Introduction

Head and neck carcinoma accounts for 4.6% of all

cancers worldwide, and there has been an annual 1.4-fold increase

in the number of new cases per year during the last decade

(1,2). Squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) comprise

the most common type of malignancy in this wide anatomical region,

which includes the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx (3). Although tobacco smoke and alcohol

consumption are traditionally considered major risk factors for

head and neck SCC (HNSCC), viruses are also accountable (4). Two types of viruses, namely, Human

Papilloma Virus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr Virus, are strongly

associated with oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal SCC, respectively,

since virus-associated carcinomas exhibit a predilection for sites

with lymphoid-based mucosa (3,5). In

fact, according to the latest recommendations of The College of

American Pathologists, all newly diagnosed oropharyngeal SCC should

be examined by immunohistochemistry, using p16 as a surrogate

marker for potential HPV infection (6), while HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer

is currently considered as a unique disease entity in both the

pathological (7) and clinical

(8) context. Emerging molecular

drivers such as lncRNA BLACAT1 have been implicated in adjacent

sites like hypopharyngeal SCC (9),

underscoring the need to integrate morphologic and transcriptomic

data in future studies. Epigenetic dysregulation is a common

feature across cancers; chromatin-remodeling complex

vulnerabilities may provide novel therapeutic targets in HNSCC, as

recently suggested for a different type of tumors (10).

Several studies have reported the significance of

both tumor cells and tumor microenvironment histopathological

characteristics in HNSCC. Emerging data have highlighted the

importance of phenotypic heterogeneity in these carcinomas and its

role in the development and progression of the tumors as well as in

treatment efficacy (11). In this

context, the prognostic value of traditional grading is debatable,

whereas other histopathological features, i.e. worst pattern of

invasion and intensity of lymphocytic infiltration in the invasive

margin of HNSCC, seem directly associated with patient overall

survival (OS) (12,13).

In the present study, we assessed histopathological

parameters of tumor cells and their microenvironment in tumor

compartments (center and invasive margin) of HNSCC originating in

different anatomical sites. We evaluated these parameters against

each other and against clinicopathological characteristics of the

patients to identify potential risk factors with clinical

relevance.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and patient data

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples from

patients with histologically confirmed HNSCC and available

clinical, histopathological, treatment, and outcome data were

retrieved from the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG)

clinical database and biologic material repository. Since

nasopharyngeal carcinoma is generally considered a biologically

different disease compared to SCC of the rest of the head and neck

region, especially in Far East and Mediterranean basin, we explored

this neoplasm separately on genomic, histopathological and clinical

basis (14–16) and it was excluded from this study.

In the same line, p16 positive HNSCC considered as HPV-related,

which are biologically different from other HNSCC (7), were excluded, as well. Patients with

HNSCC were diagnosed and treated between 1999 and 2018. Written

informed consent was obtained from all patients for the use of

their data and biologic material for research purposes. The

protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Aristotle

University of Thessaloniki, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of

Medicine (approval no. 5/18.12.2019; Thessaloniki, Greece).

New Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) sections from

all tissue blocks were reviewed for histological evaluation and

tumor tissue adequacy (tumor cells and stroma). The tumor surface

area was separated into tumor center and invasive margin according

to the literature (17,18). As such, the invasive margin was

defined as the region around the border where normal tissue meets

malignant cells, extending by 1 millimeter. Samples from advanced

HNSCC that were not obtained from the primary site (e.g.,

metastatic lymph nodes) or where a primary site could not be

determined, were annotated as ‘local spread’. Based on the

availability of clinical data and adequate tumor tissue, 248 tumors

from the same number of patients were examined. Patient age at

first diagnosis ranged from 20.9 to 85.1 years, with a median of 62

years.

Histological evaluation

Parameters assessed on whole H&E sections were:

i) Keratinization (present/absent). Tumors exhibiting squamous

maturation features on less than 10% of their surface were not

classified as keratinizing (19);

ii) area occupied by keratin pearls as percentage of the entire

tumor area; iii) presence of specific spatial distribution of

neutrophils, that is, neutrophils in tumor necrotic areas and in

close proximity to dyskeratotic cells, as well as microabscesses in

keratinization; iv) histologic grading, according to the three-tier

grading system (G1, G2, G3) (20);

v) extent of tumor necrosis, as absent, focal (≤10% of the tumor

area), moderate (11–29% of the tumor area), or extensive (≥30% of

the tumor area) (21); and the

presence of necrosis in keratinization areas. However, since only

one case exhibited extensive necrosis, it was included in the

moderate group; vi) anaplastic cells defined as cells with lack of

differentiation, showing pleomorphism, nuclear abnormalities,

atypical mitoses and loss of polarity (present/absent) (22); vii) cell cannibalism, which

corresponds to cell-in-cell phenomenon, a process of non-apoptotic

cell death, where one cancer cell surrounds another cancer cell

(present/absent) (23); viii) tumor

stroma classification, as myxoid, when there was an amorphous

stromal substance comprising of slightly basophilic extracellular

matrix; as keloid-like, regulated by specific channels (24), when thick bundles of hypocellular

collagen with bright eosinophilic hyalinization were evident; or as

fibroblastic, when only fine mature collagen fibers were evident

(25); ix) tumor infiltrating

lymphocyte (TIL) density; according to international guidelines

(17,26), ten high-power fields of each section

excluding pre-existing lymphoid background areas (17,27),

were assessed, and the mean average was estimated; and x)

perineural and lymphovascular invasion (present/absent). The

presence of calcification and giant cell reaction was also

recorded.

Eosinophil number per mm2 was evaluated

similarly to CD8+ counts on Tissue MicroArray (TMA)

sections (28).

Histological parameters in the invasive margin were

examined separately, based on previous studies (5,12,13,29):

keratinization was assessed as absent (0.5% of the invasive margin

area), low (6–20%), moderate (21–50%), and high (<50%); cellular

atypia and pleomorphism were estimated as mild, moderate, and

severe; mature squamous cells with angular shape, eosinophilic

cytoplasm, and intercellular bridges were recorded in a four-tier

scale, based on their abundance (0–25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, and

<75%); lymphocytic host response along the invasive margin was

recorded as dense (dense lymphocytic response rimming the tumor

and/or lymphoid nodules at advancing edge in each 4× field),

intermediate (intermediate lymphocytic response and/or lymphoid

nodules in some but not all 4× fields), and weak (sparse

lymphocytic response without lymphoid nodules) (13); and perineural invasion was assessed

separately in this tumor compartment. The worst pattern of

invasion, defined as the least differentiated part of the invasive

margin of tumors, included five categories, namely, pushing border,

finger-like growth, large tumor islands (>15 cells/island),

small tumor islands (<15 cells/island), and tumor satellites ≥1

mm away from the main tumor.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 3-μm TMA

sections. To confirm HPV-negative status, p16INK4A mouse

monoclonal antibody (clone IHC116, GenomeMe, Lab Inc., Richmond,

BC, Canada) was applied at 1:50 dilution, on a Bond Max Autostainer

using BOND Polymer Detection kit. Antigen retrieval was performed

with EDTA (pH 9) for 40 min, followed by primary antibody

(p16INK4A) incubation at 37°C for 30 min. For immune

profiling, CD8 mouse monoclonal antibody (clone C8/144B, Dako,

Glostrup, Denmark) was used at 1:60 dilution. For antigen

retrieval, EDTA (pH 9) was used for 20 min, before primary antibody

incubation at 37°C for 30 min. Staining was performed on a Dako

autostainer using the EnVision™ FLEX+ (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA)

visualization system. PD-L1 was assessed with a mouse monoclonal

antibody (clone 22C3, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 1:100 dilution on

a Dako autostainer by using the EnVision™ FLEX+ visualization

system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). For antigen retrieval, EDTA (pH

9) was performed for 30 min, followed by primary antibody

incubation at 37°C for 30 min. All slides were counterstained with

hematoxylin. Both positive and negative controls were

simultaneously stained.

In regard to immunohistochemical evaluation, PD-L1

expression was assessed in both tumor and immune cells, according

to the guidelines (30). For tumor

cells, PD-L1 positivity was defined as complete and/or partial

circumferential linear cellular membrane staining of any intensity,

as assessed by the tumor proportion score (TPS). Immune cells were

evaluated as the proportion of the tumor area occupied by any

discernible PD-L1 staining of any intensity and the combined

positive score (CPS) was estimated in each case (30). CPS ≥1 was considered positive.

Staining interpretation was performed by two experienced

pathologists (SET, TK). CD8+ cell counts were obtained

from the entire area of each 1.5 mm diameter core. The density of

positive cells was assessed as the ratio of CD8+ cells

per mm2 of core surface area. Average values were used

for tumors represented by multiple cores. Spatial distribution of

CD8+ T cells was assessed by comparing two tissue cores

of each tumor to determine whether cells were evenly distributed,

clustered or concentrated in specific regions or showed different

values between the cores (28). For

p16, strong and diffuse nuclear and/or cytoplasmic positivity in

≥70% of neoplastic cells was used as a cut-off according to

standard guidelines for HNSCC, with a positive result indicating

HPV-related HNSCC (31). As

aforementioned, p16 immunohistochemistry (Fig. S1) was applied to all available

HNSCC cases and HPV-related carcinomas were excluded from the

present study; accordingly, all tumors analyzed here were p16

negative.

Statistical analysis

Histological parameters, categorical and continuous,

were evaluated against clinicopathological patient and tumor

characteristics and against each other. In case of two categorical

variables χ2 and Fisher's tests were applied. In case of

comparing a continuous variable across different groups, the

Kruskal-Wallis(if more than two groups) and the Mann-Whitney (if

two groups) tests were used. In case of post hoc comparisons,

Kruskal Wallis test, followed by Mann-Whitney U test and Bonferroni

correction was applied.

For the assessment of risk factors for OS, the

log-rank test and Cox regression were applied. For multivariable

analyses, we selected risk factors with a P-value lower than 0.2,

which were further filtered by using Akaike's information criterion

for entry into the multivariable model.

The significance level for univariable analyses was

set at 5%, with P<0.05 considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All analyses were conducted in R (v. 4.3.1;

http://www.R.project.org/).

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

Most patients were men, heavy smokers, and diagnosed

with stage III or IV disease. The majority underwent surgical

treatment, while 26.25% received various therapeutic modalities in

the first line setting. Based on tumor location as per

histopathology report, SCC were categorized into oral,

oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal, the two latter

categories being analyzed as one. Twenty-seven cases of local

spread specimens were incorporated in the study. Most tumor tissues

were obtained at disease diagnosis and were surgical specimens.

Seventy-nine of them included the invasive margin of the tumor. The

resection margins were free of carcinoma/high grade dysplasia. All

available clinicopathological data are presented in Table I.

| Table I.Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

patient demographics and clinicopathological data. |

Table I.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

patient demographics and clinicopathological data.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Median age at first

diagnosis, years | 62

(54.23–70.1; |

| (IQR min-max;

range) | 20.9–85.1) |

| Sex (n=248) |

|

|

Female | 31 (12.5) |

|

Male | 217 (87.5) |

| Smoking packs

(n=225) |

|

| No | 25 (11.1) |

| 1-10

pack years | 9 (4.0) |

| 11-20

pack years | 27 (12.0) |

| >20

pack years | 164 (72.9) |

| Alcohol abuse

(n=226) |

|

| No | 68 (30.1) |

|

Mild | 53 (23.5) |

|

Moderate | 41 (18.1) |

|

Heavy | 64 (28.3) |

| Disease stage

(n=229)a |

|

| I | 25 (10.9) |

| II | 27 (11.8) |

|

III | 65 (28.4) |

| IV | 112 (48.9) |

| Adjuvant treatment

(n=242) |

|

| No | 210 (86.8) |

|

Chemo | 1 (0.4) |

| RT | 31 (12.8) |

| First line

treatment (n=240) |

|

| No | 177 (73.8) |

|

Chemo | 38 (15.8) |

|

CT-RT | 7 (2.9) |

| RT | 18 (7.5) |

| Death (n=246) |

|

| No | 59 (24.0) |

|

Yes | 187 (76.0) |

| Tumor site

(n=248) |

|

|

Oral | 35 (14.1) |

|

Oropharyngeal | 30 (12.1) |

|

Laryngohypopharyngeal | 156 (62.9) |

| Local

spreadb | 27 (10.9) |

| Sample status

(n=242) |

|

| First

diagnosis | 202 (83.5) |

|

Pretreatedc | 23 (9.5) |

|

Relapse, naïved | 17 (7.0) |

| Type of specimen

(n=248) |

|

|

Biopsy | 78 (31.5) |

|

Surgical | 170 (68.5) |

Phenotype characteristics

Detailed histopathological and immunophenotypic

characteristics of the examined HNSCC are shown in Table II.

| Table II.Histopathological and

immunohistochemical characteristics of head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma cases. |

Table II.

Histopathological and

immunohistochemical characteristics of head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma cases.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Grade (n=248) |

|

| G1 | 42 (16.9) |

| G2 | 155 (62.5) |

| G3 | 51 (20.6) |

| Grade heterogeneity

(n=248) | 24 (9.7) |

| Tumor variant

(n=248) |

|

|

Keratinizing | 196 (79.0) |

| Non

keratinizing | 52 (21.0) |

| Anaplastic features

(n=248) | 138 (55.6) |

| Cell cannibalism

(n=248) | 139 (56.0) |

| Desmoplastic

stromal reaction (n=222) |

|

|

Fibroblastic | 134 (60.4) |

|

Keloid-like | 27 (12.1) |

|

Loose/myxoid | 61 (27.5) |

| Stromal reaction

heterogeneity (n=222) | 37 (16.7) |

|

Necrosisa (n=248) |

|

|

Absent | 220 (88.7) |

|

Focal | 21 (8.5) |

|

Moderate-extensive | 7 (2.8) |

| Microabscesses

(n=248) | 13 (5.2) |

| Necrosis in

keratinization (n=248) | 68 (27.4) |

| Neutrophils in

necrosis (n=248) | 14 (5.6) |

| Neutrophils in

dyskeratosis (n=248) | 126 (50.8) |

| Perineural

invasionb (n=248) | 12 (4.8) |

| Lymphovascular

invasion (n=248) | 4 (1.6) |

| CD8 heterogeneity

(n=159) | 41 (25.8) |

| PD-L1 status

(n=215) |

|

|

<1 | 190 (88.4) |

|

1-20 | 22 (10.2) |

|

≥20 | 3 (1.4) |

| PD-L1 heterogeneity

(n=215) | 12 (5.6) |

| Lymphocytic host

response in IM (n=79) |

|

|

Weak | 28 (35.4) |

|

Intermediate | 27 (34.2) |

|

Dense | 24 (30.4) |

| Perineural invasion

in IM (n=79) | 9 (11.4) |

| Multinucleated

macrophages (n=248) | 29 (11.7) |

| Median keratin

pearlsa (n=248)

[IQR] | 0 [0, 5] |

| Median

eosinophils/mm2 (n=214) [IQR] | 0.314 [0,

3.88] |

| Median TIL Salgado

density (n=242) | 20.75 |

| [IQR] | [11.15, 32.35] |

| Median

CD8+/mm2 (n=215) [IQR] | 198.05 |

|

| [98.45,

420.37] |

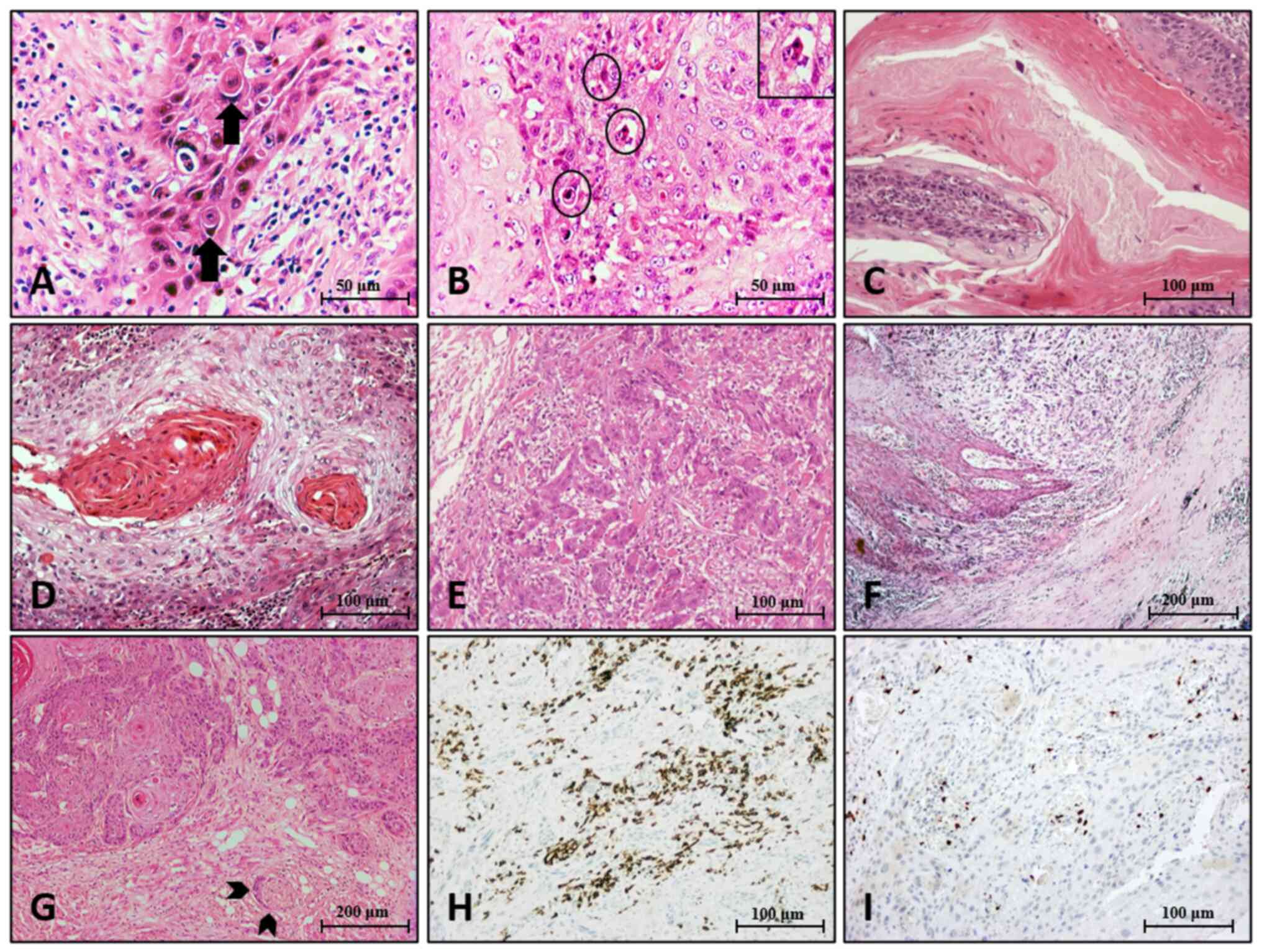

The most prevalent tumor variant was keratinizing of

intermediate grade (G2) with anaplastic features and cell

cannibalism (Fig. 1A). Among the

laryngeal SCC, two were designated as basaloid SCC variants. Two

additional basaloid SCC were found; one located in the oral cavity

and one in the oropharynx. Neutrophils in dyskeratosis (Fig. 1B) were quite common, whereas keratin

pearls in ≥5% of the tumor area, microabscesses, or necrosis in

keratinization (Fig. 1C) were

observed in a minority of tumors. Perineural and lymphovascular

invasion were rare. Grade (Fig. 1D and

E) heterogeneity was observed in a considerable number of

tumors. Specifically, while most of them presented with

intermediate grade (G2), ‘miniscule’ areas with features favoring

either low (G1) or high (G3) grade frequently coexisted. In all

cases with grading heterogeneity, the final grade was assigned

based on the worst component, if it comprised more than 5%.

Accordingly, stromal desmoplastic reaction presented with a variety

of features, from loose myxoid to dense collagenous, even within

the same tumor, in respect of stromal heterogeneity. In such cases,

stroma was characterized based on the predominant pattern.

The infiltrative margin in 63 (79.7%) out of 79

evaluable tumors was characterized by the absence of

keratinization. In the same tumor area, heterogeneous worst pattern

of invasion was identified in 32/79 cases (40.5%) (Fig. 1F); all degrees of lymphocytic host

response density were equally observed, while perineural invasion

(Fig. 1G) was noticed in 11.4% of

the tumors.

With respect to immune cell infiltrates, 10.3% of

tumors exhibited eosinophils >14.2/mm2, while 15% of

tumors had TIL density >50% and/or CD8+

>700/mm2. CD8+ infiltrates were

heterogeneously present in 25.8% of the tumors (Fig. 1H and I). Only 11.6% exhibited any

degree of PD-L1 positivity (Fig.

S1).

Site specificity of generic

histopathological characteristics

Histological characteristics significantly differed

among HNSCC from different anatomical areas, namely,

laryngohypopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and oral carcinomas, as shown

in Table III. Regarding some of

these characteristics, the majority of laryngohypopharyngeal tumors

exhibited anaplastic features and cell cannibalism. Oropharyngeal

tumors featured higher grade and higher rates of tumor necrosis,

while being devoid of eosinophils. In contrast, eosinophils,

keratin pearls, and perineural invasion were more common in oral

carcinomas. In addition, keratinization was prevalent among

laryngohypopharyngeal tumors (P<0.001). Regarding the invasive

margin (Table III), perineural

invasion appeared more frequently in oral and oropharyngeal

tumors.

| Table III.Associations between

clinicopathological variables and tumor site. |

Table III.

Associations between

clinicopathological variables and tumor site.

| Parameter | Oral | Oropharyngeal |

Laryngohypopharyngeal | P-value |

|---|

| Smoking packs, n

(%) | | | | 0.009 |

| No | 6 (24%) | 2 (8.3%) | 17 (11.1%) |

|

|

1-10 | 4 (16%) | 2 (8.3%) | 3 (2%) |

|

|

11-20 | 4 (16%) | 2 (8.3%) | 20 (13.1%) |

|

|

>20 | 11 (44%) | 18 (75.1%) | 113 (73.8%) |

|

| Disease stage |

|

|

| 0.009 |

| I | 8 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (9.9%) |

|

| II | 4 (14.3%) | 4 (16%) | 19 (12.5%) |

|

|

III | 3 (10.7%) | 6 (24%) | 53 (34.9%) |

|

| IV | 13 (46.4%) | 15 (60%) | 65 (42.7%) |

|

| Grade |

|

|

| 0.002 |

| G1 | 12 (34.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 23 (14.7%) |

|

| G2 | 21 (60%) | 15 (50%) | 106 (68%) |

|

| G3 | 2 (5.7%) | 11 (36.7%) | 27 (17.3%) |

|

| Necrosis in

keratinization |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Absent | 34 (97.1%) | 27 (90%) | 97 (62.2%) |

|

|

Present | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (10%) | 59 (37.8%) |

|

| Anaplastic

features |

|

|

| 0.006 |

|

Absent | 21 (60%) | 17 (56.7%) | 55 (35.3%) |

|

|

Present | 14 (40%) | 13 (43.3%) | 101 (64.7%) |

|

| Cell

cannibalism |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Absent | 25 (71.4%) | 18 (60%) | 52 (33.3%) |

|

|

Present | 10 (28.6%) | 12 (40%) | 104 (66.7%) |

|

| Perineural invasion

(entire tumor area) |

|

|

| 0.004 |

|

Absent | 29 (82.9%) | 28 (93.3%) | 152 (97.4%) |

|

|

Present | 6 (17.1%) | 2 (6.7%) | 4 (2.6%) |

|

| Perineural invasion

(invasive margin) |

|

|

| 0.004 |

|

Absent | 11 (64.7%) | 0 (0%) | 59 (96.7%) |

|

|

Present | 6 (35.3%) | 1 (100%) | 2 (3.3%) |

|

| Tumor variant and

cell cannibalism status |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Keratinizing without cell

cannibalism | 20 (26.3%) | 13 (17.1%) | 43 (56.6%) |

|

| Non

keratinizing without cell cannibalism | 5 (26.3%) | 5 (26.3%) | 9 (47.4%) |

|

|

Keratinizing with cell

cannibalism | 9 (8.8%) | 7 (6.9%) | 86 (84.3%) |

|

| Non

keratinizing with cell cannibalism | 1 (4.2%) | 5 (20.8%) | 18 (75%) |

|

| Median keratin

pearls, % of tumor surface (IQR) | 6.31 (8.64) | 3.13 (6.33) | 5.81 (12.92) | 0.034 |

| Median TIL density,

% (IQR) | 22.53 (12.39) | 30.26 (20.71) | 23 (16.3) | 0.265 |

| Median

CD8+/mm2 (IQR) | 395.63

(365.59) | 305.74

(269.88) | 273.58

(281.18) | 0.123 |

| Median

eosinophils/mm2 (IQR) | 15.99 (29.16) | 2.57 (5.09) | 13.51 (74.71) | 0.003 |

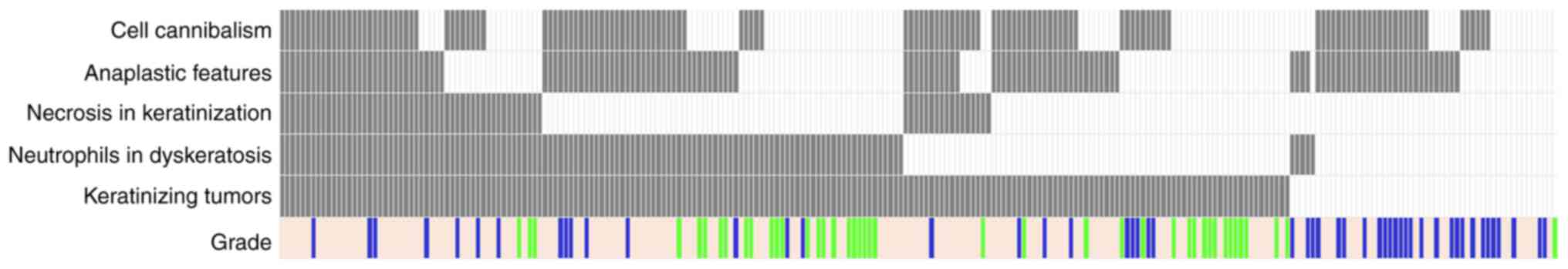

Next, we profiled histological parameters for all

tumors (Fig. 2). By definition,

parameters related to keratinization were identified at

significantly higher rates in keratinizing tumors (grade and

necrosis in keratinization, neutrophils in dyskeratosis; all

P-values <0.001). In comparison, anaplastic features, cell

cannibalism and perineural invasion were almost equally distributed

among tumors with and without keratinization. Modeling parameters

related and not related to keratinization revealed a site-specific

association; that is, concomitant keratinization and cell

cannibalism were rare among oral and oropharyngeal tumors

(P<0.001) (Table III). With

respect to clinical parameters, laryngohypopharyngeal and

oropharyngeal carcinomas were more frequent in heavy smokers

(P=0.009) and in patients with stage III and IV disease (P=0.009).

No further clinicopathological associations were observed.

No associations with tumor site were found for worst

pattern of invasion and lymphocytic host response in the invasive

margin. Similarly, there were no associations for tumor variant,

tumor necrosis, neutrophils in necrosis or in dyskeratosis,

microabscesses, stromal reaction, lymphovascular invasion,

multinucleated macrophages, CD8 and PD-L1 status.

Associations between

clinicopathological parameters and survival

All parameters were examined for their association

with OS at a follow-up period of 26 years (24/4/1997-30/11/2023).

The results of a univariable analysis are presented in Table IV.

| Table IV.Univariable analysis with respect to

OS for the parameters studied in the entire cohort and in the

invasive margin. |

Table IV.

Univariable analysis with respect to

OS for the parameters studied in the entire cohort and in the

invasive margin.

| A, Entire

cohort |

|---|

|

|---|

| Parameter | Cases | Events | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

| 0.102 |

|

Female | 30 | 17 | 1 | - |

|

|

Male | 216 | 164 | 1.51 | (0.92, 2.49) |

|

| Smoking |

|

|

|

| 0.264 |

| No | 25 | 20 | 1 | - |

|

|

Yes | 200 | 147 | 0.76 | (0.47, 1.23) |

|

| Smoking pack years;

only smokers |

|

| 1.03 | (0.88, 1.22) | 0.077 |

| Alcohol abuse |

|

|

|

| <0.001 |

| No | 68 | 44 | 1 | - |

|

|

Mild | 53 | 34 | 0.93 | (0.59, 1.46) |

|

|

Moderate | 41 | 31 | 1.44 | (0.91, 2.28) |

|

|

Heavy | 64 | 58 | 2.60 | (1.73, 3.89) |

|

| Disease stage |

|

|

|

| <0.001 |

| I | 25 | 13 | 1 | - |

|

| II | 25 | 17 | 1.01 | (0.49, 2.11) |

|

|

III | 65 | 38 | 0.83 | (0.44, 1.56) |

|

| IV | 112 | 99 | 2.46 | (1.38, 4.4) |

|

| Tumor site |

|

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Oral | 33 | 25 | 1.57 | (1.01, 2.43) |

|

|

Oropharyngeal | 30 | 21 | 1.39 | (0.87, 2.23) |

|

|

Laryngohypopharyngeal | 156 | 112 | 1 | - |

|

| Local

spread | 27 | 23 | 2.38 | (1.51, 3.75) |

|

| Tumor variant |

|

|

|

| 0.616 |

| Non

keratinizing | 52 | 35 | 1 | - |

|

|

Keratinizing | 194 | 146 | 1.1 | (0.76, 1.59) |

|

| Microabscesses |

|

|

|

| 0.433 |

|

Absent | 233 | 173 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 13 | 8 | 0.75 | (0.37, 1.53) |

|

| Grade |

|

|

|

| 0.567 |

| G1 | 41 | 27 | 1 | - |

|

| G2 | 154 | 119 | 1.22 | (0.8, 1.85) |

|

| G3 | 51 | 35 | 1.3 | (0.78, 2.15) |

|

| Necrosis in

keratinization |

|

|

|

| 0.838 |

|

Absent | 178 | 128 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 68 | 53 | 1.03 | (0.75, 1.43) |

|

| Neutrophils in

dyskeratosis |

|

|

|

| 0.507 |

|

Absent | 120 | 85 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 126 | 96 | 1.10 | (0.82, 1.48) |

|

| Tumor necrosis (%

of tumor surface) |

|

|

|

| 0.147 |

|

Absent | 218 | 158 | 1 | - |

|

|

Focal | 21 | 16 | 1.09 | (0.65, 1.83) |

|

|

Moderate-extensive | 7 | 7 | 2.11 | (0.98, 4.55) |

|

| Neutrophils in

necrosis |

|

|

|

| 0.992 |

|

Absent | 232 | 170 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 14 | 11 | 1.00 | (0.54, 1.85) |

|

| Anaplastic

features |

|

|

|

| 0.804 |

|

Absent | 109 | 81 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 137 | 100 | 0.96 | (0.72, 1.29) |

|

| Cell

cannibalism |

|

|

|

| 0.495 |

|

Absent | 108 | 79 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 138 | 102 | 0.90 | (0.67, 1.21) |

|

| Perineural

invasion |

|

|

|

| 0.095 |

|

Absent | 70 | 47 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 8 | 7 | 1.71 | (0.9, 3.25) |

|

| Multinucleated

macrophages |

|

|

|

| 0.062 |

|

Absent | 217 | 164 | 1 | - |

|

|

Present | 29 | 17 | 0.62 | (0.37, 1.03) |

|

| Age at 1st

diagnosis | 246 | 181 | 1.01 | (1, 1.02) | 0.127 |

| Keratin pearls (%

of tumor surface) | 246 | 181 | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.02) | 0.459 |

| TIL density

(%) | 240 | 177 | 0.99 | (0.99, 1) | 0.279 |

|

Eosinophils/mm2 average | 212 | 154 | 1.00 | (1, 1) | 0.323 |

| CD8+/

mm2 average | 214 | 157 | 1.00 | (1, 1) | 0.184 |

| CD8

heterogeneity |

|

|

|

| 0.030 |

|

Homogeneous | 118 | 90 | 1 | - |

|

|

Heterogeneous | 40 | 25 | 0.61 | (0.39, 0.96) |

|

|

| B, Invasive

margin |

|

|

Parameter | Cases | Events | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| Lymphocytic host

response | 78 | 54 | 0.56 | (0.39, 0.81) | 0.002 |

| Perineural invasion

present | 8 | 7 | 2.52 | (1.12, 5.66) | 0.025 |

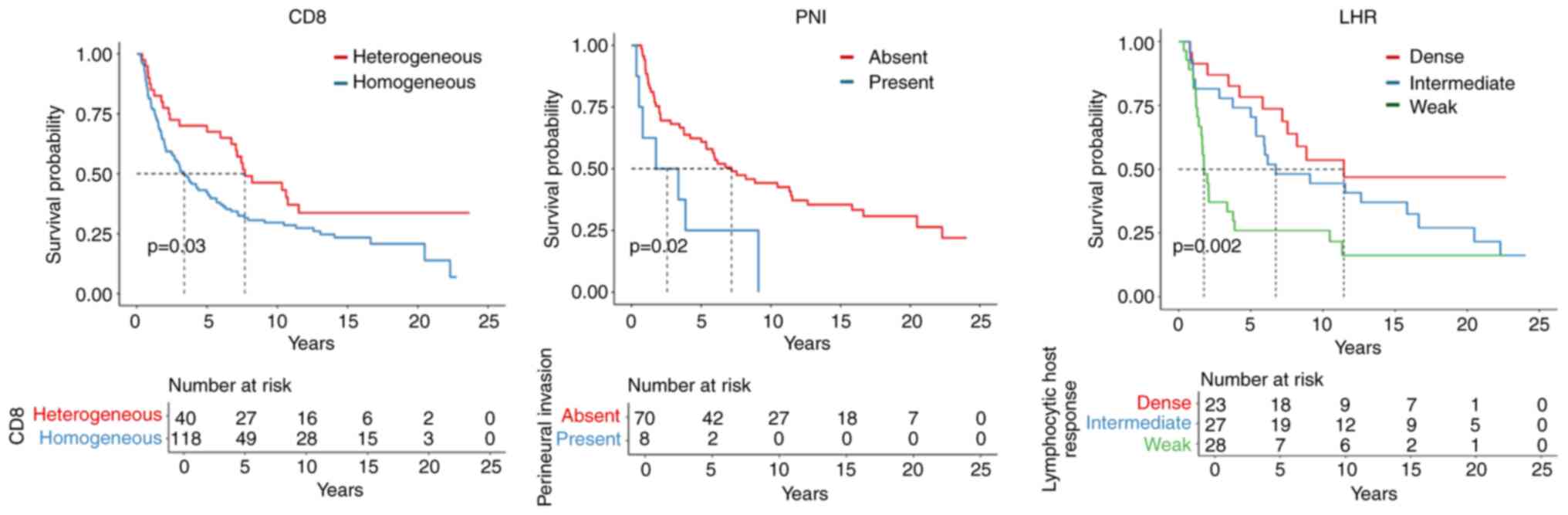

Alcohol consumption and disease stage had

significant impacts on patient OS. CD8+ heterogeneity

(P=0.038) was associated with a favorable prognosis, whereas

perineural invasion in the invasive margin (P=0.025) appeared to be

an adverse prognosticator. In addition, weak lymphocytic

infiltrates in the invasive margin had a negative impact on OS

(Fig. 3).

A subgroup analysis was conducted by separating

samples into three distinct groups based on the primary tumor site:

oral cavity, oropharynx, and laryngohypopharynx. This additional

analysis showed that heavy alcohol abuse and advanced disease stage

were significantly associated with worse OS in

laryngohypopharyngeal tumors (P<0.001). Furthermore, within the

same tumor site, perineural invasion (entire cohort and invasive

margin, P=0.007) and weak lymphocytic host response in the invasive

margin (P=0.028) were also significantly linked to poorer OS. In

oral cavity SCC, weak lymphocytic host response in the invasive

margin (P=0.052) was associated with an adverse prognosis. Detailed

results of these findings are presented in Table SI, Table SII, Table SIII and prognostic histological

features by site are illustrated in Fig. S2.

A multivariable analysis (Table V) revealed that alcohol abuse,

disease stage, and perineural invasion were independently

associated with unfavorable OS. In the invasive margin, weak

lymphocytic infiltrates and perineural invasion remained

independent predictors for unfavorable OS. No additional

associations between the clinicopathological parameters studied and

OS were observed. Based on these results, we recommend

histopathological parameters that should be included, among others,

in the histological reports, in each case of HNSCC (Table VI).

| Table V.Multivariable analysis with respect

to OS for the parameters studied in the entire cohort and in the

invasive margin. |

Table V.

Multivariable analysis with respect

to OS for the parameters studied in the entire cohort and in the

invasive margin.

| A, Entire

cohort |

|---|

|

|---|

| Parameter | Cases | Events | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Alcohol abuse | 226 | 167 | 1.27 | (0.95, 1.7) | 0.105 |

| Disease stage | 227 | 168 | 1.67 | (1.11, 2.51) | 0.013 |

| Perineural invasion

present | 8 | 7 | 2.81 | (1.05, 7.49) | 0.039 |

|

| B, Invasive

margin |

|

|

Parameter | Cases | Events | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| Lymphocytic host

response | 80 | 56 | 0.58 | (0.4, 0.83) | 0.003 |

| Perineural invasion

present | 8 | 7 | 2.2 | (0.97, 4.98) | 0.060 |

| Table VI.Key histopathological parameters

recommended for routine reporting regardless of head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma anatomic site. |

Table VI.

Key histopathological parameters

recommended for routine reporting regardless of head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma anatomic site.

| Category | Parameter |

Assessment/reporting |

|---|

| Entire tumour | Histological

typea | Conventional

SCC/other (specify) |

|

| Perineural

invasiona | Present/absent |

|

| TIL density | % of all stromal

mononuclear cells (including lymphocytes and plasma cells) |

| Invasive front | Lymphocytic host

response |

Weak/moderate/dense |

|

| Perineural

invasion | Present/absent |

|

Immunohistochemistry | p16

immunohistochemistrya |

Positive/negative |

|

| PD-L1

immunohistochemistry | CPS |

Discussion

Grading is one of the primary prognostic factors in

malignant neoplasms; however, it does not seem to be an accurate

prognosticator for HNSCC, possibly due to the heterogeneity of

cytomorphological and architectural features in a pattern

previously described as ‘hybrid SCC variant’ (19). Accordingly, we identified limited

areas of keratinization in non-keratinizing tumors and anaplastic

cells in otherwise well-differentiated carcinomas. Our observation

of heterogeneity beyond neoplastic cells in microenvironmental

components, such as stroma and TILs/CD8+ cells, supports

the view of HNSCC as heterogeneous ecosystems.

The assessment of routinely reported histological

features may assist in developing an optimal prognostic tool in

line with the ongoing effort to establish multifactorial grading

systems (5,32). However, we first need to identify

which of the histological parameters are risk factors and whether

they are site-specific. In this study, as expected, keratinizing

tumors exhibited features related to keratinization, and

non-keratinizing tumors were mainly characterized as high-grade.

Anaplastic features, cell cannibalism, and perineural invasion were

observed independent of tumor variant. Comparisons between the SCC

of different anatomic locations revealed site-specific

characteristics. In oral SCC, high grade was not prevalent, and a

common feature was perineural invasion, as previously reported

(33). Eosinophil density was

higher, as well (34). Necrosis in

keratinization, anaplastic cells, and cell cannibalism were mainly

present in laryngohypopharyngeal SCC. Interestingly, cell

cannibalism and anaplastic features were relatively common in

laryngohypopharyngeal SCC, even in low-grade tumors, which is in

agreement with previous reports (23). Of note, the literature contains no

similar comparative morphological studies based on the HNSCC

anatomical site and the observed differences could be used in

developing site-specific prognostic profiling tools.

In addition, along the invasive margin, perineural

invasion and weak lymphocytic host response were adverse

prognosticators independently of the anatomical site. Hence, both

parameters should be included in all HNSCC histopathological

reporting guidelines, not only in oral carcinomas. Perineural

invasion proved to be an independent prognosticator in this study,

regardless of nerve diameter and intratumoral localization, in line

with previous publications (35,36).

There are ongoing studies focusing on the spatial

heterogeneity of the immune cells found in the tumor

microenvironment with potential therapeutic implications (37–40).

The observed heterogeneity of CD8+ T-cell distribution

has been previously mentioned in HNSCC (41,42)

without any reference to its prognostic relevance. The association

of heterogeneous CD8+ infiltrates with OS described in

this paper seems worth further investigation in terms of its

therapeutic implications, particularly with respect to immune

checkpoint inhibitors. In our series, PD-L1 evaluation showed no

significant association with OS, a finding in agreement with

previously published data (43). It

is emphasized, however, that only a minority of our cases showed

PD-L1 positivity, in contrast to former studies (44), raising concerns about its accurate

evaluation on TMAs or small biopsy specimens (45).

Recent AI pipelines that fuse histology with genomic

data have already achieved prognostic accuracy in other solid

tumors (46) and illustrate the

potential for similar multimodal models in HNSCC. Digital pathology

systems leverage image analysis algorithms and machine learning to

identify and quantify microscopic features with greater precision

than the standard evaluation (47).

Algorithms can be trained to recognize characteristic patterns of

LHR-IM and PNI by analyzing H&E-stained slides and even to

identify subtle changes in histology, possibly missed by

pathologists (48) or to determine

the clinical significance of spatial distribution of TILs (49). Machine learning models can be

trained on annotated datasets of HNSCC, regarding perineural

invasion, the number of nerves, the size of nerves or the different

patterns of LHR-IM (48,49). In addition, by using these tools,

the interobserver variability is reduced on morphological and

immunohistochemical grounds (50),

which is crucial with predictive biomarker evaluation, such as

PD-L1 CPS. In this context, the performance of these models may

exceed that of experienced pathologists.

One of the limitations of this study is the

inclusion of both biopsy and surgical material, as well as the

accurate representation of histologic characteristics in small

biopsy samples. Biopsy material was more common in oropharyngeal

tumors. In addition, histological parameters were mainly examined

in whole sections, whereas immunohistochemical parameters were

examined only on TMA sections. Further, site-specific subgroup

analysis for single or profiled parameters in terms of OS was not

possible due to the imbalanced respective group sizes. Male

predominance may affect the conclusions of this study due to

sex-related biological differences. Gender-specific

histopathological parameters with potential clinical value weren't

investigated and future studies examining sex as a potential

modifier of prognostic outcomes in HNSCC are needed. Finally, the

lack of HPV-positive tumors should be regarded as an additional

limitation.

In conclusion, based on our findings, it seems that

the malignant potential of HNSCC is reflected in several tumor

biology-related parameters, such as CD8+ spatial

heterogeneity, tumor center and/or invasive margin perineural

invasion and LHR-IM. Furthermore, perineural invasion and LHR-IM

are confirmed as independent histological risk factors in HNSCC.

Integrating the above parameters in pathology reports may provide

more accurate prognostic information for patients with HNSCC than

the routinely assessed histologic grade. The herein presented

site-specific and tumor compartment histological parameters may be

included in larger studies with deep learning approaches, in order

to enable revising histologic grade in HNSCC in a clinically

meaningful way, as required in the context of personalized

diagnostics.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Maria Moschoni

(data coordinator of HeCOG) for administrative support.

Funding

The study is part of the NCR-17-12885 project funded by Astra

Zeneca and conducted by HeCOG. It was also partially supported by a

Hellenic Society of Medical Oncology (HeSMO) grant (grant no.

HE_TR5/25). The funders had no role in study design, data

collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the

manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SET, VK, GK, PH, GF and TK conceptualized and

designed the study, performed the formal analysis and wrote the

original draft; KM, SP, KV, SC, AP, PH and GF collected and

reviewed clinical and histopathological data. GF and SC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients for the use of their data and biological material for

research purposes. The protocol was approved by the Bioethics

Committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of

Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine (approval no.

5/18.12.2019).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HeCOG

|

Hellenic Cooperative Oncology

Group

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin & eosin

|

|

HNSCC

|

head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma

|

|

HPV

|

human papilloma virus

|

|

IM

|

invasive margin

|

|

IQR

|

interquartile range

|

|

LHR

|

lymphocytic host response

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PNI

|

perineural invasion

|

|

SCC

|

squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

TIL

|

tumor infiltrating lymphocyte

|

|

TMA

|

tissue microarray

|

References

|

1

|

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D,

Mathers C and Parkin DM: Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in

2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 127:2893–2917. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery

L, Pineros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I and Bray F: Global cancer

observatory: Cancer today. International Agency for Research on

Cancer. (Lyon, France). 2020.

|

|

3

|

Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui

VWY, Bauman JE and Grandis JR: Head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6:922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Aupérin A: Epidemiology of head and neck

cancers: An update. Curr Opin Oncol. 32:178–186. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata

T and Slootweg PJ: WHO classification of head and neck tumours.

International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017

|

|

6

|

Lewis JS Jr, Beadle B, Bishop JA, Chernock

RD, Colasacco C, Lacchetti C, Moncur JT, Rocco JW, Schwartz MR,

Seethala RR, et al: Human papillomavirus testing in head and neck

carcinomas: Guideline from the college of american pathologists.

Arch Pathol Lab Med. 142:559–597. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

World Health Organization (WHO), . WHO

Classification of Head and Neck Tumors. 2023.

|

|

8

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN), . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and

Neck Cancers. 2025.

|

|

9

|

Liu FL, Zhang ZC, Zhou SL, Liu XL and Xu

W: Unlocking the therapeutic potential of LncRNA BLACAT1 in

hypopharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Discov Med. 36:546–558. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu Z, Zhao Z, Xie L, Xiao Z, Li M, Li Y

and Luo T: Proteomic analysis reveals chromatin remodeling as a

potential therapeutical target in neuroblastoma. J Transl Med.

23:2342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Elmusrati A, Wang J and Wang CY: Tumor

microenvironment and immune evasion in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Int J Oral Sci. 13:242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bryne M, Jenssen N and Boysen M:

Histological grading in the deep invasive front of T1 and T2

glottic squamous cell carcinomas has high prognostic value. Virch

Arch. 427:277–281. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Brandwein-Gensler M, Smith RV, Wang B,

Penner C, Theilken A, Broughel D, Schiff B, Owen RP, Smith J, Sarta

C, et al: Validation of the histologic risk model in a new cohort

of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg

Pathol. 34:676–688. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fountzilas G, Ciuleanu E, Bobos M,

Kalogera-Fountzila A, Eleftheraki AG, Karayannopoulou G,

Zaramboukas T, Nikolaou A, Markou K, Resiga L, et al: Induction

chemotherapy followed by concomitant radiotherapy and weekly

cisplatin versus the same concomitant chemoradiotherapy in patients

with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A randomized phase II study

conducted by the hellenic cooperative oncology group (HeCOG) with

biomarker evaluation. Ann Oncol. 23:427–435. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Krikelis D, Bobos M, Karayannopoulou G,

Resiga L, Chrysafi S, Samantas E, Andreopoulos D, Vassiliou V,

Ciuleanu E and Fountzilas G: Expression profiling of 21

biomolecules in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinomas of

Caucasian patients. BMC Clin Pathol. 13:12013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fountzilas G, Psyrri A, Giannoulatou E,

Tikas I, Manousou K, Rontogianni D, Ciuleanu E, Ciuleanu T, Resiga

L, Zaramboukas T, et al: Prevalent somatic BRCA1 mutations shape

clinically relevant genomic patterns of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in

Southeast Europe. Int J Cancer. 142:66–80. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hendry S, Salgado R, Gevaert T, Russell

PA, John T, Thapa B, Christie M, van de Vijver K, Estrada MV,

Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al: Assessing tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes in solid tumors: A practical review for pathologists

and proposal for a standardized method from the international

immunooncology biomarkers working group: Part 1: Assessing the host

immune response, TILs in invasive breast carcinoma and ductal

carcinoma in situ, metastatic tumor deposits and areas for further

research. Adv Anat Pathol. 24:235–251. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang D, He W, Wu C, Tan Y, He Y, Xu B,

Chen L, Li Q and Jiang J: Scoring system for tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes and its prognostic value for gastric cancer. Front

Immunol. 10:712019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chernock RD: Morphologic features of

conventional squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx:

‘Keratinizing’ and ‘nonkeratinizing’ histologic types as the basis

for a consistent classification system. Head Neck Pathol. 6 (Suppl

1):S41–S47. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR,

Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR,

Sullivan DC, et al: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Edition.

Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: pp. 91–156.

2018

|

|

21

|

Pollheimer MJ, Kornprat P, Lindtner RA,

Harbaum L, Schlemmer A, Rehak P and Langner C: Tumor necrosis is a

new promising prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. Human Pathol.

41:1749–1757. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC and Perkins

JA: Robbins basic pathology. 10th Edition. Elsevier; Amsterdam,

Netherlands: pp. 1932017

|

|

23

|

Almangush A, Mäkitie AA, Hagström J,

Haglund C, Kowalski LP, Nieminen P, Coletta RD, Salo T and Leivo I:

Cell-in-cell phenomenon associates with aggressive characteristics

and cancer-related mortality in early oral tongue cancer. BMC

Cancer. 20:8432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jiang Z, Chen Z, Xu Y, Li H, Li Y, Peng L,

Shan H, Liu X, Wu H, Wu L, et al: Low-frequency ultrasound

sensitive piezo1 channels regulate keloid-related characteristics

of fibroblasts. Adv Sci. 11:e23054892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ueno H, Kanemitsu Y, Sekine S, Ishiguro M,

Ito E, Hashiguchi Y, Kondo F, Shimazaki H, Mochizuki S, Kajiwara Y,

et al: Desmoplastic pattern at the tumor front defines

poor-prognosis subtypes of colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol.

41:1506–1512. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine

N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, Wienert S, Van den Eynden G, Baehner FL,

Penault-Llorca F, et al: The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: Recommendations by an

international TILs working group 2014. Ann Oncol. 26:259–271. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hendry S, Salgado R, Gevaert T, Russell

PA, John T, Thapa B, Christie M, van de Vijver K, Estrada MV,

Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al: Assessing tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes in solid tumors: A practical review for pathologists

and proposal for a standardized method from the international

immuno-oncology biomarkers working group: Part 2: TILs in melanoma,

gastrointestinal tract carcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinoma

and mesothelioma, endometrial and ovarian carcinomas, squamous cell

carcinoma of the head and neck, genitourinary carcinomas, and

primary brain tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 24:311–335. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Koletsa T, Kotoula V, Koliou GA, Manousou

K, Chrisafi S, Zagouri F, Sotiropoulou M, Pentheroudakis G,

Papoudou-Bai A, Christodoulou C, et al: Prognostic impact of

stromal and intratumoral CD3, CD8 and FOXP3 in adjuvantly treated

breast cancer: Do they add information over stromal

tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte density? Cancer Immunol Immunother.

69:1549–1564. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Brandwein-Gensler M, Teixeira MS, Lewis

CM, Lee B, Rolnitzky L, Hille JJ, Genden E, Urken ML and Wang BY:

Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Histologic risk assessment, but not

margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease-free and

overall survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:167–178. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Agilent Technologies Inc, . PD-L1 IHC 22C3

pharmDx Interpretation Manual-Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

(HNSCC). Santa Clara; CA, USA: pp. 1–72. https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/29314_22c3_pharmDx_hnscc_interpretation_manual_us.pdfApril

2–2024

|

|

31

|

Seethala RR, Baras A, Baskovich BW,

Birdsong GG, Fitzgibbons PL, Khoury JD and Schneider F: Head and

Neck Biomarker Reporting Template. Version 2.0.0.0. College of

American Patologists. 1–6. 2021.

|

|

32

|

Almangush A, Mäkitie AA, Triantafyllou A,

de Bree R, Strojan P, Rinaldo A, Hernandez-Prera JC, Suárez C,

Kowalski LP, Ferlito A and Leivo I: Staging and grading of oral

squamous cell carcinoma: An update. Oral Oncol. 107:1047992020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Schmitd LB, Scanlon CS and D'Silva NJ:

Perineural invasion in head and neck cancer. J Dental Res.

97:742–750. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sharma HD, Mahadesh J, Monalisa W,

Gopinathan PA, Laxmidevi BL and Sanjenbam N: Quantitative

assessment of tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia and nuclear

organizing region activity to validate the significance of the

pattern of invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A

retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 25:258–265. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Binmadi N, Alsharif M, Almazrooa S,

Aljohani S, Akeel S, Osailan S, Shahzad M, Elias W and Mair Y:

Perineural invasion is a significant prognostic factor in oral

squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Diagnostics (Basel). 13:33392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang Q, Huang Y, Chen C, Zhang Y, Zhou J,

Xie C, Lu M, Xiong Y, Fang D, Yang Y, et al: Prognostic impact of

lymphovascular and perineural invasion in squamous cell carcinoma

of the tongue. Sci Rep. 13:38282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yuan Y: Spatial heterogeneity in the tumor

microenvironment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a0265832016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK,

Berger A, Lagorce C, Lugli A, Zlobec I, Hartmann A, Bifulco C, et

al: Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the

classification of malignant tumours. J Pathol. 232:199–209. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang XM, Song LJ, Shen J, Yue H, Han YQ,

Yang CL, Liu SY, Deng JW, Jiang Y, Fu GH, et al: Prognostic and

predictive values of immune infiltrate in patients with head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 82:104–112. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Almangush A, De Keukeleire S, Rottey S,

Ferdinande L, Vermassen T, Leivo I and Mäkitie AA:

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck cancer: Ready for

prime time? Cancers (Basel). 14:15582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Balermpas P, Michel Y, Wagenblast J, Seitz

O, Weiss C, Rödel F, Rödel C and Fokas E: Tumour-infiltrating

lymphocytes predict response to definitive chemoradiotherapy in

head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 110:501–509. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chatzopoulos K, Kotoula V, Manoussou K,

Markou K, Vlachtsis K, Angouridakis N, Nikolaou A, Vassilakopoulou

M, Psyrri A and Fountzilas G: Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and

CD8+ T cell subsets as prognostic markers in patients with

surgically treated laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck

Pathol. 14:689–700. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yang WF, Wong MCM, Thomson PJ, Li KY and

Su YX: The prognostic role of PD-L1 expression for survival in head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 86:81–90. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Crosta S, Boldorini R, Bono F, Brambilla

V, Dainese E, Fusco N, Gianatti A, L'Imperio V, Morbini P and Pagni

F: PD-L1 testing and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck:

A multicenter study on the diagnostic reproducibility of different

protocols. Cancers (Basel). 13:2922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

De Keukeleire SJ, Vermassen T, Deron P,

Huvenne W, Duprez F, Creytens D, Van Dorpe J, Ferdinande L and

Rottey S: Concordance, correlation, and clinical impact of

standardized PD-L1 and TIL scoring in SCCHN. Cancers (Basel).

14:24312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

He B, Wang L, Zhou W, Liu H, Wang Y, Lv K

and He K: A fusion model to predict the survival of colorectal

cancer based on histopathological image and gene mutation. Sci Rep.

15:96772025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Baxi V, Edwards R, Montalto M and Saha S:

Digital pathology and artificial intelligence in translational

medicine and clinical practice. Mod Pathol. 35:23–32. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lee LY, Yang CH, Lin YC, Hsieh YH, Chen

YA, Chang MD, Lin YY and Liao CT: A domain knowledge enhanced yield

based deep learning classifier identifies perineural invasion in

oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 12:9515602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Abousamra S, Gupta R, Hou L, Batiste R,

Zhao T, Shankar A, Rao A, Chen C, Samaras D, Kurc T and Saltz J:

Deep learning-based mapping of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in

whole slide images of 23 types of cancer. Front Oncol.

11:8066032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Badve S, Kumar GL, Lang T, Peigin E, Pratt

J, Anders R, Chatterjee D, Gonzalez RS, Graham RP, Krasinskas AM,

et al: Augmented reality microscopy to bridge trust between AI and

pathologists. NPJ Precis Oncol. 9:1392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|