Introduction

Metabolism serves as the fundamental basis of

cellular life, providing energy for biological processes, enabling

the biosynthesis of macromolecules and maintaining redox

homeostasis (1). The cellular

metabolic network, comprising the four core pathways, amino acid,

glucose, lipid and nucleotide metabolism, forms the structural and

functional foundation of cellular biochemistry (2). Amino acid metabolism occupies a

particularly pivotal position within this network due to its

notable diversity in molecular species and metabolic routes,

enabling its critical involvement in multiple cellular processes

(3–8). Emerging evidence has revealed that

deficiencies in essential amino acids, including tryptophan,

tyrosine, branched-chain amino acids (such as isoleucine, leucine

and valine), methionine, phenylalanine and threonine, can disrupt

lipid homeostasis, with potential implications for

neurodevelopmental disorders (9).

In diabetic murine models, depletion of serine and glycine has been

demonstrated to exacerbate neuropathy progression (10). A mechanistic study has further shown

that essential amino acid deficiency in hepatocytes leads to

functional impairment of ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component

n-recognin 1, causing aberrant ubiquitination and subsequent

degradation of the lipid droplet-stabilizing protein, perilipin 2.

This molecular cascade ultimately suppresses hepatic lipid

catabolism and promotes fatty liver pathogenesis (11).

To sustain their rapid proliferation, tumor cells

must overcome three fundamental metabolic demands: i) Rapid energy

production; ii) biosynthesis of macromolecules; and iii)

maintenance of redox homeostasis (1). Amino acids serve as essential

providers of both carbon and nitrogen sources, playing pivotal

roles in meeting these metabolic challenges. Consequently, amino

acid restriction therapies have emerged as a promising therapeutic

strategy against tumors (12–17).

Notably, the sulfur-containing amino acid, cysteine, assumes

particular importance in tumor metabolism, serving as a critical

precursor for glutathione (GSH) synthesis and providing cellular

protection against ferroptosis (18,19).

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death

characterized by three key metabolic features: i) The glutathione

peroxidase 4/GSH antioxidant system (dependent on cysteine

availability); ii) Fe2+-mediated Fenton reactions; and

iii) acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4

(ACSL4)-catalyzed biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty

acid-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PLs) (20). Notably, cellular cysteine can be

acquired through two distinct pathways: Exogenous uptake via the

solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) transporter or

endogenous synthesis from methionine via the methionine

adenosyltransferase 2A (MAT2A)-initiated transsulfuration pathway.

Both SLC7A11 and MAT2A are frequently upregulated in tumors, making

them attractive therapeutic targets (21–25).

Notably, ACSL4 plays a contradictory role in the occurrence and

development of tumors. On the one hand, ACSL4 can provide

biomacromolecules for tumor proliferation by regulating the

synthesis of PUFA-PLs (26). On the

other hand, an increase in PUFA-PLs levels also increases the

sensitivity of tumor cells to ferroptosis (27). Beyond their canonical roles in

protein biosynthesis and cellular metabolism, amino acids serve as

pivotal allosteric modulators that fine-tune metabolic flux through

the direct regulation of rate-limiting enzymes (28). While the crosstalk between amino

acid metabolism and glucose homeostasis has been extensively

characterized, particularly through the dynamic interconversion of

non-essential amino acid networks, the unidirectional nature of

amino acid-lipid metabolic interactions has resulted in

comparatively limited understanding of the amino acid-mediated

regulation of lipid metabolism.

The present study aimed to systematically

investigate the metabolic consequences of essential amino acid

deprivation, with particular emphasis on delineating the

mechanistic role of methionine in regulating intracellular lipid

homeostasis. To assess alterations in lipid metabolism, flow

cytometry coupled with fluorescent lipid probes were employed to

evaluate intracellular lipid accumulation and cellular fatty acid

uptake efficiency following essential amino acid deprivation.

Comprehensive analyses were performed to elucidate the underlying

molecular mechanisms of methionine-mediated lipid metabolic

regulation. Western blotting and reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR (RT-qPCR) were conducted to examine methionine

restriction-induced modulation of ACSL4 expression, a critical

regulator of fatty acid metabolism (27). Furthermore, the feedback regulation

within the methionine-MAT2A-S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) metabolic

axis was systematically investigated through combined western

blotting and RT-qPCR analyses, with a specific focus on the

SAM-dependent regulation of MAT2A protein stability and its

consequent impact on lipid metabolic homeostasis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (CRL-2991; ATCC)

and the HT1080, DU145 and H1299 cell lines were obtained from the

American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured following

ATCC recommendations. These cells were also subjected to STR

identification and mycoplasma testing. The cells were sustained in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with high glucose, sodium

pyruvate (1 mM), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml),

streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS;

MeisenCTCC; Zhejiang Meisen Cell Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C and

5% CO2. In addition, the cultivation conditions for

methionine deficiency are based on DMEM (cat. no. D0422;

MilliporeSigma) with high glucose, sodium pyruvate (1 mM),

glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml)

and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (MeisenCTCC) at 37°C and 5%

CO2. Alternatively, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM; 0.4 mM),

S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH; 0.4 mM), homocysteine (Hcy; 0.4 mM) or

adenosine dialdehyde (ADOX; 0.4 mM) were added separately to

methionine deficient culture medium to treat cells. Cells were also

treated with a constructed culture medium lacking essential amino

acids (isoleucine, 0.4 mM; isoleucine, 0.4 mM; lysine, 0.4 mM;

methionine, 0.4 mM; phenylalanine, 0.4 mM; threonine, 0.4 mM;

tryptophan, 0.4 mM; valine, 0.4 mM; histidine, 0.4 mM; and

arginine, 0.4 mM).

Reagents

The reagents used included propidium iodide (PI;

cat. no. P4170; MilliporeSigma), BODIPY581/591 C11 (cat. no. D3861;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), BODIPY (cat. no. HY-D1614;

MedChemExpress), BODIPY™ FL C12 (cat. no. D3822; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), SAM (cat. no. A7007; MilliporeSigma),

S-Adenosylhomocysteine (SAH; cat. no. A9384; MilliporeSigma),

homocysteine (cat. no. H4628; MilliporeSigma), anti-MAT2A (cat. no.

A19272; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), anti-ACSL4 (cat. no. A20414;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and DMEM with high glucose (cat. no.

D0422-100 ml; MilliporeSigma). In addition, all the components of

the D777 culture medium (with 4,500 mg/l glucose, L-glutamine and

sodium pyruvate, without sodium bicarbonate, powder, suitable for

cell culture) were purchased to construct an amino acid-deficient

culture medium. The medium mainly included methionine (cat. no.

M0960000), leucine (cat. no. L8000), isoleucine (cat. no. I2752),

lysine (cat. no. L5501), phenylalanine (cat. no. P17008), tyrosine

(cat. no. T1145), tryptophan (cat. no. T0254), valine (cat. no.

V0500), histidine (cat. no. H8125) and arginine (cat. no. A5006),

all from MilliporeSigma.

Fatty acid uptake and intracellular

lipid detection

Fatty acid uptake was measured by flow cytometry.

Briefly, HT1080 and H1299 cells were plated at a density of

5×104 cells per well in a 24-well dish and cultured for

12 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and

streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Subsequently, 2 µM

BODIPY-C12 was added to the cell culture medium and incubated for

10 h alongside the indicated treatment. Following this, the cells

were trypsinized, washed with PBS containing 5% FBS and resuspended

in 0.3 ml of PBS with 5% FBS for flow cytometry analysis (Attune

NxT; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Acquired data were analyzed

using FlowJo version 10 software (FlowJo LLC). A minimum of 10,000

cells were analyzed per condition. Intracellular lipids were also

measured by flow cytometry (Attune NxT.). Acquired data were

analyzed using FlowJo version 10 software. The protocol was the

same as that aforementioned except 1 µg/ml BODIPY was added to the

cell culture medium and incubated for 30 min after the indicated

treatment.

Lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS)

detection

Lipid ROS were analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly,

cells were plated at a density of 1×105 cells per well

in a 24-well dish and cultured overnight in DMEM. Subsequently, 4

µM BODIPY581/591 C11 was added to the cell culture medium and

incubated for 30 min after the indicated treatment. Excess

BODIPY581/591 C11 was then removed by washing the cells with PBS

twice. Labeled cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS with

5% FBS. Oxidation of BODIPY581/591 C11 resulted in a shift of the

fluorescence emission peak from 590 to 510 nm proportional to the

lipid ROS generation, which was detected using a flow cytometer

(Attune NxT). Acquired data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10

software.

Cell death detection

Cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly,

cells were plated at a density of 2×105 cells per well

in a 12-well dish for 12 h in fresh medium. After the indicated

treatment, 1 µg/ml PI was added to the cell culture medium and

incubated for 30 min. Then, cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS

containing 5% FBS and resuspended in 0.3 ml of PBS with 5% FBS for

flow cytometry (Attune NxT). Acquired data were analyzed using

FlowJo software.

Apoptosis detection

Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly,

cells were plated in 12-well culture plates at a density of

1×105 cells per well and cultured in DMEM for 12 h.

Cells were then trypsinized, washed with PBS containing 5% FBS and

resuspended in 0.3 ml of PBS. Subsequently, PI and Annexin V-FITC

were added to the cells and incubated for 30 min, and cell

apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry (Attune NxT). Acquired

data were analyzed using FlowJo.

Transfections

Transfections were conducted using

Lipofectamine™ 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. HT1080 cells seeded in a 6-well dish were transfected

with 40 ng of the following small interfering RNAs (Suzhou

GenePharma Co., Ltd.): NC (scrambled), sense:

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUUTT-3′, antisense:

5′-AACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′; MAT2A-1, sense:

5′-GGAUCGAGGUGCUGUGCUUTT-3′, antisense: 5′AAGCACAGCACCUCGAUCCTT-3′;

MAT2A-2, sense: 5′-GGGAUGCCCUAAAGGAGAATT-3′, antisense:

5′-UUCUCCUUUAGGGCAUCCCTT-3′ and MAT2A-3, sense:

5′-GCCUAUGGCCACUUUGGUATT-3′, antisense:

5′-UACCAAAAGUGGCCAUAGGCTT-3′. After transfection, the cells were

placed in a 37°C cell culture incubator and the medium was changed

after 8 h. After 48 h, the cells were lysed and the interference

efficiency was measured using western blotting.

Western blotting

Cell lysate preparation, SDS-PAGE and

electrophoretic transference were accomplished as previously

described (19). Briefly, the

protein sample was quantified using a NanoPhotometer®

N30 Touch and each lane of the 8% SDS gel was loaded with 10 µg

protein sample. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk

in TBS (pH 7.2) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), incubated with the

appropriate primary antibodies in 5% non-fat dried milk in TBST

overnight at 4°C. Then, the membrane was incubated with the

appropriate secondary antibodies in 5% non-fat dried milk in TBST

at room temperature for 50 min. The following primary antibodies

were used: Anti-MAT2A, anti-ACSL4 and β-actin (cat. no. HC201-01;

TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). The following secondary antibodies

were used: HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (cat. no. AS014;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse

(cat. no. AS003; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). Chemiluminescence was

detected using the ChampChemi 610 (SinSage Technology Co., Ltd.),

and the software used for densitometry was ImageJ (National

Institutes of Health).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRNzol

(cat. no. DP424; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and reverse transcribed

with the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser

(cat. no. RR047A; Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The resulting cDNA was then subjected to qPCR using the

TB Green Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNase H Plus) (cat. no.

RR820A; Takara Bio, Inc.). The detection and analysis were

accomplished as previously described (19). The sequences of the primers used for

qPCR were as follows: ACSL4 (human) forward,

5′-CATCCCTGGAGCAGATACTCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCACTTAGGATTTCCCTGGTCC-3′; MAT2A (human) forward,

5′-ACCAGAAAGTGGTTCGTGAAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-CAAGGCTACCAGCACGTTACA-3′; MAT2B (human) forward,

5′-TTCACTGGTCTGGCAATGAAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGGGCTGTCAGTAATAGGTCTT-3′; MAT2A (mouse) forward,

5′-GCTTCCACGAGGCGTTCAT-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGCATCACTGATTTGGTCACAA-3′; MAT2B (mouse) forward,

5′-AGGGAACCTTTCACTGGTCTG-3′ and reverse

5′-ATTTGGAGCAATCGAGCTGAG-3′; β-actin (human) forward,

5′-GTTGTCGACGACGAGCG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCACAGAGCCTCGCCTT-3′; and

β-actin (mouse) forward, 5′-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3′.

Public database analyses

ACLS4 expression in cancer

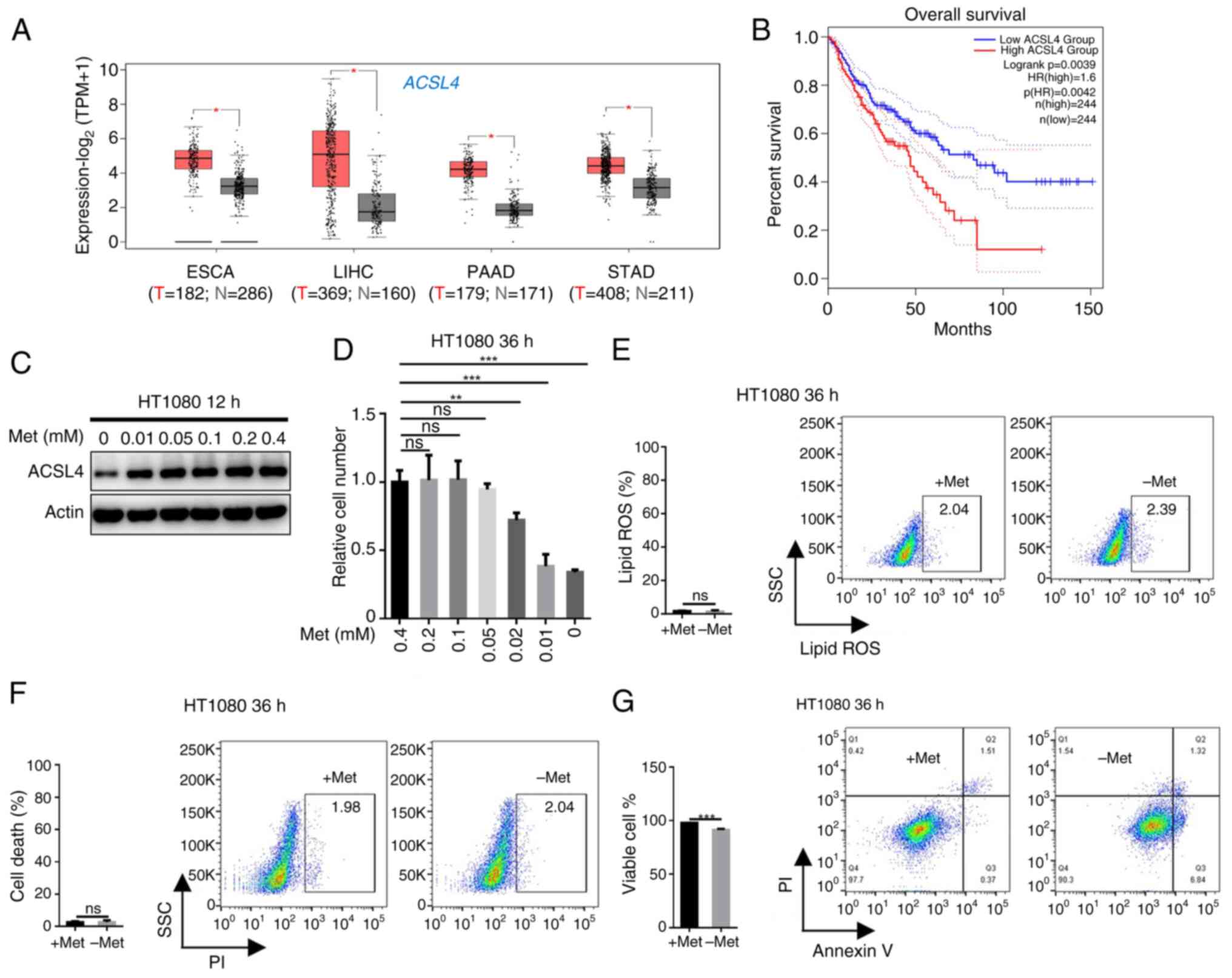

The expression levels of ACSL4 in tumor and

normal tissues were analyzed using the Expression DIY module on the

GEPIA 2 website (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index). The analysis

parameter settings were as follows: Log2 FC cut-off (1); q-value cut-off (0.01); log scale

(yes); jitter size (0.4); and matched normal data (match TCGA

normal and GTEx data).

Overall survival

The survival analysis module on the GEPIA 2 website

was used to analyze the relationship between ACSL4 expression and

patient survival. The analysis parameter settings were as follows:

Methods (overall survival); group cut-off (median); cut-off high

(%) (50); cut-off low (%) (50); hazard ratio (yes); 95% confidence

interval (yes); and axis units (months).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (v.10.4.0; Dotmatics) software was

used to calculate the P-values using two-sided unpaired t-test or

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference.

All data presented in the figures represent the mean ± SD.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Methionine restriction downregulates

cellular lipid levels

To systematically evaluate the role of essential

amino acids in lipid metabolism regulation, an essential amino

acid-deficient culture system was established by excluding leucine,

isoleucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine,

tryptophan, valine, histidine and arginine from the medium. HT1080

cells cultured in this modified medium were subsequently analyzed

for intracellular lipid accumulation using BODIPY staining.

Quantitative analysis revealed that methionine deprivation

specifically caused a significant reduction in cellular lipid

content (Fig. 1A). Next, the

functional consequences of essential amino acid deficiency on fatty

acid uptake capacity were examined using BODIPY-C12 fluorescence

assays. Notably, methionine-deficient conditions produced a notable

impairment in fatty acid internalization among all tested amino

acid deprivations (Fig. 1B).

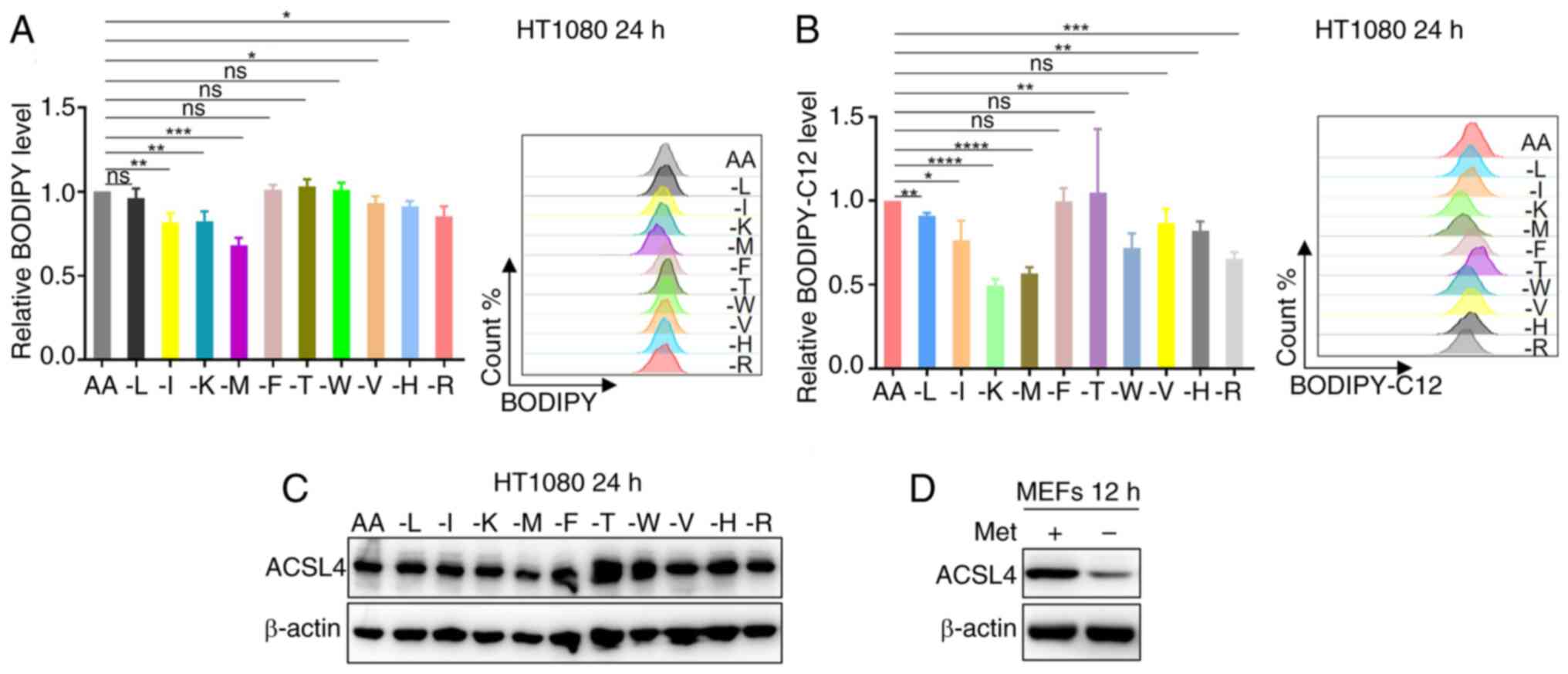

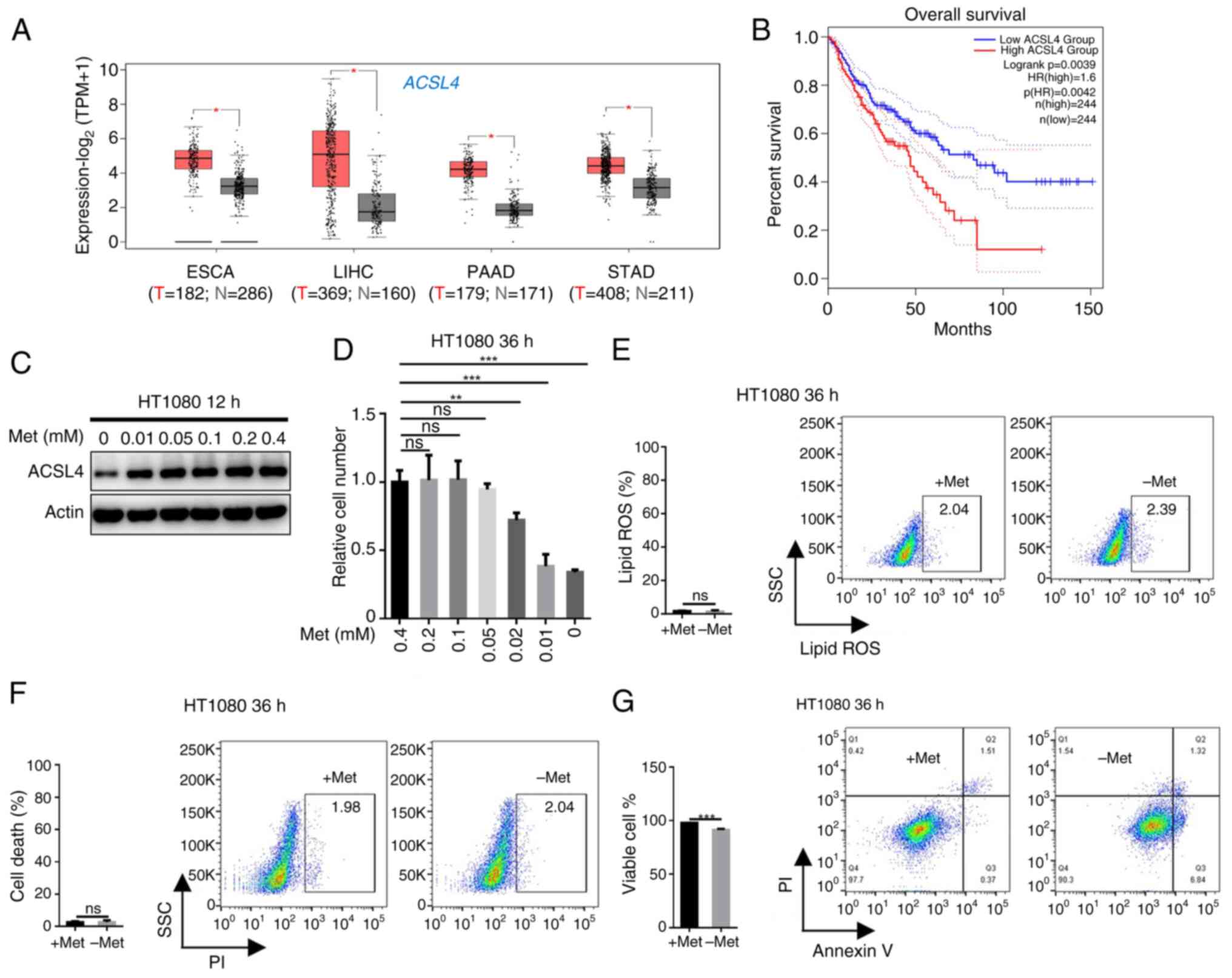

| Figure 1.Methionine restriction downregulates

cellular lipid levels. (A) HT1080 cells were cultured without

leucine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine,

tryptophan, valine, histidine or arginine as indicated for 24 h,

and the intracellular lipids were determined by BODIPY staining

coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (B) HT1080 cells were cultured

without leucine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine,

tyrosine, tryptophan, valine, histidine, or arginine as indicated

for 24 h, and fatty acid uptake capacity was determined by

BODIPY-C12 staining coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (C) Western

blot analysis of ACSL4 expression in HT1080 cells treated with

medium without leucine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine,

phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, valine, histidine or arginine

as indicated for 24 h. (D) Western blot analysis of ACSL4

expression in MEFs cells treated with medium without methionine for

12 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD with P-values determined

by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant

Difference. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. AA, all amino acids; L, isoleucine; I, isoleucine;

K, lysine; M, methionine; F, phenylalanine; T, threonine; W,

tryptophan; V, valine; H, histidine; R, arginine; ACSL4, acyl-CoA

synthetase long chain family member 4; MEFs, mouse embryonic

fibroblasts; Met, methionine. |

Given the established role of ACSL4 in facilitating

fatty acid uptake through its dual function of converting fatty

acids to acyl-CoA derivatives and inhibiting fatty acid efflux,

ACSL4 protein expression in HT1080 cells under essential amino acid

deprivation conditions was first examined. Western blot analysis

revealed that methionine deficiency reduced the ACSL4 protein

levels (Fig. 1C). To validate this

finding across different cellular contexts, the investigation was

extended to MEFs under methionine-restricted conditions. Consistent

with the initial observation, methionine deprivation significantly

decreased ACSL4 expression in MEFs cells (Fig. 1D). Taken together, the results

suggest that methionine deficiency attenuates cellular lipid

accumulation and the fatty acid uptake capacity, potentially

through downregulation of ACSL4 protein expression, revealing a

novel mechanistic link between methionine availability and lipid

metabolic regulation.

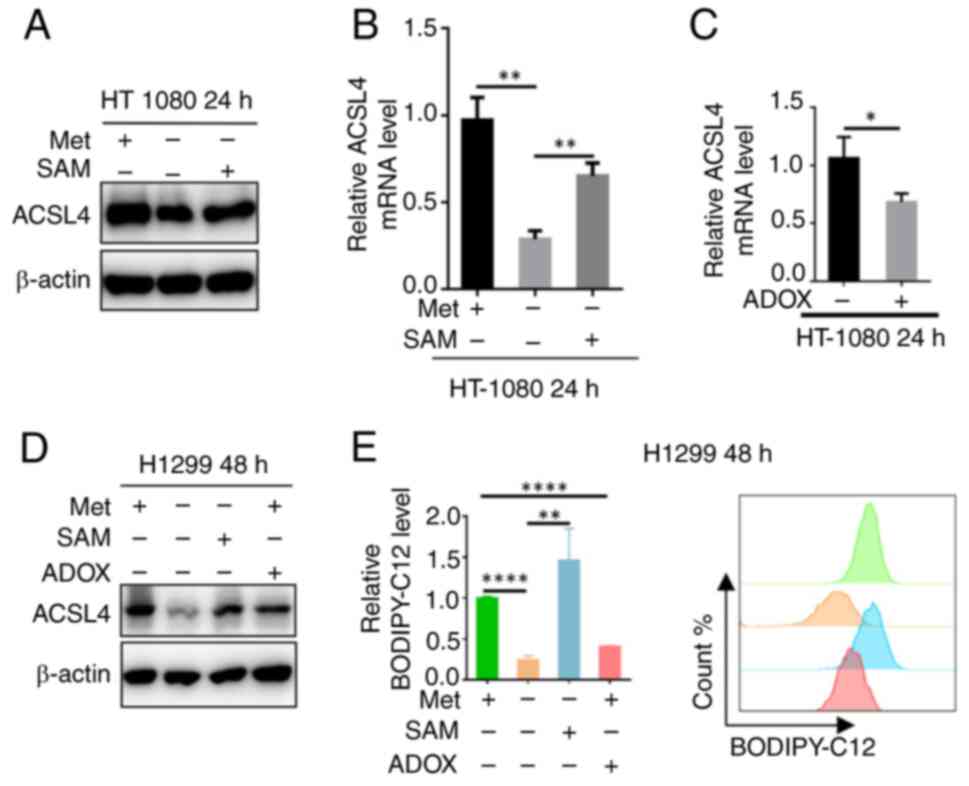

Methionine regulates ACSL4 through

SAM

As the sulfur-containing amino acid methionine

functions as a vital cellular methyl donor primarily through its

metabolic derivative SAM, it was next determined whether methionine

regulates ACSL4 expression and fatty acid uptake capacity via

SAM-dependent mechanisms. To test this hypothesis, methionine

deprivation experiments in HT1080 cells were performed followed by

SAM supplementation. Western blot analysis demonstrated that SAM

administration rescued the methionine deficiency-induced reduction

in ACSL4 protein levels (Fig. 2A).

Complementary RT-qPCR analysis further revealed that SAM

supplementation similarly restored the suppressed ACSL4 mRNA

expression under methionine-depleted conditions (Fig. 2B). To elucidate whether SAM

regulates ACSL4 expression through methylation-dependent

mechanisms, HT1080 cells were treated with the methylation

inhibitor, adenosine dialdehyde (ADOX), and the ACSL4

transcript levels were analyzed. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that

ADOX treatment significantly suppressed ACSL4 mRNA

expression (Fig. 2C), indicating

methylation-dependent regulation. This regulatory mechanism in

H1299 cells was further validated, as western blot analysis

confirmed that the methionine-SAM axis controls ACSL4 protein

abundance possibly through methylation modifications (Fig. 2D). Functional assays demonstrated

that this methylation-dependent regulation directly impacts

cellular fatty acid uptake capacity (Fig. 2E). Collectively, these results

establish that SAM-mediated methylation may represent a critical

epigenetic mechanism through which methionine regulates

ACSL4 expression and function in lipid metabolism.

MAT2A can be dynamically regulated by

the level of SAM

As the key enzyme catalyzing methionine-to-SAM

conversion, MAT2A occupies a central position in the methionine-SAM

metabolic axis (24). To

investigate whether MAT2A serves as a critical regulator of SAM

homeostasis and lipid metabolism, MAT2A protein expression in

HT1080 cells under essential amino acid deprivation was first

examined. Western blot analysis revealed that the MAT2A levels were

specifically upregulated by methionine deficiency (Fig. 3A). Using a dose-response approach,

it was demonstrated that MAT2A expression exhibits sensitivity to

extracellular methionine concentrations in DU145 cells (Fig. 3B). Notably, SAM supplementation

reversed the observed methionine deprivation-induced MAT2A

upregulation (Fig. 3C), suggesting

a feedback regulatory mechanism. Further mechanistic studies in

H1299 cells showed that MAT2A protein levels remained unchanged

following ADOX-mediated methylation inhibition, compared with the

methionine deprivation only group (Fig.

3D). Consistent with this result, transcriptional analysis

across multiple cell lines (MEFs, HT1080 and H1299) revealed that,

while the methionine-SAM axis regulates MAT2A mRNA

expression, this control occurs independently of the

methyltransferase activity of SAM (Fig.

3E). Notably, the regulatory subunit, MAT2B, was unaffected by

these metabolic perturbations (Fig.

3F). These results establish that MAT2A is subject to

SAM-mediated feedback regulation through a novel

methylation-independent mechanism, highlighting the sophisticated

control of methionine metabolism.

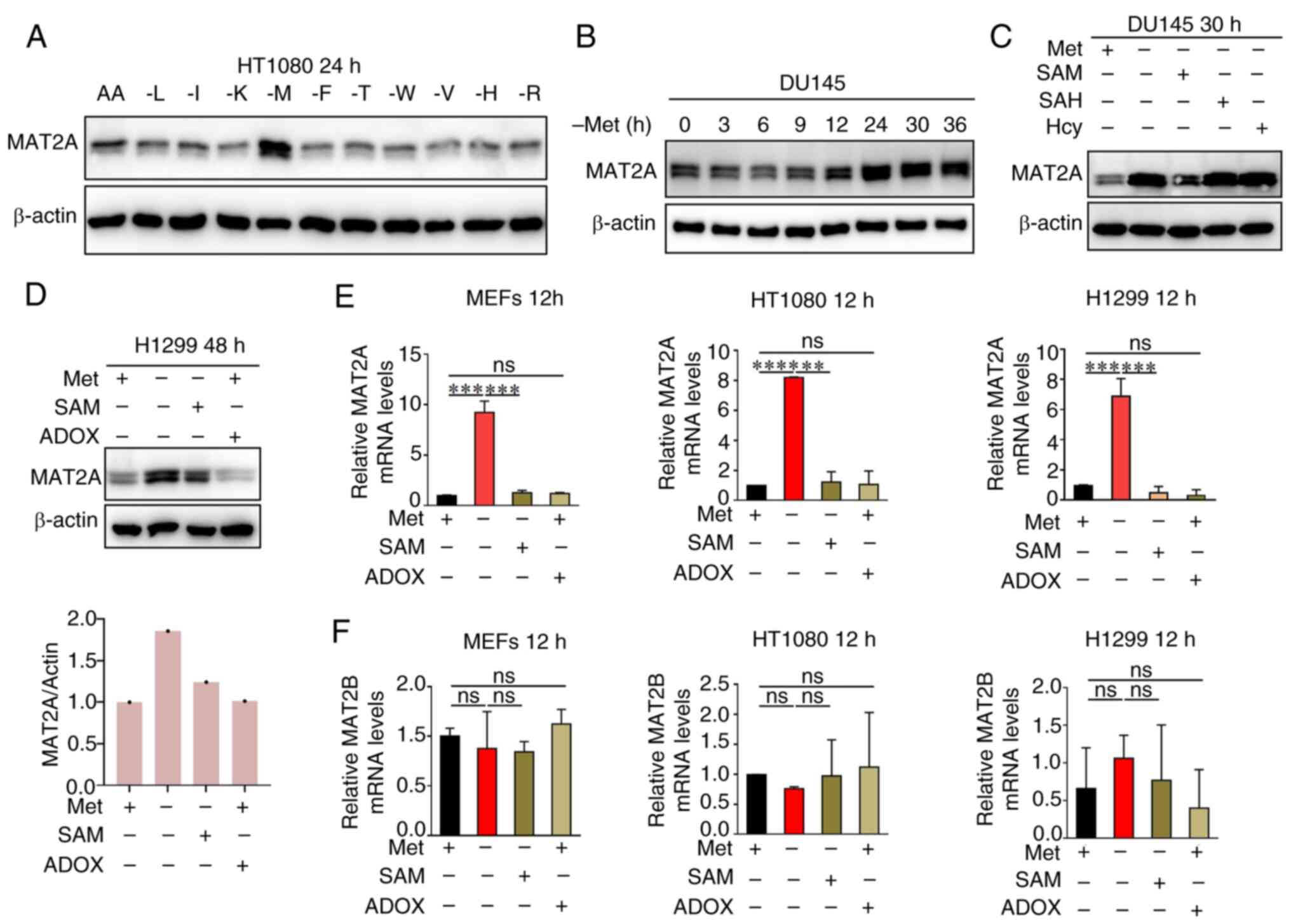

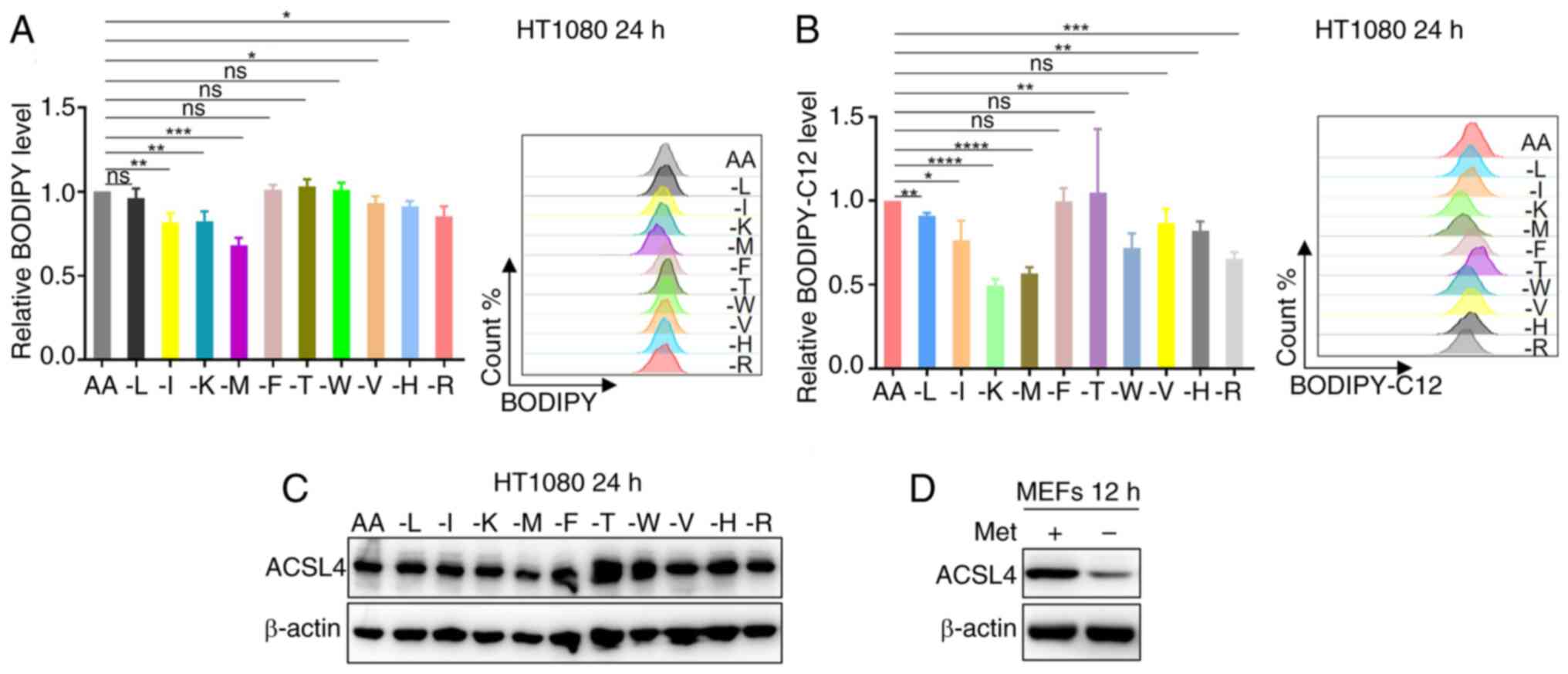

| Figure 3.MAT2A can be dynamically regulated by

the level of SAM. (A) Western blot analysis of MAT2A expression in

HT1080 cells treated with medium without leucine, isoleucine,

lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, valine,

histidine, or arginine as indicated for 24 h. (B) Western blot

analysis of MAT2A expression in DU145 cells treated with medium

without methionine as indicated for 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 30 and 36

h. (C) Western blot analysis of MAT2A expression in DU145 cells

cultured ± methionine, ± SAM, ± SAH or ± Hcy as indicated for 30 h.

(D) Western blot analysis of MAT2A expression in H1299 cells

cultured ± methionine, ± SAM or ± ADOX, as indicated for 48 h. The

(E) MAT2A and (F) MAT2B mRNA levels in MEFs and

HT1080 and H1299 cells cultured ± methionine, ± SAM or ± ADOX as

indicated for 12 h, were analyzed using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (n=3). Data are presented as mean ±

SD with P-values determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

Honestly Significant Difference. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. ns, non-significant; AA, all amino acids; L,

isoleucine; I, isoleucine; K, lysine; M, methionine; F,

phenylalanine; T, threonine; W, tryptophan; V, valine; H,

histidine; R, arginine; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; SAM,

S-adenosylmethionine; ADOX, adenosine dialdehyde; SAH,

S-adenosylhomocysteine; Hcy, homocysteine; MAT2A/B, methionine

adenosyltransferase 2A/B; Met, methionine. |

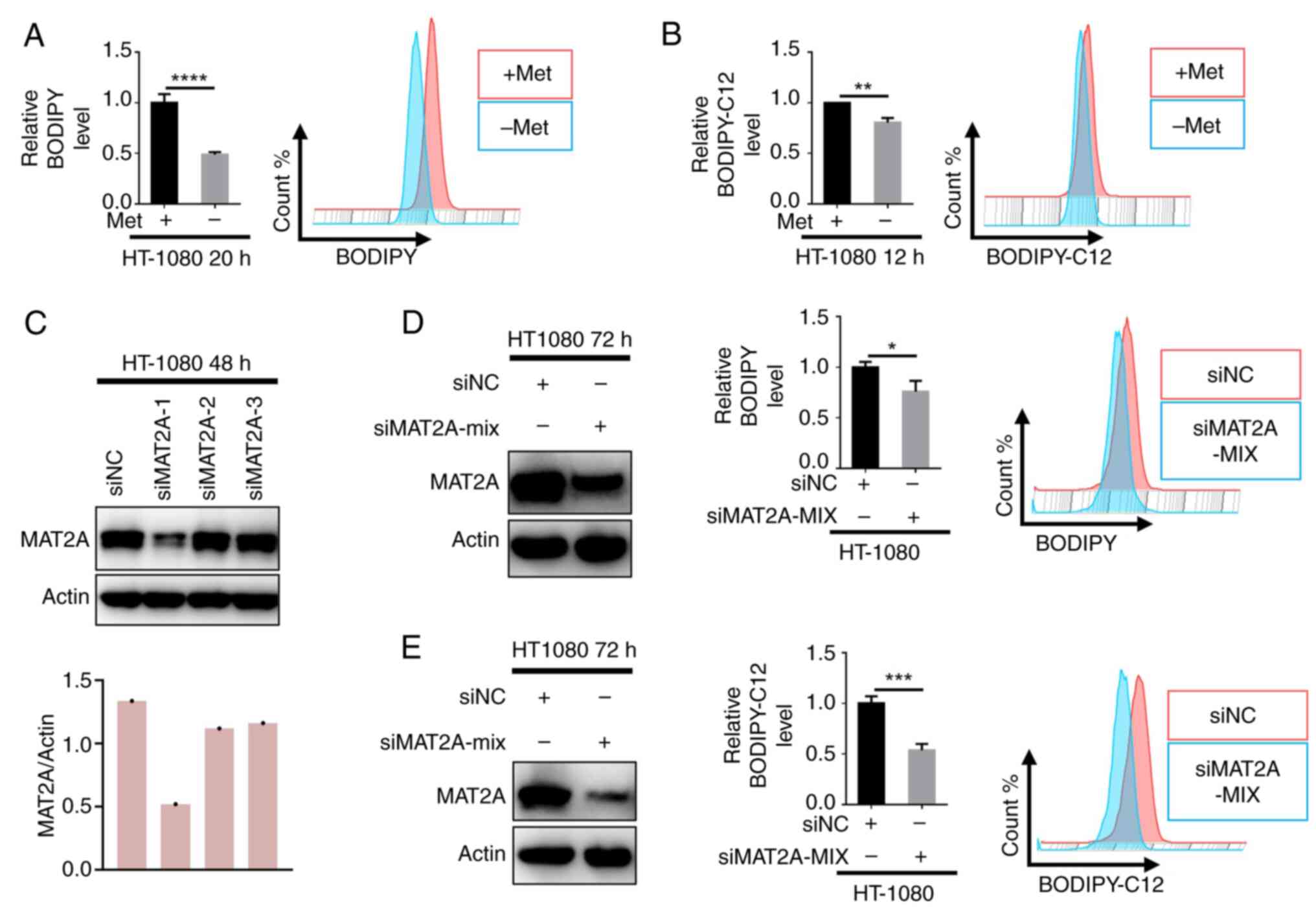

Knocking down MAT2A reduces

intracellular lipid levels

To systematically validate the regulatory role of

methionine in lipid metabolism, complementary experimental

approaches were performed using HT1080 cells. First, methionine

deprivation (using commercial methionine deficient medium) led to

significant reductions in both intracellular lipid accumulation

(BODIPY staining) and fatty acid uptake capacity (BODIPY-C12 assay)

(Fig. 4A and B). To directly assess

the involvement of MAT2A in these metabolic processes, RNA

interference-mediated knockdown was employed. MAT2A downregulation

similarly reduced the intracellular lipid content (Fig. 4C and D) and impaired fatty acid

internalization (Fig. 4E),

phenocopying the effects of methionine deprivation. These

consistent findings across orthogonal experimental approaches

establish MAT2A as a key metabolic regulator and potential

therapeutic target for modulating cellular lipid homeostasis.

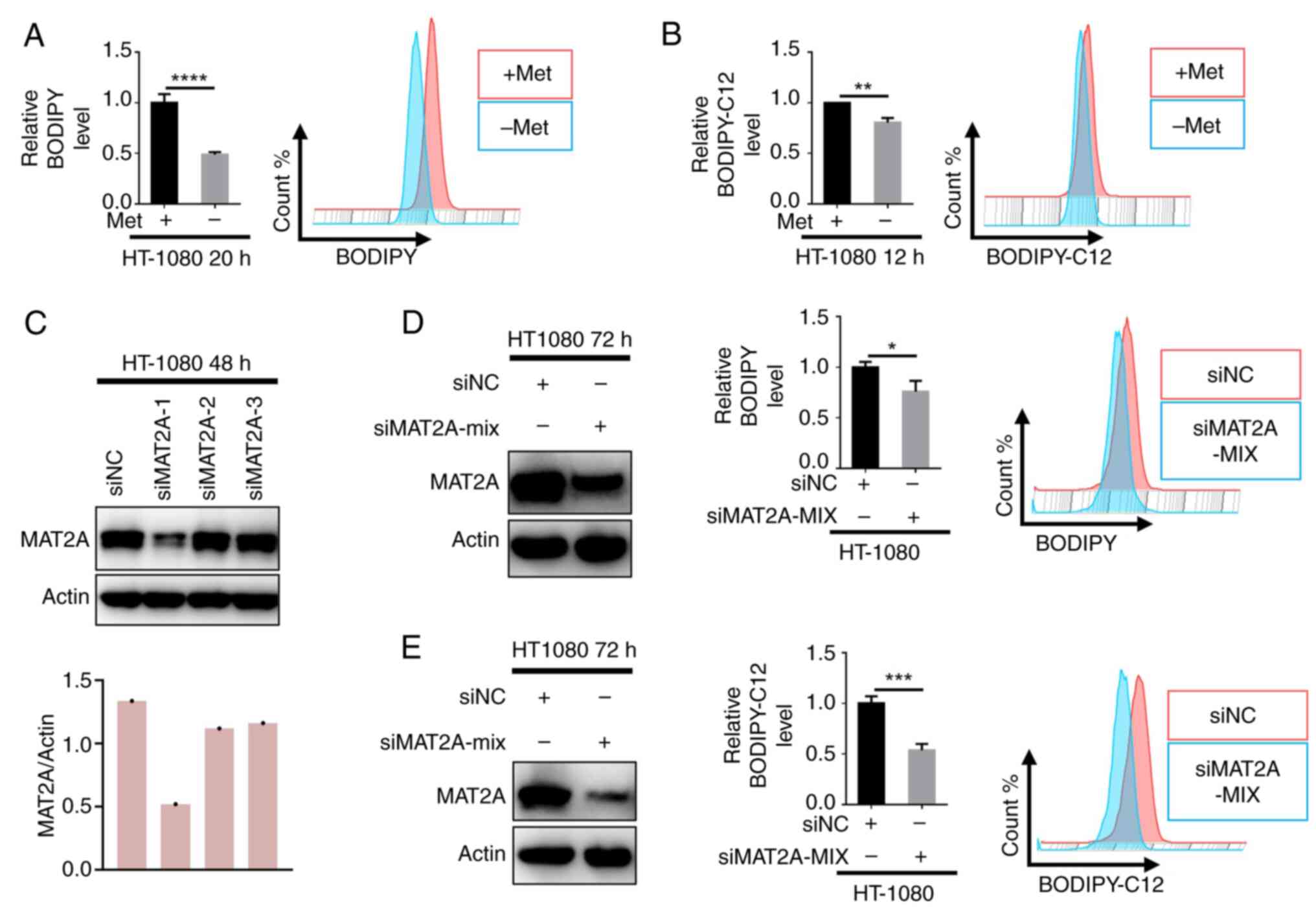

| Figure 4.Knocking down MAT2A expression

reduces the intracellular lipid levels. (A) HT1080 cells were

cultured ± methionine as indicated for 20 h, and the intracellular

lipids were determined by BODIPY staining coupled with flow

cytometry (n=3). (B) HT1080 cells were cultured ± methionine as

indicated for 12 h, and fatty acid uptake capacity was determined

by BODIPY-C12 staining coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (C)

Western blot analysis of MAT2A expression in HT1080 cells

transfected with siMAT2A or siNC. (D) The intracellular lipids in

HT1080 cells transfected with siMAT2A or siNC were determined by

BODIPY staining coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (E) Fatty acid

uptake capacity in HT1080 cells transfected with siMAT2A or siNC

was determined by BODIPY-C12 staining coupled with flow cytometry

(n=3). Data are presented as mean ± SD, with P-values determined by

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. MAT2A,

methionine adenosyltransferase 2A; si, small interfering (RNA); NC,

negative control; Met, methionine. |

Methionine restriction suppresses

tumor cell proliferation by inhibiting ACLS4

Lipids serve as fundamental structural components of

cellular membranes and play a critical role in supporting the rapid

proliferation of tumor cells. The aforementioned results

demonstrated that methionine functions as a positive regulator of

intracellular lipid homeostasis. Analysis of The Cancer Genome

Atlas datasets revealed elevated ACSL4 expression in

multiple malignancies, including esophageal carcinoma, liver

hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma and stomach

adenocarcinoma (Fig. 5A). Notably,

high ACSL4 expression was significantly associated with

poorer overall survival in patients with cancer, including

cholangiocarcinoma, esophageal carcinoma and colon adenocarcinoma

(Fig. 5B), suggesting its clinical

relevance as a potential prognostic marker. Functional studies in

HT1080 cells showed that methionine deprivation simultaneously

suppressed ACSL4 expression (Fig. 5C) and impaired HT1080 cell

proliferation (Fig. 5D), while not

inducing ferroptosis (Fig. 5E and

F); however, it has a certain inducing effect on apoptosis

(Fig. 5G). Taken together, these

results establish methionine as an essential metabolic requirement

for tumor cell proliferation, operating through ACSL4-mediated

lipid metabolic pathways.

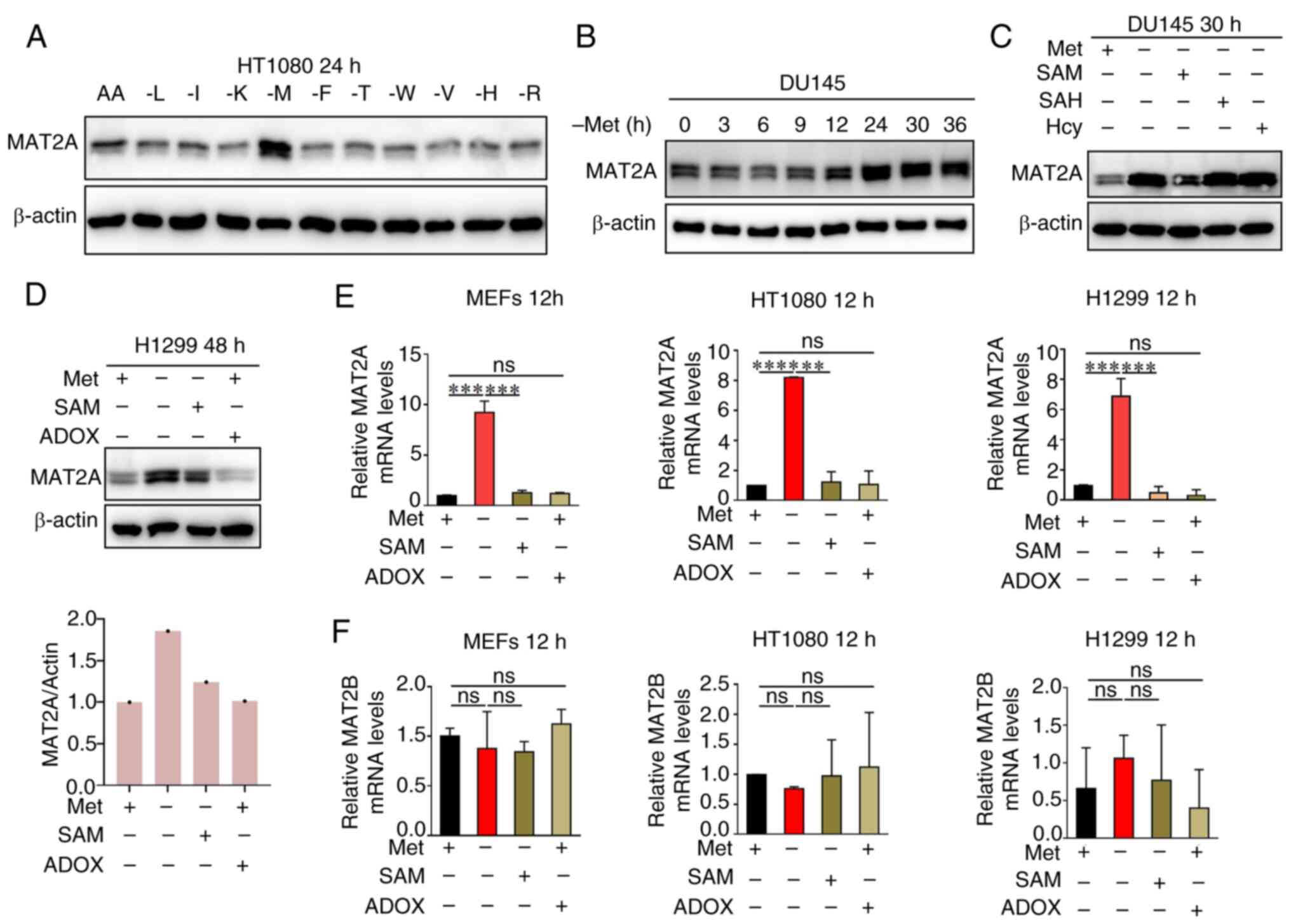

| Figure 5.Methionine restriction suppresses

tumor cell proliferation by inhibiting ACLS4. (A) Analysis of

ACSL4 expression in tumor and adjacent tissues based on TCGA

database. (B) Analysis of the correlation between ACSL4 expression

and overall survival based on TCGA database through GEPIA2

(http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/). (C)

Western blot analysis of ACSL4 expression in HT1080 cells treated

with medium without methionine as indicated for 12 h. (D) The

number of HT1080 cells after methionine deprivation as indicated

for 36 h were counted using a microscope and cell counter (n=3).

(E) HT1080 cells were cultured ± methionine as indicated for 36 h

and the lipid ROS level was determined by BODIPY-C11 staining

coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (F) HT1080 cells were cultured ±

methionine as indicated for 36 h and cell death was determined by

PI staining coupled with flow cytometry (n=3). (G) HT1080 cells

were cultured ± methionine as indicated for 36 h and cell apoptosis

was determined by PI staining coupled with flow cytometry (n=3).

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with P-values determined by

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ns, non-significant; TCGA,

The Cancer Genome Atlas; TPM, transcripts per million; ESCA,

esophageal carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; PAAD,

pancreatic adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; T, tumor;

N, normal; HR, hazard ratio; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain

family member 4; SSC, side Scatter; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

PI, propidium iodide; Met, methionine. |

Discussion

Amino acid metabolism serves as a critical metabolic

hub supporting the biosynthetic and energetic demands of rapidly

proliferating tumor cells. Among the essential amino acids,

methionine, a sulfur-containing metabolite with pleiotropic

functions, has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in

oncology (14,29). The present study identified a unique

role for methionine in governing lipid homeostasis, demonstrating

its superior capacity to modulate intracellular lipid accumulation

and fatty acid uptake compared with other essential amino acids.

Mechanistically, it was established that methionine exerts this

control through SAM-dependent regulation of ACSL4, a master

regulator of fatty acid metabolism (27). Downregulation of MAT2A, the

rate-limiting enzyme in methionine-to-SAM conversion (24), phenocopied methionine deprivation by

reducing lipid stores and impairing fatty acid internalization.

Notably, these metabolic perturbations translated to significant

anti-proliferative effects in tumor cells, highlighting the

therapeutic potential of targeting methionine metabolism.

Furthermore, methionine restriction has emerged as a promising

therapeutic strategy in oncology, primarily through its depletion

of SAM, the universal methyl donor critical for numerous cellular

processes (30–32). The present study extends this

paradigm by revealing an additional mechanism whereby methionine

restriction impairs tumor proliferation through ACSL4

downregulation-mediated inhibition of fatty acid uptake. The

therapeutic potential of targeting methionine metabolism is further

underscored by the frequent upregulation of MAT2A across diverse

malignancies (33,34). In view of this, MAT2A has become an

important target for cancer treatment, and inhibitors developed

around it are constantly emerging (24,35,36).

Notably, the MAT2A inhibitor, AG-270, has entered phase I clinical

trials as a potential therapeutic agent for malignant tumors

(24). Furthermore, ACSL4, a

crucial enzyme in lipid metabolism regulation, has been

demonstrated to facilitate metastatic extravasation in ovarian

cancer through its enhancement of membrane fluidity and cellular

invasiveness (37). Consequently,

targeted disruption of the methionine-MAT2A-ACSL4 axis represents a

potential therapeutic strategy to simultaneously suppress tumor

proliferation and metastasis.

MAT2A is essential for maintaining intracellular SAM

homeostasis. Emerging evidence indicates that the regulatory

subunit, MAT2B, mediates SAM-dependent feedback inhibition of MAT2A

activity (38–41). In addition, the present study

extended these findings by demonstrating that: i) Methionine

deprivation upregulates MAT2A expression; ii) SAM supplementation

suppresses this induction; and iii) this regulatory mechanism

operates independently of the methyltransferase activity of SAM. We

hypothesize that mTORC1 may serve as a key mediator in

SAM-dependent regulation of MAT2A expression. This speculation is

supported by existing evidence demonstrating that mTORC1 can

modulate MAT2A expression through its downstream effector, MYC

(42). Furthermore, a study has

suggested that SAM may exert feedback control on MAT2A through the

SAM sensor, SAMTOR, which interfaces with both the mTORC1 and MYC

signaling pathways (43).

Therefore, the feedback regulation of MAT2A by SAM contributes to

the steady-state of methionine-MAT2A-SAM.

ACSL4, a key regulator of lipid metabolism,

catalyzes the ATP-dependent conversion of fatty acids to acyl-CoA

esters. Extensive studies have established that ACSL4 governs

cellular fatty acid uptake capacity by maintaining the

intracellular acyl-CoA pool (44,45).

The present study revealed that methionine deprivation decreased

ACSL4 protein abundance, leading to impaired fatty acid

internalization. In future research, the construction of isogenic

ACSL4-knockout cell lines will be critical for characterizing

ACSL4-dependent lipid metabolic pathways and for determining

whether methionine restriction can further modulate intracellular

lipid dynamics in ACSL4-deficient contexts. Notably, this lipid

metabolic perturbation can be rescued by SAM supplementation,

suggesting SAM-dependent regulation of ACSL4. However, the

molecular mechanisms underlying SAM-mediated control of ACSL4

expression and activity require further investigation. Previous

evidence provides important mechanistic insights into this

regulatory process. A previous study demonstrated that SAM

modulates mTORC1 activity through its sensor protein, SAMTOR

(43). As a central

nutrient-sensing hub, mTORC1 plays a pivotal role in coordinating

cellular anabolism and metabolic reprogramming. Notably, mTORC1 has

been shown to directly regulate ACSL4 expression (46). Based on these established

relationships, we propose a model wherein SAM regulates ACSL4

levels through SAMTOR-mediated modulation of mTORC1 signaling

activity.

As the primary product of the methionine-MAT2A-SAM

metabolic axis, SAM serves as the universal methyl donor for

diverse biological methylation reactions, including protein, DNA,

RNA and small molecule modifications (47). Given this extensive substrate

diversity, we hypothesize that the regulatory mechanisms by which

the methionine-MAT2A-SAM axis influences ACSL4 and lipid metabolism

remain incompletely characterized. Furthermore, the additional role

of SAM as a precursor for polyamine biosynthesis (48) suggests potential cross-regulation

between polyamine metabolism and ACSL4-mediated lipid pathways.

Collectively, these observations highlight the multifaceted

regulatory capacity of the methionine-MAT2A-SAM axis in cellular

metabolism.

The present study has certain limitations. Notably,

the BODIPY probe used in the present study functions as a

broad-spectrum lipid stain, lacking molecular specificity.

Consequently, while this method effectively detects overall lipid

uptake, it does not discriminate between distinct lipid species.

This represents a limitation of the current approach, as it

precludes detailed characterization of the specific lipid subtypes

involved in the observed processes.

In conclusion, the present study elucidated a novel

regulatory mechanism by which methionine governs cellular lipid

homeostasis through modulation of fatty acid uptake. These findings

establish the methionine-MAT2A-SAM axis as a central metabolic

regulator and reveal its therapeutic potential for targeted cancer

interventions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Zhejiang Sci-Tech

University Research Start-up Fund (grant no. 24042191-Y).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CX conceived the project, designed the research and

led the entire experiment, from design to execution. JM assisted

with the experiments. CX analyzed the data and wrote the

manuscript. CX and JM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cairns RA, Harris IS and Mak TW:

Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:85–95.

2011. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mossmann D, Park S and Hall MN: mTOR

signalling and cellular metabolism are mutual determinants in

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:744–757. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wang W and Zou W: Amino acids and their

transporters in T cell immunity and cancer therapy. Mol Cell.

80:384–395. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yoneshiro T, Wang Q, Tajima K, Matsushita

M, Maki H, Igarashi K, Dai Z, White PJ, McGarrah RW, Ilkayeva OR,

et al: BCAA catabolism in brown fat controls energy homeostasis

through SLC25A44. Nature. 572:614–619. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gao X, Locasale JW and Reid MA: Serine and

methionine metabolism: Vulnerabilities in lethal prostate cancer.

Cancer Cell. 35:339–341. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kelly B and Pearce EL: Amino assets: How

amino acids support immunity. Cell Metab. 32:154–175. 202

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Labuschagne CF, van den Broek NJ, Mackay

GM, Vousden KH and Maddocks OD: Serine, but not glycine, supports

one-carbon metabolism and proliferation of cancer cells. Cell Rep.

7:1248–1258. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Longchamp A, Mirabella T, Arduini A,

MacArthur MR, Das A, Treviño-Villarreal JH, Hine C, Ben-Sahra I,

Knudsen NH, Brace LE, et al: Amino acid restriction triggers

angiogenesis via GCN2/ATF4 regulation of VEGF and H(2)S production.

Cell. 173:117–129.e14. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Knaus LS, Basilico B, Malzl D, Gerykova

Bujalkova M, Smogavec M, Schwarz LA, Gorkiewicz S, Amberg N, Pauler

FM, Knittl-Frank C, et al: Large neutral amino acid levels tune

perinatal neuronal excitability and survival. Cell.

186:1950–1967.e25. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Handzlik MK, Gengatharan JM, Frizzi KE,

McGregor GH, Martino C, Rahman G, Gonzalez A, Moreno AM, Green CR,

Guernsey LS, et al: Insulin-regulated serine and lipid metabolism

drive peripheral neuropathy. Nature. 614:118–124. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang Y, Lin S, Peng J, Liang X, Yang Q,

Bai X, Li Y, Li J, Dong W, Wang Y, et al: Amelioration of hepatic

steatosis by dietary essential amino acid-induced ubiquitination.

Mol Cell. 82:1528–1542.e10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Schulte ML, Fu A, Zhao P, Li J, Geng L,

Smith ST, Kondo J, Coffey RJ, Johnson MO, Rathmell JC, et al:

Pharmacological blockade of ASCT2-dependent glutamine transport

leads to antitumor efficacy in preclinical models. Nat Med.

24:194–202. 2018. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Muthusamy T, Cordes T, Handzlik MK, You L,

Lim EW, Gengatharan J, Pinto AFM, Badur MG, Kolar MJ, Wallace M, et

al: Serine restriction alters sphingolipid diversity to constrain

tumour growth. Nature. 586:790–795. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gao X, Sanderson SM, Dai Z, Reid MA,

Cooper DE, Lu M, Richie JP Jr, Ciccarella A, Calcagnotto A, Mikhael

PG, et al: Dietary methionine influences therapy in mouse cancer

models and alters human metabolism. Nature. 572:397–401. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Mossmann D, Müller C, Park S, Ryback B,

Colombi M, Ritter N, Weißenberger D, Dazert E, Coto-Llerena M,

Nuciforo S, et al: Arginine reprograms metabolism in liver cancer

via RBM39. Cell. 186:5068–5083.e23. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Krall AS, Mullen PJ, Surjono F, Momcilovic

M, Schmid EW, Halbrook CJ, Thambundit A, Mittelman SD, Lyssiotis

CA, Shackelford DB, et al: Asparagine couples mitochondrial

respiration to ATF4 activity and tumor growth. Cell Metab.

33:1013–1026.e6. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Missiaen R, Anderson NM, Kim LC, Nance B,

Burrows M, Skuli N, Carens M, Riscal R, Steensels A, Li F and Simon

MC: GCN2 inhibition sensitizes arginine-deprived hepatocellular

carcinoma cells to senolytic treatment. Cell Metab.

34:1151–1167.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC,

DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, Sagalovskiy IR, Ma A, Kapilian J,

Firl CEM, et al: Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor

ferroptosis in mice. Science. 368:85–89. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Xue Y, Lu F, Chang Z, Li J, Gao Y, Zhou J,

Luo Y, Lai Y, Cao S, Li X, et al: Intermittent dietary methionine

deprivation facilitates tumoral ferroptosis and synergizes with

checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun. 14:47582023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zheng J and Conrad M: The metabolic

underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 32:920–937. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang W, Li Q, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Yuan S,

Zhang X, Zhao M, Zhuang W and Li B: Multiple myeloma with high

expression of SLC7A11 is sensitive to erastin-induced ferroptosis.

Apoptosis. 29:412–423. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Koppula P, Zhuang L and Gan B: Cystine

transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: Ferroptosis, nutrient

dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 12:599–620. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R,

Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS

and Stockwell BR: Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate

exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis.

Elife. 3:e025232014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gounder M, Johnson M, Heist RS, Shapiro

GI, Postel-Vinay S, Wilson FH, Garralda E, Wulf G, Almon C, Nabhan

S, et al: MAT2A inhibitor AG-270/S095033 in patients with advanced

malignancies: A phase I trial. Nat Commun. 16:4232025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cacciatore A, Shinde D, Musumeci C,

Sandrini G, Guarrera L, Albino D, Civenni G, Storelli E, Mosole S,

Federici E, et al: Epigenome-wide impact of MAT2A sustains the

androgen-indifferent state and confers synthetic vulnerability in

ERG fusion-positive prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 15:66722024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hou PP, Zheng CM, Wu SH, Liu XX, Xiang GX,

Cai WY, Chen G and Lou YL: Extracellular vesicle-packaged ACSL4

induces hepatocyte senescence to promote hepatocellular carcinoma

progression. Cancer Res. 84:3953–3966. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius

E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A,

et al: ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular

lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 13:91–98. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chaneton B, Hillmann P, Zheng L, Martin

ACL, Maddocks ODK, Chokkathukalam A, Coyle JE, Jankevics A, Holding

FP, Vousden KH, et al: Serine is a natural ligand and allosteric

activator of pyruvate kinase M2. Nature. 491:458–462. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Cunningham A, Erdem A, Alshamleh I,

Geugien M, Pruis M, Pereira-Martins DA, van den Heuvel FAJ,

Wierenga ATJ, Ten Berge H, Dennebos R, et al: Dietary methionine

starvation impairs acute myeloid leukemia progression. Blood.

140:2037–2052. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang QL, Chen Z, Lu X, Lin H, Feng H, Weng

N, Chen L, Liu M, Long L, Huang L, et al: Methionine metabolism

dictates PCSK9 expression and antitumor potency of PD-1 blockade in

MSS colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e25016232025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hong XL, Huang CK, Qian H, Ding CH, Liu F,

Hong HY, Liu SQ, Wu SH, Zhang X and Xie WF: Positive feedback

between arginine methylation of YAP and methionine transporter

SLC43A2 drives anticancer drug resistance. Nat Commun. 16:872025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang X, Zhao Z, Wang X, Zhang S, Zhao Z,

Feng W, Xu L, Nie J, Li H, Liu J, et al: Deprivation of methionine

inhibits osteosarcoma growth and metastasis via C1orf112-mediated

regulation of mitochondrial functions. Cell Death Dis. 15:3492024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Huang Z, Chen P and Liu Y: RBM15-mediated

the m6A modification of MAT2A promotes osteosarcoma cell

proliferation, metastasis and suppresses ferroptosis. Mol Cell

Biochem. 480:2923–2933. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Xia S, Liang Y, Shen Y, Zhong W and Ma Y:

MAT2A inhibits the ferroptosis in osteosarcoma progression

regulated by miR-26b-5p. J Bone Oncol. 41:1004902023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Yang S, Gu X, Chen L and Zhu W: Discovery

of novel spirocyclic MAT2A inhibitors demonstrating high in vivo

efficacy in MTAP-Null xenograft models. J Med Chem. 68:3480–3494.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhou Y, Wang L, Ren R, Zhang J, Huan X,

Yang P, Miao ZH, Xiong B, Wang Y and Liu T: Structure-based

discovery of a series of novel MAT2a inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett.

16:646–650. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wang Y, Hu M, Cao J, Wang F, Han JR, Wu

TW, Li L, Yu J, Fan Y, Xie G, et al: ACSL4 and polyunsaturated

lipids support metastatic extravasation and colonization. Cell.

188:412–429.e27. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Shafqat N, Muniz JR, Pilka ES,

Papagrigoriou E, von Delft F, Oppermann U and Yue WW: Insight into

S-adenosylmethionine biosynthesis from the crystal structures of

the human methionine adenosyltransferase catalytic and regulatory

subunits. Biochem J. 452:27–36. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

LeGros HL Jr, Halim AB, Geller AM and Kotb

M: Cloning, expression, and functional characterization of the beta

regulatory subunit of human methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT

II). J Biol Chem. 275:2359–2366. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

LeGros L, Halim AB, Chamberlin ME, Geller

A and Kotb M: Regulation of the human MAT2B gene encoding the

regulatory beta subunit of methionine adenosyltransferase, MAT II.

J Biol Chem. 276:24918–24924. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Li Z, Wang F, Liang B, Su Y, Sun S, Xia S,

Shao J, Zhang Z, Hong M, Zhang F and Zheng S: Methionine metabolism

in chronic liver diseases: An update on molecular mechanism and

therapeutic implication. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:2802020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Villa E, Sahu U, O'Hara BP, Ali ES, Helmin

KA, Asara JM, Gao P, Singer BD and Ben-Sahra I: mTORC1 stimulates

cell growth through SAM synthesis and m6A mRNA-dependent

control of protein synthesis. Mol Cell. 81:2076–2093.e9. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Gu X, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Condon KJ, Liu

GY, Krawczyk PA, Scaria SM, Harper JW, Gygi SP and Sabatini DM:

SAMTOR is an S-adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway.

Science. 358:813–818. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ibrahim A, Yucel N, Kim B and Arany Z:

Local mitochondrial ATP production regulates endothelial fatty acid

uptake and transport. Cell Metab. 32:309–319.e7. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Milger K, Herrmann T, Becker C, Gotthardt

D, Zickwolf J, Ehehalt R, Watkins PA, Stremmel W and Füllekrug J:

Cellular uptake of fatty acids driven by the ER-localized acyl-CoA

synthetase FATP4. J Cell Sci. 119:4678–4688. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Huang B, Nie G, Dai X, Cui T, Pu W and

Zhang C: Environmentally relevant levels of Cd and Mo coexposure

induces ferroptosis and excess ferritinophagy through AMPK/mTOR

axis in duck myocardium. Environ Toxicol. 39:4196–4206. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ouyang Y, Wu Q, Li J and Sun S and Sun S:

S-adenosylmethionine: A metabolite critical to the regulation of

autophagy. Cell Prolif. 53:e128912020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Fernández-Ramos D, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Lu SC

and Mato JM: S-adenosylmethionine: A multifaceted regulator in

cancer pathogenesis and therapy. Cancers (Basel). 17:5352025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|