Introduction

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) is a major

contributor to cancer-associated mortality worldwide, accounting

for a notable proportion of global cancer mortalities with a

5-year-survival probability of ~18%; of these occurrences, ~90% are

classified as HCC (1). Despite

advancements in surgical techniques, liver transplantation and

systemic therapies, the prognosis for patients with LIHC remains

poor (2). This poor prognosis is

primarily due to late-stage diagnoses, high recurrence rates and

resistance to conventional treatments (3,4).

Furthermore, the lack of reliable early detection biomarkers and

effective therapeutic options exacerbates the challenges in

managing LIHC (5). Consequently,

there is an urgent need to identify novel molecular biomarkers that

can serve as prognostic indicators and guide therapeutic

decision-making, thus ultimately improving patient outcomes.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a crucial driver

of cancer progression, with macrophages (particularly M2

macrophages) serving a central role in modulating immune responses

(6). M2 macrophages promote tumor

growth, metastasis and immune evasion by secreting cytokines such

as IL-10 and TGF-β, which suppress the activation of cytotoxic T

cells and natural killer (NK) cells (7,8).

Research has demonstrated that M2 macrophages notably influence the

progression of LIHC by promoting tumor growth and metastasis

(9). M2 macrophages are generally

considered to possess immunosuppressive properties, which enable

them to create a tumor-supportive microenvironment. These cells

achieve this effect by secreting a variety of cytokines and

chemokines that facilitate tumor cell survival and dissemination

(10,11). Previous studies have revealed that

M2 macrophages contribute to the initiation and progression of

liver cancer via interactions with hepatic stellate cells within

the LIHC microenvironment (12,13).

This crosstalk not only enhances the polarization of M2 macrophages

but also promotes tumor immune evasion by inhibiting the activity

of CD8+ T cells. Consequently, therapeutic strategies

targeting M2 macrophages may offer novel approaches for the

treatment of LIHC (11,14). Furthermore, M2 macrophages

contribute to resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy, thus

positioning these cells as critical targets for novel therapeutic

strategies (15). The elucidation

of the molecular mechanisms underlying M2 macrophage polarization

in LIHC may provide valuable insights into improving prognostic

assessment and enhancing treatment efficacy.

The present study aimed to explore the prognostic

significance of M2 macrophage-associated genes in LIHC and create a

predictive model for patient outcomes. Using data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, key genes associated with M2

macrophage infiltration were identified using the weighted gene

co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) algorithm. A risk model was

constructed based on these genes and validated using survival

analysis. Additionally, the potential of these genes as therapeutic

targets was examined by assessing their relationships with immune

checkpoint expression and responses to immunotherapy. The findings

offer valuable insights into the role of M2 macrophages in LIHC and

identify potential biomarkers for prognosis and immunotherapy

strategies.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The primary dataset used for data analysis included

the LIHC cohort from the TCGA database, which included gene

expression profiles and clinical data for patients with LIHC. The

raw RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data were processed and normalized to

the transcripts per million format to standardize the gene

expression levels across all samples. In addition, samples with a

reported survival time of 0 days were excluded from the analysis to

ensure the integrity and reliability of the survival data. To

validate the prognostic model, two independent external validation

datasets were used. The first dataset (GSE76427) was retrieved from

the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the second

dataset (LIRI-JP) was obtained from the International Cancer Genome

Consortium (ICGC) database (https://dcc.icgc.org/).

Evaluation of macrophage immune

infiltration in LIHC

To assess macrophage immune infiltration in LIHC and

normal tissue samples, six widely used immune infiltration

estimation methods were applied: CIBERSORT (16), xCell (17), TIMER (18), QUANTISEQ (19), EPIC (20) and MCPCOUNTER (21). These algorithms, which leverage

transcriptomic data, were used to quantify the relative levels of

macrophage infiltration in both LIHC and normal samples.

Additionally, the present study focused on the differential

expression of M2 macrophages and performed comparative analyses of

gene expression between patients with LIHC and normal controls.

Network construction, module

preservation and correlation analysis

WGCNA was employed to identify gene modules

associated with M2 macrophages (22). After excluding outlier samples, the

top 25% most variable genes were selected for subsequent analysis.

The optimal soft threshold for constructing the network was

determined by evaluating the scale-free topology model fit. A power

value that resulted in a fit close to 0.9 was chosen. The gene

co-expression network was subsequently constructed and modules were

identified based on hierarchical clustering. Preservation analysis

was performed to assess the reproducibility of the identified

modules. The modules were categorized as being strongly preserved

(Z >10), weakly preserved (2<Z<10) or not preserved

(Z<2). Modules with poor preservation were excluded from further

analysis. Finally, the correlation between M2 macrophage expression

levels and the identified gene modules was assessed using various

immune infiltration methods. The modules with the greatest

correlations with M2 macrophages were selected for further

modelling.

Prognostic gene selection and M2

macrophages-related model development

Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed on

292 genes to identify those associated with prognosis in LIHC.

Genes with P-values <0.05 were selected for further

investigation. To refine this selection, Least Absolute Shrinkage

and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression was performed with

10-fold cross-validation to identify the optimal regularization

parameter (λ). A λ-value that optimized the model fit while

minimizing overfitting was chosen. Multivariate Cox regression was

subsequently performed to evaluate the independent prognostic value

of the selected genes. A prognostic risk score model was developed

based on the expression levels of these genes, which were weighted

by their respective regression coefficients. The risk score formula

was calculated by multiplying the expression level of each gene by

its corresponding coefficient. To assess the model's predictive

accuracy, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and time-dependent

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to

evaluate overall survival (OS) and model performance in both the

training cohort (GSE76427) and independent validation cohorts

(LIRI-JP).

Functional enrichment analysis

To examine the differential activation of biological

pathways between the two risk groups, gene set variation analysis

(GSVA) was performed on the hallmark gene sets (23). GSVA scores were computed for each

gene set and differential expression analysis was performed to

identify the pathways with significant differential activation

between the two groups. In addition, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

was performed to identify biological processes and cellular

components that were differentially enriched in the two risk

groups. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analysis with the package ‘clusterprofiler’ of R studio

(24) was also performed to examine

differences in signaling pathway activation between the groups. For

all the analyses, statistical significance was assessed using the

Benjamini-Hochberg method to correct for multiple comparisons.

Immune infiltration, tumor mutational

burden (TMB) and immune checkpoint analysis

To assess the relationships between immune

characteristics and risk stratification, the ESTIMATE algorithm

(ESTIMATE: Home) was first applied to quantify the scores for each

patient with LIHC. Pearson correlation analyses were subsequently

performed to examine the associations between these scores and the

prognostic risk score. The TMB was also evaluated for each patient

and a correlation analysis was performed with the risk score to

determine whether the TMB was associated with the risk profile. To

further explore immune responses, we employed the ‘limma’ package

of R studio to conduct differential expression analysis was

performed on common inhibitory and stimulatory immune checkpoint

genes with the threshold of |log2 fold change|>1.5 and

P<0.05. The expression of these genes was compared between the

two risk groups to investigate their potential roles in immune

evasion and therapeutic resistance. Additionally, the Tumor Immune

Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) algorithm was employed to assess

the immune escape potential in both risk groups (25). Finally, the Submap algorithm was

applied to predict the likelihood of patient response to immune

checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy based on the gene expression

signatures (26).

Single-cell (sc)RNA-seq based on the

tumor immune single cell Hub 2 (TISCH2) database

The killer cell lectin like receptor B1 (KLRB1),

with the smallest P-value in the multivariate Cox regression, was

analyzed across multiple single-cell datasets to investigate its

role in the TME. Using the TISCH2 database (27), the expression of KLRB1 was assessed

in six independent scRNA-seq datasets (http://tisch.compbio.cn/home/). The expression levels

of KLRB1 were compared across various immune cell types, including

CD8+ T cells, CD8+ exhausted T cells (Tex)

and NK cells. Ligand-receptor interactions were also examined

between different cell populations using a heatmap to visualize the

strength of these interactions. The interactions were further

represented as a network diagram to illustrate the intensity or

activity of ligand-receptor signaling, specifically between

CD8+ T cells and other cell types in the TME.

Pan-cancer expression and prognostic

analysis of KLRB1

To investigate the potential role of KLRB1 in cancer

biology, a pan-cancer analysis was performed using data from TCGA.

First, KLRB1 expression across various cancer types (including

LIHC) was assessed to identify significant differences in

expression. The prognostic value of KLRB1 was subsequently examined

by analyzing its expression in relation to clinical outcomes,

including the disease-free interval (DFI), disease-specific

survival (DSS), OS and platinum-free interval (PFI) parameters

across various cancer types. A forest plot analysis was performed

to further investigate the relationship between KLRB1 expression

and OS across various cancers. Finally, the samples were

categorized into high- and low-KLRB1 groups and differential

expression analysis was performed. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(GSEA) was subsequently used to identify enriched biological

pathways in the high- and low-expression groups, thus providing

insights into the potential mechanisms through which KLRB1

influences tumor progression.

Cell culture

The HuH-1 (CL-0811), HuH-7 (CL-0120), and THP-1

(CL-0233) cell lines were purchased from Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd. The HuH-1 and HuH-7 cells were cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from GIBCO;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The THP-1 cells were cultured in

RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (all from GIBCO; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C

with a 5% CO2 atmosphere to ensure optimal growth

conditions.

Construction of KLRB1 knockdown and

overexpression cell lines

A lentivirus-based short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

strategy was employed using three distinct shRNA sequences to

downregulate KLRB1 expression in HuH-7 cells. These shRNA sequences

were cloned into the lentiviral vector pLKO.1. Simultaneously,

full-length KLRB1 complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by PCR

using total RNA extracted from HuH-1 cells and cloned into the

lentiviral overexpression vector pLV-CMV-MCS-PGK-Puro to induce

KLRB1 overexpression in HuH-1 cells. Both vectors were obtained

from Addgene (Beijing Zhongyuan Co.). For lentivirus production, 10

µg of pLV-CMV-MCS-PGK-Puro was co-transfected with 7.5 µg of

packaging plasmid (pMDLg/pRRE; Addgene; Beijing Zhongyuan Co.), 2.5

µg of envelope plasmid (VSV-G; Addgene; Beijing Zhongyuan Co.) and

15 µg of a helper plasmid (pRSV-Rev; Addgene; Beijing Zhongyuan

Co.) using the calcium phosphate transfection method as part of a

3rd generation lentiviral system. Transfection was performed at

37°C for 48 h. Lentiviral particles were generated by

co-transfecting 293T cells (Procell Life Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) with a packaging plasmid mix (REV: VSVG: PMDL=2:3:5)

using TurboFect transfection reagent (cat. no. R0532; Fermentas;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), with virus supernatant harvested

36–48 h post-transfection and filtered for use in infection. HuH-7

and HuH-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates until reaching 60–70%

confluency before infection with lentiviral particles at a

multiplicity of infection of 10, supplemented with poly-L-lysine (8

µg/ml) to enhance transduction. Following 12–16 h of co-culture

with the virus, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium.

After 48 h, stable transductants were selected using 2 µg/ml

puromycin (the original concentration was 1 mg/ml) to confirm

successful transduction. All procedures were conducted at 37°C with

5% CO2. The sequences utilized for KLRB1 knockdown and

overexpression are shown in Table

SI.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

According to the manufacturer's protocol, total RNA

was extracted from tissue samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, a cDNA synthesis kit

(cat. no. R212-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used to convert

the RNA into cDNA. The qPCR experiments were conducted using SYBR

Green qRT-PCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), with GAPDH

serving as the internal control for normalization and the

2−ΔΔCq method (28) was

used to analyze the difference. The thermocycling protocol

consisted of an initial pre-denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing

at 60°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec. The primer

sequences used are listed in Table

SII.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using a Cell

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of

2,500 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 3

days. A total of 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well for

1 h before measurement of the absorbance at 450 nm at room

temperature.

Transwell migration assay

A Transwell chamber (pore size, 8 µm; Corning, Inc.)

was used to assess the migratory ability of the cells. Target cells

(typically 1×105 cells per well) were seeded into the

upper chamber of the Transwell system, with serum-free medium used

as the inducer. The lower chamber contained complete culture medium

supplemented with 10% serum (GIBCO; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

as a chemoattractant to guide cell migration. The cells were

incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 to 48 h,

thus allowing the cells to migrate through the membrane into the

lower chamber. After incubation, non-migrating cells in the upper

chamber were gently removed with a cotton swab. The cells in the

lower chamber were subsequently washed with PBS, fixed with

methanol at room temperature for 30 min and stained with 0.1%

crystal violet solution at room temperature for 10 min. Finally,

the stained cells in the lower chamber were observed and counted

under an inverted microscope to assess the migratory ability of the

cells through the software of Image J (version 1.8.0_345; National

Institutes of Health).

Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI)

staining assay

To assess cell apoptosis, the Annexin V-FITC/PI

(BioLegend, Inc.) dual-staining method was used. First, sh-KLRB1-2

and OE-KLRB1 cells were seeded into culture dishes and cultured

until they reached 70–80% confluence. After treatment, the cells

were collected and washed twice with PBS to remove residual culture

medium. The cells were then resuspended in 1× binding buffer and

stained with annexin V-FITC and PI solution. The mixture was gently

vortexed and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min.

Annexin V-FITC binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface

of the cell membrane, thereby marking early apoptotic cells,

whereas PI stains the nuclei of late apoptotic or necrotic cells

with compromised membrane integrity. After staining, apoptosis was

analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSAria III; BD Biosciences) and

evaluation using FlowJo (version 10.8.1). The dual fluorescence

signals from annexin V-FITC and PI allowed for the distinction

between healthy cells, early apoptotic cells, late apoptotic cells

and necrotic cells, thereby providing a comprehensive assessment of

the apoptotic status of the cells.

Cell tube formation assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

(PUMC-HUVEC-T1; cat. no. CL-0675) were obtained from Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. The third to the fifth passage

of HUVECs in the logarithmic growth phase were used for the

subsequent experiments. The cell tube formation assay involved

seeding HUVECs onto a solidified layer of Matrigel® and

incubation for 4 to 6 h at 37°C to allow tube formation in a

96-well plate. After the cells were incubated with the coculture

supernatant of HuH-7 or HuH-1 cells for 8 h at 37°C, tube-like

structures formed. After the incubation period, the formation of

tube-like structures was examined under a fluorescence microscope.

The degree of tube formation was quantified by assessing parameters

such as the number of branches and total branching length through

Image J (version 1.8.0_345).

qPCR detection of macrophage cell

polarization

To evaluate the polarization status of M0 cells, the

expression levels of polarization marker genes were assessed using

qPCR. The THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from

GIBCO; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cultures were maintained in

a humidified incubator at 37°C with a 5% CO2 atmosphere

to ensure optimal growth conditions. THP-1 cells were first treated

with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 48 h to induce

differentiation into M0 cells. The culture supernatants from

sh-KLRB1-2 and OE-KLRB1 cells were subsequently added to the M0

cells for 24 h at 37°C, after which the gene expression of the M1

and M2 markers was measured. According to manufacturer's protocol,

total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse

transcription was performed to generate cDNA according to the

manufacturer's instructions using a reverse transcription kit (cat.

no. R212-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). SYBR Green fluorescence dye

(Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used for qPCR. Specifically, the

first stage involved pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, for one

cycle. Then the second stage began, which involved denaturation at

95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C

for 20 sec, for 40 cycles. The relative expression levels of the M1

and M2 marker genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (28), with GAPDH serving as

the internal control. The expression levels of both M1 markers

(CD86 and IL-12) and M2 markers (IL-10 and CD206) were measured.

The sequences of the primers utilized are listed in Table SII.

Western blot analysis

The total protein of cells was obtained using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for 30 sec (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The total protein was

separated using 10% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were

subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (GE

Healthcare). Following a 2-h blocking step at room temperature with

5% non-fat dry milk (Yili), the membranes were incubated with the

primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were as

follows: Bax (1:500 dilution; cat. no. A12009), Bcl-2 (1:1,000

dilution; cat. no. A19693), C-caspase-3 (1:500 dilution; cat. no.

A11319) and β-actin (1:10,000 dilution; cat. no. AC038; all from

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the membranes were

incubated with the secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution; cat. no.

AB_1185567; goat anti-rabbit IgG; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. The blots were

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) and analyzed densitometrically using

ImageJ software (version 1.8.0_345).

Statistical analysis

All bioinformatics analyses in the present study

were performed using R Studio version 4.3.1 (https://cran.rstudio.com/bin/windows/base/old/4.3.1/),

while data were processed with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics).

Statistical comparisons between two groups were assessed using an

unpaired Student's t-test, whereas differences among multiple

groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni's test

was used as the post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference. To ensure reproducibility,

all experiments were repeated at least three times, with results

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Differential expression of M2

macrophages in patients with LIHC and normal controls

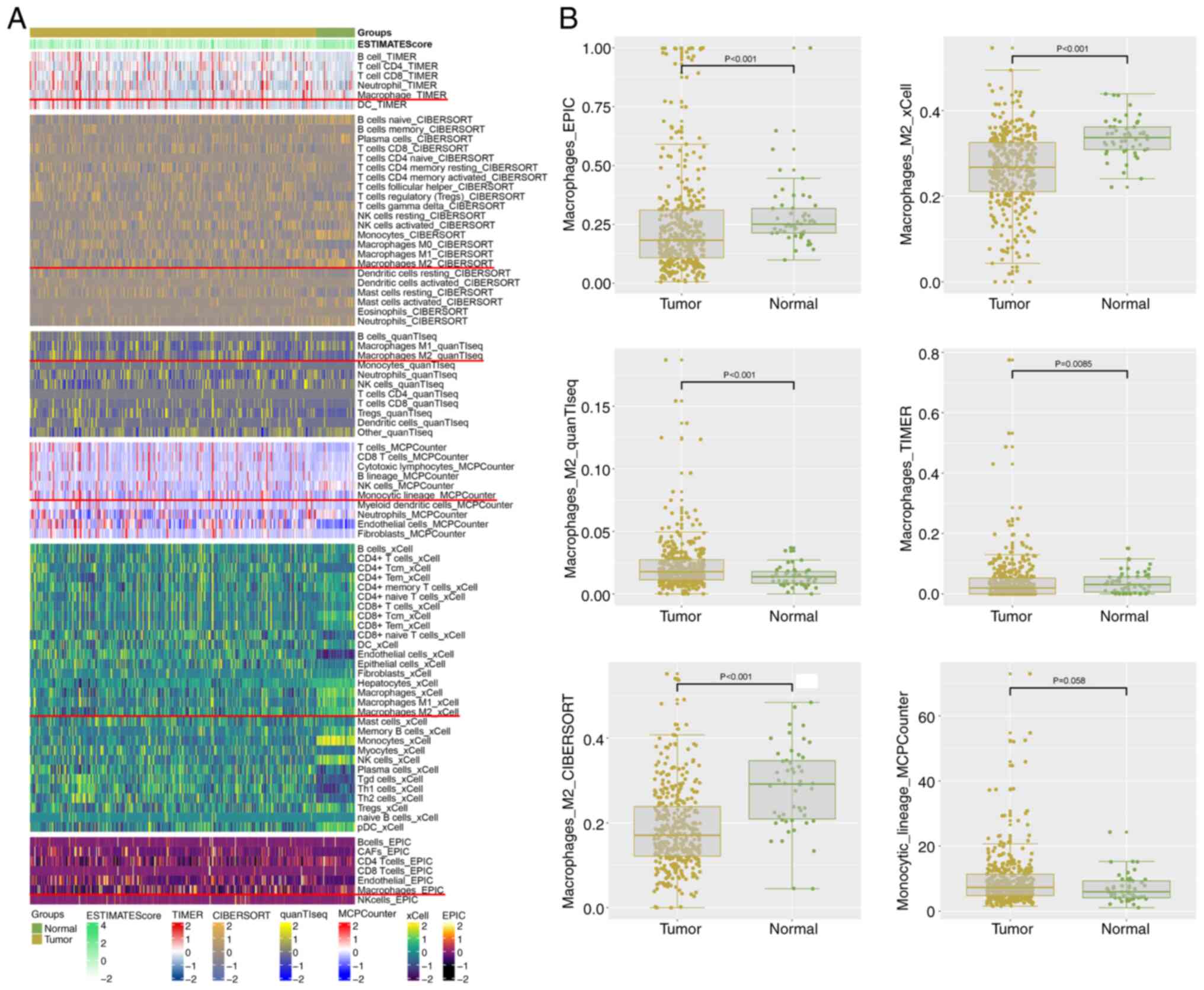

Macrophage infiltration levels in LIHC and normal

tissue samples were evaluated using six immune infiltration

analysis methods. The heatmap shown in Fig. 1A illustrates the distribution of

infiltrating macrophages in both LIHC and normal samples across the

different methods. Differential expression analysis of M2

macrophages (Fig. 1B) revealed

significant differences between patients with LIHC and normal

controls. Notably, all analysis methods indicated relevant

findings, except for the MCPCOUNTER method, which did not show a

statistically significant difference. Specifically, quantTIseq

exhibited a significant decrease, while the other methods

demonstrated increases in expression. Consequently, the results are

inconsistent across the different approaches. These results

underscore the potential involvement of M2 macrophages in the

immune microenvironment of LIHC.

Identification of M2

macrophage-related gene modules

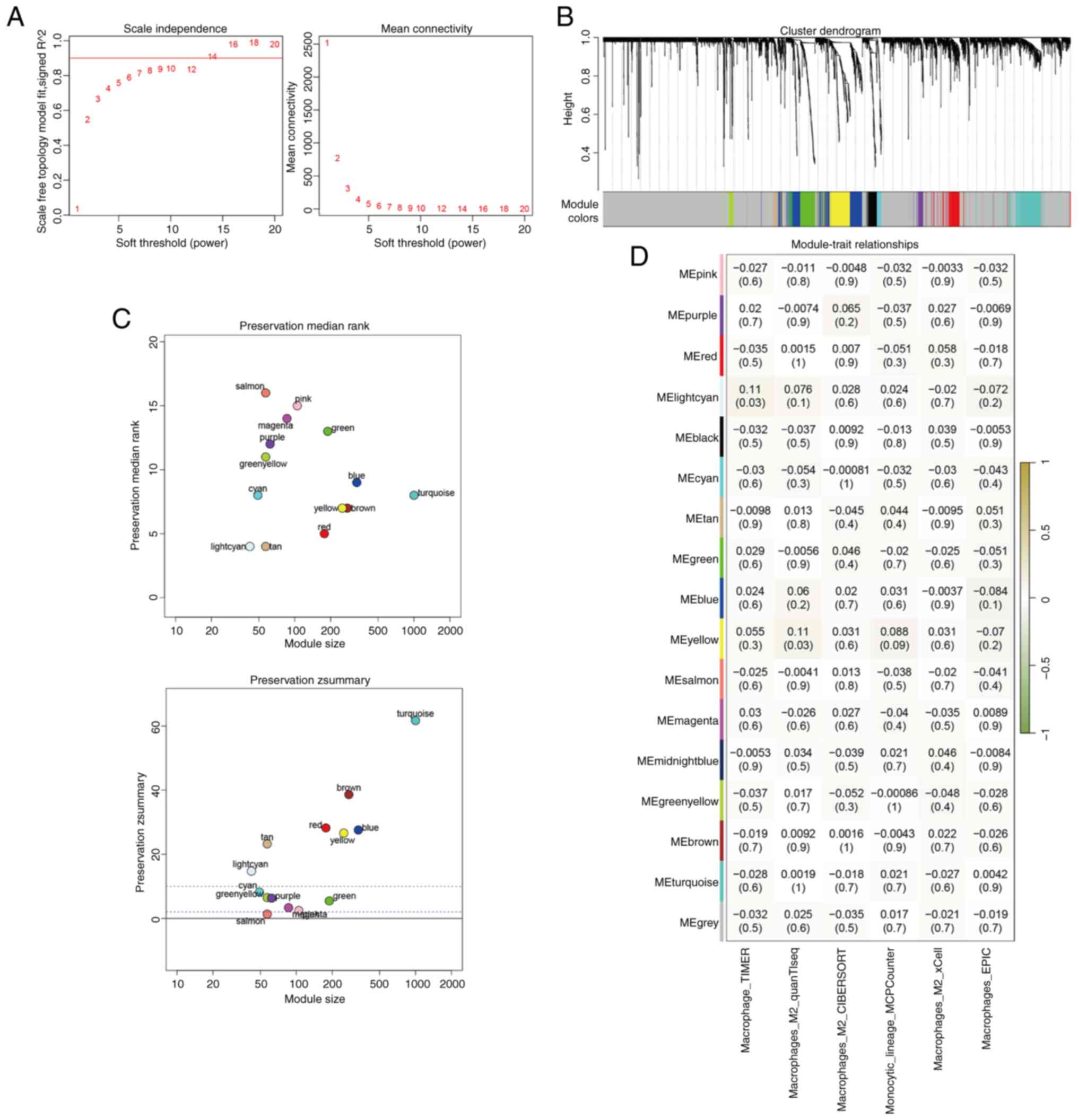

The optimal soft threshold for constructing the gene

co-expression network was determined to be 14, which yielded a

scale-free topology model fit value approaching 0.9 (Fig. 2A). A total of 16 distinct gene

modules were identified using WGCNA (Fig. 2B). Preservation analysis indicated

that four modules (grey, gold, midnight blue and black)

demonstrated Z scores <2, thereby indicating poor preservation;

thus, these modules were excluded from further analysis (Fig. 2C). Correlation analysis between M2

macrophage expression levels and the gene modules revealed that the

light cyan and yellow modules were the most strongly correlated

with M2 macrophages (Fig. 2D).

Genes from these two modules were selected for subsequent

prognostic modelling.

Development and validation of the M2

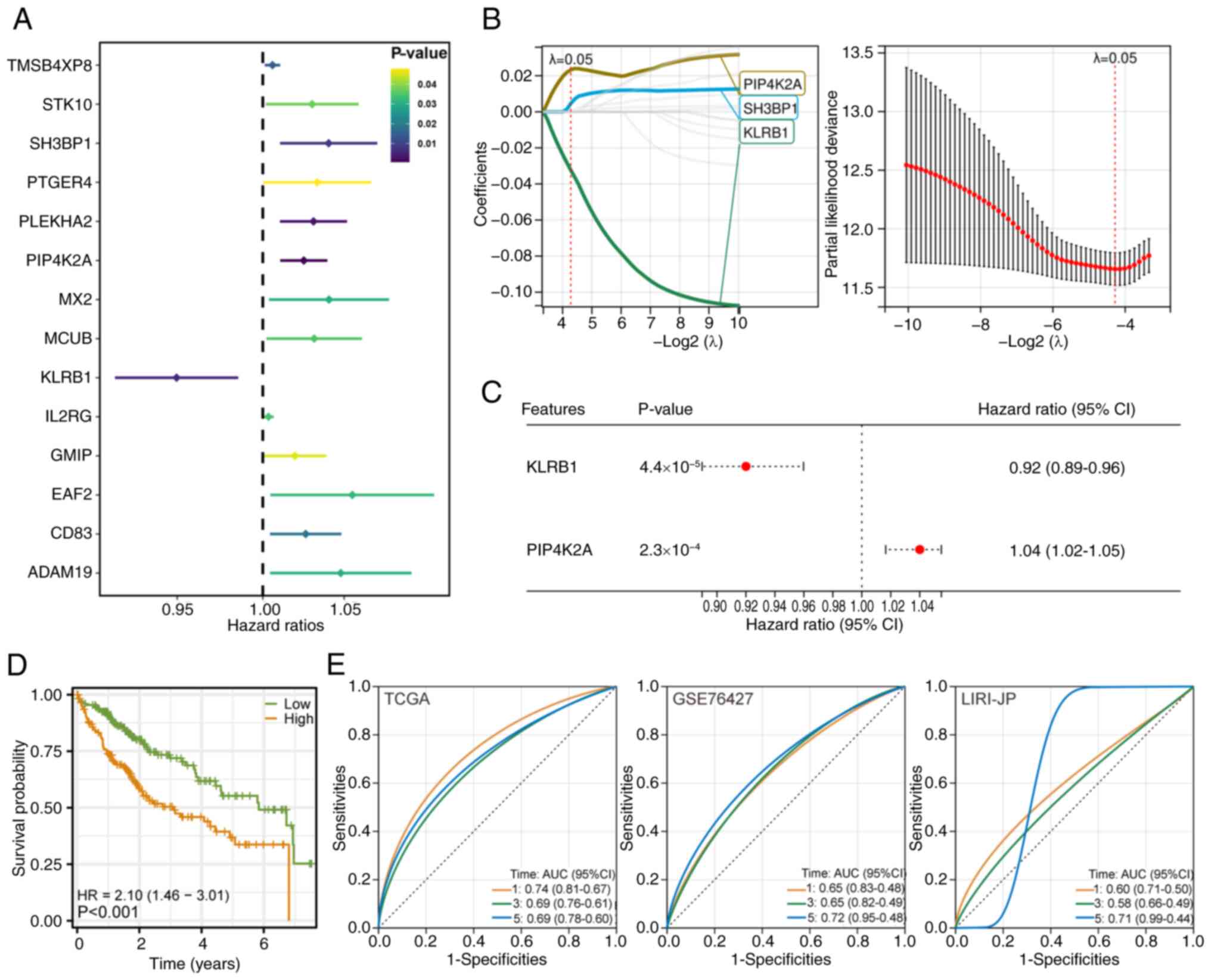

macrophage-related genes prognostic model

Univariate Cox regression analysis identified 14

genes with significant associations with patient prognosis

(P<0.05) in the LIHC cohort (Fig.

3A). LASSO regression analysis (with a λ value of 0.0514)

revealed three genes for inclusion in the final model, including

KLRB1 (Fig. 3B). Multivariate Cox

regression analysis validated the independent prognostic value of

these three genes. The prognostic risk score model was constructed

based on the following formula:

RiskScore=phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate 4-kinase type 2α

(PIP4K2A) × 1.0165 + KLRB1 × 0.8897 (Fig. 3C). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

revealed significant differences in survival between the two risk

groups (Fig. 3D). The model's

performance was validated using time-dependent ROC analysis, which

demonstrated a certain predictive ability across three separate

cohorts, including TCGA LIHC, GSE76427 (GEO) and LIRI-JP (ICGC)

(Fig. 3E).

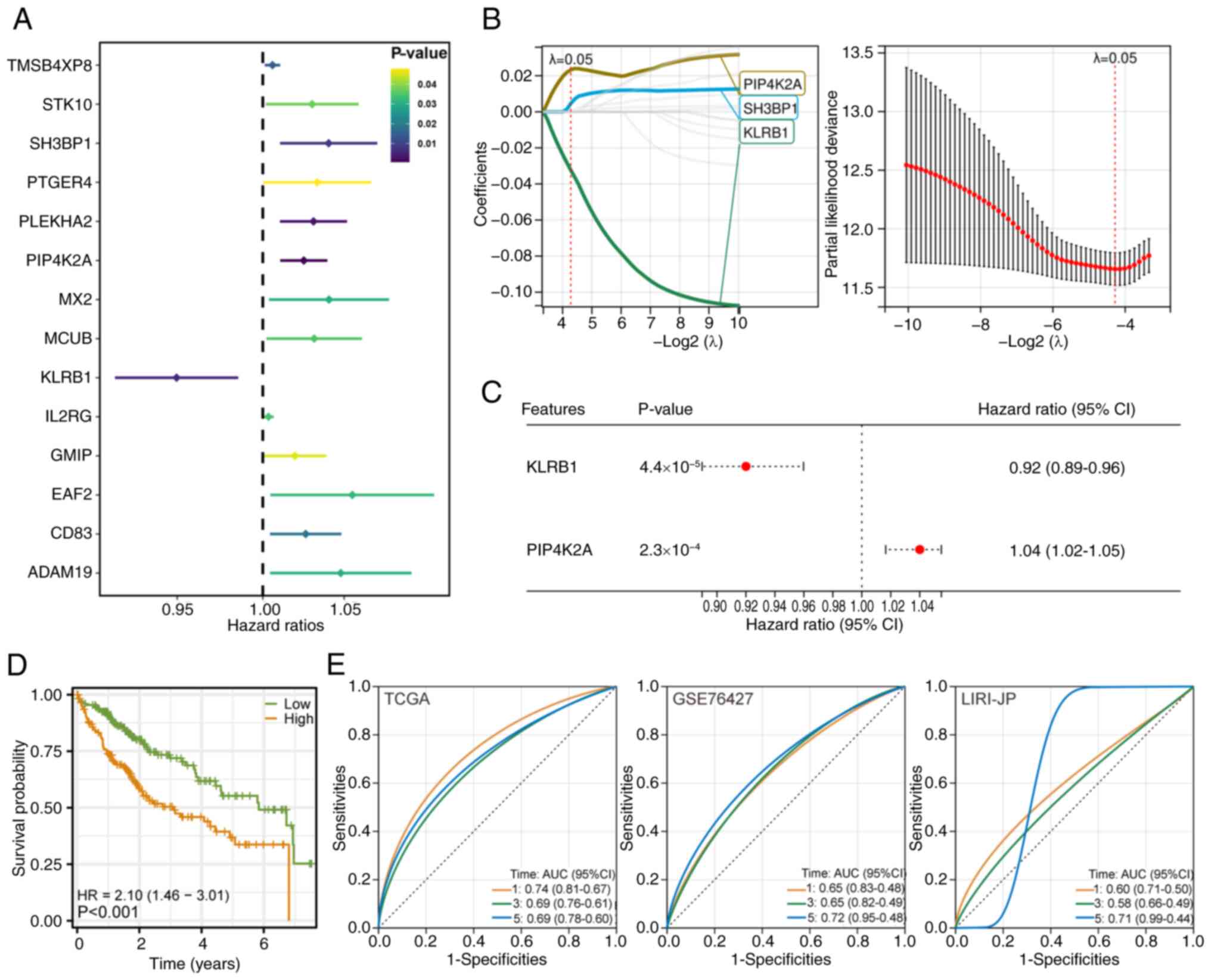

| Figure 3.Development and validation of the M2

macrophage-related prognostic model. (A) Univariate Cox regression

analysis identified 14 genes with significant prognostic value

(P<0.05) in patients with LIHC. (B) Least Absolute Shrinkage and

Selection Operator-Cox regression was applied to refine the gene

set, selecting three key genes based on a λ value of 0.0514

(10-fold cross-validation). (C) Multivariate Cox regression

confirmed the independent prognostic significance of the two

selected genes. A prognostic risk score model was constructed using

the following formula: RiskScore = PIP4K2A × 1.0165 + KLRB1 ×

0.8897. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing two risk groups

in the TCGA-LIHC cohort. A significant difference in overall

survival was observed between the groups. (E) Time-dependent

receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of the prognostic

risk score model, showing certain predictive performance across

three independent cohorts: TCGA-LIHC, GSE76427 (Gene Expression

Omnibus) and LIRI-JP (International Cancer Genome Consortium).

LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; PIP4K2A, phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate 4-kinase type 2α;

SH3BP1, SH3 domain binding protein 1; KLRB1, killer cell lectin

like receptor B1; AUC, area under the curve; TMSB4XP8, TMSB4X

pseudogene 8; STK10, serine/threonine kinase 10; PTGER4,

prostaglandin E receptor 4; PLEKHA2, pleckstrin homology domain

containing A2; MX2, MX dynamin like GTPase 2; MCUB, mitochondrial

calcium uniporter dominant negative subunit β; IL2RG, IL2 receptor

subunit γ; GMIP, GEM interacting protein; EAF2, ELL associated

factor 2; ADAM19, ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19; HR, hazard

ratio. |

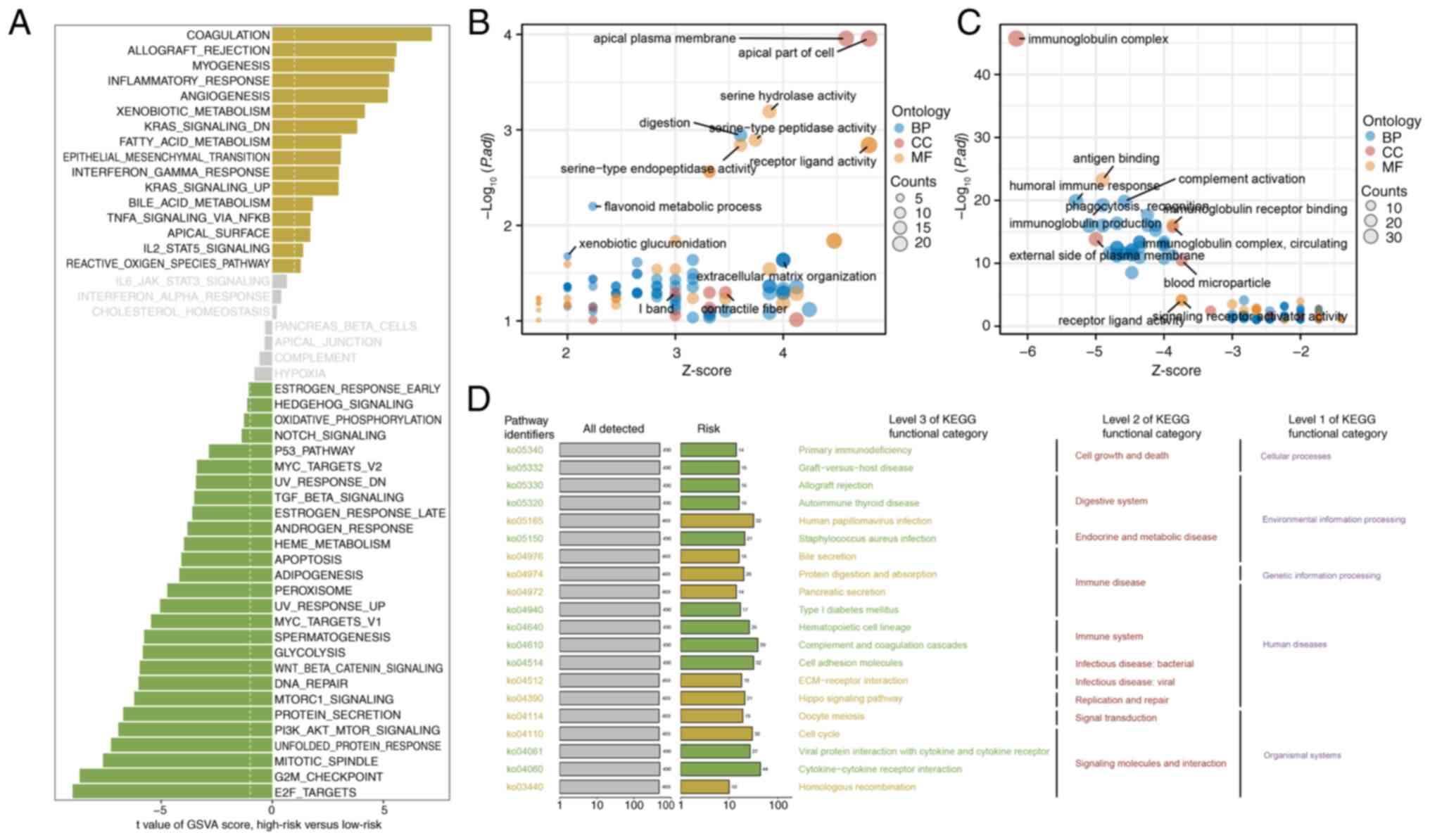

Differential pathway and functional

enrichment between the two risk groups

GSVA of the hallmark gene sets revealed distinct

differences in pathway activation between the two risk groups. The

high-risk group exhibited upregulation of pathways associated with

coagulation, allograft rejection and myogenesis, thus suggesting an

active inflammatory and tissue remodeling environment. By contrast,

the low-risk group exhibited increased activity in pathways

involved in cell cycle regulation, including ‘E2F_TARGETS’,

‘G2M_CHECKPOINT’ and ‘MITOTIC_SPINDLE’, thereby indicating

increased cell proliferation and division (Fig. 4A). GO enrichment analysis further

highlighted functional differences between the groups. The

high-risk group was significantly enriched for pathways associated

with cellular polarity and membrane organization, including the

‘apical plasma membrane’ and ‘apical part of the cell’ (Fig. 4B). Conversely, the low-risk group

was enriched in immune-related pathways, particularly those

associated with immunoglobulin antigen binding, thus reflecting an

active immune response (Fig. 4C).

KEGG pathway analysis also revealed several signaling pathways,

such as ‘Primary immunodeficiency’, ‘Graft-versus-host disease’ and

‘Hippo signaling pathway’, that were differentially enriched

between the two risk groups. The KEGG pathways with similar

biological functions were further categorized to highlight shared

themes across the risk groups (Fig.

4D).

Immunotherapy prediction analysis

based on the TIDE and Submap algorithms

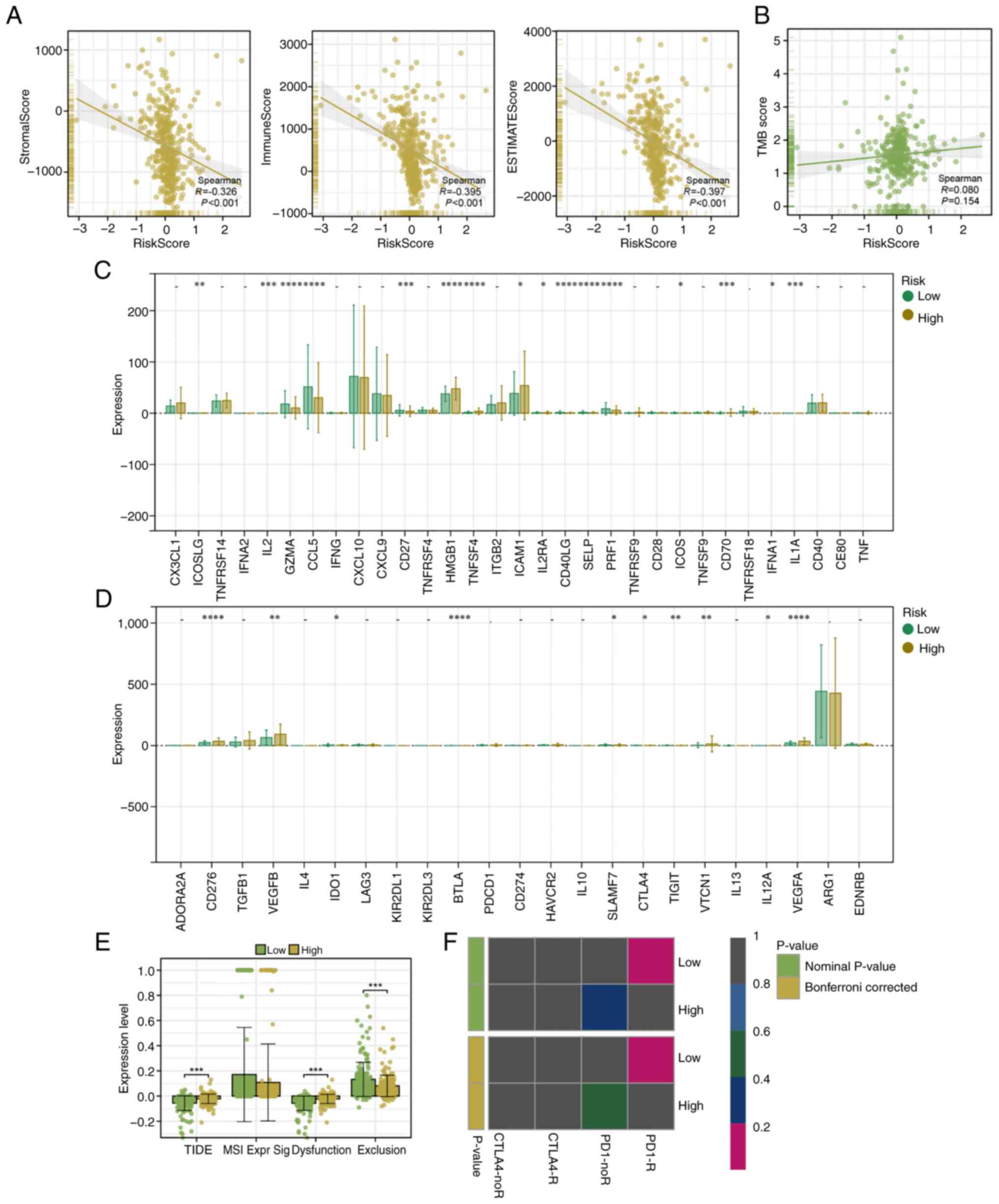

A strong negative correlation was observed between

the risk score and all three ESTIMATE scores (immune, stromal and

overall ESTIMATE scores), thereby indicating that higher scores

were associated with lower levels of immune and stromal cell

infiltration (Fig. 5A). By

contrast, no significant correlation was observed between the risk

score and the TMB, thereby suggesting that the TMB is not a major

factor influencing risk stratification in the present cohort

(Fig. 5B). Subsequently,

differential expression analysis of common inhibitory immune

checkpoint genes was performed. The results revealed that most

inhibitory checkpoint genes (including IL2, CD40 ligand and CD70)

were significantly differentially expressed, with higher expression

levels being observed in the high-risk group (Fig. 5C). Conversely, the expression of

stimulatory immune checkpoint genes did not significantly differ

between the two groups (Fig. 5D).

TIDE analysis revealed that low-risk patients exhibited

significantly lower TIDE and dysfunction scores, thus indicating a

potentially stronger immune response and a lower risk of immune

escape. The exclusion score of low-risk patients was significantly

higher, which was inconsistent with the overall prediction result.

This may be due to reasons such as sample differences. Due to

sample differences and other reasons, dysfunction and exclusion

alone may not be able to make good predictions. Therefore, the TIDE

total score, which combined the scores of dysfunction and

exclusion, was usually adopted as the final prediction result of

the TIDE analysis. (Fig. 5E).

Finally, Submap analysis revealed that patients in the low-risk

group were more likely to respond favorably to ICB therapy, thereby

further suggesting that the low-risk group demonstrates greater

potential for immunotherapy responsiveness (Fig. 5F).

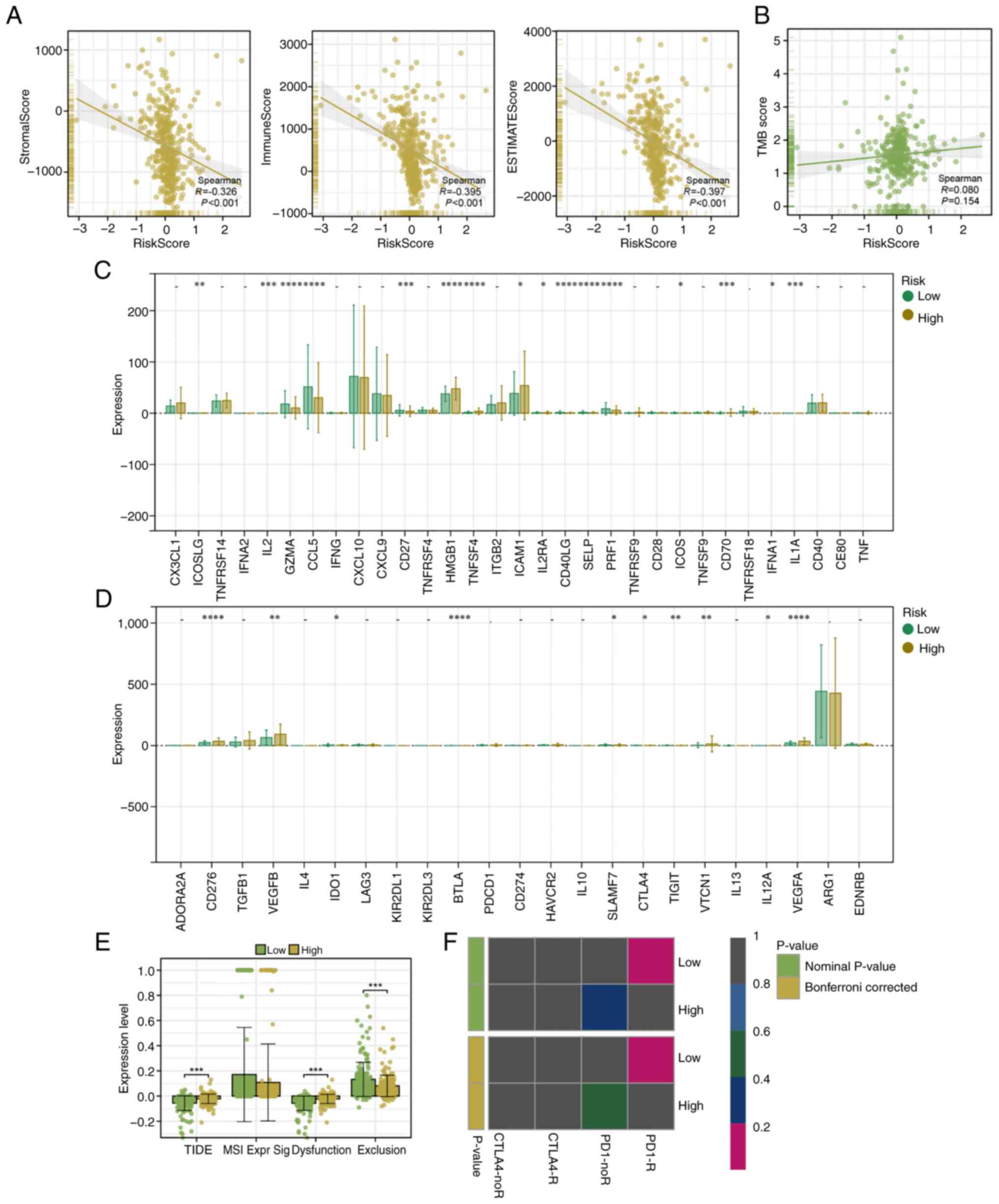

| Figure 5.Immune infiltration, TMB, immune

checkpoint expression and immunotherapy response in two risk

groups. (A) Correlation between the prognostic risk score and the

immune, stromal and ESTIMATE scores, calculated using the ESTIMATE

algorithm. (B) Correlation analysis between the risk score and TMB

showed no significant association. (C) Differential expression

analysis of inhibitory immune checkpoint genes revealed significant

differences between two risk groups. (D) Differential expression of

stimulatory immune checkpoint genes showed no significant

differences between the two groups. (E) TIDE analysis demonstrated

that low-risk patients had significantly lower TIDE scores,

suggesting they have an improved immune response and a reduced

potential for immune escape. (F) SubMap analysis predicted that

low-risk patients are more likely to respond to immune checkpoint

blockade therapy, highlighting their greater potential for

benefiting from immunotherapy. PD1-R indicates a response to PD1

treatment, while PD1-noR indicates no response to PD1 treatment.

CTLA4-R indicates a response to CTLA4 treatment, while CTLA4-noR

indicates no response to CTLA4 treatment. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; t-test based P-value. TMB, tumor

mutational burden; TIDE, Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion;

PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

associated protein 4. |

Expression and ligand-receptor

interactions of KLRB1 in single-cell datasets

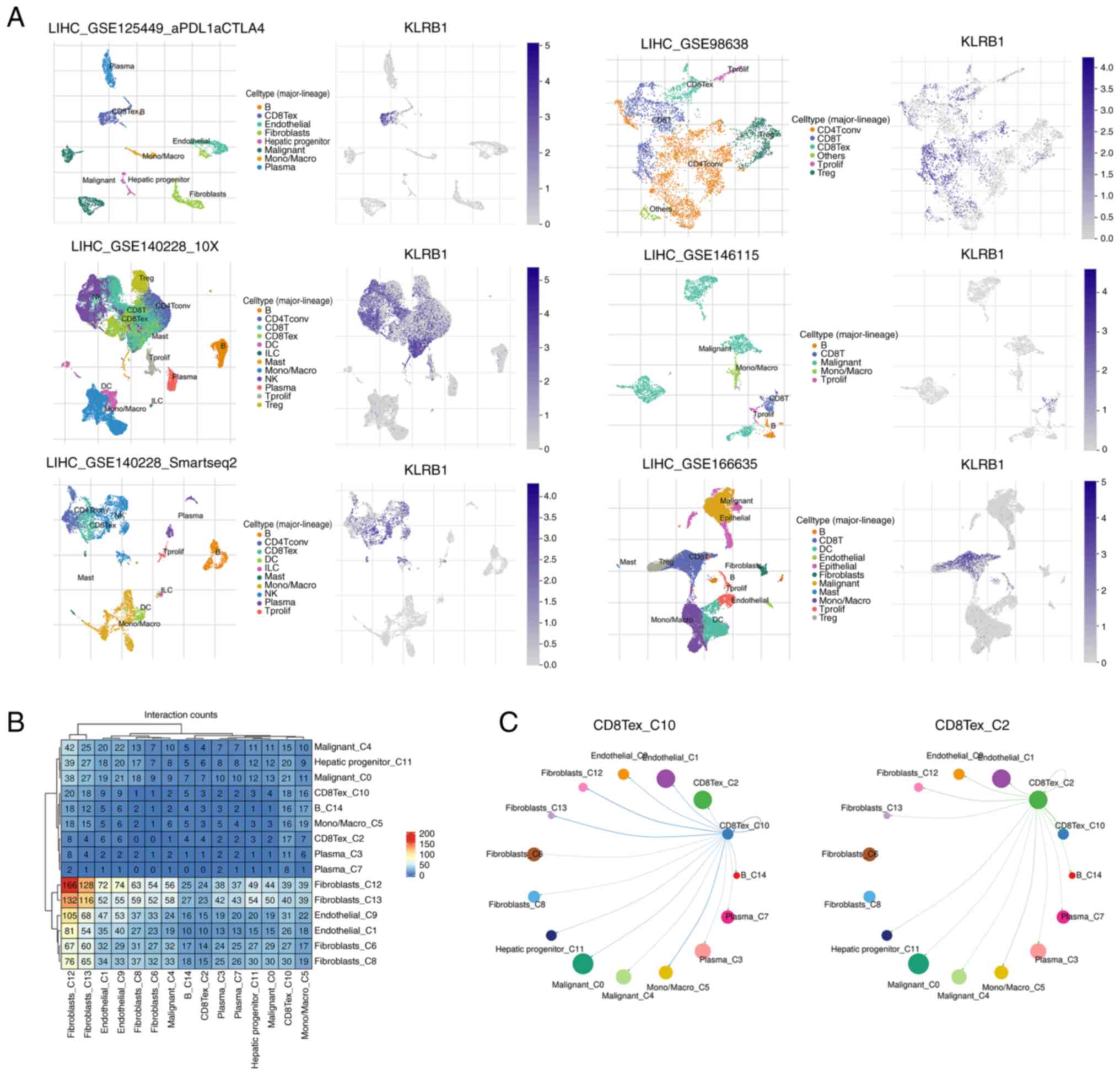

To understand the role of KLRB1 in immune cell

populations, its expression was analyzed in six distinct

single-cell datasets from the TISCH2 database. KLRB1 was observed

to be predominantly expressed in CD8+ T cells,

CD8+ Tex and NK cells, thus indicating its potential

involvement in immune regulation and response within these cell

types (Fig. 6A). The heatmap

displays strong ligand-receptor interactions between various immune

cell types, with notable interaction intensities being observed

between CD8+ T cells and other immune populations

(Fig. 6B). Finally, the network

diagram depicts the dynamic interactions between CD8+ T

cells and surrounding cell populations, thus highlighting the

strength and activity of these interactions. The analysis

demonstrated that CD8+ T cells exhibit significant

signaling crosstalk with other immune cell populations (Fig. 6C).

Expression and prognostic importance

of KLRB1

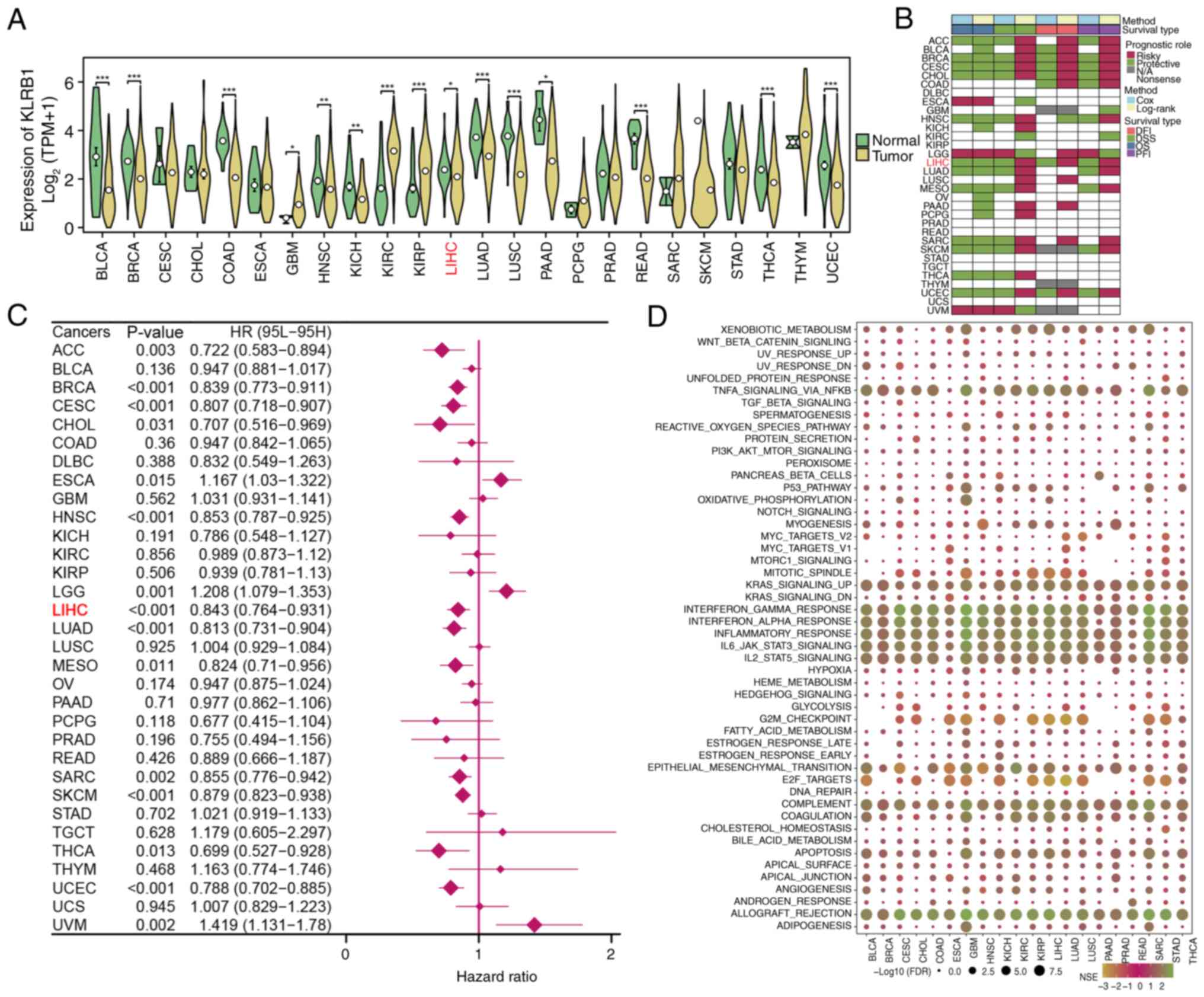

KLRB1 expression was first assessed in multiple

cancer types using TCGA pan-cancer data. KLRB1 was observed to be

significantly differentially expressed in a majority of cancer

types, including LIHC, thereby highlighting its relevance in tumor

biology (Fig. 7A). Prognostic

analysis revealed that KLRB1 expression was associated with

favorable outcomes (including DFI, DSS, OS and PFI) in most cancer

types (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, high

expression of KLRB1 was found to be closely related to poor OS

(Fig. 7C). The LIHC samples were

then stratified into high- and low-KLRB1 expression groups. GSEA of

these groups revealed significant enrichment of specific biological

pathways such as wnt-β-catenin signaling, TGF-β signaling and

PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in both the high- and low-expression

groups, thus suggesting that KLRB1 may serve a key role in

regulating various tumor-related processes (Fig. 7D).

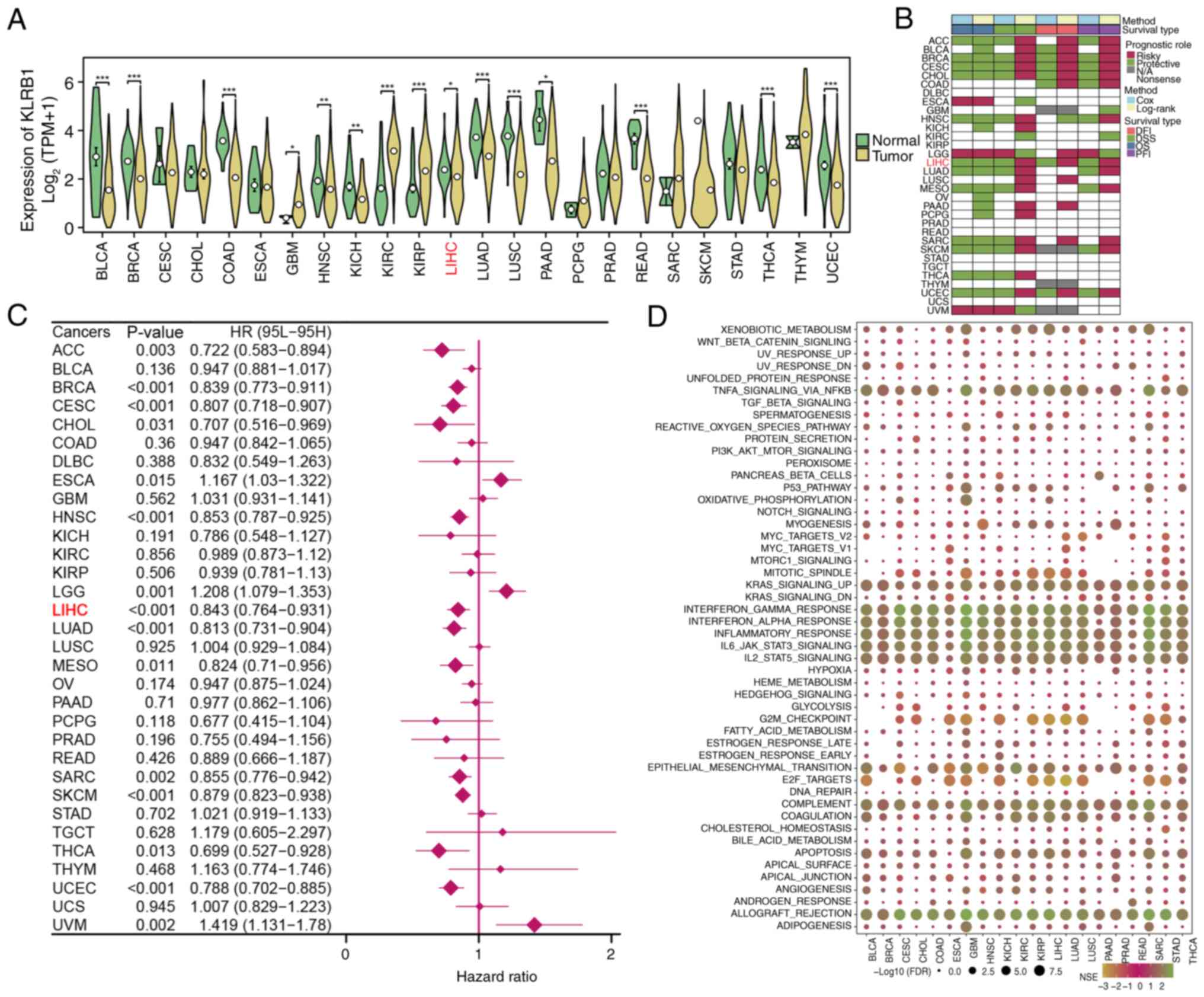

| Figure 7.Pan-cancer analysis of KLRB1

expression and prognostic impact. (A) Expression of KLRB1 across

multiple cancer types in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Significant

differences in KLRB1 expression were observed in several cancer

types, including LIHC. (B) Prognostic analysis of KLRB1 expression

in pan-cancer datasets, including DFI, DSS, OS and PFI. (C) Forest

plot analysis of OS based on KLRB1 expression in pan-cancer. (D)

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis revealed significant biological

pathways enriched in both high- and low-expression groups,

suggesting that KLRB1 may regulate important tumor-related

processes. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; t-test based

P-value. KLRB1, killer cell lectin like receptor B1; LIHC, liver

hepatocellular carcinoma; DFI, disease-free interval; DSS,

disease-specific survival; OS, overall survival; PFI, platinum-free

interval; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment

score; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder cancer; BRCA,

breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma;

CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; DLBC, diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM,

glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma; KICH, kidney chromophobe; KIRC, kidney clear cell

carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LGG, brain

lower grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD,

lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MESO,

mesothelioma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD,

pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and

paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum

adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD,

stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumor; THCA,

thyroid carcinoma; THYM, thymoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrioid

carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma; UVM, uveal melanoma. |

Regulation of tumors by KLRB1 and its

associated secretory factors on macrophage polarization

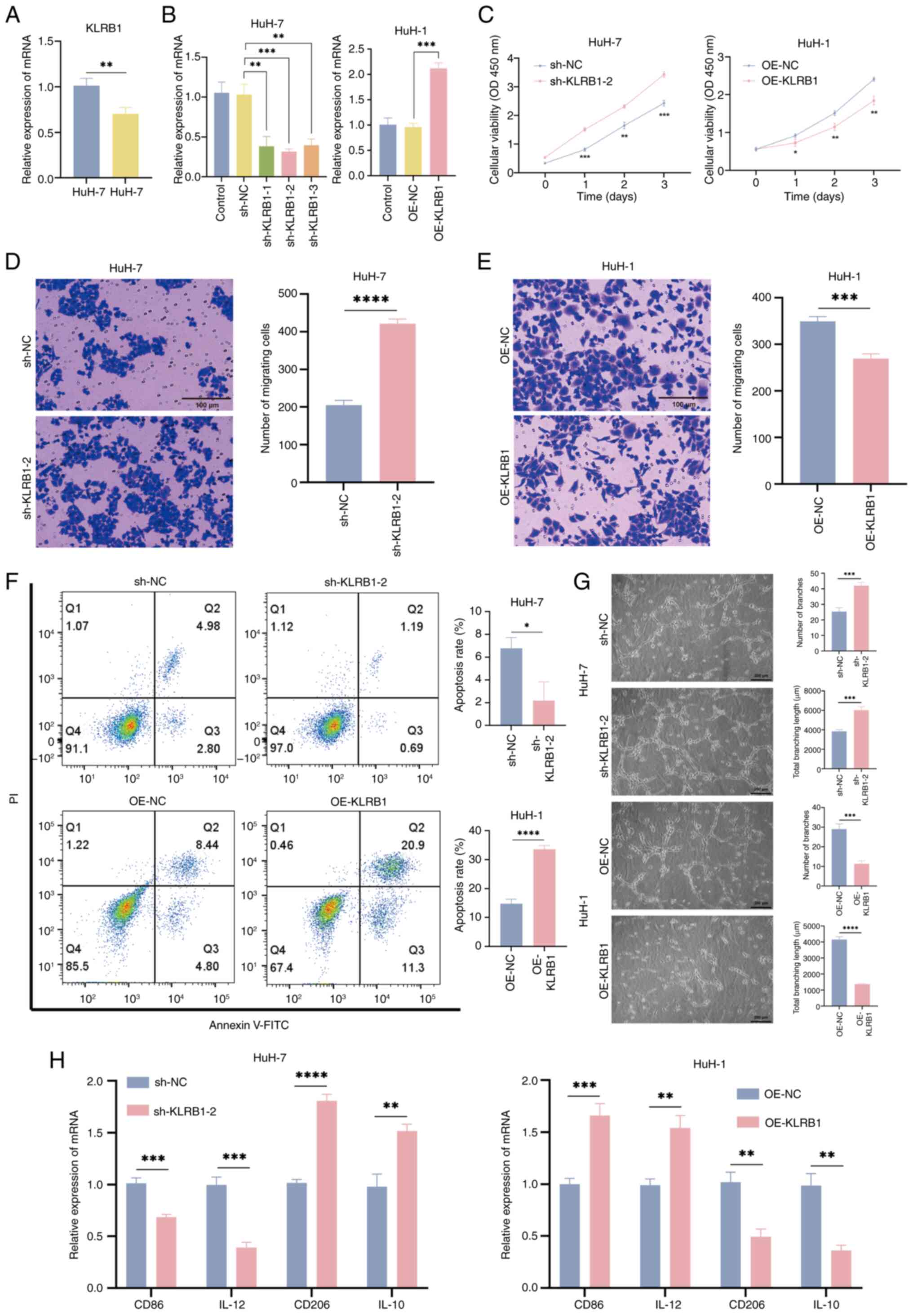

qPCR was used to assess the mRNA levels of KLRB1 in

HuH-7 and HuH-1 cells. The results revealed that KLRB1 expression

was higher in HuH-7 cells compared with HuH-1 cells (Fig. 8A). To knock down KLRB1 in HuH-7

cells (sh-KLRB1-2), shRNA was used and the knockdown cell line was

selected using puromycin. For stable overexpression of KLRB1 in

HuH-1 cells (OE-KLRB1), lentiviral vectors were used, followed by

puromycin selection to generate stable overexpression cell lines

(Fig. 8B). To evaluate the impact

of KLRB1 on tumor cell proliferation, CCK-8 assays were performed.

The results demonstrated that KLRB1 knockdown significantly

increased cell proliferation compared with the control group,

whereas overexpression significantly decreased cell proliferation

(Fig. 8C). Transwell assays were

performed to assess the effect of KLRB1 on cell migration. KLRB1

knockdown enhanced cell migration, whereas KLRB1 overexpression

reduced migration (Fig. 8D and E).

Additionally, the influence of KLRB1 on cell apoptosis was

examined. The flow cytometry results indicated that KLRB1 knockdown

inhibited apoptosis, whereas KLRB1 overexpression promoted

apoptosis (Fig. 8F). And through WB

experiments, it was found that knocking out KLRB1 could

significantly inhibit the expression of Bax and c-caspase-3, and

enhance the expression of Bcl-2 and caspase-3, while overexpression

achieved the opposite result (Fig.

S1). Furthermore, the tube formation assay demonstrated that,

compared with the controls, the culture supernatant from KLRB1

knockdown cells increased the tube forming ability of HUVECs,

whereas the supernatant from KLRB1-overexpressing cells reduced the

tube forming ability of HUVECs (Fig.

8G).

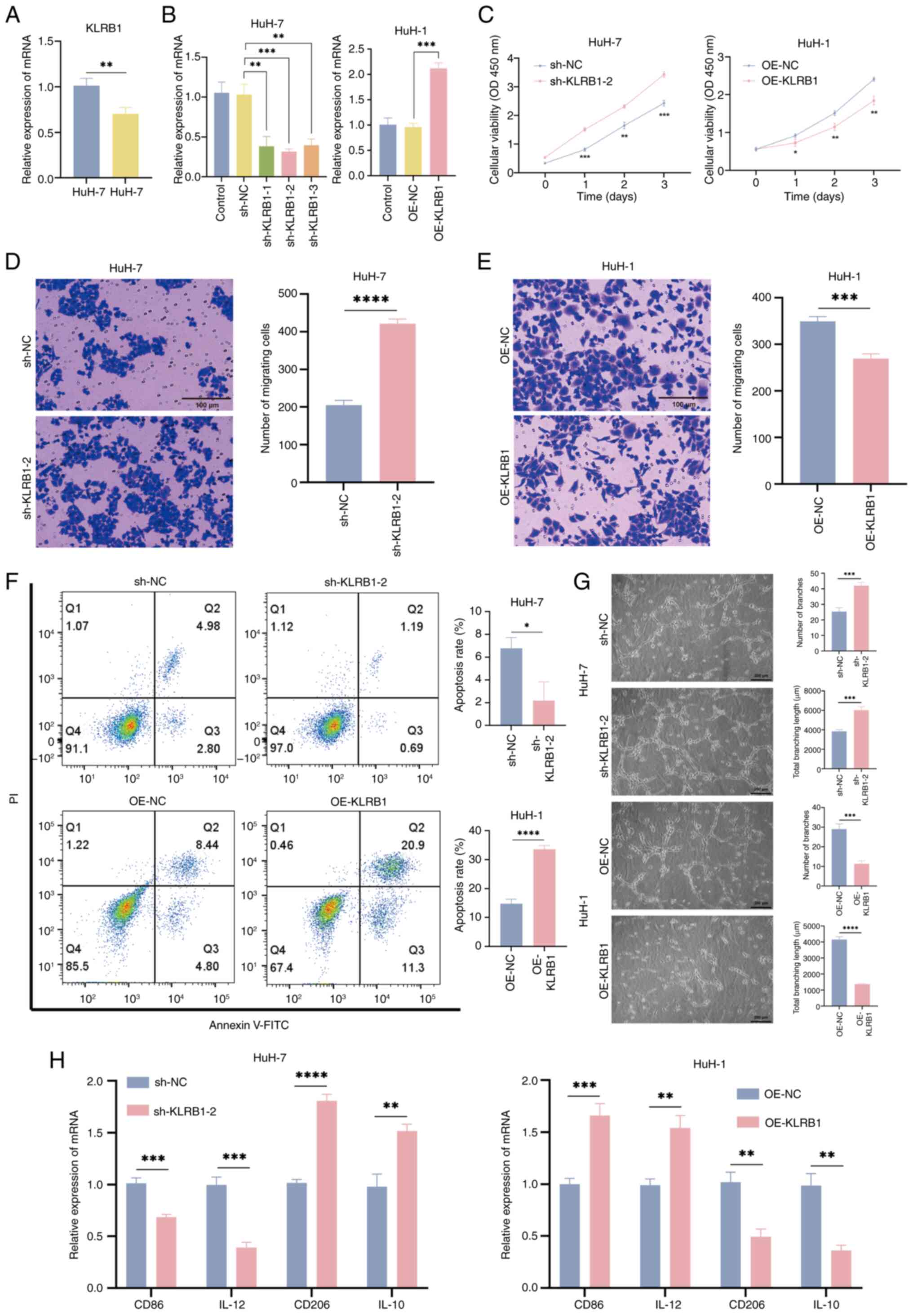

| Figure 8.KLRB1 regulates the activity of LIHC

cells and its influence on macrophages through LIHC cells. (A) qPCR

detection of KLRB1 expression in HuH-7 and HuH-1 cells. (B)

Validation of shRNA knockdown KLRB1 in the HuH-7 cell line and

lentivirus overexpression of KLRB1 in the HuH-1 cell line. (C) Cell

proliferation curve of sh-KLRB1-2 and OE-KLRB1. Cell migration

assay of (D) sh-KLRB1-2 and (E) OE-KLRB1 cells (scale bars, 100

µm). (F) Annexin V-FITC/PI assessed apoptosis in sh-KLRB1-2 and

OE-KLRB1 transfected cells. (G) Tube formation assay of HUVECs

treated with sh-KLRB1-2 and OE-KLRB1 cell conditioned media (scale

bar, 200 µm). (H) qPCR detection of polarization markers in M0 to

M1/M2 cells, treated with sh-KLRB1-2 or OE-KLRB1 cell conditioned

media. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001;

t-test based P-value. LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; PI,

propidium iodide qPCR, quantitative PCR; KLRB1, killer cell lectin

like receptor B1; sh, short hairpin; OE, overexpression; NC,

negative control; OD, optical density. |

To investigate how KLRB1 affects the secretion of

tumor cell-derived factors involved in macrophage polarization,

culture supernatants were collected from KLRB1-knockdown and

KLRB1-overexpressing cells and incubated with THP-1 cell-derived M0

macrophages. The polarization status of M1 and M2 macrophages was

then assessed using qPCR. The results demonstrated that KLRB1

knockdown culture supernatant increased the expression of M2

markers CD206 and IL-10, whereas KLRB1-overexpressing cell culture

supernatant reduced the expression of CD206 and IL-10. By contrast,

the M1 markers CD86 and IL-12 were downregulated following KLRB1

knockdown culture supernatant treatment and upregulated after

overexpression supernatant treatment (Fig. 8H). These findings suggest that KLRB1

may inhibit the polarization of M0 macrophages towards the M2

phenotype. In summary, the upregulation of KLRB1 inhibits the

activity of LIHC cells and facilitates the polarization of

macrophages from the M0 phenotype to the M1 phenotype through

changes in the cell secretome.

Discussion

LIHC is one of the most prevalent and fatal

malignancies worldwide, with a poor prognosis being observed,

primarily due to late-stage diagnoses, high recurrence rates and

resistance to conventional treatments (29). The TME serves a crucial role in the

progression of LIHC, with macrophages (particularly M2 macrophages)

being key contributors to tumor growth, metastasis and immune

evasion (30). M2 macrophages are

characterized by their immunosuppressive properties, which promote

tumor progression through the cells, thereby fostering immune

escape (31). Additionally, M2

macrophages facilitate angiogenesis and ECM remodeling, thus

further enhancing the pro-tumorigenic environment in LIHC (32). Previous advances in bioinformatics

have enabled the integration of large-scale genomic data, thus

allowing for the identification of key molecular signatures

associated with immune infiltration and tumor progression (33,34).

Using techniques such as WGCNA, researchers have identified M2

macrophage-related genes as potential biomarkers for prognosis in

LIHC (35). Given the pivotal role

of M2 macrophages in modulating the TME and influencing immune

responses, a deeper understanding of their gene expression profiles

could offer novel insights into prognostic prediction and

therapeutic strategies for LIHC.

In the present study, M2 macrophage-related genes

that serve significant roles in the prognosis of LIHC were

identified. Using bioinformatics analyses, a prognostic risk model

was constructed based on these genes, which demonstrated promising

predictive power in both the training and external validation

datasets. These findings reinforce the growing body of evidence

suggesting that M2 macrophages are key players in the TME of LIHC

and contribute to tumor progression (9,36).

However, unlike some studies that have established associations

between high M2 macrophage infiltration and poor clinical outcomes,

the present results focused on the identification of gene

expression patterns associated with M2 macrophages that may provide

more reliable prognostic information for patients with LIHC.

Although increased infiltration of M2 macrophages

has been associated with poor prognoses in various cancers, the

present study did not identify direct correlations between M2

macrophage infiltration and various clinical outcomes (such as OS

or progression-free survival) in patients with LIHC. This

discrepancy may be due to the complex nature of the liver TME,

where multiple factors, including hepatic fibrosis, viral

infections and cirrhosis, contribute to disease progression beyond

macrophage infiltration. Therefore, although M2 macrophage-related

genes demonstrate potential as biomarkers for predicting disease

progression, additional studies are necessary to elucidate the

precise mechanisms through which M2 macrophages influence the

clinical course of LIHC.

Notably, the present study suggests that M2

macrophages may influence the efficacy of immunotherapies in LIHC.

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated promising

results in various cancers, their effectiveness in LIHC is often

hindered by the immunosuppressive TME, which is partly shaped by M2

macrophages (37). The analysis

revealed that the preoperative risk model, which was constructed

based on M2 macrophage-related genes, was associated with improved

immune responses and improved outcomes in the low-risk group.

Therefore, the targeting of M2 macrophages or their associated

signaling pathways may provide a promising strategy to increase the

effectiveness of immunotherapy in LIHC, particularly in low-risk

patients who are identified using this model.

Although M2 macrophages serve a critical role in the

TME and have been associated with poor prognoses in various

cancers, the present study identified KLRB1 as an important factor

in LIHC. KLRB1 is primarily expressed on NK cells and certain

T-cell subsets and has been implicated in immune regulation and

tumor immune surveillance (38). In

LIHC, KLRB1 may influence the tumor immune landscape by modulating

immune cell interactions, thereby potentially affecting tumor

progression and patient outcomes. The findings suggest that KLRB1

expression may serve a protective role in LIHC, as higher levels of

this gene were observed to be associated with improved survival

outcomes. This result indicates the involvement of KLRB1 in

promoting antitumor immune responses. However, the precise

mechanisms through which KLRB1 modulates tumor progression and

immune evasion in LIHC remain to be fully elucidated. Based on the

present research findings, it may be speculated that KLRB1 may

promote the progression of LIHC disease by regulating the polarity

transformation of macrophages. Therefore, the targeting of KLRB1 or

its associated signaling pathways may represent a promising

therapeutic approach to improve patient prognosis and enhance the

efficacy of immunotherapies in LIHC.

KLRB1 serves a crucial role in tumor regulation,

with previous studies involving LIHC and lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

highlighting its complex dual function. The expression levels and

functions of KLRB1 vary markedly across different tumor types. For

instance, in breast cancer and LUAD, low expression of KLRB1 is

typically associated with poor prognosis, and its functions involve

immune regulation, cell proliferation and migration (39). Similarly, in other cancer types, low

expression of KLRB1 is generally associated with poor survival

outcomes. In conclusion, the present study provides strong evidence

that KLRB1 serves a multifaceted role in regulating both tumor cell

behavior and macrophage polarization. The upregulation of KLRB1

appears to inhibit the proliferation and migration of LIHC cells,

promote apoptosis and facilitate the polarization of macrophages

towards the M1 phenotype. As KLRB1 is a membrane protein, the

conditioned media may also contain exosomes or microvesicles

secreted by the KLRB1 knockdown or OE cells. These vesicles can

carry not only proteins and lipids but also mRNA and miRNA that can

have an impact on recipient cells, including macrophages. For

instance, specific miRNAs may influence macrophage gene expression

related to polarization. Furthermore, changes in KLRB1 expression

can alter the metabolic state of the transfected cells, which in

turn could affect the composition of metabolites and extracellular

vesicles released into the conditioned media. This is typically

more effective in combating tumors. These findings highlight the

potential of KLRB1 as a therapeutic target in LIHC and emphasize

the importance of understanding the complex interactions between

immune cells and cancer cells in the development of novel cancer

treatments.

Despite the promising results associated with the M2

macrophage-related prognostic signature, several limitations must

be acknowledged in the current study. Firstly, the research

primarily relied on data retrieved from public databases, which

often contain relatively small sample sizes and may not be promptly

updated. In addition, the focal point of the investigation involved

M2 macrophage-related genes; however, the specific molecular

mechanisms by which these genes regulate the progression of LIHC

necessitate further in-depth explorations. Consequently, the

interpretation of the results presented requires additional

validation and enhancement. Furthermore, the prognostic signature

was predominantly verified using public datasets, which may harbor

intrinsic biases and do not provide clinical validation within

independent, real-world patient cohorts. Secondly, although

analyses of immune-cell infiltration and predictions regarding

immunotherapy offer valuable insights, the exact mechanisms linking

M2 macrophage-related genes to immune responses in LIHC remain

inadequately understood and warrant additional experimental

investigations. Furthermore, the present study suggested that KLRB1

may serve a role in modulating immune responses and facilitating

the progression of LIHC. A thorough review of the literature

regarding KLRB1 indicates that this gene represents a novel

therapeutic target; however, the molecular mechanisms through which

KLRB1 regulates LIHC remain largely unexplored and should be

further investigated. Additionally, the present research did not

evaluate potential interactions between other key genes and

molecular pathways that could influence the progression of LIHC,

thereby highlighting the need for further explorations in this

area. Finally, although the prognostic signature demonstrates

promise in guiding immunotherapy strategies, its clinical

applicability is constrained by the absence of prospective clinical

trials to validate its predictive power. Future studies should

focus on validating the prognostic signature within larger, more

diverse patient populations and elucidating the mechanistic roles

of M2 macrophages in the context of LIHC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Evaluation of the Efficacy

of Liver-Coursing Spleen-Rectifying Decoction in Treating

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and its Effects on Intestinal

Flora and Serum LPS of Patients (grant no. S202406060003).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LC was involved in the study conception and design

and reviewed the manuscript. AW, XL and ZW performed the literature

search, performed experiments, acquired and analyzed data,

performed the statistical analysis and wrote and reviewed the

manuscript. LC serves as a guarantor for the integrity of the

entire study. LC, AW, XL and ZW confirm the authenticity of the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

LIHC

|

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

NK

|

natural killer

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

ICGC

|

International Cancer Genome

Consortium

|

|

WGCNA

|

weighted gene co-expression network

analysis

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

scRNA-seq

|

single-cell RNA sequencing

|

|

Tex

|

CD8+ exhausted T cells

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

PI

|

propidium iodide

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription quantitative

PCR

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zheng Z, Mei J, Guan R, Zhang J, Xiong X,

Gan J, Li S and Guo R: A novel liver-function-indicators-based

prognosis signature for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

treated with anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 73:1582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Antonius Y, Kharisma VD, Widyananda MH,

Ansori ANM, Trinugroho JP, Ullah Md E, Naw SW, Jakhmola V and

Wahjudi M: Prediction of aflatoxin-B1 (AFB1) molecular mechanism

network and interaction to oncoproteins growth factor in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 16:1844–1854.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Jia G, He P, Dai T, Goh D, Wang J, Sun M,

Wee F, Li F, Lim JCT, Hao S, et al: Spatial immune scoring system

predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Nature.

640:1031–1041. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu B and Ma W: Biomarker discovery in

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for personalized treatment and

enhanced prognosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 79:29–38. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li M, Yang Y, Xiong L, Jiang P, Wang J and

Li C: Metabolism, metabolites, and macrophages in cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brockmann L, Tran A, Huang Y, Edwards M,

Ronda C, Wang HH and Ivanov II: Intestinal microbiota-specific Th17

cells possess regulatory properties and suppress effector T cells

via c-MAF and IL-10. Immunity. 56:2719–2735.e7. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pascual-García M, Bonfill-Teixidor E,

Planas-Rigol E, Rubio-Perez C, Iurlaro R, Arias A, Cuartas I,

Sala-Hojman A, Escudero L, Martínez-Ricarte F, et al: LIF regulates

CXCL9 in tumor-associated macrophages and prevents CD8+ T cell

tumor-infiltration impairing anti-PD1 therapy. Nat Commun.

10:24162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Han S, Bao X, Zou Y, Wang L, Li Y, Yang L,

Liao A, Zhang X, Jiang X, Liang D, et al: d-lactate modulates M2

tumor-associated macrophages and remodels immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Adv.

9:eadg26972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li D, Zhang T, Guo Y, Bi C, Liu M and Wang

G: Biological impact and therapeutic implication of

tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell

Death Dis. 15:4982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang Y, Han G, Gu J, Chen Z and Wu J:

Role of tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma:

impact, mechanism, and therapy. Front Immunol. 15:14298122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sun Y, Zhao M, Cheng L, He X, Shen S, Lv

J, Zhang J, Shao Q, Yin W, Zhao F, et al: Reduction of alternative

polarization of macrophages by short-term activated hepatic

stellate cell-derived small extracellular vesicles. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 44:1172025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Du Y, Wu S, Xi S, Xu W, Sun L, Yan J, Gao

H, Wang Y, Zheng J, Wang F, et al: ASH1L in hepatoma cells and

hepatic stellate cells promotes fibrosis-associated hepatocellular

carcinoma by modulating tumor-associated macrophages. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 11:e24047562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jeong JM, Choi SE, Shim YR, Kim HH, Lee

YS, Yang K, Kim K, Kim MJ, Chung KPS, Kim SH, et al: CX 3 CR1 +

macrophages interact with HSCs to promote HCC through CD8 + T-cell

suppression. Hepatology. 82:655–668. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cai J, Song L, Zhang F, Wu S, Zhu G, Zhang

P, Chen S, Du J, Wang B, Cai Y, et al: Targeting SRSF10 might

inhibit M2 macrophage polarization and potentiate anti-PD-1 therapy

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond). 44:1231–1260.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Aran D, Hu Z and Butte AJ: xCell:

Digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape.

Genome Biol. 18:2202017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mellman I, Chen DS, Powles T and Turley

SJ: The cancer-immunity cycle: Indication, genotype, and

immunotype. Immunity. 56:2188–2205. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Finotello F, Mayer C, Plattner C,

Laschober G, Rieder D, Hackl H, Krogsdam A, Loncova Z, Posch W,

Wilflingseder D, et al: Molecular and pharmacological modulators of

the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq

data. Genome Med. 11:342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Racle J, de Jonge K, Baumgaertner P,

Speiser DE and Gfeller D: Simultaneous enumeration of cancer and

immune cell types from bulk tumor gene expression data. Elife.

6:e264762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L, Buttard B,

Elarouci N, Petitprez F, Selves J, Laurent-Puig P, Sautès-Fridman

C, Fridman WH and de Reyniès A: Estimating the population abundance

of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using

gene expression. Genome Biol. 17:2182016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Langfelder P and Horvath S: WGCNA: An R

package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 9:5592008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney J:

GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data.

BMC Bioinformatics. 14:72013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang G, Liu T and He WT: Visualization

analysis of research hotspots and trends on gastrointestinal tumor

organoids. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 16:2826–2841. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X,

Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, et al: Signatures of T cell dysfunction

and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med.

24:1550–1558. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kalhor K, Chen CJ, Lee HS, Cai M, Nafisi

M, Que R, Palmer CR, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Li X, et al: Mapping human

tissues with highly multiplexed RNA in situ hybridization. Nat

Commun. 15:25112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Han Y, Wang Y, Dong X, Sun D, Liu Z, Yue

J, Wang H, Li T and Wang C: TISCH2: expanded datasets and new tools

for single-cell transcriptome analyses of the tumor

microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D1425–D1431. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang X, Yang C, Zhang S, Geng H, Zhu AX,

Bernards R, Qin W, Fan J, Wang C and Gao Q: Precision treatment in

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 42:180–197. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ruf B, Bruhns M, Babaei S, Kedei N, Ma L,

Revsine M, Benmebarek MR, Ma C, Heinrich B, Subramanyam V, et al:

Tumor-associated macrophages trigger MAIT cell dysfunction at the

HCC invasive margin. Cell. 186:3686–3705.e32. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jin R, Neufeld L and McGaha TL: Linking

macrophage metabolism to function in the tumor microenvironment.

Nat Cancer. 6:239–252. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zeng W, Li F, Jin S, Ho PC, Liu PS and Xie

X: Functional polarization of tumor-associated macrophages dictated

by metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2452023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang D, Zhao K, Han T, Zhang X, Xu X, Liu

Z, Ren X, Zhang X, Lu Z and Qin C: Bisphenol A promote the cell

proliferation and invasion ability of prostate cancer cells via

regulating the androgen receptor. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

269:1158182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cai J, Chen T, Jiang Z, Yan J, Ye Z, Ruan

Y, Tao L, Shen Z, Liang X, Wang Y, et al: Bulk and single-cell

transcriptome profiling reveal extracellular matrix mechanical

regulation of lipid metabolism reprograming through YAP/TEAD4/ACADL

axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 19:2114–2131.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Qu X, Zhao X, Lin K, Wang N, Li X, Li S,

Zhang L and Shi Y: M2-like tumor-associated macrophage-related

biomarkers to construct a novel prognostic signature, reveal the

immune landscape, and screen drugs in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Front Immunol. 13:9940192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen S, Zhang P, Zhu G, Wang B, Cai J,

Song L, Wan J, Yang Y, Du J, Cai Y, et al: Targeting GSDME-mediated

macrophage polarization for enhanced antitumor immunity in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Immunol. 21:1505–1521. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Vizcaino Castro A, Daemen T and Oyarce C:

Strategies to reprogram anti-inflammatory macrophages towards

pro-inflammatory macrophages to support cancer immunotherapies.

Immunol Lett. 267:1068642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mace EM: Human natural killer cells: Form,

function, and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 151:371–385.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Huang G, Xiao S, Jiang Z, Zhou X, Chen L,

Long L, Zhang S, Xu K, Chen J and Jiang B: Machine learning

immune-related gene based on KLRB1 model for predicting the

prognosis and immune cell infiltration of breast cancer. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14:11857992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|