Introduction

Salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma (SACC) is a

relatively rare but aggressive malignancy of the salivary glands,

accounting for ~25% of all salivary gland tumors (1,2). The

tendency of SACC to invade locally and metastasize distantly makes

it difficult to manage clinically. Despite advancements in

multimodal therapies, including surgery in combination with

radiotherapy or chemotherapy, >30% of patients experience local

recurrence and face poor prognosis (3–5). Thus,

elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying SACC invasion and

metastasis is key for improving patient outcomes.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key

biological process during tumor progression, endows cancer cells

with increased plasticity, promoting their migration and invasion

capabilities (6). EMT is marked by

the loss of epithelial characteristics, such as polarity and

intercellular adhesion, and the acquisition of mesenchymal markers

(7,8). Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) serves as

a serine/threonine kinase and scaffolding protein involved in

diverse signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β-catenin

pathways (9,10). Its N-terminal ankyrin repeat domain

binds particularly interesting new cysteine-histidine-rich protein

(PINCH), while the C-terminal kinase domain associates with Parvin

to form the ILK-PINCH-Parvin complex. This complex broadly

participates in the molecular regulation of malignant phenotypes,

including cell cycle progression, migration, invasion and apoptosis

resistance (10–14). ILK upregulation is observed in

various types of cancer, such as prostate and colorectal cancer,

and demonstrates significant associations with tumor progression

and poor prognosis (15,16). A previous study demonstrated that

ILK knockdown induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by

decreasing AKT activity (15). Our

previous research also revealed that overexpression of ILK is

associated with perineural invasion, local recurrence and distant

metastasis in SACC (17). Moreover,

ILK levels are associated with the expression of EMT markers,

suggesting its involvement in EMT regulation (16). However, the precise molecular

mechanism remains unclear.

S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4), a member

of the S100 protein family, exerts its functions in a

calcium-dependent manner and serves both intracellular and

extracellular roles. Within cells, S100A4 expression is associated

with regulation of cell migration, apoptosis and maintenance of

stemness (18,19). In the extracellular space, S100A4

primarily stimulates pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and

induces the expression of effector molecules, including growth

factors, extracellular matrix components and MMPs, thereby

activating diverse physiological processes (20). Recognized as a promoter of tumor

progression, metastasis and poor clinical outcomes (21,22),

S100A4 is frequently upregulated in tumor cells and the tumor

microenvironment. It contributes to the pathogenesis and

advancement of multiple malignancies, such as breast and lung

cancer (23–25). Although both ILK and S100A4 have

been independently linked to the regulation of EMT (26,27),

the mechanistic connection between them remains poorly understood.

The present study aimed to determine the contribution of ILK to the

malignant phenotypes of SACC cells and the regulatory association

between ILK and S100A4 in the context of EMT and tumor invasion.

The present results could offer new perspectives on SACC

pathogenesis and reveal promising targets for therapeutic

intervention.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimen collection

A total of 52 SACC tissue samples were obtained

following approval by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated

Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical University (approval

no. 20211129004; Luzhou, China). The study enrolled 52 patients (21

male and 31 female), aged 23–84 years, who underwent radical

resection between January 2020 and December 2024 and had not

received any prior radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Patients who had

previously undergone radiotherapy or chemotherapy, or those with

ill-defined primary lesions accompanied by distant metastasis, were

excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from each

participant before tissue collection. Clinicopathological

characteristics and follow-up data were obtained from the database

of the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical

University. According to the World Health Organization

Classification of Head and Neck Tumors (28), the dominant histological pattern was

determined based on the pattern occupying the largest proportion of

the tumor, and those with a solid component >30% were classified

as the solid subtype. Tumor staging was performed according to the

8th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American

Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM classification system

(29). Normal parotid gland tissue

samples (n=5) were collected from the disease-free surgical margins

of patients undergoing parotidectomy for benign pleomorphic adenoma

at the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical

University between January 2024 and December 2024. Exclusion

criteria included prior head and neck radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

The control cohort consisted of 2 males and 3 females, aged 35 to

56 years. All tissues were reviewed and confirmed to be

histologically normal by two independent pathologists.

Cell lines and culture

The human SACC cell lines SACC-83 and SACC-LM were

obtained from the State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, West China

Hospital of Stomatology. SACC-83 and SACC-LM cell lines are derived

from ductal epithelial cells (30).

Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Vazyme)

and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator

with 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

Lentiviruses targeting ILK and S100A4 were

constructed and synthesized by OBIO Technology. Short hairpin

(sh)RNA sequences targeting ILK were inserted into the

pSLenti-U6-shRNA-CMV-EGFP-F2A-Puro-WPRE silencing vector. S100A4

sequences were cloned into the

pSLenti-EF1-EGFP-P2A-Puro-CMV-S100A4-3XFLAG-WPRE overexpression

vector. The negative control lentivirus was obtained from OBIO

Technology. Lentiviral particles were harvested at 48 and 72 h

after transfecting the recombinant vectors into 293T cells (ATCC).

SACC-83 and SACC-LM cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a

density of 5×104 cells per well and cultured at 37°C for

24 h until 70% confluence. Cells were then transduced with

lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 60 in the presence of

5 µg/ml Polybrene Plus (OBIO Technology). Following 72 h

transfection at 37°C, 2 µg/ml puromycin (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) was introduced for selection to

establish stably transfected cell lines. Subsequent experiments

utilized stable cells that were cultured for 5–7 days

post-selection and maintained within five passages of transfection.

The sequences of ILK-targeting shRNAs were as follows: shRNA-1,

5′-CCGTAGTGTAATGATTGATGA-3′; shRNA-2, 5′-CGACCCAAATTTGACATGATT-3′

and shRNA-3, 5′-GCAATGACATTGTCGTGAAGG-3′. Untreated cells were

defined as the control group (CON). Cells transfected with a

scramble non-targeting shRNA lentivirus served as the negative

control for the ILK knockdown experiment (NC-ILK), and cells

transfected with an empty vector lentivirus served as the negative

control for the S100A4 overexpression experiment (NC-S100A4).

Cell proliferation assay

SACC cells in the logarithmic growth phase were

trypsinized and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of

3×103 cells/well (n=5/group). After 24 h incubation at

37°C, Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 reagent (Dojindo Laboratories,

Inc.) was administered at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h. Optical

density at 450 nm following 1 h incubation at 37°C was measured to

quantify cell proliferation.

Colony formation assay

SACC cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density

of 700 cells/well and cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium at 37°C

under 5% CO2 for 14 days, with the medium (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) replaced every 48 h. Colonies (defined as

cell clusters containing ≥50 cells) were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, stained with 0.1%

crystal violet for 15 min at room temperature, rinsed with PBS, and

then imaged using a light microscope. Colony counting was performed

automatically using ImageJ (v1.54, National Institutes of

Health).

Cell cycle analysis

SACC cells (5×105) were fixed in 75%

ethanol at −20°C overnight. Cells were treated with RNase A (50

µg/ml at 37°C for 30 min) and stained with PI (5 µl; 4°C for 30 min

in the dark). Cell cycle distribution was analyzed using a flow

cytometer (BD FACSCalibur), and data were processed with FlowJo

software (v10.8, FlowJo LLC).

Wound healing assay

SACC cells (2×106 cells/well) were

cultured at 37°C for 24 h in 6-well plates until >95%

confluency. The monolayers were scratched using a sterile pipette

tip and incubated at 37°C in serum-free medium. Images were

captured at 0, 12 and 24 h using an inverted light microscope

(Olympus GX53). The wound area was quantified using ImageJ software

(v1.54, National Institutes of Health) to evaluate migration.

Transwell invasion assay

SACC cells (5×104/insert) suspended in

serum-free RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

were seeded into the upper chamber of Matrigel-coated Transwell

inserts (Corning, Inc.). The lower chamber was filled with medium

containing 10% FBS (Vazyme) as a chemoattractant. Following 48 h

incubation at 37°C, non-invading cells were removed and invaded

cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room

temperature, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min at room

temperature, and then imaged using a light microscope. A total of

five randomly selected fields per membrane were analyzed using

ImageJ software (v1.54, National Institutes of Health).

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from SACC cells using

RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (AbMole

Bioscience). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay

(Vazyme). Equal amounts of protein (30 µg/lane) were separated by

10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Following blocking

with 5% skimmed milk for 2 h at room temperature, membranes were

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against ILK

(1:1,000, Abcam; cat. no. ab76468), S100A4 (1:5,000, Proteintech

Group, Inc.; cat. no. 16105-1-AP), E-cadherin (cat. no. ET1607-75),

N-cadherin (cat. no. ET1607-37), Snail (cat. no. ER1706-22), GSK-3β

(cat. no. ET1607-71) and phosphorylated (p-)GSK-3β (all 1:1,000;

all HuaBio; cat. no. ET1607-60). Membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:20,000; HuaBio; cat. no.

HA1023) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized

using ECL reagents (Biosharp Life Sciences) and analyzed with

ImageJ, using GAPDH (1:5,000, HuaBio; cat. no. HA721136) as the

internal control.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and RNA integrity was confirmed

using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. RNA libraries were prepared

using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep kit (cat. no. #7530; New

England Biolabs) and subjected to paired-end sequencing on an

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Gene Denovo) with a 150 bp read

length and a 20 pM loading concentration. To ensure high-quality

data for assembly and analysis, raw reads were filtered using fastp

v0.18.0 (31) to remove adapters

and low-quality bases, yielding high-quality clean reads.

Bioinformatics analysis

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed

using the Omicsmart platform (omicsmart.com), applying false

discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 and absolute fold-change >2. Gene

Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed to identify signaling

pathways and molecular functions significantly enriched in the gene

expression profile. EMT-associated gene sets were obtained from

EMTome (emtome.org). Functional associations were explored by

construction of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks using

the STRING database (string-db.org).

Immunohistochemistry and HE

staining

Fresh tissue was fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h at

room temperature and paraffin-embedded. Sections (4 µm thickness)

were deparaffinized in xylene for 20 min and rehydrated through a

graded ethanol series. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was conducted

in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 92–98°C for 10 min. After endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide, sections

were incubated with 5% normal goat serum (ZSGB-BIO; cat. no.

ZLI-9056) for 30 min at 37°C to block non-specific binding.

Subsequently, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies against ILK (1:100, Abcam; cat. no. ab76468),

S100A4 (1:100, Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 16105-1-AP),

E-cadherin (1:100; cat. no. ET1607-75), N-cadherin (1:10,000; cat.

no. ET1607-37) and Snail (1:100; cat. no. ER1706-22; all HuaBio).

After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with a

ready-to-use, enhanced horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat

anti-rabbit IgG polymer (ZSGB-BIO; cat. no. PV-9000) at 37°C for 40

min. Signal detection was carried out using DAB chromogen

(ZSGB-BIO; cat. no. ZLI-9017), and nuclei were counterstained with

hematoxylin for 3 min at room temperature. Slides were examined

under a light microscope. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ

software (v1.54, National Institutes of Health). For HE) staining,

serial sections were prepared from the same paraffin-embedded

tissue blocks. Briefly, after standard deparaffinization and

rehydration, sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min,

followed by eosin for 2 min. The slides were then dehydrated,

cleared in xylene for morphological evaluation. A total of two

independent pathologists, blinded to the clinical data, performed

the evaluation. A total of five randomly selected fields of view

were examined under high-power magnification, and the pathologists

recorded the percentage of cells at each intensity level (0,

negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate and 3, strong) for both ILK and

S100A4. The H-score was calculated as: [0 × (% of cells with score

0) + 1 × (% of cells with score 1) + 2 × (% of cells with score 2)

+ 3 × (% of cells with score 3)] (32).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

version 27.0 (IBM Corp.). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of at

least three independent biological replicates. The normality of

data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Associations between S100A4 expression and clinicopathological

features were evaluated using the independent samples unpaired

t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The

correlation between ILK and S100A4 expression was validated using

Spearman correlation analysis. Graphs and data visualizations were

generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (Dotmatics, Inc.).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

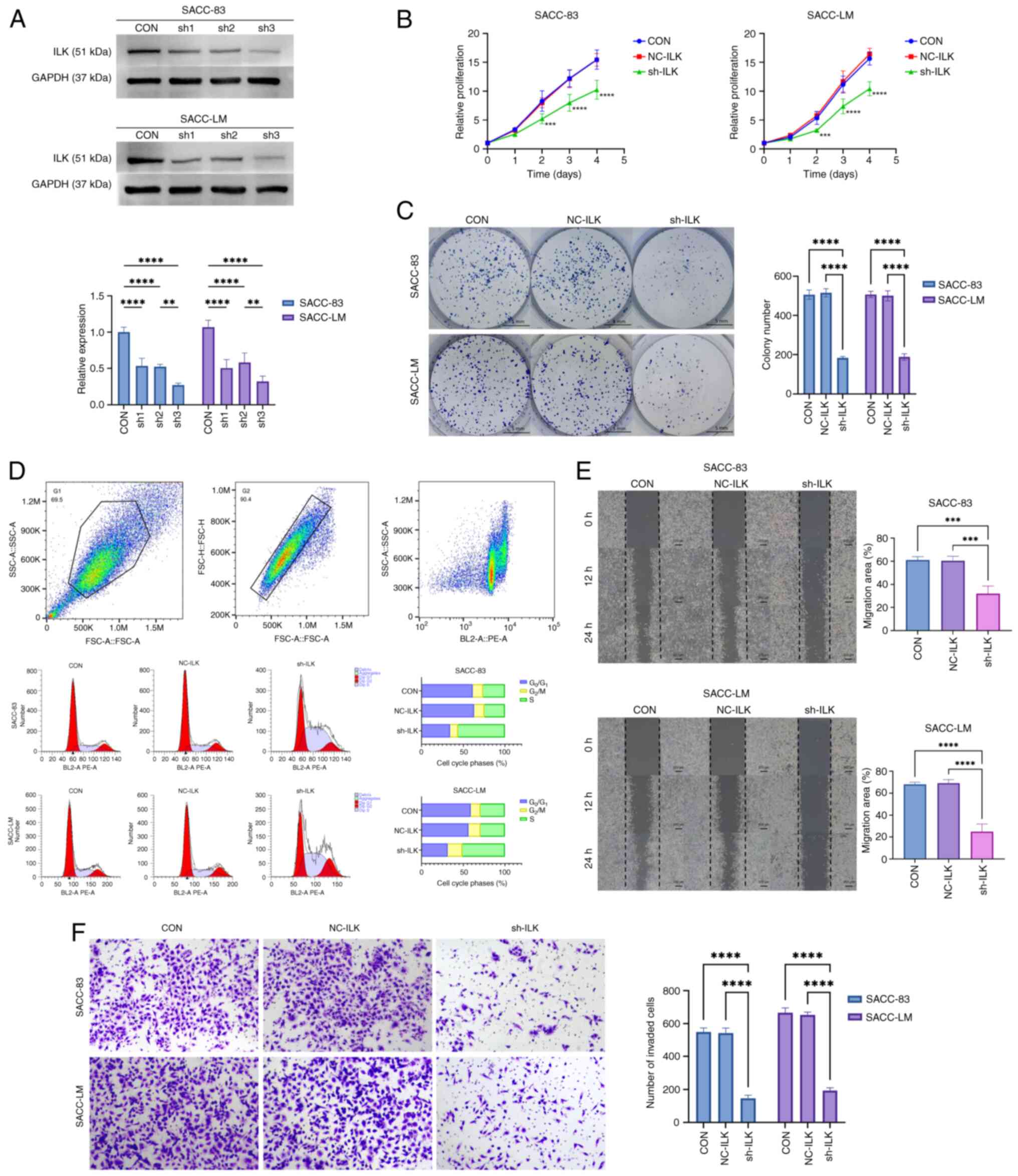

Knockdown ILK suppresses malignant

phenotypes in SACC cells

To investigate the biological function of ILK in

SACC cells, shRNA was used to stably knock down ILK expression. The

shRNA-3 sequence demonstrated the best knockdown efficiency, as

confirmed by western blotting, and was selected for subsequent

functional experiments (Fig. 1A).

ILK knockdown markedly suppressed cell proliferation, as

demonstrated by CCK-8 assay (Fig.

1B), and decreased the colony-forming ability of SACC cells

(Fig. 1C), compared with both the

CON and NC groups. Flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle

indicated a decreased G1 and an increased S population in

ILK-knockdown cells (Fig. 1D),

suggesting an enhanced G1 to S transition and an S phase blockade,

which hindered cellular DNA replication. In addition, wound healing

(Fig. 1E) and Transwell invasion

assays (Fig. 1F) showed that

ILK-knockdown cells exhibited significantly decreased migratory and

invasive capacities. Together, these findings indicated ILK was a

key regulator of SACC cell proliferation, colony formation,

migration and invasion, highlighting its potential role in

promoting tumor progression.

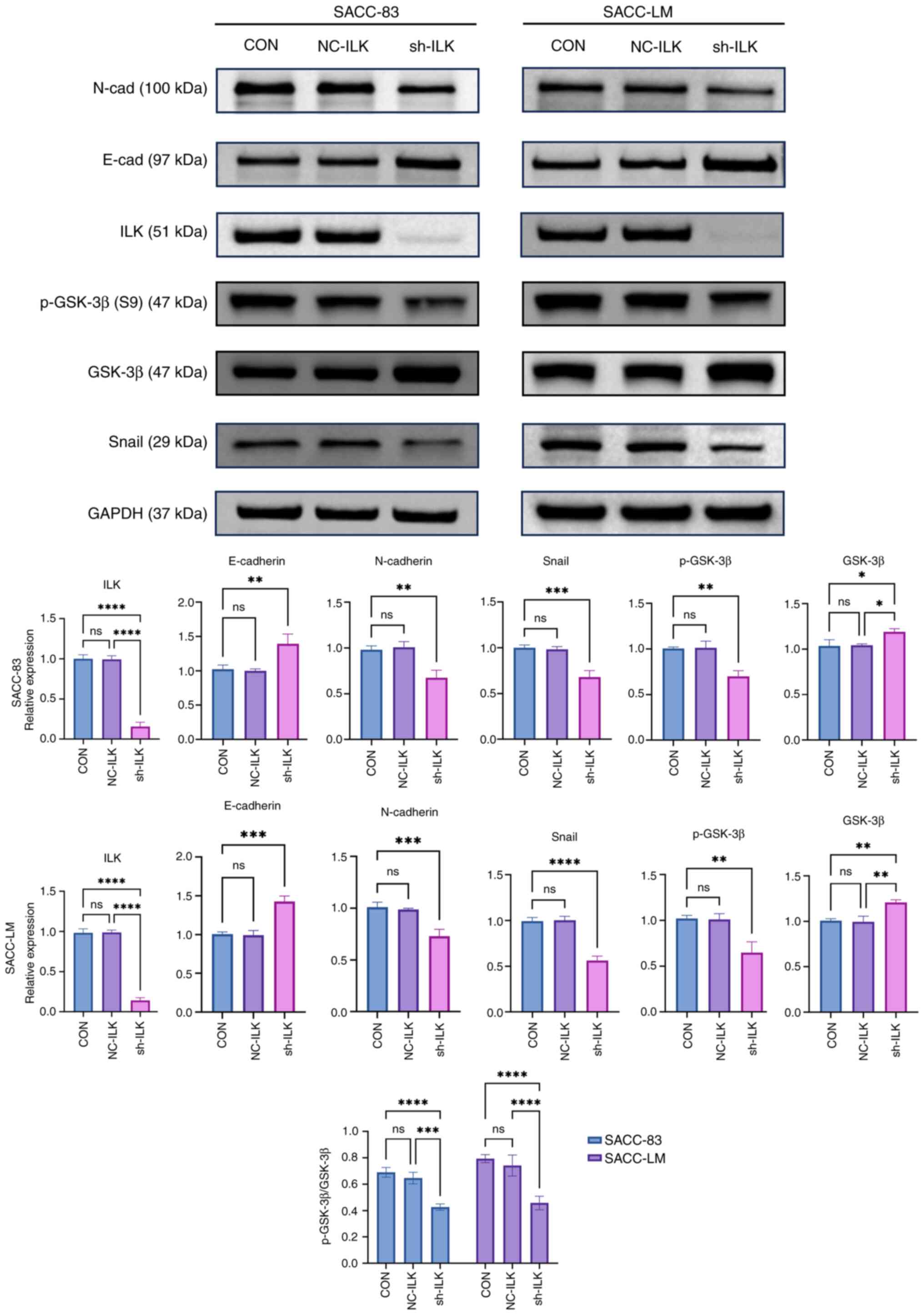

ILK regulates EMT progression in SACC

cells via the GSK-3β/Snail signaling pathway

EMT is characterized by the downregulation of the

epithelial marker E-cadherin and upregulation of the mesenchymal

marker N-cadherin; this is primarily controlled by transcription

factors (6). Building on previous

findings demonstrating a correlation between ILK and EMT markers in

SACC (14), the present study

examined the expression of key EMT markers following ILK knockdown.

ILK knockdown significantly increased E-cadherin expression while

decreasing N-cadherin and the transcription factor Snail (Fig. 2). GSK-3β regulates the expression of

Snail protein via phosphorylation, thereby modulating EMT (33). ILK knockdown significantly decreased

the ratio of p-GSK-3β to total GSK-3β. These results suggest that

ILK may modulate EMT in SACC cells via the GSK-3β/Snail pathway,

and that its inhibition could effectively block this process.

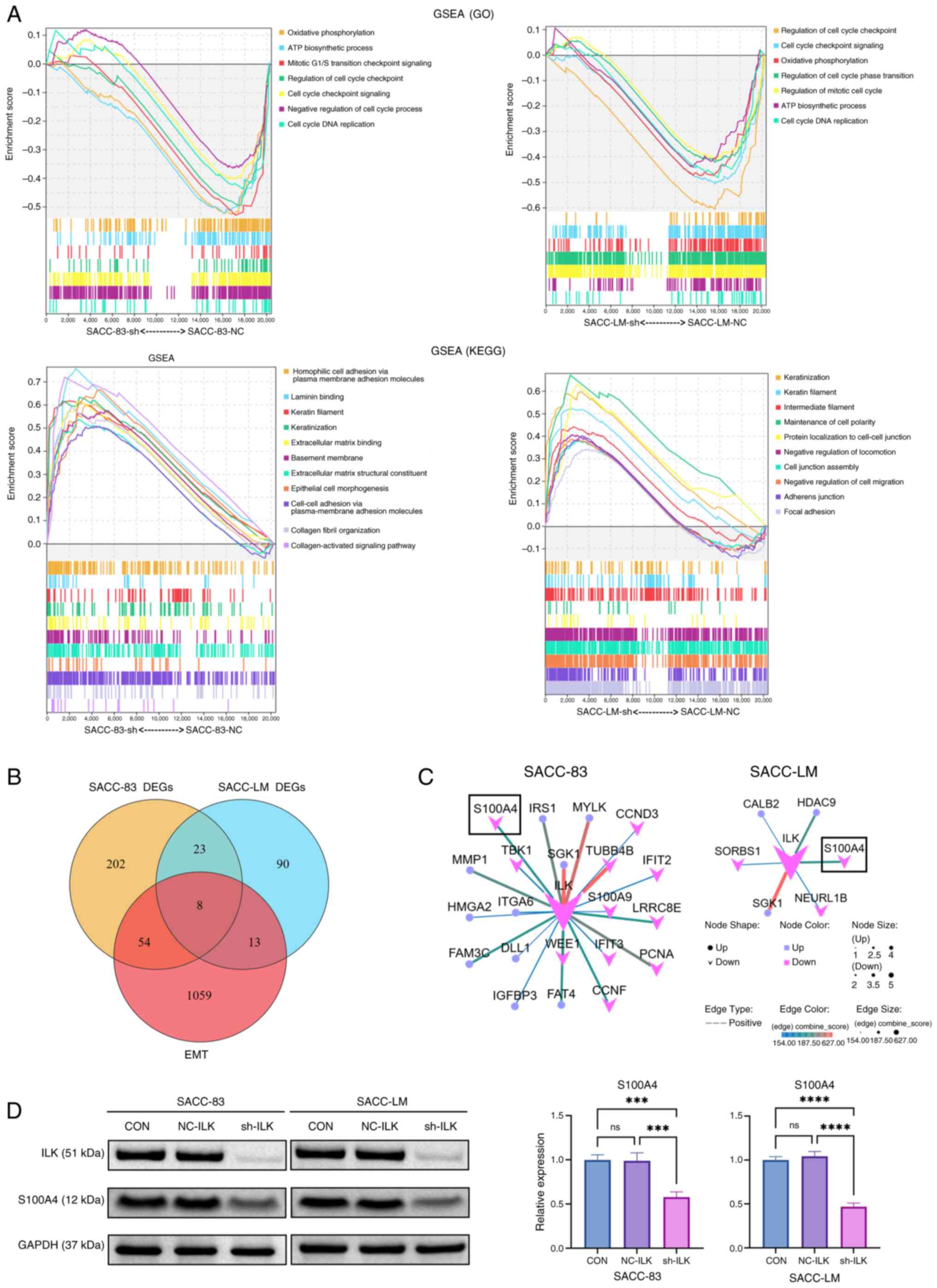

ILK as a key regulator of EMT in

SACC

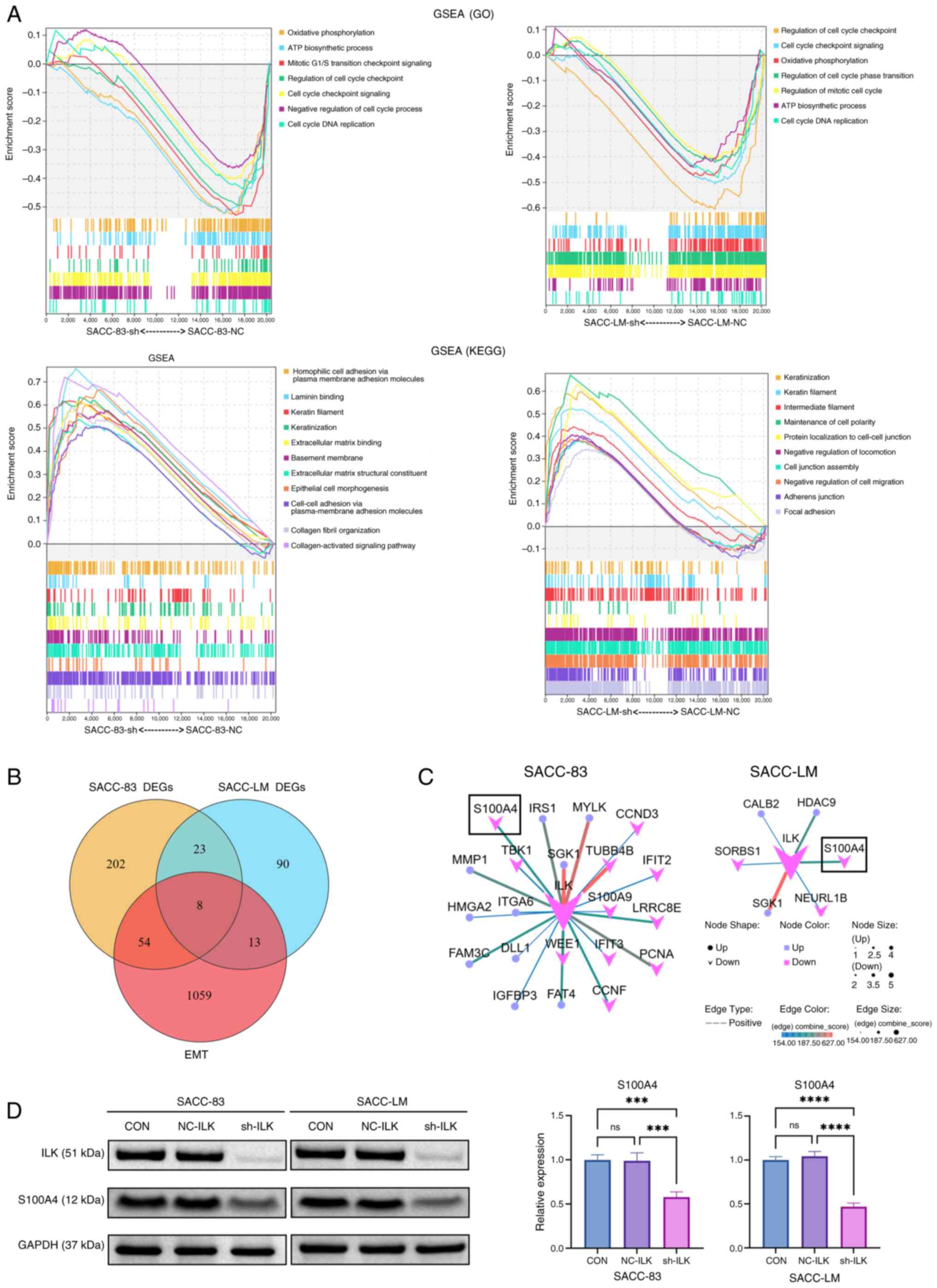

RNA sequencing was conducted on ILK-knockdown SACC

cells. Principal component analysis confirmed high reproducibility

among biological replicates (Fig.

S1A). Analysis of differential gene expression revealed 288

DEGs in SACC-83 cells and 134 in SACC-LM cells (Fig. S1B). The successful knockdown of ILK

was confirmed in both cell lines (Fig.

S1C). Additionally, a heatmap was generated to visualize the

hierarchical clustering of the top 50 DEGs, as ranked by FDR

(Fig. S1D).

GSEA revealed that ILK knockdown led to the

downregulation of cell cycle-associated pathways and enrichment of

pathways associated with epithelial phenotypes in both SACC-83-SH

and SACC-LM-SH cells (Fig. 3A).

Notably, the upregulated pathways showed negative correlations with

EMT signatures, providing direct evidence of EMT suppression. In

addition, pathways involving negative regulators of cell migration

and motility were enriched in SACC-LM-SH cells. These coordinated

transcriptomic changes suggested that ILK depletion enhanced

intercellular adhesion and suppressed cell motility, consistent

with in vitro findings.

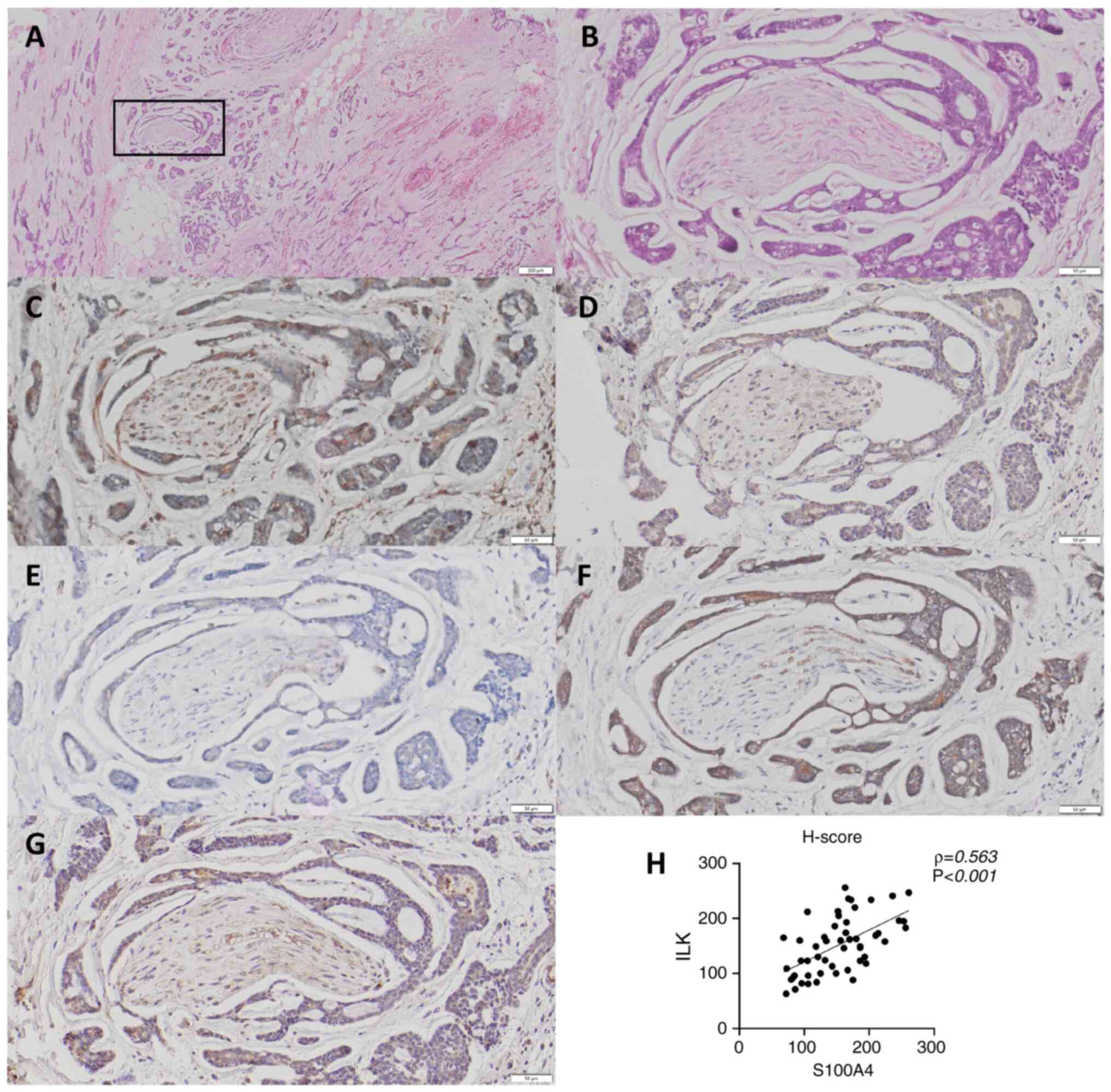

| Figure 3.Bioinformatics profiling and western

blotting identified S100A4 as a downstream effector of ILK. (A)

GSEA (P<0.05, false discovery rate <0.25) revealed that ILK

knockdown downregulated cell cycle pathways while upregulating

epithelial phenotype-associated pathways. (B) Venn diagram analysis

identified eight overlapping genes between DEGs and 1,153 EMT-core

genes from the EMTome database: CFH, CPA4, FST, ANGPTL2, LUM,

ADGRF1, ILK and S100A4. (C) Protein-protein interaction network

constructed via STRING database highlighted ILK as the central hub

node. (D) Western blot analysis validated that ILK knockdown

downregulated the protein expression of S100A4 in both cell lines.

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns not significant; ILK,

integrin-linked kinase; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; DEG,

differentially expressed gene; CFH, Complement Factor H; CPA,

Carboxypeptidase A; FST, Follistatin; ANGPTL, Angiopoietin-like

Protein; LUM, Lumican; ADGRF, Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor

F; NC, negative control; CON, blank control; sh, short hairpin;

EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG,

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; SACC, salivary adenoid

cystic carcinoma. |

S100A4 is a key downstream effector of

ILK in EMT regulation

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying

ILK-mediated EMT in SACC, the present study integrated DEGs from

two distinct SACC cell lines with 1,153 experimentally validated

EMT core genes from the EMTome database (34). Venn diagram analysis revealed eight

overlapping candidate genes: Complement Factor H), CPA4

(Carboxypeptidase A4), FST (Follistatin), ANGPTL2

(Angiopoietin-like Protein 2), LUM (Lumican), ADGRF1 (Adhesion G

protein-coupled receptor F1), ILK and S100A4 (Fig. 3B). PPI network analysis using the

STRING database highlighted S100A4 as a significantly

co-downregulated gene in ILK-knockdown cells (Fig. 3C). These findings were validated by

western blot analysis, which confirmed that S100A4 expression

markedly decreased following ILK knockdown in both SACC cell lines

(Fig. 3D).

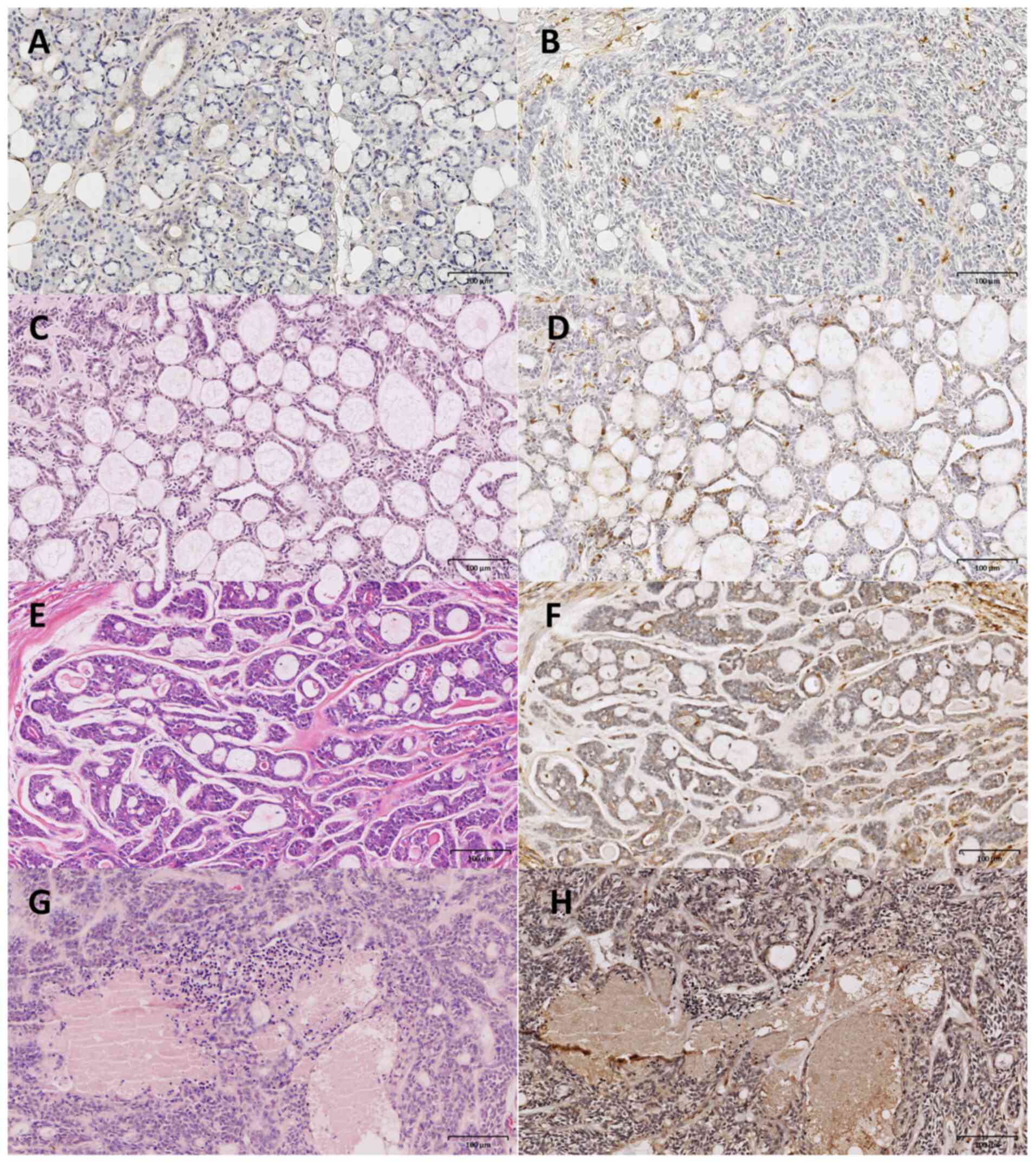

S100A4 expression is associated with

aggressive clinicopathological features and ILK expression in

SACC

S100A4 expression was nearly undetectable in the

acinar cells of normal salivary glands (Fig. 4A). Among 52 SACC specimens, 39 cases

exhibited S100A4 positivity, while 13 cases demonstrated no

observable S100A4 expression (Fig.

4B). By contrast, S100A4 expression was observed in both

tumor-derived myoepithelial (Fig. 4C

and D) and ductal epithelial cells (Fig. 4E and F), particularly in the solid

subtype of SACC, which is associated with the worse prognosis

(Fig. 4G and H). S100A4 expression

showed no significant association with patient age, sex, primary

tumor location or maximal tumor diameter (Table I). By contrast, S100A4 levels were

significantly associated with clinicopathological markers of

aggressive disease. Tumors classified as advanced stage (III/IV)

demonstrated significantly higher S100A4 expression compared with

early-stage (I/II) cases. Similarly, the solid histological subtype

exhibited stronger S100A4 positivity than either tubular or

cribriform subtypes. Furthermore, cases with perineural invasion

presented more intense staining of S100A4. These findings

demonstrated an association between S100A4 expression and adverse

clinicopathological features, underscoring its potential value as a

prognostic biomarker for assessing tumor aggressiveness in

SACC.

| Table I.Association between S100A4 expression

and clinicopathological features of patients with salivary adenoid

cystic carcinoma. |

Table I.

Association between S100A4 expression

and clinicopathological features of patients with salivary adenoid

cystic carcinoma.

| Clinicopathological

feature | Cases (n=52) | Mean S100A4

expression | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

≤60 | 29 | 148.0±48.4 | 0.463 |

|

>60 | 23 | 158.8±56.3 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

Male | 21 | 151.2±54.0 | 0.861 |

|

Female | 31 | 153.8±51.1 |

|

| Tumor site |

|

|

|

| Minor

salivary gland | 25 | 151.5±52.5 | 0.863 |

| Major

salivary gland | 27 | 154.0±52.1 |

|

| Tumor diameter,

cm |

|

|

|

| ≤2 | 18 | 161.4±37.3 | 0.207 |

| >2,

≤4 | 23 | 140.1±42.4 |

|

|

>4 | 11 | 165.2±61.5 |

|

| Clinical stage |

|

|

|

|

I+II | 27 | 134.1±42.9 | 0.002 |

|

III+IV | 25 | 173.0±41.1 |

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

Tubulara,b | 17 | 140.7±37.7 | 0.023 |

|

Cribriformc | 21 | 143.7±45.8 |

|

|

Solid | 14 | 181.1±46.1 |

|

| Perineural

invasion |

|

|

|

|

Positive | 24 | 185.4±37.6 | <0.001 |

|

Negative | 28 | 124.8±32.1 |

|

ILK expression was undetectable in normal salivary

gland tissue, with the exception of partial immunoreactivity in

ductal epithelial cells (17). By

contrast, S100A4 and ILK expression was observed in the cytoplasm

of tumor cells as well as in surrounding stromal cells of SACC

tissue. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that tumor cells at

the invasive front surrounding nerves frequently exhibited a

spindle-shaped or fusiform morphology (Fig. 5A and B), accompanied by enhanced

expression of S100A4 (Fig. 5C), ILK

(Fig. 5D), N-cadherin (Fig. 5F) and Snail (Fig. 5G), along with decreased expression

of E-cadherin (Fig. 5E).

Immunohistochemical evaluation using H-score assessment

demonstrated a significant positive correlation between S100A4 and

ILK expression in tumor tissue (ρ=0.563; Fig. 5H).

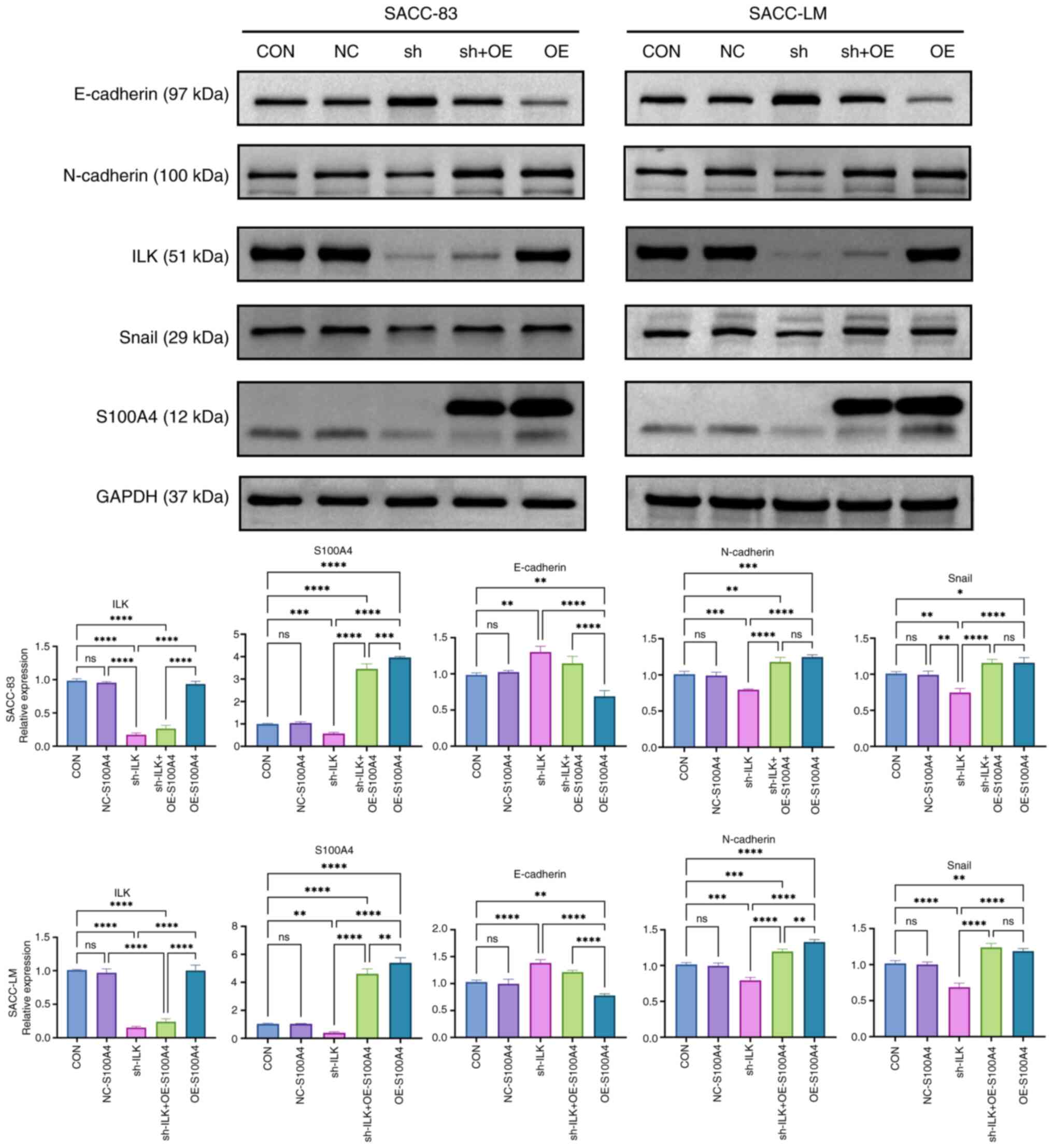

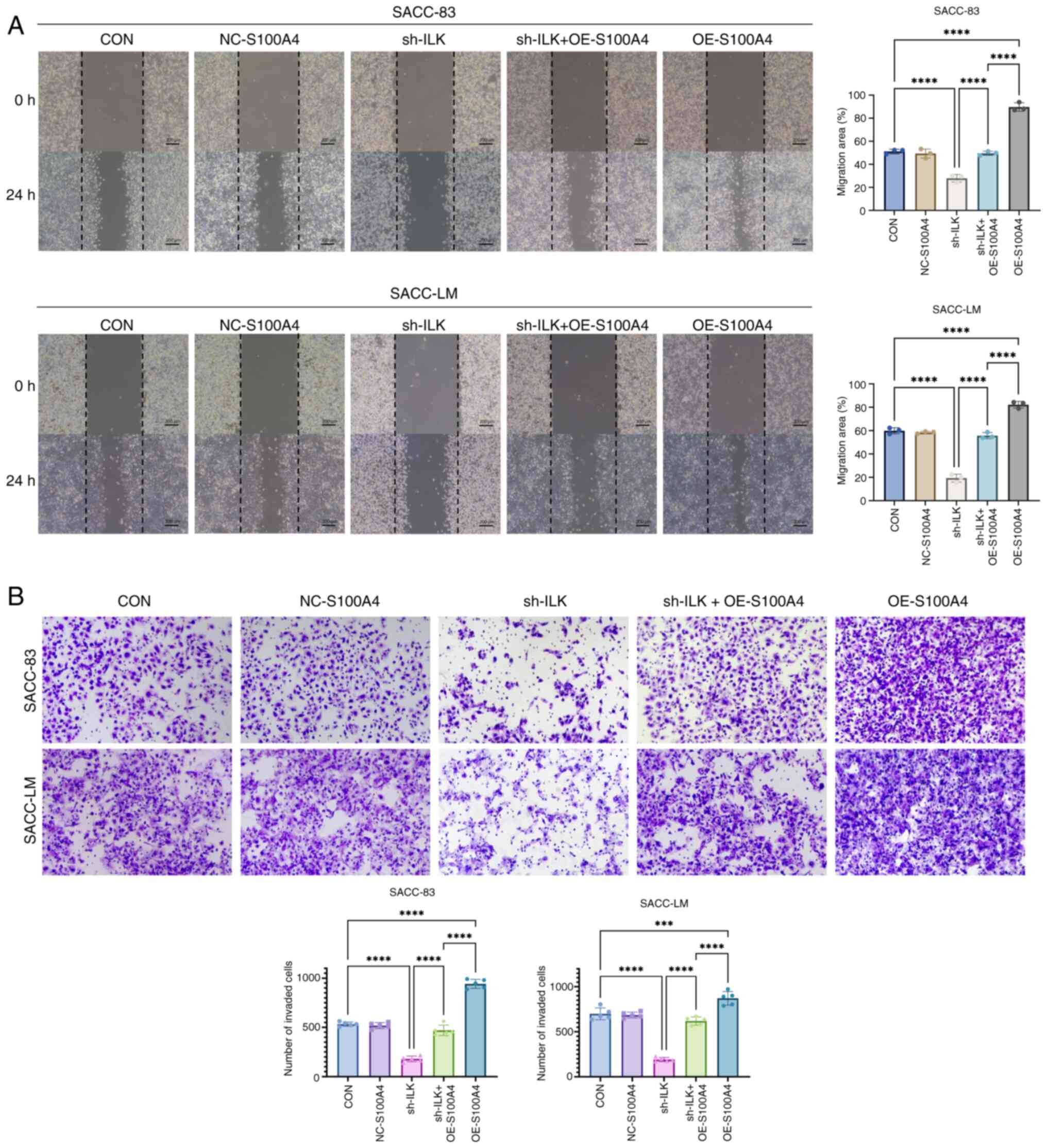

S100A4 mediates ILK-regulated EMT

progression via Snail restoration

To elucidate the regulatory association between ILK

and S100A4, the present study established cell models with combined

ILK knockdown and S100A4 overexpression. Western blot analysis of

EMT markers demonstrated that S100A4 overexpression led to

decreased E-cadherin and elevated N-cadherin levels, effectively

reversing the suppression of EMT caused by ILK knockdown (Fig. 6). Notably, the expression of Snail

protein was restored, suggesting S100A4 may regulate Snail

expression. Functional assays demonstrated that S100A4

overexpression enhanced both the migratory and invasive

capabilities of SACC cells and effectively reversed the inhibitory

effects caused by ILK depletion (Fig.

7A and B). In summary, ILK knockdown may inhibit the

phosphorylation of GSK-3β, leading to downregulation of S100A4 and

Snail expression, which decreases N-cadherin and increases

E-cadherin levels. Overexpression of S100A4 restored Snail

expression and re-induced the EMT phenotype, thereby attenuating

the inhibitory effect of ILK knockdown on EMT progression.

Discussion

Salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma accounts for ~1%

of all head and neck malignancies (35,36).

Although it typically exhibits an indolent growth pattern, the

long-term prognosis for SACC remains poor (37). Once metastasis occurs, the 10-year

survival rate is 10%. EMT in SACC is associated with solid subtype

(38), tumor progression,

perineural invasion, recurrence and distant metastasis (39). Although it is challenging to define

EMT features in SACC using HE staining alone, the present study

demonstrated that tumor cells at the perineural invasion front

frequently exhibited a spindle-shaped morphology, accompanied by

decreased E-cadherin expression and increased expression of

N-cadherin and Snail. The present study further demonstrated that

ILK knockdown significantly attenuated the migratory and invasive

capabilities of SACC cells, concurrent with upregulated E-cadherin

expression and downregulated N-cadherin and Snail levels. These

changes were consistent with the results of our previous

clinicopathological study (17).

These findings suggested that ILK may serve a key role in promoting

EMT in SACC.

To identify the mechanism by which ILK participates

in EMT, the present study conducted transcriptomic screening and

identified S100A4 as a key target. In vitro results were

supported by GSEA. Although previous studies have demonstrated the

involvement of S100A4 in the invasion and metastasis of numerous

types of cancer (40,41), to the best of our knowledge, its

specific role in SACC has not been reported. The present

clinicopathological analysis revealed that high S100A4 expression

was significantly associated with advanced clinical stage, solid

histological subtype and perineural invasion, suggesting its

potential as a molecular marker of aggressive tumor behavior. While

both ILK and S100A4 were nearly undetectable in normal salivary

gland tissue, consistent with previous reports (17,42),

their expression in SACC tumors was implicated in the promotion of

local and perineural invasion.

To clarify the role of S100A4 in ILK-driven EMT, the

present study examined the expression of S100A4 in ILK-knockdown

cell lines. S100A4 expression was significantly downregulated in

ILK-knockdown cells. When S100A4 expression was induced in

ILK-knockdown cells, the expression of Snail and N-cadherin was

markedly enhanced, while E-cadherin expression was downregulated.

The impaired invasion and migration phenotypes of SACC cells were

restored. These findings suggested that S100A4 serves a key role in

ILK-driven EMT. Studies have indicated that ILK promotes the

stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin via the GSK-3β

pathway (43,44). β-catenin that enters the nucleus

forms a complex with T cell factor 4; this complex specifically

binds the promoter region of the S100A4 gene, thereby enhancing its

expression (45). Other studies

have revealed that the expression of S100A4 in cancer is

significantly associated with Snail family proteins (46) and regulates their expression

(47). ILK may regulate the

expression of S100A4 and Snail by modulating the phosphorylation of

GSK-3β, thereby influencing EMT.

The most prominent molecular characteristic of SACC

is the aberrant activation of the MYB proto-oncogene. A total of

~86% of cases harbor the characteristic MYB-nuclear factor IB gene

fusion (48). Research has shown

that MYB upregulation contributes to EMT, thereby promoting

invasion and metastasis in SACC (49). Although the association between MYB

and ILK remains unclear, MYB Proto-Oncogene Like 1) carried by

small extracellular vesicles upregulates the expression of integrin

proteins ITGB3 (Integrin Subunit Beta 3) and ITGAV (Integrin

Subunit Alpha V) (50). As a key

molecule in the integrin signaling pathway, ILK may also be

regulated by MYB. MYB and ILK modulate the expression of the

adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1)

(50,51). ICAM-1 serves a crucial role in

mediating EMT, highlighting its role in tumor metastasis (52). In summary, the integrin signaling

pathway may serve as a key bridge connecting the functions of MYB

and S100A4, and the synergistic mechanism between MYB and the

ILK-S100A4 axis requires further exploration.

Through clinicopathological correlation analysis and

in vitro experiments, the present study demonstrated the

functional role of the ILK-S100A4-Snail signaling axis in promoting

EMT in SACC. However, the specific molecular mechanisms by which

ILK regulates S100A4/Snail require further validation through in

vivo models and pharmacological approaches. Furthermore, the

prognostic value of ILK and S100A4 for survival in patients with

SACC remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, S100A4 represents a potential

biomarker for predicting aggressive behavior in SACC. ILK may

facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis by modulating S100A4/Snail

expression via GSK-3β, leading to EMT. These findings suggest dual

targeting of ILK and S100A4 may offer synergistic therapeutic

benefits and represent a promising strategy to inhibit tumor

invasion in SACC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Oral &

Maxillofacial Reconstruction and Regeneration of Luzhou Key

Laboratory (Luzhou, China) for providing the experimental site.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Scientific Research

Project of Southwest Medical University (grant no. 2021ZKMS017),

the Scientific Research Foundation of the Affiliated Stomatological

Hospital of Southwest Medical University (grant no. 2021BS01) and

Southwest Medical University Stomatology Special Program (grant

nos. 2024KQZX18 and 2024KQZX20).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession

number PRJNA1320937 or at the following URL: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1320937.

Authors' contributions

YY conceived the study, designed and performed

experiments and wrote the manuscript. JL designed the experiments.

LY constructed figures and performed experiments. YL analyzed data.

KG performed the experiments. DZ conceived the study and edited the

manuscript. YY and DZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board and Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Stomatological

Hospital of Southwest Medical University (approval no. 20211129004;

Luzhou, China). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all

patients before the tissue collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

van der Wal JE, Becking AG, Snow GB and

van der Waal I: Distant metastases of adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the salivary glands and the value of diagnostic examinations during

follow-up. Head Neck. 24:779–783. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

da Cruz Perez DE, de Abreu Alves F, Nobuko

Nishimoto I, de Almeida OP and Kowalski LP: Prognostic factors in

head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 42:139–146.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gao M, Hao Y, Huang MX, Ma DQ, Luo HY, Gao

Y, Peng X and Yu GY: Clinicopathological study of distant

metastases of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Int J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 42:923–928. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kokemueller H, Eckardt A, Brachvogel P and

Hausamen JE: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck-a 20

year experience. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 33:25–31. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Avery CM, Moody AB, McKinna FE, Taylor J,

Henk JM and Langdon JD: Combined treatment of adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the salivary glands. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

29:277–279. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brabletz T, Kalluri R, Nieto MA and

Weinberg RA: EMT in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:128–134. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu Y, Chen L, Jiang D, Luan L, Huang J,

Hou Y and Xu C: HER2 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

through regulating osteopontin in gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract.

227:1536432021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Dongre A and Weinberg RA: New insights

into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:69–84. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Naves MA, Requião-Moura LR, Soares MF,

Silva-Júnior JA, Mastroianni-Kirsztajn G and Teixeira VPC: Podocyte

Wnt/ß-catenin pathway is activated by integrin-linked kinase in

clinical and experimental focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J

Nephrol. 25:401–409. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Legate KR, Montañez E, Kudlacek O and

Fässler R: ILK, PINCH and parvin: The tIPP of integrin signalling.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 7:20–31. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jia YY, Yu Y and Li HJ: POSTN promotes

proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal cell

carcinoma through ILK/AKT/mTOR pathway. J Cancer. 12:4183–4195.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tsirtsaki K and Gkretsi V: The focal

adhesion protein integrin-linked kinase (ILK) as an important

player in breast cancer pathogenesis. Cell Adh Migr. 14:204–213.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu S, Jin Z, Cao M, Hao D, Li C, Li D and

Zhou W: Periostin regulates osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells

from ovariectomized rats through actions on the ILK/Akt/GSK-3β

axis. Genet Mol Biol. 44:e202004612021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Akrida I, Nikou S, Gyftopoulos K, Argentou

M, Kounelis S, Zolota V, Bravou V and Papadaki H: Expression of EMT

inducers integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and ZEB1 in phyllodes breast

tumors is associated with aggressive phenotype. Histol Histopathol.

33:937–949. 2018.

|

|

15

|

Yuan Y, Xiao Y, Li Q, Liu Z, Zhang X, Qin

C, Xie J, Wang X and Xu T: In vitro and in vivo effects of short

hairpin RNA targeting integrin-linked kinase in prostate cancer

cells. Mol Med Rep. 8:419–424. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tsoumas D, Nikou S, Giannopoulou E,

Champeris Tsaniras S, Sirinian C, Maroulis I, Taraviras S, Zolota

V, Kalofonos HP and Bravou V: ILK expression in colorectal cancer

is associated with EMT, cancer stem cell markers and

chemoresistance. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 15:127–141.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhao D, Yang K, Tang XF, Lin NN and Liu

JY: Expression of integrin-linked kinase in adenoid cystic

carcinoma of salivary glands correlates with epithelial-mesenchymal

transition markers and tumor progression. Med Oncol. 30:6192013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Dahlmann M, Kobelt D, Walther W, Mudduluru

G and Stein U: S100A4 in cancer metastasis: Wnt signaling-driven

interventions for metastasis restriction. Cancers (Basel).

8:592016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chow KH, Park HJ, George J, Yamamoto K,

Gallup AD, Graber JH, Chen Y, Jiang W, Steindler DA, Neilson EG, et

al: S100A4 is a biomarker and regulator of glioma stem cells that

is critical for mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma. Cancer Res.

77:5360–5373. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bresnick AR, Weber DJ and Zimmer DB: S100

proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:96–109. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Grigorian M, Andresen S, Tulchinsky E,

Kriajevska M, Carlberg C, Kruse C, Cohn M, Ambartsumian N,

Christensen A, Selivanova G and Lukanidin E: Tumor suppressor p53

protein is a new target for the metastasis-associated Mts1/S100A4

protein: Functional consequences of their interaction. J Biol Chem.

276:22699–22708. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Semov A, Moreno MJ, Onichtchenko A,

Abulrob A, Ball M, Ekiel I, Pietrzynski G, Stanimirovic D and

Alakhov V: Metastasis-associated protein S100A4 induces

angiogenesis through interaction with Annexin II and accelerated

plasmin formation. J Biol Chem. 280:20833–20841. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pedersen KB, Nesland JM, Fodstad Ø and

Maelandsmo GM: Expression of S100A4, E-cadherin, alpha- and

beta-catenin in breast cancer biopsies. Br J Cancer. 87:1281–1286.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang J, Gu Y, Liu X, Rao X, Huang G and

Ouyang Y: Clinicopathological and prognostic value of S100A4

expression in non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Biosci

Rep. 40:BSR202017102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fei F, Qu J, Zhang M, Li Y and Zhang S:

S100A4 in cancer progression and metastasis: A systematic review.

Oncotarget. 8:73219–73239. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhou W, Peng Z, Zhang C, Liu S and Zhang

Y: ILK-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition promotes the

invasive phenotype in adenomyosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

497:950–956. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hua T, Liu S, Xin X, Cai L, Shi R, Chi S,

Feng D and Wang H: S100A4 promotes endometrial cancer progress

through epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulation. Oncol Rep.

35:3419–3426. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Szanto PA, Luna MA, Tortoledo ME and White

RA: Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary

glands. Cancer. 54:1062–1069. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang SH and O'Sullivan B: Overview of the

8th edition TNM classification for head and neck cancer. Curr Treat

Options Oncol. 18:402017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang L, Wang Y, Bian H, Pu Y and Guo C:

Molecular characteristics of homologous salivary adenoid cystic

carcinoma cell lines with different lung metastasis ability. Oncol

Rep. 30:207–212. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y and Gu J: fastp: An

ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics.

34:i884–i890. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA Jr,

Di Maria MV, Veve R, Bremmes RM, Barón AE, Zeng C and Franklin WA:

Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas:

Correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and

impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 21:3798–3807. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM,

Gunduz M and Hung MC: Dual regulation of Snail by

GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 6:931–940. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Vasaikar SV, Deshmukh AP, den Hollander P,

Addanki S, Kuburich NA, Kudaravalli S, Joseph R, Chang JT,

Soundararajan R and Mani SA: EMTome: A resource for pan-cancer

analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition genes and signatures.

Br J Cancer. 124:259–269. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

de Sousa LG, Jovanovic K and Ferrarotto R:

Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma: Genomic landscape and emerging

treatments. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 23:1135–1150. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ayoub N, Nozhy A, Shawki A, Hassouna A,

Ibraheem D, Elmahdy M and Amin A: Management of adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the head and neck: Experience of the national cancer

institute, Egypt. Gulf J Oncolog. 1:63–69. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Laurie SA, Ho AL, Fury MG, Sherman E and

Pfister DG: Systemic therapy in the management of metastatic or

locally recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands:

A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 12:815–824. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sangala BN, Raghunath V, Kavle P, Gupta A,

Gotmare SS and Andey VS: Evaluation of immunohistochemical

expression of E-cadherin in pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic

carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 26:65–71. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hoch CC, Stögbauer F and Wollenberg B:

Unraveling the role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in adenoid

cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands: A comprehensive review.

Cancers (Basel). 15:28862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ambartsumian N, Klingelhöfer J and

Grigorian M: The multifaceted S100A4 protein in cancer and

inflammation. Methods Mol Biol. 1929:339–365. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Mishra SK, Siddique HR and Saleem M:

S100A4 calcium-binding protein is key player in tumor progression

and metastasis: Preclinical and clinical evidence. Cancer

Metastasis Rev. 31:163–172. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Shan C, Wei J, Hou R, Wu B, Yang Z, Wang

L, Lei D and Yang X: Schwann cells promote EMT and the Schwann-like

differentiation of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cells via the

BDNF/TrkB axis. Oncol Rep. 35:427–435. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Luo L, Liu H, Dong Z, Sun L, Peng Y and

Liu F: Small interfering RNA targeting ILK inhibits EMT in human

peritoneal mesothelial cells through phosphorylation of GSK-3β. Mol

Med Rep. 10:137–144. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tan C, Costello P, Sanghera J, Dominguez

D, Baulida J, de Herreros AG and Dedhar S: Inhibition of integrin

linked kinase (ILK) suppresses beta-catenin-Lef/Tcf-dependent

transcription and expression of the E-cadherin repressor, snail, in

APC-/-human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 20:133–140. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gong N, Shi L, Bing X, Li H, Hu H, Zhang

P, Yang H, Guo N, Du H, Xia M and Liu C: S100A4/TCF complex

transcription regulation drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition

in chronic sinusitis through Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling. Front

Immunol. 13:8358882022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Jian L, Zhihong W, Liuxing W and Qingxia

F: Role of S100A4 in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its molecular mechanism.

Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 37:258–265. 2015.(In Chinese).

|

|

47

|

Liang DP, Huang TQ, Li SJ and Chen ZJ:

Knockdown of S100A4 chemosensitizes human laryngeal carcinoma cells

in vitro through inhibition of Slug. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

18:3484–3490. 2014.

|

|

48

|

Persson M, Andrén Y, Moskaluk CA, Frierson

HF Jr, Cooke SL, Futreal PA, Kling T, Nelander S, Nordkvist A,

Persson F and Stenman G: Clinically significant copy number

alterations and complex rearrangements of MYB and NFIB in head and

neck adenoid cystic carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer.

51:805–817. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Xu LH, Zhao F, Yang WW, Chen CW, Du ZH, Fu

M, Ge XY and Li SL: MYB promotes the growth and metastasis of

salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 54:1579–1590.

2019.

|

|

50

|

Fu M, Gao Q, Xiao M, Li RF, Sun XY, Li SL,

Peng X and Ge XY: Extracellular vesicles containing circMYBL1

induce CD44 in adenoid cystic carcinoma cells and pulmonary

endothelial cells to promote lung metastasis. Cancer Res.

84:2484–2500. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang W, Matsukura M, Fujii I, Ito K, Zhao

JE, Shinohara M, Wang YQ and Zhang XM: Inhibition of high

glucose-induced VEGF and ICAM-1 expression in human retinal pigment

epithelium cells by targeting ILK with small interference RNA. Mol

Biol Rep. 39:613–620. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qian WJ, Yan JS, Gang XY, Xu L, Shi S, Li

X, Na FJ, Cai LT, Li HM and Zhao MF: Intercellular adhesion

molecule-1 (ICAM-1): From molecular functions to clinical

applications in cancer investigation. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev

Cancer. 1879:1891872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|