Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common

malignancies. According to the 2022 cancer report in China, CRC

remains the second most prevalent cancer and ranks fourth in

cancer-associated mortalities (1).

Despite advances in diagnostic technologies and the ongoing

development of therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy and

targeted therapy, the prognosis for metastatic CRC (mCRC) remains

poor with a 5-year survival rate of <15% (2). Due to the limited options for

later-line treatment and the deterioration of the physical

condition of patients following multiple treatment lines,

identifying effective, low-toxicity therapy for subsequent lines

remains a major focus of current research. At present, the standard

later-line treatments recommended by the Chinese Society of

Clinical Oncology Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines include

fruquintinib, regorafenib and TAS-102 (3).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as

programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors, have recently transformed the

landscape of clinical oncology. The KEYNOTE-016 study demonstrated

that pembrolizumab provides durable antitumor activity and fewer

treatment-related adverse events (AEs) supporting it as an

efficacious first-line therapy in patients with microsatellite

instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair-deficient mCRC

(4). However, ~95% of patients with

mCRC are classified as microsatellite-stable (MSS)/mismatch repair

proficient (pMMR), characterized by a tumor microenvironment with

limited immune cell infiltration, which results in suboptimal

efficacy of immunotherapy monotherapy (5–8).

Therefore, improving survival outcomes in the MSS/pMMR population

remains a notable challenge in the management of mCRC.

At present, the primary challenge in treatment is

how to modify therapeutic strategies to augment the sensitivity of

patients with MSS-type mCRC to immunotherapy, thereby improving

prognosis. Emerging evidence demonstrates that the combination of

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors with

ICIs has a synergistic antitumor effect (9). Fruquintinib, a highly selective

tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) developed independently in China,

specifically targets VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3, effectively

suppressing tumor angiogenesis (10). The global, multicenter FRESCO-2

trial demonstrated that fruquintinib significantly improved

outcomes compared with the placebo, with a median progression-free

survival (PFS) of 3.7 months and a median overall survival (OS) of

7.4 months (11). Based on these

findings, fruquintinib was approved by the US. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) for the treatment of recurrent mCRC on

November 8, 2023 (12).

Moreover, the combination of fruquintinib and ICIs

has shown promising therapeutic potential for CRC in both

preclinical and clinical studies. Li et al (13) demonstrated that the combination of

fruquintinib and sintilimab more effectively inhibited the growth

of colorectal tumors and significantly extended survival compared

with monotherapy with either agent in a mouse xenograft model.

Mechanistically, this combination therapy targeted tumor

angiogenesis and modulated the tumor immune microenvironment,

enhancing T-cell infiltration and thereby suppressing tumor

progression. The findings of a study reported by Li et al

(13) suggest a synergistic effect

between TKI and PD-1 inhibitors, providing a solid theoretical

foundation for the treatment of CRC. Clinically, Guo et al

(14) reported a median OS of 20.0

months and a median PFS of 6.9 months in patients with MSS/pMMR

mCRC receiving fruquintinib plus sintilimab, significantly

extending OS. Further evidence from a propensity score-matched

retrospective study presented at the 2024 American Society of

Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancer Symposium (15) confirmed that fruquintinib plus a

PD-1 inhibitor significantly improved PFS in patients with MSS/pMMR

mCRC. Similarly, several small-scale retrospective studies have

demonstrated that combining fruquintinib with other ICIs yields

superior efficacy compared with fruquintinib monotherapy in

patients with MSS/pMMR mCRC, with manageable AEs, indicating

promising clinical potential (16,17).

However, existing studies have notable limitations.

Most trials focus on the combined effects of a single PD-1

inhibitor and fruquintinib. There is a lack of direct comparison

between fruquintinib combined with different ICIs and an

introduction to the side effects of the combination regimens. The

present study systematically analyzed the efficacy and safety of

different ICIs combined with fruquintinib in patients with MSS/pMMR

mCRC. In contrast to the traditional fixed-dose model, the present

study reviewed the drug dose intensity, administration time and

sequence in the real world, which provided specific guidance for

the optimization of the future administration regimen of

immunotherapy combined with fruquintinib. At the same time, the

present study also explored a more efficient and low-toxicity

combination therapy model and further precisely selected the

beneficiary population. The present study supports important

clinical needs and scientific value.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

The present retrospective study analyzed the medical

data of patients with MSS/pMMR mCRC between January 2022 and

December 2023 at the Jiangsu Cancer Hospital (Nanjing, China).

Patients who were aged 18–75 years with histopathologically or

cytologically confirmed CRC and MSS/pMMR were eligible for the

study. Patients were required to have failed at least two prior

lines of treatment (all patients had received standard first- and

second-line chemotherapy) and to have received fruquintinib plus

PD-1 inhibitors (PD-1 inhibitor combination group) or programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors (PD-L1 inhibitor combination

group). Patients also had to have radiologically confirmed

metastases with at least one radiological-target lesion, a life

expectancy of ≥3 months and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

(ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 (18). Patients were excluded if they had

received a live vaccine within 28 days before treatment, were

allergic to fruquintinib or ICIs, had active hepatitis B or C, HIV

infection, active tuberculosis, had a history of active autoimmune

disease, had severe liver or kidney dysfunction or other serious

underlying conditions, and had a history of or concurrent untreated

malignancy.

The present study was conducted in compliance with

Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki

(2013 version) and approved by the ethics committee of the Jiangsu

Cancer Hospital (grant no. KY-2024-071). The requirement for

informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of

the present study.

Treatments

Regarding the initial dose of fruquintinib, the

fruquintinib dose in the FRESCO-2 study (11) was used, which is 5 mg daily q28 with

a 1-week break from days 22–28. However, most patients cannot

tolerate a 5 mg daily dose. Therefore, all patients received oral

fruquintinib once daily, with initial doses of 3, 4 or 5 mg.

Treatment continued for 2 weeks, followed by a 1-week break, with

each cycle lasting 21 days. The actual initial dose was mainly

selected by clinicians after a full assessment in combination with

the physical condition, body surface area, previous chemotherapy

response, and liver and kidney functions of the patient. Regarding

the issue of drug administration time, a Ib/II study conducted by

Guo et al (14) was

referenced; compared with the treatment group taking 3 mg

fruquintinib daily, the group taking 5 mg/day fruquintinib for 2

weeks and then having a 1-week break showed a marked improvement in

efficacy. The present treatment continued for 2 weeks, followed by

a 1-week break, with each cycle lasting 21 days. If the patient

experienced intolerance, the dose could be adjusted and treatment

discontinued if intolerance persisted.

In the PD-1 inhibitor combination group, the PD-1

inhibitors camrelizumab (200 mg), sintilimab (200 mg), tislelizumab

(200 mg), toripalimab (240 mg) or serplulimab (300 mg) were chosen

by the physician based on the condition of the patient, with

intravenous infusion on day 1 of each 21-day cycle. In the PD-L1

inhibitor combination group, envafolimab (200 mg) was administered

by subcutaneous injection on days 1 and 15 of each 28-day cycle.

All ICIs were continued until disease progression or severe

intolerance.

Outcomes and assessment

Tumor responses were evaluated every 2 cycles

through computed tomography (CT) in accordance with the Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines (version 1.1)

(19). The tumor responses

monitored included complete response (CR), partial response (PR),

stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD). Efficacy outcomes

included objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR)

and PFS. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with CR

or PR. The DCR was the proportion of patients who achieved CR, PR

or SD. The DCR time node in the present study was 3 months. The PFS

was calculated as the time from treatment initiation to first

disease progression or death from any cause. All AEs occurring

during the treatment in both groups were collected and evaluated

according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

version 5.0 (20).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

version 22.0 (IBM Corp.) Baseline categorical variables were

compared using the χ2 test. Survival curves were

generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with group differences

assessed by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses

were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to identify

independent prognostic factors. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 78 patients with mCRC were included, with

47 (60.3%) males and 31 (39.7%) females and a median age of 57

years. Subsequently, 63 patients received fruquintinib plus a PD-1

inhibitor (20 sintilimab, 13 tislelizumab, 11 camrelizumab, 9

toripalimab or 10 serplulimab) and 15 received fruquintinib plus a

PD-L1 inhibitor (envafolimab). In the PD-1 inhibitor combination

group, 10, 23 and 30 patients received initial doses of

fruquintinib at 3, 4 and 5 mg, respectively, while in the PD-L1

inhibitor combination group, two, 9 and four patients received

initial doses of 3, 4 and 5 mg, respectively. There were no

significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the

two groups (P>0.05; Table

I).

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the

included patients. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the

included patients.

| Characteristic | PD-1 inhibitor

combination group (n=63) | PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group (n=15) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

| 1.43 | 0.231 |

| Male | 40 (63.5) | 7 (46.7) |

|

|

|

Female | 23 (36.5) | 8 (53.3) |

|

|

| Age |

|

| 2.03 | 0.154 |

|

<60 | 38 (60.3) | 6 (40.0) |

|

|

| ≥60 | 25 (39.7) | 9 (60.0) |

|

|

| ECOG performance

status |

|

| 0.37 | 0.542 |

| 0 | 24 (38.1) | 7 (46.7) |

|

|

| 1 | 39 (61.9) | 8 (53.3) |

|

|

| Degree of

differentiation |

|

| 4.44 | 0.109 |

| High | 2 (3.2) | 3 (20.0) |

|

|

|

Middle | 44 (69.8) | 9 (60.0) |

|

|

| Low | 17 (27.0) | 3 (20.0) |

|

|

| Tumor location |

|

| 0.32 | 0.571 |

| Left | 49 (77.8) | 10 (66.7) |

|

|

|

Right | 14 (22.2) | 5 (33.3) |

|

|

| Number of

metastases |

|

| 0.03 | 0.872 |

|

<3 | 50 (79.4) | 11 (73.3) |

|

|

| ≥3 | 13 (20.6) | 4 (26.7) |

|

|

| Presence of liver

metastases | 37 (58.7) | 8 (53.3) | 0.15 | 0.704 |

| Presence of lung

metastases | 31 (50.8) | 5 (66.7) | 1.23 | 0.268 |

| Number of treatment

lines |

|

| 0.99 | 0.319 |

|

>3 | 19 (30.2) | 2 (13.3) |

|

|

| 3 | 44 (69.8) | 13 (86.7) |

|

|

| Baseline

carcinoembryonic antigen |

|

| 0.56 | 0.452 |

|

<5 | 32 (50.8) | 6 (40.0) |

|

|

| ≥5 | 31 (49.2) | 9 (60.0) |

|

|

| BRAF

status |

|

| 0.53 | 0.872 |

|

Wild-type | 43 (68.3) | 10 (66.7) |

|

|

|

Mutated | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 17 (27.0) | 5 (33.3) |

|

|

| KRAS

status |

|

| 2.64 | 0.267 |

|

Wild-type | 21 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) |

|

|

|

Mutated | 25 (39.7) | 8 (53.3) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 17 (27.0) | 5 (33.3) |

|

|

| Prior antitumor

treatment |

|

|

|

|

| TKI

therapy | 13 (20.6) | 3 (20.0) | 0.003 | 0.956 |

|

Radiotherapy | 20 (31.7) | 8 (53.3) | 2.45 | 0.117 |

|

Surgery | 51 (81.0) | 14 (93.3) | 0.59 | 0.441 |

| Initial dose of

fruquintinib |

|

| 2.90 | 0.234 |

| 3

mg | 10 (15.9) | 2 (13.3) |

|

|

| 4

mg | 23 (36.5) | 9 (60.0) |

|

|

| 5

mg | 30 (47.6) | 4 (26.7) |

|

|

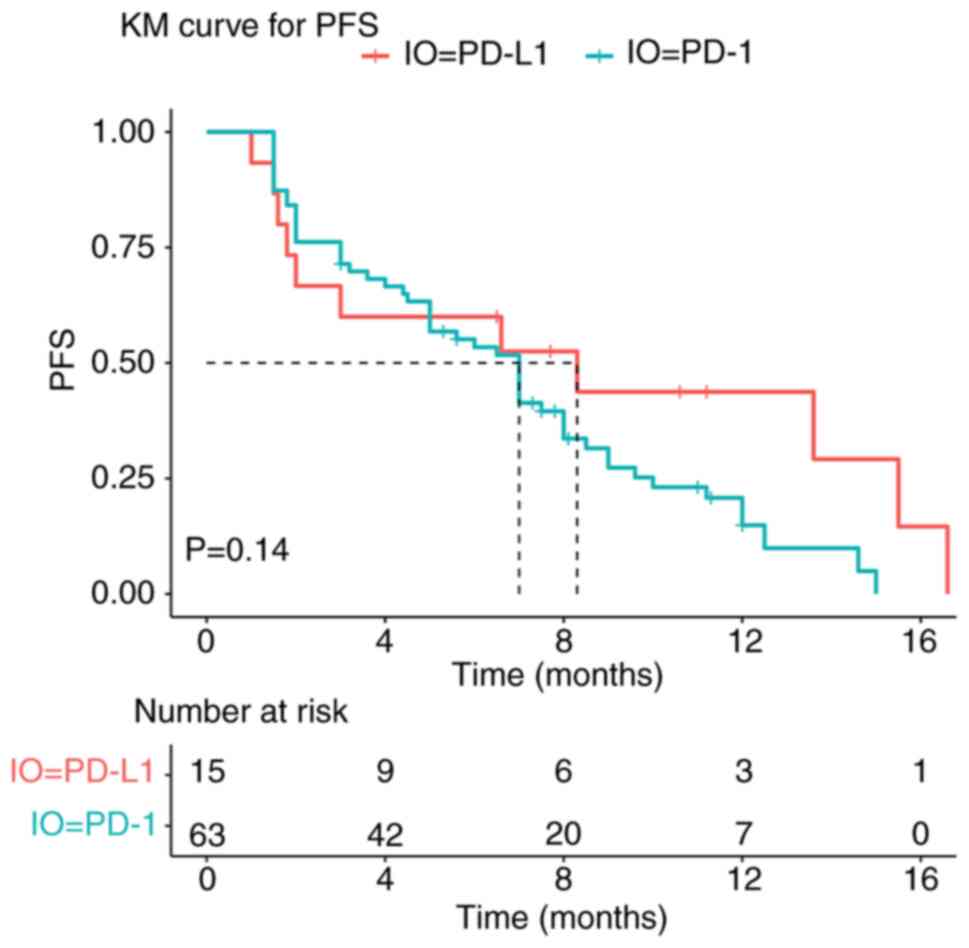

Efficacy

In the PD-1 inhibitor combination group, 5 (7.9%)

patients had a PR and 42 (66.7%) patients had an SD, achieving an

ORR of 7.9% and a DCR of 74.6% (Table

II). In comparison, the PD-L1 inhibitor combination group

included 3 patients (20.0%) with PR and 6 patients (40.0%) with SD,

yielding an ORR of 20.0% and a DCR of 60.0% (Table II). No statistically significant

differences were observed between the PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group in ORR (7.9 vs. 20.0%; P=0.363) or DCR (74.6 vs.

60%; P=0.418). Moreover, there was no significant difference in

median PFS between the two groups (7.0 vs. 8.3 months; P=0.14;

Fig. 1).

| Table II.Efficacy between the PD-1 and PD-L1

inhibitor combination groups. |

Table II.

Efficacy between the PD-1 and PD-L1

inhibitor combination groups.

| Response | PD-1 inhibitor

combination group (n=63) | PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group (n=15) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Objective

response |

|

|

|

|

| CR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | Not applicable | >0.999 |

| PR | 5 (7.9) | 3 (20.0) | 0.83 | 0.363 |

| SD | 42 (66.7) | 6 (40.0) | 3.64 | 0.056 |

| PD | 16 (25.4) | 6 (40.0) | 1.28 | 0.259 |

| ORR | 5 (7.9) | 3 (20.0) | 0.83 | 0.363 |

| DCR | 47 (74.6) | 9 (60.0) | 0.66 | 0.418 |

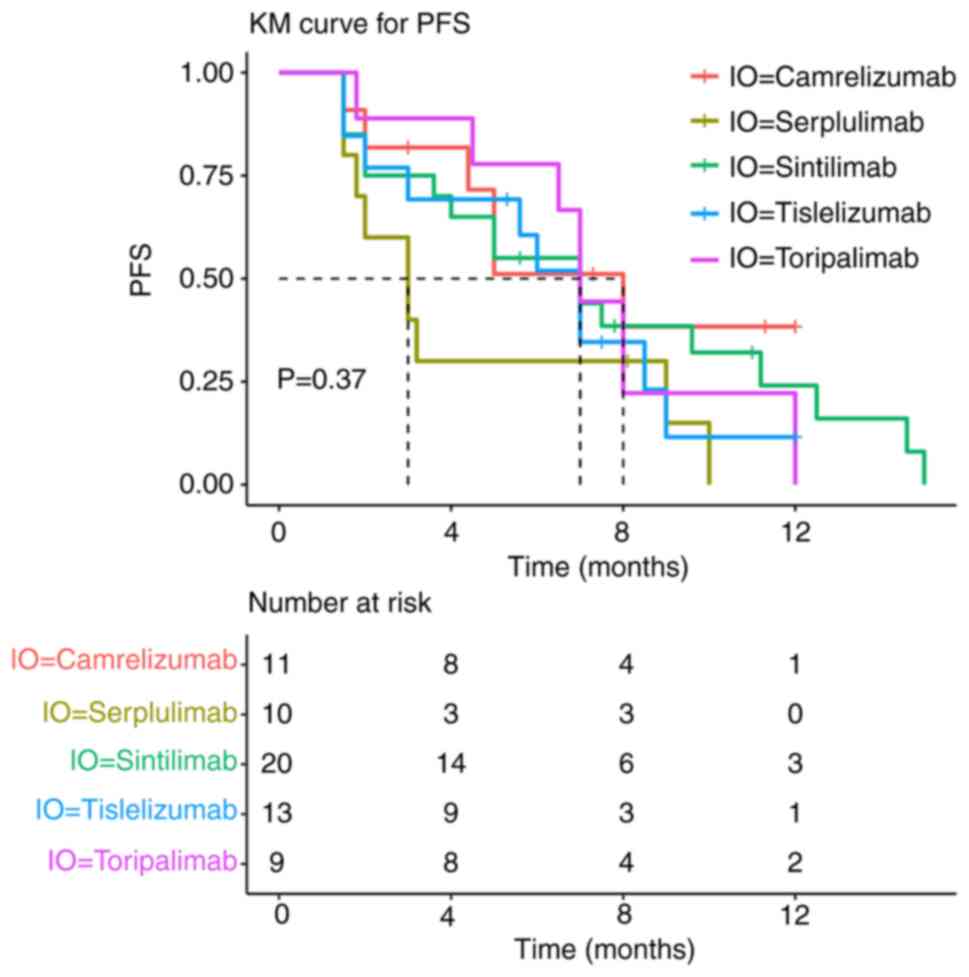

In the PD-1 inhibitor combination group, five PD-1

inhibitors were administered. Subgroup analysis showed no

statistically significant differences in PFS between patients

treated with sintilimab, tislelizumab, camrelizumab, toripalimab or

serplulimab (P=0.37; Fig. 2).

Univariate analysis showed that age, ECOG performance status and

liver metastases were associated with PFS (Table III). Further multivariate analysis

using a COX regression model revealed that an ECOG performance

status of 1 was an independent factor of poor prognosis for PFS in

patients with mCRC treated with fruquintinib plus ICIs (Table III).

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analysis

for progression-free survival. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for progression-free survival.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.97 | 0.58–1.63 | 0.912 |

|

|

|

| Age (<60 vs.

≥60) | 0.54 | 0.32–0.92 | 0.022 | 0.69 | 0.40–1.19 | 0.180 |

| ECOG performance

status (0 vs. 1) | 0.25 | 0.14–0.46 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.15–0.52 | <0.001 |

| Degree of

differentiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low vs.

high | 1.36 | 0.77–2.39 | 0.293 |

|

|

|

| Low vs.

middle | 1.21 | 0.58–3.20 | 0.703 |

|

|

|

| High

vs. middle | 1.28 | 0.48–3.38 | 0.620 |

|

|

|

| Tumor location

(right vs. left) | 1.14 | 0.64–2.04 | 0.652 |

|

|

|

| Number of

metastases (<3 vs. ≥3) | 1.18 | 0.63–2.23 | 0.603 |

|

|

|

| Liver metastases

(no vs. yes) | 0.55 | 0.33–0.93 | 0.027 | 0.72 | 0.42–1.23 | 0.226 |

| Lung metastases (no

vs. yes) | 1.28 | 0.77–2.13 | 0.349 |

|

|

|

| Number of treatment

lines (3 vs. >3) | 1.45 | 0.81–2.58 | 0.207 |

|

|

|

| Baseline

carcinoembryonic antigen (<5 vs. ≥5) | 0.73 | 0.43–1.22 | 0.227 |

|

|

|

| BRAF

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unknown

vs. mutated | 1.00 | 0.55–1.80 | 0.989 |

|

|

|

| Unknown

vs. wild-type | 1.43 | 0.34–5.97 | 0.622 |

|

|

|

| Mutated

vs. wild-type | 1.46 | 0.35–6.09 | 0.608 |

|

|

|

| KRAS

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unknown

vs. mutated | 0.86 | 0.43–1.71 | 0.670 |

|

|

|

| Unknown

vs. wild-type | 0.81 | 0.44–1.48 | 0.491 |

|

|

|

| Mutated

vs. wild-type | 0.44 | 0.43–1.44 | 0.788 |

|

|

|

| Prior TKI drugs

therapy (no vs. yes) | 0.74 | 0.41–1.33 | 0.309 |

|

|

|

| Prior radiotherapy

(no vs. yes) | 1.55 | 0.91–2.65 | 0.109 |

|

|

|

| Prior surgery (no

vs. yes) | 1.64 | 0.86–3.13 | 0.133 |

|

|

|

| Initial dose of

fruquintinib |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 mg

vs. 4 mg | 0.73 | 0.33–1.61 | 0.430 |

|

|

|

| 3 mg

vs. 5 mg | 1.50 | 0.87–2.59 | 0.145 |

|

|

|

| 4 mg

vs. 5 mg | 1.53 | 0.89–2.63 | 0.127 |

|

|

|

| ICIs (PD-1

inhibitors vs. PD-L1 inhibitors) | 1.71 | 0.82–3.54 | 0.151 |

|

|

|

Safety

The AEs during treatment in both groups were

predominantly grade 1–2 according to the Common Terminology

Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (20), with the most common being hand-foot

syndrome (PD-1 inhibitor combination group vs. PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group, 20.6 vs. 33.3%), proteinuria (23.8 vs. 33.3%)

and hypothyroidism (31.7 vs. 26.7%). Notably, grade 3 or worse AEs

were infrequent. Throughout the treatment, no patients in either

group died due to serious AEs, such as life-threatening, permanent

or severe disability or loss of function.

The treatment was discontinued in 2 patients in the

PD-1 inhibitor combination group due to immune-related diabetes and

immune-related hepatic injury, respectively. In the PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group, no patients discontinued treatment for AEs.

Additionally, the incidence of AEs did not differ significantly

between the PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor combination group (P>0.05,

Table IV) and the incidence of AEs

did not differ significantly between PD-1 inhibitor combination

groups (P>0.05, Table V).

| Table IV.Adverse events. |

Table IV.

Adverse events.

|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Adverse event | PD-1 inhibitor

combination group (n=63) | PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group (n=15) | χ2 | P-value | PD-1 inhibitor

combination group (n=63) | PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group (n=15) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Hypertension | 10 (15.9) | 3 (20.0) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

| Hand-foot

syndrome | 13 (20.6) | 5 (33.3) | 0.50 | 0.479 | 4 (6.3) | 3 (20.0) | 1.35 | 0.246 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.12 | 0.726 |

|

|

|

|

| Fatigue | 7 (11.1) | 4 (26.7) | 1.31 | 0.253 |

|

|

|

|

| Decreased

appetite | 3 (4.8) | 3 (20.0) | 2.11 | 0.147 |

|

|

|

|

|

Nausea/vomiting | 1 (1.6) | 1 (6.7) | 0.04 | 0.834 |

|

|

|

|

| Leukopenia | 7 (11.1) | 2 (13.3) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

|

Thrombocytopenia | 5 (7.9) | 1 (6.7) | NA | >0.999 | 2 (3.2) |

| NA | >0.999 |

| Hepatic injury | 1 (1.6) | 1 (6.7) | 0.04 | 0.834 | 1 (1.6) |

| NA | >0.999 |

| Proteinuria | 15 (23.8) | 5 (33.3) | 0.19 | 0.667 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (6.7) | 0.04 | 0.834 |

|

Hyperthyroidism | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.01 | 0.909 |

|

|

|

|

| Hypothyroidism | 20 (31.7) | 4 (26.7) | 0.01 | 0.943 |

|

|

|

|

| Mucositis oral | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.01 | 0.909 |

|

|

|

|

| Rash | 3 (4.8) | 1 (6.7) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

| Hoarseness | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

| Muscle

tenderness | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

| Hyperglycemia | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | NA | >0.999 | 1 (1.6) |

| 0.43 | 0.512 |

| Infection | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | NA | >0.999 |

|

|

|

|

| Table V.PD-1 inhibitor combination group

adverse events (any grade). |

Table V.

PD-1 inhibitor combination group

adverse events (any grade).

| Adverse event | Camrelizumab

(n=11) | Sintilimab

(n=10) | Tislelizumab

(n=9) | Toripalimab

(n=13) | Serplulimab

(n=20) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Hypertension | 4 (36.4) | 2 (20) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (5) | 6.177 | 0.186 |

| Hand-foot

syndrome | 4 (36.4) | 3 (30) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (25) | 8.734 | 0.068 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (5) | 4.191 | 0.381 |

| Fatigue | 1 (9.1) | 1 (10) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (20) | 3.681 | 0.451 |

| Decreased

appetite | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (5) | 2.851 | 0.583 |

|

Nausea/vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 3.991 | 0.407 |

| Leukopenia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (5) | 5.307 | 0.257 |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (5) | 6.664 | 0.155 |

| Hepatic injury | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 3.991 | 0.407 |

| Proteinuria | 5 (45.5) | 3 (30) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (25) | 8.190 | 0.085 |

|

Hyperthyroidism | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10) | 4.617 | 0.329 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (18.2) | 4 (40) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (15.4) | 10 (50) | 6.428 | 0.169 |

| Mucositis oral | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5) | 3.401 | 0.493 |

| Rash | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 4.090 | 0.394 |

| Hoarseness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 3.219 | 0.522 |

| Muscle

tenderness | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5) | 3.294 | 0.510 |

| Hyperglycemia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (5) | 2.744 | 0.601 |

| Infection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 3.219 | 0.522 |

The present findings are preliminary and recommend

conducting well-designed prospective cohort studies or multi-center

collaborations in the future, including a larger sample size, to

validate the present findings and draw more conclusive

conclusions.

Discussion

Immunotherapy has become a research hotspot in the

treatment of mCRC, with the combination of ICIs and TKIs being

widely endorsed and established as the mainstream treatment

strategy in later-line therapies. The REGONIVO trial reported an

ORR of >30% in patients with MSS-type mCRC who received

regorafenib plus nivolumab therapy, demonstrating favorable

efficacy along with favorable safety (21). Although studies have shown that the

combination of TKI and ICIs is more effective than TKI monotherapy,

to the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet compared the

efficacy and safety of TKIs plus different ICIs. The present study

retrospectively assessed the efficacy and safety of fruquintinib

plus different ICIs in MSS/pMMR mCRC. The present study aimed to

identify the optimal combination, understand the factors

influencing outcomes and determine the patient populations most

likely to benefit from this therapy. The results showed no

statistically significant differences in ORR (7.9 vs. 20.0%;

P=0.363), DCR (74.6 vs. 60.0%; P=0.418) and median PFS (7.0 vs. 8.3

months; P=0.14) between the PD-1 inhibitor and PD-L1 inhibitor

combination groups. When comparing the ORR and DCR between the two

groups, the DCR was found to be more promising in the PD-1 group,

while the ORR was improved in the PD-L1 group, although neither

difference was statistically significant.

The inconsistency between the DCR and ORR is a

common and well-elucidated phenomenon (22–24).

The most direct source of the inconsistency between the values is

the patients who only achieved SD. These patients are included in

the DCR but not in the ORR. In terms of the mechanism of action, it

takes time to activate the immune system. Thus, the ORR may not be

high at early evaluation, but the proportion of patients achieving

SD may be relatively high (with a higher DCR). In addition, tumors

exhibit heterogeneity and have drug resistance. At present, the

drug-resistance mechanisms of targeted immunotherapy combinations

are not fully understood. From the perspective of the patient

population, patients with a large tumor burden may find it more

difficult to achieve a deep response (CR/PR). The resistance to

treatment may increase with increased previous treatment lines and

the drugs are more likely to control the tumor rather than

significantly shrink it (high proportion of SD). The difference in

the number of cases between the PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor

combination group) may also lead to the inconsistency of ORR and

DCR, which is also the limitation of this study.. In the future,

the number of the population will be further expanded, the

follow-up time will be extended and the data will be optimized to

verify and obtain more accurate results.

The findings of the present study were consistent

with another retrospective study reported by Yang et al

(16), which also analyzed the

efficacy and safety of fruquintinib + PD-1 inhibitors in mCRC,

reporting an ORR of 11.4%, a DCR of 84.3% and a median PFS of 5.5

months. The PD-1 inhibitors in the present retrospective study

included sintilimab, tislelizumab, toripalimab and pembrolizumab.

However, due to significant differences in the sample sizes between

groups, subgroup analyses were not performed. A study by Bai et

al (25) evaluated the

fruquintinib + geptanolimab for the treatment of CRC. The results

indicated that, in all evaluable patients with mCRC, the overall

ORR was 26.7%, with an ORR of 33.3% in the recommended phase II

dose (RP2D) group, a DCR of 80.0% and a median PFS of 7.3 months.

For patients with MSS-type mCRC, the ORR was 25.0%, the DCR was 75%

and the median PFS was 5.5 months. The findings of the present

study suggested that fruquintinib plus ICI exhibited manageable

safety and promising antitumor activity in patients with mCRC. In

another retrospective study reported by Gou et al (17), fruquintinib plus PD-1 inhibitors in

45 patients with MSS-type mCRC resulted in a DCR of 62.2%, ORR of

11.1% and median PFS of 3.8 months. The limited efficacy observed

might be attributed to the lack of strict ECOG performance status

criteria for inclusion criteria. Additionally, considering patient

tolerance, the dosing of fruquintinib might be lower in real-world

settings, which could also impact efficacy. The present study

evaluated the PFS of patients treated with fruquintinib plus

different PD-1 inhibitors and observed no statistically significant

differences between the different PD-1 inhibitors. As a result, the

most effective ICIs could not be identified.

The CheckMate-142 (26) and CheckMate 8HW (27) studies both confirmed the favorable

efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors plus cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4

(CTLA-4) inhibitors in MSI-H CRC. Similarly, studies are presently

exploring the efficacy of dual ICI therapy in MSS-type mCRC. In a

phase I clinical trial presented at the 2022 ESMO-GI conference

(28), the combination of the

botensilimab (a CTLA-4 inhibitor) and balstilimab (a PD-1

inhibitor) showed strong clinical activity and sustained efficacy

in patients with MSS mCRC who had previously failed multiple lines

of treatment. Importantly, the treatment was well-tolerated with no

serious AEs, indicating the broad potential of dual immunotherapy

in the management of mCRC. However, the present study did not

include patients receiving the combination of fruquintinib and dual

immunotherapy due to economic limitations, as the high cost of dual

immunotherapy might have been unaffordable for some patients. By

contrast, PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors are more cost-effective and

therefore more accessible to patients, while still providing

significant therapeutic benefits.

In the present study, univariate analysis indicated

that age, ECOG performance status and liver metastasis were

associated with PFS. Multivariate Cox regression analysis

identified an ECOG performance status of 1 as an independent risk

factor for PFS. Immunotherapy exerts its effect by activating

immune cells that specifically recognize and eliminate tumor cells,

requiring a sufficient immune cell reserve. Patients with an ECOG

performance status of 0 generally have improved physical conditions

and a stronger immune response. In the CheckMate 153 trial

(29), patients with an ECOG

performance status of 0–1 derived significantly more benefit from

immunotherapy compared with those with a score of 2. Similarly, the

KEYNOTE-177 trial (30) observed

that PD-1 inhibitors did not significantly improve PFS in patients

with an ECOG performance status of 1. Additionally, Fakih et

al (31) found that liver

metastasis is a poor prognostic factor. However, other studies have

shown no association between KRAS mutations, lung

metastasis, liver metastasis and PFS or OS, warranting further

validation in larger clinical trials (32,33).

The most common AEs previously reported with

fruquintinib plus ICIs were hypertension, hand-foot syndrome and

hypothyroidism. In the present study, the most common AEs in the

PD-1 inhibitor combination group were hypothyroidism (31.7%),

proteinuria (23.8%) and hand-foot syndrome (20.6%). In the PD-L1

inhibitor combination group, the most common AEs were proteinuria

(33.3%), hand-foot syndrome (33.3%) and hypothyroidism (26.7%). No

deaths due to serious AEs were reported in either group.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly,

it is a single-center, retrospective analysis, which might

introduce selection bias. Secondly, the administration of five

different PD-1 inhibitors and three initial doses of fruquintinib

in the PD-1 inhibitor combination group might have affected

treatment consistency. Next, the sample size was relatively small

and the follow-up period was relatively short. The reason why the

sample size, especially the PD-L1 inhibitor combination group, is

small is that fruquintinib is only reimbursed by Chinese medical

insurance for third-line colorectal cancer treatment, with no

coverage beyond this line. Immunotherapy drugs are not covered for

colorectal cancer at all. Consequently, few patients can afford the

combination of immunotherapy and fruquintinib. Affordability is

even lower for combinations involving PD-L1 inhibitors due to their

higher cost. Additionally, the present study has limitations in

safety assessment, as the small sample size limits the ability to

detect rare toxicities and the relatively short follow-up time

affects the assessment of long-term toxicities. In the future,

large-scale real-world research should be carried out to confirm

safety, explore biomarkers for toxicity prediction and optimize

adverse reaction management strategies.

Although there was no statistically significant

difference in efficacy between the groups of fruquintinib combined

with PD-1 inhibitor and fruquintinib combined with PD-L1 inhibitor,

it should be noted that the statistical power of this result was

low and it should be regarded as a preliminary finding that needs

to be verified in future larger-scale studies. Similarly, for the

present results where no significant difference was found, the

possibility of clinically relevant differences should not be ruled

out as the lack of significance may be due to insufficient sample

size. Finally, one of the other major limitations of the present

study is the lack of mature OS data. This is mainly because the

follow-up time at the data cut-off was relatively short and some

patients were lost to follow-up. Therefore, it is currently

impossible to evaluate the long-term survival benefits of the

present study based on OS. Against the backdrop of a high risk of

loss to follow-up, the present study considered earlier-occurring

endpoints with more reliable data acquisition (such as PFS or ORR)

as the primary endpoints. The data collection was relatively

complete (loss to follow-up occurred after the PFS event), so the

analysis results were reliable and clinically meaningful. Future

studies should pre-set a more rigorous analysis plan for OS in the

case of a high loss-to-follow-up rate in the protocol. In future

studies, we will be committed to improving the survival follow-up

strategy and investing more resources in designing and implementing

a more powerful survival follow-up strategy.

In conclusion, although no statistically significant

differences in efficacy were observed between the PD-1 inhibitor

combination group and the PD-L1 inhibitor combination group,

fruquintinib plus ICIs improved survival compared with the

previously reported efficacy of fruquintinib monotherapy in mCRC.

Furthermore, this combination therapy did not increase serious AEs,

indicating an acceptable safety profile. Future clinical trials

with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the findings of the

present study and explore the potential of immunotherapy plus

targeted therapy to establish new treatment strategies for mCRC in

clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Jiangsu Provincial Cancer

Hospital 2023 Hospital Science and Technology Development Fund

(grant no. ZL202308).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author's contributions

YP was responsible for the curation of data, formal

analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing the

original draft and reviewing and editing of the manuscript. SL

analyzed data and edited the manuscript. LZ was responsible for the

conceptualization and supervision of the present study. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. YP, SL and

LZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted in compliance with Good

Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013

version) and was approved by the ethics committee of the Jiangsu

Cancer Hospital (approval no. KY-2024-071). The requirement for

informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of

the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K,

Chen R, Li L, Wei W and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:47–53. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lichtenstern CR, Ngu RK, Shalapour S and

Karin M: Immunotherapy, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Cells.

9:6182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chinese Society Of Clinical Oncology Csco

Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines For Colorectal Cancer Working

Group, . Chinese society of clinical oncology (CSCO) diagnosis and

treatment guidelines for colorectal cancer 2018 (english version).

Chin J Cancer Res. 31:117–134. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Diaz LA Jr, Shiu KK, Kim TW, Jensen BV,

Jensen LH, Punt C, Smith D, Garcia-Carbonero R, Benavides M, Gibbs

P, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for microsatellite

instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal

cancer (KEYNOTE-177): Final analysis of a randomised, open-label,

phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 23:659–670. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Koopman M, Kortman GA, Mekenkamp L,

Ligtenberg MJ, Hoogerbrugge N, Antonini NF, Punt CJ and van Krieken

JH: Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic

advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 100:266–273. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bever KM and Le DT: An expanding role for

immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

15:401–410. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ,

Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al:

Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with

advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 366:2455–2465. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chalabi M, Fanchi LF, Dijkstra KK, Van den

Berg JG, Aalbers AG, Sikorska K, Lopez-Yurda M, Grootscholten C,

Beets GL, Snaebjornsson P, et al: Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads

to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient

early-stage colon cancers. Nat Med. 26:566–576. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tan AC, Bagley SJ, Wen PY, Lim M, Platten

M, Colman H, Ashley DM, Wick W, Chang SM, Galanis E, et al:

Systematic review of combinations of targeted or immunotherapy in

advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 9:e0024592021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sun Q, Zhou J, Zhang Z, Guo M, Liang J,

Zhou F, Long J, Zhang W, Yin F, Cai H, et al: Discovery of

fruquintinib, a potent and highly selective small molecule

inhibitor of VEGFR 1, 2, 3 tyrosine kinases for cancer therapy.

Cancer Biol Ther. 15:1635–1645. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dasari A, Lonardi S, Garcia-Carbonero R,

Elez E, Yoshino T, Sobrero A, Yao J, García-Alfonso P, Kocsis J,

Cubillo Gracian A, et al: Fruquintinib versus placebo in patients

with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (FRESCO-2): An

international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3

study. Lancet. 402:41–53. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fusco MJ, Casak SJ, Mushti SL, Cheng J,

Christmas BJ, Thompson MD, Fu W, Wang H, Yoon M, Yang Y, et al: FDA

approval summary: fruquintinib for the treatment of refractory

metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 30:3100–3104. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li Q, Cheng X, Zhou C, Tang Y, Li F, Zhang

B, Huang T, Wang J and Tu S: Fruquintinib enhances the antitumor

immune responses of anti-programmed death receptor-1 in colorectal

cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8419772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Guo Y, Zhang W, Ying J, Zhang Y, Pan Y,

Qiu W, Fan Q, Xu Q, Ma Y, Wang G, et al: Phase 1b/2 trial of

fruquintinib plus sintilimab in treating advanced solid tumours:

The dose-escalation and metastatic colorectal cancer cohort in the

dose-expansion phases. Eur J Cancer. 181:26–37. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

An T, Lian Y, Zhou Q, Zhao C, Wang Z and

Zhao R: Fruquintinib with PD-1 inhibitors versus fruquintinib

monotherapy in late-line mCRC: A retrospective cohort study based

on propensity score matching. J Clin Oncol. 42 (Suppl 3):S1392024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yang X, Yin X, Qu X, Guo G, Zeng Y, Liu W,

Jagielski M, Liu Z and Zhou H: Efficacy, safety, and predictors of

fruquintinib plus anti-programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) antibody

in refractory microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer in

a real-world setting: A retrospective cohort study. J Gastrointest

Oncol. 14:2425–2435. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gou M, Qian N, Zhang Y, Yan H, Si H, Wang

Z and Dai G: Fruquintinib in combination with PD-1 inhibitors in

patients with refractory non-MSI-H/pMMR metastatic colorectal

cancer: A real-world study in China. Front Oncol. 12:8517562022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Freites-Martinez A, Santana N,

Arias-Santiago S and Viera A: Using the common terminology criteria

for adverse events (CTCAE-version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of

adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl

Ed). 112:90–92. 2021.(In English, Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N, Kojima T,

Kawazoe A, Asayama M, Yoshii T, Kotani D, Tamura H, Mikamoto Y, et

al: Regorafenib plus nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or

colorectal cancer: An open-label, dose-escalation, and

dose-expansion phase Ib trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J Clin Oncol.

38:2053–2061. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, Ford R,

Schwartz LH, Mandrekar S, Lin NU, Litière S, Dancey J, Chen A, et

al: iRECIST: Guidelines for response criteria for use in trials

testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 18:e143–e152. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR,

Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al:

Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:1627–1639. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin

EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG,

et al: Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N

Engl J Med. 364:514–523. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bai Y, Xu N, An S, Chen W, Gao C and Zhang

D: A phase Ib trial of assessing the safety and preliminary

efficacy of a combination therapy of geptanolimab (GB 226) plus

fruquintinib in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).

J Clin Oncol. 39 (Suppl 15):e155512021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi

S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, Desai J, Hill A, Axelson M, Moss RA, et al:

Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient

or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate

142): An open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol.

18:1182–1191. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Andre T, Elez E, Van Cutsem E, Jensen LH,

Bennouna J, Mendez G, Schenker M, De la Fouchardière C, Limon MJ,

Yoshino T, et al: Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) vs

chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line (1L) treatment for

microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient

(MSI-H/dMMR) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): First results of

the CheckMate 8HW study. J Clin Oncol. 42 (Suppl 3):LBA7682024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bullock A, Grossman J, Fakih M, Lenz H,

Gordon M, Margolin K, Wilky B, Mahadevan D, Trent J, Bockorny B, et

al: LBA O-9 Botensilimab, a novel innate/adaptive immune activator,

plus balstilimab (anti-PD-1) for metastatic heavily pretreated

microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 33 (Suppl

4):S3762022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Waterhouse DM, Garon EB, Chandler J,

McCleod M, Hussein M, Jotte R, Horn L, Daniel DB, Keogh G, Creelan

B, et al: Continuous versus 1-year fixed-duration nivolumab in

previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate

153. J Clin Oncol. 38:3863–3873. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Andre T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, Jensen BV,

Jensen LH, Punt CJA, Smith DM, Garcia-Carbonero R, Benavides M

Gibbs OP, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for

microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair deficient

metastatic colorectal cancer: The phase 3 KEYNOTE-177 study. J Clin

Oncol. 38 (Suppl 18):LBA42020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fakih M, Raghav KPS, Chang DZ, Bendell JC,

Larson T, Cohn AL, Huyck TK, Cosgrove D, Fiorillo JA, Garbo LE, et

al: Single-arm, phase 2 study of regorafenib plus nivolumab in

patients with mismatch repair-proficient (pMMR)/microsatellite

stable (MSS) colorectal cancer (CRC). J Clin Oncol. 39 (Suppl

15):S35602021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Albertsmeier M, Riedl K, Stephan AJ, Drefs

M, Schiergens TS, Engel J, Angele MK, Werner J and Guba M: Improved

survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases in patients

with unresectable lung metastases. HPB (Oxford). 22:368–375. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, Lonardi

S, Zagonel V, Salvatore L, Cortesi E, Tomasello G, Ronzoni M, Spadi

R, et al: Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for

metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 371:1609–1618. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|