Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading

cause of cancer-associated mortality, with an incidence of ~0.8

million cases in 2022, worldwide (1,2).

Although, surgical resection, transplantation and local ablation

are the standard treatment approaches for patients with early-stage

HCC, nearly half of patients are diagnosed with advanced-stage

disease at initial presentation (3). Systemic therapy is recommended for

patients with advanced HCC, among which sorafenib is the standard

first-line treatment for over a decade (3,4).

However, recent advances in tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have

reshaped the therapeutic landscape of advanced HCC, and its

combination with immunotherapy may improve the prognosis of these

patients (4,5).

Apatinib is an oral TKI that inhibits tumor

angiogenesis, and has shown promising efficacy when combined with

programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors in patients with

advanced HCC (6–8). For example, a previous study reported

an objective response rate (ORR) of 50.0% and a disease control

rate (DCR) of 91.3% in patients with advanced HCC treated with

apatinib combined with a PD-1 inhibitor (7). Additionally, in another study,

patients with advanced HCC who received apatinib plus PD-1

inhibitor showed a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.7

months and a median overall survival (OS) of 22.5 months (8). Therefore, apatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor

has become a promising treatment strategy for advanced HCC.

Camrelizumab, a high-affinity immunoglobulin G4k

monoclonal antibody of PD-1, has demonstrated promising efficacy in

treating patients with advanced HCC (9,10).

Previously, several clinical trials have suggested that these

patients can benefit from camrelizumab combined with apatinib

(11,12). For example, the RESCUE trial

reported an ORR of 34.3%, and a 12-month OS rate of 74.7% in

patients with advanced HCC who were treated with camrelizumab plus

apatinib as first-line therapy. Additionally, an ORR of 22.5% and a

12-month OS rate of 68.2% was reported in patients who received

this regimen as a second-line treatment (11). Additionally, the CARES-310 trial

revealed that camrelizumab combined with apatinib as first-line

therapy for patients with advanced HCC could result in an ORR of

25.4%, a DCR of 78.3%, a median PFS of 5.6 months and a median OS

of 23.8 months (12). However,

real-world evidence on camrelizumab plus apatinib in patients with

advanced HCC is limited, and therefore further validation is

needed. Furthermore, prognostic factors affecting treatment

outcomes have not been fully elucidated.

Therefore, the present real-world study aimed to

evaluate the efficacy and safety of camrelizumab plus apatinib in

patients with advanced HCC, as well as to identify potential

prognostic factors associated with treatment outcome in these

patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present retrospective, single-arm study aimed to

evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of camrelizumab combined

with apatinib in patients with advanced HCC. The inclusion criteria

were as follows: i) Patients diagnosed with advanced HCC, which was

defined as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C (13); ii) age >18 years; iii) treated

with camrelizumab plus apatinib; iv) available complete treatment

response data based on imaging examinations; v) complete follow-up

data, including disease status and survival data; vi) no history of

organ transplantation; and vii) no history of autoimmune disease

requiring systemic therapy. The exclusion criteria were the

following: i) Patients suffering from liver malignancies other than

HCC, such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic liver

cancer; ii) patients diagnosed with hematological malignancies or

other primary cancers; iii) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

performance status (ECOG PS) of >2; and iv) uncontrolled or

severe comorbidities, such as heart failure and chronic renal

failure. Patients were enrolled from the Handan Central Hospital

between March 2020 and January 2024. The study protocol was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Handan Central

Hospital (approval no. 2024029). Written informed consent was

obtained from all patients or their family members.

Data collection

All data were extracted from electronic medical

records and included demographic characteristics, treatment

history, such as surgery or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE),

ECOG PS, disease-related information, treatment details, treatment

response data and follow-up outcomes. Treatment lines were counted

based on systematic therapy only, while prior locoregional

therapies (such as TACE) did not affect the line-counting of

systematic treatments. Treatment response was assessed every 3

months using computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance

imaging. The imaging findings were reviewed centrally and

categorized according to the response evaluation criteria in solid

tumors criteria (14). The

follow-up data included the timing and occurrence of disease

progression and death. PFS and OS rates were estimated based on

follow-up data. PFS was defined as the time from treatment

initiation to the first disease progression or all-cause mortality.

OS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to mortality

from any cause. The median follow-up duration was 10.0 months

(range, 1.0–54.0 months). Finally, the adverse events were recorded

by clinicians and screened by investigators based on the Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (available at

http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5×7.pdf).

Treatment information

Patients received camrelizumab at a dose of 200 mg

intravenously for 3 weeks, combined with apatinib at a dose of 250

mg taken orally once daily. In addition, several patients underwent

TACE according to their own willingness, disease status and

physician recommendation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version 26.0; IBM Corp.). Post hoc statistical power

analysis using PASS software (version 15.0.5; NCSS LLC) was

performed. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the

results. PFS and OS in patients with advanced HCC were calculated

using Kaplan-Meier curves. The Log-rank test was used to compare

Kaplan-Meier curves between subgroups. Univariate and multivariate

Cox regression analyses were carried out to identify prognostic

factors associated with PFS and OS. All variables in the univariate

analysis were incorporated into the multivariate model using the

enter method. A Fisher's exact test was used to compare ORR and DCR

between subgroups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical features

The mean age of the 39 patients included in the

present study was 59.4±11.4 years. A total of 8 women (20.5%) and

31 men (79.5%) were enrolled. Among all patients, 13 (33.3%)

presented with portal vein invasion and 17 (43.6%) with

extrahepatic metastasis. A total of 29 patients (74.4%) received

camrelizumab + apatinib as first-line therapy, while 10 patients

(25.6%) were treated with this regimen as second- or later-line

therapy. The detailed patient characteristics are listed in

Table I.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of patients

with advanced HCC. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with advanced HCC.

| Characteristic | Patients with

advanced HCC (n=39) |

|---|

| Age (mean ± SD),

years | 59.4±11.4 |

| Sex |

|

|

Female | 8 (20.5) |

| Male | 31 (79.5) |

| HBV history | 27 (69.2) |

| Liver cirrhosis

history | 23 (59.0) |

| A history of surgery

or TACE | 18 (46.2) |

| ECOG PS |

|

| 1 | 38 (97.4) |

| 2 | 1 (2.6) |

| Maximum tumor

diameter (median IQR), cm | 5.0 (4.0–9.3) |

| Maximum tumor

diameter ≥10 cm | 8 (20.5) |

| Portal vein

invasion | 13 (33.3) |

| Extrahepatic

metastasis | 17 (43.6) |

| ALB (median IQR),

g/l | 68.6 (57.1–72.2) |

| Abnormal ALB | 28 (71.8) |

| TBIL (median IQR),

µmol/l | 16.4 (13.8–38.3) |

| Abnormal TBIL | 23 (59.0) |

| ALT (median IQR),

U/l | 36.0 (26.0–51.0) |

| Abnormal ALT | 26 (66.7) |

| AST (median IQR),

U/l | 63.0

(34.0–114.0) |

| Abnormal AST | 12 (30.8) |

| AFP (median IQR),

ng/ml | 24.2

(3.9–1210.0) |

| AFP ≥200 ng/ml | 14 (35.9) |

| Number of TACEs |

|

| 0 | 29 (74.4) |

| 1 | 8 (20.5) |

| 2 | 2 (5.1) |

| Treatment line of

systematic therapy |

|

|

First-line | 29 (74.4) |

| Second

or later | 10 (25.6) |

Treatment response

Among all patients, 10 (25.6%) achieved a complete

response, 4 (10.3%) reached partial response, 18 (46.2%) had stable

disease and 7 (17.9%) exhibited progressive disease. The ORR and

DCR were 35.9 and 82.1%, respectively (Table II).

| Table II.Treatment response of patients with

advanced HCC. |

Table II.

Treatment response of patients with

advanced HCC.

| Outcome | Patients with

advanced HCC (n=39) |

|---|

| Response |

|

| CR | 10 (25.6) |

| PR | 4 (10.3) |

| SD | 18 (46.2) |

| PD | 7 (17.9) |

| ORR | 14 (35.9) |

| DCR | 32 (82.1) |

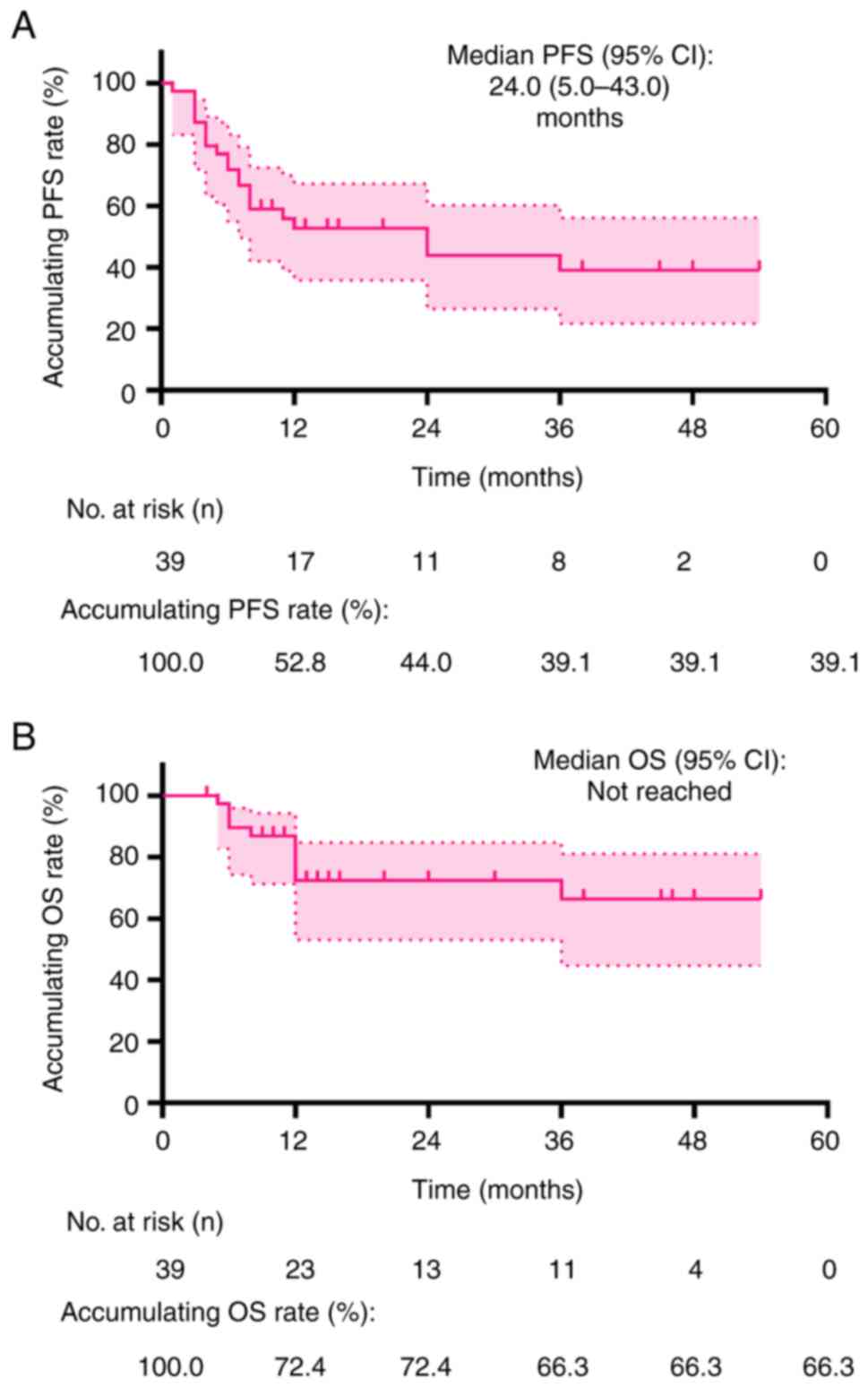

PFS and OS

The median PFS was 24.0 months [95% confidence

interval (CI): 5.0–43.0 months]. The accumulated PFS rates at 12,

24 and 36 months were 52.8, 44.0 and 39.1%, respectively (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the median OS was

not reached during the follow-up period. The cumulative OS rates at

12, 24 and 36 months were 72.4, 72.4 and 66.3%, respectively

(Fig. 1B).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was performed based on use of

TACE or not and demonstrated that the ORR, DCR, PFS and OS were

similar between patients with and without TACE (all P>0.05;

Table SI).

Factors affecting PFS and OS

Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that

abnormal aspartate aminotransferase levels (yes vs. no) were

associated with higher risk of disease progression or mortality

[hazard ratio (HR), 2.461; P=0.044]. However, in multivariate Cox

regression analysis, none of the evaluated clinical characteristics

were associated with PFS (all P>0.05; Table III). Furthermore, regarding OS,

univariate Cox regression analysis revealed no associations between

OS and clinical features (all P>0.05). By contrast, multivariate

Cox regression analysis identified that extrahepatic metastasis

(yes vs. no) was independently associated with higher mortality

risk (HR, 9.217; P=0.049; Table

IV).

| Table III.Cox regression analyses on PFS in

patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table III.

Cox regression analyses on PFS in

patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

| 95% CI |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factors | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Age (>60 years

vs. ≤60 years) | 0.074 | 0.398 | 0.145 | 1.093 | 0.170 | 0.415 | 0.119 | 1.456 |

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.650 | 1.290 | 0.429 | 3.878 | 0.579 | 0.667 | 0.160 | 2.790 |

| HBV history (yes

vs. no) | 0.629 | 1.264 | 0.489 | 3.270 | 0.475 | 2.294 | 0.235 | 22.419 |

| Liver cirrhosis

history (yes vs. no) | 0.518 | 1.339 | 0.552 | 3.249 | 0.877 | 1.179 | 0.148 | 9.377 |

| A history of

surgery or TACE (yes vs. no) | 0.453 | 1.390 | 0.589 | 3.282 | 0.942 | 0.953 | 0.258 | 3.515 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter (≥10 cm vs. <10 cm) | 0.841 | 0.894 | 0.300 | 2.670 | 0.700 | 1.364 | 0.282 | 6.601 |

| Portal vein

invasion (yes vs. no) | 0.549 | 1.310 | 0.541 | 3.170 | 0.098 | 0.329 | 0.088 | 1.229 |

| Extrahepatic

metastasis (yes vs. no) | 0.430 | 1.414 | 0.599 | 3.338 | 0.157 | 2.646 | 0.688 | 10.181 |

| Abnormal ALB (yes

vs. no) | 0.658 | 1.240 | 0.478 | 3.218 | 0.533 | 0.613 | 0.132 | 2.852 |

| Abnormal TBIL (yes

vs. no) | 0.333 | 1.570 | 0.631 | 3.908 | 0.842 | 0.876 | 0.237 | 3.235 |

| Abnormal ALT (yes

vs. no) | 0.342 | 1.585 | 0.613 | 4.096 | 0.388 | 1.856 | 0.456 | 7.551 |

| Abnormal AST (yes

vs. no) | 0.044 | 2.461 | 1.024 | 5.913 | 0.111 | 3.762 | 0.738 | 19.184 |

| AFP (≥200 ng/ml vs.

<200 ng/ml) | 0.391 | 0.660 | 0.256 | 1.704 | 0.113 | 0.315 | 0.075 | 1.317 |

| Treatment line of

systematic therapy (second or later vs. first) | 0.547 | 1.338 | 0.518 | 3.460 | 0.237 | 2.043 | 0.625 | 6.679 |

| Table IV.Cox regression analyses on OS in

patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table IV.

Cox regression analyses on OS in

patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

| 95% CI |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factors | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Age (>60 years

vs. ≤60 years) | 0.364 | 0.533 | 0.137 | 2.076 | 0.816 | 0.774 | 0.090 | 6.696 |

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.407 | 2.404 | 0.302 | 19.109 | 0.986 | 1.024 | 0.078 | 13.524 |

| HBV history (yes

vs. no) | 0.740 | 0.805 | 0.225 | 2.885 | 0.427 | 3.856 | 0.138 | 107.513 |

| Liver cirrhosis

history (yes vs. no) | 0.855 | 0.890 | 0.254 | 3.120 | 0.491 | 0.347 | 0.017 | 7.053 |

| A history of

surgery or TACE (yes vs. no) | 0.464 | 1.598 | 0.455 | 5.611 | 0.914 | 0.882 | 0.091 | 8.525 |

| Maximum tumor

diameter (≥10 cm vs. <10 cm) | 0.485 | 1.619 | 0.418 | 6.270 | 0.087 | 12.040 | 0.699 | 207.526 |

| Portal vein

invasion (yes vs. no) | 0.766 | 0.813 | 0.208 | 3.174 | 0.067 | 0.084 | 0.006 | 1.192 |

| Extrahepatic

metastasis (yes vs. no) | 0.361 | 1.788 | 0.514 | 6.224 | 0.049 | 9.217 | 1.007 | 84.329 |

| Abnormal ALB (yes

vs. no) | 0.657 | 1.362 | 0.348 | 5.340 | 0.410 | 2.512 | 0.280 | 22.509 |

| Abnormal TBIL (yes

vs. no) | 0.833 | 1.147 | 0.321 | 4.107 | 0.286 | 0.271 | 0.025 | 2.988 |

| Abnormal ALT (yes

vs. no) | 0.589 | 1.452 | 0.374 | 5.632 | 0.835 | 1.292 | 0.115 | 14.483 |

| Abnormal AST (yes

vs. no) | 0.310 | 1.942 | 0.540 | 6.990 | 0.194 | 5.234 | 0.430 | 63.667 |

| AFP (≥200 ng/ml vs.

<200 ng/ml) | 0.434 | 0.538 | 0.114 | 2.539 | 0.080 | 0.077 | 0.004 | 1.355 |

| Treatment line of

systematic therapy (second or later vs. first) | 0.255 | 2.090 | 0.588 | 7.434 | 0.054 | 10.809 | 0.957 | 122.073 |

Adverse events

Adverse events are summarized in Table V. The most common adverse events

were anemia (79.5%), thrombocytopenia (69.2%), leukopenia (64.1%)

and pain (56.4%). Other adverse events included neutropenia

(41.0%), fever (33.3%), hypertension (28.2%), decreased appetite

(23.1%), nausea and vomiting (23.1%), diarrhea (7.7%), fatigue

(7.7%) and reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation

(RCCEP; 7.7%). All adverse events were of grade 1–2. In addition,

camrelizumab treatment-related adverse events included fever

(17.9%), RCCEP (7.7%), anemia (5.1%), neutropenia (5.1%), diarrhea

(5.1%), thrombocytopenia (2.6%) and fatigue (2.6%). Treatment

modifications, including dose reduction or delay, were required for

1 patient (2.6%) due to toxicity.

| Table V.Adverse events in patients with

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table V.

Adverse events in patients with

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Adverse event | Total (n=39) | Camrelizumab

treatment-related (n=39) |

|---|

| Anemia | 31 (79.5) | 2 (5.1) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 27 (69.2) | 1 (2.6) |

| Leukopenia | 25 (64.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pain | 22 (56.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Neutropenia | 16 (41.0) | 2 (5.1) |

| Fever | 13 (33.3) | 7 (17.9) |

| Hypertension | 11 (28.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Decreased

appetite | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea and

vomiting | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (7.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Fatigue | 3 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) |

| RCCEP | 3 (7.7) | 3 (7.7) |

Discussion

Systemic therapy still remains the gold standard

treatment approach for advanced HCC, with sorafenib serving as the

standard first-line treatment for a number of years. However, in

previous years, the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and

TKIs has shown encouraging efficacy, thus emerging as a potential

treatment option for this type of cancer (4,12,15).

Camrelizumab, as a PD-1 inhibitor, might also exert its antitumor

effect by other mechanisms, such as regulating the immune

infiltration, which is demonstrated by previous studies on tumor

microenvironment-related biomarkers for predicting camrelizumab

efficacy (16,17). Besides, camrelizumab combined with

apatinib potentially exert synergistic effects. Previous studies

demonstrated that apatinib could increase PD-1 expression in

tumor-infiltrating CD4+ cells, thus improving the

efficacy of camrelizumab (18,19).

The present study reports the efficacy and safety of camrelizumab

combined with apatinib in a single center; meanwhile, our study

also reports the prognostic factors, which helps the early

recognition of prognosis to facilitate early intervention and

improve outcome in advanced HCC patients receiving camrelizumab

combined with apatinib.

Clinically, previous studies have evaluated the

efficacy of camrelizumab combined with apatinib in patients with

advanced HCC, reporting ORR of 17.3–45.7%, DCR of 57.7–78.6%,

median PFS of 5.5–5.7 months and 12-month OS rates of 68.2–76.5% in

these patients (11,12,20).

In the present study, an ORR of 35.9%, a DCR of 82.1%, a median PFS

of 24.0 months and a 12-month OS rate of 72.4% was reported for

patients with advanced HCC treated with the combination of

camrelizumab plus apatinib. The results on ORR, DCR and 12-month OS

rate were consistent with those of previous studies, while a

prolonged median PFS was reported (11,12,20).

This discrepancy could be due to differences in baseline patient

characteristics. Notably, in the present study, the proportion of

patients with extrahepatic metastasis was lower (43.6%) compared

with that reported in previous studies (64.3–75.8%) (11,12).

In addition, the proportion of patients with maximum tumor diameter

of ≥10 cm was also lower (20.5%) compared with a previous study

(40.4%) (20). Therefore, the

aforementioned findings suggest that the patients included in the

present study could suffer from a less aggressive disease compared

with the previously published studies (11,12,20).

Notably, in the present study, the complete response

rate was 25.6%, which was markedly higher compared with that

reported in the CARES-310 phase III trial (1.1%). This difference

could be attributed to the fact that in the present study, 25.6% of

patients received TACE, which was not applied in the CARES-310

phase III trial (12). Therefore,

it is hypothesized that TACE could improve the complete response of

camrelizumab plus apatinib therapy in patients with advanced HCC.

However, further studies are required to validate these

findings.

The present study also aimed to identify factors

affecting PFS and OS in patients with advanced HCC treated with

camrelizumab plus apatinib. Multivariate Cox regression analyses

demonstrated that extrahepatic metastasis was independently

associated with higher mortality risk in these patients. This

result was consistent with those reported in previous studies

(21,22). However, this index was not

associated with the mortality in the univariate Cox regression

analysis, potentially due to small sample size. No other clinical

factors were associated with PFS or OS in these patients. This

finding could be due to the sample size, which could weaken

statistical power. Furthermore, the subgroup analysis indicated

that the ORR, DCR and PFS were not different between patients with

or without TACE. We hypothesize the potential reasons might be as

follows: i) The small sample size would reduce the statistical

power; and ii) patients who received TACE in addition to

camrelizumab plus apatinib presented with heavier disease burden

such as higher proportion of patients with maximum tumor diameter

≥10 cm (40.0 vs. 13.8%), with portal vein invasion (50.0 vs.

27.6%), and Child-Pugh stage B (50.0 vs. 6.3%) compared with those

without TACE. Hence, the efficacy was not different between

patients with or without TACE.

Previous studies also reported that the most common

adverse events in patients with HCC treated with camrelizumab

combined with apatinib were anemia (20.0–55.8%), thrombocytopenia

(46.3–60.0%) and leukopenia (50.0–57.1%) (11,12,23–25).

Consistently, in the present study, anemia (79.5%),

thrombocytopenia (69.2%) and leukopenia (64.1%) were the most

frequent adverse events in patients with advanced HCC treated with

camrelizumab plus apatinib. By contrast, in the present study, the

incidence of pain was 56.4%, which was higher than that reported in

previous studies (26.8–49.2%) (11,23,25).

This could be again explained by the fact that 25.6% of patients in

the present study underwent TACE, which is commonly associated with

the development of pain (20,26).

The incidences of other adverse events, including decreased

appetite, nausea and vomiting and diarrhea, were comparable with

those observed in previous studies (10,27,28).

These results indicate that camrelizumab combined with apatinib

could be well-tolerated by patients with advanced HCC. However,

further efforts are needed to optimize tolerability. Furthermore,

in previous study, the most common adverse events following

camrelizumab monotherapy includes the reactive cutaneous capillary

endothelial proliferation (67%), proteinuria (23%), and increased

alanine aminotransferase (22%) (10). The incidence of most adverse events

were numerically far lower than the camrelizumab combined with

apatinib therapy, which implied the clinicians to pay attention to

balance the clinical efficacy benefit and the risk of adverse

events when choosing the monotherapy regimen and the combination

regimen.

The present study also has several limitations.

Firstly, the inherent drawback of the retrospective and single-arm

study design should be considered, which could induce several

biases, such as selection bias and incomplete data availability. In

addition, the lack of a control group made it difficult to draw a

solid conclusion. Therefore, a further randomized and prospective

study is needed to eliminate the selection bias in the baseline

characteristics, and a control group should be included to

explicitly evaluate the benefit of camrelizumab. Secondly, post hoc

statistical power analysis using PASS software was performed based

on the observed median PFS in the present study and a previous

study (29), and a test efficacy of

89.6% was achieved when setting the a-value at 0.05. However, the

sample size was still small which limited the statistical power.

Furthermore, due to the short follow-up period, the incidence of

endpoint events was low in the present study and the median OS was

not reached. Consequently, the median OS of patients with advanced

HCC receiving camrelizumab plus apatinib needs more investigation.

Thirdly, only patients with advanced HCC from China were enrolled,

and therefore future studies involving patients across different

geographical regions are warranted to further verify the results.

Finally, previously, in patients with HCC, adjuvant therapy

following the liver transplantation was reported to improve the

prognosis of patients with HCC (30,31).

However, this was not considered in the present study. Future

studies are needed to evaluate whether the combination of liver

transplantation with camrelizumab and apatinib would improve the

survival of patients with advanced HCC.

In conclusion, camrelizumab combined with apatinib

showed satisfactory treatment efficacy and acceptable tolerance in

patients with advanced HCC. Furthermore, extrahepatic metastasis

was independently associated with worse OS in the aforementioned

patients. These findings could provide real-world evidence

supporting the application of camrelizumab plus apatinib in

treating patients advanced HCC. However, due to the small sample

size in the present study, a further study with a larger sample

size is required.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RQ and ZY conceived and designed the study. LY and

YS collected the data. RA performed the data analysis. YH and HH

contributed to the interpretation of the data. JX analyzed data and

drafted the manuscript, while RQ and ZY provided critical

revisions. RQ and ZY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of the Handan Central Hospital (approval no. 2024029).

All patients or their families provided written informed

consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R

and Saborowski A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 400:1345–1362.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.

|

|

3

|

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal

AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J and

Finn RS: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:62021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Galle PR, Dufour JF, Peck-Radosavljevic M,

Trojan J and Vogel A: Systemic therapy of advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma. Future Oncol. 17:1237–1251. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, Beal

E, Finn RS, Gade TP, Goff L, Gupta S, Guy J, Hoang HT, et al:

Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO

guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 42:1830–1850. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tian Z, Niu X and Yao W: Efficacy and

response biomarkers of apatinib in the treatment of malignancies in

China: A review. Front Oncol. 11:7490832021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Li D, Xu L, Ji J, Bao D, Hu J, Qian Y,

Zhou Y, Chen Z, Li D, Li X, et al: Sintilimab combined with

apatinib plus capecitabine in the treatment of unresectable

hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective, open-label, single-arm,

phase II clinical study. Front Immunol. 13:9440622022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Xia WL, Zhao XH, Guo Y, Cao GS, Wu G, Fan

WJ, Yao QJ, Xu SJ, Guo CY, Hu HT and Li HL: Transarterial

chemoembolization combined with apatinib with or without PD-1

inhibitors in BCLC stage C hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter

retrospective study. Front Oncol. 12:9613942022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Song H, Liu X, Jiang L, Li F, Zhang R and

Wang P: Current status and prospects of camrelizumab, A humanized

antibody against programmed cell death receptor 1. Recent Pat

Anticancer Drug Discov. 16:312–332. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, Chen Z, Chai X,

Xiong J, Bai Y, Yang L, Zhu H, Fang W, et al: Camrelizumab in

patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma:

A multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2

trial. Lancet Oncol. 21:571–580. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J,

Shao G, Zhang Y, Xu L, Yin T, et al: Camrelizumab in combination

with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

(RESCUE): A nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer

Res. 27:1003–1011. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Qin S, Chan SL, Gu S, Bai Y, Ren Z, Lin X,

Chen Z, Jia W, Jin Y, Guo Y, et al: Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib

versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable

hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): A randomised, open-label,

international phase 3 study. Lancet. 402:1133–1146. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ayuso C, Rimola J, Vilana R, Burrel M,

Darnell A, García-Criado Á, Bianchi L, Belmonte E, Caparroz C,

Barrufet M, et al: Diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC): Current guidelines. Eur J Radiol. 101:72–81. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Schwartz LH, Seymour L, Litière S, Ford R,

Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, Shankar L, Bogaerts J, Chen A, Dancey J, et

al: RECIST 1.1-standardisation and disease-specific adaptations:

Perspectives from the RECIST working group. Eur J Cancer.

62:138–145. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Peng W, Pan Y, Xie L, Yang Z, Ye Z, Chen

J, Wang J, Hu D, Xu L, Zhou Z, et al: The emerging therapies are

reshaping the first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Therap

Adv Gastroenterol. 17:175628482412376312024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Feng T, Li Q, Zhu R, Yu C, Xu L, Ying L,

Wang C, Xu W, Wang J, Zhu J, et al: Tumor microenvironment

biomarkers predicting pathological response to neoadjuvant

chemoimmunotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma: Post-hoc analysis of a single center, phase 2 study. J

Immunother Cancer. 12:e0089422024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu Q, Zhang H, Xiao H, Ren A, Cai Y, Liao

R, Yu H, Wu Z and Huang Z: Discovery of novel diagnostic biomarkers

of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with immune infiltration.

Ann Med. 57:25036452025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Shigeta K, Datta M, Hato T, Kitahara S,

Chen IX, Matsui A, Kikuchi H, Mamessier E, Aoki S, Ramjiawan RR, et

al: Dual programmed death receptor-1 and vascular endothelial

growth factor receptor-2 blockade promotes vascular normalization

and enhances antitumor immune responses in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Hepatology. 71:1247–1261. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ciciola P, Cascetta P, Bianco C, Formisano

L and Bianco R: Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with

anti-angiogenic agents. J Clin Med. 9:6752020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ju S, Zhou C, Yang C, Wang C, Liu J, Wang

Y, Huang S, Li T, Chen Y, Bai Y, et al: Apatinib plus camrelizumab

with/without chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A

real-world experience of a single center. Front Oncol.

11:8358892022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cai M, Huang W, Huang J, Shi W, Guo Y,

Liang L, Zhou J, Lin L, Cao B, Chen Y, et al: Transarterial

chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor for

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study.

Front Immunol. 13:8483872022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Li T, Guo J, Liu Y, Du Z, Guo Z, Fan Y,

Cheng L, Zhang Y, Gao X, Zhao Y, et al: Effectiveness and

tolerability of camrelizumab combined with molecular targeted

therapy for patients with unresectable or advanced HCC. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 72:2137–2149. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yuan G, Cheng X, Li Q, Zang M, Huang W,

Fan W, Wu T, Ruan J, Dai W, Yu W, et al: Safety and efficacy of

camrelizumab combined with apatinib for advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: A multicenter

retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther. 13:12683–12693. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Mei K, Qin S, Chen Z, Liu Y, Wang L and

Zou J: Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in second-line or

above therapy for advanced primary liver cancer: Cohort A report in

a multicenter phase Ib/II trial. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0021912021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen D, Chen X, Xu L, Wang Y, Zhu L and

Kang M: Camrelizumab combined with apatinib in the treatment of

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A real-world assessment.

Neoplasma. 70:580–587. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

He MK, Zou RH, Wei W, Shen JX, Zhao M,

Zhang YF, Lin XJ, Zhang YJ, Guo RP and Shi M: Comparison of stable

and unstable ethiodized oil emulsions for transarterial

chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: Results of a

single-center double-blind prospective randomized controlled trial.

J Vasc Interv Radiol. 29:1068–1077.e2. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Qin S, Li Q, Gu S, Chen X, Lin L, Wang Z,

Xu A, Chen X, Zhou C, Ren Z, et al: Apatinib as second-line or

later therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

(AHELP): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised,

placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

6:559–568. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hou Z, Zhu K, Yang X, Chen P, Zhang W, Cui

Y, Zhu X, Song T, Li Q, Li H and Zhang T: Apatinib as first-line

treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A

phase II clinical trial. Ann Transl Med. 8:10472020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Jin ZC, Zhong BY, Chen JJ, Zhu HD, Sun JH,

Yin GW, Ge NJ, Luo B, Ding WB, Li WH, et al: Real-world efficacy

and safety of TACE plus camrelizumab and apatinib in patients with

HCC (CHANCE2211): A propensity score matching study. Eur Radiol.

33:8669–8681. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chen ICY, Dungca LBP, Yong CC and Chen CL:

Sequential living donor liver transplantation after liver resection

optimizes outcomes for patients with high-risk hepatocellular

carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 24:50–56. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhu HK, Mou HB, Wang ZY, Zhang W, Zhu D,

Zhong SY, Zheng SS and Zhuang L: Adjuvant chemotherapy improves

post-transplant outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. S1499-3872(25)00093-1. 2025.(Epub

ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|