Lung cancer is the most common malignancy worldwide

in terms of incidence and is also the leading cause of

cancer-related death (1), with

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for ~89% of all lung

cancer cases (2). Although

chemoradiotherapy and targeted therapy have improved survival,

patients with NSCLC ultimately develop resistance to these

treatment regimens (3). Metastatic

lung cancer is considered incurable (4); therefore, understanding the signal

transduction pathways that drive lung cancer progression and

metastasis is essential for developing effective treatment

strategies. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has a key role in embryonic

development and tissue homeostasis (5). Abnormal activation of this pathway,

which is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, has been

observed in breast, prostate, gastrointestinal and lung cancer

(6–9). The β-catenin protein is a central

component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and plays a

critical role in maintaining cell-cell adhesion (10). Abnormal β-catenin expression

promotes the proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance of NSCLC

cells (11). The present review

examines the role of β-catenin protein in epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) and the tumor microenvironment (TME), discusses

the mechanisms regulating its nuclear translocation and its

contribution to the resistance against EGFR-tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs) and explores its potential (alongside that of its

coding gene) as a prognostic biomarker.

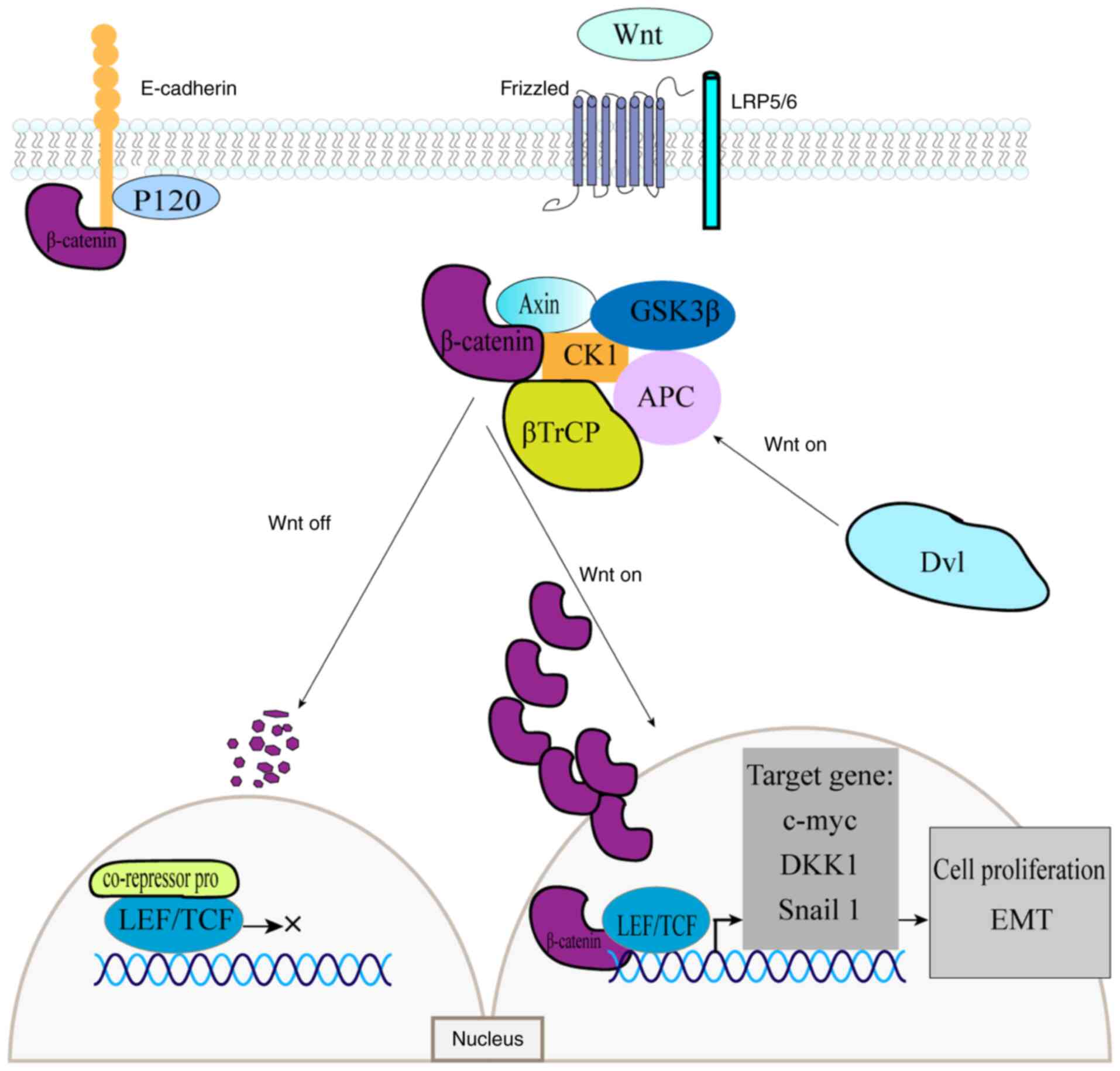

The Wnt signaling pathway is a highly conserved

pathway that is notably comparable in humans and insects; it plays

a crucial role in regulating cell growth, division and

carcinogenesis (12). The Wnt

protein family comprises cysteine-rich secreted glycoproteins that

are widely distributed in both vertebrates and invertebrates

(13). These proteins bind to the

extracellular domains of Frizzled receptors (14). Based on its dependence on β-catenin,

the Wnt signaling pathway is classified into two types: canonical

and non-canonical (15,16).

The canonical pathway plays a critical role in cell

division and proliferation, making it an important biological

target for cancer treatment (12).

The β-catenin protein, a key intracellular signaling molecule,

participates at every stage of this process (5). The adenomatous polyposis coli

(APC)-Axin-GSK-3β-casein kinase-1 (CK1) complex, which comprises

APC, Axin, CK1, protein phosphatase 2A and GSK-3β, facilitates

β-catenin degradation (17). This

canonical pathway functions in two states depending on the presence

or absence of the Wnt ligand. In the absence of Wnt, β-catenin

binds to the destruction complex, where phosphorylation of its

N-terminal serine or threonine residues triggers ubiquitination and

subsequent proteasomal degradation (17). In the absence of nuclear β-catenin

protein accumulation, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

(TCF/LEF) transcription factors remain bound to corepressor

proteins, thereby inhibiting transcription (18,19).

Wnt ligands can bind to Frizzled receptors and, with the

co-receptor assistance of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related

proteins 5/6 (LRP5/6), activate the cytoplasmic Dishevelled (Dvl)

protein (20,21). Ligand-receptor binding also

activates protein kinases (PKA, PKB and PKC), as well as the PI3K

and MAPK signaling pathways, which inhibit GSK-3β phosphorylation.

Concurrently, Dvl inactivates the destruction complex, thereby

preventing β-catenin phosphorylation and subsequent degradation

(22). As β-catenin accumulates in

the cytoplasm, it translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to

TCF/LEF transcription factors. This interaction activates the

transcription of Wnt target genes, including c-MYC, Cyclin

D1 gene (CCND1) and Dickkopf-1, which regulate cell growth

and development (23) (Fig. 1).

Non-canonical Wnt pathways regulate downstream

effects through alternative signaling molecules. Key pathways

include the Wnt/planar cell polarity (24), Wnt/Ras-related protein 1 signaling

(25), Wnt/PKA (26), Wnt/PKC (27) and Wnt/Ca2+ (28) pathways. These pathways exhibit

overlapping activities and are not entirely independent.

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a central role in

the initiation and progression of lung cancer; it regulates stem

cell renewal, migration, apoptosis and proliferation (29). Cancer development is associated with

aberrant Wnt signaling, particularly abnormal activation of the

canonical pathway driven by elevated β-catenin levels (30). Kren et al (31) reported that β-catenin protein

expression is correlated with tumor grade, stage and size, with 71%

of NSCLC cases showing upregulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm

and plasma membrane.

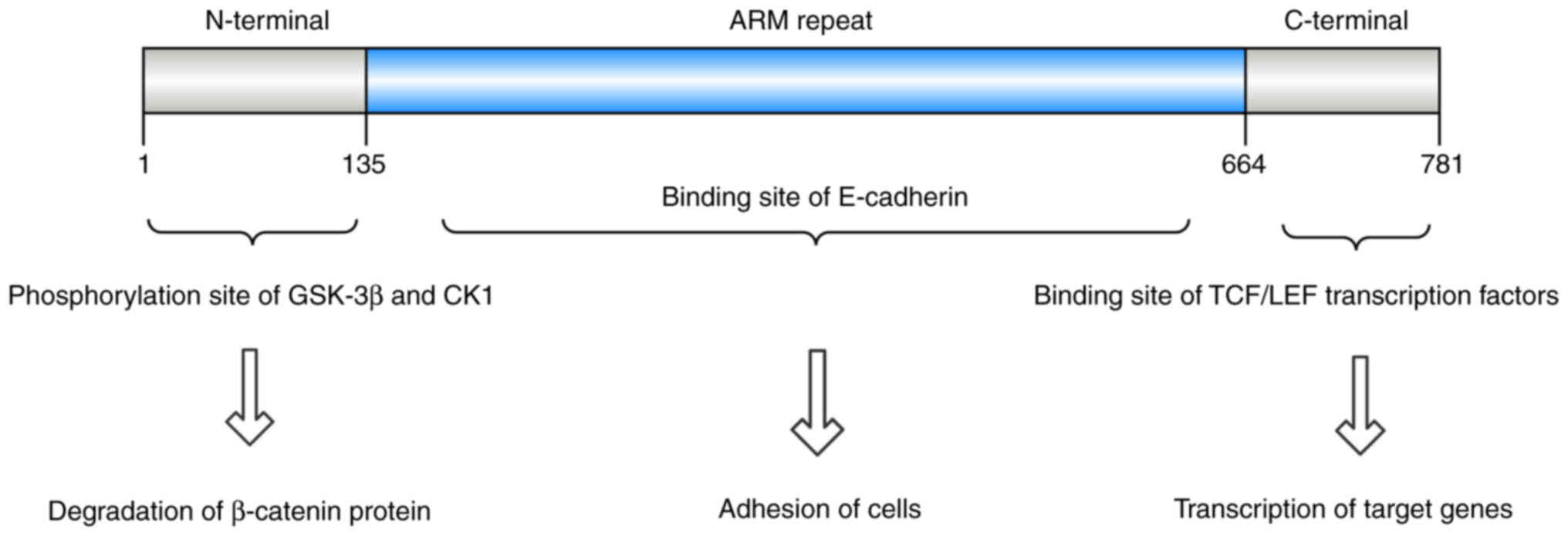

Structurally, β-catenin comprises three primary

domains: A central armadillo (ARM) repeat region of ~550 amino

acids, an N-terminal domain of 150 amino acids and a C-terminal

domain containing 100 amino acids (32,33).

The N-terminal domain is the site of phosphorylation by GSK-3β and

CK1, whereas the C-terminal domain interacts with nuclear TCF/LEF

transcription factors. On the cell membrane, β-catenin forms a

complex through ARM domain binding to E-cadherin (34–36)

(Fig. 2).

Nuclear translocation of β-catenin is essential for

initiating the expression of proliferation-related genes (49). Theoretically, sufficient production

of stable β-catenin protein enables its entry into the cell

nucleus, where it can activate proliferative programs (50). This nuclear transport is not a

process of simple free diffusion but is instead governed by precise

and complex regulatory mechanisms (50).

Cytoplasmic regulatory mechanisms play a crucial

role in determining the stability and accumulation of the β-catenin

protein, which is essential for its nuclear transport (23). In normal cells, β-catenin is

primarily localized at the cell membrane and is degraded in the

cytoplasm by the destruction complex (17). Mutations in the CTNNB1 gene

impair β-catenin phosphorylation and ubiquitination, resulting in

its cytoplasmic accumulation (51).

Additionally, various factors can increase cytoplasmic β-catenin

levels through upregulation of CTNNB1 transcription. For

example, FLVCR1-AS1 and LINC01006 are associated with high levels

of CTNNB1 mRNA in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) cells, thereby

promoting the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway (52–54).

The transcription of CTNNB1 is regulated by eIF3a and WD

repeat and SOCS box-containing protein 2 (53,55),

while cold-inducible RNA-binding protein binds to CTNNB1

mRNA to modulate its expression (56). In addition, cytoplasmic β-catenin

protein is regulated by the destruction complex, which, as

aforementioned, consists of GSK-3β, APC, Axin and CK1. Aquaporin-3

(57), microRNA (miR)-1246

(58) and long non-coding RNA

(IncRNA) PHLDA3 (59) downregulate

GSK-3β expression at the transcriptional, translational and protein

levels, respectively, thereby disrupting the function of the

destruction complex. Zbed3 (60)

and IncRNA DLX6-AS1 (61)

downregulate Axin expression; however, the expression of APC is

regulated by multiple miRNAs (62,63).

These regulatory abnormalities collectively promote the

accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm, providing sufficient

substrate for its nuclear translocation.

The mechanism by which β-catenin is transported from

the cytoplasm to the nucleus remains a subject of debate. Early

studies suggested that β-catenin lacks a classical nuclear

localization signal, does not bind to the nuclear transport

receptor Importin-β1 (64) and is

independent of the Ran-mediated classical nuclear import pathway.

Instead, its ARM structure was thought to enable selective passage

through the nuclear pore complex (65). However, more recent studies indicate

that the nuclear translocation of β-catenin is Ras-related nuclear

protein-dependent, with nuclear transport proteins such as KPNA2

(66) and Importin-11 (67) facilitating its nuclear import.

Once inside the nucleus, β-catenin binds with the

cofactors BCL9 and Pygo to form a complex that anchors it within

the nuclear space. This BCL9/Pygo complex significantly enhances

the affinity of β-catenin for the TCF/LEF transcriptional complex,

thereby preventing its nuclear export (68).

Other regulatory mechanisms can also influence

pathway activity. Beyond the classical Wnt pathway, the nuclear

translocation of β-catenin is affected by additional pathways. For

instance, the amplification or mutation of the EGFR gene can

activate AKT, which in turn stabilizes β-catenin by inhibiting

GSK-3β or directly phosphorylating the Ser552 residue, thereby

facilitating its nuclear entry (69).

The invasion and metastasis processes of malignant

cells rely on EMT, a key driver of cancer-related mortality

(70,71). EMT refers to the transformation of

epithelial cells into mesenchymal-like phenotypes. This process has

an important role in various biological processes, including

embryonic development, tissue regeneration and tumor invasion and

metastasis (72). During EMT, cells

acquire mesenchymal characteristics, such as cytoskeletal

alterations, loss of polarity and reduced intercellular adhesion.

These changes enhance the invasiveness, resistance to apoptosis and

migration ability of cells (73).

EMT is regulated by the Wnt signaling pathway. When

extracellular Wnt proteins bind to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6,

they form trimeric complexes that activate the Dvl protein

(20). This activation inhibits

GSK-3β phosphorylation, leading to the accumulation of cytoplasmic

and intranuclear β-catenin, thereby promoting the transcription of

Wnt target genes, such as Snail (78). This process accelerates EMT by

inhibiting the E-cadherin protein (5).

In addition to its role in cell adhesion, E-cadherin

inhibits β-catenin, thereby negatively regulating the classical Wnt

pathway (80). By forming a complex

with β-catenin, E-cadherin prevents the nuclear translocation of

β-catenin and helps maintain the cell-cell link. The nuclear

translocation of β-catenin, which stimulates transcriptional

activity and promotes EMT, is facilitated by both the stimulation

of the Wnt pathway and reduced E-cadherin protein expression

(81).

Additionally, Wnt regulators can modulate EMT by

affecting the transcriptional and translational levels of the

Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction pathway (82). Among these, miRNAs are key

regulators of Wnt signaling. These small molecules, typically 18–24

nucleotides in length, bind complementarily to the 3′ untranslated

region (UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or

translational inhibition (83).

Through this mechanism, miRNAs play a notable regulatory role in

tumorigenesis (84). A number of

miRNAs have been implicated in tumorigenesis, acting either as

oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Specifically, miRNAs can directly

regulate EMT-promoting signaling pathways and major transcription

factors involved in E-cadherin expression (74). Notably, the miR-200 family, along

with miR-101, miR-506, miR-155, miR-31 and miR-214, serves critical

roles in controlling both EMT and mesenchymal-epithelial

transition, thereby enabling cellular flexibility between the

epithelial and mesenchymal states during transition (84,85).

For example, in meningiomas, miR-200 suppresses the Wnt pathway by

blocking the translation of CTNNB1 mRNA (86). Similarly, miR-34 inhibits both the

Wnt/β-catenin/TCF signaling cascade and EMT by targeting conserved

regions within the WNT1, WNT3, CTNNB1, AXIN2, LRP6 and

LEF1 genes (87).

Furthermore, miR-214 interacts with β-catenin as a

hetero-transcriptional complex and negatively regulates the

transcription of downstream target genes (88). In NSCLC cells, miR-214 inhibits the

transmission of the Wnt signaling pathway by directly targeting the

3′-UTR of CTNNB1 (84).

Overall, alterations in the E-cadherin protein

expression levels, certain miRNAs and the CTNNB1 gene can

each regulate β-catenin protein expression, modulate the canonical

Wnt pathway and drive the progression of EMT.

The widespread use of immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) has provided significant clinical benefits for patients with

NSCLC (89). However, the

combination of pembrolizumab and chemotherapy achieves only a

~45.7% 2-year overall survival rate in these patients (90). Resistance to ICIs is commonly

associated with three mechanisms: Deficiency of major

histocompatibility complex class I (91), β-2-microglobulin gene deletions

(92) and mutations in the IFN-γ

signaling pathway (93). Studies

have also indicated that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in

tumors contributes to ICI resistance in lung cancer. This pathway

promotes immune evasion, supports carcinogenesis, facilitates

cancer progression and plays a role in shaping the TME (94–96).

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway promotes the expression of

activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), which in turn suppresses

the expression of C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4) (97). Reduced CCL4 expression leads to

decreased infiltration of antigen-presenting cells, impairs

lymphocyte homing to tumors and enables cancer cells to evade the

immune surveillance more effectively (98). Beyond inhibiting CCL4 synthesis

through ATF3, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway also exerts multiple

additional effects that promote immune evasion. In NSCLC,

activation of this pathway is associated with a higher tumor

mutational burden, suggesting that these cancer cells are likely to

be highly immunogenic (94).

Consequently, immune editing may be required for their survival.

Immune editing driven by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway involves three

primary mechanisms. First, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway modulates

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are typically classified

as M1 and M2. The M2 subtype promotes tumor proliferation,

migration and immune escape (99).

IL-1β generated by TAMs can phosphorylate GSK-3β, stabilizing

β-catenin and Snail and activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. This

activation, in turn, stimulates macrophages to produce additional

IL-1β, thereby enhancing tumor survival and metastatic potential

(100). Second, tumor cells with

activated β-catenin produce elevated levels of IL-10, which impairs

dendritic cells (DCs) and inhibits their maturation (101). Third, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

reshapes tumor metabolism, contributing to an immunosuppressive

TME. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway can increase

the expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 and

monocarboxylate transporter 1 (102), shifting cancer cell metabolism

from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis and creating a

more acidic TME. Collectively, these mechanisms facilitate tumor

cell evasion of the immune response. In addition to preventing the

activation of T cells and DCs, the lactic acid-rich

microenvironment can also stimulate the polarization of TAMs toward

the M2 subtype, as well as the expression of VEGF and

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (103). This microenvironment, shaped by

aerobic glycolysis, further suppresses T-cell activity, resulting

in resistance to ICIs (104).

In summary, tumor immune escape is closely

associated with hyperactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and

aberrant β-catenin production. Moreover, research has indicated

that patients with NSCLC who are β-catenin-positive generally

experience a poorer prognosis when treated with anti-programmed

cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy (95). These findings suggest that β-catenin

expression may serve as a prognostic marker for the efficacy of

anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with NSCLC.

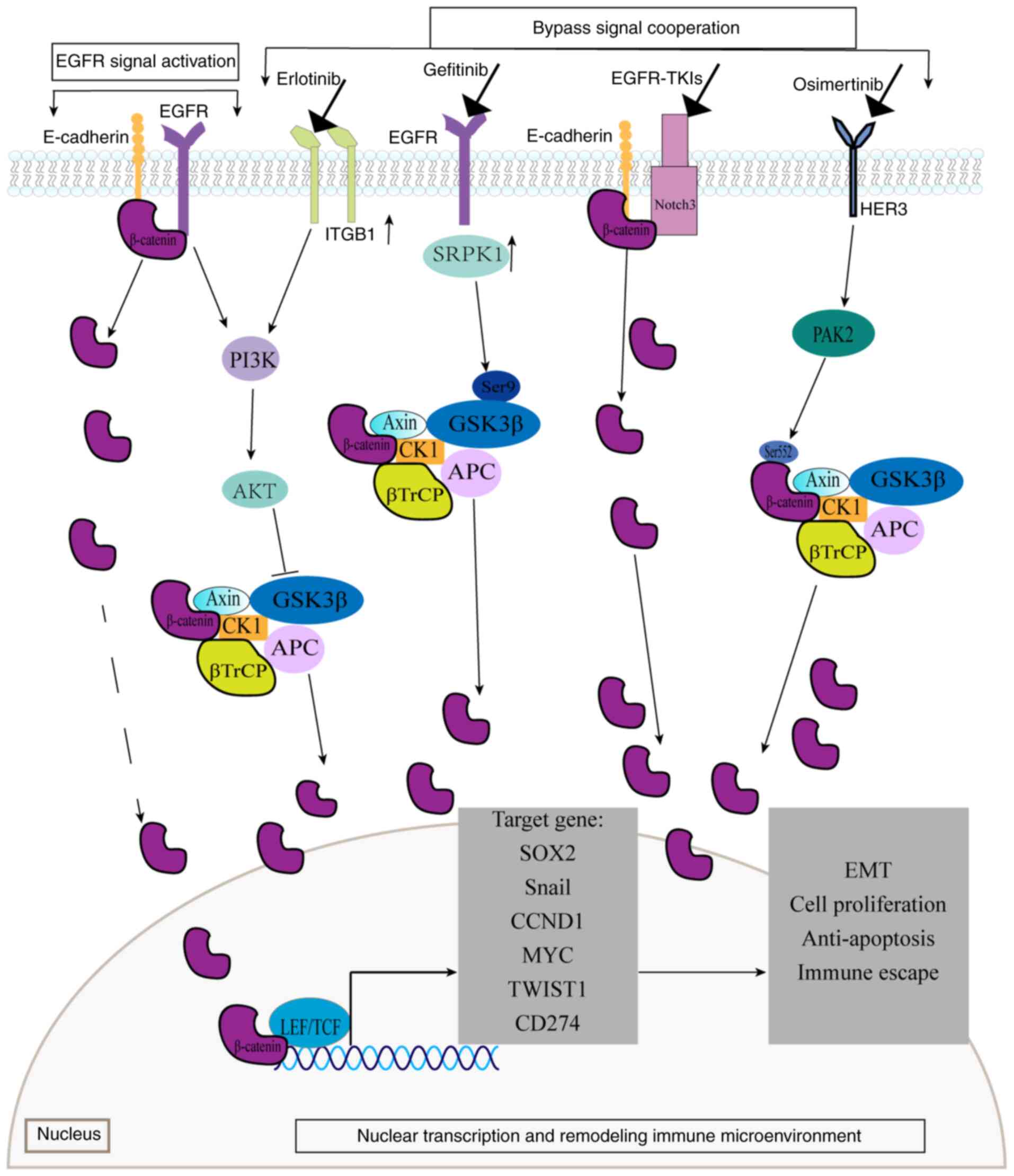

EGFR phosphorylates β-catenin at tyrosine residues

rather than at serine/threonine sites. This tyrosine

phosphorylation causes β-catenin to dissociate from the

α-catenin/E-cadherin complex, leading to increased intranuclear

β-catenin and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

(106). EGFR can also bind

directly to β-catenin, transactivating the classical Wnt pathway

through PI3K signaling (107).

Activation of the EGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway inhibits GSK-3β

activity, preventing β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation.

Consequently, the β-catenin protein accumulates in the cytoplasm

and initiates the classical Wnt pathway (108). These interactions demonstrate a

close connection between β-catenin and EGFR, with the Wnt and EGFR

signaling pathways functioning cooperatively. Therefore, β-catenin

can influence the effectiveness of EGFR-TKIs by activating its

signaling independently of direct EGFR interaction.

Furthermore, β-catenin mediates EGFR-TKI resistance

through synergistic interactions with bypass signaling pathways. In

the NOTCH3-dependent β-catenin resistance pathway, EGFR-TKI

treatment rapidly activates NOTCH3, which physically binds to the

β-catenin protein. This interaction increases the stability and

activation of β-catenin, promoting EMT and cell stemness and

ultimately driving EGFR-TKI resistance (109). Another critical mechanism involves

the HER3/p21-activated kinase2 (PAK2)/β-catenin signaling pathway,

which plays a significant role in osimertinib resistance (110). This pathway is activated in

osimertinib-treated cells, where PAK2 increases the phosphorylation

of β-catenin at Ser552, preventing its ubiquitination and

proteasomal degradation. This allows β-catenin to translocate into

the nucleus, where it upregulates the expression of the target

gene, SOX2, enhancing tumor stem cell-like characteristics

and contributing to osimertinib resistance. The membrane β1

integrin/AKT/β-catenin signaling pathway is associated with

erlotinib resistance. In erlotinib-resistant cells, the Rab25

protein is highly expressed, mediating the recycling of ITGB to the

plasma cell membrane, activating AKT and phosphorylating GSK-3β.

This results in β-catenin accumulation and enhanced tumor cell

proliferation (111). Similarly,

the serine-arginine protein kinase 1 (SRPK1)/GSK-3β axis promotes

gefitinib resistance. In gefitinib-treated cells, highly expressed

SRPK1 binds to Ser9 of GSK-3β, promoting GSK-3β autophosphorylation

and activating the Wnt pathway. SRPK1 also promotes the binding of

LEF1, β-catenin protein and the EGFR promoter, leading to an

increase in EGFR expression and contributing to drug resistance

(112).

β-catenin protein mediates EGFR-TKI resistance

through nuclear transcriptional regulation. Upon entering the

nucleus, β-catenin binds to TCF4, forming a complex that activates

genes associated with multidrug resistance. This includes the

activation of Snail transcription, which downregulates

E-cadherin expression and promotes EMT and tumor metastasis

(113). This complex also triggers

the transcription of CCND1, relieving cell cycle arrest and

sustaining tumor cell proliferation under TKI stress (114). Additionally, β-catenin activates

MYC transcription, promoting tumor cell growth and helping

cells evade immune surveillance (115). Furthermore, this complex induces

Twist1 transcription, which directly binds to the intron and

promoter regions of BCL2L11 (BIM), inhibiting

BIM transcription and conferring resistance to TKI-induced

apoptosis (116).

NSCLC resistance to EGFR-TKIs is associated with the

upregulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression

(117,118). Recent research indicates that

β-catenin contributes to EGFR-TKI resistance by promoting the

upregulation of PD-L1 in NSCLC (119). As noted earlier, EGFR signaling

activates the AKT/β-catenin pathway, and nuclear β-catenin can

increase PD-L1 levels while reducing CD8+ T cell

recruitment in tumors, thereby inducing drug resistance (97). The mechanism by which β-catenin

upregulates PD-L1 involves two pathways: First, nuclear β-catenin

forms a complex with TCF/LEF, increasing the transcriptional

activity of the CD274 promoter and upregulating PD-L1

expression (120); and second, the

same complex activates the target gene MYC, which further

stimulates PD-L1 transcription (115). Together, these processes promote

tumor immune escape, ultimately contributing to EGFR-TKI

resistance.

Chemotherapy and radiation resistance are associated

with aberrant β-catenin levels. For instance, in lung carcinoma

cells, the transfer of exosomal targeting protein for Xenopus

kinesin-like protein 2 promotes docetaxel resistance and cell

migration by increasing β-catenin expression and activating

downstream Wnt signaling (121).

In vitro experiments indicate that elevated β-catenin levels

can reduce the effect of cisplatin in lung cancer cells,

potentially contributing to cisplatin resistance (122). Additionally, Yin et al

(123) demonstrated through

bioinformatic analyses that ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T

promotes β-catenin upregulation by facilitating the

ubiquitin-dependent degradation of FOXO1, thereby driving EMT and

conferring radioresistance in NSCLC. Tumor cell resistance to

chemotherapy and radiation is associated with the characteristics

of cancer stem cells (CSCs) (124). Tumor stemness, a key biological

feature regulated by the CSC signaling network, describes the

ability of CSCs to self-renew and promote tumor formation (125). CSCs exhibit self-regeneration,

differentiation and dedifferentiation capacities, as well as

participate in the reprogramming of epithelium-mesenchymal,

immune-mediated, metabolic and epigenetic systems. These

adaptations enable them to survive the TME and resist host defenses

and therapeutic interventions (125). Furthermore, the expansion and

maintenance of CSCs are influenced, directly or indirectly, by the

classical Wnt pathway (126,127).

The intracellular localization and expression level

of β-catenin protein can be assessed using immunohistochemistry.

Tumor prognosis is negatively affected by both increased and

decreased membrane expression of β-catenin. In addition, increased

levels of cytoplasmic β-catenin protein or nuclear positivity are

correlated with reduced overall survival (43). This suggests that β-catenin levels

in the cytoplasm, nucleus and cell membrane can serve as important

prognostic indicators in patients with NSCLC (128). Elevated β-catenin levels are also

correlated with poorer immunotherapy results, suggesting its

potential as a predictor of the effectiveness of immunotherapy

(95). However, the commonly used

methods to determine β-catenin protein, such as western blotting,

immunohistochemistry and reporter gene plasmid assays, have

specific requirements regarding experimental conditions,

pathological tissues and cell states, which limits their clinical

applicability. By contrast, gene mutation data can be more readily

obtained through next-generation sequencing. For instance, ~6% of

LUADs harbor CTNNB1 mutations, which can be used in

predicting the postoperative recurrence of EGFR-mutated LUAD

(129). Moreover, CTNNB1

co-mutations may serve as potential predictors of the efficacy of

EGFR-TKIs in treating NSCLC, as patients with EGFR and

CTNNB1 co-mutations exhibit reduced responses to EGFR-TKIs

(130).

Despite extensive efforts to develop drugs targeting

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, to the best of our knowledge,

no effective treatments currently exist that directly target the

β-catenin protein. Recent clinical investigations indicate that 5

µM berberine liquid crystalline nanoparticles efficiently target

the Wnt signal by suppressing the production of CTNNB1 and

its corresponding protein, reducing both the gene and protein

levels in the human lung tumor cell line, A549 (131). The CTNNB1 gene can be

specifically targeted using RNA interference triggers incorporated

into the nanoparticle-based therapeutic known as Dicer-substrate

small interfering RNA targeting CTNNB1 (DCR-BCAT). DCR-BCAT

effectively suppresses β-catenin protein expression, significantly

increases T-cell infiltration and enhances tumor susceptibility to

ICIs, as demonstrated in a mouse tumor model (132). The nuclear localization inhibitor

of β-catenin, IMU-1003, significantly reduces colonies resistant to

osimertinib, suggesting that blocking intranuclear β-catenin can

overcome transgenerational EGFR-TKI resistance (133). Triptolide has also been reported

to reverse paclitaxel resistance and EMT in LUAD cells while

suppressing tumor progression by blocking the p70S6K/GSK3/β-catenin

pathway (134). Through its

interaction with β-catenin, ubiquitin-specific peptidase 5 (USP5)

helps to deubiquitinate, stabilize and activate the classical Wnt

pathway. When the small molecule WP1130 binds to USP5, it increases

β-catenin breakdown, which markedly lowers lung cancer cell

migration and infiltration (135).

Additionally, fucoxanthin exhibits antitumor potential in LUAD by

reversing EMT, limiting proliferation, inducing apoptosis and

downregulating the expression of TGF-β1, which can induce β-catenin

expression (136). Asiaticoside, a

triterpenoid saponin with antitumor properties, has been observed

to reduce intranuclear β-catenin levels and inhibit the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by promoting GSK-3β phosphorylation,

increasing APC expression and lowering Axin levels. This blockade

of EMT suppresses NSCLC growth and metastasis (137). In conclusion, various experimental

approaches primarily focus on directly targeting the CTNNB1

gene or lowering β-catenin levels to modulate the TME, reverse EMT,

suppress treatment resistance and inhibit tumor growth.

NSCLC development and progression are driven by the

β-catenin protein. Elevated nuclear β-catenin levels activate the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway, leading to aberrant cell division and

promoting carcinogenesis. This process induces EMT, remodels the

TME and facilitates cancer migration and immune evasion.

Not applicable.

Funding: Not applicable.

Not applicable.

LP wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. RG

and LH assisted with the literature search and manuscript revision.

TF and CB provided guidance and assisted in revising and correcting

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Luo G, Zhang Y, Rumgay H, Morgan E,

Langselius O, Vignat J, Colombet M and Bray F: Estimated worldwide

variation and trends in incidence of lung cancer by histological

subtype in 2022 and over time: A population-based study. Lancet

Respir Med. 13:348–363. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Georgakopoulos I, Kouloulias V, Ntoumas G,

Desse D, Koukourakis I, Kougioumtzopoulou A, Charpidou A, Syrigos

KN and Zygogianni A: Combined use of radiotherapy and tyrosine

kinase inhibitors in the management of metastatic non-small cell

lung cancer: A literature review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

204:1045202024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mieras A, Pasman HRW, Onwuteaka-Philipsen

BD, Dingemans AMMC, Kok EV, Cornelissen R, Jacobs W, van den Berg

JW, Welling A, Bogaarts BAHA, et al: Is in-hospital mortality

higher in patients with metastatic lung cancer who received

treatment in the last month of life? A retrospective cohort study.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 58:805–811. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang

X, Zhou Z, Shu G and Yin G: Wnt/β-catenin signalling: Function,

biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:32022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

White BD, Chien AJ and Dawson DW:

Dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal

cancers. Gastroenterology. 142:219–232. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yeh Y, Guo Q, Connelly Z, Cheng S, Yang S,

Prieto-Dominguez N and Yu X: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and

prostate cancer therapy resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1210:351–378.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mukherjee N, Bhattacharya N, Alam N, Roy

A, Roychoudhury S and Panda CK: Subtype-specific alterations of the

Wnt signaling pathway in breast cancer: clinical and prognostic

significance. Cancer Sci. 103:210–220. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Skronska-Wasek W, Gosens R, Königshoff M

and Baarsma HA: WNT receptor signalling in lung physiology and

pathology. Pharmacol Ther. 187:150–166. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang Z, Westover D, Tang Z, Liu Y, Sun J,

Sun Y, Zhang R, Wang X, Zhou S, Hesilaiti N, et al: Wnt/β-catenin

signaling in the development and therapeutic resistance of

non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 22:5652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gao C, Wang Y, Broaddus R, Sun L, Xue F

and Zhang W: Exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 drive tumorigenesis: A

review. Oncotarget. 9:5492–5508. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ma Q, Yu J, Zhang X, Wu X and Deng G:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway-a versatile player in apoptosis and

autophagy. Biochimie. 211:57–67. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

MacDonald BT, Tamai K and He X:

Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: Components, mechanisms, and diseases.

Dev Cell. 17:9–26. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y and Vallée JN:

The key role of the WNT/β-catenin pathway in metabolic

reprogramming in cancers under normoxic conditions. Cancers

(Basel). 13:55572021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Parsons MJ, Tammela T and Dow LE: WNT as a

driver and dependency in cancer. Cancer Discov. 11:2413–2429. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kleeman SO and Leedham SJ: Not all Wnt

activation is equal: ligand-dependent versus ligand-independent Wnt

activation in colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12:33552020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu F and Millar SE: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling in oral tissue development and disease. J Dent Res.

89:318–330. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao DM, Yu S, Zhou X, Haring JS, Held W,

Badovinac VP, Harty JT and Xue HH: Constitutive activation of Wnt

signaling favors generation of memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol.

184:1191–1199. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hurlstone A and Clevers H: T-cell factors:

Turn-ons and turn-offs. EMBO J. 21:2303–2311. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dale TC: Signal transduction by the Wnt

family of ligands. Biochem J. 329:209–223. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Howell BW and Herz J: The LDL receptor

gene family: Signaling functions during development. Curr Opin

Neurobiol. 11:74–81. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Moon RT, Bowerman B, Boutros M and

Perrimon N: The promise and perils of Wnt signaling through

beta-catenin. Science. 296:1644–1646. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sharma A, Mir R and Galande S: Epigenetic

regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. Front

Genet. 12:6810532021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yamamoto S, Nishimura O, Misaki K, Nishita

M, Minami Y, Yonemura S, Tarui H and Sasaki H: Cthrc1 selectively

activates the planar cell polarity pathway of Wnt signaling by

stabilizing the Wnt-receptor complex. Dev Cell. 15:23–36. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Feng D, Wang J, Yang W, Li J, Lin X, Zha

F, Wang X, Ma L, Choi NT, Mii Y, et al: Regulation of Wnt/PCP

signaling through p97/VCP-KBTBD7-mediated Vangl ubiquitination and

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Sci Adv.

7:eabg20992021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cai Y, Cai T and Chen Y: Wnt pathway in

osteosarcoma, from oncogenic to therapeutic. J Cell Biochem.

115:625–631. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Martineau X, Abed É, Martel-Pelletier J,

Pelletier JP and Lajeunesse D: Alteration of Wnt5a expression and

of the non-canonical Wnt/PCP and Wnt/PKC-Ca2+ pathways in human

osteoarthritis osteoblasts. PLoS One. 12:e01807112017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

De A: Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway: A brief

overview. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 43:745–756. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Anastas JN and Moon RT: WNT signalling

pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

13:11–26. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang X, Lou Y, Zheng X, Wang H, Sun J,

Dong Q and Han B: Wnt blockers inhibit the proliferation of lung

cancer stem cells. Drug Des Devel Ther. 9:2399–2407.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kren L, Hermanová M, Goncharuk VN, Kaur P,

Ross JS, Pavlovský Z and Dvorák K: Downregulation of plasma

membrane expression/cytoplasmic accumulation of beta-catenin

predicts shortened survival in non-small cell lung cancer. A

clinicopathologic study of 100 cases. Cesk Patol. 39:17–20.

2003.

|

|

32

|

Daniels DL, Eklof Spink K and Weis WI:

beta-catenin: Molecular plasticity and drug design. Trends Biochem

Sci. 26:672–678. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Städeli R, Hoffmans R and Basler K:

Transcription under the control of nuclear Arm/beta-catenin. Curr

Biol. 16:R378–R385. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kishida S, Yamamoto H, Ikeda S, Kishida M,

Sakamoto I, Koyama S and Kikuchi A: Axin, a negative regulator of

the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous

polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of beta-catenin. J

Biol Chem. 273:10823–10826. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A

and Kemler R: beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome

pathway. EMBO J. 16:3797–3804. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Conacci-Sorrell M, Zhurinsky J and

Ben-Ze'ev A: The cadherin-catenin adhesion system in signaling and

cancer. J Clin Invest. 109:987–991. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Xing Y, Takemaru KI, Liu J, Berndt JD,

Zheng JJ, Moon RT and Xu W: Crystal structure of a full-length

beta-catenin. Structure. 16:478–487. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kase S, Sugio K, Yamazaki K, Okamoto T,

Yano T and Sugimachi K: Expression of E-cadherin and beta-catenin

in human non-small cell lung cancer and the clinical significance.

Clin Cancer Res. 6:4789–4796. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Baum B and Georgiou M: Dynamics of

adherens junctions in epithelial establishment, maintenance, and

remodeling. J Cell Biol. 192:907–917. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li LF, Wei ZJ, Sun H and Jiang B: Abnormal

β-catenin immunohistochemical expression as a prognostic factor in

gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol.

20:12313–12321. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Klaus A and Birchmeier W: Wnt signalling

and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

8:387–398. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rim EY, Clevers H and Nusse R: The Wnt

pathway: From signaling mechanisms to synthetic modulators. Annu

Rev Biochem. 91:571–598. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yoo SB, Kim YJ, Kim H, Jin Y, Sun PL,

Jheon S, Lee JS and Chung JH: Alteration of the

E-cadherin/β-catenin complex predicts poor response to epidermal

growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI)

treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 20 (Suppl 3):S545–S552. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Li XQ, Yang XL, Zhang G, Wu SP, Deng XB,

Xiao SJ, Liu QZ, Yao KT and Xiao GH: Nuclear β-catenin accumulation

is associated with increased expression of Nanog protein and

predicts poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl

Med. 11:1142013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Polakis P: Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes

Dev. 14:1837–1851. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kikuchi A: Tumor formation by genetic

mutations in the components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer

Sci. 94:225–229. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Amit S, Hatzubai A, Birman Y, Andersen JS,

Ben-Shushan E, Mann M, Ben-Neriah Y and Alkalay I: Axin-mediated

CKI phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 45: A molecular switch

for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 16:1066–1076. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhou C, Jin H, Li W, Zhao R and Chen C:

CTNNB1 S37C mutation causing cells proliferation and migration

coupled with molecular mechanisms in lung adenocarcinoma. Ann

Transl Med. 9:6812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hu S, Chang J, Ruan H, Zhi W, Wang X, Zhao

F, Ma X, Sun X, Liang Q, Xu H, et al: Cantharidin inhibits

osteosarcoma proliferation and metastasis by directly targeting

miR-214-3p/DKK3 axis to inactivate β-catenin nuclear translocation

and LEF1 translation. Int J Biol Sci. 17:2504–2522. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Anthony CC, Robbins DJ, Ahmed Y and Lee E:

Nuclear regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling: It's a complex

situation. Genes (Basel). 11:8862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Kim W, Kim M and Jho E: Wnt/β-catenin

signalling: From plasma membrane to nucleus. Biochem J. 450:9–21.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhang Y, Liu H, Zhang Q and Zhang Z: Long

noncoding RNA LINC01006 facilitates cell proliferation, migration,

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung adenocarcinoma via

targeting the MicroRNA 129-2-3p/CTNNB1 axis and activating

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 41:e00380202021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zheng JY, Zhu T, Zhuo W, Mao XY, Yin JY,

Li X, He YJ, Zhang W, Liu C and Liu ZQ: eIF3a sustains non-small

cell lung cancer stem cell-like properties by promoting

YY1-mediated transcriptional activation of β-catenin. Biochem

Pharmacol. 213:1156162023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Liu S, Yang N, Wang L, Wei B, Chen J and

Gao Y: lncRNA SNHG11 promotes lung cancer cell proliferation and

migration via activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Cell

Physiol. 235:7541–7553. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wei X, Liao J, Lei Y, Li M, Zhao G, Zhou

Y, Ye L and Huang Y: Retraction: WSB2 as a target of Hedgehog

signaling promoted the malignantbiological behavior of Xuanwei lung

cancer through regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Transl Cancer

Res. 13:51612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liao Y, Feng J, Sun W, Wu C, Li J, Jing T,

Liang Y, Qian Y, Liu W and Wang H: CIRP promotes the progression of

non-small cell lung cancer through activation of Wnt/β-catenin

signaling via CTNNB1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:2752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu C, Liu L, Zhang Y and Jing H:

Molecular mechanism of AQP3 in regulating differentiation and

apoptosis of lung cancer stem cells through Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin

pathway. J BUON. 25:1714–1720. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang F, Xiong H, Duan L, Li Q, Li X and

Zhou Y: MiR-1246 promotes metastasis and invasion of A549 cells by

targeting GSK-3β-mediated Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cancer Res Treat.

51:1420–1429. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Lei L, Wang Y, Li ZH, Fei LR, Huang WJ,

Zheng YW, Liu CC, Yang MQ, Wang Z, Zou ZF and Xu HT: PHLDA3

promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation and invasion via

activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Lab Invest. 101:1130–1141.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Shi X, Zhao Y and Fan C: Zbed3 promotes

proliferation and invasion of lung cancer partly through regulating

the function of Axin-Gsk3β complex. J Cell Mol Med. 23:1014–1021.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Xu X, Zhang Y, Wang M, Zhang X, Jiang W,

Wu S and Ti X: A peptide encoded by a long non-coding RNA DLX6-AS1

facilitates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by

activating the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in non-small-cell

lung cancer cell. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 32:43–53. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Xu G, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Chen Y, Li N, Lv

Y, Li Y and Xu X: miR-4326 promotes lung cancer cell proliferation

through targeting tumor suppressor APC2. Mol Cell Biochem.

443:151–157. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Cen W, Yan Q, Zhou W, Mao M, Huang Q, Lin

Y and Jiang N: miR-4739 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and angiogenesis in ‘driver gene-negative’ non-small cell lung

cancer via activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 46:1821–1835. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yokoya F, Imamoto N, Tachibana T and

Yoneda Y: beta-catenin can be transported into the nucleus in a

Ran-unassisted manner. Mol Biol Cell. 10:1119–1131. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Andrade MA, Petosa C, O'Donoghue SI,

Müller CW and Bork P: Comparison of ARM and HEAT protein repeats. J

Mol Biol. 309:1–18. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Altan B, Yokobori T, Mochiki E, Ohno T,

Ogata K, Ogawa A, Yanai M, Kobayashi T, Luvsandagva B, Asao T and

Kuwano H: Nuclear karyopherin-α2 expression in primary lesions and

metastatic lymph nodes was associated with poor prognosis and

progression in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 34:2314–2321. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Mis M, O'Brien S, Steinhart Z, Lin S, Hart

T, Moffat J and Angers S: IPO11 mediates βcatenin nuclear import in

a subset of colorectal cancers. J Cell Biol. 219:e2019030172020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Krieghoff E, Behrens J and Mayr B:

Nucleo-cytoplasmic distribution of beta-catenin is regulated by

retention. J Cell Sci. 119:1453–1463. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Fang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y,

Meisenhelder J, Nika H, Mills GB, Kobayashi R, Hunter T and Lu Z:

Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin

transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 282:11221–11229. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Lee GA, Hwang KA and Choi KC: Roles of

dietary phytoestrogens on the regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in diverse cancer metastasis. Toxins (Basel). 8:1622016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chaffer CL and Weinberg RA: A perspective

on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 331:1559–1564. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Dongre A and Weinberg RA: New insights

into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:69–84. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Kalluri R and Weinberg RA: The basics of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 119:1420–1428.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Guo F, Parker Kerrigan BC, Yang D, Hu L,

Shmulevich I, Sood AK, Xue F and Zhang W: Post-transcriptional

regulatory network of epithelial-to-mesenchymal and

mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions. J Hematol Oncol. 7:192014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Pertz O, Bozic D, Koch AW, Fauser C,

Brancaccio A and Engel J: A new crystal structure, Ca2+ dependence

and mutational analysis reveal molecular details of E-cadherin

homoassociation. EMBO J. 18:1738–1747. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kim YS, Yi BR, Kim NH and Choi KC: Role of

the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its effects on embryonic

stem cells. Exp Mol Med. 46:e1082014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Heuberger J and Birchmeier W: Interplay of

cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and canonical Wnt signaling. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2:a0029152010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Eijkelenboom A and Burgering BMT: FOXOs:

Signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 14:83–97. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Bustamante A, Baritaki S, Zaravinos A and

Bonavida B: Relationship of signaling pathways between RKIP

expression and the inhibition of EMT-inducing transcription factors

SNAIL1/2, TWIST1/2 and ZEB1/2. Cancers (Basel). 16:31802024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S and Brabletz T:

E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of

cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28:151–166. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Ghahhari NM and Babashah S: Interplay

between microRNAs and WNT/β-catenin signalling pathway regulates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Eur J Cancer.

51:1638–1649. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Stewart DJ: Wnt signaling pathway in

non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 106:djt3562014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Mármol-Sánchez E, Luigi-Sierra MG,

Castelló A, Guan D, Quintanilla R, Tonda R and Amills M:

Variability in porcine microRNA genes and its association with mRNA

expression and lipid phenotypes. Genet Sel Evol. 53:432021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Zhao H, Wang Z, Wu G, Lu Y, Zheng J, Zhao

Y, Han Y, Wang J, Yang L, Du J and Wang E: Role of MicroRNA-214 in

dishevelled1-modulated β-catenin signalling in non-small cell lung

cancer progression. J Cancer. 14:239–249. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Tian Y, Pan Q, Shang Y, Zhu R, Ye J, Liu

Y, Zhong X, Li S, He Y, Chen L, et al: MicroRNA-200 (miR-200)

cluster regulation by achaete scute-like 2 (Ascl2): Impact on the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells. J Biol

Chem. 289:36101–36115. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Saydam O, Shen Y, Würdinger T, Senol O,

Boke E, James MF, Tannous BA, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Yi M, Stephens

RM, et al: Downregulated microRNA-200a in meningiomas promotes

tumor growth by reducing E-cadherin and activating the

Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 29:5923–5940.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Cha YH, Kim NH, Park C, Lee I, Kim HS and

Yook JI: MiRNA-34 intrinsically links p53 tumor suppressor and Wnt

signaling. Cell Cycle. 11:1273–1281. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Yi B, Wang S, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhang C, Li

M, Gao S, Wei S, Bae S, Stringer-Reasor E, et al: CRISPR

interference and activation of the microRNA-3662-HBP1 axis control

progression of triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 41:268–279.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Friedlaender A, Naidoo J, Banna GL, Metro

G, Forde P and Addeo A: Role and impact of immune checkpoint

inhibitors in neoadjuvant treatment for NSCLC. Cancer Treat Rev.

104:1023502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Rodríguez-Abreu D, Powell SF, Hochmair MJ,

Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, Speranza G, De Angelis F, Dómine M,

Cheng SY, et al: Pemetrexed plus platinum with or without

pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated metastatic

nonsquamous NSCLC: Protocol-specified final analysis from

KEYNOTE-189. Ann Oncol. 32:881–895. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Montesion M, Murugesan K, Jin DX, Sharaf

R, Sanchez N, Guria A, Minker M, Li G, Fisher V, Sokol ES, et al:

Somatic HLA class I loss is a widespread mechanism of immune

evasion which refines the use of tumor mutational burden as a

biomarker of checkpoint inhibitor response. Cancer Discov.

11:282–292. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS,

Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, Hu-Lieskovan S, Torrejon DY,

Abril-Rodriguez G, Sandoval S, Barthly L, et al: Mutations

associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N

Engl J Med. 375:819–829. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Han P, Dai Q, Fan L, Lin H, Zhang X, Li F

and Yang X: Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies JAK1 deficiency

as a mechanism of T-cell resistance. Front Immunol. 10:2512019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Takeuchi Y, Tanegashima T, Sato E, Irie T,

Sai A, Itahashi K, Kumagai S, Tada Y, Togashi Y, Koyama S, et al:

Highly immunogenic cancer cells require activation of the WNT

pathway for immunological escape. Sci Immunol. 6:eabc64242021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Muto S, Ozaki Y, Yamaguchi H, Watanabe M,

Okabe N, Matsumura Y, Hamada K and Suzuki H: Tumor β-catenin

expression associated with poor prognosis to anti-PD-1 antibody

monotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Diagn Progn.

5:32–41. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Galluzzi L, Spranger S, Fuchs E and

López-Soto A: WNT signaling in cancer immunosurveillance. Trends

Cell Biol. 29:44–65. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Spranger S, Bao R and Gajewski TF:

Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour

immunity. Nature. 523:231–235. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Muto S, Inomata S, Yamaguchi H, Mine H,

Takagi H, Watanabe M, Ozaki Y, Inoue T, Yamaura T, Fukuhara M, et

al: β-catenin expression in non-small cell lung cancer and

therapeutic effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Gan To Kagaku

Ryoho. 49:947–949. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

DeNardo DG and Ruffell B: Macrophages as

regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol.

19:369–382. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Kaler P, Augenlicht L and Klampfer L:

Activating mutations in β-catenin in colon cancer cells alter their

interaction with macrophages; the role of snail. PLoS One.

7:e454622012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Yaguchi T, Goto Y, Kido K, Mochimaru H,

Sakurai T, Tsukamoto N, Kudo-Saito C, Fujita T, Sumimoto H and

Kawakami Y: Immune suppression and resistance mediated by

constitutive activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human

melanoma cells. J Immunol. 189:2110–2117. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Pate KT, Stringari C, Sprowl-Tanio S, Wang

K, TeSlaa T, Hoverter NP, McQuade MM, Garner C, Digman MA, Teitell

MA, et al: Wnt signaling directs a metabolic program of glycolysis

and angiogenesis in colon cancer. EMBO J. 33:1454–1473. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Pavlova NN and Thompson CB: The emerging

hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 23:27–47. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Lim AR, Rathmell WK and Rathmell JC: The

tumor microenvironment as a metabolic barrier to effector T cells

and immunotherapy. Elife. 9:e551852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Nakayama S, Sng N, Carretero J, Welner R,

Hayashi Y, Yamamoto M, Tan AJ, Yamaguchi N, Yasuda H, Li D, et al:

β-catenin contributes to lung tumor development induced by EGFR

mutations. Cancer Res. 74:5891–5902. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Lilien J and Balsamo J: The regulation of

cadherin-mediated adhesion by tyrosine

phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of beta-catenin. Curr Opin Cell

Biol. 17:459–465. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J,

Huang W, Gao X, Aldape K and Lu Z: Nuclear PKM2 regulates β-catenin

transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 480:118–122. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Hu T and Li C: Convergence between

Wnt-β-catenin and EGFR signaling in cancer. Mol Cancer. 9:2362010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Arasada RR, Shilo K, Yamada T, Zhang J,

Yano S, Ghanem R, Wang W, Takeuchi S, Fukuda K, Katakami N, et al:

Notch3-dependent β-catenin signaling mediates EGFR TKI drug

persistence in EGFR mutant NSCLC. Nat Commun. 9:31982018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Yi Y, Li P, Huang Y, Chen D, Fan S, Wang

J, Yang M, Zeng S, Deng J, Lv X, et al: P21-activated kinase

2-mediated β-catenin signaling promotes cancer stemness and

osimertinib resistance in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer.

Oncogene. 41:4318–4329. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wang J, Zhou P, Wang X, Yu Y, Zhu G, Zheng

L, Xu Z, Li F, You Q, Yang Q, et al: Rab25 promotes erlotinib

resistance by activating the β1 integrin/AKT/β-catenin pathway in

NSCLC. Cell Prolif. 52:e125922019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Huang JQ, Duan LX, Liu QY, Li HF, Hu AP,

Song JW, Lin C, Huang B, Yao D, Peng B, et al: Serine-arginine

protein kinase 1 (SRPK1) promotes EGFR-TKI resistance by enhancing

GSK3β Ser9 autophosphorylation independent of its kinase activity

in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 42:1233–1246. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Tripathi SK and Biswal BK: SOX9 promotes

epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor

resistance via targeting β-catenin and epithelial to mesenchymal

transition in lung cancer. Life Sci. 277:1196082021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Liu B, Chen D, Chen S, Saber A and Haisma

H: Transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 via HER2/HER3

contributes to EGFR-TKI resistance in lung cancer. Biochem

Pharmacol. 178:1140952020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Wang G, Li T, Wan Y and Li Q: MYC

expression and fatty acid oxidation in EGFR-TKI acquired

resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 72:1010192024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Yochum ZA, Cades J, Wang H, Chatterjee S,

Simons BW, O'Brien JP, Khetarpal SK, Lemtiri-Chlieh G, Myers KV,

Huang EHB, et al: Targeting the EMT transcription factor TWIST1

overcomes resistance to EGFR inhibitors in EGFR-mutant

non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 38:656–670. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Ding W, Yang P, Zhao X and Wang X, Liu H,

Su Q and Wang X, Li J, Gong Z, Zhang D and Wang X: Unraveling

EGFR-TKI resistance in lung cancer with high PD-L1 or TMB in

EGFR-sensitive mutations. Respir Res. 25:402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Peng S, Wang R, Zhang X, Ma Y, Zhong L, Li

K, Nishiyama A, Arai S, Yano S and Wang W: EGFR-TKI resistance

promotes immune escape in lung cancer via increased PD-L1

expression. Mol Cancer. 18:1652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Huang Z, Wang J, Xia Z, Lv Q, Ruan Z and

Dai Y: Wnt/β-catenin pathway-mediated PD-L1 overexpression

facilitates the resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells to

epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Discov

Med. 36:2300–2308. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Du L, Lee JH, Jiang H, Wang C, Wang S,

Zheng Z, Shao F, Xu D, Xia Y, Li J, et al: β-Catenin induces

transcriptional expression of PD-L1 to promote glioblastoma immune

evasion. J Exp Med. 217:e201911152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Hu J, He Q, Tian T, Chang N and Qian L:

Transmission of exosomal TPX2 promotes metastasis and resistance of

NSCLC cells to docetaxel. Onco Targets Ther. 16:197–210. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Jiang Y, Hu X, Pang M, Huang Y, Ren B, He

L and Jiang L: RRM2-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

activation in lung adenocarcinoma: A potential prognostic

biomarker. Oncol Lett. 26:4172023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Yin H, Wang X, Zhang X, Zeng Y, Xu Q, Wang

W, Zhou F and Zhou Y: UBE2T promotes radiation resistance in

non-small cell lung cancer via inducing epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and the ubiquitination-mediated FOXO1 degradation.

Cancer Lett. 494:121–131. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Katoh M and Katoh M: WNT signaling and

cancer stemness. Essays Biochem. 66:319–331. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Katoh M: Canonical and non-canonical WNT

signaling in cancer stem cells and their niches: Cellular

heterogeneity, omics reprogramming, targeted therapy and tumor

plasticity (Review). Int J Oncol. 51:1357–1369. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Katoh M and Katoh M: WNT signaling pathway

and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 13:4042–4045.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Katoh M and Katoh M: Molecular genetics

and targeted therapy of WNT-related human diseases (Review). Int J

Mol Med. 40:587–606. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Jin J, Zhan P, Katoh M, Kobayashi SS, Phan

K, Qian H, Li H, Wang X, Wang X and Song Y; written on behalf of

the AME Lung Cancer Collaborative Group, : Prognostic significance

of β-catenin expression in patients with non-small cell lung

cancer: A meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 6:97–108. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Kim Y, Ahn B, Yoon S, Lee G, Kim D, Chun

SM, Kim HR, Jang SJ and Hwang HS: An oncogenic CTNNB1 mutation is

predictive of post-operative recurrence-free survival in an

EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 18:e02872562023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Taniguchi Y, Tamiya A, Osuga M, Harada D,

Isa SI, Nakamura K, Mizumori Y, Shinohara T, Yanai H, Nakatomi K,

et al: Baseline genetic abnormalities and effectiveness of

osimertinib treatment in patients with chemotherapy-naïve

EGFR-mutated NSCLC based on performance status. BMC Pulm Med.

24:4072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Malyla V, De Rubis G, Paudel KR,

Chellappan DK, Hansbro NG, Hansbro PM and Dua K: Berberine

nanostructures attenuate ß-catenin, a key component of epithelial

mesenchymal transition in lung adenocarcinoma. Naunyn Schmiedebergs

Arch Pharmacol. 396:3595–3603. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Ganesh S, Shui X, Craig KP, Park J, Wang

W, Brown BD and Abrams MT: RNAi-mediated β-catenin inhibition

promotes T cell infiltration and antitumor activity in combination

with immune checkpoint blockade. Mol Ther. 26:2567–2579. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Katagiri H, Yonezawa H, Shitamura S,

Sugawara A, Kawano T, Maemondo M and Nishiya N: A Wnt/β-catenin

signaling inhibitor, IMU1003, suppresses the emergence of

osimertinib-resistant colonies from gefitinib-resistant non-small

cell lung cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 645:24–29.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Tian Y, Li P, Xiao Z, Zhou J, Xue X, Jiang

N, Peng C, Wu L, Tian H, Popper H, et al: Triptolide inhibits

epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype through the

p70S6k/GSK3/β-catenin signaling pathway in taxol-resistant human

lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 10:1007–1019. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Tung CH, Wu JE, Huang MF, Wang WL, Wu YY,

Tsai YT, Hsu XR, Lin SH, Chen YL and Hong TM: Ubiquitin-specific

peptidase 5 facilitates cancer stem cell-like properties in lung

cancer by deubiquitinating β-catenin. Cancer Cell Int. 23:2072023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

136

|

Luan H, Yan L, Zhao Y, Ding X and Cao L:

Fucoxanthin induces apoptosis and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal

transition via inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin pathway in lung

adenocarcinoma. Discov Oncol. 13:982022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Zhang Y, Liu J, Yang G, Zou J, Tan Y, Xi

E, Geng Q and Wang Z: Asiaticoside inhibits growth and metastasis

in non-small cell lung cancer by disrupting EMT via Wnt/β-catenin

pathway. Environ Toxicol. 39:4859–4870. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|