Introduction

Lung cancer, a predominant contributor to global

cancer mortality (1), manifests in

~2,206,771 new cases each year, with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

representing a substantial 39% of these cases (2). By 2020, LUAD had become the most

prevalent subtype of lung cancer worldwide, presenting an enduring

and formidable challenge to global public health efforts (3). While surgical resection remains

effective for early-stage LUAD, the prognostic assessment of

postoperative recurrence and the therapeutic options for patients

with advanced-stage LUAD remain notably limited (4). Despite recent advancements in

immunotherapy, the pronounced heterogeneity of LUAD tumors and the

intricate complexity of their microenvironments contribute to

unpredictable treatment responses (5), 5-year overall survival rates of

<20% and persistent challenge of acquired resistance (6). Consequently, the identification of

novel therapeutic targets and innovative strategies is imperative

to optimize the management of patients with LUAD (7).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), often regarded as

the cellular epicenter of protein synthesis, folding and

post-translational modification, orchestrates essential

intracellular processes (8,9). Upon exposure to extrinsic or intrinsic

stressors, the functional integrity of the ER is compromised,

precipitating ER stress (ERS), a phenomenon pervasive across

multiple tumor types, including LUAD (10,11).

ERS orchestrates the regulation of numerous malignant phenotypes in

cancer cells and exerts a profound effect on the functionality and

behavior of immune cells (12).

Notably, under the persistent activation of ERS signaling cascades,

tumor-infiltrating leukocytes not only initiate the classical

unfolded protein response (UPR), but also distinctively modulate

the transcriptional and metabolic programming of immune cells, thus

reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment (13). Therefore, strategic targeting of ERS

and its related UPR pathways holds promise in unveiling novel

therapeutic avenues to enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs) and adoptive T-cell therapies (14). Additionally, cancer cells

experiencing ERS can secrete a cascade of signaling molecules that

recruit or reprogram myeloid cells within the tumor

microenvironment (TME), thereby promoting immune modulation and

potentially impeding tumor progression (15). As research advances, ERS is

increasingly recognized as a promising therapeutic target in

oncology, although its precise mechanisms and clinical

applicability remain to be thoroughly elucidated.

Considering the critical role of genetic factors in

the pathogenesis of LUAD, genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

have emerged as robust tools for identifying LUAD-associated

genetic variations (16). The aim

of the present study was to comprehensively explore the expression

profiles of ERS-related genes (ERSGs) in LUAD and their association

with the immune microenvironment by integrating RNA sequencing

(RNA-seq) data from platforms such as Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)

and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) through sophisticated

bioinformatics approaches. By developing an ERS-related predictive

model, the aim was to provide a fresh perspective for prognostic

evaluation in patients with LUAD. The current study concentrated on

brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a potentially pivotal

gene, employing summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR)

and colocalization analyses to prioritize its relevance in LUAD,

followed by experimental validation of its expression and function,

thereby contributing to the scientific foundation for the

development of precision therapeutic strategies for LUAD (Fig. 1).

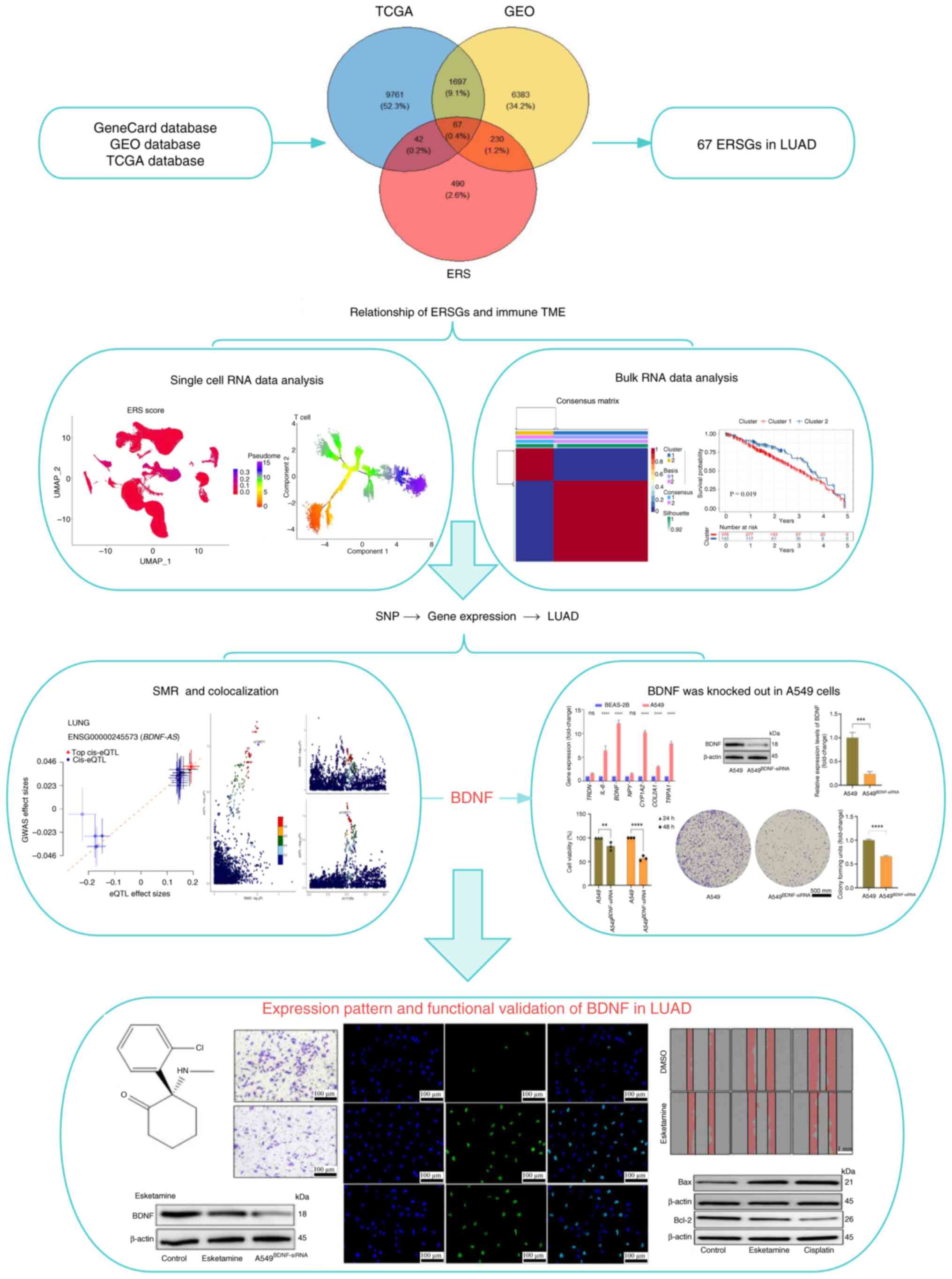

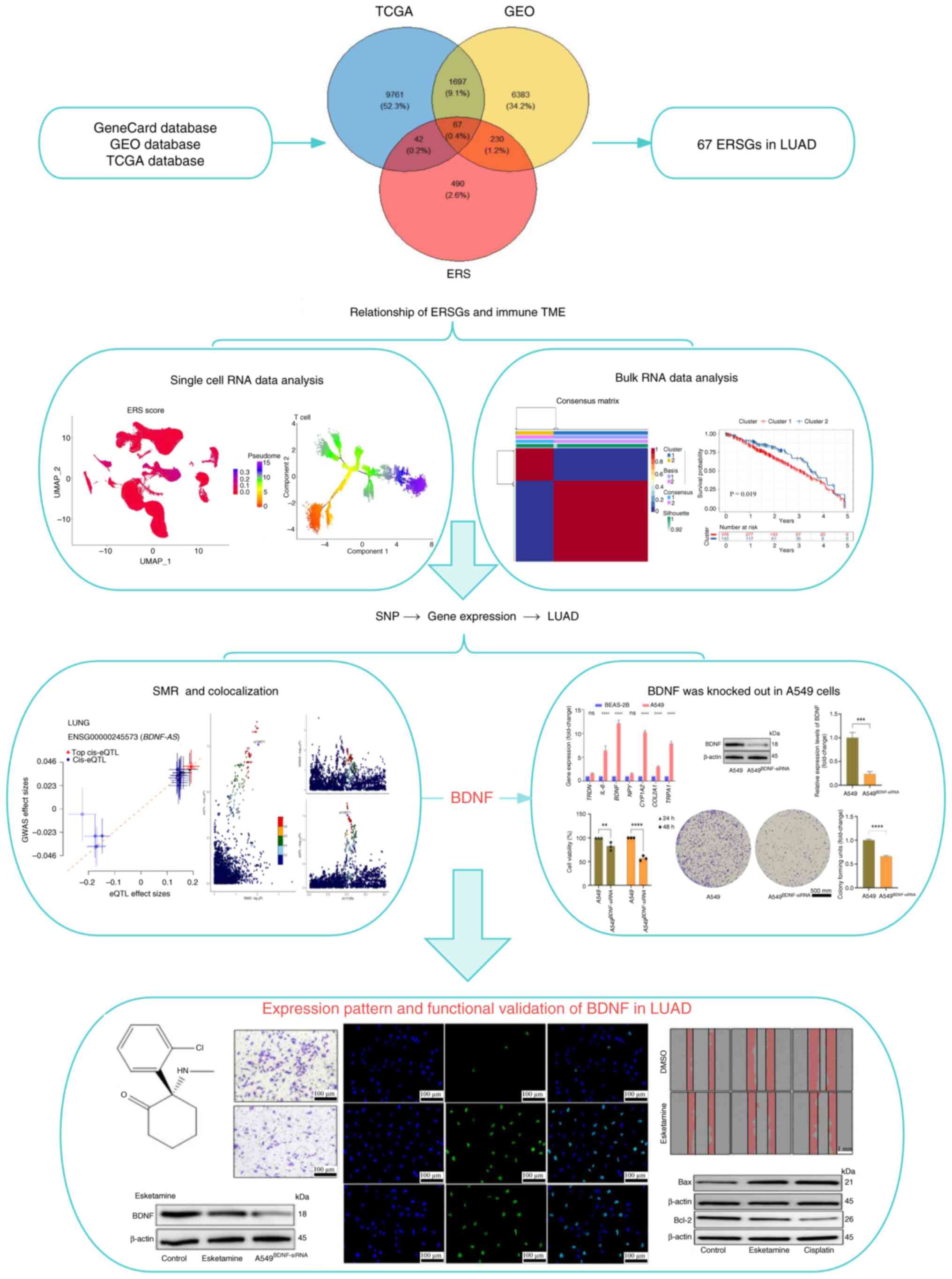

| Figure 1.The main workflow of this study. A

total of 67 ERSGs were identified by combining three databases and

the ERSGs were analyzed and determined using single-cell and bulk

RNA data. The causal relationship between BDNF and LUAD was

analyzed by SMR and colocalization. The difference of BNDF

expression and its effect on A549 cells were verified. Molecular

docking and in vitro experiments verified the effectiveness

of Esketamine in inhibiting A549 cells via downregulated BDNF

level. **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, ****P<0.001. ERSGs,

endoplasmic reticulum stress related genes; BDNF, brain-derived

neurotrophic factor; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; SMR,

summary-data-based Mendelian randomization; ERS, endoplasmic

reticulum stress; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene

Expression Omnibus; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism. |

Materials and methods

Data resources

In the present study, the gene set associated with

ERS was systematically curated from the Gene Cards database

(https://www.genecards.org/), employing

‘Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress’ as the defining keyword (17). Subsequently, the GSE139032 dataset,

which encompasses RNA expression profiles from 77 matched pairs of

LUAD and normal lung tissues, was retrieved from the GEO database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)

(18). Additionally, TCGA database,

accessed via the UCSC Xena platform (https://xena.ucsc.edu/), was used to acquire a more

extensive dataset of LUAD tumor expression profiles along with

corresponding clinical information, comprising 576 tumor samples

and clinical data from 641 patients (19). Moreover, a single-cell mRNA dataset,

GSE131907 (comprising 208,506 cells), along with an independent

LUAD validation dataset, GSE31210 (containing 226 samples), were

procured from the GEO database (20,21).

Furthermore, GWAS summary statistics from the IEU database

(ieu-a-984; http://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ieu-a-984/),

encompassing 11,245 LUAD cases and 54,619 controls, were

incorporated into the analysis.

Transcriptional profiling and pathway

exploration

To characterize transcriptional variations between

LUAD and normal pulmonary specimens, dimensionality reduction was

first performed through principal component analysis (PCA) on

RNA-seq data from TCGA cohort. The DESeq2 algorithm in R

(https://bioconductor.org/packages/DESeq2; version,

1.44.0) was subsequently employed for the rigorous identification

of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), applying stringent

thresholds of Benjamin-Hochberg adjusted P<0.05 and |log2 fold

change|>0.58. Functional annotation studies including Gene

Ontology (GO) terms categorization and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment were systematically conducted

using the cluster Profiler toolkit (https://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler;

version, 4.12.0). Prognostically relevant ERSGs were screened

through survival-associated filtration via univariate Cox

proportional hazards modeling (P<0.05). Molecular interaction

networks of these critical ERSGs were subsequently reconstructed

through STRING platform (https://string-db.org; version, 12.0) interrogation,

maintaining a minimum interaction confidence score >0.4

(Tables SI and SII).

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling

and functional dynamics

To ensure analytical robustness in processing the

GSE131907 RNA-seq dataset, multistep quality assurance procedures

were implemented. Cellular quality control thresholds excluded

outliers with transcriptome coverage <200 or >2,500 unique

gene counts, along with cells demonstrating mitochondrial read

contribution >10% (mitochondrial read fraction >10%).

Normalized expression matrices underwent nonlinear dimensionality

reduction and unsupervised clustering via the Seurat toolkit

(https://satijalab.org/seurat/; version

4.0), employing variance stabilization transformation and

graph-based clustering algorithms. Cellular subpopulations were

partitioned at a Leiden algorithm resolution parameter of 0.5,

visualized through uniform manifold approximation projection across

the first 20 principal components. Iterative marker validation

refined 11 algorithmically derived clusters into eight biologically

coherent lineages using lineage-specific canonical markers from the

Cell Marker repository. ERS activation patterns were quantified at

single-cell resolution using the Add Module Score framework

(https://satijalab.org/seurat/reference/addmodulescore;

version, Seurat v4), incorporating a curated ERSG signature.

Functional phenotyping included cytotoxicity potential estimation

via granzyme-perforin axis expression and T-cell exhaustion

profiling using programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1/PDCD1),

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 weighted indices, implemented through

the Seurat AddModuleScore function (v4.0). Intercellular signaling

topologies were reconstructed via Cell Chat (version 1.6.0;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/CellChat) with

ligand-receptor interaction probability thresholds >0.25 and

co-expression pattern validation. Developmental trajectories were

inferred through pseudotemporal ordering algorithms in Monocle3

(version 1.3; http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle3/),

incorporating branch point analysis and gene expression momentum

modeling to resolve lineage bifurcation events (Table SIII, Table SIV, Table V).

Molecular taxonomy and TME

deconvolution

To resolve the intrinsic molecular stratification of

LUAD, a consensus clustering framework was implemented through

non-negative matrix decomposition (NMF; version 0.23.0; http://pypi.org/project/nmf/) on TCGA transcriptomic

profiles, optimizing factorization rank via cophenetic coefficient

stability assessment (22).

Survival disparities among molecular subtypes were interrogated

through multivariate survival modeling (survival version 3.2;

http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html)

incorporating log-rank testing and stratified survival probability

distributions, with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals

(CI) computed for subtype-specific prognostic outcomes (23). Pathway perturbation landscapes were

mapped via bootstrapped Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; 1,000

permutations; FDR <0.1) using Hallmark gene sets, quantifying

enrichment of oncogenic signature pathways such as mTORC1 signaling

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and immune regulatory

modules (24). The TME was

computationally deconvoluted through: i) Stromal-immune

quantification, ESTIMATE algorithm (estimate version 1.1;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/estimate/)

implementation calculating four-dimensional microenvironment

indices, tumor purity, immune infiltration score, stromal

activation index and composite TME complexity metric, with batch

correction for technical covariates; ii) immune phenotyping,

relative composition: CIBERSORTx (version 1.06; http://cibersortx.stanford.edu) constrained

regression model with 22-leukocyte signature matrix, applying

P<0.05 confidence threshold for lymphocyte subset fraction

estimation. Absolute quantification: MCP-counter (version 2.2.0;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/MCPcounter) digital

cytometry-based quantitation of eight cytotoxic populations

[CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells] and two

stromal lineages (fibroblasts and endothelial cells), normalized to

transcripts per million (TPM). Immunotherapeutic vulnerability

prediction employed the TIDE framework (version 2.0.3; http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu) incorporating: i)

Tumor-associated immunosuppression markers (CTLA-4, PDCD1); ii)

exclusion signature scores (WNT/TCFβ activation); and iii)

dysfunctional T-cell infiltration patterns. A predefined TIDE

threshold (>75th percentile) identified immunotherapy-refractory

cases, validated through sensitivity analysis against alternative

predictors (TIS score, IFN-γ response signature) (Table SVI, Table SVII, Table SVIII, Table SIX, Table SX, Table SXI).

Construction of prognostic features

using machine learning

To establish robust predictive biomarkers, a

consensus machine learning architecture integrating

survival-optimized feature engineering was designed (25). The analytical workflow comprised

(26): i) Nonlinear feature

prioritization: √p, node size, 15 to quantify variable impact on

event-time distributions. Prognostically influential transcripts

were selected via variable hunting mode (var. used=‘all’) with

minimal depth thresholding; ii) High-Dimensional Regularization

(λα): The multi-algorithmic integration generated a parsimonious

transcriptional signature where: Predictors: Log2-transformed

expression values (TPM normalized); Outcomes: Right-censored

survival tuples (status indicator δ ϵ {0,1}, event time T).

Weighting: LASSO-derived β coefficients scaled by RSF variable

importance metrics. Individual risk stratification employed a

composite scoring algorithm where ω i represented stabilized

coefficients from nested cross-validation (10-fold outer; 5-fold

inner loops) and ε the baseline hazard offset. Predictive

performance validation incorporated time-dependent discrimination

analysis (time-ROC version 0.4; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/timeROC/index.html)

with trapezoidal area under the curve integration.

Bootstrap-corrected concordance index (C-index) estimation.

Decision curve analysis quantifying clinical net benefit (Table SXII, Table XIII, Table XIV).

SMR and colocalization analysis

To investigate the potential causal or pleiotropic

relationships between gene expression and LUAD, the current study

implemented SMR and colocalization analyses (27). In the SMR analysis, single

nucleotide polymorphisms were employed as instrumental variables,

with a particular emphasis on blood and colon-specific

cis-expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL). Gene expression

levels, derived from summary eQTL data, functioned as the exposure

factor, while LUAD, based on summary GWAS data, constituted the

outcome variable. SMR version 1.03 (https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/smr/) was

used to execute the analysis under default settings, with the

objective of identifying genetic factors that may modulate gene

expression and, in turn, influence LUAD risk. To enhance

specificity, the Meta-analysis of cis-eQTL in associated samples

method was employed prior to SMR to integrate Genotype-Tissue

Expression lung tissue and related cis-eQTL data, thereby

mitigating the effect of sample overlap. A stringent P-value

threshold was applied in the SMR analysis to screen for top eQTLs,

with relevant variants being searched within a 1 Mb region

surrounding the target gene. Statistical significance was

determined by Bonferroni-corrected P-values. Additionally, the

Heterogeneity in Dependent Instruments (HEIDI) test was conducted

to exclude potential effects of linkage disequilibrium, where a

P_HEIDI >0.05 was indicative of passing the heterogeneity test.

To interrogate potential pleiotropic effects at shared genomic

loci, Bayesian causal variant colocalization through the coloc

framework (version 5.2.1; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/coloc/index.html)

was implemented employing a hierarchical probabilistic model. The

analysis integrated harmonized GWAS summary statistics (MAF >1%;

imputation quality score >0.8) with cis-eQTL data (window, ±500

kb from TSS), calculating approximate Bayes factors through

adaptive quadrature integration (28).

Structural bioinformatics and

ligand-receptor profiling

Three-dimensional conformations of BDNF and

therapeutic ligands were acquired from the PubChem Compound

repository (29). A comprehensive

preprocessing protocol was implemented, including: Solvent excision

via topological analysis; Protonation state optimization at

physiological pH 7.4; Partial charge assignment using

Gasteiger-Marsili formalism and Energy minimization (AMBER ff14SB

force field; 5,000 steepest descent steps). Molecular recognition

dynamics were simulated through semi-empirical free energy

calculations in Auto Dock Tools (version 1.2.2; http://autodock.scripps.edu/resources/adt) employing:

Conformational constraint docking methodology (ligand flexibility

≤5° rotational tolerance); Grid parameterization centered on the

tyrosine kinase receptor B binding domain of BDNF and Lamarckian

genetic algorithm (250 runs; population size 300) with cluster RMSD

cutoff, 2.0. Binding thermodynamics were quantified via molecular

mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area calculations, with

intermolecular stability benchmarks defined as: Moderate affinity:

Gibbs free energy (ΔG) ≤-20.9 kJ/mol (−5.0 kcal/mol); high-affinity

molecular recognition: ΔG ≤-29.3 kJ/mol (−7.0 kcal/mol). Visual

validation of π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding networks and

hydrophobic complementarity was performed in UCSF Chimera (version

1.16; http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/) with subsequent

binding pose validation through 50 ns molecular dynamics

simulations (version 3.0) (30).

Cell model establishment

The bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells and the

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)-derived A549 cells were

commercially acquired from certified biobanking institutions

(Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Cell populations

were propagated in high-glucose DMEM/F12 hybrid medium containing

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) under standardized antibiotic prophylaxis. Continuous culture

maintenance occurred in tri-gas incubators with precisely regulated

parameters of 37±0.2°C, 5.0% CO2 and 95% relative

humidity. All cell stocks underwent mycoplasma screening prior to

experimental use, with passage numbers restricted to ≤15

generations to preserve phenotypic stability.

Cell treatment and transfection

In light of the molecular docking results

demonstrating optimal binding between Esketamine and BDNF, A549

cells were divided into control, Esketamine (16.25 µM, 24 h) and

cisplatin (5 µM, 24 h) treatment groups to assess its inhibitory

effects. For the small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

experiments, a separate group of A549 cells was transfected with

BDNF-targeting siRNA (siBDNF) or negative control siRNA (NC siRNA)

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to achieve specific protein

knockdown or serve as a transfection control, respectively. The

transfection was performed using the Lipofectamine™ 3000

Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 50 nM of either siRNA was

mixed with the reagent in opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and applied to the cells. The transfection

complex was incubated with the cells at 37°C for 6 h, after which

the medium was replaced with fresh complete growth medium.

Subsequent experimentation (including Esketamine or cisplatin

treatment) was performed 24 h after the initiation of transfection

to allow for sufficient gene knockdown. The siRNA sequences used

were as follows: siBDNF sense 5′-GCAUGGCAUUUGACACUUU-3′ and

antisense 5′-AAGUGUCAAAUGCCAUGCUG-3′; NC siRNA sense

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′ and anti-sense

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA-3′.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q) PCR

Total RNA isolation was performed with TRizol-based

purification (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. R0016)

followed by RT using Prime Script RT Master Mix (Takara Bio Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative analysis

of target transcripts was conducted on a CFX96 Real-Time system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) employing SYBR Green chemistry (cat.

no. D7268S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Expression data

normalization was carried out using GAPDH (forward primer:

5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′; reverse primer:

5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′) as the endogenous reference gene, with

baseline correction and threshold cycle determination performed by

instrument software. The standard thermal cycling conditions used

for the qPCR were: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min;

amplification (40 cycles): Denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min; melting curve analysis:

60–95°C. Primer validation included melt curve analysis and

efficiency testing (95–105%), with sequence details provided in

Table SI. Relative quantification

between experimental conditions was computed through comparative

2-ΔΔCq methodology (31).

Cell proliferation

Post-transfection cell proliferation dynamics were

evaluated through dual complementary approaches. Metabolic activity

quantification employed Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (cat.

no. C0038; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) with optical

density measurements at 450 nm using a microplate reader. For

long-term proliferation analysis, transfected cells (800–1,000

viable cells/well) were cultured in 6-well plates under standard

conditions for 14 days. Resultant colonies were fixed with 100%

methanol at room temperature for 15 min, stained with 0.5% crystal

violet (cat. no. P0099; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at

room temperature for 15 min and subjected to automated particle

analysis using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health; version 6.0)

with size exclusion criteria (>50 cells/cluster). Clonogenic

survival rates were calculated relative to untransfected

controls.

Migration analysis (Transwell

assay)

Cell migration was assessed using 8 µm-pore

polycarbonate membranes coated with matrix basement membrane

extract (Matrigel; BD Biosciences) incubated at 37°C for 1 h. A549

suspensions (1×105 cells/ml) in serum-free medium were

loaded into upper chambers, while lower chambers contained 10%

FBS-supplemented medium as chemoattractant. After 24 h of

incubation, transmigrated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

at room temperature for 20 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet

at room temperature for 15 min. A total of five random microscopic

fields (magnification, ×200) per insert were captured using an

inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti; Nikon

Corporation), with cell counts performed by two independent

investigators blinded to experimental conditions.

Wound healing assay

Confluent A549 monolayers in 35 mm culture dishes

were mechanically wounded using 200 µl pipette tips. Debris removal

was achieved through PBS washing before introducing fresh medium

containing 2% FBS. Cells were treated with Esketamine at a

concentration of 16.25 µM. For comparative purposes, parallel

experiments were performed using cisplatin at a concentration of 5

µM. Time-lapse imaging was conducted at 0, 24 and 48 h

post-wounding using an Incu Cyte S3 live-cell imaging system

(Sartorius AG). Wound closure kinetics were quantified through

image analysis software (Image Pro Plus; version 6.0; Media

Cybernetics, Inc.) using edge detection algorithms, with migration

rates expressed as percentage wound area reduction relative to

baseline measurements.

Apoptosis detection (TUNEL assay)

A549 cell apoptosis was quantified using

fluorometric TUNEL assay (cat. no. C1086; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Fixed cells were permeabilized with ice-cold 0.3%

Triton X-100/PBS, then incubated with reaction mixture containing

TdT enzyme and FITC-dUTP for 1 h at 37°C protected from light.

Nuclear counterstaining employed DAPI (1 µg/ml) with mounting in

anti-fade medium. Fluorescence signals were captured using a

confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8; Leica Microsystems, Inc.) with

standardized exposure settings. Apoptotic indices were calculated

as (TUNEL+ nuclei/DAPI + nuclei) ×100%, with positive controls

treated with DNase I and negative controls omitting TdT enzyme.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from these groups using

RIPA lysis buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. A0020). Protein concentration was determined using a

Protein Quantification Kit (BCA Assay; Abbkine Scientific Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. KTD3001) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, a standard curve was generated using BSA,

and the absorbance of samples was measured at 562 nm after

incubation at 37°C for 25 min. Equal amounts of protein (30 µg per

lane) were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide

gels (prepared using SDS-PAGE Gel Preparation Kit; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0012A) and then transferred

onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon®-P;

Merck KGaA; cat. no. ISEQ00010). The membranes were blocked with 5%

bovine serum albumin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A8020) in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl,

0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5) for 2 h at 25°C. Subsequently, the membranes

were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: Rabbit anti-BDNF (1:1,000; cat. no. GB300035), rabbit

anti-Bax (1:1,500; cat. no. GB114122), rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (1:800;

cat. no. GB154380) and rabbit anti-β-actin (1:4,000; cat. no.

GB15003), all from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd. After washing, the membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: Goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:50,000; Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A21020) for 1 h

at 25°C. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced

chemiluminescence detection reagent (SuperKine™ West Femto Maximum

Sensitivity Substrate; Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

BMU102) and captured on a chemiluminescence imaging system.

Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed using ImageJ

software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

For comparative analyses of non-normally distributed

datasets (Shapiro-Wilk test; P>0.05), non-parametric Wilcoxon

rank-sum tests were applied using the stats package in R version

4.3.0 (https://www.r-project.org/). If the

groups were independent, experimental datasets were analyzed via

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests. If the measurements were

paired/matched, experimental datasets were analyzed via paired

two-tailed Student's t-tests, with continuous variables expressed

as mean ± standard deviation. Computational workflows were executed

in RStudio incorporating the tidyverse ecosystem (https://www.tidyverse.org/; version 2.0.0), while

differential expression patterns were visualized through ggplot2

(version 3.4.2; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html)

and GraphPad Prism (version 9.0; Dotmatics; ANOVA module). For

one-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test was used. Statistical

significance thresholds followed Benjamini-Hochberg correction for

multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All the experiments were

repeated three times (n=3).

Results

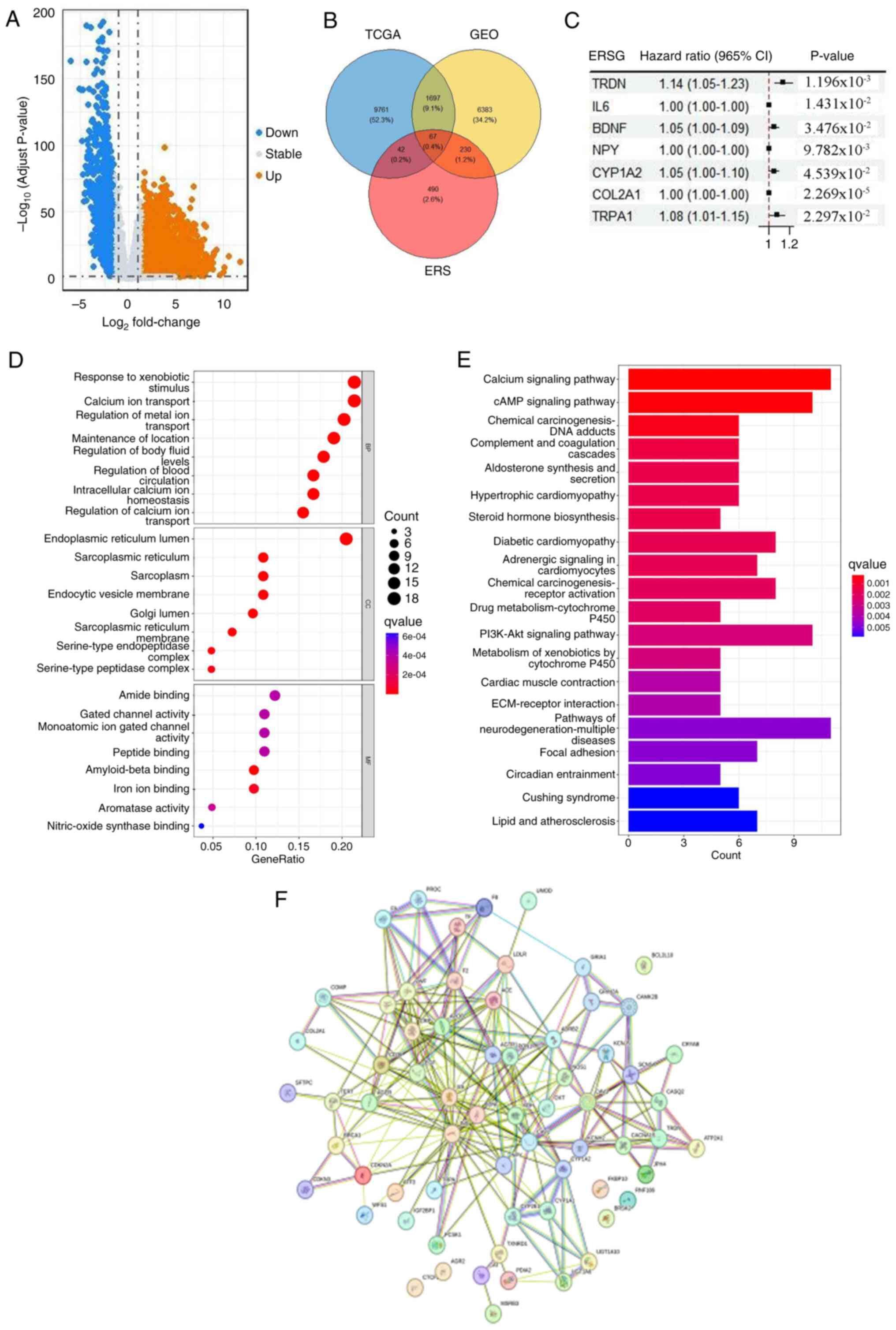

Identification of ERSGs in LUAD

The present study systematically investigated the

molecular characteristics of ERSGs in LUAD. By conducting a

comprehensive analysis of TCGA-LUAD cohort, 11,576 genes were

identified with markedly differential expression between LUAD and

normal lung tissues (Fig. 2A). To

bolster the robustness and generalizability of the findings, the

expression dataset GSE139032 from the GEO database, comprising 77

LUAD samples and 77 normal lung tissue controls, was additionally

analyzed. Through the integration of data from TCGA and GEO, and by

cross-referencing with the ERSG list from the Gene Cards database,

67 critical ERSGs were identified in LUAD, which constituted the

primary focus of the present study (Fig. 2B). Prognostic screening via Cox

proportional hazards regression (univariate analysis with Benjamini

correction) delineated seven risk-associated ERSGs, predominantly

encoding proto-oncogene products, with Kaplan-Meier validation

revealing distinct survival stratification (log-rank P<0.01;

Fig. 2C). Subsequently, GO

enrichment analysis provided deeper insights into the specific

roles of ERSGs in various biological processes, such as the

regulation of responses to external stimuli and the transport of

calcium and metal ions (Fig. 2D).

Additionally, KEGG pathway enrichment profiling (hypergeometric

test, FDR <0.05) identified topologically organized pathways

including calcium homeostasis regulation, cAMP-PKA signaling and

PI3K-Akt-mTOR cascade as core mechanisms linked to ERSGs, as

visualized through the cluster Profiler package (version 4.8.1;

Fig. 2E). Protein interactome

reconstruction using STRING version 12.0 (confidence score >0.7)

and Cytoscape Cyto Hubba plugin identified critical network hubs

(betweenness centrality >0.3), including BDNF (degree, 28), IL6

(degree, 25) and INS (degree, 22), forming a functional module

enriched in inflammatory response and growth factor binding

(Fig. 2F).

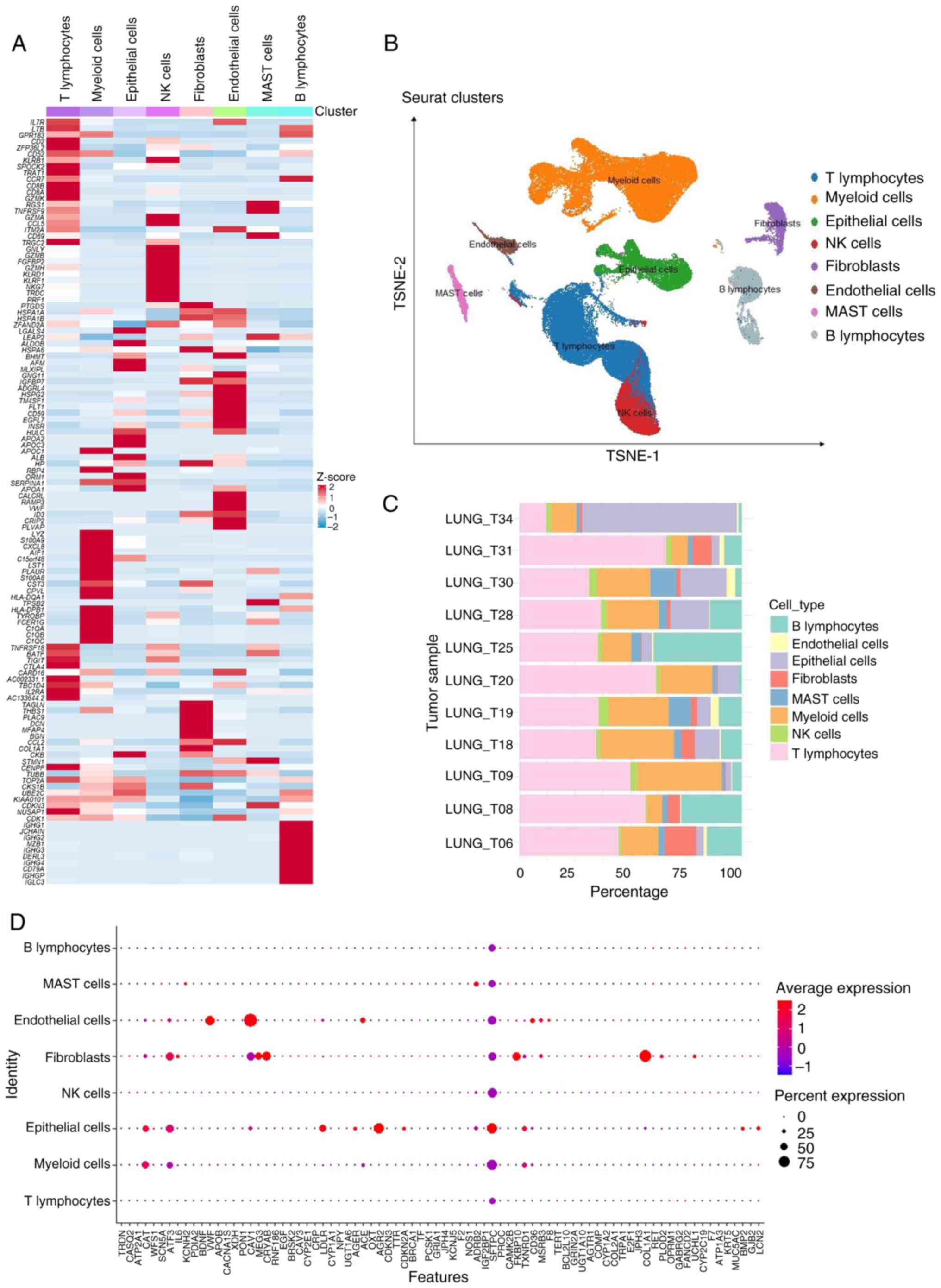

Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers the

intrinsic link between ERS-score and the TME

To investigate the specific mechanisms of ERSGs

within the TME, the current study extracted high-quality

single-cell mRNA expression profiles from the publicly available

GSE131907 dataset. Following stringent cellular quality control and

tSNE clustering analysis, 208,506 cells were isolated from 11 tumor

samples and classified into eight biologically distinct cell

clusters (Fig. 3A-C). By

integrating cluster marker genes with original cell type

annotations, eight distinct cell types were definitively

identified, including T lymphocytes (50.2%), NK cells (3.51%), B

lymphocytes (15.6%), endothelial cells (1.56%), epithelial cells

(3.05%), fibroblasts (6.47%), mast cells (2.81%) and myeloid cells

(16.8%), thereby establishing a solid foundation for subsequent

analyses. Further analysis revealed diverse expression patterns of

the 67 ERSGs across cell types, with notably higher expression in

fibroblasts and epithelial cells (Fig.

3D), implicating these cell types in the ERSG-mediated

pathological processes of LUAD. Importantly, the elevated

expression of genes such as BDNF, XDH, OXT, IGF2BP1 and CAMK2B

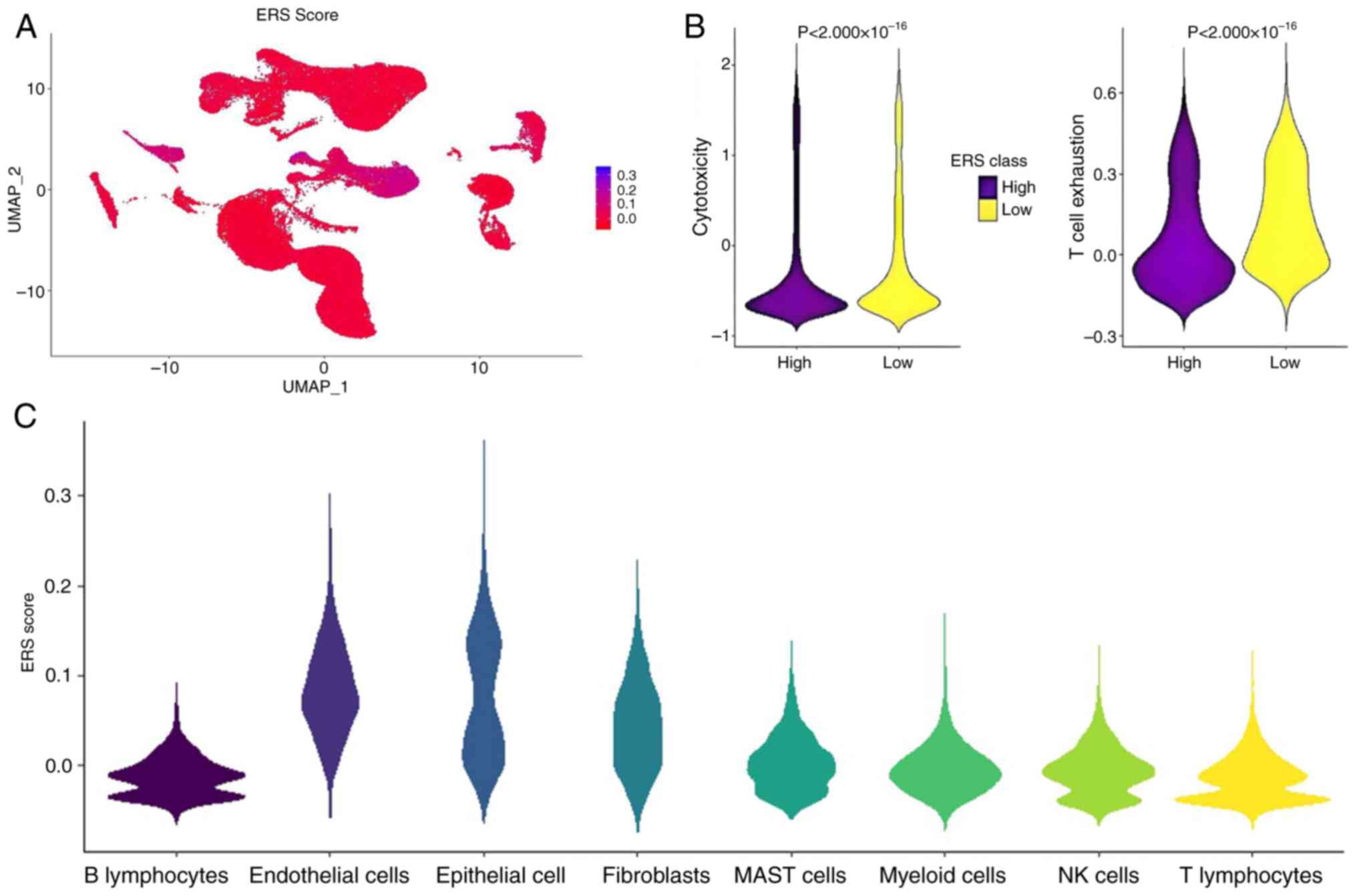

highlights their potential significance in regulating the TME. A

composite ERS activity index was computed using Seurat's Add Module

Score (n=50 control genes; scale=TRUE) with kernel density

estimation revealing bimodal distribution in epithelial cells

(Fig. 4A and C). Tertile-based

stratification (cutoff, 33rd percentile) identified high-ERS

subpopulations exhibiting enhanced cytotoxic lymphocyte

infiltration and attenuated T-cell exhaustion compared to low-ERS

counterparts (Mann-Whitney U test; Fig.

4B).

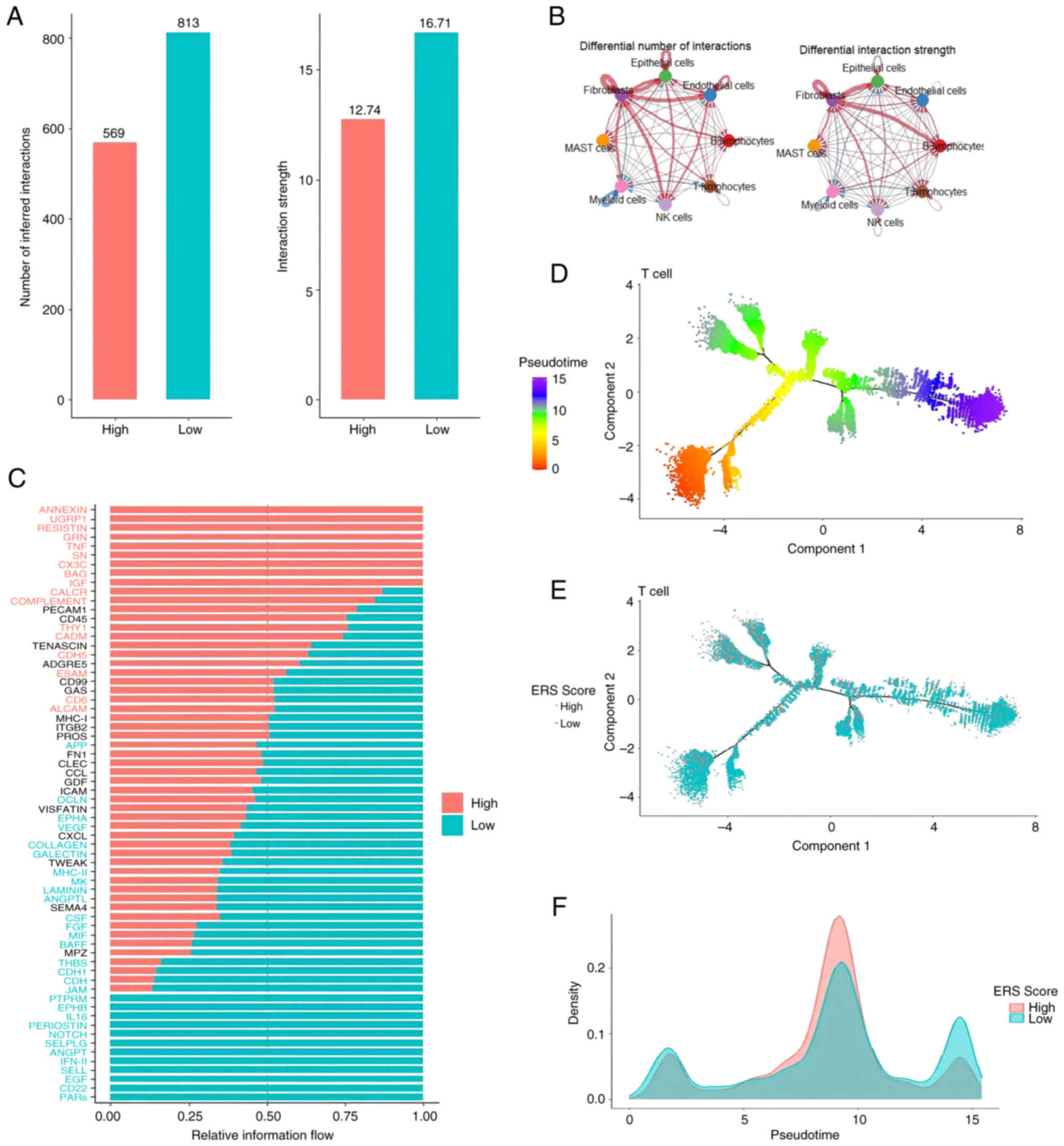

Further investigation into cell-cell interaction

differences between the two groups revealed more frequent and

stable communication within the low ERS-score group, particularly

among B lymphocytes, endothelial cells and epithelial cells

(Fig. 5A and B), potentially

reflecting a more coordinated immune response under low ERS

conditions. Moreover, signaling pathway analysis revealed

significant enrichment of the PARs pathway in the low ERS-score

group (P<0.05) and pathways involving ANNEXIN, UGRP1 and

RESISTIN in the high ERS-score group (P<0.05), offering new

insights into the specific regulatory mechanisms of ERS within the

TME (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, pseudo

time trajectory analysis of T-cell subsets revealed a significant

association between ERS-score and T-cell maturation status; early T

cells had lower ERS-scores, while late T cells exhibited higher

ERS-scores (P<0.001; Fig. 5D-F).

This finding suggested that T cells with lower ERS-scores may be at

a more mature stage, thereby executing their immune functions with

greater efficacy.

To analyze the role of ERSGs in the

molecular subtypes of LUAD based on bulk RNA-seq data

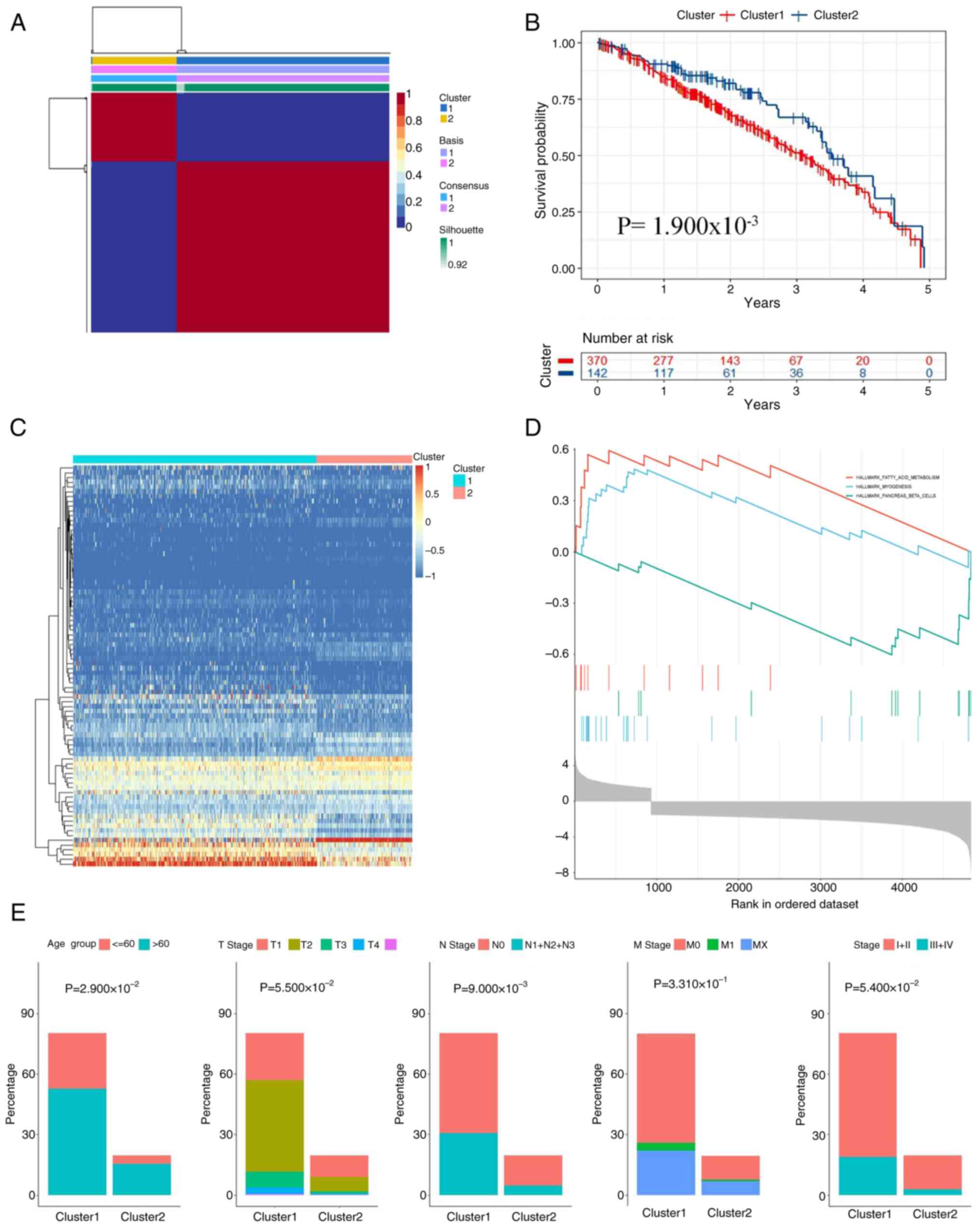

To investigate the potential roles of ERSGs in the

molecular subtypes of LUAD, the present study used TCGA-LUAD cohort

and applied the NMF algorithm to conduct a comprehensive molecular

subtyping of LUAD based on the expression profiles of 67 ERSGs. The

consensus matrix heatmap displayed distinct boundaries at

clustering number k=1, confirming the effectiveness of clustering

and ensuring the stability and reliability of the results (Fig. 6A). Consequently, LUAD cases were

stratified into two molecular clusters: i) Cluster A containing 877

individuals; and ii) cluster B including 364 subjects. Survival

evaluation demonstrated that Cluster A cases showed markedly

improved prognostic profiles relative to Cluster B counterparts

(log-rank, P=0.018; Fig. 6B).

Further analysis of ERSG expression patterns in the two subtypes

revealed a heatmap that clearly illustrated a slight downregulation

of multiple ERSGs in Subtype 1 (Fig.

6C), suggesting that these genes may have distinct roles in

different subtypes. GSEA highlighted the enrichment of tumor and

immune-related pathways and activities in Subtype 1, particularly

the activation of fatty acid metabolism, myogenesis and pancreatic

β-cell pathways, offering potential clues for the development of

subtype-specific therapeutic targets (Fig. 6D). Additionally, an in-depth

analysis of clinical features identified significant differences in

age and primary tumor stage between the two subtypes (age, P=0.029;

N Stage, P=0.009; Fig. 6E), further

highlighting the importance of molecular subtyping in precision

medicine.

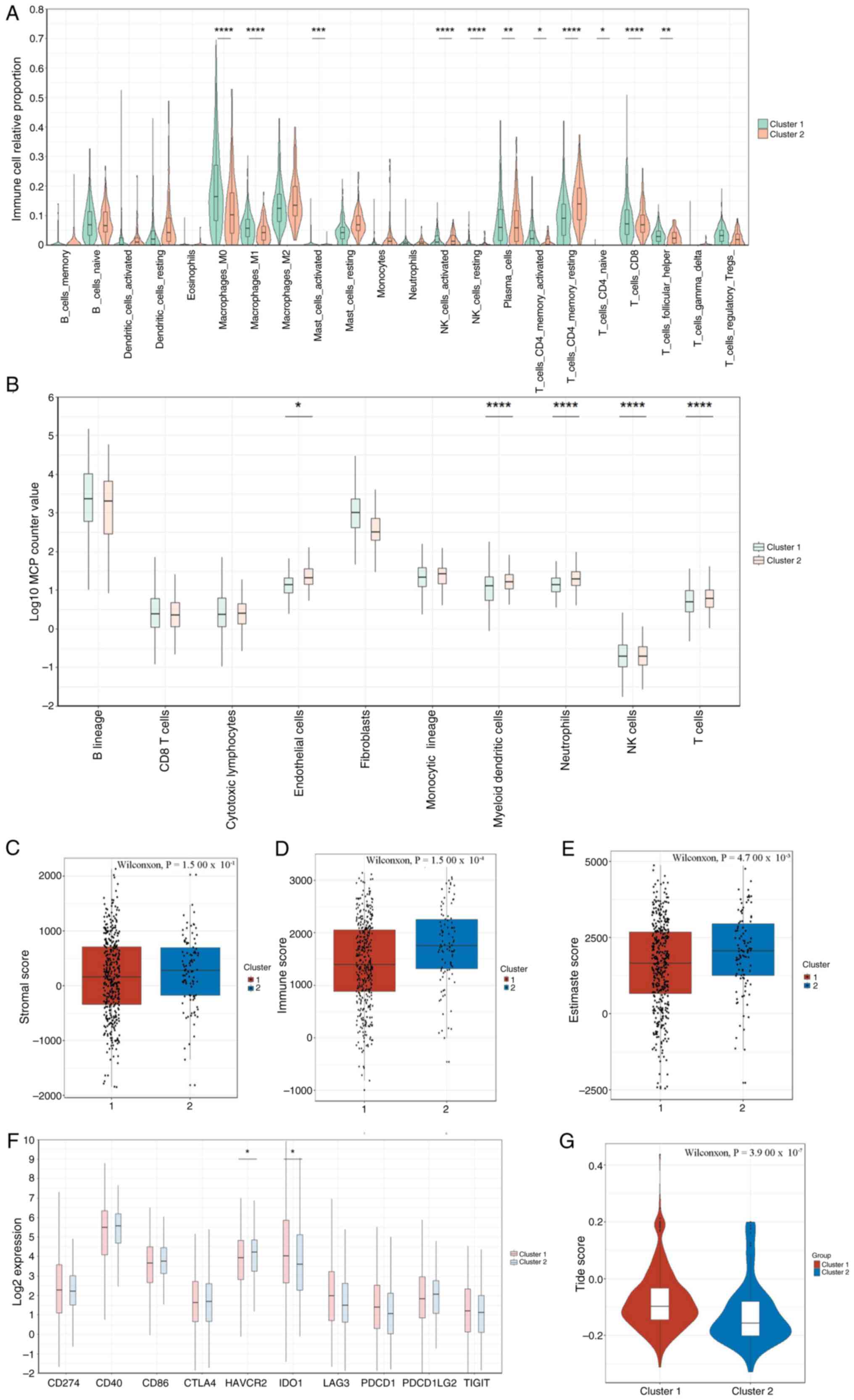

To comprehensively dissect the differences in the

immune microenvironment between the two subtypes, the present study

employed various algorithms, including CIBERSORT, MCP-Counter and

ESTIMATE. CIBERSORT analysis indicated that Subtype 1 showed higher

levels of macrophage M1 and M2, B cells, CD4+ T cells

and T-cell infiltration, while memory B cells and mast cell levels

were relatively lower (P<0.05; Fig.

7A and G). MCP-Counter results also revealed higher levels of

myeloid dendritic cells, neutrophils, NK cells and T cells in

Subtype 1 (P<0.05; Fig. 7B),

indicating a more active immune status in this subtype.

Furthermore, the ESTIMATE algorithm demonstrated markedly higher

stromal, immune and ESTIMATE scores in Subtype 2 (P<0.001;

Fig. 7C-E), which may be associated

with its more complex TME. Considering the critical therapeutic

significance of ICIs, comparative profiling of 10 immune-modulatory

targets was conducted across molecular subtypes. Differential

expression analysis revealed Cluster A displayed elevated

expression of immunoregulatory markers including HAVCR2 (log2FC,

1.8) and IDO1 (log2FC, 2.3) relative to Cluster B

(Benjamini-P<0.001; Fig. 7F).

Notably, Cluster A demonstrated markedly higher TIDE prediction

indices (Welch's t-test, P<0.001; Fig. 7E), implying enhanced ICI

responsiveness in this molecular subgroup.

Construction and validation of

ERS-related prognostic feature models

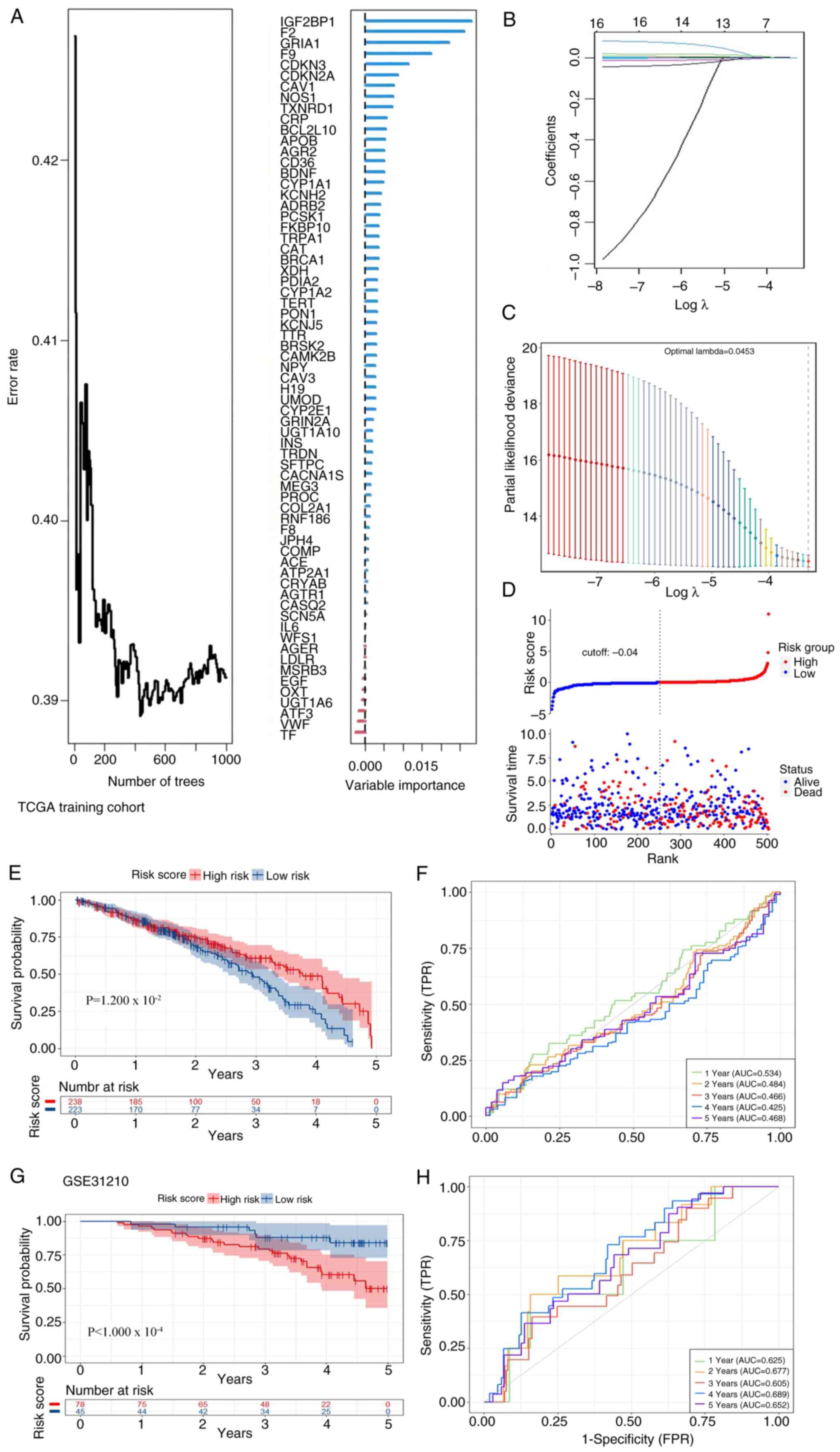

To comprehensively elucidate the potential impact of

ERSGs on the prognosis of patients with lung cancer, the current

study meticulously developed and constructed a prognostic signature

model based on ERSGs. Initially, using univariate Cox regression

analysis, genes with significant prognostic effects were

preliminarily identified from an initial pool of 67 candidate

genes. Subsequently, the RSF algorithm was employed to further

optimize gene selection, eliminating genes with low or negative

contributions to the model (Fig. 8A and

B), thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of the model.

Building on this, the LASSO regression method was used to construct

a prognostic signature model comprising 16 pivotal ERSGs (Fig. 8C and D). By integrating the

expression data of these genes, the model calculates an

individualized risk score for each patient using the following

formula: Risk Score=F9* 5.61 + F2* 0.00052 + IGF2BP1* 0.050 +

GRTA1* (−0.496) + BCL2L10 * 0.0188 + CDKN2A* (−0.0006) + CDKN3*

0.0005 + TXNRD1* 0.00006 + CAV1* 0.0001 + CAT* (−0.0002) + TRPA1*

0.020 + NOS1* 0.009 + BDNF* 0.066 + KCNH2* (−0.002) + TERT* 0.062 +

CRP* 0.008. This risk stratification algorithm provides a

quantitative metric for evaluating clinical prognosis. To verify

the discriminatory capacity of the predictive model, external

validation was performed using TCGA-LUAD (n=498) and GSE31210

(n=226) cohorts. In TCGA-LUAD, cases were dichotomized into

elevated- and reduced-risk subgroups via median risk score

thresholding. Significant survival status disparities

(χ2; 12.7) and temporal survival advantages were

observed between subgroups (Fig.

8E), corroborated by Kaplan-Meier estimator analysis (log-rank,

P=0.032; Fig. 8F). Temporal

predictive performance was quantified through ROC analysis,

yielding AUCs of 0.534 (95% CI; 0.48-0.59), 0.484 (0.43-0.54),

0.466 (0.41-0.52), 0.425 (0.37-0.48) and 0.468 (0.41-0.53) for

1–5-year intervals, respectively. Cross-cohort validation in

GSE31210 confirmed robust prognostic differentiation (log-rank,

P=1.4×10−4; Fig. 8G and

H), substantiating the pan-cohort applicability and predictive

consistency of this ERS-based prognostic classifier.

SMR and colocalization analysis

reveals the key role of BDNF in LUAD and its potential drug

target

To further investigate the ERSGs closely associated

with LUAD expression, the current study uniquely integrated SMR and

colocalization analyses. By integrating eQTL data from blood

samples with LUAD GWAS, 15 cis-eQTL probes were identified

associated with ERSGs. Notably, only the BDNF gene passed the

stringent SMR test, revealing a significant association between

BDNF and LUAD (p-SMR=0.03; P_HEIDI >0.05) (28), strongly suggesting that BDNF may

contribute to the onset and progression of LUAD through pleiotropy

or direct causality (Fig. 9A and

B). The SMR effect plot is particularly striking, as it

visually demonstrates a positive association between BDNF

expression levels and LUAD risk. To further substantiate this

finding, a colocalization analysis was conducted to assess the

colocalization of BDNF, as detected by both SMR and HEIDI tests,

between blood eQTL data and LUAD phenotypes. The analysis revealed

significant colocalization evidence between BDNF and LUAD traits

(PPH4, 0.134), strongly supporting the hypothesis that BDNF is a

critical ERSG in LUAD and underscoring the need for further

in-depth exploration of BDNF in subsequent studies (Fig. 9C).

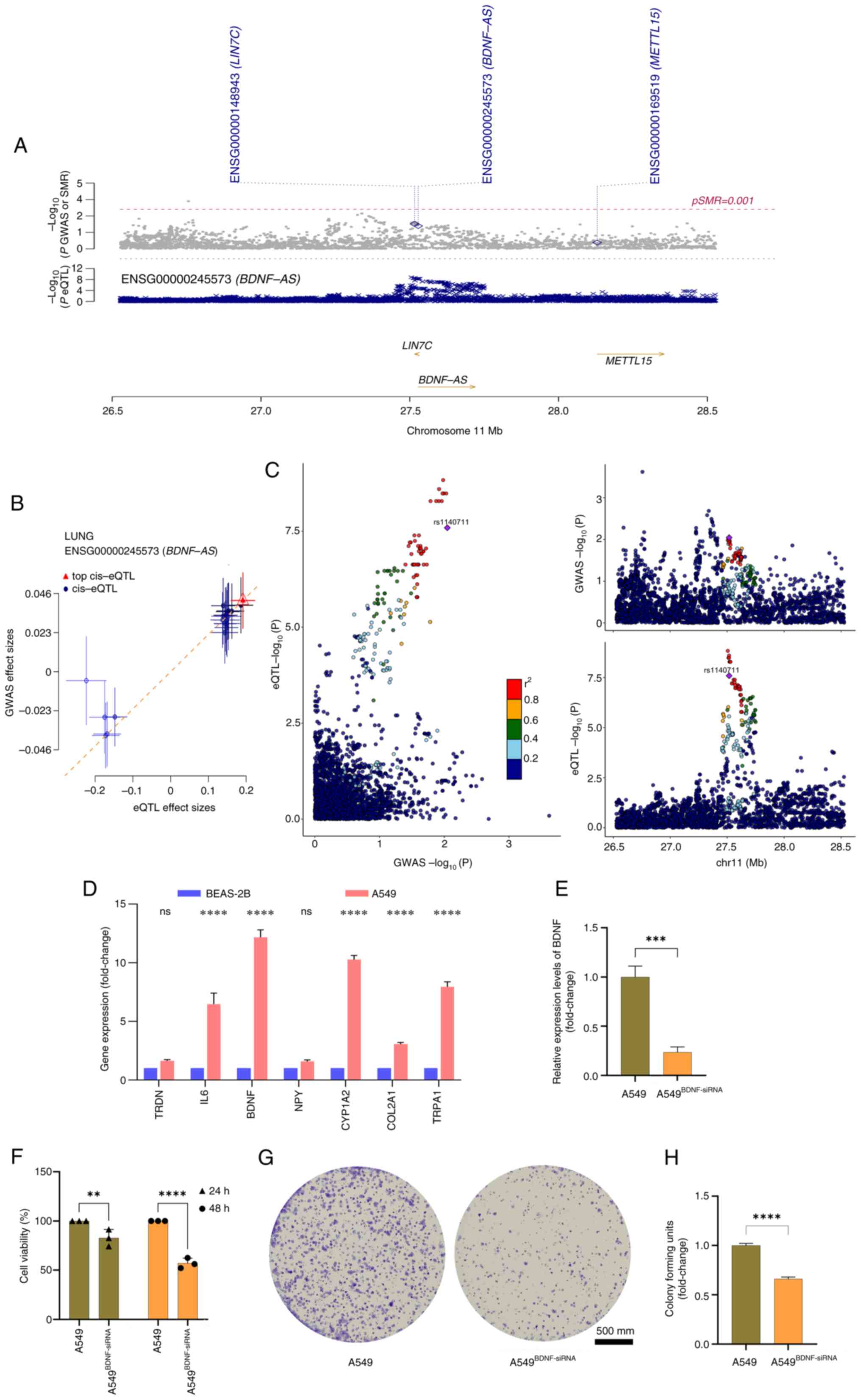

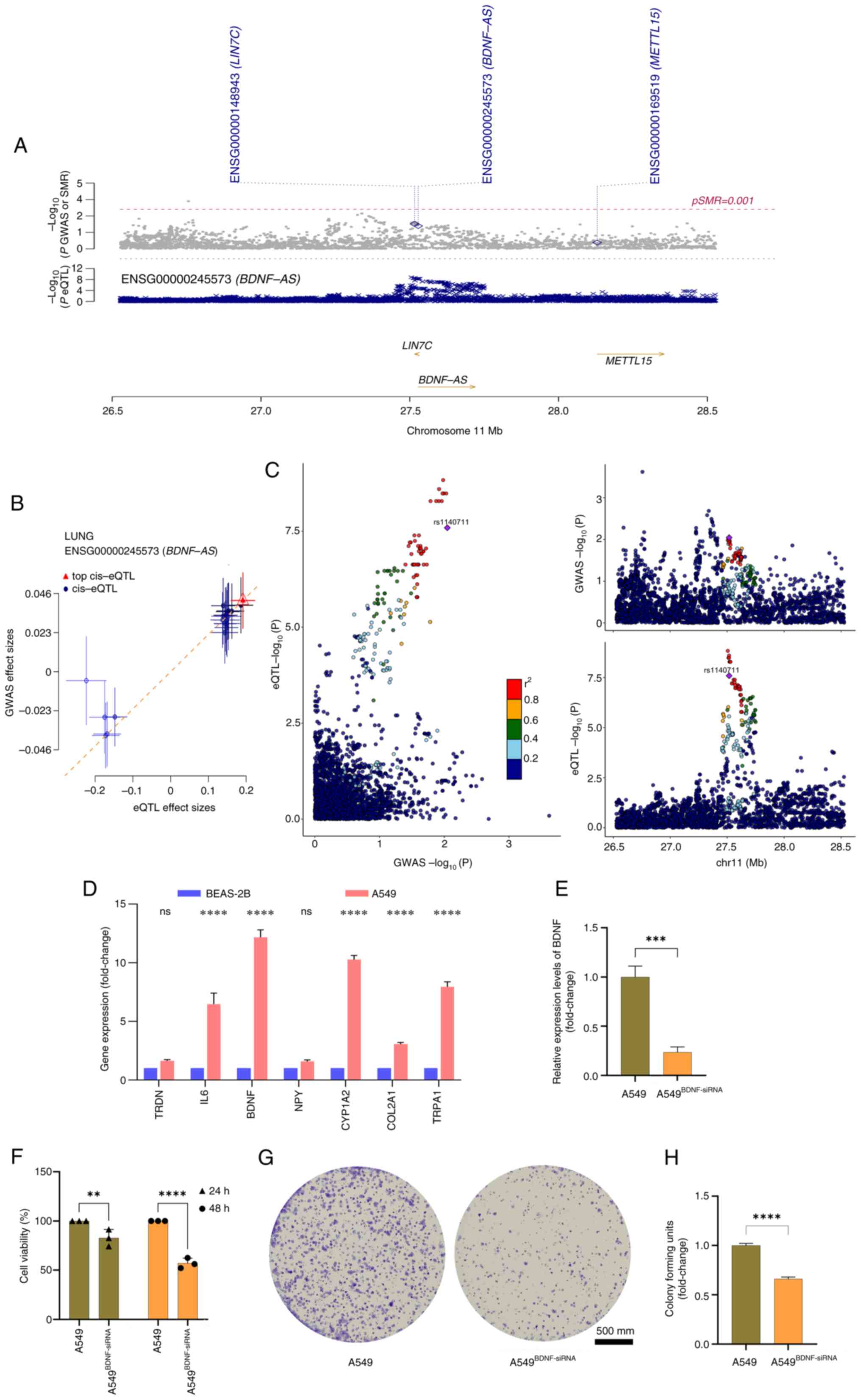

| Figure 9.Integrative genomics prioritization

of causal ERSGs. (A) SMR visualization at BDNF locus

(hg38:11p14.1). Top: Probe passing SMR-HEIDI joint test (HEIDI;

P>0.01). Bottom: GWAS variants (gray circles) vs. lung eQTLs

(red crosses, GTEx v8). (B) Causal effect estimates (Bayes

factor>10) between gene expression and LUAD risk. (C)

Colocalization probability analysis (PP.H4>0.8) showing shared

causal variants (LD, r2 color gradient; lead

variant=purple square). (D) Quantitative PCR validation of ERSGs in

A549 (malignant) vs. BEAS-2B (normal) cells (GAPDH-normalized,

triplicates), ****P<0.001. (E) BDNF silencing efficiency (siRNA

vs. scramble, ΔΔCq method), ***P<0.005. (F) Proliferation

kinetics (CCK-8 assay) at 24/48 h post-transfection, **P<0.01,

****P<0.001. (G and H) Clonogenic capacity assessment (crystal

violet staining) with quantitative histograms (triplicate

experiments, Mann-Whitney ****P<0.001). ERSGs, endoplasmic

reticulum stress related genes; SMR, summary-Mendelian

randomization; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GWAS,

genome-wide association studies; eQTLs, cis-expression quantitative

trait loci; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; siRNA, small interfering

RNA. |

In light of the potential significance of BDNF in

cancer therapy, the present study extended its scope to include

molecular docking analyses, with the objective of identifying

potential drugs targeting BDNF, building on prior studies that have

highlighted the potential of BDNF as a therapeutic target in cancer

(32). Through RT-qPCR analysis,

BDNF expression levels were compared between human NSCLC A549 cells

and normal human lung epithelial BEAS-2B cells, revealing a

significant overexpression of BDNF in A549 cells (P<0.001;

Fig. 9D). To investigate the

specific mechanisms of BDNF in LUAD, a BDNF knockdown model was

successfully established (A549BDNF-siRNA) in A549 cells using

loss-of-function experiments utilizing siRNA (33). Results of RT-qPCR confirmed the

knockdown efficiency, thereby ensuring the reliability of the

experimental model (Fig. 9E and F).

CCK-8 cell viability assays demonstrated that BDNF knockdown

markedly suppressed the proliferation of A549 cells (P<0.01;

Fig. 9G). This finding was further

corroborated by colony formation assays, which revealed a marked

decrease in the colony-forming ability of A549BDNF-siRNA cells

(P<0.05; Fig. 9H). These

molecular docking results not only offered valuable insights for

the development of targeted therapies against BDNF but also

establish a robust foundation for subsequent experimental

validation.

Expression pattern and functional

validation of BDNF in LUAD

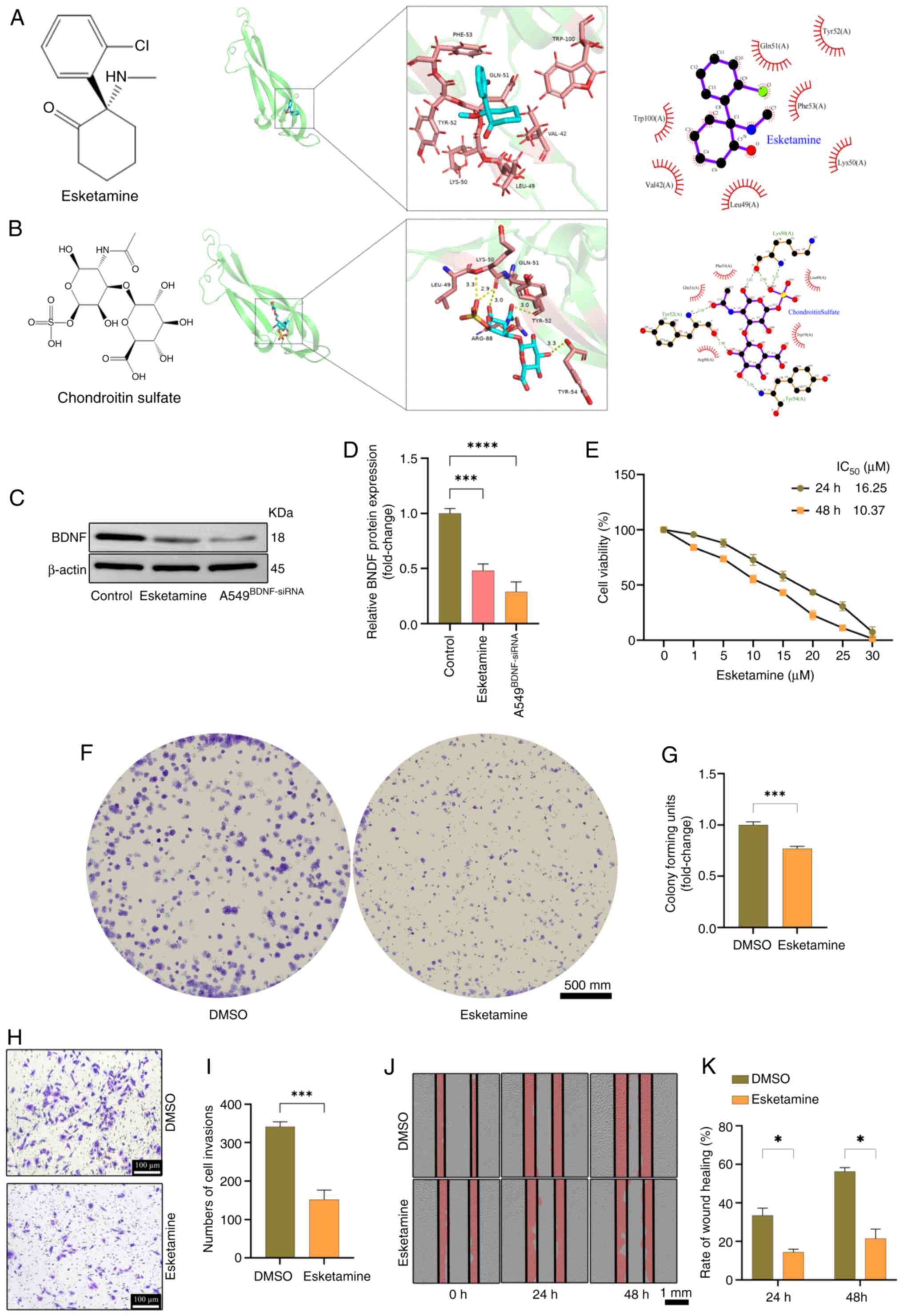

The present study sought to elucidate the expression

patterns and functional implications of BDNF in LUAD. Molecular

docking analyses of BDNF were performed with approved drugs in

Drugbank (https://go.drugbank.com/). Of the two

drugs tested, Esketamine (34)

demonstrated the most favorable binding energy (−5.3 kcal/mol),

closely followed by chondroitin sulfate (35) with a binding energy of-4.9 kcal/mol

(Fig. 10A and B). Esketamine was

selected as a potential therapeutic to investigate its effects on

A549 cells. Esketamine can downregulate the expression of BDNF

(Fig. 10C and D). The impact of

Esketamine on A549 cell proliferation was validated using CCK-8 and

colony formation assays (Fig.

10E-G). The effects of Esketamine on invasion and migration

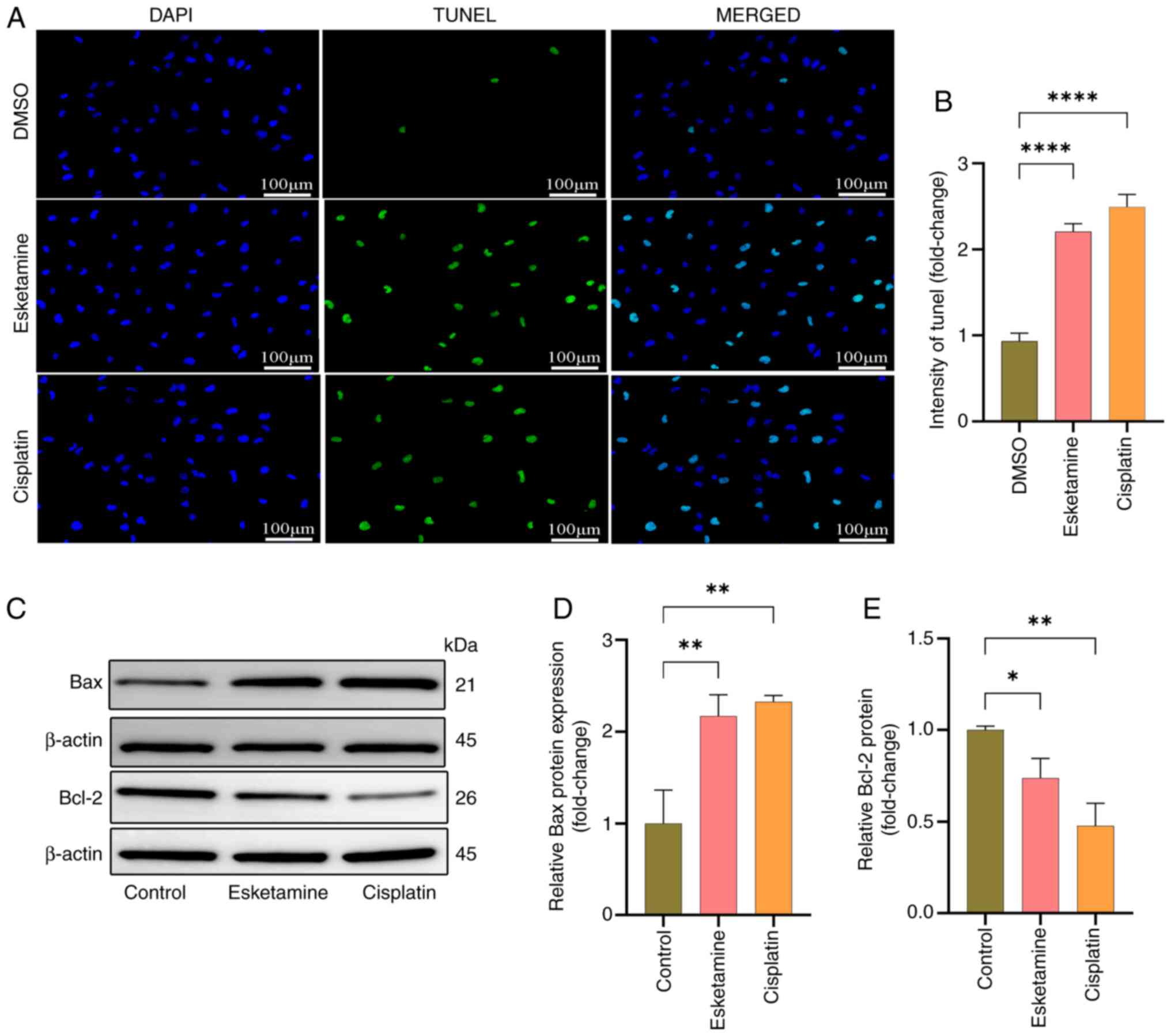

were corroborated by Transwell and wound healing assays (Fig. 10H-K). The TUNEL assay was employed

to detect the apoptotic rate of A549 cells, while western blotting

was used to assess the expression of the apoptotic marker proteins

Bax and Bcl-2, confirming that Esketamine could induce apoptosis in

A549 cells (Fig. 11). These

findings not only validate the oncogenic role of BDNF in LUAD but

also provide compelling experimental evidence for the development

of targeted therapies based on BDNF.

Discussion

In light of the critically low 5-year survival rate

of <20% among patients with LUAD (36), there is an urgent need to explore

innovative and efficacious therapeutic strategies to enhance

patient prognosis. Emerging research highlights that the TME,

serving as a critical nexus for malignant tumor progression and

immune cell infiltration, instigates substantial ERS. This process

not only orchestrates tumor growth and metastasis but also exerts a

profound influence on the efficacy of antitumor immune responses

(37). Consequently, the precise

modulation of ERS to induce direct tumoricidal effects and

potentiate antitumor immune responses presents novel therapeutic

avenues for LUAD treatment (38).

Building on existing research and the comprehensive analysis

undertaken in the present study, it is strongly contended that

ERSGs occupy a central role in delineating the characteristics of

the TME and in predicting prognosis for patients with LUAD.

The current study adeptly integrated a spectrum of

biological analysis strategies to systematically elucidate the

specific expression patterns of ERSGs in LUAD samples. By

harnessing authoritative database resources such as GEO, TCGA and

Gene Cards, 67 ERSGs were screened and identified. Through an

exhaustive analysis of single-cell sequencing and bulk RNA

transcriptome data, it was not only revealed the differential

expression profiles of ERSGs in LUAD samples, but also their robust

associations with LUAD using SMR and colocalization analyses were

substantiated. This multi-layered, multi-dimensional approach

effectively mitigated data noise and bias, thereby providing robust

data support for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms

underlying the role of ERSGs in LUAD progression.

Notably, the heterogeneity of the TME exerts a

profound influence on the efficacy of immunotherapy (39), with varying ERSG expression levels

emerging as pivotal determinants shaping immune responses within

this intricate milieu (40). The

present study revealed that elevated ERSG expression is frequently

associated with diminished immune activity, characterized by

disrupted immune cell interactions and aggravated T-cell

exhaustion. Genomic instability in LUAD promotes sustained ERS,

activating the UPR and selectively upregulating pro-survival ERSGs

such as BDNF. This creates a permissive microenvironment for tumor

progression. Specifically, cell populations with elevated

ERS-scores exhibited heightened cytotoxicity and attenuated T-cell

exhaustion, further corroborating the critical role of ERSGs in

orchestrating the TME. Furthermore, molecular subtype analysis

based on RNA data uncovered a positive association between

subgroups with low ERSG expression and increased levels of immune

cell infiltration, implying that ERSGs could serve as potential

targets for modulating tumor immune evasion.

To accurately identify pivotal molecules among

ERSGs, the current study used SMR and colocalization analyses,

concentrating on eQTL data of ERSGs in blood, ultimately

pinpointing BDNF as the central gene within this group. The

combined validation through SMR and colocalization analyses not

only confirmed the significant expression of BDNF in LUAD samples,

but also demonstrated its strong colocalization with LUAD traits,

further underscoring the prominence of BDNF as a research priority

among ERSGs. BDNF, as a multifunctional protein, is widely

acknowledged for its central role in the regulation of apoptosis

(41). Previous studies have

indicated that BDNF facilitates tumor cell proliferation and

invasion by activating the TrkB/PLCγ1 signaling pathway (42). While BDNF acts as a tumor suppressor

in neuroblastoma through TrkB-induced differentiation, its role in

LUAD is distinctly oncogenic. This divergence likely stems from

LUAD-specific ERS hyperactivation, where chronic UPR reprograms

BDNF into a pro-survival factor, corroborated by the observation of

BDNF/ERSG co-amplification exclusively in LUAD. The present study

validated BDNF overexpression in LUAD through cell experiments and

demonstrated that BDNF knockdown markedly inhibited various

malignant biological behaviors of LUAD cells, including

proliferation, migration and clonogenicity, thereby corroborating

the SMR and colocalization findings and reinforcing the potential

of BDNF as a therapeutic target. Moreover, molecular docking

analysis identified clinically approved drugs such as Esketamine

and cisplatin as promising candidates for inhibiting BDNF

expression and promoting apoptosis in LUAD cells, thereby offering

new avenues for targeted therapeutic strategies.

Although the current study has made significant

progress, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, analyses

based on limited database samples may introduce certain biases.

Second, SMR and colocalization analyses did not encompass the

entirety of ERSG probe data, potentially leading to the omission of

key genes. While Esketamine demonstrates potent anti-BDNF effects,

its non-selective NMDA receptor antagonism may cause dose-dependent

neurotoxicity or dissociative effects in clinical settings. Future

work should explore tumor-targeted delivery systems to mitigate

systemic exposure risks. Clinical pharmacokinetic data confirm the

rapid distribution and hepatic clearance of Esketamine, aligning

with Q3W dosing regimens in ongoing oncology trials. While NMDA

receptor binding may cause dissociation, tumor-targeted liposomal

delivery reduced neurotoxicity 4-fold in PDAC models without

compromising BDNF inhibition. Future research should endeavor to

expand sample sizes, refine analytical methods and delve deeper

into the comprehensive mechanisms of ERSGs in LUAD. Additionally,

conducting in vivo experiments to validate in vitro

findings will be an essential step in advancing ERSG research

towards clinical application.

The present study investigated the role of ERSGs in

LUAD through a multi-omics integrated analysis and, in conjunction

with experimental validation, identified the potential therapeutic

value of the BDNF gene and the BDNF-inhibiting drug Esketamine in

hindering the progression of LUAD.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Second Batch of

Traditional Chinese medicine Backbone Talent Training Object

Project in Hunan Province during the 14th Five-Year Plan period

(grant no. 202403), The Natural Science Foundation of Hunan

province (grant no. 2022JJ4414) and Key Project of Hunan Province

Traditional Chinese Medicine Research plan (grant no. 2021206).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

XD, YT, GT and HN conceived and designed the study

and contributed to the acquisition of research materials. XD and YT

performed the experiments and conducted the statistical analysis.

XD, YT, GT and HN participated in data interpretation and were

involved in drafting the manuscript, critically revising it for

important intellectual content. The study was supported by funding

obtained by XD, GT and YT. XD and YT confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors agree to be accountable for all

aspects of the work. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang Y, Vaccarella S, Morgan E, Li M,

Etxeberria J, Chokunonga E, Manraj SS, Kamate B, Omonisi A and Bray

F: Global variations in lung cancer incidence by histological

subtype in 2020: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol.

24:1206–1218. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bi KW, Wei XG, Qin XX and Li B: BTK Has

potential to be a prognostic factor for lung adenocarcinoma and an

indicator for tumor microenvironment remodeling: A study based on

TCGA data mining. Front Oncol. 10:4242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Succony L, Rassl DM, Barker AP, McCaughan

FM and Rintoul RC: Adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions of the lung:

Detection, pathology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev.

99:1022372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu J, Zhang Y, Li M, Shao Z, Dong Y, Li Q,

Bai H, Duan J, Zhong J, Wan R, et al: A single-cell characterised

signature integrating heterogeneity and microenvironment of lung

adenocarcinoma for prognostic stratification. EBioMedicine.

102:1050922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sun R, Hou Z, Zhang Y and Jiang B: Drug

resistance mechanisms and progress in the treatment of EGFR-mutated

lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 24:4082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang Y, Liu B, Min Q, Yang X, Yan S, Ma Y,

Li S, Fan J, Wang Y, Dong B, et al: Spatial transcriptomics

delineates molecular features and cellular plasticity in lung

adenocarcinoma progression. Cell Discov. 9:962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

McLaughlin M and Vandenbroeck K: The

endoplasmic reticulum protein folding factory and its chaperones:

New targets for drug discovery? Br J Pharmacol. 162:328–345. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Saaoud F, Lu Y, Xu K, Shao Y, Praticò D,

Vazquez-Padron RI, Wang H and Yang X: Protein-rich foods, sea

foods, and gut microbiota amplify immune responses in chronic

diseases and cancers-targeting PERK as a novel therapeutic strategy

for chronic inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and

cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 255:1086042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Oakes SA: Endoplasmic reticulum stress

signaling in cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 190:934–946. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lin L, Lin G, Lin H, Chen L, Chen X, Lin

Q, Xu Y and Zeng Y: Integrated profiling of endoplasmic reticulum

stress-related DERL3 in the prognostic and immune features of lung

adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 13:9064202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen X and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment.

Nat Rev Cancer. 21:71–88. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE and

Glimcher LH: Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of

endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer. Cell. 168:692–706. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cao T, Zhang W, Wang Q, Wang C, Ma W,

Zhang C, Ge M, Tian M, Yu J, Jiao A, et al: Cancer SLC6A6-mediated

taurine uptake transactivates immune checkpoint genes and induces

exhaustion in CD8+ T cells. Cell. 187:2288–2304.e27.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fan C, Yang Y, Liu Y, Jiang S, Di S, Hu W,

Ma Z, Li T, Zhu Y, Xin Z, et al: Icariin displays anticancer

activity against human esophageal cancer cells via regulating

endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptotic signaling. Sci Rep.

6:211452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang L, Xiong Y, Zhang J, Feng Y and Xu

A: Systematic proteome-wide Mendelian randomization using the human

plasma proteome to identify therapeutic targets for lung

adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med. 22:3302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Deng B, Liao F, Liu Y, He P, Wei S, Liu C

and Dong W: Comprehensive analysis of endoplasmic reticulum

stress-associated genes signature of ulcerative colitis. Front

Immunol. 14:11586482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Qiu WR, Qi BB, Lin WZ, Zhang SH, Yu WK and

Huang SF: Predicting the lung adenocarcinoma and its biomarkers by

integrating gene expression and DNA methylation data. Front Genet.

13:9269272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang S, Xiong Y, Zhao L, Gu K, Li Y, Zhao

F, Li J, Wang M, Wang H, Tao Z, et al: UCSCXenaShiny: an R/CRAN

package for interactive analysis of UCSC Xena data. Bioinformatics.

38:527–529. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang Z, Wang Y, Chang M, Wang Y, Liu P, Wu

J, Wang G, Tang X, Hui X, Liu P, et al: Single-cell transcriptomic

analyses provide insights into the cellular origins and drivers of

brain metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma. Neuro Oncol.

25:1262–1274. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Huang J, Zhang J, Zhang F, Lu S, Guo S,

Shi R, Zhai Y, Gao Y, Tao X, Jin Z, et al: Identification of a

disulfidptosis-related genes signature for prognostic implication

in lung adenocarcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 165:1074022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wu F, Cai J, Wen C and Tan H: Co-sparse

non-negative matrix factorization. Front Neurosci. 15:8045542022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhu S, Zheng Z, Hu W and Lei C:

Conditional cancer-specific survival for inflammatory breast

cancer: Analysis of SEER, 2010 to 2016. Clin Breast Cancer.

23:628–639.e2. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Qin Y, Liu Y, Xiang X, Long X, Chen Z,

Huang X, Yang J and Li W: Cuproptosis correlates with

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment based on pan-cancer

multiomics and single-cell sequencing analysis. Mol Cancer.

22:592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang Q, Qiao W, Zhang H, Liu B, Li J, Zang

C, Mei T, Zheng J and Zhang Y: Nomogram established on account of

Lasso-Cox regression for predicting recurrence in patients with

early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol.

13:10196382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Song M, Zhang Q, Song C, Liu T, Zhang X,

Ruan G, Tang M, Xie H, Zhang H, Ge Y, et al: The advanced lung

cancer inflammation index is the optimal inflammatory biomarker of

overall survival in patients with lung cancer. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 13:2504–2514. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhai T: Druggable genome-wide Mendelian

randomization for identifying the role of integrated stress

response in therapeutic targets of bipolar disorder. J Affect

Disord. 362:843–852. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shao Y, Wang Z, Wu J, Lu Y, Chen Y, Zhang

H, Huang C, Shen H, Xu L and Fu Z: Unveiling immunogenic cell

death-related genes in colorectal cancer: an integrated study

incorporating transcriptome and Mendelian randomization analyses.

Funct Integr Genomics. 23:3162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bisht A, Tewari D, Kumar S and Chandra S:

Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics

simulation to elucidate the mechanism of anti-aging action of

Tinospora cordifolia. Mol Divers. 28:1743–1763. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jaganathan R and Kumaradhas P: Binding

mechanism of anacardic acid, carnosol and garcinol with PCAF: A

comprehensive study using molecular docking and molecular dynamics

simulations and binding free energy analysis. J Cell Biochem.

124:731–742. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhu Y, Zhang C and Zhao D, Li W, Zhao Z,

Yao S and Zhao D: BDNF Acts as a prognostic factor associated with

tumor-infiltrating Th2 cells in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Dis

Markers. 2021:78420352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu L, Zhou S, Hong W, Lin N, Wang Q and

Liang P: Characterization of an endoplasmic reticulum

stress-associated lncRNA prognostic signature and the

tumor-suppressive role of RP11-295G20.2 knockdown in lung

adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 14:122832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang T, Weng H, Zhou H, Yang Z, Tian Z, Xi

B and Li Y: Esketamine alleviates postoperative depression-like

behavior through anti-inflammatory actions in mouse prefrontal

cortex. J Affect Disord. 307:97–107. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Siebert JR and Osterhout DJ: Select

neurotrophins promote oligodendrocyte progenitor cell process

outgrowth in the presence of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J

Neurosci Res. 99:1009–1023. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nakagawa K, Garon EB, Seto T, Nishio M,

Ponce Aix S, Paz-Ares L, Chiu CH, Park K, Novello S, Nadal E, et

al: Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated,

EGFR-mutated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (RELAY): A

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 20:1655–1669. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Salvagno C, Mandula JK, Rodriguez PC and

Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Decoding endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in

cancer cells and antitumor immunity. Trends Cancer. 8:930–943.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Qiao L, Shao X, Gao S, Ming Z, Fu X and

Wei Q: Research on endoplasmic reticulum-targeting fluorescent

probes and endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated nanoanticancer

strategies: A review. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces.

208:1120462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cao LL and Kagan JC: Targeting innate

immune pathways for cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 56:2206–2217.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang H, Li Z, Tao Y, Ou S, Ye J, Ran S,

Luo K, Guan Z, Xiang J, Yan G, et al: Characterization of

endoplasmic reticulum stress unveils ZNF703 as a promising target

for colorectal cancer immunotherapy. J Transl Med. 21:7132023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang YH, Huo BL, Li C, Ma G and Cao W:

Knockdown of long noncoding RNA SNHG7 inhibits the proliferation

and promotes apoptosis of thyroid cancer cells by downregulating

BDNF. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 23:4815–4821. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu Y, Jiang WG, Wang HC, Martin T, Zeng

YX, Zhang J and Qi YS: BDNF activates TrkB/PLCγ1 signaling pathway

to promote proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells

through inhibition of apoptosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

23:5093–5100. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|