Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is characterized by high

fatality rates, with a 5-year survival rate of ~4% (1,2).

Notably, targeted therapies have proven inadequate, due to the

substantial heterogeneity within PC (3). In recent years, immunotherapy has

offered potential for the treatment of various solid tumors,

including melanoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, renal cell

carcinoma, head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer and bladder

cancer (4,5); however, prior studies have suggested

that unselected patients with PC often exhibit minimal or no

response to immunotherapy (6–8).

Cell death mechanisms serve pivotal roles in

maintaining physiological homeostasis, eliminating damaged cells

and responding to pathological stimuli (9). Traditionally, apoptosis was considered

the primary form of programmed cell death; however, recent

advancements in tumor cell biology have identified various subtypes

of programmed cell death, such as necroptosis, pyroptosis and

ferroptosis, each associated with distinct biological contexts

(10,11). Copper ions are indispensable for

cellular physiology, including energy metabolism, mitochondrial

respiration and antioxidant activity (12,13).

Dysregulation of copper ions can disturb lipid metabolism, and one

distinctive form of cell death, known as cuproptosis, emerges due

to copper excess, resulting in oxidative stress, mitochondrial

damage and endothelial cell dysfunction (14–16).

In addition, recent research has revealed a novel mechanism of

copper-induced cell death involving the aggregation of lipoylated

dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT), a component of the

mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle, ultimately leading to

proteotoxic stress and cell death termed cuproptosis (17,18).

Mounting evidence has suggested that disrupted copper homeostasis

can impact tumor growth (19–21),

and targeted cuproptosis therapy holds promise, particularly for

highly fatal tumors with limited therapeutic options, such as PC

(22,23). In the past decade, research into

programmed cell death in tumors has indicated the immunogenicity of

the tumor microenvironment (TME), rendering it amenable to

anticancer interventions (24–26).

Notably, various TME components undergoing programmed cell death

can elicit immune responses against tumor cells, thereby enhancing

antitumor effects. For example, tumor destruction facilitates

antigen acquisition by conventional dendritic cells, promotes the

recruitment of myeloid cells and restricts T-cell cytotoxic

activity (27–29).

The latest research has suggested a novel connection

between TME composition, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and

malignant cell stemness, as well as patient survival, which may

lead to improved upfront risk stratification and more personalized

clinical decision-making (30,31).

Some studies have demonstrated the role of cuproptosis in

tumorigenesis, tumor progression and prognosis (19,32).

However, the unique molecular signature of cuproptosis and its

interplay with the TME remain unexplored in PC. Therefore,

investigating whether cuproptosis alters the TME and impacts

anticancer therapy outcomes is a key research avenue.

The present study provides a comprehensive analysis

of the difference in expression of cuproptosis-related genes (CGs)

and gene variation, focusing on their latent roles in PC

tumorigenesis, prognosis, TME and treatment outcomes using

multi-omics data. Two distinct cuproptosis-related subtypes within

PC were identified, and their molecular characteristics, prognostic

significance and interactions with the tumor immune

microenvironment were evaluated. Furthermore, a CG scoring system

was established to predict clinical outcomes and immunotherapy

responses in patients with PC. In conclusion, the present study

established a risk score as a robust prognostic indicator for

patients with PC, offering potential for precise risk

stratification, insights into TME characteristics and the

exploration of more effective immunotherapy strategies.

Materials and methods

PC data sources and preprocessing

The present study used multi-omics data from cohorts

of patients with PC extracted from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA),

Genome Tissue Expression (GTEx), International Cancer Genome

Consortium (ICGC), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the Human Protein

Atlas (HPA) and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium

(CPTAC) databases. The normalized mRNA expression data and

corresponding clinical information from 160 patients with

pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), including survival status, grade,

sex and age, were obtained from TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Furthermore, another

independent cohort was retrieved from the ICGC database (https://dcc.icgc.org/, which contained 101 PAAD cases.

Samples from patients with a deficiency of clinical information

were excluded from subsequent analysis. In addition, transcriptome

data from 167 normal pancreatic tissues were downloaded from the

public database GTEx project (https://www.gtexportal.org;

gtex_RSEM_gene_fpkm).

Cell-free DNA data from liquid biopsies were

obtained from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database. Two GEO

datasets containing 47 blood plasma samples of PC were included in

the analysis, namely GSE136651 [normal=22 vs. tumor=10] (33) and GSE81314 (34) (normal=8 vs. tumor=7).

The protein level verification of CGs in PC tissues

was investigated using immunohistochemistry from the HPA

(https://www.proteinatlas.org/) database

(35). The PC proteome and

corresponding clinical data were sourced from the CPTAC database

(https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu/cptacPublic),

which included 90 normal and 145 tumor samples. Relative protein

abundance was log2 transformed and zero centered for

each gene to obtain final relative abundance values.

Establishment of cuproptosis

subtypes

A total of 10 CGs [ferredoxin 1 (FDX1), DLAT, metal

regulatory transcription factor 1 (MTF1), CDK inhibitor 2A

(CDKN2A), glutaminase (GLS), dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD),

pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit α1 (PDHA1), lipoic acid

synthetase (LIAS), lipoyltransferase 1 (LIPT1) and pyruvate

dehydrogenase E1 subunit β (PDHB)] were identified based on the

related genes that regulate cuproptosis mentioned in a previous

article (15). Consensus clustering

was applied to identify distinct cuproptosis-associated patterns

using the k-means algorithm in the ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ package

(36,37). A total of 1,000 iterations were

applied to guarantee the stability of the classification. To

explore the biological behaviors of CGs in PC, gene set variation

analysis was performed on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes gene set (c2.cp.kegg.v7.5) from the Molecular Signatures

Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/) (38).

Analysis of immune infiltration

The TME scores (including immune and stromal scores)

of TCGA-PAAD tissues were estimated using several acknowledged

methods, including XCELL (https://comphealth.ucsf.edu/app/xcell), TIMER

(http://timer.cistrome.org/), QUANTISEQR

(https://bioconductor.org/packages/quantiseqr/),

MCPOUNTER (https://github.com/cit-bioinfo/mMCP-counter), EPIC

(https://github.com/GfellerLab/EPIC),

CIBERSORT-ABS and CIBERSORT (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) (39). ImmuneScore (indicating the level of

immune cell infiltration), StromalScore (indicating the level of

stromal cell infiltration) and ESTIMATEScore (reflecting the sum of

both) for each patient were measured using the R package ‘ESTIMATE’

(https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/public-software/estimate/)).

In addition, the infiltrating proportions of immune cells were

assessed with the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

(ssGSEA) algorithm (https://cloud.genepattern.org) (40).

Development of the

cuproptosis-associated prognostic score

The ‘limma’ package (https://www.plob.org/tag/limma/) (41) was used to screen the differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) in the distinct CG subtypes with criteria of

|log2-fold change| ≥1 and P<0.05. Next,

prognosis-associated genes were acquired by a univariate Cox

regression analysis based on DEGs. Subsequently, the least absolute

shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) penalties were used to

identify the most robust prognostic biomarkers. Finally, candidate

biomarkers and their correlation coefficients were acquired to

establish a CG gene signature, defined as the risk score. The risk

score was calculated as follows: Risk score=Σ (expression ×

corresponding coefficient).

PC cell line culture

Human PC cell lines (PATU-8988T, AsPC-1 and BxPC-3)

and one normal pancreatic duct cell line (hTERT-HPNE were obtained

from the China Infrastructure of Cell Line Resources, Institute of

Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The

PATU-8988T, AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640

medium (HyClone; Cytiva), and hTERT-HPNE cells were cultured in

DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin (Corning, Inc.) and 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Cellular total RNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A

total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc.) and cDNA was synthesized by

RT with a PrimerScript RT reagent Kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed to examine the

mRNA expression levels of the FDX1, DLAT, MTF1 and CDKN2A using the

SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) with the Roche

LightCycler480 PCR instrument (Roche Diagnostics). The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: cDNA pre-denaturation,

95°C for 30 sec; cDNA denaturation, 95°C for 10 sec; and primer

annealing and new strand extension, 60°C for 30 sec. The

denaturation, annealing and extension steps were repeated for a

total of 40 cycles. All primers used in the present study are

listed in Table I. β-actin was used

as an internal control and the relative mRNA levels were calculated

based on the 2−ΔΔCq method (42).

| Table I.Primers utilized in our

investigation. |

Table I.

Primers utilized in our

investigation.

| Gene symbol | Primer sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| PDX1 | F:

GGAGCAGGATTGTGCCGTAA |

|

| R:

CTGTGGGGACGCACTAAGG |

| DLAT | F:

GAGATGTCCCTCTAGGAACCC |

|

| R:

ACAAACACCCTTCCCTTTGGT |

| MTF1 | F:

CACAGTCCAGACAACAACATCA |

|

| R:

GCACCAGTCCGTTTTTATCCAC |

| CDKN2A | F:

GGGTTTTCGTGGTTCACATCC |

|

| R:

CTAGACGCTGGCTCCTCAGTA |

| β-actin | F:

CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC |

|

| R:

CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT |

Genomic mutation analysis and drug

response prediction

To identify the differences in somatic mutations

between high- and low-risk groups of patients with PC, the mutation

annotation format in TCGA cohort was created with the ‘maftools’ R

package (43). To further screen

therapeutic responses to chemotherapeutics in the two groups of

patients, the ‘pRRophetic’ package was used to evaluate the

half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of

chemotherapeutic drugs commonly applied to treat tumors, based on

drug sensitivity data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in

Cancer (GDSC) dataset (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/) (44).

Additional bioinformatics and

statistical analyses

The R software (version 4.4.0; R Development Core

Team; http://www.r-project.org/) and its

corresponding packages were applied to process, analyze and present

the data. The principal component analysis (PCA) (45) was performed to assess patterns of

CGs associated with cuproptosis subtypes. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Two-tailed unpaired

Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was applied to analyze the

differences between two groups. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc

test was used for differential analysis among three or more groups.

Correlation was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation

coefficient. The genomic location of copy number variant (CNV)

alterations in the 10 CGs across chromosomes was analyzed using the

‘circlize’ R package (https://github.com/jokergoo/circlize). The difference

in overall survival (OS) between the two groups was estimated using

the Kaplan-Meier survival curve with the R package

‘survminer’(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html)

using log-rank test. Additionally, Cox regression for survival

analysis was conducted using the ‘survival’ package (https://github.com/therneau/survival).

The time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

was plotted using the R package ‘timeROC’ (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/timeROC/). All

heatmaps were generated using ‘pheatmap’ package. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

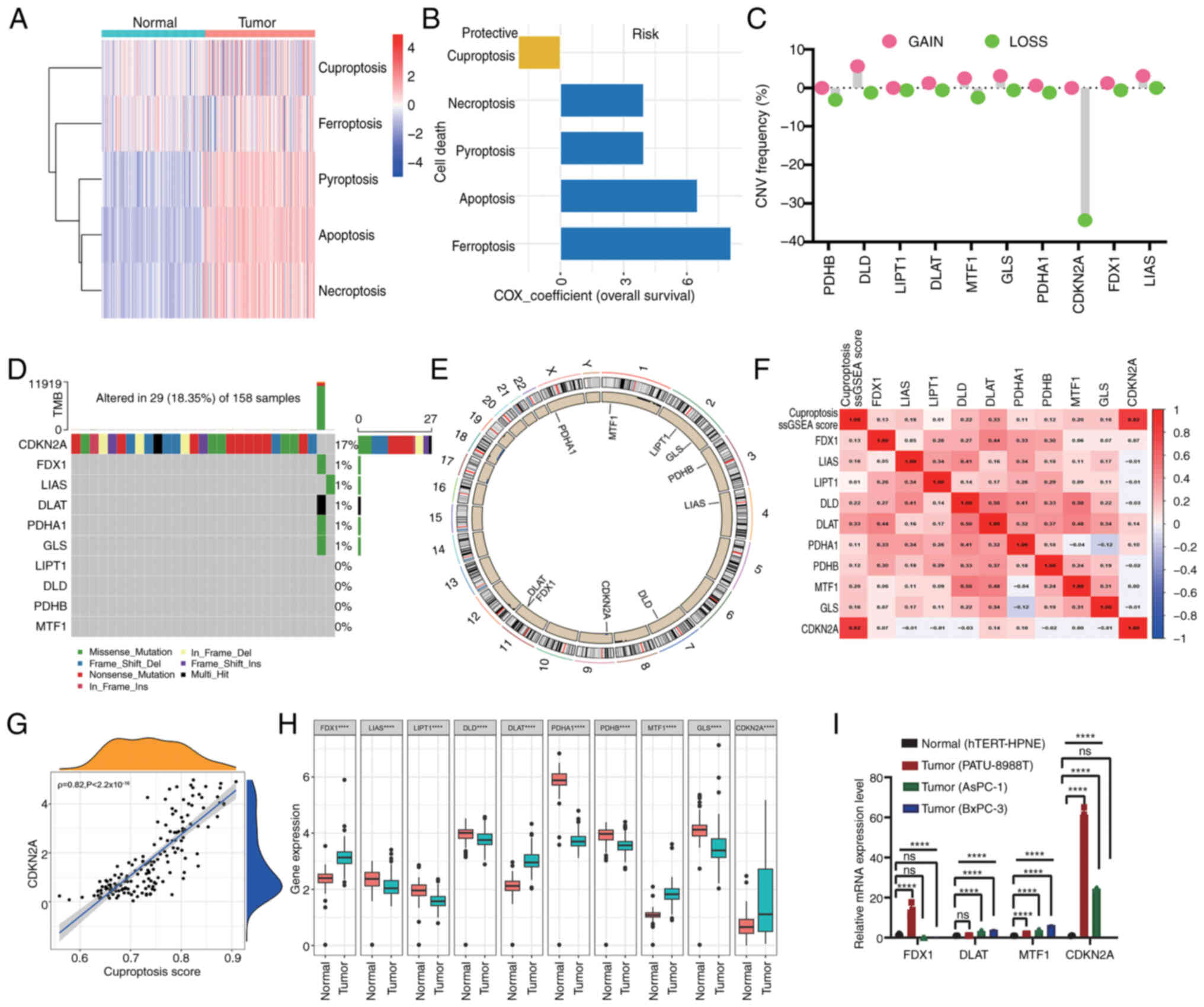

Cuproptosis ssGSEA score is associated

with improved OS in patients with PC

The flow chart of the present study is shown in

Fig. S1. Regarding the

intertumoral heterogeneity of cell death in patients with PC, the

enrichment scores of five reported cell death modes were estimated

using ssGSEA in pancreatic tumor and healthy pancreatic tissue

samples from TCGA-PAAD and GTEx cohorts. The results revealed that

apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis were aberrantly

hyperactivated in tumor tissues, whereas there were no significant

differences in terms of cuproptosis (Fig. 1A). Utilizing ssGSEA scores for each

cell death pathway and survival data, Cox coefficient analysis was

conducted for these pathways in patients with PC. Notably, among

all cell death pathways, cuproptosis was the only one associated

with a longer OS (Fig. 1B). These

findings suggested that cuproptosis may have a key role as a

positive predictive factor of improved OS in patients with PC.

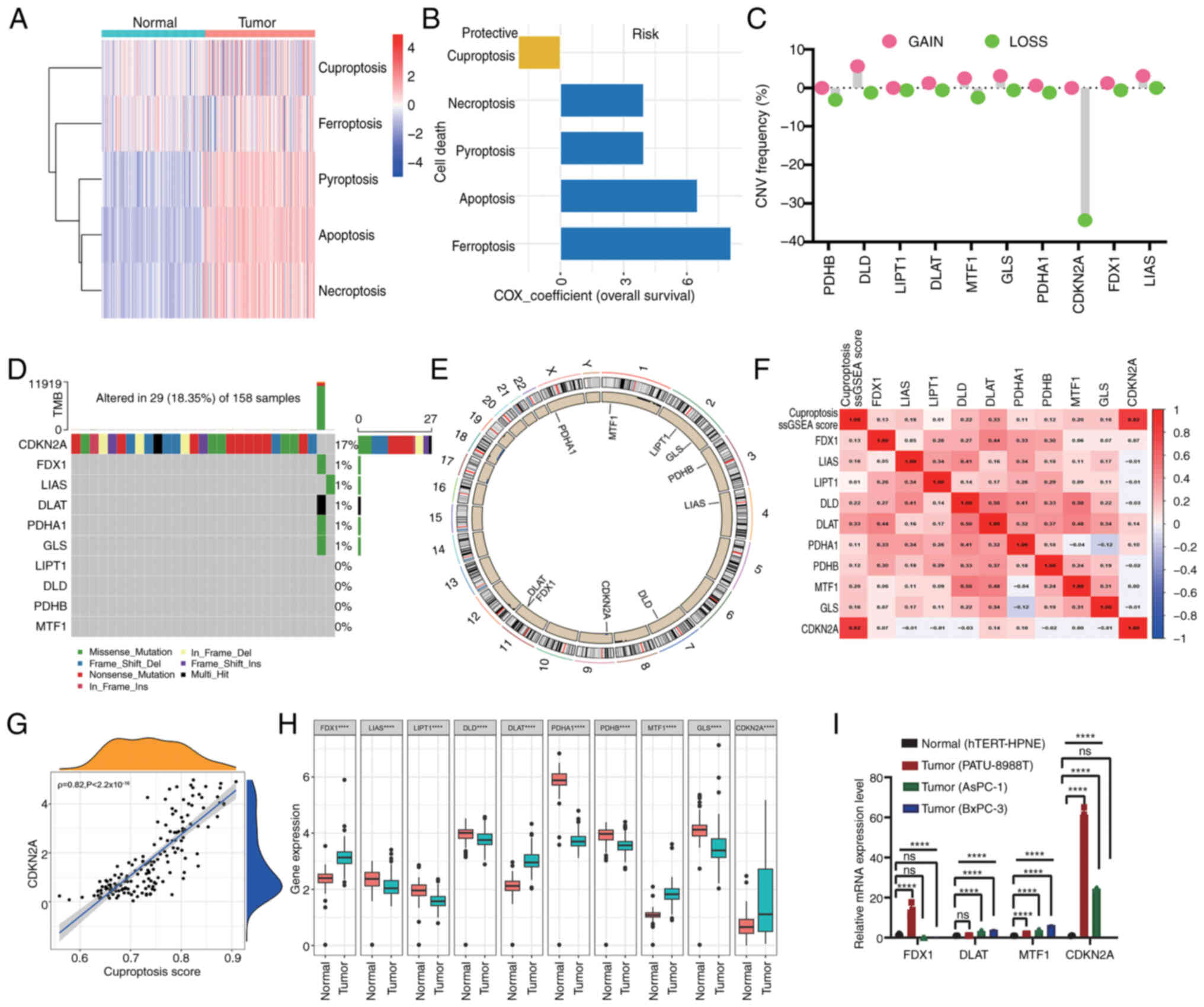

| Figure 1.Genetic mutation landscape of CGs and

cuproptosis subtypes in PC tumorigenesis. (A) Heatmap indicating

the enrichment scores of five reported cell death pathways in

pancreatic tumors and normal pancreatic samples. (B) Distribution

of Cox coefficients of cell death pathways determined by univariate

Cox regression analysis. (C) Frequencies of CNV gain and loss among

CGs. (D) Mutation frequencies of CGs in 158 patients with PC from

TCGA cohort. (E) Circular plots of chromosome distributions of CGs.

(F) Heatmap displaying the correlation between cuproptosis score

and mRNA expression of CGs. Red represents a positive correlation,

whereas blue represents a negative correlation. (G) Correlations

between the cuproptosis score and the expression of CDKN2A. (H)

Expression of CGs in pancreatic tumor and healthy pancreatic

samples (****P<0.0001, determined by Mann-Whitney U test). (I)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analyses of the mRNA

expression levels of FDX1, DLAT, MTF1 and CDKN2A in PC cell lines

(PATU-8988T, AsPC-1 and BxPC-3) and normal pancreatic cells

(hTERT-HPNE). The results were presented as means ± SD from three

times of independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post

hoc test was performed to analyze data. ****P<0.001. CG,

cuproptosis-related gene; CNV, copy number variant; PC, pancreatic

cancer; FDX1, ferredoxin 1; DLAT, dihydrolipoamide

S-acetyltransferase; MTF1, metal regulatory transcription factor 1;

CDKN2A, CDK inhibitor 2A; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

Genomic mutation landscape of CGs in

PC

To comprehensively elucidate the genetic landscape

of CGs involved in tumorigenesis, an analysis was conducted

encompassing the total somatic mutation frequency and CNVs of CGs

in a cohort of 160 patients with PC sourced from TCGA dataset.

Complete information of these patients is listed in Table SI. Notably, DLD, DLAT and GLS

exhibited CNV amplifications, whereas PDHB and CDKN2A displayed CNV

reductions (Fig. 1C). As depicted

in Fig. 1D, the frequency of CDKN2A

mutations was the highest, with 17% of patients harboring CDKN2A

mutations, Missense and nonsense mutations were the main types of

CDKN2A mutations. Fig. 1E indicates

the genomic location of CNV alterations in the 10 CGs across

chromosomes. The mRNA expression levels of genes are regulated by

gene variants and the present findings underscored notable

disparities in the genetic landscape of CGs between PC and normal

samples, providing information on the potential involvement of CGs

in PC tumorigenesis.

Expression and prognostic relevance of

CGs in PC

Further analysis revealed that the cuproptosis score

was significantly positively correlated with the expression levels

of CDKN2A, followed by DLAT, suggesting that CDKN2A is the core

gene involved in PC cuproptosis status; by contrast, there was no

significant correlation between cuproptosis score and FDX1, MTF1,

GLS, DLD, PDHA1, LIAS, LIPT1 and PDHB (Fig. 1F and G). Next, an analysis was

conducted to evaluate the mRNA expression levels of CGs in PC.

Compared with normal pancreatic cancer tissue from the GTEx cohort,

FDX1, DLAT, metal regulatory transcription factor 1 (MTF1) and

CDKN2A were significantly highly expressed in PC from TCGA cohort;

whereas GLS, DLD, PDHA1, LIAS, LIPT1 and PDHB were downregulated in

PC (Fig. 1H). Subsequently, four

genes (FDX1, DLAT, MTF1 and CDKN2A) were selected, which were

highly expressed in tumor tissues, for validation in PC cell lines

using RT-qPCR analysis. The results indicated that the mRNA

expression levels of DLAT, MTF1 and CDKN2A exhibited substantial

elevation in PC cells (PATU-8988T, AsPC-1 and BxPC-3) compared with

those in the normal pancreas cell line (hTERT-HPNE). However, the

expression levels of FDX1 was inconsistent among different PC cell

lines; it was upregulated in PATU-8988T cells but downregulated in

AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cells compared with that in normal pancreas cells

(Fig. 1I), which may be potentially

attributable to the inherent heterogeneity among cell lines.

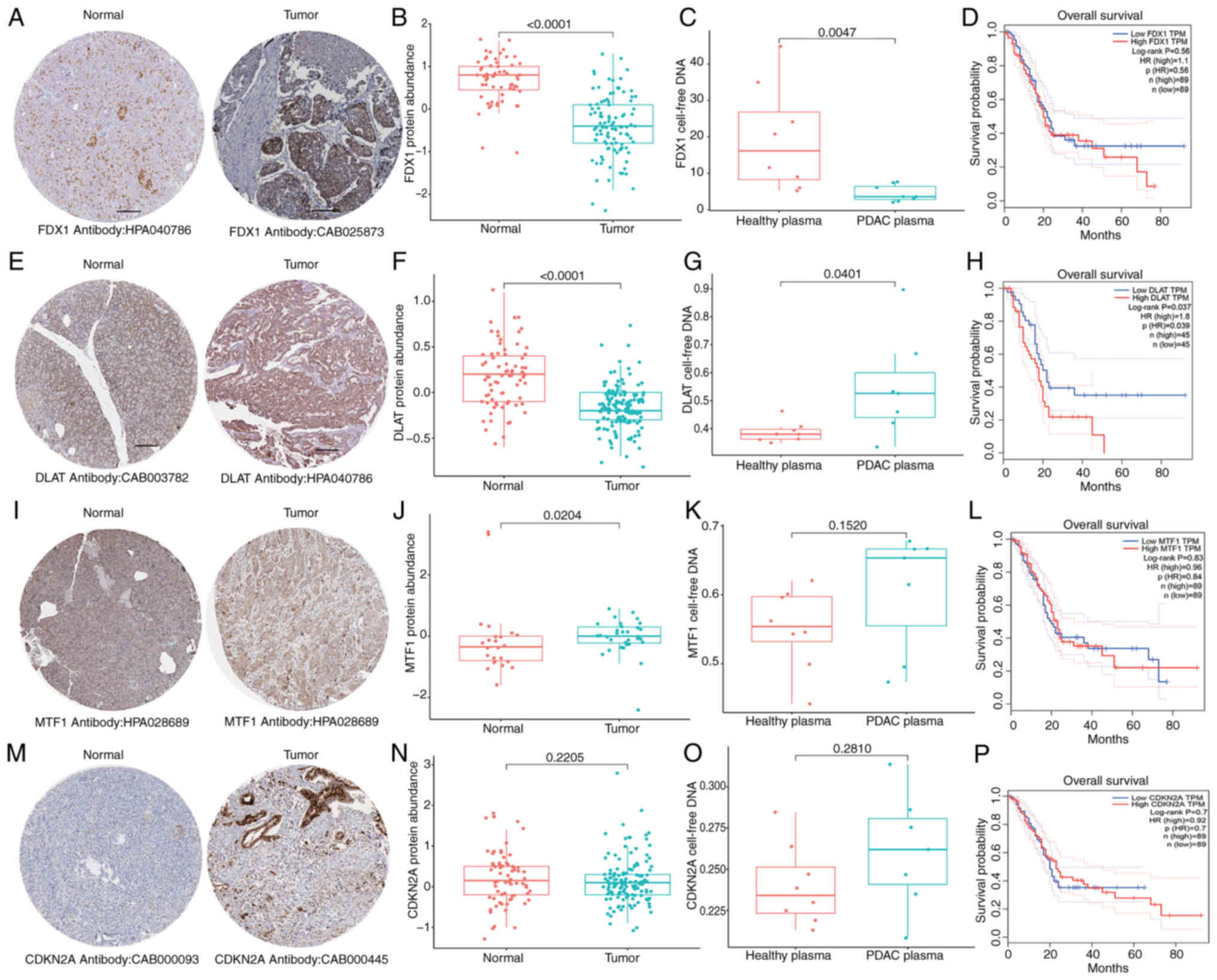

To evaluate the potential of FDX1, DLAT, MTF1 and

CDKN2A as non-invasive biomarkers of risk assessment, their levels

in cell-free DNA derived from blood plasma samples of patients with

PC and healthy donors were analyzed. The results revealed that

compared with in samples from healthy donors, the blood plasma DNA

levels of DLAT was significantly increased in samples from patients

with PC, whereas FDX1 was significantly decreased (Fig. 2C, G, K and O). Notably, there was no

significant difference in MTF1 and CDKN2A between samples from

patients with PC and healthy donors (Fig. 2K and O). Further survival analysis

demonstrated that the expression of DLAT was positively associated

with worse prognosis (Fig. 2H),

whereas the expression of FDX1, MTF1 and CDKN2A was not related to

the survival of pancreatic cancer (Fig.

2D, L and P).

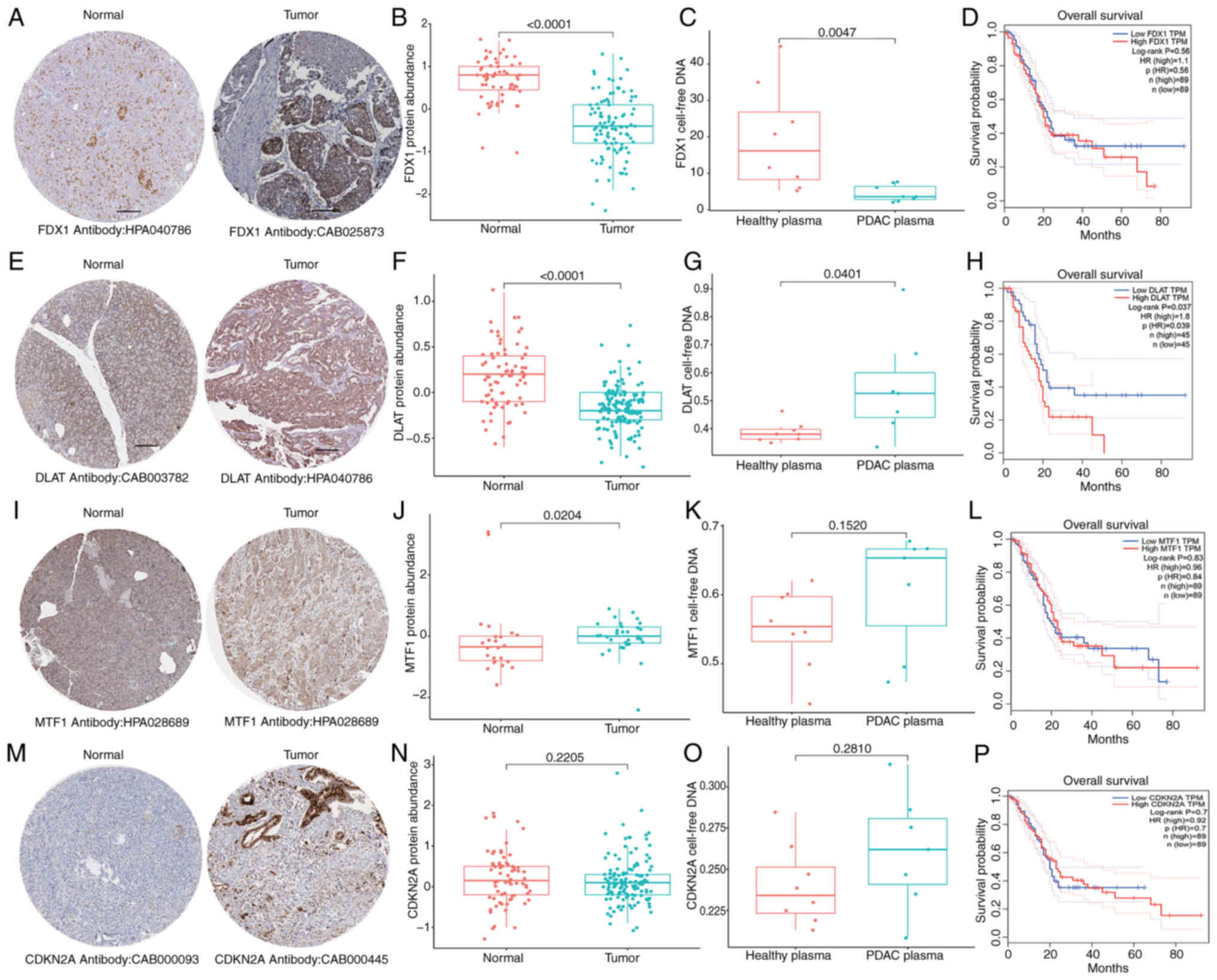

| Figure 2.Expression and prognosis of

cuproptosis-related genes in PC. Histological expression levels of

(A) FDX1, (E) DLAT, (I) MTF1 and (M) CDKN2A from the Human Protein

Atlas database; the antibody type used in immunohistochemistry and

the patient ID of tissue specimens are shown at the bottom of each

image. Different protein levels of (B) FDX1, (F) DLAT, (J) MTF1 and

(N) CDKN2A in pancreatic tumor and healthy pancreas samples from

the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium database (the

Mann-Whitney U test was performed to analyze data). Different

cell-free DNA levels of (C) FDX1, (G) DLAT, (K) MTF1 and (O) CDKN2A

in blood plasma samples of normal healthy donors and pancreatic

cancer from the GEO database (the Mann-Whitney U test was performed

to analyze data). (D, H, L and P) Survival analysis of (D) FDX1,

(H) DLA, (L) MTF1 and (P) CDKN2A in The Cancer Genome

Atlas-pancreatic adenocarcinoma cohort. FDX1, ferredoxin 1; DLAT,

dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase; MTF1, metal regulatory

transcription factor 1; CDKN2A, CDK inhibitor 2A; PC, pancreatic

cancer. |

Verification of protein levels of CGs was also

conducted using PC proteomics analysis. The results indicated that

the protein levels of FDX1 and DLAT were significantly reduced in

PC tumors compared with those in normal pancreatic tissues from the

GTEx project (Fig. 2A, B, E and F),

while MTF1 exhibited a significant increase in PC tumors (Fig. 2I and J). No significant differences

in expression were observed for CDKN2A (Fig. 2M and N). Notably, while FDX1 was

shown to be increased in tumor tissues (Fig. 1H), it was decreased in in plasma

samples (Fig. 2C). Although the

inconsistency between the protein and transcription levels of CGs

may be due to tumor heterogeneity, the present results indicated

that dysregulated CG expression is involved in PC

tumorigenesis.

Immunological characteristics and

pathway scores of cuproptosis subtypes

Based on ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’, the optimal number

of clusters was determined to be k=2, indicating that a division

into CG cluster A (n=70) and CG cluster B (n=90) was the optimal

choice for the cohort (Fig. 3A).

The results of PCA also confirmed the notable intergroup

distribution (Fig. 3B).

Furthermore, a CGs network was constructed (Fig. 3C) to provide insights into the

comprehensive genetic patterns, regulatory connections and clinical

significance of CGs in patients with PC. Patients within CG cluster

B exhibited worse OS compared with those in CG cluster A within

TCGA cohort (log-rank test; P=0.032; Fig. 3D). The validation of clustering

repeatability using the ICGC cohort is presented in Fig. S2.

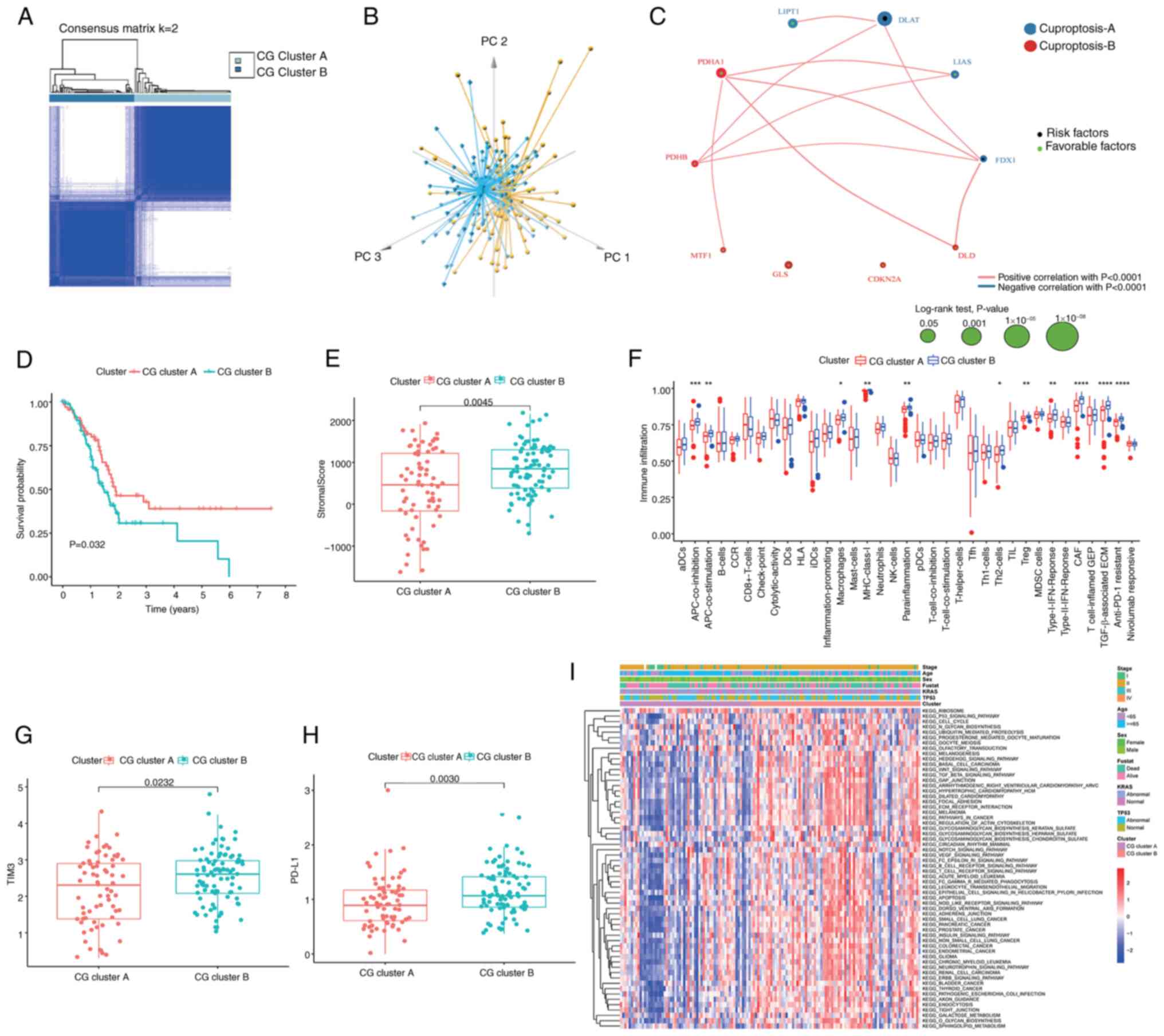

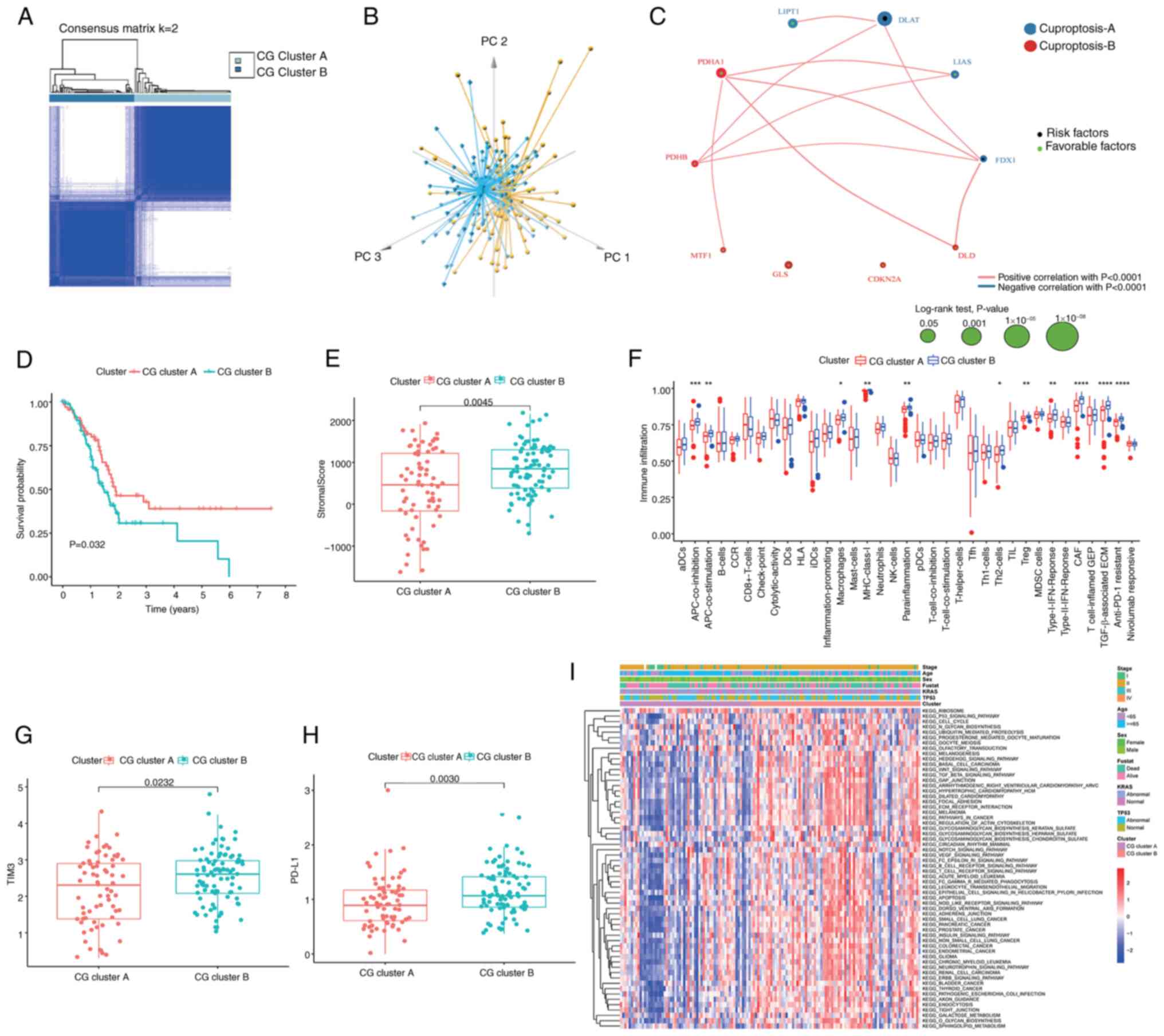

| Figure 3.Immunological characteristics and

pathway scores of cuproptosis subtypes. (A) Consensus matrix

heatmap defining two clusters (k=2) and their correlation area. (B)

Principal component analysis demonstrating two distinct subtypes of

cuproptosis in TCGA cohort. (C) A network of correlations including

CGs in TCGA-pancreatic adenocarcinoma cohort. (D) Kaplan-Meier plot

of overall survival of patients with PC split according to CG

clusters, analyzed by log-rank test. (E) Association between the

two cuproptosis subtypes and stromal score in PC. (F) Abundance of

the infiltration of 35 tumor microenvironment cells of patients

with PC split according to two cuproptosis subtypes. Expression

levels of (G) TIM3 and (H) PD-L1 in the patients with PC split

according to two cuproptosis subtypes. (I) Gene Set Variation

Analysis of the biological pathways of two cuproptosis subtypes in

PC samples from TCGA and International Cancer Genome Consortium

cohorts. ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05,

not significant (P>0.05), analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U

test. CG, cuproptosis-related gene; PC, pancreatic cancer; TCGA,

The Cancer Genome Atlas; TIM3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin

domain-containing protein 3; PD-L1, programmed cell death

ligand-1. |

The TME serves a key role in the progression of PC

and has been notably associated with the limited efficacy of

conventional therapeutic modalities, including chemotherapy,

radiotherapy and immunotherapy (46). To comprehensively assess the TME

within distinct CG subtypes, the present study quantified the

immune and stromal components using the ‘ESTIMATE’ algorithm.

Compared with CG cluster A, CG cluster B was characterized by

elevated stromal score (Fig. 3E).

Further analysis revealed enhanced enrichment of various immune

signatures in CG cluster B, including those associated with

antigen-presenting cell (APC) co-inhibition, APC co-stimulation,

inflammation-promoting processes, mast cells, parainflammation, T

helper 2 cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), CAFs, TGF-β-associated

extracellular matrix (ECM) and resistance to anti-programmed cell

death protein (PD)-1 immunotherapy (Fig. 3F). Similarly, it was observed that

the expression levels of the key immune checkpoint molecules

programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) and T-cell immunoglobulin

and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM3) were higher within CG

cluster B (Fig. 3G and H).

Collectively, these findings suggested that CG cluster B may be a

hallmark of stromal activation coupled with immunosuppression in

PC, which offers potential options for therapeutic intervention,

particularly employing PD-L1 and TIM3 inhibitors.

The results of GSEA demonstrated that CG cluster B

exhibited notable enrichment in KEGG tumor-related pathways,

encompassing the ‘TGF-beta signaling pathway’ and ‘Wnt signaling

pathway’, as well as ‘ECM receptor interaction’, alongside

immune-related pathways, notably ‘T-cell receptor signaling

pathway’ and ‘B-cell receptor signaling pathway’ (Fig. 3I; Table

SII), suggesting that alterations in these pathways affect the

infiltration of immune cells in different cuproptosis subtypes.

Construction of the

cuproptosis-related signature in different cohorts

In the two subclusters, a total of 224 DEGs

associated with CG subtypes were identified (Table SIII). Subsequently, these DEGs were

subjected to a univariate Cox regression analysis, identifying 161

prognostically significant genes (P<0.05; Table SIV). To identify the most robust

candidates, LASSO and multivariate Cox analyses were employed, as

illustrated in Fig. 4A, along with

a distribution of LASSO coefficients for the gene signature shown

in Fig. 4B. Consequently, a set of

five central candidates were derived, comprising three

risk-associated genes [uroplakin-2 (UPK2), lactate dehydrogenase A

pseudogene 7 (LDHAP7) and family member with sequence similarity 83

(FAM83A)] and two protective genes [microRNA-3677 (MIR3677) and

AC068620.2], to generate a cuproptosis-related signature with the

following algorithm: Risk score=(−0.426 × expression of MIR3677) +

(−0.827 × expression of AC068620.2) + (0.312 × expression of UPK2)

+ (0.306 × expression of LDHAP7) + (0.336 × expression of FAM83A).

Patients were divided into high- and low-risk score groups based on

the median risk score value.

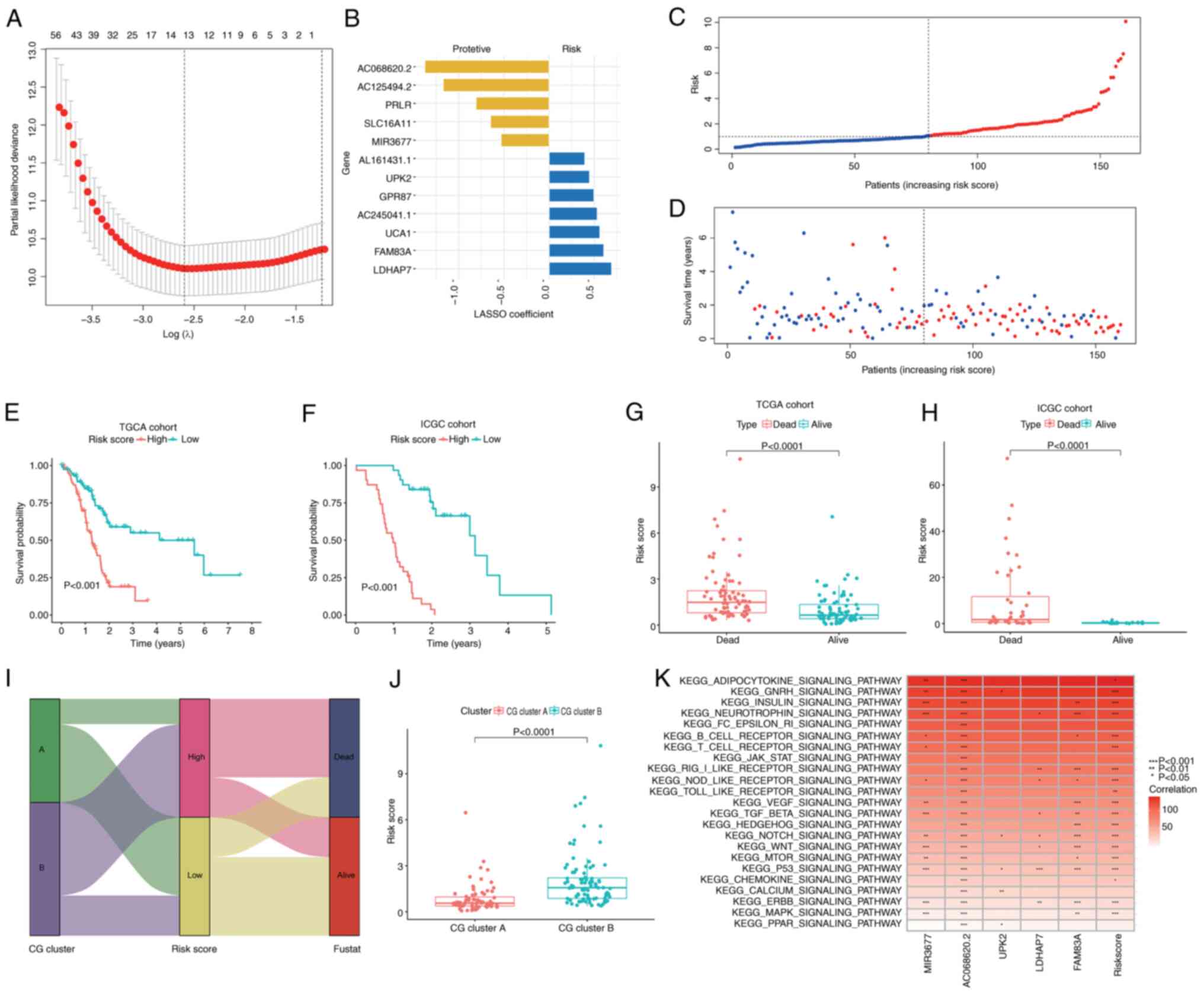

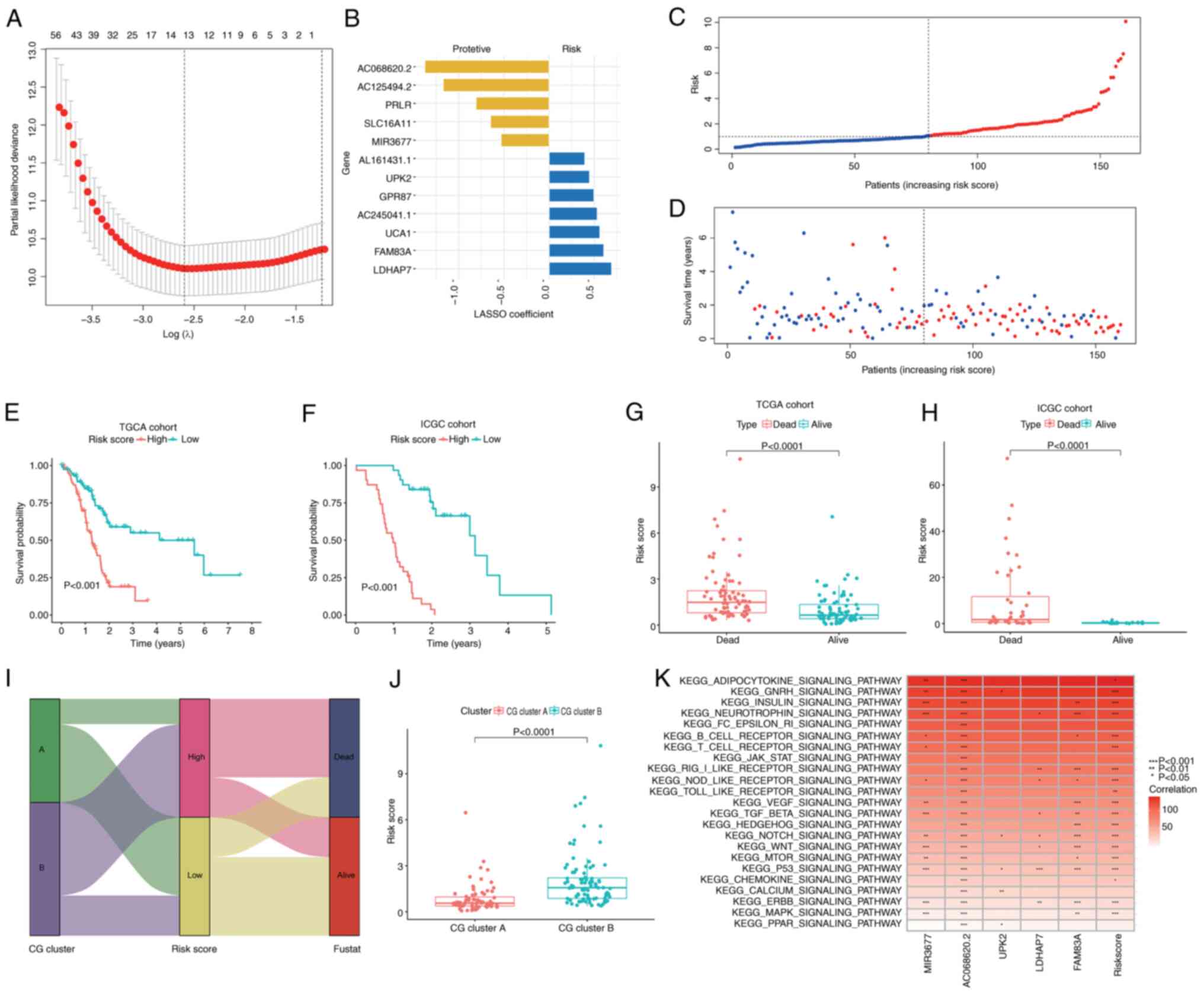

| Figure 4.Construction and validation of the

cuproptosis-related signature in different cohorts. (A) LASSO Cox

regression model was applied to identify the most robust

biomarkers. (B) Distribution of LASSO coefficients of the CG

signature. (C) Ranked dot plot demonstrating the risk score

distribution and patient survival status. (D) Scatter plot

demonstrating the patient survival status. (E and F) Kaplan-Meier

curves were used to analyze the survival of patients with PC with

high- and low-risk scores in TCGA and ICGC cohorts. (G and H)

Differences in risk score between dead and alive patients with PC.

(I) Alluvial diagram of cuproptosis subtype distributions in groups

with different risk scores, molecular subtypes and survival

outcomes. (J) Differences in risk score between CG clusters and

gene subtypes (data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test).

(K) Association analysis between tumorigenesis-associated pathways

and the selected genes. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator; CG, cuproptosis-related gene; PC, pancreatic

cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; ICGC, International Cancer

Genome Consortium; PC, pancreatic cancer; MIR3677, microRNA-3677;

UPK2, uroplakin-2; LDHAP7, lactate dehydrogenase A pseudogene 7;

FAM83A, family member with sequence similarity 83. |

The risk score profile, as depicted in Fig. 4C and D, demonstrated a direct

association between an elevated risk score, decreased OS and

heightened mortality. A heatmap indicating the selected candidates

is provided in Fig. S3.

Kaplan-Meier analyses robustly affirmed that a high-risk score was

predictive of significantly lower OS compared with a low-risk score

in TCGA cohort (P<0.001; Fig.

4E) and the ICGC cohort (P<0.001; Fig. 4F). Notably, the risk score was

significantly higher in deceased patients compared with those

patients who were alive at the time of follow-up in both TCGA and

ICGC cohorts (Fig. 4G and H).

Fig. 4I displayed the distribution

of patients in the two CG clusters and two risk score groups.

Furthermore, Fig. 4J illustrated

the patient distribution across the two CG clusters and two risk

score groups. Notably, patients within CG cluster A displayed a

lower risk score, whereas those in CG cluster B exhibited a higher

risk score. The present study then explored the correlation between

MIR3677, AC068620.2, UPK2, LDHAP7 and FAM83A in the prognostic gene

signature and the enrichment of tumorigenesis-associated pathways;

it was concluded that the majority of tumorigenesis-associated

pathways, such as the ‘TGF-β signaling pathway’, ‘Wnt signaling

pathway’ and ‘TP53 signaling pathway’, were closely associated with

the expression of MIR3677, AC068620.2, LDHAP7 and FAM83A) (Fig. 4K).

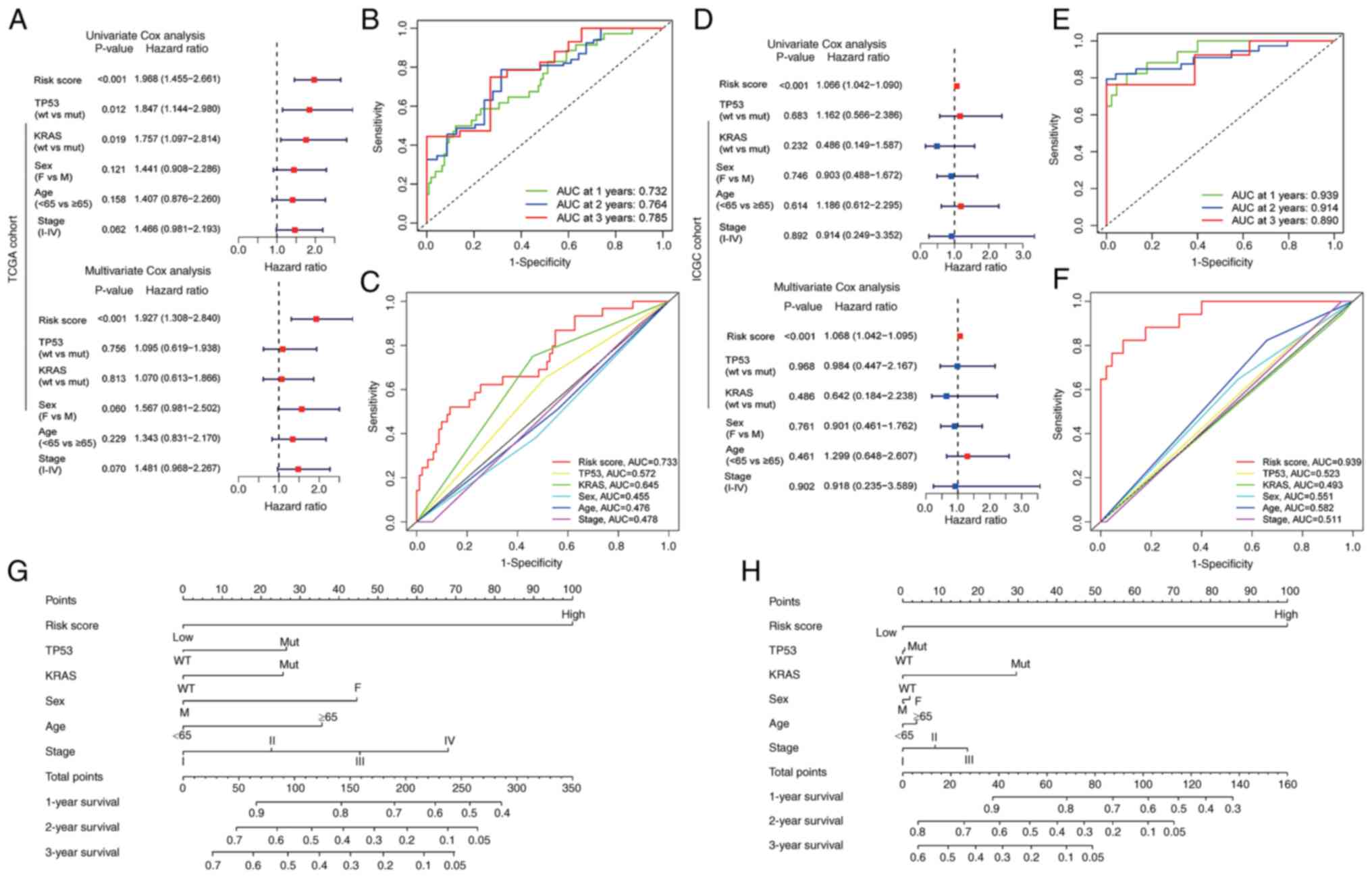

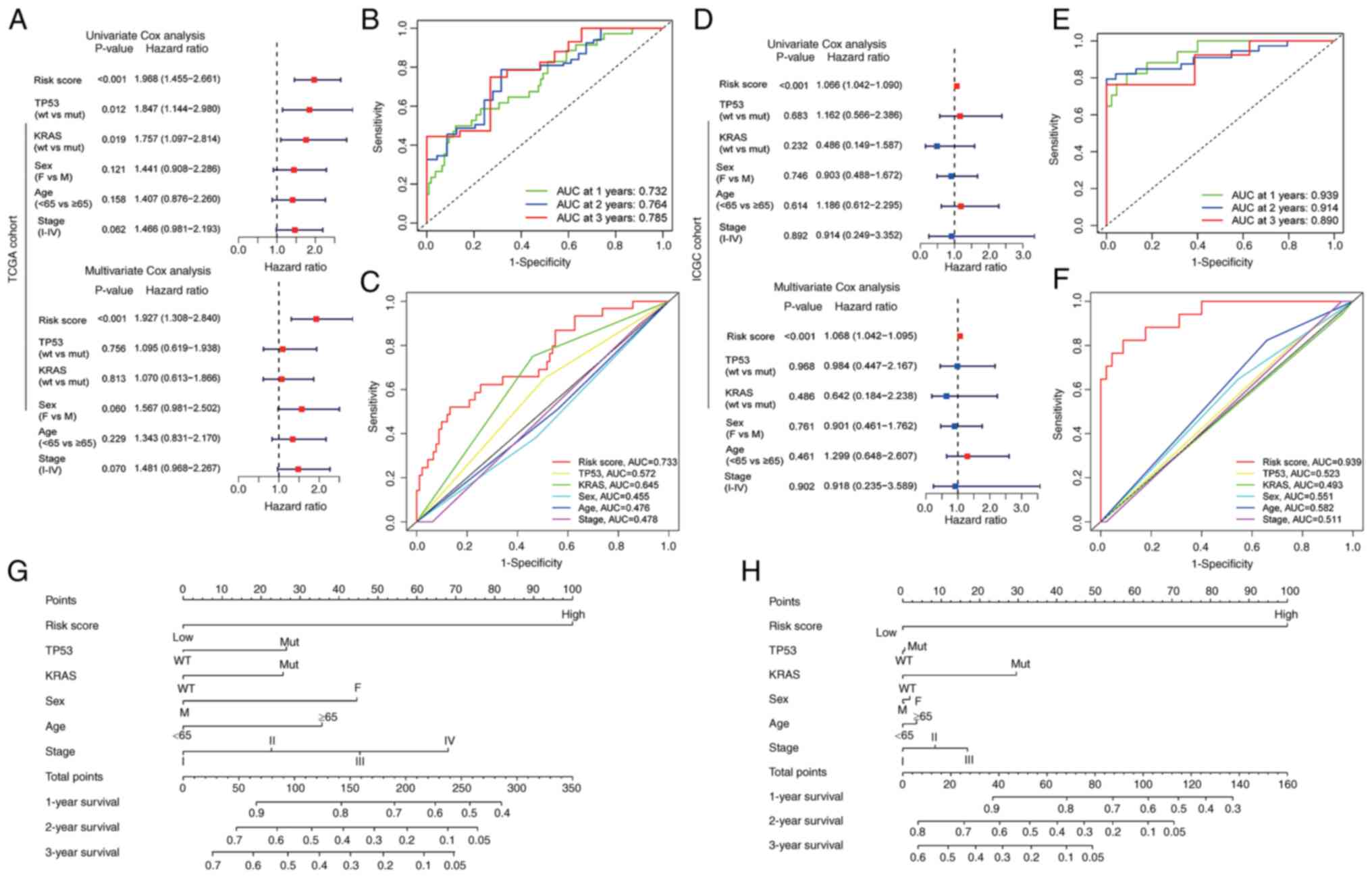

Prognostic potential of the

cuproptosis-related signature in different cohorts

Subsequently, nomograms were developed to predict

patient outcomes across different datasets, due to the notable

association between risk score and prognosis. The results

demonstrated that risk score functioned as an independent

prognostic factor for OS, even when accounting for clinical

variables, in patients with PC from both TCGA and ICGC cohorts

(Fig. 5A and D). Furthermore, the

predictive accuracy of the risk score for 1-, 2- and 3-year

survival rates was quantified by calculating the area under the

curve (AUC) in TCGA cohort (0.732, 0.764 and 0.785, respectively)

and the ICGC cohort (0.939, 0.914 and 0.890, respectively)

(Fig. 5B and E). To assess the

predictive precision of risk score compared with clinical variables

for patients with PC, the AUC values for these factors were

calculated (Fig. 5C and F).

Notably, risk score consistently exhibited robust AUC values

comparable with other clinical variables, underscoring its

performance in prognostic assessment for patients with PC.

Furthermore, nomograms were constructed incorporating risk score

and various clinical features tailored to individual patients with

PC (Fig. 5G and H). The results

demonstrated that risk score had notable predictive

performance.

| Figure 5.Prognostic potential of the

cuproptosis-related signature in different cohorts. (A and D)

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated

that risk score was an independent risk factor for OS in the (A)

training cohort and (D) validation cohort. (B) ROC curve to predict

the sensitivity and specificity of 1-, 2- and 3-year survival

according to the risk score in TCGA cohort. (E) ROC curve to

predict the sensitivity and specificity of 1-, 2- and 3-year

survival according to the risk score in ICGC cohort. (C)

Time-dependent ROC curve depicting the predictive precision of risk

score and clinical features in TCGA cohort. (F) Time-dependent ROC

curve depicting the predictive precision of risk score and clinical

features in ICGC cohort. (G) Nomogram to predict the 1-, 2- and

3-year OS of patients with pancreatic cancer in TCGA cohort. (H)

Nomogram to predict the 1-, 2- and 3-year OS of patients with

pancreatic cancer in ICGC cohort. ICGC, International Cancer Genome

Consortium; OS, overall survival; ROC, receiver operating

characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; AUC, area under the

curve; wt, wild-type; mut, mutant; M, male; F, female. |

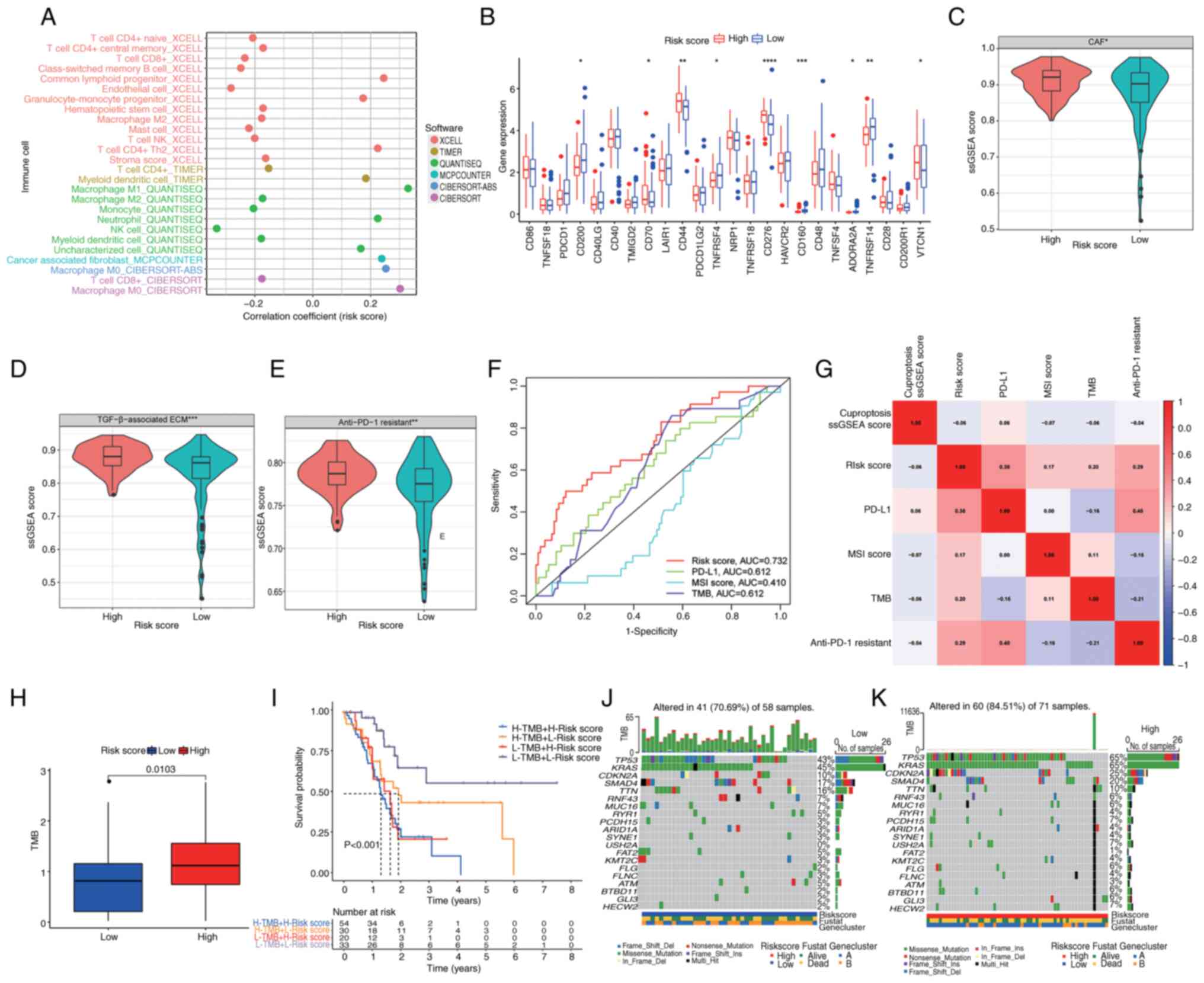

Association of immune status and

immunotherapy with the cuproptosis-related signature in PC

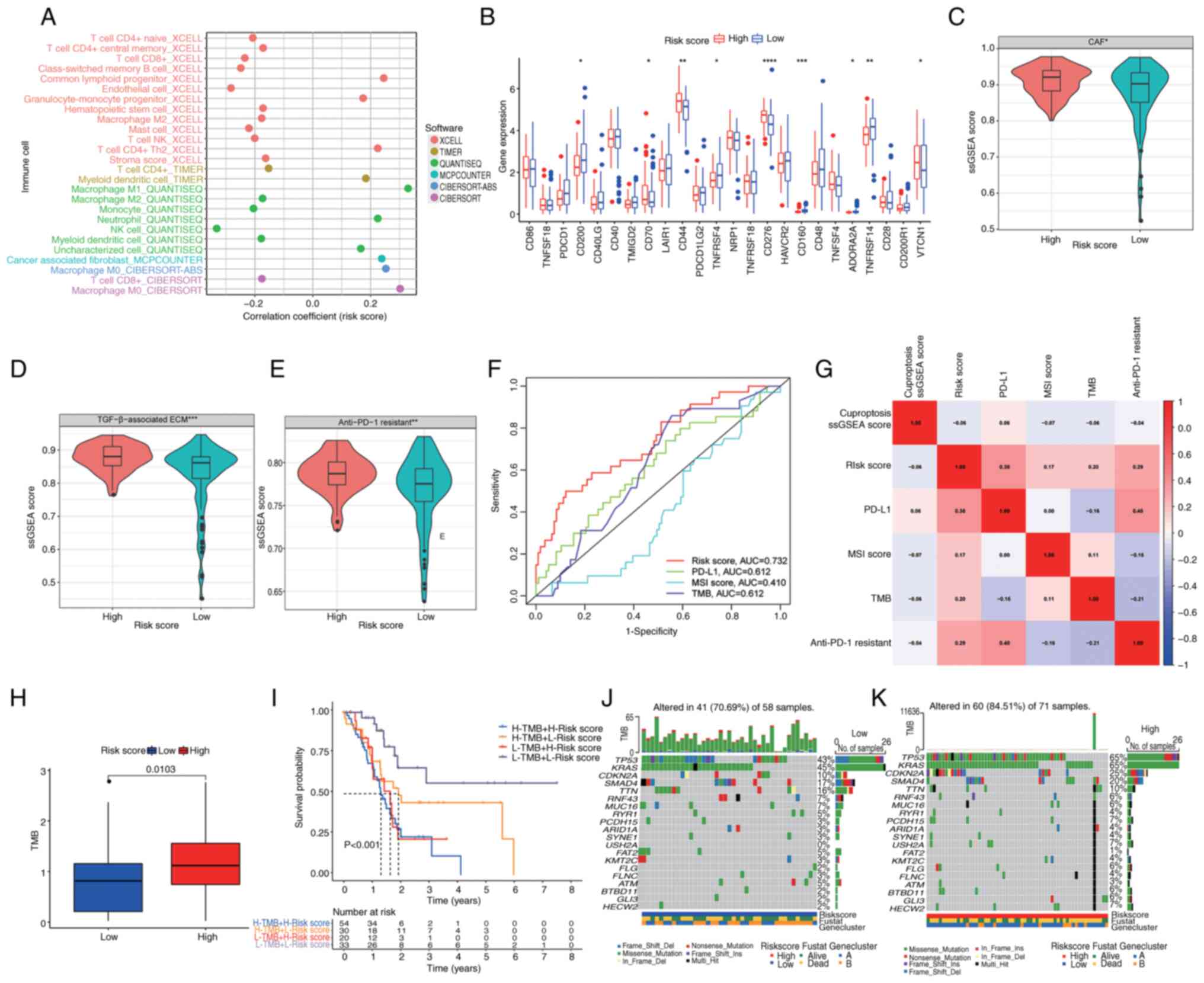

The present findings suggested a substantial

association between CG subtypes and stromal accumulation in PC.

Consequently, a comprehensive analysis of the immune interactions

within both high- and low-risk score groups was conducted. A

high-risk score exhibited an inverse relationship with key immune

cell populations, including CD8 and CD4 T cells, B cells, monocytes

and natural killer cells, while demonstrating positive associations

with M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, neutrophils and CAFs (Fig. 6A; Table

SV). These observations suggested an intricate immune

microenvironment characterized by stromal activation and

immunosuppression in the high-risk score group. Furthermore, the

expression profiles of immune checkpoint proteins (ICPs) were

examined. Within the high-risk score group, significant

upregulation of certain ICPs was observed, including CD70, CD44,

CD276 and VTCN1, while others such as CD200, TNFRSF4, CD160,

ADORA2A and TNFRSF14 exhibited significant downregulation (Fig. 6B). These findings hold promise in

offering potential immunotherapeutic options for the clinical

management of patients with PC.

| Figure 6.Association of immune status and

immunotherapy with the cuproptosis-related signature in pancreatic

cancer. (A) Correlation of immune infiltration with risk score. (B)

Boxplots of immune checkpoint gene expression in distinct risk

score groups. Boxplots indicating ssGSEA score of (C) CAFs, (D)

TGF-β-associated ECM and (E) anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response in

different risk score groups. (F) Time-dependent receiver operating

characteristic curves depicting the predictive precision of risk

score and existing biomarkers (PD-L1, MSI score and TMB) for

evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy. (G) Correlation analysis

between risk score, cuproptosis ssGSEA score, PD-L1, MSI score, TMB

and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response. (H) TMB in different risk

score groups. (I) Survival analysis among four patient groups

stratified by both TMB and risk score. (J and K) Waterfall plot of

somatic mutation features established with low and high-risk

scores. Each column represents an individual patient. The upper bar

plot indicates TMB, the number on the right indicates the mutation

frequency in each gene. The right bar plot demonstrates the

proportion of each variant type. ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001,

**P<0.01, *P<0.05, analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

MSI, microsatellite instability; TMB, tumor mutational burden;

ssGSEA, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis; CAFs,

cancer-associated fibroblasts; ECM, extracellular matrix; PD-1,

programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death

ligand-1; AUC, area under the curve. |

Considering the well-established association between

stromal activation and tumor immune evasion (47–49),

the present investigation was extended to delineate distinct gene

signatures among patients with different risk scores. Among

patients with a high-risk score, heightened expression of stromal

activation-associated signatures, such as CAFs and the

TGF-β-associated ECM, was observed (Fig. 6C and D). The expression of a

signature associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy was also

more pronounced in patients with a high-risk score (Fig. 6E), suggesting a potential challenge

in achieving favorable responses to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy within

this subgroup. In addition, risk score was compared with currently

known biomarkers [such as PD-L1, microsatellite instability score

and tumor mutational burden (TMB)] to evaluate the efficacy of

immunotherapy and the results revealed that the risk score had

enhanced potential to predict prognosis (Fig. 6F), despite the higher correlation

between PD-L1 and resistance to anti-PD-1 score (Fig. 6G). The aforementioned results

suggested that the risk score may be closely associated with tumor

immunotherapeutic markers and has the potential to be used as a

novel immunotherapeutic marker.

Genomic mutation analysis for the

cuproptosis-related signature

Prior research has consistently demonstrated an

association between TMB and immune infiltration, as well as its

prognostic implications across various types of cancer (50–52).

In the present comprehensive mutation dataset analysis, a

significantly elevated TMB score was observed in the high-risk

score group when compared with the low-risk score group (Fig. 6H). Furthermore, survival analysis

revealed a markedly improved prognosis among patients with lower

TMB scores and lower risk scores compared with higher TMB scores

and higher risk scores (P<0.001; Fig. 6I). PC is characterized by a complex

genetic landscape, with frequent somatic mutations occurring in key

driver genes, notably KRAS, CDKN2A, TP53 and SMAD4 (53). In this context, an in-depth

assessment of the distribution patterns of somatic alterations

between the two distinct risk score groups within TCGA-PAAD cohort

was conducted. Notably, TP53, KRAS, CDKN2 and SMAD4 emerged as the

primary mutated genes in both high- and low-risk score groups

(Fig. 6J and K). Patients

classified in the high-risk score category exhibited substantially

higher frequencies of TP53, KRAS, CDKN2 and SMAD4 mutations

compared with their counterparts in the low-risk score group.

Conversely, the mutation percentages for TTN, RNF43, MUC16 and RYR1

were not significantly different between the groups. These findings

underscore the complex interplay between TMB, risk score and the

genetic landscape of PC, shedding light on potential prognostic

markers and therapeutic options.

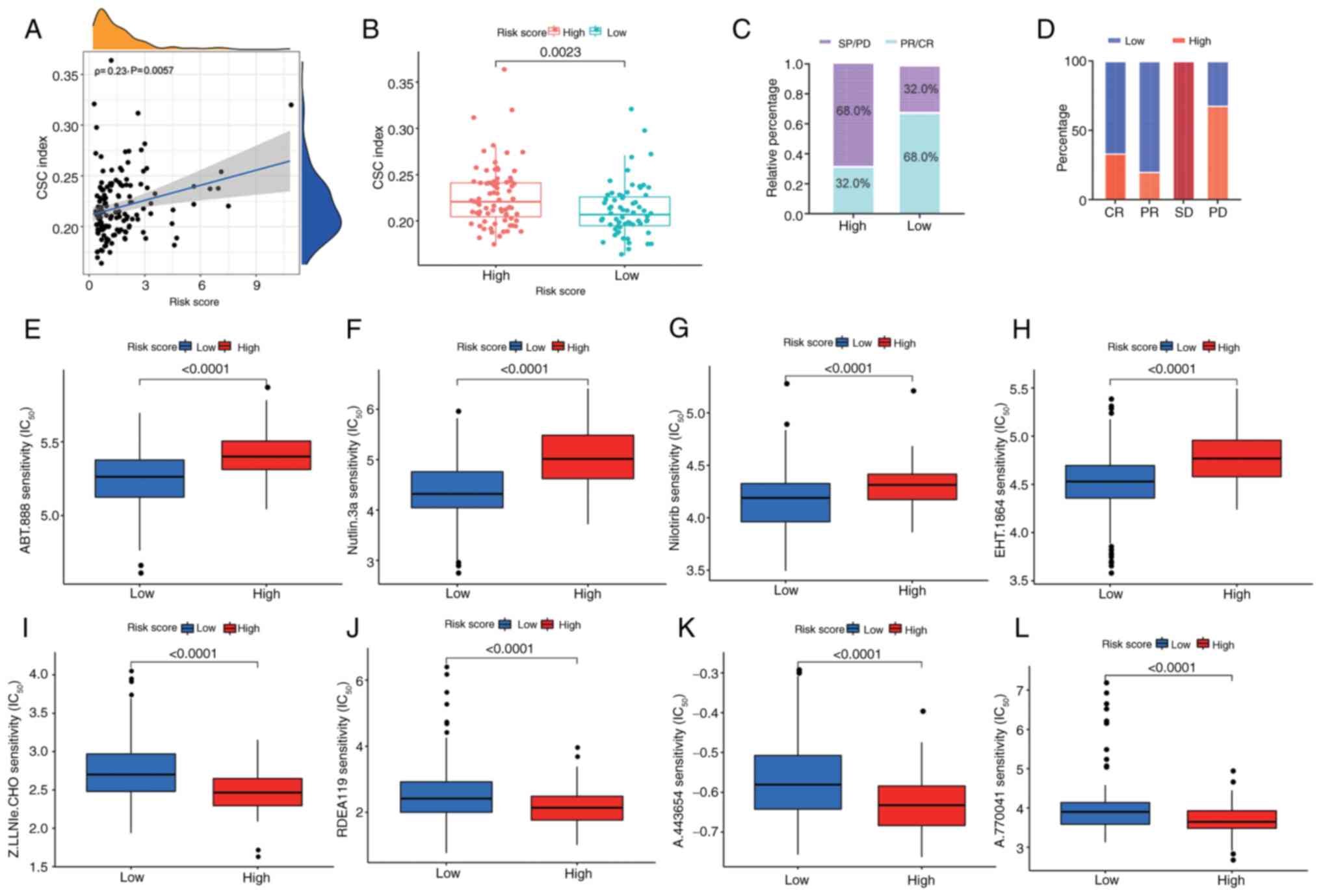

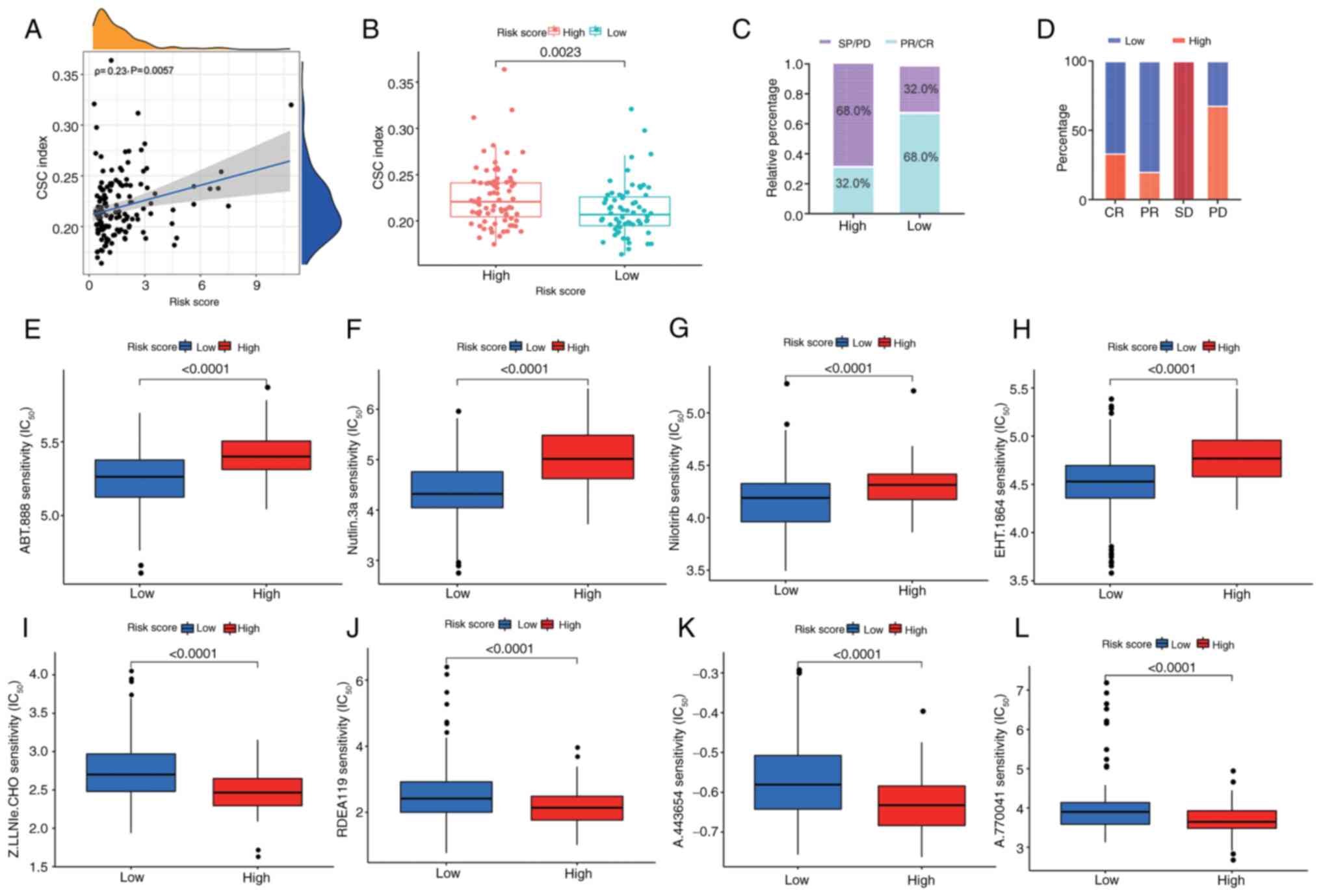

Association of the cuproptosis-related

signature with cancer stem cell (CSC) score and clinical outcomes

in PC

CSCs promote tumorigenesis and metastasis in PC

(54,55). PC stem cell proliferation is notably

inhibited by diethyldithiocarbamate-copper complex loaded into

hyaluronic acid-decorated liposomes (56). Therefore, the present study analyzed

the correlation between the cuproptosis-related signature and CSC

index values and a weak correlation was observed between the risk

score and the CSC index (ρ=0.23, P=0.0057; Fig. 7A). There was a higher CSC score in

the high-risk score group compared with that in the low-risk score

group (P=0.0024; Fig. 7B), which

indicates that stem cells have more notable stemness and lower

differentiation characteristics in the high-risk score group.

Furthermore, to investigate the impact of risk score on clinical

outcomes in patients with PC, therapeutic information and clinical

outcomes from TCGA were assessed. As shown in Fig. 7C and D, a high-risk score was

associated with a higher rate of progressive disease and stable

disease.

| Figure 7.Associations between

cuproptosis-related signature and CSC score, clinical outcomes and

drug susceptibility in PC. (A) Spearman's rank correlation analysis

of risk score and CSC index. (B) CSC score in distinct risk score

groups. (C) Ratio of worse outcomes after surgery was notably

elevated in the higher risk score group. (D) Proportion of clinical

outcomes in patients with PC with high- and low-risk scores after

surgery. Top four chemotherapeutic drugs, (E) ABT-888, (F)

nutlin-3a, (G) nilotinib and (H) EHT 1864 exhibiting sensitivity

for patients with PC with a low-risk score. Top four

chemotherapeutic drugs (I) Z-LLNle-CHO, (J) RDEA119, (K) A-443654

and (L) A-770041 exhibiting sensitivity for patients with PC with a

high-risk score. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

CSC, cancer stem cell; PC, pancreatic cancer; SD, stable disease;

PD, progressive disease; CR, complete response; PR, partial

response; IC50, half maximal inhibitory

concentration. |

Drug susceptibility according to the

cuproptosis-related signature

Subsequently, to confirm the efficacy of risk score

as a predictive biomarker for therapeutic response in patients with

PC, the IC50 values of 138 chemotherapeutic drugs from

the GDSC dataset were assessed in TCGA-PAAD dataset. A total of 29

drugs were more sensitive in patients with a low-risk score

(P<0.05; Table SVI), among

which the leading chemotherapeutic agents were: ABT-888, nutlin-3a,

nilotinib and EHT 1864 (Fig. 7E-H).

A total of 54 drugs demonstrated an improved response in patients

with a high-risk score (P<0.05; Table SVII), among which the top four

chemotherapeutic drugs were Z-LLNle-CHO, RDEA119, A-443654 and

A-770041 (Fig. 7I-L). Together,

these findings indicated that risk score may be associated with

drug sensitivity.

Discussion

For patients with advanced PC, conventional

treatments including chemotherapy and targeted therapy have little

effect on improving prognoses and limiting tumor progression

(3,7,23,47,49).

It is therefore urgent to screen valuable biomarkers that can

classify patients with different molecular characteristics into

diverse subgroups, and predict prognosis and treatment. Copper

accumulation triggers mitochondrial-driven cell death, known as

cuproptosis, which is associated with tumor progression (20,21,32,57).

Hence, exploring the regulatory effects of cuproptosis on tumors

and its molecular mechanisms is key, as it may provide novel

directions and strategies for clinical cancer treatment.

The present study indicated that apoptosis,

necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis were aberrantly

hyperactivated in PC tissues and cuproptosis exhibited the only

protective effect on survival compared with the other cell death

modes. The present study further analyzed the gene variants of CGs.

Among 10 CGs, the frequency of CDKN2A mutations was the highest.

Correlation analysis revealed that CDKN2A and DLAT were associated

with cuproptosis score. The aggregation of gene mutations leads to

tumorigenesis and gene mutations in PC, which may notably impact

immunotherapy response. It has been reported that mutations in

CDKN2A are frequently identified in a number of primary tumors and

patients with melanoma carrying CDKN2A gene mutations respond

better to immunotherapy (50). The

latest research has indicated that copper nanoparticles enhance

cuproptosis and immunotherapy response in PC (58). This evidence suggests that CDKN2A

mutations may be associated with cuproptosis and could affect

immunotherapy. The present study further verified the protein level

of CGs using PC proteomics analysis and the results indicated an

inconsistency between the protein and transcription levels of CGs,

which may be associated with the heterogeneity in human tissue and

plasma samples.

Previous studies have shown that the combination of

Tussah silk fibroin nanoparticles and PD-L1 effectively induces

cuproptosis and reshapes the TME in PC (59,60).

In addition, advanced cancer-infiltrating and killing abilities of

natural killer, CD8+ T cells and neutrophils have been

reported to be associated with FDX1 expression; the levels of FDX1

are decreased in several types of cancer and reflect the level of

immune cell infiltration (61).

Targeted activation of cuproptosis pathways may favor re-activation

of the TME towards the eradication of cancer cells (57). Targeted activation of CGs may be

investigated as priming or contributing factors for improving

current immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) immunotherapy (20,24).

PC is characterized by extensive stromal

involvement, which makes classifying precise tumor-specific

molecular subtypes difficult (47).

Stromal cells, as a vital component of the TME, serve an important

role in monitoring tumor immune evasion, even in the presence of

abundant immune cells. Increasing evidence has also shown the

effects of stromal cells on tumor progression and therapeutic

resistance (30,46). Consistently, the present study

revealed that the patients with PC in CG cluster B had a worse OS

and a higher stromal score, as well as increased enrichment of

Tregs, CAFs, TGF-β-associated ECM and anti-PD-1 resistance, thus

limiting antitumor immunity and leading to poor survival. Previous

studies have demonstrated that CAFs can attract Tregs and enhance

the capacity of inhibiting effector T-cell proliferation (62,63).

In addition, TGF-β-associated ECM has been shown to be associated

with CAFs, immune evasion and immunotherapy failure (48,64).

Furthermore, stromal activation signatures, such as CAFs and

TGF-β-associated ECM, were highly expressed in patients with a

high-risk score. Notably, a higher anti-PD-1 resistant-related

signature was also observed in the high-risk score group,

confirming the existing conclusions. Thus, based on the

aforementioned results, one possible mechanism for CGs in the PC

TME was suggested: CGs could stimulate extensive stromal

involvement of tumors and regulate CAF activation, as well as

TGF-β-associated ECM hyperactivation, which in turn may recruit

immunosuppressive cell populations, such as Tregs, causing tumor

immune escape.

In addition, a CG signature was established to

predict clinical outcome, immunotherapy response and chemotherapy

susceptibility in PC. By integrating the risk score and clinical

variables, a quantitative nomogram was generated to further improve

the performance and facilitate the clinical utility of the

signature. To determine potential drug therapy targets for patients

with PC, the present study identified the potential sensitive drugs

for patients in diverse risk score groups. The results indicated

that the risk score may be a robust prognostic biomarker, which

could contribute to precise risk stratifications and offer clues

for combining customized prognostic prediction with individualized

therapy. For patients with a high-risk score, the present study

identified the latent therapeutic drugs that could effectively

improve their survival. For patients with a low-risk score,

clinicians may consider adopting ICI immunotherapy to improve the

survival of patients with PC.

In conclusion, these findings highlighted the

overall phenotypic role of CGs in PC and identified obvious

differences in prognosis, clinical features and TME characteristics

between two CG subtypes. Furthermore, a novel prognostic CG

signature was defined in PC; this CG score may act as a robust

prognostic indicator for patients with PC, which offers potential

for precise risk stratification and predictive markers for

effective immunotherapy strategies.

However, certain limitations of the present study

should be acknowledged. First, the present study did not include

any datasets associated with immunotherapy for PC and could not be

verified, therefore future research is warranted for the validation

in PC immunotherapy datasets. Second, the CG scoring system is a

gene set consisting of five genes, thus, it cannot be quantified in

in vivo and in vitro experiments. The utility of the

CG scoring system is limited to retrospective studies of tumor

tissue specimens; therefore, future studies can evaluate and select

the most valuable genes for experimental verification.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82403378), the China National

Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (grant no. BX20240072)

and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no.

2024M750525).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WG conceptualized and designed the present study,

prepared the materials, collected data, performed the data analysis

and wrote first draft of the manuscript. YoW and DS prepared the

materials, collected data and revised the manuscript. MY and YaW

cultivated pancreatic cancer cell lines, prepared the total

cellular RNA samples and reviewed the manuscript. WG, YoW, DS, MY

and YaW confirm the authenticity of the data in the present study.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Stoop TF, Javed AA, Oba A, Koerkamp BG,

Seufferlein T, Wilmink JW and Besselink MG: Pancreatic cancer.

Lancet. 405:1182–1202. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cai J, Chen H, Lu M, Zhang Y, Lu B, You L,

Zhang T, Dai M and Zhao Y: Advances in the epidemiology of

pancreatic cancer: Trends, risk factors, screening, and prognosis.

Cancer Lett. 520:1–11. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bergman PJ: Cancer immunotherapy. Vet Clin

North Am Small Anim Pract. 54:441–468. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang K, Halima A and Chan TA: Antigen

presentation in cancer-mechanisms and clinical implications for

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:604–623. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bednar F and Pasca di Magliano M:

Context-dependent immune responses explain pancreatic cancer

immunoresistance. Cancer Cell. 37:261–263. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Farhangnia P, Khorramdelazad H, Nickho H

and Delbandi AA: Current and future immunotherapeutic approaches in

pancreatic cancer treatment. J Hematol Oncol. 17:402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fan JQ, Wang MF, Chen HL, Shang D, Das JK

and Song J: Current advances and outlooks in immunotherapy for

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 19:322020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gibellini L and Moro L: Programmed cell

death in health and disease. Cells. 10:17652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu Y, Fleishman JS, Wang H and Huo L:

Pharmacologically targeting ferroptosis and cuproptosis in

neuroblastoma. Mol Neurobiol. 62:3863–3876. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tsang T, Davis CI and Brady DC: Copper

biology. Curr Biol. 31:R421–R427. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kahlson MA and Dixon SJ: Copper-induced

cell death. Science. 375:1231–1232. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tang D, Chen X and Kroemer G: Cuproptosis:

A copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell Res.

32:417–418. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sun L, Zhang Y, Yang B, Sun S, Zhang P,

Luo Z, Feng T, Cui Z, Zhu T, Li Y, et al: Lactylation of METTL16

promotes cuproptosis via m6A-modification on FDX1 mRNA

in gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 14:65232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jiang Y, Huo Z, Qi X, Zuo T and Wu Z:

Copper-induced tumor cell death mechanisms and antitumor

theragnostic applications of copper complexes. Nanomedicine (Lond).

17:303–324. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tang D, Kroemer G and Kang R: Targeting

cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

21:370–388. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu WQ, Lin WR, Yan L, Xu WH and Yang J:

Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in cancer immunity and therapy.

Immunol Rev. 321:211–227. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xie J, Yang Y, Gao Y and He J:

Cuproptosis: Mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer.

22:462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tarin M, Babaie M, Eshghi H, Matin MM and

Saljooghi AS: Elesclomol, a copper-transporting therapeutic agent

targeting mitochondria: From discovery to its novel applications. J

Transl Med. 21:7452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

O'Day S, Gonzalez R, Lawson D, Weber R,

Hutchins L, Anderson C, Haddad J, Kong S, Williams A and Jacobson

E: Phase II, randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of weekly

elesclomol plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone for stage IV

metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 27:5452–5458. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Qin Y, Liu Y, Xiang X, Long X, Chen Z,

Huang X, Yang J and Li W: Cuproptosis correlates with

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment based on pan-cancer

multiomics and single-cell sequencing analysis. Mol Cancer.

22:592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gadiyar V, Lahey KC, Calianese D, Devoe C,

Mehta D, Bono K, Desind S, Davra V and Birge RB: Cell death in the

tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy.

Cells. 9:22072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gao L, Shay C and Teng Y: Cell death

shapes cancer immunity: Spotlighting PANoptosis. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 43:1682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hänggi K and Ruffell B: Cell death,

therapeutics, and the immune response in cancer. Trends Cancer.

9:381–396. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y,

Sun Y, Zeng F, Chen X and Deng G: Ferroptosis in cancer: From

molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Du T, Gao J, Li P, Wang Y, Qi Q, Liu X, Li

J, Wang C and Du L: Pyroptosis, metabolism, and tumor immune

microenvironment. Clin Transl Med. 11:e4922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Han X, Zhang WH, Wang WQ, Yu XJ and Liu L:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts in therapeutic resistance of

pancreatic cancer: Present situation, predicaments, and

perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1874:1884442020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Storrs EP, Chati P, Usmani A, Sloan I,

Krasnick BA, Babbra R, Harris PK, Sachs CM, Qaium F, Chatterjee D,

et al: High-dimensional deconstruction of pancreatic cancer

identifies tumor microenvironmental and developmental stemness

features that predict survival. NPJ Precis Oncol. 7:1052023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang W, Lu K, Jiang X, Wei Q, Zhu L, Wang

X, Jin H and Feng L: Ferroptosis inducers enhanced cuproptosis

induced by copper ionophores in primary liver cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 42:1422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Reggiardo RE, Maroli SV, Peddu V, Davidson

AE, Hill A, LaMontagne E, Aaraj YA, Jain M, Chan SY and Kim DH:

Profiling of repetitive RNA sequences in the blood plasma of

patients with cancer. Nat Biomed Eng. 7:1627–1635. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Song CX, Yin S, Ma L, Wheeler A, Chen Y,

Zhang Y, Liu B, Xiong J, Zhang W, Hu J, et al:

5-Hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in cell-free DNA provide

information about tumor types and stages. Cell Res. 27:1231–1242.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Digre A and Lindskog C: The human protein

atlas-spatial localization of the human proteome in health and

disease. Protein Sci. 30:218–233. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sabah A, Tiun S, Sani NS, Ayob M and Taha

AY: Enhancing web search result clustering model based on multiview

multirepresentation consensus cluster ensemble (mmcc) approach.

PLoS One. 16:e02452642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Seiler M, Huang CC, Szalma S and Bhanot G:

ConsensusCluster: A software tool for unsupervised cluster

discovery in numerical data. OMICS. 14:109–113. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney J:

GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data.

BMC. 14:72013.

|

|

39

|

Wu D, Liu Y, Liu J, Ma L and Tong X:

Myeloid cell differentiation-related gene signature for predicting

clinical outcome, immune microenvironment, and treatment response

in lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 14:174602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Huang L, Wu C, Xu D, Cui Y and Tang J:

Screening of important factors in the early sepsis stage based on

the evaluation of ssGSEA algorithm and ceRNA regulatory network.

Evol Bioinform Online. 17:117693432110584632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C

and Koeffler HP: Maftools: Efficient and comprehensive analysis of

somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28:1747–1756. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Geeleher P, Cox N and Huang RS:

pRRophetic: An R package for prediction of clinical

chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS

One. 9:e1074682014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ringnér M: What is principal component

analysis? Nat Biotechnol. 26:303–304. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sherman MH and Beatty GL: Tumor

microenvironment in pancreatic cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic

resistance. Annu Rev Pathol. 18:123–148. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, Volmar

KE, Loeza SG, Hoadley KA, Rashid NU, Williams LA, Eaton SC, Chung

AH, et al: Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and

stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat

Genet. 47:1168–1178. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P

and De Carvalho DD: TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes

link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and

immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun. 9:46922018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb

WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, Cooc J, Weinkle J, Kim GE, Jakkula L, et al:

Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing

responses to therapy. Nat Med. 17:500–503. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN,

Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ,

Omuro A, et al: Tumor mutational load predicts survival after

immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 51:202–206.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Kang K, Xie F, Mao J, Bai Y and Wang X:

Significance of tumor mutation burden in immune infiltration and

prognosis in cutaneous melanoma. Front Oncol. 10:5731412020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

McNamara MG, Jacobs T, Lamarca A, Hubner

RA, Valle JW and Amir E: Impact of high tumor mutational burden in

solid tumors and challenges for biomarker application. Cancer Treat

Rev. 89:1020842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hayashi A, Hong J and Iacobuzio-Donahue

CA: The pancreatic cancer genome revisited. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 18:469–481. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Leng S, Huang W, Chen Y, Yang Y, Feng D,

Liu W, Gao T, Ren Y, Huo M, Zhang J, et al: SIRT1 coordinates with

the CRL4B complex to regulate pancreatic cancer stem cells to

promote tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 28:3329–3343. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF,

Zhang L, Adsay V, Wicha M, Clarke MF and Simeone DM: Identification

of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 67:1030–1037. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Marengo A, Forciniti S, Dando I, Dalla

Pozza E, Stella B, Tsapis N, Yagoubi N, Fanelli G, Fattal E,

Heeschen C, et al: Pancreatic cancer stem cell proliferation is

strongly inhibited by diethyldithiocarbamate-copper complex loaded

into hyaluronic acid decorated liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen

Subj. 1863:61–72. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Babak MV and Ahn D: Modulation of

intracellular copper levels as the mechanism of action of

anticancer copper complexes: Clinical relevance. Biomedicines.

9:8522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Helgadottir H, Ghiorzo P, van Doorn R,

Puig S, Levin M, Kefford R, Lauss M, Queirolo P, Pastorino L,

Kapiteijn E, et al: Efficacy of novel immunotherapy regimens in

patients with metastatic melanoma with germline CDKN2A mutations. J

Med Genet. 57:316–321. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wang P, Guo W, Liu S, Li S, Li J, Ding B,

Yin F, Yang Y, Li X, Cao P, et al: Novel simplePt@PCN-Cu-induced

cuproptosis amplifies αPD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma through mitochondrial HK2-mediated PD-L1

upregulation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 44:1492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Gao S, Ge H, Gao L, Gao Y, Tang S, Li Y,

Yuan Z and Chen W: Silk Fibroin nanoparticles for enhanced

cuproptosis and immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer treatment. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 12:e24176762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang C, Zeng Y, Guo X, Shen H, Zhang J,

Wang K, Ji M and Huang S: Pan-cancer analyses confirmed the

cuproptosis-related gene FDX1 as an immunotherapy predictor and

prognostic biomarker. Front Genet. 13:9237372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Costa A, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A,

Pelon F, Bourachot B, Cardon M, Sirven P, Magagna I, Fuhrmann L,

Bernard C, et al: Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive

environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 33:463–479.e10.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Huang H, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Pradhan RN,

Ganguly D, Chandra R, Murimwa G, Wright S, Gu X, Maddipati R, et

al: Mesothelial cell-derived antigen-presenting cancer-associated

fibroblasts induce expansion of regulatory T cells in pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Cell. 40:656–673.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Derynck R, Turley SJ and Akhurst RJ: TGFβ

biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 18:9–34. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|