Introduction

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) accounts for

80–85% of thyroid malignancies and typically carries an excellent

prognosis (>90% 10-year survival rate) (1). However, 10–15% of patients develop

aggressive disease with recurrence or distant metastases,

underscoring the need for precise risk stratification. Radioactive

iodine (RAI) therapy is essential for treating persistent or

metastatic PTC, effectively ablating residual thyroid tissue and

iodine-absorbing metastases (2).

Although there is strong evidence linking tumor biology to

suboptimal responses to RAI therapy, it is still challenging for

clinicians to identify specific patients with poor therapeutic

outcomes. Additionally, while several studies have explored

prognostic factors in PTC, including age, tumor size, lymph node

involvement and molecular markers [such as B-Raf proto-oncogene

serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) and telomerase reverse transcriptase

(TERT) mutations], an individualized nomogram to predict outcomes

after RAI therapy is still lacking (3–6).

Nomograms are powerful predictive models that have

recently been developed and widely used in oncology to provide

personalized risk estimates on the basis of multiple clinical and

pathological variables. In PTC, a nomogram could enhance risk

stratification by quantifying the likelihood of treatment failure,

recurrence or disease-specific survival following RAI therapy. For

instance, Valero et al (7)

developed a nomogram for survival outcomes in well-differentiated

thyroid cancer, while Wei et al (8) constructed a model based on clinical

features and gene mutations to predict lymph node metastasis.

However, these models do not incorporate dynamic post-treatment

biomarkers or focus on the critical post-RAI phase. Similarly, Wen

et al (9) proposed a

nomogram incorporating pre-ablation ratio for predicting

therapeutic response, yet its applicability is limited to

intermediate- and high-risk patients. In addition, existing

prognostic models often focus on preoperative or postoperative

factors, but not those after RAI injection (10,11).

Thyroglobulin (Tg) serves as a pivotal tumor marker

for PTC, with serum levels directly correlating with disease

prognosis. However, Tg-based predictive systems face significant

limitations, including requirements for long-time monitoring of

unreliable measurements and interference from non-malignant thyroid

tissue. A major drawback is the suppression of Tg levels in

patients with Tg antibodies (TgAb), which affects measurement

accuracy (12). While one study has

proposed TgAb levels as an alternative predictive factor in

TgAb-positive patients, their efficacy remains unconfirmed and

long-time monitoring proves equally unreliable (13). Given these challenges, developing a

predictive model that does not rely on Tg levels has substantial

clinical value. Therefore, the present study attempted to develop

and validate a nomogram based on readily available clinical

features to predict prognostic factors in patients with PTC after

RAI treatment. By incorporating demographic, pathological and

treatment-related variables, this model may provide clinicians with

information to individualize follow-up, treatment and counseling

after RAI treatment. The findings may aid in achieving more

personalized PTC treatment in the era of personalized medicine.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study protocol and data collection were approved

by the Ethical Board of the Second Hospital of Shandong University

(Jinan, China). All the subjects were informed about the

Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for research with human

subjects. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics

Committee of the Second Hospital of Shandong University (approval

no. KYLL-2022LW077).

A total of 3,681 consecutive patients with

pathologically confirmed PTC were retrospectively reviewed, and all

these patients received RAI therapy at the Second Hospital of

Shandong University between May 2016 and April 2022. The inclusion

criteria to select the subjects were: i) Patients with PTC

confirmed by pathology, all of whom had undergone thyroidectomy;

and ii) patients with PTC scheduled for RAI therapy. A total of

2,608 patients with the following criteria were excluded: i) Peak

thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level <30 µIU/ml (n=193); ii)

lack of complete clinical follow-up information on RAI therapy

(n=927); and iii) insufficient or unavailable mutation analysis

results (n=1,488). Finally, 1,073 patients were enrolled (319 men

and 754 women; mean age, 42.26±12.11 years; age range, 18–70

years), and the overall median follow-up time was 42 months

(interquartile range, 38–62 months) after initial RAI therapy.

Patients were managed according to American Thyroid

Association (ATA) guidelines (2015) (14). Clinical and pathological

characteristics were retrospectively analyzed from medical records,

including tumor subtype, multifocality, peripheral tissue invasion,

BRAFV600E mutation status, coexisting Hashimoto

thyroiditis (HT), Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) stage (classified per

the AJCC 8th edition staging system), lymph node metastasis ratio

(LNR), Tg levels, TgAb levels and TSH levels (15). All pathological assessments were

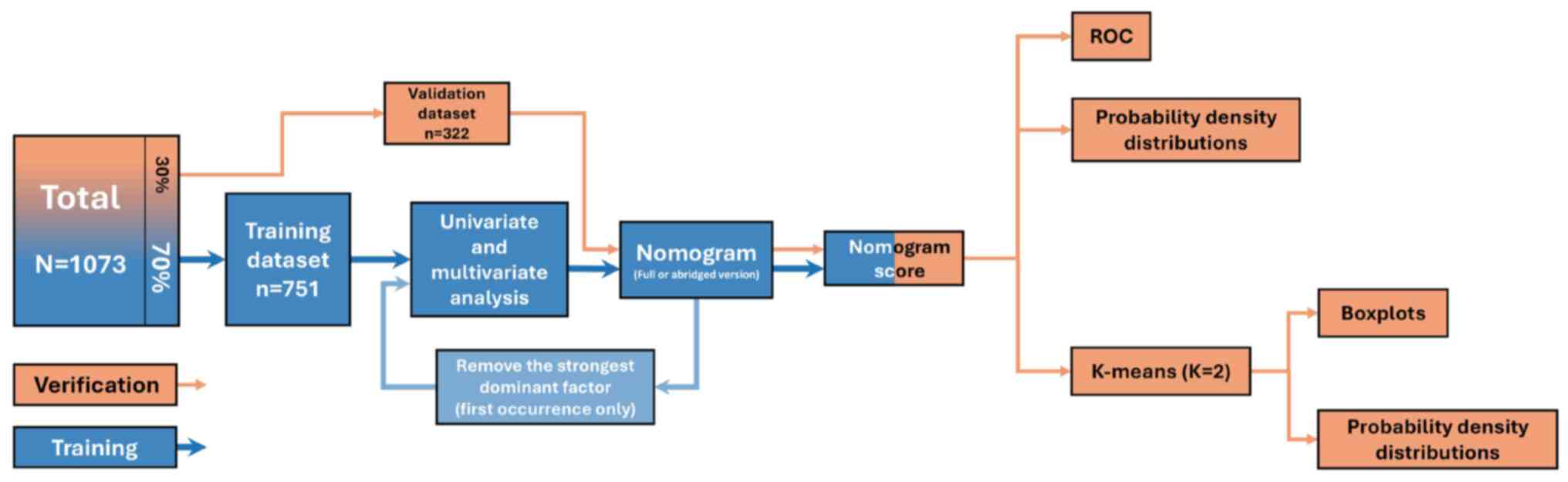

conducted by board-certified pathologists. The flowchart of the

study cohort is presented in Fig.

1.

Management and follow-up

assessment

Within 2–3 months postoperatively, patients

underwent RAI therapy based on their recurrence risk

stratification. The initial administered activity of iodine-131

ranged from 2.96 to 5.55 GBq (80–150 mCi). Prior to RAI therapy,

all patients prepared with 4 weeks of levothyroxine withdrawal and

a low-iodine diet, proceeding only when TSH levels were >30

µIU/ml. On the day of RAI administration, serological parameters,

including TSH, pre-ablation stimulated Tg and TgAb, were measured.

Post-therapeutic whole-body scintigraphy was performed at 72 h

post-RAI, supplemented by single-photon emission computed

tomography/computed tomography for equivocal thyroid bed or nodal

uptake. Patients were routinely followed up every 3–6 months with

neck ultrasonography and serum assays (Tg, TgAb and TSH).

Persistent disease prompted additional RAI therapies (6–12-month

intervals), guided by treatment response. Final outcomes were

determined based on the last documented clinical and biochemical

status during follow-up.

Evaluation of the response to RAI

therapy

On the basis of these data, the clinical outcomes of

RAI therapy were classified as excellent response (ER),

indeterminate response (IDR), biochemical incomplete response (BIR)

and structural incomplete response (SIR). ER was defined as

negative imaging with either suppressed Tg ≤0.2 ng/ml or

TSH-stimulated Tg ≤1 ng/ml and the absence of TgAb. IDR was defined

as negative imaging with suppressed Tg at 0.2–1 ng/ml, stimulated

Tg at 1–10 ng/ml or TgAb kept stable or declining. BIR was defined

as negative imaging with suppressed Tg >1 ng/ml, stimulated Tg

>10 ng/ml or rising TgAb levels. SIR was defined as patients

with structural or functional evidence of disease with any Tg and

TgAb levels (14). A non-ER (NER)

included IDR, BIR and SIR. In the present study, BIR or SIR was

defined as indicative of a poor clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Normality was

assessed via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Parametric data were analyzed

with unpaired Student's t test, whereas non-parametric data were

evaluated via the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are

summarized as n (%), with associations analyzed via the

χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Group allocation was

performed via simple random sampling. Univariate and multivariate

logistic regression models were used to screen for prognostic risk

factors. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

were calculated through multivariable logistic regression to

compare recurrence risk among independent predictors. A nomogram

model was constructed on the basis of multivariate regression

results to quantify and visualize risk factors. Model calibration

was assessed via calibration curves, and predictive accuracy was

quantified via the mean absolute error (MAE). Model validation was

performed through probability density distributions and receiver

operating characteristic curve analysis, with risk stratification

achieved via the K-means clustering algorithm. For quantitative

visualization, boxplots are used to demonstrate data dispersion,

and probability density distributions are used to assess central

tendency. All analyses adopted a two-sided significance threshold

of P<0.05 to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Statistical computations were performed in SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp.),

while regression modeling, nomogram construction and visualization

were implemented in RStudio (version 4.3.1; http://www.R-project.org/). The rms (https://cran.r-project.org/package=rms),

ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org), dplyr (https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr), haven

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=haven), tidyr

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=tidyr), tibble

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=tibble), patchwork

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=patchwork), scales

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=scales) and magick

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=magick) packages

were used.

Results

Baseline characteristics and

comparative analysis between the training and validation

datasets

The study analyzed 1,073 patients with PTC treated

with RAI therapy, divided into the training (n=751) and validation

(n=322) datasets. The overall cohort had a female predominance

(70.3%, n=754), with a high rate of BRAFV600E mutation

(66.9% positive) and metastasis (M) stage M1 (8.8%). No significant

differences were found in most baseline characteristics between

datasets, except TgAb positivity (P=0.023) and primary tumor (T)

stage (P=0.034). In the cohort, 132 patients (12.3%) were

TgAb-positive. Notably, the clinicopathological profiles, including

age, sex distribution, tumor subtype composition, multifocality,

tumor size, capsule invasion, extrathyroidal extension,

BRAFV600E mutation status, coexisting HT, regional lymph

node (N) stage, M stage, LNR, pre-ablation TSH levels, Tg levels,

and 6-month or 3-year responses were well-balanced across both

datasets (all P>0.05), supporting the robustness of the random

allocation and the validity of subsequent model training and

testing (Table I).

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of patients

with papillary thyroid carcinoma in the training and validation

cohorts. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of patients

with papillary thyroid carcinoma in the training and validation

cohorts.

|

Characteristics | Total

(n=1,073) | Training dataset

(n=751) | Validation dataset

(n=322) | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age ± SD,

years | 42.26±12.11 | 42.14±12.10 | 42.56±12.15 | 0.773 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 319 (29.7) | 226 (30.1) | 93 (28.9) | 0.691 |

|

Female | 754 (70.3) | 525 (69.9) | 229 (71.1) |

|

| Subtypes, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Classic | 901 (84.0) | 631 (84.0) | 270 (83.9) | 0.37 |

| FV | 131 (12.2) | 95 (12.6) | 36 (11.2) |

|

|

TCV | 41 (3.8) | 25 (3.3) | 16 (5.0) |

|

| Multifocality, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| No | 453 (42.2) | 319 (42.5) | 134 (41.6) | 0.793 |

|

Yes | 620 (57.8) | 432 (57.5) | 188 (58.4) |

|

| Tumor size,

cma | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 0.604 |

| Capsule invasion, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| No | 454 (42.3) | 318 (42.3) | 136 (42.2) | 0.974 |

|

Yes | 619 (57.7) | 433 (57.7) | 186 (57.8) |

|

| Extrathyroidal

invasion, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| No | 508 (47.3) | 356 (47.4) | 152 (47.2) | 0.952 |

|

Yes | 565 (52.7) | 395 (52.6) | 170 (52.8) |

|

| BRAF, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 355 (33.1) | 253 (33.7) | 102 (31.7) | 0.521 |

|

Positive | 718 (66.9) | 498 (66.3) | 220 (68.3) |

|

| HT, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| No | 875 (81.5) | 609 (81.1) | 266 (82.6) | 0.557 |

|

Yes | 198 (18.5) | 142 (18.9) | 56 (17.4) |

|

| T stage, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Tx | 35 (3.3) | 21 (2.8) | 14 (4.3) | 0.034 |

| T1 | 616 (57.4) | 424 (56.5) | 192 (59.6) |

|

| T2 | 120 (11.2) | 76 (10.1) | 44 (13.7) |

|

| T3 | 235 (21.9) | 181 (24.1) | 54 (16.8) |

|

| T4 | 67 (6.2) | 49 (6.5) | 18 (5.6) |

|

| N stage, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Nx/N0 | 72 (6.7) | 53 (7.1) | 19 (5.9) | 0.466 |

|

N1a | 487 (45.4) | 347 (46.2) | 140 (43.5) |

|

|

N1b | 514 (47.9) | 351 (46.7) | 163 (50.6) |

|

| LNR, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

<5 | 541 (50.4) | 384 (51.1) | 157 (48.8) | 0.476 |

| ≥5 | 532 (49.6) | 367 (48.9) | 165 (51.2) |

|

| M stage, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| M0 | 979 (91.2) | 684 (91.1) | 295 (91.6) | 0.776 |

| M1 | 94 (8.8) | 67 (8.9) | 27 (8.4) |

|

| Mean TSH level ±

SD, mIU/l | 106.75±48.54 | 106.64±49.03 | 107.00±47.45 | 0.231 |

| TgAb level

[TgAb(+)], kIU/la | 26.85

(10.67–87.65) | 19.3

(8.1–62.2) | 38.2

(17.4–120.5) | 0.023 |

| Tg level [TgAb(−)],

µg/la | 3.08

(0.94–9.20) | 3.3 (0.9–10.0) | 2.8 (1.0–7.5) | 0.427 |

| 6-month response, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| ER +

IDR | 815 (76.0) | 567 (75.5) | 248 (77.0) | 0.594 |

| BIR +

SIR | 258 (24.0) | 184 (24.5) | 74 (23.0) | 3-year |

| 3-year response, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| ER +

IDR | 929 (86.6) | 646 (86.0) | 283 (87.9) | 0.41 |

| BIR +

SIR | 144 (13.4) | 105 (14.0) | 39 (12.1) |

|

A comprehensive review of the dataset was conducted.

By random sampling, 1,073 cases not included in the analysis were

selected as the ‘Excluded group’, and the model-trained data was

the ‘Included group’. This revealed that no statistically

significant differences in baseline characteristics. A comparative

analysis of key baseline characteristics (for example, age, sex,

tumor size, T stage, N stage, AJCC Stage and response to therapy)

was conducted between the included cohort (n=1,073) and the

excluded cohort with missing BRAF and TSH levels data (n=1,315). No

statistically significant differences were found in the

distribution of age, sex, HT, subtypes, multifocality, tumor size,

capsule invasion, extrathyroidal invasion, T stage, N stage, M

stage, LNR, Tg level, TgAb level or initial treatment response

between the two groups. This suggests that the cohort with complete

BRAF data is representative of the larger patient population in

these fundamental clinical aspects (Table SI).

Univariate and multivariate analysis

results and nomogram excluding Tg

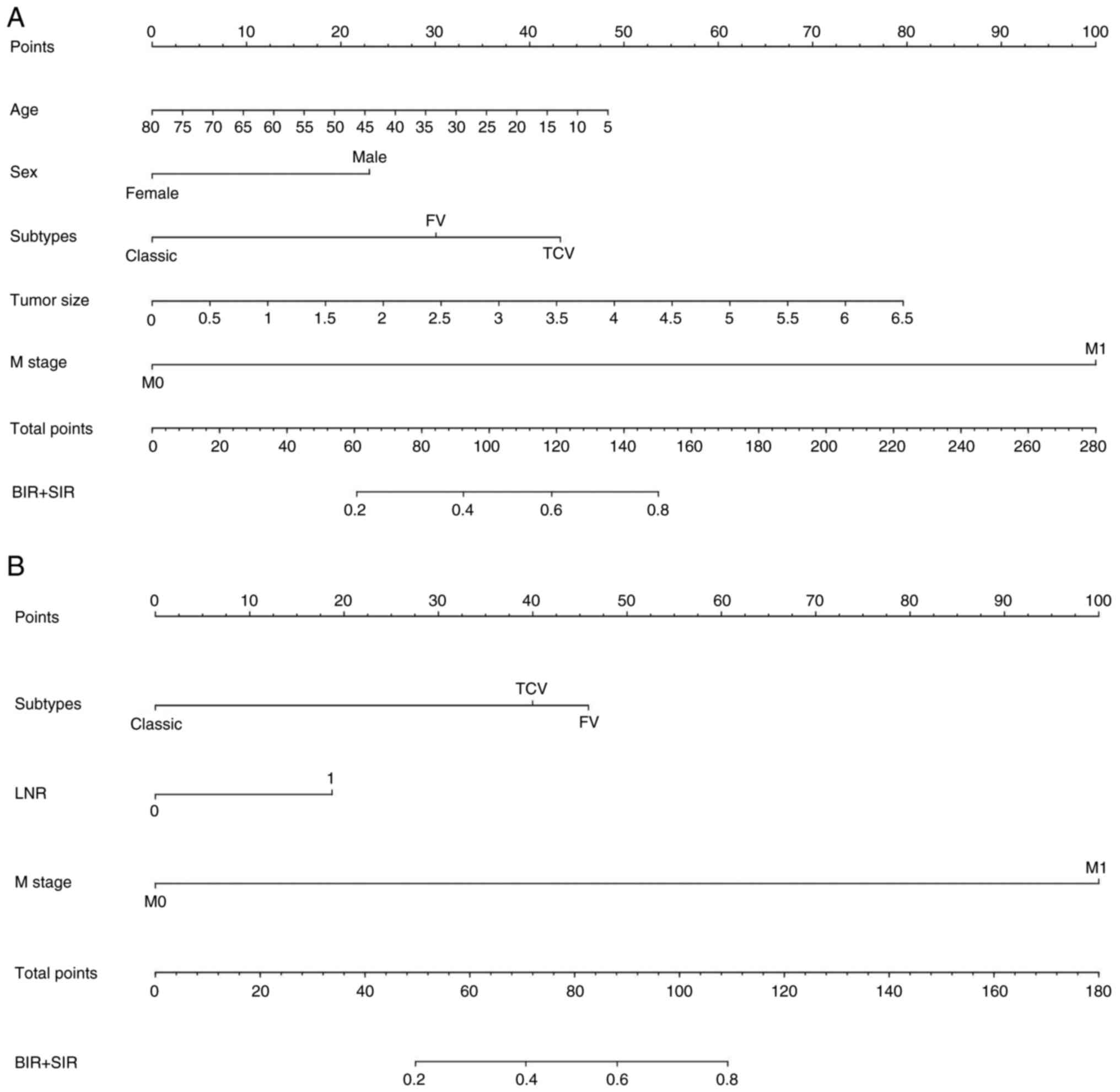

Univariate and multivariate analysis identified age,

female sex, follicular variant (FV) and tall cell variant (TCV)

subtypes, tumor size and M1 stage as independent risk factors for

adverse 6-month outcomes (all P<0.05; Fig. 2A; Tables SII and II), with excellent calibration (MAE,

0.009). For 3-year outcomes, risk factors included FV and TCV

subtypes, M1 stage and LNR (all P<0.05; Fig. 2B), showing strong calibration (MAE,

0.012). The 6-month nomogram highlighted M stage as dominant: M1

status contributed 100 points to total score, but only 40%

cumulative risk for BIR/SIR (Table

II).

| Table II.Excluding thyroglobulin multivariate

logistic regression analysis of factors associated with treatment

response in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma after

radioactive iodine therapy. |

Table II.

Excluding thyroglobulin multivariate

logistic regression analysis of factors associated with treatment

response in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma after

radioactive iodine therapy.

| A, 6-month

response |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variate | B | OR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

|---|

| Age | −0.020 | 0.980 | 0.964 | 0.997 | 0.020 |

| Sex (female) | −0.713 | 0.490 | 0.323 | 0.744 | <0.001 |

| Subtypes (FV) | 0.932 | 2.539 | 1.491 | 4.322 | <0.001 |

| Subtypes (TCV) | 1.340 | 3.819 | 1.295 | 11.266 | 0.015 |

| Tumor size | 0.379 | 1.461 | 1.202 | 1.776 | <0.001 |

| M stage (M1) | 3.097 | 22.137 | 9.843 | 49.788 | <0.001 |

| LNR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B, 3-year

response |

|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Variate | B | OR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sex (female) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Subtypes (FV) | 2.136 | 8.467 | 4.343 | 16.509 | <0.001 |

| Subtypes (TCV) | 1.860 | 6.427 | 1.786 | 23.125 | 0.004 |

| Tumor size |

|

|

|

|

|

| M stage (M1) | 4.653 | 104.872 | 40.932 | 268.689 | <0.001 |

| INR | 0.871 | 2.389 | 1.276 | 4.472 | 0.006 |

Assessment of the nomogram excluding

Tg

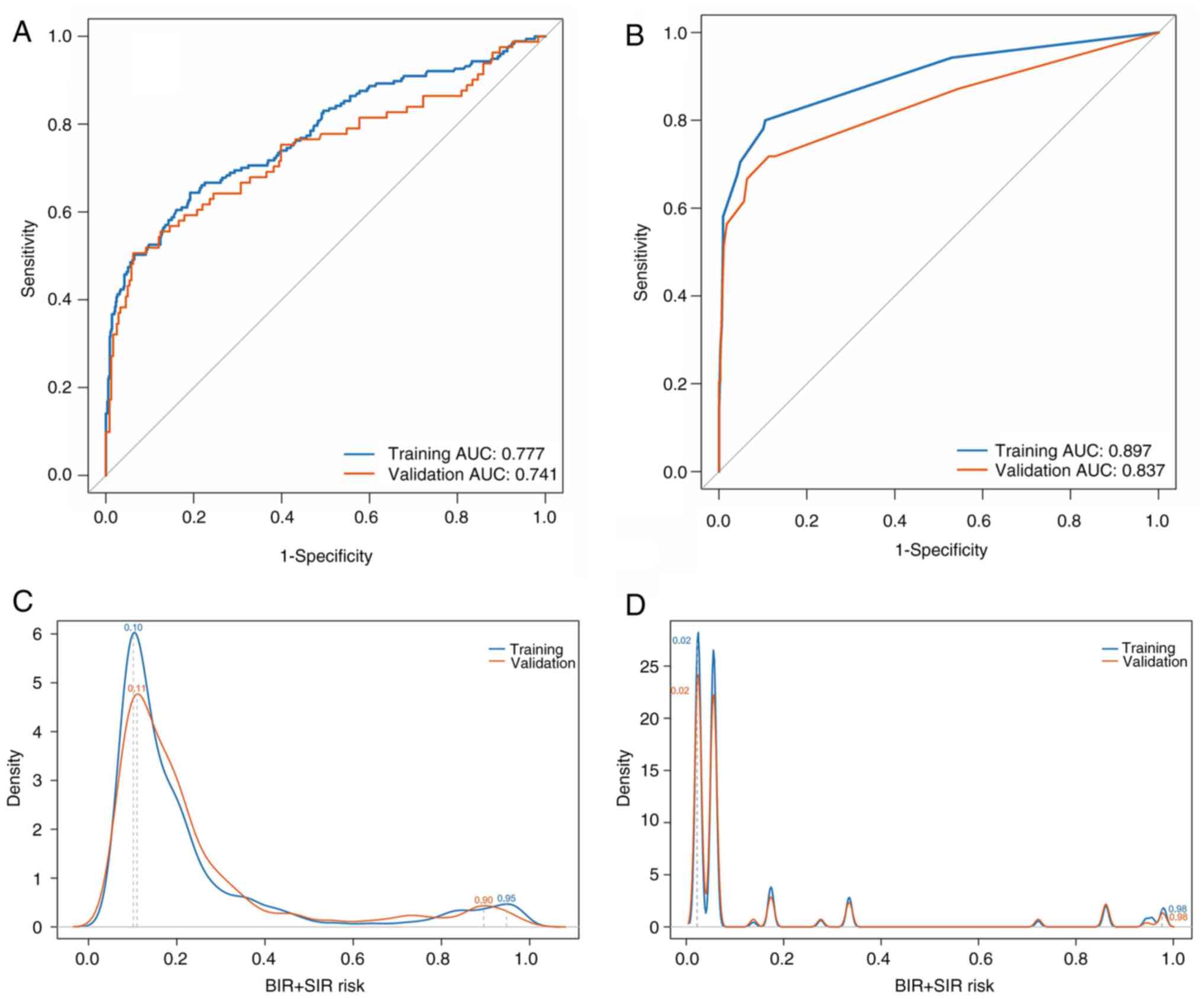

For the 6-month model, AUCs were 0.777 (training:

95% CI, 0.725–0.793) and 0.741 (validation: 95% CI, 0.721–0.790),

while for the 3-year model, AUCs were 0.897 (95% CI, 0.843–0.909)

and 0.837 (95% CI, 0.826–0.913). Probability density curves

revealed bimodal peaks: For the 6-month model, the training dataset

peaked at 0.10 and 0.95, and the validation dataset peaked at 0.11

and 0.90. For the 3-year model, both datasets peaked at 0.02 and

0.98. The dichotomous distribution supported K=2 for K-means

clustering, categorizing patients into low-risk and high-risk

groups. Case counts showed no significant differences for the

6-month (P=0.780) or 3-year (P=0.867) models between datasets,

indicating consistent distributions (Table III). Probability density curves

and boxplots confirmed distributional concordance in the validation

dataset (Figs. 3 and S1).

| Table III.Distribution and comparison of

excluding thyroglobulin nomogram risk scores between the training

and validation cohorts after K-means clustering. |

Table III.

Distribution and comparison of

excluding thyroglobulin nomogram risk scores between the training

and validation cohorts after K-means clustering.

| A, 6-month

response |

|---|

|

|---|

| Group | Level | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Frequency | P-value |

|---|

| Training | Low | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 673 | 0.780 |

|

| High | 0.84 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 78 |

|

| Validation | Low | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 286 |

|

|

| High | 0.79 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 36 |

|

|

| B, 3-year

response |

|

| Group | Level | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Q1 | Median | Q3 |

Frequency | P-value |

|

| Training | Low | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 684 | 0.867 |

|

| High | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 67 |

|

| Validation | Low | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 295 |

|

|

| High | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 27 |

|

Univariate and multivariate analysis

results and nomogram incorporating Tg

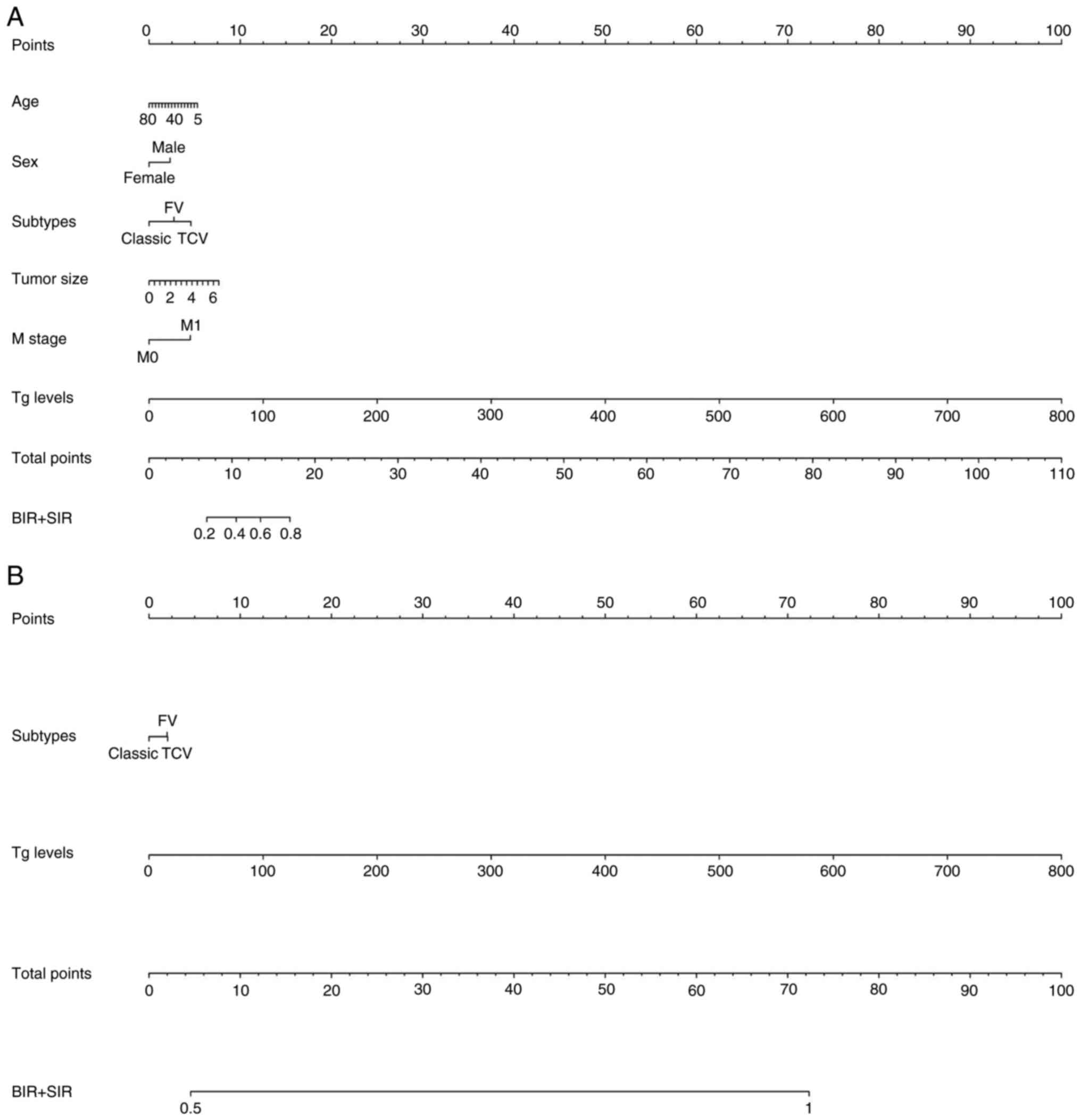

Univariate and multivariate analysis identified age,

female sex, FV and TCV subtype, tumor size, M1 stage and Tg levels

as risk factors for BIR/SIR at 6 months (P<0.05; Fig. 4A; Table

SII). Incorporating these variables yielded a predictive model

with reliable calibration (MAE, 0.018). For 3-year outcomes, risk

factors were FV and TCV subtypes, and Tg levels (P<0.05;

Fig. 4B), with excellent

calibration (MAE, 0.020) (Table

IV; Table SII). Tg level

dominated prediction for both time points. Specifically, 200 µg/l

Tg contributed 22.5 points to total score and accounted for 100%

risk for BIR/SIR.

| Table IV.Incorporating Tg multivariate

logistic regression analysis of factors associated with treatment

response in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma after

radioactive iodine therapy. |

Table IV.

Incorporating Tg multivariate

logistic regression analysis of factors associated with treatment

response in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma after

radioactive iodine therapy.

| A, 6-month

response |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variate | B | OR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

|---|

| Age | −0.020 | 0.981 | 0.964 | 0.998 | 0.025 |

| Sex (female) | −0.635 | 0.530 | 0.345 | 0.813 | 0.004 |

| Subtypes (FV) | 0.755 | 2.127 | 1.217 | 3.717 | 0.008 |

| Subtypes (TCV) | 1.267 | 3.549 | 1.229 | 10.244 | 0.019 |

| Tumor size | 0.325 | 1.384 | 1.128 | 1.697 | 0.002 |

| M stage (M1) | 1.250 | 3.490 | 1.069 | 11.393 | 0.038 |

| Tg level | 0.035 | 1.035 | 1.014 | 1.057 | <0.001 |

|

| B, 3-year

response |

|

|

|

|

| 95% CI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Variate | B | OR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sex (female) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Subtypes (FV) | 1.705 | 5.500 | 2.662 | 11.365 | <0.001 |

| Subtypes (TCV) | 1.755 | 5.783 | 1.761 | 18.992 | 0.004 |

| Tumor size |

|

|

|

|

|

| M stage (M1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tg level | 0.108 | 1.114 | 1.087 | 1.141 | <0.001 |

Assessment of the nomogram

incorporating Tg

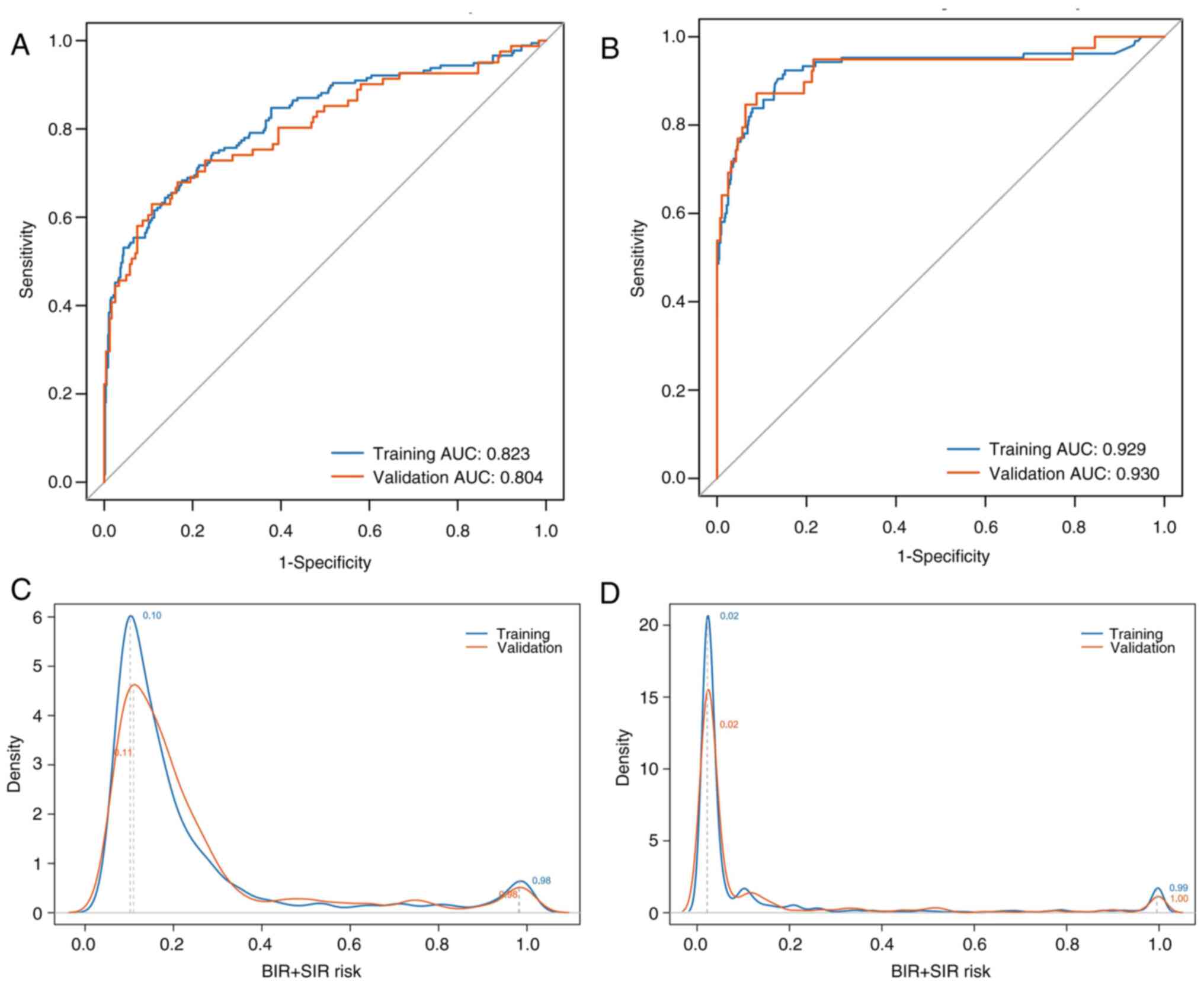

For 6-month outcomes, AUCs were 0.823 (training: 95%

CI, 0.801–0.845) and 0.804 (validation: 95% CI, 0.793–0.820),

indicating robust performance, while for 3-year outcomes, AUCs were

0.929 (training: 95% CI, 0.915–0.943) and 0.930 (validation: 95%

CI, 0.910–0.946), also confirming robustness. Probability density

distributions showed bimodal peaks: For 6-month outcomes, training

clusters were at risk values of 0.1 and 0.98, with validation

clusters at 0.11 and 0.98. For 3-year outcomes, training clusters

were at 0.02 and 0.99, with validation clusters at 0.02 and 1.0.

The distinct low-risk vs. high-risk separation indicated K=2 as

optimal for K-means clustering. Post-clustering, frequency

distributions showed no significant differences for 6-month

(P=0.714) or 3-year (P=0.767) outcomes between cohorts (Table V). Frequency density and box plots

revealed intracluster variations: At 6 months, validation low-risk

clusters agreed closely with training data, while high-risk

clusters exhibited slight dispersion. This pattern persisted for

the 3-year outcomes (Figs. 5 and

S2).

| Table V.Distribution and comparison of

incorporating Tg nomogram risk scores between the training and

validation cohorts after K-means clustering. |

Table V.

Distribution and comparison of

incorporating Tg nomogram risk scores between the training and

validation cohorts after K-means clustering.

| A, 6-month

response |

|---|

|

|---|

| Group | Level | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Frequency | P-value |

|---|

| Training | Low | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 663 | 0.714 |

|

| High | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 88 |

|

| Validation | Low | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 281 |

|

|

| High | 0.78 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 41 |

|

|

| B, 3-year

response |

|

| Group | Level | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Q1 | Median | Q3 |

Frequency | P-value |

|

| Training | Low | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 671 | 0.767 |

|

| High | 0.88 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 80 |

|

| Validation | Low | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 285 |

|

|

| High | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 37 |

|

Discussion

While conventional staging systems such as the AJCC

TNM classification and ATA risk stratification provide valuable

prognostic frameworks, they lack the precision required for

individualized outcome prediction following RAI treatment (16,17).

The present study developed and validated a nomogram incorporating

readily available clinical and pathological features to predict

prognostic outcomes in patients with PTC following RAI therapy.

Unlike previous PTC prognostic models that focused mainly on

preoperative or surgical outcomes (18–20),

the present study specifically addresses the post-RAI treatment

phase, a critical yet understudied period in disease management.

The present model advances current risk stratification approaches

by incorporating dynamic biomarkers, such as Tg levels, TgAb status

and early (6-month) treatment response, thereby achieving superior

predictive accuracy compared with static staging systems such as

AJCC TNM or ATA risk classifications.

The developed nomogram effectively integrated

clinical and histological variables (age, BRAFV600E

mutation status, extrathyroidal extension and TNM stage), all

established predictors of PTC aggressiveness. Notably,

BRAFV600E-positive tumors and advanced T/N stages were

strongly associated with NER, which aligns with the literature

(21). Specifically, the present

data showed that patients with BRAFV600E mutations had a

2.5-fold increased risk of NER at 6 months, while those with M1

stage disease demonstrated a 22.1-fold increased risk of a poor

outcome. These findings underscore the importance of combining

molecular and clinicopathological factors for prognostication.

Molecular investigations by Fagin and Wells (22) revealed that impaired RAI efficacy is

strongly correlated with BRAF/RAS mutations and RET/PTC

rearrangements, which promote tumor progression through MAPK

pathway-mediated alterations in cell biological behavior. The

present results further substantiate this mechanism, showing that

BRAFV600E mutation was not only prevalent (66.9% in the

cohort), but also independently predictive of a poor treatment

response. Additionally, growing evidence suggests that adverse

pathological features, such as TCV, lymph node metastasis and gross

extrathyroidal extension, further compromise RAI avidity and are

associated with higher rates of treatment failure (23). In the present study, TCV was

associated with a significantly increased risk of poor outcomes at

both 6 months and 3 years, while a high LNR emerged as a strong

predictor of 3-year NER.

However, the differential impact of predictors over

time, with demographic factors such as age and sex diminishing in

significance, while tumor subtype, M stage and LNR persist as

long-term determinants, likely reflects the shifting balance

between initial therapeutic response and inherent tumor biology. In

the short term (6 months), the response to RAI therapy is a

function of both the patient's physiological context (for example,

hormonal milieu or immune status potentially influenced by age and

sex) and tumor characteristics. However, over the longer term (3

years), the influence of transient physiological factors wanes, and

the aggressive, innate biological drive of the tumor itself becomes

the dominant prognostic force. Factors such as TCV subtype and the

presence of M1 stage are well-established markers of

de-differentiation, reduced iodine avidity and increased metastatic

potential; their persistent significance underscores that they

represent a more aggressive disease phenotype that is harder to

eradicate with initial therapy and is more likely to progress or

recur despite an initial response (24,25).

This temporal shift in predictor weight underscores the dynamic

nature of PTC progression and highlights the need for time-specific

prognostic models (26).

The study cohort exhibited notable variations in

TgAb positivity rates (10.8% in the training dataset vs. 15.5% in

the validation dataset; P=0.023), aligning with reported TgAb

prevalence ranges of 10–25% in PTC populations (27). The 12.3% overall TgAb-positive rate

(132/1,073) highlights the clinical imperative for Tg-independent

predictive tools, particularly given that TgAb interference affects

~20% of Tg measurements in clinical practice. Although Tg is not

incorporated in the initial risk stratification under current ATA

guidelines, an associated has been suggested between undetectable

post-operative Tg and a low possibility of biochemical or

structural recurrence in a patient with low ATA risk (28). A notable finding was the

disproportionate influence of Tg in the initial model, where a

solitary Tg level of 200 µg/l could theoretically confer a 100%

predicted risk of poor prognosis; a clinically unrealistic scenario

that highlights the limitations of over-reliance on single

biomarkers. To address this, the present study developed an

alternative 3-year prognostic model that replaces Tg with more

balanced multivariable predictors, including LNR and M stage. This

refined version demonstrates three key advantages: i) It eliminates

the disproportionate weighting of any single variable; ii)

maintains clinically acceptable performance; and iii) provides

reliable risk stratification even when Tg measurements are

unavailable or unreliable, which is a common clinical challenge

given that 20–25% of patients with PTC have TgAb interference.

Furthermore, unlike models that rely heavily on

pre-ablation Tg levels or fixed-dose RAI protocols, the present

nomogram integrates both dynamic variables (for example, Tg levels

and 6-month treatment response) and static clinicopathological

features (for example, tumor subtype and M stage), enhancing its

predictive power for both short- and long-term outcomes (29). A particularly innovative aspect of

the present study is the demonstration that the model remains

clinically useful even when Tg is excluded, addressing a major

limitation in current practice where Tg measurements can be

unreliable due to antibody interference or other factors.

Additionally, the nomogram provides a more balanced risk assessment

by incorporating multifactorial interactions (for example, M stage

and LNR) that mitigate the over-reliance on any single predictor,

such as Tg. This contrasts with some existing tools that may

disproportionately weight individual variables. Rigorous validation

across independent cohorts further strengthens the reliability and

generalizability of the present model, as evidenced by robust AUC

values (>0.8) and excellent calibration (MAE <0.02). Garo

et al (30) noted that

currently available nomograms exhibit considerable heterogeneity,

and their predictive performance appears highly dependent on the

particular patient cohorts from which they were derived.

While the present study presents a clinically useful

nomogram for predicting RAI therapy outcomes in patients with PTC,

several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the

retrospective design may introduce selection bias, particularly due

to the exclusion of patients with incomplete data (for example,

missing BRAF mutation status), which could limit the

generalizability of the findings. Second, the model was developed

and validated at a single institution, and its performance should

be confirmed in multicenter, prospective cohorts to ensure broader

applicability across diverse populations and healthcare settings.

Third, although the nomogram incorporates key clinicopathological

variables, it does not account for emerging molecular markers, such

as TERT promoter mutations or programmed death-ligand 1 expression,

which have been associated with aggressive tumor behavior and

treatment resistance. Future iterations of the model could benefit

from integrating these biomarkers to enhance predictive

accuracy.

In conclusion, this study developed a clinical

nomogram that effectively predicts outcomes in patients with PTC

after RAI therapy by integrating key risk factors, such as tumor

subtype, M stage and Tg levels. The model showed strong predictive

accuracy and reliably stratified patients into low- and high-risk

groups. Even without Tg data, it maintained utility using

alternative markers. This tool supports personalized treatment

planning, though further external validation is needed to confirm

its broader applicability.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC and HL wrote the main manuscript text. XL, HL and

HX prepared the figures and tables. JC, XG and HX conceived and

designed the study. JC, HL, XL and XG collected and analyzed the

data. HL, XL and XG confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study complies with the Declaration of

Helsinki. All of the study procedures were approved by The Second

Hospital of Shandong University institutional review board

(approval no. KYLL-2022LW077; Jinan, China). Written informed

consent was obtained from all individual participants included in

the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HT

|

Hashimoto's thyroiditis

|

|

T

|

primary tumor

|

|

N

|

regional lymph nodes

|

|

M

|

metastasis

|

|

TSH

|

thyroid-stimulating hormone

|

|

TgAb

|

thyroglobulin antibody

|

|

ER

|

excellent response

|

|

IDR

|

indeterminate response

|

|

BIR

|

biochemical incomplete response

|

|

SIR

|

structural incomplete response

|

References

|

1

|

Megwalu UC and Moon PK: Thyroid cancer

incidence and mortality trends in the United States: 2000–2018.

Thyroid. 32:560–570. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, Bernet VJ,

Bourguet P, Daniels GH, Dillehay G, Draganescu C, Flux G, Führer D,

et al: controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of

131I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: A joint

statement from the American thyroid association, the European

association of nuclear medicine, the society of nuclear medicine

and molecular imaging, and the European thyroid association.

Thyroid. 29:461–470. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xing M: Molecular pathogenesis and

mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:184–199. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, Viola D,

Elisei R, Bendlova B, Yip L, Mian C, Vianello F, Tuttle RM, et al:

Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients

with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. 309:1493–1501. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Moon S, Song YS, Kim YA, Lim JA, Cho SW,

Moon JH, Hahn S, Park DJ and Park YJ: Effects of coexistent

BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations on poor clinical

outcomes in papillary thyroid cancer: A meta-analysis. Thyroid.

27:651–660. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bournaud C, Descotes F, Decaussin-Petrucci

M, Berthiller J, de la Fouchardière C, Giraudet AL,

Bertholon-Gregoire M, Robinson P, Lifante JC, Lopez J and

Borson-Chazot F: TERT promoter mutations identify a high-risk group

in metastasis-free advanced thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Cancer.

108:41–49. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Valero C, Eagan A, Adilbay D, Matsuura D,

Harries V, Shaha AR, Shah JP, Tuttle RM, Akhmedin D, Pinheiro RA,

et al: A clinical nomogram to predict survival outcomes in patients

with well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 35:397–405. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wei M, Wang R, Zhang W, Zhang J, Fang Q,

Fang Z, Liu B and Li Y: Landscape of gene mutation in Chinese

thyroid cancer patients: Construction and validation of lymph node

metastasis prediction model based on clinical features and gene

mutation marker. Cancer Med. 12:12929–12942. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wen R, Zhao M, Chen C, Yang Y and Zhang B:

A novel nomogram integrated with preablation stimulated

thyroglobulin and thyroglobulin/thyroid-stimulating hormone ratio

to predict the therapeutic response of intermediate- and high-risk

differentiated thyroid cancer patients: A bi-center retrospective

study. Endocrine. 84:989–998. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li S, Yun M, Hong G, Tian L, Yang A and

Liu L: Development and validation of a nomogram for preoperative

prediction of level VII nodal spread in papillary thyroid cancer:

Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Surg Oncol. 37:1015202021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li Y, Wang J, Hui J, Hou G, He W, Sun T,

Gao L, Wei Y, Zhang W, Zheng L, et al: Postoperative nomogram for

predicting involved lymph node in differentiated thyroid carcinoma:

An observational study. Future Oncol. 21:2785–2793. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Persoon ACM, Links TP, Wilde J, Sluiter

WJ, Wolffenbuttel BHR and van den Ouweland JMW: Thyroglobulin (Tg)

recovery testing with quantitative Tg antibody measurement for

determining interference in serum Tg assays in differentiated

thyroid carcinoma. Clin Chem. 52:1196–1199. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Neshandar Asli I, Siahkali AS, Shafie B,

Javadi H and Assadi M: Prognostic value of basal serum

thyroglobulin levels, but not basal antithyroglobulin antibody

(TgAb) levels, in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Mol

Imaging Radionucl Ther. 23:54–59. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty

GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM,

Schlumberger M, et al: 2015 American thyroid association management

guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and

differentiated thyroid cancer: The American thyroid association

guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid

cancer. Thyroid. 26:1–133. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Duda OR, Slipetsky RR and Bojko NI:

Principles of medullary thyroid cancer staging according to AJCC

TNM 8th edition. AML. 27:101–116. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Suh S, Kim YH, Goh TS, Lee J, Jeong DC, Oh

SO, Hong JC, Kim SJ, Kim IJ and Pak K: Outcome prediction with the

revised American joint committee on cancer staging system and

American thyroid association guidelines for thyroid cancer.

Endocrine. 58:495–502. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ghaznavi SA, Ganly I, Shaha AR, English C,

Wills J and Tuttle RM: Using the American thyroid association

risk-stratification system to refine and individualize the American

joint committee on cancer eighth edition disease-specific survival

estimates in differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 28:1293–1300.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ and

DeMatteo RP: Nomograms in oncology: More than meets the eye. Lancet

Oncol. 16:e173–e180. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sun J, Jiang Q and Wang X, Liu W and Wang

X: Nomogram for preoperative estimation of cervical lymph node

metastasis risk in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:6139742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang R, Tang Z, Wu Z, Xiao Y, Li J, Zhu J,

Zhang X and Ming J: Construction and validation of nomograms to

reduce completion thyroidectomy by predicting lymph node metastasis

in low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol.

49:1395–1404. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang Q, Yu B, Zhang S, Wang D, Xiao Z,

Meng H, Dong L, Zhang Y, Wu J, Hou Z, et al: Papillary thyroid

carcinoma: correlation between molecular and clinical features. Mol

Diagn Ther. 28:601–609. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fagin JA and Wells SA Jr: Biologic and

clinical perspectives on thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med.

375:1054–1067. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nappi C, Megna R, Zampella E, Volpe F,

Piscopo L, Falzarano M, Vallone C, Pace L, Petretta M, Cuocolo A

and Klain M: External validation of a predictive model for

post-treatment persistent disease by 131I whole-body

scintigraphy in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Eur J

Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 52:2867–2874. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang X, Zheng X, Zhu J, Li Z and Wei T: A

nomogram and risk classification system for predicting

cancer-specific survival in tall cell variant of papillary thyroid

cancer: A SEER-based study. J Endocrinol Invest. 46:893–901. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kim DH, Jung JH, Son SH, Kim CY, Hong CM,

Jeong SY, Lee SW, Lee J and Ahn BC: Difference of clinical and

radiological characteristics according to radioiodine avidity in

pulmonary metastases of differentiated thyroid cancer. Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 48:55–62. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lamartina L, Durante C, Lucisano G, Grani

G, Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Pontecorvi A, Arvat E, Felicetti F,

Zatelli MC, et al: Are evidence-based guidelines reflected in

clinical practice? An analysis of prospectively collected data of

the Italian thyroid cancer observatory. Thyroid. 27:1490–1497.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Anderson H, Lim KH, Gull S, Oprean R,

Spence K and Cvasciuc T: Predicting clinical outcomes of patients

with serum thyroglobulin antibodies after thyroidectomy for

differentiated thyroid cancer: A retrospective study from a UK

regional center. Minerva Endocrinol (Torino). 49:60–68.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang Y, Hua W, Zhang X, Peng J, Liang J

and Gao Z: The predictive value for excellent response to initial

therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: Preablation-stimulated

thyroglobulin better than the TNM stage. Nucl Med Commun.

39:405–410. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lu L, Li Q, Ge Z, Lu Y, Lin C, Lv J, Huang

J, Mu X and Fu W: Development of a predictive nomogram for

intermediate-risk differentiated thyroid cancer patients after

fixed 3.7GBq (100mCi) radioiodine remnant ablation. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:13616832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Garo ML, Deandreis D, Campennì A,

Vrachimis A, Petranovic Ovcaricek P and Giovanella L: Accuracy of

papillary thyroid cancer prognostic nomograms: A systematic review.

Endocr Connect. 12:e2204572023.

|