Introduction

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare and highly

aggressive malignancy arising from steroidogenic cells of the

adrenal cortex, characterized by a 5-year overall survival rate of

>35% (1). Radical surgical

resection remains the only curative approach for localized ACC;

however, postoperative recurrence rates are high, ranging between

70–80% (2). For advanced or

metastatic ACC, therapeutic options are limited. Mitotane, the only

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agent, demonstrates

suboptimal efficacy and substantial toxicity (3). Combination chemotherapy regimens such

as mitotane with etoposide, doxorubicin and cisplatin yields modest

clinical benefit, with an objective response rate of ~30% and a

median progression-free survival of 5.6 months (4). These limitations underscore an urgent

need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying ACC

progression and to identify robust biomarkers for early diagnosis,

risk stratification and development of targeted therapeutics.

Reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism is a

hallmark of malignancy, with aerobic glycolysis (‘Warburg effect’)

facilitating increased glucose uptake and lactate production, which

acidifies the tumor microenvironment (TME) and supports migration

and immune evasion (5–7). Dysregulated expression and activity of

glycolytic enzymes are central to this phenotype (8). Ephrin-A3 (EFNA3), a transmembrane

ligand of the Eph receptor tyrosine kinase family, has been

implicated in metabolic regulation and tumor progression (9,10).

EFNA3 participates in bidirectional cell-cell communication through

interactions with Eph receptors, modulating processes such as

angiogenesis, cellular motility and tissue remodeling (11). Notably, EFNA3 functions as a

glycolysis-related gene. Previous studies indicate that EFNA3

upregulation promotes glycolytic flux and proliferation in lung

adenocarcinoma, correlating with unfavorable prognosis (12–14),

suggesting potential roles as both a metabolic regulator and

oncogenic driver.

Members of the EFNA gene family, including EFNA1 and

EFNA2, exhibit distinct expression and functional profiles across

tumor types. EFNA1 is frequently upregulated in various types of

cancer, such as gastric cancer and melanomas, and is linked to

angiogenesis, immune modulation and metastatic potential via

interactions with EphA2 and hypoxia-inducible signaling (15–18).

Conversely, EFNA2 expression is reduced in certain types of cancer

such as gastric carcinoma, with inverse associations to

CD8+ T-cell and dendritic cell infiltration, implicating

it in immune surveillance escape (19–21).

High EFNA3 expression levels are predictive of poorer survival in

gastric cancer and correlate negatively with infiltration of B

cells, T cells and dendritic cells, as well as with immune

checkpoint activity, which indicates a role in immune evasion

(22,23). Beyond its prognostic role, EFNA3

expression has been correlated with immune cell infiltration and

chemotherapeutic response, indicating potential relevance to tumor

immunology and therapeutic resistance (24–26).

The present study aimed to perform an integrative

pan-cancer analysis of EFNA3 to evaluate its transcriptional

deregulation, genetic and epigenetic alterations, prognostic

relevance, associations with tumor immune infiltration and drug

sensitivity, and to construct an EFNA3 ceRNA regulatory network.

Furthermore, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of

EFNA3 on the proliferative, migratory and anti-apoptotic capacities

of ACC cells via in vitro experiments.

Materials and methods

Pan-cancer expression profiling of

EFNA3

Transcriptome data from 15,776 samples were

retrieved via the UCSC Xena Browser (https://xenabrowser.net; The Regents of the University

of California), integrating The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and

Genotype-Tissue Expression databases (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/). Raw RNA-Seq data

(TPM+1) were log-transformed and normalized using the rms

package in R (version 4.2.1; Posit Software, PBC). Batch-corrected

data were visualized using ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit

Software, PBC) as boxplots to depict EFNA3 expression across tumor

and normal tissues. Differential expression was analyzed with

DESeq2 (version 1.38.3; Bioconducter), using thresholds of

|log2FC|≥1 and FDR ≤0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). Tumor

stage association was analyzed using the ‘Stage Plot’ module in

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/). The

flowchart of the present study is shown in Fig. S1.

Prognostic and diagnostic evaluation

of EFNA3

TCGA clinical and expression datasets were used to

assess prognostic and diagnostic relevance of EFNA3. Univariate Cox

proportional hazards models were constructed using the

survival package (version 3.5–5; Posit Software, PBC), with

calculated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Samples lacking complete survival data were excluded.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS, disease-free survival (DFS)

and progression-free interval (PFI) were plotted using

survminer (version 0.4.9; Posit Software, PBC) and

ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit Software, PBC). Diagnostic

value was evaluated using ROC curves generated by the pROC

package (version 1.18.0; Posit Software, PBC).

Clinicopathological correlation in

ACC

Based on median the expression level of EFNA3,

patients with ACC were stratified into high- and low-EFNA3

expression groups (n=40 and n=39, respectively). Clinical

parameters were compared using appropriate tests using the

stats (version 4.2.1) and car (version 3.1.0) R

packages (Posit Software, PBC). Visualization was performed with

ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit Software, PBC). The diagnostic

performance of EFNA3 in ACC was evaluated via ROC analysis

(pROC; version 1.18.0; Posit Software, PBC) using TCGA and

UCSC-derived datasets.

Somatic mutation and copy number

analysis

Mutation data were obtained from cBioPortal

(http://www.cbioportal.org) and TCGA.

EFNA3 alterations [mutation type, copy number alterations (CNAs)

and frequency] were analyzed using 2,683 samples from 2,565

patients. Additional ACC-specific data (n=76) were retrieved from

the UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/) and the International Cancer

Genome Consortium (https://dcc.icgc.org/) databases. Kaplan-Meier

survival analyses were used to assess survival outcomes based on

EFNA3 mutation status. Differential mutation profiles in EFNA3-high

vs. -low expression groups were also analyzed.

Epigenetic and mRNA modification

analysis

DNA methylation profiles for EFNA3 in ACC were

obtained from the MethSurv (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/methsurv/) database. mRNA

modification regulator correlations including n1-methyladenosine

(m1A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and n6-methyladenosine (m6A), were

analyzed across various types of cancer from TCGA database using

the SangerBox software (version 3.0; http://vip.sangerbox.com). Pearson correlation

coefficients and significance levels were reported.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

TME scores (stromal, immune and ESTIMATE scores)

were computed using the ESTIMATE R package (version 1.0.13;

Posit Software, PBC). Immune infiltration profiling was performed

using markers from 22 immune cell types provided by the CIBERSORTx

website (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) (27). Data were visualized as heatmaps

using ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit Software, PBC).

Spearman's correlation coefficients were used to assess statistical

associations.

Competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA)

regulatory network construction

Candidate EFNA3-targeting microRNAs (miRNAs) were

predicted using PITA (version 1.0; https://genie.weizmann.ac.il/pubs/mir07/mir07_data.html),

miRanda (version 3.3; http://www.microrna.org/) and TargetScan (version 8.0;

http://www.targetscan.org/) software.

miRNAs with a negative correlation to EFNA3 were prioritized using

the StarBase (version 2.0; http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/). lncRNA-miRNA

interactions were derived from miRNet (version 2.0; http://www.mirnet.ca/) and StarBase (version 2.0;

http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) under the

criteria: Species=human; CLIP-Data=yes; and min stringency=5. Venn

diagrams were used for intersecting target prediction using

ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit Software, PBC), and

VennDiagram (version 1.7.3; Posit Software, PBC). Final

lncRNA-miRNA-EFNA3 networks were visualized using mulberry plots

using ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; Posit Software, PBC) and

ggalluvial (version 0.12.3; Posit Software, PBC).

Drug sensitivity and interaction

network analysis

Drug sensitivity data were obtained from the

GSCALite (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/web/GSCALite/)

database, which integrates TCGA, Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in

Cancer (GDSC) and Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP)

datasets. EFNA3-associated drug responses were identified based on

Pearson correlations analysis with mRNA expression. FDA-approved

agents were selected via DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/) annotations. Network graphs

were generated using graph (version 1.4.1; Posit Software,

PBC) and graph (version 2.1.0; Posit Software, PBC)

packages.

Functional enrichment of co-expressed

genes

Co-expressed genes were identified using LinkedOmics

(http://www.linkedomics.org). Functional

enrichment was performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) terms via the

clusterProfiler (version 4.6.2; Posit Software, PBC)

software. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were generated

using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) and visualized using

default Benjamini-Hochberg correction for P-values.

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human ACC cell lines SW-13 (hormonally inactive)

and NCI-H295R (hormonally active) were obtained from Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Cell line authentication was

confirmed via short tandem repeat profiling. Cells were maintained

in DMEM/F12 medium (Shanghai Zhongqiao Xinzhou Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

G24-70500; Genial Biologicals, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(Shanghai Zhongqiao Xinzhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Cultures were

incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2.

EFNA3 overexpression and knockdown via

lentiviral transfection

The EFNA3 overexpression plasmid was synthesized by

Shanghai Sangong Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The short hairpin RNA

(shRNA) targeting EFNA3 and the non-targeting negative control (NC)

were synthesized by Shanghai Gema Gene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Sequences used were as follows: shNC sense (S),

5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ and anti-sense (AS),

5′-ACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAA-3′; shEFNA3 S, 5′-GGCATGCGGTGTACTGGAACA-3′

and AS, 5′-TGTTCCAGTACACCGCATGCC-3′. The EFNA3 overexpression

plasmid was designed and synthesized by Shanghai Sangong

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and constructed by cloning the EFNA3

coding sequence into the pcDNA3.1 plasmid backbone (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). For transfection, 2.5 µg of plasmid DNA was

complexed using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and

then added to the cell culture. Transfection was performed at 37°C

for 48 h. Upon reaching 30–40% confluency in 6-well plates, cells

were infected with lentivirus in medium containing Polybrene

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Puromycin (4 µg/ml; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was added 48 h post-infection for initial

screening. Stable-transfected clones were maintained in a 2

µg/ml-puromycin environment.

Real-time quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

According to the manufacturer's protocol, total RNA

was isolated from NCI-H295R and SW-13 cells using TRIzol reagent

(cat. no. R0016; Biocytogen). cDNA was synthesized from mRNA using

a cDNA reverse transcription kit (cat. no. 4368814; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR

amplification was performed using the SYBR Green fluorescent

quantitative PCR kit (cat. no. A46012, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The primer sequences are as follows: EFNA3 forward (F),

5′-ATGAAGGTGTTCGTCTGCT-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-CTCAAAGTCTTCCAGCACG-3′; GAPDH F, 5′-TCAAGATCATCAGCAATGCC-3′ and

R, 5′-CGATACCAAAGTTGTCATGGA-3′; GAPDH was used as the internal

reference gene. The relative expression level of EFNA3 mRNA was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (28). The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40

cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and combined

annealing/extension at 60°C for 60 sec.

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was assessed using 24-well Transwell

chambers with 8-µm pore inserts (Corning, Inc.). After serum

starvation for 24 h, cells were harvested and resuspended in

serum-free DMEM at 1×105 cells/ml. Then, 200 µl of cell

suspension was seeded into the upper chamber. The lower chamber

contained 600 µl of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as

chemoattractant. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C with 5%

CO2, non-migrated cells were removed. Migrated cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and stained with

0.1% crystal violet for 20 min, both at room temperature. Cell

images were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope

(Olympus IX73; Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×400).

Representative scale bars (200 µm) are shown. Each experiment was

performed in triplicate and repeated three times independently.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the Cell

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells

were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well) in 100 µl of

complete medium. At 12, 24, 48 and 72 h post-seeding, the medium

was replaced with 90 µl of serum-free medium with 10 µl of CCK-8

solution, followed by 1 h incubation at 37°C. Absorbance was

measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Each cell experiment

was independently repeated three times.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was quantified using Annexin

V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD

Biosciences). Transfected cells were seeded into 6-well plates and

cultured to ~80% confluence. Cells were harvested, washed twice

with PBS and stained in binding buffer with Annexin V-FITC and PI

for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were analyzed

within 1 h using flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur™; BD Biosciences)

and apoptotic populations were quantified. The total apoptosis rate

was defined as the sum of early and late apoptotic populations.

Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; BD

Biosciences). Each cell experiment was independently repeated three

times.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed using PI staining

to quantify DNA content and analyzed via flow cytometry. Cells from

different groups were collected and washed with ice-cold PBS. After

centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and aspiration of the

supernatant, the cell pellets were fixed in 1 ml of ice-cold 70%

ethanol overnight at 4°C. Following PBS washes three times for 5

min each at room temperature with centrifugation at 500 × g for 5

min per wash, cells were incubated in PI/RNase Staining Buffer (BD

Biosciences) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Finally, the stained

cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD

FACSCaliburTM; BD Biosciences). Data were interpreted

using the CellQuest Pro software (version 6.0; BD Biosciences).

Each cell experiment was independently repeated three times.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was assessed using a wound healing

assay in two human ACC cell lines, SW-13 and NCI-H295R. Cells were

harvested during the logarithmic growth phase, trypsinized and

seeded uniformly into 6-well plates. The cells were cultured until

>90% confluence was reached. Prior to wounding, cells were

serum-starved in serum-free DMEM for 24 h. A straight wound was

introduced in the center area using a sterile pipette tip. The

detached cells were removed by washing three times with PBS.

Subsequently, serum-free cell culture medium was added. Wound

images were captured at 0 and 48 h under an inverted fluorescence

microscope (Olympus IX73; Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

The same magnification and fields of view were used for each time

point. Representative scale bars (500 µm) are shown on respective

images. The measurement of wound width was performed by annotating

the wound edges on the images. Migration rates were quantified

using ImageJ (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health) and

calculated as follows: Cell migration rate=(scratch width at 0

h-scratch width at 48 h)/scratch width at 0 h ×100). Each cell

experiment was independently repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R

(version 4.2.1; Posit Software, PBC). Quantitative data are

expressed as mean ± standard deviation. For the comparisons in

Fig. 1, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test

(Mann-Whitney U test) was used for unpaired samples, while the

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for paired samples. For in

vitro comparisons, unpaired Student's t-test was used for

two-group analyses. For comparisons involving ≥3 groups, data were

assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances. The normality

of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and

the homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene's test. If

these assumptions were met, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed

by Tukey's post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. If the

assumptions were violated, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used,

followed by Dunn's post hoc test. The categorical variables were

compared using the χ2 test. When the applicable

conditions of the χ2 test were violated (>20% of the

expected frequency is <5) the Fisher exact test was used

instead. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

EFNA3 expression patterns and

prognostic relevance across various types of human cancer

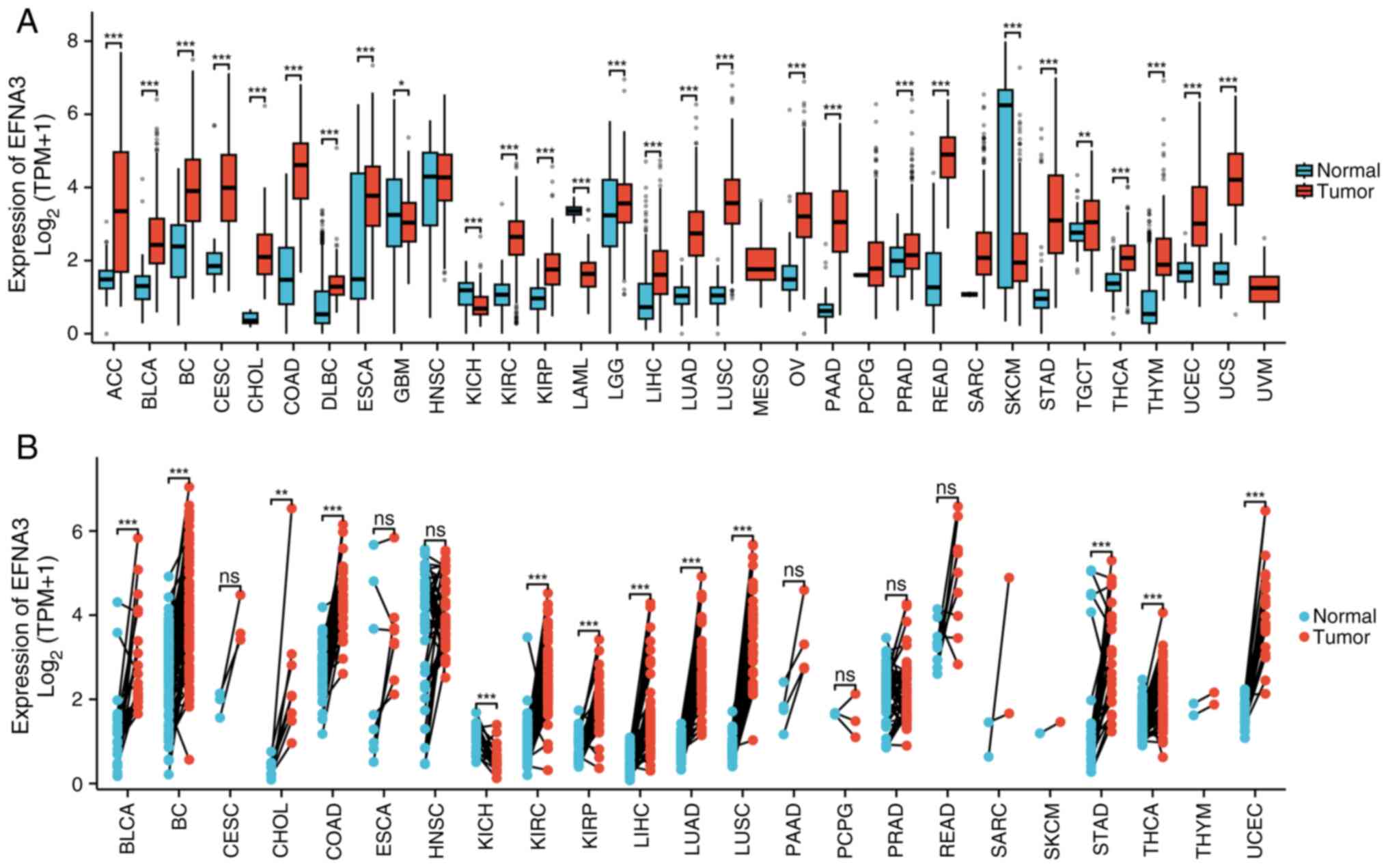

The differential expression of EFNA3 was assessed in

a pan-cancer analysis by comparing normal tissues from the GTEx

database against tumor tissues from the TCGA dataset. EFNA3

expression levels were significantly downregulated in glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM), kidney chromophobe (KICH), acute myeloid

leukemia-like (LAML) and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) compared

with that of normal tissues (Fig.

1A). Pan-cancer analysis using the TCGA data of paired tumor

and paracancerous tissues from the same patients demonstrated that

EFNA3 expression levels were significantly upregulated in the

majority of tumor types compared with that of paired paracancerous

tissues; however, significant downregulation was observed in GBM,

KICH, LAML and SKCM (Fig. 1B). The

expression levels of EFNA3 in cancer and normal tissues in various

types of cancer are shown in Table

SI, Table SII, Table SIII. Forest plots generated from

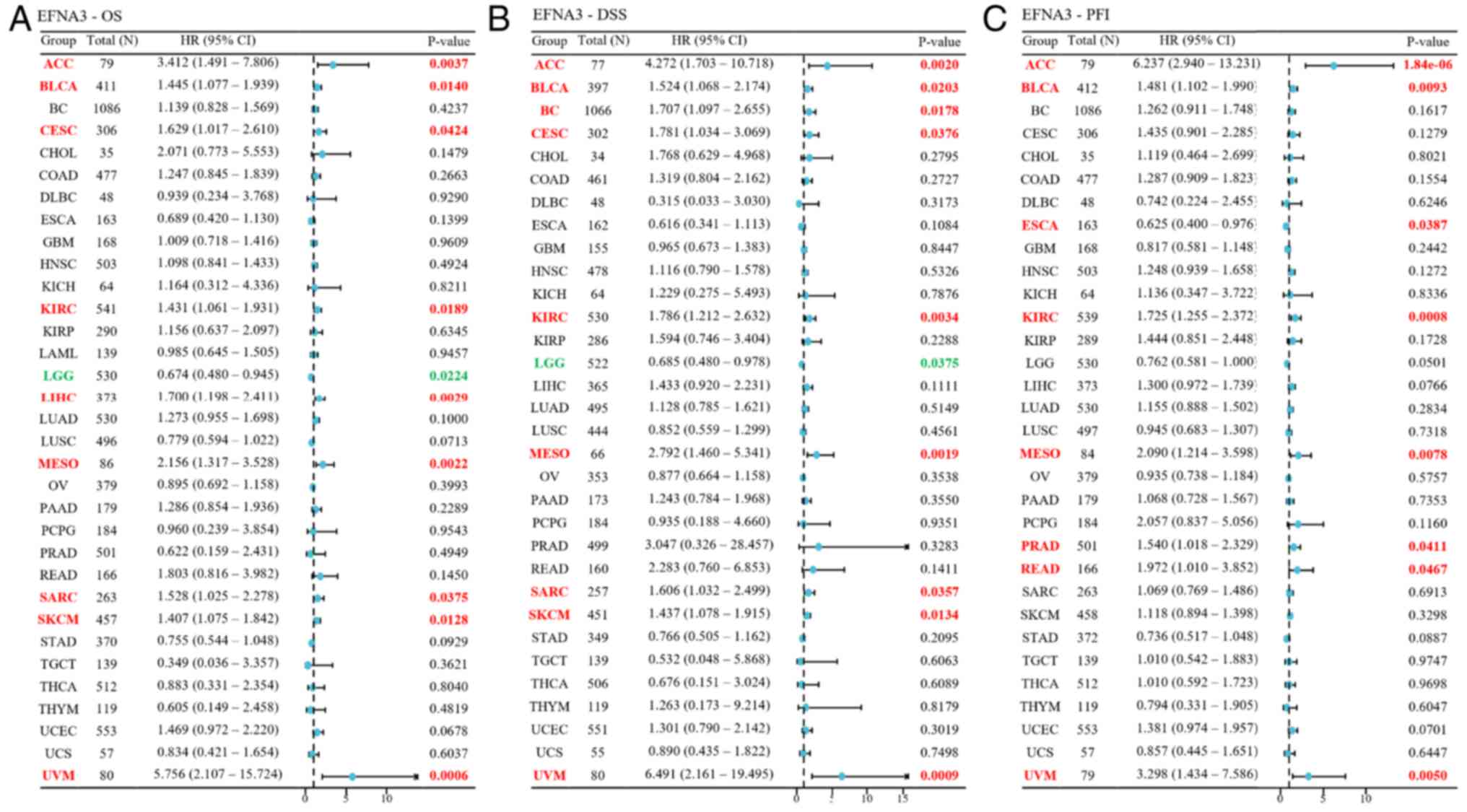

Cox proportional hazard models demonstrated that EFNA3 expression

was significantly associated with OS (Fig. 2A), disease-specific survival (DSS;

Fig. 2B) and PFI (Fig. 2C) across various cancer types.

Prognostic and pathological

correlations of EFNA3 in pan-cancer analysis

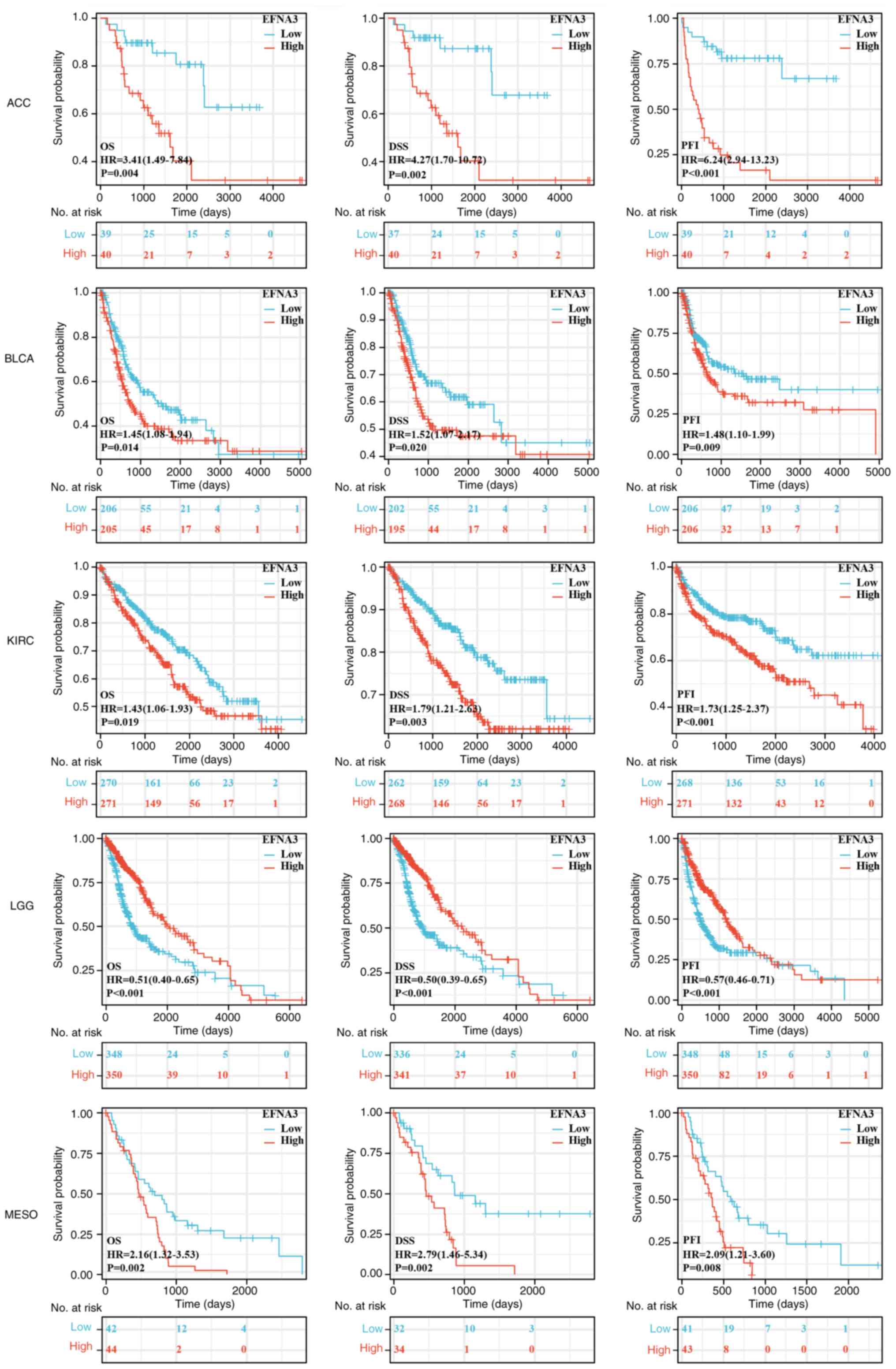

Survival data from TCGA were used to assess the

prognostic role of EFNA3. The association of EFNA3 expression

levels with survival events and time in various cancer types are

shown in Table SIV, Table SV, Table SVI. Due to incomplete survival

annotations, certain end points, specifically DSS and PFI, were

unavailable for LAML. Univariate Cox regression showed that

increased EFNA3 expression was associated with poor OS, DSS and PFI

in bladder cancer (BLCA), kidney clear cell carcinoma (KIRP), ACC

and mesothelioma (HR>1; P<0.05). By contrast, increased EFNA3

expression conferred a protective role in lower-grade glioma (LGG;

HR<1; P<0.05; Fig. 2). EFNA3

was an adverse marker for PFI in breast cancer (BC), esophageal

carcinoma (ESCA), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), rectum

adenocarcinoma (READ) and cervical endocervical squamous carcinoma

(CESC), and for DSS in liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), SKCM

and CESC (Figs. 3 and S2). Specifically, the Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis and log-rank testing demonstrated that, compared

to those in the EFNA3-low expression group, high EFNA3 expression

was significantly associated with poorer PFI in PRAD, READ, BC,

ESCA and CESC, and poorer DSS in LIHC, SKCM and CESC (Fig. 3). Significant correlations between

EFNA3 and pathological stage were present in certain tumors,

including ACC, cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), ESCA, KIRP, LIHC,

testicular germ cell tumors, thyroid carcinoma and SKCM (Fig. S3).

| Figure 3.Prognostic value analysis. Survival

curves for ACC, BLCA, KIRC, LGG and MESO in EFNA3-high and -low

expression groups. The log-rank test was employed to compare the

survival curves and determine the P-value. EFNA3, ephrin-A3; ACC,

adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder cancer; KIRC, kidney clear

cell carcinoma; LGG, lower-grade glioma; MESO, mesothelioma; OS,

overall survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; PFI,

progression-free interval; HR, hazard ratio. |

Genetic alterations of EFNA3 and their

prognostic significance

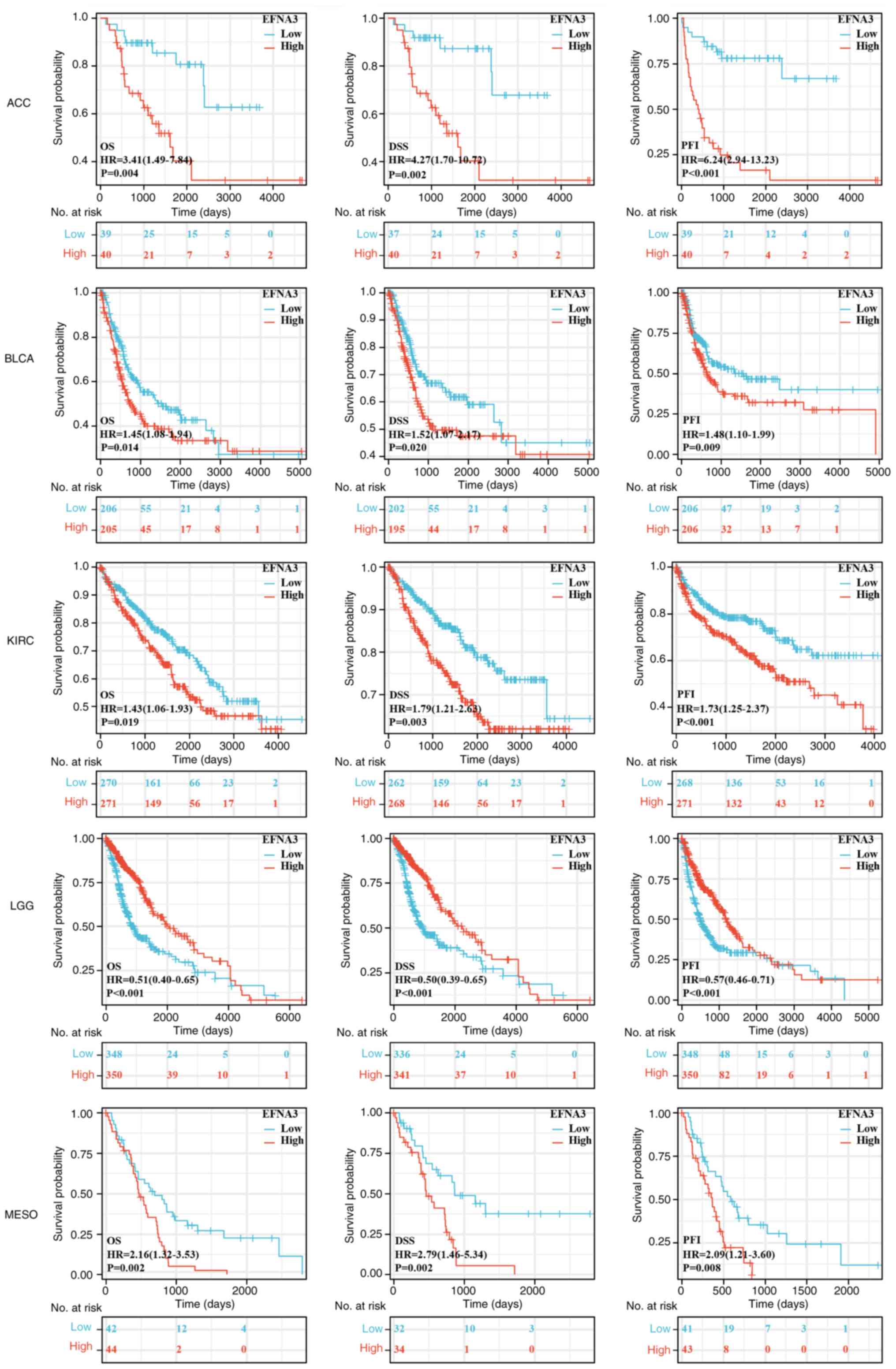

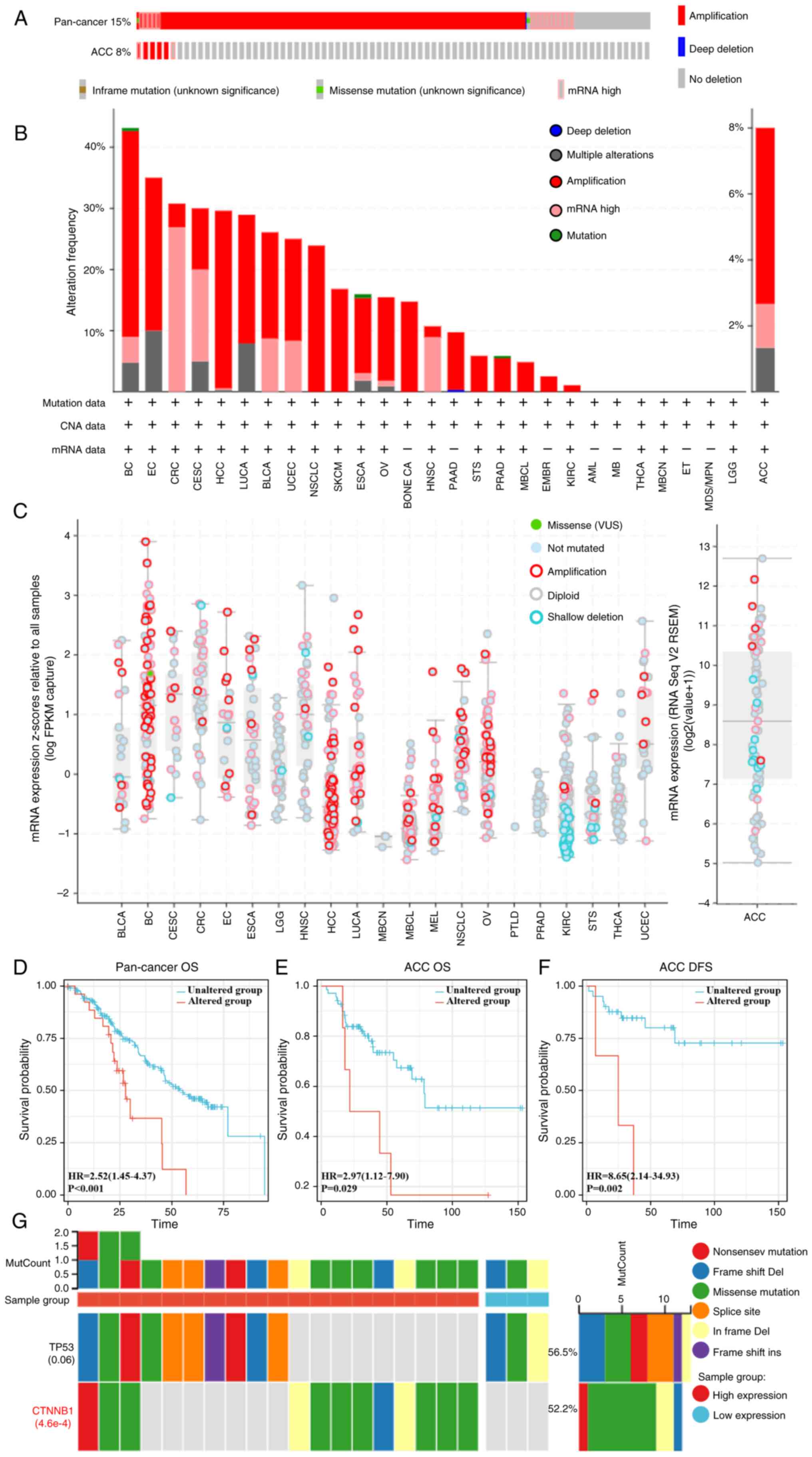

Analysis 2,683 samples from a pan-cancer database of

2,565 patients demonstrated that 15% of the cohort harbored EFNA3

alterations (Fig. 4A), with the

highest frequency observed in BC (>40%; Fig. 4B). In ACC, the mutation frequency

was 8%. CNAs of the ‘mRNA high’ and ‘amplification’ subtypes

occurred most frequently in ACC. EFNA3 CNAs positively correlated

with mRNA expression (Fig. 4C).

Differential expression of genes between EFNA3 altered and

unaltered groups in ACC are shown in Table SVII. Survival analyses demonstrated

that EFNA3-mutated cases had significantly lower OS in the

pan-cancer analysis (HR=2.52, 95% CI, 1.45–4.37; P<0.001) and in

ACC specifically (OS, HR=2.97, 95% CI, 1.12–7.90, P=0.029; DFS

HR=8.65, 95% CI, 2.14–34.93, P=0.002; Fig. 4D-F). In ACC, β-catenin (CTNNB1) was

among the most frequently co-mutated genes with EFNA3

(P=4.6×10−4; Fig.

4G).

| Figure 4.Analysis of genetic alterations. (A)

Genetic alterations of EFNA3 in a pan-cancer database and ACC,

accounting for 15% (alteration/analysis= 384/2,565) and 8% (6/67)

of the alterations, respectively. (B) Frequency of altered EFNA3

mutation types in different types of cancer. (C) mRNA expression of

EFNA3 putative CNAs in pan-cancer tissues and ACC. Proportional

risk hypothesis testing was performed using the survival package

and fitted survival regressions, and the results were visualized

using the survminer package as well as the ggplot2 package. (D)

Kaplan-Meier curves of EFNA3 mutation status versus OS in

pan-cancer analysis. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves of EFNA3 mutation

status and OS in ACC. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves of EFNA3 mutations in

ACC versus DFS. (G) The top 2 genes with the highest mutation

frequency in the EFNA3-high and -low expression group in ACC.

EFNA3, ephrin-A3; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; OS, overall

survival; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CNA, copy

number alterations; Del, deletion; MutCount, mutation count;

CTNNB1, β-catenin; VUS, variants of uncertain significance. |

DNA methylation and RNA modifications

in the epigenetic regulation of EFNA3

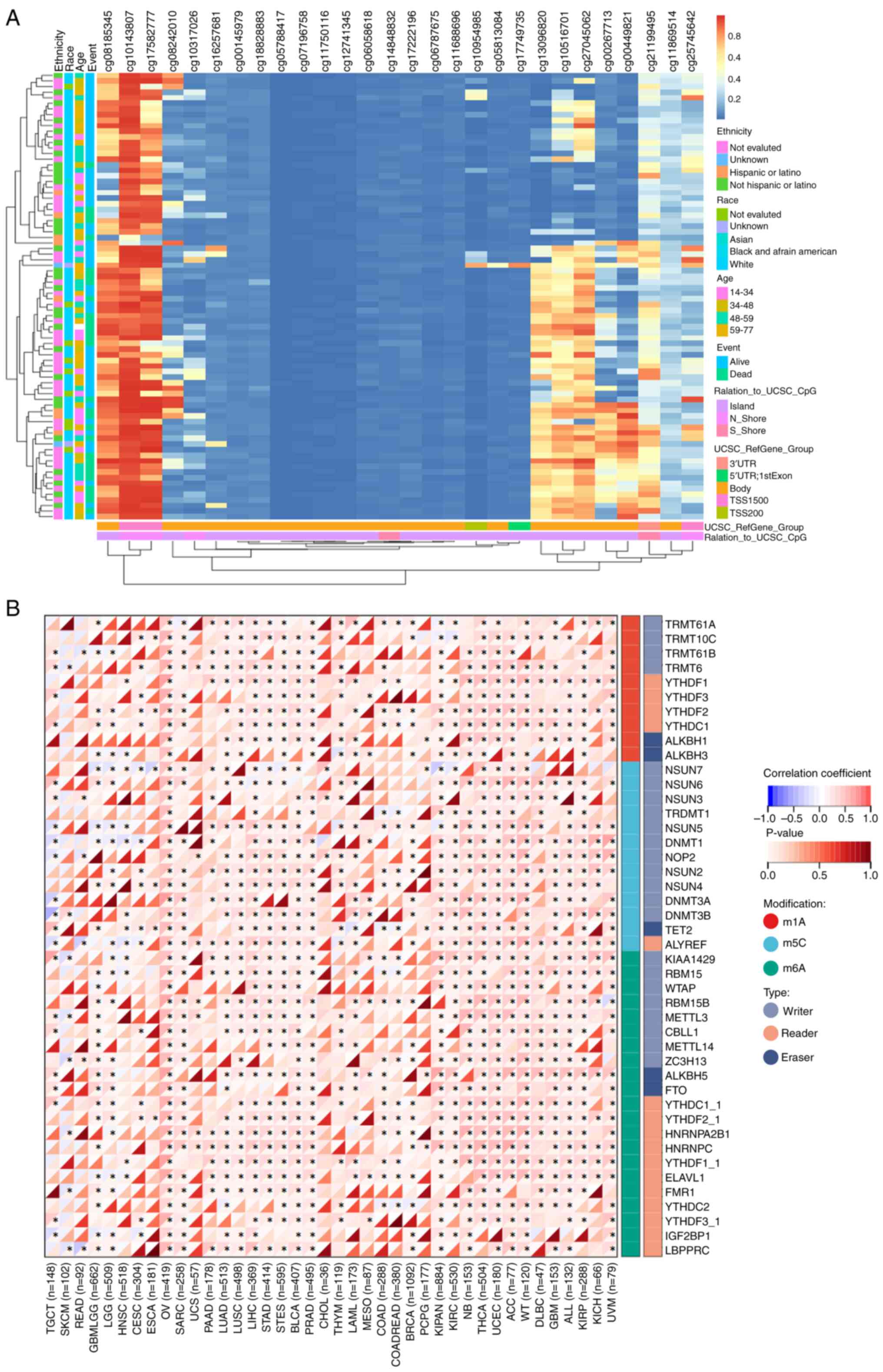

The MethSurv software was used to identify 29 CpG

methylation sites for EFNA3 in ACC (Fig. 5A and Table SVIII). The expression levels of

EFNA3 positively correlated with multiple mRNA methylation

regulators including m1A-, m5C- and m6A-related enzymes (Fig. 5B). The correlation and P-values

between the expression level of EFNA3 and mRNA methylation

regulatory factors are shown in Table

SIX and SX. Top regulators

included HNRNPC, ALKBH5, NSUN6, HNRNPA2B1, ELAVL1, METTL3, YTHDF2,

LRPPRC and ALYREF.

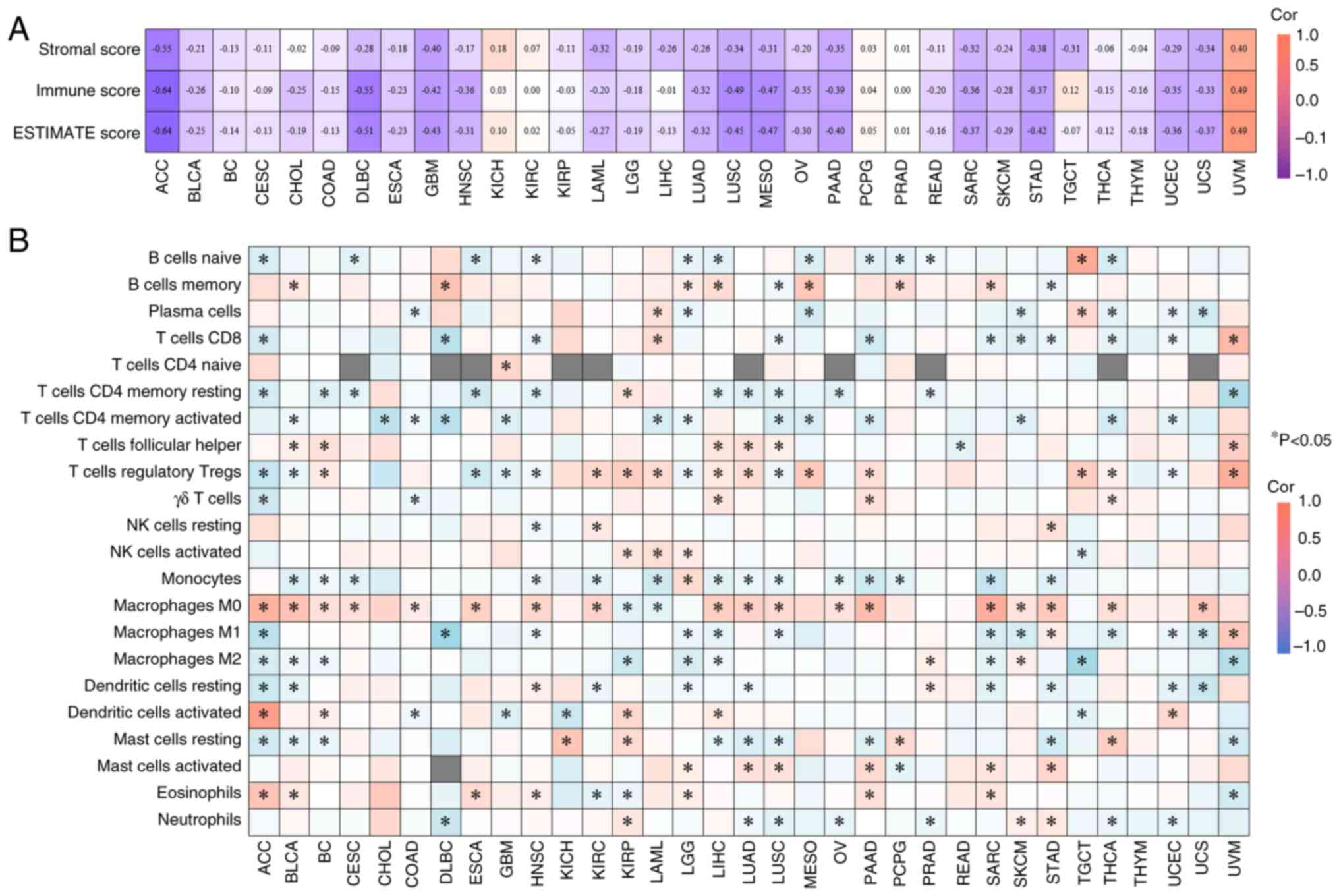

Correlation between EFNA3 expression

levels and the immune microenvironment

In ACC, EFNA3 expression was inversely correlated

with stromal, immune and ESTIMATE scores (Fig. 6A). Using the CIBERSORT algorithm,

EFNA3 expression was significantly associated with the infiltration

levels of multiple immune cell subtypes (Fig. 6B), which indicated potential

immunomodulatory roles. For instance, in ACC, EFNA3 expression

showed the strongest positive correlation with the infiltration

levels of activated dendritic cells and the strongest negative

correlation with M1 macrophages, both of which were statistically

significant (P<0.05).

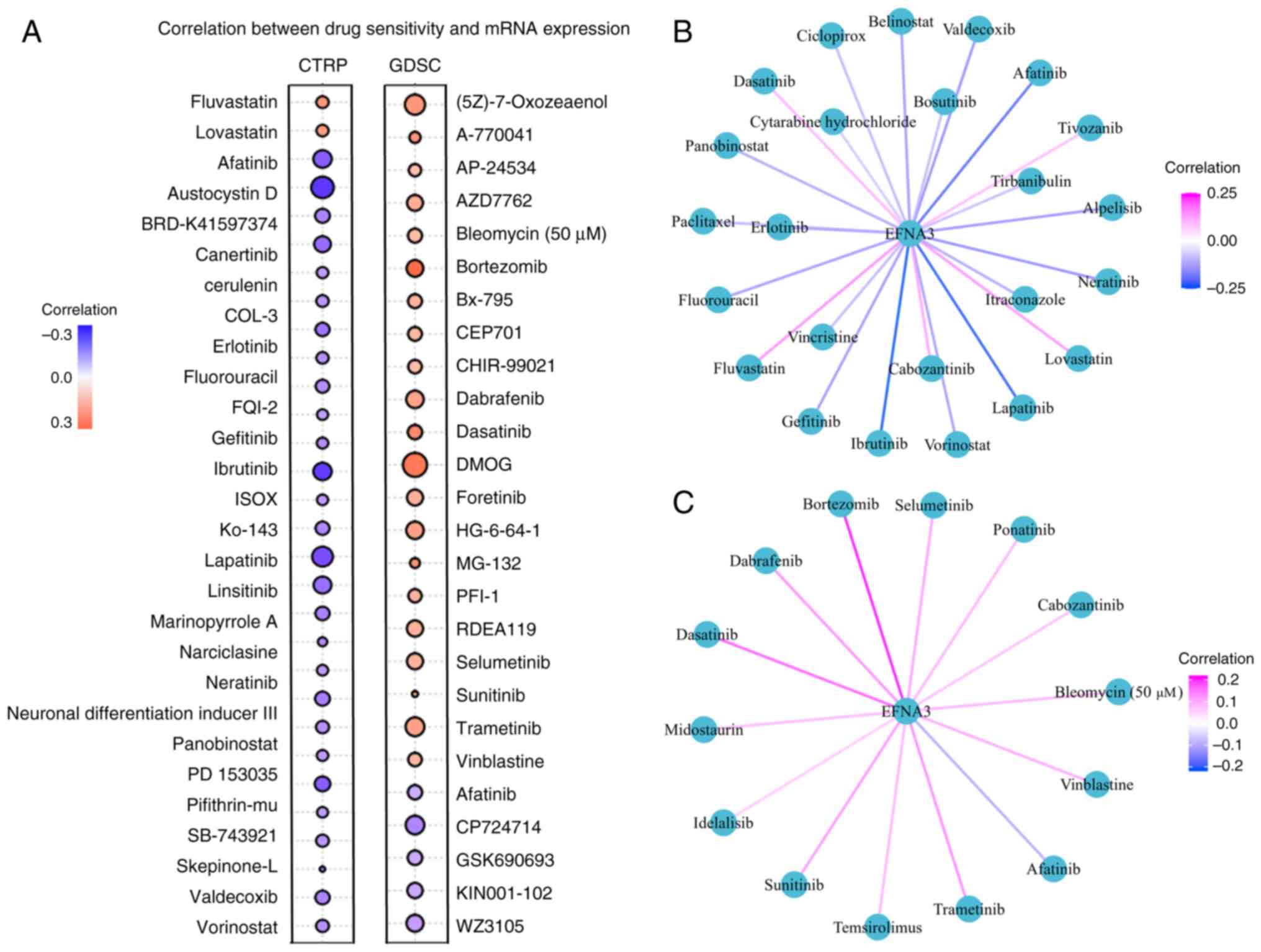

EFNA3 expression and drug sensitivity

prediction

were screened CTRP analysis demonstrated a positive

correlation between EFNA3 expression and sensitivity to lovastatin

and fluvastatin, and a negative correlation with austocystin D,

ibrutinib and lapatinib (Fig. 7A).

In the GDSC dataset, EFNA3 expression levels correlated positively

with bortezomib, dimethyloxalylglycine and dasatinib sensitivity

but negatively with CP-724714, WZ3105 and KIN001-102. Additionally,

using a cut-off of FDR<0.05, 24 (CTRP) and 14 (GDSC)

FDA-approved antitumor drugs were significantly associated with

EFNA3 expression levels (Fig. 7B and

C; Tables SXI and SXII).

Association of EFNA3 with

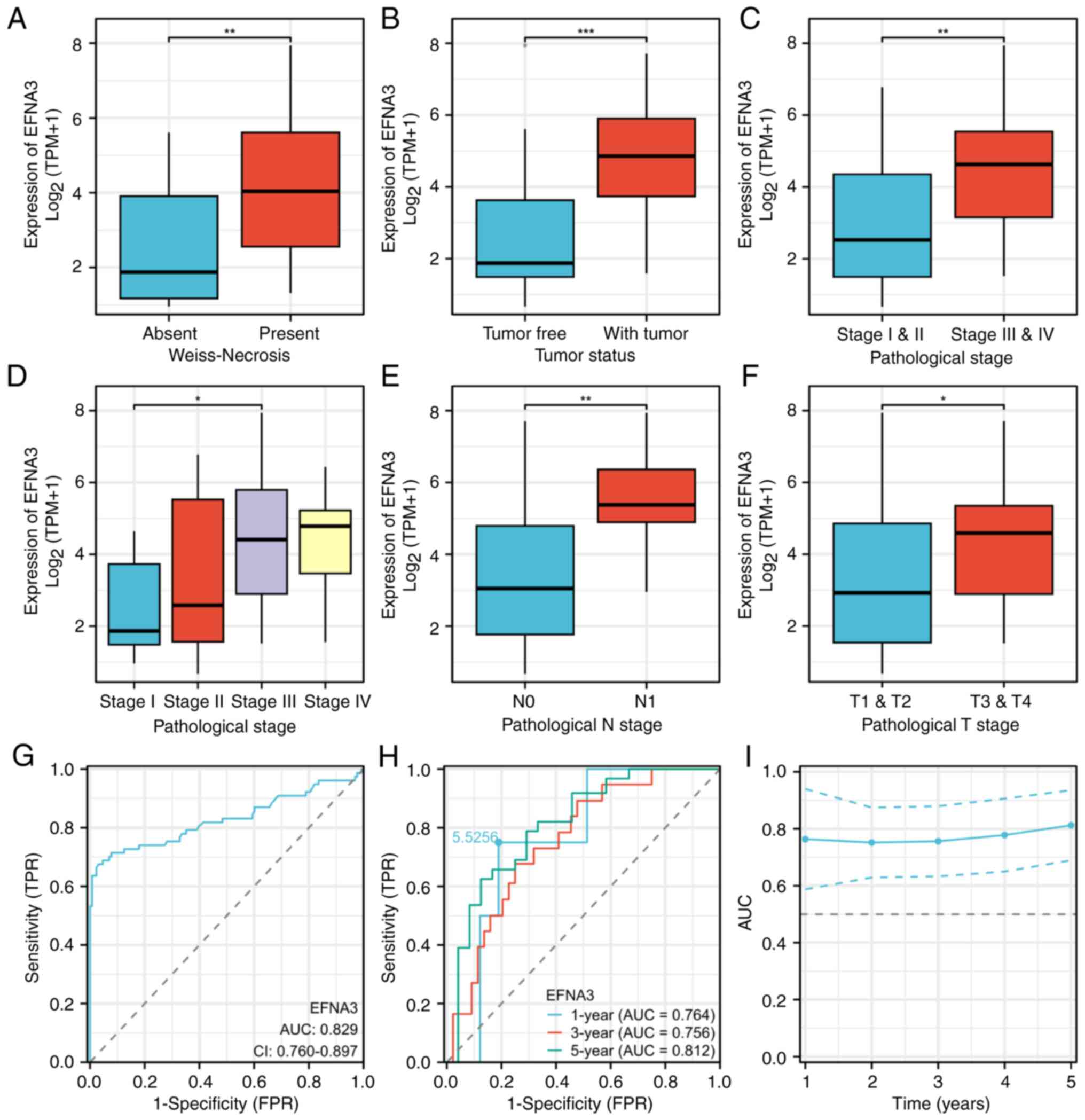

clinicopathological features in ACC

EFNA3 expression levels were significantly

associated with primary treatment outcome (P=0.015), Weiss necrosis

(P=0.039), tumor status (P<0.001), diffuse architecture

(P=0.026), pathological stage (P=0.034), N-stage (P=0.037) and sex

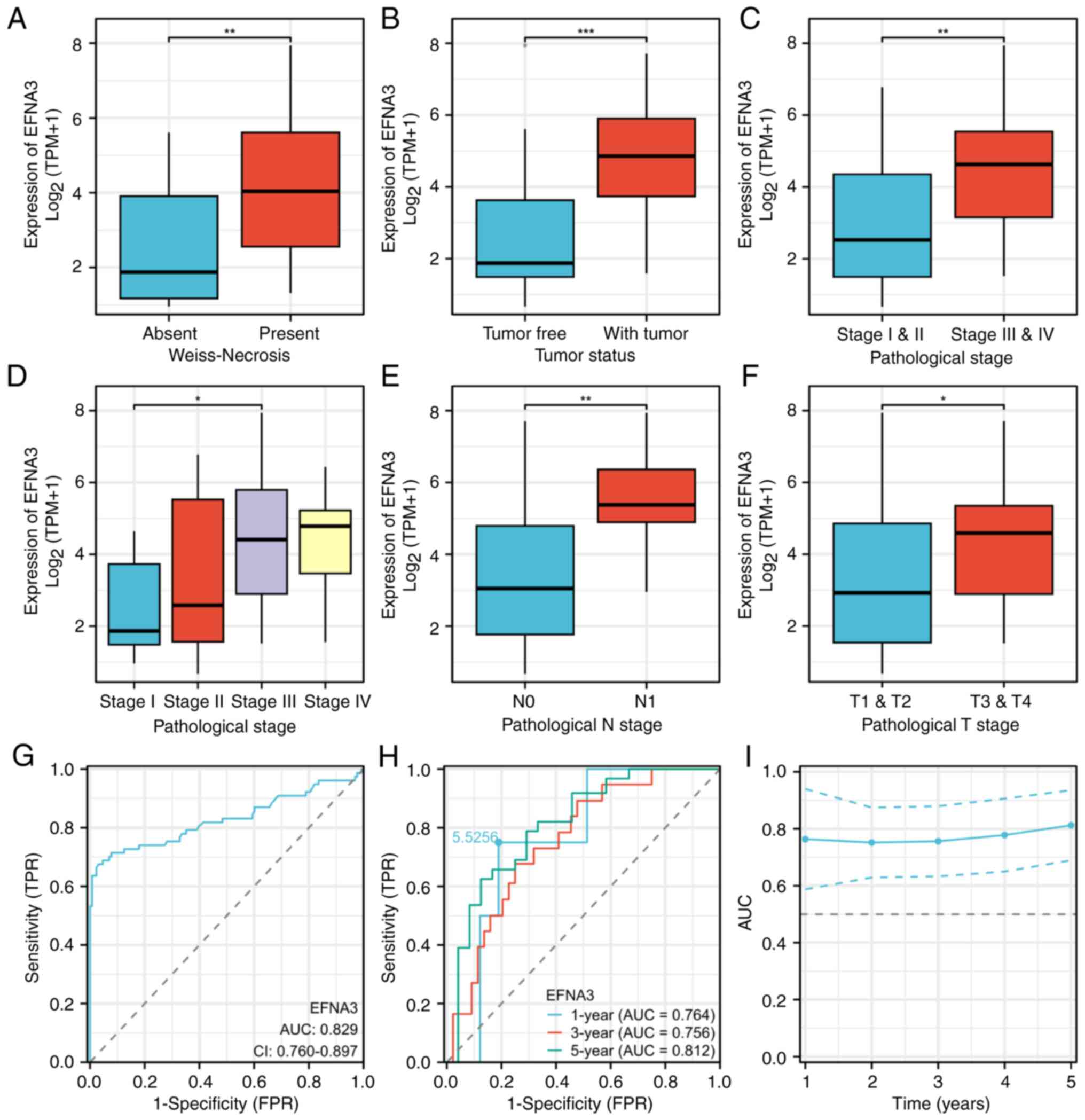

(P=0.030; Table I and Fig. 8A-F). Diagnostic ROC analysis

demonstrated a high discriminatory power of EFNA3 [area under the

curve (AUC)=0.829; Fig. 8G]. The

ROC curve analysis demonstrated that EFNA3 exhibited diagnostic

accuracy for ACC across multiple time points. The AUC was 0.764 for

1-year survival, 0.756 for 3-year survival and 0.812 for 5-year

survival. Furthermore, on the 1-year ROC curve, a cut-off value of

5.526 was identified for EFNA3 expression (Fig. 8H). The time-dependent ROC analysis

assessed the trend of EFNA3 diagnostic accuracy over time. The AUC

remained at a high level (≥0.7) across all time points (Fig. 8I).

| Figure 8.Association between EFNA3 expression

and clinicopathological features in ACC. Association of EFNA3

expression levels with (A) Weiss-Necrosis, (B) tumor status, (C)

pathological stage: I & II vs. III & IV), (D) pathological

stage: I vs. II vs. III vs. IV (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's

analysis), (E) pathological N stage and (F) pathological T stage:

T1& T2 vs. T3 & T4 (Mann-Whitney U test). (G) Diagnostic

value of EFNA3 in ACC. (H) Time-dependent prognostic value of EFNA3

at 1-, 3- and 5-years. (I) CI of time-dependent diagnostic value;

normal group, n=128; tumor group, n=77. The error bars indicate the

standard deviation. ROC analysis was performed using the pROC

package; the AUC and cumulative survival rate corresponding to each

time point were calculated using the time ROC package. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. EFNA3, ephrin-A3; ACC,

adrenocortical carcinoma; AUC, area under the curve; N, node; T,

tumor; TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive rate. |

| Table I.Correlation between EFNA3 expression

levels and clinicopathological characteristics. |

Table I.

Correlation between EFNA3 expression

levels and clinicopathological characteristics.

| Characteristic | Low expression of

EFNA3, n (%) | High expression of

EFNA3, n (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Total patients | 39 (49.4) | 40 (50.6) |

|

| Pathological N

stage |

|

| 0.037 |

| 0 | 37 (46.8) | 31 (39.2) |

|

| 1 | 1 (1.3) | 8 (10.1) |

|

|

Unknown | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

|

| Pathological

stage |

|

| 0.034 |

| I | 6 (7.6) | 3 (3.8) |

|

| II | 23 (29.1) | 14 (17.7) |

|

|

III | 5 (6.3) | 11 (13.9) |

|

| IV | 4 (5.1) | 11 (13.9) |

|

|

Unknown | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

|

| Tumor status |

|

| <0.001 |

| Tumor

free | 29 (36.7) | 10 (12.7) |

|

| With

tumor | 8 (10.1) | 30 (38.0) |

|

|

Unknown | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Primary therapy

outcome |

|

| 0.015 |

|

Progressive disease | 4 (5.1) | 14 (17.7) |

|

| Stable

disease | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

|

| Partial

response | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

Complete response | 30 (38) | 16 (20.3) |

|

|

Unknown | 3 (3.8) | 9 (11.4) |

|

| Sex |

|

| 0.030 |

|

Female | 19 (24.1) | 29 (36.7) |

|

|

Male | 20 (25.3) | 11 (13.9) |

|

| Weiss-Necrosis |

|

| 0.039 |

|

Absent | 12 (15.2) | 5 (6.3) |

|

|

Present | 24 (30.4) | 33 (41.8) |

|

|

Unknown | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.5) |

|

| Weiss-Diffuse

architecture |

|

| 0.026 |

|

Absent | 5 (6.3) | 14 (17.7) |

|

|

Present | 24 (30.4) | 18 (22.8) |

|

|

Unknown | 10 (12.7) | 8 (10.1) |

|

EFNA3 related ceRNA network

construction in ACC

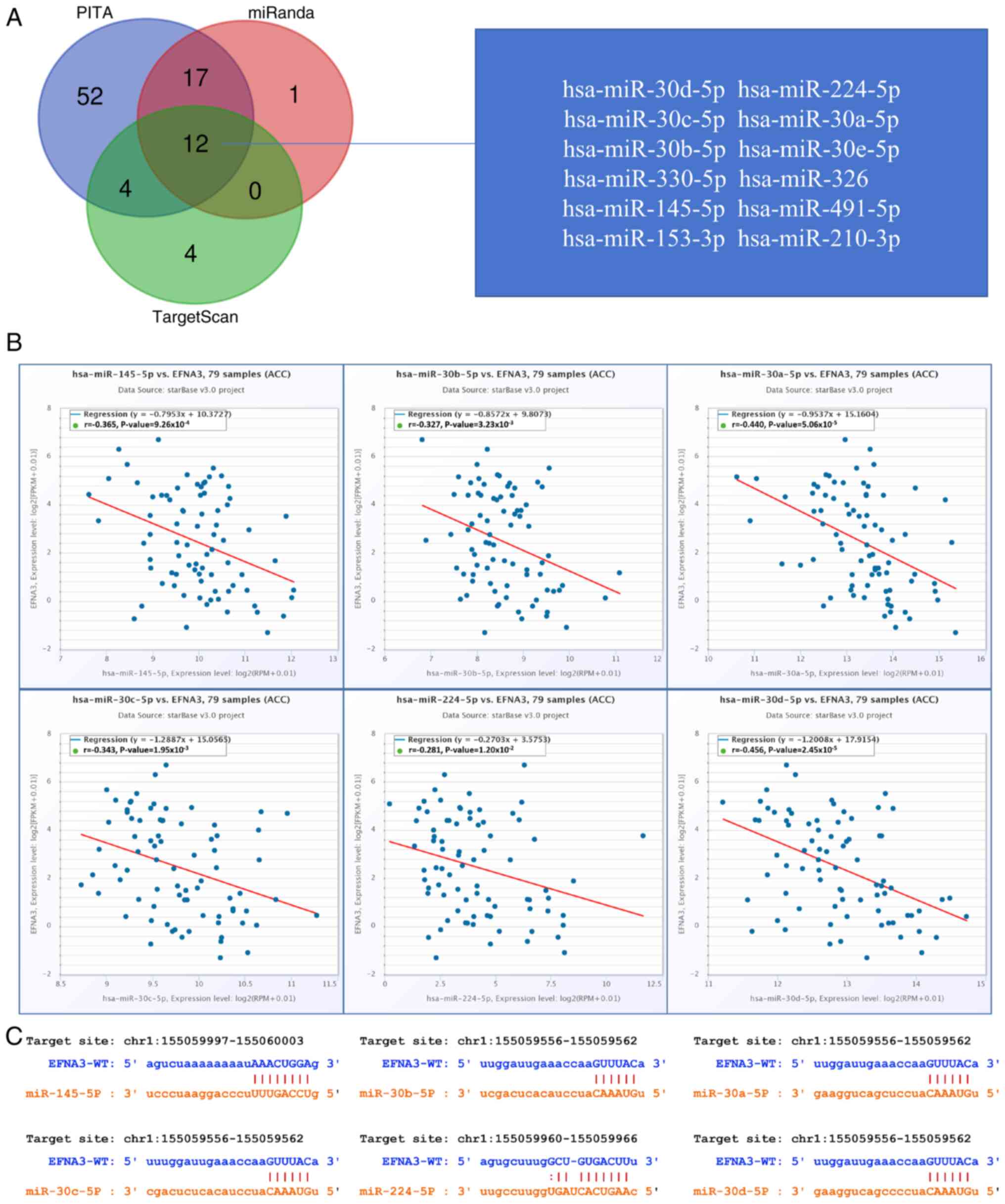

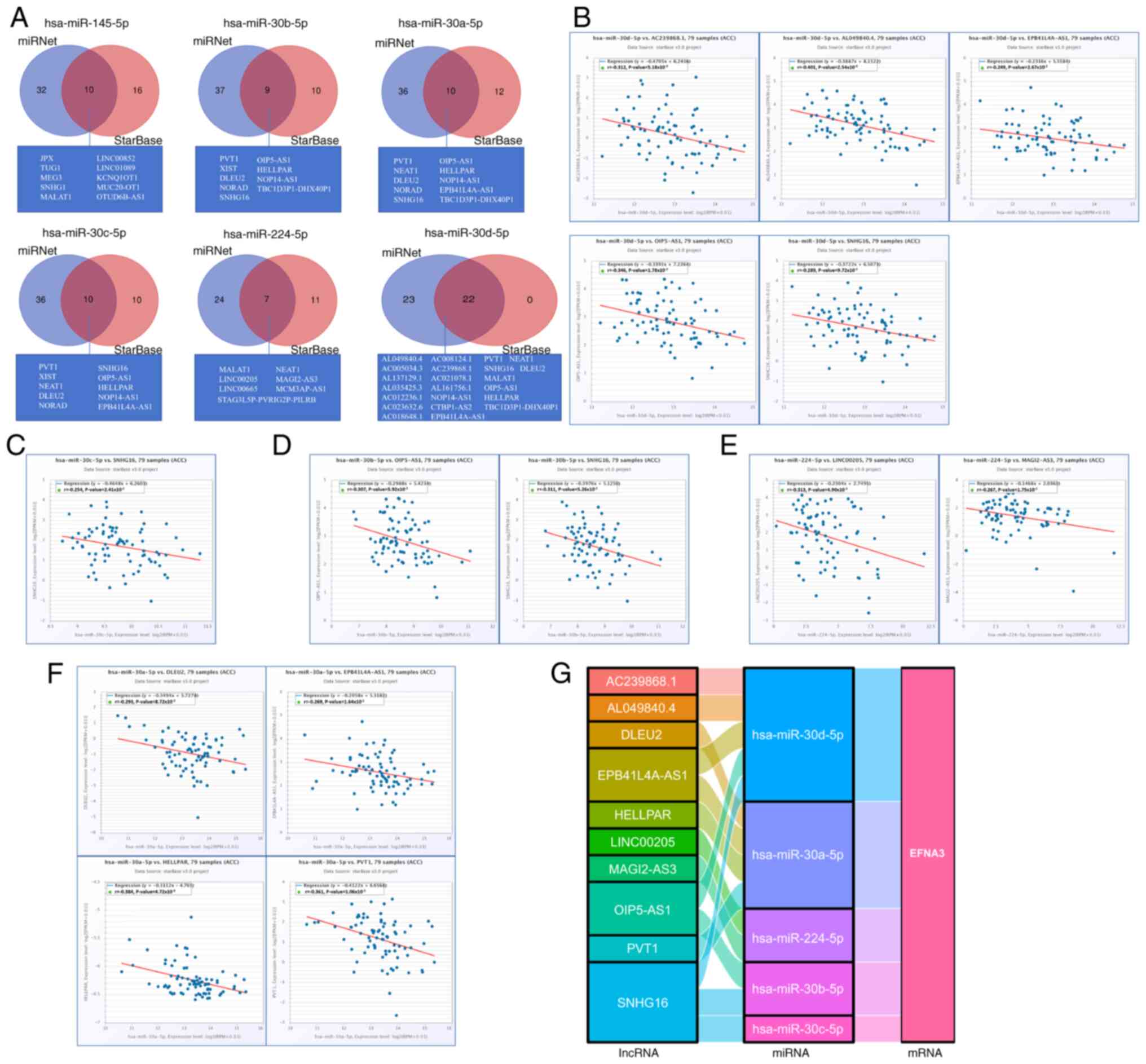

The PITA, miRanda and TargetScan databases were used

to analyze and predict 85, 30 and 20 EFNA3 target miRNAs,

respectively. A total of 12 target miRNAs were found to be in

common from the three database predictions, including

hsa-miR-30d-5p, hsa-miR-224-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, hsa-miR-30a-5p,

hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30e-5p, hsa-miR-330-5p, hsa-miR-326,

hsa-miR-145-5p, hsa-miR-491-5p, hsa-miR-153-3p and hsa-miR-210-3p

(Fig. 9A). In addition, correlation

analysis between target miRNAs and EFNA3 expression was performed

to identify candidates for further investigation of ceRNA

interactions. Correlation analysis demonstrated the expression

levels of 6 target miRNAs negatively correlated with EFNA3

expression levels, namely hsa-miR-145-5p (r=−0.365,

P=9.26×10×10−4), hsa-miR-30b-5p (r=−0.327,

P=3.23×10−3), hsa-miR-30a-3p (r=−0.44,

P=5.06×10−5), hsa-miR-30c-5p (r=−0.343,

P=1.95×10−3), hsa-miR-224-5p (r=−0.281,

P=1.20×10−2) and hsa-miR-30d-5p (r=−0.456,

P=2.45×10−5; Fig. 9B).

TargetScan was used to predict the potential binding sites of EFNA3

to the target miRNAs identified (Fig.

9C).

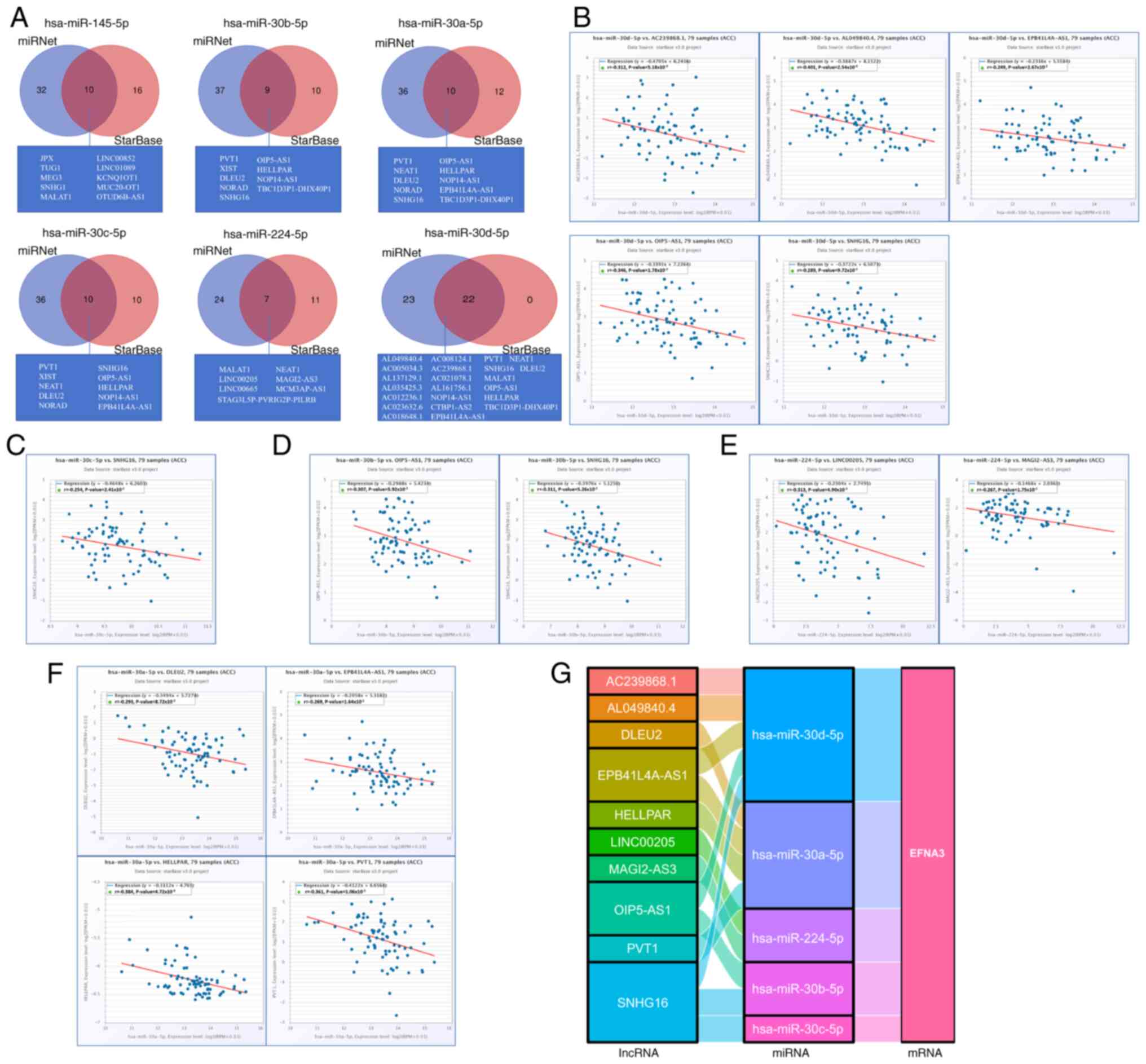

The miRNet and starBase online databases were used

to further predict lncRNAs that may bind to the six target miRNAs

(hsa-miR-145-5p, hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30a-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p,

hsa-miR-224-5p and hsa-miR-30d-5p; Fig. 10A). A negative correlation between

specific lncRNAs and miRNA was observed; the ceRNA network

hypothesis suggests that the lncRNA may act as a molecular sponge,

sequestering the miRNA and reducing its regulatory activity,

consistent with miRNA-mediated ceRNA crosstalk (29). Therefore, the starBase database was

used to analyze the correlation between target lncRNA expression

and miRNA in ACC. Correlation analysis proved that there are 5

target lncRNAs expression levels that are negatively correlated

with hsa-miR-30d-5p, namely AC239868.1, EPB41L4A-AS1, AL049840.4,

OIP5-AS1 and SNHG16 (Fig. 10B).

However, only the expression level of SNHG16 was negatively

correlated with hsa-miR-30c-5p (Fig.

10C). Furthermore, the expression of OIP5-AS1 and SNHG16 were

negatively correlated with hsa-miR-30b-5p (Fig. 10D). The expression of MAGI2-AS3 and

LINC00205 were negatively correlated with hsa-miR-224-5p (Fig. 10E). There were 4 target lncRNAs

expression levels that are negatively correlated with

hsa-miR-30a-5p, respectively EPB41L4A-AS1, PVT1, HELLPAR and DLEU2

(Fig. 10F). Based on the ceRNA

hypothesis, regarding the inverse relationship between miRNA and

lncRNA or mRNA (29), 14 pairs of

ceRNA networks (EPB41L4A-AS1-hsa- miR-30a-5p- EFNA3,

PVT1-hsa-miR-30a-5p-EFNA3, HELLPAR- hsa-miR-30a-5p-EFNA3,

DLEU2-hsa-miR-30a-5p- EFNA3, OIP5-AS1-hsa-miR-30b-5p-EFNA3, SNHG16-

hsa-miR-30b-5p-EFNA3, SNHG16-hsa-miR-30c-5p- EFNA3,

AC239868.1-hsa-miR-30d-5p-EFNA3, EPB41L4A-

AS1-hsa-miR-30d-5p-EFNA3, AL049840.4- hsa-miR-30d-5p- EFNA3,

OIP5-AS1-hsa- miR-30d-5p- EFNA3, SNHG16-hsa-miR-30d-5p-EFNA3,

MAGI2- AS3- hsa-miR-224-5p-EFNA3 and LINC00205-hsa-

miR-224-5p-EFNA3) were constructed based on the correlation

analysis results (Fig. 10G).

| Figure 10.Prediction of lncRNA and ceRNA

network construction in ACC. (A) Venn diagrams display the target

lncRNAs of hsa-miR-145-5p, hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30a-5p,

hsa-miR-30c-5p, hsa-miR-224-5p and hsa-miR-30d-5p respectively. The

starBase software was used to analyze the correlations between

miRNAs and the target lncRNA. Scatter plots demonstrate the

miRNA-mRNA associations with significant correlation as follow,

lncRNA related to (B) hsa-miR-30d-5p, (C) hsa-miR-30c-5p, (D)

hsa-miR-30b-5p, (E) hsa-miR-224-5p and (F) hsa-miR-30a-5p. (G) The

Sankey diagram displays the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA EFNA3 regulatory

network in line with the competitive endogenous RNA hypothesis.

EFNA3, ephrin-A3; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; miRNA, microRNA;

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA. |

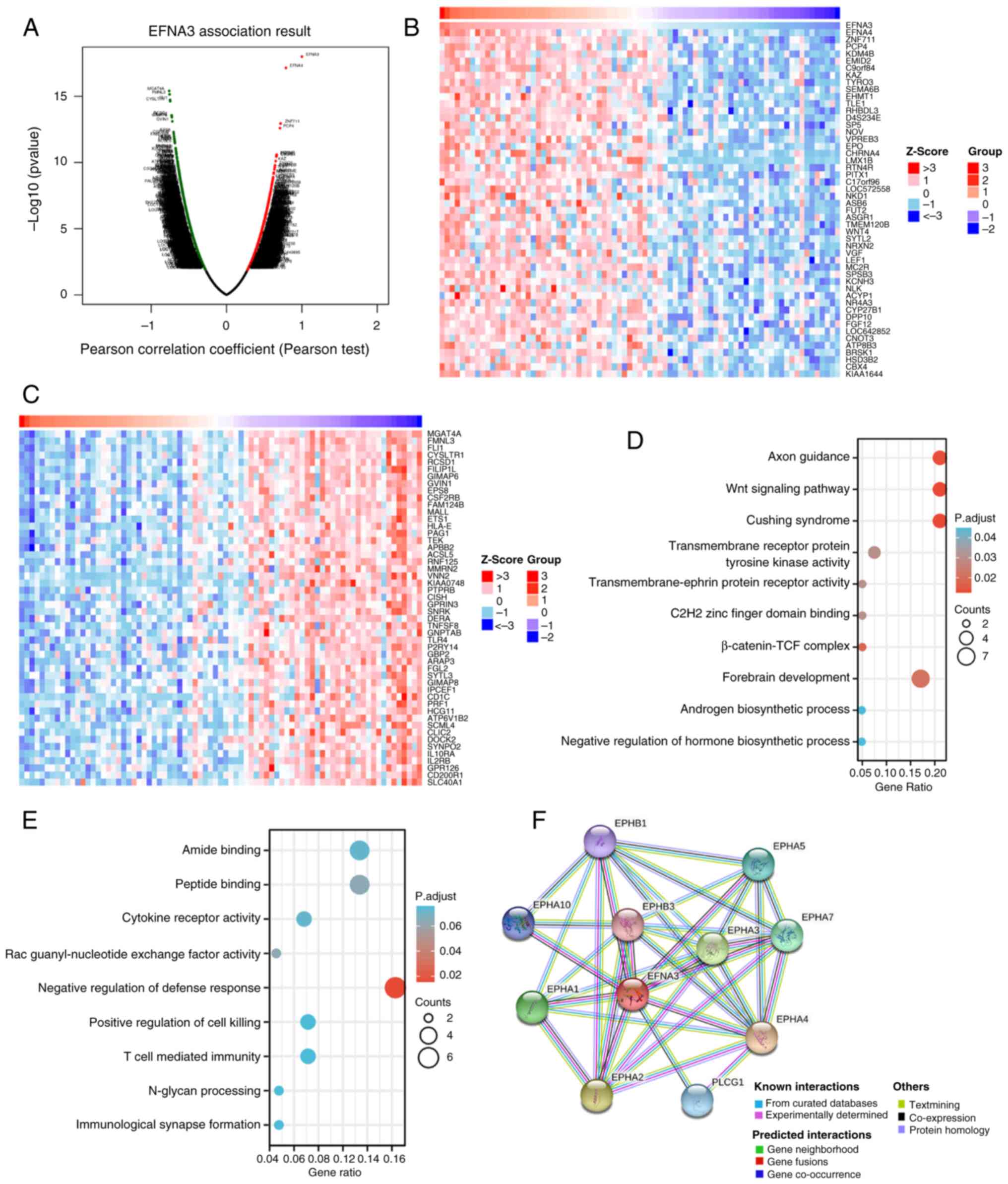

Analysis of genes and functions

co-expressed with EFNA3 in ACC

The LinkedOmics database was used to analyze EFNA3

co-expression in ACC; under the condition of FDR<0.05, 2,000

genes were significantly positively correlated with EFNA3

expression levels (Fig. 11A),

while 2,967 genes were significantly negatively correlated with

EFNA3 expression levels. The genes that were positively and

negatively correlated with EFNA3 expression levels in ACC are

provided in Tables SXIII. The top

50 genes most significantly positively (Fig. 11B) and negatively (Fig. 11C) correlated with EFNA3 expression

levels are displayed in the heat map. Table SXIV, Table SXV summarizes the GO and KEGG

enrichment analyses of genes positively and negatively correlated

with EFNA3 expression. As shown in the functional enrichment

analysis, genes positively correlated with EFNA3 expression were

significantly enriched in pathways and biological terms including

‘Cushing syndrome’, ‘Wnt signaling pathway’, ‘C2H2 zinc finger

domain binding’, ‘forebrain development’, and the ‘β-catenin-TCF

complex’ (Fig. 11D). Genes

negatively correlated with EFNA3 expression were significantly

associated with immune-related processes and molecular functions,

such as ‘T-cell-mediated immunity’, ‘N-glycan processing’,

‘immunological synapse formation’ and ‘cytokine receptor activity’

(Fig. 11E).

The STRING database was used to investigate the PPI

network of EFNA3; EFNA3 was associated with ephrin type-A receptor

4 (EPHA4), ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EPHA2), ephrin type-A receptor

3 (EPHA3), ephrin type-A receptor 7 (EPHA7), ephrin type-A receptor

5 (EPHA5), 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

phosphodiesterase γ-1, ephrin type-A receptor, ephrin type-B

receptor 1 and ephrin type-B receptor 3 (0.999, 0.948, 0.936,

0.929, 0.924, 0.914, 0.904, 0.895, 0.88 and 0.869 respectively;

Fig. 11F). The confidence scores

represent the calculated probability that these associated proteins

have a functional interaction with EFNA3. EPHA4, EPHA2 and EPHA3

had the highest correlation with EFNA3, suggesting that these genes

may serve a promoting role in certain types of tumors. These

results suggested that EFNA3 may be closely related to the

occurrence and development of ACC.

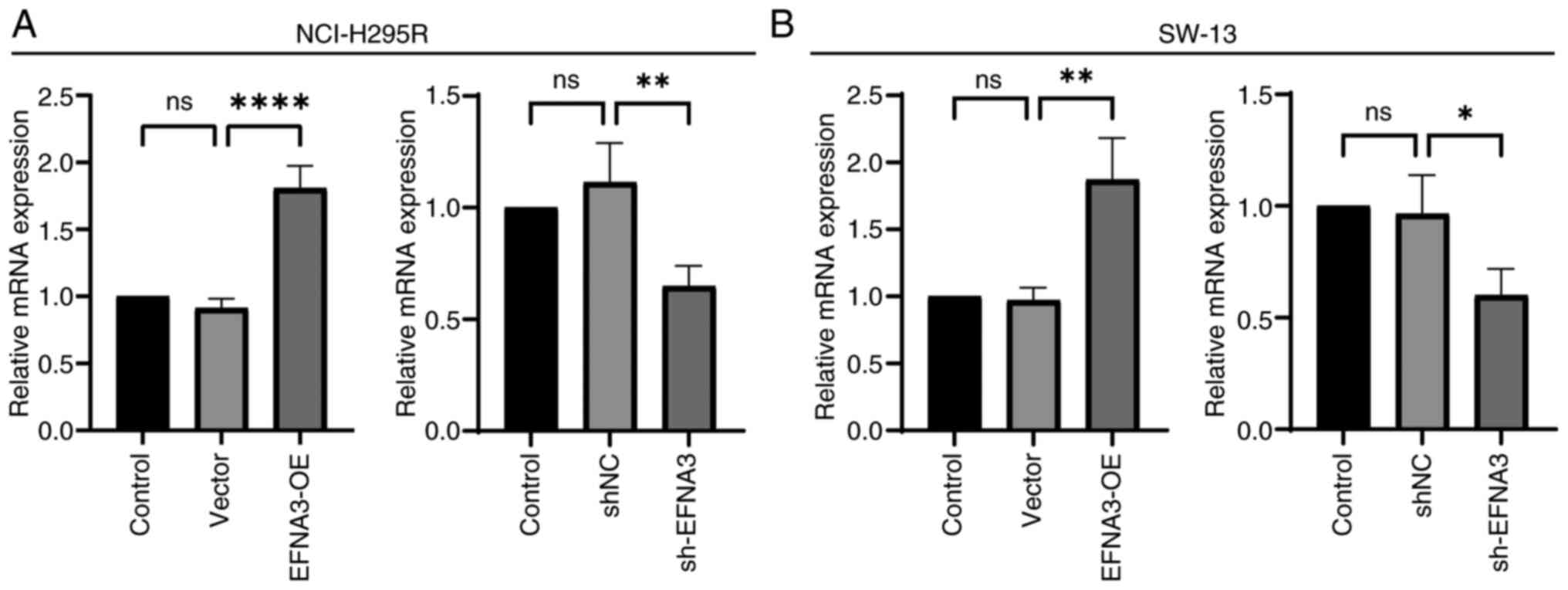

Validation of ACC cell transfection

efficiency

ACC cell transfection efficiency was demonstrated

using RT-qPCR. In NCI-H295R and SW-13 cell lines, the mRNA

expression level in EFNA3-OE group was significantly increased

compared with that of the vector group, and the EFNA3 mRNA

expression in sh-EFNA3 group was significantly decreased compared

with that of the shNC group (P<0.05; Fig. 12).

EFNA3 enhances the viability and

invasiveness of ACC cells in vitro

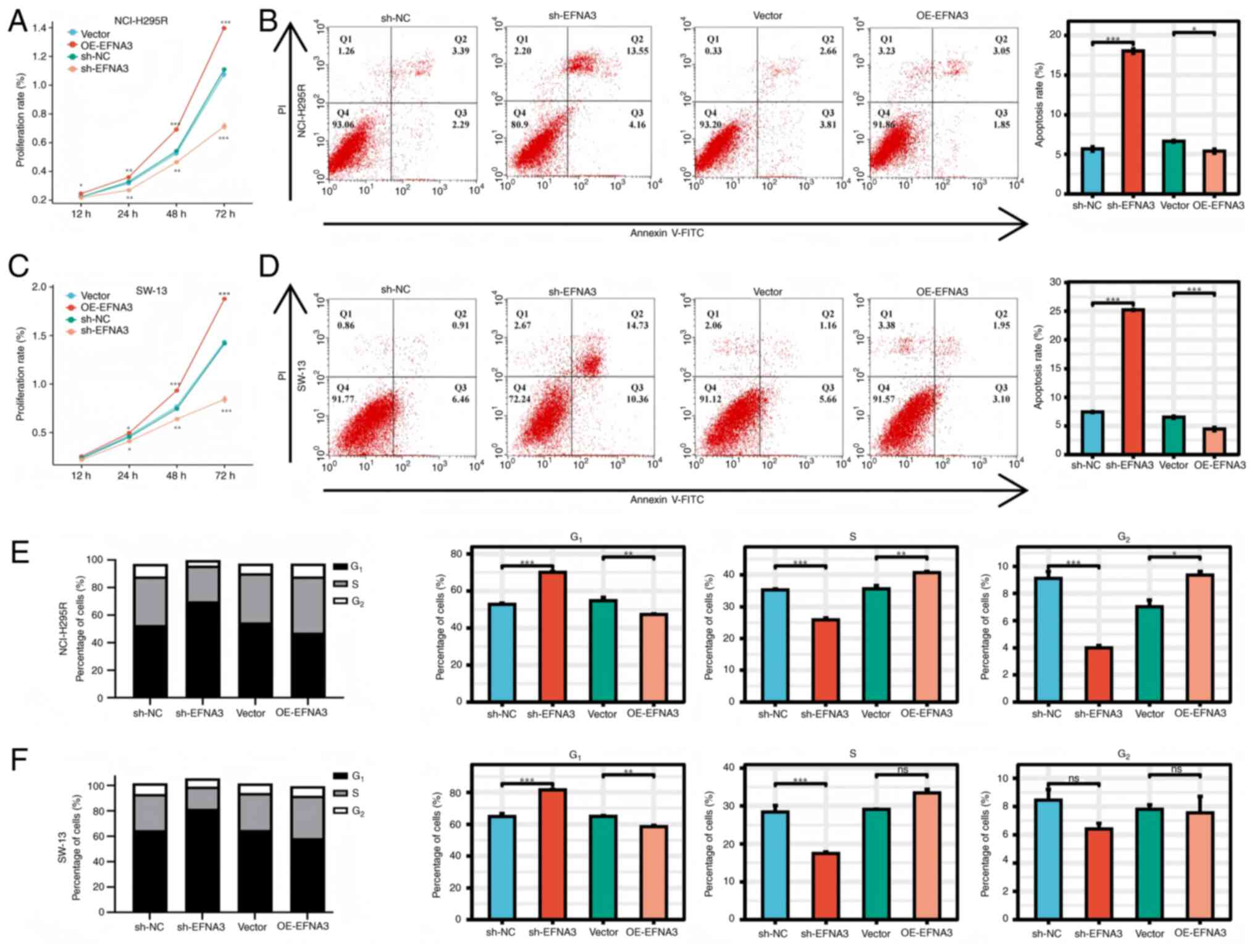

CCK-8 assays demonstrated that EFNA3 overexpression

significantly promoted cell viability compared with that of the

control group, whereas EFNA3 knockdown had the opposite effect.

Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that EFNA3 knockdown induced

apoptosis and G1/S phase cell cycle arrest. Conversely,

EFNA3 overexpression significantly reduced apoptosis and

facilitated S-phase progression (Fig.

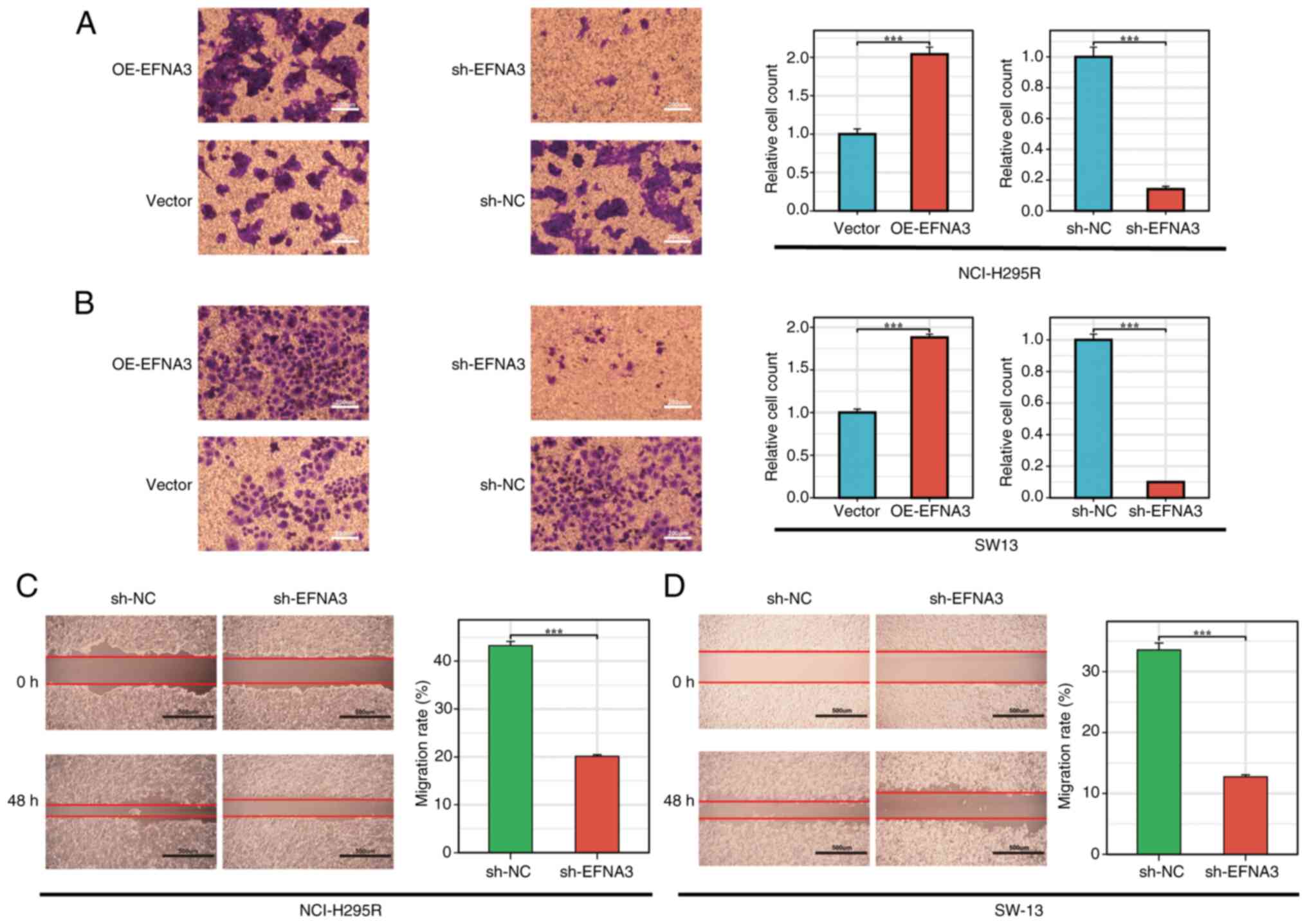

13A-F). In the Transwell and wound healing assays, EFNA3

overexpression significantly enhanced cell migration capabilities,

respectively. By contrast, EFNA3 knockdown significantly impaired

these abilities (Fig. 14A-D).

Discussion

EFNA3, a glycolysis-associated gene, has been

implicated in the progression of several malignancies, including

BC, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), oral squamous cell carcinoma,

pancreatic adenocarcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD),

pheochromocytoma and stomach adenocarcinoma, and has been proposed

as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in these contexts

(14,30–33). A

recent multi-omics study demonstrated epigenetic regulation of

EFNA3 in metastatic pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas,

identifying a differentially methylated probe (cg12741345) located

within the gene body of EFNA3 (34). The present study also found the

cg12741345 probe among the 28 CpG sites identified in ACC, which

suggested potential epigenetic dysregulation of EFNA3 in ACC

pathogenesis.

To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive

pan-cancer analysis of EFNA3 incorporating multi-dimensional data

has been reported. The present results demonstrated that EFNA3 is

significantly upregulated in tumor tissues when compared with that

of adjacent normal tissues across multiple cancer types, including

BLCA, CHOL and colon adenocarcinoma. However, in GBM, KICH, LAML

and SKCM, EFNA3 expression levels were significantly reduced. These

cancer types have not been well explored regarding the biological

role of EFNA3, and the clinical significance of this downregulation

remains currently unclear.

EFNA3 is involved in multiple cellular functions,

including tumor malignancy, angiogenesis, energy metabolism and

intratumoral hypoxia. In HCC, EFNA3 upregulation correlates with

more aggressive tumor behavior, promotion of self-renewal,

proliferation, migration and tumor stemness (35). Mechanistically, under hypoxic

conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) increases EFNA3

expression in HCC by increasing copy number (12). Deng et al (14) demonstrated that knocking down EFNA3

significantly inhibits the proliferation and glycolytic capacity of

LUAD cells. Yiminniyaze et al (36) further demonstrated that EFNA3

induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by enhancing ERK and AKT

phosphorylation levels, while upregulating MMP2 and MMP9

expression. In choroidal melanoma, EFNA3 promotes cell

proliferation and migration by activating the STAT3/AKT signaling

pathway (37). In prostate cancer,

EFNA3 knockout suppresses disease progression by reducing

Ras/Braf/MEK/Erk1/2 phosphorylation levels (38). In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

cells, EFNA3 enhances tumor angiogenesis and cell permeability

through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (39). This divergent expression pattern may

reflect cancer-type-specific regulatory mechanisms or TME

influences. Further experimental studies are warranted to elucidate

the role of EFNA3 in these malignancies. In the future, in

vivo models can be used to elucidate whether reduced EFNA3

expression confers tumor-suppressive effects or reflects

compensatory biological processes, in order to expand the current

understanding of EFNA3 as a context-dependent modulator in tumor

biology.

Genetic alterations such as single nucleotide and

CNAs are key drivers of oncogenesis and tumor progression (40). In the present pan-cancer analysis,

EFNA3 exhibited a notably high mutation frequency, >40% in BC,

suggesting a potential tumor-promoting role in this context. Within

the ACC cohort, the most prevalent genomic events associated with

EFNA3 were elevated mRNA expression and gene amplification, both

indicative of CNA-driven dysregulation. Survival analyses across

pan-cancer datasets demonstrated that EFNA3 mutations were

associated with poorer overall survival, supporting its relevance

as a clinically significant genomic alteration. Specifically,

patients harboring EFNA3 mutations in ACC showed significantly

reduced OS and DFS compared with those with wild-type EFNA3,

underscoring its potential role as a negative prognostic

marker.

To further elucidate the genetic landscape

associated with EFNA3 expression, mutation profiles between high-

and low-EFNA3 expression groups were compared. CTNNB1 emerged as a

differentially mutated gene, suggesting possible co-regulatory or

downstream interactions. By contrast, EFNA3 expression did not

significantly differ between groups stratified by TP53 or PRKAR1A

mutation status, two well-established drivers in ACC, which

suggested that EFNA3 regulation may operate through mechanisms

independent of TP53/PRKAR1A signaling.

Previous studies have shown that CTNNB1 mutations in

ACC are primarily missense mutations localized to exon 3, which

impair β-catenin degradation and promote Wnt pathway activation

(41,42). Future research should elucidate

whether specific CTNNB1 mutation types, such as exon 3 hotspots

versus null alleles, modulate EFNA3 expression or function. A

mechanistic dissection of EFNA3-CTNNB1 cross-talk may yield novel

insights into the oncogenic circuitry of ACC.

Unlike genomic mutations, epigenetic modifications,

such as DNA methylation and RNA methylation, alter gene expression

without changing the DNA sequence itself (43). These modifications are increasingly

recognized as pivotal regulators of oncogenesis and tumor behavior

(44). The present study identified

28 CpG methylation sites associated with EFNA3 in ACC; a CpG island

methylator phenotype (CIMP) has been previously reported in ACC,

with the CIMP-high subgroup associated with poorer clinical

outcomes, compared with that of the CIMP-low subgroup (45,46).

Aberrant DNA methylation in promoter or gene body regions can

silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, thereby

influencing tumor aggressiveness and therapeutic response (47). Although no methylation-targeted

therapy has been clinically approved for ACC, DNA methylation

inhibitors such as 5-azacytidine and decitabine have demonstrated

efficacy in other types of cancer, such as BC and ACC, and are

under investigation in preclinical ACC models (48–53).

Decitabine demonstrates anti-tumor effects in ACC cells at

clinically relevant concentrations by reactivating silenced genes

in the 11q13 region, suggesting a role for epigenetic mechanisms in

adrenocortical carcinogenesis and indicating its potential as an

adjuvant treatment for advanced cases (49). The present data supported the

hypothesis that EFNA3 methylation patterns may contribute to ACC

pathogenesis and could be leveraged as a predictive biomarker or

therapeutic target.

Furthermore, significant positive correlations

between EFNA3 expression and mRNA modification regulators across

pan-cancer datasets were demonstrated. In ACC specifically, several

m6A modulators demonstrated expression alterations with prognostic

implications. For instance, HNRNPC, a known splicing regulator, was

downregulated in ACC and associated with a worse prognosis

(54). Conversely, ALKBH5 and

YTHDF2 were upregulated and linked to tumor progression (54–58).

METTL3, a methyltransferase, was downregulated and associated with

a favorable prognosis. These findings suggested that EFNA3 may be

integrated into broader epigenetic regulatory networks, including

m6A RNA methylation pathways, that modulate tumor biology in ACC.

Collectively, the present results suggested a complex regulatory

landscape in which EFNA3 is subject to both DNA- and RNA-level

epigenetic control, offering novel insights into its diagnostic and

therapeutic relevance in ACC. Future studies may explore

combinations with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (such as

decitabine) or m6A modulators to reverse EFNA3-driven oncogenicity,

leveraging epigenetic vulnerabilities common in types of endocrine

cancer.

Immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment

paradigm for various types of cancer, offering durable responses in

a subset of patients, such as patients with relapsed ovarian cancer

and relapsed gastric cancer (59).

However, a significant proportion of individuals fail to achieve

sustained benefits, which is often attributed to the complexity and

heterogeneity of the TME (60,61).

Immunotherapy is primarily used in patients with advanced ACC after

the failure of traditional chemotherapy (62). Among these treatments, pembrolizumab

is the most studied and recommended in guidelines, although its

monotherapy objective response rate remains limited (63–65).

The present study identified a significant correlation between

EFNA3 expression levels and immune cell infiltration across

multiple cancer types, including ACC. This suggested that EFNA3 may

serve a role in modulating the immune landscape, potentially

impacting tumor immune evasion and responsiveness to

immunotherapeutic agents. In ACC specifically, where immune-based

treatment options currently remain limited, EFNA3 may serve as a

potential immunological biomarker or therapeutic target. Given its

association with immune infiltration, EFNA3 might be involved in

shaping the immunosuppressive or immunoactive features of the TME.

Further studies are warranted to delineate its mechanistic role in

regulating immune cell recruitment, antigen presentation or

checkpoint molecule expression. The correlation between EFNA3 and

TME features demonstrated in the present study provide a rationale

for evaluating EFNA3 not only as a diagnostic or prognostic marker

but also as a modulator of tumor-immune interactions, opening

avenues for combination strategies involving EFNA3-targeted agents

and immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-programmed cell

death protein 1 and programmed cell death ligand 1) in ACC.

The ceRNA hypothesis proposes that lncRNAs can

regulate gene expression by sequestering miRNAs, thereby preventing

them from binding to target mRNAs (66). Increasing evidence has implicated

the EFNA3-centered ceRNA network in various tumor types. For

example, miR-210-3p has been shown to target EFNA3, thereby

modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway and influencing tumor progression

in oral squamous cell carcinoma (67). Similarly, miR-210-mediated

suppression of EFNA3 has been reported to affect cell proliferation

and invasiveness in peripheral nerve sheath tumors (68). Under hypoxic conditions, EFNA3 can

also be regulated through HIF-induced lncRNA activation, promoting

metastatic spread in BC (69).

The present study constructed a lncRNA-miRNA-EFNA3

regulatory axis in ACC, highlighting novel non-coding RNA molecules

such as OIP5-AS1 and hsa-miR-30d-5p. Previous studies have shown

that OIP5-AS1 can act as a ceRNA to modulate oncogenic signaling in

endocrine tumors, while miR-486-3p is downregulated in

adrenocortical neoplasms and may serve as a tumor suppressor

(70,71). The ceRNA network involving EFNA3

identified in the present analysis demonstrated a potential

mechanism of post-transcriptional regulation that could contribute

to tumor progression, immune modulation and drug resistance in ACC.

Furthermore, targeting the lncRNA-miRNA-EFNA3 regulatory axis may

have therapeutic potential. For example, salazosulfapyridine has

been proposed to exert anticancer effects in ACC by interacting

with the OIP5-AS1-miR-92a-3p-SLC7A11 pathway (72). The present findings underscored the

potential of EFNA3-centered ceRNA regulatory networks as diagnostic

tools and therapeutic targets in ACC, warranting further functional

validation.

Drug repurposing offers a cost-effective and

time-efficient strategy to identify new therapeutic options for

rare and refractory malignancies such as ACC. In the present study,

drug sensitivity correlation analysis was performed based on EFNA3

expression was performed, identifying 24 EFNA3-associated compounds

in the CTRP database and 14 in the GDSC database. Notably, EFNA3

expression was significantly correlated with sensitivity to HMG-CoA

reductase inhibitors (statins), which have gained interest for

their potential antitumor effects (73,74).

Statins, primarily used to treat hypercholesterolemia, have

demonstrated tumor-suppressive effects in multiple cancer types,

including HCC, breast, lung and colorectal cancer (75–80).

Mechanistically, statins exert antitumor effects through inhibition

of the mevalonate pathway, leading to suppression of AKT/NF-κB

signaling, induction of apoptosis via caspase cascade activation

and impairment of metastatic potential through modulation of MAPK

and mTOR pathways (81–88). Simvastatin, for example, has been

shown to activate AMPK, upregulate p21 and induce apoptosis in HCC

cells (86). HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors reduce isoprenoid synthesis by inhibiting the mevalonate

pathway, thereby affecting the tumor procession (89).

Despite this promising pharmacological profile,

limited studies have examined the application of statins in

endocrine malignancies, particularly in ACC. Given the dependence

of ACC cells on cholesterol biosynthesis and isoprenoid metabolism

(90), the mevalonate pathway

represents a potential target. Furthermore, given the key role of

EFNA3 in glycolysis, combining EFNA3 inhibition with glycolytic

inhibitors or statins represents a metabolic ‘double-hit’ strategy

against the Warburg-dependency of ACC. The present results

highlight EFNA3 as a potential biomarker for predicting statin

sensitivity in ACC. The therapeutic implications of this finding

warrant further validation through in vitro mechanistic

assays and in vivo efficacy studies. Furthermore,

integrating statins with EFNA3-targeted strategies may provide a

synergistic approach to disrupt tumor metabolism and reduce ACC

aggressiveness.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade serves a pivotal

role in ACC by regulating tumor cell proliferation, migration and

metabolic reprogramming. Dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway,

commonly through activating mutations in the CTNNB1 gene, is a

hallmark of ACC pathogenesis (91,92).

In the present transcriptome-based co-expression analysis, EFNA3

was closely associated with genes involved in Wnt signaling,

suggesting a potential regulatory interaction. Specifically, EFNA3

expression was significantly increased in CTNNB1-mutated samples,

demonstrating an association between EFNA3 activity and

Wnt/β-catenin pathway dysregulation. Previous research has

demonstrated that β-catenin and Transcription Factor 4 modulate the

expression of EphB receptors and their ligands, including

ephrin-B1, thereby orchestrating spatial organization along

epithelial axes such as the crypt-villus axis in colorectal cancer

(93). The present findings

suggested a similar interaction may exist between EFNA3 and

β-catenin in ACC, which potentially contributes to malignant

transformation. Furthermore, EFNA3 is a glycolysis-related gene,

and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a known driver of metabolic

reprogramming in cancer cells (94). This pathway enhances aerobic

glycolysis by upregulating glycolytic enzymes, promoting a

tumor-favorable microenvironment characterized by increased lactate

production and glucose uptake (95–101).

In colon and breast cancer, activation of Wnt signaling induces

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 expression and modulates adipogenic

enzymes, respectively, reinforcing glycolytic flux and tumor

proliferation (96–98).

The present in vitro experiments

demonstrated that EFNA3 promotes invasive behavior in ACC cells.

These data suggested that EFNA3 may act as a downstream effector or

modulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling to coordinate both metabolic

and invasive phenotypes in ACC. Future mechanistic studies are

warranted to dissect the precise molecular interactions between

EFNA3, β-catenin and glycolysis-related signaling pathways in ACC

progression. These findings present EFNA3 not only as a key

mediator of Wnt-driven ACC pathogenesis but also as a potential

node for combinatorial therapeutic intervention. Given the

established challenges in targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling

directly in endocrine tumors, primarily the disruption of normal

somatic stem cell function critical for cellular repair and tissue

homeostasis (102), EFNA3

inhibition offers a tractable approach to disrupt downstream

oncogenic outputs (such as metabolic reprogramming and invasion)

while potentially synergizing with Wnt pathway modulators or

endocrine-disrupting agents.

Despite the comprehensive nature of the present

study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the

bioinformatics analyses were primarily based on the relatively

small TCGA-ACC cohort. Future studies incorporating larger,

multi-center datasets are needed to strengthen the robustness and

generalizability of these findings. Although the integrative

bioinformatics and in vitro findings suggested that EFNA3 is

associated with enhanced sensitivity to HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors, clinical evidence remains lacking. Large-scale,

randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the therapeutic

efficacy of these agents and safety in patients with ACC. Second,

the ceRNA regulatory network involving EFNA3 was constructed

through computational predictions and partially supported by

molecular data. however, extensive experimental validation,

particularly through gain and loss-of-function; assays in

vivo, is required to confirm biological relevance and establish

causal relationships between EFNA3 and these pathways. Third,

although significant epigenetic alterations associated with EFNA3

expression in ACC were observed, the potential of DNA methylation

inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy remains unexplored in clinical

settings. Additional preclinical studies are necessary to determine

whether demethylating agents can reverse EFNA3-mediated oncogenic

effects. While the present in vitro experiments demonstrated

EFNA3 enhances ACC cell invasiveness, the absence of in vivo

validation remains a key constraint. The precise molecular

mechanism governing the interplay between EFNA3, Wnt/β-catenin

signaling and metabolic reprogramming requires further elucidation

through mechanistic studies in animal models complemented by

patient-derived organoids.

Future research should also explore the feasibility

of targeting EFNA3 as a multi-modal biomarker for ACC prognosis,

immunomodulation and drug responsiveness. Future research should

focus on verifying the synergistic potential of EFNA3-targeted

therapy with four major categories of drugs: Immune checkpoint

inhibitors (to reverse immunosuppression), epigenetic modulators

(to regulate the methylation/m6A network), metabolic disruptors (to

block glycolysis and mevalonate pathways) and endocrine-specific

drugs (adrenal diuretics and steroid synthesis inhibitors). This is

essential to overcome ACC drug resistance, achieve synergistic

effects, and are key to translating the present findings into

clinically actionable strategies.

The present study identified EFNA3 as a potential

oncogenic driver and prognostic biomarker in adrenocortical

carcinoma. Through integrative bioinformatics analyses and in

vitro validation, it was demonstrated that EFNA3 may modulate

tumor invasiveness, potentially through its interaction with the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and glycolytic reprogramming. EFNA3

expression was also associated with immune cell infiltration,

epigenetic alterations and drug sensitivity, particularly to

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, highlighting its potential as a

multifaceted therapeutic target. Furthermore, construction of a

ceRNA regulatory network provided novel insights into the

post-transcriptional control of EFNA3 in ACC. These findings

collectively support the translational relevance of EFNA3 and

warrant further mechanistic and clinical investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Research

in Shanxi Province (grant no. 202203021211072), Postgraduate

Practice and Innovation Project (grant no. 2024SJ173) and the Task

Book of High-Level Research Results Continuation Funding Project

from Shanxi Bethune Hospital (Shanxi Medical Science Academy; grant

no. 2024GSPYJ04).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YT, XL and JS designed and implemented the study.

YT and YZ performed acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data

for the work. YT, XL, YZ and JS contributed to drafting the work or

revising it critically for important intellectual content. JS

supervised the project, acquired funding and provided final

approval of the published version. YT and XL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors agreed to be

accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions

related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Else T, Kim AC, Sabolch A, Raymond VM,

Kandathil A, Caoili EM, Jolly S, Miller BS, Giordano TJ and Hammer

GD: Adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr Rev. 35:282–326. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sinclair TJ, Gillis A, Alobuia WM, Wild H

and Kebebew E: Surgery for adrenocortical carcinoma: When and how?

Best Pract Res Clin En. 34:1014082020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Del Rivero J, Else T, Hallanger-Johnson J,

Kiseljak-Vassiliades K, Raj N, Reidy-Lagunes D, Srinivas S, Gilbert

J, Vaidya A, Aboujaoude E, et al: A review of mitotane in the

management of adrenocortical cancer. Oncologist. 29:747–760. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Fassnacht M, Dekkers O, Else T, Baudin E,

Berruti A, de Krijger R, Haak H, Mihai R, Assie G and Terzolo M:

European society of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines on

the management of adrenocortical carcinoma in adults, in

collaboration with the European network for the study of adrenal

tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 179:G1–G46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Huang L, Gu Y, Cang W, Sun P and

Xiang Y: Lactate-Lactylation hands between metabolic reprogramming

and immunosuppression. Int J Mol Sci. 23:119432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ganapathy-Kanniappan S and Geschwind JH:

Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and

prospects. Mol Cancer. 12:1522013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Boedtkjer E and Pedersen SF: The acidic

tumor microenvironment as a driver of cancer. Annu Rev Physiol.

82:103–126. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu S, Shen G, Zhou X, Sun L, Yu L, Cao Y,

Shu X and Ran Y: Hsp90 promotes gastric cancer cell metastasis and

stemness by regulating the regional distribution of

glycolysis-related metabolic enzymes in the cytoplasm. Adv Sci.

11:e23101092024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Nievergall E, Lackmann M and Janes PW:

Eph-dependent cell-cell adhesion and segregation in development and

cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 69:1813–1842. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Himanen J, Saha N and Nikolov DB:

Cell-cell signaling via Eph receptors and ephrins. Curr Opin Cell

Biol. 19:534–542. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kou CJ and Kandpal RP: Differential

expression patterns of Eph receptors and ephrin ligands in human

cancers. Biomed Res Int. 2018:73901042018.

|

|

12

|

Stewen J, Kruse K, Godoi-Filip AT, Zenia

Jeong H, Adams S, Berkenfeld F, Stehling M, Red-Horse K, Adams RH

and Pitulescu ME: Eph-ephrin signaling couples endothelial cell

sorting and arterial specification. Nat Commun. 15:25392024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pasquale EB: Eph receptors and ephrins in

cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 24:5–27. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Deng M, Tong R, Zhang Z, Wang T, Liang C,

Zhou X and Hou G: EFNA3 as a predictor of clinical prognosis and

immune checkpoint therapy efficacy in patients with lung

adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 21:5352021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hao Y and Li G: Role of EFNA1 in

tumorigenesis and prospects for cancer therapy. Biomed

Pharmacother. 130:1105672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yamashita T, Ohneda K, Nagano M, Miyoshi

C, Kaneko N, Miwa Y, Yamamoto M, Ohneda O and Fujii-Kuriyama Y:

Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-2alpha in endothelial cells

regulates tumor neovascularization through activation of ephrin A1.

J Biol Chem. 283:18926–18936. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nakamura R, Kataoka H, Sato N, Kanamori M,

Ihara M, Igarashi H, Ravshanov S, Wang Y, Li Z, Shimamura T, et al:

EPHA2/EFNA1 expression in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci.

96:42–47. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cui Y, Chang Y, Ma X, Sun M, Huang Y, Yang

F, Li S, Zhuo W, Liu W, Yang B, et al: Ephrin A1 stimulates CCL2

secretion to facilitate pre-metastatic niche formation and promote

gastric cancer liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 85:263–276. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wilson K, Shiuan E and Brantley-Sieders

DM: Oncogenic functions and therapeutic targeting of EphA2 in

cancer. Oncogene. 40:2483–2495. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mao L, Yuan W, Cai K, Lai C, Huang C, Xu

Y, Zhong S, Yang C, Wang R, Zeng P, et al: EphA2-YES1-ANXA2 pathway

promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene.

40:3610–3623. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Y, Peng Q and Wang L: EphA2 as a phase

separation protein associated with ferroptosis and immune cell

infiltration in colorectal cancer. Aging (Albany NY).

15:12952–12965. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pei J, Zhang C, Yusupu M, Zhang C and Dai

DQ: Screening and validation of the hypoxia-related signature of

evaluating tumor immune microenvironment and predicting prognosis

in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 12:7055112021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Xie R, Yuan M and Jiang Y: The pan-cancer

crosstalk between the EFNA family and tumor microenvironment for

prognosis and immunotherapy of gastric cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:7909472022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Bhatia S, Oweida A, Lennon S, Darragh LB,

Milner D, Phan AV, Mueller AC, Van Court B, Raben D, Serkova NJ, et

al: Inhibition of EphB4-Ephrin-B2 signaling reprograms the tumor

immune microenvironment in head and neck cancers. Cancer Res.

79:2722–2735. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Janes PW, Vail ME, Ernst M and Scott AM:

Eph receptors in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Res. 81:801–805. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ma W, Zhu M, Wang B, Gong Z, Du X, Yang T,

Shi X, Dai B, Zhan Y, Zhang D, et al: Vandetanib drives growth

arrest and promotes sensitivity to imatinib in chronic myeloid

leukemia by targeting ephrin type-B receptor 4. Mol Oncol.

16:2747–2765. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM

and Alizadeh AA: Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with

CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol. 1711:243–259. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L and

Pandolfi PP: A ceRNA hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA

language? Cell. 146:353–358. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kuang L, Pang Y and Fang Q: TMEM101

expression and its impact on immune cell infiltration and prognosis

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 14:318472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu Q, Li P, Tao X, Lin N, Mao B and Xie X:

A novel super-enhancer-related risk model for predicting prognosis

and guiding personalized treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC

Cancer. 24:10872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin P and Yang H: EFNA3 is a prognostic

biomarker for the overall survival of patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 77:879–880. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang L, Song Y, Wang H, Liu K, Shao Z and

Shang Z: MiR-210-3p-EphrinA3-PI3K/AKT axis regulates the

progression of oral cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 24:4011–4022. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chatzikyriakou P, Brempou D, Quinn M,

Fishbein L, Noberini R, Anastopoulos IN, Tufton N, Lim ES, Obholzer

R, Hubbard JG, et al: A comprehensive characterisation of

phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma tumours through histone protein

profiling, DNA methylation and transcriptomic analysis genome wide.

Clin Epigenetics. 15:1962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Husain A, Chiu Y, Sze KM, Ho DW, Tsui Y,

Suarez EMS, Zhang VX, Chan L, Lee E, Lee JM, et al: Ephrin-A3/EphA2

axis regulates cellular metabolic plasticity to enhance cancer

stemness in hypoxic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol.

77:383–396. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Yiminniyaze R, Zhang X, Zhu N, Wang J, Li

C, Wumaier G, Zhou D, Li J, Xia J, Zhang Y, et al: EphrinA3 is a

key regulator of malignant behaviors and a potential prognostic

factor in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 12:1630–1642. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li Y, Peng Q and Wang L: EphA2 as a phase

separation protein associated with ferroptosis and immune cell

infiltration in colorectal cancer. Aging (Albany NY).

15:12952–12965. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pei J, Zhang C, Yusupu M, Zhang C and Dai

D: Screening and validation of the hypoxia-related signature of

evaluating tumor immune microenvironment and predicting prognosis

in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 12:7055112021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Deng M, Tong R, Zhang Z, Wang T, Liang C,

Zhou X and Hou G: EFNA3 as a predictor of clinical prognosis and

immune checkpoint therapy efficacy in patients with lung

adenocarcinoma. Cancer cell Int. 21:5352021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kiri S and Ryba T: Cancer, metastasis, and

the epigenome. Mol Cancer. 23:1542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zheng S, Cherniack AD, Dewal N, Moffitt

RA, Danilova L, Murray BA, Lerario AM, Else T, Knijnenburg TA,

Ciriello G, et al: Comprehensive pan-genomic characterization of

adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 29:723–736. 2016.

|

|

42

|

Sun-Zhang A, Juhlin CC, Carling T, Scholl

U, Schott M, Larsson C and Bajalica-Lagercrantz S: Comprehensive

genomic analysis of adrenocortical carcinoma reveals genetic

profiles associated with patient survival. ESMO Open. 9:1036172024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sun L, Zhang H and Gao P: Metabolic

reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer.

Protein Cell. 13:877–919. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Orsolic I, Carrier A and Esteller M:

Genetic and epigenetic defects of the RNA modification machinery in

cancer. Trends Genet. 39:74–88. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Clay MR, Pinto EM, Cline C, Tran QT, Lin

T, Dyer MA, Shi L, Wu H, Pounds SB, Zambetti GP, et al: DNA

methylation profiling reveals prognostically significant groups in

pediatric adrenocortical tumors: A report from the international

pediatric adrenocortical tumor registry. JCO Precis Oncol.

3:PO.19.00163. 2019.

|

|

46

|

Mohan DR, Lerario AM, Else T, Mukherjee B,

Almeida MQ, Vinco M, Rege J, Mariani BMP, Zerbini MCN, Mendonca BB,

et al: Targeted assessment of G0S2 methylation identifies a rapidly

recurrent, routinely fatal molecular subtype of adrenocortical

carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 25:3276–3288. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li C, Tang Y, Li Q, Liu H, Ma X, He L and

Shi H: The prognostic and immune significance of C15orf48 in

pan-cancer and its relationship with proliferation and apoptosis of

thyroid carcinoma. Front Immunol. 14:11318702023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Oliver J, Garcia-Aranda M, Chaves P, Alba

E, Cobo-Dols M, Onieva JL and Barragan I: Emerging noninvasive

methylation biomarkers of cancer prognosis and drug response

prediction. Semin Cancer Biol. 83:584–595. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Suh I, Weng J, Fernandez-Ranvier G, Shen

WT, Duh Q, Clark OH and Kebebew E: Antineoplastic effects of

decitabine, an inhibitor of DNA promoter methylation, in

adrenocortical carcinoma cells. Arch Surg. 145:226–232. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Endo A, Ly T, Pippa R, Bensaddek D,

Nicolas A and Lamond AI: The chromatin assembly factor complex 1

(CAF1) and 5-Azacytidine (5-AzaC) affect cell motility in

src-transformed human epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 292:172–184.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li X, Li Y, Dong L, Chang Y, Zhang X, Wang

C, Chen M, Bo X, Chen H, Han W and Nie J: Decitabine priming

increases anti-PD-1 antitumor efficacy by promoting CD8+ progenitor

exhausted T cell expansion in tumor models. J Clin Invest.

133:e1656732023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang Y, Tong C, Dai H, Wu Z, Han X, Guo Y,

Chen D, Wei J, Ti D, Liu Z, et al: Low-dose decitabine priming

endows CAR T cells with enhanced and persistent antitumour

potential via epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 12:4092021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sarhadi VK and Armengol G: Molecular

biomarkers in cancer. Biomolecules. 12:10212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xu F, Guan Y, Ma Y, Xue L, Zhang P, Yang X

and Chong T: Bioinformatic analyses and experimental validation of

the role of m6A RNA methylation regulators in progression and

prognosis of adrenocortical carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY).

13:11919–11941. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Fu Y, Sun S, Bi J, Kong C and Yin L:

Expression patterns and prognostic value of m6A RNA methylation

regulators in adrenocortical carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore).

100:e250312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, Lin K, Zheng S,

Lu Z, Chen Y, Sulman EP, Xie K, Bogler O, et al: m(6)A Demethylase

ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by

sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer

Cell. 31:591–606. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Xiong J, He J, Zhu J, Pan J, Liao W, Ye H,

Wang H, Song Y, Du Y, Cui B, et al: Lactylation-driven

METTL3-mediated RNA m6A modification promotes

immunosuppression of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Mol Cell.

82:1660–1677. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Wang L, Dou X, Chen S, Yu X, Huang X,

Zhang L, Chen Y, Wang J, Yang K, Bugno J, et al: YTHDF2 inhibition