Introduction

Human guanylate-binding protein 2 (hGBP2) and murine

(m)GBP2 were first isolated from human fibroblasts in 1982

(1) and macrophages in 1998

(2). GBP2 is a member of the

IFN-inducible GTPase family that serves notable roles in cellular

signaling. hGBP2 is reported to be highly expressed in various

immune cells, including monocytes, lymphocytes and natural killer

cells (3). Under basal conditions,

hGBP2 and mGBP2 are primarily distributed diffusely in the

cytoplasm and nucleus. However, upon stimulation by IFN-γ and in

the GTP-bound state, such as hGBP1 and hGBP5, it can translocate to

the Golgi apparatus (4,5). The genes encoding hGBP1-7 are located

on human chromosome 1, whilst the genes encoding mGBP1-11 are

located on mouse chromosome 3 (3),

where mGBP2 is mapped to the distal end and is putatively

associated with mGBP1 (2).

The inflammasome is a multi-protein complex that

functions to eliminate abnormal cells and amplify inflammation. It

is comprised of various sensor proteins, such as the NLR family

pyrin domain-containing 3 [NLRP3; which primarily recognizes

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced signals], absent in melanoma 2

(AIM2; which detects intracellular double-stranded DNA), adaptor

proteins, such as the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and caspase effector

proteins. It also senses pathogen-associated molecular patterns

(PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), thereby

triggering pyroptosis, a type of programmed cell death

characterized by gasdermin-D-mediated plasma membrane perforation

and release of inflammatory cytokines. hGBP2 activates inflammasome

assembly and pyroptosis primarily by binding and delivering LPS

into the cytoplasm (6).

Additionally, hGBP2 facilitates inflammasome assembly through

direct binding to ASC and cooperates with hGBP5 (7).

In the context of cancer, paclitaxel (PTX), which

has become an important chemotherapeutic agent since its discovery

in 1967, is a natural diterpenoid compound that can be isolated

from Taxus brevifolia. hGBP2 cooperates with PTX through the

MCL-1 apoptosis regulator, myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL-1)/Bcl-2

antagonist/killer 1 (Bak) pathway (8) to activate the vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) pathway, thereby promoting angiogenesis and

oxygen supply to tumor. Immunologically ‘cold’ tumors are

characterized by poor responses to immunotherapies (9) and host a tumor immunosuppressive

microenvironment (TIME) lacking infiltrating immune cells. Such

tumors typically exhibit rapid progression and poor prognosis

(10), posing a major challenge in

cancer immunotherapy. Notably, hGBP2 may offer a promising

therapeutic strategy for ‘cold’ tumors by activating a number of

immune checkpoints, such as programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and lymphocyte activating

3 (LAG3) (11), thereby remodeling

the TIME and inhibiting the activation of CD8+ T cells

and CD4+ T cells (12).

Structure and hydrolase function of

hGBP2

Structure of hGBP2

hGBP2 is a 67 kDa GTPase that is comprised of three

distinct domains (13). The

N-terminal region contains a large GTPase domain (LG; residues

1–309), followed by the middle domain (MD; residues 310–480) in the

central region and the α12/13 helical domain (HD; residues 480–580)

at the C-terminus. In its crystalline state, hGBP2 adopts a

bi-molecular asymmetric unit configuration.

The LG domain serves as the nucleotide-binding site

and is characterized by five conserved motifs involved in GTP

binding and hydrolysis (Table I)

(14). The G1/P-loop motif has a

GxxxxGKS/T sequence (15) that

encloses the β-phosphate of GTP. By contrast, the G2/SWITCH I motif

serves a critical role in magnesium ion binding, which is a key

feature for all GTPases, since it stabilizes the GTP molecule

through coordination bonds with the phosphate groups. The G3/SWITCH

II motif, with its conserved DTEG residue sequence, forms hydrogen

bonds with the phosphate, aiding in its release. The G4 motif

interacts specifically with the guanine base with its acidic Asp

residue in the RDF residue sequence, facilitating the binding of

GTP to the domain. The primary non-conserved region, located

between residue 240 and 280, corresponds to a flexible region

involved in membrane interactions and is situated within the G5

region. The G1-G5 motifs collectively constitute the

‘nucleotide-binding pocket’ for GTP (Table I).

| Table I.Key motifs (G1-G5) of the human

guanylate-binding protein 2 hydrolysis site. |

Table I.

Key motifs (G1-G5) of the human

guanylate-binding protein 2 hydrolysis site.

| Motif

designation | Sequence | Corresponding

residue numbers |

|---|

| G1/P-loop | GLYRTGKS | 45-52 |

| G2/SWITCH I | TVKSHT | 70-75 |

| G3/SWITCH II | DTEG | 97–100 |

| G4 | RDF | 181-183 |

| G5/Guanine cap |

WPAPKKYLAHLEQLKEEE | 236-255 |

The MD domain consists of 5 α-helices. The first

helix group is formed of the N-terminal halves of α7, α8 and α9,

where the second helix group is formed of the C-terminal half of

α9, α10 and α11. By contrast, the α12/α13 domain contains a

conserved CaaX sequence, where isoprenylation occurs, promoting the

localization of hGBP2 on the membrane as a hydrophobic group.

Another feature of α12/α13 domain is its interaction with LG

domain. The α12/α13 domain is mainly negatively charged, while the

LG domain mainly carries positive charge. This enables the two

domains to contact through electrostatic interactions (13,16),

where the α12/α13 domain is in a tightened state.

Hydrolase function of hGBP2

The hydrolase function of hGBP2 is essential for a

number of mechanisms and processes. The membrane localization of

hGBP2 requires homodimerization, which is dependent on the

transition state of GTP hydrolysis (17).

The hGBP2 hydrolysate, which contains >75% GDP

(18,19), yields only a small amount of GMP as

the final product (13,16), which is obtained by the hydrolysis

of GTP instead of GDP. This distinct characteristic, differing from

hGBP1, is primarily attributed to the LG domain of hGBP2 rather

than changes in the MD or HD domains. Specifically, this is due to

differences in the adjustment of the active site in the LG domain

of hGBP2 following the first hydrolysis event. In terms of

tetramerization, hGBP2, unlike hGBP1 but like mGBP2 (18), can extensively tetramerize, although

the tetramerization of hGBP2 does not contribute to the formation

of GMP (20,21).

When hGBP2 binds GTP, GTP enters the nucleotide

binding pocket formed by the G1-G5 motif, where hGBP2 undergoes

homodimerization at the same time with the participation of LG and

MD domains (22,23). The LG domain of hGBP2 is dimerized

only 50% of the time in the presence of GTP, suggesting that the

C-terminal domain of hGBP2 also participates in dimerization by

providing a dimerization interface or otherwise stabilizing hGBP2

dimers in the GTP state (16). In

addition, residue T75 in the G2/SWITCH motif and S52 in the G1

motif are involved in Mg2+ coordination (13), implying that Mg2+ may

enter the nucleotide binding pocket and bind to the phosphate group

and surrounding amino acid residues at this stage, which are

necessary for hGBP2 activity. It has previously been reported that

Mg2+ is necessary for the activation of hGBP2 at Ph 8.0,

but not pH 6.0 (16), which

suggests that Mg2+ and H3O+ may

have a functional substitution relationship. However, this

interaction requires further validation.

In the hGBP2-GDP conformation following phosphate

group dissociation, the N-O bond of the G1/P-loop motif interacts

with the β-phosphate. Concurrently, residue S52 forms N-O bonds

with both the α- and β-phosphates, facilitating nucleotide

positioning and binding (24,25).

The Y47 side chain undergoes movement and participates in dimer

interface formation, whilst the displacement of Y47 and R48 in the

G1 motif induces notable movement of the G2 motif, with some Cα

atoms shifting >10 Å (26). The

G4/RD motif interacts with the guanine moiety through hydrogen

bonding. W238 in the G5 motif undergoes allosteric rearrangement

and interacts with W238 from another hGBP2 molecule (13). Consequently, the guanine base and

ribose are enclosed within the space formed by the G1, G4 and G5

motifs. At the opposite end of the GDP, the diphosphate group is

tightly positioned within the pocket formed by the G1/P-loop,

G2/SWITCH I and G3/SWITCH II motifs. The β-phosphate further

coordinates with the conserved residues K51, S52 and E99. When the

E99-K51 interaction is absent, SWITCH I remains open. However, when

these residues engage through hydrogen bonding, SWITCH I closes,

simultaneously positioning T75 in the G2 motif for optimal

interaction with Mg2+ (16).

Regulation of hGBP2 and mGBP2

Structural foundation of hGBP2 and

mGbp2 genes

The hGBP2 gene, as an IFN-stimulated gene

(ISG), contains a promoter region featuring two transcription

factor binding sequences, namely the IFN-stimulated response

element (ISRE), located at +42 (27) and the γ-activated sequence (GAS)

(27,28), located at +53 and at −532 (27). Notably, GAS exhibits binding

affinity for all STAT factors except for STAT2. Both sequences can

independently respond to IFN signaling, whilst their combined

presence results in enhanced transcriptional activity (29). By contrast, the mGbp2 gene is

also an ISG, which contains one ISRE, located at −2 (27) and two GASs, located at −487 and −735

(27). However, Ramsauer et

al (28) previously reported

that the mGbpP2 gene has two ISREs, located at −30 and −440

and one GAS located at −530 (28).

Molecular regulatory mechanisms

IFN-independent hGBP2 and mGbp2 gene expression

under normal conditions

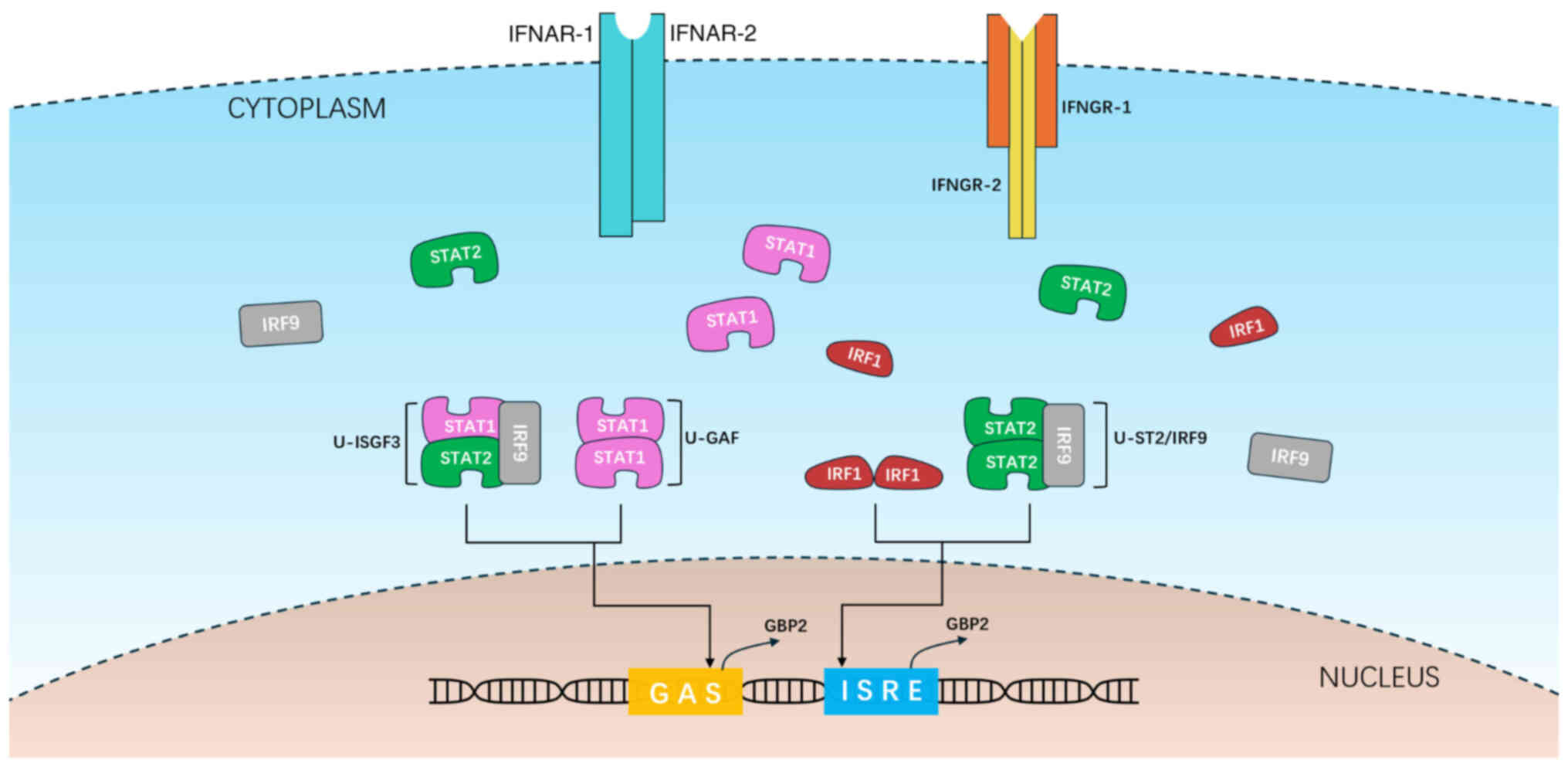

STAT1, STAT2 and IFN-regulatory factor (IRF) 9 can

form four types of oligomers. They are STAT1-STAT1 (binding to GAS,

referred to as U-STAT1), STAT1-STAT2-IRF9 (binding to GAS, referred

to as U-ISGF3), STAT2-STAT2-IRF9 (binding to ISRE, referred to as

U-ST2) and IRF1-IRF1 (binding to ISRE) (29). These oligomers subsequently localize

to hGBP2 or mGbp2 genes and activate their

transcription (Fig. 1). In mice,

the IRF1 dimer has been demonstrated to directly bind to the

transcription complex containing RNA polymerase II to activate

mGbp2 gene transcription (28), whilst STAT1 dimers not only bind to

GAS on the hGBP2 gene promoter but also promote the

acetylation of histone 4 in the hGBP2 gene, thereby

providing active chromatin. Additionally, previous studies have

shown that p53 can form a complex with IRF1 to upregulate hGBP2

expression (30,31).

Highly activated phase under

stimulation by IFN-I, IFN-II and IRF1

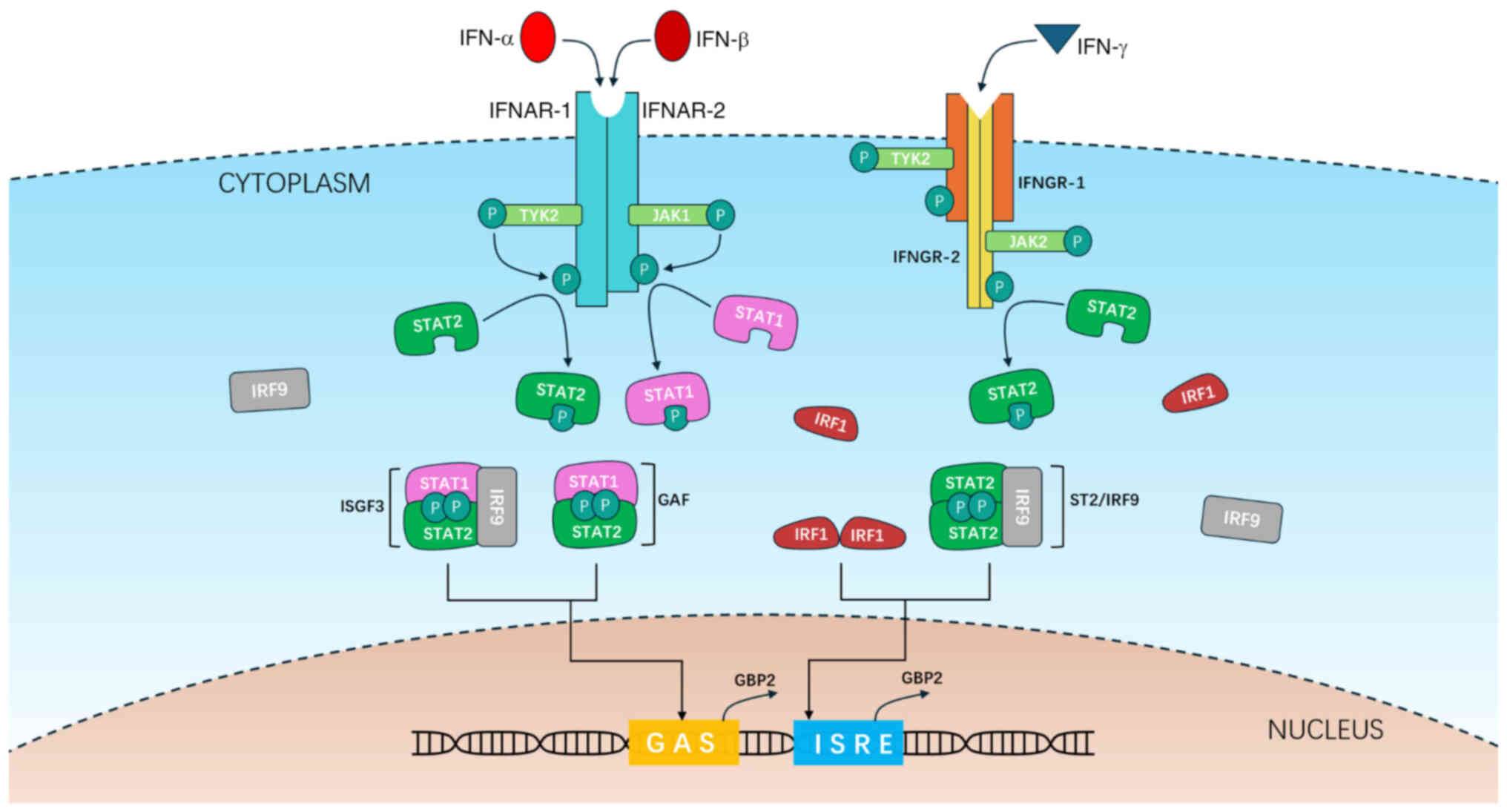

Upon pathogen invasion or intracellular

abnormalities, the corresponding PAMPs or DAMPs are recognized by a

series of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This type of

recognition triggers the phosphorylation and activation of IRFs,

thereby promoting the expression of IFN-I and IFN-II (the former

mainly includes subtypes IFN-α and IFN-β) through the classical

secretory pathway. These IFNs are secreted extracellularly and bind

to their corresponding respective receptors. Mitochondrial outer

membrane permeabilization (MOMP) under radiation conditions and

apoptosis can lead to the release of mitochondrial double-stranded

(ds)DNA, which activates the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of

IFN genes pathway, subsequently inducing IFN-β and upregulating

mGBP2 expression (32).

IFN-I can bind to the ubiquitously expressed IFN-α/β

receptor (consisting of the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits), leading to

the dimerization of the receptor subunits. This dimerization,

through juxtaposition and trans-phosphorylation, enhances the

kinase activity of Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and tyrosine kinase (TYK)

2. Subsequently, JAK1 and TYK2 phosphorylate tyrosine residues on

IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, which serve as binding sites for STAT1 and STAT2

(33). Phosphorylation of STAT1 at

Tyr701 and STAT2 at Tyr690 then occurs. By contrast, IFN-II,

specifically IFN-γ, interacts with a tetrameric receptor complex

composed of two IFNGR1 subunits and two IFNGR2 subunits. This

receptor is associated with JAK1 and JAK2 kinases, which

exclusively phosphorylate the STAT1 protein.

Similar to the pathway under normal conditions,

phosphorylated (p-)STAT1, p-STAT2 and IRF1 can form four types of

oligomers: p-STAT1-p-STAT1 (also known as γ-IFN activation factor,

binds to GAS), p-STAT1-p-STAT2-IRF9 (binds GAS), pSTAT1-pSTAT2-IRF9

(also known as IFN-stimulated gene factor, binds to ISRE) and

IRF1-IRF1 (binds ISRE). These oligomers subsequently localize to

the hGBP2 or mGbp2 gene and activate its

transcription through a similar mechanism (Fig. 2), exhibiting higher activity

compared with their non-phosphorylated counterparts.

Function of hGBP2 and mGBP2 in

inflammation

Activation of the inflammasome pathway

by hGBP2 and mGBP2

The inflammasome pathway can be divided into two

types, namely the canonical pathway and the non-canonical pathway.

Their objective is to induce pyroptosis, which is mediated by the

formation of plasma membrane pores through gasdermin-D. This leads

to membrane rupture and alerting other cells, with the release of

cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 through the gasdermin-D-formed membrane

pores. hGBP2 and mGBP2 primarily serve supporting roles in

inflammasome assembly.

In the canonical pathway, activation is primarily

mediated by PRRs, such as nucleotide-binding oligomerization

domain-like receptors, such as NLRP3, or AIM2-like receptors,

including AIM. PAMPs or DAMPs are recognized by PRRs, such as NLRP3

or AIM2. During this process, mGBP2 can facilitate the release of

dsDNA by lysing pathogen-containing vacuoles or pathogens, enabling

AIM2 recognition (7,34,35).

Upon activation, NLRP3 or AIM2 interacts with the adaptor protein

ASC through their pyrin domains (36). In this step, mGBP2 and mGBP5 can

form a heterocomplex, where mGBP2 binds ASC and mGBP5 binds NLRP3.

This mGBP2-mGBP5 complex brings NLRP3 and ASC together, thereby

promoting the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome (7). ASC in turn recruits caspase-1 through

its caspase recruitment domain, forming the inflammasome.

Subsequently, caspase-1 within the inflammasome cleaves

gasdermin-D, releasing its N-terminal fragment to form plasma

membrane pores and induce pyroptosis. Caspase-1 also processes

pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, which are then

released through the membrane pores to alert neighboring cells

(7).

In the non-canonical pathway, activation in humans

is primarily mediated by hGBPs through PRRs while in mice, it is

mediated by caspase-11 with the assistance of mGBP2. In humans,

when bacteria enter cells, hGBP1 binds bacterial LPS and recruits

hGBP2, hGBP3 and hGBP4 to the surface of bacteria, especially

gram-negative bacteria, forming a coating (6,37).

hGBP2 and hGBP4 expose the lipid moiety of LPS, recruiting

caspase-4 to the bacterial surface for LPS binding, while hGBP3

regulates caspase-4 activation (6,37).

Activated caspase-4 then cleaves pro-IL-1β, pro-IL-18 and

gasdermin-D, leading to pyroptosis and cytokine release.

In mice, caspase-11 directly recognizes the

mGBP2-LPS complex, oligomerizes and activates, gaining the ability

to cleave gasdermin-D and induce pyroptosis (38). Additionally, the formation of plasma

membrane pores causes potassium ion efflux due to the intracellular

potassium gradient, further promoting NLRP3 inflammasome assembly

and creating a positive-feedback amplification loop (39). In this process, mGBP2 assists

caspase-11 in LPS recognition. A previous study has reported that

mGBP2 can interact with gasdermin-D and mGBP3, potentially serving

as a novel component of this pathway, although the precise

mechanisms remain unclear and require further investigation

(7).

The severe consequences of pyroptosis, such as

further inflammation cascade caused by the release of IL-18 and

IL-1β (40), may explain the need

for the continuity and regulation of the GBP2/caspase pathway. This

type of regulation allows for the existence of multiple regulatory

checkpoints before caspase activation, increasing the difficulty of

activation and preventing unnecessary triggering (6).

Role of hGBP2 and mGBP2 in

inflammatory diseases

The expression of hGBP2 is increased in the kidney

tissues of patients with lupus nephritis, particularly in the

glomeruli and renal tubulointerstitium (41). In diabetic nephropathy, macrophages

at the injury site are predominantly of the M1 subtype, where hGBP2

can promote the polarization of macrophages toward the

pro-inflammatory M1 subtype through the Notch 1 pathway. Through

the hGBP2-mediated pathway, macrophages can be induced into the M1

phenotype by LPS or IFN-γ (42).

In allergic rhinitis (AR), mGBP2 can alleviate

oxidative stress and abnormal lipid metabolism by inhibiting the

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) pathway. It can also inhibit

mitochondrial fission whilst maintaining mitochondrial fusion to

mitigate oxidative stress-induced damage to cells (43). A previous study has demonstrated

that the overexpression of mGBP2 can notably reduce inflammatory

cell infiltration into the nasal mucosa and markedly decrease the

levels of various factors, such as total cholesterol, low-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol, TNF-α, IL-5, IFN-γ and trimethylamine

N-oxide, in AR mouse models whilst increasing high-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol levels (44). However, the underlying mechanisms

require further investigation.

LPS-induced macrophages-derived exosomes (L-Exo) can

be transported from macrophages to lung epithelial cells, resulting

in damage to the alveolar epithelial tissue. The mGBP2 content in

L-Exo is higher compared with that in control Exo (45), leading to the hypothesis that the

mGBP2 contained in L-Exo can trigger pyroptosis in the lung

epithelial tissue, thereby causing injury. This may represent a

potential therapeutic approach for sepsis-associated acute lung

injury (46). In depression-like

behaviors induced by neuroinflammation, reducing the expression of

mGBP2 may also alleviate symptoms (47).

Role of hGBP2 and mGBP2 in oncogenesis and

cancer

hGBP2 and mGBP2 regulate cancer

progression through multiple signaling pathways

Previous studies have demonstrated that in

glioblastoma (GBM) and low-grade glioma cells, hGBP2 can directly

interact with kinesin family member 22 (KIF22) to

post-transcriptionally regulate and elevate its levels, thereby

enhancing KIF22-mediated EGFR internalization and signaling

(Table II) (48–63).

This in turn fosters cell proliferation (64). Unc-51 like autophagy activating

kinase 1 (ULK1) is another critical regulator of autophagy

(65), phosphorylating and inducing

autophagy under low-nutrient conditions. hGBP2 can activate the

ULK1 complex by suppressing PI3K/Akt/mTORC1 pathway (66), thereby enhancing cellular autophagy

(66). Notably, the outcomes of

this function may vary, where it may exert tumor-suppressive

effects during early-stage cancer but potentially promote cancer

progression at advanced stages (67).

| Table II.GBP2 expression level across

different cancer types and corresponding mechanisms. |

Table II.

GBP2 expression level across

different cancer types and corresponding mechanisms.

| Tumor type | Cells or databases

involved | Species | GBP2 expression

level | Mechanisms | (Refs.) |

|---|

| GBM | Glioblastoma cell

lines, U87, U251, SNB19, GSC11 and G91; database, TCGA | Human | Upregulated | Expression of

various carcinogenesis-related genes in GBM, particularly in

mesenchymal subtype, including fibronectin 1, MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-14,

urokinase, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine, TGFB1,

macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1, CD44, IL-8, monocyte

chemoattractant protein 1 and IL6, are elevated with hGBP2

involvement. Furthermore, cell proliferation is accelerated, the

block of G0/G1 phase of cell cycle is

prevented and apoptosis is decreased, due to hGBP2-activated

kinesin family member 22/EGFR signaling pathway | (48–51) |

| BC, particularly

triple-negative BC | Primary BC cells

isolated from tumor tissues from patients with BC and normal breast

tissue | Human | Downregulated | The methylation of

hGBP2 gene promoter decreases the levels of hGBP2,

inhibiting the promotion of the immune response of CD8+

T cells, thus facilitating the development of BC | (52–54) |

| SKCM | Human melanoma cell

lines, A2058, A375; mouse melanoma cell lines, B16 and B16F10;

human epidermal cell line, NHEK | Human and

mouse | Downregulated | It has been

revealed that overexpressing hGBP2 can upregulate E-cadherin and

downregulate N-cadherin and vimentin, inhibiting the EMT, invasion

and proliferation of SKCM. While whether hGBP2 downregulation,

which occurs in SKCM cells, can facilitate EMT remains

unstudied.hGBP2 also markedly downregulates the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway and related proteins, including transcription

factor 4, c-Myc and cyclin D1, thus inhibiting cell proliferation,

migration, invasion and promoting cell apoptosis. The mechanisms of

mGBP2 in SKCM is unstudied | (51,55) |

| ccRCC | Primary ccRCC cells

isolated from patient tumor tissue and normal kidney tissue;

monocyte cell line, THP-1; common RCC cell lines, 786-O, 769-P,

CAKI-1, A498 and ACHN; renal tubular epithelium cell line, HK-2;

databases, Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium and

TCGA | Human | Upregulated | hGBP2 activates the

polarization of M0 macrophages toward the M2 macrophages through

JAK/STAT3-dependent upregulation on IL-18 secretion.

Simultaneously, M2 macrophages can induce the expression of GBP2 in

tumor cells by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, which in turn activates

the expression of hGBP2, forming a loop. hGBP2 can also enhance the

levels of regulatory T cells and exhausted T cells, facilitating

ccRCC tumor immune evasion and proliferation | (51,56,57) |

| PAAD | Databases, TCGA and

GEO; primary PAAD cells isolated from tumor tissue from patients

with PAAD and adjacent normal tissue | Human | Upregulated | hGBP2 levels are

markedly elevated in active CD4 memory T cells, resting dendritic

cells and M1 macrophages, indicating that these three types of

cells can possibly induce the expression of hGBP2. Subsequently,

hGBP2 can further regulate the TIME | (11,51) |

| Thyroid

carcinoma | Database, TCGA | Human | Upregulated | Remains

unstudied | (51) |

| Uveal melanoma | Database, TCGA | Human | Upregulated | Remains

unstudied | (51) |

| Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Databases, TCGA and

GEO | Human | Upregulated | hGBP2 can induce

tumor cell infiltration, especially by upregulating macrophages and

downregulating Th17 and neutrophils in the TIME | (51,58) |

| ESCC | Human ESCC cell

lines, TE-1, TE-7, TE-10 and TE-13 | Human | Upregulated | hGBP2 is involved

in a p53/IRF-1/hGBP2 pathway and is thus overexpressed in ESCC.

Downstream mechanisms remain unstudied | (30) |

| CRC | Databases: GEO,

UCSC Xena Browser, TCGA; human MSS CRC cell lines, HT29 and SW480;

murine MSS CRC cell line, CT26 | Human and

mouse | The level of hGBP2

varies: Upregulated in MSS CRC of IC and dMMR/MSI CRC;

downregulated in pMMR/MSS CRC of non-IC | hGBP2 can activate

STAT1 by competing with SHP1, which inhibits the phosphorylation

and activation of STAT1, for binding to STAT1 | (59,60) |

| Gastric cancer | Databases: GEO,

TIDE, TCGA, UCSC Xena Browser, KEGG | Human | Upregulated | Remains

unstudied | (61) |

| HNSCC | Databases,

ONCOMINE, TCGA, HPA | Human | Stably upregulated

across different stages of HNSCC | Remains

unstudied | (31) |

| OC | Human cervical

cancer cell line, HeLa; murine breast cancer cell line, 4T1; murine

macrophage cell line, RAW264.7; murine preadipocyte cell line,

3T3-L1; murine ovarian cancer cell line, ID8 | Human and

mouse | Downregulated | mGBP2/Pin1/NF-κB

pathway, which is possibly inhibited in OC, induces the

polarization of M0 to M1, thus the anticancer macrophage subtype M1

is at low levels in OC | (62) |

| Prostate

cancer | Databases, KEGG,

GEO, TCGA | Human | Upregulated | Remains

unstudied | (63) |

hGBP2 can induce the assembly of inflammasomes,

leading to a positive feedback loop of inflammatory responses. This

forms the hGBP2/STAT3/fibronectin (FN1) pathway (49,53),

where hGBP2 induces FN1, which is an extracellular glycoprotein

involved in cell migration (68),

on both transcriptional and translational levels to enhance

glioblastoma migration and invasion without influencing

proliferation in vitro (49). In addition, STAT3 contributes to

maintaining the mesenchymal subtype of GBM (50) and is indispensable for hGBP2-induced

FN1 elevation (49). FN1 can also

promote MMP-9 secretion in a focal adhesion kinase (FAK)- and

Ras-dependent manner (69) or

through the FN1/MMP-2/MMP-9 pathway (70). However, hGBP2 can induce FN1 in

vivo but lacks this capability in vitro (49). Furthermore, MMP-9 is an inducer of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (71). Thus, hGBP2 should activate, rather

than inhibit, MMP-9 through the STAT3/FN1/FAK or STAT3/FN1/MMP-2

signaling pathways. However, the regulatory effect of hGBP2 on

migration has not been experimentally demonstrated.

Bak is a member of the Bcl-2 family that is crucial

for the activation of apoptosis. It promotes MOMP, thereby

triggering the apoptotic process (72). hGBP2 acts as a dual stimulator of

Bak. It can not only release Bak but can also promote its

expression (8). The LG domain of

hGBP2 specifically binds to the BH3 domain of Mcl-1, a member of

the Bcl-2 family, thereby preventing the interaction between Bak

and Mcl-1. This then releases Bak, which oligomerizes to induce

MOMP, ultimately promoting apoptosis (8). Simultaneously, hGBP2 upregulates the

expression of Bak through its inhibitory effect on the PI3K/Akt

pathway (8). In summary, hGBP2 can

promote MOMP by activating Bak and enhancing its expression,

thereby facilitating apoptosis. PTX, as an anticancer drug,

occupies the upstream position in the hGBP2/Mcl-1/Bak pathway.

Through this pathway, hGBP2 enhances cellular sensitivity to PTX

(8,66). Notably, hGBP2 upregulation is a

common feature of PTX treatment and other chemotherapeutic agents

for hematologic malignancies (such as doxorubicin, cytarabine,

vincristine, etoposide and IFN-γ). However, among these

antineoplastic agents, only PTX possesses the unique ability to

elevate Bak levels (8).

In breast cancer (BC) cells, hGBP2 has been

demonstrated to directly interact with dynamin-related protein 1

(Drp1) in a K51-dependent manner, preventing its translocation from

the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. This interaction inhibits

Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission and elongation, thereby

blocking mitochondrial division and cell metastasis in cancer cells

(73). Notably, the activity of

hGBP2 binding to Drp1 is influenced by all three major structural

domains of hGBP2, where it is possible that hGBP2 and Drp1 bind to

each other to form hetero-oligomers, although further

investigations are required (73).

hGBP2 also exerts its anticancer effects by inhibiting the

Wnt/β-catenin/EMT pathway (55,71,74)

and cancer cell metastasis and invasion, which has been

demonstrated in cancers such as skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) and

colon cancer, but the specific molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

PTX primarily inhibits tumor metastasis and progression by blocking

angiogenesis in tumor tissues, whilst hGBP2 enhances the

sensitivity of colon cancer cells to PTX by inhibiting the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway (75,76). Additionally, a previous study has

indicated that inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in BC and

triple-negative BC (TNBC) can promote ferroptosis in BC cells and

suppress cell cycle and growth regulatory proteins, such as cyclin

D1 and c-Myc. Therefore, it can be speculated that this may be a

potential function of hGBP2, warranting further investigation.

In mouse dendritic cells, mGBP2 has been reported to

interact with the Akt-p110 complex, inhibiting the phosphorylation

and activation of Akt (77,78). This in turn prevents the

phosphorylation of TSC complex subunit 2, disrupting its ability to

form a complex with tuberous sclerosis 1 that inhibits mTORC1

(77–80). VEGF promotes endothelial cell

proliferation and migration by binding to VEGFRs on endothelial

cells, thereby stimulating angiogenesis. Under basal conditions,

the HIF-1α subunit is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylases and

recognized by the von Hippel-Lindau protein complex, leading to its

ubiquitination and degradation. Under hypoxic conditions, however,

the HIF-1α subunit is stabilized, where it translocates to the

nucleus and dimerizes with the HIF-1β subunit to form the HIF-1

transcription factor, which then translocates to the nucleus and

binds to hypoxia-response element in the promoter of VEGF gene

(81,82), regulating VEGF transcription

(43). In oxygen-induced

retinopathy mice model, mGBP2 has been shown to inhibit the

HIF-1α/VEGF pathway by suppressing mTORC1 (78), thereby attenuating angiogenesis.

This reduces blood supply to cancer lesions, maintaining hypoxic

conditions and potentially curbing cancer progression.

mGBP2 can activate MMP-9 through distinct pathways,

thereby influencing collagen degradation near the basement membrane

(33), extracellular matrix

remodeling, angiogenesis in cancer lesions and cancer cell invasion

and metastasis (77). Previous

studies in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts have shown that mGBP2 can inhibit

Rac, disrupting its regulation of the cytoskeleton. This inhibition

suppresses the TNF-α-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway,

thereby reducing NF-κB-induced MMP-9 transcription (83). mGBP2 has been demonstrated in NIH

3T3 fibroblasts to directly interact with the p65 (RelA) protein in

the NF-κB pathway, preventing its binding to the MMP-9 promoter and

subsequently lowering MMP-9 expression (83). In ovarian cancer, mGBP2 promotes the

recruitment of the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase

NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1) protein, which activates the NF-κB

pathway (62). Based on this, it

can be hypothesized that mGBP2 may upregulate MMP-9 expression

through the Pin1/NF-κB and Rac/NF-κB pathways, although further

experimental validations are required.

hGBP2 and mGBP2 modulate cancer

progression by regulating the TIME

hGBP2 exerts a dual influence on the TIME. It can

promote immune activation, transforming the TIME into a ‘hot’

state, thereby addressing the immunologically ‘cold’ tumors, such

as TNBC and proficient mismatch repair/microsatellite stable

colorectal cancer (CRC) of the immune class (59). Simultaneously, it can also reduce

immune cell infiltration through certain mechanisms, enhancing

tumor immune evasion. Additionally, the expression of immunotherapy

biomarkers is positively associated with hGBP2 expression (61). In CRC, hGBP2 expression is

positively associated with CD8+ T cell infiltration,

CD8, PD-L1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9, CXCL10, CXCL11,

CXCL13, HLA-I expression, antigen processing and presentation

machinery and a variety of antitumor immunity steps, including the

release of cancer cell antigens, cancer antigen presentation,

priming and activation and trafficking of immune cells to tumors

(59). By contrast, it is

negatively associated with the cell count of cytokeratin (59). However, specific mechanisms of the

regulation of hGBP2 in CRC require further study.

In gastric cancer, hGBP2 is reported to be

positively associated with an inflamed TIME, immunophenoscore

(IPS), abundance of PD-1+ cells and the expression of

immunotherapy biomarkers, such as PD-L1, PD-L2, IFN-γ, CD8A,

secreted and transmembrane protein 1 and IFN-induced transmembrane

protein 3 (61). In GBM, it has

been demonstrated that urokinase, secreted protein acidic and rich

in cysteine, TGFB1, FN1 and colony-stimulating factor 1 are induced

by elevated hGBP2 expression (49).

In SKCM, previous studies have demonstrated that hGBP2 expression

is positively associated with the infiltration of B cells,

CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages,

neutrophils and dendritic cells (11,12,57,61),

This may serve a role in therapies that block PD-1/PD-L1

interactions to prevent tumor immune evasion, since CD8+

T cells are the primary effector cells in tumor killing (84). In BC, hGBP2 is positively associated

with T cell infiltration levels and can serve as a marker for T

cell infiltration (53). In clear

cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), hGBP2 promotes the infiltration

of CD8+ T cells, regulator T cells and both M1 and M2

macrophages (57).

From the perspective of reducing immune infiltration

and promoting tumor immune evasion, hGBP2 can exert oncogenic

effects by increasing the phosphorylation of STAT2 and STAT3,

modulating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and reducing tumor immune

infiltration (51). hGBP2 can also

induce immune checkpoints, such as PD-1/PD-L1, cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), T cell immunoreceptor

with Ig and ITIM domains, LAG3, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 and

V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA) (11), which are inhibitory immune

checkpoints. Additionally, hGBP2 can promote PD-L1 expression on

the transcriptional level by binding to and phosphorylating STAT1,

thereby reducing tumor immune infiltration and facilitating immune

evasion (85). hGBP2 can also

induce PD-L2; however, the relevant mechanisms remain unstudied

(61). Based on these functions,

hGBP2 will likely be a crucial target for restoring the TIME for

the treatment of immunologically ‘cold’ tumors, such as TNBC.

mGBP2 has been found to upregulate the secretion of

IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α (77).

Furthermore, mGBP2 promotes the maturation of dendritic cells and

enhances their antigen-presenting capacity, thereby boosting T cell

activation (77). mGBP2 also

promotes the polarization of macrophages into M1 and M2 subtypes by

promoting STAT3 pathway and by activating the NF-κB signaling

pathway (62), while hGBP2 promotes

polarization by stimulating the secretion of IL-18 (56). M2 macrophages, in turn, can enhance

the migration and invasion of tumor cells by secreting IL-10 and

TGF-β, which upregulate the hGBP2/STAT3 and ERK axes (part of the

MAPK signaling pathway) as demonstrated in ccRCC (56).

Notably, a number of downstream factors promoted by

hGBP2 can exhibit both pro-tumor and antitumor effects. CD80 in

pancreatic adenocarcinoma can bind to either CD28 (activates T

cells) or CTLA-4 (inhibits T cells), thereby bidirectionally

modulating immune responses (11).

Notably, hGBP2 is reported to promote the polarization of M0 to M2

in ccRCC by activating the secretion of IL-18 (56) and to M1 in ovarian cancer (62) and in diabetic nephropathy by

activating the Notch 1 signaling pathway (42). By contrast, mGBP2 has only been

reported to promote the polarization of M0 to M1 under the

activation of the PLGA-CpG@ID8-M nano vaccine (62). The underlying mechanisms of these

outcomes and whether mGBP2 can also promote the polarization of M0

to M2 require further investigation.

Regulation of hGBP2 in cancer

In primary CRC, hGBP2 has been found to exhibit a

high mutation rate alongside genes such as G protein subunit β1 and

GATA zinc finger domain containing 2A. However, only hGBP2 showed

an even higher mutation rate in CRC with liver metastasis (60). Additionally, in CRC with liver

metastasis, the hGBP2 gene undergoes methylation at four

specific sites (m1A, m5C, m6A and m7G) (60). Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor α, an anticancer factor, can inhibit hGBP2 expression

(58). In BC (52) and SKCM (12), the methylation level of hGBP2

increases, leading to a decrease in hGBP2 expression.

Future directions

Prior reviews on GBP2 have predominantly emphasized

their roles in host defense against bacterial and viral pathogens

(6,86,87),

with limited attention to the regulatory mechanisms of GBP2

expression or its functions in cancer and oncogenesis. Furthermore,

species-specific distinctions-particularly the differences between

hGBP2 and mGBP2-have been overlooked (86,87).

This review bridges these gaps by providing a comprehensive

analysis of the regulation of GBP2 expression and by systematically

comparing hGBP2 and mGBP2 functions in oncogenesis. Whether a

potential functional substitution relationship between

Mg2+ and H3O+ during hGBP2

activation exists and its possible mechanisms could offer further

insight into the hydrolysis of hGBP2, and requires further

investigation. Although hGBP2 can form tetramers extensively, this

tetramerization cannot facilitate the hydrolysis from GTP to GMP,

rendering the physiological relevance of its tetramerization

unknown. Moreover, while the context-dependent dual role of hGBP2

in cancer and oncogenesis has been extensively documented, the

underlying mechanisms have not yet been systematically elucidated.

For instance, although hGBP2 drives M0-to-M1 polarization via the

Notch1 pathway in diabetic nephropathy, it mediates an M0-to-M2

polarization in ccRCC; the determinants of these opposing outcomes

warrant further investigation.

Clinically, agonistic monoclonal antibodies which

promote hGBP2 oligomerization and activation could be exploited to

convert immunologically ‘cold’ tumors into ‘hot’ ones, thereby

augmenting existing immunotherapies. Across multiple cancer types,

hGBP2 abundance is positively associated with levels of

immune-related biomarkers, such as PD-1/PD-L1 and VISTA,

immune-cell infiltration and IPS, revealing its potential as a

robust tumor biomarker for assessing the activation level of TIME

and prognosis. Additionally, the methylation status of the

hGBP2 promoter also has also emerged as a promising

diagnostic indicator in SKCM and BC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was Supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82104603), Beijing Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 7204322), Peking University People's Hospital

Research and Development Fund (grant nos. RDZH2022-04, RS2021-12

and RDX2021-08).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZL performed project administration, methodology,

data curation and wrote the draft. SP performed visualization and

reviewed the manuscript. JO conceived and designed the review, and

was involved in funding acquisition, supervision, proofreading and

revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

GBP2

|

guanylate-binding protein 2

|

|

Pin1

|

peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase

NIMA-interacting 1

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

IRF

|

IFN-regulatory factor

|

|

TIME

|

tumor immunosuppressive

microenvironment

|

|

ccRCC

|

clear cell renal cell carcinoma

|

|

SKCM

|

skin cutaneous melanoma

|

|

BC

|

breast cancer

|

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma

|

References

|

1

|

Cheng YS, Colonno RJ and Yin FH:

Interferon induction of fibroblast proteins with guanylate binding

activity. J Biol Chem. 258:7746–7750. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vestal DJ, Buss JE, McKercher SR, Jenkins

NA, Copeland NG, Kelner GS, Asundi VK and Maki RA: Murine GBP-2: A

new IFN-gamma-induced member of the GBP family of GTPases isolated

from macrophages. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 18:977–985. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Quan ST, Jiao WW, Xu F, Sun L, Qi H and

Shen A: Advances in the regulation of inflammasome activation by

GBP family in infectious diseases. Yi Chuan. 45:1007–1017.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Britzen-Laurent N, Bauer M, Berton V,

Fischer N, Syguda A, Reipschläger S, Naschberger E, Herrmann C and

Stürzl M: Intracellular trafficking of guanylate-binding proteins

is regulated by heterodimerization in a hierarchical manner. PLoS

One. 5:e142462010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Modiano N, Lu YE and Cresswell P: Golgi

targeting of human guanylate-binding protein-1 requires nucleotide

binding, isoprenylation, and an IFN-gamma-inducible cofactor. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:8680–8685. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kirkby M, Enosi Tuipulotu D, Feng S, Lo

Pilato J and Man SM: Guanylate-binding proteins: Mechanisms of

pattern recognition and antimicrobial functions. Trends Biochem

Sci. 48:883–893. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim BH, Chee JD, Bradfield CJ, Park ES,

Kumar P and MacMicking JD: Interferon-induced guanylate-binding

proteins in inflammasome activation and host defense. Nat Immunol.

17:481–489. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Luo Y, Jin H, Kim JH and Bae J:

Guanylate-binding proteins induce apoptosis of leukemia cells by

regulating MCL-1 and BAK. Oncogenesis. 10:542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu YT and Sun ZJ: Turning cold tumors

into hot tumors by improving T-cell infiltration. Theranostics.

11:5365–5386. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Galon J and Bruni D: Approaches to treat

immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination

immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 18:197–218. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu B, Huang R, Fu T, He P, Du C, Zhou W,

Xu K and Ren T: GBP2 as a potential prognostic biomarker in

pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PeerJ. 9:e114232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang S, Chen K, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Xu L,

Liu T and Yu S: Lower expression of GBP2 associated with less

immune cell infiltration and poor prognosis in skin cutaneous

melanoma (SKCM). J Immunother. 45:274–283. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tang JH: Structural study of human

guanylate binding protein GBP2. 2019.

|

|

14

|

Ban T, Heymann JA, Song Z, Hinshaw JE and

Chan DC: OPA1 disease alleles causing dominant optic atrophy have

defects in cardiolipin-stimulated GTP hydrolysis and membrane

tubulation. Hum Mol Genet. 19:2113–2122. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Daumke O and Praefcke GJK: Mechanisms of

GTP hydrolysis and conformational transitions in the dynamin

superfamily. Biopolymers. 109:e230792018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Roy S, Wang B, Roy K, Tian Y, Bhattacharya

M, Williams S and Yin Q: Crystal structures reveal

nucleotide-induced conformational changes in G motifs and distal

regions in human guanylate-binding protein 2. Commun Biol.

8:2822025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kravets E, Degrandi D, Ma Q, Peulen TO,

Klümpers V, Felekyan S, Kühnemuth R, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Seidel CA

and Pfeffer K: Guanylate binding proteins directly attack

Toxoplasma gondii via supramolecular complexes. Elife.

5:e114792016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kravets E, Degrandi D, Weidtkamp-Peters S,

Ries B, Konermann C, Felekyan S, Dargazanli JM, Praefcke GJ, Seidel

CA, Schmitt L, et al: The GTPase activity of murine

Guanylate-binding protein 2 (mGBP2) controls the intracellular

localization and recruitment to the parasitophorous vacuole of

toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem. 287:27452–27466. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Neun R, Richter MF, Staeheli P and

Schwemmle M: GTPase properties of the interferon-induced human

Guanylate-binding protein 2. FEBS Lett. 390:69–72. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rajan S, Pandita E, Mittal M and Sau AK:

Understanding the lower GMP formation in large GTPase hGBP-2 and

role of its individual domains in regulation of GTP hydrolysis.

FEBS J. 286:4103–4121. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Honkala AT, Tailor D and Malhotra SV:

Guanylate-binding protein 1: An emerging target in inflammation and

cancer. Front Immunol. 10:31392019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cui W, Braun E, Wang W, Tang J, Zheng Y,

Slater B, Li N, Chen C, Liu Q, Wang B, et al: Structural basis for

GTP-induced dimerization and antiviral function of

guanylate-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

118:e20222691182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Abdullah N, Balakumari M and Sau AK:

Dimerization and its role in GMP formation by human guanylate

binding proteins. Biophys J. 99:2235–2244. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ and Gay

NJ: Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of

ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a

common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945–951. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wittinghofer A and Vetter IR:

Structure-function relationships of the G domain, a canonical

switch motif. Annu Rev Biochem. 80:943–971. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ghosh A, Praefcke GJ, Renault L,

Wittinghofer A and Herrmann C: How guanylate-binding proteins

achieve assembly-stimulated processive cleavage of GTP to GMP.

Nature. 440:101–104. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Olszewski MA, Gray J and Vestal DJ: In

silico genomic analysis of the human and murine Guanylate-binding

protein (GBP) gene clusters. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 26:328–352.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ramsauer K, Farlik M, Zupkovitz G, Seiser

C, Kröger A, Hauser H and Decker T: Distinct modes of action

applied by transcription factors STAT1 and IRF1 to initiate

transcription of the IFN-gamma-inducible gbp2 gene. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 104:2849–2854. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Michalska A, Blaszczyk K, Wesoly J and

Bluyssen HAR: A positive feedback amplifier circuit that regulates

interferon (IFN)-Stimulated gene expression and controls type I and

type II IFN responses. Front Immunol. 9:11352018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Guimarães DP, Oliveira IM, de Moraes E,

Paiva GR, Souza DM, Barnas C, Olmedo DB, Pinto CE, Faria PA, De

Moura Gallo CV, et al: Interferon-inducible guanylate binding

protein (GBP)-2: A novel p53-regulated tumor marker in esophageal

squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 124:272–279. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu ZH, Cai F and Zhong Y: Comprehensive

analysis of the expression and prognosis for GBPs in head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 10:60852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Du CH, Wu YD, Yang K, Liao WN, Ran L, Liu

CN, Zhang SZ, Yu K, Chen J, Quan Y, et al: Apoptosis-resistant

megakaryocytes produce large and hyperreactive platelets in

response to radiation injury. Mil Med Res. 10:662023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mondal S, Adhikari N, Banerjee S, Amin SA

and Jha T: Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and its inhibitors in

cancer: A minireview. Eur J Med Chem. 194:1122602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ngo CC and Man SM: Mechanisms and

functions of guanylate-binding proteins and related

interferon-inducible GTPases: Roles in intracellular lysis of

pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 192017.doi: 10.1111/cmi.12791.

|

|

35

|

Meunier E and Broz P: Interferon-inducible

GTPases in cell autonomous and innate immunity. Cell Microbiol.

18:168–180. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fu J and Wu H: Structural mechanisms of

NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. Annu Rev Immunol.

41:301–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wandel MP, Kim BH, Park ES, Boyle KB,

Nayak K, Lagrange B, Herod A, Henry T, Zilbauer M, Rohde J, et al:

Guanylate-binding proteins convert cytosolic bacteria into

caspase-4 signaling platforms. Nat Immunol. 21:880–891. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K,

Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung QT,

et al: Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical

inflammasome signalling. Nature. 526:666–671. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Huang S, Dong W, Lin X, Xu K, Li K, Xiong

S, Wang Z, Nie X and Bian JS: Disruption of the

Na+/K+-ATPase-purinergic P2X7 receptor complex in microglia

promotes Stress-induced anxiety. Immunity. 57:495–512.e11. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Garlanda C, Dinarello CA and Mantovani A:

The interleukin-1 family: Back to the future. Immunity.

39:1003–1018. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang Y, Liao Y, Hang Q, Sun D and Liu Y:

GBP2 acts as a member of the interferon signalling pathway in lupus

nephritis. BMC Immunology. 23:442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li X, Liu J, Zeng M, Yang K, Zhang S, Liu

Y, Yin X, Zhao C, Wang W and Xiao L: GBP2 promotes M1 macrophage

polarization by activating the notch1 signaling pathway in diabetic

nephropathy. Front Immunol. 14:11276122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Schori C, Trachsel C, Grossmann J, Barben

M, Klee K, Storti F, Samardzija M and Grimm C: A chronic hypoxic

response in photoreceptors alters the vitreous proteome in mice.

Exp Eye Res. 185:1076902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

An Y, Xu J, Hu X, Xu M, Yang X and Liu T:

GBP2 regulates lipid metabolism by inhibiting the HIF-1 pathway to

alleviate the progression of allergic rhinitis. Cell Biochem

Biophys. 83:1689–1701. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang G, Jin S, Ling X, Li Y, Hu Y, Zhang

Y, Huang Y, Chen T, Lin J, Ning Z, et al: Proteomic profiling of

LPS-induced Macrophage-derived exosomes indicates their involvement

in acute liver injury. Proteomics. 19:e18002742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Huang W, Zhang Y, Zheng B, Ling X, Wang G,

Li L and Meng Y: GBP2 upregulated in LPS-stimulated

macrophages-derived exosomes accelerates septic lung injury by

activating epithelial cell NLRP3 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol.

124:1110172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gao R, Ali T, Liu Z, Li A, Hao L, He L, Yu

X and Li S: Ceftriaxone averts neuroinflammation and relieves

depressive-like behaviors via GLT-1/TrkB signaling. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 701:1495502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ren Y, Yang B, Guo G, Zhang J, Sun Y, Liu

D, Guo S, Wu Y, Wang X, Wang S, et al: GBP2 facilitates the

progression of glioma via regulation of KIF22/EGFR signaling. Cell

Death Discov. 8:2082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yu S, Yu X, Sun L, Zheng Y, Chen L, Xu H,

Jin J, Lan Q, Chen CC and Li M: GBP2 enhances glioblastoma invasion

through Stat3/fibronectin pathway. Oncogene. 39:5042–5055. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Verdugo E, Puerto I and Medina MÁ: An

update on the molecular biology of glioblastoma, with clinical

implications and progress in its treatment. Cancer Commun (Lond).

42:1083–111. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Meng K, Li YY, Liu DY, Hu LL, Pan YL,

Zhang CZ and He QY: A five-protein prognostic signature with GBP2

functioning in immune cell infiltration of clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 21:2621–2630. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Rahvar F, Salimi M and Mozdarani H: Plasma

GBP2 promoter methylation is associated with advanced stages in

breast cancer. Genet Mol Biol. 43:e201902302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Godoy P, Cadenas C, Hellwig B, Marchan R,

Stewart J, Reif R, Lohr M, Gehrmann M, Rahnenführer J, Schmidt M

and Hengstler JG: Interferon-inducible guanylate binding protein

(GBP2) is associated with better prognosis in breast cancer and

indicates an efficient T cell response. Breast Cancer. 21:491–499.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li NN, Qiu XT, Xue JS, Yi LM, Chen ML and

Huang ZJ: Predicting the prognosis and immunotherapeutic response

of Triple-negative breast cancer by constructing a prognostic model

based on CD8+ T Cell-related immune genes. Biomed Environ Sci.

37:581–593. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ji G, Luo B, Chen L, Shen G and Tian T:

GBP2 is a favorable prognostic marker of skin cutaneous melanoma

and affects its progression via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Ann Clin

Lab Sci. 51:772–782. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zheng W, Ye S, Liu B, Liu D, Yan R, Guo H,

Yu H, Hu X, Zhao H, Zhou K and Li G: Crosstalk between GBP2 and M2

macrophage promotes the ccRCC progression. Cancer Science.

115:3570–3586. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Tian Y, Wang H, Guan W, Tu X, Zhang X, Sun

Y, Qian C, Song X, Peng B and Cui X: GBP2 serves as a novel

prognostic biomarker and potential immune microenvironment

indicator in renal cell carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 61:1082–1098.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

AmeliMojarad M, AmeliMojarad M and Cui X:

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis identified GBP2

connected to PPARα activity and liver cancer. Sci Rep.

14:207452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wang H, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Fang S, Zhang M,

Li H, Xu F, Liu L, Liu J, Zhao Q and Wang F: Subtyping of

microsatellite stability colorectal cancer reveals guanylate

binding protein 2 (GBP2) as a potential immunotherapeutic target. J

Immunother Cancer. 10:e0043022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Qi F, Gao N, Li J, Zhou C, Jiang J, Zhou

B, Guo L, Feng X, Ji J, Cai Q, et al: A multidimensional

recommendation framework for identifying biological targets to aid

the diagnosis and treatment of liver metastasis in patients with

colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 23:2392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang Y, Pan J, An F, Chen K, Chen J, Nie

H, Zhu Y, Qian Z and Zhan Q: GBP2 is a prognostic biomarker and

associated with immunotherapeutic responses in gastric cancer. BMC

Cancer. 23:9252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Xiong J, Huang J, Xu H, Wu Q, Zhao J, Chen

Y, Fan G, Guan H, Xiao R, He Z, et al: CpG-based nanovaccines

enhance ovarian cancer immune response by Gbp2-mediated remodeling

of tumor-associated macrophages. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24128812025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Feng D, Zhu W, Shi X, Wang Z, Wei W, Wei

Q, Yang L and Han P: Immune-related gene index predicts metastasis

for prostate cancer patients undergoing radical radiotherapy. Exp

Hematol Oncol. 12:82023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Uribe ML, Marrocco I and Yarden Y: EGFR in

cancer: Signaling mechanisms, drugs, and acquired resistance.

Cancers (Basel). 13:27482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B and Guan KL:

AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of

Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 13:132–141. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhang W, Tang X, Peng Y, Xu Y, Liu L and

Liu S: GBP2 enhances paclitaxel sensitivity in triple-negative

breast cancer by promoting autophagy in combination with ATG2 and

inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Int J Oncol. 64:342024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhang H, Sun Z, Li Y, Fan D and Jiang H:

MicroRNA-200c binding to FN1 suppresses the proliferation,

migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 88:285–292. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Shibata K, Kikkawa F, Nawa A, Thant AA,

Naruse K, Mizutani S and Hamaguchi M: Both focal adhesion kinase

and c-Ras are required for the enhanced matrix metalloproteinase 9

secretion by fibronectin in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res.

58:900–1093. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Xu TP, Huang MD, Xia R, Liu XX, Sun M, Yin

L, Chen WM, Han L, Zhang EB, Kong R, et al: Decreased expression of

the long non-coding RNA FENDRR is associated with poor prognosis in

gastric cancer and FENDRR regulates gastric cancer cell metastasis

by affecting fibronectin1 expression. J Hematol Oncol. 7:632014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Xue W, Yang L, Chen C, Ashrafizadeh M,

Tian Y and Sun R: Wnt/β-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human

cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 81:792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Peña-Blanco A and García-Sáez AJ: Bax, Bak

and beyond-mitochondrial performance in apoptosis. FEBS J.

285:416–431. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhang J, Zhang Y, Wu W, Wang F, Liu X,

Shui G and Nie C: Guanylate-binding protein 2 regulates

Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission to suppress breast cancer cell

invasion. Cell Death Dis. 8:e31512017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Liu W, Chen Y, Xie H, Guo Y, Ren D, Li Y,

Jing X, Li D, Wang X, Zhao M, et al: TIPE1 suppresses invasion and

migration through down-regulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway in gastric

cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 22:1103–1117. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wang J, Min H, Hu B, Xue X and Liu Y:

Guanylate-binding protein-2 inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth

and increases the sensitivity to paclitaxel of paclitaxel-resistant

colorectal cancer cells by interfering Wnt signaling. J Cell

Biochem. 121:1250–129. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Song JX, Wang Y, Hua ZP, Huang Y, Hu LF,

Tian MR, Qiu L, Liu H and Zhang J: FATS inhibits the Wnt pathway

and induces apoptosis through degradation of MYH9 and enhances

sensitivity to paclitaxel in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis.

15:8352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhang SW, Feng TB, Ning YL, Zhang XH and

Qi CJ: Guanylate-binding protein 2 regulates the maturation of

mouse dendritic cells induced by β-glucan. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi

Xue Za Zhi. 33:1153–1159. 2017.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Xu X, Ding X, Wang Z, Ye S, Xu J, Liang Z,

Luo R, Xu J, Li X and Ren Z: GBP2 inhibits pathological

angiogenesis in the retina via the AKT/mTOR/VEGFA axis. Microvasc

Res. 154:1046892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Du F, Liu M, Wang J, Hu L, Zeng D, Zhou S,

Zhang L, Wang M, Xu X, Li C, et al: Metformin coordinates with

mesenchymal cells to promote VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in diabetic

wound healing through Akt/mTOR activation. Metabolism.

140:1553982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J and Guan KL:

TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR

signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 4:648–6457. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Ruchko MV, Gorodnya OM, Pastukh VM, Swiger

BM, Middleton NS, Wilson GL and Gillespie MN: Hypoxia-induced

oxidative base modifications in the VEGF hypoxia-response element

are associated with transcriptionally active nucleosomes. Free

Radic Biol Med. 46:352–359. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wenger RH, Stiehl DP and Camenisch G:

Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE.

2005:re122005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Balasubramanian S, Fan M, Messmer-Blust

AF, Yang CH, Trendel JA, Jeyaratnam JA, Pfeffer LM and Vestal DJ:

The interferon-gamma-induced GTPase, mGBP-2, inhibitsc (TNF-alpha)

induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) by inhibiting

NF-kappaB and Rac protein. J Biol Chem. 286:20054–20064. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Raskov H, Orhan A, Christensen JP and

Gögenur I: Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer

immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 124:359–367. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Ye S, Li S, Qin L, Zheng W, Liu B, Li X,

Ren Z, Zhao H, Hu X, Ye N and Li G: GBP2 promotes clear cell renal

cell carcinoma progression through immune infiltration and

regulation of PD-L1 expression via STAT1 signaling. Oncol Rep.

49:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kutsch M and Coers J: Human guanylate

binding proteins: Nanomachines orchestrating host defense. FEBS J.

288:5826–5849. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Chakraborty S, Kasirajan A, Mariappan V,

Green SR and Pillai AKB: Guanylate binding proteins (GBPs) as novel

therapeutic targets against single-stranded RNA viruses. Mol Biol

Rep. 52:7802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|