Introduction

Skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) is a highly

aggressive malignancy with strong invasive potential and a markedly

high mortality rate (0.6% of all patients with stage-4 melanoma)

(1). It tends to progress rapidly,

frequently metastasizing to regional lymph nodes and distant

organs. The risk of recurrence is positively associated with the

clinical stage at diagnosis (1,2).

Research indicates that early-stage melanoma is often treatable

with radical surgical excision alone, without the need for adjuvant

therapy (3). However, in patients

with lymph node involvement, the recurrence rate remains high even

after complete resection. Notably, the 5-year survival rate for

patients with metastatic SKCM is only ~27% (2). Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms

underlying melanoma metastasis is essential for improving early

diagnosis, prognostic evaluation and the development of novel

targeted therapies. A recent comprehensive review highlighted the

evolving molecular subclasses of melanoma and emerging roles of

vitamin D signaling in tumor-immune crosstalk (4).

The skin functions as an integrated

neuro-immuno-endocrine organ that senses environmental cues and

coordinates systemic homeostasis (5). Ultraviolet radiation, beyond its

carcinogenic potential, modulates cutaneous vitamin D synthesis,

neuropeptide release and local immunoregulation, a concept termed

‘photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology’ (6). These layers of regulation provide

additional context for understanding melanoma biology.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most abundant internal modification

of eukaryotic mRNA, serves a pivotal role in regulating mRNA

stability, protein translation, viral infection and embryonic

development (7). This modification

is dynamically reversible and is orchestrated by three main classes

of regulators: ‘Writers’ [methyltransferases such as Vir like m6A

methyltransferase associated (VIRMA), methyltransferase m6A complex

catalytic subunit (METTL)3/14, RNA binding motif protein

(RBM)15/15B and Wilms tumor 1 associated protein (WTAP)], ‘erasers’

[demethylases including fat mass and obesity-associated protein

(FTO) and AlkB homolog 5, RNA demethylase (ALKBH5)] and ‘readers’

[m6A-binding proteins such as heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP)C, HNRNPA2B1, YTH m6A RNA binding protein

(YTHD)F1/2/3 and YTHDC1/2] (8).

Extensive research has reported that m6A modifications are involved

in a wide range of biological processes, including the heat shock

response, tissue development, DNA damage repair, and stem cell

self-renewal and differentiation (9–12).

Moreover, dysregulation of m6A regulators has been increasingly

implicated in tumor initiation, progression, metastasis and

resistance to therapy (13).

Aberrant m6A modification has been increasingly

recognized as a critical contributor to cancer initiation and

progression. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), for example, the m6A

methyltransferases METTL14 and METTL3 are markedly upregulated and

notably influence patient prognosis (14,15).

Similarly, the m6A demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 are overexpressed in

several tumor types, where they enhance cancer stemness and promote

oncogenic processes (16–18). In uveal melanoma and conjunctival

melanoma, m6A-mediated methylation of β-secretase 2 has been

reported to trigger intracellular calcium release, thereby

accelerating tumor progression (19). Moreover, Dahal et al

(20) reported that METTL3 is

markedly upregulated in melanoma and promotes cellular invasiveness

by upregulating MMP2 and N-cadherin expression. Despite growing

evidence supporting the role of m6A modifications in tumor

development and prognosis, the specific regulatory mechanisms by

which m6A influences metastasis and invasion in SKCM remain poorly

understood.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

uncover the molecular mechanisms by which m6A modification

contributes to SKCM metastasis and to provide a theoretical

foundation for the development of novel therapeutic targets and

prognostic biomarkers. To elucidate the potential role of m6A

modification in SKCM metastasis, the present study integrated

expression profiles from primary and metastatic SKCM samples in the

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to systematically identify

metastasis-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and

associated signaling pathways. A prognostic prediction model was

subsequently constructed using survival data from The Cancer Genome

Atlas (TCGA)-SKCM cohort. Key mRNAs strongly associated with both

m6A regulation and patient prognosis were further screened. In

addition, the present study explored their interactions within a

long noncoding (lnc)RNA-micro (mi)RNA-mRNA competing endogenous

(ce)RNA network and analyzed their correlation with immune cell

infiltration.

Materials and methods

Patients and data collection

Gene expression data for 46 metastatic SKCM samples,

77 primary SKCM samples and 21 normal skin samples were obtained

from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), specifically from

the GSE8401 (21), GSE15605

(22), GSE46517 (23) and GSE65904 (24) datasets. Raw data were

log-transformed and normalized prior to downstream analyses

(Fig. S1). A summary of patient

characteristics is presented in Tables

I and SI. Moreover, RNA

sequencing (RNA-seq) data from the TCGA-SKCM dataset were retrieved

from the University of California, Santa Cruz Xena platform

(https://xena.ucsc.edu/) and converted to

transcripts per million (TPM) using the ‘count2tpm’ R package

(version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/). Following quality control

and filtering for complete survival data, 461/472 patients in the

TCGA-SKCM dataset with matched RNA-seq and survival information

were included in the subsequent analyses.

| Table I.Sample information. |

Table I.

Sample information.

| Dataset | Total number of

samples | Sample type | Number of

samples |

|---|

| GSE8401 | 83 | Primary

melanoma | 31 |

|

|

| Metastatic

melanoma | 52 |

| GSE15605 | 74 | Primary

melanoma | 46 |

|

|

| Metastatic

melanoma | 12 |

|

|

| Normal skin

samples | 16 |

| GSE46517 | 104 | Primary

melanoma | 31 |

|

|

| Metastatic

melanoma | 73 |

| GSE65904 | 210 | Melanoma | 210 |

In addition, seven pairs of SKCM and adjacent normal

tissue samples were obtained from patients who underwent surgical

treatment at the Institute of Dermatology, Peking Union Medical

College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Nanjing, China)

between 2018 and 2021. A total of 7 patients, aged 26–92 years (4

males and 3 females) were included. All paraffin-embedded tissue

sections were confirmed as cutaneous melanoma by two or more

dermatopathologists, with cases declining to participate excluded.

The fresh tumor and adjacent tissues were promptly frozen and

stored at −80°C for subsequent analyses. The present study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Dermatology,

Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical

Sciences (approval no. 2017-KY-044), and all procedures were

performed in accordance with approved institutional guidelines.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Construction of a metastatic SKCM risk

prediction model and survival analysis

TCGA-SKCM cases were classified into primary and

metastatic groups based on patient clinical information. Least

absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression

analysis was performed using the ‘glmnet’ package in R (version

4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/), with the

optimal λ value determined using 10-fold cross-validation (25). This approach identified the most

predictive gene set, which, combined with primary-metastatic

status, was used to construct a risk score model. Individual risk

scores were calculated for each patient, who were then stratified

into high- and low-risk groups using the median risk score as the

cutoff. Survival differences between the two groups were assessed

using Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared using the log-rank test,

with significance defined as P<0.05. The predictive accuracy of

the risk model was evaluated by receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analysis, and model performance was quantified using

the area under the curve. Internal robustness was assessed using

10-fold cross-validation of the LASSO-Cox model. The resulting risk

scores for each fold and the coefficients selected at the λ_min and

λ_1se penalty parameters are summarized in Table SII. To address potential violations

of the proportional hazard rate assumption due to survival curve

crossover for certain genes, the analyzed time range was restricted

to periods preceding the crossover points. Survival analyses were

re-performed within these truncated time intervals to ensure

robustness of the log-rank test results (26).

Transcriptome sequencing data

bioinformatics analysis

Based on the risk scores generated by the machine

learning model, the TCGA-SKCM cohort was stratified into high- and

low-risk groups. Differential expression analyses were performed to

compare gene expression profiles among primary tumors, metastatic

tumors and normal tissues from the GEO datasets, as well as between

the high- and low-risk groups in the TCGA cohort. For the TCGA-SKCM

RNA-seq data, raw read-count matrices were analyzed using the

‘DESeq2’ package (R version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/) and the median-of-ratios

procedure was used to normalize library size and estimate

dispersion, followed by Wald tests to identify DEGs. Genes with

adjusted P<0.05 and |log2FoldChange (FC)|>1 were

deemed significant. TPM values, calculated using the count2tpm tool

(R version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/), were used only for

downstream visualization (27). For

the GEO datasets, raw or processed expression matrices were

analyzed using the ‘limma’ package (R version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/) with empirical Bayes

moderation to identify DEGs, applying the same adjusted P-value and

fold-change thresholds. DEGs identified from multiple GEO datasets

were then integrated using the ‘RobustRankAggreg’ (RRA) package (R

version 4.3.0; http://www.r–project.org/) (28) to obtain a robust DEG list.

For single-gene differential expression analyses,

thresholds were set at |log2FC|>1 and adjusted P<0.05 to

identify differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs associated with

each of the four candidate genes. Overlapping lncRNAs and mRNAs

were determined using the ‘VennDiagram’ package in R (version

4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/).

Visualization of DEGs was achieved using volcano plots and heatmaps

generated using the ‘ggplot2’ package (R version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/).

To assess the biological processes and signaling

pathways underlying SKCM metastasis, enrichment analyses were

performed on DEGs identified from GEO datasets comparing primary

and metastatic melanoma, and co-expressed DEGs associated with the

risk-related genes [keratin (KRT)17, plakophilin 1 (PKP1), cadherin

3 (CDH3) and cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2 (CRABP2)].

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed using the

Metascape database (http://metascape.org/) and the ‘clusterProfiler’ R

package (version 4.3.0; http://www.r–project.org/) (29). The top 20 enriched GO and KEGG terms

were visualized using network analysis in Cytoscape 3.6.1 (30). Additionally, gene set enrichment

analysis (GSEA) was performed using clusterProfiler, with

significance thresholds set at false discovery rate (FDR) <0.25

and adjusted P<0.05 (31).

Correlation analysis of m6A-regulators

with metastatic SKCM-associated genes

Based on previous studies (32), 21 key m6A regulatory genes [FTO,

ALKBH5, RBM15, RBM15B, METTL3, METTL14, METTL16, WTAP, VIRMA, zinc

finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13), HNRNPC, HNRNPA2B1, insulin

like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein (IGF2BP)1, IGF2BP2,

IGF2BP3, RBMX, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, YTHDF1, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3] were

selected to assess the potential association between m6A

methylation regulation and metastatic SKCM. Pearson correlation

analysis was performed to assess the relationships between the

expression levels of these m6A regulators and key genes, with

|R|>0.2 and P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Establishment of an m6A-regulated

metastatic SKCM-associated ceRNA network

Potential miRNAs targeting key mRNAs were predicted

using the miRWalk database (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/). Concurrently,

lncRNA-miRNA interactions were identified using the TarBase v8

database (http://carolina.imis.athena-innovation.gr/diana_tools/web/index.php?r=lncbasev2%2Findex).

Common miRNAs predicted by both approaches were determined using

Venn diagram analysis using the VennDiagram R package. A

lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA network was subsequently constructed and

visualized using Cytoscape (v3.6.1; http://cytoscape.org/release_notes_3_6_1.html). Key

regulatory nodes within the network were identified using the

‘cytoHubba’ plugin. To further characterize the lncRNAs, sequences

were retrieved from LNCipedia (https://lncipedia.org/), and their subcellular

localizations were predicted using lncLocator (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/lncLocator/).

The subcellular localization of mRNAs was determined using the

DM3Loc web tool (http://dm3loc.lin-group.cn/). Potential miRNA binding

sites within genomic sequences were identified using miRanda

(https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/local_miranda_miRNA_target_prediction_120)

(33). Only lncRNAs and mRNAs

predicted to localize mainly in the cytoplasm (lncLocator or DM3Loc

probability ≥0.6) were retained, ensuring structural plausibility

for ceRNA crosstalk.

Relationships between the level of

immune cell infiltration and the expression of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3

and CRABP2

Relative enrichment scores for 24 immune subsets

were calculated from log2(TPM+1) matrices with the GSVA

package (v1.34.0; method=‘ssgsea’, kcdf=‘Gaussian’) (34,35).

Absolute cell fractions were inferred using CIBERSORTx (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/index.php) in

‘absolute mode’ with the LM22 signature and 1,000 permutations;

samples with P≥0.05 were discarded. Deconvolution was repeated

using the EPIC algorithm implemented in TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/TIMER2.0) to provide an

additional independent estimate. To evaluate the immune and stromal

components of the tumor microenvironment, the Estimation of STromal

and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data

(ESTIMATE) algorithm was applied using the ‘estimate’ R package

(version 4.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/). Immune scores, stromal

scores and tumor purity were calculated for each sample according

to the original algorithm. These packages were used to assess the

correlation between the expression of m6A-associated genes (KRT17,

PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2) and the infiltration levels of 24 immune

cell types. Pearson correlation analysis was applied, with

|R|>0.2 and P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Immunohistochemical staining of

patient tumor tissues

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin

at 4°C overnight, followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning at

a 4–5 µm thickness. Sections were sequentially deparaffinized in

xylene, dehydrated and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series,

and finally immersed in distilled water. Subsequently, 10% goat

serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was applied to the

sections and incubated at room temperature for 1 h to complete

blocking. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies against PKP1 (1:500; cat. no. ab154622; Abcam),

KRT17 (1:200; cat. no. ab109725; Abcam), CRABP2 (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab211927; Abcam) and CDH3 (1:250; cat. no. ab242060; Abcam). After

washing, the slides were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary

antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. ab6759; Abcam) in a humidified chamber

for 30 min, followed by color development using a DAB detection kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). A total of two independent

pathologists evaluated the stained sections under an optical

microscope (Olympus Corporation). The proportion of positively

stained cells was scored as follows: 0, 0–5%; 1, 6–25%; 2, 26–50%;

3, 51–75%; and 4, >75%. Staining intensity was graded as

follows: 0, negative; 1, light yellow; 2, yellow-to-brown; and 3,

brown. The final immunohistochemical score was calculated as the

product of the proportion and intensity scores, and classified into

four categories: Negative (−; 0), weakly positive (+; 1–4),

moderately positive (++; 5–8) and strongly positive (+++;

9–12).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from SKCM and matched

adjacent normal tissues using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen™; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA synthesis was performed using the

EVO M-MLV RT Mix Kit [cat. no. AG11728; Accurate Biotechnology

(Hunan) Co., Ltd.] according to the manufacturer's instructions.

qPCR was then performed using the SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR

Kit [cat. no. AG11701; Accurate Biotechnology (Hunan) Co., Ltd.] on

a LightCycler® 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche

Diagnostics). Each 10 µl reaction mixture contained 1 µl cDNA, 5 µl

2X SYBR Green Pro Taq HS Premix, 0.5 µM of each primer and

nuclease-free water. The qPCR cycling conditions were as follows:

Initial denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles at

94°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 50°C for 30 sec. Relative gene

expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (36). The primer sequences

used in the present study are listed in Table II.

| Table II.Primers used in the reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR assay. |

Table II.

Primers used in the reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR assay.

|

|

|

| Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gene | Species | Amplicon length,

bp | Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| KRT17 | Human | 119 |

GGTGGGTGGTGAGATCAATGT |

CGGCATCCTTGCGGTTCTT |

| PKP1 | Human | 120 |

TCAGCAACAAGAGCGACAAG |

TCAGGTAGGTGCGGATGG |

| CDH3 | Human | 121 |

TGGAGATCCTTGATGCCAATGA |

GCGTCCAGATCAGTGACCG |

| CRABP2 | Human | 99 |

TGAATGTGATGCTGAGGAAGAT |

TGGTGGAGGTTTTGATGTAGAA |

| β-actin | Human | 73 |

GTGGCCGAGGACTTTGATTG |

CCTGTAACAACGCATCTCATATT |

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses, except those involving

transcriptomic sequencing data, were performed using GraphPad Prism

(version 8.0; Dotmatics) and SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM

Corp.). For comparisons of immunohistochemistry scores between

tumor and adjacent normal tissues, non-parametric tests were

applied: The Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons or the

Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple groups, followed by Dunn's post

hoc test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple

comparisons. For comparisons among more than two groups with

normally distributed data, one-way ANOVA was used, followed by

Tukey's post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons. RT-qPCR

data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare

expression levels between tumor and matched normal tissues. Unless

otherwise specified, P-values were adjusted for multiple

comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false-discovery-rate (FDR)

procedure. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Comprehensive bioinformatics

identification of SKCM during metastasis

To identify key genes associated with SKCM

metastasis, a comprehensive analysis of multiple GEO datasets was

performed. Prior to analysis, gene expression data were normalized

(Fig. S1), and the ‘limma’ package

in R was used to identify DEGs within each microarray dataset,

using adjusted P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1 as cutoff

criteria (Fig. S2). Subsequently,

DEGs from all datasets were integrated using the RRA package,

resulting in the identification of 94 consistently differentially

expressed mRNAs, 84 upregulated and 10 downregulated, in metastatic

SKCM samples compared with in primary SKCM samples across the four

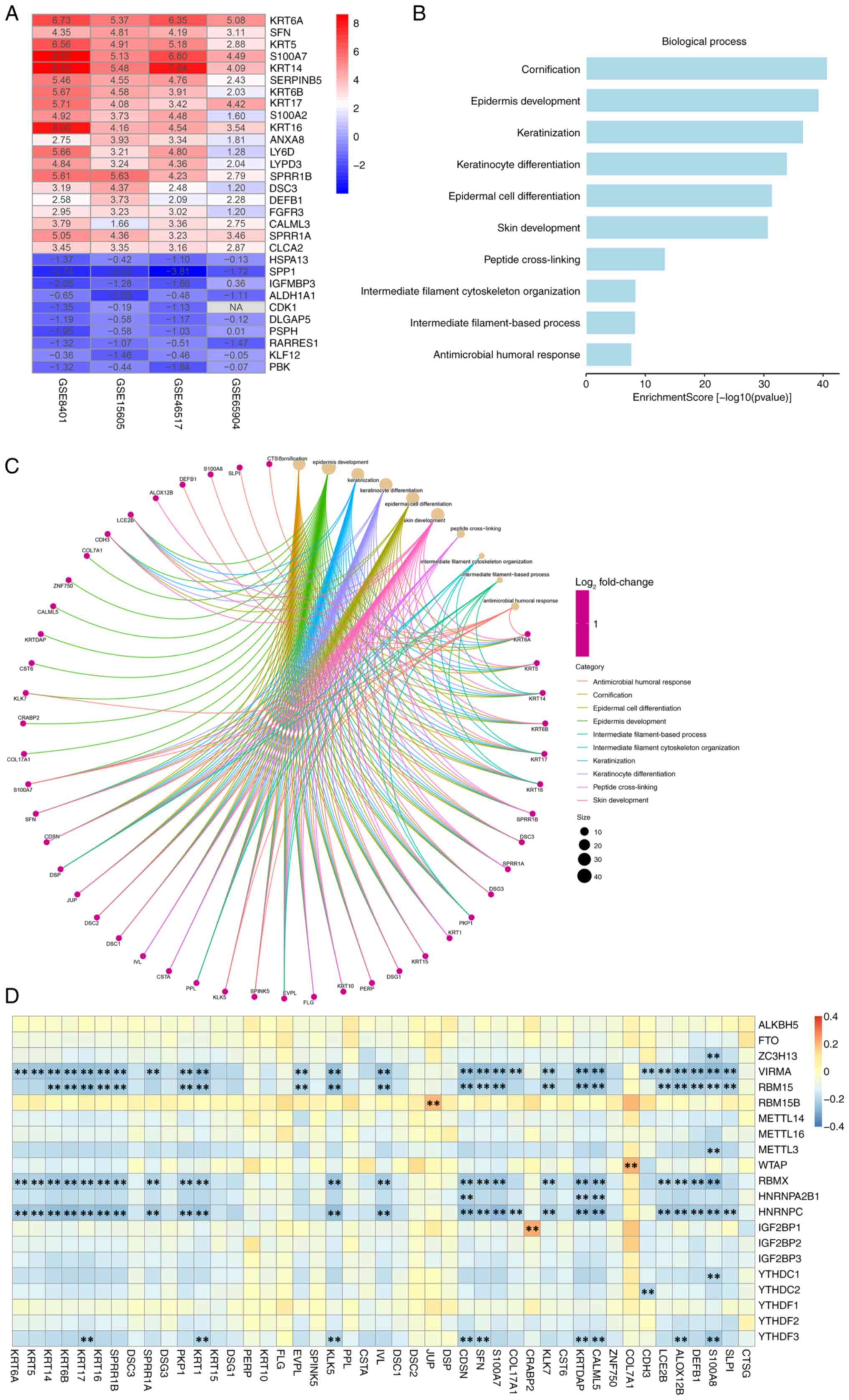

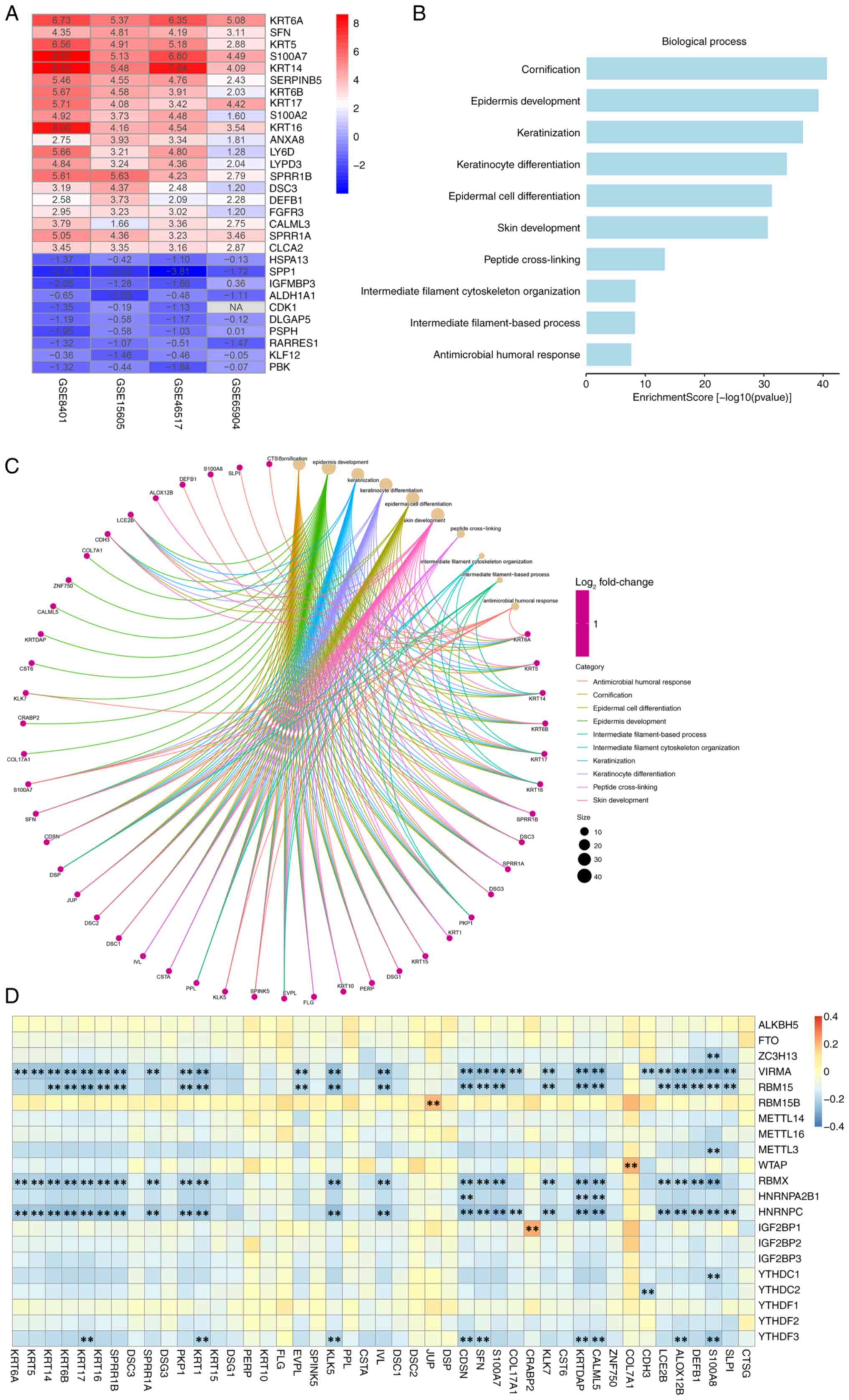

datasets (Fig. 1A).

| Figure 1.Critical SKCM metastasis-related

genes and signaling pathways in the GEO SKCM cohort. (A)

Identification of DEGs in 4 GEO datasets using the RobustRankAggreg

package. A heatmap of the top 20 upregulated and 10 downregulated

DEGs in the integrated GEO datasets analysis is presented: The rows

represent the genes, and the columns represent the GEO dataset.

Each cell contains the log2FoldChange value. Red

represents upregulated genes and blue represents downregulated

genes. GO analysis based on DEGs between metastatic and primary

SKCM. (B) GO enrichment analysis was performed using the

clusterProfiler package to evaluate the related biological

processes. (C) The line color of the ring graph represents the GO

terms, the points represent the genes and the size of the points

represents the count number. (D) Heatmap illustrating Pearson

correlation coefficients between metastasis-associated genes and

N6-methyladenosine regulators in SKCM, with color intensity

indicating the correlation coefficient (blue, negative; yellow,

neutral; and orange/red, positive). **P<0.01. SKCM, skin

cutaneous melanoma; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; DEGs,

differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology. |

Subsequently, GO biological process enrichment

analysis was performed using the ‘clusterProfiler’ package in R.

The results indicated that pathways related to cornification,

epidermis development, and keratinization were significantly

enriched, suggesting their critical involvement in SKCM metastasis.

Notably, genes such as cathepsin G (CTSG), serine peptidase

inhibitor kazal type 1 and S100 calcium binding protein A8 (S100A8)

were identified as key contributors within these pathways (Fig. 1B and C).

In addition, the correlations between the 94

metastasis-related DEGs and 21 m6A regulatory genes were evaluated

using Pearson correlation analysis, with thresholds set at

|R|>0.5 and P<0.05. DEGs whose expression levels were

significantly correlated with ≥1 m6A regulator were defined as

m6A-related mRNAs. Based on this criterion, a total of 45 mRNAs

were identified that showed significant correlations with m6A

(Fig. 1D).

m6A regulatory-related genes in SKCM

in the TCGA dataset

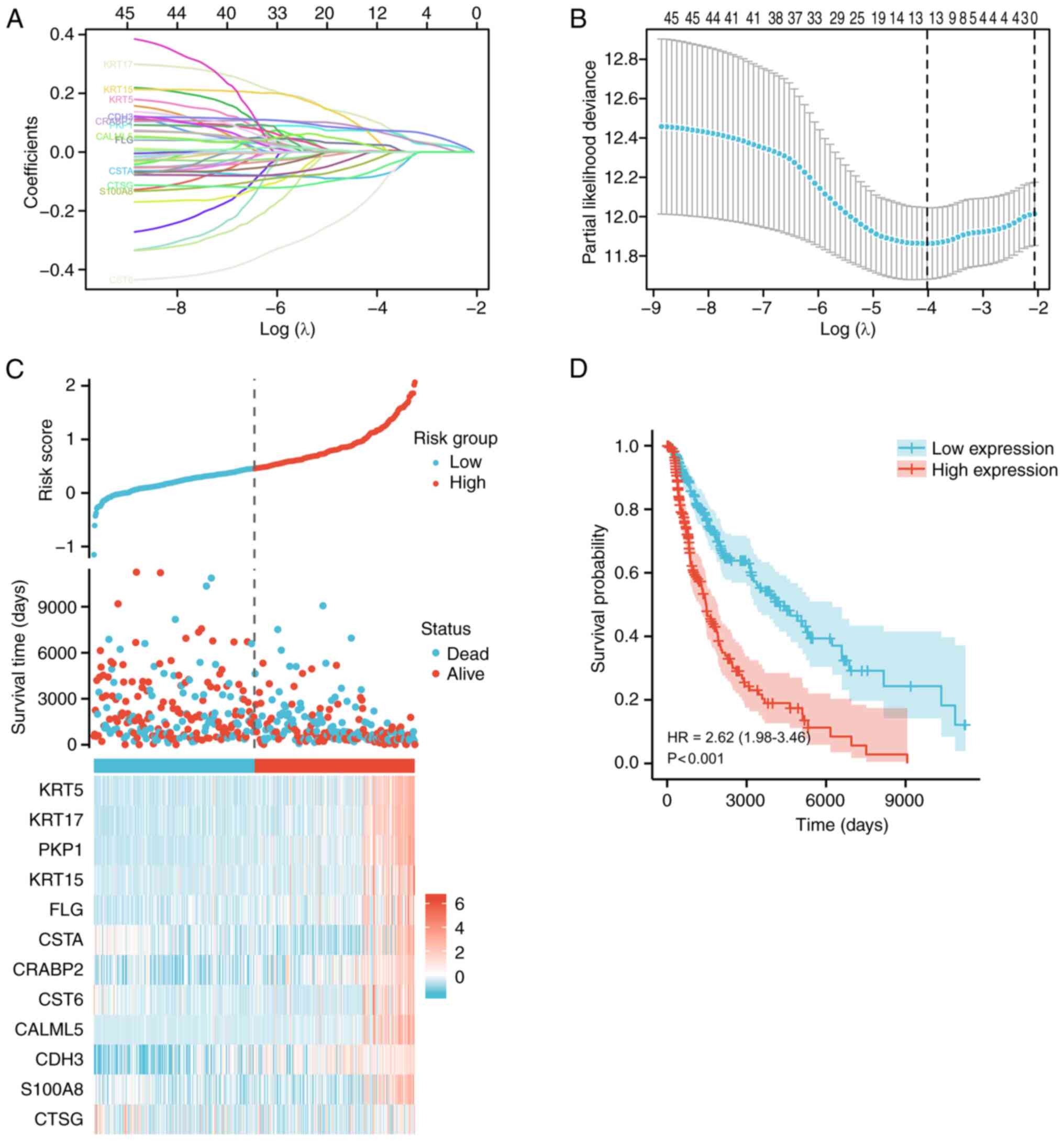

A LASSO-Cox analysis of the upregulated pathways and

related genes involved in SKCM metastasis was subsequently

performed. The partial likelihood deviance in relation to log(λ)

was derived from the LASSO-Cox regression model (Fig. 2A and B). Using the TCGA

transcriptomic data and survival information, 12 SKCM metastasis

regulators associated with overall survival (OS) were identified:

KRT5, KRT17, PKP1, KRT15, filaggrin (FLG), cystatin A (CSTA),

CRABP2, cystatin E/M (CST6), calmodulin like (CALML)5, CDH3, S100A8

and CTSG. The risk score and survival status distribution indicated

that patient survival time decreased with an elevated risk score.

Moreover, combined with the gene expression distribution, higher

expression of these genes correlated with a higher risk score

(Fig. 2C). Furthermore, survival

analysis revealed that patients in the high-risk group exhibited

significantly worse long-term survival than those in the low-risk

group [hazard ratio (HR), 2.62; P<0.001; Fig. 2D]. Ultimately, the present study

focused on four mRNAs strongly related to m6A regulation (CDH3,

KRT17, PKP1 and CRABP2). These genes appear to serve crucial roles

in SKCM metastasis.

Construction and prognostic analysis

of the ceRNA network

According to previous studies, mRNA expression is

modulated by miRNAs, whilst lncRNAs can competitively bind miRNAs

and thus indirectly regulate mRNA expression. This

lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA triple regulatory network is known as a ceRNA

network (37). To clarify the

regulation of metastasis-related mRNAs in SKCM by lncRNAs via

miRNAs, the present study constructed a ceRNA network centered on

CDH3, KRT17, PKP1 and CRABP2. First, single-gene differential

expression analysis was performed for each of the four genes in the

TCGA-SKCM cohort, identifying significantly co-expressed or

differentially up or downregulated transcripts, and for common

differentially expressed mRNAs and lncRNAs (Fig. S3). Ultimately, 494 differentially

expressed mRNAs and 91 differentially expressed lncRNAs were

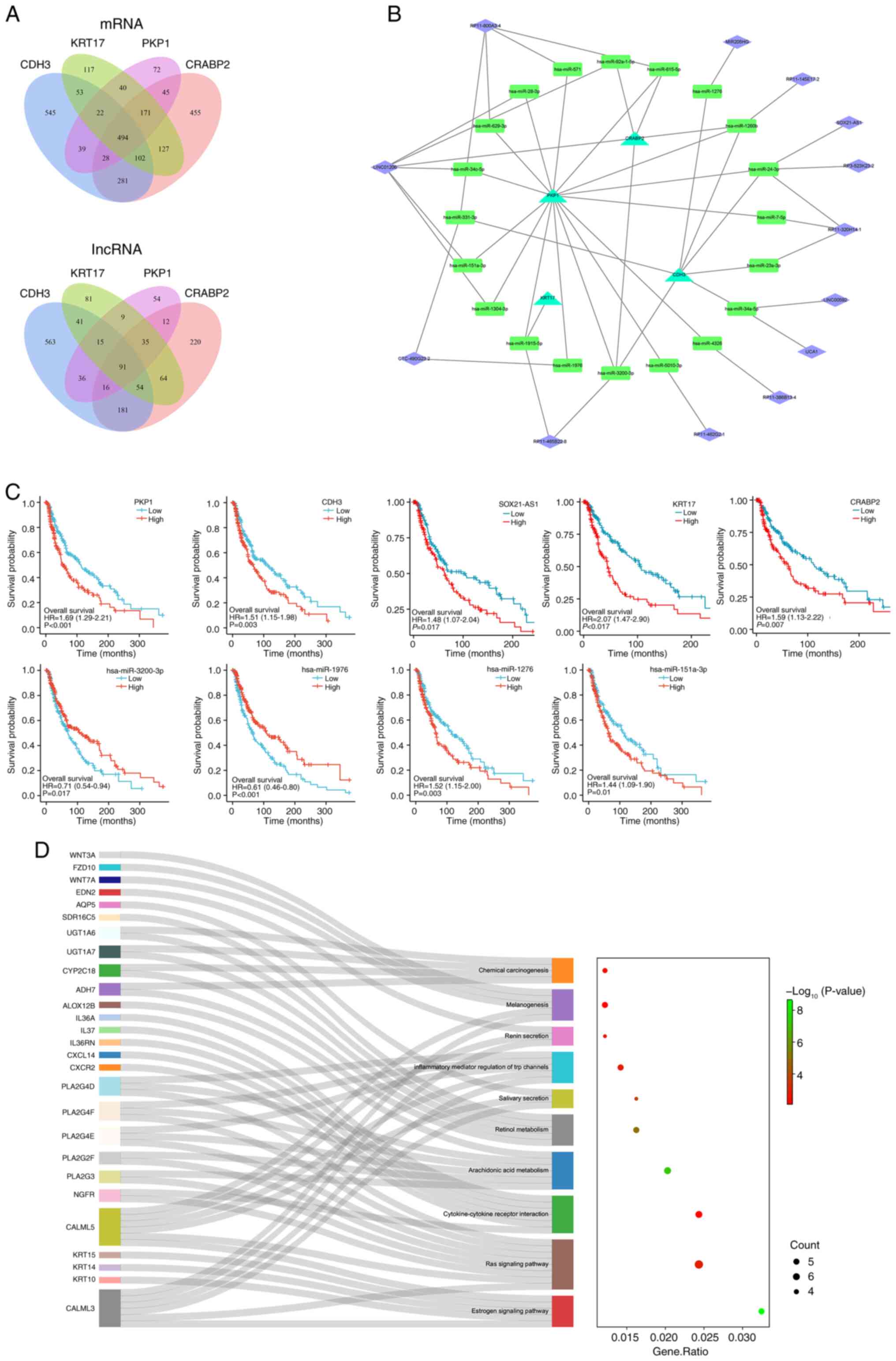

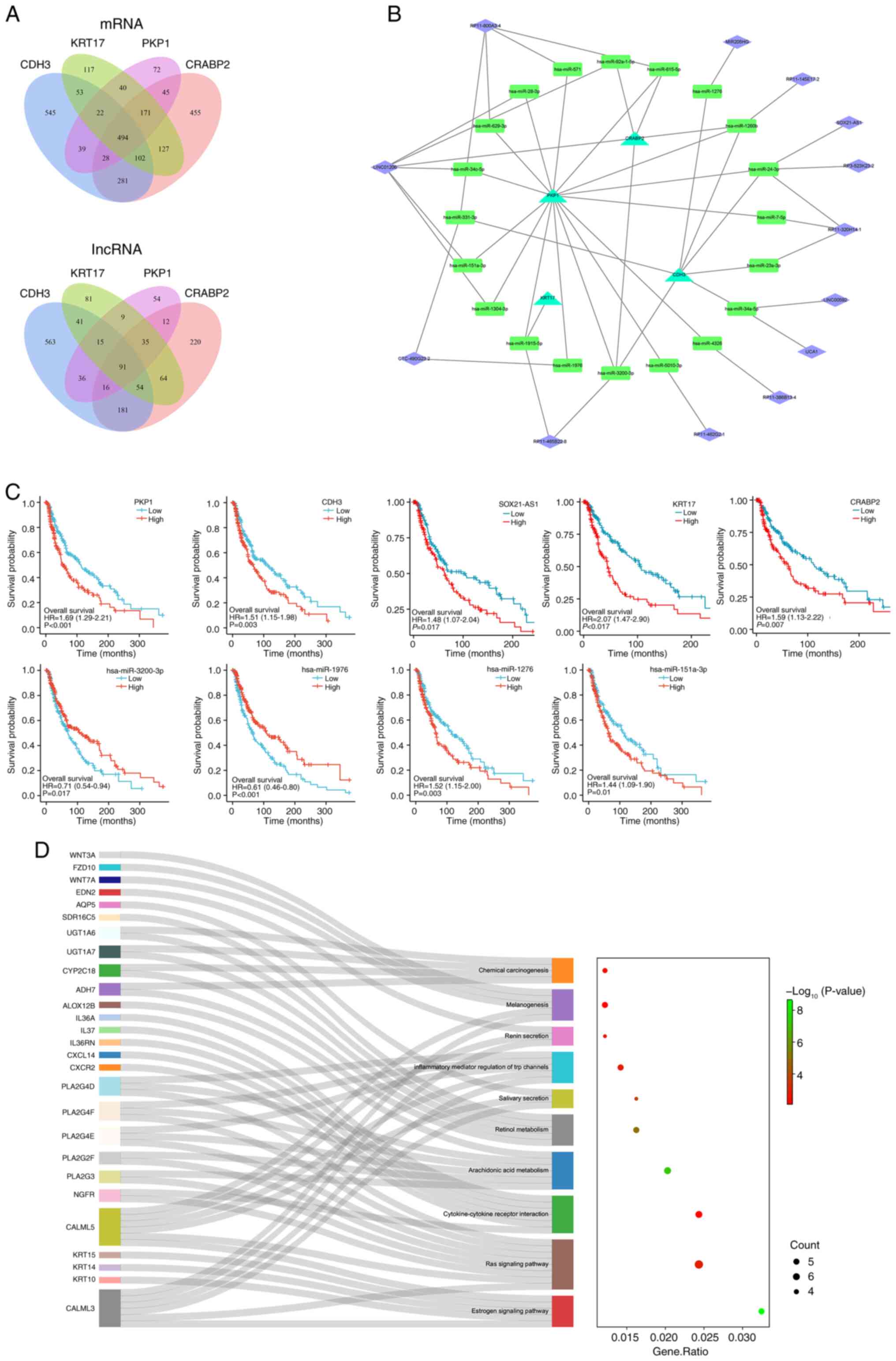

identified (Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3.Construction, prognosis analysis and

enrichment analysis of the ceRNA network. (A) Venn diagram of the

co-expressed differential mRNAs and lncRNAs of CDH3, KRT17, PKP1

and CRABP2 in SKCM. (B) Global view of the ceRNA network, which

consists of 13 lncRNAs, 20 miRNAs and 4 mRNAs. Triangles,

rectangles and diamonds represent mRNAs, miRNAs and lncRNAs,

respectively. (C) Prognostic analysis of the ceRNA network

expression level in SKCM assessed using the Kaplan-Meier plotter.

KRT17, PKP1, CDH3, CRABP2, SOX21-AS1, hsa-miR-1276 and

hsa-miR-151a-3p were demonstrated to be risk factors for SKCM,

whilst hsa-miR-3200-3p, hsa-miR-1976 were protective factors for

SKCM. (D) Functional enrichment analyses of co-expressed

differential mRNAs of CDH3, KRT17, PKP1 and CRABP2 in SKCM. The

Sankey diagram shows the pathways in which the co-expressed

differential mRNAs were mainly enriched. The bubble pattern

demonstrates the top 10 enrichment pathways with Entities ratio and

Entities count. The y-axis represents the pathway and the x-axis

represents the rich factor. The size and color of each bubble

represent the number of differentially expressed genes enriched in

the pathway and the -log10(P-value), respectively.

ceRNA, competing endogenous RNA; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; KRT17,

keratin 17; PKP1, plakophilin 1; CDH3, cadherin 3; CRABP2, cellular

retinoic acid binding protein 2; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma;

miRNA/miR, microRNA. |

Subsequently, miRNAs predicted to target the 91

lncRNAs (TarBase) and the 4 mRNAs (miRWalk) were screened,

identifying the shared miRNA interactions between lncRNAs and

mRNAs. Consequently, 13 lncRNAs, 20 miRNAs and 4 mRNAs were

integrated into the ceRNA network (Fig.

3B). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3, CRABP2, SOX21-AS1, hsa-miR-3200-3p, hsa-miR-1976,

hsa-miR-1276 and hsa-miR-151a-3p were all significantly associated

with OS in SKCM. HR analysis also demonstrated that KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3, CRABP2, SOX21-AS1, hsa-miR-1276 and hsa-miR-151a-3p are risk

factors for SKCM, whereas hsa-miR-3200-3p and hsa-miR-1976 serve as

protective factors (Fig. 3C).

Additionally, co-expressed differentially expressed

mRNAs associated with KRT17, PKP1, CDH3, and CRABP2 were subjected

to functional enrichment analysis using the Metascape online tool.

The results revealed that these genes are closely associated with

the estrogen signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway,

cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, melanogenesis and chemical

carcinogenesis, with the CALML3/5 and phospholipase A2 group IVA

families serving important roles in these pathways (Fig. 3D).

Association between m6A regulators and

the development and progression of SKCM

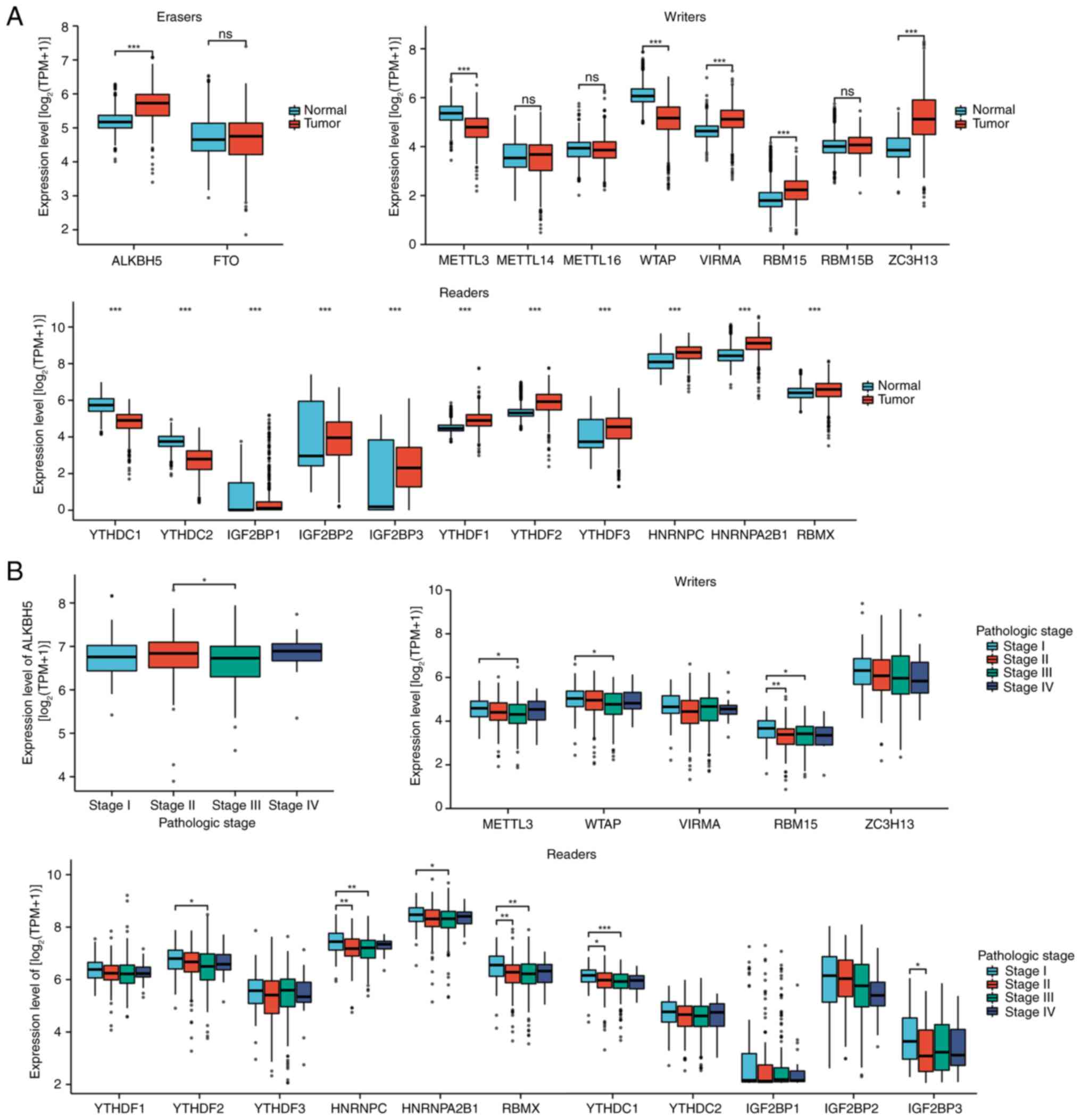

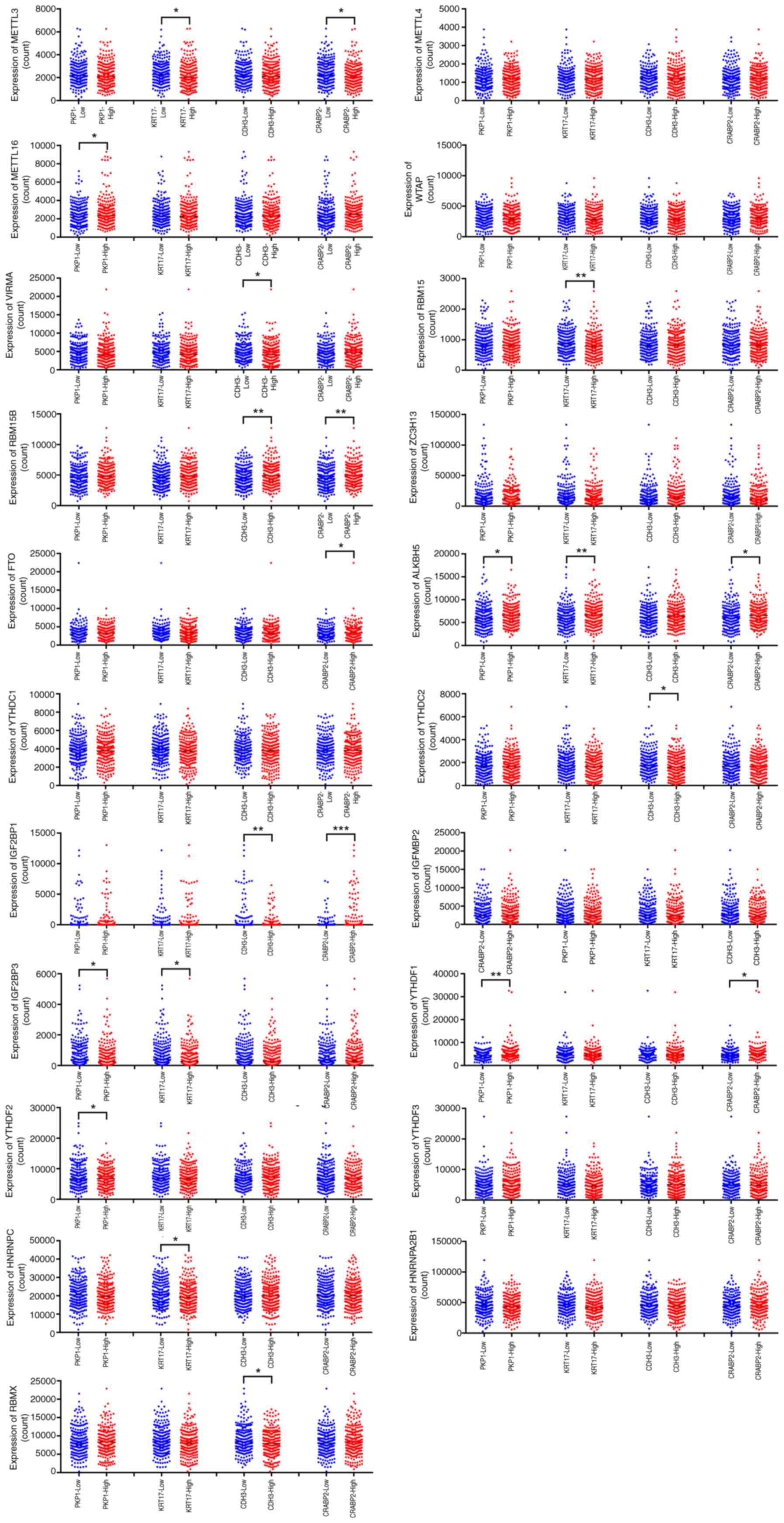

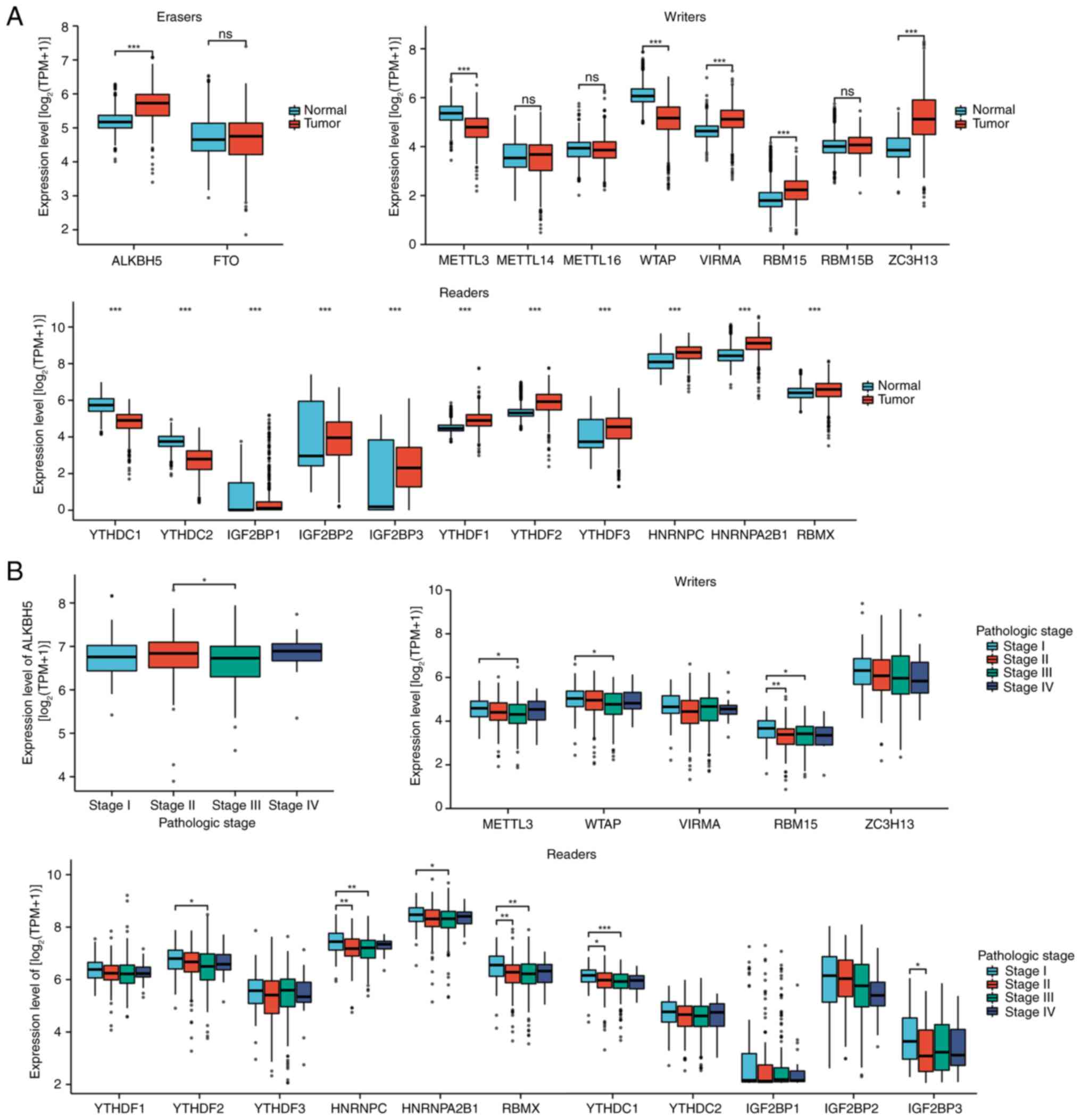

To further elucidate the abnormal m6A regulatory

mechanisms in SKCM, the expression of 21 m6A regulators in SKCM and

normal tissues from TCGA were analyzed. A total of four

downregulated regulators (METTL3, WTAP, YTHDC1 and YTHDC2) and 13

upregulated regulators (ALKBH5, VIRMA, RBM15, ZC3H13, IGF2BP1,

IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, HNRNPC, HNRNPA2B1 and

RBMX) were identified in SKCM (Fig.

4A). The present study also evaluated how these 21 m6A

regulators vary across different clinical stages (I–IV), and the

ANOVA results revealed that ALKBH5, METTL3, WTAP, RBM15, YTHDF2,

HNRNPC, HNRNPA2B1, RBMX, YTHDC1 and IGF2BP3 displayed continuous

patterns of increased or decreased mRNA expression with advancing

SKCM stage (Fig. 4B). This suggests

that certain m6A regulators may be closely associated with SKCM

tumorigenesis and progression.

| Figure 4.Association of m6A regulators with

the development and progression of SKCM. (A) Compared with normal

samples, four downregulated (METTL3, WTAP, YTHDC1 and YTHDC2) and

13 upregulated regulators (ALKBH5, VIRMA, RBM15, ZC3H13, IGF2BP1,

IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, HNRNPC, HNRNPA2B1 and

RBMX) were identified in tumor samples. (B) ALKBH5, METTL3, WTAP,

RBM15, YTHDF2, HNRNPC, HNRNPA2B1, RBMX, YTHDC1 and IGF2BP3

exhibited consistently higher or lower mRNA levels as SKCM clinical

staging progressed. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. m6A,

N6-methyladenosine; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; METTL,

methyltransferase, m6A complex catalytic subunit; WTAP, Wilms'

tumor associated protein; YTHD, YTH m6A RNA binding protein;

ALKBH5, AlkB homolog 5, RNA demethylase; VIRMA, Vir Like m6A

methyltransferase associated; RBM, RNA binding motif protein;

ZC3H13, zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13; IGF2BP, insulin like

growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein; HNRNP heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein; ns, not significant; TPM, transcripts per

million. |

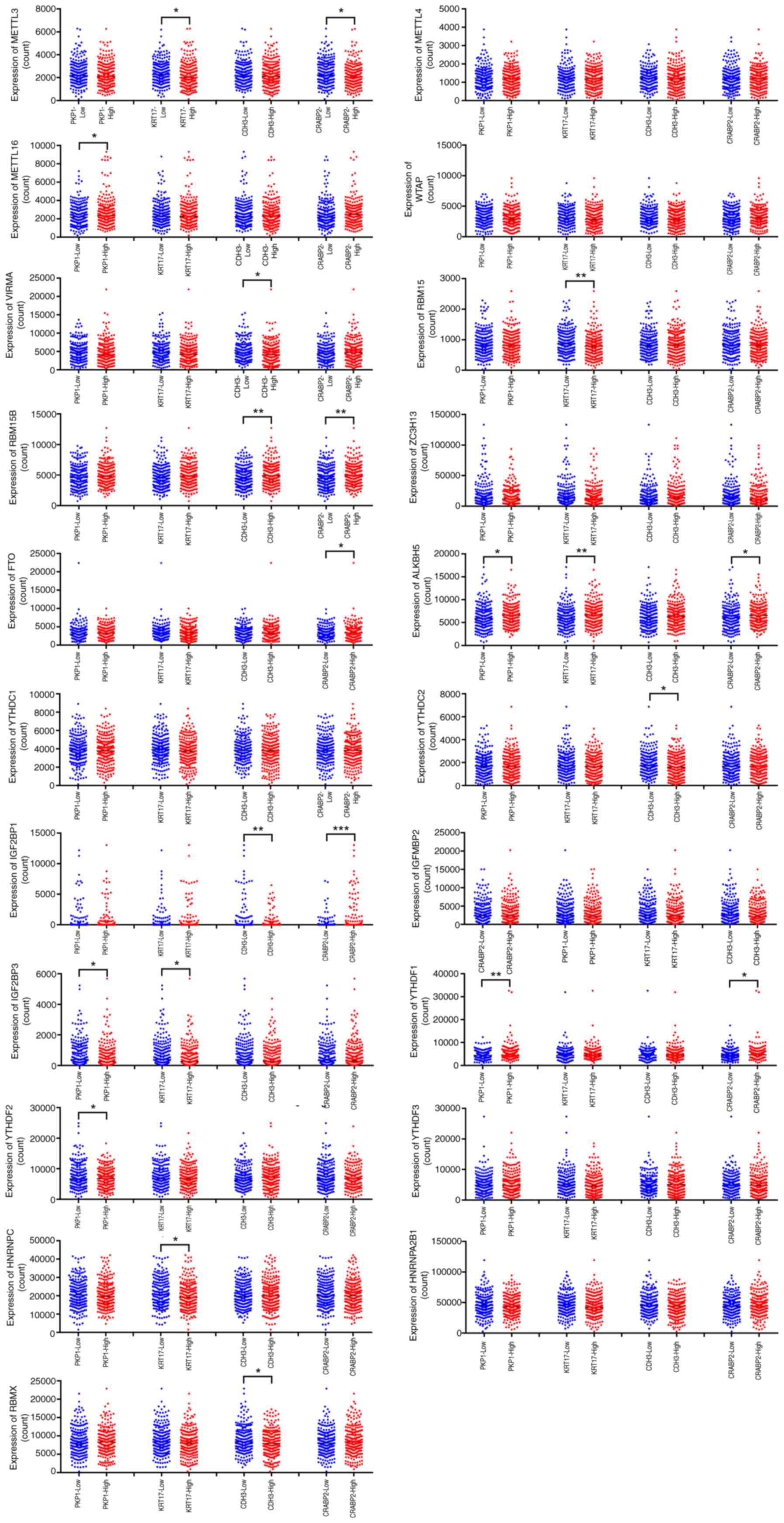

Association between m6A regulators and

the expression levels of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 in SKCM

The associations between the four key metastatic

prognostic mRNAs (KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2) and the

aforementioned 21 m6A regulators were subsequently assessed. The

results showed that the expression level of KRT17 was significantly

associated with METTL3, RBM15, ALKBH5, IGF2BP3 and HNRNPC. The

expression level of PKP1 was significantly associated with METTL16,

ALKBH5, IGF2BP3, YTHDF1 and YTHDF2. The expression level of CDH3

was significantly associated with VIRMA, RBM15B, YTHDC2, IGF2BP1

and RBMX, whereas the expression level of CRABP2 was significantly

associated with METTL3, RBM15B, FTO, ALKBH5, IGF2BP1 and YTHDF1

(Fig. 5).

| Figure 5.Association between m6A regulators

with the expression levels of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 in SKCM.

The expression level of KRT17 was associated with METTL3, RBM15,

ALKBH5, IGF2BP3 and HNRNPC; the expression level of PKP1 was

associated with METTL16, ALKBH5, IGF2BP3, YTHDF1 and YTHDF2; the

expression level of CDH3 was associated with VIRMA, RBM15B, YTHDC2,

IGF2BP1 and RBMX; the expression level of CRABP2 was associated

with METTL3, RBM15B, FTO, ALKBH5, IGF2BP1 and YTHDF1. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. m6A, N6-methyladenosine; KRT17, keratin

17; PKP1, plakophilin 1; CDH3, cadherin 3; CRABP2, cellular

retinoic acid binding protein 2; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma;

METTL, methyltransferase, m6A complex catalytic subunit; WTAP,

Wilms' tumor associated protein; VIRMA, Vir Like m6A

methyltransferase associated; RBM, RNA binding motif protein;

ZC3H13, zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13; FTO, fat mass and

obesity-associated protein; ALKBH5, AlkB homolog 5, RNA

demethylase; YTHD, YTH m6A RNA binding protein; IGF2BP, insulin

like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein; HNRNP heterogeneous

nuclear ribonucleoprotein. |

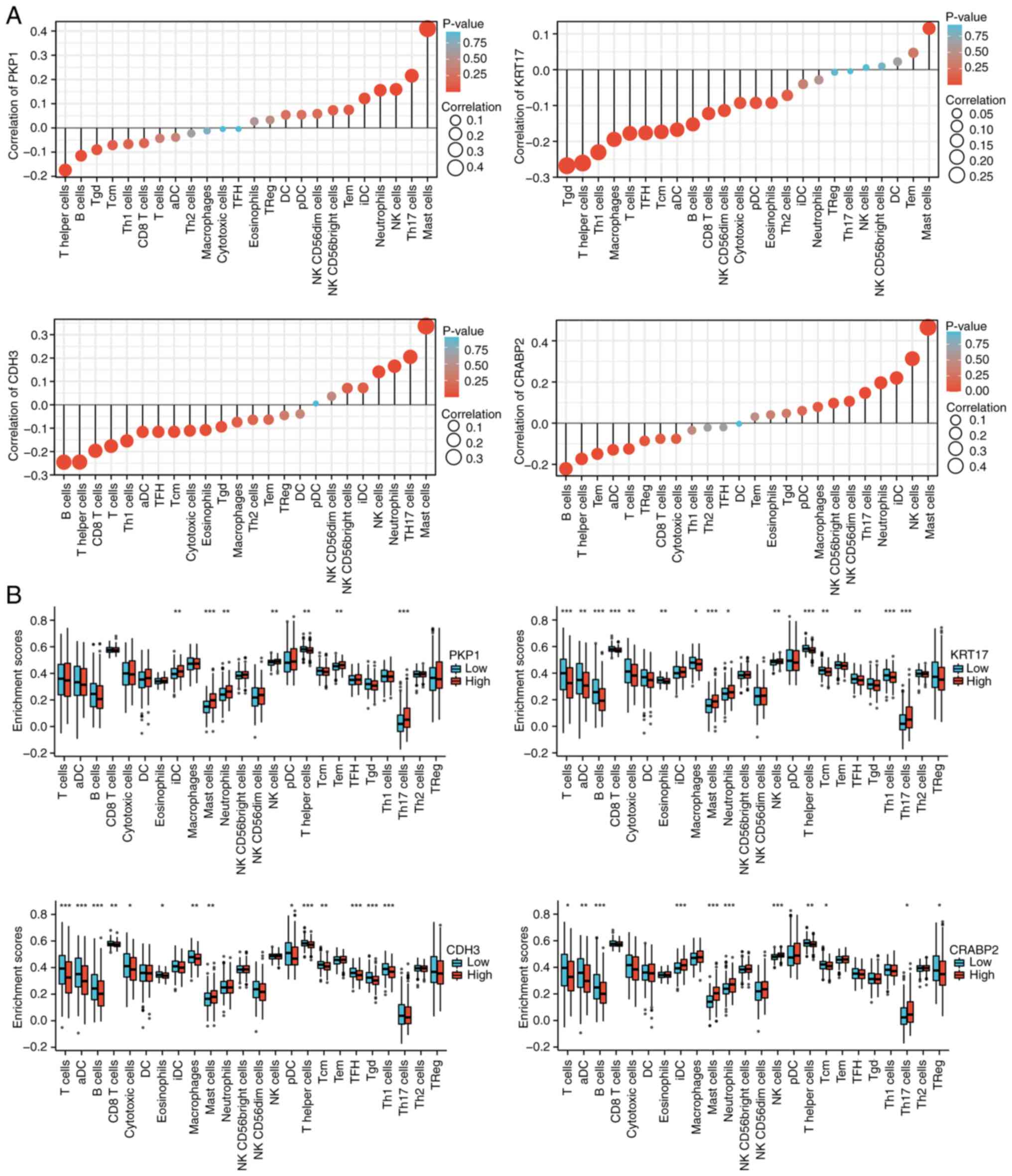

Immune landscape associated with

KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 expression in SKCM

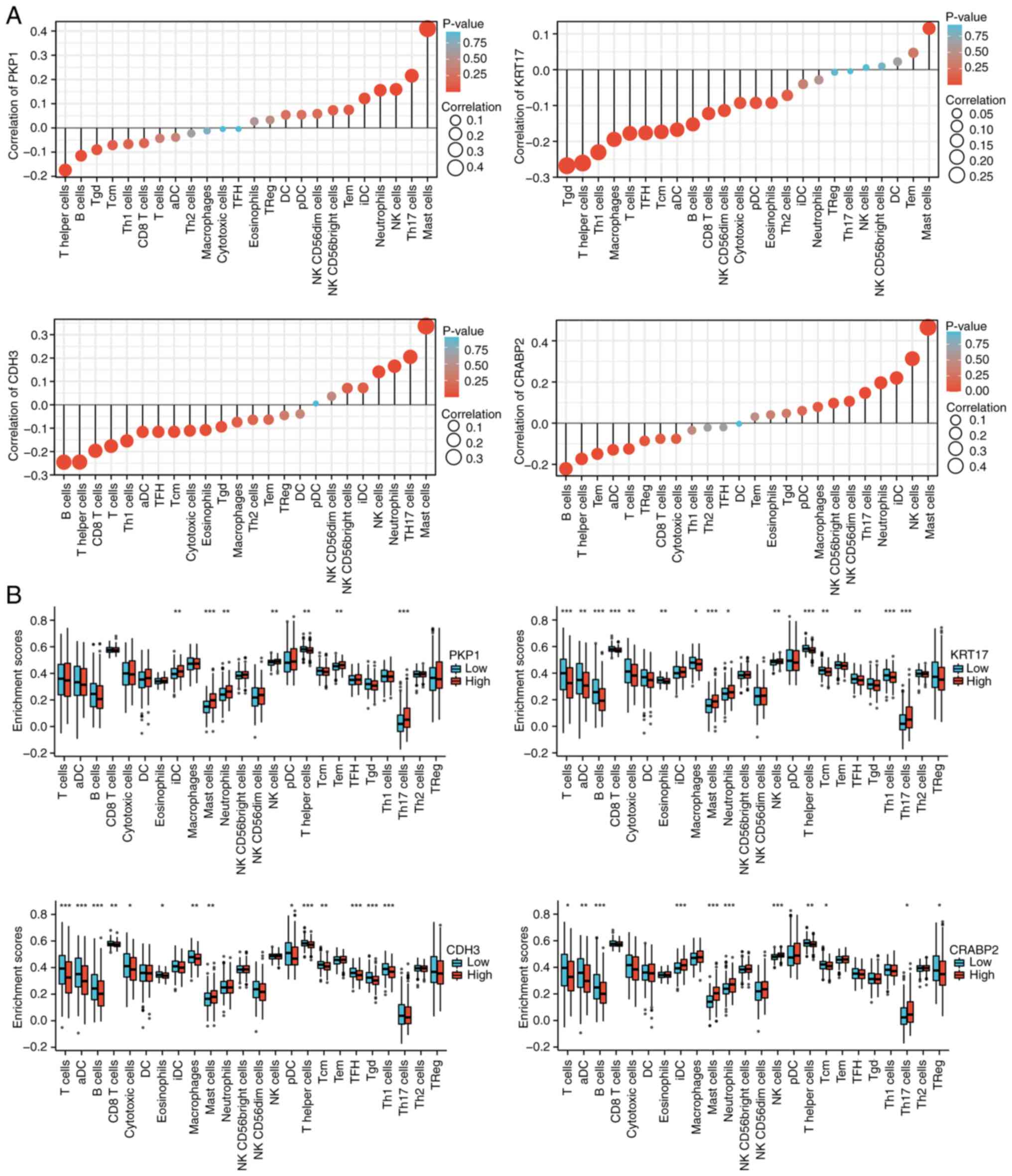

To thoroughly assess the influence of KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3 and CRABP2 expression on immune cell infiltration, we used

single-sample (ss)GSEA to assess correlations between these genes

and 24 tumor-infiltrating immune cell types in 472 SKCM samples.

The results indicated that PKP1 is positively correlated with mast

cells and Th17 cells (Pearson-value >0.2; P<0.05; (Fig. 6A and B); KRT17 is negatively

correlated with Tγδ (Tgd) cells, T helper cells (Th cells), and Th1

cells (Pearson-value <-0.2; P<0.05); CDH3 is positively

correlated with mast cells and Th17 cells but negatively correlated

with B cells and T helper cells; and CRABP2 is positively

correlated with mast cells, natural killer (NK) cells, immature

dendritic cells and neutrophils, and negatively correlated with B

cells (Fig. 6A and B). To

corroborate the ssGSEA-derived landscape, the immune infiltration

data was re-evaluated using ESTIMATE and CIBERSORTx. The results

revealed that tumors with a high expression of PKP1, KRT17, CRABP2

or CDH3 displayed significantly lower StromalScore, ImmuneScore and

composite ESTIMATEScore than their low-expression counterparts (all

FDR <0.01; Fig. S4), mirroring

the global immune-suppressed phenotype observed with ssGSEA.

Consistent with the ssGSEA results, CIBERSORTx deconvolution

analysis further characterized the tumor immune microenvironment.

Specifically, high CRABP2 expression was associated with

significantly reduced levels of CD8+ T cells (Figs. 6B and S4). By contrast, both high-PKP1 and

high-CRABP2 tumors showed increased levels of NK cells (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, both tumor subtypes

shared a common feature of an increased M0-to-M2 macrophage

fraction (all FDR <0.05; Fig.

S4). The concordant results from the three independent

algorithms strengthen the conclusion that elevated expression of

these keratin-related genes is associated with an immunologically

‘cold’ microenvironment in melanoma.

| Figure 6.Immune landscape of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3

and CRABP2 expression levels in SKCM. (A) Correlations of 24 immune

cells with KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 expression levels,

respectively. The size of the dots represents the absolute

Pearson's correlation coefficient values. (B). Enrichment

differences of 24 immune cell types between high- and

low-expression groups of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. KRT17, keratin 17; PKP1, plakophilin 1;

CDH3, cadherin 3; CRABP2, cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2;

SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; NK, natural killer; DC, dendritic

cell; aDC, activated DC; TFH, follicular helper T cells; Tcm,

central memory T cells; Tgd, γδ T cells; Tem, effector memory T

cells; pDC, plasmacytoid DC; iDC, immature DC. |

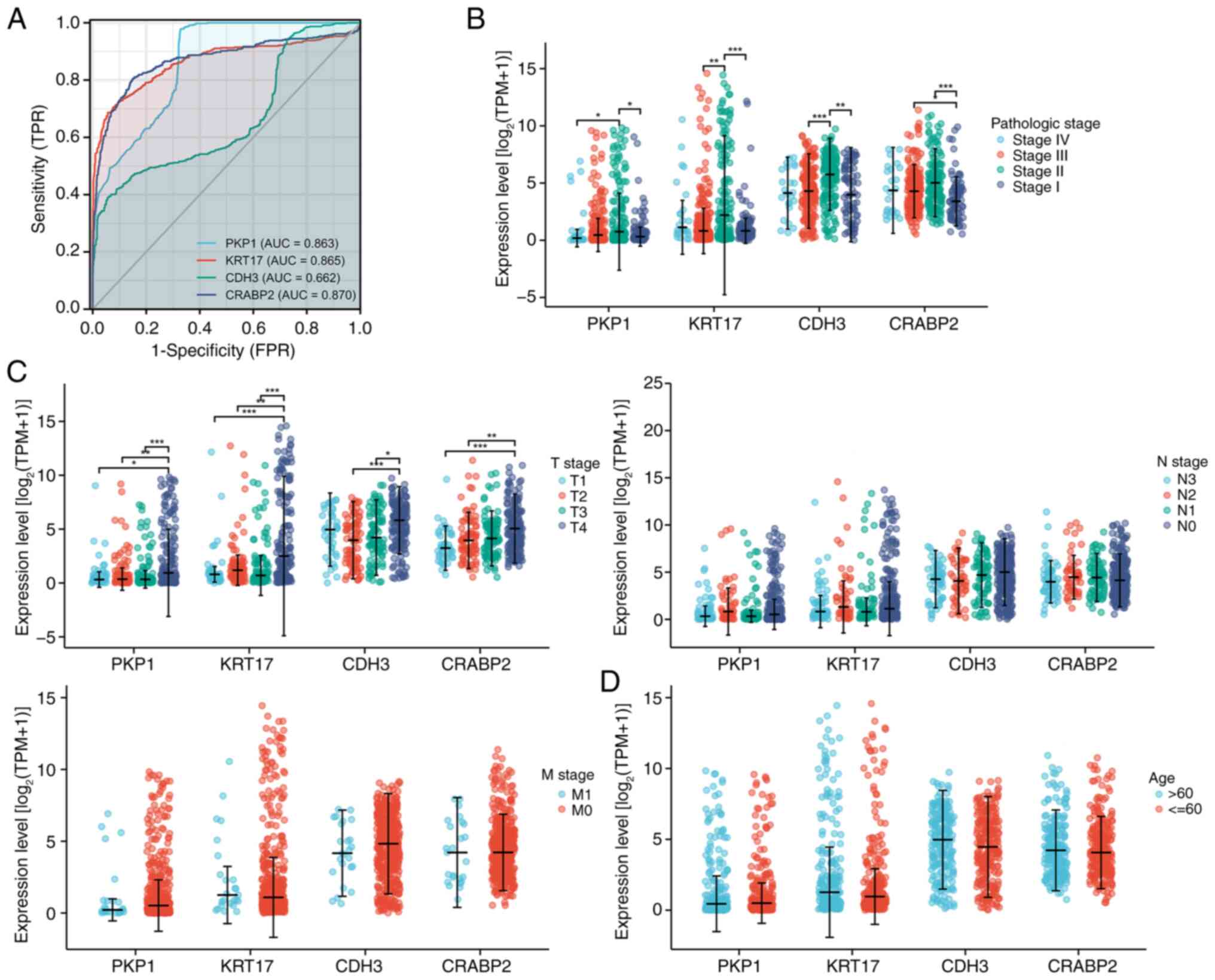

Clinical significance of KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3 and CRABP2 in patients with SKCM

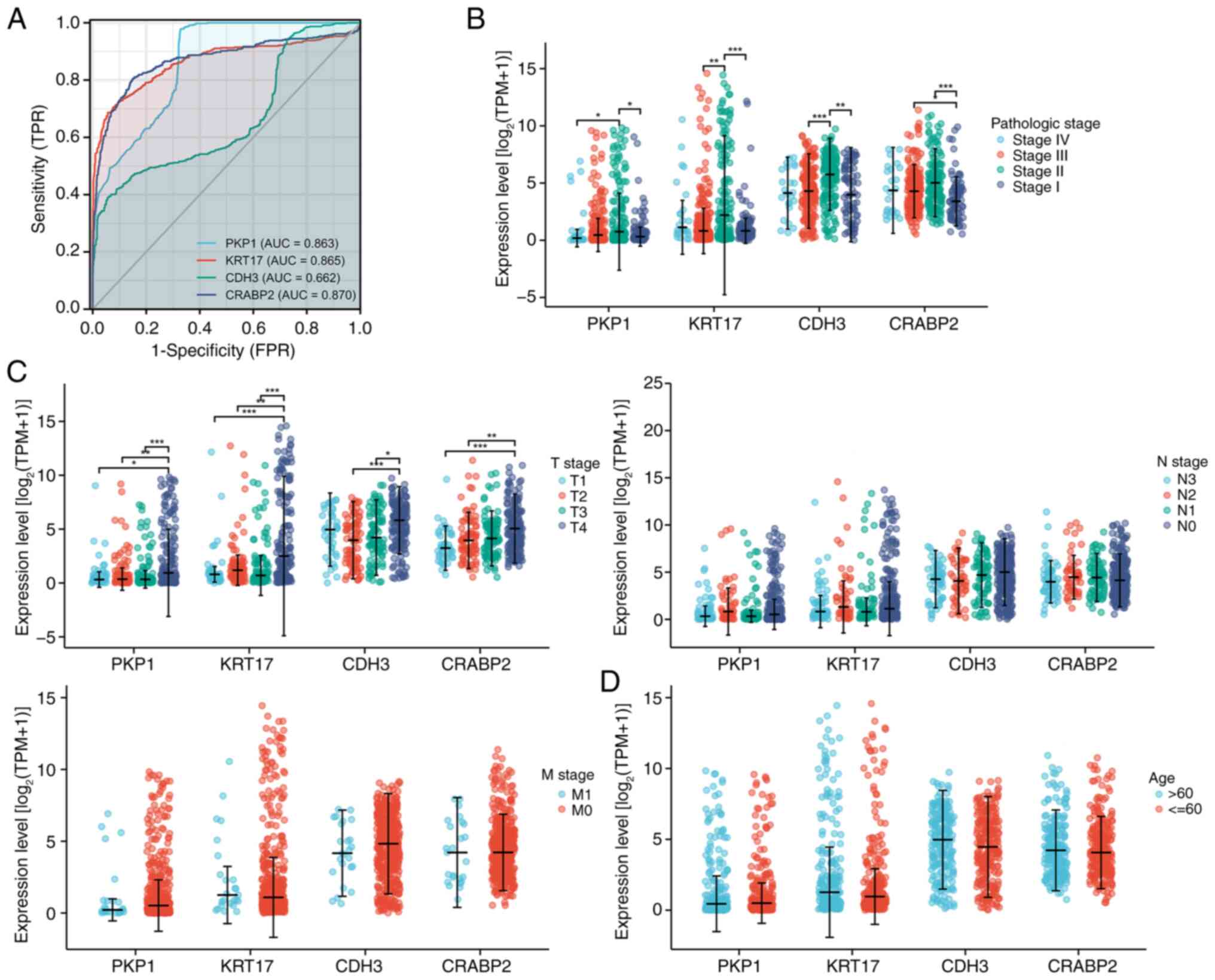

ROC curves revealed that KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 demonstrated predictive power for OS in the TCGA cohort of

patients with SKCM (Fig. 7A). The

associations of these genes with clinical factors was then further

assessed. KRT17, PKP1, CDH3, and CRABP2 demonstrated a positive

association with pathological stage (Fig. 7B). For tumor (T)-node (N)-metastasis

(M) staging, their expression levels were significantly associated

with the T stage, but had no discernable association with N or M

stages (Fig. 7C). Similarly, no

significant association was revealed between their expression and

patient age (Fig. 7D).

| Figure 7.Clinical significance of KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3 and CRABP2 expression in patients with SKCM. (A) Receiver

operating characteristic curves of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2

expression of patients with SKCM in The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort.

(B) Expression levels of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 were

positively associated with the pathological stage. (C) In TNM

staging, the expression of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 were only

significantly associated with T stage, but not with N and M stage.

(D) No association was demonstrated between KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 expression and age. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

KRT17, keratin 17; PKP1, plakophilin 1; CDH3, cadherin 3; CRABP2,

cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2; SKCM, skin cutaneous

melanoma; TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive rate; AUC,

area under the curve; TPM, transcripts per million; T, tumor; N,

node; M, metastasis. |

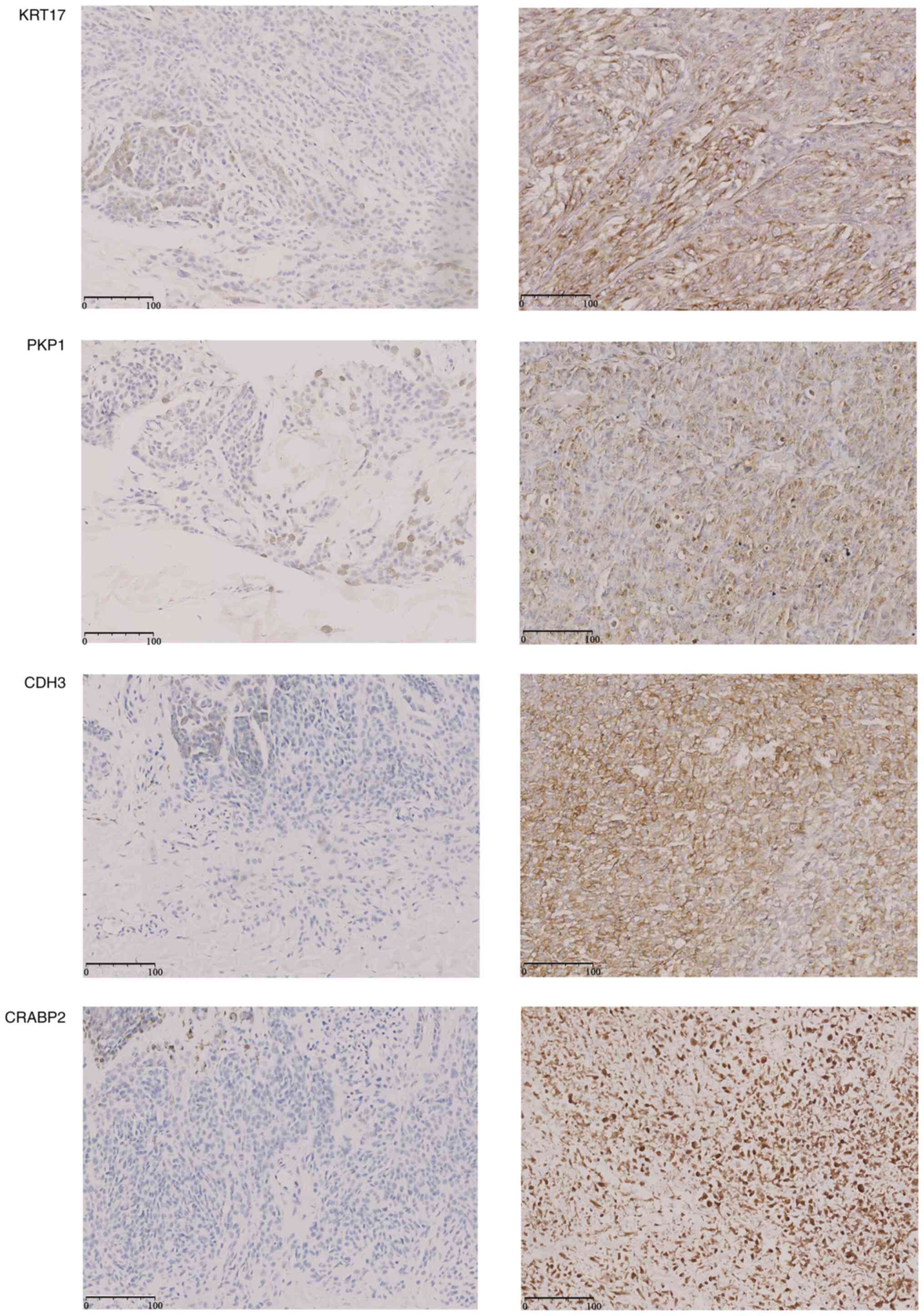

Expression of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 in SKCM tissues

Representative immunohistochemistry images

demonstrated markedly higher cytoplasmic staining for all four

genes in tumor tissues compared with in adjacent skin (Fig. 8). Consistently, RT-qPCR analysis on

the same sample set showed 2.3- to 4.5-fold upregulation at the

mRNA level (Fig. S5). These

concordant protein and transcript results corroborate the

bioinformatic prediction of the present study that the four hub

genes are overexpressed in metastatic SKCM.

Discussion

SKCM is a highly malignant tumor derived from

melanocytes, known for its poor prognosis and strong invasiveness.

Risk factors such as ultraviolet exposure, excessive pigmented

nevi, a family history of melanoma and a higher number of nevi lead

to DNA damage that can initiate carcinogenesis (38,39).

Despite emerging diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, clinical

options remain limited as SKCM often progresses rapidly and is

frequently asymptomatic in the early stages (1). Hence, elucidating the molecular

mechanisms underlying SKCM is paramount for improving treatment

outcomes and patient prognosis.

Research has reported that abnormal m6A modification

is closely associated with tumorigenesis and progression, as m6A

modulates numerous processes (such as mRNA splicing, 3′-end

processing, nuclear export, translational regulation, mRNA decay

and miRNA biogenesis) and that its dynamic reversibility influences

tumor cell growth and differentiation (40). This role has been reported in

several cancers, including cervical cancer (41), acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

(42), pancreatic cancer (43) and hepatocellular carcinoma (44). However, the specific molecular

mechanisms mediated by m6A in SKCM are not yet fully

understood.

The present study comprehensively analyzed four

metastatic SKCM cohorts from the GEO database (GSE8401, GSE15605,

GSE46517 and GSE65904), identifying a total of 823 DEGs, comprising

283 upregulated and 540 downregulated genes. GO enrichment analysis

indicated that the DEGs are predominantly involved in biological

pathways such as cornification, epidermis development and

keratinization, with genes including CTSG, sphingosine-1-phosphate

lyase 1 and S100A8 serving pivotal roles. These findings underscore

that SKCM metastasis is accompanied by proliferation and

keratinization in epidermal/epithelial cells. Similarly,

keratinization has been associated with a poor prognosis in human

papillomavirus-negative oropharyngeal carcinoma (45).

Subsequently, the present study constructed a

survival prediction model in the TCGA database using LASSO-Cox

analysis. The results revealed that KRT5, KRT17, PKP1, KRT15, FLG,

CSTA, CRABP2, CST6, CALML5, CDH3, S100A8 and CTSG were

significantly associated with OS. Elevated expression of these

genes was closely associated with poor outcomes. Multiple studies

have reported that m6A RNA modification, such as DNA methylation

and histone modifications, exerts regulatory control over

tumorigenesis via methyltransferases and demethylases (46). However, the precise mechanism by

which m6A may affect melanoma progression in an mRNA-dependent

manner remains elusive. Therefore, the present study employed

Pearson correlation analysis to identify m6A-related metastasis

genes in SKCM, and the findings revealed that KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 exhibit strong associations with m6A regulation and OS in

patients with melanoma.

Further single-gene differential expression analysis

of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 revealed 91 commonly differentially

expressed lncRNAs. A lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA triple regulatory network

comprising 20 miRNAs and 13 lncRNAs was then constructed. In

addition, enrichment analysis demonstrated that 494

co-differentially expressed mRNAs associated with KRT17, PKP1, CDH3

and CRABP2 are primarily enriched in the estrogen signaling

pathway, Ras signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor

interaction, melanogenesis and chemical carcinogenesis. Notably,

melanin and its synthesis process itself can affect melanoma

behavior by regulating oxidative stress, drug sensitivity and

immune escape, thus having a profound impact on prognosis (47).

Previous studies indicate that KRTs are crucial in

epidermal development, intermediate filament organization,

cytoskeletal reorganization, keratinization and keratinocyte

migration in patients with melanoma (48–50).

In particular, KRT17 has been identified as a diagnostic and

prognostic marker in breast cancer (51), epithelial ovarian cancer (52), cervical squamous cell carcinoma

(53) and gastric cancer (54). Moreover, PKP1, a key component of

desmosomes, has been reported to be abnormally expressed in

multiple cancers, including prostate cancer (54), oral squamous cell carcinoma

(55) and esophageal adenocarcinoma

(56), regulating tumor cell

proliferation, colony formation, migration/invasion and apoptosis.

In lung cancer, high PKP1 expression has been markedly associated

with favorable clinical prognosis, whereas its downregulation is

associated with hypermethylation of its promoter region (57). CDH3, which encodes P-cadherin, is a

core component of adherens junctions and contributes to the

development and progression of several malignancies (58). In patients with adenomyosis,

aberrant expression of m6A regulators has been associated with

dysregulated CDH3, sodium voltage-gated channel β subunit 4 and

placenta associated 8 (59). CRABP2

also serves important roles in multiple tumors. In hepatocellular

carcinoma, downregulation of CRABP2 has been reported to inhibit

tumor formation in vivo (59). Additionally, Yan et al

(60) reported that mutations in

ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor, CRABP2, galanin And GMAP

prepropeptide, and progestagen associated endometrial protein

markedly affected immune infiltration in melanoma.

Furthermore, the investigation of 21 m6A regulators

revealed significant differences in the expression of several

factors (METTL3, WTAP, YTHDC1, YTHDF2, ALKBH5, VIRMA, RBM15,

ZC3H13, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, HNRNPC,

HNRNPA2B1 and RBMX) between normal and tumor samples. Among these,

ALKBH5, an important ‘eraser’ in the m6A regulatory system,

influences tumor growth and metastasis by demethylating specific

transcripts. In breast cancer, ALKBH5-mediated demethylation

upregulates NANOG expression, promoting cancer stem cell

specification and metastatic capacity (61). ALKBH5 is also highly expressed in

lung adenocarcinoma cells, and its knockout can suppress cancer

cell proliferation and invasion by increasing m6A modification of

forkhead box M1 (62).

Additionally, the m6A methyltransferase WTAP forms a

complex with METTL3 and METTL14 and co-localizes in the nucleus to

participate in RNA methylation. Research has reported that, under

the influence of the hepatocellular carcinoma suppressor ETS1, WTAP

regulates the cell cycle in liver cancer via a p21/p27-dependent

mechanism (63,64). METTL3 and METTL14 are likewise

implicated in oncogenic proliferation and metastasis (65,66).

In the cohort in the present study, all three genes were

significantly upregulated in metastatic SKCM relative to normal

skin, suggesting a potential but as-yet unproven role in melanoma

progression. To move beyond bioinformatic association, follow-up

experiments, such as chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR to confirm

direct binding of the complex to target promoters and RNA

immunoprecipitation-qPCR to assess m6A modification on specific

transcripts, will be necessary to clarify causality in future

studies.

However, the ceRNA network presented in the present

study is exploratory. Although most miRNA-RNA edges were retrieved

from the TarBase and miRWalk records supported by cross-linking

immunoprecipitation (CLIP)-sequencing, immunoprecipitation or

reporter assays, in-situ validation (such as argonaute-CLIP,

biotinylated RNA pull-down or dual-luciferase assays) was not

performed in the present study. Furthermore, the localization

filter relied on computational predictors rather than fractionation

experiments. Future work will need to verify key triplets,

particularly the SOX21-AS1/hsa-miR-1276/KRT17 and

hsa-miR-151a-3p/PKP1 axes, in melanoma cell lines and

patient-derived samples.

Subsequently, the association between KRT17, PKP1,

CDH3 and CRABP2 expression and immune infiltration in SKCM was

assessed, and the results indicated that these four genes are

positively correlated with mast cells and Th17 cells and negatively

correlated with B cells and Th1 cells. Immunomodulatory shifts in

the tumor microenvironment serve vital roles in tumor metastasis.

In a murine melanoma endothelial model, upregulated indoleamine

2,3-dioxygenase 1 was reported to respond to CD40 agonist

immunotherapy-induced IFN-γ production, suggesting a novel

immunosuppressive feedback mechanism (67). Similarly, Singh et al

(23) reported that focal

ultrasound heating combined with anti-CD40 agonist antibodies

markedly improved T-cell and macrophage function in melanoma. These

findings initially suggest that m6A regulators may alter SKCM

progression and prognosis by influencing KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 expression and remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment.

Notably, in the present study, KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2

demonstrated significant differential expression across T stages

but not in N and M stages, implying that these genes may have a

greater role in local tumor growth and tissue infiltration rather

than lymph node or distal metastasis. However, further large-scale

multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings and

explore the underlying molecular mechanisms. Furthermore, there is

growing evidence that cancer cells can ‘rewire’ the neuro-endocrine

network of the host by secreting hormone-like factors and

neurotransmitters to shape a supportive microenvironment (68). This autonomous regulation capability

suggests that when targeting m6A-related pathways, its potential

interaction with the whole-body steady-state axis should also be

considered. If future experiments confirm that genes such as KRT17

or PKP1 critically regulate m6A modifications and the immune

microenvironment, they may hold promise for early diagnosis, risk

stratification and novel immunotherapeutic approaches in SKCM.

Lastly, RT-qPCR experiments demonstrated higher

expression levels of KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 in SKCM tumor

tissues compared with in adjacent normal tissues. Thus, we

hypothesize that m6A modification may influence SKCM metastasis by

modulating the expression of these four genes. Nevertheless,

certain limitations should be noted. First, although the in

silico analyses in the present study are generally in-line with

previous findings, larger, multicenter clinical cohorts are

required to enhance reliability. Moreover, further in vitro

and in vivo functional experiments are needed to clarify the

mechanisms by which m6A modification and KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and

CRABP2 operate in SKCM. Furthermore, although analyzing the

correlation between these four genes and clinicopathological

variables has important research value for the prognosis of SKCM

patients, disease-free survival (DFS) and tumor-stage-stratified

correlations were not incorporated as in the TCGA-SKCM cohort. This

is since, in the dataset used for this study, DFS data are missing

for 65% of patients and the recorded follow-up periods are highly

heterogeneous (median, 6.2 months; interquartile range, 1.8–11.5

months). Preliminary modelling under these conditions yielded

unstable HR estimates that risk over-interpretation. Consequently,

survival analyses were restricted to OS, for which follow-up is

more complete, and immune-infiltration profiling plus experimental

validation was focused on. Future studies in prospective cohorts

with comprehensive DFS information will be required to extend and

confirm the prognostic relevance of the selected markers across

multiple clinical endpoints.

In summary, the results of the present study

demonstrate that KRT17, PKP1, CDH3 and CRABP2 expression are

regulated by m6A modification and may influence SKCM metastasis,

ultimately altering patient survival. Moreover, immune

microenvironment analyses suggested that mast cells, Th17 cells, B

cells and Th1 cells serve critical roles in this process. These

findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of SKCM

metastasis and potential therapeutic targets. Nonetheless, further

research and larger clinical samples are required for more in-depth

validation and exploration.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81772916 and 82103470) and the

Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no.

BK20171132).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YG was responsible for study concept design, data

organization, formal analysis and drafting the initial manuscript.

SZ contributed to data visualization and analysis, manuscript

drafting, revision, and final approval. TG was responsible for data

validation, study concept design, data review and editing. XLX

contributed to study concept design, provided and obtained research

resources, and participated in manuscript review and revision. XZ

contributed to study concept design, data organization, manuscript

writing and final manuscript approval. YG and XZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Institute of Dermatology, Peking Union Medical

College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (approval no.

2017-KY-044). Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C,

Griewank KG, Gutzmer R, Hauschild A, Stang A, Roesch A and Ugurel

S: Melanoma. Lancet. 392:971–984. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:7–30. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR,

Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, Lazar AJ, Faries MB, Kirkwood JM,

McArthur GA, et al: Melanoma staging: Evidence-Based changes in the

American joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging

manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:472–492. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Slominski RM, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z,

Brożyna AA, Podgorska E, Dixon KM, Mason RS, Tuckey RC, Sharma R,

Crossman DK, et al: Malignant melanoma: An overview, new

perspectives, and vitamin D signaling. Cancers (Basel).

16:22622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Slominski RM, Raman C, Jetten AM and

Slominski AT: Neuro-immuno-endocrinology of the skin: How

environment regulates body homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

21:495–509. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Slominski RM, Chen JY, Raman C and

Slominski AT: Photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology: How the ultraviolet

radiation regulates the body, brain, and immune system. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 121:e23083741212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tan B, Liu H, Zhang S, da Silva SR, Zhang

L, Meng J, Cui X, Yuan H, Sorel O, Zhang SW, et al: Viral and

cellular N6-Methyladenosine and

N6,2′-O-Dimethyladenosine epitranscriptomes in the KSHV

life cycle. Nat Microbiol. 3:108–120. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pfeifer GP: Defining driver DNA

methylation changes in human cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 19:11662018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang

Z and Zhao JC: N6-Methyladenosine modification destabilizes

developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol.

16:191–198. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N

and Tavazoie SF: N6-Methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for

processing. Nature. 519:482–485. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Huang H, Weng H and Chen J: m6A

modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: Roles and therapeutic

implications in cancer. Cancer Cell. 37:270–288. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Huang H, Weng H and Chen J: The biogenesis

and precise control of RNA m6A methylation. Trends

Genet. 36:44–52. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Huang H, Weng H, Deng X and Chen J: RNA

modifications in cancer: Functions, mechanisms, and therapeutic

implications. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 4:221–240. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Weng H, Huang H, Wu H, Qin X, Zhao BS,

Dong L, Shi H, Skibbe J, Shen C, Hu C, et al: METTL14 inhibits

hematopoietic stem/progenitor differentiation and promotes

leukemogenesis via mRNA m6A modification. Cell Stem

Cell. 22:191–205. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang C, Chen Y, Sun B, Wang L, Yang Y, Ma

D, Lv J, Heng J, Ding Y, Xue Y, et al: m6A modulates

haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell specification. Nature.

549:273–276. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C,

Huang H, Nachtergaele S, Dong L, Hu C, et al: FTO plays an

oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a

N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell.

31:127–141. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, Lin K, Zheng S,

Lu Z, Chen Y, Sulman EP, Xie K, Bögler O, et al: m6A demethylase

ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by

Sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer

Cell. 31:591–606.e6. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhang C, Samanta D, Lu H, Bullen JW, Zhang

H, Chen I, He X and Semenza GL: Hypoxia induces the breast cancer

stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated

m6A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:E2047–E2056. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

He F, Yu J, Yang J, Wang S, Zhuang A, Shi

H, Gu X, Xu X, Chai P and Jia R: m6A RNA

hypermethylation-induced BACE2 boosts intracellular calcium release

and accelerates tumorigenesis of ocular melanoma. Mol Ther.

29:2121–2133. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dahal U, Le K and Gupta M: RNA m6A

methyltransferase METTL3 regulates invasiveness of melanoma cells

by matrix metallopeptidase 2. Melanoma Res. 29:382–389. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu L, Shen SS, Hoshida Y, Subramanian A,

Ross K, Brunet JP, Wagner SN, Ramaswamy S, Mesirov JP and Hynes RO:

Gene expression changes in an animal melanoma model correlate with

aggressiveness of human melanoma metastases. Mol Cancer Res.

6:760–769. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cabrita R, Lauss M, Sanna A, Donia M,

Larsen MS, Mitra S, Johansson I, Phung B, Harbst K,

Vallon-Christersson J, et al: Tertiary lymphoid structures improve

immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature. 577:561–565. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Singh MP, Sethuraman SN, Ritchey J,

Fiering S, Guha C, Malayer J and Ranjan A: In-situ vaccination

using focused ultrasound heating and anti-CD-40 agonistic antibody

enhances T-cell mediated local and abscopal effects in murine

melanoma. Int J Hyperthermia. 36:64–73. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Raskin L, Fullen DR, Giordano TJ, Thomas

DG, Frohm ML, Cha KB, Ahn J, Mukherjee B, Johnson TM and Gruber SB:

Transcriptome profiling identifies HMGA2 as a biomarker of melanoma

progression and prognosis. J Invest Dermatol. 133:2585–2592. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Xu F, Lin H, He P, He L, Chen J, Lin L and

Chen Y: A TP53-associated gene signature for prediction of

prognosis and therapeutic responses in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 9:17319432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li H, Han D, Hou Y, Chen H and Chen Z:

Statistical inference methods for two crossing survival curves: A

comparison of methods. PLoS One. 10:e01167742015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kolde R, Laur S, Adler P and Vilo J:

Robust rank aggregation for gene list integration and

meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 28:573–580. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M,

Khodabakhshi A.H, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C and Chanda SK: Metascape

provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of

systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 10:15232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zaccara S, Ries RJ and Jaffrey SR:

Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 20:608–624. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T,

Sander C and Marks DS: MicroRNA targets in drosophila. Genome Biol.

5:R12003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney

J.GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq

data. BMC Bioinformatics. 14:72013.

|

|

35

|

Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M,

Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T,

Lafontaine L, Berger A, et al: Spatiotemporal dynamics of

intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human

cancer. Immunity. 39:782–795. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L and

Pandolfi PP: A ceRNA hypothesis: The rosetta stone of a hidden RNA

language? Cell. 146:353–358. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, Weenig

RH, Pockaj BA, Bardia A, Vachon CM, Schild SE, McWilliams RR, Hand

JL, et al: Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 1:

Epidemiology, risk factors, screening, prevention, and diagnosis.

Mayo Clin Proc. 82:364–380. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Osipov M and Sokolnikov M: Previous

malignancy as a risk factor for the second solid cancer in a cohort

of nuclear workers. SciMedicine J. 3:8–15. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Jiang X, Liu B, Nie Z, Duan L, Xiong Q,

Jin Z, Yang C and Chen Y: The role of m6A modification in the

biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

6:742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang X, Li Z, Kong B, Song C, Cong J, Hou

J and Wang S: Reduced m6A mRNA methylation is correlated

with the progression of human cervical cancer. Oncotarget.

8:98918–98930. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kwok CT, Marshall AD, Rasko JEJ and Wong

JJL: Genetic alterations of m6A regulators predict

poorer survival in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol.

10:392017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Cho SH, Ha M, Cho YH, Ryu JH, Yang K, Lee

KH, Han ME, Oh SO and Kim YH: ALKBH5 gene is a novel biomarker that

predicts the prognosis of pancreatic cancer: A retrospective

multicohort study. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 22:305–309.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhao X, Chen Y, Mao Q, Jiang X, Jiang W,

Chen J, Xu W, Zhong L and Sun X: Overexpression of YTHDF1 is

associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cancer Biomarkers. 21:859–868. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Slebos RJC, Jehmlich N, Brown B, Yin Z,

Chung CH, Yarbrough WG and Liebler DC: Proteomic analysis of

oropharyngeal carcinomas reveals novel HPV-associated biological

pathways. Int J Cancer. 132:568–579. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Deng X, Su R, Feng X, Wei M and Chen J:

Role of N6-methyladenosine modification in cancer. Curr

Opin Genet Dev. 48:1–7. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Slominski RM, Sarna T, Płonka PM, Raman C,

Brożyna AA and Slominski AT: Melanoma, melanin, and melanogenesis:

The yin and yang relationship. Front Oncol. 12:8424962022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Han W, Hu C, Fan ZJ and Shen GL:

Transcript levels of keratin 1/5/6/14/15/16/17 as potential

prognostic indicators in melanoma patients. Sci Rep. 11:10232021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Han Y, Li X, Yan J, Ma C, Wang X, Pan H,

Zheng X, Zhang Z, Gao B and Ji XY: Bioinformatic analysis

identifies potential key genes in the pathogenesis of melanoma.

Front Oncol. 10:5819852020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kodet O, Lacina L, Krejčí E, Dvořánková B,

Grim M, Štork J, Kodetová D, Vlček Č, Šáchová J, Kolář M, et al:

Melanoma cells influence the differentiation pattern of human

epidermal keratinocytes. Mol Cancer. 14:12015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

van de Rijn M, Perou CM, Tibshirani R,

Haas P, Kallioniemi O, Kononen J, Torhorst J, Sauter G, Zuber M,

Köchli OR, et al: Expression of cytokeratins 17 and 5 identifies a

group of breast carcinomas with poor clinical outcome. Am J Pathol.

161:1991–1996. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang YF, Lang HY, Yuan J, Wang J, Wang R,

Zhang XH, Zhang J, Zhao T, Li YR, Liu JY, et al: Overexpression of

keratin 17 is associated with poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian

cancer. Tumour Biol. 34:1685–1689. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Escobar-Hoyos LF, Yang J, Zhu J, Cavallo

JA, Zhai H, Burke S, Koller A, Chen EI and Shroyer KR: Keratin 17

in premalignant and malignant squamous lesions of the cervix:

Proteomic discovery and immunohistochemical validation as a

diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. Mod Pathol. 27:621–630. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Chivu-Economescu M, Dragu DL, Necula LG,

Matei L, Enciu AM, Bleotu C and Diaconu CC: Knockdown of KRT17 by

siRNA induces antitumoral effects on gastric cancer cells. Gastric

Cancer. 20:948–959. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Harris TM, Du P, Kawachi N, Belbin TJ,

Wang Y, Schlecht NF, Ow TJ, Keller CE, Childs GJ, Smith RV, et al:

Proteomic analysis of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma specimens

identifies patient outcome-associated proteins. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 139:494–507. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kaz AM, Luo Y, Dzieciatkowski S, Chak A,

Willis JE, Upton MP, Leidner RS and Grady WM: Aberrantly methylated

PKP1 in the progression of Barrett's esophagus to esophageal

adenocarcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 51:384–393. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Haase D, Cui T, Yang L, Ma Y, Liu H, Theis

B, Petersen I and Chen Y: Plakophilin 1 is methylated and has a

tumor suppressive activity in human lung cancer. Exp Mol Pathol.

108:73–79. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Xu Y, Zhao J, Dai X, Xie Y and Dong M:

High expression of CDH3 predicts a good prognosis for colon

adenocarcinoma patients. Exp Ther Med. 18:841–847. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhai J, Li S, Sen S, Opoku-Anane J, Du Y,

Chen ZJ and Giudice LC: m6A RNA methylation regulators

contribute to eutopic endometrium and myometrium dysfunction in

adenomyosis. Front Genet. 11:71620202020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yan J, Wu X, Yu J, Zhu Y and Cang S:

Prognostic role of tumor mutation burden combined with immune

infiltrates in skin cutaneous melanoma based on multi-omics

analysis. Front Oncol. 10:5706542020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Zhang C, Zhi WI, Lu H, Samanta D, Chen I,

Gabrielson E and Semenza GL: Hypoxia-Inducible factors regulate

pluripotency factor expression by ZNF217- and ALKBH5-mediated

modulation of RNA methylation in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget.

7:64527–64542. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Chao Y, Shang J and Ji W:

ALKBH5-m6A-FOXM1 signaling axis promotes proliferation

and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells under intermittent

hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 521:499–506. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Schöller E, Weichmann F, Treiber T, Ringle

S, Treiber N, Flatley A, Feederle R, Bruckmann A and Meister G:

Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the

m6A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA.

24:499–512. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Chen Y, Peng C, Chen J, Chen D, Yang B, He

B, Hu W, Zhang Y, Liu H, Dai L, et al: WTAP facilitates progression

of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic

silencing of ETS1. Mol Cancer. 18:1272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, Liu F, Yuan JH,

Wang F, Wang TT, Xu QG, Zhou WP and Sun SH: METTL14 suppresses the

metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating

N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA

processing. Hepatology. 65:529–543. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Chen M, Wei L, Law CT, Tsang FHC, Shen J,

Cheng CLH, Tsang LH, Ho DWH, Chiu DKC, Lee JMF, et al: RNA

N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase-like 3 promotes liver cancer

progression through YTHDF2-dependent posttranscriptional silencing

of SOCS2. Hepatology. 67:2254–2270. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Georganaki M, Ramachandran M, Tuit S,

Núñez NG, Karampatzakis A, Fotaki G, van Hooren L, Huang H, Lugano

R, Ulas T, et al: Tumor endothelial cell up-regulation of IDO1 is

an immunosuppressive feed-back mechanism that reduces the response

to CD40-stimulating immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 9:17305382020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Slominski RM, Raman C, Chen JY and

Slominski AT: How cancer hijacks the body's homeostasis through the

neuroendocrine system. Trends Neurosci. 46:263–275. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|