Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) originate from

peptidergic neurons and neuroendocrine cells in the body, with the

gastrointestinal tract and pancreas being the most prevalent

anatomical sites, accounting for >50% of all neuroendocrine

tumors (NETs) (1). A previous study

has shown that the incidence of NENs in the United States increased

from 1.09 per 100,000 in 1973 to 5.25 per 100,000 in 2004,

representing a 3.8-fold rise (2).

Another study indicated that among gastrointestinal NENs reported

in China from 1957 to 2011, pancreatic NETs were the most common,

followed by those in the rectum, appendix, stomach, colorectum,

jejunoileum and duodenum, respectively (3). Based on the World Health Organization

(WHO) 2010 classification, NETs of the digestive system are mainly

divided into three categories: i) NET; ii) neuroendocrine carcinoma

(NEC); and iii) mixed adenoendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) (4). According to the European NET Society

(ENETS) grading method for NENs of the gastrointestinal tract,

well-differentiated tumors are classified as low grade (G1) and

intermediate grade (G2), while poorly differentiated tumors are

classified as high-grade (G3) (5).

Accurate grading requires classifying poorly differentiated NENs,

with features such as abnormal cell morphology and active

proliferation, as high-grade, whereas well-differentiated tumors

are histologically defined by features such as uniform nuclear

structures (6).

Colorectal NEC (CRNEC), a relatively uncommon

malignancy, includes tumors classified, as per the WHO 2010

criteria, as NET, NEC and MANEC. Currently, the main treatment

strategy involves surgical removal followed by chemotherapy. Most

NEC cases in the colon and rectum are of the large cell type (75%),

whereas small cell NEC predominates in the anus (7). NEC cells are positive for at least one

neuroendocrine immunohistochemical marker, such as AE1/AE3,

chromogranin A, CD56, Ki-67 or synaptophysin (Syn) (8,9).

Research shows that CRNEC exhibits high aggressiveness, with

hepatic metastases present in 40–50% of cases upon initial

detection (10). One study has

reported that well-differentiated G3 NETs exhibit a mean Ki-67

index of 30%, significantly lower than the 80% seen in poorly

differentiated pancreatic NECs in pancreatic G3 NENs, with a median

overall survival (OS) of 99 months versus 17 months, respectively

(11).

To the best of our knowledge, studies focusing on

CRNEC remain scarce. Factors such as surgical resection and the use

of adjuvant chemotherapy have been associated with improved

survival in CRNEC. Therefore, the current study conducted a

comparative analysis between histopathological factors and survival

outcomes for patients with CRNEC, and aimed to provide insights in

the clinical management of patients diagnosed with CRNEC.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The present single-center retrospective study

enrolled 157 consecutive patients with CRNEC receiving treatment at

Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (Harbin, China) from

January 2000 to December 2019. There were 102 male and 55 female

patients; and the median age was 55 years (age range, 59–81 years).

WHO 2019 centralized reclassification standards were used to ensure

the diagnostic homogeneity of the patients enrolled over this

period (4). Complete

clinicopathological data and follow-up information were recorded

for the enrolled patients. The study protocol received approval

from the Institutional Review Board of Harbin Medical University

Cancer Hospital (approval no. 82271845; October 10, 2019) and

strictly adhered to the ethical principles of The Declaration of

Helsinki (1964) and subsequent amendments. Before treatment, the

enrolled patients provided written informed consent for the use of

their data in research.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion

criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Pathologically confirmed diagnosis of CRNEC; ii) age ≥18 years with

adequate Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (≥2)

(12) to tolerate surgical or other

treatments (including chemotherapy and radiotherapy); iii) complete

clinicopathological records and treatment information; and iv)

maintained protocol adherence with follow-up. The exclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Patients with idiopathic inflammatory

bowel diseases of chronic evolution, notably Crohn's disease and

ulcerative colitis; ii) patients with uncontrolled comorbidities or

systemic illnesses; iii) patients with poor treatment adherence or

unwillingness to comply with therapeutic protocols; and iv)

patients with missing follow-up information.

Study variables

According to the WHO 2019 Classification of

Digestive System Tumors (5th edition) (4), these neoplasms were categorized into

five histological categories based on tumor size, number of lymph

nodes affected by cancer and distant metastasis status: i) NET-G1:

Typical carcinoid tumors with well-differentiated morphology and

low proliferative activity [Ki-67 index <3%; mitotic count

<2/10 high-power fields (HPFs)]; ii) NET-G2:

Moderately-differentiated tumors exhibiting intermediate-grade

features (Ki-67 index 3–20%; mitotic count 2–20/10 HPFs); iii)

NEC-G3: Poorly-differentiated high-grade malignancies, including

small cell carcinoma and large cell NEC subtypes (Ki-67 index

>20%; mitotic count >20/10 HPFs); iv) MANEC: Biphasic tumors

containing both gland-forming adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine

components (each constituting ≥30% of the lesion); and v)

hyperplastic and pre-neoplastic lesions: Non-invasive proliferation

with malignant potential.

According to the ENETS 2017 guidelines (13), based on the Ki-67 index and mitotic

figures, the neoplasms were assigned three differentiation grades

as follows: i) Low-grade (G1): Ki-67 index ≤2% or mitotic count

<2/10 HPFs; ii) intermediate-grade (G2): Ki-67 index 3–20% or

mitotic count 2–20/10 HPFs; and iii) high-grade (G3): Ki-67 index

>20% or mitotic count >20/10 HPFs.

AE1/AE3 expression

AE1/AE3 expression levels were detected and

evaluated by the Department of Pathology (Harbin Medical University

Cancer Hospital). Pathological formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

tissues from the enrolled patients were obtained. The manual

immunohistochemistry staining assay was followed according to the

standard protocols: i) The CRNEC tissues were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at 4°C for 24 h and embedded in 10%

paraffin at room temperature for 48 h; ii) paraffin blocks were

sliced at 60–70°C, and dewaxed twice in xylene (10 min each) and in

a gradient series of alcohol (100, 95, 85 and 70%) for 5 min; iii)

antigen retrieval; iv) endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked

by incubating the samples in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide prepared in

methanol for 30 min at room temperature; v) tissues were blocked

with 10% goat serum albumin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

for 30 min at room temperature; vi) tissues were incubated with an

anti-AE1/AE3 primary antibody (1:500; cat. no. 67306S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C and with a

HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no.

8125S; Cell Signaling Technology) for 30 min at room temperature;

vii) color rendering using diaminobenzidine (1:20; cat. no. P0202;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology); viii) recombinant staining of

the cell nucleus with hematoxylin (cat. no. 14166S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.); ix) dehydration and sealing in an alcohol

gradient (95, 95 and 100%) for 3 min and in xylene for 3 min; and

x) microscopic examination of three fields using the Aperio Image

Scope system (version 12.3.3; Leica Biosystems).

The expression of AE1/AE3 was obtained by

immunohistochemistry, authors that evaluated the density and

intensity of stained cells were blinded to the clinicopathological

data. The density of AE1/AE3-positively stained cells was scored as

follows: i) 0: <1% stained; ii) 1: 1–10%; iii) 2: 11–50%; vi) 3:

51–75%; and v) 4: 76–100%. The staining intensity of

AE1/AE3-positivity was scored as follows: i) 0: No staining; ii) 1:

Light yellow staining; iii) 2: Brown-yellow staining; and iv) 3:

Yellowish-brown staining. The total AE1/AE3 expression score was

calculated by multiplying the density score (0–4) and the intensity score (0–3), yielding a composite score ranging from

0 to 12. In the present study, patients were separated into two

groups based on AE1/AE3 expression: AE1/AE3 negative expression

(scores <1 based on stained cell density and intensity) and

AE1/AE3 positive expression (scores ≥1).

Follow-up

Patients were regularly followed up through medical

records (outpatient or inpatient), telephone interviews and

scheduled clinical visits. Follow-up assessments included: i)

Clinical symptom observation; ii) routine hematological tests (for

example, complete blood count, blood biochemistry and tumor

markers); and iii) imaging examinations (CT or MRI). Postoperative

surveillance was conducted every 3–6 months. If tumor progression,

recurrence or metastasis was suspected during follow-up, a repeat

biopsy was performed for reassessment and re-grading. Disease free

survival (DFS) was defined as the time from initial diagnosis to

recurrence or to the last follow-up. OS was defined as the time

from initial diagnosis to death or to the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

19.0 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics). χ2

test and Fisher's exact test was used to assess associations

between categorical variables and multiple groups. Kaplan-Meier

estimates were generated to analyze survival, and differences

between survival curves were assessed by log-rank test. Univariate

and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to

identify the potential prognostic factors. Significant variables

from the univariate analysis (P<0.05) were included in the

multivariate Cox regression model. To address potential confounding

from variations in treatment strategies (such as postoperative

chemotherapy and radiotherapy), these factors were included as

covariates in the multivariate models. The multivariate analyses

formed the basis for constructing prognostic nomograms for DFS and

OS probabilities. Nomogram validation comprised calculation of the

C-index and the generation of calibration curves. A two-tailed

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Study population and

characteristics

Overall, 157 patients with CRNEC were enrolled onto

the present study, including 102 men (65%) and 55 women (35%). The

average age of enrolled patients was 54.89±12.86 years, ranging

from 26 to 82 years old. The average body mass index (BMI) was

24.11±3.22 kg/m2, ranging from 17.10 to 32.10

kg/m2. The primary site of 32 cases (20.4%) was the

colon, while the primary site for the other 125 cases (79.6%) was

the rectum. During the study period, regarding the

tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage of patients (14), there were four cases (2.5%) with

Tis, 63 cases (40.1%) with stage I, five cases (3.2%) with stage

II, 28 cases (17.8%) with stage III, 43 cases (27.4%) with stage IV

and 14 cases (8.9%) with an unknown stage. The gross type of CRNECs

included elevated type in 72 cases (45.9%), ulcerative type in 22

cases (14.0%) and infiltrative type in 63 cases (40.1%). Lymph node

dissection was performed in 46.1% (59/128) of surgically treated

patients. All enrolled patients were followed-up, and the last

follow-up date was October 2024. There were 39 cases (24.8%) with

distant metastasis and 15 cases (9.6%) with recurrence during the

follow-up time. The clinicopathological characteristics of the

patients are summarized in Table

SI.

Histological types in patients with

CRNEC

Based on the WHO 2019 Classification of Digestive

System Tumors (5th edition) (4),

the pathological types included in the present study were as

follows: i) 82 cases (52.2%) with NET-G1; ii) 13 cases (8.3%) with

NET-G2; iii) 54 cases (34.4%) with NEC-G3; and iv) eight cases

(5.1%) with MANEC.

The clinicopathological characteristics of patients

with different histological subtypes of CRNEC are detailed in

Table I. In the current study, the

total number of lymph nodes includes both metastatic and

non-metastatic lymph nodes, whereas the positive number of lymph

nodes includes only metastatic lymph nodes. Regarding the

clinicopathological characteristics of the patients, the

pathological subtypes were significantly associated with age,

surgical history, primary site, gross type, tumor size,

differentiation, total number of lymph node, positive number of

lymph node, TNM stage, perineural invasion, vascular tumor

thrombus, AE1/AE3, postoperative chemotherapy and postoperative

radiotherapy (all P<0.05).

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma of different

pathological subtypes. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma of different

pathological subtypes.

| Parameters | Group | NET-G1 | NET-G2 | NEC-G3 | MANEC | P-value |

|---|

| Total | - | 82 | 13 | 54 | 8 |

|

| Sex | Male | 53 (64.6) | 7 (53.8) | 39 (72.2) | 3 (37.5) | 0.330 |

|

| Female | 29 (35.4) | 6 (46.2) | 15 (27.8) | 5 (62.5) |

|

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | ≤24.49 | 41 (50.0) | 4 (30.8) | 27 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 0.669 |

|

| >24.49 | 41 (50.0) | 9 (69.2) | 27 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| Age, years | ≤55 | 46 (56.1) | 9 (69.2) | 17 (31.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0.029 |

|

| >55 | 36 (43.9) | 4 (30.8) | 37 (68.5) | 5 (62.5) |

|

| Surgical

history | No | 66 (80.5) | 7 (53.8) | 47 (87.0) | 5 (62.5) | 0.005 |

|

| Yes | 16 (19.5) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (13.0) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| Hypertension | No | 64 (78.0) | 9 (69.2) | 51 (94.4) | 7 (87.5) | 0.076 |

|

| Yes | 18 (22.0) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (5.6) | 1 (12.5) |

|

| Diabetes | No | 71 (86.6) | 12 (92.3) | 51 (94.4) | 7 (87.5) | 0.5675 |

|

| Yes | 11 (13.4) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (5.6) | 1 (12.5) |

|

| Primary site | Colon | 6 (7.3) | 3 (23.1) | 19 (35.2) | 4 (50.0) | <0.001 |

|

| Rectum | 76 (92.7) | 10 (76.9) | 35 (64.8) | 4 (50.0) |

|

| Gross type | Elevated type | 55 (67.1) | 4 (30.8) | 11 (20.4) | 2 (25.0) | <0.001 |

|

| Ulcerative

type | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (33.3) | 2 (25.0) |

|

|

| Infiltrative

type | 25 (30.5) | 9 (69.2) | 25 (46.3) | 4 (50.0) |

|

| Tumor size, cm | ≤2 | 66 (80.5) | 6 (46.2) | 8 (14.8) | 1 (12.5) | <0.001 |

|

| >2 | 3 (3.7) | 4 (30.8) | 28 (51.9) | 6 (75.0) |

|

|

| Unknown | 13 (15.9) | 3 (23.1) | 18 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) |

|

| Differentiation

grade | Low-grade (G1) | 80 (97.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (25.0) | <0.001 |

|

| Intermediate- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| grade (G2) | 1 (1.2) | 13 (100.0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (12.5) |

|

|

| High-grade

(G3) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (96.3) | 5 (62.5) |

|

| Total number of

lymph node | ≤18 | 10 (12.2) | 6 (46.2) | 19 (35.2) | 2 (25.0) | <0.001 |

|

| >18 | 4 (4.9) | 2 (15.4) | 11 (20.4) | 5 (62.5) |

|

|

| Unknown | 68 (82.9) | 5 (38.5) | 24 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) |

|

| Positive number of

lymph node | ≤5 | 11 (13.4) | 8 (61.5) | 17 (31.5) | 4 (50.0) | <0.001 |

|

| >5 | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (24.1) | 3 (37.5) |

|

|

| Unknown | 68 (82.9) | 5 (38.5) | 24 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) |

|

| TNM stage | Tis | 2 (2.4) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

|

| I | 57 (69.5) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (12.5) |

|

|

| II | 1 (1.2) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

| III | 6 (7.3) | 2 (15.4) | 17 (31.5) | 3 (37.5) |

|

|

| IV | 6 (7.3) | 5 (38.5) | 28 (51.9) | 4 (50.0) |

|

|

| Unknown | 10 (12.2) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Perineural

invasion | No | 80 (97.6) | 11 (84.6) | 49 (90.7) | 5 (62.5) | 0.006 |

|

| Yes | 2 (2.4) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (9.3) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| Vascular tumor

thrombus | No | 81 (98.8) | 10 (76.9) | 38 (70.4) | 5 (62.5) | <0.001 |

|

| Yes | 1 (1.2) | 3 (23.1) | 16 (29.6) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| AE1/AE3 | Negative | 29 (35.4) | 6 (46.2) | 47 (87.0) | 4 (50.0) | <0.001 |

|

| Positive | 53 (64.6) | 7 (53.8) | 7 (13.0) | 4 (50.0) |

|

| Postoperative

chemotherapy | No | 79 (96.3) | 8 (61.5) | 27 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | <0.001 |

|

| Yes | 3 (3.7) | 5 (38.5) | 27 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| Postoperative

radiotherapy | No | 82 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | 48 (88.9) | 7 (87.5) | 0.024 |

|

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) |

|

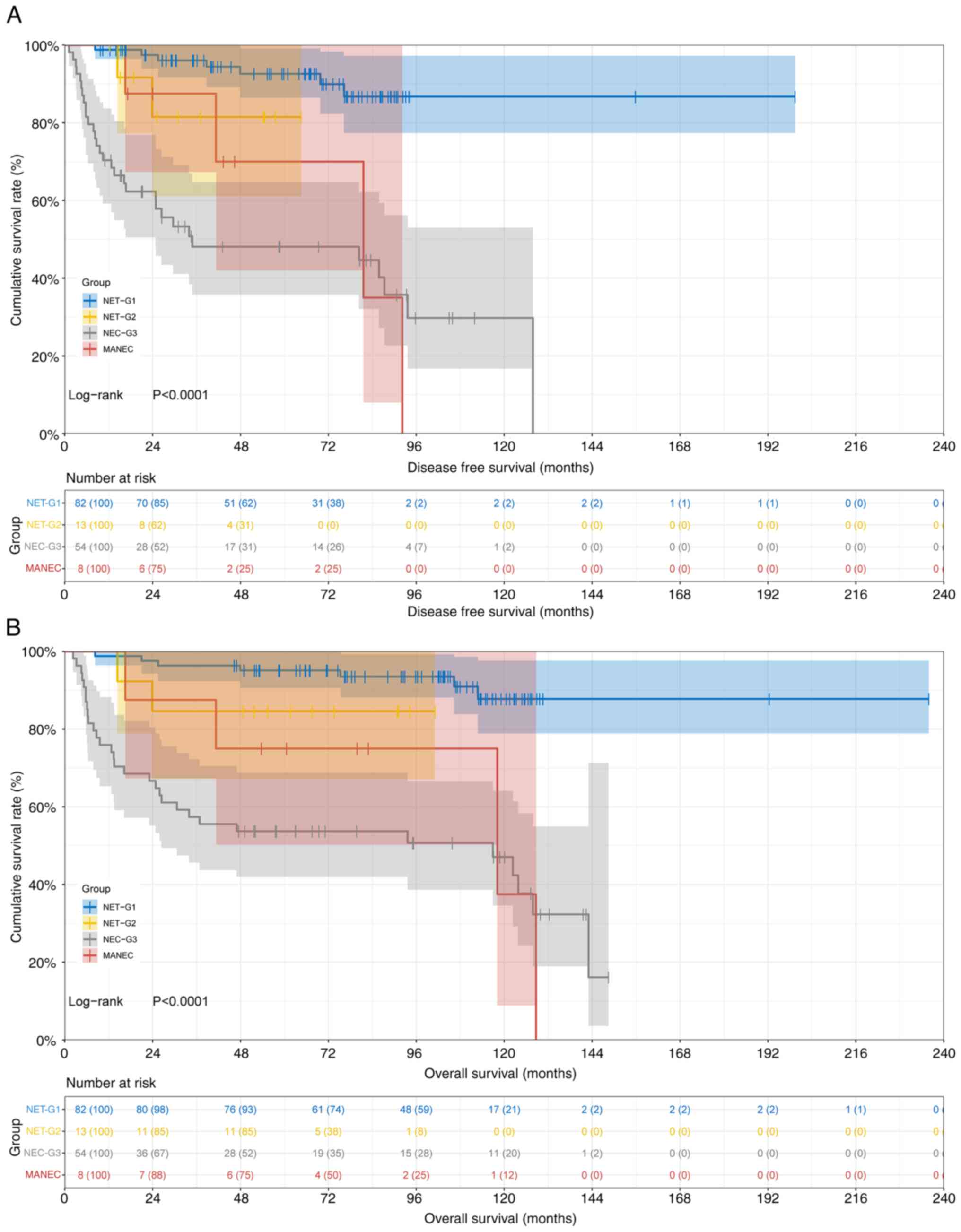

The mean DFS and OS durations stratified by

pathological subtypes were as follows: i) In the NET-G1 group, DFS

was 65.63 months (95% CI, 51.70–71.43) and OS was 103.00 months

(95% CI, 92.43–109.80); ii) in the NET-G2 group, DFS was 25.20

months (95% CI, 15.20–54.60) and OS was 61.73 months (95% CI,

48.80–91.13); iii) in the NEC-G3 group, DFS was 24.87 months (95%

CI, 13.50–34.57) and OS was 50.45 months (95% CI, 25.90–71.10); and

iv) in the MANEC group, DFS was 42.32 months (95% CI, 16.53–92.17)

and OS was 70.22 months (95% CI, 16.53–128.70). Comparative

analysis revealed statistically significant differences in both DFS

(χ2=40.110, P<0.0001) and OS (χ2=38.290,

P<0.0001) among the four pathological subtypes. The survival

curves are presented in Fig. 1.

Respectively, the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates

of DFS and OS stratified by pathological subtypes were as follows:

i) In the NET-G1 group, 0.988 (95% CI, 0.964–1.000), 0.960 (95% CI,

0.917–1.000) and 0.926 (95% CI, 0.865–0.991) for DFS, and 0.988

(95% CI: 0.964–1.000), 0.963 (95% CI: 0.924–1.000), 0.951 (95% CI,

0.905–0.999) for OS; ii) in the NET-G2 group, 1.000 (95% CI,

1.000–1.000), 0.815 (95% CI, 0.611–1.000) and 0.815 (95% CI,

0.611–1.000) for DFS, and 1.000 (95% CI, 1.000–1.000), 0.846 (95%

CI, 0.671–1.000) and 0.846 (95% CI, 0.671–1.000) for OS; iii) in

the NEC-G3 group, 0.704 (95% CI, 0.592–0.837), 0.481 (95% CI,

0.358–0.647) and 0.481 (95% CI, 0.358–0.647) for DFS, and 0.759

(95% CI, 0.653–0.882), 0.574 (95% CI, 0.456–0.722) and 0.537 (95%

CI, 0.419–0.688) for OS; and iv) in the MANEC group, 1.000 (95% CI,

1.000–1.000), 0.875 (95% CI, 0.673–1.000) and 0.700 (95% CI,

0.420–1.000) for DFS, and 1.000 (95% CI, 1.000–1.000), 0.875 (95%

CI, 0.673–1.000) and 0.750 (95% CI, 0.503–1.000) for OS. The

analysis revealed significantly higher 1-, 3- and 5-year DFS and OS

rates for NET-G1 and NET-G2 groups compared with the NEC-G3 group,

with the MANEC group showing intermediate outcomes. The prognosis

was strongly associated with pathological subtype. These findings

highlight the prognostic heterogeneity among the CRNEC subtypes,

with NET-G1 exhibiting the most favorable outcomes, underscoring

the importance of precise histological classification for clinical

management.

Differentiation in patients with

CRNEC

According to ENETS 2017 guidelines, the

differentiation types included in the present study were as

follows: i) 83 cases (52.9%) with low-grade (G1) CRNEC; ii) 16

cases (10.2%) with intermediate-grade (G2) CRNEC; and iii) 58 cases

(36.9%) with high-grade (G3) CRNEC. The clinicopathological

characteristics of patients with CRNEC according to differentiation

subtypes are detailed in Table II.

Regarding the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients,

the differentiation subtypes were associated with age, surgical

history, primary site, gross type, tumor size, histological type,

total lymph node, positive lymph node, TNM stage, vascular tumor

thrombus, AE1/AE3 and postoperative chemotherapy (P<0.05).

| Table II.Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma of

differentiation types. |

Table II.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma of

differentiation types.

| Parameters | Group | N | G1 | G2 | G3 | P-value |

|---|

| Total | - | 157 | 83 | 16 | 58 |

|

| Sex | Male | 102 (65.0) | 55 (66.3) | 8 (50.0) | 39 (67.2) | 0.413 |

|

| Female | 55 (35.0) | 28 (33.7) | 8 (50.0) | 19 (32.8) |

|

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | ≤24.49 | 77 (49.0) | 40 (48.2) | 6 (37.5) | 31 (53.4) | 0.515 |

|

| >24.49 | 80 (51.0) | 43 (51.8) | 10 (62.5) | 27 (46.6) |

|

| Age, years | ≤55 | 75 (47.8) | 46 (55.4) | 10 (62.5) | 19 (32.8) | 0.014 |

|

| >55 | 82 (52.2) | 37 (44.6) | 6 (37.5) | 39 (67.2) |

|

| Surgical

history | No | 125 (79.6) | 68 (81.9) | 7 (43.8) | 50 (86.2) | 0.001 |

|

| Yes | 32 (20.4) | 15 (18.1) | 9 (56.2) | 8 (13.8) |

|

| Hypertension | No | 131 (83.4) | 66 (79.5) | 12 (75.0) | 53 (91.4) | 0.095a |

|

| Yes | 26 (16.6) | 17 (20.5) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (8.6) |

|

| Diabetes | No | 141 (89.8) | 73 (88.0) | 14 (87.5) | 54 (93.1) | 0.583a |

|

| Yes | 16 (10.2) | 10 (12.0) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (6.9) |

|

| Primary site | Colon | 32 (20.4) | 7 (8.4) | 3 (18.8) | 22 (37.9) |

<0.001a |

|

| Rectum | 125 (79.6) | 76 (91.6) | 13 (81.2) | 36 (62.1) |

|

| Gross type | Elevated type | 72 (45.9) | 56 (67.5) | 5 (31.2) | 11 (19.0) |

<0.001a |

|

| Ulcerative

type | 22 (14.0) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (34.5) |

|

|

| Infiltrative

type | 63 (40.1) | 25 (30.1) | 11 (68.8) | 27 (46.6) |

|

| Tumor size, cm | ≤2 | 81 (51.6) | 67 (80.7) | 7 (43.8) | 7 (12.1) |

<0.001a |

|

| >2 | 41 (26.1) | 5 (6.0) | 5 (31.2) | 31 (53.4) |

|

|

| Unknown | 35 (22.3) | 11 (13.3) | 4 (25.0) | 20 (34.5) |

|

| Histological

type | NET-G1 | 82 (52.2) | 80 (96.4) | 1 (6.2) | 1 (1.7) |

<0.001a |

|

| NET-G2 | 13 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (81.2) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

| NEC-G3 | 54 (34.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (6.2) | 52 (89.7) |

|

|

| MANEC | 8 (5.1) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (6.2) | 5 (8.6) |

|

| Total number

of | ≤18 | 37 (23.6) | 11 (13.3) | 7 (43.8) | 19 (32.8) |

<0.001a |

| lymph node | >18 | 22 (14.0) | 6 (7.2) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (22.4) |

|

|

| Unknown | 98 (62.4) | 66 (79.5) | 6 (37.5) | 26 (44.8) |

|

| Positive number

of | ≤5 | 40 (25.5) | 12 (14.5) | 9 (56.2) | 19 (32.8) |

<0.001a |

| lymph node | >5 | 19 (12.1) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (6.2) | 13 (22.4) |

|

|

| Unknown | 98 (62.4) | 66 (79.5) | 6 (37.5) | 26 (44.8) |

|

| TNM stage | Tis | 4 (2.5) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (6.2) | 1 (1.7) |

<0.001a |

|

| I | 63 (40.1) | 59 (71.1) | 1 (6.2) | 3 (5.2) |

|

|

| II | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (6.2) | 3 (5.2) |

|

|

| III | 28 (17.8) | 8 (9.6) | 3 (18.8) | 17 (29.3) |

|

|

| IV | 43 (27.4) | 4 (4.8) | 7 (43.8) | 32 (55.2) |

|

|

| Unknown | 14 (8.9) | 9 (10.8) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (3.4) |

|

| Perineural

invasion | No | 145 (92.4) | 80 (96.4) | 14 (87.5) | 51 (87.9) | 0.085a |

|

| Yes | 12 (7.6) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (12.5) | 7 (12.1) |

|

| Vascular tumor

thrombus | No | 134 (85.4) | 79 (95.2) | 13 (81.2) | 42 (72.4) | 0.001a |

|

| Yes | 23 (14.6) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (18.8) | 16 (27.6) |

|

| AE1/AE3 | Negative | 86 (54.8) | 30 (36.1) | 7 (43.8) | 49 (84.5) | <0.001 |

|

| Positive | 71 (45.2) | 53 (63.9) | 9 (56.2) | 9 (15.5) |

|

| Postoperative

chemotherapy | No | 119 (75.8) | 80 (96.4) | 8 (50.0) | 31 (53.4) |

<0.001a |

|

| Yes | 38 (24.2) | 3 (3.6) | 8 (50.0) | 27 (46.6) |

|

| Postoperative

radiotherapy | No | 150 (95.5) | 82 (98.8) | 15 (93.8) | 53 (91.4) | 0.095a |

|

| Yes | 7 (4.5) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (6.2) | 5 (8.6) |

|

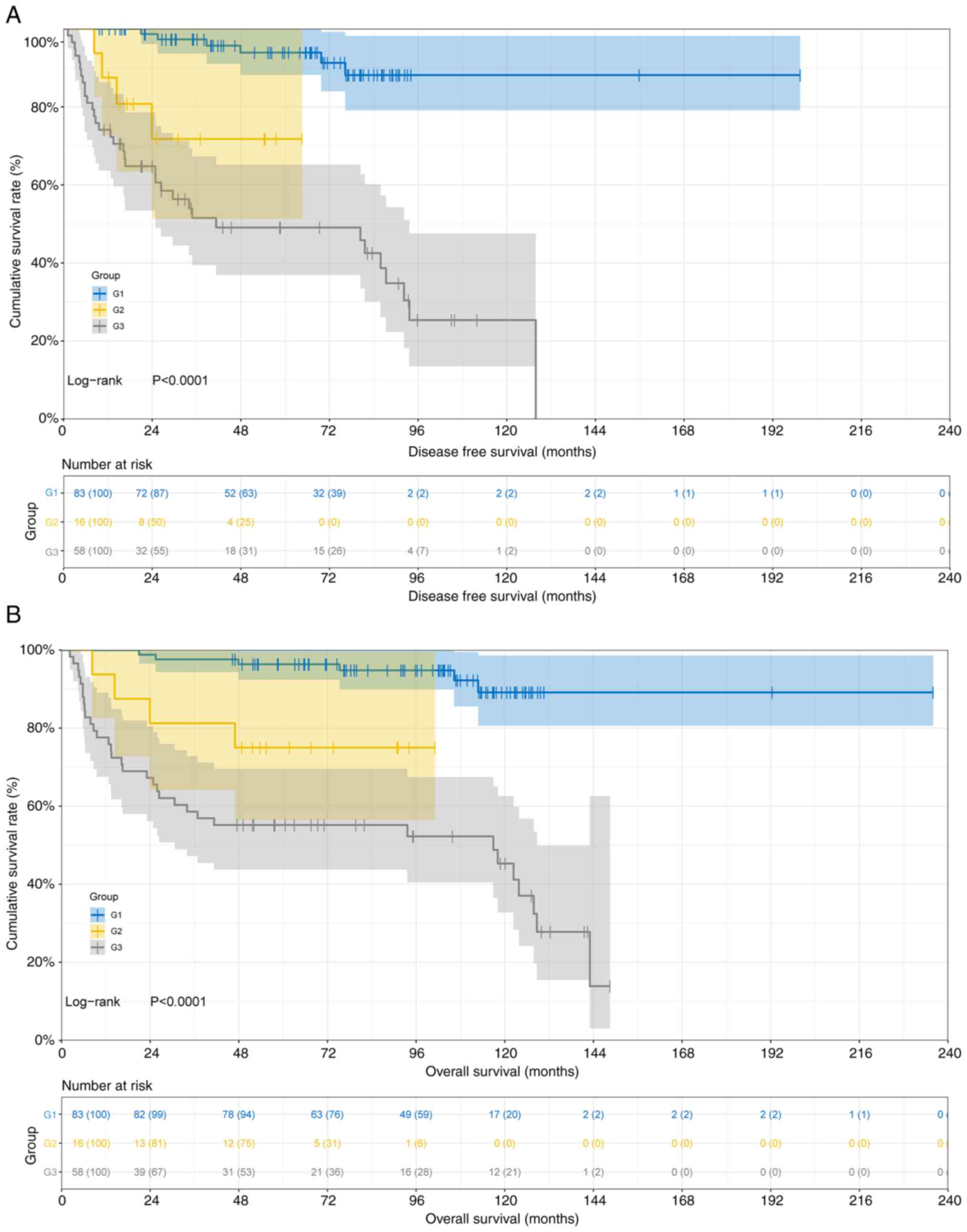

The mean DFS and OS durations stratified by

differentiation subtypes were as follows: i) In the low-grade (G1)

group, DFS was 65.73 months (95% CI, 55.33–71.43) and OS was 103.30

months (95% CI, 92.90–109.80); ii) in the intermediate-grade (G2)

group, DFS was 24.57 months (95% CI, 14.40–54.33) and OS was 58.58

months (95% CI, 46.97–90.87); and iii) in the high-grade (G3)

group, DFS was 25.67 months (95% CI, 16.23–34.83), OS was 51.90

months (95% CI, 26.43–71.10). Comparative analysis revealed

statistically significant differences in both DFS

(χ2=42.910; P<0.0001) and OS (χ2=41.220;

P<0.0001) among the three differentiation subtypes. The survival

curves are presented in Fig. 2.

Respectively, the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates

of DFS and OS stratified by pathological subtypes were as follows:

i) in the low-grade (G1) group, 100.0% (95% CI, 100.0–100.0), 97.3%

(95% CI, 93.7–100.0) and 93.9% (95% CI, 88.2–99.9) for DFS, and

100.0% (95% CI, 100.0–100.0), 97.6% (95% CI, 94.3–100.0) and 96.4%

(95% CI, 92.4–100.0) for OS; ii) in the intermediate-grade (G2)

group, 87.5% (95% CI 72.7–100.0), 71.8% (95% CI, 51.4–100.0) and

71.8% (95% CI, 51.4–100.0) for DFS, and 93.8% (95% CI, 82.6–100.0),

81.2% (95% CI, 64.2–100.0) and 75.0% (95% CI, 56.5–99.5) for OS;

and 3) in the high-grade (G3) group, 74.1% (95% CI, 63.7–86.3),

51.6% (95% CI, 39.5–67.3) and 49.1% (95% CI, 37.0–65.2) for DFS,

and 77.6% (95% CI, 67.6–89.1), 58.6% (95% CI, 47.2–72.8) and 55.2%

(95% CI, 43.7–69.6) for OS. The significant survival differences

(P<0.0001) among the differentiation grades emphasized that

high-grade (G3) tumors require aggressive therapeutic strategies,

while low-grade (G1) tumors may benefit from less intensive

interventions.

Related prognostic factors identified

by Cox regression analysis

According to univariate Cox regression analysis,

BMI, age, alcohol drinking, histological type and differentiation

were the related factors affecting DFS in patients CRNEC. The

multivariate analysis indicated that BMI, age and differentiation

were the potential prognostic factors affecting DFS in patients

with CRNEC (Table SII). Based on

univariate Cox regression analysis, sex, age, diabetes and

differentiation were significantly related to OS in patients with

CRNEC (Table SIII). The

multivariate analysis identified that sex, age and differentiation

were the potential prognostic factors affecting OS in patients with

CRNEC. The identification of age and differentiation as the

potential prognostic factors for DFS and OS provided a foundation

for risk stratification and personalized treatment planning in

patients with CRNEC.

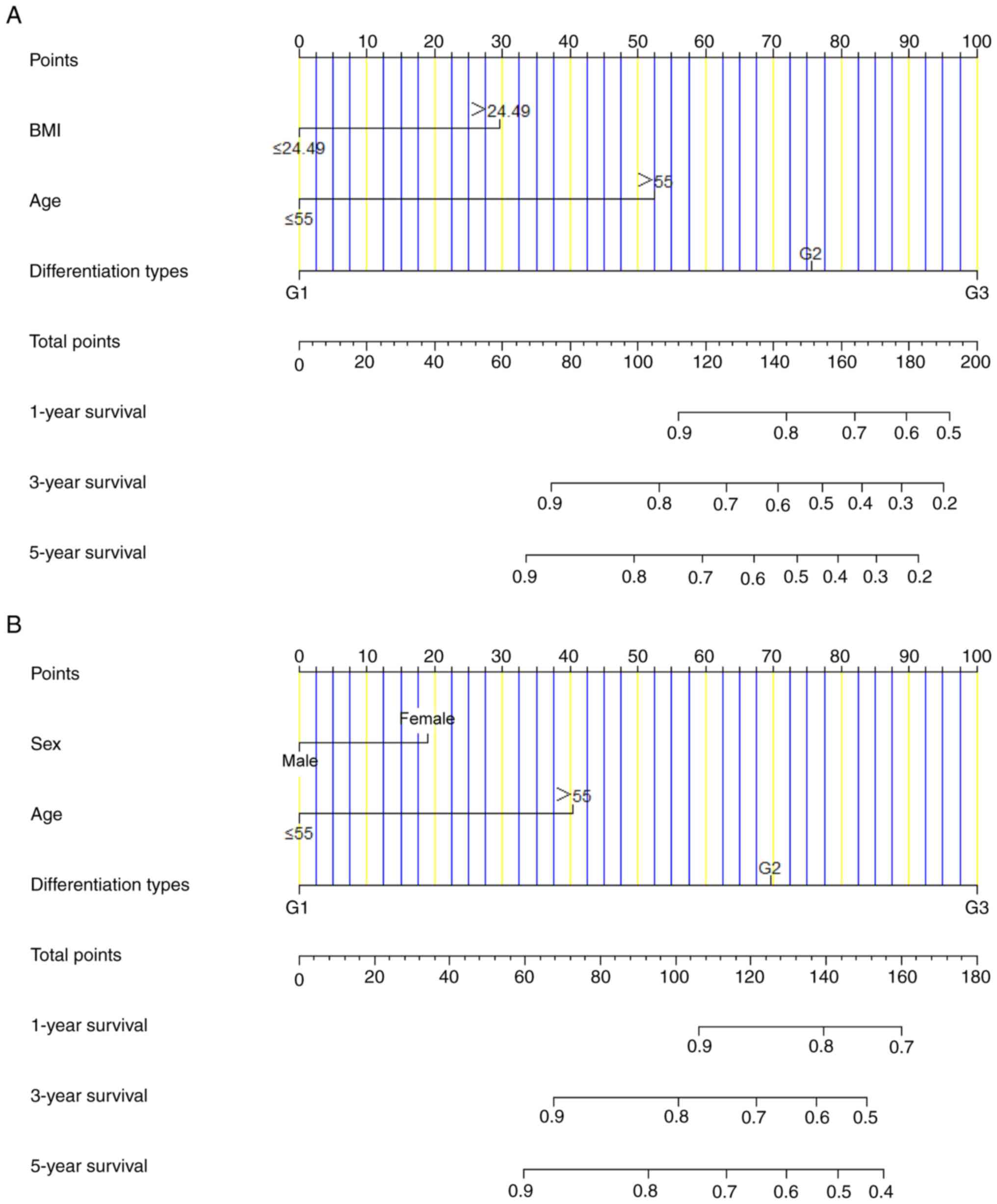

Establishing a prognostic

nomogram

Based on the univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analyses, nomograms were developed to predict 1-, 3- and

5-year DFS and OS in patients with CRNEC. The parameters with

P<0.05, including BMI, age and differentiation were selected via

multivariate analyses to construct a nomogram prognostic model of

DFS (Fig. 3A). The C-index for this

nomogram prognostic model predicting DFS was 0.843 (95% CI,

0.665–0.936). Moreover, the parameters with P<0.05, including

sex, age and differentiation were selected to comprise the nomogram

prognostic model of OS (Fig. 3B).

The C-index for this nomogram prognostic model predicting OS was

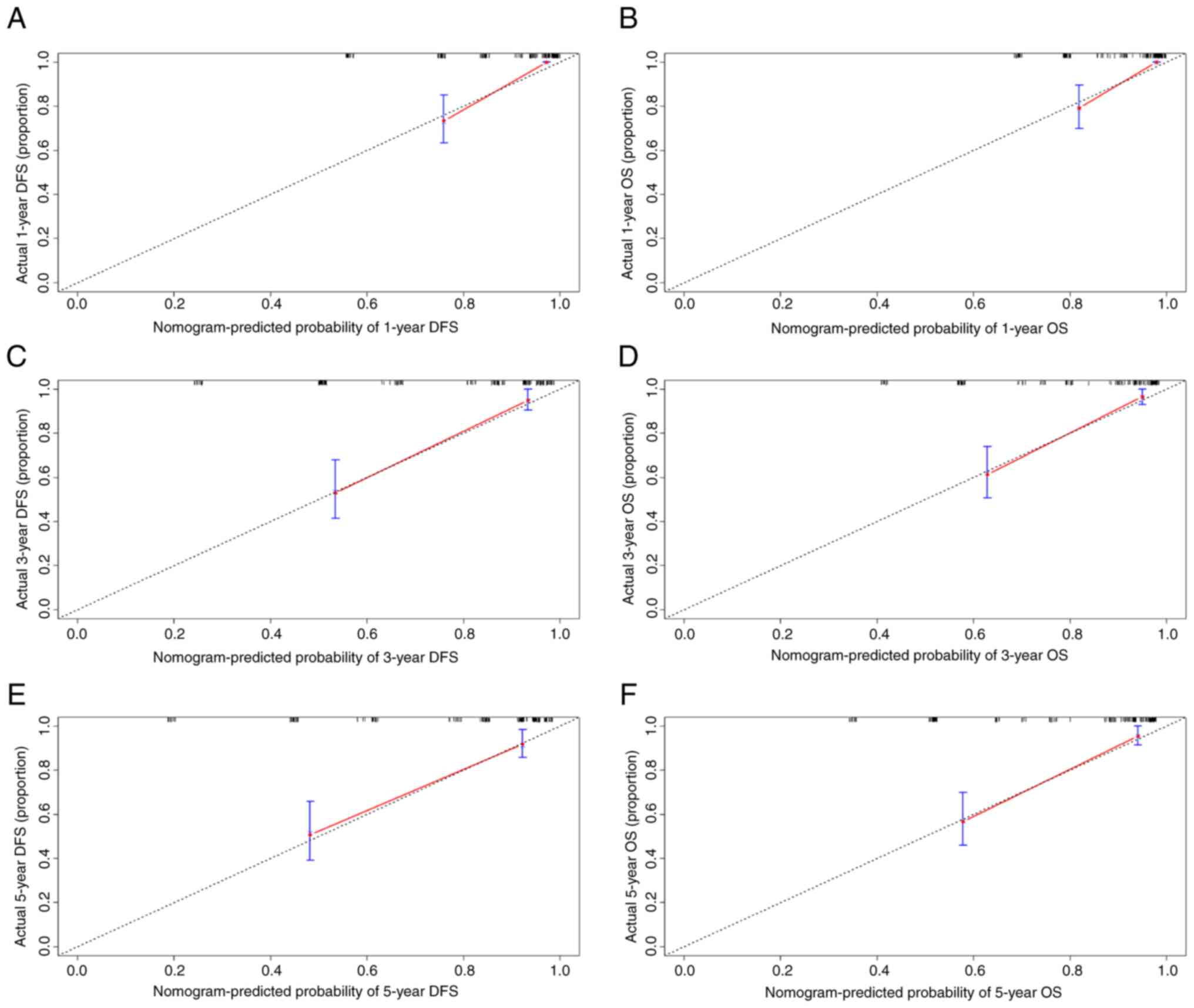

0.819 (95% CI, 0.644–0.919). Calibration curves with 1,000

bootstrap iterations quantified the precision of the nomograms in

estimating DFS and OS probabilities at 1-, 3- and 5-year using the

performance of the Cox regression model. The predicted and observed

survival probabilities showed strong concordance across different

time points (1-, 3- and 5-year), as evidenced by calibration curves

closely aligning with the 45° reference line (Fig. 4A-F). The high C-index values and

well-calibrated curves demonstrated the robust spredictive accuracy

of the nomogram, offering clinicians a practical tool for

individualized prognostic assessment.

Subgroup analysis for AE1/AE3

According to the results of Tables I and II, AE1/AE3 was significantly associated

with histological type and differentiation. There were 71 cases

with positive expression of AE1/AE3, and 86 cases with negative

expression of AE1/AE3; representative immunohistochemistry images

are shown in Fig. S1. The

clinicopathological characteristics of patients with CRNEC split

according to AE1/AE3 expression are detailed in Table SIV. Regarding the

clinicopathological characteristics of the patients, AE1/AE3

expression was associated with gross type, tumor size, histological

type, differentiation, TNM stage and postoperative chemotherapy

(P<0.05).

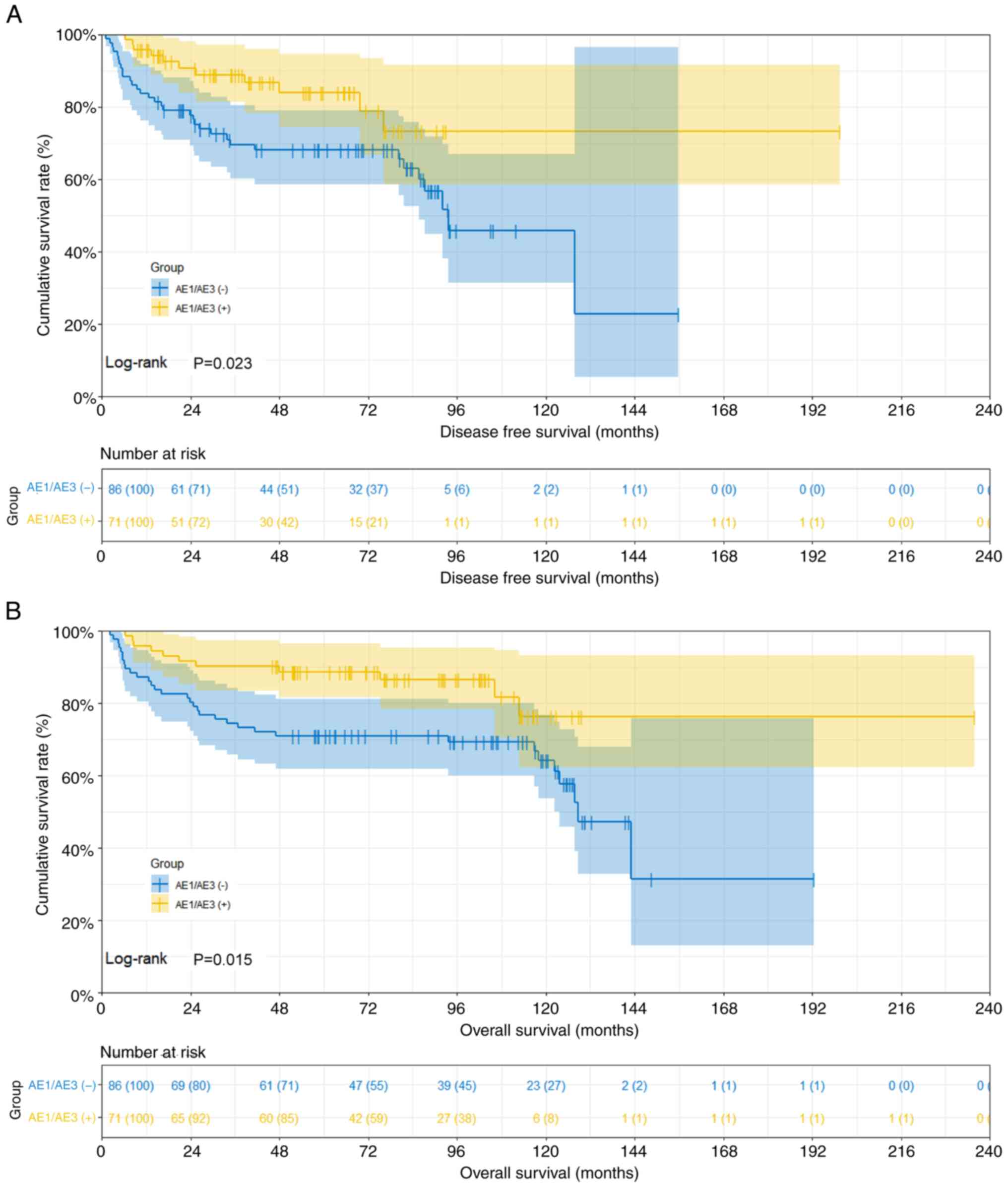

The mean DFS and OS durations stratified by AE1/AE3

expression were as follows: i) In patients with AE1/AE3(−), DFS was

40.57 months (95% CI, 31.00–56.37) and OS was 79.23 months (95% CI,

67.53–96.33); ii) in patients with AE1/AE3(+), DFS was 53.02 months

(95% CI, 29.60–70.23) and OS was 92.25 months (95% CI,

63.03–106.80). Comparative analysis revealed statistically

significant differences in both DFS and OS among AE1/AE3 expression

groups (DFS: χ2=5.162, P=0.023; OS: χ2=6.681,

P=0.015). The survival curves are presented in Fig. 5.

The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of DFS and OS

stratified by AE1/AE3 expression were as follows: i) In patients

with AE1/AE3(−), 83.7% (95% CI, 76.3–91.9), 69.5% (95% CI,

60.2–80.4) and 68.0% (95% CI, 58.5–79.1) for DFS, and 87.2% (95%

CI, 80.4–94.6), 74.4% (95% CI, 65.7–84.2) and 70.9% (95% CI,

62.0–81.2) for OS, respectively; and ii) in patients with

AE1/AE3(+), 95.8% (95% CI, 91.2–100.0), 88.9% (95% CI, 81.4–97.1)

and 83.8% (95% CI, 74.4–94.6) for DFS, and 95.8% (95% CI,

91.2–100.0), 90.1% (95% CI, 83.5–97.3) and 88.7% (95% CI,

81.6–96.4) for OS, respectively (Fig.

5). The association of AE1/AE3 positivity with prolonged

survival suggested its potential role as a favorable biomarker for

tumor biology, which could aid in diagnostic and therapeutic

decision-making.

Subgroup analysis for age

Based on the univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analyses, age was indicated as a potential prognostic

factor affecting DFS and OS in patients with CRNEC. The median age

of enrolled patients was 55 years; according to the median age,

there were 75 patients aged ≤55 years and 82 cases patients aged

>55 years. Notably, patients >55 years old had a poorer

prognosis than those aged ≤55 years (DFS: χ2=11.620;

P=0.0007; OS: χ2=12.450; P=0.0005) (Fig. S2).

Discussion

CRNEC is a relatively rare malignancy, accounting

for 20–30% of all gastroenteropancreatic NENs (GEP-NENs) and <2%

of all colorectal cancers. A majority of CRNECs are non-functional,

exhibiting non-specific symptomatology indistinguishable from

colorectal adenocarcinoma, including abdominal pain, altered bowel

habits and hematochezia (15).

CRNECs are typically more aggressive than conventional colorectal

carcinoma, with higher rates of metastasis and poorer survival

outcomes (16). With advancements

in diagnostic technologies, the improvement of living standards and

increased health awareness, the detection rate of CRNEC has notably

risen in recent years (17). The

diagnosis of CRNEC primarily relies on colonoscopy, biopsy and

pathology after surgery, with definitive confirmation requiring

immunohistochemical evidence of neuroendocrine markers, such as

Syn, chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase (18). Surgical resection is the main

treatment for CRNEC, while chemotherapy serves a role as a crucial

adjuvant treatment, particularly for tumors with Ki-67 >5%,

utilizing regimens including doxorubicin, etoposide and

fluorouracil (19). By contrast,

conventional colorectal carcinoma is primarily managed with surgery

and chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFOX, CAPEOX or FOLFIRI

(20).

The present study analyzed the clinicopathological

characteristics of 157 cases of CRNEC, including 32 cases of

colonic NETs and 125 cases of rectal NETs. According to data from

China, rectal NENs are the predominant type of gastrointestinal

NETs, and the incidence rate has increased in recent years

(21). Studies have also

demonstrated that tumor stage and tumor size are the critical

prognostic factors for CRNEC (22,23).

According to the 5th edition of the WHO Classification of Digestive

System Tumors (2019), NETs can be classified as NET-G1, NET-G2,

NEC-G3 and MANEC (24). In the

present study, of all pathological types included, there were 82

cases graded as NET-G1, 13 cases of NET-G2, 54 cases of NEC-G3 and

eight cases of MANEC. The results of the current study demonstrated

that the different pathological types were associated with age,

gross types, differentiation and AE1/AE3. Additional analysis of

prognostic outcomes in patients with CRNEC indicated that the

NET-G1 pathological subtype was associated with significantly

prolonged DFS and OS, as well as improved prognosis, when compared

with the other pathological subtypes. The results of the present

study align with prior evidence, which demonstrated that patients

with pancreatic NET-G1/2 had a significantly longer survival time

compared with that of patients with poorly differentiated NEC

(P=0.002) (25). Punekar et

al (26) revealed that patients

with NET-G1/2 had an improved OS rate than those with NEC-G3 and

MANEC in colorectal NETs in the SEER database.

The potential mechanisms are that NEC-G3 and MANEC

are associated with larger tumors with more aggressive histological

features, and more metastatic sites compared with NET-G1/G2. NECs

are genomically distinct entities characterized by obligate

inactivation of the TP53 and Rb/p16 tumor suppressor pathways

(27). Tanaka et al

(28) observed that MANEC, albeit

rare, has a highly aggressive clinical course, and that

curative-intent surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy could markedly

prolong survival in localized cases.

The present study also analyzed the

clinicopathological features among the various differentiation

types in patients with CRNEC. Regarding differentiation types,

there were 83 low-grade (G1) cases, 16 intermediate-grade (G2)

cases and 58 high-grade (G3) cases. The present study revealed that

the differentiation types were related to age, primary site,

histological type, TNM stage and AE1/AE3 expression. Subsequent

analysis of the outcomes of patients with CRNEC revealed that the

low-grade (G1) subtype was associated with markedly extended DFS

and OS durations and greater prognostic results compared with THE

alternative differentiation classifications. Pommergaard et

al (29) demonstrated that

surgical resection of primary tumors provided favorable long-term

survival in locoregional high-grade GEP-NENs and mixed

neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs). Holmager

et al (30) demonstrated

that high-grade MiNENs have a neuroendocrine and a

non-neuroendocrine component that is associated with aggressive

biological behavior and unfavorable clinical outcomes. Another

study indicated that high-grade CRNECs exhibit rapid disease

progression, and are characterized by limited therapeutic

responsiveness and low survival rates (31). Moreover, prognostic analysis

revealed that patients with high-grade NEC without metastatic

disease have an adenocarcinoma component within their tumor, or

their response to chemotherapy is associated with modestly improved

clinical outcomes. Alese et al (32) also demonstrated that patients with

high-grade pancreatic NETs exhibited a significantly shorter median

OS (6.0 months) than those with other high-grade gastrointestinal

NECs (9.9 months). The survival data of the present study indicated

that the prognosis of high-grade (G3) tumors was the poorest

compared with low-grade (G1) or intermediate-grade (G1) tumors,

which was consistent with the aforementioned studies.

Notably, the present study revealed that AE1/AE3

expression was related to histological type and differentiation.

According to immunohistochemistry, there were 71 cases with

positive expression of AE1/AE3 and 86 cases with negative

expression of AE1/AE3 in the current study. Subsequent analysis of

the outcomes of patients with CRNEC revealed that AE1/AE3(+)

expression was associated with markedly extended DFS and OS

durations and improved prognostic results compared with AE1/AE3 (−)

expression. AE1/AE3 expression was associated with

well-differentiated CRNEC and may indicate favorable outcomes,

while loss of expression was frequently observed in poorly

differentiated CRNEC. An AE1/AE3 cocktail is the gold standard for

detecting cytokeratin expression in immunohistochemistry. AE1

recognizes high (K10, K14-16) and low (K19) molecular weight

keratins, while AE3 targets type II high (K1-6) and low (K7-8)

molecular weight keratins, and their downregulated expression is a

hallmark of high-grade carcinomas with aberrant differentiation

(33). Badzio et al

(34) demonstrated that patients

with small cell lung cancer undergoing pulmonary resection with

high AE1/AE3 immunoreactivity demonstrated a superior median OS

compared with patients with low expression (24.7 months vs. 13.8

months; P=0.019). Vasilevska et al (35) revealed that AE1/AE3 immunoreactivity

was predominantly observed in moderately differentiated endometrial

carcinoma, and the clinical implication of AE1/AE3 might aid in the

diagnosis of early-stage endocrine carcinoma as well as aiding the

detection of micrometastases, leading to improved survival

outcomes. In addition, this previous study demonstrated that

AE1/AE3 negativity coincided with epithelial-mesenchymal transition

activation and aggressive behavior of the carcinoma, such as rapid

cell proliferation and metastasis (35). Although this has, to the best of our

knowledge, not yet been studied in CRNEC, similar mechanisms may

explain the observation in the present study that negative

expression of AE1/AE3 in tumors indicated higher rates of vascular

invasion and metastasis.

The present study investigated the potential

prognostic factors of CRNEC and developed a prognostic nomogram

model for DFS and OS. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed

that BMI, age and differentiation were the potential independent

predictors of DFS, while sex, age and differentiation emerged as

significant determinants of OS. Differentiation grade stratifies

survival, with high-grade (G3) tumors predicting adverse outcomes

and reduced OS. Moreover, the present study constructed a

multivariate-derived prognostic nomogram that could provide higher

accuracy in predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year survival probabilities

than single conventional prognostic markers. Calibration analysis

demonstrated agreement between predicted and observed 1-, 3- and

5-year survival probabilities in patients with CRNEC, with the

model-derived curve closely aligning with the ideal reference

line.

Multivariate modeling confirmed age as a potential

prognostic factor for DFS and OS in CRNEC. In the present study,

patients >55 years old had poorer prognosis than those ≤55 years

(P<0.001). Lal et al (36) demonstrated that individuals with

large bowel carcinoids were more likely to be elderly (age >65

years) (OR 2.17; CI, 2.05–2.31; P<0.0001), and age was

identified as a potential risk factor (35). Another study also indicated that age

≥56 years (HR, 7.434; 95% CI, 1.334–41.443; P=0.022) was an

independent prognostic factor via multivariate analyses in

colorectal NETs (37).

Age-dependent therapeutic disparities likely contribute to these

findings, as younger patients demonstrated greater utilization of

different treatment modalities.

The present study had several limitations that

should be acknowledged. Firstly, this investigation employed a

single-center retrospective design, and thus has some inherent

limitations, including potential selection bias and residual

confounding factors despite multivariate adjustments. Secondly, the

conducted nomograms were derived from a restricted set of

covariates and require external validation in independent cohorts

to confirm generalizability. Thirdly, the low incidence of CRNEC

inherently limited the cohort size. Therefore, prospective

multicenter validation studies with larger samples are warranted to

confirm these preliminary findings.

In conclusion, the present study established a

nomogram to predict the prognosis of patients with CRNEC with good

prediction efficacy. Adverse prognostic factors for predicting DFS

and OS time include being aged >55 years and being diagnosed

with high-grade differentiation subtypes (including G2 and G3).

High-grade CRNECs represent highly aggressive malignancies

associated with an unfavorable clinical outcome. In addition,

AE1/AE3 may be helpful for improving the diagnostic accuracy of

patients with CRNEC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL conceptualized and supervised the study, and was

project administrator. MD and SS acquired, analyzed and interpreted

the data. XL designed the methodology. MD and HL wrote the original

draft, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. MD and HL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol received approval from the

Institutional Review Board of Harbin Medical University Cancer

Hospital (approval no. 82271845) and adhered strictly to the

ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and

subsequent amendments. Before treatment, the enrolled patients

provided written informed consent for the use of their data in

research.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mollazadegan K, Welin S and Crona J:

Systemic treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 22:682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary

C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A and Evans

DB: One hundred years after ‘carcinoid’: Epidemiology of and

prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the

United States. J Clin Oncol. 26:3063–3072. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wu IC, Chu YY, Wang YK, Tsai CL, Lin JC,

Kuo CH, Shih HY, Chung CS, Hu ML, Sun WC, et al:

Clinicopathological features and outcome of esophageal

neuroendocrine tumor: A retrospective multicenter survey by the

digestive endoscopy society of Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc.

120:508–514. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, : The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Panzuto F, Andrini E, Lamberti G, Pusceddu

S, Rinzivillo M, Gelsomino F, Raimondi A, Bongiovanni A, Davì MV,

Cives M, et al: Sequencing treatments in patients with advanced

well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET): Results

from a large multicenter Italian cohort. J Clin Med. 13:20742024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sultana Q, Kar J, Verma A, Sanghvi S, Kaka

N, Patel N, Sethi Y, Chopra H, Kamal MA and Greig NH: A

comprehensive review on neuroendocrine neoplasms: Presentation,

pathophysiology and management. J Clin Med. 12:51382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shia J, Tang LH, Weiser MR, Brenner B,

Adsay NV, Stelow EB, Saltz LB, Qin J, Landmann R, Leonard GD, et

al: Is nonsmall cell type high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of

the tubular gastrointestinal tract a distinct disease entity? Am J

Surg Pathol. 32:719–731. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ho YH, Hsu CY, Yau Li AF and Liang WY:

Colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma and mixed

neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm: Prognostic factors and

PD-L1 expression. Hum Pathol. 145:80–85. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tessier-Cloutier B, Kang EY, Alex D,

Stewart CJR, McCluggage WG, Köbel M and Lee CH: Endometrial

neuroendocrine carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma are

distinct entities with overlap in neuroendocrine marker expression.

Histopathology. 81:44–54. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gudmundsdottir H, Habermann EB, Vierkant

RA, Starlinger P, Thiels CA, Warner SG, Smoot RL, Truty MJ,

Kendrick ML, Halfdanarson TR, et al: Survival and symptomatic

relief after cytoreductive hepatectomy for neuroendocrine tumor

liver metastases: Long-term follow-up evaluation of more than 500

patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:4840–4851. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Heetfeld M, Chougnet CN, Olsen IH, Rinke

A, Borbath I, Crespo G, Barriuso J, Pavel M, O'Toole D and Walter

T; Other Knowledge Network Members, : Characteristics and treatment

of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:657–664. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mischel AM and Rosielle DA: Eastern

cooperative oncology group performance status #434. J Palliat Med.

25:508–510. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Perren A, Couvelard A, Scoazec JY, Costa

F, Borbath I, Delle Fave G, Gorbounova V, Gross D, Grossma A, Jense

RT, et al: Antibes consensus conference participants. Enets

consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine

tumors: Pathology: Diagnosis and prognostic stratification.

Neuroendocrinology. 105:196–200. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Emile SH, Horesh N, Garoufalia Z, Gefen R,

Wignakumar A and Wexner SD: Predictors of lymph node metastasis and

survival in radically resected rectal neuroendocrine tumors: A

surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database

analysis. Surgery. 176:668–675. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Donofrio CA, Pizzimenti C, Djoukhadar I,

Kearney T, Gnanalingham K and Roncaroli F: Colorectal carcinoma to

pituitary tumour: Tumour to tumour metastasis. Br J Neurosurg.

37:1367–1370. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zheng K, Duan J, Wang R, Chen H, He H,

Zheng X, Zhao Z, Jing B, Zhang Y, Liu S, et al: Deep learning model

with pathological knowledge for detection of colorectal

neuroendocrine tumor. Cell Rep Med. 5:1017852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sabella G, Centonze G, Lagano V, Scardino

A, Belli F, Garzone G, Pardo C, Galbiati D, Pusceddu S, Mangogna A,

et al: Unveiling the prognostic role of synaptophysin in

conventional colorectal carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 15:632–647.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Reina JJ, Serrano R, Codes M, Jiménez E,

Bolaños M, Gonzalez E and Sevilla I: Second primary malignancies in

patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Transl Oncol. 16:921–926.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao W, Jin L, Chen P, Li D, Gao W and

Dong G: Colorectal cancer immunotherapy-Recent progress and future

directions. Cancer Lett. 545:2158162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang J, Chen H, Zhang J, Wang S, Guan Y,

Gu W, Li J, Zhang X, Li J, Wang X, et al: Molecular features of

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: A comparative

analysis with lung neuroendocrine carcinoma and digestive

adenocarcinomas. Chin J Cancer Res. 36:90–102. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gallo C, Rossi RE, Cavalcoli F, Barbaro F,

Boškoski I, Invernizzi P and Massironi S: Rectal neuroendocrine

tumors: Current advances in management, treatment, and

surveillance. World J Gastroenterol. 28:1123–1138. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chauhan A, Chan K, Halfdanarson TR,

Bellizzi AM, Rindi G, O'Toole D, Ge PS, Jain D, Dasari A, Anaya DA,

et al: Critical updates in neuroendocrine tumors: Version 9

American joint committee on cancer staging system for

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J Clin.

74:359–367. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yoshida T, Kamimura K, Hosaka K, Doumori

K, Oka H, Sato A, Fukuhara Y, Watanabe S, Sato T, Yoshikawa A, et

al: Colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma: A case report and review

of the literature. World J Clin Cases. 7:1865–1875. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rindi G, Mete O, Uccella S, Basturk O, La

Rosa S, Brosens LAA, Ezzat S, de Herder WW, Klimstra DS, Papotti M

and Asa SL: Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of

neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 33:115–154. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Basturk O, Yang Z, Tang LH, Hruban RH,

Adsay V, McCall CM, Krasinskas AM, Jang KT, Frankel WL, Balci S, et

al: The high-grade (WHO G3) pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

category is morphologically and biologically heterogenous and

includes both well differentiated and poorly differentiated

neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 39:683–690. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Punekar SR, Kaakour D, Masri-Lavine L,

Hajdu C, Newman E and Becker DJ: Characterization of a novel entity

of G3 (high-grade well-differentiated) colorectal neuroendocrine

tumors (NET) in the SEER database. Am J Clin Oncol. 43:846–849.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yachida S, Vakiani E, White CM, Zhong Y,

Saunders T, Morgan R, de Wilde RF, Maitra A, Hicks J, Demarzo AM,

et al: Small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the

pancreas are genetically similar and distinct from

well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Surg

Pathol. 36:173–184. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tanaka T, Kaneko M, Nozawa H, Emoto S,

Murono K, Otani K, Sasaki K, Nishikawa T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, et

al: Diagnosis, assessment, and therapeutic strategy for colorectal

mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology.

105:426–434. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pommergaard HC, Nielsen K, Sorbye H,

Federspiel B, Tabaksblat EM, Vestermark LW, Janson ET, Hansen CP,

Ladekarl M, Garresori H, et al: Surgery of the primary tumour in

201 patients with high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

and mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. J

Neuroendocrinol. 33:e129672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Holmager P, Langer SW, Kjaer A, Ringholm

L, Garbyal RS, Pommergaard HC, Hansen CP, Federspiel B, Andreassen

M and Knigge U: Surgery in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic

neuroendocrine carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors G3 and high grade

mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. Curr Treat

Options Oncol. 23:806–817. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Smith JD, Reidy DL, Goodman KA, Shia J and

Nash GM: A retrospective review of 126 high-grade neuroendocrine

carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Ann Surg Oncol. 21:2956–2962.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alese OB, Jiang R, Shaib W, Wu C, Akce M,

Behera M and El-Rayes BF: High-grade gastrointestinal

neuroendocrine carcinoma management and outcomes: A national cancer

database study. Oncologist. 24:911–920. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ordóñez NG: Broad-spectrum

immunohistochemical epithelial markers: A review. Hum Pathol.

44:1195–215. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Badzio A, Czapiewski P, Gorczyński A,

Szczepańska-Michalska K, Haybaeck J, Biernat W and Jassem J:

Prognostic value of broad-spectrum keratin clones AE1/AE3 and

CAM5.2 in small cell lung cancer patients undergoing pulmonary

resection. Acta Biochim Pol. 66:111–114. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Vasilevska D, Rudaitis V, Lewkowicz D,

Širvienė D, Mickys U, Semczuk M, Obrzut B and Semczuk A: Expression

patterns of cytokeratins (CK7, CK20, CK19, CK AE1/AE3) in atypical

endometrial hyperplasia coexisting with endometrial cancer. Int J

Mol Sci. 25:90842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lal P, Saleh MA, Khoudari G, Gad MM,

Mansoor E, Isenberg G and Cooper GS: Epidemiology of large bowel

carcinoid tumors in the USA: A population-based national study. Dig

Dis Sci. 65:269–275. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zheng X, Wu M, Er L, Deng H, Wang G, Jin L

and Li S: Risk factors for lymph node metastasis and prognosis in

colorectal neuroendocrine tumours. Int J Colorectal Dis.

37:421–428. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|