Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common

malignancies in men worldwide. According to the 2024 data from the

American Cancer Society, PCa is the second leading cause of

mortality in men, after lung cancer (1). Annually, there are ~1.5 million cases

of PCa and it results in 396,700 mortalities globally (2). With increases in the global and aging

populations, PCa has become a notable public health challenge in

men worldwide (3). The incidence of

PCa in China has markedly increased (4–6) and it

has become one of the most common types of cancer in men in China.

In 2020, in China, ~120,000 novel cases of PCa were reported, which

accounted for 8.16% of cancer diagnoses in men. The number of PCa

mortalities was ~50,000 making up 13.61% of cancer-related

mortalities among men (7,8).

The 5- and 10-year survival rates for PCa depend on

the stage and grade of the cancer at diagnosis. For localized or

regional PCa, when the cancer is confined to the prostate or nearby

areas, the 5-year relative survival rate is ~100%. For metastatic

PCa, in which the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body,

the 5-year survival rate is markedly reduced, ~37% (9). Recurrence is a concern with PCa,

especially in advanced cases with increasing prostate-specific

antigen (PSA) levels often indicating recurrence within 5–10 years

in 20–30% of men treated for PCa. Recurrence is more likely in

cases with aggressive tumor characteristics, increased initial PSA

levels and advanced stage at diagnosis (10).

The high risk of PCa is primarily attributed to its

aggressive metastasis. In cases where cancer types are hidden, it

is difficult for clinicians to diagnose and treat the disease

early. In several cases, by the time PCa is diagnosed, tumor

tissues have metastasized to areas outside the prostate, such as in

the bone (11,12). PCa is associated with multiple

genomic alterations, which result in a high degree of tumor

heterogeneity. However, the specific mechanism underlying its

malignancy remains unclear (13).

Current progress in medical diagnostic imaging, surgery,

chemotherapy and radiotherapy has improved the effective diagnosis,

treatment and management of PCa. Androgen-blocking therapy (ADT),

which targets androgen receptors (ARs), is the first-line treatment

option in clinical practice, further to surgical excision. However,

~2 years of administering ADT to patients with advanced PCa results

in the development of castration-resistant PCa; which is typically

accompanied by elevated serum testosterone and PSA levels (14). Therefore, exploring the internal

mechanisms and therapeutic targets of PCa and developing

corresponding drugs is key to improve the survival and prognosis of

patients and reduce the medical burden of searching for early

diagnostic markers to supplement the diagnostic shortcomings of

PSA.

Cytokines serve an important role in the development

of cancer (15). Further to

abnormal DNA methylation, histone post-translational modifications

(PTMs) and changes in chromatin modification patterns are

associated with carcinogenesis; the latter two have revealed to be

key factors in cancer-related pathways (16). Histone methylation serves a

regulatory role in various cancer cells; this process is catalyzed

by histone methyltransferases (HMTs), which comprise different

families of enzymes that methylate specific residues to alter gene

transcription. For example, lysine HMT (protein lysine

methyltransferase) methylates lysine residues, while histone

arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) methylates arginine. The only

type III PRMT among the nine members of the PRMT family is PRMT7,

which contains only monomethyl arginine (17–22).

PTMs regulated by PRMT7 and its proteins are

associated with tumor growth and metastasis (23). Specifically, PRMT7 expression is

increased in clear cell renal cell carcinoma tissues and leads to

renal cell carcinoma growth through the β-catenin/c-Myc axis

(24). The upregulation of PRMT7

expression may promote breast cancer cell invasion by regulating

MMP9 expression (25). Research on

PRMT7 in breast cancer has indicated its potential as a biomarker

and therapeutic target (26,27).

Although PRMT7 has not been thoroughly studied in other cancer

types, as a member of the PRMT family, it is known to regulate

histone methylation, a PTM associated with cancer (28,29).

In particular, as a member of the PRMT family, PRMT5 can promote

the progression of PCa by influencing key regulatory factors, such

as the AR. This influence on AR, a key regulator in PCa, suggests

that PRMT5 serves a notable role in cancer development, which

highlights its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention

(30,31); therefore, PRMT7 is likely to serve a

key role as an epigenetic regulator in PCa and ultimately affect

tumor progression and prognosis.

In 2014, Vieira et al (32) studied the expression levels of

partial HMT or demethylase in PCa and its relationship with the

occurrence and progression of cancer. Based on this and other

previous studies (28–31) on the PRMT family and malignant

tumors, the molecular mechanism of action of the PRMT7 in PCa were

investigated. By validating the expression level of PRMT7 in

prostate cancer cells and tissues, its correlation with

clinicopathological features and patient survival was analyzed to

further elucidate the potential mechanisms by which PRMT7 promotes

prostate cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

In the present study, 159 PCa samples were

prospectively collected from patients diagnosed at the Affiliated

Hospital of Jiangnan University (Wuxi, China) between December 2023

and June 2024. The tissue samples were obtained through standard

hospital procedures. Patients were evaluated through clinical and

histological analyses. The present study strictly adhered to the

following predefined inclusion criteria: i) Histopathologically

confirmed primary prostate adenocarcinoma [International Society of

Urological Pathology (ISUP) grade ≥2]; ii) no prior history of

radiotherapy or systemic therapy; and iii) availability of matched

tumor-normal paired tissue samples for genomic analysis. The

exclusion criteria comprised cases with metastasis at diagnosis (to

avoid confounding by advanced disease biology) and specimens that

did not meet tissue quality standards (RNA integrity number >7).

The age distribution of the cohort (median, 68 years; range, 52–81

years), PSA levels and ISUP grades mirrored regional epidemiology.

The tissue samples were collected for tissue microarray analysis

and the correlation between PRMT7 and the age of the patients,

Gleason score (33), PSA levels and

TNM stage (34) in PCa were

analyzed. Then, seven pairs of matched PCa clinical samples

detected using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

were also derived from the aforementioned tissues, with normal

tissue samples collected 5 cm away from the tumor margin serving as

negative controls. The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University (approval

no. LS2023099; Wuxi, China). The present study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient included

in the present study signed a written informed consent form prior

to sample collection.

Bioinformatics analysis

PRMT7 expression data were downloaded from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) online database (http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). R software

(version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org) and SPSS (version 17.0; SPSS

Inc.) were used to analyze and process all data.

Immunohistochemistry staining and

scoring

Paraformaldehyde (4%) was used to fix collected

tissue samples at room temperature (25°C) for 24 h.

Paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4-µm-thick sections. Tissue

sections were dewaxed, hydrated, then permeabilized with 0.5%

Triton X-100 at room temperature (25°C) for 10 min, blocked with 3%

H2O2 (25°C) for 30 min and 10% goat serum

(25°C) for 30 min. Next, the samples were incubated with antibodies

against PRMT7 from Merck KGaA (1:50; cat. no. HPA044241) at 4°C

overnight. Thereafter, images of the sections were taken using an

Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus

Corporation). The subsequent steps were performed using the

GTVision III Detection System/Mo&Rb (Gene Tech Co., Ltd.)

(35,36). Immunohistochemistry results for

healthy individuals were selected from the Human Protein Atlas

database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000132600-PRMT7/tissue/prostate#).

Cell culture

Human PCa cell lines PC3, DU145, LNCAP, 22RV1 and

WPMY-1 were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of

Science. DU145 and WPMY-1 cells were cultured in DMEM (Cytiva)

supplemented with 10% FBS (Shenzhen Aipno Biomedical Technology

Co., Ltd.). PC3, LNCAP and 22RV1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640

(Cytiva) medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Shenzhen Aipno

Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.). All cells were incubated at 37°C

with 5% CO2.

RT-qPCR

RNA extraction from PC3, DU145, LNCAP, 22RV1 and

WPMY-1 cells (each sample used 3×106 cells) was carried

out using a FastPure® Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation

Kit V2 (cat. no. RC112-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA

using a HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper)

(cat. no. R323-01; Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd.). The primer sequences

used for GAPDH and PRMT7 are listed in Table SI. qPCR was carried out in an

Applied Biosystems 7500 PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

using a ChamQ Universal SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (cat. no.

Q711-02/03, Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd.). The RT-qPCR protocol

consisted of: Initiation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles

at 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Relative quantification of

gene expression was carried out using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(35), with GAPDH as the endogenous

control. Primer efficiencies were validated to be between 95–105%

prior to analysis. The results were analyzed using a previously

reported method (35).

Plasmid transfection

Small interfering (si)PRMT7 was designed based on

the PRMT7 (NM_019023.5; Infection, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_019023.5)

target sequence. The sequences of the specific genes used in the

present study were as follows: PRMT7-siRNA (43684–1) sense (S),

5′-CACAUCAUGGACGACAUGAUU-3′ and antisense (AS),

5′-AAUCAUGUCGUCCAUGAUGUG-3′; PRMT7-siRNA (43685–1) S,

5′-GCUAACCACUUGGAAGAUAAA-3′ and AS, 5′-UUUAUCUUCCAAGUGGUUAGC-3′;

PRMT7-siRNA (43686–1) S, 5′-CGAUGACUACUGCGUAUGGUA-3′ and AS,

5′-UACCAUACGCAGUAGUCAUCG-3′; non-silencing siRNA S,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′ and AS, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA-3′. They

were synthesized and cloned into GV248 (11.5 kb) vector with

BsmBI sites (purchased from Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.),

recombinant vector was detected by DNA sequencing. The final

products were then transfected into Escherichia coli

(>1×108 cfu/µg; purchased from Shanghai Genechem Co.,

Ltd.). The PRMT7-siRNA plasmid was then isolated/purified with the

EndoFree Plasmid Mega Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany; Cat. #12381).

Briefly, 4×105 cells were seeded in each well of a

6-well plate. Upon reaching 60–70% confluency, transfections were

carried out using Lipofectamine® 3000 reagent (cat. no.

L3000150, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) Cells were seeded in

6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and

cultured overnight to reach 70–80% confluency. For each well, 2.5

µg of plasmid DNA and 5 µl P3000™ were diluted in 125 µl of

Opti-MEM® Reduced-Serum Medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and mixed gently. Separately, 7.5 µl of

Lipofectamine™ 3000 was diluted in 125 µl of Opti-MEM®.

The diluted DNA was then combined with the diluted

Lipofectamine® 3000 (1:1 ratio) and incubated for 15 min

at room temperature to form DNA-lipid complexes. The mixture was

added dropwise to the cells, followed by gentle swirling. The cells

were cultured at 37°C for an additional 48 h. The transfection

efficiency was >80% based on green protein fluorescence.

Other assays

Western blot analysis, cell proliferation and colony

formation assays, apoptosis analysis and cell cycle detection,

wound healing, cell migration and invasion assays were carried out

as previously described (35,36).

The antibodies that were used are: anti-PRMT7 (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab181214; Abcam), anti-GAPDH (1:2,500; cat. no. ab9485; Abcam),

anti-β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. GB12001; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology); anti-cyclin D2 (CCND2; 1:2,000; cat. no. 67048-1-Ig)

and anti-retinoblastoma (RB1; 1:2,000; cat. no. 67521-1-Ig) were

purchased from Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology; anti-CDK6 (1:1,000;

cat. no. A0705; Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.); and anti-Yin-yang 1

(YY1; 1:1,000; cat. no. GB111880), antitumor protein p53 (TP53;

1:1,000; cat. no. GB111740), anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no.

GB23303) and anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. GB23301) were

purchased from Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.

Transcriptome sequencing and

analysis

Total RNA was isolated from all samples (4 PRMT7-KD

replicates and 4 Control replicates) using TRIzol™ reagent (cat.

no. 15596026CN, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA integrity was

assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (RNA Nano 6000

Assay Kit; Agilent Technologies), and purity was confirmed using a

NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN). Only

high-quality RNA samples (RNA integrity Number >8.0; OD260/280

ratio ~2.0) were used for library construction. Sequencing

libraries were prepared from 1 µg of total RNA per sample using the

NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for

Illumina® (New England BioLabs, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, poly(A)+ mRNA was enriched using

poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads and fragmented. First-strand

cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamer priming and

M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (New England BioLabs, Inc.), followed

by second-strand synthesis with DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. cDNA

fragments were end-repaired, adenylated, and ligated to NEBNext

adaptors. Libraries were size-selected (~250-300 bp) using AMPure

XP beads (Beckman Coulter Inc.) and amplified by PCR with index

primers. Library quality and concentration were validated using the

Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Indexed libraries were pooled and

clustered on a cBot Cluster Generation System (TruSeq PE Cluster

Kit v3-cBot-HS; Illumina, Inc.). Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp)

was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq platform. Raw sequencing reads

(FASTQ format) were quality-filtered using custom Perl scripts to

remove adapter sequences, poly-N reads, and low-quality reads

(Q<20), yielding clean reads. Quality metrics (Q20, Q30, GC

content) were calculated for clean data. Clean reads were aligned

to the human reference genome (GRCh38/hg38; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000001405.26/)

using HISAT2 (v2.0.5; http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/) with

splice-site information derived from gene model annotations.

Transcript assembly and read quantification per gene were performed

using StringTie (v1.3.3b; http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/). Gene

expression levels were quantified as Fragments Per Kilobase of

transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM). Differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) between PRMT7-KD and Control groups (4 vs. 4

replicates) were identified using DESeq2 (v1.16.1) in R. Genes with

an adjusted P-value (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR) <0.05 were

considered statistically significant DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO)

enrichment analysis (Biological Process, Molecular Function,

Cellular Component), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway enrichment analysis, and Disease Ontology (DO) enrichment

analysis of the identified DEGs were performed using the

clusterProfiler R package. Gene length bias was corrected.

Terms/pathways with a corrected P-value (FDR) <0.05 were

considered significantly enriched. The Search Tool for the

Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins database (https://cn.string-db.org/) was used to predict the

possible cell cycle-related regulatory proteins downstream of

PRMT7.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version

17.0; SPSS, Inc.). All data were presented as the mean ± SEM. The

normality of the data was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate normally distributed data.

Homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene's test, with

P>0.05 considered to indicate homogenous data. For data that met

normal distribution assumptions and equal variances, an unpaired

Student's t-test was used to analyze the differences between two

groups and one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons. All P-values derived from high-throughput

analyses (for example, differential gene expression and pathway

enrichment) were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the

Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method with a

significance threshold of FDR <0.05. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Images were

generated using GraphPad Prism 8 (Dotmatics) and Illustrator CC

2018 software (v22.0; Adobe Systems, Inc.). Principal Component

Analysis (PCA) was performed to reduce dimensionality and identify

patterns. The raw dataset was standardized by mean-centering and

scaling to unit variance. The covariance matrix of the standardized

data was computed and decomposed into its eigenvalues and

eigenvectors. Principal Components (PCs) were selected based on

eigenvalues sorted in descending order, retaining components

explaining >80% cumulative variance. The standardized data was

projected onto the orthogonal axes defined by the selected PCs.

Analysis was implemented using: Python, scikit-learn (v1.2.2) with

PCA(svd_solver=‘auto’); R, stats::prcomp() (R v4.3.0); MATLAB,

pca() (MATLAB R2023a).

Results

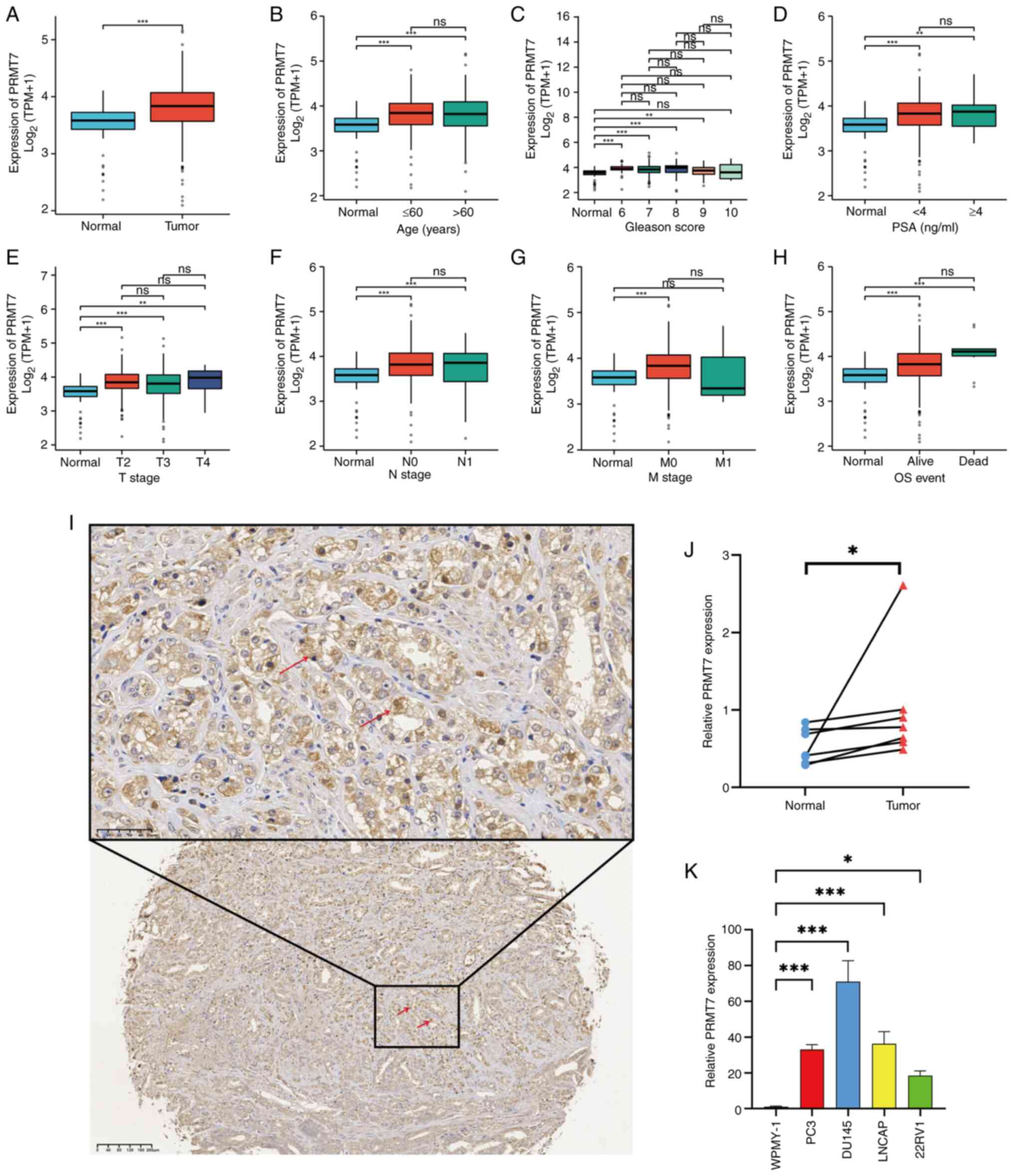

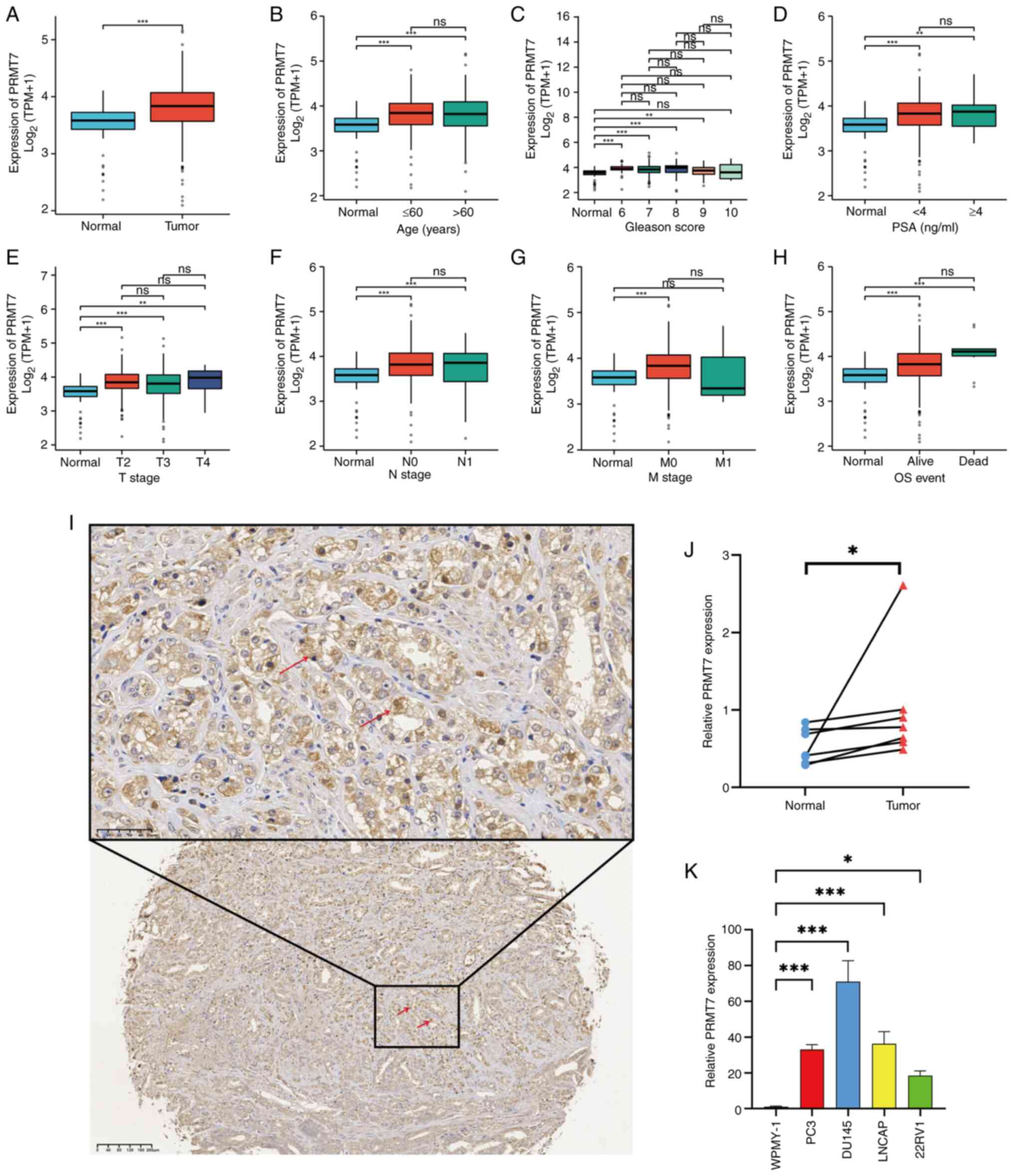

PRMT7 is highly expressed in PCa

To explore whether there is a potential association

between PRMT7 and PCa, relevant data were searched and analyzed in

TCGA database. Significant differences in PRMT7 expression were

identified in cancerous and adjacent tissues and in terms of the

age of patients with PCa, Gleason score, PSA levels and TNM stage

(Fig. 1A-H), which indicated that

PRMT7 may be a key gene in PCa development. To further validate the

aforementioned findings, tissues were collected from 159 patients

with PCa and the correlation between PRMT7 expression and

clinicopathological parameters were analyzed (including age,

Gleason score, PSA level and TNM stage) using tissue microarray

technology. PRMT7 was highly expressed in patients with PCa

(Figs. 1I, SIA). Significant PRMT7 expression

differences were also identified among different PSA levels in

patients with PCa, although there were no significant differences

in PRMT7 expression associated with age, Gleason score or TNM stage

(Table I). This suggested that high

PRMT7 expression is associated with worse prognosis in PCa.

| Figure 1.Differential gene expression patterns

of PRMT7 in PCa. (A) The correlation between PRMT7 expression in

cancerous and adjacent tissues of patients with PCa in TCGA

database. (B) The correlation between PRMT7 expression and age of

patients with PCa in TCGA database. (C) The correlation between

PRMT7 expression and Gleason score of patients with PCa in TCGA

database. (D) The correlation between PRMT7 expression and PSA

levels of patients with PCa in TCGA database. The correlation

between PRMT7 expression and (E) T, (F) N and (G) M stage of

patients with PCa in TCGA database. (H) The correlation between

PRMT7 expression and OS event of patients with PCa in TCGA

database. (I) Representative image of PRMT7 immunohistochemical

staining of PCa tissues and adjacent normal tissues (magnification,

50 and 100×; scale bar, 40 and 10 µm). The red arrows indicate the

PRMT7 positive areas. (J) The expression levels of PRMT7 in PCa

tissues was detected using RT-qPCR. The blue circle represents the

normal tissue around the cancer, while the red arrow represents the

tumor tissue. (K) The expression level of PRMT7 in PCa cell lines

and normal prostate cells was detected using RT-qPCR. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. PRMT7, protein arginine

methyltransferase 7; PCa, prostate cancer; PSA, protein specific

antigen; TPM, transcript per million; TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; ns, not

significant. |

| Table I.Correlation between PRMT7 expression

and clinicopathological factors. |

Table I.

Correlation between PRMT7 expression

and clinicopathological factors.

|

|

| PRMT7

expression |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Covariates | Total, n (%) | Low, n (%) | High, n (%) | P-value | Statistical

test |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<70 | 91 (57.23) | 40 (56.34) | 51 (57.95) | 0.838 | χ2 |

|

≥70 | 68 (42.77) | 31 (43.67) | 37 (42.05) |

|

|

| PSA value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<10 | 64 (40.25) | 22 (34.40) | 42 (65.60) | 0.032a | χ2 |

|

≥10 | 95 (59.75) | 49 (51.60) | 46 (48.40) |

|

|

| Gleason score |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤7 | 114 (71.70) | 52 (73.24) | 62 (70.45) | 0.698 | χ2 |

|

>7 | 45 (28.30) | 19 (26.76) | 26 (29.55) |

|

|

| TNM stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1-T2 | 157 (98.74) | 69 (97.18) | 88 (100) | 0.198 | Fisher's exact

test |

|

T3-T4 | 2 (1.26) | 2 (2.82) | 0 (0.00) |

|

|

To verify the differential upregulation of PRMT7

expression in PCa tissues, PRMT7 mRNA expression levels were

measured in seven pairs of PCa clinical specimens. PRMT7

mRNA expression levels were elevated in PCa tissues (Fig. 1J). Furthermore, compared with those

in WPMY-1 cells (a normal prostate cell line), PRMT7 mRNA

levels were significantly increased in the PCa cell lines (PC3,

DU145, LNCAP and 22RV1; Fig. 1K).

Taken together, the present study results suggested that

PRMT7 is highly expressed in PCa.

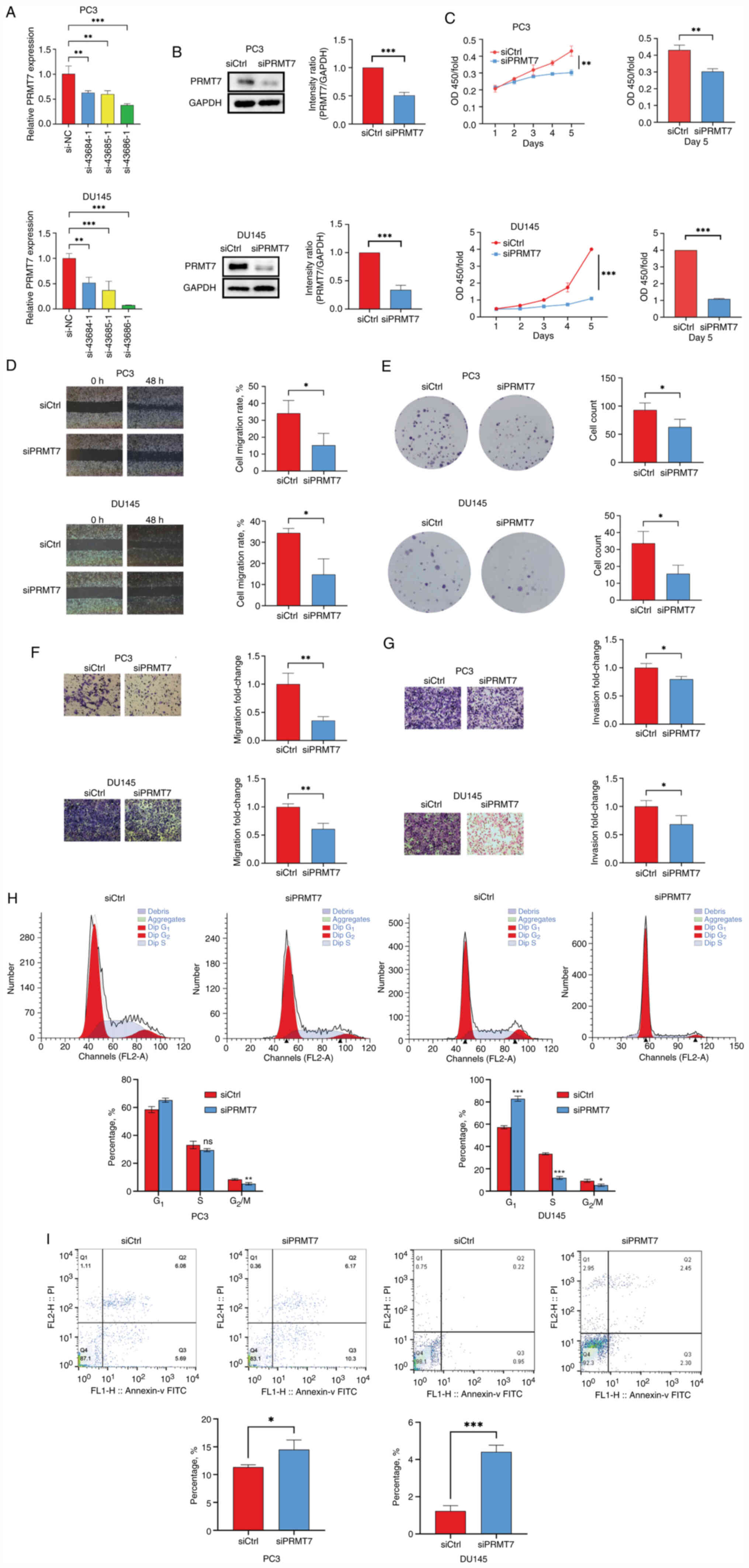

PRMT7 promotes PCa cell proliferation,

migration and invasion, and affects the cell cycle and

apoptosis

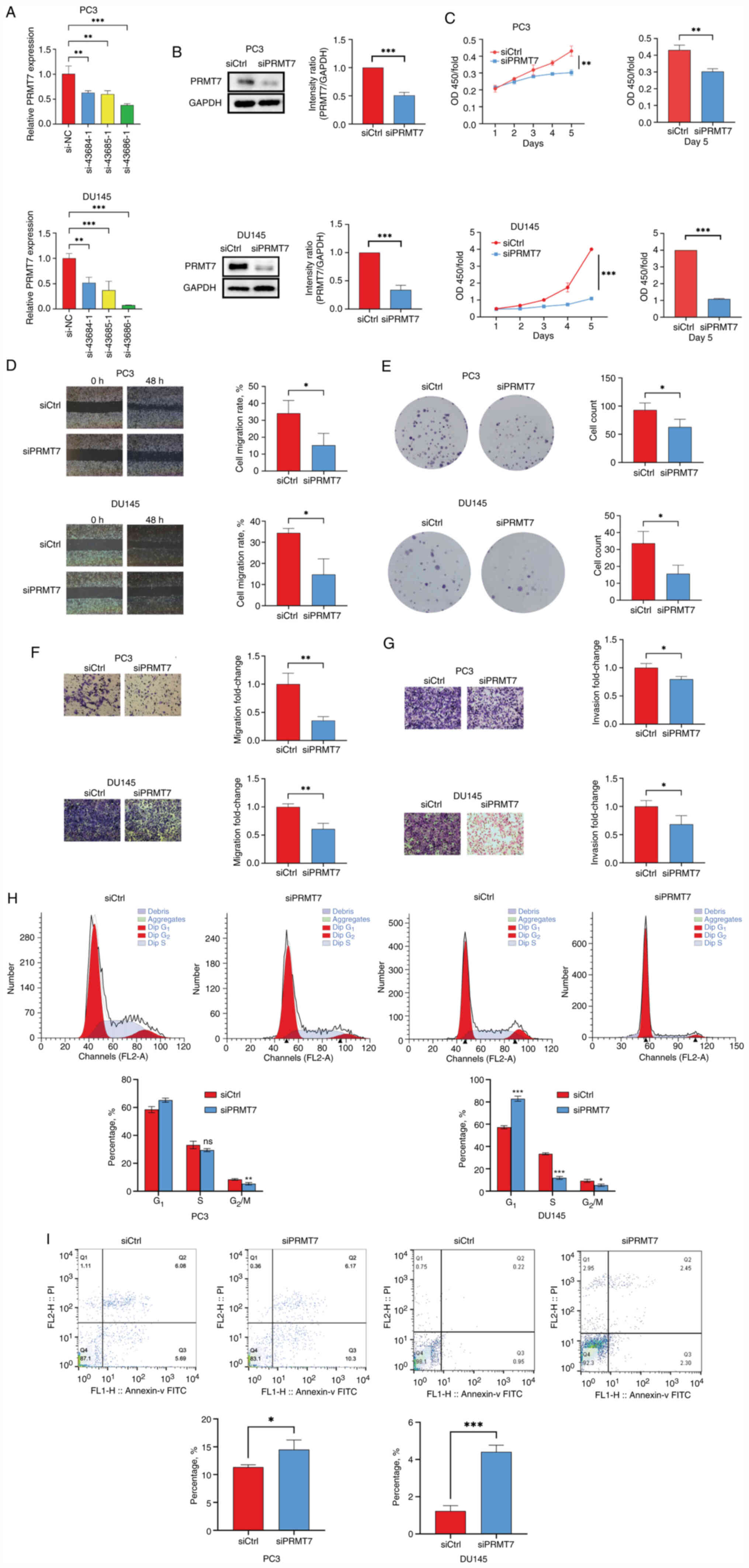

To explore the biological mechanism underlying the

effect of PRMT7 expression on PCa cells, siRNA-mediated PRMT7

silencing was performed to observe the biological changes in cancer

cells. A total of three siRNA-coding clones were designed based on

the PRMT7 sequence; they could be used for both stable and

transient expression in vertebrate cells to decrease the expression

levels of PRMT7. Subsequently, RT-qPCR was performed to verify the

silencing efficiency of the three siRNAs in PC3 and DU145 cells.

Analysis suggested that after 3 days of siRNA (43684-1, 43685-1 and

43686-1) transfection, the mRNA and protein expression levels of

PRMT7 in the experimental group (si-43686-1) was reduced (Fig. 2A). SiRNA 43686-1 demonstrated high

silencing efficiency in PC3 and DU145 cells; therefore, siRNA

43686-1 was selected for subsequent experiments. Knockdown

efficiency was also evaluated using western blotting (Fig. 2B).

| Figure 2.Function of PRMT7 in the PC3 and

DU145 cell lines. (A) The inhibition efficiency of siPRMT7 in cell

lines was determined using RT-qPCR. (B) Western blotting was used

to detect the protein expression levels of PRMT7 in the siPRMT7 and

siCtrl groups. (C) Cell proliferation in the siCtrl and siPRMT7

groups was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (D) A wound

healing assay was used to investigate the migratory ability of PCa

cells after PRMT7 knockdown (scale bar, 500 µm). (E) Plate colony

formation assays were performed to determine the proliferation

abilities of PC3 and DU145 cells treated with siCtrl and siPRMT7.

The (F) migration and (G) invasion of PC3 and DU145 cells were

investigated using a Transwell assay after PRMT7 knockdown (scale

bar, 100 µm). (H) PI-FACS detection of the effect of PRMT7

knockdown on the PCa cell cycle. (I) The effect of PRMT7 knockdown

on the apoptosis of PCa cells was detected using Annexin V-APC

single staining. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. PRMT7,

protein arginine methyltransferase 7; PCa, prostate cancer;

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; siRNA, small

interfering RNA; si, siRNA; Ctrl; control; NC, negative control;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8. |

CCK-8 assays indicated that the proliferation rates

of PC3 and DU145 cells were significantly reduced after PRMT7

knockdown, which suggested that PRMT7 significantly affected cell

proliferation (Fig. 2C). The

results of wound healing and migration assays suggested that PRMT7

expression is significantly associated with the migratory ability

of PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 2D).

PRMT7 knockdown also significantly reduced the number of PC3 and

DU145 cell clones (Fig. 2E).

However, no effects associated with proliferation and colony

formation were observed in the PRMT7-knockdown WPMY-1 cell line

(Fig. S1B and C). The results of

the invasion assay suggested that the invasion and metastatic

capacities of PC3 and DU145 cells in the experimental group were

significantly inhibited 3 days after siRNA infection, which

suggested a significant association between these cell properties

and PRMT7 expression (Fig. 2F and

G). After PRMT7 knockdown, the number of PC2 cells in the

G1 phase increased (P<0.05), while that in the

G2/M phase decreased (P<0.01). Similarly, the

proportion of DU145 cells in the G1 phase increased

(P<0.001), whereas that in the S-phase and G2/M

phases decreased (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively). These

results suggested that PRMT7 expression is significantly associated

with the cell cycle (Fig. 2H).

Furthermore, the rate of apoptosis in PC3 and DU145 cells was

significantly increased after transfection with siPRMT7 compared

with that in the siCtrl group, which suggested a significant

correlation between PCa with PRMT7 (Fig. 2I). These results confirmed that

PRMT7 knockdown could inhibit PC3 and DU145 cell proliferation,

migration and invasion, as well as the cell cycle and

apoptosis.

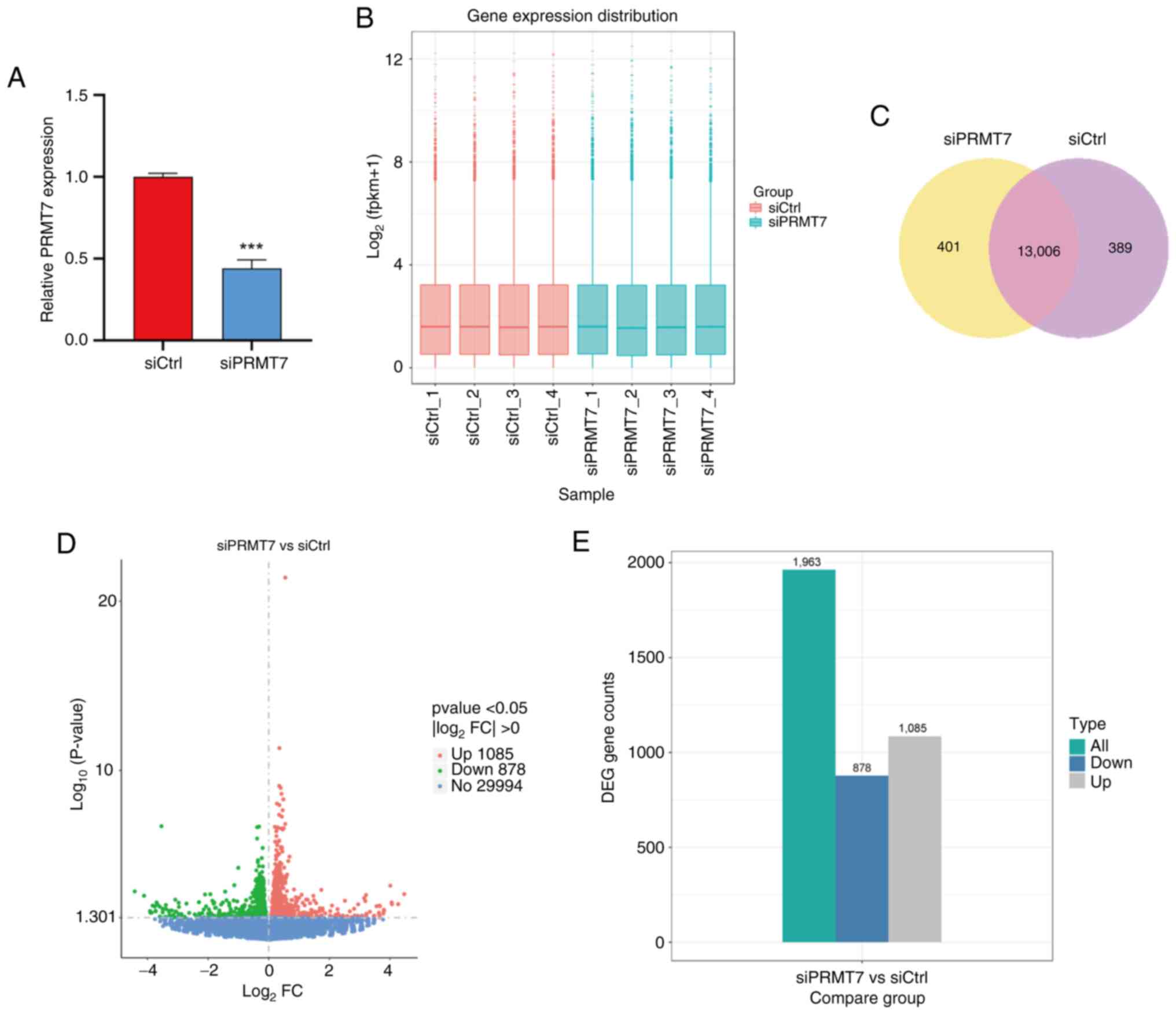

PRMT7 influences the cell cycle in PCa

cells

Next, the PRMT7 knockdown plasmid siPRMT7 was

transfected into the PCa cell line PC3 (Fig. 3A). A total of four groups of siCtrl

and siPRMT7 cells were selected for transcriptome sequencing

(Fig. 3B), in which 13,006 genes

were revealed to be co-expressed between the two groups of samples

(Fig. 3C). Differential gene

screening among samples revealed that the expression levels of

1,085 genes were upregulated and expression levels of 878 genes

were downregulated in siPRMT7 cells compared with that in siCtrl

cells (Fig. 3D and E). A

differential gene set was formed by combining the differential

genes after classification. Mainstream hierarchical clustering was

used to perform cluster analysis on the FPKM values of the genes

and conducted homogenization of rows (Z-score; Figs. S2 and S3).

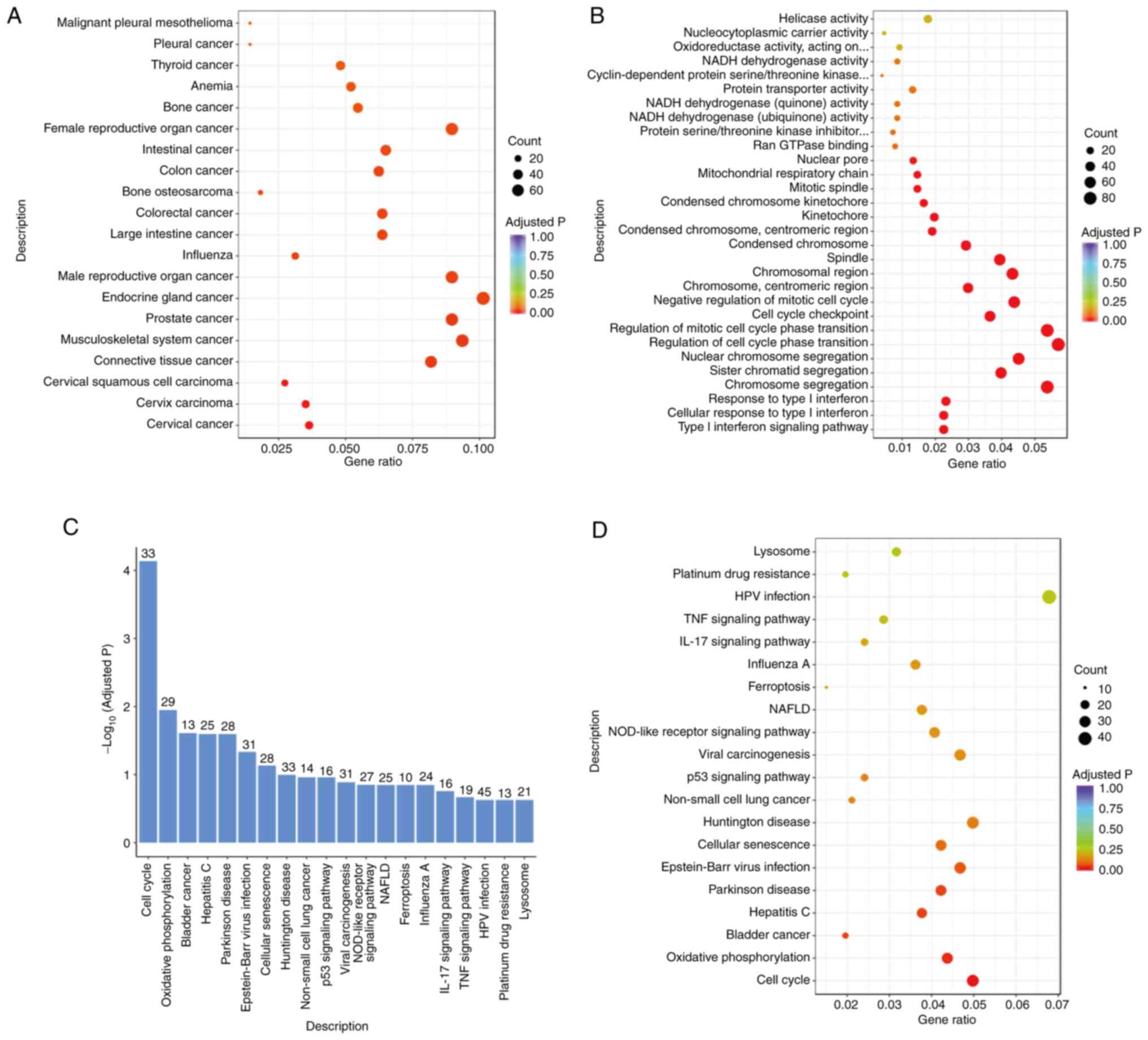

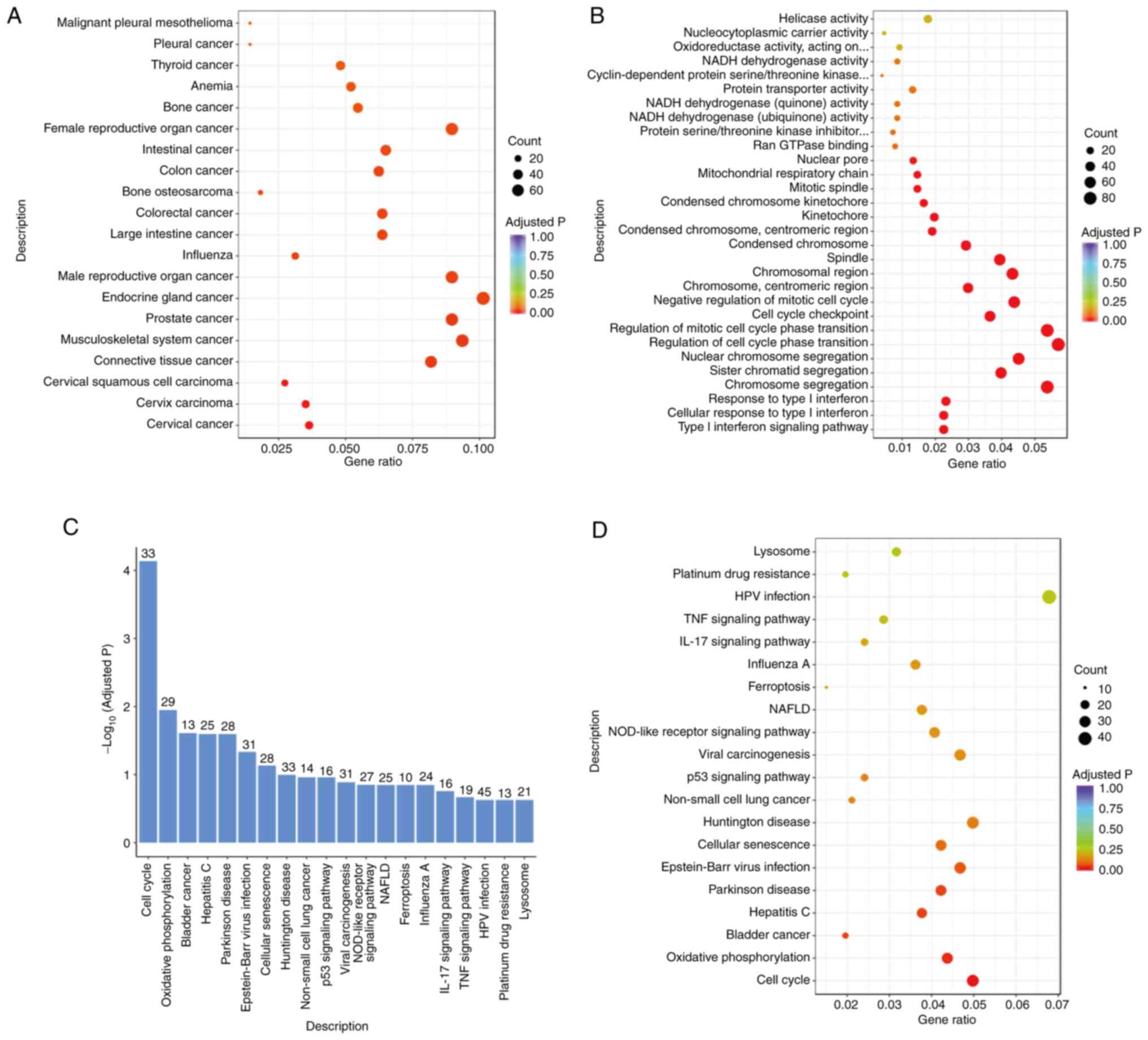

To explore the functional characteristics of the

differentially expressed genes and predict the downstream pathways

of PRMT7, the differentially expressed genes were classified

according to their functions and gene function enrichment analyses

were carried out, including GO, KEGG, DO and other pathway

analyses. DO analysis revealed that the differential genes were

enriched in ‘prostate cancer’ pathways, which confirmed the data

presented in Fig. 4A. Furthermore,

GO functional enrichment analysis demonstrated that the

differentially expressed genes were enriched in the ‘cell cycle’

and ‘cycle checkpoint’ functions (Fig.

4B), which was confirmed by the KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis results. KEGG is a comprehensive database that integrates

genomic, chemical and system function information. A total of 33

DEGs in PC3 cells after PRMT7 knockdown regulate the ‘cell cycle’

function (Fig. 4C and D). Thus,

PRMT7 is involved in cell cycle-related pathways in PCa cells,

which could contribute to the malignant phenotype of PCa.

| Figure 4.PRMT7 is involved in the regulation

of cell cycle-related pathways and affects the cell cycle in PCa.

(A) The DO enrichment distribution map of the DEGs associated with

PRMT7. DO is a biomedical database that systematically annotates

associations between human gene functions and diseases, providing

standardized disease descriptors for functional genomics research.

(B) Map of the GO enrichment sites of the DEGs associated with

PRMT7. GO is a comprehensive bioinformatics resource that

systematically characterizes gene functions through three

orthogonal categories: Biological processes, cellular components

and molecular functions. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs

associated with PRMT7. KEGG is an integrated database that

systematically consolidates genomic, chemical and systems

functional information to facilitate biological pathway analysis

and network modeling. (D) KEGG enrichment and distribution map of

the PRMT7 differential genes. PRMT7, protein arginine

methyltransferase 7; DEGs, Differentially expressed genes;

log2FC, log2 fold change; DO, Disease

Ontology; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes; NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NOD,

Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain. |

PRMT7 promotes the malignant

progression of PCa through the YY1/TP53/CCND2/CDK6/RB1 signaling

axis

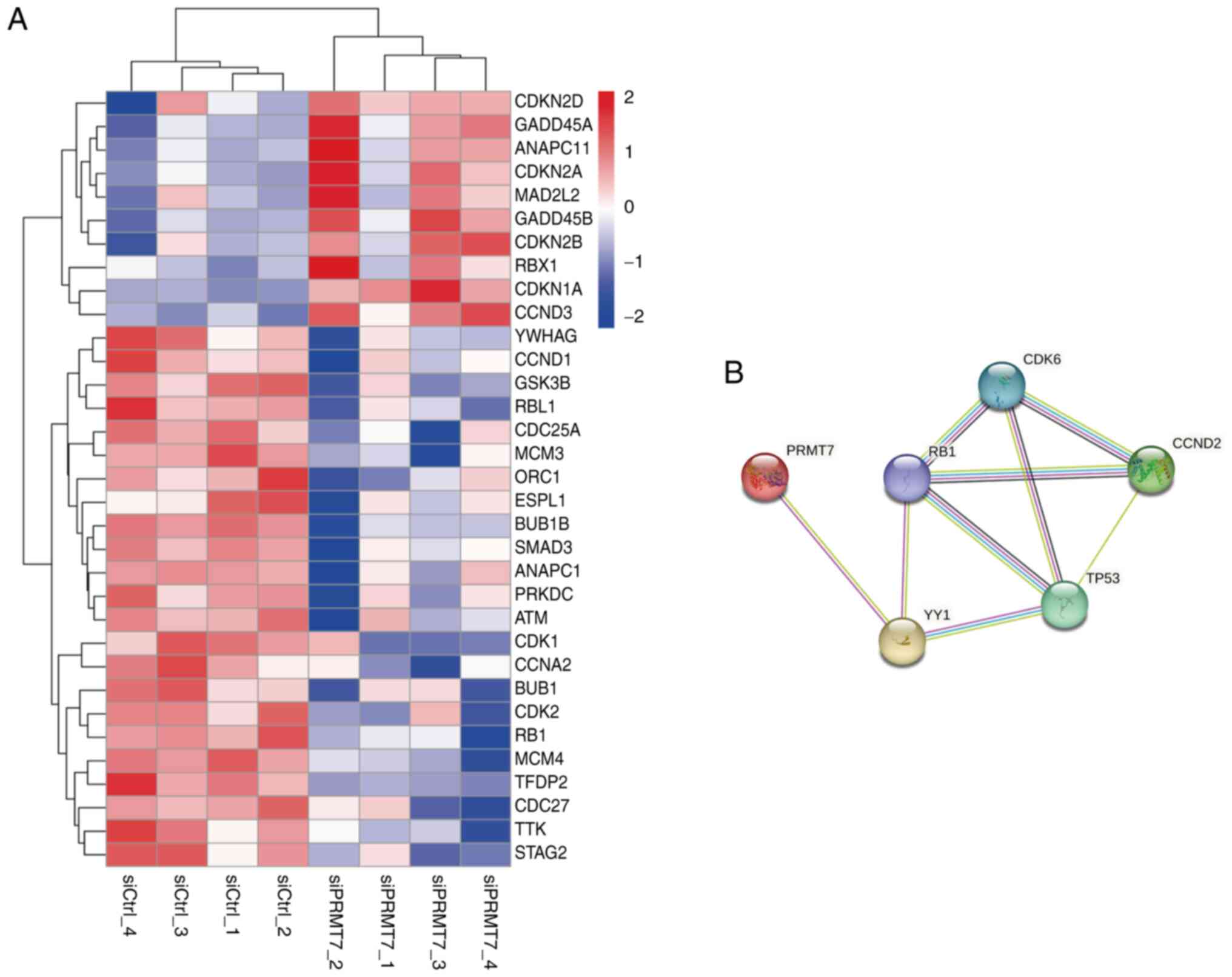

To further explore the downstream mechanisms of

PRMT7 in PCa, transcriptome sequencing data were used to map the

differentially expressed genes associated with the cell cycle

(Fig. 5A). We also predicted the

potential cell cycle-related regulatory proteins downstream of

PRMT7 (Fig. 5B). TP53 is an

important cell cycle-related protein; mutations of TP53 have been

reported to be important carcinogenic factors in PCa (12). To verify the validity of the

predicted PRMT7 cell cycle-related pathways, proteins were

collected and extracted from PC3 cells in the siPRMT7 and siCtrl

groups and the expression levels of proteins involved in the

aforementioned pathways between the two groups were compared using

western blotting. The western blot data indicated that PRMT7

knockdown may modulate the activity of the aforementioned signaling

pathways, as evidenced by altered expression levels of key pathway

markers (Fig. S4). Collectively,

the findings of the present study demonstrated that PRMT7 modulates

the activity of key cell cycle regulators, including ‘YY1’, ‘TP53’,

‘CCND2’, ‘CDK6’ and ‘RB1’ in prostate carcinogenesis, which

suggests its key role in driving cell cycle dysregulation.

Discussion

The occurrence and progression of cancer involves

several cancer-promoting and cancer-suppressing genes. With the

development of epigenetics, numerous tumor-related epigenetic

changes have become the focus of research on cancer-related

mechanisms. PTMs involved in PCa are also a current research focus

(37,38). Yao et al (30) suggested that PRMT5 inhibits the

transcription of CAMK2N1 and promotes PCa progression, which

is regulated by the circSPON2/miR-331-3p axis. PRMT5 is recruited

to AR promoters by the transcription factor Sp1 in LNCAP cell lines

to promote tumor cell proliferation (39). PRMT7, a member of the same family as

PRMT5 and the only representative of the type III group, can

monomethylate arginine. To the best of our knowledge, studies on

the mechanism of action of PRMT7 in cancer are currently limited.

Only a part of its mechanism of action in breast cancer has been

identified and these previous findings suggested that it may be an

important target for breast cancer treatment (27,40,41).

However, due to its regulatory role in cancer stem cells (42,43),

PRMT7 may also serve a key epigenetic regulatory role in several

cancer types, including PCa. Rodrigo-Faus et al (44) proposed that in metastatic

castration-resistant PCa cells, PRMT7 methylates various

transcription factors (such as forkhead box protein K1) to

reprogram the expression of several adhesion molecules, which lead

to the loss of adhesiveness in the primary tumor and increases its

migratory ability. However, the experiments of the present study

suggested a different conclusion. The present study suggested that

PRMT7 was carcinogenic in PCa and may serve a role in cell cycle

regulation of cancer cells. This was consistent with the results of

other PRMT7 studies in renal cell carcinoma (24) and human non-small-cell lung cancer

cells (45), which suggested that

PRMT7 is likely a strong tumor-associated epigenetic factor.

Based on a previous study by Vieira et al

(32), the present study explored

the specific molecular mechanism of PRMT7 in PCa to gain a more

comprehensive understanding of the activity of PRMT7 and provide

novel strategies for the clinical treatment and diagnosis of PCa.

Tissues from 159 patients with PCa were collected and the

correlation between PRMT7 expression and age, Gleason score, PSA

and TNM stage were analyzed using tissue chip technology. PRMT7

expression significantly associated with PSA levels in patients

with PCa. After analyzing the histochemical results of the patient

samples, the present study demonstrated that PRMT7 was abnormally

expressed in cancer tissues, which suggests that it may be

associated with the occurrence and progression of PCa. RT-qPCR

results of paired PCa clinical specimens suggested that PRMT7

expression was also increased in PCa tissues. Similarly, PRMT7

expression was significantly increased in PCa cells compared with

that in prostate epithelial cells.

Subsequently, siRNAs were used to knock down PRMT7

expression in PC3 and DU145 cells. PRMT7 promoted PCa cell

proliferation, migration and invasion and affected the cell cycle

and apoptosis. These results demonstrated that PRMT7 is an oncogene

that contributes to the malignant phenotype of PCa.

Furthermore, the present study explored the specific

regulatory mechanisms by which PRMT7 exerts oncogenic effects in

PCa. Bioinformatics analysis and transcriptome sequencing were used

to search for PRMT7-related differentially expressed genes in PCa

and predict the potential downstream cancer-promoting signaling

molecules. The present study determined that PRMT7 may be involved

in cell cycle control pathways, particularly the

YY1/TP53/CCND2/CDK6/RB1 signaling pathway.

p53 is a stress-activated transcription factor that

regulates the expression of target genes involved in DNA repair,

cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis to maintain genomic stability and

suppress tumorigenesis (46).

Mutations in the p53 gene have been reported in 50% of all human

malignancies, including breast, colon, lung, liver, prostate,

bladder and skin cancer (47). p53

orchestrates cell cycle checkpoints (G1/S, G2/M arrest),

senescence, and metabolic adaptation to preserve genomic integrity.

As a tumor suppressor, it is indispensable for eliminating damaged

normal cells, while its dysfunction in cancer promotes genomic

instability, therapy resistance, and metastasis (46,48–52).

However, the results of the present study indicated that PRMT7

depletion did not significantly affect TP53 protein expression

levels. PC3 cells harbor homozygous deletion of TP53, which

explains the lack of detectable changes. This confirms that the

pro-proliferative effects of PRMT7 in PC3 cells are independent of

canonical p53 pathways. However, PRMT7 may still engage alternative

survival pathways (for example, MDM2 and AKT) in p53-null cells to

bypass p53-mediated cell cycle checkpoints.

YY1 is a member of the GLI-Kruppel zinc finger

protein family that has two opposing abilities: Inhibiting and

activating gene transcription (53). PRMT7 interacts with YY1, which leads

to breast cancer cell migration and invasion (26). In the present study, YY1 exhibited a

small yet statistically significant decrease in expression upon

PRMT7 knockdown. PRMT7 may methylate YY1 to stabilize its protein

or enhance its transcriptional activity. Loss of PRMT7-dependent

methylation could impair the ability of YY1 to activate downstream

targets, including cell cycle regulators such as CCND2/CDK6

(54–56). In indirect regulation, YY1

downregulation might reflect secondary effects of PRMT7 knockdown,

such as altered chromatin accessibility at YY1-binding loci or

dysregulation of upstream signaling pathways (56,57).

This mild reduction suggests YY1 is not the primary effector of

PRMT7 in PC3 cells, but its partial loss may synergize with other

pathways to amplify CCND2/CDK6 suppression.

CCND2 is a member of the cyclin family that encodes

cyclin D2. It regulates cancer cell processes through the cell

cycle. Cyclin D2 reduces the inhibitory effect of miR-615 on the

proliferation, migration and invasion of PCa cells (58). The expression levels of E2F

transcription factor 2 and CCND2 was downregulated by let-7a; the

latter may inhibit PCa growth in an in vivo PCa xenograft

model (59). CCND2 promotes PCa

development and CDK6 and RB1 are well-known cell cycle regulators;

several studies have reported that targeting them can affect the

cell cycle of PCa cells and inhibit their proliferation (60–63).

Analysis of the western blotting experiments in the present study

demonstrated that CCND2 and CDK6 levels were markedly downregulated

following PRMT7 depletion. PRMT7-mediated symmetric dimethylation

of histone H4R3 (H4R3me2s) is key for maintaining an active

chromatin state at the CCND2 promoter. PRMT7 knockdown may induce

heterochromatin formation, which represses transcription. PRMT7

might methylate RNA-binding proteins to stabilize CCND2 mRNA; its

absence could accelerate mRNA degradation. PRMT7 may methylate

histones (for example, H3R2me2s) at the CDK6 promoter to facilitate

transcriptional elongation by RNA Polymerase II. Furthermore, YY1

has been reported to bind the CDK6 promoter (64). The concurrent downregulation of YY1

and CDK6 expression suggests a PRMT7-YY1-CDK6 regulatory axis. In

the present study, total RB1 protein levels demonstrated no

significant alteration after PRMT7 knockdown. RB1 function is

primarily governed by phosphorylation status compared with total

protein abundance. The observed CCND2/CDK6 downregulation likely

reduces RB1 phosphorylation, activating its growth-suppressive

function without altering total RB1 levels. PRMT7 may methylate RB1

to modulate its interaction with E2F or chromatin remodelers.

However, such modifications might not affect total RB1 stability,

which necessitates phospho-specific assays. Therefore, these

results suggested that PRMT7 likely serves a role in TP53-related

cell cycle pathways, ultimately contributing to PCa

progression.

Previous studies on blocking AR resistance have

indicated the role of AR-related cell cycle pathways in PCa

(65–67). The binding of androgens to their

receptors induces cell cycle progression by directly affecting the

transcription-regulated expression of cell cycle regulatory

proteins (68). This involves

ligand-activated AR signaling regulation of the cell cycle, which

causes androgen-deprived ADT-sensitive cells to exit the cell cycle

and stall in the G0 phase (69–71).

As CDK complexes control transition within the cell cycle and

maintain progression from the G1 phase to mitosis

(72–74), AR can promote tumor cell

proliferation by affecting the activity of CDKs and CDK inhibitors.

After androgen blocking, the expression of major D-type cyclin is

inhibited in ADT-reactive PCa cells, which results in cell cycle

arrest and the inhibition of cell proliferation (71,75).

The growth factor-mediated accumulation of D-type cyclins in cells

further induces CDK4/6 activity and maintains the cell cycle

(74), which initiates the

phosphorylation/inactivation of the RB tumor suppressor and

blocking the RB-mediated negative regulation of cell cycle

transition and DNA replication (76). These results suggested that further

research on cell cycle changes in PCa could help to elucidate the

possible mechanism of androgen-blocking drug resistance and

tumorigenesis.

The present study had several limitations. For

instance, the sample collection period was relatively short (~6

months). Although an adequate sample size was achieved from this

high-volume tertiary hospital (Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan

University; Wuxi, China), the potential for temporal bias requires

consideration. Furthermore, the present study primarily relied on

in vitro experiments. Future research should validate these

findings through multicenter cohorts and further investigate the

molecular mechanisms underlying PRMT7-mediated cell cycle

regulation. Ideally, a larger and directly matched control group

would enhance the reliability of the findings. Furthermore, future

collaborations with other institutions aim to obtain a more

comprehensive dataset, thereby improving the external validity of

the present study results. Although the present study revealed that

PRMT7 modulates cell cycle progression in PCa cells through a

specific signaling axis, the mechanisms underlying cell cycle

G0 arrest and the downstream phosphorylation of

associated factors remains to be elucidated. Relying on

bioinformatics prediction methods, specific research directions

were identified to study the mechanism by which PRMT7 promotes PCa.

These findings suggested a functional involvement of PRMT7 in

modulating PCa cell cycle progression, but more rigorous

mechanistic investigations are required to fully delineate its

underlying molecular actions. However, due to the lack of further

evidence, the present study was unable to confirm the precise

mechanism by which PRMT7 affected cell cycle-related factors such

as YY1, TP53, CCND2, CDK6 and RB1 in PCa. As members of the same

enzyme family, PRMT7 and other PRMTs may exhibit synergistic or

antagonistic interactions in vivo. Notably, studies have

reported that PRMT7-mediated monomethylation of histone H4 at

Arg-17 can directly modulate PRMT5-catalyzed symmetric

dimethylation at Arg-3 within the same histone protein (77,78).

Therefore, investigating the functional role of PRMT7 in PCa

progression must account for the coordinated or competitive

activities of other PRMT family members, particularly in regulating

cell cycle checkpoints through key effectors such as RB1

phosphorylation and CDK6 activation. These mechanisms require

further investigation in future studies. Future experiments will

include exploring the specific mechanism of PRMT7 in the PCa cell

cycle and identifying effective molecularly targeted drugs

associated with PRMT7 to provide research directions for the

precise treatment of PCa.

The present study confirmed that PRMT7 was involved

in the proliferation and invasion of PCa cells and potentially

promoted the malignant progression through the

YY1/TP53/CCND2/CDK6/RB1 cell cycle signaling axis.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the following

entities: The National Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

81802576), Wuxi Commission of Health and Family Planning (grant

nos. T202102, Z202011 and M202330) and Talent plan of Taihu Lake in

Wuxi (Double Hundred Medical Youth Professionals Program) from

Health Committee of Wuxi (grant nos. BJ2020061 and BJ2023051).

Furthermore, the Clinical Trial of Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan

University (grant nos. LCYJ202227 and LCYJ202323), Research Topic

of Jiangsu Health Commission (grant no. Z2022047) and Jiangsu

Province 7th phase ‘333’ high-level talents [grant no.

(2024)3-2425] also provided funding support for the present

study.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number (GSE302155)

or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE302155.

The remaining data generated in the present study may be requested

from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HW, HZ, JG, NF and DY conceived and designed the

present study; HW, RW, JN and YM performed the experiments and

acquired the data. SW, YQ, QQ and LZ contributed to data analysis.

HW and YM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University (approval

no. LS2023099; Wuxi, China) and written informed consent was

obtained from all patients prior to sample collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sugiura M, Sato H, Kanesaka M, Imamura Y,

Sakamoto S, Ichikawa T and Kaneda A: Epigenetic modifications in

prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 28:140–149. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu J, Dong L, Zhu Y, Dong B, Sha J, Zhu

HH, Pan J and Xue W: Prostate cancer treatment-China's perspective.

Cancer Lett. 550:2159272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu X, Yu C, Bi Y and Zhang ZJ: Trends and

age-period-cohort effect on incidence and mortality of prostate

cancer from 1990 to 2017 in China. Public Health. 172:70–80. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang F, Wang C, Xia H, Lin Y, Zhang D, Yin

P and Yao S: Burden of prostate cancer in China, 1990–2019:

Findings from the 2019 global burden of disease study. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8536232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K,

Chen R, Li L, Wei W and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:47–53. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N and Chen WQ:

Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A

secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J

(Engl). 134:783–791. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V,

Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ,

Estève J, et al: Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival

2000–14 (CONCORD-3): Analysis of individual records for 37 513 025

patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based

registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 391:1023–1075. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan

DW, Pearson JD and Walsh PC: Natural history of progression after

PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 281:1591–1597.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lobo J, Barros-Silva D, Henrique R and

Jeronimo C: The emerging role of epitranscriptomics in cancer:

Focus on urological tumors. Genes (Basel). 9:5522018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S,

Johnson DC, Reiter RE, Gillessen S, Van der Kwast T and Bristow RG:

Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:92021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Barsouk A, Padala SA, Vakiti A, Mohammed

A, Saginala K, Thandra KC, Rawla P and Barsouk A: Epidemiology,

staging and management of prostate cancer. Med Sci (Basel).

8:282020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Feldman BJ and Feldman D: The development

of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 1:34–45.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hirst M and Marra MA: Epigenetics and

human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 41:136–146. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Miremadi A, Oestergaard MZ, Pharoah PD and

Caldas C: Cancer genetics of epigenetic genes. Hum Mol Genet.

16:R28–R49. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fisk JC, Sayegh J, Zurita-Lopez C, Menon

S, Presnyak V, Clarke SG and Read LK: A type III protein arginine

methyltransferase from the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei. J

Biol Chem. 284:11590–11600. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Feng Y, Hadjikyriacou A and Clarke SG:

Substrate specificity of human protein arginine methyltransferase 7

(PRMT7): The importance of acidic residues in the double E loop. J

Biol Chem. 289:32604–32616. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zurita-Lopez CI, Sandberg T, Kelly R and

Clarke SG: Human protein arginine methyltransferase 7 (PRMT7) is a

type III enzyme forming omega-NG-monomethylated arginine residues.

J Biol Chem. 287:7859–7870. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Debler EW, Jain K, Warmack RA, Feng Y,

Clarke SG, Blobel G and Stavropoulos P: A glutamate/aspartate

switch controls product specificity in a protein arginine

methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:2068–2073. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bedford MT and Richard S: Arginine

methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Mol Cell.

18:263–272. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bedford MT and Clarke SG: Protein arginine

methylation in mammals: Who, what, and why. Mol Cell. 33:1–13.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang Y and Bedford MT: Protein arginine

methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:37–50. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu F, Wan L, Zou H, Pan Z, Zhou W and Lu

X: PRMT7 promotes the growth of renal cell carcinoma through

modulating the beta-catenin/C-MYC axis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

120:1056862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Baldwin RM, Haghandish N, Daneshmand M,

Amin S, Paris G, Falls TJ, Bell JC, Islam S and Côté J: Protein

arginine methyltransferase 7 promotes breast cancer cell invasion

through the induction of MMP9 expression. Oncotarget. 6:3013–3032.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yao R, Jiang H, Ma Y, Wang L, Wang L, Du

J, Hou P, Gao Y, Zhao L, Wang G, et al: PRMT7 induces

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and promotes metastasis in

breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74:5656–5667. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ma W, Sun X, Zhang S, Chen Z and Yu J:

Circ_0039960 regulates growth and Warburg effect of breast cancer

cells via modulating miR-1178/PRMT7 axis. Mol Cell Probes.

64:1018292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fuhrmann J and Thompson PR: Protein

arginine methylation and citrullination in epigenetic regulation.

ACS Chem Biol. 11:654–668. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fuhrmann J, Clancy KW and Thompson PR:

Chemical biology of protein arginine modifications in epigenetic

regulation. Chem Rev. 115:5413–5461. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yao B, Zhu S, Wei X, Chen MK, Feng Y, Li

Z, Xu X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhou J, et al: The circSPON2/miR-331-3p

axis regulates PRMT5, an epigenetic regulator of CAMK2N1

transcription and prostate cancer progression. Mol Cancer.

21:1192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Beketova E, Fang S, Owens JL, Liu S, Chen

X, Zhang Q, Asberry AM, Deng X, Malola J, Huang J, et al: Protein

arginine methyltransferase 5 promotes pICln-dependent androgen

receptor transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Cancer Res. 80:4904–4917. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vieira FQ, Costa-Pinheiro P,

Ramalho-Carvalho J, Pereira A, Menezes FD, Antunes L, Carneiro I,

Oliveira J, Henrique R and Jerónimo C: Deregulated expression of

selected histone methylases and demethylases in prostate carcinoma.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 21:51–61. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B,

Srigley JR and Humphrey PA: The 2014 international society of

urological pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on gleason grading

of prostatic carcinoma: Definition of grading patterns and proposal

for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 40:244–252. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xiao WJ, Zhu Y, Zhu Y, Dai B and Ye DW:

Evaluation of clinical staging of the American Joint Committee on

Cancer (eighth edition) for prostate cancer. World J Urol.

36:769–774. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Feng Y, Sun C, Zhang L, Wan H, Zhou H,

Chen Y, Zhu L, Xia G and Mi Y: Upregulation of COPB2 promotes

prostate cancer proliferation and invasion through the MAPK/TGF-β

signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 12:8653172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mi YY, Ji Y, Zhang L, Sun CY, Wei BB, Yang

DJ, Wan HY, Qi XW, Wu S and Zhu LJ: A first-in-class HBO1 inhibitor

WM-3835 inhibits castration-resistant prostate cancer cell growth

in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 14:672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jaiswal B, Agarwal A and Gupta A: Lysine

acetyltransferases and their role in AR signaling and prostate

cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8865942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cocchiola R, Romaniello D, Grillo C,

Altieri F, Liberti M, Magliocca FM, Chichiarelli S, Marrocco I,

Borgoni G, Perugia G and Eufemi M: Analysis of STAT3

post-translational modifications (PTMs) in human prostate cancer

with different Gleason Score. Oncotarget. 8:42560–42570. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Deng X, Shao G, Zhang HT, Li C, Zhang D,

Cheng L, Elzey BD, Pili R, Ratliff TL, Huang J and Hu CD: Protein

arginine methyltransferase 5 functions as an epigenetic activator

of the androgen receptor to promote prostate cancer cell growth.

Oncogene. 36:1223–1231. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu L, Zhang X, Ding H, Liu X, Cao D, Liu

Y, Liu J, Lin C, Zhang N, Wang G, et al: Arginine and lysine

methylation of MRPS23 promotes breast cancer metastasis through

regulating OXPHOS. Oncogene. 40:3548–3563. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Li L, Liu X, Wang Y, Liu L, Peng L,

Liu J, Zhang L, Wang G, Li H, et al: Arginine methylation of SHANK2

by PRMT7 promotes human breast cancer metastasis through activating

endosomal FAK signalling. Elife. 9:e576172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Nicot C: PRMT7: A survive-or-die switch in

cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 21:1272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu C, Zou W, Nie D, Li S, Duan C, Zhou M,

Lai P, Yang S, Ji S, Li Y, et al: Loss of PRMT7 reprograms glycine

metabolism to selectively eradicate leukemia stem cells in CML.

Cell Metab. 34:818–35.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Rodrigo-Faus M, Vincelle-Nieto A, Vidal N,

Puente J, Saiz-Pardo M, Lopez-Garcia A, Mendiburu-Eliçabe M, Palao

N, Baquero C, Linzoain-Agos P, et al: CRISPR/Cas9 screenings

unearth protein arginine methyltransferase 7 as a novel essential

gene in prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 588:2167762024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cheng D, He Z, Zheng L, Xie D, Dong S and

Zhang P: PRMT7 contributes to the metastasis phenotype in human

non-small-cell lung cancer cells possibly through the interaction

with HSPA5 and EEF2. Onco Targets Ther. 11:4869–4876. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen J: The Cell-cycle arrest and

apoptotic functions of p53 in tumor initiation and progression.

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a0261042016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Marei HE, Althani A, Afifi N, Hasan A,

Caceci T, Pozzoli G, Morrione A, Giordano A and Cenciarelli C: p53

signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int.

21:7032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hashimoto N, Nagano H and Tanaka T: The

role of tumor suppressor p53 in metabolism and energy regulation,

and its implication in cancer and lifestyle-related diseases.

Endocr J. 66:485–496. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liu J, Zhang C, Hu W and Feng Z: Tumor

suppressor p53 and metabolism. J Mol Cell Biol. 11:284–292. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang H, Xu J, Long Y, Maimaitijiang A, Su

Z, Li W and Li J: Unraveling the guardian: P53′s multifaceted role

in the DNA Damage response and tumor treatment strategies. Int J

Mol Sci. 25:129282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mirzayans R, Andrais B, Kumar P and Murray

D: Significance of Wild-type p53 signaling in suppressing apoptosis

in response to chemical genotoxic agents: Impact on chemotherapy

outcome. Int J Mol Sci. 18:9282017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Madan E, Gogna R, Bhatt M, Pati U,

Kuppusamy P and Mahdi AA: Regulation of glucose metabolism by p53:

Emerging new roles for the tumor suppressor. Oncotarget. 2:948–957.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang W, Li D and Sui G: YY1 is an inducer

of cancer metastasis. Crit Rev Oncog. 22:1–11. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li Z, Wang F, Tian X, Long J, Ling B,

Zhang W, Xu J and Liang A: HCK maintains the self-renewal of

leukaemia stem cells via CDK6 in AML. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

40:2102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Buontempo F, McCubrey JA, Orsini E,

Ruzzene M, Cappellini A, Lonetti A, Evangelisti C, Chiarini F,

Evangelisti C, Barata JT and Martelli AM: Therapeutic targeting of

CK2 in acute and chronic leukemias. Leukemia. 32:1–10. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Rizkallah R, Alexander KE, Kassardjian A,

Lüscher B and Hurt MM: The transcription factor YY1 is a substrate

for Polo-like kinase 1 at the G2/M transition of the cell cycle.

PLoS One. 6:e159282011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Dong X, Guo R, Ji T, Zhang J, Xu J, Li Y,

Sheng Y, Wang Y, Fang K, Wen Y, et al: YY1 safeguard

multidimensional epigenetic landscape associated with extended

pluripotency. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:12019–12038. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Huang F, Zhao H, Du Z and Jiang H: miR-615

inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion by

directly targeting Cyclin D2. Oncol Res. 27:293–299. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Dong Q, Meng P, Wang T, Qin W, Qin W, Wang

F, Yuan J, Chen Z, Yang A and Wang H: MicroRNA let-7a inhibits

proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

by targeting E2F2 and CCND2. PLoS One. 5:e101472010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen X, Wu Y, Wang X, Xu C, Wang L, Jian

J, Wu D and Wu G: CDK6 is upregulated and may be a potential

therapeutic target in enzalutamide-resistant castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Eur J Med Res. 27:1052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yu Z, Zhan C, Du H and Zhang L, Liang C

and Zhang L: Baicalin suppresses the cell cycle progression and

proliferation of prostate cancer cells through the CDK6/FOXM1 axis.

Mol Cell Biochem. 469:169–178. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chakraborty G, Armenia J, Mazzu YZ,

Nandakumar S, Stopsack KH, Atiq MO, Komura K, Jehane L, Hirani R,

Chadalavada K, et al: Significance of BRCA2 and RB1 Co-loss in

aggressive prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res.

26:2047–2064. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ku SY, Rosario S, Wang Y, Mu P, Seshadri

M, Goodrich ZW, Goodrich MM, Labbé DP, Gomez EC, Wang J, et al: Rb1

and Trp53 cooperate to suppress prostate cancer lineage plasticity,

metastasis, and antiandrogen resistance. Science. 355:78–83. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Li Y, Wang F, Xu J, Ye F, Shen Y, Zhou J,

Lu W, Wan X, Ma D and Xie X: Progressive miRNA expression profiles

in cervical carcinogenesis and identification of HPV-related target

genes for miR-29. J Pathol. 224:484–495. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

McNair C, Urbanucci A, Comstock CE,

Augello MA, Goodwin JF, Launchbury R, Zhao SG, Schiewer MJ, Ertel

A, Karnes J, et al: Cell cycle-coupled expansion of AR activity

promotes cancer progression. Oncogene. 36:1655–1668. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Oner M, Lin E, Chen MC, Hsu FN, Shazzad

Hossain Prince GM, Chiu KY, Teng CJ, Yang TY, Wang HY, Yue CH, et

al: Future aspects of CDK5 in prostate cancer: From pathogenesis to

therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 20:38812019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zolochevska O and Figueiredo ML: Cell

cycle regulator cdk2ap1 inhibits prostate cancer cell growth and

modifies androgen-responsive pathway function. Prostate.

69:1586–1597. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Schiewer MJ, Augello MA and Knudsen KE:

The AR dependent cell cycle: Mechanisms and cancer relevance. Mol

Cell Endocrinol. 352:34–45. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Agus DB, Cordon-Cardo C, Fox W, Drobnjak

M, Koff A, Golde DW and Scher HI: Prostate cancer cell cycle

regulators: Response to androgen withdrawal and development of

androgen independence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 91:1869–1876. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Huggins C and Hodges CV: Studies on

prostatic cancer: I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of

androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of

the prostate. 1941. J Urol. 168:9–12. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Knudsen KE, Arden KC and Cavenee WK:

Multiple G1 regulatory elements control the androgen-dependent

proliferation of prostatic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem.

273:20213–20222. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lee YM and Sicinski P: Targeting cyclins

and cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer: Lessons from mice, hopes

for therapeutic applications in human. Cell Cycle. 5:2110–2114.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Malumbres M and Barbacid M: Cell cycle

kinases in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 17:60–65. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Sherr CJ and Roberts JM: Living with or

without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev.

18:2699–2711. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xu Y, Chen SY, Ross KN and Balk SP:

Androgens induce prostate cancer cell proliferation through

mammalian target of rapamycin activation and post-Transcriptional

increases in cyclin D proteins. Cancer Res. 66:7783–7792. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Knudsen ES and Knudsen KE: Tailoring to

RB: Tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response. Nat Rev

Cancer. 8:714–724. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Jain K, Jin CY and Clarke SG: Epigenetic

control via allosteric regulation of mammalian protein arginine

methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:10101–10106. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Jain K and Clarke SG: PRMT7 as a unique

member of the protein arginine methyltransferase family: A review.

Arch Biochem Biophys. 665:36–45. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|