C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), is a key member

of the CC subfamily of chemokines, which was purified and

identified in 1989 by Yoshimura et al (1). CCL2 exerts chemotactic effects on

monocytes, macrophages and T lymphocytes (2), and is secreted by activated cells

through autocrine or paracrine methods. Cytokines in the tumor

microenvironment (TME), including TNFα, lipopolysaccharide, IL-1,

IL-6 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), stimulate tumor

cells to produce CCL2 (2). C-C

motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2), the main receptor of CCL2, is a

G protein-coupled receptor expressed in both immune and tumor cells

(2–4). It plays an essential role in different

aspects of tumor cell biology, including the regulation of

proliferation, angiogenesis, immune response and migration of cells

in inflammatory environments (5).

CCL2 exerts its biological effects mainly by combining with CCR2

(2,6).

Studies have found that numerous types of tumor

cells, including myeloma, breast cancer, prostate cancer and

melanoma cells, express CCR2 and secrete high levels of CCL2

(7–9). CCL2 thus promotes tumor cell

proliferation and survival through autocrine or paracrine pathways,

participating in the regulation of tumor immune tolerance, inducing

tumor angiogenesis, and promoting tumor invasion and metastasis

(10).

The ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis posited that, during

metastasis, tumor cells not only adapt to the recipient

microenvironment but also actively remodel it to facilitate

colonization (16,17). The chemokine-receptor crosstalk

represents a pivotal research frontier in tumor metastasis biology.

Its multifaceted roles include tumor cell proliferation,

chemoresistance, migratory/invasive capacity and organotropic

metastasis, alongside regulatory effects on angiogenesis and

lymphangiogenesis. Growth factors, circulatory hypoxia, antitumor

drugs and radiation therapy stimulate tumor cells to secrete more

CCL2, induce the establishment of an immunosuppressive TME through

the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis, and promote tumor progression and

metastasis. de Visser reviewed the importance of the TME in every

stage of cancer progression, including tumor initiation,

progression, invasion, infiltration, metastasis, diffusion and

growth (18). TME represents a

highly complex and dynamic ecosystem, primarily composed of three

major cellular components: myeloid cells (including

tumor-associated macrophages [TAMs], myeloid-derived suppressor

cells [MDSCs], dendritic cells [DCs], and tumor-associated

neutrophils [TANs]), lymphoid cells (such as T cells, B cells,

natural killer [NK] cells, and innate lymphoid cells [ILCs]), and

stromal components (cancer-associated fibroblasts [CAFs] and

endothelial cells) (18). While

these host-derived cells were historically dismissed as passive

bystanders in tumorigenesis, emerging evidence highlights their key

roles in driving cancer pathogenesis (18). The cellular architecture and

functional phenotype of the TME exhibit pronounced heterogeneity

dictated by primary tumor location, cancer cell-intrinsic

properties, disease stage and patient-specific factors (18). Deciphering the crosstalk among tumor

cell-autonomous signals, microenvironmental cues and systemic

regulatory networks is key for the rationale-driven design of

next-generation cancer therapeutics. The present study summarized

the role of the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis in tumor progression and

metastasis.

CCL2 orchestrates antitumor immune responses by

promoting immune cell recruitment and surveillance. In vitro

studies have shown that diverse tumor cell lines chemoattract

CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes through CCL2

secretion (19,20). For example, in a previous study of

nude mice, ovarian cancer cells engineered to express CCL2 induced

robust monocyte infiltration at the injection site, resulting in

localized tumor growth inhibition (20) Clinically, plasma CCL2 levels in

patients with pancreatic cancer have been shown to be negatively

correlated with tumor proliferation markers (21). In addition, in colorectal cancer

preclinical models (22–24), the targeted modulation of

tumor-derived chemokines enhances immune cell infiltration and

suppresses tumor progression.

CCL2 serves a pivotal role in the metastatic

cascade, particularly during epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT). Preclinical studies have shown EMT-induced cancer cells

upregulate CCL2 expression (22–25),

which in turn attracts neutrophils to the TME. While neutrophils

are traditionally associated with tumor-promoting inflammation,

evidence has highlighted their potential to exert cytotoxic effects

against cancer cells in specific contexts (26–28).

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) have two phenotypes. ‘N2’ is

known as a pro-tumorigenic phenotype, as it exerts a

pro-tumorigenic effect at the primary site by secreting oncogenic

factors, promoting primary tumor growth and angiogenesis,

increasing extracellular matrix degradation and suppressing immune

responses (29–33). ‘N1’ is an antitumorigenic phenotype.

These neutrophil phenotype switches are contingent on TGF-β

signaling, as the neutralization of TGF-β has been shown to induce

a shift from ‘N2’ pro-tumorigenic to ‘N1’ antitumorigenic

neutrophil states (31).

Tumor-entrained neutrophils suppress lung metastatic seeding via

H2O2-dependent cytotoxic mechanisms, with

tumor-derived CCL2 serving as a key mediator of granulocyte

colony-stimulating factor-stimulated neutrophil recruitment for

optimal anti-metastatic function (28). A preclinical study of mouse breast

cancer models further demonstrated that neutrophils accumulate in

the lungs prior to the arrival of metastatic cells, establishing a

pre-metastatic surveillance niche (28).

TANs exhibit dual roles in cancer progression, with

N1-polarized TANs exerting antitumor effects and N2-polarized TANs

promoting tumorigenesis. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) secrete cardiotrophin-like

cytokine factor 1 (CLCF1), which drives tumor stemness via C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 6/TGF-β and recruits immunosuppressive N2

TANs, forming a pro-tumorigenic feedback loop. Conversely, in lung

cancer, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CXCR2) inhibition shifts

TANs toward an N1 phenotype, decreasing immunosuppressive factors

(arginase 1, TGF-β) and enhancing CD8+ T-cell activity,

thereby improving antitumor immunity and chemotherapy response

(34,35). These findings highlight TAN

polarization as a critical determinant of tumor fate, suggesting

therapeutic strategies targeting N2 TANs (such asCLCF1/ERK

inhibition in HCC) or promoting N1 TANs (for example via CXCR2

blockade in lung cancer) may modulate the TME.

TILs serve as both prognostic biomarkers in cancer

progression and key effectors in immunotherapeutic responses

(26). The CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis

orchestrates TIL recruitment to the TME, while CCL2 modulates the

anti-cancer functions of T lymphocytes and dendritic cells, thereby

potentiating antitumor immunity (26).

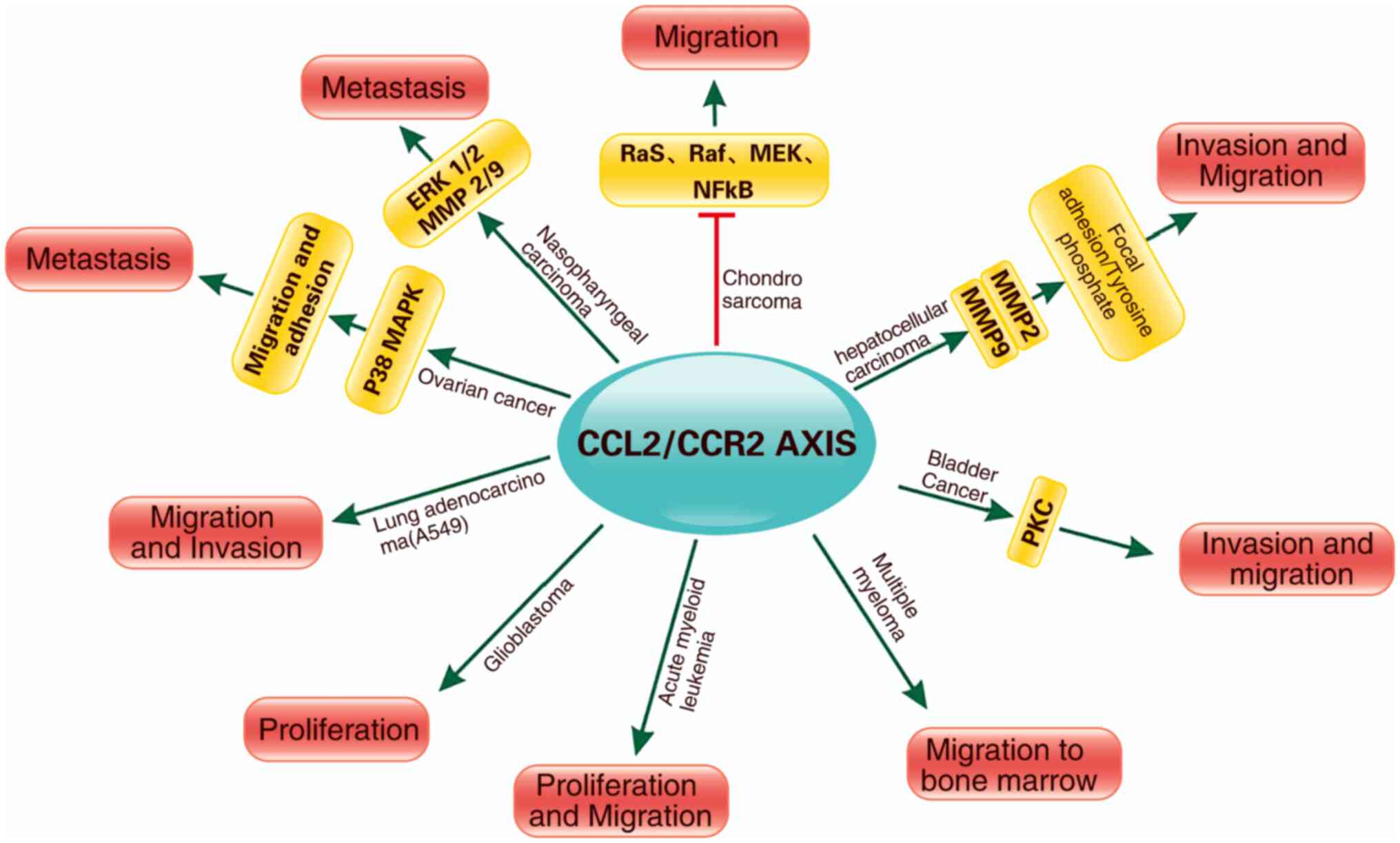

CCL2 promotes chondrosarcoma cell migration by

upregulating MMP9 expression and engaging CCR2, thereby inhibiting

Ras/Raf-1/MEK/ERK and NFκB signaling cascades (53). In HCC cell model, CCL2/CCR2

engagement triggers focal adhesion kinase tyrosine phosphorylation

at Y397, promoting the recruitment of Src family kinases and

activation of MMP2/9 through the ERK1/2 signaling cascade (54). Concurrently, calcium ion flux

mediated by CCR2 activates the calcineurin-nuclear factor of

activated T cells pathway, upregulating MMP9 transcription and

enhancing extracellular matrix degradation (55). Sustained CCL2 secretion also

polarizes tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward the M2

phenotype, fostering a pro-inflammatory milieu rich in IL-6 and

TNF-α that supports cancer cell clonal expansion (56–59).

This multifaceted signaling network has been implicated in

metastatic progression in multiple types of cancer, including

cervical and breast malignancy (56,58).

In breast cancer, the CCL2/CCR2 axis regulates cellular motility

and survival, thereby driving metastatic dissemination (60,61).

Similarly, in prostate cancer, CCL2/CCR2 signaling governs

proliferation, apoptosis resistance and invasive potential

(62). In bladder cancer, the

activation of this axis enhances migration and invasion via protein

kinase C activation and tyrosine phosphorylation, independent of

its effects on cell proliferation (63). Blockade of CCL2/CCR2 signaling

markedly impairs the bone marrow homing of multiple myeloma cells,

underscoring its role in hematological malignancy metastasis

(64). In nasopharyngeal carcinoma

(NPC), CCL2/CCR2 signaling promotes metastasis via ERK1/2-MMP2/9

pathway activation (65). In

colorectal cancer, alcohol exposure upregulates CCL2/CCR2 signaling

via the glycogen synthase kinase 3β/β-catenin pathway, facilitating

metastatic progression (66).

Epithelial ovarian cancer exploits CCL2/CCR2 signaling to promote

peritoneal dissemination, as demonstrated by the enhanced migration

and adhesion of ovarian cancer cells following CCL2 stimulation, a

process mediated by the P38 MAPK pathway (67,68).

The CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway drives the

proliferation and migration of acute myeloid leukemia cells, as

demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo studies

(69). In glioblastoma,

tumor-secreted CCL2 orchestrates monocyte recruitment, establishing

a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment that fosters neoplastic growth

(70). Leveraging this mechanistic

insight, preclinical investigation have explored CCR2 antagonists

as novel antitumor agents. For example, the pharmacological

blockade of CCR2 in lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells attenuates their

migratory and invasive capabilities (Fig. 1; Table

I) (71).

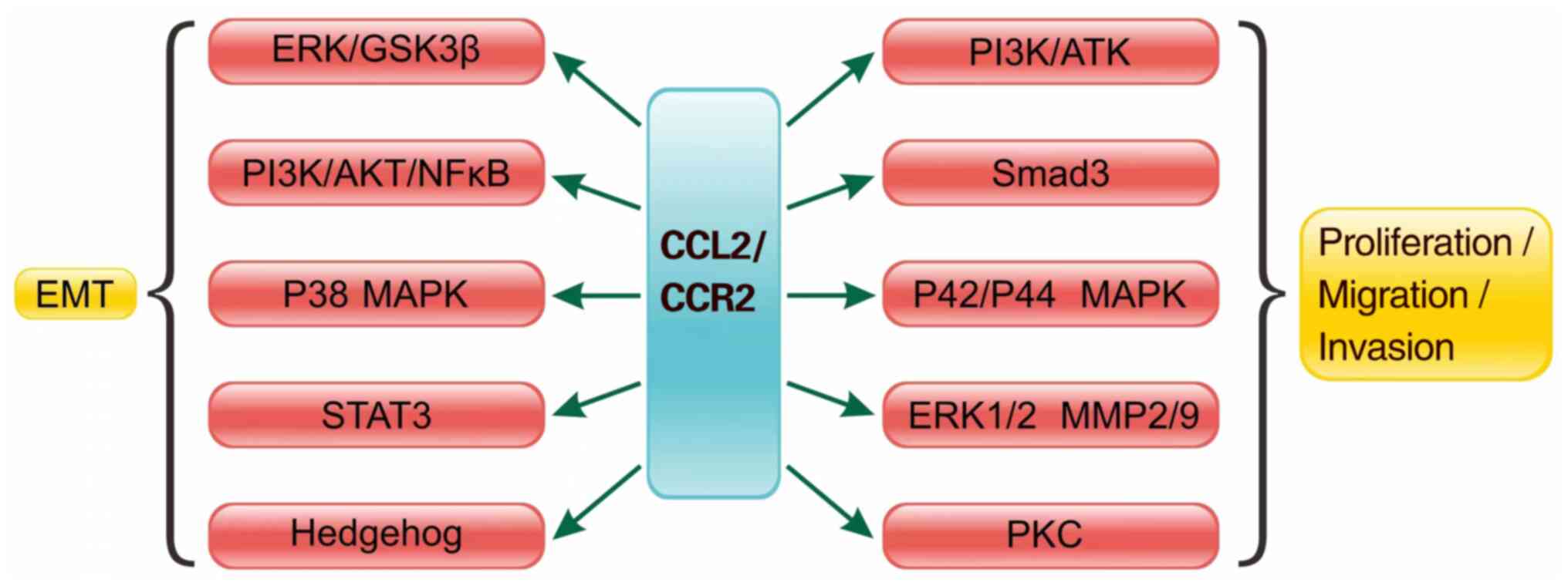

EMT is the initial step of tumor metastasis, and is

involved in the progression and metastasis of various types of

cancer (72,73). The CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis promotes

EMT in liver cancer through MMP2 (74). There is a growing body of data

describing a direct stimulatory effect of CCL2 on tumor epithelial

cells (8,75). Notably, interruption of the

CCL2/CCR2/STAT3 pathway can inhibit the EMT and migration of

prostate cancer cells, inhibiting the progression and metastasis of

prostate cancer (75). Furthermore,

the TME enhances bladder cancer metastasis by modulating estrogen

receptor (ER)β/CCL2/CCR2 EMT/MMP9 signaling following mast cell

recruitment (76). The CCL2/CCR2

pathway induces the invasion and EMT of HCC in vitro by

activating the Hedgehog pathway (Fig.

2) (77).

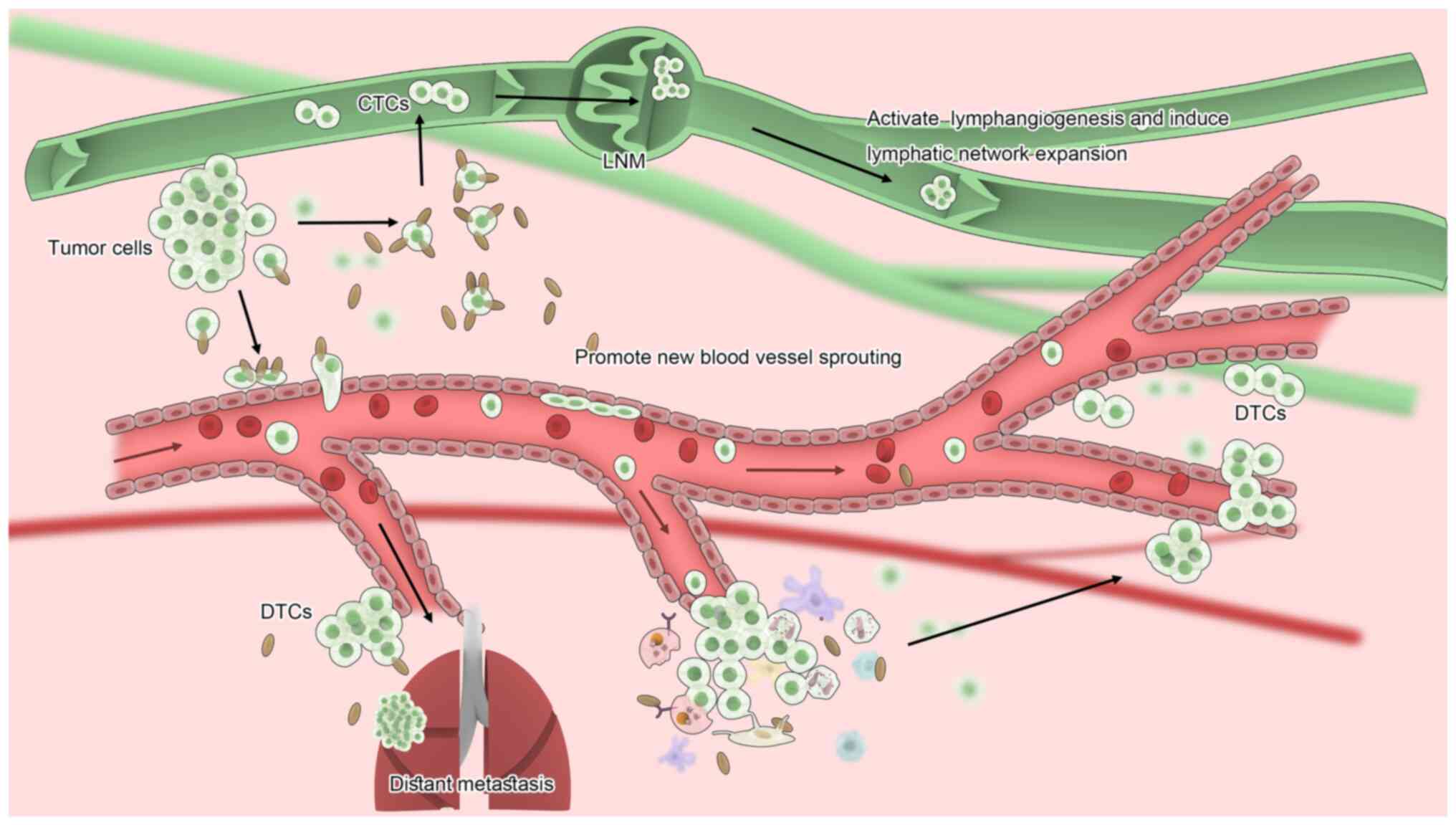

Tumor angiogenesis requires the production of

angiogenic factors by tumor cells and stromal components. CCL2

directly promotes angiogenesis via the activation of

CCR2-expressing vascular endothelial cells (78–80).

Concurrently, the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis enhances vascular

permeability, facilitating efficient extravasation of tumor cells

and metastatic niche formation (81). Human endothelial cells express CCR2,

which promotes tumor angiogenesis and progression after binding to

CCL2. Several clinical studies have shown that CCL2 may be a

biomarker of tumor angiogenesis (82–84).

The activation of the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis in the TME promotes

tumor angiogenesis (83). CCL2

directly interacts with CCR2 on the surface of endothelial cells,

resulting in increased vessel sprouting and angiogenesis (84). As a chemokine produced in abundance

by certain types of tumor, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

glioblastoma, and Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) (85), it can also directly promote tumor

progression. Therefore, therapy using MCP-1 antagonists in

combination with other angiogenesis inhibitors may suppress tumor

growth (86).

In contrast to earlier assumptions, emerging

evidence has indicated that tumor vascular endothelial cells lack

CCR2 expression (87,88). Instead, CCL2 drives angiogenesis

indirectly by recruiting TAMs and increasing VEGF-A production in

these cells (89–92). In addition, CCL2 enhances cancer

cell autonomous VEGF secretion, further contributing to

neovascularization. In melanoma, this axis is amplified by

autocrine/paracrine loops, wherein CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 are

co-expressed (93,94). AM-derived TNFα and IL-1α synergize

with VEGF to promote endothelial cell activation, thereby

accelerating early-stage tumor angiogenesis and growth (9).

The TME is a dynamically complex ecosystem, where

inflammatory networks composed of immune cells and their secretory

products influence cancer biology and progression (95). Chemokine-chemokine receptor

interactions are key to recruiting inflammatory cells into the TME,

with CCL2 serving as a key driver of inflammatory monocyte

accumulation (96). Inflammatory

monocytes exhibit high expression of CCR2 (26), while other CCR2-expressing

leukocytes, including CD8+ effector T cells and

CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) (19,97)

and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (98), are enriched in inflamed tumor

tissues. The CCL2/CCR2 pathway orchestrates metastatic

microenvironment formation, exerting pro-tumorigenic and

pro-metastatic functions in numerous types of cancer (99,100).

In sarcoma and breast cancer, the CCL2/CCR2 axis

mediates the recruitment of TAMs and MDSCs to the TME (89). T cells infiltrate tumors in an

antigen-specific manner, with IFN-γ secreted by early-invading T

cells inducing tissue macrophages to increase CCL2 expression

(101,102). This creates a positive feedback

loop wherein CCL2 recruits additional T cells and macrophages via

CCR2 signaling, enhancing immune cell infiltration. CCR2 expression

is detectable in tumor-infiltrating immune cells, supporting the

role of active chemotactic recruitment (101,102). In NPC, this mechanism is

exemplified by T cell-derived IFN-γ activating macrophages to

secrete CCL2, thereby amplifying T-cell and macrophage accumulation

via the CCL2/CCR2 pathway (103).

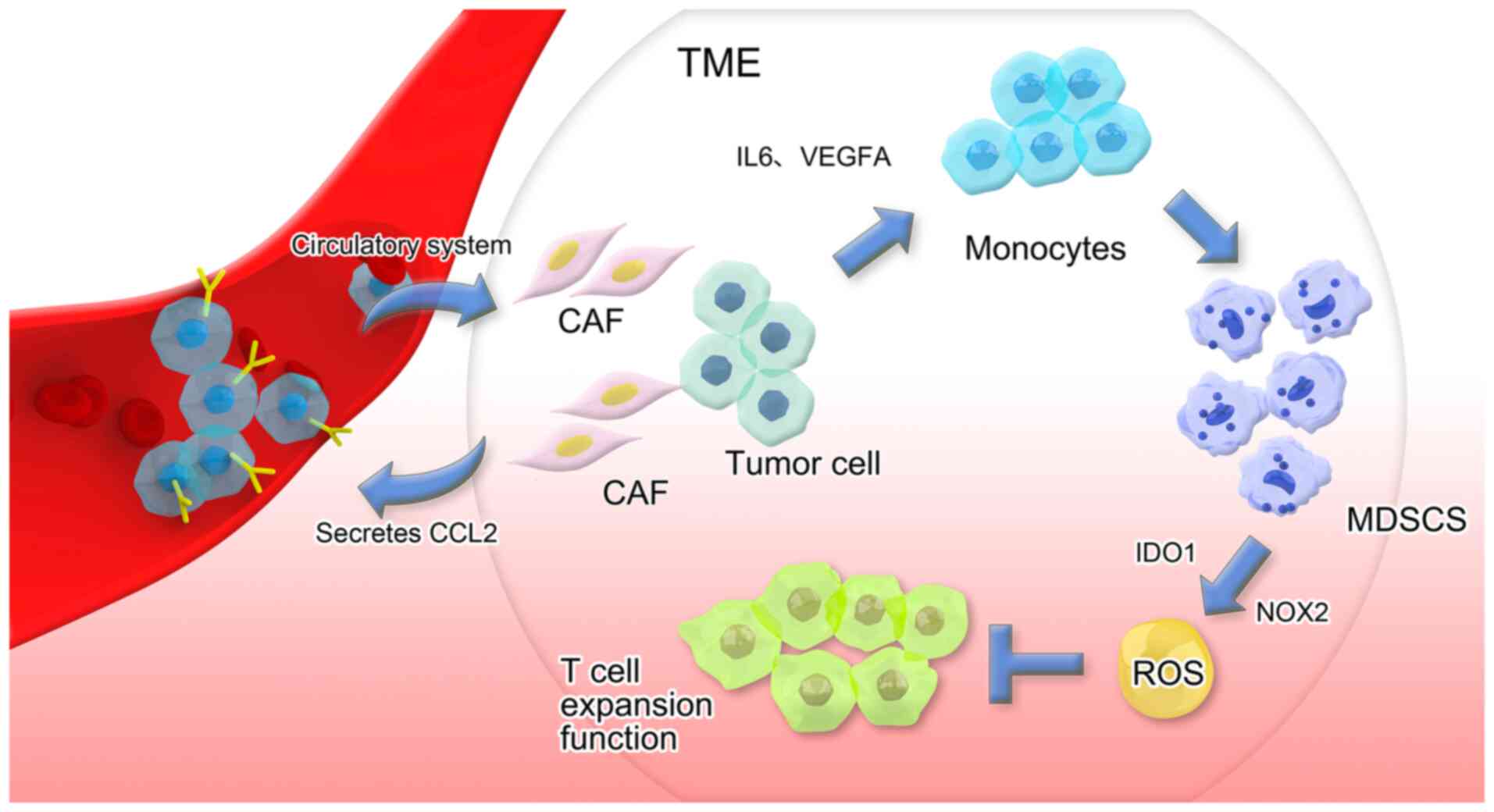

CAFs, as a key component of the TME, represent

activated fibroblast populations that impact stromal compartment

remodeling within the TME via collagen deposition and MMP secretion

(104). CAFs constitute one of the

most prevalent cell types in the tumor stroma (105), and evidence has highlighted their

tumor-promoting functions, including accelerating tumor

proliferation, facilitating metastatic progression and shielding

tumors from therapeutic agent penetration (106–108).

Accumulating evidence has highlighted the crosstalk

between CAFs and immunosuppressive cell lineages, which is

primarily due to the immune-modulatory functions of CAFs (109–111). CAFs secreting CCL2 facilitate the

recruitment of CCR2+ monocytes from the bloodstream into

the TME, where direct cell-cell interactions drive monocyte

differentiation into MDSCs. CAF-educated MDSCs suppress T-cell

proliferation via upregulation of NADPH oxidase 2 and indoleamine

2,3-dioxygenase 1, leading to excessive reactive oxygen species

production that inhibits immune effector function (Fig. 3) (112).

Crosstalk with cancer cells drives CCL2 upregulation

in CAFs, which contributes to metastatic niche establishment during

early tumor progression and modulates broader tumor functionality

(113–118). In a murine liver tumor model,

fibroblast STAT3/CCL2 signaling has been shown to enhance MDSC

recruitment, thereby promoting tumor growth (119). In addition, the CCL2/CCR2

signaling pathway facilitates early breast cancer survival and

invasion via a fibroblast-mediated mechanism (120).

A previous study demonstrated that discoidin domain

receptor 1 (DDR1) orchestrates an immunosuppressive TME by

activating CAFs to secrete CCL2 and IL-6. This signaling axis

exhibits dual regulatory effects by recruiting immunosuppressive

cells, including MDSCs and TAMs, and facilitating extracellular

matrix remodeling through enhanced collagen deposition and MMP9

activation. These findings demonstrate the key role of the

DDR1/CCL2/IL-6 pathway in CAF-mediated immunosuppression, providing

a potential therapeutic strategy to target tumor fibrosis and

immune evasion (121,122).

CCL2 primarily regulates the directional migration

and invasive infiltration of reticuloendothelial system cells, with

a focus on monocyte/macrophage phenotypes (123). CCL2 induces monocytes to exit the

bloodstream and extravasate into peripheral tissue (71), where they differentiate into

tissue-resident macrophages. The CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway has

been implicated in recruiting macrophages in various types of human

cancer, including those originating in the bladder, cervix, ovary,

lung and breast (124–127). TAMs, a major component of

infiltrating inflammatory cells, are regulated by the CCL2/CCR2

pathway through a macrophage-dependent mechanism sustained by

positive feedback loops (61,128).

As a key chemokine system mediating blood cell recruitment,

particularly macrophages, into tissues (11,128–130), CCL2/CCR2 signaling drives tumor

progression. M2-polarized TAMs influence tumor progression and

metastasis (131), and CCL2

secretion recruits TAMs that mediate metastatic phenotypes in

ER-negative breast cancer (64).

TAMs drive prostate cancer metastasis via activation

of the CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway (132). Phenotypically, tumor-infiltrating

macrophages can be tumor-supportive (M2) or function in tumor

immune surveillance (M1). TAMs of the M1 type lead to a better

prognosis, whereas TAMs of the M2 type lead to a poorer prognosis.

Tumors associated with M2-type TAMs include breast, ovarian and

prostate cancer (133–135). TAM recruitment is dependent on the

CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis and the formation of a tumor-supportive

microenvironment depends on altered cellular dynamics following the

interaction of CCL2, T cells and monocytes (136).

TAMs serve a pivotal role in driving hormone

resistance in prostate cancer cells (137). Within the prostate TME,

M2-polarized TAMs exert pro-tumorigenic effects. Previous studies

(78,138) employed a PC3 cell xenograft model

to show that CCL2 increases in vivo prostate tumor growth

and metastasis by enhancing TAM recruitment and angiogenesis.

Investigations (139,140) have also revealed that M2-phenotype

TAMs influence cancer progression and metastasis; in human lung

cancer, CCL2/CCR2 signaling promotes tumor cell proliferation,

migration and M2 polarization of TAMs (131). In pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, the CCL2/CCR2 axis recruits TAMs to establish an

immunosuppressive TME (141).

Conversely, anti-CCL2 antibody treatment in breast cancer xenograft

models has been shown to diminish macrophage infiltration and tumor

growth (142,143).

The CCL2/CCR2 pathway is indispensable for

monocyte/macrophage recruitment. The therapeutic interruption of

this pathway suppresses inflammatory monocyte recruitment, TAM

infiltration and M2 polarization, thereby reversing the

immunosuppressive state of the TME and activating antitumor

CD8+ T-cell responses (39). Platelet-derived growth

factor-BB-mediated autocrine signaling drives CCL2 secretion, which

recruits macrophages via the CCL2/CCR2 axis to facilitate lung

cancer cell invasion (144).

Targeting CCL2/CCR2 signaling in tumor-infiltrating macrophages has

emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for HCC (145). Preclinical studies (26,93,146,147) have also shown that genetic

knockout of CCR2 or pharmacological blockade with CCR2 antagonists

inhibits malignant growth and metastasis, decreases postoperative

recurrence and improves survival rates. In pancreatic

adenocarcinoma, cancer cells exploit chemokine pathways,

particularly CCL2/CCR2, to establish an immunosuppressive niche

(146). Blocking TAM recruitment

inhibits murine breast cancer growth (148). In addition, the JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway promotes M2-like macrophage polarization, which

drives gastric cancer metastasis via EMT (149).

Tregs, a specialized subset of T cells, are key for

maintaining peripheral self-tolerance and preventing

immunopathological responses (150). Tumors exploit immune evasion

mechanisms to sustain uncontrolled growth, with high intratumoral

Treg abundance contributing to the establishment of

immunosuppressive microenvironments. Tregs exert suppressive

effects on T-cell proliferation and cytotoxic function (151,152). The infiltration of Tregs in tumors

is influenced by both in situ generation (mediated by

cytokine secretion) and peripheral recruitment (driven by chemokine

signaling) (153). Tumor-derived

CCL2 has been implicated in inducing Treg migration into the TME.

For example, in glioma local immunosuppression is enhanced by

selectively recruiting CCL2/CCR2-dependent Tregs (129), while colorectal cancer cells

secrete CCL2 that binds to CCR2 on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs),

paradoxically promoting CTL migration to tumors (44).

Tumors employ diverse evasion strategies to

circumvent immune recognition and elimination. Intratumoral

immunosuppressive MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of

immature myeloid cells originating from bone marrow progenitors

(154–156). MDSCs exert multifaceted

tumor-promoting activities (157).

The CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway governs the recruitment of

myelosuppressive cells to tumor sites. Studies have demonstrated

that CCR2 is universally expressed on MDSCs, the primary drivers of

tumor immune evasion, and blocking CCL2/CCR2 signaling inhibits

MDSC migration and tumor growth facilitated by these cells

(31,112,158–160). Collectively, these data

demonstrate a key role for the CCL2/CCR2 pathway in regulating MDSC

trafficking. CCL2/CCR2 interactions also recruit other

immunosuppressive cells, including monocytes, to form a

pro-metastatic microenvironment (26,98).

The immunosuppressive Treg-MDSC network drives

immune exclusion and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) resistance.

In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, semaphorin (SEMA)4D

blockade using pepinemab disrupts MDSC recruitment while enhancing

T-cell infiltration (KEYNOTE-B84 trial) (161). In bladder cancer, gemcitabine/BCG

decreases IL-6-mediated MDSC suppression. Prostate cancer subtyping

has revealed TGF-β-enriched, immune-excluded tumors (stage I) with

a poor ICI response vs. inflamed subtypes (S-IV). Targeting this

axis (via SEMA4D inhibition or myeloid modulation) represents a

promising therapeutic strategy (162).

The CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway serves a central

role in shaping the TME by regulating both tumor progression and

antitumor immunity (2). Through the

activation of the PI3K/AKT, MAPK and EMT pathways (Fig. 2), the CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway

promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis.

Paradoxically, it also mediates antitumor effects by recruiting

immune cells and activating immunosurveillance mechanisms (143). This dual functionality stems from

its ability to recruit diverse immune populations. While MDSCs,

TAMs and Tregs establish an immunosuppressive TME that facilitates

metastasis, the CCL2/CCR2 pathway simultaneously promotes TIL

infiltration and enhances antitumor lymphocyte function (Fig. 4) (163). In melanoma, CCL2/CCR2 signaling

drives resistance to BRAF/MEK inhibitors by expanding MDSCs and

suppressing CD8+ T cells (164–168). The TNF-related apoptosis-inducing

ligand-CCL2 axis further reinforces this resistance by polarizing

monocytes toward MDSCs and M2-like macrophages, facilitating tumor

progression (169,170).

The therapeutic targeting of the CCL2/CCR2 axis

involves multiple strategies with distinct mechanisms and clinical

implications. Small-molecule CCR2 antagonists (such as PF-04136309

and BMS-813160) block immunosuppressive MDSC/TAM recruitment and

restore antitumor immunity in preclinical models (164,165,169,176), with ongoing clinical trials

(177,178) evaluating their efficacy in

combination with chemotherapy or immunotherapy (trial no.

NCT03184870). While anti-CCL2 antibodies (carlumab/CNTO-888) have

demonstrated partial responses in early trials, compensatory CCL2

upregulation limits their efficacy, prompting the exploration of

combination strategies with programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/CTLA-4

inhibitors to overcome resistance (172). Dual targeting approaches

simultaneously inhibiting CCL2 and CCR2 (CCL2-trapping agents and

CCR2 antagonists) may prevent microenvironmental bypass mechanisms,

particularly in BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma (166–168). Furthermore, elevated CCL2/MDSC

signatures could serve as predictive biomarkers for patient

selection, with studies (179–181) investigating liquid biopsy-based

monitoring (CCR2+ exosomes) (170).

The net biological effect of the CCL2/CCR2 axis is

fundamentally context-dependent, governed by four intersecting

factors: i) Temporal dynamics, where early-phase immune

surveillance progressively shifts to late-stage TME remodeling; ii)

spatial heterogeneity across distinct tumor niches; iii) immune

cell composition ratios, particularly the M1/M2 macrophage

equilibrium; and iv) host genetic background, including CCR2

isoform expression patterns. This necessitates identification of

the biological threshold where pro-tumor effects supersede

antitumor mechanisms. This may be regulated by three factors: i)

CCL2 concentration thresholds, ii) specific immune cell

infiltration ratio and iii) hypoxia-induced pathway activation

states. These mechanistic insight may inform clinical strategies,

as evidenced by Phase II trial (182) (trial no. NCT03184870) combining

anti-CCL2 agents with PD-1 inhibitors in non-small cell lung

cancer, which aim to therapeutically manipulate this balance.

While preclinical findings have provided

mechanistic insights into the CCL2/CCR2 pathway in cancer

progression, direct clinical validation in human malignancies

remains limited. Although studies (183,184) have investigated CCR2 antagonists

(PF-04136309) or CCL2 inhibitors (CNTO-888), most therapeutic

strategies have focused on an individual target blockade rather

than coordinated modulation of the CCL2/CCR2 interaction. Future

studies should prioritize the following: i) Comprehensive CCL2/CCR2

co-expression profiling in patient-derived samples, ii)

longitudinal assessment of axis activation during CCR2-targeted

therapy and iii) development of novel dual-targeting approaches to

elucidate the clinical relevance of this chemokine axis in human

cancer.

The present study provides a rationale for the

clinical evaluation of CCL2/CCR2 axis inhibitors in combination

with existing immunotherapies, offering potential for

treatment-resistant malignancies, including melanoma. Future

studies should focus on optimizing combination strategies and

identifying predictive biomarkers for patient stratification.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research Fund

project of Education Department of Yunnan Province (grant no.

2025J0181).

Not applicable.

YZ, BF, HY and ZY conceived and designed the study.

YZ wrote the manuscript. HY constructed figures. GC and ZH designed

and implemented the comprehensive literature search strategy,

established rigorous eligibility criteria for study inclusion,

synthesized key findings to construct the theoretical framework,

made substantial contributions to both the Introduction and

Discussion sections and actively participated in critical revision

of the manuscript with particular focus on ensuring the accuracy

and optimal presentation of figures. Specifically, GC conceived the

core visual framework for all figures, which was instrumental in

interpreting the study's conceptual approach and ZH established the

comparative logic and data hierarchy in figures, ensuring perfect

alignment with the manuscript's analytical narrative. YiL and XM

acquired full-text articles and independently screened literature

(resolving discrepancies through consensus), organized references

(using EndNote), revised the Discussion section for clarity and

clinical relevance, and oordinated revision feedback among all

co-authors to ensure consistency. TW conducted supplementary

literature searches to validate results, provided visualization

support (including figure and table design), revised the Discussion

section with critical intellectual input and helped coordinate

final revisions. WW, LC, LH, YaL, DL, XC and YY reviewed the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S,

Appella E, Kuratsu J and Leonard EJ: Purification and amino acid

analysis of two human glioma-derived monocyte chemoattractants. J

Exp Med. 169:1449–1459. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yoshimura T: The production of monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCL2 in tumor microenvironments.

Cytokine. 98:71–78. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kurihara T, Warr G, Loy J and Bravo R:

Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking

the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med. 186:1757–1762. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mackay CR: Chemokines: Immunology's high

impact factors. Nat Immunol. 2:95–101. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Strieter RM: Chemokines: Not just

leukocyte chemoattractants in the promotion of cancer. Nat Immunol.

2:285–286. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lim SY, Yuzhalin AE, Gordon-Weeks AN and

Muschel RJ: Targeting the CCL2-CCR2 signaling axis in cancer

metastasis. Oncotarget. 7:28697–28710. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Loberg RD, Day LL, Harwood J, Ying C, St

John LN, Giles R, Neeley CK and Pienta KJ: CCL2 is a potent

regulator of prostate cancer cell migration and proliferation.

Neoplasia. 8:578–586. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Craig MJ and Loberg RD: CCL2 (Monocyte

Chemoattractant Protein-1) in cancer bone metastases. Cancer

Metastasis Rev. 25:611–619. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Koga M, Kai H, Egami K, Murohara T, Ikeda

A, Yasuoka S, Egashira K, Matsuishi T, Kai M, Kataoka Y, et al:

Mutant MCP-1 therapy inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth of

malignant melanoma in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

365:279–284. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu Q, Zhang H, Jiang X, Qian C, Liu Z and

Luo D: Factors involved in cancer metastasis: A better

understanding to ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis. Mol Cancer.

16:1762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S and Sawaya

BE: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): An overview. J

Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:313–326. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Charo IF and Ransohoff RM: The many roles

of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J

Med. 354:610–621. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Raman D, Baugher PJ, Thu YM and Richmond

A: Role of chemokines in tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 256:137–165.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Balkwill FR: The chemokine system and

cancer. J Pathol. 226:148–157. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Frederick MJ and Clayman GL: Chemokines in

cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 3:1–18. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Paget S: The distribution of secondary

growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

8:98–101. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: The hallmarks

of cancer. Cell. 100:57–70. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Brown CE, Vishwanath RP, Aguilar B, Starr

R, Najbauer J, Aboody KS and Jensen MC: Tumor-derived chemokine

MCP-1/CCL2 is sufficient for mediating tumor tropism of adoptively

transferred T cells. J Immunol. 179:3332–3341. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rollins BJ and Sunday ME: Suppression of

tumor formation in vivo by expression of the JE gene in malignant

cells. Mol Cell Biol. 11:3125–3131. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Monti P, Leone BE, Marchesi F, Balzano G,

Zerbi A, Scaltrini F, Pasquali C, Calori G, Pessi F, Sperti C, et

al: The CC chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 in pancreatic cancer progression:

regulation of expression and potential mechanisms of antimalignant

activity. Cancer Res. 63:7451–7461. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gunderson AJ, Yamazaki T, McCarty K, Fox

N, Phillips M, Alice A, Blair T, Whiteford M, O'Brien D, Ahmad R,

et al: TGFβ suppresses CD8(+) T cell expression of CXCR3 and tumor

trafficking. Nat Commun. 11:17492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Qin J, Gong Q, Zhou C, Xu J, Cheng Y, Xu

W, Zhu D, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al: Differential expression

pattern of CC chemokine receptor 7 guides precision treatment of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:2292025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wei XL, Zhang Y, Zhao HY, Fang WF, Luo HY,

Qiu MZ, He MM, Zou BY, Xie J, Jin CL, et al: Safety and clinical

activity of SHR7390 monotherapy or combined with camrelizumab for

advanced solid tumor: Results from two phase I trials. Oncologist.

28:e36–e44. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mestdagt M, Polette M, Buttice G, Noël A,

Ueda A, Foidart JM and Gilles C: Transactivation of MCP-1/CCL2 by

beta-catenin/TCF-4 in human breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer.

118:35–42. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang

J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA and Pollard JW: CCL2 recruits

inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis.

Nature. 475:222–225. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kitamura T, Qian BZ, Soong D, Cassetta L,

Noy R, Sugano G, Kato Y, Li J and Pollard JW: CCL2-induced

chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing

retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med.

212:1043–1059. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Granot Z, Henke E, Comen EA, King TA,

Norton L and Benezra R: Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding

in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell. 20:300–314. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Pekarek LA, Starr BA, Toledano AY and

Schreiber H: Inhibition of tumor growth by elimination of

granulocytes. J Exp Med. 181:435–440. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Shojaei F, Singh M, Thompson JD and

Ferrara N: Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a

transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

105:2640–2645. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M and

Gabrilovich DI: Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in

tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 181:5791–5802. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Nozawa H, Chiu C and Hanahan D:

Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a

mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:12493–12498. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

De Larco JE, Wuertz BR and Furcht LT: The

potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype

of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 10:4895–4900.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cheng Y, Mo F, Li Q, Han X, Shi H, Chen S,

Wei Y and Wei X: Targeting CXCR2 inhibits the progression of lung

cancer and promotes therapeutic effect of cisplatin. Mol Cancer.

20:622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Song M, He J, Pan QZ, Yang J, Zhao J,

Zhang YJ, Huang Y, Tang Y, Wang Q, He J, et al: Cancer-associated

fibroblast-mediated cellular crosstalk supports hepatocellular

carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 73:1717–1735. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dutta P, Sarkissyan M, Paico K, Wu Y and

Vadgama JV: MCP-1 is overexpressed in triple-negative breast

cancers and drives cancer invasiveness and metastasis. Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 170:477–486. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Parween F, Singh SP, Kathuria N, Zhang HH,

Ashida S, Otaizo-Carrasquero FA, Shamsaddini A, Gardina PJ, Ganesan

S, Kabat J, et al: Migration arrest and transendothelial

trafficking of human pathogenic-like Th17 cells are mediated by

differentially positioned chemokines. Nat Commun. 16:19782025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dey D, Pal S, Chakraborty BC, Baidya A,

Bhadra S, Ghosh R, Banerjee S, Ahammed SKM, Chowdhury A and Datta

S: Multifaceted defects in monocytes in different phases of chronic

hepatitis B virus infection: Lack of restoration after antiviral

therapy. Microbiol Spectr. 10:e01939222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li X, Yao W, Yuan Y, Chen P, Li B, Li J,

Chu R, Song H, Xie D, Jiang X and Wang H: Targeting of

tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a

therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut.

66:157–167. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, Choy A,

Gallardo F, Xiong N, Knoblaugh S, Cado D, Greenberg NM and Raulet

DH: NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in

models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity. 28:571–580. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lujambio A, Akkari L, Simon J, Grace D,

Tschaharganeh DF, Bolden JE, Zhao Z, Thapar V, Joyce JA,

Krizhanovsky V and Lowe SW: Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression

by p53. Cell. 153:449–460. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Iannello A, Thompson TW, Ardolino M, Lowe

SW and Raulet DH: p53-dependent chemokine production by senescent

tumor cells supports NKG2D-dependent tumor elimination by natural

killer cells. J Exp Med. 210:2057–2069. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nagai M and Masuzawa T: Vaccination with

MCP-1 cDNA transfectant on human malignant glioma in nude mice

induces migration of monocytes and NK cells to the tumor. Int

Immunopharmacol. 1:657–664. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Berencsi K, Rani P, Zhang T, Gross L,

Mastrangelo M, Meropol NJ, Herlyn D and Somasundaram R: In vitro

migration of cytotoxic T lymphocyte derived from a colon carcinoma

patient is dependent on CCL2 and CCR2. J Transl Med. 9:332011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Nakasone Y, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T,

Hamaguchi Y, Huu DL, Yanaba M, Sato S, Takehara K and Hasegawa M:

Host-derived MCP-1 and MIP-1α regulate protective anti-tumor

immunity to localized and metastatic B16 melanoma. Am J Pathol.

180:365–374. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Joyce JA and Pollard JW:

Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:239–252. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang J, Sarkar S, Cua R, Zhou Y, Hader W

and Yong VW: A dialog between glioma and microglia that promotes

tumor invasiveness through the CCL2/CCR2/interleukin-6 axis.

Carcinogenesis. 33:312–319. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bogenrieder T and Herlyn M: Axis of evil:

molecular mechanisms of cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 22:6524–6536.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Rafei M, Deng J, Boivin MN, Williams P,

Matulis SM, Yuan S, Birman E, Forner K, Yuan L, Castellino C, et

al: A MCP1 fusokine with CCR2-specific tumoricidal activity. Mol

Cancer. 10:1212011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Johnson Z, Power CA, Weiss C, Rintelen F,

Ji H, Ruckle T, Camps M, Wells TN, Schwarz MK, Proudfoot AE and

Rommel C: Chemokine inhibition-why, when, where, which and how?

Biochem Soc Trans. 32:366–377. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mellado M, Rodríguez-Frade JM, Aragay A,

del Real G, Martín AM, Vila-Coro AJ, Serrano A, Mayor F Jr and

Martínez-A C: The chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein 1 triggers

Janus kinase 2 activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of the CCR2B

receptor. J Immunol. 161:805–813. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Jiménez-Sainz MC, Fast B, Mayor F Jr and

Aragay AM: Signaling pathways for monocyte chemoattractant protein

1-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Mol

Pharmacol. 64:773–782. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Tang CH and Tsai CC: CCL2 increases MMP-9

expression and cell motility in human chondrosarcoma cells via the

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol.

83:335–344. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Dagouassat M, Suffee N, Hlawaty H, Haddad

O, Charni F, Laguillier C, Vassy R, Martin L, Schischmanoff PO,

Gattegno L, et al: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCL2

secreted by hepatic myofibroblasts promotes migration and invasion

of human hepatoma cells. Int J Cancer. 126:1095–1108. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Schröer N, Pahne J, Walch B, Wickenhauser

C and Smola S: Molecular pathobiology of human cervical high-grade

lesions: Paracrine STAT3 activation in tumor-instructed myeloid

cells drives local MMP-9 expression. Cancer Res. 71:87–97. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Balkwill F and Mantovani A: Inflammation

and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet. 357:539–545. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Pollard JW: Tumour-educated macrophages

promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:71–78.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

van Kempen LC, de Visser KE and Coussens

LM: Inflammation, proteases and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 42:728–734.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yumimoto K, Sugiyama S, Mimori K and

Nakayama KI: Potentials of C-C motif chemokine 2-C-C chemokine

receptor type 2 blockers including propagermanium as anticancer

agents. Cancer Sci. 110:2090–2099. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Fang WB, Jokar I, Zou A, Lambert D,

Dendukuri P and Cheng N: CCL2/CCR2 chemokine signaling coordinates

survival and motility of breast cancer cells through Smad3 protein-

and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent

mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 287:36593–36608. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yao M, Fang W, Smart C, Hu Q, Huang S,

Alvarez N, Fields P and Cheng N: CCR2 chemokine receptors enhance

growth and cell-cycle progression of breast cancer cells through

SRC and PKC Activation. Mol Cancer Res. 17:604–617. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Gao J, Wang A, Zhang M, Li H, Wang K, Han

Y, Wang Z, Shi C and Wang W: RNAi targeting of CCR2 gene expression

induces apoptosis and inhibits the proliferation, migration, and

invasion of PC-3M cells. Oncol Res. 21:73–82. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chiu HY, Sun KH, Chen SY, Wang HH, Lee MY,

Tsou YC, Jwo SC, Sun GH and Tang SJ: Autocrine CCL2 promotes cell

migration and invasion via PKC activation and tyrosine

phosphorylation of paxillin in bladder cancer cells. Cytokine.

59:423–432. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Vande Broek I, Asosingh K, Vanderkerken K,

Straetmans N, Van Camp B and Van Riet I: Chemokine receptor CCR2 is

expressed by human multiple myeloma cells and mediates migration to

bone marrow stromal cell-produced monocyte chemotactic proteins

MCP-1, −2 and −3. Br J Cancer. 88:855–862. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yang J, Lv X, Chen J, Xie C, Xia W, Jiang

C, Zeng T, Ye Y, Ke L, Yu Y, et al: CCL2-CCR2 axis promotes

metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by activating ERK1/2-MMP2/9

pathway. Oncotarget. 7:15632–15647. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Xu M, Wang S, Qi Y, Chen L, Frank JA, Yang

XH, Zhang Z, Shi X and Luo J: Role of MCP-1 in alcohol-induced

aggressiveness of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog.

55:1002–1011. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Yasui H, Kajiyama H, Tamauchi S, Suzuki S,

Peng Y, Yoshikawa N, Sugiyama M, Nakamura K and Kikkawa F: CCL2

secreted from cancer-associated mesothelial cells promotes

peritoneal metastasis of ovarian cancer cells through the P38-MAPK

pathway. Clin Exp Metastasis. 37:145–158. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Furukawa S, Soeda S, Kiko Y, Suzuki O,

Hashimoto Y, Watanabe T, Nishiyama H, Tasaki K, Hojo H, Abe M and

Fujimori K: MCP-1 promotes invasion and adhesion of human ovarian

cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 33:4785–4790. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Macanas-Pirard P, Quezada T, Navarrete L,

Broekhuizen R, Leisewitz A, Nervi B and Ramírez PA: The CCL2/CCR2

axis affects transmigration and proliferation but not resistance to

chemotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia cells. PLoS One.

12:e01688882017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Salacz ME, Kast RE, Saki N, Brüning A,

Karpel-Massler G and Halatsch ME: Toward a noncytotoxic

glioblastoma therapy: Blocking MCP-1 with the MTZ Regimen. Onco

Targets Ther. 9:2535–2545. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

An J, Xue Y, Long M, Zhang G, Zhang J and

Su H: Targeting CCR2 with its antagonist suppresses viability,

motility and invasion by downregulating MMP-9 expression in

non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 8:39230–39240. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Giannelli G, Koudelkova P, Dituri F and

Mikulits W: Role of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 65:798–808. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

van Zijl F, Zulehner G, Petz M, Schneller

D, Kornauth C, Hau M, Machat G, Grubinger M, Huber H and Mikulits

W: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Future Oncol. 5:1169–1179. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Li H, Li H, Li XP, Zou H, Liu L, Liu W and

Duan T: C-C chemokine receptor type 2 promotes

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by upregulating matrix

metalloproteinase-2 in human liver cancer. Oncol Rep. 40:2734–2741.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Izumi K, Fang LY, Mizokami A, Namiki M, Li

L, Lin WJ and Chang C: Targeting the androgen receptor with siRNA

promotes prostate cancer metastasis through enhanced macrophage

recruitment via CCL2/CCR2-induced STAT3 activation. EMBO Mol Med.

5:1383–1401. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Rao Q, Chen Y, Yeh CR, Ding J, Li L, Chang

C and Yeh S: Recruited mast cells in the tumor microenvironment

enhance bladder cancer metastasis via modulation of ERβ/CCL2/CCR2

EMT/MMP9 signals. Oncotarget. 7:7842–7855. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Zhuang H, Cao G, Kou C and Liu T:

CCL2/CCR2 axis induces hepatocellular carcinoma invasion and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro through activation of

the Hedgehog pathway. Oncol Rep. 39:21–30. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Koide N, Nishio A, Sato T, Sugiyama A and

Miyagawa S: Significance of macrophage chemoattractant protein-1

expression and macrophage infiltration in squamous cell carcinoma

of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 99:1667–1674. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA, Wasserman

K, Ward JM, Kleinman HK, Oppenheim JJ and Murphy WJ: Human

endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: direct role of

MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood. 96:34–40. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Hong KH, Ryu J and Han KH: Monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1-induced angiogenesis is mediated by

vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Blood. 105:1405–1407. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Wyler L, Napoli CU, Ingold B, Sulser T,

Heikenwälder M, Schraml P and Moch H: Brain metastasis in renal

cancer patients: Metastatic pattern, tumour-associated macrophages

and chemokine/chemoreceptor expression. Br J Cancer. 110:686–694.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Valković T, Babarović E, Lučin K, Štifter

S, Aralica M, Seili-Bekafigo I, Duletić-Načinović A and Jonjić N:

Plasma levels of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 are associated with

clinical features and angiogenesis in patients with multiple

myeloma. Biomed Res Int. 2016:78705902016.

|

|

83

|

Li F, Kitajima S, Kohno S, Yoshida A,

Tange S, Sasaki S, Okada N, Nishimoto Y, Muranaka H, Nagatani N, et

al: Retinoblastoma inactivation induces a protumoral

microenvironment via enhanced CCL2 secretion. Cancer Res.

79:3903–3915. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Li X, Loberg R, Liao J, Ying C, Snyder LA,

Pienta KJ and McCauley LK: A destructive cascade mediated by CCL2

facilitates prostate cancer growth in bone. Cancer Res.

69:1685–1692. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Balkwill F: Cancer and the chemokine

network. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:540–550. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Niu J, Azfer A, Zhelyabovska O, Fatma S

and Kolattukudy PE: Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 promotes

angiogenesis via a novel transcription factor, MCP-1-induced

protein (MCPIP). J Biol Chem. 283:14542–14551. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M,

Yasui W, Mukaida N, Haruma K and Chayama K: Monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage

infiltration and tumor vascularity in human esophageal squamous

cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 102:220–224. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Kuroda T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Yang X,

Mukaida N, Yoshihara M and Chayama K: Monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 transfection induces angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of

gastric carcinoma in nude mice via macrophage recruitment. Clin

Cancer Res. 11:7629–7636. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Goede V, Brogelli L, Ziche M and Augustin

HG: Induction of inflammatory angiogenesis by monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1. Int J Cancer. 82:765–770. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Low-Marchelli JM, Ardi VC, Vizcarra EA,

van Rooijen N, Quigley JP and Yang J: Twist1 induces CCL2 and

recruits macrophages to promote angiogenesis. Cancer Res.

73:662–671. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Varney ML, Olsen KJ, Mosley RL and Singh

RK: Paracrine regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-a

expression during macrophage-melanoma cell interaction: Role of

monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and macrophage colony-stimulating

factor. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:674–683. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Jetten N, Verbruggen S, Gijbels MJ, Post

MJ, De Winther MP and Donners MM: Anti-inflammatory M2, but not

pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo.

Angiogenesis. 17:109–118. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Bonapace L, Coissieux MM, Wyckoff J, Mertz

KD, Varga Z, Junt T and Bentires-Alj M: Cessation of CCL2

inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting

angiogenesis. Nature. 515:130–133. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Liu L, Li Y and Li B: Interactions between

cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages in tumor

microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1880:1893442025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Biswas SK and Mantovani A: Macrophage

plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: Cancer as a

paradigm. Nat Immunol. 11:889–896. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Allavena P, Germano G, Marchesi F and

Mantovani A: Chemokines in cancer related inflammation. Exp Cell

Res. 317:664–673. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Fridlender ZG, Buchlis G, Kapoor V, Cheng

G, Sun J, Singhal S, Crisanti MC, Wang LC, Heitjan D, Snyder LA and

Albelda SM: CCL2 blockade augments cancer immunotherapy. Cancer

Res. 70:109–118. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Huang B, Lei Z, Zhao J, Gong W, Liu J,

Chen Z, Liu Y, Li D, Yuan Y, Zhang GM and Feng ZH: CCL2/CCR2

pathway mediates recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells to

cancers. Cancer Lett. 252:86–92. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Samaniego R, Estecha A, Relloso M, Longo

N, Escat JL, Longo-Imedio I, Avilés JA, del Pozo MA, Puig-Kröger A

and Sánchez-Mateos P: Mesenchymal contribution to recruitment,

infiltration, and positioning of leukocytes in human melanoma

tissues. J Invest Dermatol. 133:2255–2264. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Roblek M, Strutzmann E, Zankl C, Adage T,

Heikenwalder M, Atlic A, Weis R, Kungl A and Borsig L: Targeting of

CCL2-CCR2-glycosaminoglycan axis using a CCL2 decoy protein

attenuates metastasis through inhibition of tumor cell seeding.

Neoplasia. 18:49–59. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Zhu Y, Yan P, Wang R, Lai J, Tang H, Xiao

X, Yu R, Bao X, Zhu F, Wang K, et al: Opioid-induced fragile-like

regulatory T cells contribute to withdrawal. Cell. 186:591–606.e23.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Kong X, Wu S, Dai X, Yu W, Wang J, Sun Y,

Ji Z, Ma L, Dai X, Chen H, et al: A comprehensive profile of

chemokines in the peripheral blood and vascular tissue of patients

with Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 24:492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Tang KF, Tan SY, Chan SH, Chong SM, Loh

KS, Tan LK and Hu H: A distinct expression of CC chemokines by

macrophages in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: implication for the

intense tumor infiltration by T lymphocytes and macrophages. Hum

Pathol. 32:42–49. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Kalluri R: The biology and function of

fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 16:582–598. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Gok Yavuz B, Gunaydin G, Gedik ME,

Kosemehmetoglu K, Karakoc D, Ozgur F and Guc D: Cancer associated

fibroblasts sculpt tumour microenvironment by recruiting monocytes

and inducing immunosuppressive PD-1(+) TAMs. Sci Rep. 9:31722019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

LeBleu VS and Kalluri R: A peek into

cancer-associated fibroblasts: origins, functions and translational

impact. Dis Model Mech. 11:dmm0294472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Loeffler M, Krüger JA, Niethammer AG and

Reisfeld RA: Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer

chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest.

116:1955–1962. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE and Pienta KJ:

Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 15:366–381. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Costa A, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A,

Pelon F, Bourachot B, Cardon M, Sirven P, Magagna I, Fuhrmann L,

Bernard C, et al: Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive

environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 33:463–479.e10.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Cho H, Seo Y, Loke KM, Kim SW, Oh SM, Kim

JH, Soh J, Kim HS, Lee H, Kim J, et al: Cancer-stimulated CAFs

enhance monocyte differentiation and protumoral TAM activation via

IL6 and GM-CSF secretion. Clin Cancer Res. 24:5407–5421. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Mace TA, Ameen Z, Collins A, Wojcik S,

Mair M, Young GS, Fuchs JR, Eubank TD, Frankel WL, Bekaii-Saab T,

et al: Pancreatic cancer-associated stellate cells promote

differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in a

STAT3-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 73:3007–3018. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Xiang H, Ramil CP, Hai J, Zhang C, Wang H,

Watkins AA, Afshar R, Georgiev P, Sze MA, Song XS, et al:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote immunosuppression by inducing

ROS-generating monocytic MDSCs in lung squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Immunol Res. 8:436–450. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Jung DW, Che ZM and Kim J, Kim K, Kim KY,

Williams D and Kim J: Tumor-stromal crosstalk in invasion of oral

squamous cell carcinoma: A pivotal role of CCL7. Int J Cancer.

127:332–344. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Barbai T, Fejős Z, Puskas LG, Tímár J and

Rásó E: The importance of microenvironment: the role of CCL8 in

metastasis formation of melanoma. Oncotarget. 6:29111–29128. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Tsuyada A, Chow A, Wu J, Somlo G, Chu P,

Loera S, Luu T, Li AX, Wu X, Ye W, et al: CCL2 mediates cross-talk

between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast

cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 72:2768–2779. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Higashino N, Koma YI, Hosono M, Takase N,

Okamoto M, Kodaira H, Nishio M, Shigeoka M, Kakeji Y and Yokozaki

H: Fibroblast activation protein-positive fibroblasts promote tumor

progression through secretion of CCL2 and interleukin-6 in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Lab Invest. 99:777–792. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Pausch TM, Aue E, Wirsik NM, Freire Valls

A, Shen Y, Radhakrishnan P, Hackert T, Schneider M and Schmidt T:

Metastasis-associated fibroblasts promote angiogenesis in

metastasized pancreatic cancer via the CXCL8 and the CCL2 axes. Sci

Rep. 10:54202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Vickman RE, Broman MM, Lanman NA, Franco

OE, Sudyanti PAG, Ni Y, Ji Y, Helfand BT, Petkewicz J, Paterakos

MC, et al: Heterogeneity of human prostate carcinoma-associated

fibroblasts implicates a role for subpopulations in myeloid cell

recruitment. Prostate. 80:173–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Yang X, Lin Y, Shi Y, Li B, Liu W, Yin W,

Dang Y, Chu Y, Fan J and He R: FAP promotes immunosuppression by

cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment via

STAT3-CCL2 signaling. Cancer Res. 76:4124–4135. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Brummer G, Acevedo DS, Hu Q, Portsche M,

Fang WB, Yao M, Zinda B, Myers M, Alvarez N, Fields P, et al:

Chemokine signaling facilitates early-stage breast cancer survival

and invasion through fibroblast-dependent mechanisms. Mol Cancer

Res. 16:296–308. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Majo S and Auguste P: The Yin and Yang of

discoidin domain receptors (DDRs): Implications in tumor growth and

metastasis development. Cancers (Basel). 13:17252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Scordamaglia D, Talia M, Cirillo F,

Zicarelli A, Mondino AA, De Rosis S, Di Dio M, Silvestri F, Meliti

C, Miglietta AM, et al: Interleukin-1β mediates a tumor-supporting

environment prompted by IGF1 in triple-negative breast cancer

(TNBC). J Transl Med. 23:6602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Vakilian A, Khorramdelazad H, Heidari P,

Sheikh Rezaei Z and Hassanshahi G: CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway in

glioblastoma multiforme. Neurochem Int. 103:1–7. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Zijlmans HJ, Fleuren GJ, Baelde HJ, Eilers

PH, Kenter GG and Gorter A: The absence of CCL2 expression in

cervical carcinoma is associated with increased survival and loss

of heterozygosity at 17q11.2. J Pathol. 208:507–517. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Yoshidome H, Kohno H, Shida T, Kimura F,

Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, Nakatani Y and Miyazaki M: Significance of

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in angiogenesis and survival in

colorectal liver metastases. Int J Oncol. 34:923–930. 2009.

|

|

126

|

Zhang J, Patel L and Pienta KJ: CC

chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) promotes prostate cancer tumorigenesis

and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21:41–48. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Soria G, Ofri-Shahak M, Haas I,

Yaal-Hahoshen N, Leider-Trejo L, Leibovich-Rivkin T, Weitzenfeld P,

Meshel T, Shabtai E, Gutman M and Ben-Baruch A: Inflammatory

mediators in breast cancer: coordinated expression of TNFα &

IL-1β with CCL2 & CCL5 and effects on epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition. BMC Cancer. 11:1302011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Jin G, Kawsar HI, Hirsch SA, Zeng C, Jia

X, Feng Z, Ghosh SK, Zheng QY, Zhou A, McIntyre TM and Weinberg A:

An antimicrobial peptide regulates tumor-associated macrophage

trafficking via the chemokine receptor CCR2, a model for

tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 5:e109932010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Vasco C, Canazza A, Rizzo A, Mossa A,

Corsini E, Silvani A, Fariselli L, Salmaggi A and Ciusani E:

Circulating T regulatory cells migration and phenotype in

glioblastoma patients: An in vitro study. J Neurooncol.

115:353–363. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

del Pozo MA, Cabañas C, Montoya MC, Ager

A, Sánchez-Mateos P and Sánchez-Madrid F: ICAMs redistributed by

chemokines to cellular uropods as a mechanism for recruitment of T

lymphocytes. J Cell Biol. 137:493–508. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

131

|

Schmall A, Al-Tamari HM, Herold S,

Kampschulte M, Weigert A, Wietelmann A, Vipotnik N, Grimminger F,

Seeger W, Pullamsetti SS and Savai R: Macrophage and cancer cell

cross-talk via CCR2 and CX3CR1 is a fundamental mechanism driving

lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 191:437–447. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Maolake A, Izumi K, Shigehara K,

Natsagdorj A, Iwamoto H, Kadomoto S, Takezawa Y, Machioka K,

Narimoto K, Namiki M, et al: Tumor-associated macrophages promote

prostate cancer migration through activation of the CCL22-CCR4

axis. Oncotarget. 8:9739–9751. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Qian BZ and Pollard JW: Macrophage

diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell.

141:39–51. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, Vasquez

L, Tawfik D, Kolhatkar N and Coussens LM: CD4(+) T cells regulate

pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor

properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 16:91–102. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

135

|

Reinartz S, Schumann T, Finkernagel F,

Wortmann A, Jansen JM, Meissner W, Krause M, Schwörer AM, Wagner U,

Müller-Brüsselbach S and Müller R: Mixed-polarization phenotype of

ascites-associated macrophages in human ovarian carcinoma:

Correlation of CD163 expression, cytokine levels and early relapse.

Int J Cancer. 134:32–42. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

van Attekum MHA, van Bruggen JAC, Slinger

E, Lebre MC, Reinen E, Kersting S, Eldering E and Kater AP: CD40

signaling instructs chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells to attract

monocytes via the CCR2 axis. Haematologica. 102:2069–2076. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Zhu P, Baek SH, Bourk EM, Ohgi KA,

Garcia-Bassets I, Sanjo H, Akira S, Kotol PF, Glass CK, Rosenfeld

MG and Rose DW: Macrophage/cancer cell interactions mediate hormone

resistance by a nuclear receptor derepression pathway. Cell.

124:615–629. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Loberg RD, Ying C, Craig M, Yan L, Snyder

LA and Pienta KJ: CCL2 as an important mediator of prostate cancer

growth in vivo through the regulation of macrophage infiltration.

Neoplasia. 9:556–562. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

139

|

Ye J, Yang Y, Jin J, Ji M, Gao Y, Feng Y,

Wang H, Chen X and Liu Y: Targeted delivery of chlorogenic acid by

mannosylated liposomes to effectively promote the polarization of

TAMs for the treatment of glioblastoma. Bioact Mater. 5:694–708.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Liu F, Li X, Zhang Y, Ge S, Shi Z, Liu Q

and Jiang S: Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to overcome

immune checkpoint inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 44:2272025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Nywening TM, Wang-Gillam A, Sanford DE,

Belt BA, Panni RZ, Cusworth BM, Toriola AT, Nieman RK, Worley LA,

Yano M, et al: Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2

inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with

borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A

single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b

trial. Lancet Oncol. 17:651–662. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

142

|

Fujimoto H, Sangai T, Ishii G, Ikehara A,

Nagashima T, Miyazaki M and Ochiai A: Stromal MCP-1 in mammary

tumors induces tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and

contributes to tumor progression. Int J Cancer. 125:1276–1284.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Bianconi V, Sahebkar A, Atkin SL and Pirro

M: The regulation and importance of monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1. Curr Opin Hematol. 25:44–51. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

144

|

Ding M, He SJ and Yang J: MCP-1/CCL2

mediated by autocrine loop of PDGF-BB promotes invasion of lung

cancer cell by recruitment of macrophages via CCL2-CCR2 Axis. J

Interferon Cytokine Res. 39:224–232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Avila MA and Berasain C: Targeting

CCL2/CCR2 in tumor-infiltrating macrophages: A tool emerging out of

the box against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 7:293–294. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

146

|

Nywening TM, Belt BA, Cullinan DR, Panni

RZ, Han BJ, Sanford DE, Jacobs RC, Ye J, Patel AA, Gillanders WE,

et al: Targeting both tumour-associated CXCR2(+) neutrophils and

CCR2(+) macrophages disrupts myeloid recruitment and improves

chemotherapeutic responses in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Gut. 67:1112–1123. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

147

|

Sanford DE, Belt BA, Panni RZ, Mayer A,

Deshpande AD, Carpenter D, Mitchem JB, Plambeck-Suess SM, Worley

LA, Goetz BD, et al: Inflammatory monocyte mobilization decreases

patient survival in pancreatic cancer: A role for targeting the

CCL2/CCR2 axis. Clin Cancer Res. 19:3404–3415. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Yin S, Wang N, Riabov V, Mossel DM,

Larionova I, Schledzewski K, Trofimova O, Sevastyanova T, Zajakina

A, Schmuttermaier C, et al: SI-CLP inhibits the growth of mouse

mammary adenocarcinoma by preventing recruitment of

tumor-associated macrophages. Int J Cancer. 146:1396–1408. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Li W, Zhang X, Wu F, Zhou Y, Bao Z, Li H,

Zheng P and Zhao S: Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal

cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis

and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 10:9182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Crane CA, Ahn BJ, Han SJ and Parsa AT:

Soluble factors secreted by glioblastoma cell lines facilitate

recruitment, survival, and expansion of regulatory T cells:

Implications for immunotherapy. Neuro Oncol. 14:584–595. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

151

|

Marangoni F, Zhakyp A, Corsini M, Geels

SN, Carrizosa E, Thelen M, Mani V, Prüßmann JN, Warner RD, Ozga AJ,

et al: Expansion of tumor-associated Treg cells upon disruption of

a CTLA-4-dependent feedback loop. Cell. 184:3998–4015.e19. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

152

|

Rodrigues PF, Wu S, Trsan T, Panda SK,

Fachi JL, Liu Y, Du S, de Oliveira S, Antonova AU, Khantakova D, et

al: Rorγt-positive dendritic cells are required for the induction

of peripheral regulatory T cells in response to oral antigens.

Cell. 188:2720–2737.e22. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

153

|

Filaci G, Fenoglio D, Fravega M, Ansaldo

G, Borgonovo G, Traverso P, Villaggio B, Ferrera A, Kunkl A, Rizzi

M, et al: CD8+ CD28- T regulatory lymphocytes inhibiting T cell

proliferative and cytotoxic functions infiltrate human cancers. J

Immunol,. 179:4323–4334. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Serafini P, Borrello I and Bronte V:

Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: Recruitment, phenotype,

properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer

Biol. 16:53–65. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

155

|

Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I,

Cingarlini S, Dolcetti L, Gallina G, Zanovello P and Bronte V:

Derangement of immune responses by myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 53:64–72. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, Hernandez

C, Signoretti S, Zabaleta J, McDermott D, Quiceno D, Youmans A,

O'Neill A, et al: Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in

renal cell carcinoma patients: A mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer

Res. 65:3044–3048. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Ugel S, De Sanctis F, Mandruzzato S and

Bronte V: Tumor-induced myeloid deviation: when myeloid-derived

suppressor cells meet tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest.

125:3365–3376. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

158

|

Kumar V, Cheng P, Condamine T, Mony S,

Languino LR, McCaffrey JC, Hockstein N, Guarino M, Masters G,

Penman E, et al: CD45 phosphatase inhibits STAT3 transcription

factor activity in myeloid cells and promotes tumor-associated