxicity

in PC3-RFP cells, with cytotoxicity at 85.35% compared with 55.1%

in the control group of NK cells co-cultured with tumor cells. Cell

cytotoxicity was also significantly increased in tumor cells

treated with both 25 and 50 µM TQ in the presence of NK cells,

compared with tumor cells treated with the same TQ concentrations

in the absence of NK cells (Fig.

3).

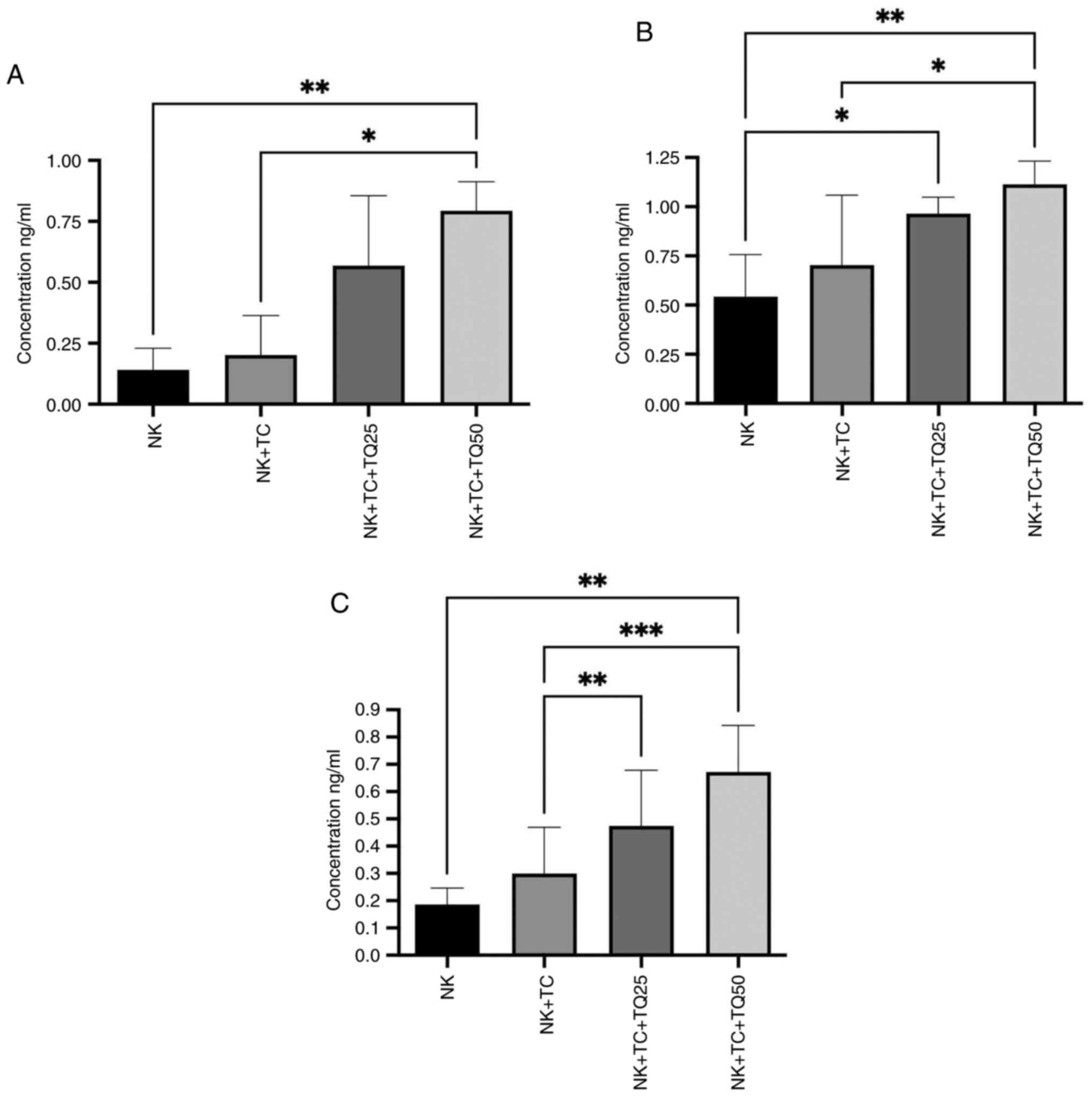

Effect of TQ on the activity of NK

cells

Co-culture of NK cells with PC3-RFP cells

significantly increased the production of perforin, granzyme B and

IFN-α from NK cells compared with NK cells alone using both

concentrations of TQ (25 and 50 µM). NK cells co-cultured with

PC3-RFP cells and treated with 50 µM TQ had significantly increased

production of perforin and granzyme B production compared with the

control NK cells co-cultured with tumor cells. The higher 50 µM TQ

dose increased the production of perforin and granzyme B (0.80 and

1.24 ng/ml, respectively) by the NK cells more than the lower 25 µM

dose (0.50 and 0.76 ng/ml, respectively). Furthermore, IFN-α

production by the NK cells was significantly increased in the

presence of 25 and 50 µM TQ (0.5 and 0.7 ng/ml, respectively)

compared with the control NK cells co-cultured with tumor cells

(0.3 ng/ml), with a greater increase observed in the presence of 50

µM TQ (Fig. 4).

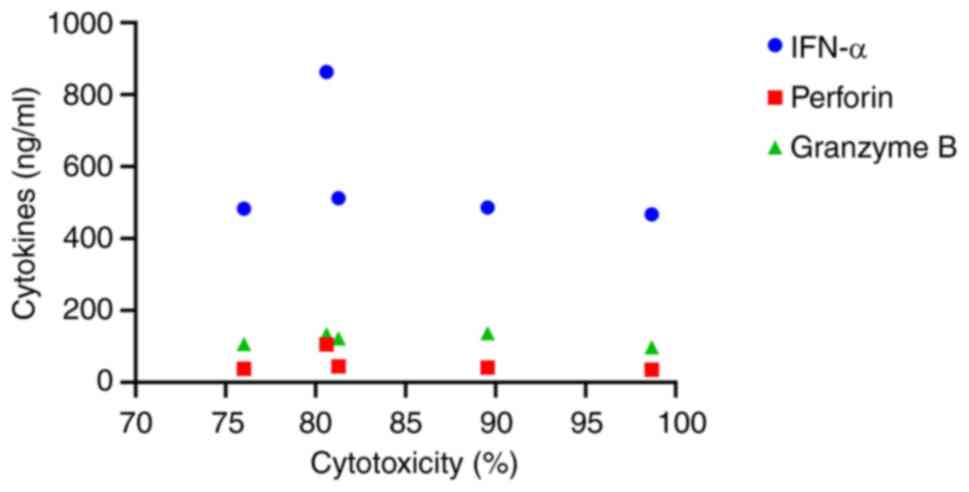

The correlation between individual cytokines and NK

cytotoxicity was analyzed using the Spearman correlation

coefficient. Although there was no significant correlation between

the cytokine concentrations and NK cytotoxicity; NK cells released

higher levels of IFN-α in response to PC3-RFP cells compared to the

other cytokines (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Several studies have reported the immunomodulatory

effect of TQ on immune cells including NK cells (40–43).

The current study focused on investigating the effect of TQ on the

cytotoxicity of NK cells and its anticancer activity against

PC3-RFP cells. The results demonstrated that treating cancer cells

with a high dose of TQ in the presence of NK cells enhanced NK cell

cytotoxicity more than NK cells co-cultured with cancer cells alone

or in cells with a lower dose of TQ Furthermore, NK cells cultured

with cancer cells treated with both TQ concentrations (25 and 50

µM) exhibited considerably increased NK cell cytotoxicity compared

with cancer cells treated with TQ alone. This indicates that the

antitumor effect of TQ is associated with its stimulation of NK

cell function.

Majdalawieh et al (44) assessed how Nigella sativa

extract affected the immune systems of mice and reported that the

extract activated macrophages, increased NK cell antitumor

activity, changed the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance toward a

Th1-dominant response, and markedly increased splenocyte

proliferation. Despite the fact that TQ, a crucial component of

N. sativa, was not isolated, the results indicate that the

extract enhances antitumor immunity by inducing both innate and

adaptive immunological responses, potentially through TQ (44). Furthermore, a study by Sjs et

al (45) produced a

nanomedicine based on TQ and reported that administration of the

nanomedicine to triple negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231

was associated with apoptosis, DNA damage, slowing down of the cell

cycle and prevention of cell division (45). According to these findings, TQ may

be a potential strategy for both preventing and treating cancer

(46,47).

Nigella sativa may affect cancer

pathophysiology via several signaling pathways, such as inducible

nitric oxide synthase, p53, ROS, TNF and caspases. These mechanisms

have been demonstrated by numerous in vitro and in

vivo studies, which suggest that N. sativa concentrates

can be used to treat several malignant tumor types at different

phases of carcinogenesis (40–42).

Additionally, the medicinal plant is well-known for its potent

protective benefits against the development and spread of tumors,

as well as its anti-inflammatory and immune-stimulating properties,

all of which make it a useful supplement to cancer treatment plans.

Its impact on the NK cells may be responsible for these

effects.

It has been reported that TQ combined with ionizing

radiation, such as γ-radiation, has a synergistic lethal effect on

breast cancer cells in vitro (42,43,48–50).

Moreover, according to the present study, TQ administration

directly increased the capacity of NK cells to lyse human PC

(PC3-RFP) cells. TQ functions as an antimetabolic medication and

may inhibit the development of colorectal cancer carcinogenesis by

controlling the glycolytic metabolic pathway and the PI3/AKT axis

(51). Additionally, pretreatment

with TQ-pH-sensitive liposomes (PSL) decreased cancer marker

enzymes, restored the relative weight of the lung and enhanced the

activity of antioxidant enzymes in serum, according to a lung

cancer study that prepared TQ in a particular formula as TQ-PSL to

increase its solubility. Histopathological analysis revealed that

TQ-PSL protected lung tissues by decreasing oxidative stress,

suppressing inflammatory mediators and inducing apoptosis in

pre-cancerous cells (52). TQ

itself may be also useful as a treatment for lung adenocarcinoma as

it has been reported to inhibit tumor cell proliferation, induce

lung cancer cells to undergo apoptosis, markedly reduce TNF and

NF-kB activity, and arrest cells in the S phase of the cell cycle

(53). TQ has also been widely used

in biomaterial treatments (54).

Furthermore, TQ has demonstrated notable anti-hepatocellular

carcinoma potential, modulating the ERK and p38 signaling pathways,

the. Cytotoxic effect of TQ is enhanced by low ERK phosphorylation

or ERK inhibition as elevated p-ERK activity protect hepatocellular

carcinoma from TQ toxic effect (55,56).

TQ and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand may cooperate to

trigger apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by mediating DNA

damage, according to Zhang et al (57) TQ also has an effect on other

cancers. For example, TQ markedly increased the amount of reactive

oxygen species (ROS) produced by human pancreatic cancer cells

whilst simultaneously suppressing the migration and proliferation

of cancer cells. Moreover, natural quinones such as TQ may be

effective antimetastatic treatments for pancreatic cancer based on

these findings (58). As TQ

successfully inhibits the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes,

cancer cells incur apoptosis. Furthermore, TQ causes apoptosis by

increasing ROS levels (59). TQ may

also function as an immunomodulatory drug that boosts anticancer

immune activity, as reported in other in vitro and in

vivo research (48,59). It has been also reported that TQ may

work in conjunction with chemotherapy and radiation to improve

treatment results and reduce treatment side effects (59,60).

Research by Shimasaki et al (61) indicates that NK cells are essential

for the regulation of tumor development and metastasis. NK cells

contribute to the induction of adaptive anticancer T cell and B

cell responses in addition to their function in the early defenses

against infection and cancer (61,62).

Additionally, NK cells can swiftly eliminate nearby cells that have

surface markers associated with neoplastic transformation (53). The direct immune-stimulating impact

of TQ on NK is well supported by the current data. In the present

study, TQ increased the NK cell production of IFN, which is

consistent with other research (4,47)

which have reported that the cytotoxic effect of NK cells on tumor

cells was increased in the presence of TQ, with increased secretion

of perforin, granzyme B, and IFN-α, and that TQ promoted the

cytotoxic activity of NK cells against breast cancer MCF-7 cells

(63). The results of the present

study also supported earlier research by demonstrating the

inhibitory action of TQ on human PC PC3-RFP cells. Notably, TQ

therapy directly increased the capacity of NK cells to kill PC3-RFP

cancer cells. In the NK + TQ + PC3-RFP group in the present study,

IFN activity increased, indicating higher concentration.

Subsequently, the rise in granzyme B was comparable with earlier

research (60,61,64)

which showed granzyme B trigger apoptosis by cleaving (BID) BH3

Interacting-Domain Death Agonist pro apoptotic protein of Bcl2

family, causing mitochondrial distribution and activating caspases.

This process is crucial for NK cells to induce death in cancer

cells (65). Although BID activity

was not measured in the present study, previous studies

demonstrated the importance of mitochondrial disruption by BID to

reach the lethal effect supporting the importance of granzyme B

mediated pathways in NK cells cytotoxicity on caspases and causing

cell death (64,65). Therefore, granzyme activity

measurements are important in studies on NK cytotoxicity.

Furthermore, according to the findings of the

present study, TQ affects NK cells, which then directly stimulates

the immune system. The TQ-induced immunoreactivity of NK cells

against PC3-RFP cells increased when 50 µM TQ was applied, compared

with 25 µM. This indicated that the stimulation of NK cells by TQ

was associated with its cytotoxic effect on PC3-RFP cells. However,

although certain signaling molecules implicated in producing the TQ

immunostimulatory action in NK cells have been identified, the

specific signaling pathways and molecular targets in these cells

are still unknown. It has been suggested that TQ increases NK

cell-mediated cytotoxicity by upregulating pro-apoptotic markers

such as BAX and BID and downregulating anti-apoptotic proteins such

as BCL-2 and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (66). TQ prevents NF-κB, a transcription

factor implicated in inflammatory reactions, from activating. TQ

also improves NK cell function and lowers pro-inflammatory cytokine

expression by inhibiting NF-κB activation, which helps to

strengthen antitumor immunity (67). Moreover, by upregulating PTEN, TQ

disrupts the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and reduces AKT activity.

This downregulation enhances NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity and

promotes apoptosis in cancer cells by reducing cell survival and

proliferation signals. Furthermore, antioxidant enzymes are

upregulated when TQ stimulates the Nrf2 pathway. By shielding NK

cells from oxidative stress, this modulation preserves their

functioning and increases their antitumor activity (68). Therefore, more in vitro and

in vivo studies are required to identify the target

receptors and intracellular and extracellular components that have

unique activities in the signal transduction pathways associated

with TQ changes in NK cells.

Despite, the promising results of the capacity of TQ

to increase NK cell cytotoxicity against PC3-RFP PC cells in

vitro, a number of limitations of the present study should be

noted. The in vitro design of an experiment cannot fully

replicate the intricate interactions in the tumor microenvironment,

including tumor-induced immunosuppression, cytokine gradients and

immune cell trafficking. In addition, the study did not explore the

precise molecular mechanisms behind TQ-induced increased NK cell

activity, necessitating further investigation into signaling

pathways, receptor expression changes and gene regulatory networks.

Moreover, the study used PC3-RFP, a single PC cell line; however,

its potential application to other subtypes or primary tumor cells

is uncertain due to its heterogeneity. Finally, the observed

effects may be influenced by the NK cell source and activation

state, with variability in cytotoxic responses potentially

introduced by incomplete donor characterization, isolation

techniques and baseline NK cell activity. Future therapeutic

development depends on determining the ideal concentration range

that maximizes tumor cell killing without compromising NK cell

viability or function.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

TQ, a bioactive substance obtained from Nigella sativa,

significantly increases the cytotoxic activity of NK cells against

PC3-RFP cells. As a potential supplement to immunotherapeutic

approaches in the treatment of PC, the findings imply that TQ may

enhance the innate immune response, specifically by increasing NK

cell-mediated tumor cell lysis. Furthermore, the potential of TQ as

an immunomodulatory agent with anticancer effects is supported by

the observed upregulation of NK cell cytotoxicity in its presence.

Future research should clarify the precise molecular mechanisms by

which TQ improves NK cell function, including its effects on

activation receptors, cytokine production and intracellular

signaling pathways, in order to build on the present findings.

Clinical trials and in vivo research are also necessary to

confirm the therapeutic potential of TQ in a physiological setting

and evaluate its safety and effectiveness when used in conjunction

with currently available immunotherapies. Furthermore,

investigating the impact of TQ on different subtypes of PC and its

association with the tumor microenvironment may elucidate its

suitability for personalized medicine.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Samar A. Zailaie

(King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Jeddah) for

technical assistance and scientific advice.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NIT and NuAA contributed to the study design. NoAA

performed the study. NAK and HFA performed the data analysis. NIT,

NuAA and HFA performed the data interpretation. HFA and NoAA

drafted the manuscript. NIT, NoAA, HFA and NuAA revised the

manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. NIT and

NuAA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Biomedical

Ethics Research Committee of King Abdulaziz University Faculty of

Medicine (approval no. No640-20). Written informed consent was

obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Omran AR: The epidemiological transition:

A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Millbank Mem

Fund Q. 49:509–538. 1971. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M,

Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I and Bray F;

Global Cancer Observatory, : World. International Agency for

Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdfDecember

26–2024

|

|

3

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Panigrahi GK, Praharaj PP, Kittaka H,

Mridha AR, Black OM, Singh R, Mercer R, van Bokhoven A, Torkko KC,

Agarwal C, et al: Exosome proteomic analyses identify inflammatory

phenotype and novel biomarkers in African American prostate cancer

patients. Cancer Med. 8:1110–1123. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rawla P: Epidemiology of prostate cancer.

World J Oncol. 10:63–89. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chan JM, Gann PH and Giovannucci EL: Role

of diet in prostate cancer development and progression. J Clin

Oncol. 23:8152–8160. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Michaud DS,

Willett WC and Giovannucci E: Interrelation of energy intake, body

size, and physical activity with prostate cancer in a large

prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 63:8542–8548. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hegde PS and Chen DS: Top 10 challenges in

cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 52:17–35. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lopez-Bujanda Z and Drake CG:

Myeloid-derived cells in prostate cancer progression: Phenotype and

prospective therapies. J Leukoc Biol. 102:393–406. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS,

Sboner A, MacDonald TY, Wang Y, Sheikh KL, Terry S, Tagawa ST, et

al: Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer

and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 1:487–495.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C and

Galon J: The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical

outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:298–306. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

O'Donnell JS, Teng MWL and Smyth MJ:

Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy.

Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16:151–167. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pardoll DM: The blockade of immune

checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:252–264.

2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H,

Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Patnaik A, Powell SF, Gentzler RD, Martins

RG, Stevenson JP, Jalal SI, et al: Carboplatin and pemetrexed with

or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell

lung cancer: A randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label

KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol. 17:1497–1508. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Patel SH, Rimner A and Cohen RB: Combining

immunotherapy and radiation therapy for small cell lung cancer and

thymic tumors. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 6:186–195. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Orange JS and Ballas ZK: Natural killer

cells in human health and disease. Clin Immunol. 118:1–10. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T

and Ugolini S: Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol.

9:503–510. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Doherty DG and O'Farrelly C: Innate and

adaptive lymphoid cells in the human liver. Immunol Rev. 174:5–20.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Joyce JA and Pollard JW:

Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:239–252. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ferlazzo G, Pack M, Thomas D, Paludan C,

Schmid D, Strowig T, Bougras G, Muller WA, Moretta L and Münz C:

Distinct roles of IL-12 and IL-15 in human natural killer cell

activation by dendritic cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:16606–16611. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Romagnani C, Juelke K, Falco M, Morandi B,

D'Agostino A, Costa R, Ratto G, Forte G, Carrega P, Lui G, et al:

CD56brightCD16- killer Ig-like receptor-NK cells display longer

telomeres and acquire features of CD56dim NK cells upon activation.

J Immunol. 178:4947–4955. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cooper MA, Fehniger TA and Caligiuri MA:

The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol.

22:633–640. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Domaica CI, Sierra JM, Zwirner NW and

Fuertes MB: Immunomodulation of NK cell activity. Methods Mol Biol.

2097:125–136. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Balsamo M, Scordamaglia F, Pietra G,

Manzini C, Cantoni C, Boitano M, Queirolo P, Vermi W, Facchetti F,

Moretta A, et al: Melanoma-associated fibroblasts modulate NK cell

phenotype and antitumor cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:20847–20852. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee HH and Cho H: Improved anti-cancer

effect of curcumin on breast cancer cells by increasing the

activity of natural killer cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol.

28:874–882. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Montagner IM, Penna A, Fracasso G,

Carpanese D, Dalla Pietà A, Barbieri V, Zuccolotto G and Rosato A:

Anti-PSMA CAR-engineered NK-92 cells: An off-the-shelf cell therapy

for prostate cancer. Cells. 9:13822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lundholm M, Schröder M, Nagaeva O, Baranov

V, Widmark A, Mincheva-Nilsson L and Wikström P: Prostate

tumor-derived exosomes down-regulate NKG2D expression on natural

killer cells and CD8+ T cells: Mechanism of immune evasion. PLoS

One. 9:e1089252014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Levy EM, Roberti MP and Mordoh J: Natural

killer cells in human cancer: From biological functions to clinical

applications. Biomed Res Int. 2011:6761982011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Tian T and Li Z: Targeting Tim-3 in cancer

with resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Front Oncol. 11:7311752021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Siemińska I and Baran J: Myeloid-derived

suppressor cells as key players and promising therapy targets in

prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8624162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Modena A, Ciccarese C, Iacovelli R,

Brunelli M, Montironi R, Fiorentino M, Tortora G and Massari F:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors and prostate cancer: A new frontier?

Oncol Rev. 10:2932016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki

A, Nakamura Y, Sato E, Fukuoka S, Tada Y, Tanaka A, et al: PD-1(+)

regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote

hyperprogression of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:9999–10008.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Quatrini L, Mariotti FR, Munari E, Tumino

N, Vacca P and Moretta L: The immune checkpoint PD-1 in natural

killer cells: Expression, function and targeting in tumour

immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 12:32852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Majdalawieh AF and Fayyad MW: Recent

advances on the anti-cancer properties of Nigella sativa, a widely

used food additive. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 7:173–180. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dajani EZ, Shahwan TG and Dajani NE:

Overview of the preclinical pharmacological properties of Nigella

sativa (black seeds): A complementary drug with historical and

clinical significance. J Physiol Pharmacol. 67:801–817.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bayır AG and Karakaş I: The Role of

Nigella sativa and Its Active Component Thymoquinone in

Cancer Prevention and Treatment: A Review Article. Eurasian J Med

Biol Sci. 1:1–12. 2021.

|

|

38

|

Ramadan MF: Nutritional value, functional

properties and nutraceutical applications of black cumin (Nigella

sativa L.): An overview. Int J Food Sci Technol. 42:1208–1218.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

AlShaibi HF, Ahmed F, Buckle C, Fowles

ACM, Awlia J, Cecchini MG and Eaton CL: The BMP antagonist Noggin

is produced by osteoblasts in response to the presence of prostate

cancer cells. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 65:407–418. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Randhawa MA and Alghamdi MS: Anticancer

activity of Nigella sativa (black seed)-a review. Am J Chin Med.

39:1075–1091. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schneider-Stock R, Fakhoury IH, Zaki AM,

El-Baba CO and Gali-Muhtasib HU: Thymoquinone: Fifty years of

success in the battle against cancer models. Drug Discov Today.

19:18–30. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Khan MA, Tania M, Fu S and Fu J:

Thymoquinone, as an anticancer molecule: From basic research to

clinical investigation. Oncotarget. 8:519072017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Khan MA, Tania M, Wei C, Mei Z, Fu S,

Cheng J, Xu J and Fu J: Thymoquinone inhibits cancer metastasis by

downregulating TWIST1 expression to reduce epithelial to

mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 6:19580–19591. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Majdalawieh AF, Hmaidan R and Carr RI:

Nigella sativa modulates splenocyte proliferation, Th1/Th2 cytokine

profile, macrophage function and NK anti-tumor activity. J

Ethnopharmacol. 131:268–275. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sjs B, Kavithaa K, Poornima A, Haribalan

P, Renukadevi B and Sumathi S: Modulation of gene expression by

thymoquinone conjugated zinc oxide nanoparticles arrested cell

cycle, DNA damage and increased apoptosis in triple negative breast

cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 47:1–19. 2022.

|

|

46

|

Alshaibi HF, Aldarmahi NA, Alkhattabi NA,

Alsufiani HM and Tarbiah NI: Studying the anticancer effects of

thymoquinone on breast cancer cells through natural killer cell

activity. Biomed Res Int. 2022:92186402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Murphy EM, Centner CS, Bates PJ, Malik MT

and Kopechek JA: Delivery of thymoquinone to cancer cells with

as1411-conjugated nanodroplets. PLoS One. 15:e02334662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Peng L, Liu A, Shen Y, Xu HZ, Yang SZ,

Ying XZ, Liao W, Liu HX, Lin ZQ, Chen QY, et al: Antitumor and

anti-angiogenesis effects of thymoquinone on osteosarcoma through

the NF-κB pathway. Oncol Rep. 29:571–578. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Waggoner SN, Daniels KA and Welsh RM:

Therapeutic depletion of natural killer cells controls persistent

infection. J Virol. 88:1953–1960. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Krebs P, Barnes MJ, Lampe K, Whitley K,

Bahjat KS, Beutler B, Janssen E and Hoebe K: NK cell-mediated

killing of target cells triggers robust antigen-specific T

cell-mediated and humoral responses. Blood. 113:6593–6602. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Karim S, Burzangi AS, Ahmad A, Siddiqui

NA, Ibrahim IM, Sharma P, Abualsunun WA and Gabr GA: PI3K-AKT

pathway modulation by thymoquinone limits tumor growth and

glycolytic metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

23:23052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Khan A, Alsahli MA, Aljasir MA, Maswadeh

H, Mobark MA, Azam F, Allemailem KS, Alrumaihi F, Alhumaydhi FA,

Almatroudi AA, et al: Experimental and theoretical insights on

chemopreventive effect of the liposomal thymoquinone against benzo

[a] pyrene-induced lung cancer in swiss albino mice. J Inflamm Res.

15:2263–2280. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Mirzaei S, Zarrabi A, Hashemi F, Zabolian

A, Saleki H, Ranjbar A, Saleh SH, Bagherian M, Sharifzadeh SO,

Hushmandi K, et al: Regulation of nuclear factor-KappaB (NF-κB)

signaling pathway by non-coding RNAs in cancer: Inhibiting or

promoting carcinogenesis? Cancer Lett. 509:63–80. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang N and Bevan MJ: CD8+ T cells: Foot

soldiers of the immune system. Immunity. 35:161–168. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ibrahim S, Fahim SA, Tadros SA and Badary

OA: Suppressive effects of thymoquinone on the initiation stage of

diethylnitrosamine hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. J Biochem Mol

Toxicol. 36:e230782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang B, Ting WJ, Gao J, Kang ZF, Huang CY

and Weng YJ: Erk phosphorylation reduces the thymoquinone toxicity

in human hepatocarcinoma. Environ Toxicol. 36:1990–1998. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang R, Wu T, Zheng P, Liu M, Xu G, Xi M

and Yu J: Thymoquinone sensitizes human hepatocarcinoma cells to

TRAIL-induced apoptosis via oxidative DNA damage. DNA Repair

(Amst). 103:1031172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Narayanan P, Farghadani R, Nyamathulla S,

Rajarajeswaran J, Thirugnanasampandan R and Bhuwaneswari G: Natural

quinones induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and inhibit cell migration

in PANC-1 human pancreatic cancer cell line. J Biochem Mol Toxicol.

36:e230082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang M, Du H, Wang L, Yue Y, Zhang P,

Huang Z, Lv W, Ma J, Shao Q, Ma M, et al: Thymoquinone suppresses

invasion and metastasis in bladder cancer cells by reversing EMT

through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact.

320:1090222020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sutton VR, Davis JE, Cancilla M, Johnstone

RW, Ruefli AA, Sedelies K, Browne KA and Trapani JA: Initiation of

apoptosis by granzyme B requires direct cleavage of bid, but not

direct granzyme B-mediated caspase activation. J Exp Med.

192:1403–1414. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shimasaki N, Jain A and Campana D: NK

cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 19:200–218.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Smyth MJ, Cretney E, Kelly JM, Westwood

JA, Street SE, Yagita H, Takeda K, van Dommelen SL, Degli-Esposti

MA and Hayakawa Y: Activation of NK cell cytotoxicity. Mol Immunol.

42:501–510. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Health

Council, National Cancer Center, Saudi Cancer Registry, . Cancer

Incididence Report Saudi Arabia 2020. https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/NewNCC/Activities/AnnualReports/2020.pdfJanuary

5–2025

|

|

64

|

Chowdhury D and Lieberman J: Death by a

thousand cuts: Granzyme pathways of programmed cell death. Annu Rev

Immunol. 26:389–420. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Young JD, Hengartner H, Podack ER and Cohn

ZA: Purification and characterization of a cytolytic pore-forming

protein from granules of cloned lymphocytes with natural killer

activity. Cell. 44:849–859. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Singh SK, Mishra MK, Lillard JW and Singh

R: Thymoquinone enhanced the tumoricidal activity of NK cells

against lung cancer. J Immunol. 200 (Supplement_1):S124–S125. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Sethi G, Ahn KS and Aggarwal BB: Targeting

nuclear factor-κB activation pathway by thymoquinone: role in

suppression of antiapoptotic gene products and enhancement of

apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 6:1059–1070. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Sadeghi E, Imenshahidi M and Hosseinzadeh

H: Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways of black cumin

(Nigella sativa) and its active constituent, thymoquinone: A

review. Mol Biol Rep. 50:5439–5454. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|