Introduction

Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) is a rapidly developing,

aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is more prevalent in

pediatric patients than in adults (1). It is estimated that there were 553,389

new cases and 250,679 deaths worldwide in 2022 (2). The 5-year net survival rate was

>80% in high-income countries, and <50% in certain regions of

Central and South America (3). The

current mainstay of treatment for BL is multidrug chemotherapy,

which employs doxorubicin alkylating agents, vincristine and

etoposide. However, prolonged high-dose and high-intensity

chemotherapy is less tolerated by patients, frequently leading to

clinical toxicity and treatment-related complications.

Concurrently, these regimens impede bone marrow function, suppress

the immune response and induce clinical infections during treatment

(4–6). Therefore, it is necessary to develop a

novel type of treatment that is less immunosuppressive and more

tolerable.

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing

ligand (TRAIL; also referred to as Apo2L) is a member of the TNF

superfamily and a promising antitumor medication due to its unique

ability to destroy cancer cells whilst maintaining normal cells

(7). TRAIL induces apoptosis by

binding to the receptors TRAIL-R1 [(death receptor 4 (DR4)] and

TRAIL-R2 [(death receptor 5 (DR5)], leading to the formation of the

death-inducing signaling complex and subsequent activation of

caspase 8. As the apical caspase in this extrinsic pathway,

activated caspase-8 directly cleaves and activates the effector

caspase 3/7, which serve as the ultimate executioners of the

apoptotic program and can be activated by both extrinsic and

intrinsic pathways (8).

Although TRAIL has the capacity to induce apoptosis

in certain tumor cells, certain malignant lymphomas are resistant

to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (9).

Clinical combination therapies to increase the sensitivity of

cancer cells to TRAIL include chemotherapy drugs, radiation therapy

or immunotherapy, as well as several signal transduction modulators

and small molecule inhibitors, providing the optimal combination

for the use of TRAIL in cancer treatment (10–14).

The use of proteasome inhibitors has also been reported to be a

promising strategy to enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to

TRAIL (15).

Bortezomib (PS-341; Velcade) is the first selective

proteasome inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration for the treatment of multiple myeloma and relapsed

mantle cell lymphoma (16).

Bortezomib has been reported to synergistically enhance

TRAIL-induced apoptosis in multiple drug-resistant cancer cells,

such as SNU-216 gastric cancer cells (17), B16F10 melanoma cells and CT26 colon

carcinoma cells (18). The

induction of apoptosis by bortezomib in primary chronic lymphocytic

leukemia cells and the BJAB BL cell line has been reported to be

associated with the upregulation of TRAIL and its death receptors

DR4 and DR5 (19). However, to the

best of our knowledge, the synergistic antitumor effects of

bortezomib and TRAIL in drug-resistant BL cells, and the underlying

mechanism, have not yet been elucidated. Our previous study

reported that several BL cell lines, including Raji and CA46 cells,

were insensitive to TRAIL, with Raji cells exhibiting the lowest

sensitivity to TRAIL (20).

Therefore, in the present study, Raji cells were selected to

explore the synergistic inhibitory effect of bortezomib and TRAIL,

and the underlying mechanism, in order to provide a novel

therapeutic strategy for TRAIL-insensitive BL cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

TRAIL (cat. no. HY-P77256, purity, ≥95%) and

bortezomib (cat. no. HY-10227, purity, ≥99%) were purchased from

MedChemExpress. RPMI 1640 medium and FBS were purchased from Gibco

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was

purchased from Biosharp Life Sciences. ProteinSafe™ phosphatase

inhibitor cocktail and protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA-free) were

purchased from TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd. An Annexin V-FITC/PI

apoptosis detection kit, a mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

assay kit with JC-1, a reactive oxygen species (ROS) kit,

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and RIPA lysis buffer were purchased from

Beyotime Biotechnology. BCA and supersensitive ECL kits were

purchased from Oriscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. PVDF membranes

were purchased from Merck KGaA. The phycoerythrin (PE)-CD262 (DR5)

monoclonal antibodies (cat. no. 12-9908-42) and PE-CD261 (DR4)

monoclonal antibodies (cat. no. 12-6644-42) were purchased from

eBioscience (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Antibodies against

PARP (cat. no. 9532), cleaved PARP (cat. no. 5625), caspase 8 (cat.

no. 4790), cleaved caspase 8 (cat. no. 9496), caspase 9 (cat. no.

9504), cleaved caspase 9 (cat. no. 7237), caspase 3 (cat. no.

9662), cleaved caspase 3 (cat. no. 9664), Bcl-xl (cat. no. 2764),

Bcl-2 (cat. no. 3498), phosphorylated (p-) p38 (cat. no. 4511), p-

stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK;

cat. no. 4668), p-c-Jun (cat. no. 3270), p-activating transcription

factor 2 (ATF2; cat. no. 27934), p-extracellular signal-regulated

kinase (ERK)1/2 (cat. no. 4695), C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP;

cat. no. 2895), GAPDH (cat. no. 5174) and HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit antibodies (cat. no. 7074) were purchased from Cell

Signaling Technology Inc. with GAPDH as the internal reference

protein. GAPDH antibodies were diluted at a ratio of 1:10,000,

whilst all other antibodies were diluted at a ratio of 1:1,000. All

other chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Cell culture

Raji (cat. no. CCL-86; American Type Culture

Collection) and CA46 (cat. no. CRL-1648; American Type Culture

Collection) BL cell lines were cryopreserved in a liquid nitrogen

tank in the laboratory. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with 10% FBS under humidified conditions with 5%

CO2 at 37°C, according to the culture conditions

recommended by American Type Culture Collection. Cells in the

logarithmic growth phase were used in subsequent experiments.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell viability was determined using a CCK-8 assay.

The TRAIL stock solution was prepared by dissolving the powder via

sonication according to the manufacturer's protocol, which suggests

a stock solution of ≥100 µg/ml in ddH2O. Additionally,

there should be no crystals when determining the maximum working

concentration. Viable Raji and CA46 cells were seeded in a 96-well

plate, incubated with 1×105, 5×104,

2.5×104, 1.25×104, 6.25×103,

3.125×103 or 0 ng/ml TRAIL, and incubated with 200, 100,

50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 or 0 nM bortezomib and/or 100 ng/ml TRAIL,

followed by the addition of CCK-8 to each well and incubation for

another 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. The absorbance at 450

nm was measured using a Powerwave XS multiplate reader (BioTek;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Data acquisition and half-maximal

inhibitory concentration analysis were performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 software (Dotmatics). The following formula was used to

determine the cell inhibition rate: Cell inhibition rate

(%)=[1-optical density (OD) mean value of the experimental group/OD

mean value of the control group] ×100%.

Apoptosis analysis

Viable Raji cells treated with 100, 50, 25 or 0 nM

bortezomib and/or 100 ng/ml TRAIL for 24 h at 37°C. A total of

2×105 cells/well were harvested and washed with ice-cold

PBS. The cells were stained with 200 µl staining buffer containing

10 µl annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI, followed by incubation at 25°C

for 20 min, after which the proportion of apoptotic cells was

detected and analyzed using flow cytometry (Quanteon; ACEA

Biosciences, Inc.). NovoExpress software (version 1.6.1, Agilent

Technologies) was used for data analysis. Morphological changes in

Raji cells were observed under an inverted microscope (Olympus

Corporation) after treatment with bortezomib and TRAIL.

MMP assay

Changes in the MMP were detected by staining cells

with the fluorescent probe JC-1. Raji cells treated with 100, 50,

25 or 0 nM bortezomib and/or 100 ng/ml TRAIL for 24 h at 37°C with

2×105 cells/well were harvested, washed with ice-cold

PBS and stained with 5 mg/ml JC-1 at 37°C for 30 min in the dark.

Data acquisition and analysis of the MMP were performed using flow

cytometry. The analyte reporter was the fluorescent probe JC-1,

which exhibits a shift from red fluorescence (J-aggregates, ~590 nm

emission) to green fluorescence (monomers, ~527 nm emission) upon

mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Data acquisition was

performed using a NovoCyte Quanteon flow cytometer (ACEA

Biosciences, Inc.), and data analysis was conducted with

NovoExpress software (version 1.6.1, Agilent Technologies).

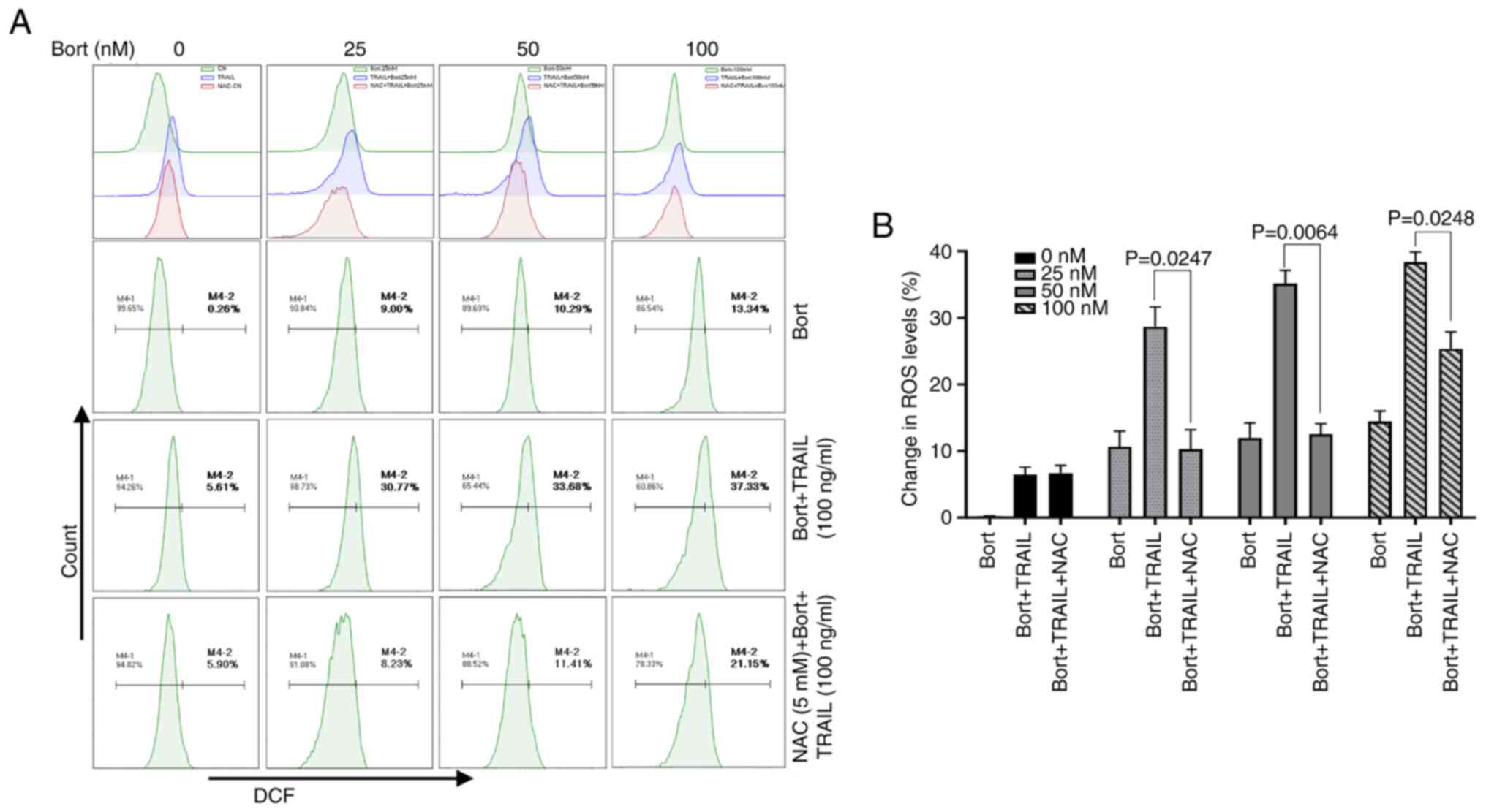

Intracellular ROS assay

NAC, a ROS scavenger and antioxidant, was used to

assess intracellular ROS generation (21). Raji cells were divided into two

groups: i) Pretreatment with NAC for 1 h at 37°C; and ii) untreated

(control) group. Subsequently, both groups were exposed to varying

concentrations of bortezomib (0, 25, 50 or 100 nM) and/or TRAIL

(100 ng/ml) for 24 h at 37°C, after which the cells were harvested,

washed with PBS, mixed with 10 µM 2′-7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

diacetate and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 min. Data

acquisition and analysis of ROS were performed using flow

cytometry. The analyte reporter was the fluorescent probe

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate. Data acquisition was

performed using a NovoCyte Quanteon flow cytometer (ACEA

Biosciences, Inc.), and data analysis was conducted with

NovoExpress software (version 1.6.1, Agilent Technologies).

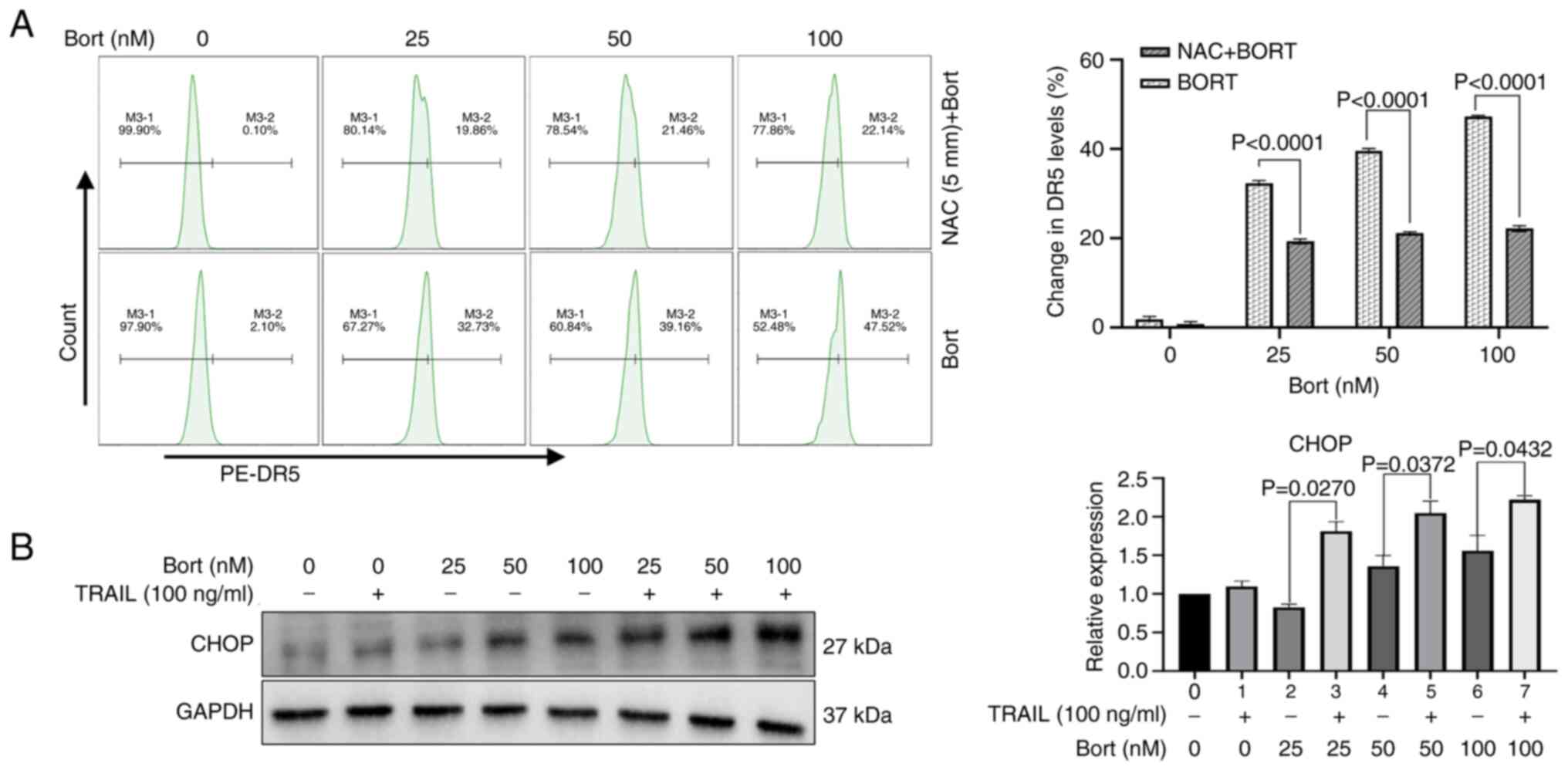

Analysis of DR5 expression on the cell

surface

To assess whether bortezomib enhances TRAIL

sensitivity via the ROS-dependent regulation of DR5 expression,

Raji cells were divided into two groups: i) Pretreatment with NAC

(10 mM) for 1 h at 37°C; and ii) untreated group. Both groups were

then exposed to increasing concentrations of bortezomib (0, 25, 50

or 100 nM) for 24 h at 37°C, and then stained with PE-CD262 (DR5)

monoclonal antibodies at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. Data

acquisition and analysis of DR5 expression in Raji cells were

performed using flow cytometry. The analyte reporter was a PE-CD262

(DR5) monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 12-9908-42) was directly

conjugated to PE. Data acquisition was performed using a NovoCyte

Quanteon flow cytometer (ACEA Biosciences, Inc.), and analysis was

conducted with NovoExpress software (version 1.6.1, Agilent

Technologies).

Western blot analysis

Raji cells treated with 100, 50, 25 or 0 nM

bortezomib and/or 100 ng/ml TRAIL for 24 h at 37°C with

5×106 cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing

protease inhibitors or phosphatase inhibitors, then lysed on ice

for 30 min, mixed at 5-min intervals and centrifuged at 13,000 ×

g/min for 15 min at 4°C. The protein supernatants were collected,

and the protein concentration was determined using BCA kit.

Proteins (50 µg) were separated using 12% SDS-PAGE. The proteins

were subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were

blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h at 37°C, and incubated with primary

antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then with secondary antibodies

conjugated to HRP for another 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the PVDF

membranes were developed with ECL emitting solution and images were

captured using a gel imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

The integrated optical density (IOD) values of the protein blots

were analyzed using ImageJ 1.54 analysis software (National

Institutes of Health). GAPDH served as a loading control to

normalize for equal protein loading across samples, and the IOD of

the target protein/IOD of GAPDH ratio reflected the relative

expression level of the target protein.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 10.0 software (Dotmatics). Each group of experiments was

independently repeated three times, and the experimental results

are presented as the mean ± SD. The differences between two groups

were compared using t-tests with Welch's correction, whilst the

differences between multiple groups were compared using one-way

ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test. Although all multiple

comparisons were formally assessed, only selected pairwise results

are displayed in the figures for clarity. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Bortezomib enhances TRAIL sensitivity

and synergistically inhibits proliferation in BL cells

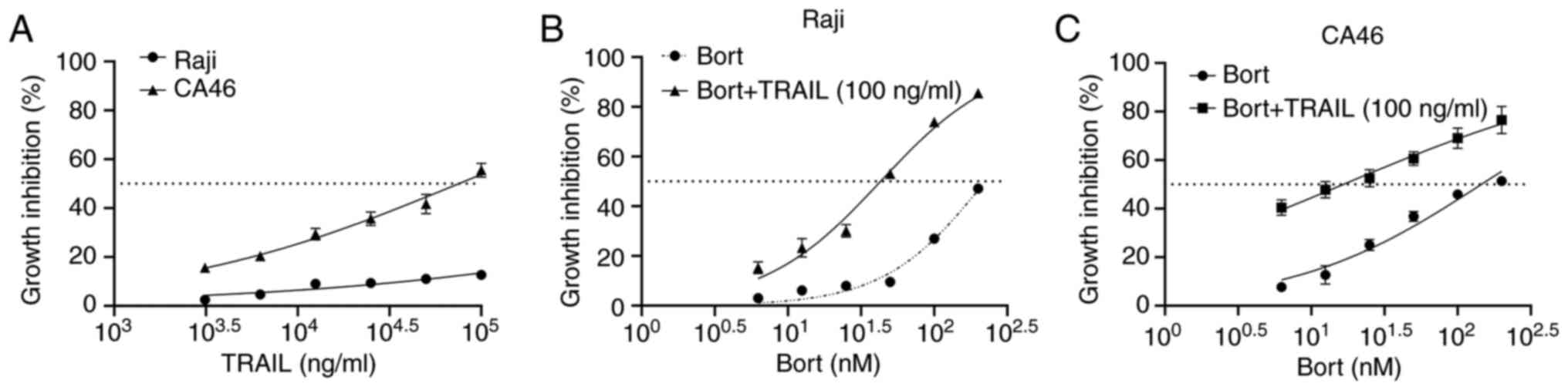

According to established criteria, cell lines

exhibiting <50% tumor growth inhibition following treatment with

100 ng/ml TRAIL are classified as TRAIL-insensitive (22). Cell viability assays revealed that

the BL cell lines (Raji and CA46) were insensitive to TRAIL. When

applied at a high concentration (1×105 ng/ml), TRAIL

achieved a proliferation inhibition rate of ~50% in CA46 cells,

whilst demonstrating notably less efficacy in Raji cells (<50%

inhibition; Fig. 1A). However, when

cells were treated with different concentrations of bortezomib

combined with 100 ng/ml TRAIL for 24 h, the inhibition of Raji

(Fig. 1B) and CA46 (Fig. 1C) cell proliferation noticeably

improved.

According to the Chou-Talalay combination index (CI)

method (23), synergistic, additive

and antagonistic effects between drugs are indicated when CI<1,

CI=1 and CI>1, respectively, whereas CI<0.9 indicates strong

synergistic effects. Bortezomib and TRAIL demonstrated strong

synergistic effects on Raji and CA46 cells (Table I). These results suggest that

bortezomib enhanced TRAIL sensitivity and synergistically inhibited

proliferation in BL cells. Consequently, the Raji cell line, the

least TRAIL-sensitive strain, was selected as the model for

subsequent experiments.

| Table I.Combination index value of bortezomib

and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

combination therapy. |

Table I.

Combination index value of bortezomib

and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

combination therapy.

| A, Raji cells |

|---|

|

|---|

| Bortezomib, nM | TRAIL, ng/ml | Effect | CIa |

|---|

| 200.00 | 100.0 | 0.85495 | 0.04971 |

| 100.00 | 100.0 | 0.73910 | 0.06212 |

| 50.00 | 100.0 | 0.53075 | 0.09787 |

| 25.00 | 100.0 | 0.30000 | 0.16464 |

| 12.50 | 100.0 | 0.23000 | 0.12932 |

| 6.25 | 100.0 | 0.15000 | 0.12527 |

|

| B, CA46

cells |

|

| Bortezomib,

nM | TRAIL,

ng/ml | Effect | CIa |

|

| 200.00 | 100.0 | 0.76543 | 0.24680 |

| 100.00 | 100.0 | 0.69000 | 0.22003 |

| 50.00 | 100.0 | 0.60597 | 0.19259 |

| 25.00 | 100.0 | 0.52500 | 0.15917 |

| 12.50 | 100.0 | 0.47773 | 0.10674 |

| 6.25 | 100.0 | 0.40460 | 0.08510 |

Combination of bortezomib and TRAIL

could induce morphological changes in Raji cells

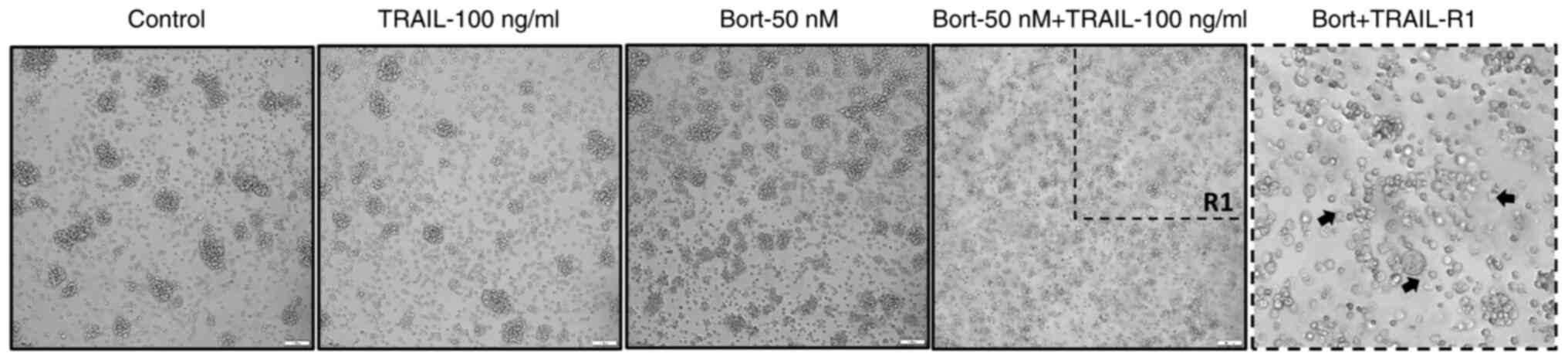

Morphological analysis of Raji cells treated for 24

h with 50 nM bortezomib and/or 100 ng/ml TRAIL was performed using

inverted microscopy at a magnification of ×10. Compared with no

treatment, treatment with 100 ng/ml TRAIL alone did not induce

notable morphological changes. By contrast, 50 nM bortezomib alone

triggered characteristic apoptotic morphology, including cell

shrinkage. The combination of bortezomib and TRAIL produced

synergistic effects, as demonstrated by markedly reduced cell

density and widespread cell death. At a higher magnification of

×40, the R1 field displayed classical apoptotic hallmarks,

including marked cell shrinkage, nuclear condensation, membrane

blebbing and apoptotic body formation, confirming enhanced

cytotoxicity (Fig. 2).

Bortezomib combined with TRAIL induces

the apoptosis of Raji cells

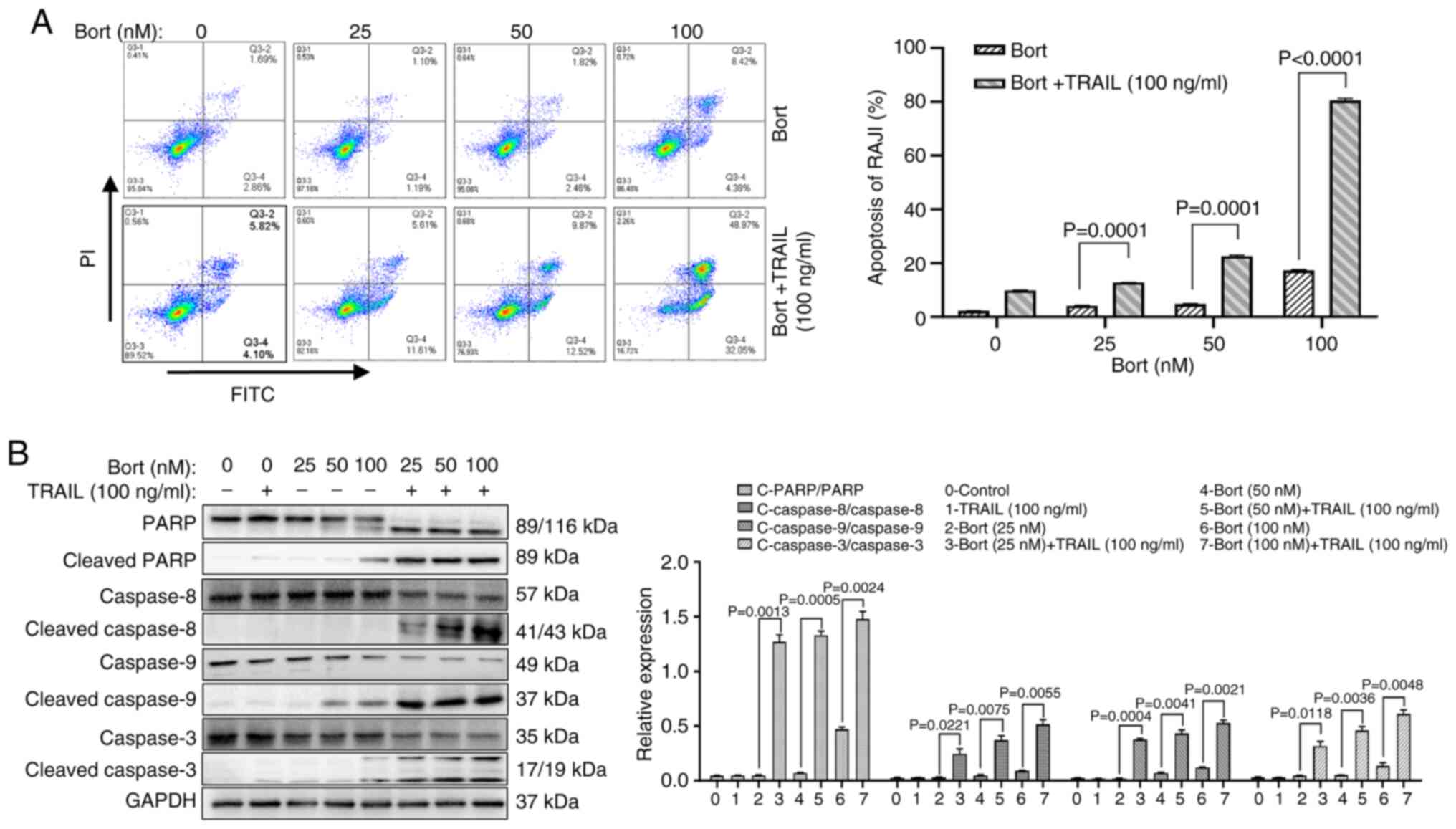

To further determine the pathway by which bortezomib

combined with TRAIL induced Raji cell death, annexin V-FITC/PI

double staining was used to detect the apoptosis of Raji cells.

Compared with that of cells treated with bortezomib alone, the

apoptosis rate of Raji cells increased significantly in a

dose-dependent manner when this was combined with 100 ng/ml TRAIL.

Specifically, the apoptosis rate rose from 12.63±0.17% for 100 nM

bortezomib alone to 80.82±0.20% for the combination treatment with

TRAIL and bortezomib (Fig. 3A).

Moreover, the expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins were

detected using western blot, and the results revealed that compared

with the bortezomib group the expression levels of PARP were

significantly decreased when TRAIL was combined with bortezomib,

and the levels of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8/9/3 were

significantly increased (P<0.05; Fig. 3B).

Bortezomib combined with TRAIL induces

the apoptosis of Raji cells via the mitochondrial apoptosis

pathway

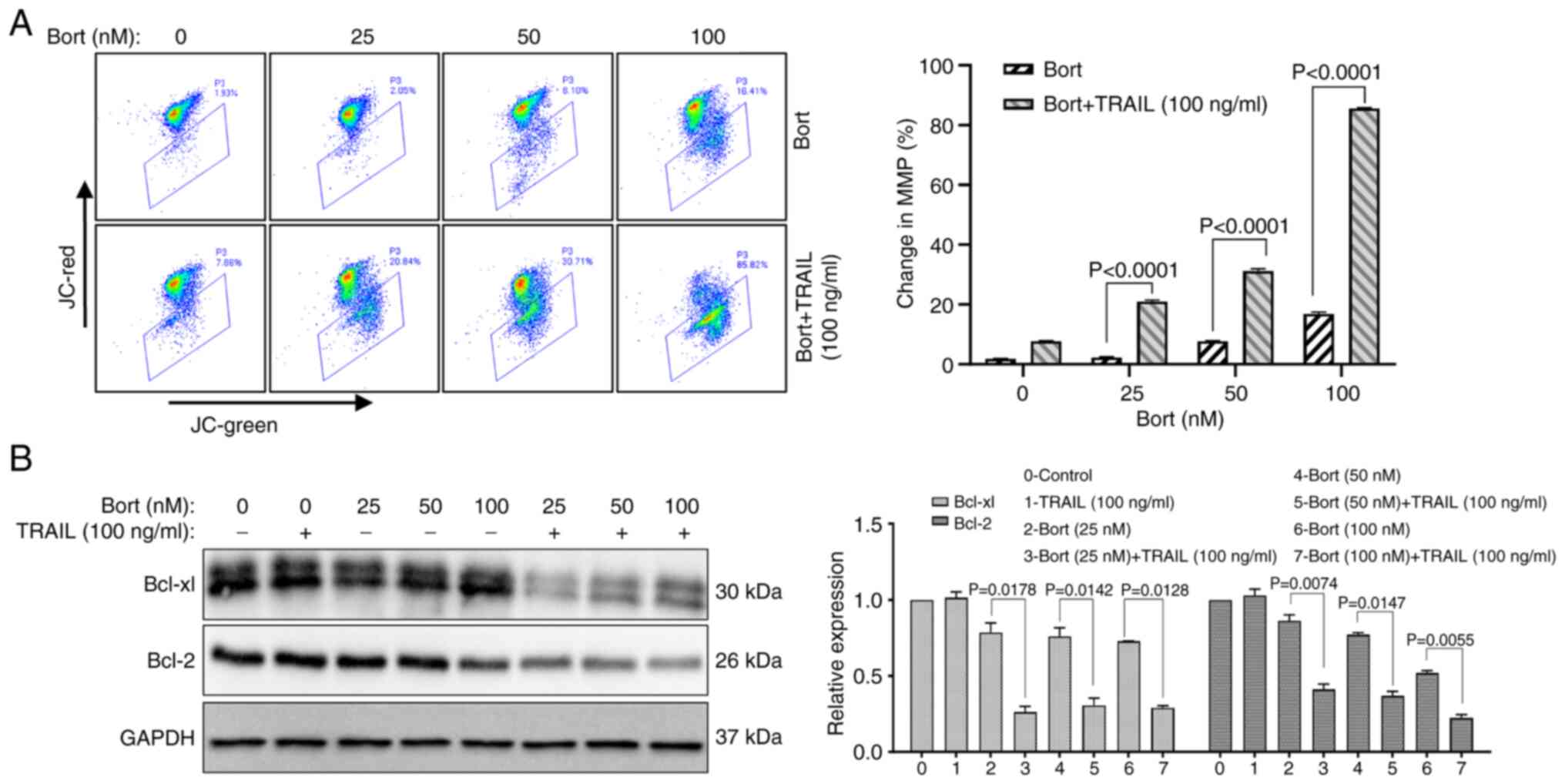

The mitochondrial pathway is an important apoptotic

pathway. To further evaluate whether the mitochondrial apoptotic

pathway is involved in the increased sensitivity of Raji cells to

TRAIL caused by bortezomib, changes of the MMP were determined

using JC-1 staining. Compared with that of the TRAIL alone group,

the MMP changed significantly from 7.71±0.15 to 85.64±0.18% when

TRAIL was combined with 100 nM bortezomib (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the western blot

analysis results revealed that compared with the bortezomib group

the expression levels of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and

Bcl-xl were significantly decreased when TRAIL was combined with

bortezomib, (P<0.05; Fig. 4B).

These results suggest that bortezomib combined with TRAIL induces

apoptosis via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.

Bortezomib combined with TRAIL induces

ROS production

ROS are considered to be potential modulators of

apoptosis (24). The combination of

TRAIL and bortezomib markedly increased ROS levels in Raji cells

from 14.45±1.11% (100 nM bortezomib) to 36.56±0.77% (TRAIL combined

with 100 nM bortezomib; Fig. 5A).

Moreover, NAC is a widely used thiol-containing antioxidant that

clears ROS from cells by interacting with OH and

H2O2, thereby affecting ROS-mediated

signaling pathways (25). The flow

cytometry results revealed that NAC pretreatment significantly

blocked the ROS production caused by bortezomib + TRAIL compared

with that in the group without NAC pretreatment (P<0.05;

Fig. 5B).

Bortezomib-induced DR5 upregulation

depends on ROS generation

DR5 is a receptor of TRAIL and serves a crucial role

in TRAIL-induced apoptosis (26).

Using staining with PE-CD262 (DR5) monoclonal antibodies, the

present study revealed that compared with control, bortezomib

significantly increased DR5 expression when in the presence of

bortezomib at 100 nM in Raji cells, from 1.60±0.50% (control group)

to 47.33±0.19% (in the presence of bortezomib at 100 nM). In

addition, NAC pretreatment significantly blocked the DR5

upregulation induced by bortezomib compared with that in the group

without NAC pretreatment (P<0.05; Fig. 6A). Furthermore, ROS generation is

associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) and CHOP, and

the CHOP motif has been identified at the proximal region of the

DR5 gene promoter (27). Western

blot results identified that compared with that of the bortezomib

group the expression levels of CHOP were significantly increased

when TRAIL was combined with bortezomib (Fig. 6B). Based on these results, it was

hypothesize that bortezomib sensitizes Raji cells to TRAIL by

activating the ROS-CHOP-DR5 signaling axis, thereby promoting their

synergistic effect in inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell

proliferation.

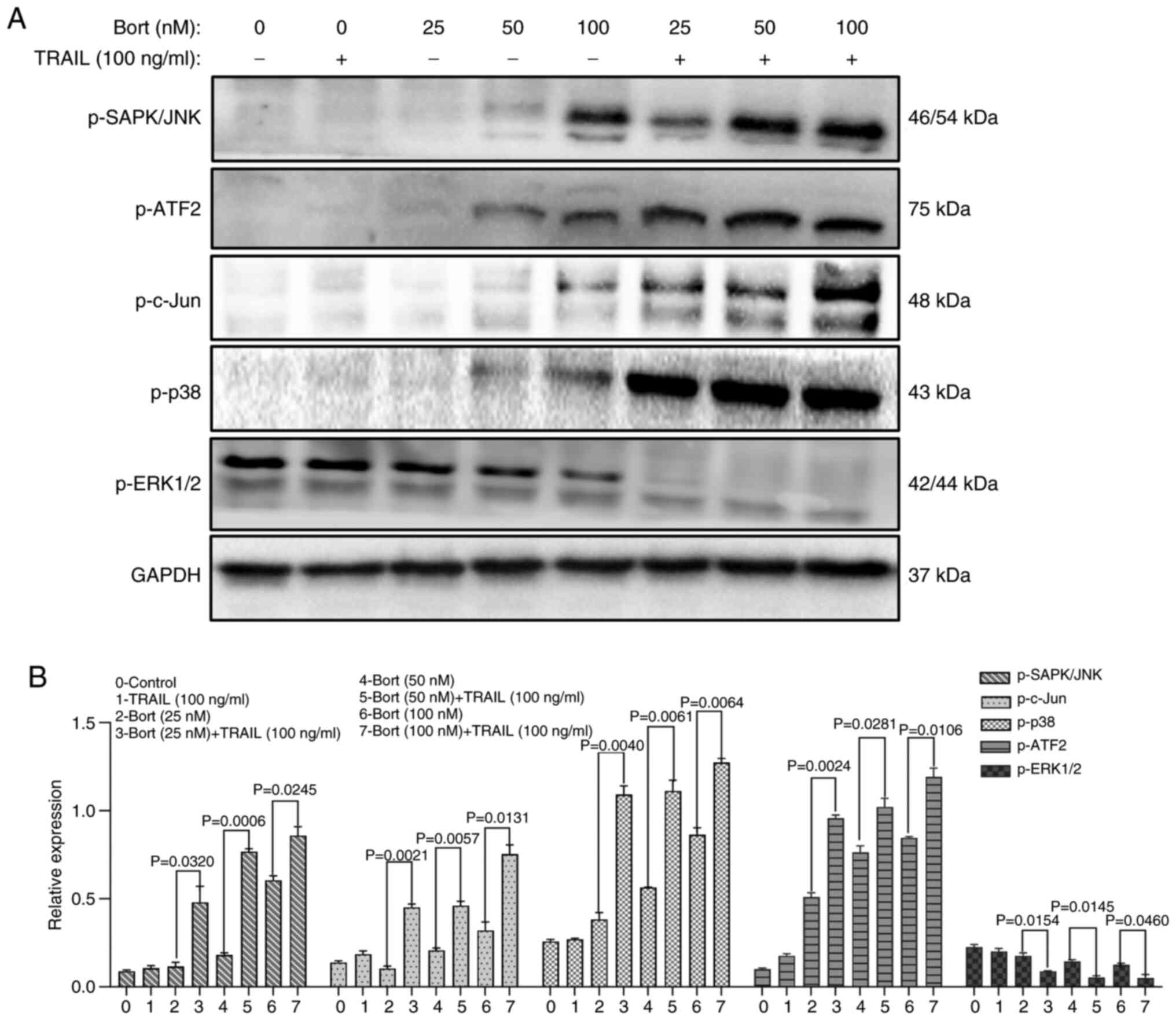

Bortezomib increases the sensitivity

of Raji cells to TRAIL through the MAPK signaling pathway

The MAPK signaling pathway can be activated by

several stimuli, regulating physiological processes such as cell

proliferation and death. It also serves an important role in the

process of apoptosis (28). To

assess the effect of bortezomib combined with TRAIL on the MAPK

signaling pathway in Raji cells, western blot was used to detect

the expression levels of MAPK signaling pathway-related proteins

(Fig. 7A). Compared with that of

the bortezomib group the levels of p-ERK1/2 in the MAPK/ERK

signaling pathway were significantly decreased, and the levels of

p-SAPK/JNK, p-c-Jun, p-ATF2 and p-p38 in the MAPK/p38 and MAPK/JNK

signaling pathways were significantly increased when TRAIL was

combined with bortezomib (P<0.05; Fig. 7B). These results suggest that

bortezomib may increase sensitivity and regulate the apoptosis of

Raji cells by activating the MAPK signaling pathway.

Discussion

TRAIL is a member of the TNF family that promotes

apoptosis, and can selectively kill tumor cells through specific

cell surface receptors, making it a promising antitumor drug.

However, in malignant lymphoma, the development of TRAIL resistance

is a major bottleneck limiting therapeutic effectiveness (9). Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor,

exhibits great therapeutic potential for sensitizing tumor cells to

TRAIL (16–18). Moreover, it has been reported that

A549 cells with acquired bortezomib resistance exhibit phenotypic

reversal of sensitivity to TRAIL (29).

Previous research has reported that the combination

of TRAIL and bortezomib was able to induce cell death in

TRAIL-resistant cancer cells via the intracellular TRAIL pathway

(17,18). Our previous study demonstrated that

BL cells have different sensitivities to TRAIL, and that the Raji

cell line is the strain with the most pronounced resistance to

TRAIL (20). Furthermore, the

present study revealed a potential synergistic effect of bortezomib

combined with TRAIL in promoting TRAIL-resistant BL cell apoptosis,

and explored its molecular mechanisms. The findings demonstrated

that bortezomib markedly increased the drug sensitivity of Raji and

CA46 cells to TRAIL. Moreover, when bortezomib was combined with

100 ng/ml TRAIL, it significantly inhibited the proliferation of BL

cells. Bortezomib also enhanced TRAIL-induced apoptosis in BL cells

in a concentration-dependent manner.

The TRAIL pathway consists of two caspase-level

pathways. After the initial activation of caspase 8 by TRAIL, the

signals differentiate in two directions: i) Direct activation of

caspase 3, without the involvement of mitochondria; and ii)

apoptotic bodies (mitochondrial proteins, dATP and Apaf-1) are

formed, resulting in the activation of caspase 9, followed by

activation of caspase 3 (30).

After bortezomib was combined with TRAIL in Raji cells, the levels

of cleaved caspase 8/9/3 were increased, and the changes of the

MMP, an important factor of mitochondrial dysfunction,

significantly decreased. It has been reported that downregulation

of Bcl-2 expression enhances the sensitivity of tumor cells to

TRAIL, and decreased intracellular Bcl-xl levels are responsible

for the acquisition of TRAIL resistance in tumor cells (31,32).

The western blot results in the present study revealed that the

expression levels of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl,

key members of the Bcl-2 family that target the mitochondrial

apoptotic pathway, were significantly decreased in Raji cells

(33). These findings suggest that

the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway serves a role in bortezomib

sensitization of Raji cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

Mitochondria are the primary sites of oxygen

utilization in eukaryotic cells. Under stress (intracellular ROS

accumulation), mitochondrial outer membrane permeability increases

and the MMP decreases, leading to the release of proapoptotic

proteins into the cytoplasm, the activation of caspases and

ultimately apoptosis (34,35). Oxidative stress serves a crucial

role as a mediator of cell death. Studies have reported that cancer

chemopreventive drugs promote ROS generation, which upregulates

DR4/DR5 and potentiates TRAIL pathway, ultimately increasing cancer

cell sensitivity to TRAIL (36,37).

Furthermore, the death receptor DR5 has an important function in

the transduction of TRAIL activity and can activate signaling

pathways associated with cell death in cancer cells (38). However, the reduced or lost

expression of DR5 in cancer cells leads to TRAIL resistance

(39). The present study

demonstrated that bortezomib combined with TRAIL could

significantly increase intracellular ROS levels and upregulate DR5

expression, whilst DR4 expression revealed no significant change

(Fig S1). Furthermore, scavenging

ROS with the antioxidant NAC abolished bortezomib-induced DR5

expression, suggesting that ROS serve a major role in the

regulation of the TRAIL receptor DR5. In addition, the present

study revealed that bortezomib combined with TRAIL enhanced the

expression of the ERS-related marker protein CHOP. ROS, key

regulators of endoplasmic reticulum function and unfolded protein

response activation, can induce apoptosis by inducing ERS and

activating the downstream effector CHOP (40,41).

It has been reported that CHOP can directly regulate the expression

of DR5 through the CHOP binding site on the 5′ side of the DR5

promoter (27). Therefore, we

hypothesize that the ROS-mediated CHOP-dependent DR5 pathway may be

involved in bortezomib-induced sensitization to TRAIL.

Additionally, it has been reported that ROS act as

upstream signaling messengers that trigger the MAPK cascade

(42), and that the MAPK signaling

pathway is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation,

differentiation, apoptosis, the inflammatory response and vascular

development in the human body. ERK, JNK and p38 kinase belong to

the most common mammalian MAPK subclass (43). Studies have reported that

dysregulation of the MAPK system alters normal physiological

processes and is frequently involved in tumorigenesis, development

and drug resistance, and thus, the MAPK system is considered to be

a viable target for cancer therapy (44,45).

It is well established that the activation of MAPK family members

(such as ERK, JNK and p38) requires dual phosphorylation, a process

in which both threonine and tyrosine residues within the activation

loop are phosphorylated by upstream kinases (MEK or MKK), resulting

in full kinase activity (46).

Accordingly, the phosphorylated forms of these kinases (such as

p-ERK, p-JNK and p-p38) serve as reliable indicators of pathway

activation. In the present study, following combination treatment

with bortezomib and TRAIL, western blot was used to assess the

expression levels of phosphorylated (activated) forms of key

proteins within the MAPK signaling pathway. However, the total

protein expression levels were not simultaneously detected due to

insufficient consideration in the experimental design. The results

revealed that the levels of p-ERK1/2 in the MAPK/ERK signaling

pathway were significantly decreased., and the levels of p-p38 in

the MAPK/p38 signaling pathway, and the levels of p-SAPK/JNK,

p-c-Jun and p-ATF2 in the MAPK/JNK signaling pathway, were

significantly increased. These findings suggest that bortezomib

enhanced the sensitivity of Raji cells to TRAIL by activating the

MAPK signaling pathway and synergistically inducing apoptosis.

In summary, the mechanism by which bortezomib

increased the sensitivity of Raji cells to TRAIL and

synergistically induced apoptosis is hypothesized to be as follows:

In Raji cells, bortezomib combined with TRAIL can increase the

level of oxidative stress, increase the level of ROS, decrease the

MMP, inhibit the expression of the antiapoptotic factor Bcl-2

family, activate the caspase cascades of caspase 8/9, caspase 3 and

PARP, and lead to the apoptosis of Raji cells through the

mitochondrial pathway. Furthermore, the increase in intracellular

ROS may trigger ERS, and then induce DR5 upregulation through the

transcription factor CHOP, thus increasing the sensitivity of Raji

cells to TRAIL. Finally, the increase in the sensitivity of Raji

cells to bortezomib may regulate the apoptosis of Raji cells by

activating the MAPK signaling pathway.

However, there are limitations of the present study:

Among TRAIL-resistant BL, the present study focused on two

representative cell lines, CA46 and Raji, which exhibited

differential sensitivity profiles. Furthermore, whilst the present

study identified the mechanism through which bortezomib sensitized

Raji cells, such as DR5 upregulation and caspase-8 activation, the

generalizability of this mechanism across other TRAIL-resistant BL

cell lines warrants further investigation. Future studies should

systematically evaluate this sensitization pathway in vivo

using xenograft mouse models to validate the therapeutic efficacy

of the bortezomib-TRAIL combination for BL treatment.

In conclusion, bortezomib appeared to increase the

sensitivity of Raji BL cells to TRAIL through ROS-dependent

upregulation of DR5, and to induce apoptosis via the MAPK signaling

pathway and the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway with synergistic

effects. This combined approach may provide a more effective and

less harmful option for the treatment of TRAIL-resistant BL.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Sichuan Science and

Technology Program of China (grant no. 2023NSFSC0725), the National

Undergraduates Innovating Experimentation Project of China (grant

nos. 202513705003, 202513705007 and 202513705022) and the Research

and Innovation Fund for Postgraduates of Chengdu Medical College of

China (grant nos. YCX2024-01-10 and YCX2023-02-04).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JC, WZ, PY and ML designed the research study. JC,

WZ, YY, YZ, SP and XB performed the experiments. JC, WZ, YY, ML and

PY analyzed the data. JC and YY confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All

authors participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be

accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Saleh K, Michot JM, Camara-Clayette V,

Vassetsky Y and Ribrag V: Burkitt and burkitt-like lymphomas: A

systematic review. Curr Oncol Rep. 22:332020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sun K, Wu H, Zhu Q, Gu K, Wei H, Wang S,

Li L, Wu C, Chen R, Pang Y, et al: Global landscape and trends in

lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies in 185 countries:

Population-based estimates from GLOBOCAN 2022. EClinicalMedicine.

83:1031932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chu Y, Liu Y, Fang X, Jiang Y, Ding M, Ge

X, Yuan D, Lu K, Li P, Li Y, et al: The epidemiological patterns of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Global estimates of disease burden, risk

factors, and temporal trends. Front Oncol. 13:10599142023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Molyneux EM, Rochford R, Griffin B, Newton

R, Jackson G, Menon G, Harrison CJ, Israels T and Bailey S:

Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 379:1234–1244. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Holmes M, Scott GB, Heaton S, Barr T,

Askar B, Müller LME, Jennings VA, Ralph C, Burton C, Melcher A, et

al: Efficacy of coxsackievirus A21 against drug-resistant

neoplastic B cells. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 29:17–29. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jacobson C and LaCasce A: How I treat

Burkitt lymphoma in adults. Blood. 124:2913–2920. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Naimi A, Movassaghpour AA, Hagh MF, Talebi

M, Entezari A, Jadidi-Niaragh F and Solali S: TNF-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) as the potential therapeutic

target in hematological malignancies. Biomed Pharmacother.

98:566–576. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lemke J, von Karstedt S, Zinngrebe J and

Walczak H: Getting TRAIL back on track for cancer therapy. Cell

Death Differ. 21:1350–1364. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu FT, Agrawal SG, Gribben JG, Ye H, Du

MQ, Newland AC and Jia L: Bortezomib blocks bax degradation in

malignant B cells during treatment with TRAIL. Blood.

111:2797–2805. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Deng L, Zhai X, Liang P and Cui H:

Overcoming TRAIL resistance for glioblastoma treatment.

Biomolecules. 11:5722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Quiroz-Reyes AG, Delgado-Gonzalez P, Islas

JF, Gallegos JLD, Garza JH and Garza-Trevino EN: Behind the

adaptive and resistance mechanisms of cancer stem cells to TRAIL.

Pharmaceutics. 13:10622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yagolovich AV, Gasparian ME, Isakova AA,

Artykov AA, Dolgikh DA and Kirpichnikov MP: Cytokine TRAIL death

receptor agonists: Design strategies and clinical prospects.

Russian Chemical Reviews. 94:RCR51542025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kundu M, Greer YE, Dine JL and Lipkowitz

S: Targeting TRAIL death receptors in triple-negative breast

cancers: Challenges and strategies for cancer therapy. Cells.

11:37172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Thorburn A, Behbakht K and Ford H: TRAIL

receptor-targeted therapeutics: Resistance mechanisms and

strategies to avoid them. Drug Resist Updat. 11:17–24. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cingoz A, Ozyerli-Goknar E, Morova T,

Seker-Polat F, Selvan ME, Gümüş ZH, Bhere D, Shah K, Solaroglu I

and Bagci-Onder T: Generation of TRAIL-resistant cell line models

reveals distinct adaptive mechanisms for acquired resistance and

re-sensitization. Oncogene. 40:3201–3216. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Robak P and Robak T: Bortezomib for the

treatment of hematologic malignancies: 15 years later. Drugs R D.

19:73–92. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bui HTT, Le NH, Le QA, Kim SE, Lee S and

Kang D: Synergistic apoptosis of human gastric cancer cells by

bortezomib and TRAIL. Int J Med Sci. 16:1412–1423. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ryu S, Ahn YJ, Yoon C, Chang JH, Park Y,

Kim TH, Howland AR, Armstrong CA, Song PI and Moon AR: The

regulation of combined treatment-induced cell death with

recombinant TRAIL and bortezomib through TRAIL signaling in

TRAIL-resistant cells. BMC Cancer. 18:4322018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kabore AF, Sun J, Hu X, McCrea K, Johnston

JB and Gibson SB: The TRAIL apoptotic pathway mediates proteasome

inhibitor induced apoptosis in primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia

cells. Apoptosis. 11:1175–1193. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Qin X, Chen Z and Chen Y: Sensitivity of

tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligands in B

lymphoma cell lines and mechanisms of apoptosis induction. J

Chengdu Med Coll. 11:413–442. 2016.

|

|

21

|

Pedre B, Barayeu U, Ezeriņa D and Dick TP:

The mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine (NAC): The emerging

role of H(2)S and sulfane sulfur species. Pharmacol Ther.

228:1079162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang X, Qiao X, Shang Y, Zhang S, Li Y, He

H and Chen SZ: RGD and NGR modified TRAIL protein exhibited potent

anti-metastasis effects on TRAIL-insensitive cancer cells in vitro

and in vivo. Amino Acids. 49:931–941. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chou TC: Drug combination studies and

their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer

Res. 70:440–446. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A and Levi-Schaffer F:

Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction.

Apoptosis. 5:415–418. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu M, Wu X, Cui Y, Liu P, Xiao B, Zhang

X, Zhang J, Sun Z, Song M, Shao B and Li Y: Mitophagy and apoptosis

mediated by ROS participate in AlCl(3)-induced MC3T3-E1 cell

dysfunction. Food Chem Toxicol. 155:1123882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim BR, Park SH, Jeong YA, Na YJ, Kim JL,

Jo MJ, Jeong S, Yun HK, Oh SC and Lee DH: RUNX3 enhances

TRAIL-induced apoptosis by upregulating DR5 in colorectal cancer.

Oncogene. 38:3903–3918. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamaguchi H and Wang HG: CHOP is involved

in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5

expression in human carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 279:45495–45502.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Han SH, Lee JH, Woo JS, Jung GH, Jung SH,

Han EJ, Park YS, Kim BS, Kim SK, Park BK, et al: Myricetin induces

apoptosis through the MAPK pathway and regulates JNK-mediated

autophagy in SK-BR-3 cells. Int J Mol Med. 49:542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

De Wilt L, Sobocki BK, Jansen G, Tabeian

H, de Jong S, Peters GJ and Kruyt F: Mechanisms underlying reversed

TRAIL sensitivity in acquired bortezomib-resistant non-small cell

lung cancer cells. Cancer Drug Resist. 7:122024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xi H, Wang S, Wang B, Hong X, Liu X, Li M,

Shen R and Dong Q: The role of interaction between autophagy and

apoptosis in tumorigenesis (Review). Oncol Rep. 48:2082022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kim HJ, Kang S, Kim DY, You S, Park D, Oh

SC and Lee DH: Diallyl disulfide (DADS) boosts TRAIL-Mediated

apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells by inhibiting Bcl-2. Food Chem

Toxicol. 125:354–360. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Fresquet V, Rieger M, Carolis C,

Garcia-Barchino MJ and Martinez-Climent JA: Acquired mutations in

BCL2 family proteins conferring resistance to the BH3 mimetic

ABT-199 in lymphoma. Blood. 123:4111–4119. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim R: Unknotting the roles of Bcl-2 and

Bcl-xL in cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 333:336–343.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Waltz F, Salinas-Giege T, Englmeier R,

Meichel H, Soufari H, Kuhn L, Pfeffer S, Förster F, Engel BD, Giegé

P, et al: How to build a ribosome from RNA fragments in

Chlamydomonas mitochondria. Nat Commun. 12:71762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lan Q, Lim U, Liu CS, Weinstein SJ,

Chanock S, Bonner MR, Virtamo J, Albanes D and Rothman N: A

prospective study of mitochondrial DNA copy number and risk of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 112:4247–4249. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jin CY, Molagoda IMN, Karunarathne W, Kang

SH, Park C, Kim GY and Choi YH: TRAIL attenuates

sulforaphane-mediated Nrf2 and sustains ROS generation, leading to

apoptosis of TRAIL-resistant human bladder cancer cells. Toxicol

Appl Pharmacol. 352:132–141. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jeong S, Farag AK, Yun HK, Jeong YA, Kim

DY, Jo MJ, Park SH, Kim BR, Kim JL, Kim BG, et al: AF8c, a

multi-kinase inhibitor induces apoptosis by activating DR5/Nrf2 via

ROS in colorectal cancer cells. Cancers (Basel). 14:30432022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lv Z, Hu J, Su H, Yu Q, Lang Y, Yang M,

Fan X, Liu Y, Liu B, Zhao Y, et al: TRAIL induces podocyte

PANoptosis via death receptor 5 in diabetic kidney disease. Kidney

Int. 107:317–331. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kim HH, Lee SY and Lee DH: Apoptosis of

pancreatic cancer cells after co-treatment with eugenol and tumor

necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancers (Basel).

16:30922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liao H, Li X, Zhang H, Yin S, Hong Y, Chen

R, Gui F, Yang L, Yang J and Zhang J: The ototoxicity of

chlorinated paraffins via inducing apoptosis, oxidative stress and

endoplasmic reticulum stress in cochlea hair cells. Ecotoxicol

Environ Saf. 284:1169362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wu M, Yao Y, Chen R, Fu B, Sun Y, Yu Y,

Liu Y, Feng H, Guo S, Yang Y and Zhang C: Effects of melatonin and

3,5,3′-Triiodothyronine on the development of rat granulosa cells.

Nutrients. 16:30852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rezatabar S, Karimian A, Rameshknia V,

Parsian H, Majidinia M, Kopi TA, Bishayee A, Sadeghinia A, Yousefi

M, Monirialamdari M and Yousefi B: RAS/MAPK signaling functions in

oxidative stress, DNA damage response and cancer progression. J

Cell Physiol. 234:14951–14965. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Lewis TS, Shapiro PS and Ahn NG: Signal

transduction through MAP kinase cascades. Adv Cancer Res.

74:49–139. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li HC, Li JY, Wang XC, Zeng M, Wu YK, Chen

YL, Kong CH, Chen KL, Wu JR, Mo ZX, et al: Network pharmacology,

experimental validation and pharmacokinetics integrated strategy to

reveal pharmacological mechanism of goutengsan on methamphetamine

dependence. Front Pharmacol. 15:14805622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ju Z, Bi Y, Gao M, Yin Y, Xu T and Xu S:

Emamectin benzoate and nanoplastics induce PANoptosis of common

carp (Cyprinus carpio) gill through MAPK pathway. Pestic Biochem

Physiol. 206:1062022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kciuk M, Gielecinska A, Budzinska A,

Mojzych M and Kontek R: Metastasis and MAPK pathways. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:38472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|