Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related

deaths in the developed world, with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

being the most prevalent histological type. Various grading methods

based on a histological perspective have been proposed to predict

prognosis. The micropapillary subtype is a high-grade histological

element that serves as a marker of poor prognosis (1,2),

particularly among patients with EGFR-mutated LUAD (3). We previously suggested that the

micropapillary element may develop from a pure lepidic type

via intermediate forms exhibiting a low papillary structure

(4). The 5th edition of the World

Health Organization (WHO) classification defines this low papillary

structure as a filigree pattern, consisting of tumor cells growing

in delicate, lace-like, narrow stacks of three cells without

fibrovascular cores (5). As the

filigree and micropapillary patterns exhibit comparable malignant

potential, the filigree type should be classified as a variant of

the micropapillary element (6).

This supported our theory and has prompted us to investigate the

molecular basis of the lepidic-filigree micropapillary

(filigree)-conventional/overt micropapillary (mPAP) progression

pathway.

The Visium Spatial Gene Expression Profiling System

(10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) has facilitated comparisons of

mRNA expression among various histologically distinct elements from

a single tissue section (7).

Conventional methods compare mRNA levels between tissue elements

within a single tumor by separately isolating RNA from each region

using microdissection. However, LUAD is histologically

heterogeneous within a single tumor, limiting the effectiveness of

conventional methods for analyzing spatial gene expression.

Notably, the Visium Spatial Gene Expression Profiling System

compares different histological elements while preserving

morphological information within a single tissue section (8). Recently, detailed analysis using the

Visium spatial transcriptomics platform has revealed the mechanism

by which lung tumors develop through interactions with their

surrounding microenvironment (9).

In the present study, we aimed to identify key

molecules promoting LUAD progression using the Visium Spatial Gene

Expression Solution, which offers better resolution than

microdissection. We examined gene expression profiles specific to

lepidic, filigree, and mPAP elements in identical histological

sections to reveal key molecules that promote the

lepidic-filigree-mPAP pathway.

Materials and methods

Patients

All LUAD tissues analyzed in this study were

surgically resected at the Kanagawa Prefectural Cardiovascular and

Respiratory Center between January 1997 and December 2022. The

proportion of smokers in lung adenocarcinoma in our study [50.5%

(104/207)] was comparable with the previous study investigating

Japanese cohort (56.2–61.9%) (10–12).

For the prognostic analysis, patients with lung cancer who

underwent surgery between 1997 and 2014 were included. All patients

provided written informed consent for the use of these samples for

research purposes. This study was approved by the ethics committee

at the Kanagawa Prefectural Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center

[Approval ID: KCRC-17-0016; October 1, 2018] and the materials

(patient tissues and data) were used based on a mixed retrospective

and prospective study design.

Histopathological analyses

Formalin-fixed paraffin- embedded (FFPE) tissue

sections were sliced and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

The proportions of the histological elements (lepidic, acinar,

papillary, mPAP, and solid elements) were recorded in 5% increments

according to the WHO classification (5). The filigree pattern was classified as

part of the micropapillary subtype (6,13).

Spatial gene expression profiling

Four LUAD samples were analyzed using the Visium

Spatial Gene Expression Profiling System (10× Genomics, Pleasanton,

CA, USA). Briefly, the quality of RNA was analyzed using FFPE

slides, and all samples that satisfied the DV200 requirement as a

standard of RNA integrity were then subjected to the adhesion test.

Eight tissue sections (n=2 each from the four LUAD samples) that

included lepidic, filigree, and mPAP elements were mounted onto

Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slides in oligo-barcoded capture

areas (6.5×6.5 mm). Sequencing libraries were generated using

Visium Spatial Gene Expression kits, followed by spatial transcript

analysis using Visium Spatial Gene Expression Solution (10×

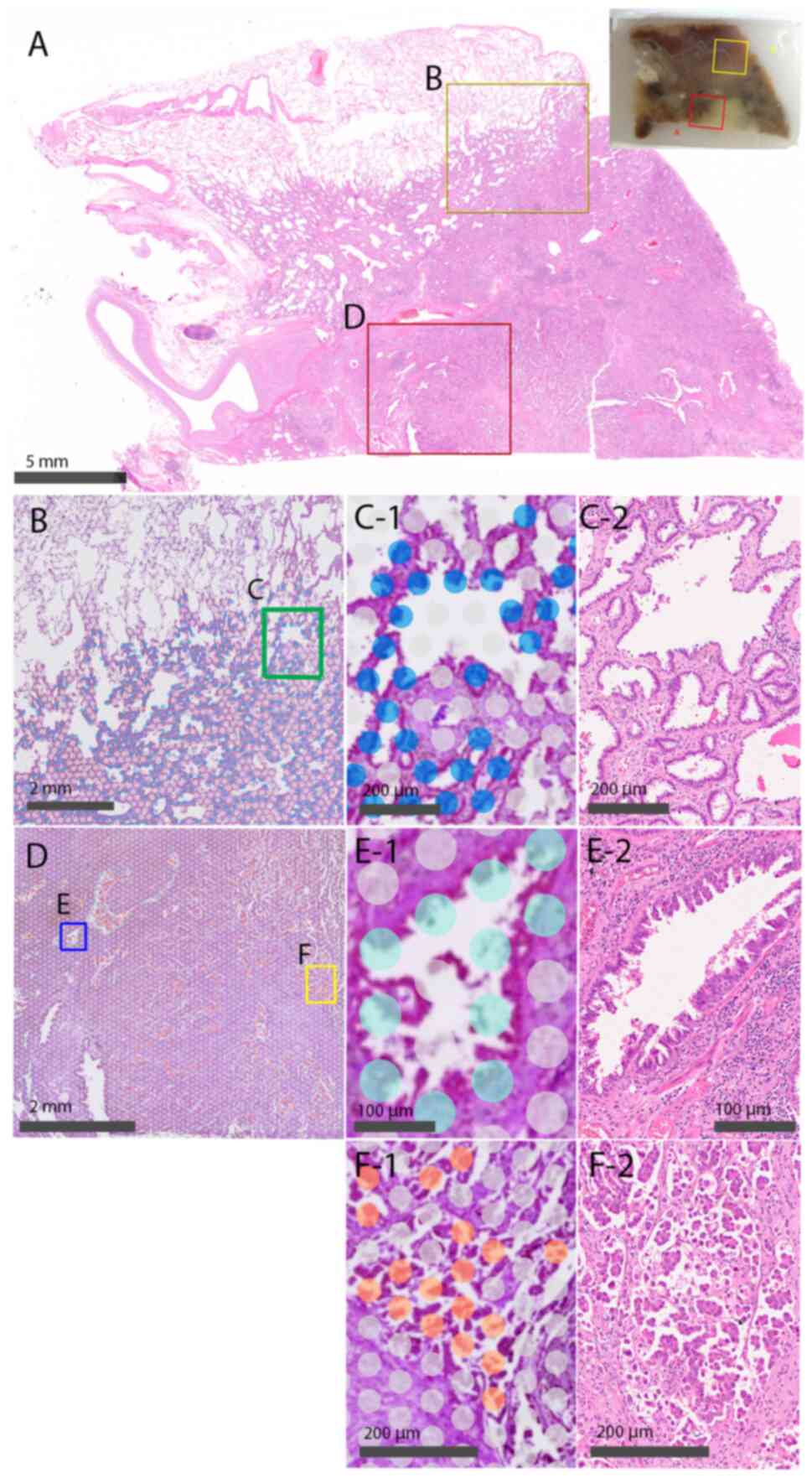

Genomics) (Fig. 1). The Visium

Spatial Gene Expression Profiling System contains approximately

5,000 circular spots with a diameter of 55 µm within a 6.5×6.5

mm2 analysis area on an FFPE slide, with each spot

containing 3–5 cells. RNA transcriptome data were obtained from

individual spots corresponding to each histological element

(Fig. 1C-1: lepidic element, D-1:

filigree element, E-1: mPAP element). Quantitative gene expression

data were normalized and mapped onto tissue sections using a Bio

Turing Lens (Bio Turing, San Diego, CA, USA). The mRNA levels in

the lepidic, filigree, and mPAP components were then compared and

analyzed. Differentially expressed genes among the three elements

were identified using t-tests with significance criteria set at

fold change (FC) >1.5 and a false discovery rate (FDR)

<0.05.

Immunohistochemical analyses

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 207

surgically resected LUAD samples. FFPE tissue sections were

incubated with primary antibodies against cellular retinoic acid

binding protein 2 (CRABP2; polyclonal; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis,

MO, USA), carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5

(CEACAM5; clone CB30; Lifespan Biosciences, Washington, DC, USA),

and mucin 21 (MUC21; polyclonal; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO,

USA). The slides were autoclaved to retrieve antigens, and

immunoreactivity was then visualized using Simple Stain MAX-PO

(MULTI; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). The reactions were further

developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with

hematoxylin. The intensity of CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21 staining

in neoplastic cells was judged as negative (0), weak (1), or strong (2) and scored as: 1× (proportion of area

with weak intensity) + 2× (proportion of area with strong intensity

(%, in 5% increments).

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were

respectively analyzed using Pearson chi-square tests or Fisher

exact tests, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple

comparison test and the Cox proportional hazards model. Receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves of recurrence were generated

to establish a cut-off to distinguish ‘high’ from ‘low’

immunohistological scores. Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrence and

survival were plotted, and differences in recurrence-free survival

(RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were analyzed using log-rank

tests. Values with P<0.05 were considered significant. All data

were statistically analyzed using JMP 9.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary,

NC, USA).

Results

Changes in gene expression in each

LUAD subtype

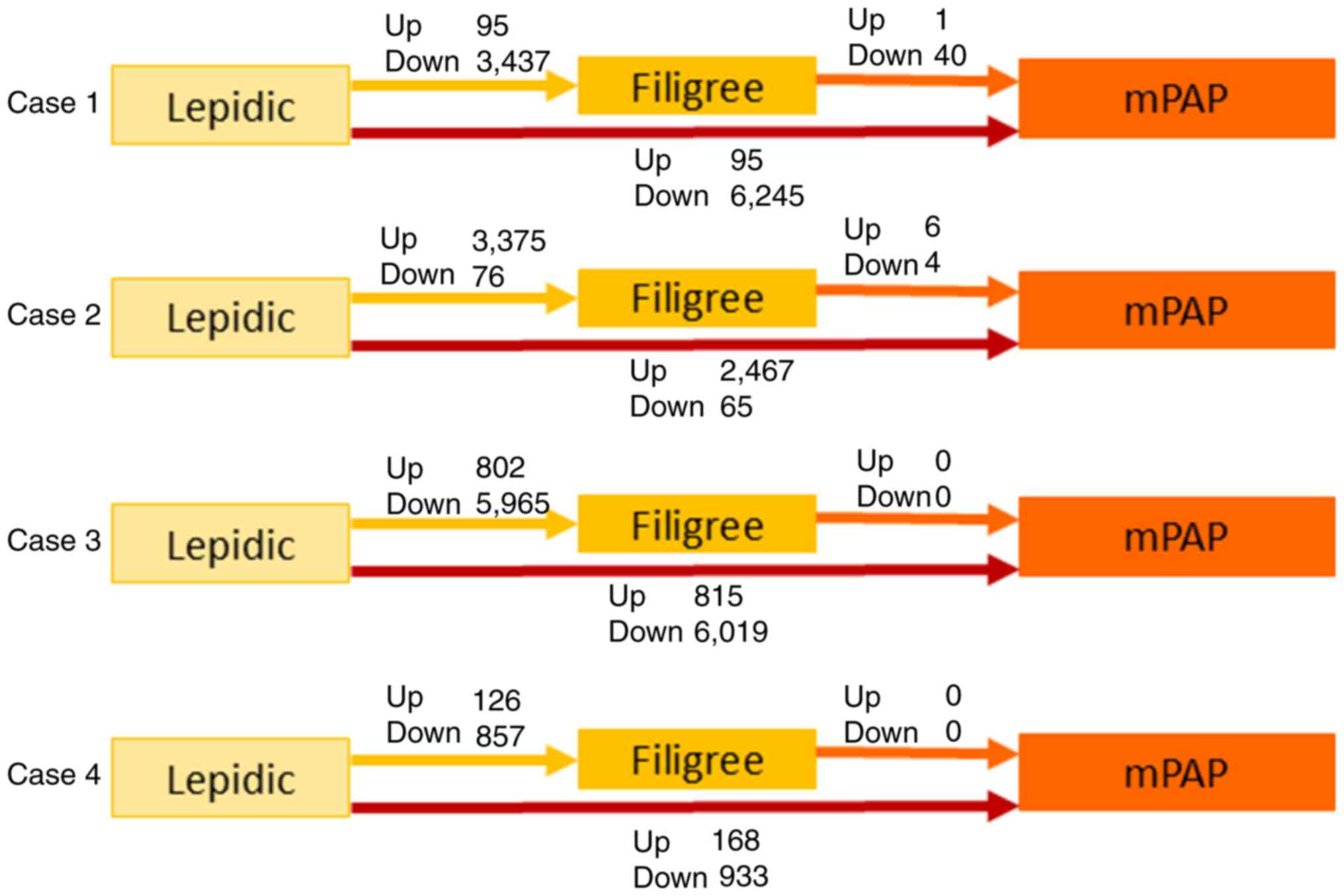

The number of differentially expressed genes was

considerably higher during the transition from lepidic to filigree

than from filigree to mPAP among all four cases (Fig. 2). This result suggests that the gene

expression profile primarily changes during the early stages of the

progression.

Differentially expressed genes during

the lepidic-filigree-mPAP progression

Among the four cases, three genes (CRABP2,

CEACAM5, and MUC21) were commonly upregulated during the

transition from lepidic to mPAP elements (Table SI, Table SII, Table SIII). Notably, CRABP2 was

upregulated in the early stage (from lepidic to filigree elements).

Conversely, 14 genes were commonly downregulated during the

transition from lepidic to mPAP elements, whereas 6 genes were

downregulated during the transition from lepidic to filigree

elements (Table SIV, Table V, Table SVI).

Immunohistochemical expression of

CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21 in different histological elements

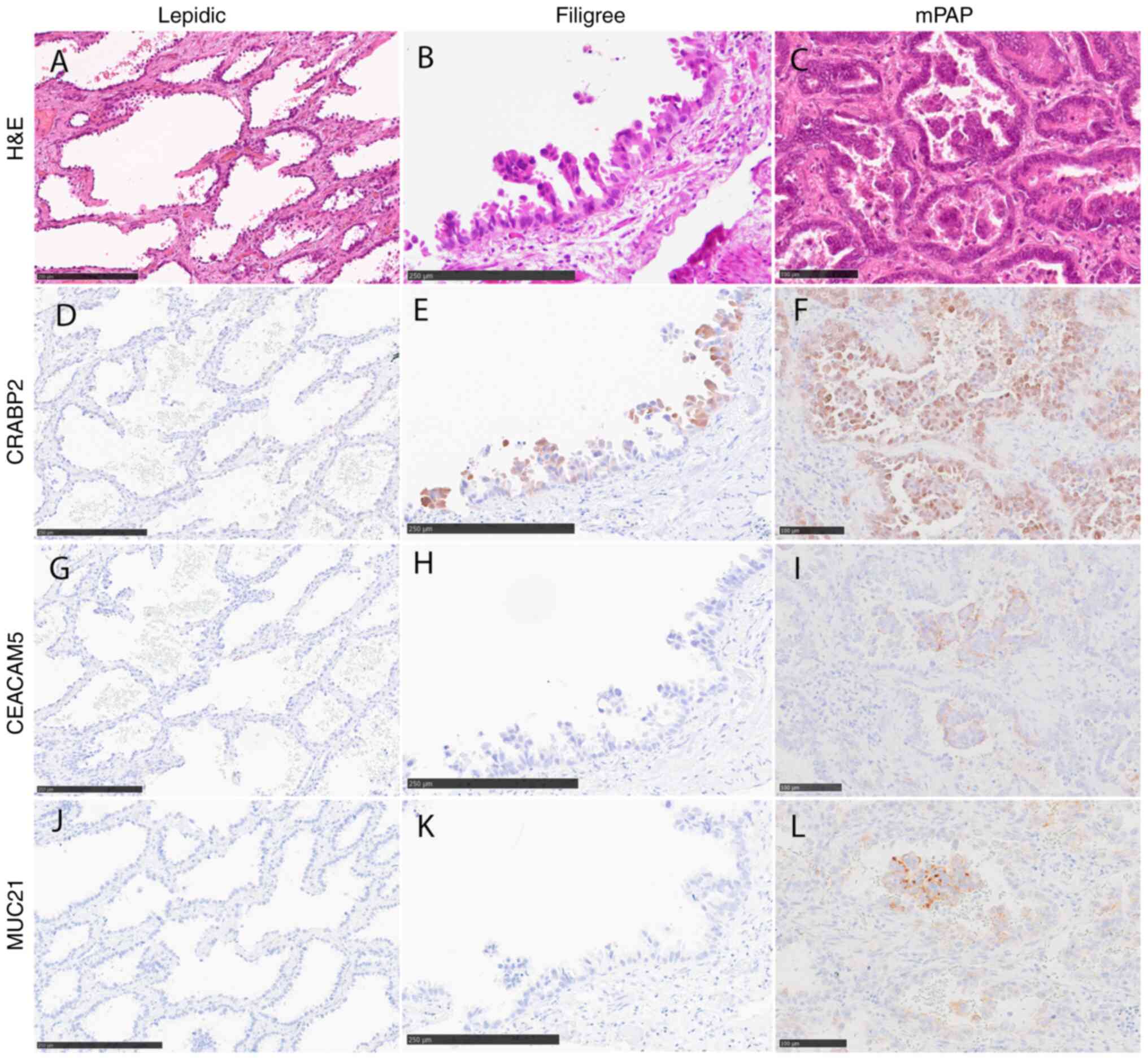

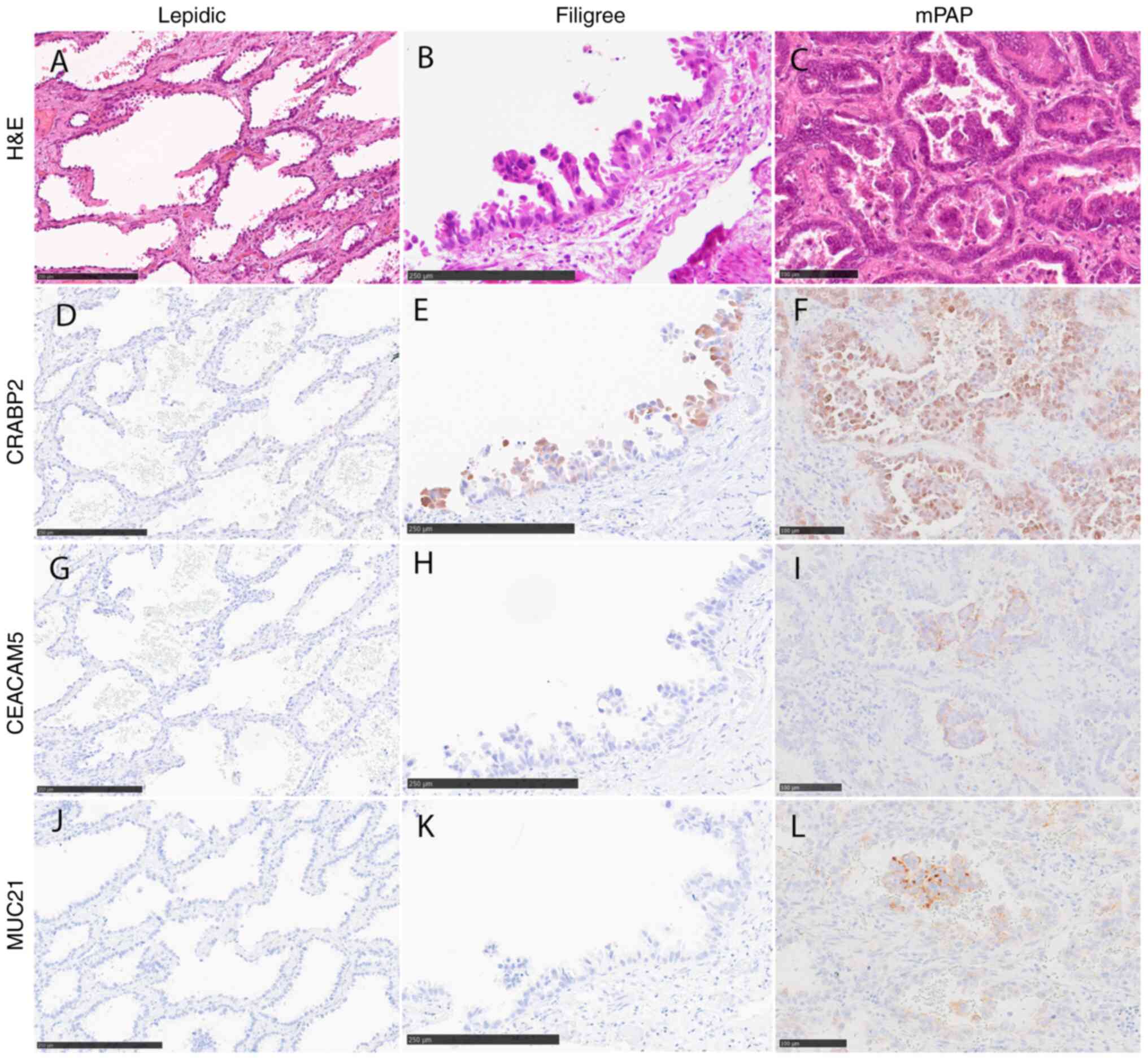

Among the identified genes, we focused on

three-CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21- and examined their

protein expression in a larger cohort of LUAD cases using

immunohistochemical analysis (Fig.

3). CRABP2 was preferentially expressed both in filigree and

mPAP elements (Fig. 3E and F).

Conversely, CEACAM5 and MUC21 expression was specific to mPAP

elements, with positive rates were 50.6% (39/77) and 66.2% (51/77),

respectively (Fig. 3I and L).

Positive immunohistochemical signals for CEACAM5 and MUC21 revealed

predominantly negative staining in the filigree element, with

positive rates of 38.7% (60/155) and 21.3% (33/155), respectively

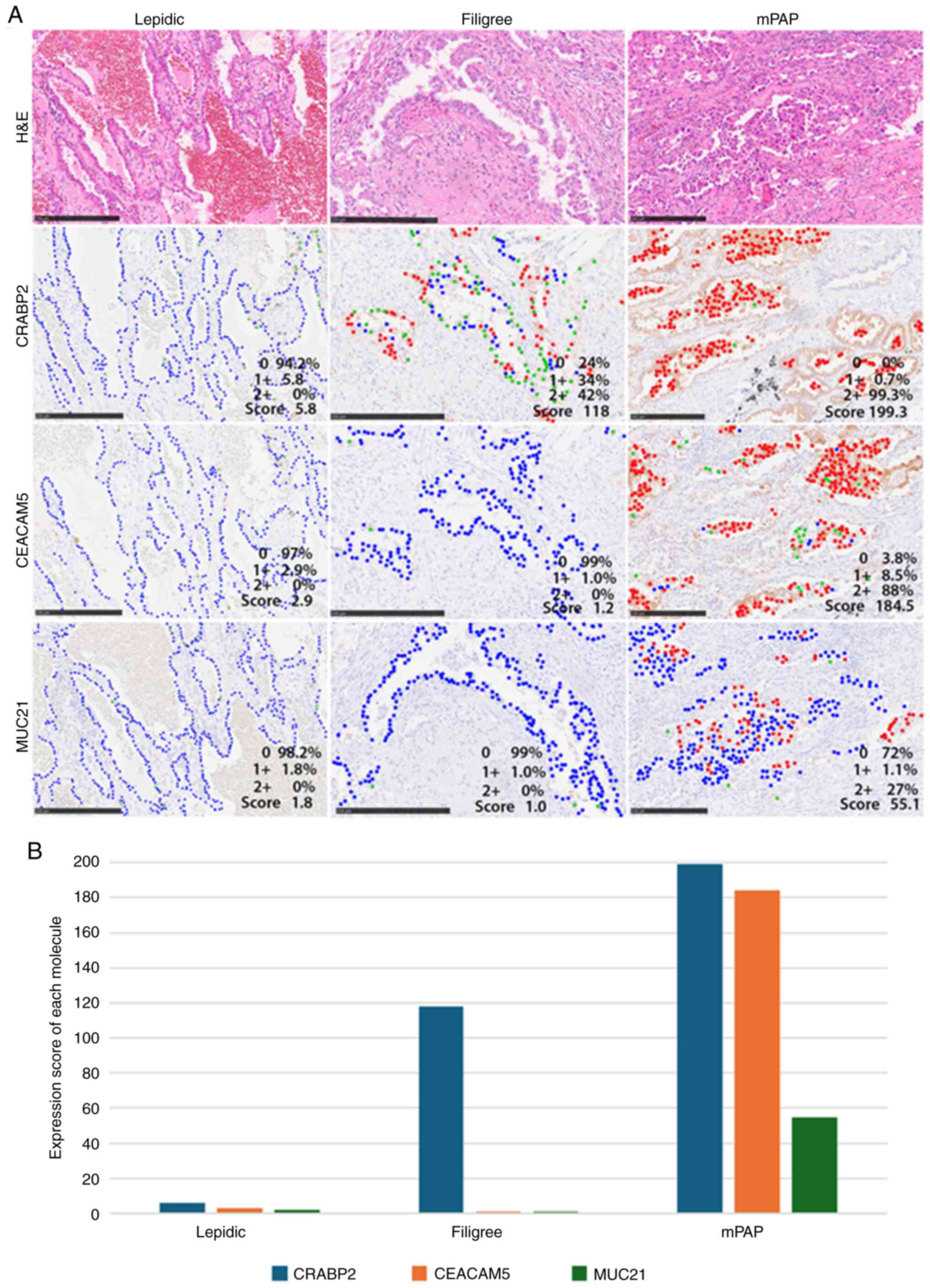

(Fig. 3H and K). To confirm this

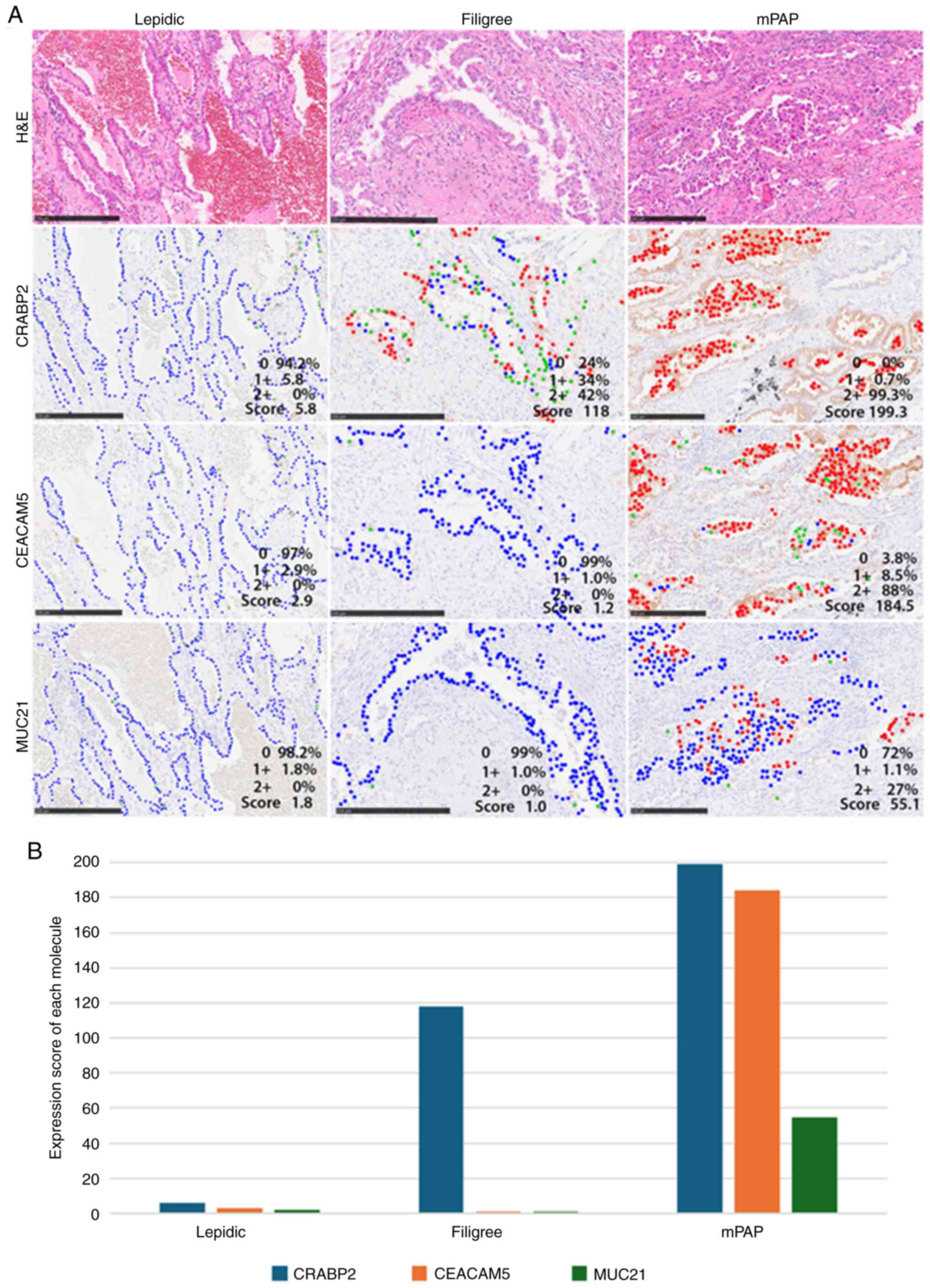

observation, we semi-quantified the immunohistochemical expression

levels in the different histological elements, including lepidic,

filigree, acinar, papillary, mPAP, and solid elements, using a

scoring system (as described in the Materials and Methods).

Representative images of tumors with varying immunohistochemical

scores are presented in Fig. 4.

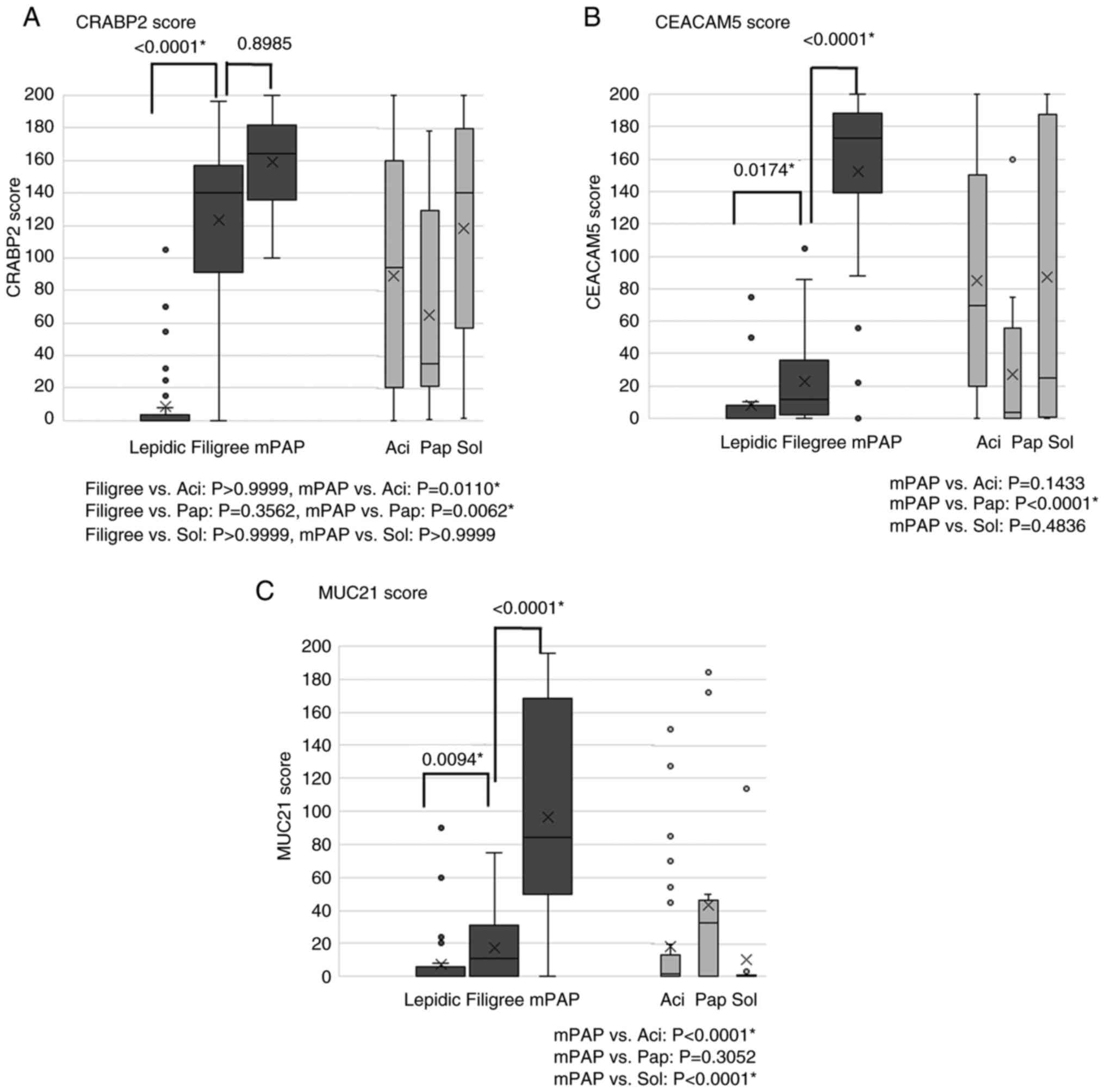

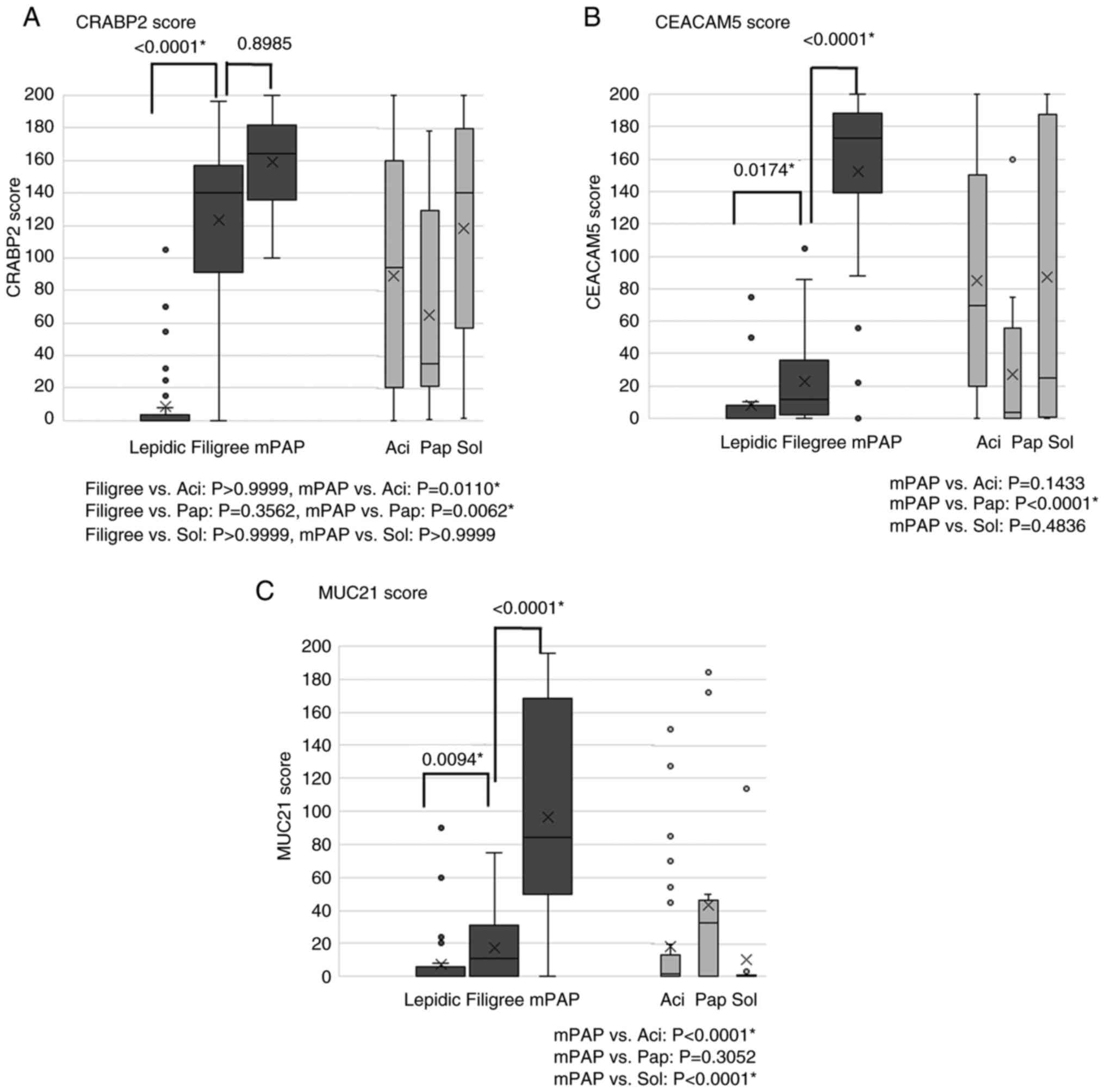

Consistent with our initial observation, the scores of CRABP2 were

significantly higher in filigree than lepidic elements; however, no

significant difference was observed between mPAP and filigree

elements (Fig. 5A). The scores of

CEACAM5 and MUC21 were significantly higher in mPAP than in

filigree elements, and the scores of these were significantly

higher in filigree than in lepidic elements (Fig. 5B and C). The increase in the CRABP2

score between lepidic and filigree elements was considerably larger

than that in CEACAM5 or MUC21 expression scores (Fig. 5). This result suggests that CRABP2

may play a role in the earlier stages of the lepidic-filigree-mPAP

progression. High scores of CRABP2 and CEACAM5 were also observed

in solid elements, another high-grade element, as well as mPAP

elements (Fig. 5A and B). In some

cases, CRABP2 and CEACAM5 expression was observed in the acinar and

papillary elements. However, the expression scores in these

elements were lower than those in filigree and/or mPAP elements

(Fig. 5A and B). The expression

score of MUC21 was consistently lower in the papillary, acinar, and

solid elements than in the filigree and mPAP components (Fig. 5). The expression of CRABP2,

CEACAM15, and MUC21 was not detected in non-neoplastic bronchiolar

and alveolar epithelial cells.

| Figure 3.Representative images of CRABP2,

CEACAM5 and MUC21 immunohistochemical staining. (A) Lepidic, (B)

filigree and (C) mPAP elements stained with H&E. (D) CRABP2,

(G) CEACAM5 and (J) MUC21 were rarely expressed in lepidic

elements. CRABP2 was expressed in (E) filigree and (F) mPAP

elements. (I) CEACAM5 and (L) MUC21 were expressed only in mPAP

elements. (H) CEACAM5 and (K) MUC21 were rarely expressed in

filigree elements. Scale bar, 250 µm (A, B, D, E, G, H, J and K) or

100 µm (C, F, I and L). CEACAM5, carcinoembryonic antigen-related

cell adhesion molecule 5; CRABP2, cellular retinoic acid binding

protein 2; mPAP, conventional/overt micropapillary; MUC21, mucin

21. |

| Figure 4.Representative images of tumors with

various immunohistochemical scores. Red, green and blue dots

indicate tumor cells with strong, weak and no signals (intensity,

2, 1 and 0, respectively) (A) Lepidic elements (left) rarely

exhibited positive signals for each antibody (CRABP2, CEACAM5 and

MUC21 scores: 5.8, 2.9 and 1.8). Filigree elements (center) showed

some strong and weak CRABP2 signals in most neoplastic cells

(score, 118=1×34+2×42). Signals for CEACAM5 and MUC21 were rarely

positive (scores, 1.2 and 1.0, respectively). mPAP elements (right)

exhibited stronger signals in most neoplastic cells for CRABP2,

CEACAM5 and MUC21 than the other elements (lepidic and filigree)

(scores, 199.3=1×0.7+2×99.3, 184.5=1×8.5+2×88 and 55.1=1×1.1+2×27,

respectively). Scale bar, 250 µm. (B) All scores were low in

lepidic elements. Only the expression score for CRABP2 was high in

the filigree element, whereas the scores for all three proteins

were high in mPAP elements. CEACAM5, carcinoembryonic

antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5; CRABP2, cellular retinoic

acid binding protein 2; mPAP, conventional/overt micropapillary;

MUC21, mucin 21. |

| Figure 5.Association between histological

elements and CRABP2, CEACAM5 and MUC21 immunohistochemical scores.

(A) The CRABP2 score was significantly higher in filigree elements

than in lepidic elements (P<0.0001) but no significant

difference was observed between mPAP elements and filigree elements

(P=0.8985). (B) The CEACAM5 score was significantly higher in

filigree elements than in lepidic elements (P=0.0174) and

significantly higher in mPAP elements than in filigree elements

(P<0.0001). This difference was more significant between

filigree and mPAP elements than between filigree and lepidic

elements. (C) The MUC21 score was significantly higher in filigree

elements than in lepidic elements (P=0.0094) and significantly

higher in mPAP elements than in filigree elements (P<0.0001).

This difference was more significant between filigree and mPAP

elements than between filigree and lepidic elements.

Box-and-whisker plots show immunohistochemical scores for 50

surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma cases (median, thick line;

25th-75th percentiles, box; 10th-90th percentiles, whiskers;

outliers, dots). P<0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's

multiple comparison test). *Statistically significant. Aci, acinar;

CEACAM5, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5;

CRABP2, cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2; mPAP,

conventional/overt micropapillary; MUC21, mucin 21; Pap, papillary;

Sol, solid. |

Cut-off values for ‘high’ and ‘low’

immunohistochemical scores

The optimal cut-off immunohistochemical scores for

CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21, determined using ROC curves, were 100,

50, and 80, respectively. We then categorized the samples as ‘high’

or ‘low expressors’ in subsequent correlation analyses.

Relationship among CRABP2, CEACAM5,

and MUC21 immunohistochemical levels and clinicopathological

characteristics

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 207

LUAD cases are presented in Table

I. High CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21 expression levels were

significantly related to EGFR mutations (Table I). Additionally, high MUC21

expression was significantly associated with a non-smoking status

(Table I).

| Table I.Relationships between CRABP2, CEACAM5

and MUC21 expression and clinicopathological factors in lung

adenocarcinoma. |

Table I.

Relationships between CRABP2, CEACAM5

and MUC21 expression and clinicopathological factors in lung

adenocarcinoma.

|

| CRABP2 | CEACAM5 | MUC21 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathological

factors | Low expression

(N=90) | High expression

(N=117) | P-value | Low expression

(N=93) | High expression

(N=114) | P-value | Low expression

(N=169) | High expression

(N=38) | P-value |

|---|

| Age |

|

| 0.7698 |

|

| 0.6693 |

|

| 0.4535 |

| Young

(≤65 years), % (n) | 36.7 (33) | 34.2 (40) |

| 37.6 (35) | 33.3 (38) |

| 36.7 (62) | 28.9 (11) |

|

| Older

(>65 years), % (n) | 63.3 (57) | 65.8 (77) |

| 62.4 (58) | 66.7 (76) |

| 63.3 (107) | 71.1 (27) |

|

| Median,

years (range) | 69 (47–84) | 69 (36–86) |

| 67 (38–85) | 69 (36–86) |

| 68 (36–86) | 72 (47–83) |

|

| Sex, % (n) |

|

| 0.3247 |

|

| 0.5758 |

|

| 0.1502 |

|

Female | 58.9 (53) | 51.3 (60) |

| 57.0 (53) | 52.6 (60) |

| 52.1 (88) | 65.8 (25) |

|

|

Male | 41.1 (37) | 48.7 (57) |

| 43.0 (40) | 47.4 (54) |

| 47.9 (81) | 34.2 (13) |

|

| Smoking status, %

(n) |

|

| 0.7799 |

|

| 0.2645 |

|

| 0.0122a |

| Never

smoked | 51.1 (46) | 48.7 (57) |

| 45.2 (42) | 53.5 (61) |

| 45.6 (77) | 68.4 (26) |

|

|

Smoking | 48.9 (44) | 51.3 (60) |

| 54.8 (51) | 46.5 (53) |

| 54.4 (92) | 31.6 (12) |

|

| Tumor size, %

(n) |

|

| 0.3961 |

|

| 0.1194 |

|

| >0.9999 |

| ≤20

mm | 45.6 (41) | 39.3 (46) |

| 48.4 (45) | 36.8 (42) |

| 42.0 (71) | 42.1 (16) |

|

| >20

mm | 54.4 (49) | 60.7 (71) |

| 51.6 (48) | 63.2 (72) |

| 58.0 (98) | 57.9 (22) |

|

| Lymphatic invasion,

% (n) |

|

|

<0.0001a |

|

| 0.0171a |

|

| 0.0112a |

|

Present | 38.9 (35) | 66.7 (78) |

| 45.2 (42) | 62.3 (71) |

| 50.3 (85) | 73.7 (28) |

|

|

Absent | 61.1 (55) | 33.3 (39) |

| 54.8 (51) | 37.7 (43) |

| 49.7 (84) | 26.3 (10) |

|

| Vascular invasion,

% (n) |

|

| 0.0007a |

|

| 0.0334a |

|

| 0.5646 |

|

Present | 17.8 (16) | 40.2 (47) |

| 22.6 (21) | 36.8 (42) |

| 29.6 (50) | 34.2 (13) |

|

|

Absent | 82.2 (74) | 59.8 (70) |

| 77.4 (72) | 63.2 (72) |

| 70.4 (119) | 65.8 (25) |

|

| pStage, % (n) |

|

| 0.0020a |

|

| 0.0117a |

|

| 0.0343a |

| IA,

IB | 91.1 (82) | 74.4 (87) |

| 89.2 (83) | 75.4 (86) |

| 84.6 (143) | 68.4 (26) |

|

| IIA,

IIB, IIIA, IIIB | 8.9 (8) | 25.6 (30) |

| 10.8 (10) | 24.6 (28) |

| 15.4 (26) | 31.6 (12) |

|

| Histological

subtype, % (n) |

|

| 0.0050a |

|

| 0.0011a |

|

| 0.1858 |

|

Lepidicb | 63.3 (57) | 45.3 (53) |

| 65.6 (61) | 43.0 (49) |

| 55.0 (93) | 44.7 (17) |

|

|

Acinar | 21.1 (19) | 31.6 (37) |

| 16.1 (15) | 36.0 (41) |

| 26.6 (45) | 28.9 (11) |

|

|

Papillary | 3.3 (3) | 11.1 (13) |

| 5.4 (5) | 9.6 (11) |

| 5.9 (10) | 15.8 (6) |

|

|

Micropapillaryc | 0.0 (0) | 1.7 (2) |

| 0.0 (0) | 1.8 (2) |

| 0.6 (1) | 2.6 (1) |

|

|

Solid | 5.6 (5) | 9.4 (11) |

| 6.5 (6) | 8.8 (10) |

| 7.7 (13) | 7.9 (3) |

|

|

Mucinous | 6.7 (6) | 0.9 (1) |

| 6.5 (6) | 0.9 (1) |

| 4.1 (7) | 0.0 (0) |

|

| Cytological

subtype, % (n) |

|

| 0.0117a |

|

| 0.1114 |

|

| 0.1987 |

|

TRU | 87.8 (79) | 91.5 (107) |

| 88.2 (82) | 91.2 (104) |

| 88.2 (149) | 97.4 (37) |

|

|

Non-TRU/BSE | 10.0 (9) | 1.7 (2) |

| 8.6 (8) | 2.6 (3) |

| 6.5 (11) | 0.0 (0) |

|

|

Unclassifiable | 2.2 (2) | 6.8 (8) |

| 3.2 (3) | 6.1 (7) |

| 5.3 (9) | 2.6 (1) |

|

| EGFR, %

(n) |

|

| 0.0377a |

|

| 0.0498a |

|

| 0.0188a |

|

Mutated | 45.6 (41) | 59.0 (69) |

| 45.2 (42) | 59.6 (68) |

| 49.1 (83) | 71.1 (27) |

|

|

Wild-type | 54.4 (49) | 41.0 (48) | | 54.8 (51) | 40.4 (46) | | 50.9 (86) | 28.9 (11) |

|

Relationship between CRABP2, CEACAM5,

and MUC21 levels and highly malignant pathological factors

High CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21 expression levels

were significantly associated with lymphatic canal invasion

[CRABP2, 78 (66.7%) of 117 vs. 35 (38.9%) of 90; Pearson ×2 test,

P<0.0001; CEACAM5, 71 (62.3%) of 114 vs. 42 (45.2%) of 93,

P=0.0171; MUC21, 28 (73.7%) of 38 vs. 85 (50.3%) of 169, P=0.0112;

Table I]. Both CRABP2 and CEACAM5

were significantly associated with vascular invasion [47 (40.2%) of

117 vs. 16 (17.8%) of 90; P=0.0007 Pearson ×2 tests and 42 (36.8%)

of 114 vs. 21 (22.6%) of 93; P=0.0334, respectively (Table I)]. These results support the notion

that frequent lymphatic canal invasion is a biological basis for

the aggressiveness of mPAP elements (1,7–10).

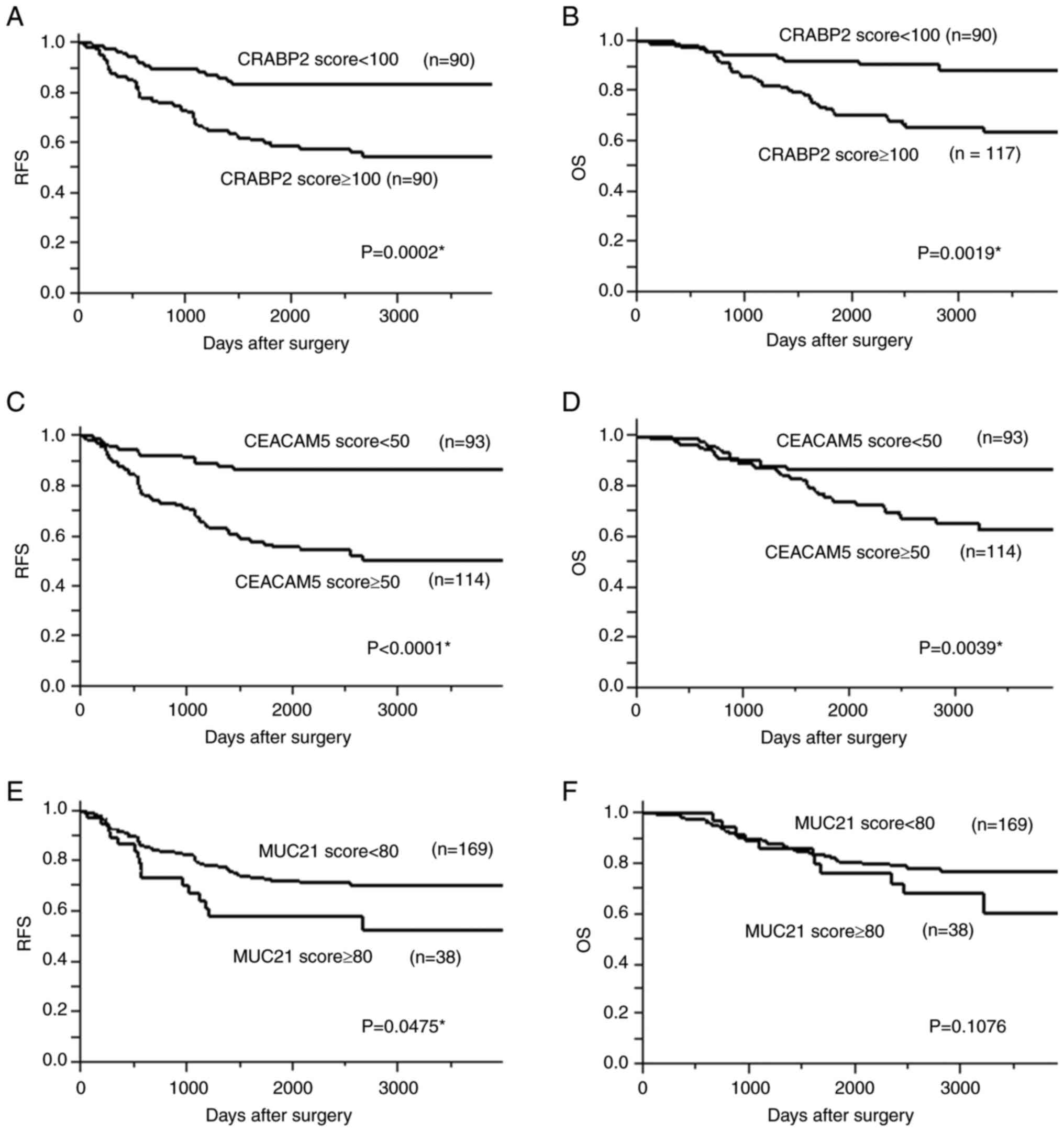

Relationships between CRABP2, CEACAM5,

and MUC21 levels and postoperative outcomes

Individuals with high CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21

expression had significantly worse 5-year RFS rates [CRABP2: 50.7%

vs. 73.8%, P=0.0002; CEACAM5: 55.6% vs. 86.5%, P<0.0001; MUC21:

5 58.3% vs. 72.2%, P=0.0475; (Fig.

6)]. Individuals with high CRABP2 and CEACAM5 expression had

significantly worse 5-year OS rates [72.3% vs. 92.0%, P=0.0019, and

75.1% vs. 86.9%, P=0.0039, respectively]. All P-values were

determined using log-rank tests.

In addition, multivariate analysis revealed CRABP2

(P=0.0325) and CEACAM5 expression (P=0.0002) as independent

predictors of disease recurrence and stage (Table II).

| Table II.Multivariate analysis performed using

the Cox proportional hazards model. |

Table II.

Multivariate analysis performed using

the Cox proportional hazards model.

|

| Recurrence-free

survival | Overall

survival |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| CRABP2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expression score (≤100 vs.

>100) | 1.894 | 1.05–3.59 | 0.0325a | 1.804 | 0.93–3.75 | 0.0842 |

| Sex

(female vs. male) | 1.100 | 0.61–2.01 | 0.7547 | 1.373 | 0.70–2.73 | 0.3588 |

| Smoking

status (never smoked vs. smoking) | 1.077 | 0.59–1.98 | 0.8107 | 1.116 | 0.56–2.25 | 0.7555 |

| Tumor

size (≤20 vs. >20 mm) | 1.193 | 0.66–2.13 | 0.5520 | 1.095 | 0.58–2.05 | 0.7769 |

|

Vascular invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.385 | 0.74–2.64 | 0.3149 | 1.222 | 0.58–2.62 | 0.5989 |

|

Lymphatic invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.128 | 0.57–2.23 | 0.7269 | 0.691 | 0.32–1.45 | 0.3315 |

| pStage

(I vs. II, III) | 4.859 | 2.65–8.88 | 0.0090a | 5.778 | 3.02–11.1 |

<0.0001a |

| CEACAM5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expression score (≤50 vs.

>50) | 3.045 | 1.67–5.95 | 0.0002a | 1.547 | 0.82–3.08 | 0.1849 |

| Sex

(female vs. male) | 1.023 | 0.56–1.87 | 0.9398 | 1.346 | 0.68–2.69 | 0.3928 |

| Smoking

status (never smoked vs. smoking) | 1.256 | 0.69–2.30 | 0.4578 | 1.191 | 0.60–2.42 | 0.6228 |

| Tumor

size (≤20 vs. >20 mm) | 1.308 | 0.72–2.35 | 0.3736 | 1.103 | 0.58–2.06 | 0.7605 |

|

Vascular invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.344 | 0.71–2.60 | 0.3697 | 1.192 | 0.56–2.58 | 0.8480 |

|

Lymphatic invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.191 | 0.60–2.35 | 0.6118 | 0.759 | 0.36–1.58 | 0.4643 |

| pStage

(I vs. II, III) | 4.720 | 2.55–8.70 |

<0.0001a | 5.795 | 2.99–11.3 |

<0.0001a |

| MUC21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expression score (≤80 vs.

>80) | 1.135 | 0.59–2.09 | 0.6971 | 1.100 | 0.52–2.22 | 0.7995 |

| Sex

(Female vs. Male) | 1.127 | 0.62–2.07 | 0.6974 | 1.383 | 0.70–2.77 | 0.3526 |

| Smoking

status (never smoked vs. smoking) | 1.163 | 0.62–2.19 | 0.6355 | 1.165 | 0.57–2.45 | 0.6809 |

| Tumor

size (≤20 vs. >20 mm) | 1.169 | 0.64–2.10 | 0.6047 | 1.099 | 0.57–2.07 | 0.7735 |

|

Vascular invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.401 | 0.74–2.70 | 0.3055 | 1.197 | 0.56–2.60 | 0.6426 |

|

Lymphatic invasion (absent vs.

present) | 1.245 | 0.63–2.47 | 0.5268 | 0.768 | 0.35–1.63 | 0.4925 |

| pStage

(I vs. II, III) | 5.222 | 2.75–9.85 |

<0.0001a | 6.475 | 3.28–12.8 |

<0.0001a |

A sub-analysis of stage I LUAD revealed that

individuals with high CRABP2 and CEACAM5 expression had

significantly worse 5-year RFS rates of 71.9% vs. 88.3% (P=0.009)

and 68.6% vs. 91.1% (P=0.002), respectively (Fig. S1). Moreover, individuals with high

CRABP2 and CEACAM5 expression had significantly worse 5-year OS

rates of 72.7% vs. 92.0% (P=0.033) and 87.2% vs. 92.6% (P=0.0345),

respectively. All P-values were determined using log-rank tests.

These results indicate that CRABP2 and CEACAM5 could serve as

excellent prognostic markers for recurrence and mortality in the

early stages of LUAD.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified three

molecules-CRABP2, CEACAM5, and MUC21-that play crucial roles in

promoting the lepidic-filigree-mPAP progression. These molecules

may be important in conferring aggressiveness to micropapillary, as

their high expression levels were associated with lymphatic canal

invasion, high recurrence rates, and poor 5-year survival rates.

However, the stage at which these molecules exert their effects

appears to vary. Specifically, CRABP2 is likely involved in the

early transition from lepidic to filigree, whereas CEACAM5 and

MUC21 are implicated in the later transition from filigree to mPAP

elements. No significant differences in CEACAM5 and

CRABP2 mRNA expression levels were observed between the

filigree and mPAP elements. However, an increase in the protein

expression of CEACAM5 and CRABP2 was observed between these

elements in the immunohistochemical analysis. This discrepancy may

be attributed to post-translational modifications.

To regulate the transcription of downstream genes,

CRABP2 transports retinoic acid to the nucleus, where it binds to

transcription factors. CRABP2 expression has been detected in lung

cancer (14), breast cancer

(15), and glioblastoma (16). Furthermore, CRABP2 enhances the

migration, invasion, and anoikis resistance of lung cancer cells

via the HuR and integrin β1/FAK/ERK signaling pathways and

promotes metastasis in vivo (14). Integrins play an important role in

cell adhesion, and CRABP2 overexpression activates the

integrin β1/FAK/ERK signaling pathway. These data suggest that

CRABP2 is involved in decreasing tumor cell adhesion and promoting

the morphological progression to filigree and mPAP patterns during

the early stages of LUAD development. CRABP2 is reportedly

significantly upregulated in LUAD with micropapillary elements

(17) and in small invasive

adenocarcinoma (18). Moreover,

high CRABP2 levels are correlated with lymph node metastases, poor

OS, and increased recurrence (18).

Collectively, these findings further support our findings.

The surface glycoprotein CEACAM5 is involved in cell

adhesion, intracellular signaling, and tumor progression. This

protein promotes cell proliferation and invasion via

p38/Smad2/3 signaling in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

(19). The induced overexpression

of CEA is associated with anoikis, a form of apoptosis caused by

detachment from the cell matrix, which enhances metastasis of

colorectal cancer (20). These data

implicate CEACAM5 in the morphological progression of the

micropapillary pattern (21,22).

MUC21 is a transmembrane mucin expressed in various

human neoplasms, including lung carcinomas (13,23).

It is associated with the aggressive behavior of neoplastic cells

(13). We have previously revealed

that MUC21, characterized by short glycosylated sugar chains, is

associated with highly malignant histological components, such as

micropapillary elements (13).

Moreover, mouse Muc21/epiglycanin disrupts cell-extracellular

matrix interactions and interferes with intercellular adhesions,

suggesting that Muc21/epiglycanin inhibits surface integrins and

intercellular adhesion molecules (24,25).

Miyoshi et al (26) reported

that the micropapillary element exhibits a loss of

integrin-mediated adhesion to the basal membrane, which may help

explain the mechanism by which MUC21 contributes to the

micropapillary morphology.

In the present study, we identified CRABP2 and

CEACAM5 as independent prognostic markers for LUAD recurrence.

Clinically, these molecules have various applications. First,

immunohistochemical examination of CRABP2 and CEACAM5 in

preoperative biopsied tissue or surgical resected tissue serves as

predictive markers to determine the suitability of neo-adjuvant or

adjuvant chemotherapy. Second, the plasma concentrations of these

proteins may be used as a screening assay for the early detection

of lung cancer (27,28). Increased plasma CRABP2 and CEACAM5

levels are correlated with decreased survival rates in patients

with LUAD (28,29). Third, targeting these molecules for

molecular therapy is becoming increasingly feasible. Specifically,

CEACAM5 has recently emerged as a promising target for

antibody-drug conjugate therapy of NSCLC. Tusamitamab ravtansine

(SAR408701), a humanized antibody-drug conjugate targeting CEACAM5,

is in clinical development for nonsquamous NSCLC with high CEACAM5

expression (30).

This study has some limitations. First, the quality

of RNA extracted from FFPE specimens may deteriorate due to

long-term storage or poor storage conditions (such as high

temperature and humidity). Japan Pathology Quality Assurance System

recommends using FFPE specimens within 2.5 to 3 years of

preparation to ensure reliable genetic testing. We use FFPE

specimens prepared within 3 years for the Visium Spatial Gene

Expression Profiling System. Additionally, these FFPE specimens

were stored at temperatures below 25°C. Second, the spatial

resolution of the Visium platform was insufficient to analyze the

microenvironment surrounding tissue elements (such as lepidic,

filigree, and mPAP elements) each in LUAD. However, in recent

years, the Xenium spatial transcriptomics platform, which offers

higher resolution than the Visium spatial transcriptomics platform,

has emerged. This technology will enable the analysis of the

microenvironment for different tissue elements of LUAD in the

future.

In conclusion, we investigated the potential

molecular basis of the lepidic-filigree-mPAP progression using the

Visium Spatial Gene Expression Solution and identified three

molecules that promote this progression. These molecules may have

clinical utility as prognostic markers and as potential targets of

molecular therapy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Japanese Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports and Science, Tokyo, Japan (grant nos.

21K15387 and 22K15410).

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequencing data generated in the present

study may be found in the National Center for Biotechnology

Information Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number

GSE 300676 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE300676.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MM and KO wrote the majority of the manuscript. TW

and HA collected patient information, compiled a clinical database

and conducted formal analysis. TW and HA made substantial

contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. TK was

responsible for the statistical analysis. MM and KO designed the

study and suggested the contents of the manuscript. MM, CK and KO

examined the tissue sections and made pathological diagnoses. MM

and CK contributed to funding acquisition. TS and HM cut tissue

sections and stained them with hematoxylin and eosin. DM and KF

performed Visium experiments, and analyzed and interpreted the

data. MM and KO confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committees of Kanagawa Prefectural Cardiovascular and Respiratory

Center (Yokohama, Japan; approval no. KCRC-17-0016; October 1,

2018). All patients provided written informed consent for the use

of their samples for research purposes. For prospective

observational studies, written informed consent has been obtained

from study participants. For retrospective observational studies,

existing specimens obtained for clinical purposes (pathological

specimens not additionally collected for research purposes) were

used. In principle, informed consent was sought for these

specimens; however, when obtaining informed consent was difficult,

opt-out consent was taken.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CEACAM5

|

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell

adhesion molecule 5

|

|

CRABP2

|

cellular retinoic acid binding protein

2

|

|

FFPE

|

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

mPAP

|

conventional/overt micropapillary

|

|

MUC21

|

mucin 21

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

RFS

|

recurrence-free survival

|

References

|

1

|

Makimoto Y, Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H,

Miyoshi T, Enatsu S, Shiraishi T, Iwasaki A, Shirakusa T and

Kikuchi M: Micropapillary pattern: A distinct pathological marker

to subclassify tumours with a significantly poor prognosis within

small peripheral lung adenocarcinoma (</=20 mm) with mixed

bronchioloalveolar and invasive subtypes (Noguchi's type C

tumours). Histopathology. 46:677–684. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Miyoshi T, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Nakagawa K,

Shirakusa T, Tsuchiya E and Ishikawa Y: Early-stage lung

adenocarcinomas with a micropapillary pattern, a distinct

pathologic marker for a significantly poor prognosis. Am J Surg

Pathol. 27:101–109. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chao L, Yi-Sheng H, Yu C, Li-Xu Y, Xin-Lan

L, Dong-Lan L, Jie C, Yi-Lon W and Hui LY: Relevance of EGFR

mutation with micropapillary pattern according to the novel

IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification and correlation

with prognosis in Chinese patients. Lung Cancer. 86:164–169. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Matsumura M, Okudela K, Kojima Y, Umeda S,

Tateishi Y, Sekine A, Arai H, Woo T, Tajiri M and Ohashi K: A

histopathological feature of EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas with

highly malignant potential-An implication of micropapillary

element. PLOS One. 11:e01667952016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Husain A, Farver C and Nicholson A:

Adenocarcinoma of the lung. WHO classification of tumours. Borczuk

A, Chan J, Cooper W, Dacic S, Kerr K, Lantuejoul S and Marx A: 5th

edition. IARC; Lyon: 2021

|

|

6

|

Fukutomi T, Hayashi Y, Emoto K, Kamiya K,

Kohno M and Sakamoto M: Low papillary structure in lepidic growth

component of lung adenocarcinoma: A unique histologic hallmark of

aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol. 44:1849–1858. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gracia Villacampa E, Larsson L, Mirzazadeh

R, Kvastad L, Andersson A, Mollbrink A, Kokaraki G, Monteil V,

Schultz N, Appelberg KS, et al: Genome-wide spatial expression

profiling in formalin-fixed tissues. Cell Genom. 1:1000652021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xie L, Kong H, Yu J, Sun M, Lu S, Zhang Y,

Hu J, Du F, Lian Q, Xin H, et al: Spatial transcriptomics reveals

heterogeneity of histological subtypes between lepidic and acinar

lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Med. 14:e15732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Takano Y, Suzuki J, Nomura K, Fujii G,

Zenkoh J, Kawai H, Kuze Y, Kashima Y, Nagasawa S, Nakamura Y, et

al: Spatially resolved gene expression profiling of tumor

microenvironment reveals key steps of lung adenocarcinoma

development. Nat Commun. 15:106372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sobue T, Yamamoto S, Hara M, Sasazuki S,

Sasaki S and Tsugane S: Cigarette smoking and subsequent risk of

lung cancer by histologic type in middle-aged Japanese men and

women: the JPHC study. Int J Cancer. 99:245–251. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Suzuki M, Shinozaki-Ushiku A, Yuhara S,

Nagano M, Sato M and Ushiku T: The prognostic impact of

extra-alveolar invasion in lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer.

205:1086122025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kawai H, Miura T, Kawamatsu N, Nakagawa T,

Shiba-Ishii A, Yoshimoto T, Amano Y, Kihara A, Sakuma Y, Fujita K,

et al: Expression patterns of HNF4a, tTF-1, and SMARCA4 in lung

adenocarcinomas: Impacts on clinicopathological and genetic

features. Virchows Archiv. 486:343–354. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Matsumura M, Okudela K, Nakashima Y,

Mitsui H, Denda-Nagai K, Suzuki T, Arai H, Umeda S, Tateishi Y,

Koike C, et al: Specific expression of MUC21 in micropapillary

elements of lung adenocarcinomas-Implications for the progression

of EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas. PLoS One. 14:e02152372019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu JI, Lin YP, Tseng CW, Chen HJ and Wang

LH: Crabp2 promotes metastasis of lung cancer cells via HuR and

integrin β1/FAK/ERK signaling. Sci Rep. 9:8452019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Feng X, Zhang M, Wang B, Zhou C, Mu Y, Li

J, Liu X, Wang Y, Song Z and Liu P: CRABP2 regulates invasion and

metastasis of breast cancer through hippo pathway dependent on ER

status. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:3612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu RZ, Li S, Garcia E, Glubrecht DD, Poon

HY, Easaw JC and Godbout R: Association between cytoplasmic CRABP2,

altered retinoic acid signaling, and poor prognosis in

glioblastoma. Glia. 64:963–976. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xu L, Su H, Zhao S, Si H, Xie H, Ren Y,

Gao J, Wang F, Xie X, Dai C, et al: Development of the semi-dry

dot-blot method for intraoperative detecting micropapillary

component in lung adenocarcinoma based on proteomics analysis. Br J

Cancer. 128:2116–2125. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dai T, Adachi J, Dai Y, Nakano N, Yamato

M, Kikuchi S, Usui S, Minami Y, Tomonaga T, Noguchi M, et al:

In-depth proteomics reveals the characteristic developmental

profiles of early lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor

receptor mutation. Cancer Med. 12:10755–10767. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang X, Han X, Zuo P, Zhang X and Xu H:

CEACAM5 stimulates the progression of non-small-cell lung cancer by

promoting cell proliferation and migration. J Int Med Res.

48:3000605209594782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li Q, Li Y, Li J, Ma Y, Dai W, Mo S, Xu Y,

Li X and Cai S: FBW7 suppresses metastasis of colorectal cancer by

inhibiting HIF1α/CEACAM5 functional axis. Int J Biol Sci.

14:726–735. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Süer H, Erus S, Cesur EE, Yavuz Ö,

Ağcaoğlu O, Bulutay P, Önder TT, Tanju S and Dilege Ş: Combination

of CEACAM5, EpCAM and CK19 gene expressions in mediastinal lymph

node micrometastasis is a prognostic factor for non-small cell lung

cancer. J Cardiothorac Surg. 18:1892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Odintsov I and Sholl LM: Prognostic and

predictive biomarkers in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Pathology.

56:192–204. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yoshimoto T, Matsubara D, Soda M, Ueno T,

Amano Y, Kihara A, Sakatani T, Nakano T, Shibano T, Endo S, et al:

Mucin 21 is a key molecule involved in the incohesive growth

pattern in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 110:3006–3011. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yi Y, Kamata-Sakurai M, Denda-Nagai K,

Itoh T, Okada K, Ishii-Schrade K, Iguchi A, Sugiura D and Irimura

T: Mucin 21/epiglycanin modulates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem.

285:21233–21240. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Denda-Nagai K, Ishii-Schrade KB, Tian Y,

Okada K and Irimura T: Immunohistochemistry of mucin. Glycoscience

protocols (GlycoPODv2). Nishihara S, Angata K, Aoki-Kinoshita KF

and Hirabayashi J: Japan Consortium for Glycobiology and

Glycotechnology; Saitama: pp. p212021, PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Miyoshi T, Shirakusa T, Ishikawa Y,

Iwasaki A, Shiraishi T, Makimoto Y, Iwasaki H and Nabeshima K:

Possible mechanism of metastasis in lung adenocarcinomas with a

micropapillary pattern. Pathol Int. 55:419–424. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Djureinovic D, Pontén V, Landelius P, Al

Sayegh S, Kappert K, Kamali-Moghaddam M, Micke P and Ståhle E:

Multiplex plasma protein profiling identifies novel markers to

discriminate patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. BMC Cancer.

19:7412019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lung Cancer Cohort Consortium (LC3), . The

blood proteome of imminent lung cancer diagnosis. Nat Commun.

14:30422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kim DJ, Kim WJ, Lim M, Hong Y, Lee SJ,

Hong SH, Heo J, Lee HY and Han SS: Plasma CRABP2 as a novel

biomarker in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Korean Med

Sci. 33:e1782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lefebvre AM, Adam J, Nicolazzi C, Larois

C, Attenot F, Falda-Buscaiot F, Dib C, Masson N, Ternès N, Bauchet

AL, et al: The search for therapeutic targets in lung cancer:

Preclinical and human studies of carcinoembryonic antigen-related

cell adhesion molecule 5 expression and its associated molecular

landscape. Lung Cancer. 184:1073562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|