Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive and

highly malignant subtype of lung cancer, accounting for ~15% of all

lung cancer cases (1,2). Its clinical features include rapid

tumor growth and a high propensity for distant metastasis. The fact

that most patients are diagnosed at the extensive stage

[extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC)] (3) means that the prognosis of ES-SCLC is

poor, with the median overall survival (OS) typically <12

months, and survival time further shortens with the development of

treatment resistance (4,5). Currently, platinum-based doublet

chemotherapy [such as etoposide plus cisplatin (EP) or etoposide

plus carboplatin (EC)] remains the first-line standard treatment

for patients with ES-SCLC (6,7).

Although these chemotherapy regimens show high efficacy in the

early stages, patients often face a gradual decline in treatment

effectiveness due to the rapid progression of the tumor and the

development of resistance (8,9).

Moreover, chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression, which often causes

severe clinical adverse events such as anemia, neutropenia and

thrombocytopenia, significantly impacts the quality of life (QoL)

and survival prognosis of patients (10,11).

This myelosuppression, while a predictable consequence of

chemotherapy, poses a considerable challenge in maintaining

adequate treatment regimens and leads to complications such as

prolonged hospitalizations and additional supportive care needs.

Furthermore, these adverse effects often result in dose reductions

or interruptions, further reducing the overall efficacy of cancer

treatment. Traditional methods to address myelosuppression mainly

involve symptomatic supportive treatments, such as the use of

granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or blood transfusions

(12,13). However, these methods are reactive

rather than preventive, often being administered after the onset of

myelosuppression. This delay in intervention fails to address the

underlying issue in a timely manner and may still carry certain

risks, such as infections from prolonged neutropenia or

transfusion-related complications.

Therefore, the development of novel strategies to

manage myelosuppression, especially preventive treatments, is of

utmost importance to improve patient outcomes and treatment

adherence. Trilaciclib, a short-acting and reversible

cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor, has garnered considerable

attention in clinical practice as a potential myeloprotective agent

for patients undergoing chemotherapy (14–16).

Trilaciclib functions by transiently blocking hematopoietic stem

cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, preventing

chemotherapy drugs from damaging bone marrow cells, thereby

effectively preventing chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression

(17). Several clinical studies

have demonstrated that trilaciclib has a significant

myeloprotective effect in patients with ES-SCLC. It not only

considerably reduces chemotherapy-related myelosuppression events

but also decreases related hospitalization rates, blood transfusion

needs and the use of supportive therapies, thereby improving the

QoL of patients without diminishing the antitumor efficacy of

chemotherapy (18–20). Given its promising efficacy,

trilaciclib has the potential to improve the treatment landscape

for ES-SCLC, particularly in managing the adverse effects of

chemotherapy while maintaining treatment efficacy. Despite the

promising results observed in these trials, there is a need for

more research focusing on the real-world application and safety of

trilaciclib in diverse patient populations, especially in China,

where clinical practices and patient demographics may differ.

Real-world data will offer more generalizable insights and

potentially highlight challenges or benefits that controlled trials

may not fully capture.

Although trilaciclib has shown positive results in

several international clinical trials and has been applied in some

countries and regions, research on the real-world application and

safety of trilaciclib in Chinese patients with ES-SCLC remains

relatively limited. In addition, cultural and healthcare system

differences may affect the accessibility and outcomes of treatment,

highlighting the importance of evaluating trilaciclib's role in

different settings. Therefore, the present study aims to

retrospectively assess the myeloprotective effect, safety and

impact on survival outcomes of trilaciclib in first-line

chemotherapy for patients with ES-SCLC in China. The findings from

this study may help bridge the gap in understanding the clinical

efficacy of trilaciclib in a Chinese population and contribute to

evidence-based support for its use in the treatment of ES-SCLC.

Moreover, the present study aims to offer stronger support for

clinical decision-making by providing insights into its practical

applications and potential benefits in improving the treatment

outcomes and overall care of patients with ES-SCLC.

Materials and methods

General clinical information

The present study is a single-center, retrospective

real-world research project conducted at Chengde Central Hospital.

A total of 180 patients diagnosed with ES-SCLC between January 2020

and January 2024 were included based on the following inclusion

criteria. The medical records of the patients were accessed

specifically for the present study between January 2024 and

February 2025, including all relevant treatment and follow-up data,

with patient mortality or the end of follow-up as the endpoint. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients were histologically

or cytologically confirmed to have SCLC; ii) patients were

receiving platinum-based chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy;

iii) patients were aged ≥18 years; iv) patients with an Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2

(21); v) completion of at least

two cycles of treatment with complete treatment data; vi)

first-time diagnosis of ES-SCLC, or recurrent or metastatic disease

meeting the criteria for extensive stage; and vii) patients had not

received prior systemic therapy for SCLC. The exclusion criteria

were as follows: i) Patients who had been diagnosed with other

malignant tumors; ii) patients with severe heart, liver or kidney

dysfunction, or other major complications; iii) patients with poor

treatment compliance or incomplete clinical data; iv) patients with

severe active infections or other major medical diseases; v)

patients with missing data; and vi) patients who received other

antitumor therapies or participated in other clinical trials during

the study period. After excluding patients with missing data, the

remaining 180 patients were included for final analysis. All

patients underwent a comprehensive evaluation before treatment,

including physical examinations, blood tests, biochemical

indicators (liver and kidney function, electrolytes, blood glucose

levels, lipid profile, myocardial enzymes, amylase, alkaline

phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase), chest, abdominal and pelvic

computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans,

brain MRI or enhanced CT scans, and bone scans. Additionally,

baseline clinical data were recorded, including age, sex, smoking

history, ECOG performance status, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

(PD-L1) expression status, tumor staging, number of metastatic

sites and brain metastasis status. Patients were divided into two

groups based on the treatment regimen: The trilaciclib group and

the control group. The trilaciclib group and the control group each

included 90 patients. The study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Chengde Central Hospital (Chengde, China; approval no.

CDCHLL2023-407).

Treatment methods

Patients in the trilaciclib group received

trilaciclib in combination with chemotherapy and immunotherapy. The

chemotherapy regimen included EC (etoposide 100 mg/m2 on

days 1–3; carboplatin dosed according to an area under the curve of

5, corresponding to a dose of ~500 mg on day 1) or EP (etoposide

100 mg/m2 on days 1–3; cisplatin 75 mg/m2 on

day 1). The immunotherapy regimen included the following drugs: 71

Patients received surufilumab, 8 received tislelizumab (4.5

mg/m2 intravenously every 3 weeks), 6 received

toripalimab (240 mg intravenously every 3 weeks), 3 received

atezolizumab (1,200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks) and 2 received

durvalumab (1,500 mg intravenously every 3 weeks). Each treatment

cycle was 3 weeks, with a total of 4–6 cycles. After completing 4–6

cycles of chemotherapy, immunotherapy was continued as a

monotherapy until disease progression or intolerable toxicity

occurred. Trilaciclib was administered by intravenous infusion at a

dose of 240 mg/m2 on each day of chemotherapy (days 1–3

of the cycle), with administration completed 30 min prior to the

start of chemotherapy. For patients experiencing treatment delays

or dose adjustments, the dosage for subsequent chemotherapy cycles

was appropriately adjusted based on specific circumstances. After

disease progression, patients received second-line treatment,

primarily with topotecan or irinotecan, and some patients received

third-line treatment with paclitaxel or anlotinib.

Patients in the control group received the same

chemotherapy regimen as the trilaciclib group combined with

immunotherapy. The immunotherapy drugs included surufilumab (74

cases), tislelizumab (6 cases), toripalimab (6 cases), atezolizumab

(3 cases) and durvalumab (1 case), but without trilaciclib. The

second- and third-line treatment regimens after disease progression

were the same as those for the trilaciclib group, primarily

involving topotecan, irinotecan and in some cases, paclitaxel or

anlotinib.

Observation indicators

Adverse events were graded according to the Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 by the National

Cancer Institute (22,23). Treatment efficacy was evaluated

using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1

(24). The observation indicators

included myelosuppression-related indicators, chemotherapy dose

adjustment indicators, efficacy indicators, survival indicators and

safety indicators. The myelosuppression-related indicators

included: i) Incidence of grade 3 and 4 neutropenia (25); ii) duration of severe neutropenia

during the first cycle; iii) number of patients using G-CSF and the

average number of cycles of G-CSF use; iv) incidence of anemia

(≥grade 3) (26) and the lowest

hemoglobin level recorded for each patient during the study period;

v) number of patients requiring red blood cell transfusions and the

number of transfusion episodes; vi) incidence of thrombocytopenia

(≥grade 3) (27) and the lowest

platelet count recorded for each patient during the study period;

vii) number of patients requiring platelet transfusions and the

number of transfusion episodes; viii) incidence of febrile

neutropenia and the number of related hospitalizations; and ix)

number of patients hospitalized due to myelosuppression and the

number of hospitalization days. Chemotherapy dose adjustment

indicators included: i) Number of patients with chemotherapy cycle

delays, dose reductions and cycle interruptions; ii) number of

patients completing ≥4 chemotherapy cycles; and iii) the average

number of completed cycles. Efficacy indicators were as follows: i)

Objective response rate (ORR), including complete response (CR) and

partial response (PR); and ii) disease control rate, including CR,

PR and stable disease (SD). Survival indicators were

progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). OS is

defined as the time from the initiation of treatment to death from

any cause or the time of last follow-up. PFS is defined as the time

from the initiation of treatment to disease progression or death

from any cause. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to

evaluate potential factors affecting PFS and OS, including age,

sex, ECOG score, immunotherapy regimen, number of metastatic sites,

baseline brain metastasis, brain radiotherapy, chest radiotherapy,

chemotherapy regimen and PD-L1 expression status. Safety indicators

consisted of the incidence of drug-related adverse events during

treatment.

Follow-up

The follow-up methods in the present study included

regular outpatient visits, telephone follow-up and review of

medical records. The specific follow-up schedule was as follows:

Year 1, follow-up every 2 months; years 2–3, follow-up every 3–4

months; years 4–5, follow-up every 6 months; and >5 years,

annual follow-up. The follow-up content included medical history

inquiry, physical examination, laboratory tests and imaging

examinations (such as chest, abdominal and pelvic CT or MRI, brain

MRI or CT) to assess disease progression, treatment efficacy and

the occurrence of adverse events. During follow-up, the time of

disease progression, mortality and cause of death were recorded in

detail. The follow-up cut-off date was set as February 1, 2025,

with patient mortality or the end of follow-up as the endpoint.

Throughout the study, efforts were made to ensure the authenticity

and accuracy of follow-up data, with timely updates to the

follow-up database. Strict quality control and data verification

procedures were implemented, including regular audits of patient

data, cross-checking of medical records, validation of key clinical

outcomes, and verification of follow-up dates to ensure consistency

and accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis in the present study was performed

using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 27.0 statistical

software (IBM Corp.). For normally distributed continuous data,

values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and inter-group

comparisons were performed using the unpaired independent sample

t-test. For non-normally distributed continuous data, normality was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and values were expressed as

median (interquartile range), with inter-group comparisons

conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were

expressed as frequency (percentage), and inter-group comparisons

were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact

probability test. Survival data were analyzed using the

Kaplan-Meier method to estimate PFS and OS, and the median survival

time and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The

log-rank test was used to compare survival curves between groups,

with a two-tailed P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Additionally, Cox proportional hazards models were used for

multivariate analysis to identify factors influencing PFS and OS.

Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the independent

effects of clinical variables such as age, sex, ECOG performance

status and immunotherapy regimen on survival outcomes. The

corresponding hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI were calculated.

Variables were selected based on clinical significance and

univariate analysis results. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Propensity score matching

(PSM) was used to match patients between the trilaciclib group and

the control group based on clinical variables such as age, sex,

ECOG performance status, PD-L1 expression and the number of

metastatic sites. After matching, the balance between the two

groups was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with

all variables having SMD values of <0.1, indicating adequate

matching.

Results

Comparison of general clinical

data

There were no statistically significant differences

between the trilaciclib group and the control group in terms of

age, sex, smoking history, ECOG performance status, PD-L1

expression status, number of metastatic sites, baseline brain

metastasis and brain radiotherapy status (all P>0.05),

indicating that the baseline characteristics of the two groups were

well-matched and comparable, as shown in Table I. Brain metastasis is considered a

key controlled variable in this study due to its potential impact

on prognosis and treatment outcomes in patients with ES-SCLC. The

brain is a common site for metastasis in ES-SCLC, and its presence

may influence both the treatment approach and survival outcomes

(28).

| Table I.Comparison of general clinical data

between the trilaciclib group and the control group. |

Table I.

Comparison of general clinical data

between the trilaciclib group and the control group.

| Characteristic | Trilaciclib group,

N (%) | Control group, N

(%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

Median | 63.5 | 61.5 |

|

|

|

<65 | 52 (57.8) | 61 (67.8) |

|

|

|

≥65 | 38 (42.2) | 29 (32.2) | 1.926 | 0.165 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 43 (47.8) | 34 (37.8) |

|

|

|

Male | 47 (52.2) | 56 (62.2) | 1.838 | 0.175 |

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 68 (75.6) | 74 (82.2) |

|

|

| 1 | 22 (24.4) | 16 (17.8) | 1.201 | 0.273 |

| Smoking

history |

|

|

|

|

| Never

smoked | 14 (15.6) | 8 (8.9) |

|

|

| Former

smoker | 72 (80.0) | 75 (83.3) |

|

|

| Current

smoker | 4 (4.4) | 7 (7.8) | 2.516 | 0.284 |

| PD-L1

expression |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 71 (78.9) | 62 (68.9) |

|

|

|

Positive | 19 (21.1) | 28 (31.1) | 2.332 | 0.127 |

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 29 (32.2) | 18 (20.0) |

|

|

|

2-3 | 40 (44.4) | 53 (58.9) |

|

|

|

>3 | 21 (23.3) | 19 (21.1) | 0.639 | 0.726 |

| Baseline brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

| No | 74 (82.2) | 77 (85.6) |

|

|

|

Yes | 16 (17.8) | 13 (14.4) | 0.370 | 0.543 |

| Brain

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

| No | 75 (78.3) | 79 (85.0) |

|

|

|

Yes | 15 (21.7) | 9 (15.0) | 0.891 | 0.345 |

| Chest

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

| No | 63 (70.0) | 71 (78.9) |

|

|

|

Yes | 27 (30.0) | 19 (21.1) | 1.869 | 0.172 |

| Chemotherapy

regimen |

|

|

|

|

| EP | 47 (52.2) | 52 (57.8) |

|

|

| EC | 43 (47.8) | 38 (42.2) | 0.561 | 0.454 |

Comparison of myelosuppression

Compared with the control group, the trilaciclib

group had a significantly lower incidence of grade 3 (14.4 vs.

45.6%) and grade 4 neutropenia (3.3 vs. 20.0%)

(χ2=42.263; P<0.001). The duration of severe

neutropenia during the first cycle was significantly shorter in the

trilaciclib group [0 (0–1) days vs. 4 (2–6) days;

Z=−9.592; P<0.001]. The proportion of patients using G-CSF in

the trilaciclib group was also significantly lower (18.9 vs. 51.1%;

χ2=20.537), as was the average number of cycles of G-CSF

use (1.5±0.6 vs. 3.2±1.5; t=−10.681) (both P<0.001). In terms of

anemia, the incidence of grade ≥3 anemia in the trilaciclib group

was 15.6%, significantly lower than the control group at 30.0%

(χ2=5.338; P=0.021). The lowest hemoglobin value was

higher in the trilaciclib group (94±9 vs. 76±11 g/l; t=7.862;

P<0.001), and the number of patients requiring red blood cell

transfusions (18.9 vs. 43.3%; χ2=12.546; P=0.002) and

the number of transfusion episodes (1.0±0.6 vs. 2.0±0.8; t=−7.697;

P<0.001) were also significantly lower. For thrombocytopenia,

the incidence of grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia in the trilaciclib group

was 11.1%, significantly lower than the control group at 25.6%

(χ2=6.271; P=0.012). The lowest platelet count was

higher in the trilaciclib group (84±16×109 vs.

61±13×109/l; t=8.109; P<0.001), and the number of

patients requiring platelet transfusions (7.8 vs. 21.1%;

χ2=6.474; P=0.011) and the number of transfusion

episodes (1.0±0.4 vs. 1.9±0.6; t=−7.682; P<0.001) were

significantly reduced. Additionally, the incidence of febrile

neutropenia in the trilaciclib group was significantly lower than

in the control group (4.4 vs. 17.8%; χ2=8.100; P=0.004),

as was the number of hospitalizations due to febrile neutropenia

(3.3 vs. 15.6%; χ2=7.860; P=0.005). The number of

hospitalizations related to myelosuppression (7.8 vs. 21.1%;

χ2=6.474; P=0.011) and the number of hospitalization

days (4.2±0.9 vs. 8.2±2.7 days; t=−7.128; P<0.001) were also

significantly lower in the trilaciclib group. Regarding

chemotherapy dose adjustments, the trilaciclib group had

significantly lower rates of chemotherapy cycle delays (12.2 vs.

41.1%; χ2=19.205; P<0.001), dose reductions (15.6 vs.

37.8%; χ2=11.364; P<0.001) and cycle interruptions

(5.6 vs. 20.0%; χ2=8.424; P=0.004) compared with the

control group. The proportion of patients completing ≥4

chemotherapy cycles was higher in the trilaciclib group (91.1 vs.

75.6%; χ2=7.840; P=0.005), and the average number of

completed chemotherapy cycles was also higher (5.3±0.7 vs. 4.1±1.9;

t=6.274; P=0.037). Detailed data are shown in Table II.

| Table II.Comparison of myelosuppression

between the trilaciclib group and the control group. |

Table II.

Comparison of myelosuppression

between the trilaciclib group and the control group.

|

Myelosuppression-related indicators | Trilaciclib group,

N=90 | Control group,

N=90 |

χ2/T/Z | P-value |

|---|

| Neutropenia, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| Grade

3 | 13 (14.4) | 41 (45.6) |

|

|

| Grade

4 | 3 (3.3) | 18 (20.0) | 42.263 | <0.001 |

| Duration of severe

neutropenia, days (range) | 0 (0–1) | 4 (2–6) | −9.592 | <0.001 |

| G-CSF use |

|

|

|

|

| Number

of patients using G-CSF, n (%) | 17 (18.9) | 46 (51.1) | 20.537 | <0.001 |

| Average

number of cycles of G-CSF use | 1.5±0.6 | 3.2±1.5 | −10.681 | <0.001 |

| Anemia |

|

|

|

|

| Grade

≥3, n (%) | 14 (15.6) | 27 (30.0) | 5.338 | 0.021 |

| Lowest

hemoglobin value, g/l | 94±9 | 76±11 | 7.862 | <0.001 |

| Number

of patients requiring RBC transfusions, n (%) | 17 (18.9) | 39 (43.3) | 12.546 | 0.002 |

| Number

of RBC transfusion episodes (per person) | 1.0±0.6 | 2.0±0.8 | −7.697 | <0.001 |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

|

|

|

|

| Grade

≥3, n (%) | 10 (11.1) | 23 (25.6) | 6.271 | 0.012 |

| Lowest

platelet count, ×109/l | 84±16 | 61±13 | 8.109 | <0.001 |

| Number

of patients requiring platelet transfusions, n (%) | 7 (7.8) | 19 (21.1) | 6.474 | 0.011 |

| Number

of platelet transfusion episodes (per person) | 1.0±0.4 | 1.9±0.6 | −7.682 | <0.001 |

| FN |

|

|

|

|

|

Incidence of FN, n (%) | 4 (4.4) | 16 (17.8) | 8.100 | 0.004 |

| Number

of hospitalizations due to | 3 (3.3) | 14 (15.6) | 7.860 | 0.005 |

| FN, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Myelosuppression-related

hospitalizations |

|

|

|

|

| Number

of hospitalizations, n (%) | 7 (7.8) | 19 (21.1) | 6.474 | 0.011 |

|

Hospitalization days | 4.2±0.9 | 8.2±2.7 | −7.128 | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy dose

adjustments |

|

|

|

|

| Number

of patients with chemotherapy cycle delays, n (%) | 11 (12.2) | 37 (41.1) | 19.205 | <0.001 |

| Number

of patients with dose reductions, n (%) | 14 (15.6) | 34 (37.8) | 11.364 | <0.001 |

| Number

of patients with chemotherapy cycle interruptions, n (%) | 5 (5.6) | 18 (20.0) | 8.424 | 0.004 |

| Number

of patients completing ≥4 chemotherapy cycles, n (%) | 82 (91.1) | 68 (75.6) | 7.840 | 0.005 |

| Average

number of chemotherapy cycles completed (cycles) | 5.3±0.7 | 4.1±1.9 | 6.274 | 0.037 |

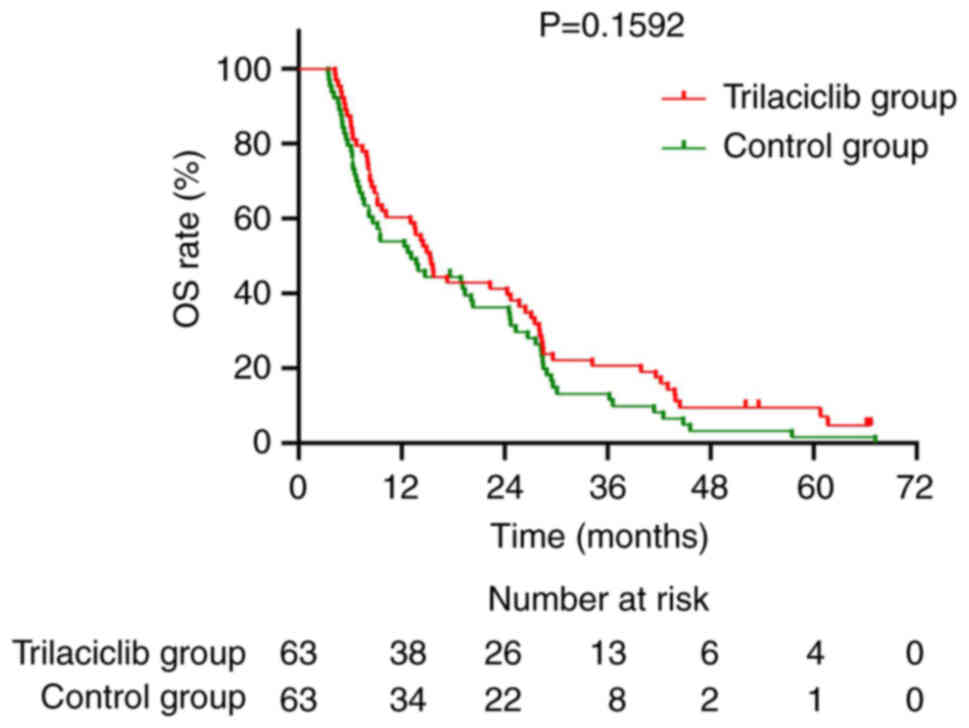

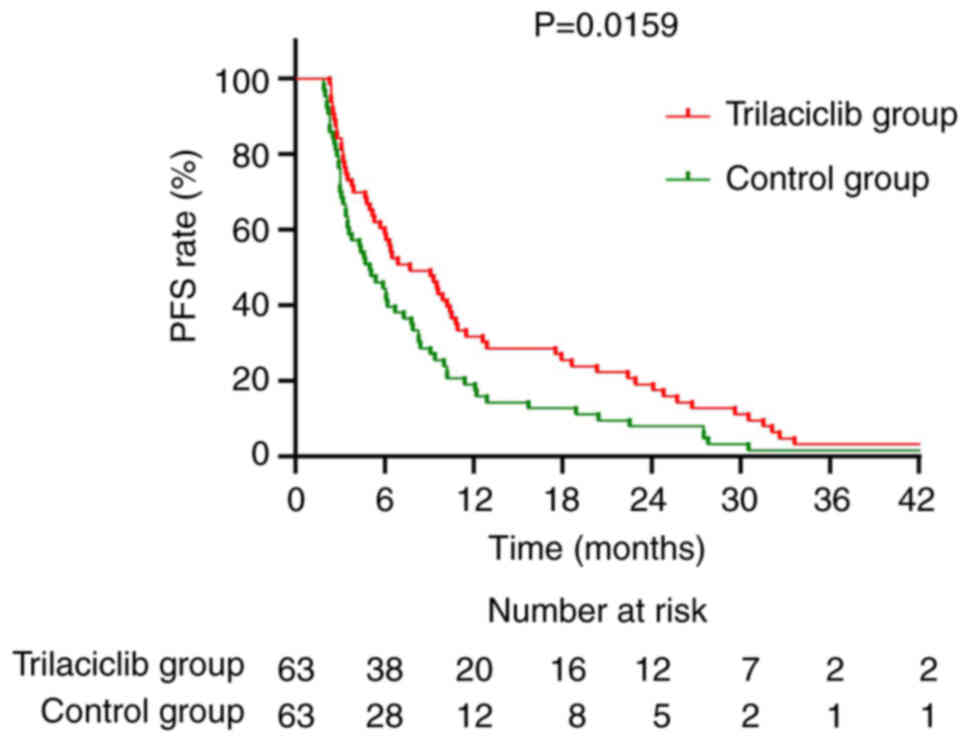

Survival analysis comparison

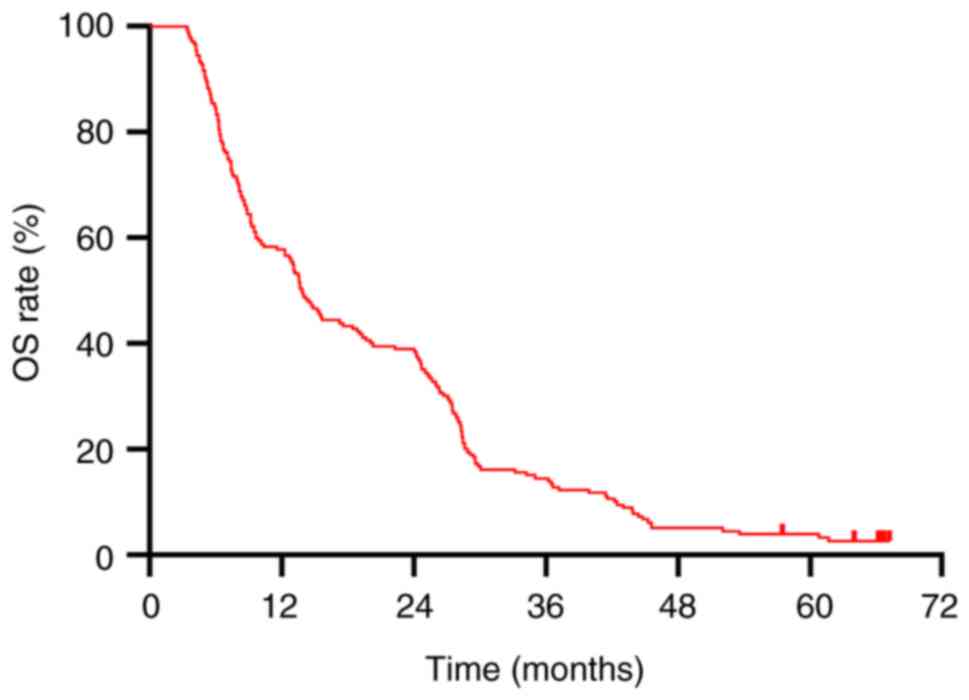

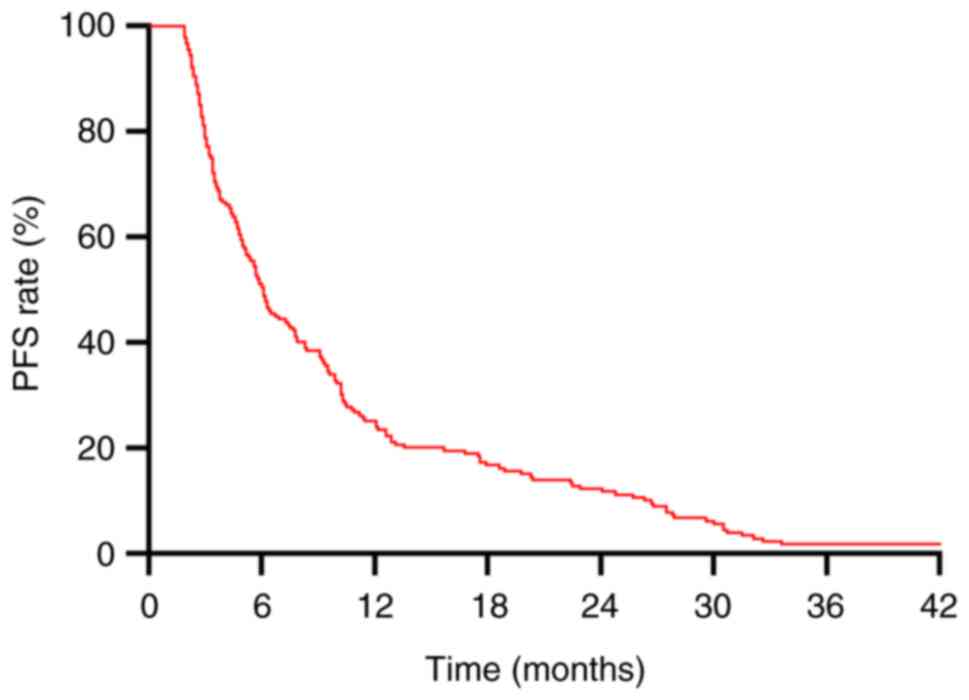

In the present study, the median OS for all patients

was 13.9 months (Fig. 1), and the

median PFS was 6.1 months (Fig. 2).

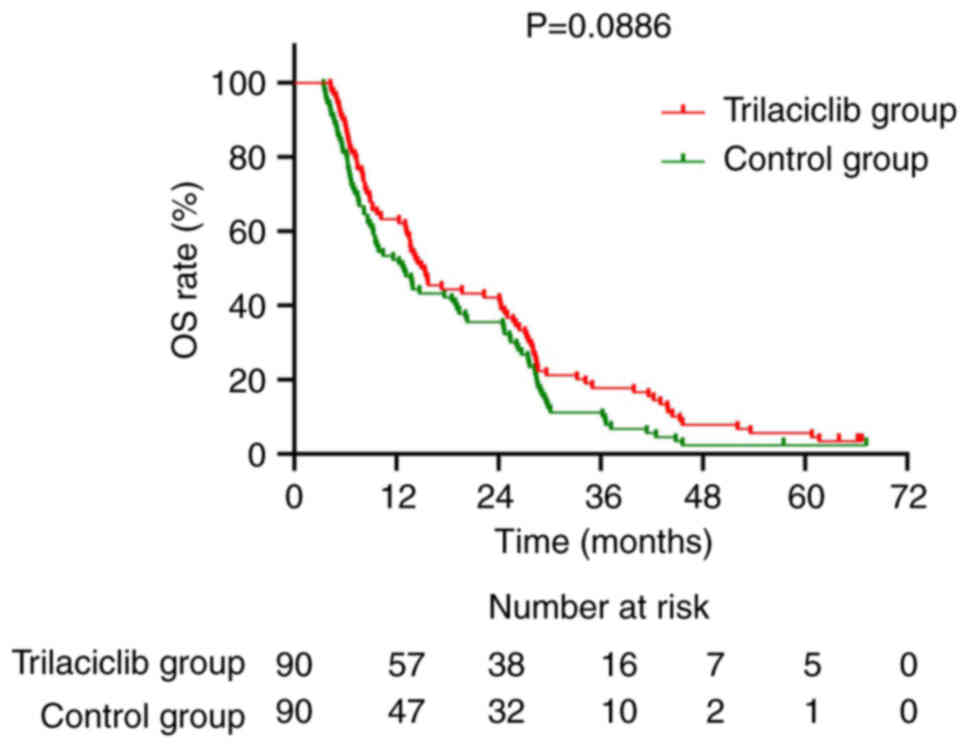

Group analysis showed that the median OS for the trilaciclib group

was 15.1 months, compared with 12.8 months for the control group.

Although the median OS in the trilaciclib group was 15.1 months

compared to 12.8 months in the control group, the difference was

not statistically significant (P=0.0886). The 1-, 2- and 3-year OS

rates for the trilaciclib group were 63.3, 42.2 and 17.8%,

respectively, while the rates for the control group were 52.2, 35.6

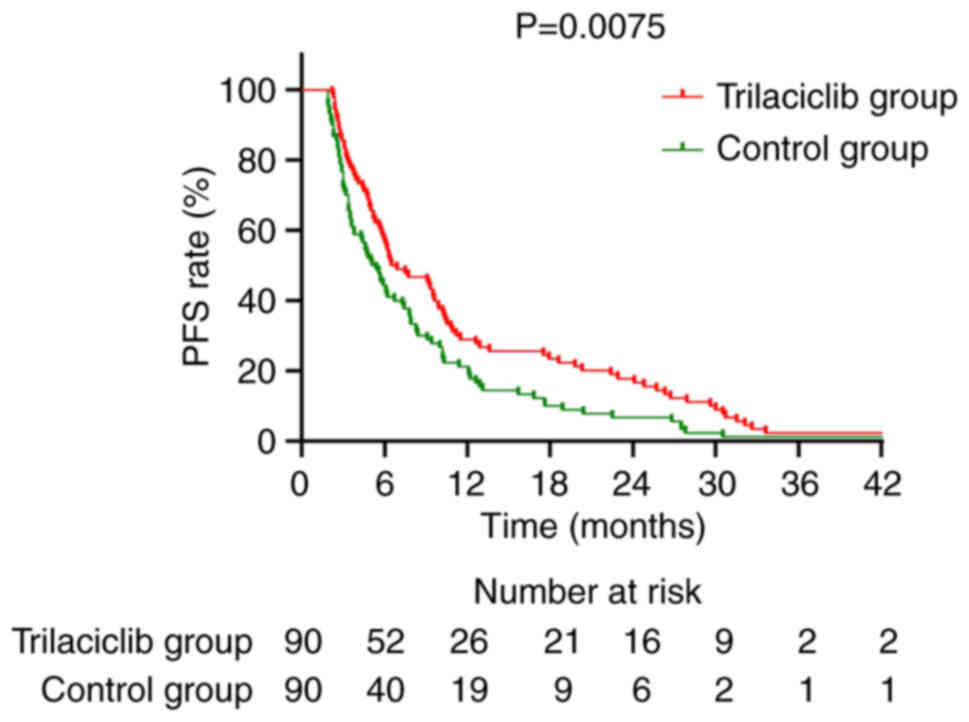

and 11.1% (Fig. 3). For PFS, the

median PFS for the trilaciclib group was 6.7 months, significantly

longer than the 5.3 months of the control group (HR=0.677; 95%

CI=0.502–0.912; P=0.0075). The 1-year PFS rate for the trilaciclib

group was 28.9% compared with 21.1% for the control group (Fig. 4).

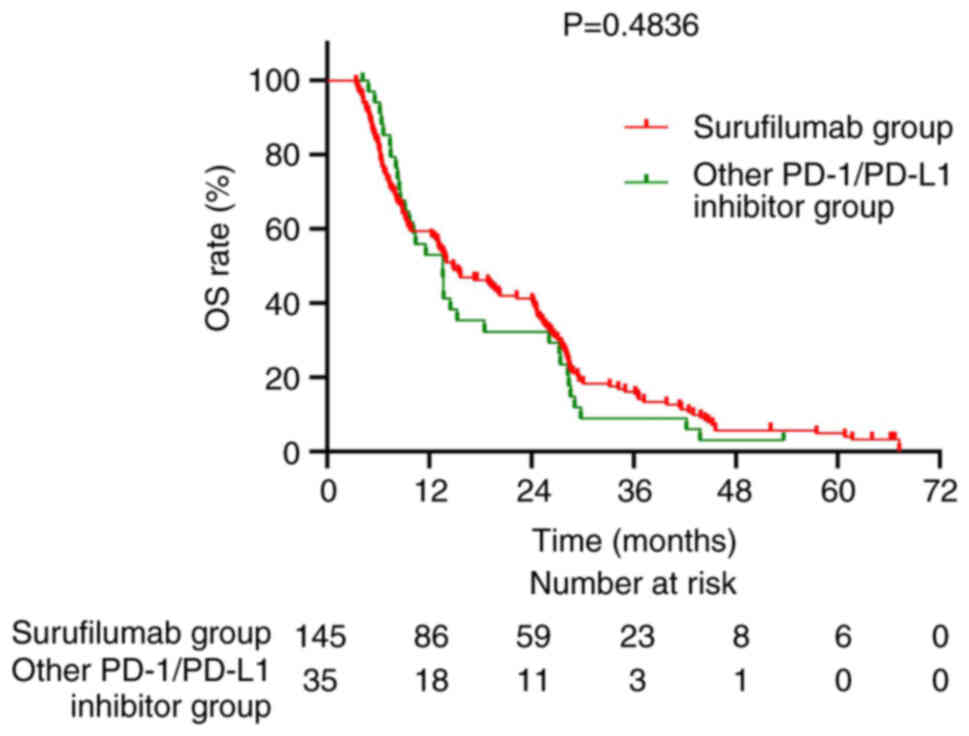

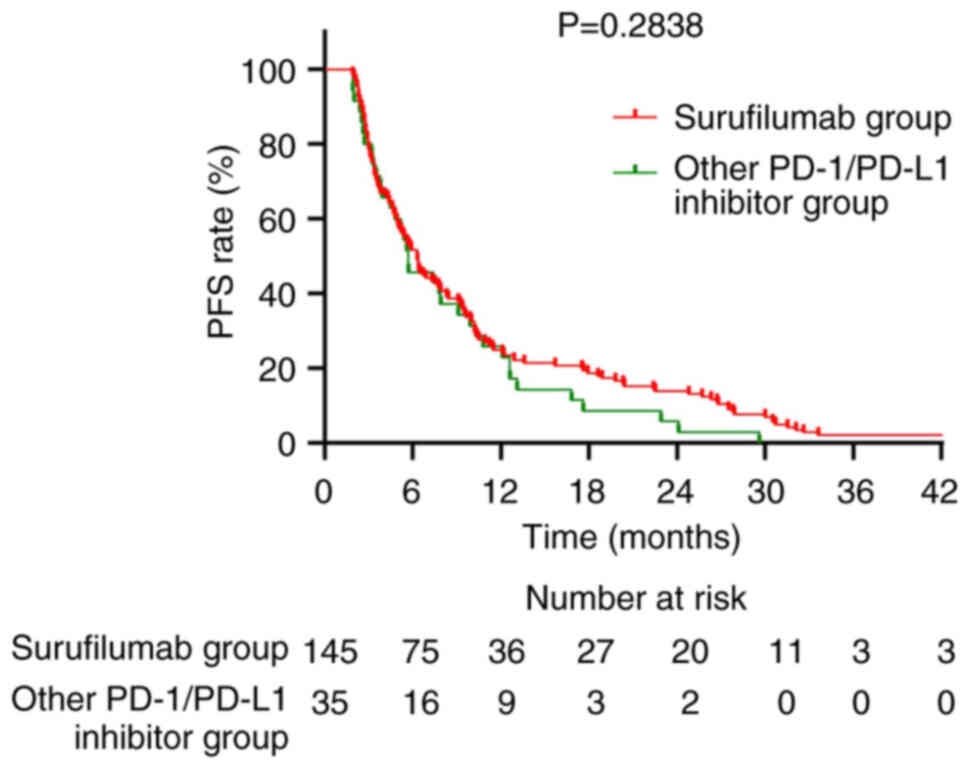

Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the

impact of different immunotherapeutic agents and chemotherapy

regimens on survival outcomes. Among patients receiving

immunotherapy, those treated with Surufilumab had a median OS of

14.8 months, compared with 13.6 months in those receiving other

programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 inhibitors (P=0.4836;

Fig. 5). The median PFS was 6.3

months in the Surufilumab group and 5.7 months in the PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors group (P=0.2838; Fig.

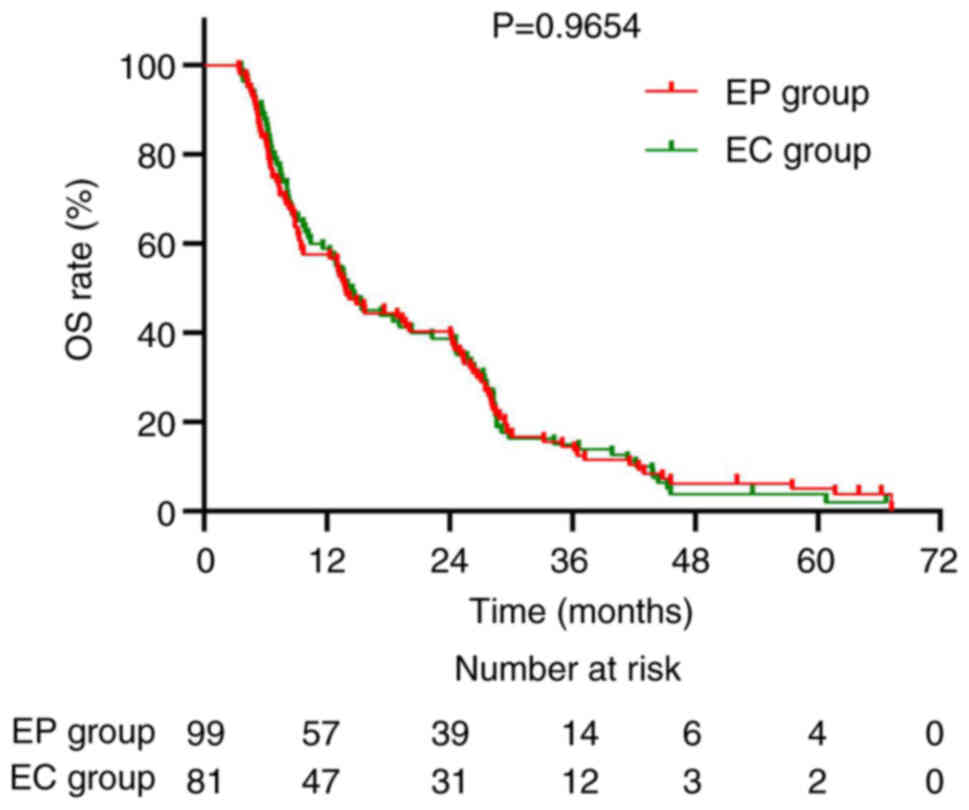

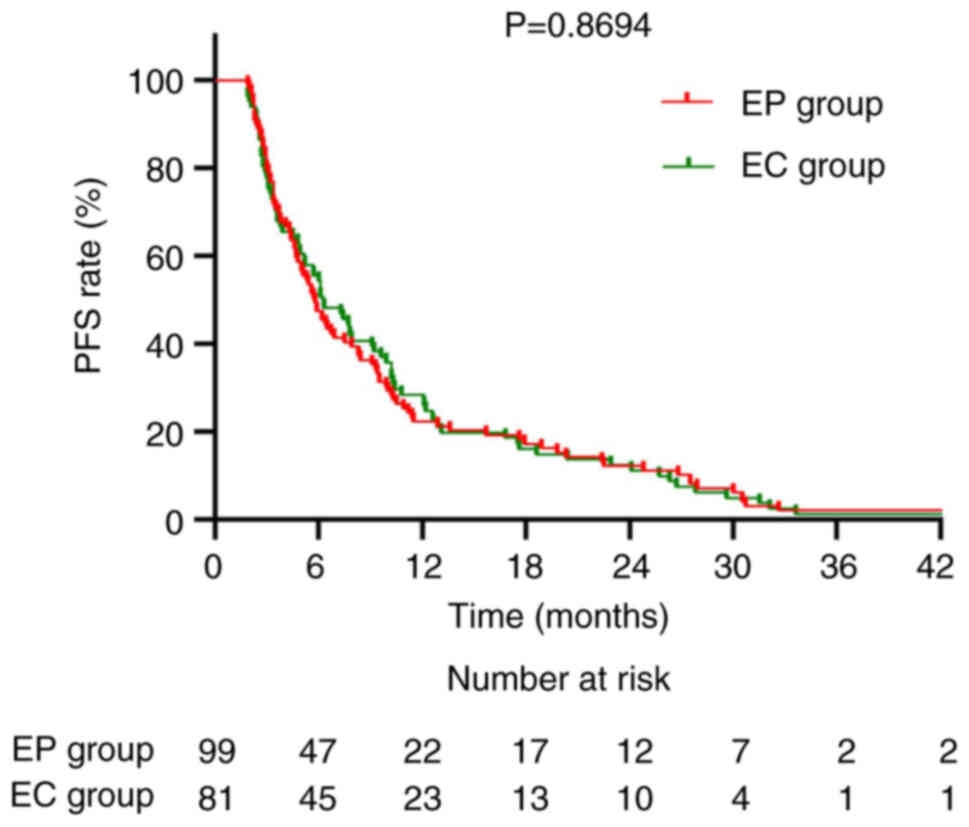

6). Regarding chemotherapy regimens, the median OS for the EP

group was 14.1 and 14.5 months for the EC group (P=0.9654; Fig. 7). The corresponding median PFS was

5.8 and 6.3 months, respectively (P=0.8694; Fig. 8).

PSM analysis

After performing PSM to balance key baseline

characteristics between the trilaciclib and control groups, each

group was reduced to 63 patients, resulting in 63 patients in the

trilaciclib group and 63 patients in the control group. Table III presents the baseline clinical

characteristics of the two groups after PSM, showing that the

groups were well-matched in terms of key clinical variables such as

age, ECOG performance status and number of metastatic sites. The

results of the survival analysis after PSM showed that the median

OS for the trilaciclib group was 15.3 months compared with 13.1

months for the control group, with no statistically significant

difference (P=0.1592; Fig. 9). By

contrast, the median PFS for the trilaciclib group was 7.7 months,

significantly longer than the 5.0 months of the control group

(P=0.0159), with a HR of 0.6558 (95% CI=0.4581–0.9388; Fig. 10).

| Table III.Baseline clinical characteristics of

the trilaciclib and control groups after propensity score

matching. |

Table III.

Baseline clinical characteristics of

the trilaciclib and control groups after propensity score

matching.

| Characteristic | Trilaciclib group,

n (%) | Control group, n

(%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

Median | 63.2 | 63.0 |

|

|

|

<65 | 36 (57.1) | 35 (55.6) |

|

|

|

≥65 | 27 (42.9) | 28 (44.4) | 0.032 | 0.857 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 29 (46.1) | 31 (49.2) |

|

|

|

Male | 34 (53.9) | 32 (50.8) | 0.127 | 0.721 |

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 48 (76.2) | 47 (74.6) |

|

|

| 1 | 15 (23.8) | 16 (25.4) | 0.043 | 0.836 |

| PD-L1

expression |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 51 (81.0) | 49 (77.8) |

|

|

|

Positive | 12 (19.0) | 14 (22.2) | 0.194 | 0.660 |

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 20 (31.7) | 19 (30.2) |

|

|

|

2-3 | 28 (44.4) | 27 (42.9) |

|

|

|

>3 | 15 (23.8) | 17 (27.0) | 0.169 | 0.919 |

| Baseline brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

| No | 54 (85.7) | 52 (82.5) |

|

|

|

Yes | 9 (14.3) | 11 (17.5) | 0.238 | 0.626 |

Analysis of factors affecting OS and

PFS

To further explore the independent predictive

factors influencing survival outcomes, Cox proportional hazards

model analyses were performed for both OS and PFS, with results

presented in Tables IV and

V. In the multivariate analysis for

OS, the ECOG performance status, number of metastatic sites and

baseline brain metastasis were identified as independent risk

factors. Compared with patients with an ECOG score of 0, those with

a score of 1 had a significantly increased risk of mortality

(HR=1.876; 95% CI=1.231–2.858; P=0.003). Compared with patients

with only one metastatic site, those with 2–3 metastatic sites had

a significantly higher risk of mortality (HR=2.194; 95%

CI=1.485–3.241; P<0.001), and the risk further increased for

patients with >3 metastatic sites (HR=7.066; 95%

CI=4.114–12.139; P<0.001). Patients with baseline brain

metastasis also had a significantly higher risk of death compared

with those without brain metastasis (HR=2.183; 95% CI=1.394–3.417;

P<0.001). For overall survival (OS), no statistically

significant difference was observed between the trilaciclib and

control groups (HR=1.306; 95% CI=0.965–1.766; P=0.083). Patients in

the control group had a 30.6% higher risk of mortality compared

with those receiving trilaciclib, based on the hazard ratio

(HR=1.306). This calculation was derived from comparing the hazard

ratio for OS between the two groups, but the difference did not

reach statistical significance (P=0.083). Treatment modality

(trilaciclib vs. control), type of immunotherapeutic agent

(surufilumab vs. others) and chemotherapy regimen (EP vs. EC) were

not independently associated with OS in the multivariate model (all

P>0.05) (Table IV).

| Table IV.Multivariate and univariate analysis

of factors affecting overall survival. |

Table IV.

Multivariate and univariate analysis

of factors affecting overall survival.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multifactorial

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<65 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65 | 1.090 | 0.800–1.486 | 0.584 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 1.102 | 0.814–1.491 | 0.529 |

|

|

|

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1 | 2.751 | 1.892–4.000 | <0.001 | 1.876 | 1.231–2.858 | 0.003 |

| PD-L1

expression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 1.061 | 0.755–1.491 | 0.733 |

|

|

|

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 1.000 |

| <0.001 | 1.000 |

| <0.001 |

|

2-3 | 2.473 | 1.689–3.620 | <0.001 | 2.194 | 1.485–3.241 | <0.001 |

|

>3 | 9.670 | 5.774–16.194 | <0.001 | 7.066 | 4.114–12.139 | <0.001 |

| Baseline brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 2.629 | 1.728–3.999 | <0.001 | 2.183 | 1.394–3.417 | <0.001 |

| Brain

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | 1.696 | 1.110–2.590 | 0.015 | 1.173 | 0.902–2.148 | 0.129 |

| Chest

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 1.267 | 0.898–1.788 | 0.177 |

|

|

|

| Chemotherapy

regimen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EC | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| EP | 1.047 | 0.774–1.416 | 0.765 | 1.101 | 0.809–1.500 | 0.540 |

| Immunotherapy

agent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Surufilumab | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Others | 1.165 | 0.823–1.534 | 0.498 | 1.141 | 0.837–1.598 | 0.452 |

| Treatment

modality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trilaciclib group | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| Control

group | 1.306 | 0.965–1.766 | 0.083 | 1.168 | 0.853–1.600 | 0.333 |

| Table V.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of factors affecting progression-free survival. |

Table V.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of factors affecting progression-free survival.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multifactorial

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<65 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65 | 1.197 | 0.882–1.624 | 0.248 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 1.068 | 0.792–1.438 | 0.667 |

|

|

|

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1 | 2.025 | 1.402–2.925 | <0.001 | 1.397 | 0.936–2.084 | 0.101 |

| PD-L1

expression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 1.038 | 0.741–1.455 | 0.828 |

|

|

|

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 1.000 |

| <0.001 | 1.000 |

| <0.001 |

|

2-3 | 1.633 | 1.140–2.339 | 0.007 | 1.508 | 1.045–2.176 | 0.028 |

|

>3 | 4.081 | 2.590–6.430 | <0.001 | 3.150 | 1.922–5.164 | <0.001 |

| Baseline brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 1.748 | 1.163–2.626 | 0.007 | 1.484 | 0.983–2.242 | 0.061 |

| Brain

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 1.404 | 0.924–2.134 | 0.112 |

|

|

|

| Chest

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 1.267 | 0.901–1.781 | 0.173 |

|

|

|

| Chemotherapy

regimen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EC | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| EP | 1.085 | 0.807–1.458 | 0.589 |

|

|

|

| Treatment

modality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trilaciclib group | 1.000 |

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| Control

group | 2.387 | 1.319–3.745 | <0.001 | 1.495 | 1.109–2.014 | 0.008 |

In the multivariate analysis for PFS, the treatment

modality and number of metastatic sites were identified as

independent factors affecting PFS. Compared with patients with only

one metastatic site, those with 2–3 metastatic sites had a

significantly increased risk of disease progression (HR=1.508; 95%

CI=1.045–2.176; P=0.028), and the risk further increased for

patients with >3 metastatic sites (HR=3.150; 95% CI=1.922–5.164;

P<0.001). Compared with the trilaciclib group, patients in the

control group had a significantly increased risk of disease

progression (HR=1.495; 95% CI=1.109–2.014; P=0.008), indicating

that trilaciclib independently reduced the risk of progression.

Although ECOG performance status and baseline brain metastasis

showed some trend of impact in the multivariate analysis for PFS,

they did not reach statistical significance (Table V).

Efficacy comparison

The efficacy assessment results after treatment

showed that in the trilaciclib group, the CR rate was 3.3%, the PR

rate was 83.3%, the SD rate was 11.1% and the PD rate was 2.2%. In

the control group, the CR rate was 2.2%, the PR rate was 73.3%, the

SD rate was 18.9% and the PD rate was 5.6%. The differences between

the two groups in terms of each efficacy category (CR, PR, SD and

PD) did not reach statistical significance (all P>0.05; Table VI). In terms of ORR (CR + PR), the

trilaciclib group had an ORR of 86.6%, higher than the 75.5%

observed in the control group. However, the difference between the

groups did not reach statistical significance (χ2=3.626;

P=0.057; data not shown).

| Table VI.Comparison of efficacy between the

trilaciclib group and the control group. |

Table VI.

Comparison of efficacy between the

trilaciclib group and the control group.

| Efficacy | Trilaciclib group,

N (%) | Control group, N

(%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| CR | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.2) |

|

|

| PR | 75 (83.3) | 66 (73.3) |

|

|

| SD | 10 (11.1) | 17 (18.9) |

|

|

| PD | 2 (2.2) | 5 (5.6) | 3.875 | 0.275 |

Discussion

ES-SCLC is an aggressive subtype of lung cancer with

an poor prognosis. At present, the standard of care primarily

comprises platinum-based doublet chemotherapy in combination with

immunotherapy (29). However, these

regimens are frequently associated with severe myelosuppression,

which significantly affects patients' treatment tolerance and QoL

(30). As a novel myeloprotective

agent, trilaciclib has shown promise in mitigating this issue in

clinical practice (31). The

present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first

real-world investigation conducted in a Chinese population to

comprehensively assess the myeloprotective effects, safety profile

and prognostic impact of trilaciclib in the first-line treatment of

ES-SCLC, offering important clinical insights and application

value.

The findings of the present study demonstrated that

trilaciclib, when combined with chemotherapy and immunotherapy,

significantly improved PFS, which aligns with previous clinical

trials involving trilaciclib. Notably, in a phase II randomized

trial conducted by Weiss et al (18), trilaciclib combined with EP

(etoposide + carboplatin) achieved a median PFS of 6.2 months in

ES-SCLC patients, consistent with the results of the present study

and reinforcing the beneficial effect of trilaciclib on PFS.

Another study confirmed that trilaciclib, in combination with

chemotherapy and atezolizumab, significantly reduced the incidence

of myelosuppression and improved QoL, with a notable improvement in

PFS but no significant advantage in OS (32). These findings are consistent with

the present study, in which PFS was significantly prolonged while

OS did not reach statistical significance.

In terms of response, the ORR in the trilaciclib

group was slightly higher than in the control group; however,

differences in CR, PR, SD and PD rates between the groups were not

statistically significant, in line with previous clinical studies

(17,33). Weiss et al (18) also reported that although

trilaciclib improved chemotherapy tolerability, it did not

significantly increase ORRs. The present study also found clear

myeloprotective effects of trilaciclib, including significant

reductions in severe neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, G-CSF

use and transfusion requirements. These findings are consistent

with those reported by Daniel et al (32), who demonstrated that trilaciclib

significantly reduced the incidence of chemotherapy-induced

myelosuppression in clinical settings. By enabling patients to

maintain scheduled chemotherapy doses and cycles, trilaciclib may

further translate into improved treatment outcomes and QoL, which

is one of its key clinical advantages.

Although the trilaciclib group showed a modest

improvement in median OS compared with the control group, the

difference was not statistically significant. This is similar to

the findings by Daniel et al (32), which showed that trilaciclib could

mitigate myelosuppression and maintain antitumor efficacy without

significantly prolonging OS. Possible reasons for this include

limited follow-up duration, relatively small sample size and

differences in post-progression treatment strategies. In fact,

second- and third-line treatment choices can substantially

influence overall survival outcomes. A recent study involving

benmelstobart, anlotinib and chemotherapy further demonstrated that

combining multi-targeted anti-angiogenic agents, such as anlotinib

and bevacizumab, with immunotherapy significantly improved OS (up

to 19.3 months), clearly outperforming the current standard

chemoimmunotherapy alone (34).

These findings suggest that trilaciclib could potentially be

explored in combination with other antitumor agents to further

enhance survival benefits. However, the potential influence of

heterogeneity in immunotherapeutic agents and chemotherapy regimens

on survival outcomes should be considered.

In the present subgroup analyses, surufilumab

demonstrated longer OS and PFS compared with other PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors, although the differences were not statistically

significant. Similarly, no significant differences in OS or PFS

were observed between patients receiving EP vs. EC regimens. These

findings indicate that the observed clinical benefit of trilaciclib

is unlikely to be confounded by the type of immunotherapy or

chemotherapy regimen used, thereby supporting the robustness of the

primary results. To elucidate the prognostic value of trilaciclib,

multivariate Cox regression analysis was conducted. The results

showed that, compared with patients treated with trilaciclib, those

in the control group had a significantly increased risk of disease

progression (HR=1.495; 95% CI=1.109–2.014; P=0.008), indicating an

independent protective effect of trilaciclib on PFS. No

statistically significant difference in OS was observed between the

trilaciclib and control groups (HR=1.306; 95% CI=0.965–1.766;

P=0.083). Further analysis showed that ECOG performance status,

number of metastatic sites and baseline brain metastasis were

independent poor prognostic factors for OS, which aligns with the

results of other studies (35,36).

This highlights the importance of considering these variables in

treatment planning. The impact of immunotherapy type and

chemotherapy regimen on survival did not show statistically

significant differences in the present model, emphasizing the

robust effect of trilaciclib. This suggests that even after

controlling for confounding variables such as ECOG performance

status, number of metastatic sites and presence of brain

metastases, trilaciclib independently contributed to delayed

disease progression. The novelty of the present study lies in its

being, to the best of our knowledge, the first real-world clinical

investigation of trilaciclib in a Chinese ES-SCLC population. It

provides an objective and comprehensive evaluation of the

myeloprotective efficacy, antitumor performance and safety profile

of trilaciclib. Unlike prior randomized controlled trials, the

present real-world study reflects the complexity of routine

clinical practice, involves a broader patient population and yields

findings that are more generalizable to actual treatment settings.

The present results offer important evidence-based support for

clinicians and demonstrate strong clinical applicability and value

for broader implementation.

Nonetheless, the present study has several

limitations. First, as a retrospective, non-randomized study,

selection bias could not be fully eliminated. To mitigate this

limitation, PSM was employed to match patients in the trilaciclib

and control groups based on baseline characteristics such as age,

ECOG performance status and number of metastatic sites. While PSM

helped reduce baseline imbalances between the groups, it is

important to note that residual confounding variables may still

exist. Second, the relatively small sample size limited the

statistical power for subgroup analyses, potentially affecting the

robustness and generalizability of certain findings. Third, the

follow-up duration was limited and long-term survival data for some

patients are still being collected, which may underestimate or

overestimate the true OS difference. Fourth, the lack of blinding

in the study could have introduced subjectivity in efficacy and

safety assessments. Future prospective, randomized, controlled

trials are required to further validate the efficacy and safety of

trilaciclib across different patient populations.

In summary, the present real-world study supported

the myeloprotective role of trilaciclib in first-line treatment of

ES-SCLC. Trilaciclib effectively reduced chemotherapy-induced

myelosuppression, improved treatment compliance and prolonged PFS,

thereby enhancing overall treatment safety without compromising

antitumor efficacy. Although a statistically significant OS benefit

was not demonstrated, trilaciclib exhibited promising clinical

potential, particularly in preserving QoL by reducing

chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. The reduction in severe

neutropenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia in the trilaciclib group

not only improved treatment tolerance but also contributed to

improved patient outcomes in terms of QoL. While OS did not show

significant improvement, these myeloprotective effects are

clinically meaningful, as they may lead to fewer treatment delays,

reduced hospitalization and improved overall treatment compliance.

Further large-scale, long-term prospective studies are warranted to

clarify role of trilaciclib in SCLC management and identify the

populations most likely to benefit.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Science and Technology

Program of Chengde (grant no. 202301A016).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC performed the data analysis and wrote the paper.

LW was responsible for the research design and guided the revision

of the paper. HZ provided clinical cases, participated in data

analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript critically

for important intellectual content. XL contributed to the research

design, provided data collection support and assisted in drafting

the manuscript. YC and LW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The current study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics

Committee of Chengde Central Hospital (Chengde, P.R. China;

approval no. CDCHLL2023-407). All patients and/or their families

signed informed consent forms for study participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ES-SCLC

|

extensive-stage small cell lung

cancer

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

CR

|

complete response

|

|

PR

|

partial response

|

|

SD

|

stable disease

|

|

PD

|

progressive disease

|

|

G-CSF

|

granulocyte colony-stimulating

factor

|

|

ECOG

|

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

EP

|

etoposide plus cisplatin

|

|

EC

|

etoposide plus carboplatin

|

References

|

1

|

Megyesfalvi Z, Gay CM, Popper H, Pirker R,

Ostoros G, Heeke S, Lang C, Hoetzenecker K, Schwendenwein A,

Boettiger K, et al: Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer:

Tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA

Cancer J Clin. 73:620–652. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang Q, Gümüş ZH, Colarossi C, Memeo L,

Wang X, Kong CY and Boffetta P: SCLC: Epidemiology, risk factors,

genetic susceptibility, molecular pathology, screening, and early

detection. J Thorac Oncol. 18:31–46. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Schwendenwein A, Megyesfalvi Z, Barany N,

Valko Z, Bugyik E, Lang C, Ferencz B, Paku S, Lantos A, Fillinger

J, et al: Molecular profiles of small cell lung cancer subtypes:

Therapeutic implications. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 20:470–483. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang S, Tang J, Sun T, Zheng X, Li J, Sun

H, Zhou X, Zhou C, Zhang H, Cheng Z, et al: Survival changes in

patients with small cell lung cancer and disparities between

different sexes, socioeconomic statuses and ages. Sci Rep.

7:13392017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Spigel DR, Townley PM, Waterhouse DM, Fang

L, Adiguzel I, Huang JE, Karlin DA, Faoro L, Scappaticci FA and

Socinski MA: Randomized phase II study of bevacizumab in

combination with chemotherapy in previously untreated

extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: Results from the SALUTE

trial. J Clin Onco. 29:2215–2222. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gomez-Randulfe I, Leporati R, Gupta B, Liu

S and Califano R: Recent advances and future strategies in

first-line treatment of ES-SCLC. Eur J Cancer. 200:1135812024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang W, Wu G, Luo W, Lin L, Zhou C, Yao G,

Chen M, Wu X, Chen Z, Ye J, et al: Anlotinib plus oral

fluoropyrimidine S-1 in refractory or relapsed small-cell lung

cancer (SALTER TRIAL): A multicenter, single-arm, phase II trial.

BMC Cancer. 24:11822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Herzog BH, Devarakonda S and Govindan R:

Overcoming chemotherapy resistance in SCLC. J Thorac Oncol.

16:2002–2015. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gajra A, Reeves P, O'Brien S, Carey A,

Moore M and Huang H: HSR25-156: Myelosuppression and healthcare

resource utilization in community oncology patients with

limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC) receiving first-line

therapy with or without trilaciclib. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

23:HSR25–HSR156. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Povsic M, Enstone A, Wyn R, Kornalska K,

Penrod JR and Yuan Y: Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of

small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) treatments: A systematic literature

review (SLR). PLoS One. 14:e02196222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Epstein RS, Aapro MS, Basu Roy UK, Salimi

T, Krenitsky J, Leone-Perkins ML, Girman C, Schlusser C and

Crawford J: Patient burden and real-world management of

chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression: Results from an online

survey of patients with solid tumors. Adv Ther. 37:3606–3618. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Adams JR, Lyman GH, Djubegovic B,

Feinglass J and Bennett CL: G-CSF as prophylaxis of febrile

neutropenia in SCLC. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 3:1273–1281. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dhillon S: Trilaciclib: First approval.

Drugs. 81:867–874. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lai AY, Sorrentino JA, Dragnev KH, Weiss

JM, Owonikoko TK, Rytlewski JA, Hood J, Yang Z, Malik RK, Strum JC

and Roberts PJ: CDK4/6 inhibition enhances antitumor efficacy of

chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in

preclinical models and enhances T-cell activation in patients with

SCLC receiving chemotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0008472020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Goldschmidt J, Hart L, Scott J, Boykin K,

Bailey R, Heritage T, Lopez-Gonzalez L, Zhou ZY, Edwards ML,

Monnette A, et al: Real-world outcomes of trilaciclib among

patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer receiving

chemotherapy. Adv Ther. 40:4189–4215. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Qiu J, Sheng D, Lin F, Jiang P and Shi N:

The efficacy and safety of Trilaciclib in preventing

chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol.

14:11572512023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Weiss JM, Csoszi T, Maglakelidze M, Hoyer

RJ, Beck JT, Domine Gomez M, Lowczak A, Aljumaily R, Rocha Lima CM,

Boccia RV, et al: Myelopreservation with the CDK4/6 inhibitor

trilaciclib in patients with small-cell lung cancer receiving

first-line chemotherapy: A phase Ib/randomized phase II trial. Ann

Oncol. 30:1613–1621. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cheng Y, Wu L, Huang D, Wang Q, Fan Y,

Zhang X, Fan H, Yao W, Liu B, Yu G, et al: Myeloprotection with

trilaciclib in Chinese patients with extensive-stage small cell

lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: Results from a randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study (TRACES). Lung

Cancer. 188:1074552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ferrarotto R, Anderson I, Medgyasszay B,

García-Campelo MR, Edenfield W, Feinstein TM, Johnson JM, Kalmadi

S, Lammers PE, Sanchez-Hernandez A, et al: Trilaciclib prior to

chemotherapy reduces the usage of supportive care interventions for

chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression in patients with small cell

lung cancer: Pooled analysis of three randomized phase 2 trials.

Cancer Med. 10:5748–5756. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sok M, Zavrl M, Greif B and Srpčič M:

Objective assessment of WHO/ECOG performance status. Support Care

Cancer. 10:3793–3798. 2019.

|

|

22

|

Atkinson TM, Ryan SJ, Bennett AV, Stover

AM, Saracino RM, Rogak LJ, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, Li Y and Basch

E: The association between clinician-based common terminology

criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) and patient-reported outcomes

(PRO): A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 24:3669–3676.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Trask PC, Dueck AC, Piault E and Campbell

A: Patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology

criteria for adverse events: Methods for item selection in

industry-sponsored oncology clinical trials. Clin Trials.

15:616–623. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford

R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, Shankar L, Bogaerts J, Chen A, Dancey J,

et al: RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: From the RECIST

committee. Eur J Cancer. 62:132–137. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, Dal Lago

L, Donnelly JP, Kearney N, Lyman GH, Pettengell R, Tjan-Heijnen VC,

Walewski J, et al: 2010 Update of EORTC guidelines for the use of

granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of

chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with

lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer.

47:8–32. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huang Y, Su C, Jiang H, Liu F, Yu Q and

Zhou S: The association between pretreatment anemia and overall

survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective

cohort study using propensity score matching. J Cancer. 13:51–61.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xie W, Hu N and Cao L: Immune

thrombocytopenia induced by immune checkpoint inhibitrs in lung

cancer: Case report and literature review. Front Immunol.

12:7900512021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Shan Q, Shi J, Wang X, Guo J, Han X, Wang

Z and Wang H: A new nomogram and risk classification system for

predicting survival in small cell lung cancer patients diagnosed

with brain metastasis: A large population-based study. BMC Cancer.

21:6402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Reck M, Mok TSK, Mansfield A, De Boer R,

Losonczy G, Sugawara S, Dziadziuszko R, Krzakowski M, Smolin A,

Hochmair M, et al: Brief report: Exploratory analysis of

maintenance therapy in patients with extensive-stage SCLC treated

first line with atezolizumab plus carboplatin and etoposide. J

Thorac Oncol. 17:1122–1129. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Li Y, Bao Y, Zheng H, Qin Y and Hua B: A

nomogram for predicting severe myelosuppression in small cell lung

cancer patients following the first-line chemotherapy. Sci Rep.

13:174642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dai HR, Yang Y, Wang CY, Chen YT, Cui YF,

Li PJ, Chen J, Yang C and Jiao Z: Trilaciclib dosage in Chinese

patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A pooled

pharmacometrics analysis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 45:2212–2225. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Daniel D, Kuchava V, Bondarenko I,

Ivashchuk O, Reddy S, Jaal J, Kudaba I, Hart L, Matitashvili A,

Pritchett Y, et al: Trilaciclib prior to chemotherapy and

atezolizumab in patients with newly diagnosed extensive-stage small

cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled phase II trial. Int J Cancer. 148:2557–2570.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu Y, Wu L, Huang D, Wang Q, Yang C, Zhou

L, Sun S, Jiang X and Cheng Y: Effect of trilaciclib administered

before chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage small-cell

lung cancer: A pooled analysis of four randomized studies. Cancer

Treat Res Commun. 42:1008692024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cheng Y, Chen J, Zhang W, Xie C, Hu Q,

Zhou N, Huang C, Wei S, Sun H, Li X, et al: Benmelstobart,

anlotinib and chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung

cancer: A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 30:2967–2976. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Bianco A, Perrotta F, Barra G, Malapelle

U, Rocco D and De Palma R: Prognostic factors and biomarkers of

responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:49312019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Liu J, Cao Y, Shao T and Wang Y: Exploring

the prognostic impact of differences in treatment strategies for

SCLC with different histologies and prognostic factors for C-SCLC:

A SEER population-based study. Heliyon. 10:e329072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|