Introduction

Sarcomas are uncommon malignancies, accounting for

approximately 1% of adult cancers and 15% of pediatric cancers

(1). Sarcomas are not only

uncommon, but also vary in their locations, features, and subtypes;

there are more than 100 distinct soft tissue sarcoma (STS) subtypes

that have been classified so far (2,3). Due

to these complexities, STS presents significant diagnostic

challenges and the prognosis remains poor despite advancements in

treatment like radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Between 2000 and

2018, the 5-year survival rate for STS with distant metastasis was

only 16.7% (4). Therefore, it is

essential to explore novel therapeutic approaches for treatment of

STS patients.

Recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of

DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways in both cancer development and

treatment (5–8). DDR contributes to the maintenance of

genomic stability by repairing DNA damage, and its dysfunction can

lead to oncogenesis, ultimately promoting the development of cancer

(5). Moreover, therapies such as

chemotherapy and radiotherapy induce DNA damage to eliminate cancer

cells, with tumors harboring mutations in DNA repair genes often

displaying increased sensitivity to such treatments due to their

reduced DNA repair efficiency (6).

SAMHD1 and p-ATM are key regulators of the DDR pathway (9–12).

Their roles in DNA repair and their potential as therapeutic

targets in cancer warrant further investigation.

SAMHD1 is primarily known for its role as a

deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase (dNTPase),

preventing abnormal DNA re-synthesis during the DNA end-joining

process (10). When SAMHD1 function

is impaired, this process is disrupted, leading to genomic

instability, which ultimately contributes to cancer development

(11). One cancer type associated

with this mechanism is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (11). Research on the impact of SAMHD1

expression on cancer prognosis is ongoing across various cancers

(13–16). In colorectal cancer, patients with

decreased SAMHD1 expression have been shown to have a poor

prognosis, which is hypothesized to be due to the dNTPase activity,

which inhibits tumor cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis

(13). Conversely, a recent study

in breast cancer reported that tumors expressing SAMHD1 exhibited

shorter progression-free and overall survival following

chemotherapy (14). This study

suggested that SAMHD1 depletion reduced interleukin signaling,

potentially altering immune cell infiltration (14).

ATM is essential for the repair of DNA double-strand

breaks, regulating cell cycle checkpoints, and triggering apoptosis

(9,17). Upon DNA damage, ATM is recruited to

the site of damage and is activated through autophosphorylation,

forming p-ATM, which subsequently preserves genomic integrity by

regulating various cellular processes (18). ATM has long been recognized as a key

tumor suppressor in the context of tumorigenesis (19,20).

However, several studies have revealed that ATM signaling

paradoxically supports tumor progression in certain biological

settings, indicating a more complex and context-dependent role in

cancer development. Several studies have provided evidence

supporting the oncogenic role of ATM in cancer progression, as

outlined below. In melanoma patients, both high expression and loss

of p-ATM have been identified as markers of poor survival (21). This is likely because overactivation

of p-ATM-related signaling pathways also promotes tumorigenesis,

while the loss of p-ATM undermines genome maintenance, leading to

cancer progression (21,22). In pancreatic cancer, decreased p-ATM

expression has been linked not only to poor prognosis but also to

the upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes such as BCL-2/BAD,

contributing to gemcitabine resistance (17).

Several studies have demonstrated that the DDR

activity of SAMHD1 is dependent on ATM-mediated signaling, either

through direct phosphorylation or indirect modulation of its

stability and recruitment (23–25).

Conversely, loss of SAMHD1 has been associated with aberrant ATM

pathway activation, leading to increased genomic instability and

tumorigenesis (26). Collectively,

these findings suggest a functional interplay between SAMHD1 and

p-ATM, particularly in the context of genome integrity under

replicative stress or genotoxic insult (23–26).

Despite increasing interest in the role of DDR

components in cancer biology, the clinical significance of SAMHD1

and p-ATM expression in STS remains poorly characterized. To date,

no comprehensive studies have evaluated the prognostic or

pathological implications of SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression

specifically in STS. Given their pivotal roles in genome

maintenance and the emerging evidence of their functional

interaction in the DDR network, investigating the expression

patterns of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS might provide valuable insights

into tumor behavior and patient outcomes. Therefore, in this study,

we evaluated the expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS tissues and

assessed their associations with clinicopathological parameters and

patient prognosis.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

This study received approval from the Institutional

Review Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB number:

2024-04-026-001) and was conducted in compliance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written informed

consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of

the study and the use of anonymized data.

Patients and samples

A total of 133 patients with STS were included in

this study. The patient selection was based on the following

inclusion criteria: i) Patients histopathologically diagnosed with

STS; ii) patients who underwent surgical resection at Jeonbuk

National University Hospital between January 2000 and November

2022; iii) availability of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE)

tissue blocks suitable for tissue microarray (TMA) construction;

and iv) availability of complete clinicopathological and follow-up

data from medical records. The exclusion criteria were: i) Cases

with insufficient or poor-quality tissue material for TMA analysis;

and ii) patients with incomplete clinical data or those lost to

follow-up.

Histological types of STS included in this study are

listed in Table I.

Clinicopathologic information was obtained by reviewing medical

records. Factors included sex, age, site, T category, lymph node

metastasis, M category, histologic grade, tumor differentiation,

mitotic count, and tumor necrosis. Histologic slides were reviewed

according to the WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and

bone tumor (27) and graded using

the FNCLCC (French Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre

le Cancer) grading system (28). T

category and M category were classified with reference to the 8th

edition of the American Joint Committee Cancer Staging System

(29).

| Table I.Expression status of SAMHD1 and p-ATM

according to the histological type of soft tissue sarcoma. |

Table I.

Expression status of SAMHD1 and p-ATM

according to the histological type of soft tissue sarcoma.

|

|

| SAMHD1

expression | p-ATM

expression |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Histological

type | No. | Positive, n

(%) | P-value | Positive, n

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| Leiomyosarcoma | 23 | 16 (69.6) | 0.011 | 12 (52.2) | 0.368 |

| Synovial

sarcoma | 20 | 9 (45.0) | >0.999 | 12 (60.0) | 0.143 |

| Undifferentiated

sarcoma | 15 | 10 (66.7) | 0.096 | 10 (66.7) | 0.095 |

| Myxoid

liposarcoma | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 0.144 | 1 (7.7) | 0.007 |

|

Myxofibrosarcoma | 8 | 3 (37.5) | >0.999 | 0 (0.0) | 0.010 |

| Well-differentiated

liposarcoma | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 0.300 | 2 (25.0) | 0.465 |

| Angiosarcoma | 7 | 3 (42.9) | >0.999 | 5 (71.4) | 0.239 |

| Malignant

peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 0.088 | 3 (50.0) | >0.999 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 0.693 | 3 (50.0) | >0.999 |

| Adult

fibrosarcoma | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 0.693 | 3 (50.0) | >0.999 |

| Low-grade

myofibroblastic sarcoma | 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0.066 | 0 (0.0) | 0.068 |

| Alveolar

rhabdomyosarcoma | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 0.322 | 3 (75.0) | 0.317 |

| Dedifferentiated

liposarcoma | 3 | 1 (33.3) | >0.999 | 1 (33.3) | >0.999 |

| Embryonal

rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0.503 | 0 (0.0) | 0.504 |

| Pleomorphic

rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0.503 | 1 (50.0) | >0.999 |

| Epithelioid

sarcoma | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0.503 | 1 (50.0) | >0.999 |

| Pleomorphic

liposarcoma | 1 | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Spindle cell

rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma | 1 | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 | 1 (100.0) | 0.436 |

Immunohistochemical staining and

scoring

We constructed a TMA using paraffin-embedded tissue

blocks obtained from surgical specimens of 133 STS patients. Two

cores, each 3.0 mm in size, were collected from non-necrotic,

non-degenerative areas of tumors. TMA tissue sections were

deparaffinized, followed by antigen retrieval performed in pH 6.0

antigen retrieval solution (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) using a

microwave oven for 20 min. Primary antibodies for SAMHD1 (1:50,

PA5-21515, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and p-ATM (1:50, sc-47739,

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were incubated with the

TMA tissue section overnight at 4°C.

Two pathologists (KMK and YJK) who were blinded to

the clinicopathologic information of the patients assessed

immunohistochemical staining under a multi-view microscope (Nikon

Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) by consensus. Both SAMHD1 and

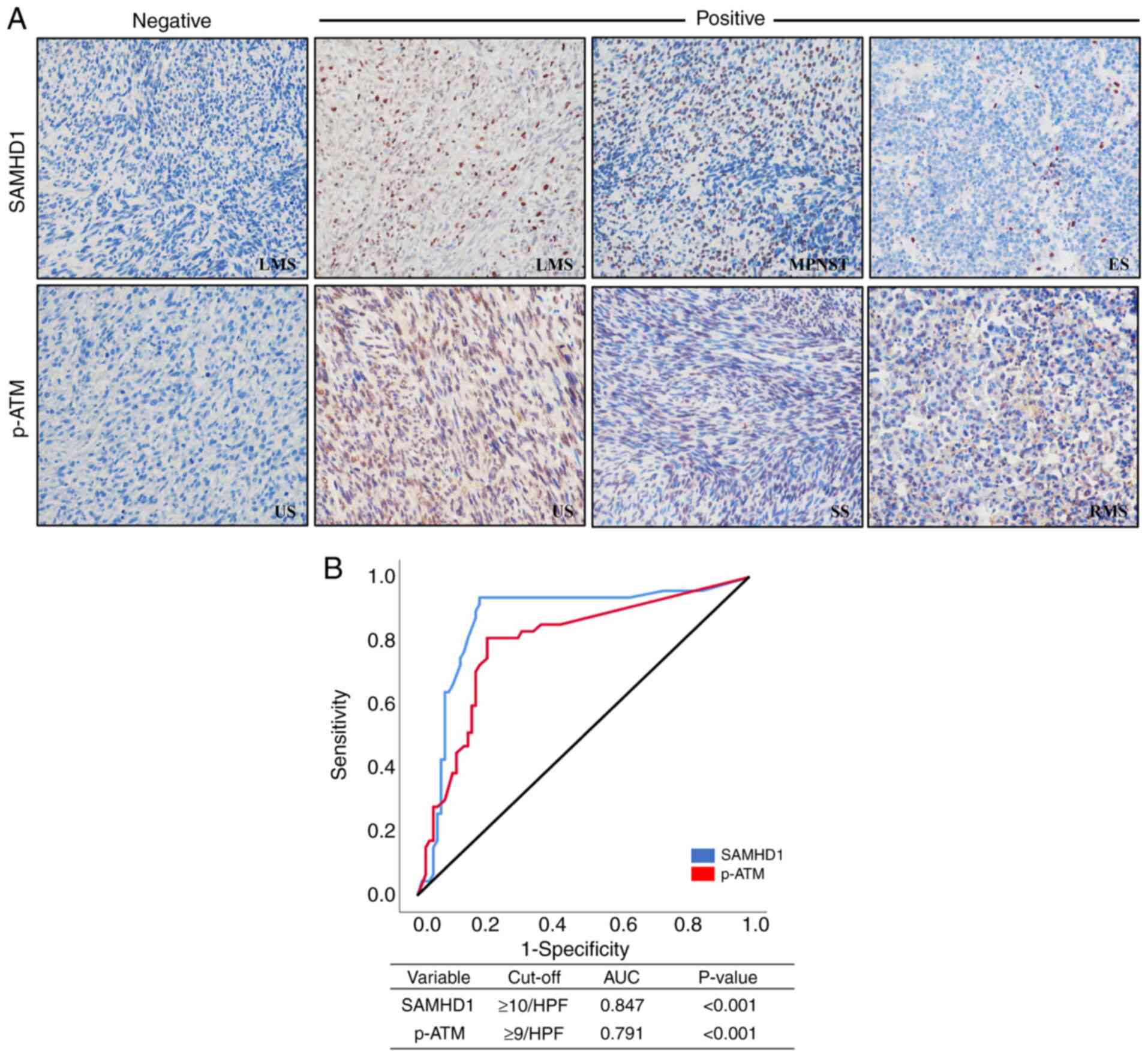

p-ATM were expressed mostly in nuclei (Fig. 1). As previous studies on the

immunohistochemical expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM have primarily

focused on nuclear staining patterns, our analysis was likewise

based on nuclear localization (13,14,17,21).

To evaluate staining, we first identified the region with the

highest density of positive cells under low magnification and then

counted positive cells per high-power field (HPF), with a maximum

of 50 cells per field. Finally, we calculated the average by

summing the counts from each TMA section. The diameter of HPF was

625 µm. and the area of one HPF was 306,796 µm2.

| Figure 1.(A) Immunohistochemistry of SAMHD1

and p-ATM in various STSs (original magnification, ×400). (B)

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to determine

cut-off points for the levels of nuclear SAMHD1 (blue line) and

nuclear p-ATM (red line). The cut-off points indicate the point of

the highest AUC to predict the death of patients with STS. AUC,

area under the curve; ES, Ewing sarcoma; HPF, high-power field;

LMS, leiomyosarcoma; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumor; p-ATM, phosphorylated ataxia-telangiectasia mutated; RMS,

rhabdomyosarcoma; SAMHD1, SAM domain and HD domain-containing

protein 1; SS, synovial sarcoma; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; US,

undifferentiated sarcoma. |

Statistical analysis

Patients were categorized into positive and negative

subgroups based on the immunohistochemical expression levels of

SAMHD1 and p-ATM. Cutoff values for both markers to identify the

threshold with the highest prognostic accuracy for predicting

patient death were established through receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The end date of follow-up was

either the date of patient death or the last contact date by

December 2022. Prognostic outcomes were evaluated by calculating

overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). In the

OS analysis, death specifically due to STS was considered an event,

while cases where patients were alive at their last follow-up or

died from other causes were censored. In the PFS analysis, relapse

and metastasis of STS and death due to STS were treated as events.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (IBM,

version 26.0, Armonk, NY). To evaluate differences in SAMHD1 and

p-ATM expression among histological subtypes, Fisher's exact test

was performed for pairwise comparisons between each subtype and the

remainder of the cohort. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with the

log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions between

groups. For pairwise comparisons between subgroups, P-values were

obtained using the log-rank test and adjusted for multiple testing

using Bonferroni's correction. Cox proportional hazards regression

was used to evaluate the prognosis of STS. Stepwise selection was

employed to include variables independently associated with

survival in the multivariate Cox model. Pearson's chi-square test

assessed the associations between immunohistochemical expression

and clinicopathological factors, while the correlation between

SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression was determined using Pearson's and

Spearman's correlation tests. P-values less than 0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS

tissues

Fig. 1 shows the

immunohistochemical staining patterns of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS

tissue samples; both these markers exhibited predominantly nuclear

expression (Fig. 1A). ROC curve

analysis, using patient death as a determinant, was employed to

segregate individuals into SAMHD1- and p-ATM-positive and negative

groups. Optimal cutoff values were defined as 10/HPF for SAMHD1 and

9/HPF for p-ATM (Fig. 1B).

Positivity rates of SAMHD1 and p-ATM across various histologic

types of STS are summarized in Table

I.

Correlation between SAMHD1 and p-ATM

expression

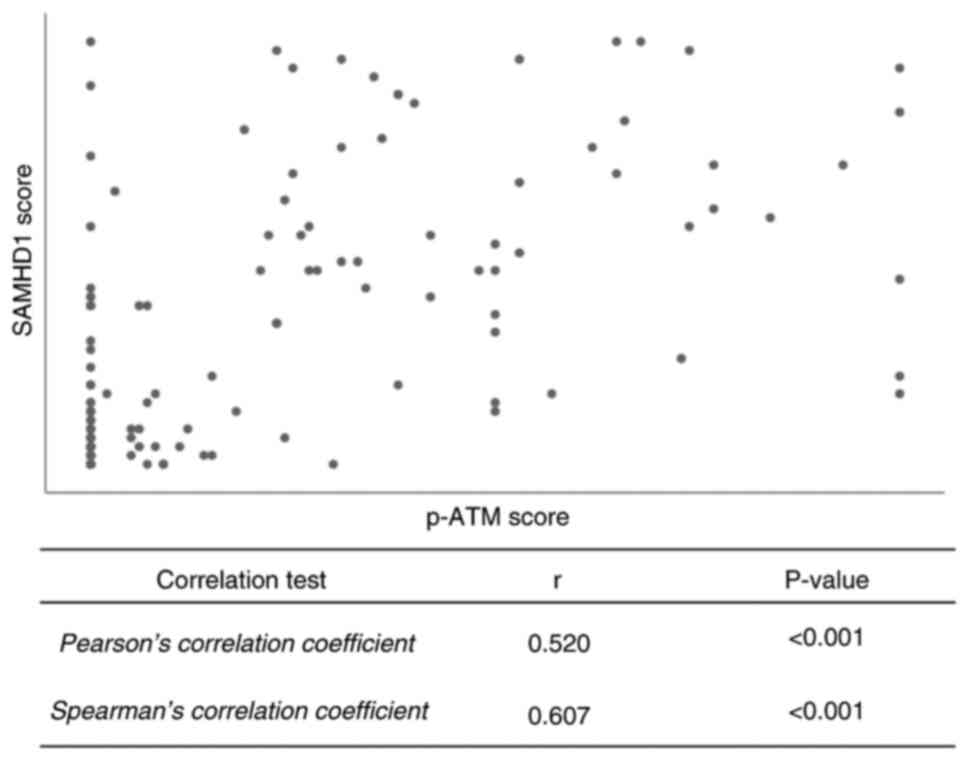

Based on previous reports indicating a functional

interaction between SAMHD1 and p-ATM in the DDR pathway, we

analyzed a relationship between their immunohistochemical

expression. Chi-square tests revealed a significant correlation

between SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression when comparing positive and

negative expression groups (P<0.001) (Table II). Furthermore, Pearson's

correlation analysis showed a moderate correlation (r=0.520,

P<0.001), and Spearman's correlation revealed a stronger

association (r=0.607, P<0.001) between the immunohistochemical

staining scores of SAMHD1 and p-ATM (Fig. 2).

| Table II.Association between SAMHD1 and p-ATM

levels. |

Table II.

Association between SAMHD1 and p-ATM

levels.

|

| SAMHD1

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| p-ATM

expression | Positive, n

(%) | Negative, n

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| Positive | 47 (82.5) | 10 (17.5) |

|

| Negative | 13 (17.1) | 63 (82.9) | <0.001 |

Associations of individual and

combined patterns of SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression with

clinicopathological factors

Individual SAMHD1 positivity was associated with

higher histologic grade (P=0.018) (Table III). p-ATM positivity showed

strong correlations with T category (P=0.005) and histologic grade

(P=0.001) (Table III).

| Table III.Clinicopathologic variables and

levels of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in soft tissue sarcoma. |

Table III.

Clinicopathologic variables and

levels of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in soft tissue sarcoma.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Combined

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

| SAMHD1

expression |

| p-ATM

expression |

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+, n

(%) |

SAMHD1+/p-ATM− or

SAMHD−/p-ATM+, n (%) |

SAMHD1−/p-ATM−, n

(%) | P-value |

|---|

|

Characteristics | Total, n | Positive, n

(%) | Negative, n

(%) | P-value | Positive, n

(%) | Negative, n

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| All cases | 133 | 59 (44.4) | 74 (55.6) |

| 57 (42.9) | 76 (57.1) |

| 42 (31.6) | 32 (24.1) | 59 (44.4) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 74 | 32 (43.2) | 42 (56.8) |

| 28 (37.8) | 46 (62.2) |

| 22 (29.7) | 16 (21.6) | 36 (48.6) |

|

|

Female | 59 | 27 (45.8) | 32 (54.2) | 0.771 | 29 (49.2) | 30 (50.8) | 0.190 | 20 (33.9) | 16 (27.1) | 23 (39.0) | 0.526 |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤60 | 76 | 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) |

| 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) |

| 25 (32.9) | 18 (23.7) | 33 (43.4) |

|

|

>60 | 57 | 25 (43.9) | 32 (56.1) | 0.920 | 23 (40.4) | 34 (59.6) | 0.613 | 17 (29.8) | 14 (24.6) | 26 (45.6) | 0.931 |

| Site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Head

and neck | 9 | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) |

| 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| 3 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) |

|

| Trunk

and extremities | 105 | 44 (41.9) | 61 (58.1) |

| 43 (41.0) | 62 (59.0) |

| 32 (30.5) | 23 (21.9) | 50 (47.6) |

|

| Abdomen

and thoracic visceral organs | 15 | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) |

| 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) |

| 7 (46.7) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) |

|

|

Retroperitoneum | 4 | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0.274a | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0.585a | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0.321a |

| T category |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T 1,

2 | 94 | 39 (41.5) | 55 (58.5) |

| 33 (35.1) | 61 (64.9) |

| 25 (26.6) | 22 (23.4) | 47 (50.0) |

|

| T 3,

4 | 39 | 20 (51.3) | 19 (48.7) | 0.301 | 24 (61.5) | 15 (38.5) | 0.005 | 17 (43.6) | 10 (25.6) | 12 (30.8) | 0.087 |

| LN metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Absent | 120 | 52 (43.3) | 68 (56.7) |

| 48 (40.0) | 72 (60.0) |

| 38 (31.7) | 27 (22.5) | 55 (45.8) |

|

|

Present | 13 | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | 0.562a | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 0.769a | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0.398a |

| M category |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| M0 | 123 | 53 (43.1) | 70 (56.9) |

| 50 (40.7) | 73 (59.3) |

| 37 (30.1) | 29 (23.6) | 57 (46.3) |

|

| M1 | 10 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.338a | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.098a | 5 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.251a |

| Histologic

grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grade

1 | 31 | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.2) |

| 5 (16.1) | 26 (83.9) |

| 4 (12.9) | 5 (16.1) | 22 (71.0) |

|

| Grade 2

and 3 | 102 | 51 (50.0) | 51 (50.0) | 0.018 | 50 (49.0) | 52 (51.0) | 0.001 | 38 (37.3) | 27 (26.5) | 37 (36.3) | 0.003 |

| Tumor

differentiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) |

| 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.3) |

| 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | 7 (43.8) |

|

| 2 and

3 | 117 | 51 (43.6) | 66 (56.4) | 0.789a | 50 (42.7) | 67 (57.3) |

>0.999a | 36 (30.8) | 29 (24.8) | 52 (44.4) | 0.812a |

| Mitotic count |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0-9/10

HPF | 62 | 27 (43.5) | 35 (56.5) |

| 24 (38.7) | 38 (61.3) |

| 17 (27.4) | 17 (27.4) | 28 (45.2) |

|

| ≥10/10

HPF | 71 | 32 (45.1) | 39 (54.9) | 0.860 | 33 (46.5) | 38 (53.5) | 0.366 | 25 (35.2) | 15 (21.1) | 31 (43.7) | 0.549 |

| Tumor necrosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Absent | 71 | 28 (39.4) | 43 (60.6) |

| 25 (35.2) | 46 (64.8) |

| 17 (23.9) | 19 (26.8) | 35 (49.3) |

|

|

Present | 62 | 31 (50.0) | 31 (50.0) | 0.221 | 32 (51.6) | 30 (48.4) | 0.057 | 25 (40.3) | 13 (21.0) | 24 (38.7) | 0.128 |

Additionally, we reclassified patients into three

sub-groups based on SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression levels:

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+, SAMHD1+/p-ATM- or SAMHD1-/p-ATM+, and

SAMHD1-/p-ATM-. Co-expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM was significantly

associated with histologic grade (P=0.003) (Table III).

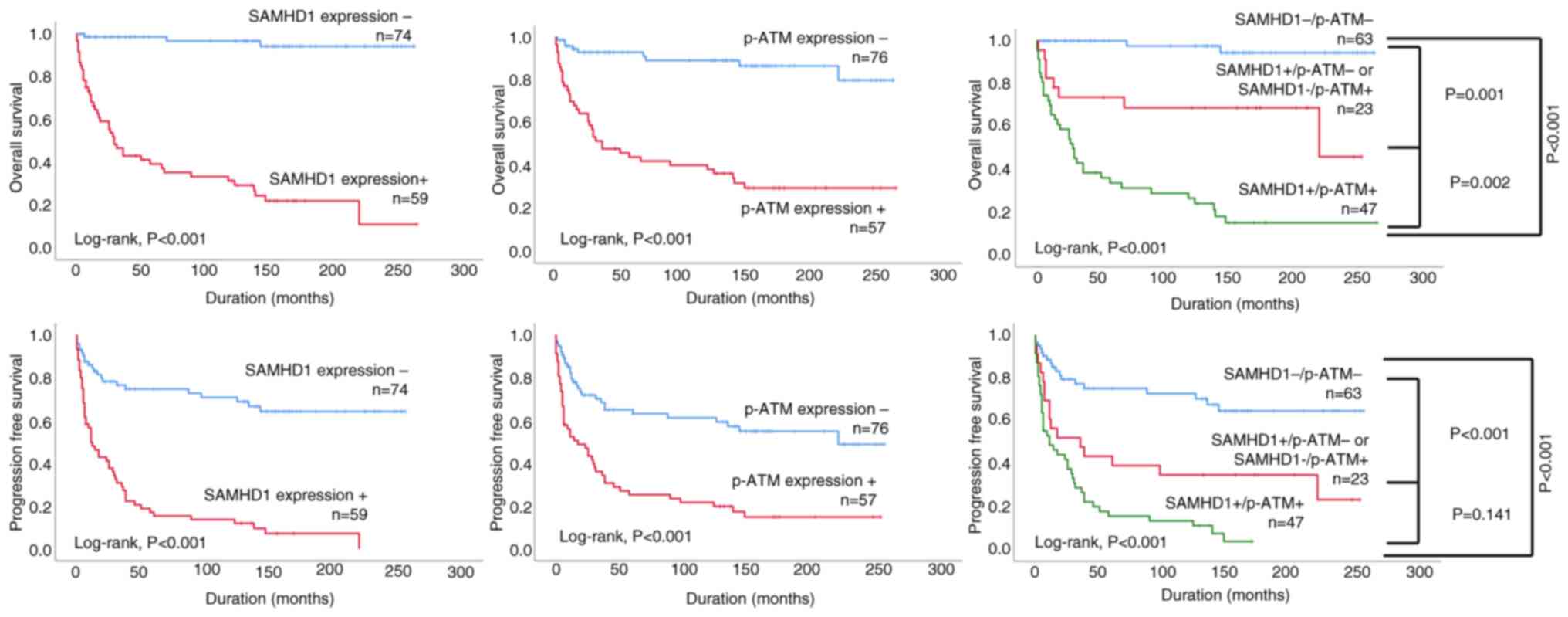

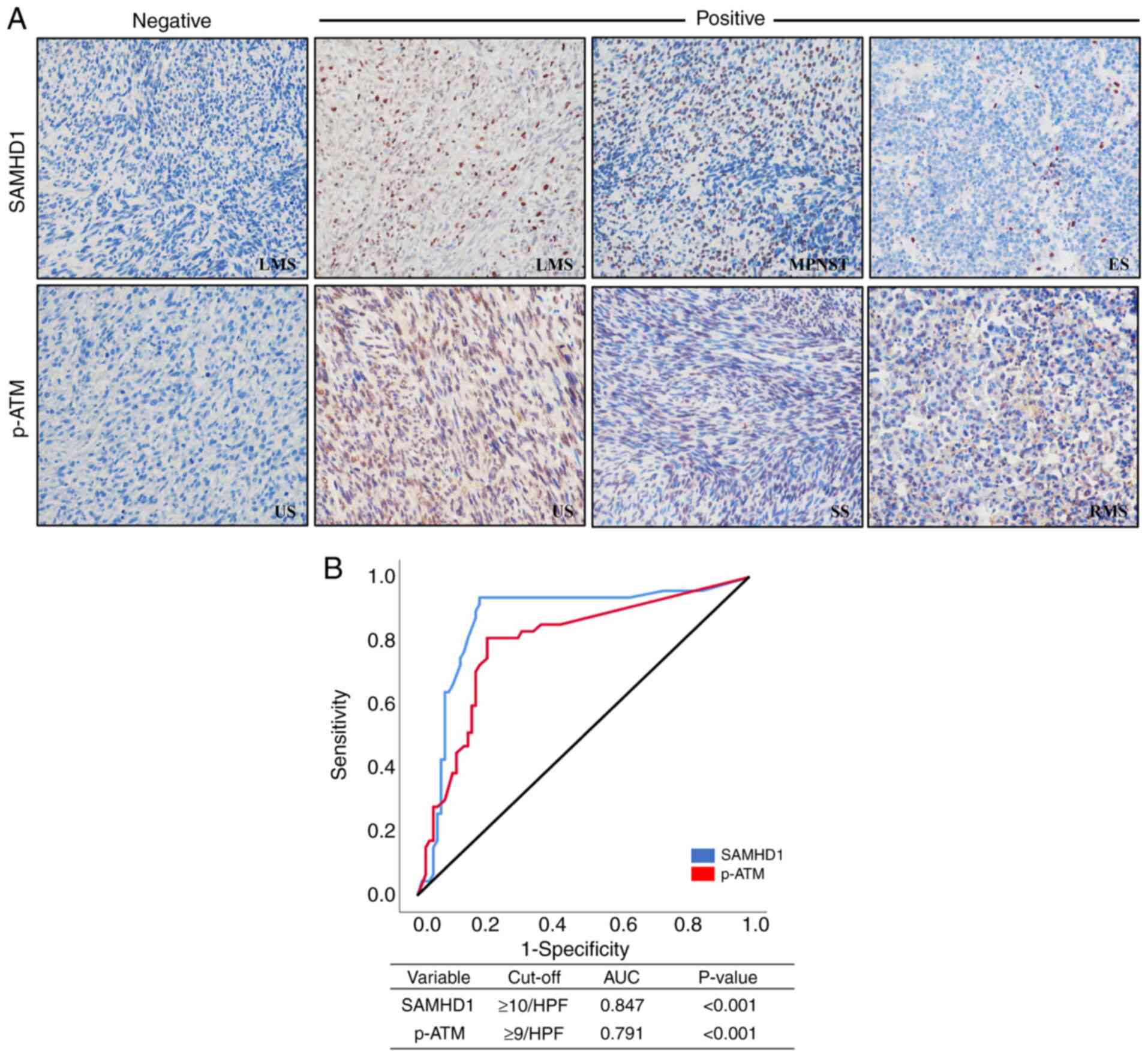

Univariate and Kaplan-Meier survival

analyses of individual and combined expression patterns of SAMHD1

and p-ATM for OS and PFS of STS patients

Analysis of various clinical parameters using

univariate methods showed significant correlations between several

factors and patient outcomes. Specifically, T category (P=0.005), M

category (P=0.038) and histologic grade (P=0.013) were

significantly associated with poor OS, along with SAMHD1 expression

(P<0.001), p-ATM expression (P<0.001), and co-expression

pattern of SAMHD1 and p-ATM (P<0.001) (Table IV). In univariate analysis of PFS,

age (P=0.016), M category (P<0.001) and histologic grade

(P=0.007) were significantly associated with shorter PFS. SAMHD1

(P<0.001), p-ATM (P=0.001), and co-expression of SAMHD1 and

p-ATM (P<0.001) also showed correlations with shorter PFS in the

univariate analysis (Table

IV).

| Table IV.Univariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis of OS and PFS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma. |

Table IV.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis of OS and PFS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma.

|

| OS | PFS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, male (vs.

female) | 0.831

(0.468–1.474) | 0.527 | 0.997

(0.636–1.565) | 0.990 |

| Age, >60 years

(vs. ≤60 years) | 1.141

(0.639–2.037) | 0.656 | 1.742

(1.109–2.736) | 0.016 |

| T category 3, 4

(vs. T1, 2) | 2.3

(1.288–4.107) | 0.005 | 1.514

(0.943–2.431) | 0.086 |

| LN metastasis,

present (vs. absent) | 1.425

(0.638–3.182) | 0.388 | 0.819

(0.394–1.705) | 0.594 |

| M category M1 (vs.

M0) | 2.481

(1.051–5.853) | 0.038 | 7.623

(3.823–15.200) | <0.001 |

| Histologic grade 2

and 3 (vs. grade 1) | 3.237

(1.279–8.910) | 0.013 | 2.344

(1.261–4.357) | 0.007 |

| Mitotic count

≥10/10 HPF (vs. 0–9/10 HPF) | 1.064

(0.599–1.888) | 0.833 | 1.046

(0.669–1.636) | 0.844 |

| Tumor

differentiation 2 and 3 (vs. 1) | 1.280

(0.506–3.239) | 0.602 | 0.961

(0.494–1.869) | 0.907 |

| Tumor necrosis

present (vs. absent) | 1.267

(0.714–2.247) | 0.419 | 1.059

(0.677–1.657) | 0.802 |

| SAMHD1, positive

(vs. negative) | 7.583

(3.536–16.262) | <0.001 | 4.621

(2.805–7.614) | <0.001 |

| p-ATM, positive

(vs. negative) | 7.65

(3.688–15.870) | <0.001 | 2.939

(1.853–4.661) | <0.001 |

| Combined expression

of SAMHD1/p-ATM |

|

|

|

|

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM−

or SAMHD1−/p-ATM+ | 7.179

(2.001–25.753) | 0.002 | 3.694

(1.926–7.085) | <0.001 |

| (vs.

SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) |

|

|

|

|

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+

(vs. SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) | 22.774

(6.950–74.624) | <0.001 | 6.213

(3.387–11.398) | <0.001 |

Patients with positive SAMHD1 expression faced a

7.583-fold higher risk of death [95% confidential interval (CI)

3.536–16.262, P< 0.001)], as well as a 4.621-fold greater risk

of disease progression or mortality (95% CI; 2.805–7.614,

P<0.001). Patients positive for p-ATM expression exhibited a

7.65-fold (95% CI; 3.688–15.87, P<0.001) elevated risk of death

and a 2.939-fold higher risk of disease progression or mortality

(95% CI; 1.853–4.661, P<0.001) compared to those with negative

expression (Table IV). Regarding

the co-expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM, STS patients who were

SAMHD1+/p-ATM- or SAMHD1-/p-ATM+ had a 7.179-fold (95% CI;

2.001–25.753) and a 3.694-fold (95% CI; 1.926–7.085) increased risk

of death and progression or death, respectively, compared to STS

patients with the SAMHD1-/p-ATM-expression pattern. STS patients

with the SAMHD1+/p-ATM+ expression pattern exhibited even higher

risks, with a 22.774-fold (95% CI; 6.95–74.624) and a 6.213-fold

(95% CI; 3.387–11.398) increased likelihood of death and relapse or

death, respectively, compared to STS patients with the

SAMHD1-/p-ATM-expression pattern (Table IV). Kaplan-Meier survival curves

for OS and PFS based on individual and co-expression patterns of

SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS patients are presented in Fig. 3.

Multivariate survival analysis of

individual and combined expression patterns of SAMHD1 and p-ATM for

OS and PFS of STS patients

To investigate the impact of individual and combined

expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM on OS and PFS in STS patients, we

performed multivariate survival analyses. Expression patterns were

independently analyzed using two models: Model 1 for individual

expression and Model 2 for co-expression. Each model included the

expression pattern along with other clinicopathological variables

that were statistically significant for OS or PFS in the univariate

analysis. Independent prognostic indicators for OS were SAMHD1

expression, and p-ATM (Table V,

model 1). STS patients with positive SAMHD1 expression had a

4.178-fold higher risk of mortality than those with negative SAMHD1

expression (95% CI; 1.828–9.548, P=0.002) (Table V, model 1). Furthermore, STS

patients with positive p-ATM expression had a 3.420-fold higher

risk of mortality than those with negative p-ATM expression (95%

CI; 1.518–7.704, P=0.003) (Table V,

model 1). Age, M category, and SAMHD1 expression were significant

independent factors associated with PFS in the multivariate

analysis (Table VI, model 1). The

SAMHD1-positive group had a 3.617-fold increased risk of

progression or death (95% CI: 2.154–6.074, <0.001) compared to

the SAMHD1-negative group (Table

VI, model 1).

| Table V.Multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis for OS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma. |

Table V.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis for OS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma.

|

| OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Model

1a |

|

|

| SAMHD1,

positive (vs. negative) | 4.178

(1.828–9.548) | 0.002 |

| p-ATM,

positive (vs. negative) | 3.420

(1.518–7.704) | 0.003 |

| Model

2b |

|

|

|

Combined expression of

SAMHD1/p-ATM |

|

|

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM−

or SAMHD1−/p-ATM+ (vs.

SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) | 6.588

(1.834–23.670) | 0.004 |

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+

(vs. SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) | 18.915

(5.710–62.654) | <0.001 |

| Table VI.Multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis for PFS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma. |

Table VI.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression analysis for PFS in patients with soft tissue

sarcoma.

|

| PFS |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Model

1a |

|

|

| Age,

>60 years (vs. ≤60 years) | 2.038

(1.254–3.313) | 0.004 |

| M

category M1 (vs. M0) | 5.426

(2.575–11.434) | <0.001 |

| SAMHD1,

positive (vs. negative) | 3.617

(2.154–6.074) | <0.001 |

| Model

2b |

|

|

| Age,

>60 years (vs. ≤60 years) | 2.180

(1.345–3.534) | 0.002 |

| M

category M1 (vs. M0) | 6.024

(2.863–12.675) | <0.001 |

| Combined expression

of SAMHD1/p-ATM |

|

|

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM−

or SAMHD1−/p-ATM+ (vs.

SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) | 3.749

(1.943–7.233) | <0.001 |

|

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+

(vs. SAMHD1−/p-ATM−) | 5.159

(2.773–9.597) | <0.001 |

Only combined SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression was an

independent predictor of OS of STS patients (Table V, model 2). STS patients with the

SAMHD1+/p-ATM-expression pattern or SAMHD1-/p-ATM+ expression

pattern had a 6.588-fold (95% CI; 1.834–23.670, P=0.004) increased

risk of death compared to SAMHD1-/p-ATM-cases, while SAMHD1+/p-ATM+

cases showed a 18.915-fold (95% CI; 5.710–62.654, P<0.001)

higher risk of death (Table V,

model 2). Age, M category and combined expression of SAMHD1 and

p-ATM were independent prognostic factors of PFS in STS patients

(Table VI, model 2). STS patients

with the SAMHD1+/p-ATM- or SAMHD1-/p-ATM+ expression pattern

demonstrated a 3.749-fold (95% CI; 1.943–7.233, P<0.001) greater

risk of death or progression, whereas SAMHD1+/p-ATM+ cases had a

5.159-fold (95% CI; 2.773–9.597, P<0.001) increased risk of

death or progression compared to STS patient with the

SAMHD1-/p-ATM-expression pattern (Table VI, model 2).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the immunohistochemical

expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS tissues and investigated

their associations with clinicopathological features and patient

outcomes. Although previous studies have investigated the

associations between SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression and prognosis in

various cancers (23–25), their prognostic significance in STS

has not been explored. To our knowledge, this is the first study to

evaluate the prognostic impact of SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression

specifically in STS. In the present study, both SAMHD1 and p-ATM

exhibited predominant nuclear localization based on

immunohistochemical staining. We found that both the individual and

combined expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM were significantly

associated with higher histologic grade and adverse survival

outcomes in STS patients. Multivariate analysis revealed that both

the individual and combined expression of SAMHD1 and p-ATM

independently served as prognostic factors for OS. Additionally,

SAMHD1 expression and the co-expression pattern of SAMHD1 and p-ATM

were independent prognostic factors for PFS. Furthermore, SAMHD1

and p-ATM expression were highly correlated.

SAMHD1, by facilitating DNA end resection at

double-strand breaks, plays important roles in DDR and homologous

recombination (24). Loss or

dysfunction of SAMHD1 can lead to the accumulation of genomic

instability and has been associated with tumorigenesis in several

malignancies (30,31). To date, several studies have

investigated the impact of SAMHD1 expression on cancer progression

across various tumor types, with conflicting results reported

depending on the specific cancer type (13–16).

In contrast to our findings, decreased SAMHD1 expression has been

associated with a poor prognosis in colorectal cancer and diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma (13,32). However, numerous studies have

reported results consistent with ours. For instance, SAMHD1

expression was associated with shorter time-to-progression and OS

in early breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (14). Additionally,

SAMHD1 acted as a poor prognostic marker in classical Hodgkin

lymphoma (33), aligning with our

findings. Taken together, these divergent findings suggest that the

prognostic role of SAMHD1 varies depending on tumor type,

potentially reflecting cancer-specific differences in biological

function and interaction with the tumor microenvironment.

ATM is activated through autophosphorylation in

response to DNA double-strand breaks, initiating checkpoint

signaling and repair pathways (34). ATM is well recognized for its role

as a tumor suppressor (20).

Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) is an inherited autosomal recessive

disorder resulting from germline mutations in the ATM gene

(20,35). Patients with A-T commonly present

with neurological and systemic abnormalities, including ataxia of

the cerebellum, telangiectasias affecting the skin and eyes, immune

dysfunction, and impaired gonadal development (35). In addition to these features,

individuals with A-T face a markedly elevated lifetime cancer risk,

with approximately 38.2% developing malignancies by the age of 40

(35,36). Although ATM is widely recognized as

a tumor suppressor, as previously mentioned, accumulating research

suggests that the underlying signaling pathway can, in certain

biological contexts, contribute to the advancement of cancer

(37). In melanoma, high p-ATM

expression was linked to lower 5-year survival and a more

aggressive phenotype (21) and was

associated with poor locoregional disease-free survival and shorter

disease-specific survival in cervical cancer (38), consistent with our findings.

Importantly, our study is among the first to assess

the co-expression patterns of SAMHD1 and p-ATM in STS. A

moderate-to-strong positive correlation between their expression

was observed, supporting previous reports suggesting functional

crosstalk between these proteins (19,24,39).

SAMHD1 activity has been shown to be modulated by ATM-dependent

phosphorylation, and SAMHD1 deficiency can lead to dysregulated ATM

signaling and genomic instability (39). The strong prognostic value of the

SAMHD1+/p-ATM+ co-expression pattern observed in our study further

supports the biological interdependence of these DDR components and

suggests that their combined assessment enhances prognostic

stratification in STS patients. Considering the findings of the

present study, we propose that the DDR plays a critical role in the

progression of STS.

STSs can be broadly categorized into two genomic

subgroups: i) tumors characterized by extensive copy-number

alterations, chromosomal instability, and a high burden of

structural variants, and ii) translocation-associated tumors with

relatively simple genomes driven by pathognomonic fusion

oncoproteins (1). In the former,

which is common across adult STSs, chronic replication stress and

ongoing DNA damage are intrinsic features of tumor biology

(2,3). In tumors with chromosomal instability,

persistent DDR signaling may act as a protective mechanism by

helping to prevent catastrophic genome collapse, buffering

replication stress, and potentially supporting continued

proliferation under genotoxic pressure (4). Collectively, these activities make

SAMHD1 an attractive tumor promoter and explain why high

SAMHD1/p-ATM expression correlates with an increased grade and

poorer survival in our STS cohort. p-ATM and SAMHD1 indicate active

double-strand break signaling, checkpoint activation, end

resection, and homologous recombination at stalled forks and

breaks, thereby contributing to the maintenance of genome integrity

under stress (5,6). Collectively, these functions suggest

that SAMHD1 may act as a tumor promoter and provide a rationale for

the observed association between high SAMHD1/p-ATM expression,

increased tumor grade, and poorer survival in our STS cohort'.

As mentioned previously, discordant findings have

been reported in other malignancies, such as colorectal cancer. In

a study investigating the role of SAMHD1 in colorectal cancer,

reduced SAMHD1 expression was associated with poor prognosis. The

authors demonstrated that the dNTPase function of SAMHD1 suppresses

cell proliferation and reduces replication errors, thereby

contributing to its tumor-suppressive role. Moreover, mutations

affecting SAMHD1′s catalytic sites were shown to inhibit the

expression of apoptosis-related proteins while upregulating

anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-2, ultimately suppressing

apoptosis and promoting uncontrolled proliferation. We propose that

the apparent discrepancy with our study can be explained by the

fact that many STS arise under persistent replication stress and

pronounced structural instability, conditions in which elevated

SAMHD1, together with active ATM signaling, enhances repair

capacity and stress tolerance, thereby supporting tumor persistence

and progression (1,3). Such cancer-type differences give a

reasonable explanation for the different results between our STS

study and colorectal cancer.

DDR is fundamentally recognized as a

tumor-suppressive mechanism (40).

It is activated upon genomic insults such as DNA double-strand

breaks, single-strand breaks, or replication stress and serves to

arrest the cell cycle, initiate DNA repair, or induce apoptosis or

senescence in irreparably damaged cells (40). Through these mechanisms, DDR

prevents the accumulation of mutations and maintains genomic

stability, acting as a safeguard against malignant transformation

(40). However, accumulating

evidence suggests that DDR can also exert oncogenic effects under

certain biological contexts, giving rise to a paradox in its role

in cancer (8). In established

tumors, particularly those experiencing high replication stress,

DDR activity can support cancer cell survival by managing chronic

DNA damage (8). Consequently, an

intact DDR pathway can contribute to tumor progression and be

associated with poor patient prognosis (8). In light of this, the association

between SAMHD1 and p-ATM expression and poor prognosis supports the

possibility that an intact or upregulated DDR pathway contributes

to tumor progression in STS.

From a clinical standpoint, the identification of

SAMHD1 and p-ATM as independent prognostic markers has important

implications. These molecules could potentially be incorporated

into histopathological assessment to help stratify patients at

higher risk, informing decisions regarding closer monitoring or

individualized therapeutic strategies. In parallel, there has been

increasing interest in targeting components of the DDR as a novel

therapeutic avenue in oncology (7).

Although PARP inhibitors have demonstrated clinical benefit in

tumors harboring homologous recombination deficiencies, the

therapeutic relevance of modulating SAMHD1 or ATM activity in this

context remains to be fully elucidated (26). Further research is warranted to

explore whether inhibition of SAMHD1 or ATM could enhance the

therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in STS.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective

design and the use of tissue microarrays limit the generalizability

of our findings. Moreover, the synergistic correlation between

SAMHD1 and p-ATM in the current study depends on

immunohistochemical and clinical evidence, and there is no

functional evidence directly supporting it. Further in vitro and in

vivo experiments, such as co-knockdown or overexpression studies,

are warranted to explore the underlying biological mechanism of the

interaction between them and the effects on tumor cell

proliferation, apoptosis, and DNA repair ability. In addition, the

relatively small cohort size and the critical underrepresentation

of certain histological subtypes may limit the statistical power of

our analyses and compromise the generalizability of

subtype-specific conclusions. Larger, multi-institutional studies

are required to validate and extend our findings.

In conclusion, we investigated the expression of

SAMHD1 and p-ATM in patients with STS and found that their

expression is significantly associated with aggressive tumor

characteristics and poor clinical outcomes. Their individual and

combined expression patterns were independent prognostic factors

for OS and PFS. These findings provide new insights into the

molecular pathology of STS and suggest that DDR components such as

SAMHD1 and p-ATM can serve as valuable prognostic biomarkers and

potential therapeutic targets in this challenging-to-treat

malignancy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Fund of Biomedical

Research Institute, Jeonbuk National University Hospital, a grant

from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea

Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of

Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HR22C1832), and

the National Institute of Health (NIH) research project (project

no. 2024-ER0511-01).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YJK and KMK conceived and designed the study, and

performed the experiments. YJM contributed to the acquisition of

clinical samples, participated in pathological review and assisted

in the interpretation of clinical data. KYJ, ARA, MJC and WSM

analyzed the data. YJM, ARA, MJC and KYJ were involved in

statistical analysis, data visualization and interpretation of the

results. YJK and KMK drafted the manuscript. ARA, HSP, MJC and WSM

verified the authenticity of all the raw data, assisted in data

curation and validation, contributed to the interpretation of the

findings, and critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted in accordance with The

Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (approval no.

2024-04-026-001; Jeonju, South Korea). The requirement for consent

for participation was waived due to the retrospective nature of the

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

von Mehren M, Kane JM, Bui MM, Choy E,

Connelly M, Dry S, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, et

al: NCCN guidelines insights: soft tissue sarcoma, version 1.2021.

J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 18:1604–1612. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ressing M, Wardelmann E, Hohenberger P,

Jakob J, Kasper B, Emrich K, Eberle A, Blettner M and Zeissig SR:

Strengthening health data on a rare and heterogeneous disease:

Sarcoma incidence and histological subtypes in Germany. BMC Public

Health. 18:2352018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Nacev BA, Sanchez-Vega F, Smith SA,

Antonescu CR, Rosenbaum E, Shi H, Tang C, Socci ND, Rana S,

Gularte-Mérida R, et al: Clinical sequencing of soft tissue and

bone sarcomas delineates diverse genomic landscapes and potential

therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 13:34052022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rutland CS: Advances in soft tissue and

bone sarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 16:28752024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Khanna KK and Jackson SP: DNA

double-strand breaks: Signaling, repair and the cancer connection.

Nat Genet. 27:247–254. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Moon J, Kitty I, Renata K, Qin S, Zhao F

and Kim W: DNA damage and its role in cancer therapeutics. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:47412023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Drew Y, Zenke FT and Curtin NJ: DNA damage

response inhibitors in cancer therapy: Lessons from the past,

current status and future implications. Nat Rev Drug Discov.

24:19–39. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Park SH, Noh SJ, Kim KM, Bae JS, Kwon KS,

Jung SH, Kim JR, Lee H, Chung MJ, Moon WS, et al: Expression of DNA

damage response molecules PARP1, γH2AX, BRCA1, and BRCA2 predicts

poor survival of breast carcinoma patients. Trans Oncol. 8:239–249.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ueno S, Sudo T and Hirasawa A: ATM:

Functions of ATM kinase and its relevance to hereditary tumors. Int

J Mol Sci. 23:5232022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Akimova E, Gassner FJ, Schubert M,

Rebhandl S, Arzt C, Rauscher S, Tober V, Zaborsky N, Greil R and

Geiberger R: SAMHD1 restrains aberrant nucleotide insertions at

repair junctions generated by DNA end joining. Nucleic Acids Res.

49:2598–2608. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Schott K, Majer C, Bulashevska A, Childs

L, Schmidt MHH, Rajalingam Munder M and König R: SAMHD1 in cancer:

Curse or cure? J Mol Med (Berl). 100:351–372. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Li Y, Gao Y, Jiang X, Cheng Y, Zhang J, Xu

L, Liu X, Huang Z, Xie C and Gong Y: SAMHD1 silencing cooperates

with radiotherapy to enhance anti-tumor immunity through

IFI16-STING pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med.

20:6282022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang Z, Li P and Sun P: Expression of

SAMHD1 and its mutation on prognosis of colon cancer. Oncol Lett.

24:3032022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gutiérrez-Chamorro L, Felip E, Castellà E,

Quiroga V, Ezeonwumelu IJ, Angelats L, Esteve A, Rerez-Roca L,

Martínez-Cardús A, Fernandez PL, et al: SAMHD1 expression is a

surrogate marker of immune infiltration and determines prognosis

after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 47:189–208. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kim KM, Moon YJ, Park SH, Park HJ, Wang

SI, Park HS, Lee H, Kwon KS, Moon WS, Lee DG, et al: Individual and

combined expression of DNA damage response molecules PARP1, γH2AX,

BRCA1, and BRCA2 predict shorter survival of soft tissue sarcoma

patients. PLoS One. 11:e01631932016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Jiang H, Li C, Liu Z, Hospital S and Hu R:

Expression and relationship of SAMHD1 with other apoptotic and

autophagic genes in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Acta Haematol.

143:51–59. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xun J, Ohtsuka H, Hirose K, Douchi D,

Nakayama S, Ishida M, Miura T, Ariake K, Mizuma M, Nakagawa K, et

al: Reduced expression of phosphorylated ataxia-telangiectasia

mutated gene is related to poor prognosis and gemcitabine

chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 23:8352023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Stucci LS, Internò V, Tucci M, Perrone M,

Mannavola F, Palmirotta R and Porta C: The ATM gene in breast

cancer: Its relevance in clinical practice. Genes (Basel).

12:7272021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Schumann T, Ramon SC, Schubert N, Mayo MA,

Hega M, Maser KI, Ada SR, Sydow L, Hajikazemi M, Badstübner M, et

al: Deficiency for SAMHD1 activates MDA5 in a cGAS/STING-dependent

manner. J Exp Med. 220:e202208292023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Rotman

G, Ziv Y, Vanagaite L, Tagle DA, Smith S, Uziel T, Sfez S, et al: A

single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3

kinase. Science. 268:1749–1753. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bhandaru M, Martinka M, McElwee KJ and

Rotte A: Prognostic significance of nuclear phospho-ATM expression

in melanoma. PLoS One. 10:e01346782015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Stagni V, Oropallo V, Fianco G, Antonelli

M, Cinà I and Barilà D: Tug of war between survival and death:

Exploring ATM function in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 15:5388–5409.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Coquel F, Silva MJ, Técher H, Zadorozhny

K, Sharma S, Nieminuszczy J, Mettling C, Dardillac E, Barthe A,

Schmitz AL, et al: SAMHD1 acts at stalled replication forks to

prevent interferon induction. Nature. 557:57–61. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Daddacha W, Koyen AE, Bastien AJ, Head PE,

Dhere VR, Nabeta GN, Connolly EC, Werner E, Madden MZ, Daly MB, et

al: SAMHD1 promotes DNA end resection to facilitate DNA repair by

homologous recombination. Cell Rep. 20:1921–1935. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kapoor-Vazirani P, Rath SK, Liu X, Shu Z,

Bowen NE, Chen Y, Haji-Seyed-Javadi R, Daddacha W, Minten EV,

Danelia D, et al: SAMHD1 deacetylation by SIRT1 promotes DNA end

resection by facilitating DNA binding at double-strand breaks. Nat

Commun. 13:67072022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Rodríguez-Sánchez A, Quijada-Álamo M,

Pérez-Carretero C, Herrero AB, Arroyo-Barea A, Dávila-Valls J,

Rubio A, de Coca AG, Benito-Sánchez R, Rodríguez-Vicente AE, et al:

SAMHD1 dysfunction impairs DNA damage response and increases

sensitivity to PARP inhibition in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci

Rep. 15:104462025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

World Health Organization (WHO), . Soft

tissue and bone tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial.

5th Edition. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2020

|

|

28

|

Coindre J: Histologic grading of adult

soft tissue sarcomas. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 82:59–63. 1998.

|

|

29

|

Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK,

Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC and Jessup JM:

AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Amin MB, Edge SB and Greene FL: Eighth

Edition. Springer; New York, USA: pp. 251–274. 2017

|

|

30

|

Clifford R, Louis T, Robbe P, Ackroyd S,

Burns A, Timbs AT, Colopy GW, Dreau H, Sigaux F, Judde JG, et al:

SAMHD1 is mutated recurrently in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and

is involved in response to DNA damage. Blood. 123:1021–1031. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Chen Z, Hu J, Ying S and Xu A: Dual roles

of SAMHD1 in tumor development and chemoresistance to anticancer

drugs. Oncol Lett. 21:4512021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Daddacha W, Monroe D, Schlafstein AJ,

Withers AE, Thompson EB, Danelia D, Luong NC, Sesay F, Rath SK,

Usoro ER, et al: SAMHD1 expression contributes to doxorubicin

resistance and predicts survival outcomes in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma patients. NAR Cancer. 6:zcae0072024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xagoraris I, Vassilakopoulos TP, Drakos E,

Angelopoulou MK, Panitsas F, Herold N, Medeiros LJ, Giakoumis X,

Pangalis GA and Rassidakis GZ: Expression of the novel tumour

suppressor sterile alpha motif and HD domain-containing protein 1

is an independent adverse prognostic factor in classical Hodgkin

lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 193:488–496. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Bakkenist CJ and Kastan MB: DNA damage

activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer

dissociation. Nature. 421:499–506. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Rothblum-Oviatt C, Wright J, Lefton-Greif

MA, McGrath-Morrow SA, Crawford TO and Lederman HM: Ataxia

telangiectasia: A review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 11:1592016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Suarez F, Mahlaoui N, Canioni D,

Andriamanga C, d'Enghien CD, Brousse N, Jais JP, Fischer A, Hermine

O and Stoppa-Lyonnet D: Incidence, presentation, and prognosis of

malignancies in ataxia-telangiectasia: A report from the French

national registry of primary immune deficiencies. J Clin Oncol.

33:202–208. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Lee JH: Targeting the ATM pathway in

cancer: Opportunities, challenges and personalized therapeutic

strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 129:1028082024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Roossink F, Wieringa HW, Noordhuis MG, ten

Hoor KA, Kok M, Slagter-Menkema L, Hollema H, de Bock GH, Pras E,

de Vries EGE, et al: The role of ATM and 53BP1 as predictive

markers in cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 131:2056–2066. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Maunakea AK, Chepelev I, Cui K and Zhao K:

Intragenic DNA methylation modulates alternative splicing by

recruiting MeCP2 to promote exon recognition. Cell Res.

23:1256–1269. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ciccia A and Elledge SJ: The DNA damage

response: Making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 40:179–204.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|