Introduction

According to GLOBOCAN statistics, lung cancer is the

most frequently diagnosed cancer globally and a major contributor

to cancer-related deaths worldwide, accounting for ~12.4% of all

new cancer cases and 18.7% of all cancer deaths in 2022 (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),

primarily consisting of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung

squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), is the predominant form of lung

cancer (2). In previous years,

substantial strides have been made in the treatment of lung cancer,

including advancements in screening, diagnosis and minimally

invasive treatments. Additionally, progress in radiotherapy,

including stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has become an

effective approach for treating lung cancer (3–5).

Meanwhile, the emergence of new targeted therapies and

immunotherapies has markedly improved the survival rate of patients

with NSCLC (6,7). Patients with NSCLC who are eligible

for targeted therapy and immunotherapy now have a longer survival

time, with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 15.0 to 62.5%,

depending on the biomarkers (8).

This underscores the importance of identifying new molecular

markers and therapeutic targets for NSCLC.

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled

receptor 4 (LGR4/GPCR48) belongs to the GPCR family and can

regulate developmental pathways through typical G protein signaling

(9). LGR4 is also involved in cell

proliferation and organ development. For example, LGR4 deficiency

decreases the migration and proliferation of eyelid epidermal

keratinocytes, and it also disrupts postnatal intestinal crypt

development, leading to defective epithelial proliferation and

abnormal Paneth cell differentiation (10). Moreover, numerous studies have

reported that LGR4 promotes tumor progression, such as in

colorectal (11), breast (12) and prostate (13) cancer. A recent study indicates that

the R-spondin (RSPO)-LGR4/5-E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ZNRF3

(ZNRF3)/E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF43 (RNF43) signaling complex

critically regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatic biology

(14). Dysregulation of the

RSPO-LGR4/5-ZNRF3/RNF43 complex, commonly caused by RSPO

overexpression or loss-of-function mutations in ZNRF3/RNF43,

constitutes a major oncogenic driver in hepatocellular carcinoma

that induces constitutive Wnt/β-catenin activation (15). However, another study indicates that

LGR4 potentiates breast cancer metastasis via a Wnt-independent

mechanism, wherein it directly interacts with epidermal growth

factor receptor (EGFR) and suppresses E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase

CBL-mediated ubiquitination, thereby impeding EGFR degradation and

augmenting EGFR signaling activation (16). Nevertheless, the function of LGR4 in

NSCLC requires further investigation.

The present study aimed to investigate the role of

LGR4 in NSCLC and potential mechanisms underlying its involvement

in tumor progression. Understanding the contribution of LGR4 may

provide insights into its significance in NSCLC pathophysiology and

its potential as a therapeutic target.

Materials and methods

Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) data

NSCLC mRNA sequencing data were retrieved from TCGA,

comprising 1,043 tumor samples and 110 normal samples from

TCGA-LUAD and TCGA-LUSC (cancer.gov/tcga). The data were analyzed

using R software (version 4.3.3; R Foundation) to determine LGR4

gene expression levels in NSCLC. Patients were divided into high

and low LGR4 expression groups based on the median expression.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed using the log-rank

test.

Tissue samples from patients

To evaluate the prognostic relevance of LGR4

expression in NSCLC, two independent tissue microarrays (TMA1 and

TMA2) were utilized to validate its association with clinical

outcomes. TMA1 (cat. no. ZL-lug1201) included 60 pairs of NSCLC

tumors and paracancerous tissue, sourced from Superbiotek, for

comparing LGR4 expression. TMA2 comprised samples from 140 patients

with NSCLC and 10 normal controls (28 female, 112 males) who

underwent surgery at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Zhongshan

Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China) between January and

December 2005. The normal control lung tissue samples were resected

from patients undergoing surgery for benign pulmonary diseases

(such as pulmonary bulla) and confirmed tumor-free by

histopathological examination. Clinical follow-ups were conducted

until July 2013 and stages Ia-IIIa, according to the American Joint

Committee on Cancer and Union for International Cancer Control

criteria (17).

Immunohistochemical (IHC)

staining

The TMA of both groups was stained

immunohistochemically with rabbit anti-LGR4 (Proteintech Group,

Inc.; cat. no. 20150-1-AP; 1:400). Tissue sections were baked at

59°C for 60 min and then immersed sequentially in xylene and an

ethanol series for 10 min each. After hydration and washing in

distilled water for 10 min, the sections were exposed to 3%

H2O2 for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was

performed by diluting the Antigen Retrieval Solution (Weiao; cat.

no. WH1034; 1:1 and heating it in a pressure cooker to boiling

(~100°C). Tissue sections were steamed for 2 min 30 sec, then

cooled to room temperature and washed twice with 1X PBS (Weiao,

China; cat. no. WB6020) for 15 min each. The sections were blocked

with 5% BSA (Weiao, China; cat. no. WH2051) at room temperature for

35 min, then incubated overnight with the primary antibody (rabbit

anti-LGR4; Proteintech, Wuhan, China; cat. no. 20150-1-AP; 1:400)

at 4°C. After four washes with PBS (15 min each), the sections were

incubated with the secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG; ImmunoWay, China; cat. no. RS0002; 1:100) at 37°C

for 35 min, followed by further washing. The color reaction was

developed according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by

hematoxylin counterstaining at room temperature for 1 min and a 10

min wash. Finally, dehydration of the sections was carried out

through an ethanol gradient and xylene, followed by mounting with a

sealing agent.

The average optical density (AOD) values from TMA1

were analyzed using a paired Student's t-test with GraphPad Prism

software (Dotmatics; version 10.1.2). For TMA2, AOD values were

divided into high- and low-expression groups based on the median

cutoff. Clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in

Table I, and univariate and

multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to evaluate

whether LGR4 expression serves as an independent prognostic factor

in NSCLC. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was then conducted to

assess the prognostic significance of LGR4 expression during the

clinical follow-up period.

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics of

126 patients with non-small cell lung cancer. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics of

126 patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

| Characteristic | Total (n=126) | High LGR4

expression (n=63) | Low LGR4 expression

(n=63) | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age,

years | 59.8±10.2 | 59.1±10.6 | 60.5±9.8 | 0.455 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.826 |

|

Male | 100 (79.4) | 51 (81.0) | 49 (77.8) |

|

|

Female | 26 (20.6) | 12 (19.0) | 14 (22.2) |

|

| Histological type,

n (%) |

|

|

| 0.017 |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 48 (38.1) | 17 (27.0) | 31 (49.2) |

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma | 78 (61.9) | 46 (73.0) | 32 (50.8) |

|

| Tumor stage, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.304 |

| I | 48 (38.1) | 20 (31.7) | 28 (44.4) |

|

| II | 40 (31.7) | 21 (33.3) | 19 (30.2) |

|

|

III | 38 (30.2) | 22 (34.9) | 16 (25.4) |

|

| Ki-67 (%) |

|

|

| 0.434 |

|

Negative | 89 (70.6) | 42 (66.7) | 47 (74.6) |

|

|

Positive | 37 (29.4) | 21 (33.3) | 16 (25.4) |

|

| Tumor location, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.284 |

|

Left | 59 (46.8) | 26 (41.3) | 33 (52.4) |

|

|

Right | 67 (53.2) | 37 (58.7) | 30 (47.6) |

|

Cell and cell line culture

Human healthy lung epithelial cells (BEAS-2B; cat.

no. TCH-C132), and NSCLC cell lines A549 (cat. no. TCH-C116) and

H226 (cat. no. TCH-C279) were obtained from Haixing Biosciences and

cultured in DMEM (cat. no. BL305A, Biosharp) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. SLB-13011-8611; Zhejiang Tianhang

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at

37°C.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

Cells were transfected with one of three siRNAs

targeting LGR4 from the ‘siRNA 3-in-1 package’ (Ruibo Bio,

Shanghai, China), and with a non-targeting scrambled control si-NC.

The sequences (5′-3′) were as follows: si-LGR4 #1: forward

GAAAGAACUCAAAGUUCUAAC, reverse UAGAACUUUGAGUUCUUUCAA. si-LGR4#2:

forward GGUAGUUCUGCAUCUUCAUAA, reverse AUGAAGAUGCAGAACUACCAG.

si-LGR4#3: forward GCUGCGGCGGACUGCUGAAGG, reverse

UUCAGCAGUCCGCCGCAGCGG si-NC: forward UUCUUCGAAGGUGUCACGUTT, reverse

ACGUGACACCUUCGAAGAATT. A549 and H226 cells were seeded

3×105 into 6-well plates, each with 2 ml of complete

medium as aforementioned. This allowed the cells to reach ~50%

confluence by the time of transfection. Cells were transfected

using Lipo 8000™ Transfection Reagent (cat. no. C0533

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, China). Cells were transfected

with siRNAs at a final concentration of 50 nM at 37°C

(CLM-170B-8-CN, ESCO, Singapore). Transfection efficiency was

evaluated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) at 48

h post-transfection.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from the NSCLC cell lines and

BEAS-2B cells using the FastPure® Cell/Tissue Total RNA

Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), following the protocol

provided by the manufacturer. cDNA synthesis was performed using

the HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper)

(Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Any genomic DNA present was removed and then the

extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Next,

gene-specific primers were designed for the target genes using

SnapGene software (version 7.2.1, GSL Biotech LLC), ensuring that

the primers only amplified the desired gene fragment and avoided

spanning splice junctions. Primer specificity was validated using

the NCBI Primer-BLAST tool (version 2.53.0,

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) to ensure primers would not

amplify non-target sequences. Finally, the primers were synthesized

through Agena Bioscience, Inc., and the sequences of the primers

are provided in Table II.

| Table II.Primer sequence for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table II.

Primer sequence for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene name and

primer direction | Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| LGR4 forward |

ACTCAAAGTTCTAACGCTCCAG |

| LGR4 reverse |

AAAGCACTCAGCCCTCGAATG |

| GAPDH forward |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

| GAPDH reverse |

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

RT-qPCR was conducted with the Taq Pro Universal

SYBR quantitative PCR (qPCR) Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.)

under the following thermal cycling conditions: An initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec followed by 40 cycles consisting of

denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec and extension at 60°C for 60 sec.

Gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (18), with GAPDH serving as

the endogenous control.

Western blot assay

Western blotting was used to evaluate the protein

expression of LGR4. Proteins were extracted from A549 and H226

cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, quantified by BCA assay.

10% Cell-Free Acrylamide System (CFAS) separation gels were

prepared by combining CFAS PAGE Separation Gel A (cat. no. PE004-A,

Zhonghui Hecai, China) and Separation Gel B (cat. no. PE004-B,

Zhonghui Hecai, China) at a 1:1 ratio, following the manufacturer's

instructions (10% CFAS PAGE Rapid Gel Preparation Kit, PE004,

Zhonghui Hecai, China), and thoroughly homogenized before use.

Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes using 1× rapid

transfer buffer and blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk in 1× TBST

(0.1% Tween-20, Biosharp, China) at room temperature for 2 h.

Membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies

against LGR4 (cat. no. ER63609; HuaAn Biotech, China; 1:400) and

GAPDH (cat. no. R1210-1; HuaAn Biotech, China; 1:400) overnight at

4°C, washed with 1× TBST (0.1% Tween-20) 5×7 min, then incubated

with HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. A0208; Beyotime

Biotechnology, China; 1:10,000) at room temperature for 80 min,

followed by the same TBST washing cycles 5×7 min. Protein signals

were detected using Super ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate (cat. no.

BL520A, Biosharp, China). Images were analyzed using Tanon Image

software (https://tanon.cnreagent.com/).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

To examine the effect of LGR4 on the proliferative

capacity of NSCLC cells, cell proliferation in A549 and H226 cells

was measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after transfection with si-LGR4

using the CCK-8 assay. A total of 2,500 cells (A549 and H226) were

seeded in 100 µl of complete medium into each well of a 96-well

plate. Then 10 µl enhanced CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. C0041; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was dispensed into each well. Cells

without the culture medium and CCK-8 solution served as the blank

control. After incubating both the experimental and control groups

in a cell incubator for 2 h, absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Flow cytometry apoptosis assay

Following transfection, A549 and H226 cells were

digested with 0.25% trypsin (without EDTA and phenol red; cat. no.

T1350; Beijing Solarbio, China) for 3 min at room temperature until

the cells detached. The detached cells were centrifuged at 1,000 ×

g for 5 min at room temperature. Thereafter, the supernatant was

discarded and the cells were collected. After washing twice with

PBS, the cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium

iodide using the Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (cat. no. C1062M,

Beyotime Biotechnology, China), and incubated on ice in the dark

for 20 min. Finally, apoptosis was then analyzed using BD

Accuri™ C6 software (version 1.0.264.21, BD Biosciences)

on the FACS Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

Transwell assay

A549 and H226 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (1:1)

medium supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. SLB-13011-8611,

Sijiqing, China) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. BL505A,

Biosharp, China). Transwell inserts with an 8-µm pore size, 24-well

format (cat. no. 3422, Corning, USA) were used for both migration

and invasion assays. For invasion assays, the upper surface of the

inserts was precoated with Matrigel (cat. no. 082704; Mogengel) at

37°C for 30 min; uncoated inserts were used for migration assays. A

total of ~5×10⁵ cells were seeded into the upper chambers

containing serum-free DMEM/F12, while 500 µl of medium supplemented

with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers as a chemoattractant.

After 48 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO₂, non-migrated or

non-invaded cells remaining on the upper membrane surfaces were

removed with a cotton swab. Cells on the lower membrane surfaces

were fixed with methanol for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal

violet (cat. no. BL802A, Biosharp, China) for 20 min at room

temperature. Migrated or invaded cells were quantified in five

random fields under an inverted light microscope (×400; Model

CKx53, Olympus, Japan).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(GSEA)

To explore the possible oncogenic mechanisms of LGR4

in NSCLC, The LGR4 expression matrix was extracted from TCGA NSCLC

dataset (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga),

comprising 1,043 tumor samples, using R software (version 4.3.3; R

Foundation), and subsequently converted into gct and cls files for

GSEA. Thereafter, GSEA 4.3.3 software (Broad Institute) was

employed to analyze the signaling pathways activated in tumor

samples exhibiting high LGR4 expression. High and low expression

groups were defined using the median LGR4 expression as the cut-off

(4.7589). Specifically, the KEGG canonical pathway gene set

(c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt,

ftp://ftp.broadinstitute.org/pub/gsea/msigdb/human/gene_sets/c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt)

and the HALLMARK gene set (h.all.v2025.1.Hs.symbols.gmt,

ftp://ftp.broadinstitute.org/pub/gsea/msigdb/human/gene_sets/h.all.v2025.1.Hs.symbols.gmt)

were used. Pathways with |normalized enrichment score|>1,

P<0.05 and FDR <0.05 were regarded as significantly

enriched.

Statistical analysis

Intergroup All quantitative data are presented as

the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments.

Two-group comparisons were performed using paired or unpaired

Student's t-tests. Multi-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way

ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test. Time-course experiments, such

as CCK8 assays, were evaluated by two-way ANOVA with Šídák's

multiple comparisons test. Survival probability estimations were

performed with Kaplan-Meier methodology and log-rank testing.

Prognostic factor screening used uni- and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards models. Statistical analyses were performed

with GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.2; Dotmatics) and R software

(version 4.3.3; R Foundation). P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference. All analyses were repeated

at least three times.

Results

LGR4 expression is upregulated in

NSCLC

The present investigation into the role of LGR4 in

NSCLC began with an evaluation of its expression using data

obtained from the TCGA database. The analysis revealed that LGR4

expression was significantly higher in NSCLC samples than in

healthy lung tissue (P<0.001; Fig.

1A). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted to determine the

prognostic impact of LGR4. The findings indicated that patients

with elevated LGR4 expression had shorter overall survival times

compared with those with low expression (P=0.013; Fig. 1B). To further confirm these results,

the expression of LGR4 in NSCLC cell lines was assessed by western

blotting and RT-qPCR. Both the protein and mRNA protein levels of

LGR4 were significantly elevated in NSCLC compared with those in

healthy tissues (Fig. 1C and D),

with differences considered statistically significant (both

P<0.05). Significant downregulation of LGR4 was also

consistently observed across all three siRNA knockdown groups via

qPCR analysis (all P<0.05; Fig.

1E). Among the three siRNAs targeting LGR4, si-LGR4 #1 and #2

showed comparable knockdown efficiency in preliminary experiments.

To maintain consistency in subsequent functional assays, si-LGR4 #2

was used for all following experiments.

Expression of LGR4 in NSCLC

tissues

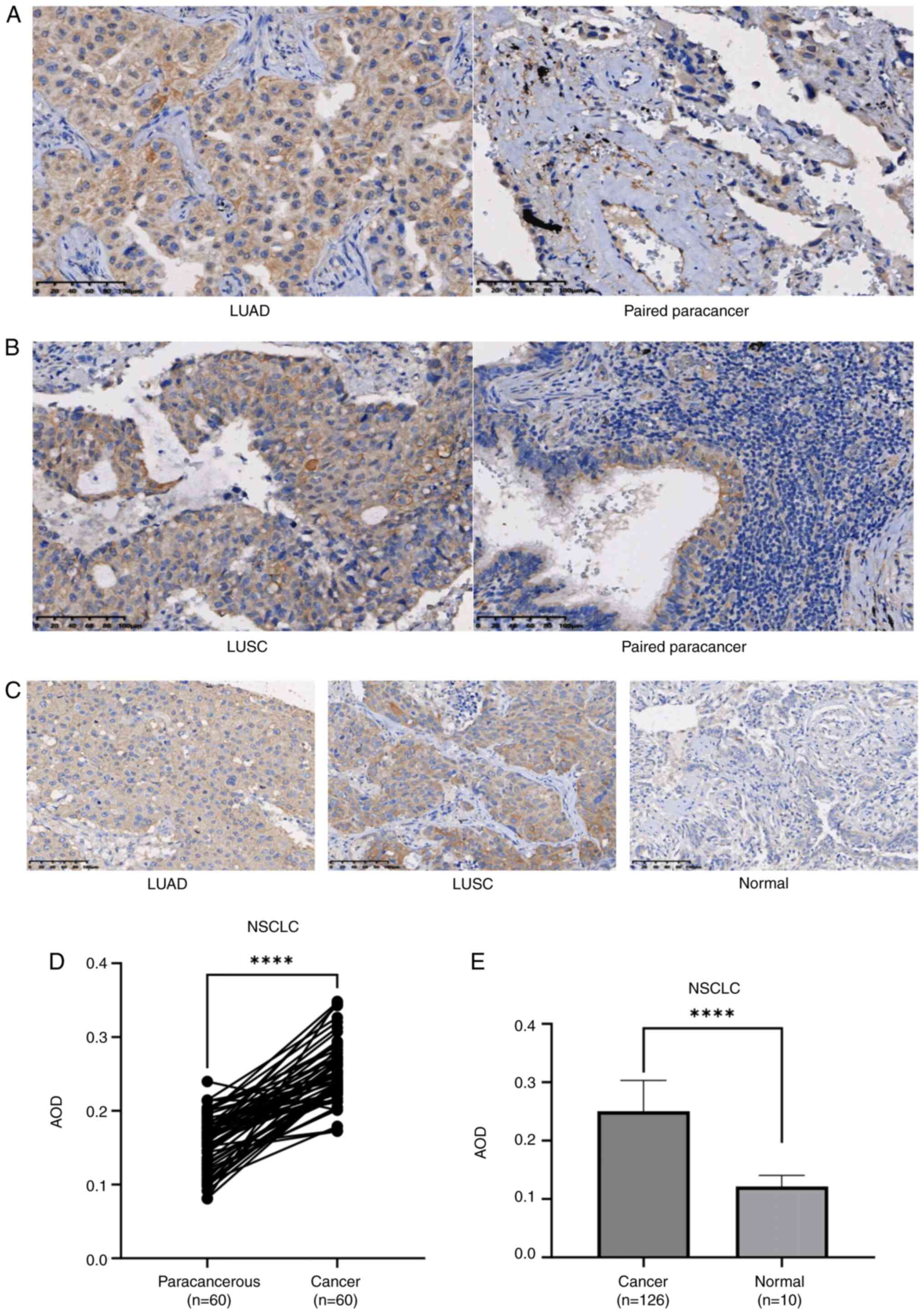

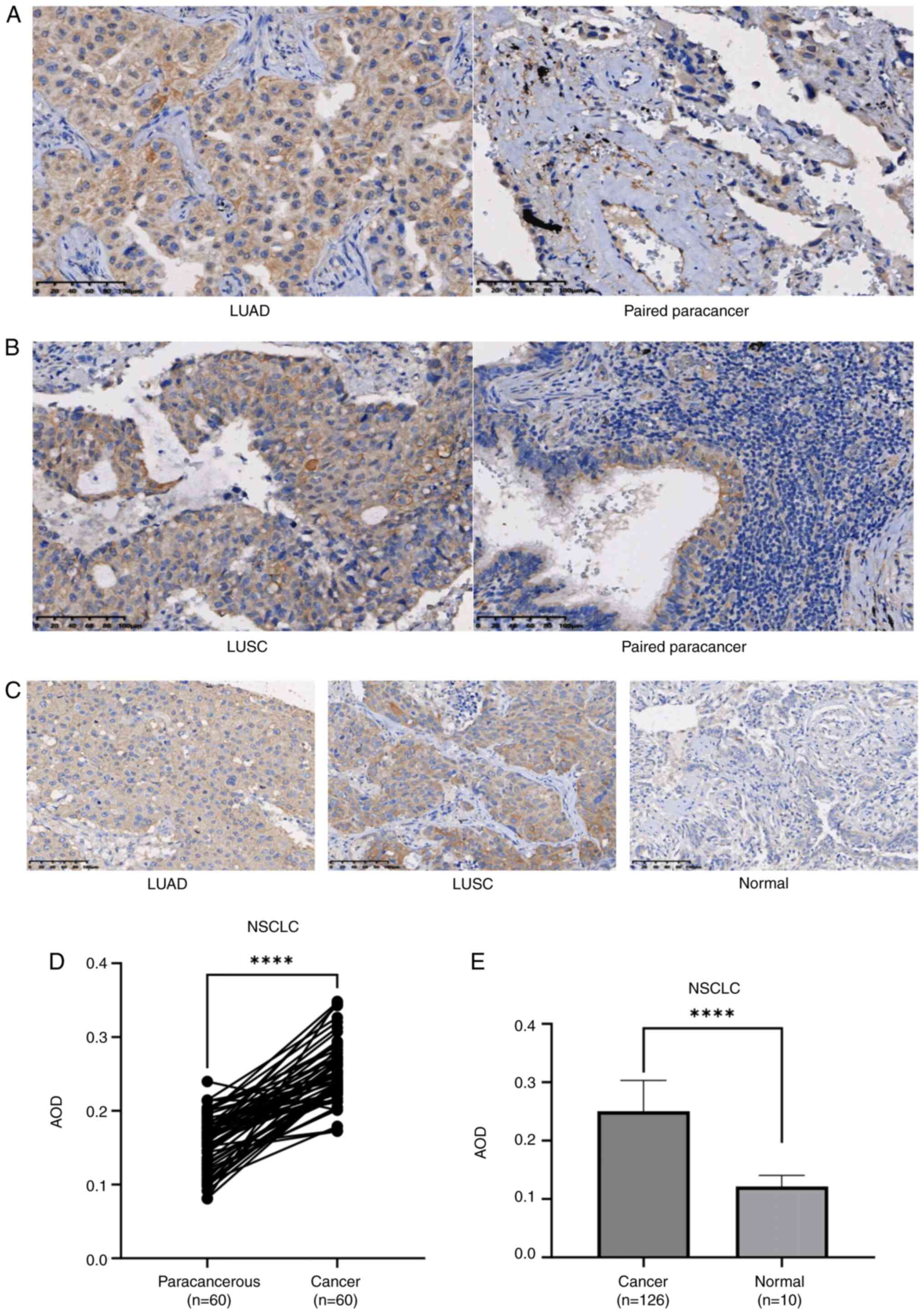

IHC staining of two independent TMAs revealed

predominant cytoplasmic localization of LGR4 within tumor cells.

Analysis of TMA1 demonstrated elevated LGR4 expression in both LUAD

and LUSC specimens compared with matched adjacent paracancerous

tissues (Fig. 2A and B). Consistent

with this finding, IHC evaluation of TMA2 displayed increased LGR4

levels in malignant tissues compared with those in healthy lung

tissues (Fig. 2C). Matched-pair

analysis of 60 tumor/paracancerous samples from TMA1 confirmed

significantly higher LGR4 expression in the cancerous component vs.

the relevant paracancerous counterpart (P<0.0001; Fig. 2D). Moreover, LGR4 expression was

significantly increased in tumor specimens compared with healthy

lung tissue (n=10) (P<0.0001; Fig.

2E).

| Figure 2.LGR4 is overexpressed in tumor

tissues. (A) Lung adenocarcinoma tissue (×200 magnification) and

adjacent non-tumor tissue (×200 magnification). (B) LUSC tissue

(×200 magnification) and adjacent non-tumor tissue (×200

magnification). (C) LUAD tissue (×200 magnification), LUSC tissue

(×200 magnification) and healthy tissue (×200 magnification). Scale

bar, 100 µm. (D) Comparison of LGR4 expression in TMA1 (paired

Student's t-test). (E) LGR4 expression in TMA2 (unpaired Student's

t-test). ****P<0.0001. LGR4, leucine-rich repeat-containing

G-protein coupled receptor 4; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma;

LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; TMA1, tissue microarray 1; TMA2, tissue

microarray 2; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; HR, hazard ratio;

AOD, average optical density. |

Association of LGR4 expression with

clinicopathological characteristics

IHC staining of TMA2 resulted in tissue core

detachment in some cases. Therefore, patients lacking evaluable

staining due to detachment were excluded, leaving 126 patients for

analysis. The baseline clinicopathological characteristics are

detailed in Table I. Patients were

stratified into high- and low-expression groups based on the median

AOD value of LGR4 (0.2512). As presented in Table I, LGR4 expression demonstrated a

significant association with histological tumor type (P=0.017;

Table I). However, no significant

associations were observed between LGR4 expression levels and

patient age (P=0.455), sex (P=0.826), TNM tumor stage P=0.304),

Ki-67 expression status (P=0.434) or tumor location (P=0.284).

Prognostic value of LGR4 in NSCLC

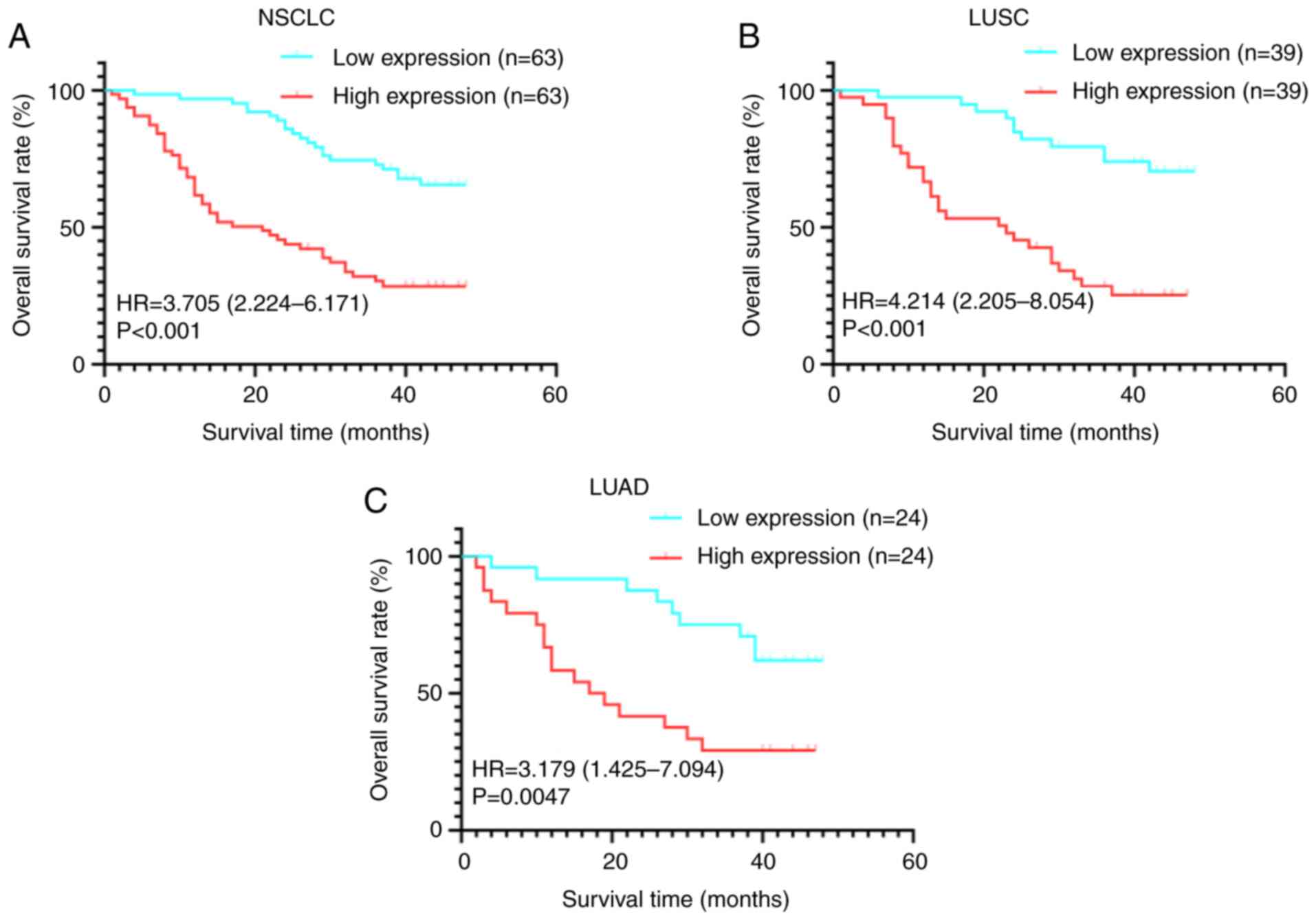

Analysis of long-term follow-up data from TMA2

demonstrated that patients with high LGR4 expression exhibited

significantly shorter overall survival times compared with those

with low LGR4 expression (Fig. 3A,

P<0.001). Furthermore, this adverse association was consistently

observed in both LUAD and LUSC subtypes, where high LGR4 expression

was associated with poorer survival outcomes relative to low

expression groups (both P<0.05; Fig.

3B and C). Subsequent univariate and multivariate Cox

proportional hazards regression analyses confirmed elevated LGR4

expression as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in

patients with NSCLC (P<0.001; Table III). Ultimately, both high LGR4

levels and advanced tumor stage (stage II and III; both P<0.05)

were identified as independent adverse prognostic factors.

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate

analysis. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate

analysis.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 0.98

(0.96–1.01) | 0.321 | 0.99

(0.97–1.03) | 0.833 |

| Sex (Male) | 1.14

(0.62–2.09) | 0.681 | 1.16

(0.62–2.15) | 0.648 |

| Ki-67

(Positive) | 1.41

(0.84–2.35) | 0.193 | 1.75

(0.98–3.14) | 0.061 |

| LGR4 | 3.55

(2.10–5.99) | <0.001 | 4.31

(2.43–7.63) | <0.001 |

| Histological

type |

|

|

|

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.00

(Reference) | NA | 1.00

(Reference) | NA |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 1.10

(0.67–1.81) | 0.702 | 2.22

(1.21–4.09) | 0.011 |

| Tumor stage |

|

|

|

|

| I | 1.00

(Reference) | NA | 1.00

(Reference) | NA |

| II | 2.23

(1.20–4.16) | 0.012 | 2.30

(1.20–4.40) | 0.012 |

|

III | 2.08

(1.10–3.95) | 0.024 | 1.96

(1.01–3.83) | 0.049 |

| Tumor location |

|

|

|

|

|

Left | 1.00

(Reference) | NA | 1.00

(Reference) | NA |

|

Right | 1.37

(0.84–2.26) | 0.209 | 1.01

(0.58–1.74) | 0.988 |

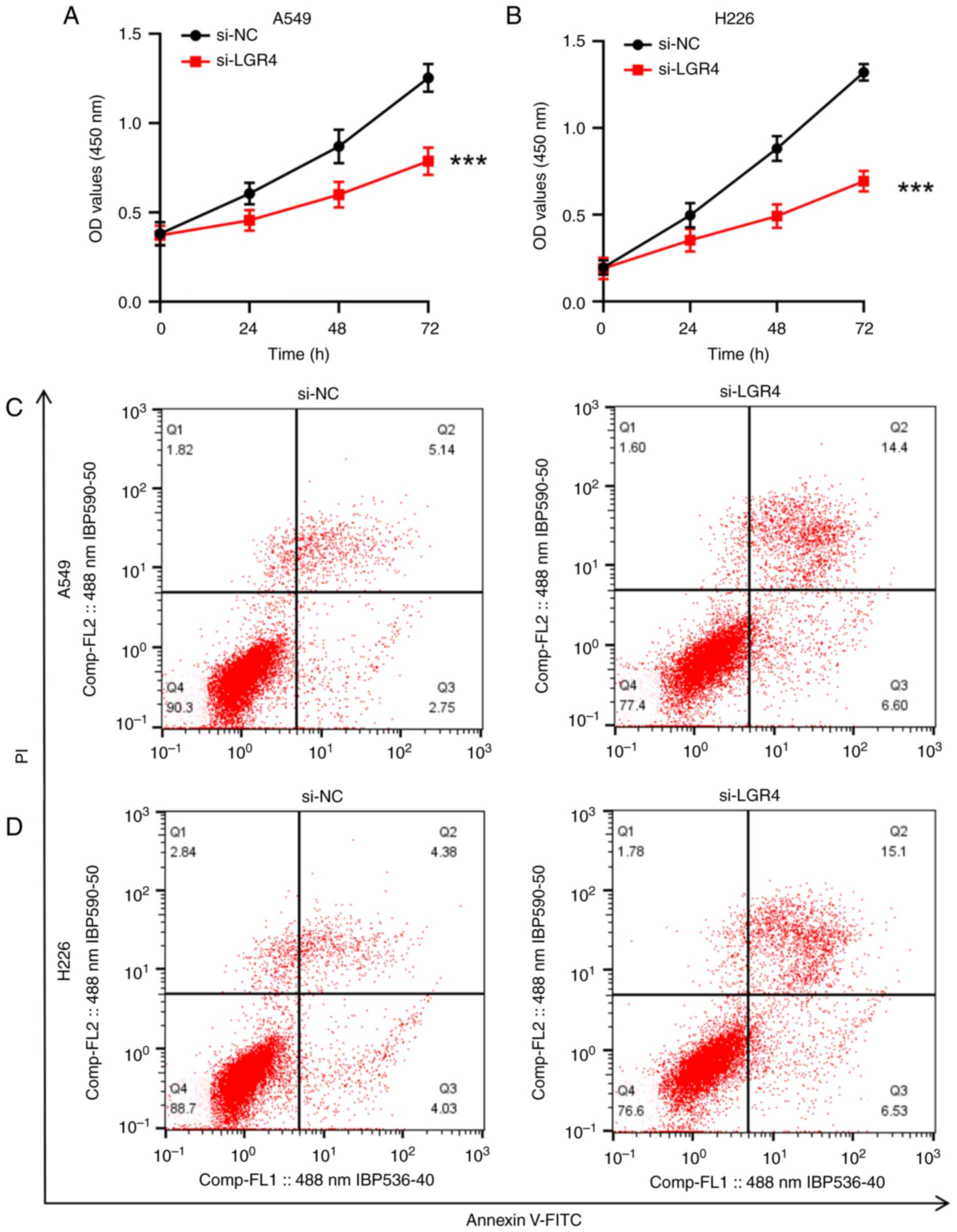

Knockdown of LGR4 inhibits the

proliferation of A549 and H226 cells

To investigate whether LGR4 knockdown could inhibit

the proliferation of NSCLC cells, a CCK-8 assay was conducted. The

results revealed a significant reduction in the proliferation of

both A549 and H226 cells at 24, 48 and 72 h following si-LGR4

transfection, (P<0.001; Fig. 4A and

B).

Knockdown of LGR4 promotes apoptosis

in A549 and H226 cells

Flow cytometry analysis indicated that silencing

LGR4 considerably increased the apoptotic rate in both A549 and

H226 cells relative to the si-NC control group, suggesting that

LGR4 depletion promotes apoptosis in these NSCLC cell lines (both

P<0.001; Fig. 4C and D).

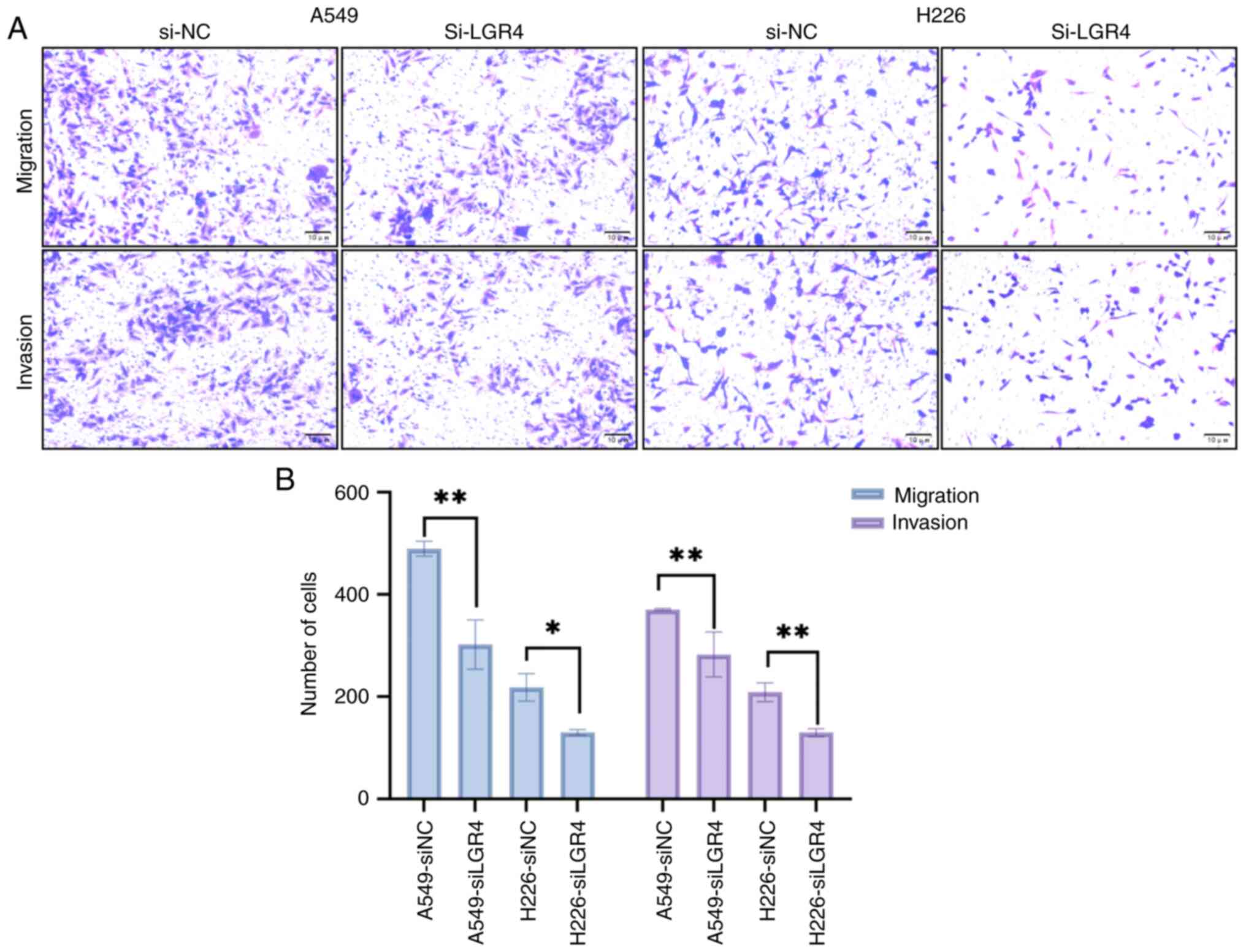

Knockdown of LGR4 inhibits invasion

and migration of A549 and H226 cells

To determine if LGR4 contributes to the invasive and

migratory behavior of NSCLC cells, the effect of LGR4 silencing on

the invasion and migration abilities of A549 and H226 cells was

evaluated using a Transwell assay. The results demonstrated that

transfection with si-LGR4 significantly decreased both the invasion

and migration abilities of A549 and H226 cells, indicating that

LGR4 depletion inhibits these key cellular processes (all

P<0.05; Fig. 5A and B).

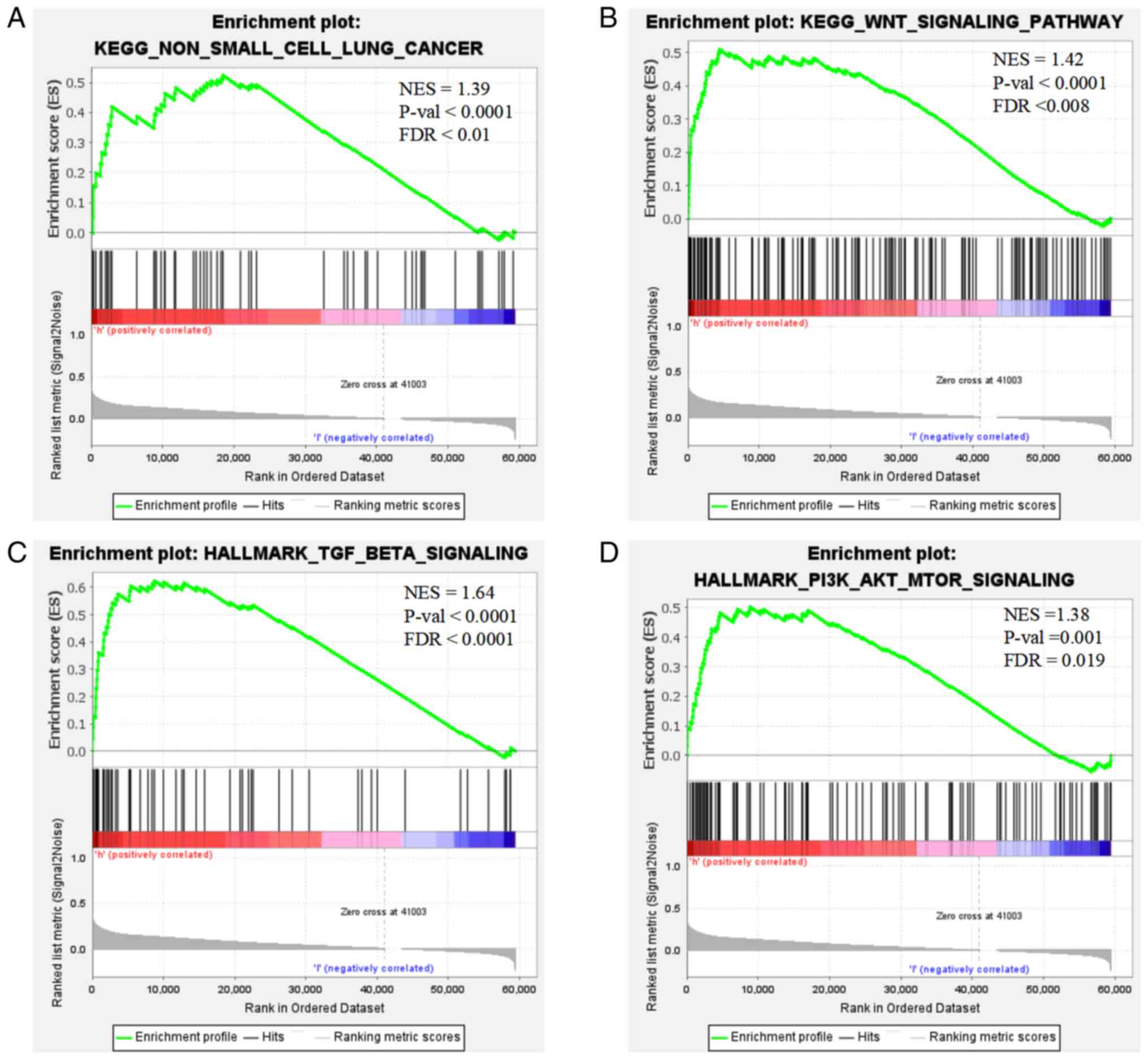

Enrichment analysis of LGR4

GSEA demonstrated that elevated LGR4 expression in

tumor samples was significantly enriched in the KEGG) ‘non-small

cell lung cancer’ pathway (Fig. 6A)

and was associated with activation of ‘Wnt signaling pathway’,

‘PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling’ and ‘TGF-β signaling’ (Fig. 6B-D).

Discussion

GPCRs constitute the most extensive class of cell

surface receptors that mediate signal transduction, and are notable

drivers of tumor progression and metastasis (19). As a member of the GPCR family, LGR4

exerts various regulatory effects in multiple cell types and acts

on numerous targets. In the liver, it controls key gluconeogenic

enzymes (such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase) via

Wnt/β-catenin, affecting glucose output (20). In osteoblasts, LGR4 regulates

glycolysis, and its loss reduces bone formation and strength

(21). Abnormal LGR4 signaling is

highly influential in cancer and other disease, with

loss-of-function mutations associated with osteoporosis,

electrolyte imbalance, and reduced body weight, and

gain-of-function mutations linked to increased bone density,

insulin resistance, and obesity (22). A growing body of evidence indicates

that LGR4 is integral to both the development and progression of

various cancer types. For instance, Steffen et al (23) observed that the transcriptional and

translational levels of LGR4 and LGR6 are upregulated in gastric

cancer, with LGR4 expression significantly associated with lymph

node metastasis. Additionally, Cui et al (24) found that the expression of LGR4,

LGR5 and LGR6 is elevated in gastrointestinal cancer, with LGR5

being enriched in cancer stem cells. Research has demonstrated that

RSPO2 and receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand co-opt

LGR4 as a shared receptor to synergistically over-activate

osteoclastogenesis, thereby disrupting bone homeostasis and

establishing a premetastatic niche conducive to tumor colonization,

which ultimately drives breast cancer bone metastasis. Targeting

LGR4 may represent a novel therapeutic strategy to intercept this

process (25). Upregulation of

microRNA (miR)-449b significantly suppresses the growth and

invasive capacity of NSCLC by modulating LGR4 (26). The association between LGR4

expression and the development of NSCLC remains to be

elucidated.

In the present study, LGR4 expression was initially

confirmed in NSCLC tissues using immunohistochemistry. A marked

elevation of LGR4 was detected in NSCLC tissues when benchmarked

against normal controls and histologically healthy adjacent areas.

Notably, relatively high LGR4 expression was observed in some

non-cancerous tissues. This may be attributed to the physiological

roles of LGR4 in healthy tissue homeostasis and regeneration. In

addition, the adjacent non-tumor tissues may be influenced by

tumor-associated factors such as inflammation or hypoxia, which

could upregulate LGR4 expression. Alternatively, individual

variation and tissue heterogeneity might also contribute to this

observation. Furthermore, higher LGR4 expression was linked to a

poor prognosis in patients with NSCLC, consistent with the

bioinformatics analysis in the present study. Univariate and

multivariate analyses established high LGR4 expression as an

independent predictor of poor prognosis in NSCLC. The functional

role of LGR4 was then investigated in two NSCLC cell lines.

Relative to healthy lung epithelial cells, LGR4 expression was

significantly elevated in the A549 lung adenocarcinoma cell line

and the H226 squamous cell carcinoma cell line. In addition, LGR4

knockdown increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation, invasion

and migration abilities in both A549 and H226 cells.

The present enrichment analysis revealed that high

LGR4 expression levels may be associated with the activation of

major signaling pathways, including the Wnt, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and

TGF-β signaling pathways. Moreover, the significant enrichment of

LGR4 within the KEGG ‘non-small cell lung cancer’ pathway indicates

that LGR4 may be a potential key driver in NSCLC progression.

Numerous studies have reported that LGR4 and its homologs LGR5 and

LGR6 influence cellular signaling primarily through the Wnt pathway

via their interaction with the ligand R-spondin (27–30).

Furthermore, research has shown that LGR4 can regulate the

expression of TGF-β1, thereby triggering the TGF-β1/Smad signaling

pathway and driving multiple myeloma progression (31). Additionally, according to a study by

Liang et al (32),

overexpression of LGR4 upregulates mTOR and the key effector AKT in

the PI3K/AKTt pathway. Building on these findings, it is proposed

that LGR4 may promote NSCLC progression through the activation of

these pathways. These results from previous studies imply that LGR4

could be strongly associated with the initiation and progression of

NSCLC.

In conclusion, LGR4 may represent a promising

therapeutic approach for patients with NSCLC. However, the present

study is confined to in vitro experiments, and animal

studies have yet to be conducted. In the present research,

bioinformatics analysis was utilized to predict the potential

signaling pathways that LGR4 may activate in NSCLC. To further

validate the reliability of LGR4 as a diagnostic biomarker, our

future studies will focus on exploring the upstream regulatory

molecules of LGR4 and conducting additional experiments for further

confirmation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Changzhou High-Level

Medical Talents Training Project (grant no. 2022CZBJ069), the

Changzhou Sci&Tech Program (grant no. CZ20220025), the ‘333

Project’ of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BRA2020157) and the 333

High-Level Talent Training Project (grant no. 2022-2).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XD was responsible for the conceptualization,

methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing the original

draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. XL provided the

software, analyzed and curated the data (which involved ollection,

organization, cleaning, and preservation of research data,

including the archiving of experimental results, preparation of

data tables, and processing and management of images/raw data), and

provided experimental supervision. YS and SZ interpreted data. ML

and ZG performed the experiments. KY conceived and designed the

study, supervised the project, and revised the manuscript for

important scientific content. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript. XD and KY confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Research Ethics Committee of The Third

Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Changzhou,

China) reviewed and approved the study [approval no. (2023)

KY422-01]. All participating patients and their families

voluntarily provided written informed consent. All tissue samples

were anonymized following ethical and legal guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

National Lung Screening Trial Research

Team, . Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD,

Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM and Sicks JD:

Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic

screening. N Engl J Med. 365:395–409. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, Michalski

J, Straube W, Bradley J, Fakiris A, Bezjak A, Videtic G, Johnstone

D, et al: Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early

stage lung cancer. JAMA. 303:1070–1076. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sun B, Brooks ED, Komaki R, Liao Z, Jeter

M, McAleer M, Balter PA, Welsh JD, O'Reilly M, Gomez D, et al:

Long-term outcomes of salvage stereotactic ablative radiotherapy

for isolated lung recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer: A phase

II clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol. 12:983–992. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG,

Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe

S, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive

non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 375:1823–1833. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó

L, Ahn MJ, De Pas T, Besse B, Solomon BJ, Blackhall F, et al:

Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 368:2385–2394. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Riely GJ, Wood DE, Ettinger DS, Aisner DL,

Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, et

al: Non-Small cell lung cancer, version 4.2024, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:249–274. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Filipowska J, Kondegowda NG, Leon-Rivera

N, Dhawan S and Vasavada RC: LGR4, a G protein-coupled receptor

with a systemic role: From development to metabolic regulation.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8670012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ordaz-Ramos A, Rosales-Gallegos VH,

Melendez-Zajgla J, Maldonado V and Vazquez-Santillan K: The role of

LGR4 (GPR48) in normal and cancer processes. Int J Mol Sci.

22:46902021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zheng H, Liu J, Cheng Q, Zhang Q, Zhang Y,

Jiang L, Huang Y, Li W, Zhao Y, Chen G, et al: Targeted activation

of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer via LGR4 targeting overcomes

acquired drug resistance. Nat Cancer. 5:572–589. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yue Z, Yuan Z, Zeng L, Wang Y, Lai L, Li

J, Sun P, Xue X, Qi J, Yang Z, et al: LGR4 modulates breast cancer

initiation, metastasis, and cancer stem cells. FASEB J.

32:2422–2437. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liang F, Zhang H, Cheng D, Gao H, Wang J,

Yue J, Zhang N, Wang J, Wang Z and Zhao B: Ablation of LGR4

signaling enhances radiation sensitivity of prostate cancer cells.

Life Sci. 265:1187372021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Annunziato S, Sun T and Tchorz JS: The

RSPO-LGR4/5-ZNRF3/RNF43 module in liver homeostasis, regeneration,

and disease. Hepatology. 76:888–899. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Planas-Paz L, Orsini V, Boulter L,

Calabrese D, Pikiolek M, Nigsch F, Xie Y, Roma G, Donovan A, Marti

P, et al: The RSPO-LGR4/5-ZNRF3/RNF43 module controls liver

zonation and size. Nat Cell Biol. 18:467–479. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yue F, Jiang W, Ku AT, Young AIJ, Zhang W,

Souto EP, Gao Y, Yu Z, Wang Y, Creighton CJ, et al: A

Wnt-independent LGR4-egfr signaling axis in cancer metastasis.

Cancer Res. 81:4441–4454. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dorsam RT and Gutkind JS:

G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 7:79–94.

2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fang Q, Ye L, Han L, Yao S, Cheng Q, Wei

X, Zhang Y, Huang J, Ning G, Wang J, et al: LGR4 is a key regulator

of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 229:183–194. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang YY, Zhou YM, Xu JZ, Sun LH, Tao B,

Wang WQ, Wang JQ, Zhao HY and Liu JM: Lgr4 promotes aerobic

glycolysis and differentiation in osteoblasts via the canonical

Wnt/β-catenin pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 36:1605–1620. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang L, Wang J, Gong X, Fan Q, Yang X, Cui

Y, Gao X, Li L, Sun X, Li Y and Wang Y: Emerging roles for LGR4 in

organ development, energy metabolism and carcinogenesis. Front

Genet. 12:7288272022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Steffen JS, Simon E, Warneke V, Balschun

K, Ebert M and Röcken C: LGR4 and LGR6 are differentially expressed

and of putative tumor biological significance in gastric carcinoma.

Virchows Arch. 461:355–365. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cui J, Toh Y, Park S, Yu W, Tu J, Wu L, Li

L, Jacob J, Pan S, Carmon KS and Liu QJ: Drug conjugates of

antagonistic R-spondin 4 mutant for simultaneous targeting of

leucine-rich repeat-containing g protein-coupled receptors 4/5/6

for cancer treatment. J Med Chem. 64:12572–12581. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yue Z, Niu X, Yuan Z, Qin Q, Jiang W, He

L, Gao J, Ding Y, Liu Y, Xu Z, et al: RSPO2 and RANKL signal

through LGR4 to regulate osteoclastic premetastatic niche formation

and bone metastasis. J Clin Invest. 132:e1445792022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yang D, Li JS, Xu QY, Xia T and Xia JH:

Inhibitory effect of MiR-449b on cancer cell growth and invasion

through LGR4 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Curr Med Sci.

38:582–589. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS,

Teunissen H, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Peters PJ, van de Wetering M,

et al: Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate

R-spondin signalling. Nature. 476:293–297. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Luo J, Yang Z, Ma Y, Yue Z, Lin H, Qu G,

Huang J, Dai W, Li C, Zheng C, et al: LGR4 is a receptor for RANKL

and negatively regulates osteoclast differentiation and bone

resorption. Nat Med. 22:539–546. 2016. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

de Lau W, Peng WC, Gros P and Clevers H:

The R-spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: Regulator of Wnt signal strength.

Genes Dev. 28:305–316. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Han XH, Jin YR, Tan L, Kosciuk T, Lee JS

and Yoon JK: Regulation of the follistatin gene by RSPO-LGR4

signaling via activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway in skeletal

myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 34:752–764. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yi Z, Ma T, Liu J, Tie W, Li Y, Bai J, Li

L and Zhang L: LGR4 promotes tumorigenesis by activating

TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway in multiple myeloma. Cell Signal.

110:1108142023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Liang F, Yue J, Wang J, Zhang L, Fan R,

Zhang H and Zhang Q: GPCR48/LGR4 promotes tumorigenesis of prostate

cancer via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Med Oncol. 32:492015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

![LGR4 is highly expressed in NSCLC. (A)

Unpaired analysis. TCGA [NSCLC (n=1,043) vs. healthy tissues

(n=110); unpaired Student's t-test]. (B) High LGR4 expression is

associated with a poor prognosis in patients with NSCLC (data

fromTCGA). (C) Western blot analysis showed the expression level of

LGR4 protein in NSCLC cell lines. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. (D) RT-qPCR analysis showed the

expression level of LGR4 mRNA in NSCLC cell lines (one-way ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test). (E) RT-qPCR

analysis showed that si-LGR4 transfection significantly reduced

LGR4 expression in A549 and H226 cells compared with the si-NC

group (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison

test). LGR4, leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled

receptor 4; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

si-NC, small-interfering RNA negative control.](/article_images/ol/30/6/ol-30-06-15304-g00.jpg)