Introduction

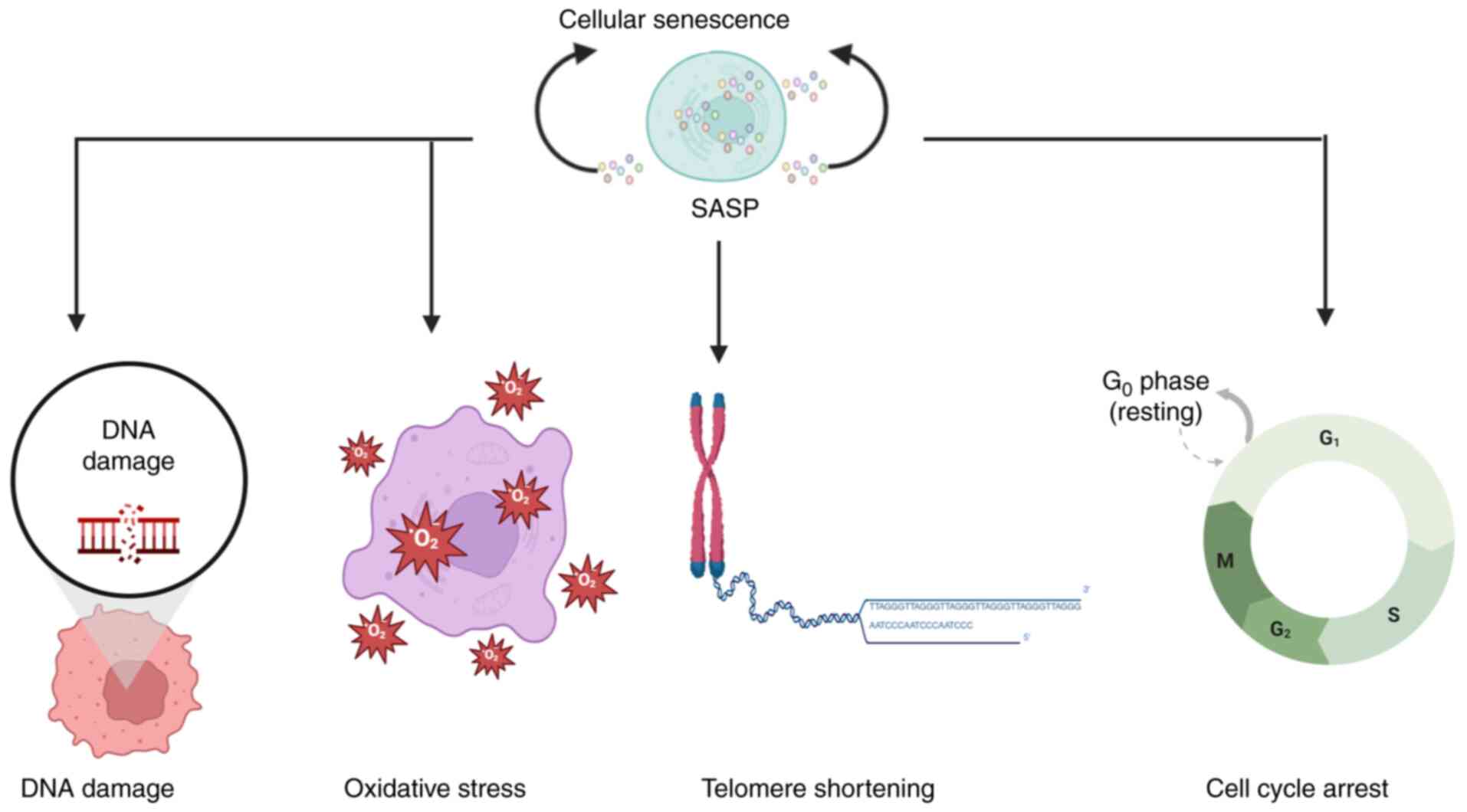

Cellular senescence exhibits a paradoxical dual role

in cancer biology, acting both as a barrier to tumorigenesis and as

a facilitator of tumor progression (Fig. 1) (1). In early tumor development, senescence

serves as a key tumor-suppressive mechanism by enforcing stable

cell cycle arrest through the p53/p21 and p16/ribosome (Rb)

pathways, thereby restricting the proliferation of damaged cells

(1,2). By contrast, increasing evidence

indicates that the senescence-associated secretory phenotype

(SASP), comprising inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6 and IL-8),

growth factors and matrix-remodeling enzymes, can paradoxically

foster tumorigenesis through extensive remodeling of the tumor

microenvironment (TME) (2,3).

Despite these advances, several critical questions

remain unresolved: How do distinct components of the SASP

differentially influence tumor progression across cancer types? How

can we harness the cytoprotective properties of senescence while

avoiding its pro-tumorigenic effects? Recent findings underscore

the context-dependent nature of interactions between senescent

cells and the TME, which highlights the need for precision

strategies in senescence-targeted interventions (4–6). The

present review aims to address these gaps by dissecting SASP

heterogeneity and its therapeutic implications, and by evaluating

emerging modalities, including senolytics and SASP modulators, that

hold the potential to reshape cancer treatment paradigms.

Precise molecular targeting remains central to

therapeutic success, particularly in virus-associated malignancies.

For instance, hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) drives

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) via regulating the expression of

microRNAs, underscoring the critical role of viral proteins in

promoting malignant transformation (5); additionally, distinct genotypes of

human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1)-a virus closely

associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma-exhibit varying

prevalence among populations with 1.5% among blood donors in Iran)

and correlate with differential cancer susceptibility, which

supports genotype-based stratified screening for this hematological

malignancy (6–9). These observations underscore the

necessity for tailored screening and intervention strategies.

Within the TME, SASP-driven remodeling orchestrates

immune evasion, angiogenesis and therapeutic resistance,

compounding the complexity of cancer management (2,10,11).

In advanced disease, the persistent accumulation of senescent cells

and their secretome fosters an immunosuppressive niche through

recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and T-cell

dysfunction, while promoting metastatic dissemination (12,13).

This dynamic interplay between the protective and

deleterious facets of senescence has spurred the development of

targeted senotherapies (10,13).

Current approaches encompass the following: i) Senolytic agents,

which selectively ablate detrimental senescent cells (e.g.,

dasatinib-quercetin combinations); ii) senomorphic compounds, which

attenuate harmful SASP components without eliminating senescent

cells; and iii) novel candidates inspired by Traditional Chinese

Medicine (e.g., resveratrol), which may fine-tune senescence

responses (10,13,14).

Yet, notable challenges persist in clinical translation, including

the identification of biomarkers to distinguish protective from

pathogenic senescent subsets, mitigation of therapy-induced

SASP-mediated resistance and optimization of therapeutic timing to

maximize benefit while limiting harm (2,11).

Emerging evidence suggests that integrating

senescence-targeted agents with established treatments, such as

immunotherapy, may potentiate therapeutic efficacy (12). Advancing these strategies will

require robust preclinical models that accurately recapitulate the

complexity of the human TME (15,16).

Furthermore, incorporating single-cell profiling technologies and

systematically evaluating combination regimens, including those

pairing traditional Chinese and Western medicines, will be key to

fully exploit the therapeutic promise of senescence modulation in

oncology (14).

A nuanced understanding of cellular senescence in

cancer underscores its dualistic nature and positions it as an

attractive yet challenging therapeutic target. Future research can

delineate the molecular determinants that dictate whether

senescence exerts tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting effects in

specific contexts, paving the way for precision interventions that

may potentially offer clinical benefit (1,2,11,12).

Dual-faced nature of cellular senescence in

cancer

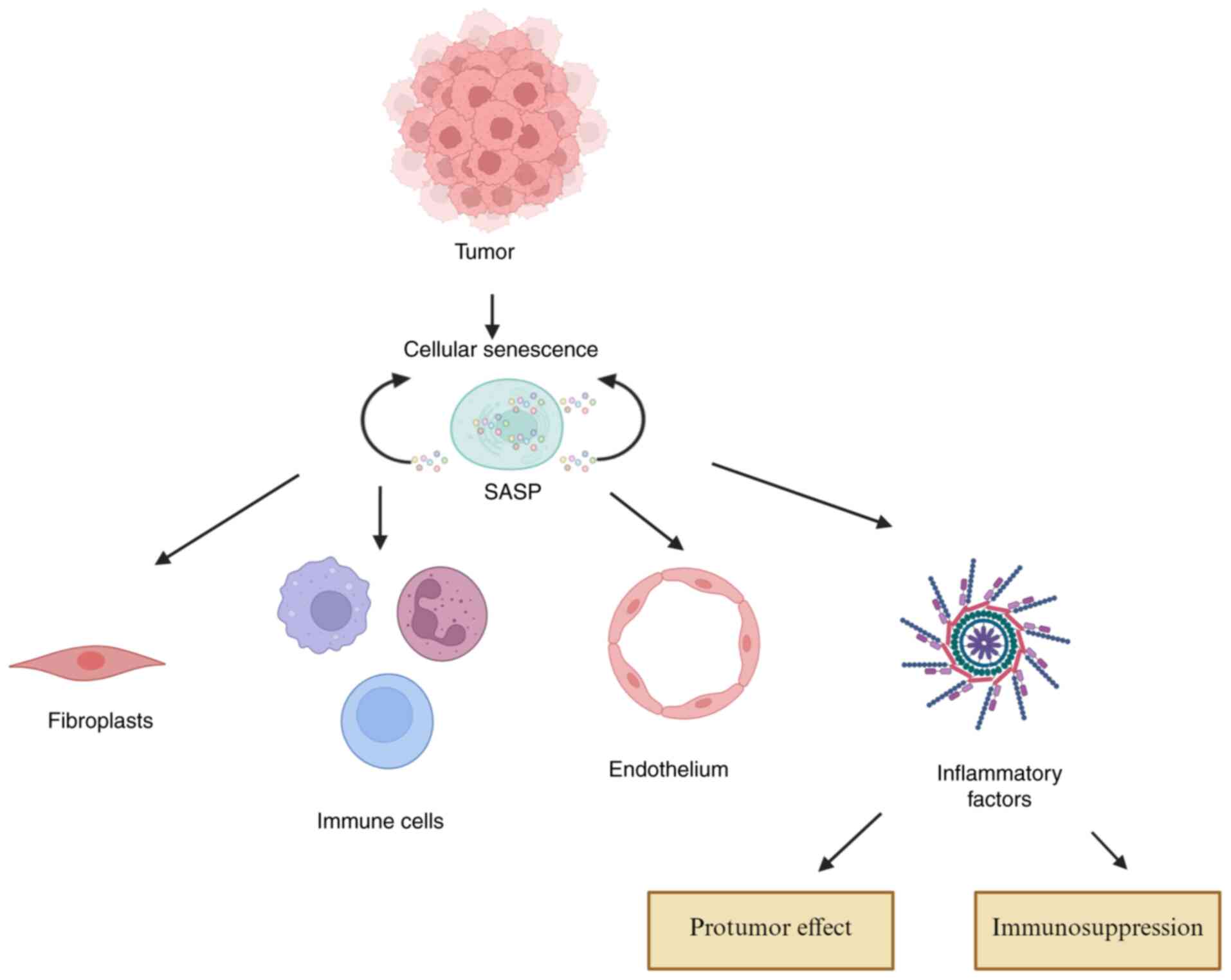

Cellular senescence exerts a paradoxical influence

on cancer, functioning as both a tumor suppressor and promoter

(17) (Fig. 2). In the early stages of

tumorigenesis, senescence operates as a key defense mechanism,

arresting the proliferation of damaged cells via the p53/p21 and

p16/Rb pathways, thereby preventing malignant transformation

(2,18–21).

This protective effect is mediated by cell-autonomous processes

such as growth arrest and by non-cell-autonomous mechanisms through

SASP, which remodels the TME via cytokines, chemokines and

matrix-degrading enzymes (21–24).

For instance, in HCC, senescent cells suppress tumor initiation

through activation of p53-p21-Rb signaling, whereas SASP-derived

IL-24 recruits cytotoxic T cells to eliminate premalignant cells

(5,25).

By contrast, at advanced stages, the SASP

paradoxically fosters tumor progression by establishing an

inflammatory niche conducive to metastasis and therapeutic

resistance (15,26–33).

This duality is shaped by tumor-specific microenvironmental

contexts, resulting in divergent outcomes that can either restrain

or accelerate cancer progression (34,35).

In gastric cancer (GC), SASP-derived IL-6 and C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand 12 (CXCL12) promote immune evasion and extracellular matrix

(ECM) remodeling by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells

(MDSCs) and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (5,25).

Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma, SASP-driven upregulation of

secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) and Tenascin enhances invasion and

immune escape through CD44 and integrin signaling (26,31).

Furthermore, senescence-associated epigenetic alterations, such as

the demethylation of histone 3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2, a

key repressive histone modification), can reactivate oncogenes such

as yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), driving chemoresistance in GC

(36).

The TME further modulates these outcomes, producing

cancer type-specific consequences (15,26-29,31,32). In melanoma,

the expression of senescence-associated genes, including BRCA2, is

associated with increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration and

favorable prognosis (37). By

contrast, in HCC, high senescence scores are associated with

elevated tumor mutational burden and poor survival, mediated by

immunosuppressive SASP components (38,39).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) also influence this dynamic; for

instance, nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1)

suppresses senescence in HCC by stabilizing kinesin family member

11 (KIF11) and repressing CDK inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) transcription

(5), which underscores the

context-dependent regulation of senescence across malignancies.

These opposing roles highlight the necessity of

nuanced therapeutic strategies. Recent advances in senotherapy aim

to exploit this complexity by selectively eliminating deleterious

senescent cells using senolytics (e.g., dasatinib plus quercetin),

attenuating SASP signaling via senomorphics or integrating these

approaches with standard treatments (40,41).

Key challenges include distinguishing beneficial from pathological

senescence and mitigating therapy-induced senescence in normal

tissues, which may drive recurrence (42). Future directions emphasize the

development of: i) Biomarkers for senescent subpopulation

profiling; ii) temporal control of senescence induction; and iii)

combinatorial regimens to optimize efficacy while minimizing

adverse effects. Successfully addressing these hurdles could

transform cancer therapy by harnessing the protective potential of

senescence while neutralizing its pro-tumorigenic properties

(39,41). However, notable barriers remain

before these strategies can be translated into safe and effective

clinical applications.

Underlying mechanisms of context-dependent

cellular senescence in cancer

Cellular senescence exhibits pronounced context

dependency in cancer, functioning as either a tumor-suppressive

barrier or a tumor-promoting factor depending on the specific

biological and microenvironmental context. This paradox stems from

the interplay between tumor-specific biology, SASP heterogeneity

and dynamic remodeling of the TME. The present review delineates

the core mechanisms underlying these contradictions, drawing on

evidence from specific cancer types highlighted below.

The SASP is highly heterogeneous; its composition,

cytokines, chemokines and matrix-remodeling enzymes show a marked

variation across cancer types, like breast cancer, gastric cancer,

lung adenocarcinoma, HCC, melanoma, colorectal cancer and glioma,

shaping the functional outcome of senescence. In melanoma,

senescent cells secrete factors that enhance antitumor immunity.

For instance, senescence-associated genes such as BRCA2 are

associated with increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells,

a hallmark of effective immune surveillance (37). Consistent with this, the SASP in

melanoma tends to favor pro-inflammatory cytokines that recruit

cytotoxic lymphocytes, which may potentially promote tumor

suppression (25).

By contrast, HCC exhibits a pro-tumor SASP profile.

High senescence scores in HCC are associated with elevated

immunosuppressive factors that attract MDSCs and CAFs (38,39).

These factors remodel the TME, promoting immune evasion and ECM

deposition, thereby converting senescence into a tumor-promoting

force. Such disparities underscore that SASP-driven outcomes depend

on its specific components: Pro-immune vs. immunosuppressive

factors determine whether senescence restrains or accelerates tumor

growth.

The immune architecture of the TME further amplifies

these contradictions, as senescent cells recruit distinct immune

subsets via SASP signaling. In melanoma, senescence-associated cues

bolster adaptive immunity; as noted, senescence-related genes are

associated with enhanced CD8+ T-cell infiltration,

suggesting a pro-inflammatory, antitumor milieu (37). By contrast, in other malignancies,

senescence dampens immune surveillance. In GC, senescent cells

foster immune suppression via SASP. SASP-derived IL-6 and CXCL12,

for instance, recruit MDSCs and regulatory T cells (Tregs),

blunting cytotoxic T-cell activity and enabling immune escape

(27,28). Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma,

SASP-induced SPP1 and Tenascin interact with CD44 and integrins on

immune cells, impairing their cytotoxicity and promoting evasion

(26,31). These examples demonstrate that the

net effect of senescence hinges on the immune subsets it recruits,

cytotoxic vs. immunosuppressive.

Intrinsic genetic and epigenetic programs further

govern this context dependency by modulating senescence pathway

activity. In HCC, the lncRNA NEAT1 represses senescence by

stabilizing KIF11 and inhibiting CDKN2A transcription, a key

senescence inducer (5). This

epigenetic silencing diminishes the tumor-suppressive capacity of

senescence, which allows malignant cells to evade growth arrest. By

contrast, such repressive mechanisms appear less pronounced in

melanoma, enabling senescence to exert antitumor effects. In

glioma, TNF receptor-associated factor 7 knockdown induces

senescence and synergizes with lomustine to suppress tumor growth

(43). This contrasts with HCC,

where senescence pathways are often epigenetically silenced,

conferring resistance to similar strategies. Thus, the genetic and

epigenetic landscape, including lncRNA networks and senescence gene

expression, notably determines whether senescence serves as a

barrier or is co-opted for tumor progression.

Senescence also evolves with the tumor stage,

shifting from protective in early disease to deleterious in

advanced stages. Initially, senescence acts as a barrier to

transformation through p53/p21- and p16/Rb-mediated cell cycle

arrest (1,2). In premalignant lesions, SASP factors,

like IL-6, TNF-α, p21/p16, SPP1, MMPs and YAP1, may trigger

immune-mediated clearance of damaged cells (5,27). At

later stages, persistent senescence and chronic SASP reshape the

TME to foster metastasis and therapy resistance. In lung

adenocarcinoma, late-stage senescent cells upregulate SPP1, which

enhances invasiveness (31), while

in GC, senescence-driven H3K9me2 demethylation reactivates

oncogenes such as YAP1, which promotes chemoresistance (36). This stage-dependent shift

underscores the dynamic nature of senescence and its adaptation to

the evolving tumor ecosystem.

In summary, the opposing roles of cellular

senescence in cancer arise from SASP heterogeneity, immune

composition of the TME, cancer-specific regulatory networks and

disease stage. Deciphering these context-dependent mechanisms is

essential for precision strategies that exploit the

tumor-suppressive effects of senescence while mitigating its

pro-tumor consequences. These insights underpin the rationale for

SASP-targeted interventions, such as inhibiting the IL-6/STAT3

pathway in breast cancer or blocking the IL-8/CXCR2 axis in lung

cancer (33,34) (Table

I), to enable more effective senotherapy.

| Table I.Therapeutic strategies harnessing

context-specific senescence mechanisms. |

Table I.

Therapeutic strategies harnessing

context-specific senescence mechanisms.

| Therapeutic

strategy | Mechanism of

action | Target cancer

types | Key findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Senolytics

(exisulind) | Induces apoptosis

in senescent cells; synergizes with palbociclib | GC | Reduces

SASP-mediated immunosuppression; enhances response to senescence

induction | (83) |

| Senescence

induction (FEN1-PBX1 inhibition) | Inhibits FEN1-PBX1

axis to trigger senescence via ROS accumulation | Breast cancer | Suppresses tumor

growth by activating p53/p21 pathways | (84) |

| LncRNA modulation

(NEAT1 knockdown) | Promotes KIF11

degradation, activating CDKN2A-mediated senescence | HCC | NEAT1 upregulation

is associated with senescence evasion; knockdown reduces tumor

progression | (85) |

| Senescence-related

gene targeting (EZH2 inhibition) | Reactivates CDKN2A

by reversing H3K27me3-mediated silencing | HCC | EZH2 inhibitors

reduce tumor growth and enhance immune infiltration | (86,87) |

| Combination therapy

(TRAF7 knockdown + lomustine) | TRAF7 knockdown

induces senescence; lomustine enhances senescent cell

clearance | Glioma | Reduces recurrence

by synergizing senescence induction with chemotherapy | (43) |

| Traditional Chinese

Medicine (Jianpi Huayu decoction) | Suppresses

senescence via p53-p21-Rb pathway | Colorectal

cancer | Inhibits tumor

growth by reducing SASP and stabilizing the TME | (83) |

Tumor-specific mechanisms underlying SASP

component heterogeneity

The heterogeneity of SASP components across cancer

types reflects tumor-specific signaling networks and interactions

within the TME, as exemplified by IL-6 and IL-8.

In breast cancer, IL-6 promotes metastasis through

context-dependent pathways. Preclinical evidence demonstrated that

IL-6 activates downstream cascades regulating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and matrix remodeling, both

key for metastatic dissemination. Consistently, IL-6-driven

signaling is associated with aggressive phenotypes in breast

cancer, where senescent cells secrete IL-6 to reinforce a

pro-metastatic niche.

In GC, IL-6 primarily reshapes immune landscapes

within the TME. Acting through chemokine networks such as chemokine

(C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)/C-C chemokine receptor 2, it recruits

MDSCs and CAFs, fostering immunosuppression and enabling immune

evasion (31,32). This divergence from breast cancer

partly reflects distinct IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) distribution, with

GC enriched for IL-6R on stromal and immune cells compared with

tumor cells.

IL-8 exhibits similarly context-dependent functions.

In lung adenocarcinoma, SASP-derived IL-8 underpins therapy

resistance by sustaining drug-tolerant cell survival via CXC

receptor 1/2 (R1/2) signaling, thereby maintaining tumor

persistence despite treatment (26,29).

By contrast, in colorectal cancer, IL-8 primarily drives

angiogenesis by stimulating vascular endothelial proliferation and

migration, which enhances tumor perfusion and growth.

These functional disparities arise from three

principal factors: i) Cell-type specificity of SASP receptor

expression (e.g., IL-6R on tumor vs. stromal cells); ii)

preferential activation of downstream pathways (e.g., EMT-related

cascades in breast cancer vs. immune-modulatory pathways in GC);

and iii) TME composition, which dictates whether SASP factors

engage tumor, immune or stromal compartments (15,33–36).

Collectively, these mechanisms highlight the need for

context-specific targeting of SASP components in cancer

therapy.

Targeting IL-6 illustrates the following principle:

Neutralizing IL-6 or blocking its downstream signaling (e.g.,

anti-IL-6 antibodies or STAT3 inhibitors) may suppress metastasis

in breast cancer, whereas in GC, such interventions may primarily

mitigate immunosuppression by reducing MDSC recruitment (37–43),

consistent with strategies outlined in Table I. Similarly, the divergent roles of

IL-8 underscore the therapeutic value of CXCR1/2 blockade in lung

adenocarcinoma to disrupt cancer stem cell maintenance and therapy

resistance, whereas in colorectal cancer, inhibiting IL-8-mediated

hypoxia inducible factor-1α upregulation could attenuate

angiogenesis. These approaches align with the SASP-modulating

therapies summarized in Table I,

emphasizing that therapeutic efficacy depends on matching

interventions to the dominant IL-8-driven pathway in each type of

cancer.

Relationship between cellular senescence and

the TME

Cellular senescence exerts profound,

context-dependent effects on the TME, which shapes cancer

progression through complex interactions. The accumulation of

senescent cells within the TME promotes tumor development by

secreting pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic factors collectively

known as the SASP (3,44,45).

SASP components remodel the ECM and establish a malignant niche by

driving cancer cell proliferation, invasion and immune evasion

(45,46). Furthermore, SASP factors recruit and

activate stromal cells, such as CAFs, further reinforcing a

tumor-permissive microenvironment (17,44,47).

Senescent immune cells also contribute to immune dysfunction by

disrupting metabolic balance (e.g., glucose competition) and

amplifying immunosuppressive signals (e.g., cAMP), thereby

facilitating immune escape (48).

Dual roles of senescent cells in the

TME

The influence of senescent cells within the TME is

highly dynamic. While SASP components can elicit antitumor

responses by enhancing immune surveillance and suppressing

angiogenesis in certain contexts (49,50),

specifically referring to four scenarios supported by preclinical

and clinical evidence: First, in premalignant lesions or

early-stage tumors, where senescent cells secrete immune-activating

SASP factors to trigger clearance of abnormal cells-for instance,

in HCC premalignancy, senescent hepatocytes release IL-24 to

recruit cytotoxic CD8+T cells for eliminating

premalignant cells (5,15,25–34).

Second, in cancer types with high immunogenicity, such as melanoma,

senescent cells express senescence-associated genes and secrete

pro-inflammatory SASP factors that promote CD8+ T-cell

infiltration, correlating with favorable patient prognosis

(37). Third, in the acute phase

after therapy-induced senescence, short-term SASP secretion from

acutely senescent tumor cells activates immunogenic cell death,

recruiting natural killer (NK) cells and dendritic cells to enhance

antitumor immunity (18,51). Fourth, in tissues rich in innate

immune cells, the tissue-specific TME amplifies the antitumor

effect of SASP-for example, senescent hepatic stellate cells in the

liver induce M1 macrophage polarization via SASP, inhibiting liver

fibrosis and early tumorigenesis (49). They more frequently drive tumor

progression through chronic inflammation, immunosuppression and

metastasis, as persistent senescence in advanced cancers leads to

accumulated immunosuppressive SASP components that recruit

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs), fostering immune evasion and metastatic

dissemination (30,31,36).

They more frequently drive tumor progression through chronic

inflammation, immunosuppression and metastasis (51). This paradox extends beyond oncology;

in neurodegenerative models, such as MAPTP301SPS19 mice, clearance

of senescent cells improves cognitive function (51). These observations highlight the

broad pathological impact of senescence and its potential as a

therapeutic target in cancer and aging-related diseases.

Therapeutic strategies targeting senescence

in the TME

Addressing these complexities requires therapeutic

strategies that precisely modulate senescent cells to enhance

antitumor effects while minimizing pro-tumorigenic consequences.

Senolytics (e.g., dasatinib and quercetin) represent a promising

approach, selectively eliminating harmful senescent cells to reduce

SASP-driven inflammation and restore treatment sensitivity

(52–57). Another strategy integrates

senotherapies with immunotherapy to reverse immune suppression in

the TME, thereby improving tumor recognition while counteracting

SASP-mediated resistance (58–63).

These approaches underscore the need for precision medicine,

tailoring treatment regimens to tumor-specific senescence

profiles.

Future research can elucidate mechanisms governing

senescence plasticity within the TME, identify biomarkers to

distinguish protective from pathogenic senescence and optimize

combinatorial strategies that harness antitumor benefits without

promoting malignancy. Emerging insights into senescence

reprogramming hold the potential to reshape cancer therapy by

disrupting tumor ecosystems and improving patient outcomes

(64).

Biomarkers and therapeutic targeting of

senescent cells in the TME

Biomarkers for identification and functional

analysis of senescent cells

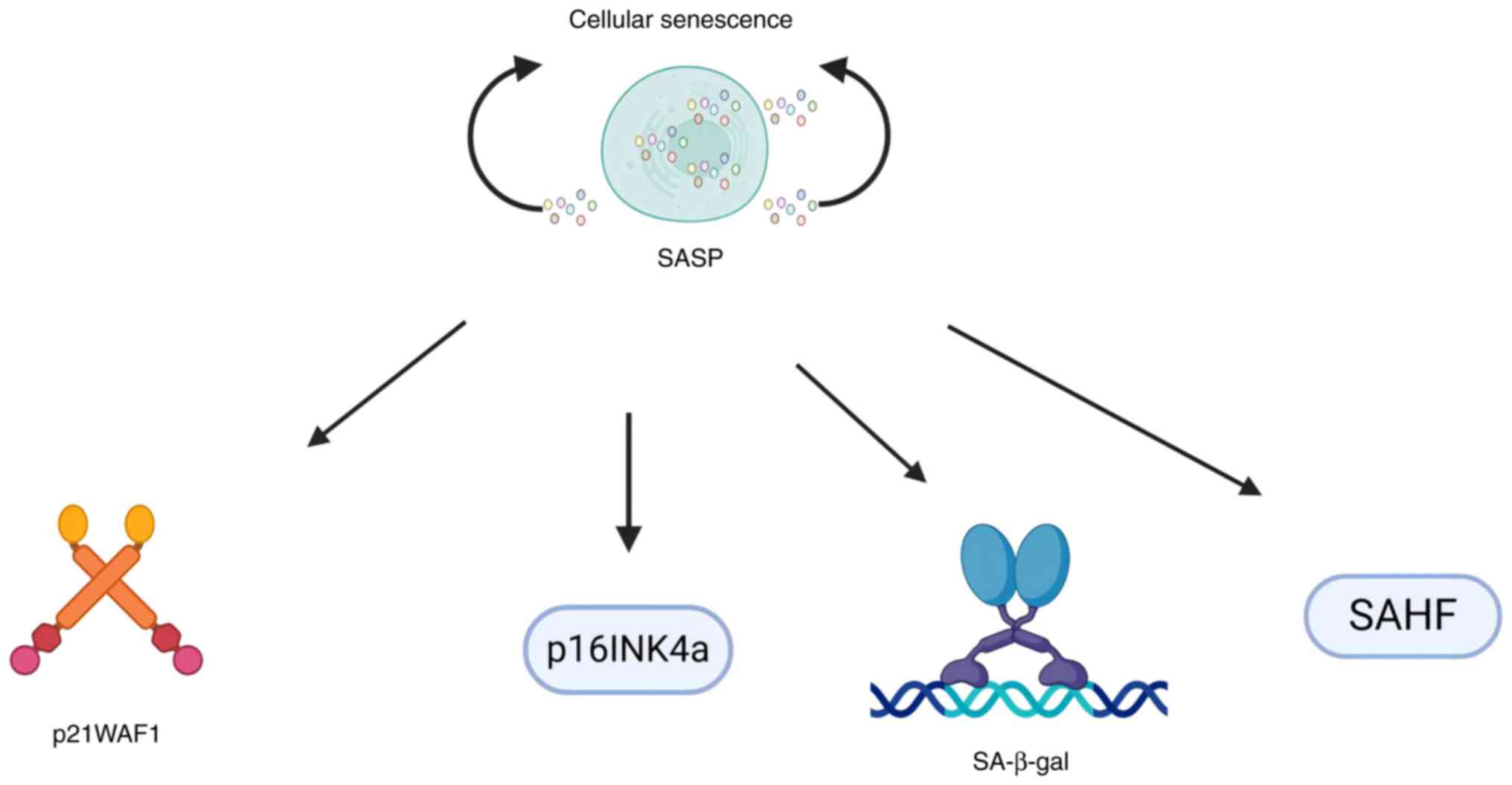

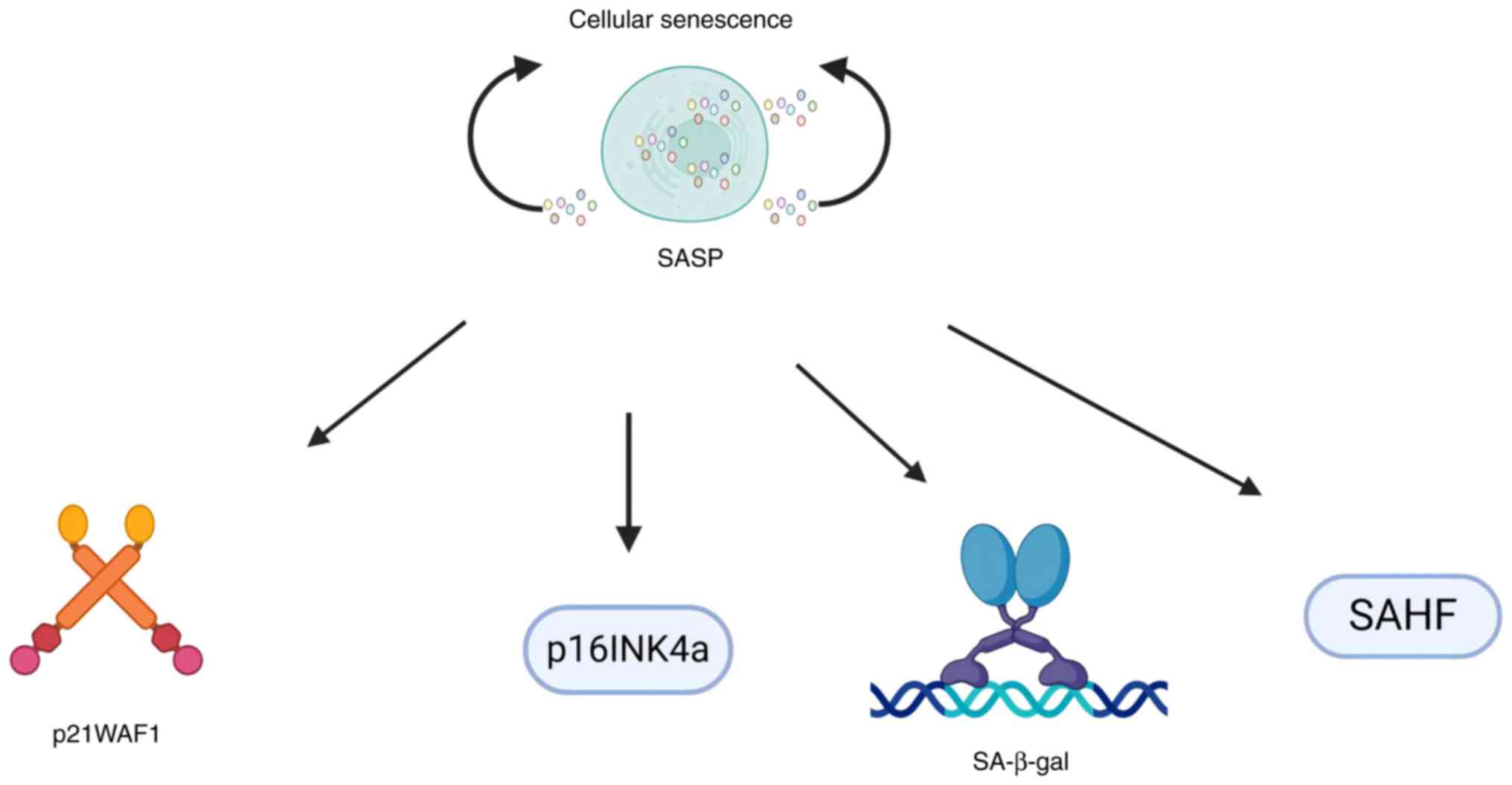

The identification and functional characterization

of senescent cells within the TME rely on robust biomarkers,

including cell cycle regulators [e.g., CDKN2A inhibitor (p16INK4a,

where INK4a denotes the p16 protein subtype) and p21 wild-type

p53-activated fragment 1 (p21WAF1, where WAF1 is the functional

alias of the p21 protein)], senescence-associated β-galactosidase

activity (SA-β-gal) and specific chromatin modifications such as

senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) (65,66).

These molecular signatures serve dual purposes: Enabling precise

tracking of senescent cell populations across spatial and temporal

scales and providing mechanistic insights into their roles in tumor

progression and therapeutic response (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis of these

biomarkers has become essential to evaluate the efficacy of

senolytic interventions and understanding the dynamic processes of

cellular senescence during cancer development (67–69)

(Fig. 3).

SASP and its dual roles

Central to the paradoxical effects of senescent

cells is the SASP, a complex repertoire of secreted

factors-including pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and

ECM-remodeling enzymes whose composition dictates tumor suppression

or promotion (64). In

glioblastoma, for instance, senescent malignant cells secrete high

levels of IL-6 and IL-8, which activate STAT3 signaling in

neighboring tumor cells, while MMP-9 released through SASP mediates

ECM degradation to facilitate tumor invasion (65–70).

This dynamic secretion profile, conserved in patient glioblastomas,

underscores how SASP components contribute to the aggressive

phenotype of certain cancers, aligning with the notion that

senescent cells exert context-dependent influences through their

secretory phenotype. While the SASP can initiate tumor-suppressive

responses, such as immune activation and inhibition of

angiogenesis, it frequently promotes tumor progression by

facilitating immune evasion and remodeling the surrounding

microenvironment (71). Epigenetic

regulation further modulates SASP activity, where chromatin

modifications can diminish tumor-suppressive functions of

senescence and instead support malignant progression.

Therapeutic strategies targeting senescent

cells and future directions

Therapeutic strategies have evolved to address the

complex biology of senescent cells through two complementary

approaches: i) Senolytic compounds selectively eliminate senescent

cells, thereby mitigating the deleterious effects of the

SASP-navitoclax achieves this by targeting BCL-xL in senescent

cells to induce apoptosis (68),

while fisetin preferentially clears senescent populations via

p53-dependent pathways (72),

consistent with broader senolytic mechanisms reported previously

(24,38,73–76);

and ii) senomorphic agents, by contrast, modulate specific SASP

components to suppress harmful effects while preserving beneficial

secretory functions-for example, compounds that inhibit NF-.κB or

restore mitochondrial function reduce pro-inflammatory SASP without

eliminating senescent cells, maintaining factors critical for

tissue repair (77). Combining

senolytics with immunotherapy holds promise, enhancing antitumor

immune responses by modulating key checkpoints and cytokine

networks.

Current research priorities include the

identification of predictive biomarkers for patient stratification,

optimization of senolytic treatment timing, preservation of

physiologically beneficial senescent populations and integration

with existing therapeutic modalities (28,76–78).

These efforts aim to establish precision senotherapy, tailoring

interventions based on comprehensive profiling of tumor-specific

senescence landscapes.

Emerging technologies such as single-cell

multi-omics and advanced computational modeling are expected to

provide further insights into the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of

tumor-associated senescent cells, enabling refined and personalized

treatment strategies that consider both neoplastic and

microenvironmental factors (77–80).

From a clinical perspective, senescence biomarkers

may serve as predictors of treatment responsiveness, while SASP

profiling can guide selection of senomorphic interventions.

Temporal optimization of senolytic administration and careful

consideration of the immune context are key for therapeutic

success. Collectively, these strategies highlight the importance of

mechanistic studies to elucidate adaptive responses of senescent

cell populations, with the ultimate goal of developing targeted

interventions that may potentially promote tumor suppression.

Biomarkers of senescent cells in the

TME

Identification and characterization of

senescent cells

The identification and characterization of senescent

cells within the TME rely on established biomarkers, including

upregulation of cell cycle inhibitors p21WAF1 and p16INK4a,

increased SA-β-gal activity and the formation of SAHF (65,66).

These markers not only enable the detection and monitoring of

senescent cells but also provide insights into their roles in

cancer progression and therapeutic response (Fig. 4). Quantitative assessment of these

biomarkers allows evaluation of the prevalence, spatial

distribution and functional impact of senescent cells within the

TME, which supports detailed studies on their contributions to

tumor biology and treatment resistance (67–69).

| Figure 4.Biomarkers of cellular senescence.

The schematic summarizes the key biomarkers used to identify and

monitor senescent cells, including cell cycle inhibitors (p16INK4a,

p21WAF1), SA-β-gal and SAHF. For consistency with the text, the

‘INK4a’ in p16INK4a and ‘WAF1’ in p21WAF1 in this figure correspond

to the gene subtype (INK4a) or protein alias (WAF1) described in

the main text, with the same functional meaning. The black arrows

in this figure visually connect senescent cells to their key

biomarkers, as detailed in the review: i) Arrows for intracellular

biomarkers point from senescent cells to cell cycle inhibitors,

SA-β-gal and SAHF. These markers reflect cell-autonomous senescence

features and are critical for ‘tracking senescent cell

populations’. ii) An arrow for the secretory biomarker SASP points

from senescent cells to SASP, highlighting its origin from

senescent cells and aligning with the document's definition of SASP

as a ‘dynamic secreted phenotype’ that also mediates TME

interactions. SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase

activity; SAHF, senescence-associated heterochromatin foci; SASP,

senescence-associated secretory phenotype. |

SASP and its dual roles

A hallmark of senescent cells is the SASP, a complex

and dynamic ensemble of secreted cytokines, chemokines and

matrix-remodeling proteases. SASP has complex, context-dependent

effects. Although SASP can activate antitumor immune responses, it

could promote tumorigenesis by altering the microenvironment and

impairing immune surveillance as well (70). Epigenetic regulation-such as histone

acetylation of SASP-related genes further modulates SASP activity,

which influences whether senescent cells function as tumor

suppressors or facilitators of malignancy. Epigenetic regulation

further modulates SASP activity, which influences whether senescent

cells function as tumor suppressors or facilitators of malignancy.

Dysregulation of tumor-suppressor pathways including p53-p21,

p16INK4a-Rb, PTEN-PI3K-AKT, p27Kip1 and TGF-β-Smad that often

undergo dysregulation, which disrupts their ability to regulate the

cell cycle and enforce senescence-induced growth arrest, ultimately

enabling cancer progression, which can bypass senescence-induced

growth arrest, enabling cancer progression (1,5,15,25,33,64).

Understanding these mechanisms is essential to develop therapies

that selectively mitigate pro-tumorigenic SASP functions while

preserving beneficial anticancer effects.

Therapeutic implications and future

directions

Recent advances in senotherapy have expanded

potential intervention strategies. Immune-based strategies

represent a breakthrough, with uPAR-targeted CAR-T cells

eliminating 67–90% of senescent cells in aged mouse tissues,

improving glucose tolerance and exercise capacity for over 12

months through specific recognition of the senescence marker uPAR

(80). For SASP modulation, JAK

inhibitor ruxolitinib and mTOR inhibitor rapamycin showed dual

efficacy in silencing pro-tumor inflammation while preserving

regenerative functions, validated in myelofibrosis trials and

preclinical studies on age-related pathologies (81). These advancements collectively

highlight the shift from single-agent senolysis to precision

strategies combining targeted delivery, immune engineering, and

SASP regulation, with clinical trials and guideline endorsements

solidifying their translational value. Senolytic drugs, such as

navitoclax and fisetin, selectively eliminate senescent cells,

thereby reducing SASP-mediated tumor promotion. Senomorphic agents,

by contrast, modulate SASP activity without inducing cell death,

providing refined control over downstream effects (19). The interplay between senescent cells

and immune regulation offers additional therapeutic opportunities.

The interplay between senescent cells and immune regulation offers

additional therapeutic opportunities specifically for enhancing

cancer treatment efficacy, such as reversing SASP-mediated

immunosuppression, developing senescence-targeted immunotherapies

and preventing therapy-induced recurrence by blocking

senescence-driven immune escape; these opportunities also extend to

alleviating age-related diseases by targeting their dysregulated

crosstalk. By shaping immune responses through secreted factors,

senescent cells can influence the efficacy of immunotherapies.

Combining senolytics with checkpoint inhibitors or adoptive cell

therapies may enhance antitumor immunity while counteracting

SASP-mediated immune evasion (13).

Future research aims to refine these strategies

using single-cell omics, spatial transcriptomics and artificial

intelligence (AI)-driven modeling to resolve the heterogeneity of

tumor-associated senescence. Identification of predictive

biomarkers will enable patient stratification, optimizing treatment

timing and combination regimens to maximize therapeutic benefit.

The ultimate goal is precision senotherapy, where interventions are

tailored to individual senescence profiles, harmonizing tumor

suppression with microenvironmental homeostasis. Such advances may

transform cancer care, moving from broadly cytotoxic treatments to

mechanism-driven, immune-compatible therapies that improve outcomes

while minimizing toxicity (82,83).

Emerging strategies exploit context-specific

senescence mechanisms, as summarized in Table I. These include targeting lncRNAs in

HCC or combining senescence induction with chemotherapy in glioma,

demonstrating how context-specific interventions can potentially

promote tumor suppression (36,84,85).

Clearance of senescent cells and tumor

treatment

Senescence as a tumor-suppressive mechanism

and pro-senescence therapy

Clinical evidence increasingly demonstrates that

chemotherapy-induced accumulation of senescent cells within tumors

is often associated with improved patient outcomes (86,87).

Preclinical studies corroborated these observations, which

demonstrates that defects in p53-dependent senescence pathways can

promote tumorigenesis and confer chemotherapy resistance (18,88,89).

These findings position cellular senescence as a natural

tumor-suppressive mechanism, notably restraining cancer

progression. The recent Food and Drug Administration approvals of

CDK4/6 inhibitors, including abemaciclib and palbociclib, which

possess senolytic properties, further support ‘pro-senescence

therapy’ as a viable anticancer strategy, particularly in breast

cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (90).

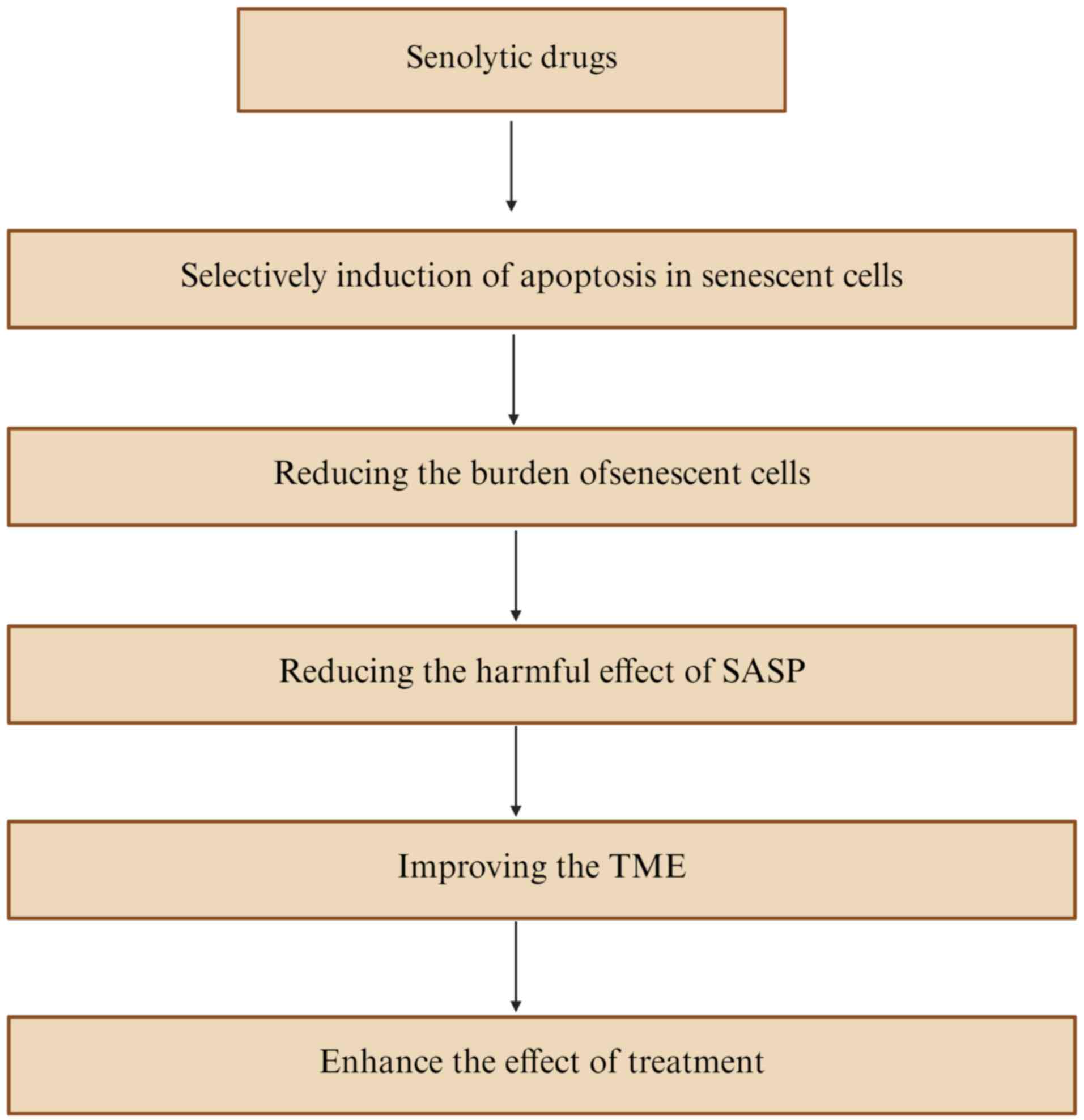

Senolytic therapy: Targeting senescent cells

to remodel the TME

Senolytic therapy, which selectively eliminates

senescent cells, is emerging as a promising strategy to remodel the

TME and enhance therapeutic efficacy (91,92).

By inducing apoptosis in senescent cells, senolytics such as

navitoclax and fisetin reduce their abundance, thereby mitigating

deleterious SASP effects including angiogenesis, invasion and

metastasis (93). This approach

addresses the accumulation of age-associated senescent cells, which

contributes to cancer susceptibility and represents a notable

advance in oncology (94,95). Depletion of senescent cells

suppresses pro-inflammatory and tumorigenic SASP factors, creating

a TME more conducive to effective anticancer therapies (96). Numerous preclinical compounds

including BH3 mimetics, PROTAC degraders, dual-mechanism small

molecules, and epigenetic modulators which exhibit potential by

selectively eliminating senescent cells, reversing SASP-mediated

immunosuppression, or synergizing with other therapies; as

mechanistic understanding of their targeting of

senescence-associated pathways increases, senescence-targeted

interventions are poised to become a central component of cancer

treatment.

However, the dual role of senescent cells

complicates therapeutic implementation. While their clearance can

counteract pro-tumorigenic effects, residual SASP factors may

persist and influence neighboring cells, potentially maintaining a

tumor-permissive environment (97).

Premature removal of senescent cells during specific treatment

phases such as the early stage after chemotherapy or radiotherapy,

when SASP still secretes antitumor factors to recruit cytotoxic

CD8+T cells could also disrupt SASP-mediated immune

responses that support antitumor activity (98); therefore, optimizing the timing and

context of senolytic interventions is key. Future studies can

refine senolytic mechanisms and elucidate dynamic crosstalk among

senescent cells, immune populations and stromal components within

the TME. Balancing senescence induction with selective elimination

will be essential to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing

tumor-promoting risks (99).

Addressing senescence-driven therapeutic resistance remains a key

challenge, which requires strategies to counteract immune evasion

and treatment failure (100)

(Fig. 5).

Combining senolytics with immunotherapy and

emerging therapeutic strategies

SASP-mediated immunosuppression enables tumor cells

to evade immune surveillance and resist therapy (101), highlighting the potential of

combining senolytics with immunotherapy, particularly immune

checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-1 blockers, PD-L1 inhibitors,

CTLA-4 antibodies and novel LAG-3 inhibitors. Such combinations can

concurrently eliminate immunosuppressive senescent cells and

enhance antitumor immunity, potentially overcoming SASP-mediated

therapy resistance (102).

Targeting specific SASP factors, including IL-6 and TGF-β, may

further reprogram the TME from immunosuppressive to immune-active,

opening opportunities for synergy with adoptive cell therapies or

cancer vaccines (103).

Implementing these strategies requires a precision

medicine framework, incorporating biomarker-driven patient

stratification to identify optimal candidates for

senolytic-immunotherapy combinations. Advanced approaches, such as

single-cell profiling and AI-based predictive modeling, can help

resolve tumor-associated senescence heterogeneity and guide

personalized regimens (104).

Translating these innovations will necessitate multidisciplinary

collaboration among oncologists, immunologists and computational

biologists to ensure safe and effective application across diverse

patient populations.

The dualistic nature of senescent cells, both

restraining and promoting cancer, presents a complex yet promising

therapeutic frontier. While pro-senescence therapies can inhibit

tumor growth, senolytic strategies offer a means to counterbalance

their detrimental effects. Optimizing combination approaches that

integrate senescence modulation with immunotherapy, chemotherapy

and targeted agents will be pivotal specifically for balancing the

tumor-suppressive and pro-tumorigenic effects of senescence,

overcoming therapy-induced senescence-related resistance,

remodeling the immunosuppressive TME which can reduce MDSC

recruitment via IL-6 inhibition and reinvigorating CD8+T cells with

PD-1 blockers in HCC, enabling precision senotherapy tailored to

cancer heterogeneity and minimizing treatment toxicity. By

systematically dissecting the role of senescence in cancer,

next-generation therapies can exploit its protective mechanisms

while neutralizing pro-tumorigenic potential, ultimately improving

survival and quality of life for patients.

Beyond established senolytics such as dasatinib and

quercetin, emerging agents such as exisulind have demonstrated

efficacy in GC by inducing apoptosis in senescent cells and

synergizing with palbociclib to enhance senescence clearance

(83). In breast cancer, inhibition

of the flap endonuclease 1-pre-B cell leukemia factor 1 axis

triggers senescence via reactive oxygen species accumulation and

activation of p53/p21 pathways, which suppresses tumor growth

(84). These findings support the

expansion of senolytic and senescence-inducing strategies beyond

conventional regimens.

Dual nature of senescent cells in tumor

immune evasion and therapeutic opportunities

Paradoxical roles of senescence and SASP in

tumor immunity

Cellular senescence exerts a key yet paradoxical

influence in cancer, simultaneously constraining tumor initiation

while promoting immune evasion and therapy resistance. The SASP is

central to this duality, comprising a complex mixture of

inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α), chemokines (e.g.,

CCL2 and CXCL12) and proteases that notably shape the TME (105,106). Initially, SASP factors recruit

immune effector cells; however, chronic SASP activity drives

immunosuppression through multiple mechanisms: Polarizing

macrophages toward tumor-promoting M2 phenotypes (107), recruiting Tregs (107,108) and inducing T-cell dysfunction via

p16INK4a-mediated senescence (108). Therefore, a permissive niche is

established, enabling malignant cells to evade immune surveillance

despite the tumor-suppressive growth arrest in senescent cells.

Oncogene-induced senescence and

context-dependent tumorigenesis

The interplay between senescence and tumorigenesis

is particularly evident in oncogene-induced senescence. Activation

of oncogenes such as human Ras oncogene G12V, HER2, EGFR and PI3K

triggers senescence as an intrinsic tumor-suppressive response

(109), yet concurrent SASP

secretion undermines this protection by promoting immunosuppression

and remodeling tissue architecture. Conversely, oncogene

inactivation (e.g., Myc) can induce senescence and tumor regression

across various cancer types (110), like lymphoma, HCC, triple-negative

breast cancer, highlighting the context-dependent nature of these

processes. Senescent cells disrupt normal tissue structure and

suppress antitumor immunity via their secretory profile, thereby

facilitating immune evasion and disease progression (28).

Therapeutic strategies targeting senescence

and SASP in cancer

This biological paradox presents both challenges and

opportunities for intervention. While senescence induction halts

tumor growth, SASP activity may drive therapeutic resistance and

immune escape (111). Current

strategies focus on three complementary approaches: i) Senolytic

agents that selectively eliminate senescent cells to abrogate

pro-tumorigenic effects; ii) SASP-modulating therapies that inhibit

deleterious factors while preserving beneficial functions; and iii)

rational combinations with immunotherapy to overcome SASP-mediated

immunosuppression (112). Research

suggests that precisely timed senolytic interventions can enhance

immune checkpoint blockades by remodeling the TME and

reinvigorating antitumor T-cell responses (3,113).

These findings align with the document's emphasis on temporal

precision in senolytic-immunotherapy combinations to avoid

late-stage immunosuppressive SASP while preserving early IFN-driven

antitumor immunity (5,93) (Table

II).

| Table II.Therapeutic approaches and

challenges. |

Table II.

Therapeutic approaches and

challenges.

| Therapeutic

approach | Mechanism | Potential

benefit | Challenges |

|---|

| Senolytic

therapy | Selective

elimination of senescent cells | Reduces

SASP-mediated immunosuppression | May disrupt

tumor-suppressive senescence |

| SASP

modulation | Targeted cytokine

inhibition (e.g., IL-6 blockade) | Preserves

senescence arrest while blocking harmful secretions | Complex cytokine

network redundancy |

| Combination

immunotherapy | Senolytics +

checkpoint inhibitors | Enhances T cell

reinvigoration | Timing/dosing

optimization required |

Future cancer therapies are likely to integrate

advanced approaches leveraging the current growing understanding of

senescence biology. These include biomarker-driven patient

stratification, temporally controlled senolytic delivery and

senomorphic agents designed to reprogram rather than eliminate

senescent cells (113). By

simultaneously targeting malignant cells and reshaping the

immunosuppressive microenvironment, such strategies have the

potential to overcome treatment limitations, reduce recurrence and

improve long-term outcomes.

Tumor-specific immune modulation by SASP illustrates

the need for personalized approaches. In melanoma,

senescence-associated gene expression is associated with increased

CD8+ T-cell infiltration (36), whereas in HCC, high senescence

scores are associated with immunosuppressive SASP and poor

prognosis (38,39). Targeted interventions, such as

enhancer of zeste homolog 2 inhibition to reactivate CDKN2A and

enhance immune infiltration (85,86) or

lncRNA NEAT1 knockdown to restore senescence (84), exemplify strategies to exploit

senescence biology for precision oncology.

Interplay between senescent cells and

telomerase pathways in cancer

Telomerase reactivation and senescence

escape in tumor cells

Cellular senescence and telomerase activity are

closely intertwined in cancer development and progression.

Telomerase, which preserves telomere length, is largely inactive in

normal somatic cells but reactivated in ~85–90% of human cancer

types, enabling tumor cells to bypass replicative senescence and

sustain ‘immortal’ proliferation (114). This observation supports the

telomerase theory of cancer, in which telomerase activation is

regarded as a near-universal hallmark of malignancy (115). Nevertheless, notable molecular

distinctions exist between replicative senescence in normal cells,

mediated by p53/p16-dependent G0/G1 arrest

and telomere shortening, and senescence-like arrest in cancer

cells, which frequently occurs independently of telomere attrition

(116–118).

Therapeutic targeting of telomerase and

challenges of alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT)

pathway

Targeting telomerase represents a promising

anticancer strategy. Natural compounds, including icaritin (from

Epimedium) and wogonin (from Scutellaria

baicalensis), have demonstrated potent telomerase inhibition in

leukemia (HL-60) and ovarian cancer (SKOV3) models, respectively

(119–121). These agents selectively induce

cytotoxicity in telomerase-positive tumors while sparing normal

tissues. Clinical translation, however, requires optimization of

pharmacokinetics and development of effective combination regimens

(Table III).

| Table III.Natural compounds targeting

telomerase. |

Table III.

Natural compounds targeting

telomerase.

| Compound | Source | Target cancer (cell

line) | Key findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Icaritin | Epimedium

extract | Leukemia

(HL-60) | Notable telomerase

suppression | (120) |

| Wogonin | Scutellaria

baicalensis | Ovarian

(SKOV3) | Dose-dependent

inhibition in vitro/in vivo | (121) |

Certain cancer types (10–15%) evade telomerase

dependency by employing the ALT pathway, which maintains telomere

length via homologous recombination rather than telomerase. ALT is

particularly prevalent in osteosarcomas (~60%) and glioblastomas

(~40%), which poses a notable therapeutic challenge due to

resistance to conventional telomerase-targeted drugs, e.g.

olaparib, RAD51 inhibitor, telomere homologous recombination

inhibitor with oxadiazole scaffold, tazemetostat (122,123). Emerging strategies to overcome

ALT-mediated resistance include ataxia telangiectasia and

Rad3-related inhibitors, CRISPR-based disruption of ALT machinery

and synthetic lethality approaches that exploit ALT-specific

vulnerabilities (124).

Future perspectives: Integrating telomere

biology with senescence-targeted therapies

Future directions emphasize patient stratification

according to telomere maintenance mechanisms and the development of

combination therapies that integrate telomerase inhibitors with

immunotherapy or epigenetic modulators. The creation of novel

diagnostic tools will be key for real-time monitoring of telomerase

activity. The crosstalk between senescence and telomere dynamics

constitutes a pivotal frontier in cancer therapy, offering

opportunities to enhance treatment efficacy, prevent relapse and

overcome resistance in both telomerase-dependent and ALT-driven

malignancies. By combining telomerase inhibition with senolytic

strategies, it may be possible to simultaneously disrupt tumor cell

immortality and remodel the immunosuppressive TME, establishing

innovative therapeutic paradigms.

Conclusions

The present review highlights the central role of

cellular senescence in cancer, emphasizing its paradoxical function

as both a tumor-suppressive mechanism and a promoter of malignancy.

The intricate interplay between senescent cells and the TME,

largely mediated through SASP, presents novel avenues for

therapeutic intervention. Future research can prioritize the

elucidation of tumor-specific variations in SASP composition and

their distinct contributions to cancer progression. The development

of next-generation senotherapeutics, including innovative

senolytics and senomorphics, holds notable promise in selectively

targeting deleterious senescent cells while preserving their

protective functions.

Integrating Traditional Chinese Medicine with

contemporary therapeutic strategies offers additional opportunities

to enhance senescence modulation, advancing the field towards

precision oncology. Cutting-edge technologies, such as single-cell

omics, spatial transcriptomics and AI-driven modeling, are

essential to dissect the spatiotemporal dynamics of senescent cells

within the TME. Furthermore, novel approaches, including

SASP-specific inhibitors and senescent cell vaccines, may provide

targeted solutions to the complex interactions between senescence

and tumorigenesis.

Clinical translation will require robust biomarkers

for patient stratification and carefully designed trials,

particularly for aging populations and refractory types of cancer.

Future research can focus on balancing the protective functions of

senescence, such as clearance of damaged cells, against potential

detrimental effects, including chronic inflammation and immune

suppression. Optimizing the timing and context of senolytic

interventions is key to maximizing therapeutic benefit while

minimizing adverse effects. Strategically targeting pathological

senescence thus represents a transformative approach in oncology,

which offers personalized, effective therapies that simultaneously

disrupt tumor cell immortality and remodel the immunosuppressive

TME.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was funded by Shanghai Putuo District Health

System Science and Technology Innovation Project (grant no.

ptkwws202507).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YL conceptualized the present review, validated the

data and conducted the formal analysis, wrote the original draft,

and edited and reviewed the manuscript. JG collected, screened and

systematically organized key data from relevant literature and

existing studies, wrote the original draft, and edited and reviewed

the manuscript. PY conceptualized the present review, validated the

data, obtained funding, and edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Campisi J and d'Adda di Fagagna F:

Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 8:729–740. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schosserer M, Grillari J and Breitenbach

M: The dual role of cellular senescence in developing tumors and

their response to cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 7:2782017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nacarelli T, Liu P and Zhang R: Epigenetic

basis of cellular senescence and its implications in aging. Genes

(Basel). 8:3432017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lai P, Liu L, Bancaro N, Troiani M, Calì

B, Li Y, Chen J, Singh PK, Arzola RA, Attanasio G, et al:

Mitochondrial DNA released by senescent tumor cells enhances

PMN-MDSC-driven immunosuppression through the cGAS-STING pathway.

Immunity. 58:811–825.e7. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen D, Wang J, Li Y, Xu C, Fanzheng M,

Zhang P and Liu L: LncRNA NEAT1 suppresses cellular senescence in

hepatocellular carcinoma via KIF11-dependent repression of CDKN2A.

Clin Transl Med. 13:e14182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu N, Wu J, Deng E, Zhong J, Wei B, Cai

T, Xie Z, Duan X, Fu S, Osei-Hwedieh DO, et al: Immunotherapy and

senolytics in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Phase 2 trial

results. Nat Med. 31:3047–3061. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zandi M, Behboudi E, Shojaei MR, Soltani S

and Karami H: Letter to the editor regarding ‘An overview on

serology and molecular tests for COVID-19: An important challenge

of the current century (doi: 10.22034/iji.2021.88660.1894.)’. Iran

J Immunol. 19:3372022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Khosravi M, Behboudi E, Razavi-Nikoo H and

Tabarraei A: Hepatitis B virus X protein induces expression changes

of miR-21, miR-22, miR-122, miR-132, and miR-222 in Huh-7 cell

line. Arch Razi Inst. 79:111–119. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Edalat F, Gholamzad A, Ghoreshi ZA,

Dalfardi M, Golkar A, Behboudi E and Arefinia N: Prevalence and

genetic diversity of HTLV-1 among blood donors in Jiroft, Iran: A

comprehensive study. Virus Genes. 61:424–431. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, Stultz TW,

Procop GW, Mirkin G and Vidimos AT: Dermatofibrosarcoma

protuberans: Update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med.

9:17522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Molina-Peña R, Tudon-Martinez JC and

Aquines-Gutiérrez O: A mathematical model of average dynamics in a

stem cell hierarchy suggests the combinatorial targeting of cancer

stem cells and progenitor cells as a potential strategy against

tumor growth. Cancers (Basel). 12:25902020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xu L, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhai J, Ren L and

Zhu G: Radiation-induced osteocyte senescence alters bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cell differentiation potential via paracrine

signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 22:93232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, Campisi

J and van Deursen JM: Senescence and apoptosis: Dueling or

complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep. 15:1139–1153. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rhinn M, Ritschka B and Keyes WM: Cellular

senescence in development, regeneration and disease. Development.

146:dev1518372019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gorgoulis V, Adams PD, Alimonti A, Bennett

DC, Bischof O, Bishop C, Campisi J, Collado M, Evangelou K,

Ferbeyre G, et al: Cellular senescence: Defining a path forward.

Cell. 179:813–827. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Olivieri F, Prattichizzo F, Grillari J and

Balistreri CR: Cellular senescence and inflammaging in Age-related

diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2018:90764852018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Di Micco R, Krizhanovsky V, Baker D and

d'Adda di Fagagna F: Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms

to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:75–95.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mikuła-Pietrasik J, Niklas A, Uruski P,

Tykarski A and Książek K: Mechanisms and significance of

therapy-induced and spontaneous senescence of cancer cells. Cell

Mol Life Sci. 77:213–229. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ou HL, Hoffmann R, González-López C,

Doherty GJ, Korkola JE and Muñoz-Espín D: Cellular senescence in

cancer: From mechanisms to detection. Mol Oncol. 15:2634–2671.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Di Mitri D and Alimonti A:

Non-Cell-Autonomous regulation of cellular senescence in cancer.

Trends Cell Biol. 26:215–226. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Park SS, Choi YW, Kim JH, Kim HS and Park

TJ: Senescent tumor cells: An overlooked adversary in the battle

against cancer. Exp Mol Med. 53:1834–1841. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Saleh T, Tyutynuk-Massey L, Cudjoe EK Jr,

Idowu MO, Landry JW and Gewirtz DA: Non-cell autonomous effects of

the Senescence-associated secretory phenotype in cancer therapy.

Front Oncol. 8:1642018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Herranz N and Gil J: Mechanisms and

functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest. 128:1238–1246.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rao SG and Jackson JG: SASP: Tumor

suppressor or promoter? Yes! Trends Cancer. 2:676–687. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

He Y, Long K, Du B, Liao W, Zou R, Su J,

Luo J, Shi Z and Wang L: The cellular senescence score (CSS) is a

comprehensive biomarker to predict prognosis and assess senescence

and immune characteristics in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 739:1505762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ru K, Cui L, Wu C, Tan XX, An WT, Wu Q, Ma

YT, Hao Y, Xiao X, Bai J, et al: Exploring the molecular and immune

landscape of cellular senescence in lung adenocarcinoma. Front

Immunol. 15:13477702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Geng H, Huang C, Xu L, Zhou Y, Dong Z,

Zhong Y, Li Q, Yang C, Huang S, Liao W, et al: Targeting cellular

senescence as a therapeutic vulnerability in gastric cancer. Life

Sci. 346:1226320241

|

|

28

|

Liu H, Zhao H and Sun Y: Tumor

microenvironment and cellular senescence: Understanding therapeutic

resistance and harnessing strategies. Semin Cancer Biol.

86:769–781. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Higashiguchi M, Murakami H, Akita H,

Kobayashi S, Takahama S, Iwagami Y, Yamada D, Tomimaru Y, Noda T,

Gotoh K, et al: The impact of cellular senescence and

senescence-associated secretory phenotype in cancer-associated

fibroblasts on the malignancy of pancreatic cancer. Oncol Rep.

49:982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu H, Lv R, Song F, Yang Y, Zhang F, Xin

L, Zhang P, Zhang Q and Ding C: A near-IR ratiometric fluorescent

probe for the precise tracking of senescence: A multidimensional

sensing assay of biomarkers in cell senescence pathways. Chem Sci.

15:5681–5693. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lin W, Wang X, Wang Z, Shao F, Yang Y, Cao

Z, Feng X, Gao Y and He J: Comprehensive analysis uncovers

prognostic and immunogenic characteristics of cellular senescence

for lung adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7804612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang W, Li Y, Lyu J, Shi F, Kong Y, Sheng

C, Wang S and Wang Q: An aging-related signature predicts favorable

outcome and immunogenicity in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci.

113:891–903. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pérez-Mancera PA, Young AR and Narita M:

Inside and out: The activities of senescence in cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 14:547–558. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang Y, Cai Q, Zhu M, Rong J, Feng X and

Wang K: Exploring the Double-edged role of cellular senescence in

chronic liver disease for new treatment approaches. Life Sci.

373:1236782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wyld L, Bellantuono I, Tchkonia T, Morgan

J, Turner O, Foss F, George J, Danson S and Kirkland JL: Senescence

and cancer: A review of clinical implications of senescence and

senotherapies. Cancers (Basel). 12:21342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gu Y, Xu T, Fang Y, Shao J, Hu T, Wu X,

Shen H, Xu Y, Zhang J, Song Y, et al: CBX4 counteracts cellular

senescence to desensitize gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy by

inducing YAP1 SUMOylation. Drug Resist Updat. 77:1011362024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Liang X, Lin X, Lin Z, Lin W, Peng Z and

Wei S: Genes associated with cellular senescence favor melanoma

prognosis by stimulating immune responses in tumor

microenvironment. Comput Biol Med. 158:1068502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhao Q, Hu W, Xu J, Zeng S, Xi X, Chen J,

Wu X, Hu S and Zhong T: Comprehensive Pan-cancer analysis of

senescence with cancer prognosis and immunotherapy. Front Mol

Biosci. 9:9192742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Fan Y, Gao Z, Li X, Wei S and Yuan K: Gene

expression and prognosis of x-ray repair cross-complementing family

members in non-small cell lung cancer. Bioengineered. 12:6210–6228.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mavrogonatou E, Pratsinis H and Kletsas D:

The role of senescence in cancer development. Semin Cancer Biol.

62:182–191. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu H, Xu Q, Wufuer H, Li Z, Sun R, Jiang

Z, Dou X, Fu Q, Campisi J and Sun Y: Rutin is a potent senomorphic

agent to target senescent cells and can improve chemotherapeutic

efficacy. Aging Cell. 23:e139212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sun Y, Coppé JP and Lam EW: Cellular

senescence: The sought or the unwanted? Trends Mol Med. 24:871–885.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen Y, Zhou T, Zhou R, Sun W, Li Y, Zhou

Q, Xu D, Zhao Y, Hu P, Liang J, et al: TRAF7 knockdown induces

cellular senescence and synergizes with lomustine to inhibit glioma

progression and recurrence. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 44:1122025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Calcinotto A, Kohli J, Zagato E,

Pellegrini L, Demaria M and Alimonti A: Cellular senescence: Aging,

cancer, and injury. Physiol Rev. 99:1047–1078. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kamal M, Shanmuganathan M, Kroezen Z,

Joanisse S, Britz-McKibbin P and Parise G: Senescent myoblasts

exhibit an altered exometabolome that is linked to

senescence-associated secretory phenotype signaling. Am J Physiol

Cell Physiol. 328:C440–C451. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lecot P, Alimirah F, Desprez PY, Campisi J

and Wiley C: Context-dependent effects of cellular senescence in

cancer development. Br J Cancer. 114:1180–1184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lian J, Yue Y, Yu W and Zhang Y:

Immunosenescence: A key player in cancer development. J Hematol

Oncol. 13:1512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ruhland MK and Alspach E: Senescence and

immunoregulation in the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:7540692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lau L and David G: Pro- and

anti-tumorigenic functions of the senescence-associated secretory

phenotype. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 23:1041–1051. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gonzalez-Meljem JM, Apps JR, Fraser HC and

Martinez-Barbera JP: Paracrine roles of cellular senescence in

promoting tumourigenesis. Br J Cancer. 118:1283–1288. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang G, Cheng X, Zhang J, Liao Y, Jia Y

and Qing C: Possibility of inducing tumor cell senescence during

therapy. Oncol Lett. 22:4962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Maggiorani D, Le O, Lisi V, Landais S,

Moquin-Beaudry G, Lavallée VP, Decaluwe H and Beauséjour C:

Senescence drives immunotherapy resistance by inducing an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Nat Commun. 15:24352024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lasry A and Ben-Neriah Y:

Senescence-associated inflammatory responses: Aging and cancer

perspectives. Trends Immunol. 36:217–228. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Murray KO, Mahoney SA, Ludwig KR,

Miyamoto-Ditmon JH, VanDongen NS, Banskota N, Herman AB, Seals DR,

Mankowski RT, Rossman MJ and Clayton ZS: Intermittent

supplementation with fisetin improves physical function and

decreases cellular senescence in skeletal muscle with aging: A

comparison to genetic clearance of senescent cells and synthetic

senolytic approaches. Aging Cell. 24:e701142025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ayoub M, Abou Jaoude C, Ayoub M, Hamade A

and Rima M: The immune system and cellular senescence: A complex

interplay in aging and disease. Immunology. Sep 12–2025.doi:

10.1111/imm.70036 (Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang W, Zhang K, Shi J, Qiu H, Kan C, Ma

Y, Hou N, Han F and Sun X: The impact of the senescent

microenvironment on tumorigenesis: Insights for cancer therapy.

Aging Cell. 23:e141822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kirkland JL: Tumor dormancy and disease

recurrence. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 42:9–12. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

de Paula B, Kieran R, Koh SSY, Crocamo S,

Abdelhay E and Muñoz-Espín D: Targeting senescence as a therapeutic

opportunity for Triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther.

22:583–598. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Lee S and Lee JS: Cellular senescence: A

promising strategy for cancer therapy. BMB Rep. 52:35–41. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wang C, Hao X and Zhang R: Targeting

cellular senescence to combat cancer and ageing. Mol Oncol.

16:3319–3332. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Battram AM, Bachiller M and Martín-Antonio

B: Senescence in the development and response to cancer with

immunotherapy: A Double-edged sword. Int J Mol Sci. 21:43462020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Fan DN and Schmitt CA: Detecting markers

of Therapy-induced senescence in cancer cells. Methods Mol Biol.

1534:41–52. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ruhland MK, Coussens LM and Stewart SA:

Senescence and cancer: An evolving inflammatory paradox. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1865:14–22. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Song S, Lam EW, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL

and Sun Y: Senescent cells: Emerging targets for human aging and

Age-related diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 45:578–592. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Paleari L: Personalized assessment for

cancer prevention, detection, and treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

25:81402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ohtani N: The roles and mechanisms of

senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): Can it be

controlled by senolysis? Inflamm Regen. 42:112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kaur J and Farr JN: Cellular senescence in

Age-related disorders. Transl Res. 226:96–104. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Hughes BK, Davis A, Milligan D, Wallis R,

Mossa F, Philpott MP, Wainwright LJ, Gunn DA and Bishop CL:

SenPred: A single-cell RNA sequencing-based machine learning

pipeline to classify deeply senescent dermal fibroblast cells for

the detection of an in vivo senescent cell burden. Genome Med.

17:22025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Uyar B, Palmer D, Kowald A, Murua Escobar

H, Barrantes I, Möller S, Akalin A and Fuellen G: Single-cell

analyses of aging, inflammation and senescence. Ageing Res Rev.

64:1011562020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Sprenger HG, MacVicar T, Bahat A, Fiedler

KU, Hermans S, Ehrentraut D, Ried K, Milenkovic D, Bonekamp N,

Larsson NG, et al: Cellular pyrimidine imbalance triggers

mitochondrial DNA-dependent innate immunity. Nat Metab. 3:636–650.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liang A, Kong Y, Chen Z, Qiu Y, Wu Y, Zhu

X and Li Z: Advancements and applications of single-cell

multi-omics techniques in cancer research: Unveiling heterogeneity

and paving the way for precision therapeutics. Biochem Biophys Rep.

37:1015892023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Avelar RA, Ortega JG, Tacutu R, Tyler EJ,

Bennett D, Binetti P, Budovsky A, Chatsirisupachai K, Johnson E,

Murray A, et al: A multidimensional systems biology analysis of

cellular senescence in aging and disease. Genome Biol. 21:912020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wu L, Xie X, Liang T, Ma J, Yang L, Yang

J, Li L, Xi Y, Li H, Zhang J, et al: Integrated Multi-omics for

novel aging biomarkers and antiaging targets. Biomolecules.

12:392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Aird KM and Zhang R: Nucleotide

metabolism, oncogene-induced senescence and cancer. Cancer Lett.

356:204–210. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Yang K, Li X and Xie K: Senescence program

and its reprogramming in pancreatic premalignancy. Cell Death Dis.

14:5282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hwang HJ, Jung SH, Lee HC, Han NK, Bae IH,

Lee M, Han YH, Kang YS, Lee SJ, Park HJ, et al: Identification of

novel therapeutic targets in the secretome of ionizing

radiation-induced senescent tumor cells. Oncol Rep. 35:841–850.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Matjusaitis M, Chin G, Sarnoski EA and

Stolzing A: Biomarkers to identify and isolate senescent cells.

Ageing Res Rev. 29:1–12. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ziglari T, Calistri NL, Finan JM, Derrick

DS, Nakayasu ES, Burnet MC, Kyle JE, Hoare M, Heiser LM and Pucci

F: Senescent Cell-derived extracellular vesicles inhibit cancer

recurrence by coordinating immune surveillance. Cancer Res.

85:859–874. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Davalli P, Mitic T, Caporali A, Lauriola A

and D'Arca D: ROS, cell senescence, and novel molecular mechanisms

in aging and Age-related diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:35651272016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Amor C, Fernández-Maestre I, Chowdhury S,

Ho YJ, Nadella S, Graham C, Carrasco SE, Nnuji-John E, Feucht J,

Hinterleitner C, et al: Prophylactic and Long-lasting efficacy of

senolytic CAR T cells against Age-related metabolic dysfunction.

Nat Aging. 4:336–349. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Alqahtani S, Alqahtani T, Venkatesan K,

Sivadasan D, Ahmed R, Sirag N, Elfadil H, Abdullah Mohamed H, T A

H, Elsayed Ahmed R, et al: SASP modulation for cellular

rejuvenation and tissue homeostasis: Therapeutic strategies and

molecular insights. Cells. 14:6082025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Lee S,

Baranov E, Hoffman RM and Lowe SW: A senescence program controlled