Introduction

The cancer with the highest mortality rate globally

is lung cancer, accounting for ~18.7% of all cancer-associated

deaths (1). Mutations in the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are among the typical

driver gene alterations found in non-small cell lung carcinoma

(NSCLC) (2). For patients with

advanced NSCLC and sensitive EGFR mutations, tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs) are recommended as first-line therapy by

established guidelines (3–5). Targeted therapies can extend the

survival of patients with advanced NSCLC and driver gene mutations,

with life expectancy ranging from 12.9–21.9 months (6,7).

Despite the common use of first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs in

treating patients with NSCLC, most patients eventually experience

acquired resistance, resulting in disease recurrence and

progression (8). The primary cause

of this resistance is the T790M mutation. The ASPIRATION study

demonstrated that adhering to the original targeted therapy after

disease progression whilst on erlotinib could slow down disease

progression, with a notable difference in progression-free survival

(PFS). Specifically, patients who continued with the original

therapy achieved a PFS of 14.1 months, whereas those who

discontinued the therapy experienced a shorter PFS of 11.0 months,

with corresponding median overall survival (OS) of 33.6 and 22.5

months, respectively (9). Moreover,

a study by Chaft et al (10)

reported that among 61 cases, 14 experienced disease recurrence

after discontinuing EGFR-TKIs, with a median recurrence time of 8

days. These findings underscore the possibility for the original

targeted therapy to control disease in patients who develop

resistance. Therefore, guidelines from Europe, America and China

recommend that these patients continue with the original EGFR-TKI

treatment regimen.

Certain patients exhibit oligometastasis, with

metastasis limited to a few organs or regions. Generally,

oligometastasis is categorized as inoperable stage III or IV;

however, it is a unique condition between locally advanced and

broadly disseminated stage IV. Guidelines recommend local treatment

for these patients (11), and

common local treatment methods include surgical resection,

radiation therapy, microwave ablation, radiofrequency ablation,

particle implantation and cryoablation (12,13).

Gamma Knife is a type of stereotactic body radiation

therapy (SBRT) radiotherapy technology. Through non-coplanar

rotational irradiation, the radiation converges at a single focal

point, creating an ellipsoidal high-dose region to cover the tumor

target area. The dose in the central area of the tumor is markedly

higher than that in the peripheral area. This design can more

effectively kill hypoxic cells inside the tumor that are resistant

to radiotherapy. The dose rapidly attenuates at the tumor

periphery, and the notable focusing capability results in a smaller

overall volume of normal lung tissue being irradiated and a lower

irradiation dose, making it more suitable for treating multiple

lesions. Gamma Knife is commonly used in Europe and the United

States to treat brain tumors or brain metastases. However, in

China, it is also used to treat primary and metastatic tumors in

the body (14), with several

studies indicating its notable efficacy (14–16).

In 2006, Xia et al (14)

reported marked results using Gamma Knife therapy for the treatment

of early-stage lung cancer. Furthermore, Zhang et al

(15) reported certain survival

benefits using whole-body Gamma Knife radiotherapy combined with

thermochemotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. For

patients with oligometastatic NSCLC, systemic therapy combined with

surgery or radiation treatment was reported to provide improved

treatment effect compared with systemic therapy alone (17–19).

Similarly, the adoption of first-generation EGFR-TKIs in

conjunction with local consolidation therapy (LCT) has also been

reported to demonstrate superior treatment effects compared with

the TKI-only treatment group (20–24).

However, most existing studies have focused on the combination of

EGFR-TKIs with surgical interventions or radiotherapy for

intracranial or other metastatic lesions (21,25,26).

There are few reports on the combined treatment of primary lung

lesions, with recent studies mostly concerning third-generation

EGFR-TKIs in combination therapies (27,28).

Therefore, the present retrospective study aimed to evaluate the

impact of Gamma Knife therapy on primary pulmonary lesions combined

with first-generation EGFR-TKIs treatment for advanced lung

adenocarcinoma on disease control and survival of patients.

Patients and methods

Study population

The present retrospective, single-arm study was

performed on a small cohort of 35 patients diagnosed with advanced

lung adenocarcinoma harboring EGFR-sensitive mutations. These

patients underwent both targeted therapy and radiation at the 901st

Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the People's

Liberation Army (Hefei, China) between October 2014 and November

2021. The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Commission and

all patients signed informed consent prior to treatment.

Patient selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Any sex

or age; ii) pathologically confirmed diagnosis of lung

adenocarcinoma; iii) history of post-surgical lung cancer

recurrence; iv) prior exposure to adjuvant or neoadjuvant

chemotherapy; v) genetic status indicating EGFR-sensitive

mutations, specifically exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R mutation;

vi) clinical staging of unresectable stage III or IV with

oligometastatic; vii) use of the first generation EGFR-TKIs as a

first-line treatment that achieved documented disease control;

viii) resistance after first-generation EGFR-TKIs as first-line

therapy, followed by Gamma Knife treatment for the primary lesions;

ix) presence of at least one measurable lesion as defined by the

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria

(29); and x) Eastern Cooperative

Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (30) ranging from 0–2.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Co-existing malignancies; ii) severe underlying conditions such as

cardiovascular diseases, liver disease or kidney disease; iii)

presence of other genetic mutations, including EGFR 20 insertions,

anaplastic lymphoma kinase, hepatocyte growth factor receptor and

c-ROS oncogene 1; iv) concurrent use of other antitumor agents as

part of first-line treatment, including anti-angiogenic agents,

immunotherapy or chemotherapy; v) unmanageable adverse reactions to

first-generation EGFR-TKIs; vi) disease not controlled following

first-generation EGFR-TKI treatment due to primary resistance; and

vii) presence of widespread systemic metastases.

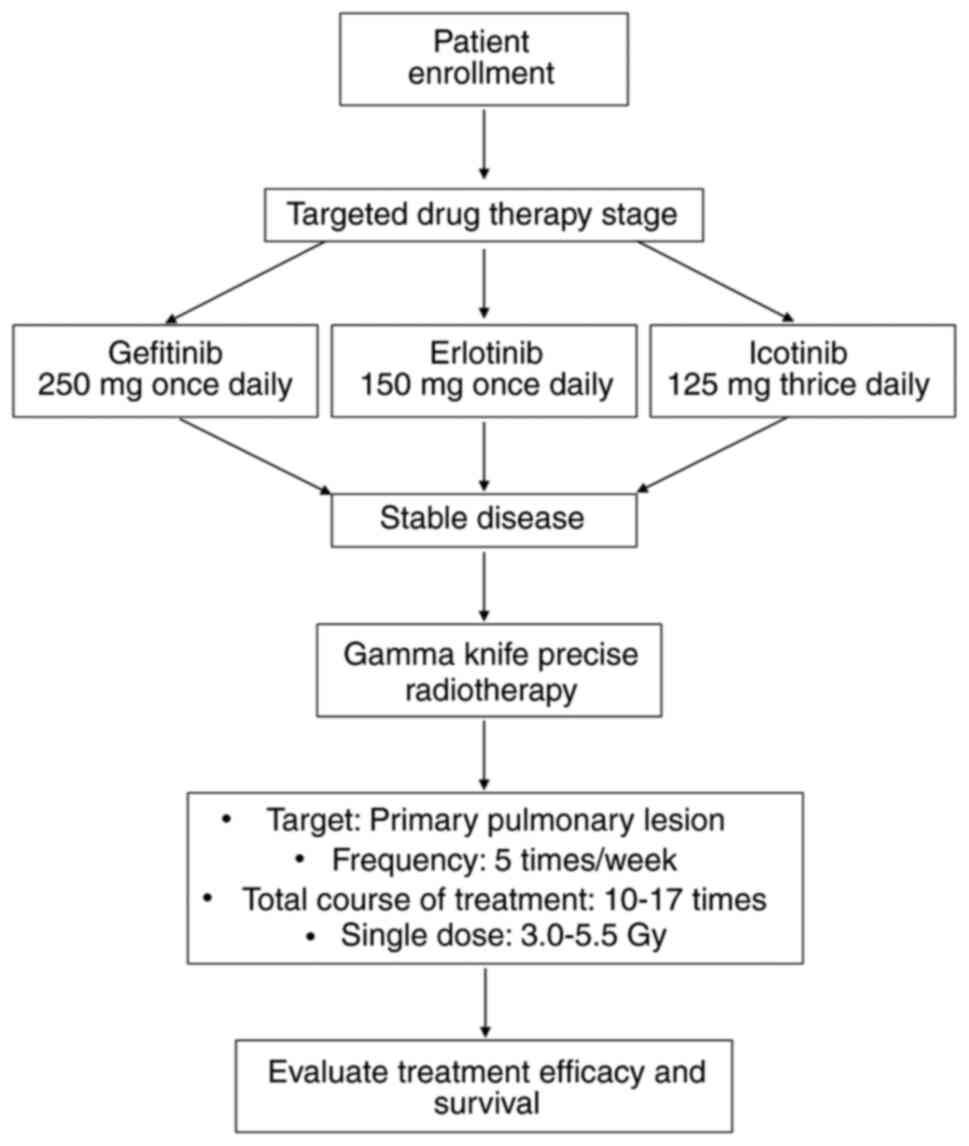

Treatment protocol

Following disease control achieved through

first-line treatment with first-generation EGFR-TKIs, lung lesions

exhibited stability or slight progression without reaching

progressive disease (PD). Consequently, patients underwent Gamma

Knife radiosurgery for lung cancer for 10–17 sessions administered

five times per week, with each session delivering a fractionated

dose ranging from 3.0–5.5 Gy. The specific treatment protocol is

detailed below.

EGFR-TKI targeted therapy

Patients received oral administration of either

gefitinib (250 mg, once daily), erlotinib (150 mg, once daily) or

icotinib (125 mg, thrice daily). Dose adjustments were permitted in

response to any adverse events experienced by the patients. Drugs

were preferentially selected according to the clinical features of

the patients. For example, for patients with mild abnormal liver

function, drugs mainly metabolized by the kidneys (such as

gefitinib) were preferred; for patients with concurrent chronic

lung diseases, the applicability of erlotinib was prioritized for

evaluation considering its potentially lower risk of pulmonary

adverse reactions. Additionally, drugs that were economically

affordable and easily accessible to patients were selected to

improve long-term treatment compliance. Furthermore, all drug

selections referred to the recommendations for first-generation

EGFR-TKIs in the latest version of lung cancer diagnosis and

treatment guidelines (such as National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Guidelines and Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines)

(31,32). In scenarios where the guidelines did

not clearly recommend a priority, a multidisciplinary team

discussion model was adopted, and decisions were made jointly with

the wishes of the patients. Finally, the balance of the

distribution of baseline data on clinical characteristics was

assessed among the three groups of patients taking gefitinib,

erlotinib and icotinib. Table I

indicates that the samples of patients receiving targeted therapy

in the three groups were comparable in terms of sex, age, ECOG

score, disease stage, gene mutation type and smoking status, with

no significant differences demonstrated.

| Table I.Analysis of baseline characteristics

of patients in three groups of targeted therapy. |

Table I.

Analysis of baseline characteristics

of patients in three groups of targeted therapy.

|

| Targeted drug |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | Erlotinib

(n=13) | Gefitinib

(n=10) | Icotinib

(n=12) | F | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

| - | 0.817 |

|

Female | 9 (69.23) | 6 (60.00) | 9 (75.00) |

|

|

|

Male | 4 (30.77) | 4 (40.00) | 3 (25.00) |

|

|

| Age | 62.23±12.52 | 62.40±12.56 | 62.25±13.96 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

| - | 0.821 |

| 0 | 1 (7.69) | 1 (10.00) | 2 (16.67) |

|

|

| 1 | 12 (92.31) | 9 (90.00) | 10 (83.33) |

|

|

| Stage |

|

|

| - | 0.821 |

|

III | 1 (7.69) | 1 (10.00) | 2 (16.67) |

|

|

| IV | 12 (92.31) | 9 (90.00) | 10 (83.33) |

|

|

| Mutation type |

|

|

| - | 0.228 |

| EGFR

19del | 10 (76.92) | 4 (40.00) | 8 (66.67) |

|

|

| EGFR

exon21 L858R | 3 (23.08) | 6 (60.00) | 4 (33.33) |

|

|

| Smoking status |

|

|

| - | 0.392 |

| No | 12 (92.31) | 7 (70.00) | 10 (83.33) |

|

|

|

Yes | 1 (7.69) | 3 (30.00) | 2 (16.67) |

|

|

Stereotactic radiation therapy

The fourth-generation LUNA-260 Gamma Knife system

(Shenzhen Yiti Medical Treatment Technology Co., Ltd.) was

employed. Patients were positioned supine and secured using a

vacuum bag. A helical CT scan (slice thickness, 3–5 mm) was

performed on the lesion area, including the entire lung, to obtain

localization images. The gross tumor volume (GTV) corresponded with

the visibility of the tumor in the lung window; the clinical target

volume (CTV) extended 5 mm beyond the GTV; and the planning target

volume (PTV) extended a further 5 mm from the CTV. Regarding the

determination of the radiation treatment target area, prior to

Gamma Knife treatment, the operator instructed patients to maintain

steady thoracic breathing (avoiding diaphragmatic breathing) to

minimize irregular breathing. Additionally, the hospital department

designed a set of devices to effectively reduce respiratory motion

and positioning errors. These included extra anchoring points for

positioning that were placed on the chest wall of the patient, and

a hydrolyzed plastic body mold to cover the external thorax.

Verification through 4-dimensional CT has shown that using a GTV +

10 mm margin can cover the risk of subclinical lesion extension

whilst reducing the radiation dose to normal tissues (33). Therefore, the internal target volume

region was no longer delineated separately. For lesions <3 cm,

the 50% isodose line encompassed 100% of the PTV, the 60% isodose

line encompassed 90% of the CTV and the 70% isodose line

encompassed 80% of the GTV. In cases where the lesion was >5 cm,

the 50–60% isodose line encompassed 100% of the GTV. The

fractionated dose delivered per session ranged from 3.0–5.5 Gy and

it was provided five times weekly for a total of 10–17 sessions,

with a cumulative peripheral dose of 45–55 Gy.

Treatment after progression

If disease progression occurred after the

combination of first-generation EGFR-TKI treatment and Gamma Knife

therapy, subsequent treatment options were determined according to

genetic testing results. These options included third-generation

EGFR-TKIs, chemotherapy, anti-angiogenic therapy, immunotherapy and

radiation therapy directed at metastatic lesions.

Efficacy evaluation and prognostic

analysis indicators

Clinical data, including patient demographics, tumor

characteristics, staging and radiological features, were recorded

prior to treatment. Patients were followed up to gather

radiological assessment results and details of any adverse events

following therapy: Following completion of Gamma Knife treatment,

patients underwent chest and abdominal CT scans after 1, 3, 6 and

12 months during the first year, and at 6-month intervals during

the second year. RECIST 1.1 criteria were employed to assess the

treatment efficacy. Short-term treatment outcomes were assessed

within 3–6 months post-therapy. Patients were classified into 1/4

categories based on their response: Complete response (CR), partial

response (PR), stable disease (SD) or PD. In the present study, the

objective response rate (ORR), which equals CR + PR, was considered

indicative of treatment effectiveness. For long-term outcomes,

survival data, specifically PFS and OS, were collected until the

follow-up cutoff date of December 31, 2023. Finally, any adverse

reactions were recorded: The primary side effects of EGFR-TKIs

included rash and diarrhea, whilst the main adverse reactions

observed following lung Gamma Knife treatment were radiation

pneumonitis.

Statistical methods

Primary study endpoints included PFS and OS, whilst

secondary endpoints included the ORR and safety. PFS was defined as

the time from the initiation of EGFR-TKIs to the occurrence of

disease progression, and OS was defined as the time from the

initiation of EGFR-TKIs to death or the end of follow-up. SPSS 25

software (IBM Corp.) was used for analysis, with statistical

methods including univariate linear regression (single-factor) and

multivariate linear regression (multi-factor). The Kaplan-Meier

method was adopted for assessing clinical treatment efficacy in

patients. Moreover, Fisher's Exact Test or analysis of variance was

used to assess the balanced distribution of baseline data for

clinical characteristics (including sex, age, EGFR mutation

subtype, tumor stage, ECOG performance status and smoking status)

among the three groups of patients treated with gefitinib,

erlotinib and icotinib. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

A cohort of 35 patients was included in the final

analysis. Fig. 1 illustrates the

treatment plan for these patients. Detailed clinical

characteristics of the patients are presented in Table II.

| Table II.Characteristics of the 35

patients |

Table II.

Characteristics of the 35

patients

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 11 (31) |

|

Female | 24 (69) |

| Age |

|

| ≥62

years | 20 (57) |

| <62

years | 15 (43) |

| Stage |

|

|

III | 4 (11) |

| IV | 31 (89) |

| Visceral

metastasis |

|

|

Present | 12 (34) |

|

Absent | 23 (66) |

| CEA |

|

| ≥10

ng/ml | 17 (49) |

| <10

ng/ml | 18 (51) |

| Smoking status |

|

|

Yes | 6 (17) |

| No | 29 (83) |

| ECOG performance

status |

|

| 0 | 4 (11) |

| 1 | 31 (89) |

| Mutation type |

|

| Exon 19

Del | 22 (63) |

| Exon 21

L858R | 13 (37) |

| Type of

EGFR-TKIs |

|

|

Gefitinib | 10 (29) |

|

Afatinib | 12 (34) |

|

Erlotinib | 13 (37) |

| Diameter of lung

lesions treated with gamma knife |

|

| ≥3

cm | 13 (37) |

| <3

cm | 22 (63) |

Efficacy and survival

Among the patients, 15 (43%) achieved CR, 12 (34%)

had a PR, 8 (23%) showed SD and no patients exhibited PD, leading

to an ORR of 77%. Moreover, according to the Radiation Therapy

Oncology Group classification, radiation pneumonitis was graded as

grade III in 1 patient (3%), grade II in 6 patients (17%) and grade

I in 17 patients (49%), whilst no adverse reactions were observed

in 11 patients (31%) (34).

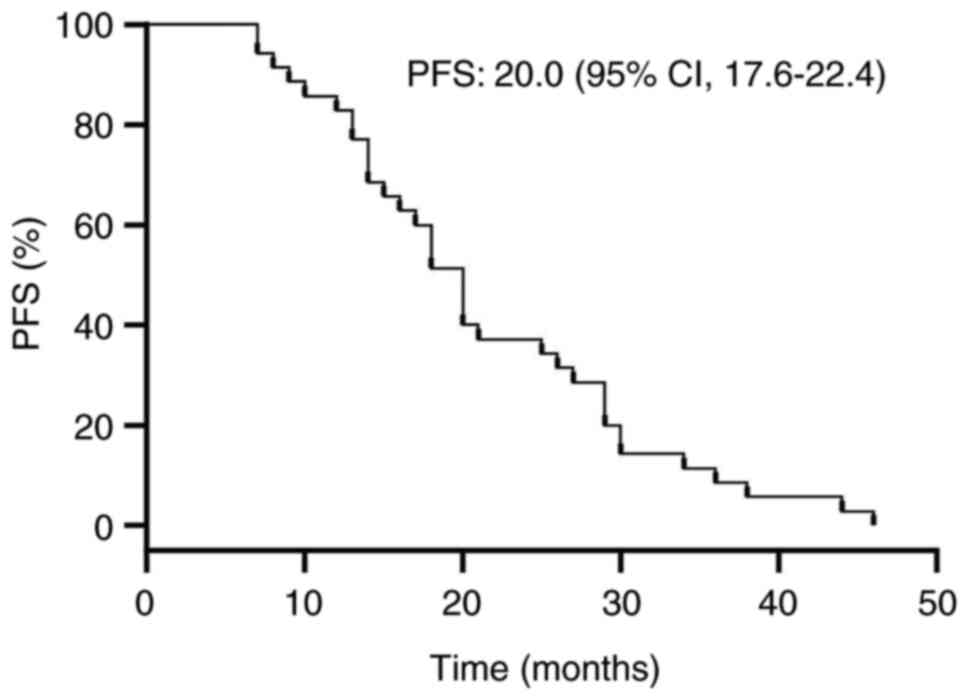

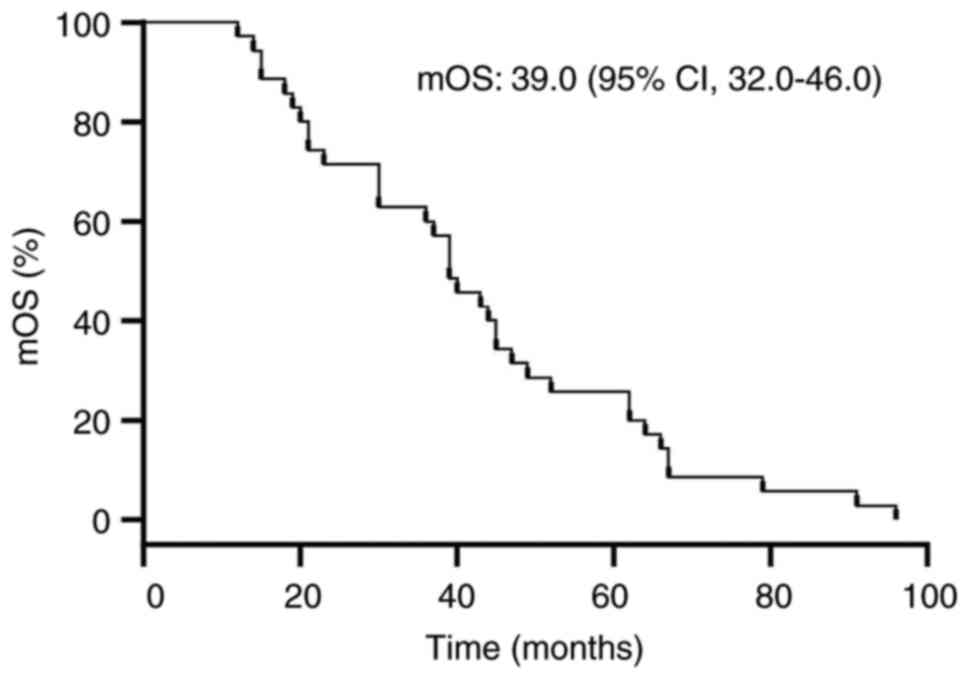

Outcomes of first-generation EGFR-TKIs

combined with Gamma Knife therapy

As of the December 2023 follow-up, descriptive

statistics indicated the PFS was 20 months (range, 17.6–22.4

months) and the median OS was 39 months (range, 32.0–46.0 months)

for the cohort of 35 patients. The corresponding PFS and median OS

survival curve functions are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Factors influencing the efficacy of

Gamma Knife treatment

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed

to evaluate the association between different factors on PFS,

including sex, mutation type, cancer stage, visceral metastasis,

age, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, types of targeted

therapies, ECOG performance status, size of lung lesions, smoking

status and severity of radiation pneumonitis (Table III). Univariate analysis revealed

a survival advantage among patients aged ≥62 years, with CEA <10

ng/ml and with grade I or no radiation pneumonitis; however, the

differences were not statistically significant. Multivariate

analysis demonstrated that non-smoking patients, CEA <10 ng/ml,

grade I or no radiation pneumonitis after treatment, and treated

with icotinib experienced significantly longer PFS (all

P<0.05).

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analyses

associated with progression-free survival. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

associated with progression-free survival.

|

|

|

| Univariate

regression | Multivariate

regression |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factor | n | Mean PFS,

months | Ba (95% CI) | P-value | Ba (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| <62

years | 15 | 18.47 | - | - | - | - |

| ≥62

years | 20 | 23.50 | 5.033

(−1.698–11.765) | 0.152 | 5.047

(−1.561–11.655) | 0.149 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 11 | 21.91 | - | - | - | - |

|

Female | 24 | 21.08 | −0.826

(−8.226–6.575) | 0.828 | −6.390

(−14.740–1.960) | 0.148 |

| ECOG performance

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 4 | 26.75 | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 31 | 20.65 | −6.105

(−16.708–4.499) | 0.267 | −7.704

(−18.403–2.995) | 0.172 |

| Smoking status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 29 | 21.79 | - | - | - | - |

|

Yes | 6 | 19.17 | −2.626

(−11.705–6.452) | 0.575 | −14.113

(−24.541–3.685) | 0.015b |

| Mutation type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Exon 19

Del | 22 | 22.45 | - | - | - | - |

| Exon 21

L858R | 13 | 19.46 | −2.993

(−10.035–4.049) | 0.411 | −1.608

(−8.518–5.303) | 0.653 |

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

III | 4 | 20.75 | - | - | - | - |

| IV | 31 | 21.42 | 0.669

(−10.134–11.473) | 0.904 | 12.548

(0.566–24.529) | 0.052 |

| Visceral

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 23 | 21.52 | - | - | - | - |

|

Yes | 12 | 21.00 | −0.522

(−7.763–6.719) | 0.889 | −3.050

(−11.218–5.118) | 0.472 |

| CEA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| <10

ng/ml | 18 | 24.17 | - | - | - | - |

| >10

ng/ml | 17 | 18.35 | −5.814

(−12.400–0.773) | 0.093 | −13.172

(−20.989–5.354) | 0.003c |

| Types of targeted

drugs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Icotinib | 12 | 23.08 | - | - | - | - |

|

Erlotinib | 13 | 19.66 | −3.468

(−11.648–4.712) | 0.412 | −9.219

(−16.598–1.840) | 0.023b |

|

Gefitinib | 10 | 20.50 | −1.583

(−10.333–7.166) | 0.725 | −7.505

(−17.397–2.387) | 0.151 |

| Size of lung

lesions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| <3

cm | 22 | 20.45 | - | - | - | - |

| ≥3

cm | 13 | 22.85 | 2.392

(−4.677–9.460) | 0.512 | 6.673

(−0.701–14.046) | 0.090 |

| Radiation

pneumonitis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grade I

+ None | 28 | 22.46 | - | - | - | - |

| Grade

II + III | 7 | 16.86 | −5.607

(−13.987–2.772) | 0.199 | −8.168

(−15.524–0.812) | 0.041b |

Discussion

In the present study, Gamma Knife treatment extended

both PFS and OS in patients with advanced EGFR-mutant lung

adenocarcinoma receiving first-line EGFR-TKIs. Notably, enhanced

survival benefits were observed in specific subgroups, such as

non-smokers, patients with a CEA level of <10 ng/ml, grade I or

no radiation pneumonitis after treatment, and those receiving

icotinib. Previous studies have reported that integrating LCT with

systemic treatments can boost survival rates in patients with

oligometastatic NSCLC (18,35). Additionally, LCT has also been

reported to extend survival for patients undergoing EGFR-TKIs or

chemotherapy (12,18–20,36).

Moreover, previous studies have reported that

radiation therapy or primary lung tumor resection combined with

systemic treatment can yield survival benefits in patients with

metastatic NSCLC (21,22,37,38).

Takenaka et al (39)

reported that salvage surgery can extend the median OS of patients

treated with EGFR-TKI to ~66 months. Tseng et al (38) demonstrated that primary tumor

resection (PTR) could increase the PFS and OS of patients to 25.1

and 56.8 months, respectively. Kuo et al (21) reported that the median PFS of

patients with stage IV EGFR-mutant NSCLC receiving PRT and

first-line TKI treatment increased from 13.0 to 29.6 months,

compared with patients not receiving PTR treatment. Furthermore, in

the study by Hsu et al (22), compared with not receiving radiation

therapy, first-generation EGFR-TKI treatment followed by radiation

therapy for primary lung cancer increased PFS from 10.9 to 27.5

months and OS from 38.0 to not reached. Elamin et al

(40) reported that oligometastatic

disease (≤3 metastatic sites) occurred in 8/12 patients treated

with TKIs and LCT. Of the 12 cases, 11 underwent radiation therapy

and 1 underwent surgical resection. Furthermore, in comparison with

TKIs alone, LCT following TKI treatment notably prolonged the PFS

(14 vs. 36 months). Deng et al (41) assessed how synchronous radiation

therapy (CPRT) impacts the primary tumor during first-line

treatment with icotinib, and reported that the CPRT group achieved

a median PFS of 13.6 months, compared with only 10.6 months in the

non-CPRT group. Moreover, in a study by Peng et al (23), 13 patients with stage IV lung cancer

who received EGFR-TKIs and SBRT to primary lung lesions had an

median PFS of 27.3 months and an median OS of 49.1 months.

Additionally, radiation therapy to the primary site alone offered

improved benefits compared with radiation therapy targeted solely

at metastatic sites or a combination of both approaches. Notably,

osimertinib was not employed as the first-line treatment plan in

any of the aforementioned studies.

Reducing the tumor burden in the primary site can

enhance the efficacy of systemic therapy (42,43).

Lin et al (44) demonstrated

that salvage surgery performed before the disease advances can

remove TKI-resistant subclones, thereby improving survival results.

Furthermore. according to Al-Halabi et al (45), a notable number of patients

receiving EGFR-TKIs initially experienced failure at the primary

site, with a recurrence rate of 47.0% for primary tumors. The study

by Hsu et al (22) also

reported that the radiotherapy group had a reduced rate of primary

tumor progression compared with the group not receiving radiation

therapy. These findings indicate that integrating primary tumor

control therapy (PTCT), whether through surgical resection or

radiation therapy, enhances overall treatment outcomes and prolongs

survival.

Additionally, research has demonstrated that

combining EGFR-TKIs with radiotherapy can lead to improved survival

in patients. Radiotherapy employs high-energy rays to target tumor

cells and disrupt their genetic material. It can induce EGFR

phosphorylation, which affects the efficacy of radiotherapy and may

lead to resistance. Conversely, EGFR-TKIs can inhibit EGFR

phosphorylation, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of

radiotherapy (46). This

synergistic mechanism provides a theoretical foundation for

subsequent research. Furthermore, PTCT can restore immune function,

reduce subclones of tumor stem cells and decrease tumor

heterogeneity, thereby enhancing the effect of EGFR-TKIs (22,38,47).

In early studies, the values of PFS were smaller for patients with

the L858R mutation than for those with the 19 deletions (19del)

(48–50). In the present study, the PFS for the

19-exon deletion subgroup was 22.5 months, whereas for the L858R

mutation subgroup it was 19.5 months, with no statistically

significant difference observed. Factors such as sex, smoking

status and cancer stage did not significantly affect PFS,

indicating that all subgroups could benefit from Gamma Knife

therapy.

The FLAURA trial reported that osimertinib achieved

a PFS of 18.9 months and an OS of 38.6 months (51,52).

In the present study, the PFS and OS data of Gamma Knife treatment

combined with first-generation EGFR-TKI were broadly consistent

with those of third-generation TKI monotherapy (such as

osimertinib) in a similar population reported in the FLAURA trial,

and the side effects were controllable; therefore, it is a viable

option from a pharmacoeconomic perspective. However, it should be

noted that the present study did not set up a third-generation TKI

treatment group as a control. For patients eligible for Gamma

Knife, the use of TKIs alone without local treatment (such as

Stereotactic Radiosurgery/Gamma Knife) was not a routine or

recommended practice in the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics

Support Force of the People's Liberation Army. Therefore, among the

concurrent, same-center patient population eligible for Gamma

Knife, it was difficult for the present study to identify a

sufficient number of suitable patients with comparable baseline

characteristics who only received TKIs without any local treatment

as the control group. Forcibly incorporating a poorly qualified

control group would undermine the overall credibility of the

research. Therefore, the current conclusion is based on a

comparative analysis of indirect efficacy indicators among similar

patient populations in different trials, rather than direct

comparisons through head-to-head trials. Due to the differences in

the treatment scenarios and patient screening criteria between the

two, the statistical significance of the comparisons must be

carefully interpreted. The main contribution of the present study

lies in the description and preliminarily evaluation of a promising

sequential treatment strategy, whose results need to be validated

in future prospective controlled studies.

The focus of the present study was on consolidation

therapy for the primary lesion of lung cancer (excluding metastatic

lesions), which has not been systematically explored in existing

studies, to the best of our knowledge. Current similar studies

mainly focus on local treatment of metastatic lesions (12,26),

lacking a specific analysis of the combination therapy of

first-generation TKIs and Gamma Knife for the primary lesion.

Through long-term follow-up data (PFS of 20 months and median OS of

39 months), the present efficacy and safety profile provide

patients with one more treatment option.

Case inclusion in the present study preceded the

subsequent regulatory approval of osimertinib for this indication

(51). The treatment regimen of the

present study may serve as an alternative option for situations in

which third-generation TKIs cannot be used for treatment due to

limited drug supply in certain developing countries or regions,

insufficient financial affordability of patients, adverse reactions

or contraindications. In the future, head-to-head research is

needed to further compare the cost-effectiveness of

first-generation TKIs combined with Gamma Knife, and of osimertinib

monotherapy, in specific populations, providing more basis for

individualized treatment.

Moreover, it should be noted that the present study

has certain limitations. First, as it is a retrospective study

without a control group, there may be selection bias. Second, a

small sample size can lead to limited statistical power, which may

affect the statistical significance of certain subgroup

comparisons. Third, the follow-up time may have not been sufficient

to obtain mature OS results from subgroup analyses and follow-up

studies should extend the follow-up time to enhance the credibility

of long-term interpretations. Large-scale prospective experiments

are still needed to verify the findings proposed in the present

study in the future.

In conclusion, combining first-generation EGFR-TKIs

with Gamma Knife therapy can delay EGFR resistance and extend PFS

and OS with a low incidence of toxicity and side effects. The

results of the present study indicate that the combination of

first-generation EGFR-TKIs and Gamma Knife therapy for the

treatment of primary lung lesions is a viable therapeutic option

for patients with advanced EGFR-sensitive mutations. Nevertheless,

these results should be further verified in future prospective

research.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Anhui Province Health

Research Project Key Project (grant no. AHWJ2023BAc10023).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DLv was responsible for the study's conception and

research protocol design. BX, DLu and ZL participated in study data

acquisition, including data collection and patient management. DW,

HM, LZ and ML analyzed the collected data and interpreted the

results to derive key findings. DLv, BX, and DW collaborated on

writing the manuscript's initial draft. All authors actively

participated in the subsequent review and critical revisions, and

all authors have read and approved the final manuscript. DLv and BX

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors are

accountable for the intellectual content of the work and agree to

be responsible for all aspects of it.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the review board

ethics committee of the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics

Support Force of the People's Liberation Army (approval no.

LYAHW2023BAc1003). The requirement for written informed consent was

waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. All data were

anonymized prior to analysis and handled according to institutional

and ethical standards.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature.

511:543–550. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara

S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I,

et al: Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer

with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 362:2380–2388. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R,

Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Palmero R, Garcia-Gomez R,

Pallares C, Sanchez JM, et al: Erlotinib versus standard

chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with

advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer

(EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol. 13:239–246. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shen YW, Zhang XM, Li ST, Lv M and Yang J,

Wang F, Chen ZL, Wang BY, Li P, Chen L and Yang J: Efficacy and

safety of icotinib as first-line therapy in patients with advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 9:929–935. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu YL, Zhou C, Cheng Y, Lu S, Chen GY,

Huang C, Huang YS, Yan HH, Ren S, Liu Y and Yang JJ: Erlotinib as

second-line treatment in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung

cancer and asymptomatic brain metastases: A phase II study

(CTONG-0803). Ann Oncol. 24:993–999. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Iuchi T, Shingyoji M, Sakaida T, Hatano K,

Nagano O, Itakura M, Kageyama H, Yokoi S, Hasegawa Y, Kawasaki K

and Iizasa T: Phase II trial of gefitinib alone without radiation

therapy for Japanese patients with brain metastases from

EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 82:282–287. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Roper N, Brown AL, Wei JS, Pack S,

Trindade C, Kim C, Restifo O, Gao S, Sindiri S, Mehrabadi F, et al:

Clonal evolution and heterogeneity of osimertinib acquired

resistance mechanisms in EGFR mutant lung cancer. Cell Rep Med.

1:1000072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Park K, Yu CJ, Kim SW, Lin MC, Sriuranpong

V, Tsai CM, Lee JS, Kang JH, Chan KC, Perez-Moreno P, et al:

First-line erlotinib therapy until and beyond response evaluation

criteria in solid tumors progression in asian patients with

epidermal growth factor receptor Mutation-positive Non-Small-Cell

lung cancer: The ASPIRATION study. JAMA Oncol. 2:305–312. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chaft JE, Oxnard GR, Sima CS, Kris MG,

Miller VA and Riely GJ: Disease flare after tyrosine kinase

inhibitor discontinuation in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer

and acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib: Implications for

clinical trial design. Clin Cancer Res. 17:6298–6303. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Heitmann J and Guckenberger M:

Perspectives on oligometastasis: Challenges and opportunities. J

Thorac Dis. 10:113–117. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hu F, Xu J, Zhang B, Li C, Nie W, Gu P, Hu

P, Wang H, Zhang Y, Shen Y, et al: Efficacy of local consolidative

therapy for oligometastatic lung adenocarcinoma patients harboring

epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Clin Lung Cancer.

20:e81–e90. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Seong H, Kim SH, Kim MH, Kim J and Eom JS:

Additional local therapy before disease progression for

EGFR-mutated advanced lung cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 13:491–502. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xia T, Li H, Sun Q, Wang Y, Fan N, Yu Y,

Li P and Chang JY: Promising clinical outcome of stereotactic body

radiation therapy for patients with inoperable Stage I/II

non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

66:117–125. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang LP, Nie Q, Kang JB, Wang B, Cai CL,

Li JG and Qi WJ: Efficacy of whole body gamma-knife radiotherapy

combined with thermochemotherapy on locally advanced pancreatic

cancer. Chin J Cancer. 27:1204–1207. 2008.(In Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Yu W, Tang L, Lin F, Li D, Wang J, Yang Y

and Shen Z: Stereotactic radiosurgery, a potential alternative

treatment for pulmonary metastases from osteosarcoma. Int J Oncol.

44:1091–1098. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu K, Zheng D, Xu G, Du Z and Wu S: Local

thoracic therapy improve prognosis for stage IV non-small cell lung

cancer patients combined with chemotherapy: A Surveillance,

Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. PLoS One.

12:e01873502017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, Blumenschein GR

Jr, Hernandez M, Lee JJ, Ye R, Palma DA, Louie AV, Camidge DR, et

al: Local consolidative therapy vs. maintenance therapy or

observation for patients with oligometastatic Non-Small-Cell lung

cancer: Long-Term results of a Multi-Institutional, Phase II,

randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 37:1558–1565. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, Gaede S,

Louie AV, Haasbeek C, Mulroy L, Lock M, Rodrigues GB, Yaremko BP,

et al: Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive

treatment of oligometastatic cancers: Long-term results of the

SABR-COMET phase II randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 38:2830–2838.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wang XS, Bai YF, Verma V, Yu RL, Tian W,

Ao R, Deng Y, Zhu XQ, Liu H, Pan HX, et al: Randomized trial of

First-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor with or without radiotherapy

for synchronous oligometastatic EGFR-Mutated Non-Small cell lung

cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 115:742–748. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kuo SW, Chen PH, Lu TP, Chen KC, Liao HC,

Tsou KC, Tsai TM, Lin MW, Hsu HH and Chen JS: Primary tumor

resection for Stage IV Non-small-cell lung cancer without

progression After First-Line epidermal growth factor

receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment: A retrospective

Case-Control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 29:4873–4884. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hsu KH, Huang JW, Tseng JS, Chen KW, Weng

YC, Yu SL, Yang TY, Huang YH, Chen JJW, Chen KC, et al: Primary

tumor radiotherapy during EGFR-TKI disease control improves

survival of treatment naïve advanced EGFR-Mutant lung

adenocarcinoma patients. Onco Targets Ther. 14:2139–2148. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Peng P, Gong J, Zhang Y, Zhou S, Li Y, Han

G, Meng R, Chen Y, Yang M, Shen Q, et al: EGFR-TKIs plus

stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for stage IV Non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A prospective, multicenter, randomized,

controlled phase II study. Radiother Oncol. 184:1096812023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Xu Q, Zhou F, Liu H, Jiang T, Li X, Xu Y

and Zhou C: Consolidative local ablative therapy improves the

survival of patients with synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC

harboring EGFR Activating mutation treated with first-line

EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. 13:1383–1392. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Niu K, Chen X, Lu D,

Kong R, Chen Z and Sun J: Continued EGFR-TKI with concurrent

radiotherapy to improve time to progression (TTP) in patients with

locally progressive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after

front-line EGFR-TKI treatment. Clin Transl Oncol. 20:366–373. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chiou GY, Chiang CL, Yang HC, Shen CI, Wu

HM, Chen YW, Chen CJ, Luo YH, Hu YS, Lin CJ, et al: Combined

stereotactic radiosurgery and tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy

versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy alone for the treatment of

non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases. J

Neurosurg. 137:563–570. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wu JJ, Tseng JS, Zheng ZR, Chu CH, Chen

KC, Lin MW, Huang YH, Hsu KH, Yang TY, Yu SL, et al: Primary tumor

consolidative therapy improves the outcomes of patients with

advanced EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma treated with first-line

osimertinib. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 16:175883592312206062024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Guo T, Ni J, Yang X, Li Y, Li Y, Zou L,

Wang S, Liu Q, Chu L, Chu X, et al: Pattern of Recurrence analysis

in metastatic EGFR-Mutant NSCLC treated with osimertinib:

Implications for consolidative stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 107:62–71. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ando M, Ando Y, Hasegawa Y, Shimokata K,

Minami H, Wakai K, Ohno Y and Sakai S: Prognostic value of

performance status assessed by patients themselves, nurses, and

oncologists in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer.

85:1634–1639. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley

W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, D'Amico

TA, et al: NCCN guidelines insights: Non-Small cell lung cancer,

version 2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20:497–530. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ,

Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, et al: Erlotinib versus

chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced

EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL,

CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study.

Lancet Oncol. 12:735–742. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ju X, Li M, Zhou Z, Zhang K, Han W, Fu G,

Cao Y and Wang L: 4D-CT-based plan target volume (PTV) definition

compared with conventional PTV definition using general margin in

radiotherapy for lung cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 36:34–38.

2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

34

|

Cox JD, Stetz J and Pajak TF: Toxicity

criteria of the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) and the

european organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC).

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 31:1341–1346. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang S, Sun Q, Cai F, Li H and Zhou Y:

Local therapy treatment conditions for oligometastatic non-small

cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 12:10281322022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, Tumati V,

Ahn C, Hughes RS, Dowell JE, Cheedella N, Nedzi L, Westover KD, et

al: Consolidative radiotherapy for limited metastatic

Non-Small-Cell lung cancer: A Phase 2 randomized clinical trial.

JAMA Oncol. 4:e1735012018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ohtaki Y, Shimizu K, Suzuki H, Suzuki K,

Tsuboi M, Mitsudomi T, Takao M, Murakawa T, Ito H, Yoshimura K, et

al: Salvage surgery for non-small cell lung cancer after tyrosine

kinase inhibitor treatment. Lung Cancer. 153:108–116. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Tseng JS, Hsu KH, Zheng ZR, Yang TY, Chen

KC, Huang YH, Su KY, Yu SL and Chang GC: Primary tumor resection is

associated with a better outcome among advanced EGFR-Mutant lung

adenocarcinoma patients receiving EGFR-TKI treatment. Oncology.

99:32–40. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Takenaka M, Tanaka F, Kajiyama K, Manabe

T, Yoshimatsu K, Mori M, Kanayama M, Taira A, Kuwata T, Nawata A

and Kuroda K: Outcomes and pathologic response of primary lung

cancer treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor/immune checkpoint

inhibitor before salvage surgery. Surg Today. 54:1146–1153. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Elamin YY, Gomez DR, Antonoff MB,

Robichaux JP, Tran H, Shorter MK, Bohac JM, Negrao MV, Le X,

Rinsurogkawong W, et al: Local consolidation therapy (LCT) after

first line tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for patients with EGFR

mutant metastatic Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Clin Lung

Cancer. 20:43–47. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Deng R, Liu J, Song T, Xu T, Li Y, Duo L,

Xiang L, Yu X, Lei J and Cao F: Primary lesion radiotherapy during

first-line icotinib treatment in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with

multiple metastases and no brain metastases: A single-center

retrospective study. Strahlenther Onkol. 198:1082–1093. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chang SJ and Bristow RE: Evolution of

surgical treatment paradigms for advanced-stage ovarian cancer:

Redefining ‘optimal’ residual disease. Gynecol Oncol. 125:483–492.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Koole S, van Stein R, Sikorska K, Barton

D, Perrin L, Brennan D, Zivanovic O, Mosgaard BJ, Fagotti A and

Colombo PE: Primary cytoreductive surgery with or without

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for FIGO stage

III epithelial ovarian cancer: OVHIPEC-2, a phase III randomized

clinical trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 30:888–892. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lin MW, Yu SL, Hsu YC, Chen YM, Lee YH,

Hsiao YJ, Lin JW, Su TJ, Jeffrey Yang CF, Chiang XH, et al: Salvage

surgery for advanced lung adenocarcinoma after epidermal growth

factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Ann Thorac

Surg. 116:111–119. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Al-Halabi H, Sayegh K, Digamurthy SR,

Niemierko A, Piotrowska Z, Willers H and Sequist LV: Pattern of

failure analysis in metastatic EGFR-Mutant lung cancer treated with

tyrosine kinase inhibitors to identify candidates for consolidation

stereotactic body radiation therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 10:1601–1607.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wee P and Wang Z: Epidermal growth factor

receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel).

9:522017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Byrne NM, Tambe P and Coulter JA:

Radiation response in the tumour microenvironment: Predictive

biomarkers and future perspectives. J Pers Med. 11:532021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Won YW, Han JY, Lee GK, Park SY, Lim KY,

Yoon KA, Yun T, Kim HT and Lee JS: Comparison of clinical outcome

of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring epidermal

growth factor receptor exon 19 or exon 21 mutations. J Clin Pathol.

64:947–952. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Hong W, Wu Q, Zhang J and Zhou Y:

Prognostic value of EGFR 19-del and 21-L858R mutations in patients

with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 18:3887–3895.

2019.

|

|

50

|

Chen Y, Wang S, Zhang B, Zhao Y, Zhang L,

Hu M, Zhang W and Han B: Clinical factors affecting the response to

osimertinib in Non-Small cell lung cancer patients with an acquired

epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation: A Long-Term

survival analysis. Target Oncol. 15:337–345. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J,

Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, Dechaphunkul A, Imamura

F, Nogami N, Kurata T, et al: Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-Mutated

advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 378:113–125.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard

D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, Zhou C, Reungwetwattana T, Cheng Y,

Chewaskulyong B, et al: Overall survival with osimertinib in

untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 382:41–50.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|