Metabolic reprogramming is a fundamental

characteristic of cancer development and progression (1), and it is primarily marked by a notable

increase in aerobic glycolysis (2).

This atypical activation of aerobic glycolysis not only meets the

energy and biosynthetic demands of rapidly proliferating malignant

tumor cells but also contributes to the formation of a hypoxic,

acidic and nutrient-deprived tumor microenvironment (TME). Such an

environment facilitates tumor immune evasion and presents a notable

challenge to the antitumor immune response (3,4).

Hexokinase 2 (HK2), the initial and critical rate-limiting enzyme

in glycolysis, is markedly upregulated in various solid tumors

[such as colorectal cancer (5),

triple-negative breast cancer (6),

hepatocellular carcinoma (7),

pancreatic cancer (8), esophageal

cancer (9), etc.], where it serves

a pivotal role in catalyzing glycolytic processes and influencing

the malignant behavior of tumors; it is also closely related to

poor patient prognosis (10–18).

The regulatory function of HK2 in immune evasion has increasingly

attracted attention for research (3,19–21).

Previous research indicates that the functions of HK2 encompass

multiple immune escape mechanisms (3,20,22).

The expression and post-translational modification of HK2 are

modulated by a variety of signal transduction pathways and

oncogenic factors, which further facilitate immune evasion through

both glycolysis-dependent and independent mechanisms. These

mechanisms impact immune cell distribution (23), modulate the expression of immune

checkpoint molecules (20) and

contribute to the establishment of an immunosuppressive

microenvironment (3). Furthermore,

HK2-mediated hyperactive glycolysis in tumor cells competes with

immune cells for glucose, induces metabolic reprogramming in immune

cells, suppresses the activation and function of immune cells, and

releases large quantities of metabolites to establish an

immunosuppressive niche, thereby impairing immune molecule

expression and further weakening the antitumor immune response

(24,25). Although small-molecule inhibitors

[such as 3-bromopyruvic acid (26)

and lonidamine (27)] and

gene-editing tools that target HK2 can reverse metabolism-dependent

immunosuppression, their clinical application is constrained by

off-target toxicity, compensatory metabolism and delivery

efficiency (21,28–30).

Emerging strategies focusing on subcellular localization and

non-catalytic intervention may offer novel directions to overcome

these clinical translation bottlenecks (3).

At present, an expanding body of research has

substantiated the multifaceted role of HK2 in bridging tumor

metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion; however, comprehensive

analyses remain limited. In light of this, the present review aims

to summarize the research advancements regarding the regulation of

immune escape in malignant tumors by HK2 and the role of HK2 in

metabolic-immune interactions, with the objective of providing

references and theoretical underpinnings for the development of

novel immunotherapeutic strategies.

HK serves as the rate-limiting enzyme that initiates

the glycolytic pathway by catalyzing the phosphorylation of glucose

to glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P), thereby facilitating energy

production and biosynthesis (31).

In mammals, five isoforms of HK have been identified, HK1-4 and HK

domain-containing 1, with HK2 being markedly upregulated in

malignancies, and strongly associated with tumor aerobic glycolysis

and malignant progression (14,32).

Unlike other isomers, HK2 has unique structural features: Although

its secondary structure is very similar to that of HK1 and HK3,

both composed of two symmetrical α-helical regions linked to

glucokinase-catalyzed equivalent domains, HK2 is the only isomer

that maintains catalytic activity in both domains (2), which allows for more efficient

glycolysis (3). The N-terminal

hydrophobic domain of HK2 directly anchors to the voltage-dependent

anion channel (VDAC) located on the outer mitochondrial membrane.

This crucial interaction results in the formation of a

transmembrane-coupled complex with the adenine nucleotide

translocator on the inner membrane. Such a configuration

effectively prevents inhibition by G-6-P and establishes a

‘metabolic compartmentalization’ effect, thereby facilitating

efficient coordination between glycolysis and mitochondrial energy

metabolism within localized cellular regions (33). As a result, ATP produced by the

mitochondria is directly utilized by HK2 to initiate glycolysis,

creating a metabolic relay. This mechanism rapidly supplies the

energy, metabolic intermediates and precursors necessary for tumor

cell proliferation within a short period (34), thereby serving a pivotal role in

cancer cell proliferation, drug resistance and immune evasion

(35). Concurrently, HK2 localized

to the mitochondrial outer membrane serves a critical role in

inhibiting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition

pore, stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane potential, suppressing

the release of cytochrome c and blocking apoptotic signaling

pathways, thereby facilitating tumor cell survival (36,37).

Furthermore, HK2 is subject to O-GlcNAcylation, a process that

enhances cell proliferation, migration and invasion in non-small

cell lung cancer, and mitigates mitochondrial damage, and thus,

facilitates tumor progression (38).

Activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

facilitates cellular metabolic reprogramming (4) and is frequently associated with

immunosuppressive effects (21).

Research indicates that the AKT-induced nuclear translocation of

HK2 enhances the transcription of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)

through hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF-1α), which promotes

immune evasion in gastric cancer cells (39). AKT further activates the downstream

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), leading to the

stabilization of HIF-1α, which subsequently binds to

hypoxia-response elements (HREs) within the HK2 promoter. This

interaction establishes a positive feedback loop that upregulates

HK2 transcription, induces M2 macrophage polarization and

suppresses the functions of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells

(40). The inhibition of PI3K

activity or the application of 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) can reverse

these effects (41). A clinical

study has corroborated a positive association between the

expression of PI3K/AKT and HK2 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

with a marked increase in PD-L1 positivity observed in groups

exhibiting high co-expression levels (42). The programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/PD-L1 pathway inhibits T cell glycolysis and promotes

autophagy through negative regulation of HK2 activity (43). Inhibitors of

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit β,

such as AZD8186, disrupt the AKT-HK2 signaling pathway, leading to

decreased lactate production and the restoration of T cell

functionality (44). In glioma

models, the combination of HK2 inhibitors with PD-1 antibodies has

been demonstrated to enhance the infiltration of CD8+ T

cells (3,5). Future research should focus on

developing precise stratification strategies based on the

subcellular localization of HK2 and investigate the potential of

PI3K isoform-specific inhibitors.

The MAPK signaling pathway facilitates signal

transduction through a hierarchical kinase cascade, predominantly

involving the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2

(ERK1/2), c-Jun amino-terminal kinases 1 to 3 (JNK1 to −3), p38 (α,

β, γ and δ), and ERK5 families (45). HK2 activates ERK1/2 via the Raf/MEK

pathway, leading to the induction of cyclin A1 expression, the

downregulation of p27, the initiation of DNA replication stress,

the release of damage-associated molecular patterns, the activation

of chronic inflammatory responses and the recruitment of

immunosuppressive cells (46,47).

Furthermore, HK2 enhances the expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 1 through the JNK-c-Jun pathway, thereby inhibiting

CD8+ T cell infiltration, or modulates the

nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1) via p38 MAPKβ (48). hnRNPA1 interacts with the 3′

untranslated region of PD-L1 mRNA to maintain its stability,

consequently suppressing T cell activity (49) and fostering the development of an

immunosuppressive microenvironment. In the context of colorectal

cancer, fructose attenuates MAPK/signal transducer and activator of

transcription (STAT)1 signaling through the HK2- inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3-Ca2+ axis, thereby

inhibiting the polarization of M1-type tumor-associated macrophages

(TAMs) and further diminishing antitumor immune responses (50). In melanoma, the splicing of hnRNPA1

regulated by HK2 leads to the production of immunosuppressive human

leukocyte antigen G mRNA isoforms, which subsequently diminish the

cytotoxic efficacy of NK cells (51). Additionally, the pro-inflammatory

mediator, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, enhances HK2

expression through the MAPK-ERK signaling pathway, establishing an

immunosuppressive positive feedback loop that synergistically

promotes immune evasion by the tumor (52).

The NF-κB signaling pathway is activated by chronic

inflammation, oncogenic mutations or microenvironmental stressors

(53). HK2 interacts with the NF-κB

pathway through mechanisms that are both dependent and independent

of its metabolic functions. A seminal study conducted by Guo et

al (3) demonstrated that HK2

possessed non-metabolic roles in the cytoplasm, functioning as a

protein kinase to directly phosphorylate the threonine 291 residue

of the NF-κB inhibitor nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene

enhancer in B-cells inhibitor α (IκBα). This phosphorylation event

facilitated the degradation of IκBα via the µ-calpain-proteasome

pathway, thereby releasing the NF-κB dimer (RelA/p50) to

translocate into the nucleus and initiate the transcription of

immune checkpoint proteins, including PD-L1 (3). Concurrently, G-6-P, produced through

HK2 catalysis, activates the mTORC1 signaling pathway, which

promotes the phosphorylation of the IκB kinase complex and

indirectly increases NF-κB activity (54). Simultaneously, NF-κB directly

interacts with the HK2 promoter region, thereby augmenting its

transcriptional activity and activating downstream

glycolysis-related genes, which collectively constitute a

self-reinforcing regulatory network known as the ‘NF-κB-HK2-Warburg

effect’ (42).

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma models, the

HK2-IκBα-NF-κB axis markedly upregulates PD-L1 expression,

diminishes CD8+ T cell infiltration and stabilizes

β-catenin, thereby enhancing the self-renewal capacity of

CD133+ tumor stem cells and further mediating

immunosuppression (55). In

sarcoma, the canonical NF-κB pathway upregulates HK2 expression,

promoting lactate production and suppressing mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation, which results in the acidification of

the TME (56). Lactate contributes

to the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment by

activating regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2 macrophages, while

inhibiting dendritic cell (DC) maturation (57,58).

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that a combined therapeutic

approach utilizing the HK2-specific inhibitor 2-DG and the NF-κB

pathway inhibitor BAY11-7082 enhanced antitumor immune responses

through dual mechanisms: The suppression of PD-L1 protein

expression and the reversal of T cell exhaustion phenotypes

(59,60). This synergistic therapeutic effect

lays the theoretical groundwork for the clinical advancement of

innovative immunometabolic combination therapies.

The TGF-β pathway facilitates the differentiation of

immunosuppressive cells and diminishes immune cell cytotoxicity

through mechanisms that are both SMAD-dependent and independent,

thereby promoting an immune-tolerant phenotype (61). In models characterized by energy

deficiency induced by oligomycin A-mediated inhibition of oxidative

phosphorylation, highly metastatic HCT116 cells stimulated by TGF-β

contribute to the formation of an immunosuppressive

microenvironment through the upregulation of HK2 expression

(62). Furthermore, TGF-β modulates

HK2 expression by activating the SMAD3 pathway, while HK2 directly

interacts with TGF-β receptor I (TβRI) via its structural domain,

stabilizing the TβRI-TβRII complex and enhancing the

phosphorylation efficiency of SMAD2/3 (31,63).

This receptor-kinase interaction creates a positive feedback loop

that intensifies TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and stromal fibrosis, thereby physically obstructing T cell

infiltration into tumor beds (64–66).

Furthermore, the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway directly inhibits the

transcription of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I)

heavy chains and antigen processing-associated transporters

(67). Concurrently, HK2 activates

histone deacetylases through metabolic byproducts, leading to

further silencing of the epigenetic regulatory regions of MHC-I

genes and impairment of the recognition and binding of

tumor-specific antigens by immune cells (68).

The JAK/STAT pathway, a pivotal axis for cytokine

signal transduction, facilitates tumor immunosuppression through

aberrant activation of STAT3/STAT5 and alters the TME via metabolic

reprogramming (69). In colorectal

cancer, upregulation of HK2 enhances STAT3 phosphorylation, reduces

the infiltration of immune cells such as CD8+ T cells

and NK cells, and markedly increases PD-L1 levels, and these

effects are reversed by JAK/STAT3 inhibitors (5). Mechanistically, phosphorylated STAT3

directly binds to the PD-L1 promoter, and HK2 indirectly promotes

PD-L1 transcription by augmenting STAT3 activity (70).

SUMOylation has been identified as a crucial factor

in the cellular response to mitochondrial stress, acting as a

sensor and mediator of stress signals to maintain mitochondrial

homeostasis (65). This regulatory

mechanism is particularly relevant in the context of HK2,

suggesting that deSUMOylation likely enhances the interaction

between HK2 and VDAC1, thereby activating JAK2 kinase activity and

establishing an HK2-JAK2/STAT3-immunosuppressive positive feedback

loop (71,72). Epigenetic modifications serve a

notable role in this process. Specifically, methyltransferase-like

3 stabilizes HK2 mRNA through N6-methyladenosine

modification, and its upregulation enhances HK2 translation via

insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2, while

concurrently activating STAT3-dependent PD-L1 transcription

(73). Furthermore, the

accumulation of lactate mediated by HK2 inhibits glycolysis in T

cells, diminishes interferon γ (IFN-γ) secretion and activates the

JAK-STAT pathway through paracrine signaling, thereby further

impairing antitumor immunity (74)

(Table I).

The phenomenon of tumor immune escape is intricately

linked to the immune subtypes present within the TME (75). However, the specific role of HK2

within these subtypes remains poorly understood. A comprehensive

analysis utilizing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and the

International Union of Immunological Societies Immunology Databases

revealed that HK2 expression is markedly elevated in

immunosuppressive tumors, including pancreatic and liver cancers.

This elevated expression is associated with the accumulation of

Tregs and M2-type macrophages (76). Such an immunosuppressive milieu may

further facilitate tumor cell immune escape through metabolic

modulation mediated by HK2 (38).

Conversely, in immune-active tumors, such as melanoma, a negative

association between HK2 expression and T helper type 1 (Th1)

cytokines (such as IFN-γ and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9)

suggests that HK2 may alter the composition and functionality of

immune cells by modulating the expression of chemokines and

antigen-presenting molecules (77).

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that knockout of HK2 can

markedly increase the expression of MHC-II and its

antigen-presenting capabilities in DCs, while also modulating the

Th17/Treg balance in CD4+ T cells. This modulation

subsequently influences the specificity and intensity of the immune

response (78,79). These observations underscore the

pivotal role of HK2 in determining immune cell subtypes.

Consequently, these findings imply that HK2 is not only critical

within tumor cells but also potentially modulates immune responses

by affecting the functionality of immune cells within the tumor

immune microenvironment.

Lactate, a central metabolic product of HK2-driven

glycolysis, has transitioned from being considered merely a

‘metabolic waste product’ (80) to

a multifunctional mediator, acting as a signaling molecule, energy

substrate and immunoregulatory agent that governs tumor immune

evasion (81,82). Tumor cells continuously produce

lactate through HK2 hyperactivation, which increases extracellular

acidification rates, contributes to the formation of an acidic TME

and establishes an immunosuppressive niche through multiple

pathways (such as inhibiting the function of effector immune cells,

promoting the expansion of inhibitory immune cells, disrupting

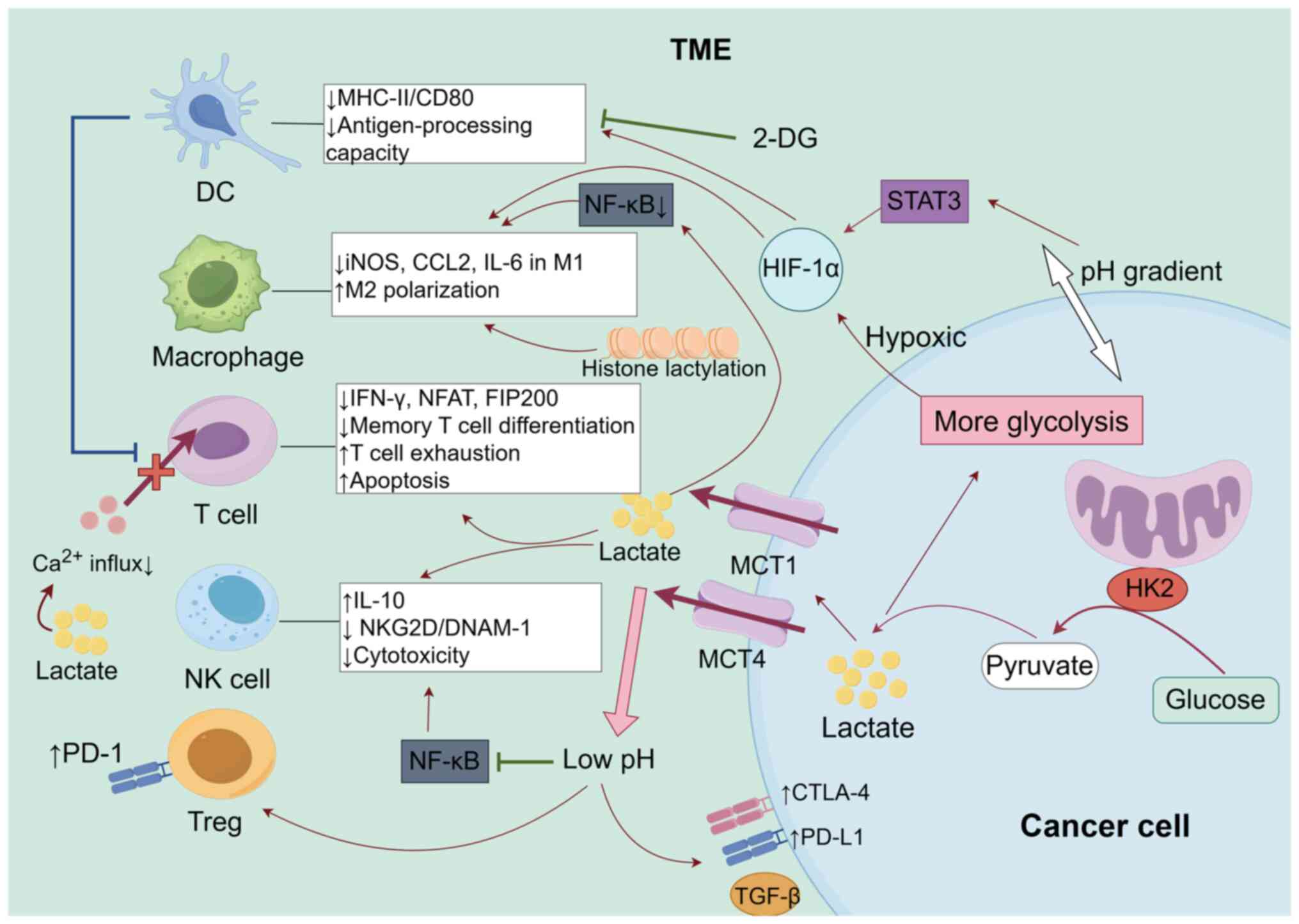

antigen presentation and upregulating checkpoints) (30). As shown in Fig. 1, the elevated lactate levels

mediated by HK2 result in a reduction in the calcium influx in T

cells, inhibition of IFN-γ secretion and prevention of the nuclear

translocation of activated T cell nuclear factors, as well as the

expression of the autophagy factor focal adhesion kinase family

interacting protein of 200 kDa (57,83,84).

These processes contribute to T cell exhaustion, apoptosis and a

diminished potential for memory T cell differentiation (85,86).

Application of the HK2 inhibitor 2-DG counteracts these effects,

thereby restoring the antitumor immune function of T cells

(87). HK2-driven glycolysis

creates intracellular and extracellular pH gradients, which

directly induce the expansion of Tregs and upregulate PD-1

expression. Furthermore, pH gradients downregulate major

MHC-II/CD80 expression through HIF-1α, thereby impairing the

antigen-processing capacity of DCs and the polarization of helper T

cells (88–91). Lactate also upregulates interleukin

(IL)-10 and downregulates acidification-dependent natural killer

group 2D (NKG2D) and DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1) by

suppressing the activation of NF-κB (92), leading to suppressed cytotoxicity in

NK cells (93,94). Additionally, lactate reduces the

expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, C-C motif chemokine

ligand (CCL)2 and IL-6 in M1 macrophages by inhibiting the activity

of the NF-κB signaling pathway, while the STAT3/HIF-1α axis

promotes macrophage M2 polarization, facilitating immune escape

(95,96). Furthermore, the elevation of lactate

mediated by HK2 upregulates inhibitory molecules such as PD-L1,

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 and TGF-β (97–99),

induces histone lysine lactylation, and establishes a

‘glycolysis-lactylation-immunosuppression’ positive feedback loop

(100,101).

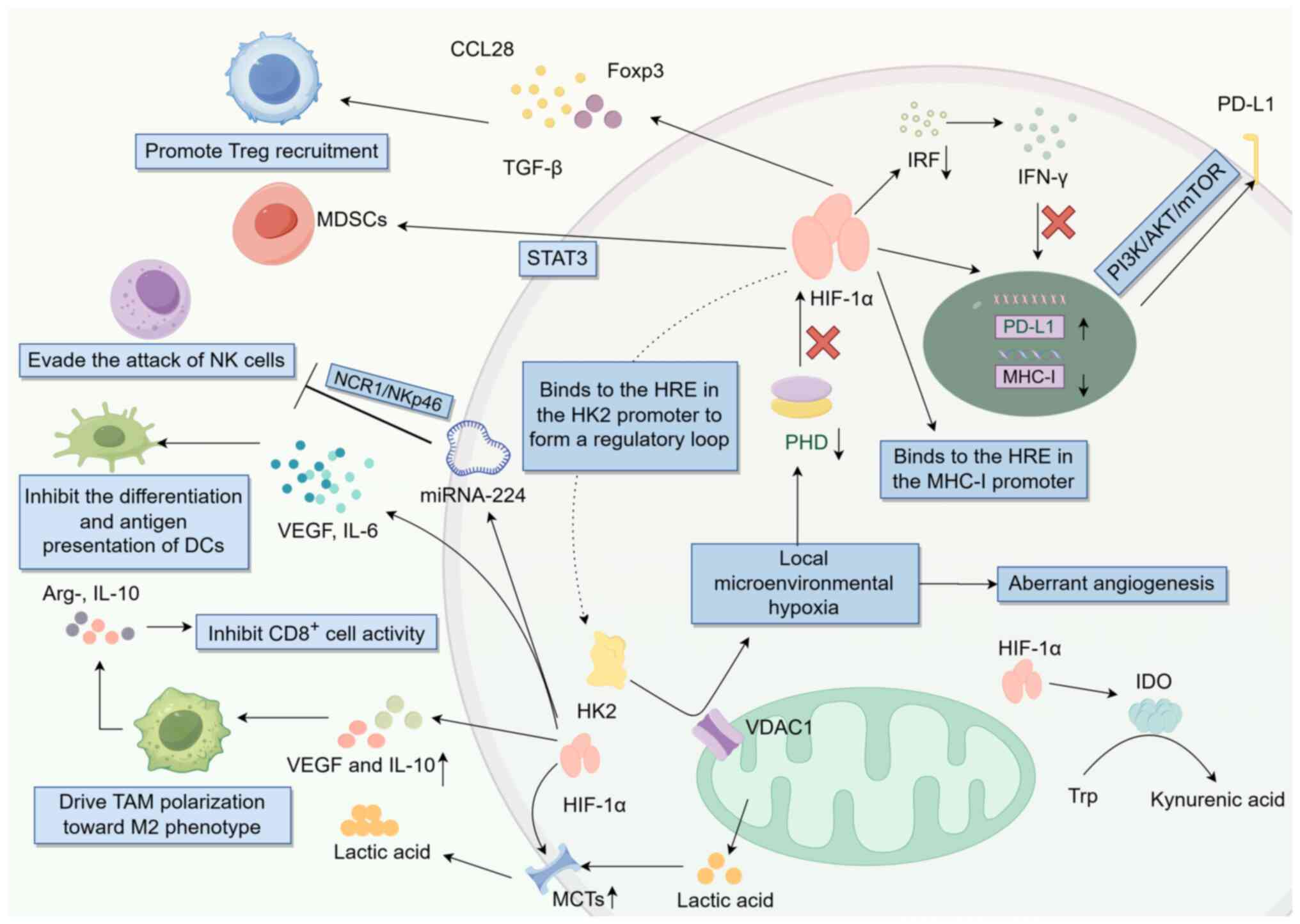

The interaction of HK2 with mitochondrial VDAC1

leads to localized microenvironmental hypoxia, which accelerates

lactate accumulation and abnormal angiogenesis, thereby further

exacerbating hypoxia (100,102).

As shown in Fig. 2, intratumoral

hypoxia predominantly inhibits the prolyl hydroxylase-mediated

stabilization of HIF-1α (103).

Activation of HIF-1α also enhances HK2 expression (104). The hypoxia-HIF-1α axis directly

interacts with HREs in the HK2 promoter, amplifying the hypoxia

process in the TME and forming an immunosuppressive feedforward

loop (105,106). Clinical investigations have

demonstrated that the HK2-mediated upregulation of HIF-1α in breast

and lung cancer is positively associated with PD-L1 expression, and

patients with high HK2 expression exhibit reduced response rates to

immune checkpoint inhibitors (107,108). Mechanistically, the activation of

HIF-1α by HK2 facilitates its binding to HREs within the PD-L1

promoter, leading to upregulation of PD-L1 transcription (109). Additionally, this activation

promotes the post-translational modifications of PD-L1 through the

activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (110). Furthermore, HK2-mediated

activation of HIF-1α results in the upregulation of microRNA-224,

which suppresses the natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor

1/NKp46 pathway and thereby protects tumors from NK cell-mediated

attack (111). HIF-1α also induces

the secretion of CCL28 and TGF-β by tumor cells, facilitating the

recruitment of Tregs to tumor sites (112,113), and sustains immunosuppressive

function of CCL28 and TGF-β by enhancing the expression of forkhead

box P3 (Foxp3) (114).

Concurrently, HIF-1α promotes the polarization of TAMs towards the

M2 phenotype through the upregulation of vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) and IL-10. These M2 TAMs subsequently secrete

arginase 1, IL-10 and other factors (such as TGF-β, PD-L1) that

inhibit the activity of CD8+ T cells (115). Furthermore, HIF-1α activates the

STAT3 pathway, leading to the expansion of myeloid-derived

suppressor cells, which further suppress the antitumor effects of

NK and T cells (116).

HK2-activated HIF-1α directly interacts with HREs in the MHC-I gene

promoter or recruits histone deacetylases to induce chromatin

compaction, thereby inhibiting MHC-I transcription (30). HIF-1α inhibits the IFN-γ-mediated

upregulation of MHC-I by suppressing the activity of IFN regulatory

factors (117). Additionally,

HIF-1α impairs DC differentiation and antigen-presenting

capabilities through the induction of VEGF and IL-6, resulting in

inadequate T cell priming (118).

HK2 further enhances the expression of HIF-1α and monocarboxylate

transporters, facilitating HK2-mediated lactate efflux and

exacerbating the immunosuppressive TME (119). HIF-1α also upregulates CD73

expression, which catalyzes the conversion of ATP to adenosine,

subsequently inhibiting T cell activation and NK cell cytotoxicity

via adenosine A2A receptor interaction (120–122). Furthermore, HIF-1α induces the

expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, leading to tryptophan

depletion and kynurenine acid production in the microenvironment,

thereby suppressing T cell proliferation and promoting Treg

differentiation (123,124).

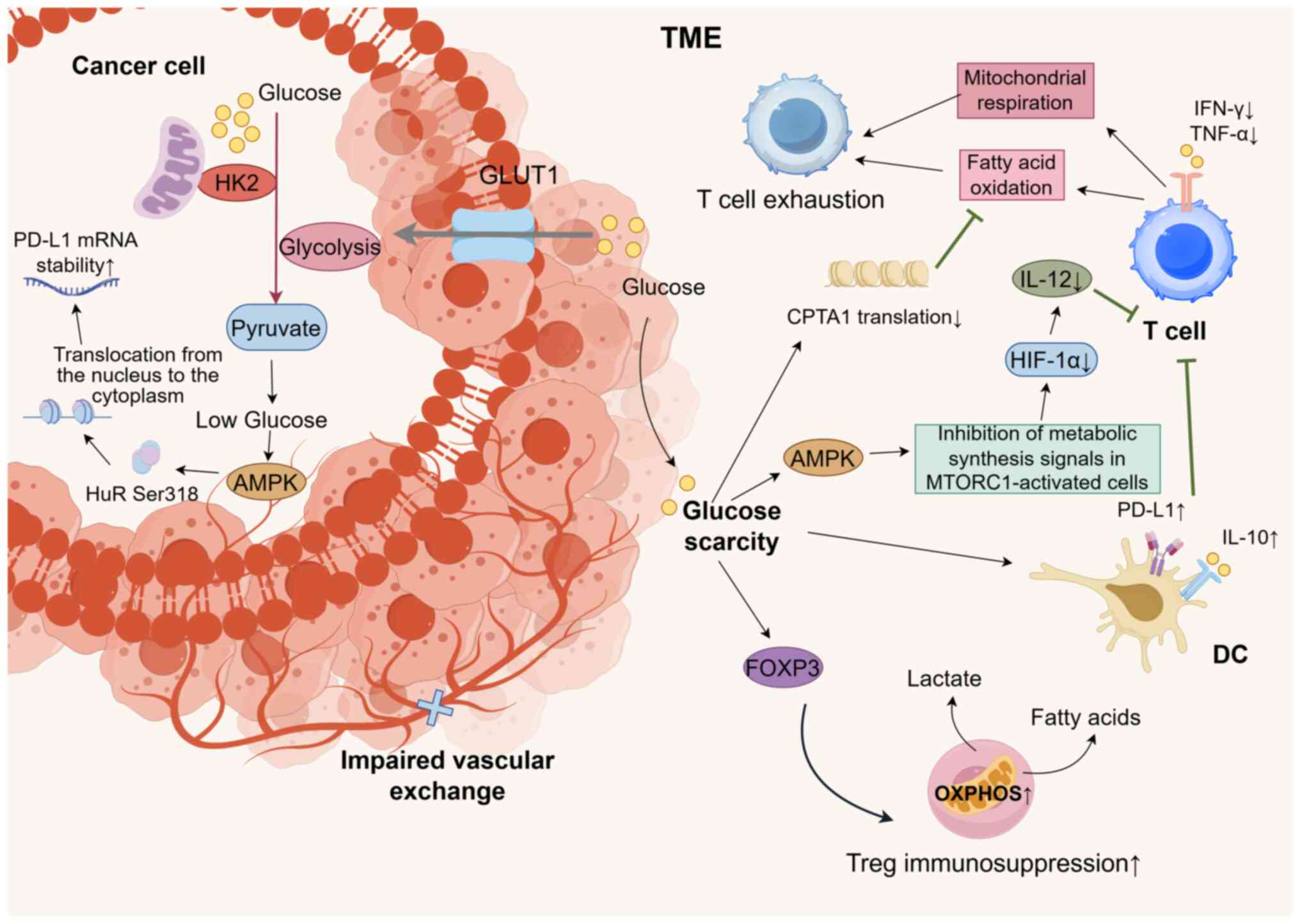

The synergistic effects of the HK2-mediated

glycolytic enhancement and impaired vascular exchange result in

limited glucose availability within the TME, causing intratumoral

hypoglycemia (125). Under these

glucose-deprivation conditions, the TME selectively impairs

glucose-dependent immune cells (126). As shown in Fig. 3, the hypoglycemic TME driven by HK2

activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), inhibits the signal

of MTORC1-activated cell metabolic synthesis, downregulates HIF-1α

expression, reduces IL-12 secretion and fails to effectively

activate naïve T cells (127–129). The secretion of effector cytokines

such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α is also diminished

(130). Under conditions of

HK2-induced glucose deprivation, T cells are compelled to shift

towards fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial respiration.

However, this metabolic shift is inefficient due to the suppression

of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A translation mediated by

glucose deprivation, ultimately leading to T cell exhaustion

(131). Hypoglycemia induces DCs

to adopt a tolerogenic phenotype characterized by elevated PD-L1

and IL-10 expression, further inhibiting T cell responses (128). By contrast, Tregs within the

hypoglycemic TME have enhanced oxidative phosphorylation through

Foxp3-mediated metabolic reprogramming, relying on fatty acid and

lactate metabolism to maintain their immunosuppressive functions.

This metabolic adaptation provides Tregs with a competitive

advantage in nutrient competition, thereby exacerbating antitumor

immune suppression (132).

Furthermore, glucose deprivation triggers the activation of the

AMPK pathway in tumor cells. AMPK phosphorylates Hu antigen R (HuR)

at Ser318, facilitating its translocation from the nucleus to the

cytoplasm (133). In melanoma

cells, the cytoplasmic localization of HuR increases from 20 to 60%

under hypoglycemic conditions, which enhances its binding affinity

to PD-L1 mRNA, and thus, stabilizes PD-L1 mRNA (134).

Advancements in the development of novel HK2

inhibitors have reached the clinical research phase, in which they

have shown notable antitumor activity (Table II). Small molecule inhibitors, such

as benserazide and benitrobenrazide (BNBZ), have been shown to

decrease glucose uptake, lactic acid production and intracellular

ATP levels by specifically binding to HK2 and inhibiting its

enzymatic function (135,136). This mechanism induces apoptosis in

tumor cells and suppresses tumor cell proliferation. BNBZ has

exhibited notable antitumor effects in xenograft mouse models using

SW1990 and SW480 cells, highlighting its potential as a promising

HK2 inhibitor (136). Similarly,

benserazide has been shown to effectively reduce tumor growth in a

SW480 cell xenograft mouse model without significant toxic effects

(135). The nanoparticle

formulation of benserazide further enhances its antitumor efficacy

and specificity in targeting tumors (135).

VDA-1102 (Almavid™), the first small molecule

targeting the HK2-VDAC1 interaction, disrupts HK2 mitochondrial

localization to restore cancer cell apoptosis. In a phase II trial

for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and actinic keratosis, VDA-1102

achieved an objective response rate (ORR) >60% with manageable

toxicity (137). The subcutaneous

formulation of VDA-1102 exhibited a stable plasma concentration

(>24 h) and dose-linear pharmacokinetics in pediatric patients

with brain tumors, indicating broad-spectrum potential in solid

tumors (138).

Ketoconazole, a United States Food and Drug

Administration-approved antifungal agent and HK2 inhibitor,

disrupts the interaction between HK2 and aminoacyl transfer RNA

synthetase complex-interacting multifunctional protein 2 (AIMP2).

This reduces autophagic lysosome-dependent degradation of AIMP2,

restoring AIMP2-mediated apoptosis and synergizing with

radiotherapy to suppress HCC growth. This drug-repurposing strategy

overcomes radioresistance with translational advantages in terms of

safety and cost (139).

A novel series of 2,6-disubstituted glucosamines has

been identified as potent and selective HK2 inhibitors. These

compounds demonstrate significant selectivity over HK1 and have

been shown to inhibit glycolysis in cancer cell lines, underscoring

their potential as therapeutic agents (140). Ikarugamycin, a polycyclic

tetramide macrolide compound isolated from Actinomycetes associated

with mangroves, has been shown to inhibit the glycolytic flux in

pancreatic cancer cells by targeting HK2 and exhibits antitumor

activity in murine models without exhibiting significant

cytotoxicity (141). Another

promising development in the field is the identification of natural

HK2 inhibitors from Ganoderma sinense. For example, a

specific steroid compound,

(22E,24R)-6β-methoxyergosta-7,9(11),22-triene-3β,5α-diol, has been

identified as having a high binding affinity for HK2, suggesting

its potential as a drug candidate for cancer therapy (142). This discovery is complemented by a

broader study that systematically reviews the characteristics of

HK2 inhibitors, emphasizing the need for compounds with improved

efficacy and selectivity due to the poor performance of existing

inhibitors when used alone (143).

RNA interference-based therapy, which silences the

expression of HK2, has been shown to inhibit tumor cell

proliferation and metastasis, thereby demonstrating notable

therapeutic potential (144–148). The clinical potential of HK2

inhibitors is further supported by studies on their role in

inducing apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer

cells. For instance, the HK2 inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate has been

shown to inhibit the survival and proliferation of colon cancer

cells, suggesting its utility in combination therapies (149). Additionally, the use of azole

antifungals, such as ketoconazole and posaconazole, has

demonstrated efficacy in targeting HK2-expressing glioblastoma

cells, providing a basis for repurposing these compounds in

clinical trials (150). These

findings collectively underscore the therapeutic promise of HK2

inhibitors and their potential to advance to clinical applications

(Table II).

As the role of HK2 in tumor immune evasion becomes

clearer, its utility as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy is

gaining attention. In bladder cancer research, the immune

expression of glycolysis-related proteins, including HK2, has been

assessed. The findings indicated that high HK2 expression was

closely associated with independent prognostic factors for

progression-free survival and overall survival, suggesting its

utility as a prognostic biomarker for patients with this disease

(151). In colorectal cancer, HK2

expression is associated with tumor size, depth of invasion, liver

metastasis and TNM stage, effectively predicting the recurrence

risk and overall mortality. Thus, HK2 serves as an important

prognostic biomarker (12).

Additionally, in patients with lung cancer, HK2 expression serves

as a biomarker for identifying a novel subset of circulating tumor

cells associated with poor prognosis. This finding is instrumental

for prognostic evaluation prior to treatment (152). Positron emission tomography

utilizing 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) is

a widely employed technique for assessing tumor glucose metabolism.

HK2 expression is associated with the uptake of 18F-FDG

by tumors (153). Consequently,

HK2 detection can facilitate the early diagnosis, staging and

evaluation of the treatment response in tumors (10). Furthermore, the development of a

ternary scoring system incorporating HK2, PD-L1 and HIF-1α for

predicting the response of patients with liver cancer is a

promising approach that leverages the interplay between metabolic

pathways, immune checkpoints and hypoxic conditions within the TME

(154). This model is

substantiated by several studies that highlight the critical roles

of these biomarkers in HCC prognosis and treatment response

(155–157).

The integration of single-cell transcriptomics and

spatial transcriptomics has revolutionized the current

understanding of cell dynamics and tissue structure, providing

unprecedented insights into the study of gene expression patterns

and cell interactions in natural spatial environments (158,159). This two-pronged research strategy

is particularly important when monitoring the changes in HK2; it

can achieve single-cell resolution analysis of HK2 expression

profiles while maintaining spatial information, thereby deeply

analyzing the expression distribution of HK2 in complex tissue

environments and its interaction with other factors. This strategy

can also provide in-depth insights into the metabolic heterogeneity

within tumors (160,161). Based on single-cell transcriptome

and spatial transcriptome techniques, the HK2-Glycolytic Activity

Index shows good stability in various tumor types and is associated

with the characteristics of immune infiltration in the tumor

microenvironment, having the potential to guide the selection of

CAR-T cell therapy (20).

Furthermore, advanced computational tools, such as the Significant

Process Inference Algorithm, enhance the detection of significant

expression patterns and biological processes, even the subtle

changes in HK2 expression across different cell populations

(162). Furthermore, the

application of deep learning models, such as KanCell, enhances the

analysis of cellular heterogeneity by integrating single-cell

RNA-sequencing and spatial transcriptomics data (163). These models can effectively

capture non-linear relationships and optimize computational

efficiency, providing a more accurate depiction of HK2 expression

patterns and their implications in disease microenvironments

(164). By leveraging these

advanced technologies, researchers can gain a deeper understanding

of the molecular mechanisms underlying HK2 regulation, and the

impact on cellular metabolism and disease progression.

Current research on tumor immune escape is focused

on several advanced fields. A comprehensive investigation into the

interactions among diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms within

the TME, particularly the metabolic interactions between immune

cells and tumor cells, will provide a theoretical foundation for

the development of more effective therapeutic strategies. Studies

have identified that TAMs facilitate tumor immune escape through

multiple signaling pathways, such as IL-4/STAT6, MAPK/ERK and

TLR-NF-κB (165–167). Therapeutic strategies aimed at

targeting TAMs, including colony stimulating factor 1 receptor

inhibitors and CD40 agonists, have progressed to clinical trials

(nos. NCT04169672 and NCT04059588), illustrating their potential to

mitigate immunosuppression and augment the effectiveness of

immunotherapy (78,168,169). Conversely, the utilization of

advanced technologies, such as single-cell sequencing and

high-dimensional flow cytometry, offers a deeper understanding of

the heterogeneity inherent in tumor immune evasion, thereby

providing a more precise foundation for personalized treatment

approaches (170).

The multifaceted role of HK2 in linking tumor

metabolic reprogramming and immune escape is becoming increasingly

evident. HK2, with its distinctive dual catalytic active domain and

N-terminal mitochondrial anchoring capability, facilitates the

‘metabolic compartmentalization’ effect and ‘metabolic relay’,

thereby mediating efficient glycolysis. HK2 has a bidirectional

regulatory network with critical oncogenic pathways, including the

PI3K/AKT, MAPK, NF-κB, TGF-β and JAK/STAT pathways, thereby

enhancing the glycolysis-dependent immune evasion of tumors. The

metabolic competition induced by the Warburg effect facilitates the

influence of HK2 on the function of immune cells in the TME,

leading to the formation of hypoxic and hypoglycemic niches. This

process is characterized by abundant lactic acid excretion, which

collectively influences immune cell distribution, alters immune

cell function and modulates the expression of immune checkpoints,

thereby further facilitating tumor immune escape. The protein

kinase function, subcellular localization regulation of HK2 and its

involvement in different immune subtypes have gained notable

attention, offering a novel perspective for a comprehensive

analysis of its non-glycolytic functions. Emerging HK2 inhibitors,

along with multi-dimensional predictive models and their

integration with immunotherapy, have demonstrated promising

potential for clinical translation. Future research should focus on

elucidating immune subtype-specific mechanisms, developing highly

selective targeted therapeutics and conducting comprehensive

analyses of HK2-related molecular characteristics. These efforts

should aim to advance the clinical implementation of HK2-targeted

intervention strategies in precision immunotherapy.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82505450), the Top Talent Support

Program for Young and Middle-Aged People of Wuxi Health Committee

(grant no. HB2023067), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu

Province (grant no. BK20240309), and the Natural Science Foundation

of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (grant no.

XZR2023095).

Not applicable.

YQ participated in conceptualization, data curation

and writing of the original draft. XZ participated in

conceptualization, acquisition of funding, and reviewing and

editing of the manuscript. DN and QT participated in reviewing and

editing the manuscript. CJ participated in reviewing and editing

the manuscript, and acquiring resources. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools (ChatGPT) were used to improve the readability

and language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors

revised and edited the content produced by the artificial

intelligence tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

|

1

|

Galassi C, Chan TA, Vitale I and Galluzzi

L: The hallmarks of cancer immune evasion. Cancer Cell.

42:1825–1863. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Paul S, Ghosh S and Kumar S: Tumor

glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer

Biol. 86:1216–1230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Guo D, Tong Y, Jiang X, Meng Y, Jiang H,

Du L, Wu Q, Li S, Luo S, Li M, et al: Aerobic glycolysis promotes

tumor immune evasion by hexokinase2-mediated phosphorylation of

IκBα. Cell Metab. 34:1312–1324. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu L, Jin Y, Zhao X, Tang K, Zhao Y, Tong

L, Yu X, Xiong K, Luo C, Zhu J, et al: Tumor aerobic glycolysis

confers immune evasion through modulating sensitivity to T

cell-mediated bystander killing via TNF-α. Cell Metab.

35:1580–1596. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Qing S and Shen Z: High expression of

hexokinase 2 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of

colorectal cancer cells by activating the JAK/STAT pathway and

regulating tumor immune microenvironment. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue

Bao. 45:542–553. 2025.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li C, Tang Y, Zhang R, Shi L, Chen J,

Zhang P, Zhang N and Li W: Inhibiting glycolysis facilitated

checkpoint blockade therapy for triple-negative breast cancer.

Discov Oncol. 16:5502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cheng M, Wang B, Duan L, Jin Y, Zhang W

and Li N: HOTAIR knockdown increases the sensitivity of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib by disrupting

miR-145-5p/HK2 axis-mediated mitochondrial function and glycolysis.

Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 30:373682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cui R, Wang G, Liu F, Wang Y, Zhao Z,

Mutailipu M, Mu H, Jiang X, Le W, Yang L and Chen B:

Neurturin-induced activation of GFRA2-RET axis potentiates

pancreatic cancer glycolysis via phosphorylated hexokinase 2.

Cancer Lett. 621:2175832025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lyu SI, Simon AG, Jung JO, Fretter C,

SchrÖder W, Bruns CJ, Schmidt T, Quaas A and Knipper K: Hexokinase

2 as an independent risk factor for worse patient survival in

esophageal adenocarcinoma and as a potential therapeutic target

protein: A retrospective, single-center cohort study. Oncol Lett.

28:4952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guo W, Kuang Y, Wu J, Wen D, Zhou A, Liao

Y, Song H, Xu D, Wang T, Jing B, et al: Hexokinase 2 depletion

confers sensitization to metformin and inhibits glycolysis in lung

squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 10:522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jin Z, Gu J, Xin X, Li Y and Wang H:

Expression of hexokinase 2 in epithelial ovarian tumors and its

clinical significance in serous ovarian cancer. Eur J Gynaecol

Oncol. 35:519–524. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Katagiri M, Karasawa H, Takagi K, Nakayama

S, Yabuuchi S, Fujishima F, Naitoh T, Watanabe M, Suzuki T, Unno M

and Sasano H: Hexokinase 2 in colorectal cancer: A potent

prognostic factor associated with glycolysis, proliferation and

migration. Histol Histopathol. 32:351–360. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yoshino H, Enokida H, Itesako T, Kojima S,

Kinoshita T, Tatarano S, Chiyomaru T, Nakagawa M and Seki N:

Tumor-suppressive microRNA-143/145 cluster targets hexokinase-2 in

renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 104:1567–1574. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Botzer LE, Maman S, Sagi-Assif O, Meshel

T, Nevo I, Yron I and Witz IP: Hexokinase 2 is a determinant of

neuroblastoma metastasis. Br J Cancer. 114:759–766. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gao H, Zhou Y and Chen X: Tregs and

platelets play synergistic roles in tumor immune escape and

inflammatory diseases. Crit Rev Immunol. 42:59–69. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu Y, Wu K, Shi L, Xiang F, Tao K and

Wang G: Prognostic significance of the metabolic marker

hexokinase-2 in various solid tumors: A meta-analysis. PLoS One.

11:e01662302016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kwee SA, Hernandez B, Chan O and Wong L:

Choline kinase alpha and hexokinase-2 protein expression in

hepatocellular carcinoma: Association with survival. PLoS One.

7:e465912012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Suh DH, Kim MA, Kim H, Kim MK, Kim HS,

Chung HH, Kim YB and Song YS: Association of overexpression of

hexokinase II with chemoresistance in epithelial ovarian cancer.

Clin Exp Med. 14:345–353. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang XT, Xie L, Hu YT, Zhao YY, Wang RY,

Yan Y, Zhu XZ and Liu LL: T. pallidum achieves immune evasion by

blocking autophagic flux in microglia through hexokinase 2. Microb

Pathog. 199:1072162025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lin J, Fang W, Xiang Z, Wang Q, Cheng H,

Chen S, Fang J, Liu J, Wang Q, Lu Z and Ma L: Glycolytic enzyme HK2

promotes PD-L1 expression and breast cancer cell immune evasion.

Front Immunol. 14:11899532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang L, Jiang C, Zhong Y, Sun K, Jing H,

Song J, Xie J, Zhou Y, Tian M, Zhang C, et al: STING is a

cell-intrinsic metabolic checkpoint restricting aerobic glycolysis

by targeting HK2. Nat Cell Biol. 25:1208–1222. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li J, Xu S, Zhan Y, Lv X, Sun Z, Man L,

Yang D, Sun Y and Ding S: CircRUNX1 enhances the Warburg effect and

immune evasion in non-small cell lung cancer through the

miR-145/HK2 pathway. Cancer Lett. 28:2176392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li R, Mei S, Ding Q, Wang Q, Yu L and Zi

F: A pan-cancer analysis of the role of hexokinase II (HK2) in

human tumors. Sci Rep. 12:188072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron

M, Liu X, Amezquita R, Tsui YC, Cui G, Micevic G, Perales JC, et

al: Phosphoenolpyruvate is a metabolic checkpoint of anti-tumor T

cell responses. Cell. 162:1217–1228. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chang CH, Qiu J, O'Sullivan D, Buck MD,

Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ,

et al: Metabolic competition in the tumor microenvironment is a

driver of cancer progression. Cell. 162:1229–1241. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shi ZY, Yang C, Lu LY, Lin CX, Liang S, Li

G, Zhou HM and Zheng JM: Inhibition of hexokinase 2 with 3-BrPA

promotes MDSCs differentiation and immunosuppressive function. Cell

Immunol. 385:1046882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

İpek ӦS, Sucu BO, Selvi S, Alkan FK,

Tiryaki B, Alkan HK, Sayyah E, Tolu İ, Güzel M, Durdağı S, et al:

Anti-cancer efficacy of novel lonidamine derivatives: Design,

synthesis, in vitro, in vivo, and computational studies targeting

hexokinase-2. Eur J Med Chem. 296:1178902025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gu QL, Zhang Y, Fu XM, Lu ZL, Yu Y, Chen

G, Ma R, Kou W and Lan YM: Toxicity and metabolism of

3-bromopyruvate in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B.

21:77–86. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pajak B, Siwiak E, Sołtyka M, Priebe A,

Zieliński R, Fokt I, Ziemniak M, Jaśkiewicz A, Borowski R,

Domoradzki T and Priebe W: 2-Deoxy-d-glucose and its analogs: From

diagnostic to therapeutic agents. Int J Mol Sci. 21:2342019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rho H, Terry AR, Chronis C and Hay N:

Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is

required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis.

Cell Metab. 35:1406–1423. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Patra KC, Wang Q, Bhaskar PT, Miller L,

Wang Z, Wheaton W, Chandel N, Laakso M, Muller WJ, Allen EL, et al:

Hexokinase 2 is required for tumor initiation and maintenance and

its systemic deletion is therapeutic in mouse models of cancer.

Cancer Cell. 24:213–228. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu Y, Li M, Zhang Y, Wu C, Yang K, Gao S,

Zheng M, Li X, Li H and Chen L: Structure based discovery of novel

hexokinase 2 inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 96:1036092020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bustamante E and Pedersen PL:

Mitochondrial hexokinase of rat hepatoma cells in culture:

Solubilization and kinetic properties. Biochemistry. 19:4972–4977.

1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D and

Thompson CB: Brick by brick: Metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr

Opin Genet Dev. 18:54–61. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ganapathy-Kanniappan S and Geschwind JF:

Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and

prospects. Mol Cancer. 12:1522013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nawaz MH, Ferreira JC, Nedyalkova L, Zhu

H, Carrasco-López C, Kirmizialtin S and Rabeh WM: The catalytic

inactivation of the N-half of human hexokinase 2 and structural and

biochemical characterization of its mitochondrial conformation.

Biosci Rep. 38:BSR201716662018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee HJ, Li CF, Ruan D, He J, Montal ED,

Lorenz S, Girnun GD and Chan CH: Non-proteolytic ubiquitination of

Hexokinase 2 by HectH9 controls tumor metabolism and cancer stem

cell expansion. Nat Commun. 10:26252019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Panpan SI, Wei GE, Kaiming WU and Zhang R:

O-GlcNAcylation of hexokinase 2 modulates mitochondrial dynamics

and enhances the progression of lung cancer. Mol Cell Biochem.

480:2633–2643. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Huang C, Chen B, Wang X, Xu J, Sun L, Wang

D, Zhao Y, Zhou C, Gao Q, Wang Q, et al: Gastric cancer mesenchymal

stem cells via the CXCR2/HK2/PD-L1 pathway mediate

immunosuppression. Gastric Cancer. 26:691–707. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ranjbar A, Soltanshahi M, Taghiloo S and

Asgarian-Omran H: Glucose metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia cell

line is regulated via combinational PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

inhibitors. Iran J Pharm Res. 22:e1405072023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Collins NB, Al Abosy R, Milsler BC, Bi K,

Zhao Q, Quigley M, Ishizuka JJ, Yates KB, Pope HW, Manguso R, et

al: PI3K activation allows immune evasion by promoting an

inhibitory myeloid tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer.

10:e0034022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen L, Lin X, Lei Y, Xu X, Zhou Q, Chen

Y, Liu H, Jiang J, Yang Y, Zheng F and Wu B: Aerobic glycolysis

enhances HBx-initiated hepatocellular carcinogenesis via

NF-κBp65/HK2 signalling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:3292022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kawasaki Y, Sato K, Mashima K, Nakano H,

Ikeda T, Umino K, Morita K, Izawa J, Takayama N, Hayakawa H, et al:

Mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit aerobic glycolysis in activated t

cells by negatively regulating hexokinase II activity through

PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. Transplant Cell Ther. 27:231.e231–231.e238.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lynch JT, Polanska UM, Delpuech O, Hancox

U, Trinidad AG, Michopoulos F, Lenaghan C, McEwen R, Bradford J,

Polanski R, et al: Inhibiting PI3Kβ with AZD8186 regulates key

metabolic pathways in PTEN-null tumors. Clin Cancer Res.

23:7584–7595. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cargnello M and Roux PP: Activation and

function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated

protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 75:50–83. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ji P, Bäumer N, Yin T, Diederichs S, Zhang

F, Beger C, Welte K, Fulda S, Berdel WE, Serve H, et al: DNA damage

response involves modulation of Ku70 and Rb functions by cyclin A1

in leukemia cells. Int J Cancer. 121:706–713. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cui N, Li L, Feng Q, Ma HM, Lei D and

Zheng PS: Hexokinase 2 promotes cell growth and tumor formation

through the raf/mek/erk signaling pathway in cervical cancer. Front

Oncol. 10:5812082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Courteau L, Crasto J, Hassanzadeh G, Baird

SD, Hodgins J, Liwak-Muir U, Fung G, Luo H, Stojdl DF, Screaton RA

and Holcik M: Hexokinase 2 controls cellular stress response

through localization of an RNA-binding protein. Cell Death Dis.

6:e18372015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lian C, Zhang C, Tian P, Tan Q, Wei Y,

Wang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Zhong M, Zhou L, et al: Epigenetic reader

ZMYND11 noncanonical function restricts HNRNPA1-mediated stress

granule formation and oncogenic activity. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 9:2582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yan H, Wang Z, Teng D, Chen X, Zhu Z, Chen

H, Wang W, Wei Z, Wu Z, Chai Q, et al: Hexokinase 2 senses fructose

in tumor-associated macrophages to promote colorectal cancer

growth. Cell Metab. 36:2449–2467. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dunnett L, Das S, Venditti V and Prischi

F: Enhanced identification of small molecules binding to hnRNPA1

via cryptic pockets mapping coupled with X-ray fragment screening.

J Biol Chem. 301:1083352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yang S, Tang W, Azizian A, Gaedcke J,

Ohara Y, Cawley H, Hanna N, Ghadimi M, Lal T, Sen S, et al:

MIF/NR3C2 axis regulates glucose metabolism reprogramming in

pancreatic cancer through MAPK-ERK and AP-1 pathways.

Carcinogenesis. 45:582–594. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhang T, Ma C, Zhang Z, Zhang H and Hu H:

NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm (2020).

2:618–653. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jiang Q, Xu J and Wang H:

Intestine-derived exosomes regulates inflammatory response of HK-2

cells through miR-146a-regulated NF-κB pathway. Drug Eval Res.

47:2326–2333. 2024.

|

|

55

|

Tong Y, Liu X, Wu L, Xiang Y, Wang J,

Cheng Y, Zhang C, Han B, Wang L and Yan D: Hexokinase 2

nonmetabolic function-mediated phosphorylation of IκBα enhances

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression. Cancer Sci.

115:2673–2685. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Londhe P, Yu PY, Ijiri Y, Ladner KJ,

Fenger JM, London C, Houghton PJ and Guttridge DC: Classical NF-κB

metabolically reprograms sarcoma cells through regulation of

hexokinase 2. Front Oncol. 8:1042018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M,

Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et

al: LDHA-associated lactic acid production blunts tumor

immunosurveillance by T and NK cells. Cell Metab. 24:657–671. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T,

Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC,

Phillips GM, et al: Functional polarization of tumour-associated

macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 513:559–563.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sharan L, Pal A, Babu SS, Kumar A and

Banerjee S: Bay 11-7082 mitigates oxidative stress and

mitochondrial dysfunction via NLRP3 inhibition in experimental

diabetic neuropathy. Life Sci. 359:1232032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Dent AT and Wilks A: Contributions of the

heme coordinating ligands of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer

membrane receptor HasR to extracellular heme sensing and transport.

J Biol Chem. 295:10456–10467. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Derynck R, Turley SJ and Akhurst RJ: TGFβ

biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 18:9–34. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhong C, Wang W, Yao Y, Lian S, Xie X, Xu

J, He S, Luo L, Ye Z, Zhang J, et al: TGF-β secreted by cancer

cells-platelets interaction activates cancer metastasis potential

by inducing metabolic reprogramming and bioenergetic adaptation. J

Cancer. 16:1310–1323. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Roh JI, Kim Y, Oh J, Kim Y, Lee J, Lee J,

Chun KH and Lee HW: Hexokinase 2 is a molecular bridge linking

telomerase and autophagy. PLoS One. 13:e01931822018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Lu J, Liu Q, Wang L, Tu W, Chu H, Ding W,

Jiang S, Ma Y, Shi X, Pu W, et al: Increased expression of latent

TGF-β-binding protein 4 affects the fibrotic process in scleroderma

by TGF-β/SMAD signaling. Lab Invest. 97:591–601. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Jiang YL, Li X, Tan YW, Fang YJ, Liu KY,

Wang YF, Ma T, Ou QJ and Zhang CX: Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits

the invasion and migration of colorectal cancer by reversing EMT

through the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. Food Funct.

15:9420–9433. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D,

Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y, Kadel EE III, Koeppen H, Astarita

JL, Cubas R, et al: TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1

blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature.

554:544–548. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jeon HS and Jen J: TGF-beta signaling and

the role of inhibitory Smads in non-small cell lung cancer. J

Thorac Oncol. 5:417–419. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Santarpia M, González-Cao M, Viteri S,

Karachaliou N, Altavilla G and Rosell R: Programmed cell death

protein-1/programmed cell death ligand-1 pathway inhibition and

predictive biomarkers: Understanding transforming growth

factor-beta role. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 4:728–742.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ayele TM, Muche ZT, Teklemariam AB, Kassie

AB and Abebe EC: Role of JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in the

tumorigenesis, chemotherapy resistance, and treatment of solid

tumors: A systemic review. J Inflamm Res. 15:1349–1364. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ren D, Hua Y, Yu B, Ye X, He Z, Li C, Wang

J, Mo Y, Wei X, Chen Y, et al: Predictive biomarkers and mechanisms

underlying resistance to PD1/PD-L1 blockade cancer immunotherapy.

Mol Cancer. 19:192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Shangguan X, He J, Ma Z, Zhang W, Ji Y,

Shen K, Yue Z, Li W, Xin Z, Zheng Q, et al: SUMOylation controls

the binding of hexokinase 2 to mitochondria and protects against

prostate cancer tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 12:18122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Xue YN, Yu BB, Li JL, Guo R, Zhang LC, Sun

LK, Liu YN and Li Y: Zinc and p53 disrupt mitochondrial binding of

HK2 by phosphorylating VDAC1. Exp Cell Res. 374:249–258. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wang Q, Guo X, Li L, Gao Z, Su X, Ji M and

Liu J: N6-methyladenosine METTL3 promotes cervical

cancer tumorigenesis and Warburg effect through YTHDF1/HK2

modification. Cell Death Dis. 11:9112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Klinke DJ II, Cheng N and Chambers E:

Quantifying crosstalk among interferon-γ, interleukin-12, and tumor

necrosis factor signaling pathways within a TH1 cell model. Sci

Signal. 5:ra322012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zhang H, Li S, Wang D, Liu S, Xiao T, Gu

W, Yang H, Wang H, Yang M and Chen P: Metabolic reprogramming and

immune evasion: The interplay in the tumor microenvironment.

Biomark Res. 12:962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ferreira JC, Khrbtli AR, Shetler CL,

Mansoor S, Ali L, Sensoy O and Rabeh WM: Linker residues regulate

the activity and stability of hexokinase 2, a promising anticancer

target. J Biol Chem. 296:1000712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Peláez R, Fernández-García P, Herrero P

and Moreno F: Nuclear import of the yeast hexokinase 2 protein

requires α/β-importin-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem.

287:3518–3529. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li S, Zhang M, Gao Y, Zhao C, Liao S, Zhao

X, Ning Q and Tang S: Mechanisms of tumor-associated macrophages

promoting tumor immune escape. Carcinogenesis. 46:bgaf0232025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Gou Q, Che S, Chen M, Chen H, Shi J and

Hou Y: PPARγ inhibited tumor immune escape by inducing PD-L1

autophagic degradation. Cancer Sci. 114:2871–2881. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerbäck S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2:566–571. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Brooks GA: The science and translation of

lactate shuttle theory. Cell Metab. 27:757–785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Zhang W, Wang G, Xu ZG, Tu H, Hu F, Dai J,

Chang Y, Chen Y, Lu Y, Zeng H, et al: Lactate is a natural

suppressor of rlr signaling by targeting MAVS. Cell. 178:176–189.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr, Faubert

B, Villarino AV, O'Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih

J, Qiu J, et al: Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector

function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 153:1239–1251. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Xia H, Wang W, Crespo J, Kryczek I, Li W,

Wei S, Bian Z, Maj T, He M, Liu RJ, et al: Suppression of FIP200

and autophagy by tumor-derived lactate promotes naïve T cell

apoptosis and affects tumor immunity. Sci Immunol. 2:eaan46312017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Arruga F, Gyau BB, Iannello A, Vitale N,

Vaisitti T and Deaglio S: Immune response dysfunction in chronic

lymphocytic leukemia: Dissecting molecular mechanisms and

microenvironmental conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 21:18252020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Corbet C and Feron O: Tumour acidosis:

From the passenger to the driver's seat. Nat Rev Cancer.

17:577–593. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Sukumar M, Liu J, Ji Y, Subramanian M,

Crompton JG, Yu Z, Roychoudhuri R, Palmer DC, Muranski P, Karoly

ED, et al: Inhibiting glycolytic metabolism enhances CD8+ T cell

memory and antitumor function. J Clin Invest. 123:4479–4488. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Nasi A, Fekete T, Krishnamurthy A, Snowden

S, Rajnavölgyi E, Catrina AI, Wheelock CE, Vivar N and Rethi B:

Dendritic cell reprogramming by endogenously produced lactic acid.

J Immunol. 191:3090–3099. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S,

Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G,

Hoves S, et al: Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid

on human T cells. Blood. 109:3812–3819. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Lin S, Sun L, Lyu X, Ai X, Du D, Su N, Li

H, Zhang L, Yu J and Yuan S: Lactate-activated macrophages induced

aerobic glycolysis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast

cancer by regulation of CCL5-CCR5 axis: A positive metabolic

feedback loop. Oncotarget. 8:110426–110443. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Zappasodi R, Serganova I, Cohen IJ, Maeda

M, Shindo M, Senbabaoglu Y, Watson MJ, Leftin A, Maniyar R, Verma

S, et al: CTLA-4 blockade drives loss of T(reg) stability in

glycolysis-low tumours. Nature. 591:652–658. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Liu N, Luo J, Kuang D, Xu S, Duan Y, Xia

Y, Wei Z, Xie X, Yin B, Chen F, et al: Lactate inhibits ATP6V0d2

expression in tumor-associated macrophages to promote

HIF-2α-mediated tumor progression. J Clin Invest. 129:631–646.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Gao Y, Zhou H, Liu G, Wu J, Yuan Y and

Shang A: Tumor microenvironment: Lactic acid promotes tumor

development. J Immunol Res. 2022:31193752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Langin D: Adipose tissue lipolysis

revisited (again!): Lactate involvement in insulin antilipolytic

action. Cell Metab. 11:242–243. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Pan Y, Yu Y, Wang X and Zhang T:

Corrigendum: Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front

Immunol. 12:7757582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

El-Kenawi A, Gatenbee C, Robertson-Tessi

M, Bravo R, Dhillon J, Balagurunathan Y, Berglund A, Vishvakarma N,

Ibrahim-Hashim A, Choi J, et al: Acidity promotes tumour

progression by altering macrophage phenotype in prostate cancer. Br

J Cancer. 121:556–566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Liu Q, Du F, Huang W, Ding X, Wang Z, Yan

F and Wu Z: Epigenetic control of Foxp3 in intratumoral T-cells

regulates growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY).

11:2343–2351. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Yu J, Chai P, Xie M, Ge S, Ruan J, Fan X

and Jia R: Histone lactylation drives oncogenesis by facilitating

m6A reader protein YTHDF2 expression in ocular melanoma.

Genome Biol. 22:852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Jiang J, Huang D, Jiang Y, Hou J, Tian M,

Li J, Sun L, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Li Z, et al: Lactate modulates

cellular metabolism through histone lactylation-mediated gene

expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol.

11:6475592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Certo M, Tsai CH, Pucino V, Ho PC and

Mauro C: Lactate modulation of immune responses in inflammatory

versus tumour microenvironments. Nat Rev Immunol. 21:151–161. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Wang N, Wang W, Wang X, Mang G, Chen J,

Yan X, Tong Z, Yang Q, Wang M, Chen L, et al: Histone lactylation

boosts reparative gene activation post-myocardial infarction. Circ

Res. 131:893–908. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Mathupala SP, Ko YH and Pedersen PL:

Hexokinase II: Cancer's double-edged sword acting as both

facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to

mitochondria. Oncogene. 25:4777–4786. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ and Simon MC:

Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol

Cell. 40:294–309. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang LF, Lou JT, Lu MH, Gao C, Zhao S, Li

B, Liang S, Li Y, Li D and Liu MF: Suppression of miR-199a

maturation by HuR is crucial for hypoxia-induced glycolytic switch

in hepatocellular carcinoma. EMBO J. 34:2671–2685. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Bao MH and Wong CC: Hypoxia, metabolic

reprogramming, and drug resistance in liver cancer. Cells.

10:17152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Reyes A, Duarte LF, Farías MA, Tognarelli

E, Kalergis AM, Bueno SM and González PA: Impact of hypoxia over

human viral infections and key cellular processes. Int J Mol Sci.

22:79542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Zheng H, Ning Y, Zhan Y, Liu S, Yang Y,

Wen Q and Fan S: Co-expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α predicts poor

prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer after

surgery. J Cancer. 12:2065–2072. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Bandopadhyay S and Patranabis S:

Mechanisms of HIF-driven immunosuppression in tumour

microenvironment. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 35:272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

You L, Wang X, Wu W, Nepovimova E, Wu Q

and Kuca K: HIF-1α inhibits T-2 toxin-mediated ‘immune evasion’

process by negatively regulating PD-1/PD-L1. Toxicology.

480:1533242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Yang Z, Su W, Wei X, Pan Y, Xing M, Niu L,

Feng B, Kong W, Ren X, Huang F, et al: Hypoxia inducible factor-1α

drives cancer resistance to cuproptosis. Cancer Cell. 43:937–954.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Chen CH, Li SX, Xiang LX, Mu HQ, Wang SB

and Yu KY: HIF-1α induces immune escape of prostate cancer by

regulating NCR1/NKp46 signaling through miR-224. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 503:228–234. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Facciabene A, Peng X, Hagemann IS, Balint

K, Barchetti A, Wang LP, Gimotty PA, Gilks CB, Lal P, Zhang L and

Coukos G: Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via

CCL28 and T(reg) cells. Nature. 475:226–230. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Peng J, Wang X, Ran L, Song J, Luo R and

Wang Y: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α regulates the transforming

growth factor β1/SMAD family member 3 pathway to promote breast

cancer progression. J Breast Cancer. 21:259–266. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Clambey ET, McNamee EN, Westrich JA,

Glover LE, Campbell EL, Jedlicka P, de Zoeten EF, Cambier JC,

Stenmark KR, Colgan SP and Eltzschig HK: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1

alpha-dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T-cell

abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:E2784–E2793. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Sormendi S and Wielockx B: Hypoxia pathway

proteins as central mediators of metabolism in the tumor cells and

their microenvironment. Front Immunol. 9:402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Balamurugan K: HIF-1 at the crossroads of

hypoxia, inflammation, and cancer. Int J Cancer. 138:1058–1066.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Murthy A, Gerber SA, Koch CJ and Lord EM:

Intratumoral hypoxia reduces IFN-γ-mediated immunity and mhc class

I induction in a preclinical tumor model. Immunohorizons.

3:149–160. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Bhandari T, Olson J, Johnson RS and Nizet

V: HIF-1α influences myeloid cell antigen presentation and response

to subcutaneous OVA vaccination. J Mol Med (Berl). 91:1199–1205.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Ruiz-Iglesias A and Mañes S: The

importance of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier in cancer cell

metabolism and tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel). 13:14882021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Zhang T, Yu-Jing L and Ma T: The

immunomodulatory function of adenosine in sepsis. Front Immunol.

13:9365472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B and Pacher

P: Adenosine receptors: Therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and

immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 7:759–770. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Chambers AM and Matosevic S:

Immunometabolic dysfunction of natural killer cells mediated by the

hypoxia-CD73 axis in solid tumors. Front Mol Biosci. 6:602019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Zhao F, Xiao C, Evans KS, Theivanthiran T,

DeVito N, Holtzhausen A, Liu J, Liu X, Boczkowski D, Nair S, et al:

Paracrine Wnt5a-β-catenin signaling triggers a metabolic program

that drives dendritic cell tolerization. Immunity. 48:147–160.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Godin-Ethier J, Hanafi LA, Piccirillo CA

and Lapointe R: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in human

cancers: Clinical and immunologic perspectives. Clin Cancer Res.

17:6985–6991. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Irshad Z, Xue M, Ashour A, Larkin JR,

Thornalley PJ and Rabbani N: Activation of the unfolded protein

response in high glucose treated endothelial cells is mediated by

methylglyoxal. Sci Rep. 9:78892019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Siska PJ, Beckermann KE, Mason FM,

Andrejeva G, Greenplate AR, Sendor AB, Chiang YJ, Corona AL, Gemta

LF, Vincent BG, et al: Mitochondrial dysregulation and glycolytic

insufficiency functionally impair CD8 T cells infiltrating human

renal cell carcinoma. JCI Insight. 2:e934112017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Blagih J, Coulombe F, Vincent EE, Dupuy F,

Galicia-Vázquez G, Yurchenko E, Raissi TC, van der Windt GJ,

Viollet B, Pearce EL, et al: The energy sensor AMPK regulates T

cell metabolic adaptation and effector responses in vivo. Immunity.

42:41–54. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Liu X, Zhao Y, Wu X, Liu Z and Liu X: A

novel strategy to fuel cancer immunotherapy: Targeting glucose

metabolism to remodel the tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol.

12:9311042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Liu X, Mo W, Ye J, Li L, Zhang Y, Hsueh

EC, Hoft DF and Peng G: Regulatory T cells trigger effector T cell

DNA damage and senescence caused by metabolic competition. Nat

Commun. 9:2492018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Scharping NE and Delgoffe GM: Tumor

microenvironment metabolism: A new checkpoint for anti-tumor

immunity. Vaccines (Basel). 4:462016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Jiang Y, Li Y and Zhu B: T-cell exhaustion

in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 6:e17922015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Bader JE, Voss K and Rathmell JC: