Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC), a highly malignant neoplasm

of the digestive system with a 5-year survival rate of <10%, is

recognized as the ‘king of cancer types’ (1). According to data from the

International Agency for Research on Cancer, ~496,000 new PC cases

and 466,000 related deaths were reported globally in 2020, which

ranks PC as the seventh leading cause of cancer mortality in both

sexes (2). The pathogenesis of PC

is characterized by complex interactions between multiple genetic

and environmental factors. The associated genetic factors include

regulatory molecules, such as tiRNA-Val-CAC-2, which has been shown

to interact with FUBP1 to promote PC metastasis by activating c-MYC

transcription (3); and the

environmental factors encompass smoking and excessive alcohol

consumption. Furthermore, recurrent acute pancreatitis, often

linked to the aforementioned environmental triggers, can augment

long-term PC risk (4). Current

therapeutic modalities remain limited and primarily include

surgical intervention, chemotherapy and radiotherapy (5–7).

However, due to the aggressive biological behaviour of PC, ~80% of

patients present with advanced-stage disease at diagnosis (1), which results in limited opportunities

for radical resection and suboptimal outcomes with conventional

chemo-radiotherapeutic approaches.

Gemcitabine (GEM) remains one of the most widely

used chemotherapeutic agents in PC management (8). Its mechanism of action involves

incorporation into DNA during synthesis, thereby inducing strand

fragmentation and cell cycle arrest (9). However, in the hypoxic tumour

microenvironment (TME), multiple resistance mechanisms have emerged

that undermine GEM efficacy. Specifically, these mechanisms include

reduced drug uptake (for example, loss of the human equilibrative

nucleoside transporter 1), enhanced DNA repair capacity and

metabolic reprogramming (10).

These resistance mechanisms contribute to the limited clinical

efficacy of GEM, which is characterized by an overall response rate

of<20% and frequent development of rapid tumour resistance

(8,11). Therefore, elucidating the molecular

mechanisms underlying chemoresistance and identifying effective

therapeutic targets to overcome drug resistance have become key

challenges in contemporary PC treatment research.

Although recent advancements have been made in

targeted therapies and immunotherapies for PC, its complex TME

remains a pivotal factor contributing to therapeutic failure

(12). The highly fibrotic stroma

and aberrant vascular proliferation in PC result in persistent

intratumoural hypoxia, which fosters a hypoxic microenvironment.

This hypoxic niche, a recognized hallmark of PC, drives tumour

progression, metastasis and chemoresistance through

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-mediated activation of multiple

oncogenic signalling pathways (including the VEGF pathway, the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and the Notch/Wnt/β-catenin pathways)

(13–16). Previous studies have revealed that

hypoxia markedly enhances the exosomal secretion capacity of tumour

cells (17–19).

Exosomes (Exos), extracellular vesicles measuring

40–160 nm in diameter, serve as molecular carriers within the TME

by transporting bioactive cargo (for example, proteins, lipids and

nucleic acids) to mediate intercellular communication. Under

hypoxic conditions, tumour-derived Exos can modulate drug

sensitivity through the horizontal transfer of non-coding RNAs,

particularly microRNAs (miRNAs). For example, hypoxia-induced Exos

carrying miR-210-3p promote proliferation, migration, invasion,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis resistance in

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells through the activation

of the nuclear factor I X-Wnt/β-catenin signalling axis (20). Nevertheless, the mechanistic role of

hypoxia-derived exosomal miRNAs in GEM resistance remains to be

elucidated, which represents a key frontier in contemporary PC

research.

miR-301a, a key member of the miRNA family, is

markedly upregulated across multiple malignancies, such as breast

cancer and gastric cancer, and participates in oncogenic processes

including proliferation, invasion and immune evasion through

targeted gene regulation (21,22).

Its tumour-promoting effects may be mediated through the

suppression of tumour suppressor genes such as PTEN and SMAD4

(23,24). Our preliminary investigations

demonstrated that miR-301a acts as a key regulator involved in

hypoxia-induced gemcitabine resistance in PC. Furthermore, hypoxia

induces the upregulation of miR-301a within tumour-derived Exos

(25,26). These Exos can be internalized by

neighbouring malignant cells, subsequently modulating their

biological behaviours, although the precise molecular mechanisms

remain to be fully elucidated.

Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4

(ACSL4), a key enzyme in fatty acid metabolism, catalyses the

conjugation of long-chain fatty acids with coenzyme A to generate

acyl-CoA derivatives, thereby regulating membrane phospholipid

remodelling, signal transduction and energy metabolism (27). Dysregulated ACSL4 expression has

been implicated in the progression of multiple cancer types. For

example, in TNBC, aberrant ACSL4 expression mediates cell membrane

phospholipid remodelling, inducing lipid raft localization and

integrin β1 activation in a CD47-dependent manner, which promotes

tumour metastasis via focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation

(28). In hepatocellular carcinoma,

ACSL4 enhances tumour cell proliferation and metastasis by

regulating de novo lipid synthesis (29). Notably, ACSL4 has emerged as a key

regulator of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death

driven by lipid peroxidation (30).

MiRNAs have also been revealed to modulate ACSL4-mediated

processes: MiR-23a-3p promotes sorafenib resistance in

hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting ACSL4 expression and

blocking ferroptosis (31), whereas

miR-20a-5p alleviates ferroptosis in renal ischaemia-reperfusion

injury by directly targeting the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of

ACSL4 mRNA (32). Notably, emerging

evidence suggests that ACSL4 also contribute to GEM resistance in

PC, although the underlying mechanisms remain largely undefined

(33).

The present study aimed to investigate the

functional impact of hypoxic tumour-derived exosomal miR-301a on

GEM resistance in PC and elucidate its underlying molecular

mechanisms. The present study provides novel insights into the

chemoresistance landscape of PC and establishes a theoretical

foundation for the potential development of exosomal miRNA-based

combinatorial therapeutic strategies in the future.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

Cell line information

Descriptions of the original cell line derivation

are shown in Table I (34).

| Table I.Cell line characteristics. |

Table I.

Cell line characteristics.

| Cell line | Derivation | Molecular

subtype | Aggressiveness

level | Key genetic

features |

|---|

| BxPC-3 | Primary tumour | Classical |

Low-to-moderate | Wild-type KRAS,

SMAD4 intact |

| CFPAC-1 | Liver

metastasis | Basal-like | Moderate | KRAS G12V, TP53

mutant |

| AsPC-1 | Ascites | Basal-like | High | KRAS G12V, TP53

mutant |

| MIA PaCa-2 | Primary tumour | Classical | High | KRAS G12C, TP53

mutant |

| PANC-1 | Primary tumour | Basal-like | Highly

aggressive | KRAS G12D, SMAD4

deleted |

Cell culture

All the cell lines used in the present study

[ascites pancreatic cancer 1 (AsPC-1), BxPC-3, cystic fibrosis

pancreatic adenocarcinoma (CFPAC-1), malignant inflammatory

adenocarcinoma pancreatic carcinoma-2 (MIA PaCa-2) and PANC-1)]

were purchased from the Shanghai Cell Bank at the Chinese Academy

of Sciences. MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells were cultured in DMEM

(cat. no. C11995500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. FSP500; Shanghai ExCell

Biology, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. C0222;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cells were

cultured in RPMI-1640 (cat no. C11875500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin. CFPAC-1 cells were cultured in Iscove's

Modified Dulbecco's Medium (cat. no. BL312A; Biosharp Life

Sciences) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

All the cell lines were cultured in an incubator at 37°C in an

atmosphere containing 5% CO2. During hypoxic treatment,

the cells were cultured in a hypoxic incubator (37°C; 5%

CO2; 1% O2).

Cell transfection

The miR-301a inhibitor, miR-301a mimics and their

respective negative control (NC) oligonucleotides were synthesized

by Anhui General Bioscience. The sequences are presented in

Table II. Transfection was

performed using Lipofectamine® 2000 transfection reagent

(cat. no. 11668019; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), a

widely used cationic lipid transfection reagent, for which the

manufacturer's protocol recommends a 4–6 h incubation period in a

37°C incubator for optimal nucleic acid delivery while minimizing

cytotoxicity. However, based on our long-term research experience

on the effects and molecular mechanisms of non-coding RNAs in the

malignant biology of pancreatic tumours, the present study extended

the transfection time to 6–8 h to balance transfection efficiency

and cell viability. The specific steps were as follows: Cells under

good growth conditions, characterized by 50–80% confluence (in the

logarithmic growth phase), ≥90% cell viability, normal cell

morphology and no microbial contamination, were evenly plated in a

6-well plate, 1 day before transfection. Transfection was initiated

when the cell confluence reached 60–70%. Preparation of

transfection mixtures: For each well, 5 µl of

Lipofectamine® 2000 was added to 250 µl of Opti-MEM

Reduced Serum Medium (cat. no. L530JV; Shanghai Basal Media

Technologies Co., Ltd.) in a sterile centrifuge tube and gently

mixed. This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min to

allow the Lipofectamine® 2000 to activate. Meanwhile, in

another sterile centrifuge tube, 20 nM of the miR-301a inhibitor,

mimics or NC oligonucleotide was diluted in 250 µl of Opti-MEM

reduced serum medium. The diluted oligonucleotide mixture was then

slowly added to the activated Lipofectamine®

2000-Opti-MEM mixture and mixed gently by pipetting up and down

several times. The resulting transfection mixture was incubated at

room temperature for 20 min to form stable

Lipofectamine®-oligonucleotide complexes. The culture

medium in each well was carefully aspirated and replaced with 1.5

ml of serum-free medium. The prepared transfection mixture was then

added dropwise to each well and the plates were gently swirled to

ensure the even distribution of the complexes. After 6–8 h, the

medium containing serum and antibiotics was replaced, and the cells

were further cultured for 24 or 48 h for subsequent

experiments.

| Table II.Inhibitor and mimics sequences. |

Table II.

Inhibitor and mimics sequences.

| RNA | Direction | Primer sequences

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| miR-301a

inhibitor | - |

GCUUUGACAAUACUAUUGCACUG |

| Inhibitor NC | - |

UCUACUCUUUCUAGGAGGUUGUGA |

| miR-301a

mimics | S |

CAGUGCAAUAGUAUUGUCAAAGC |

|

| AS |

GCUUUGACAAUACUAUUGCACUG |

| Mimics NC | S |

UCACAACCUCCUAGAAAGAGUAGA |

|

| AS |

UCUACUCUUUCUAGGAGGUUGUGA |

Observation of cell morphology

After 24 and 48 h of culture under normoxic or

hypoxic conditions, the morphological changes of PC cells (AsPC-1,

BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1) were examined using an

inverted light microscope (brightfield mode). Images of cells were

captured at ×20 magnification.

Western blotting

AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells

were used to assess HIF-1α protein expression under normoxic and

hypoxic conditions. MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells were used

to evaluate the expression levels of ACSL4 protein after

overexpression of miR-301a. MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells were

utilized to assess the expression levels of ACSL4 protein following

the knockdown of miR-301a. Protein extraction and quantification:

Collected cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no. BL1321A;

Biosharp Life Sciences) supplemented with 1% PMSF (cat. no.

BL1426A; Biosharp Life Sciences) on ice for 15 min. The lysates

were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the

supernatants were collected. The protein concentrations were

determined using a BCA assay kit (cat. no. SW201-02; Seven

Biotech). For western blot analysis, 20 µg of protein was resolved

by 7.5% SDS-PAGE using the Colour PAGE Gel Rapid Preparation Kit

(cat. no. PG111; Shanghai Epizyme Biopharmaceutical Technology Co.,

Ltd.; Ipsen Pharma) and transferred to PVDF membranes (cat. no.

IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma). Each membrane was then blocked in 10%

skim milk at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, anti-HIF-1α

(1:500; cat. no. 610958; BD Biosciences), anti-ACSL4 (1:2,000; cat.

no. ab155282; Abcam) and anti-β-actin antibodies (1:4,000; cat. no.

60008; Proteintech Group, Inc.) were added and incubated on a

shaker at 4°C overnight. The membranes were incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-labelled mouse (1:5,000; cat. no. PR30012;

Proteintech Group, Inc.)/rabbit (1:5,000; cat. no. PR30011;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) secondary antibodies at room temperature

for 1 h. Lastly, a high-sensitivity ECL detection reagent

(Ultrasensitive ECL Detection Kit; cat. no. PK10003; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) was used for visualization of the protein signals and

imaged with the Chemiluminescence Imaging System (ChemiDoc MP;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Tanon 5200 Multi; Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) analysis

FreeZol Reagent (cat. no. R711-01; Vazyme Biotech

Co., Ltd.) was used to extract the total RNA from human pancreatic

cancer cell lines (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1)

according to the instructions, and the RNA concentration was

determined and reverse transcribed following the manufacturer's

protocol (Evo M-MLV RT Kit for qPCR; cat. no. AG11707; Hunan

Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) into complementary DNA (cDNA),

which was then amplified using cDNA as a template. Specific RT-qPCR

experiments were performed to detect miR-301a expression using a

universal high-specificity miRNA quantitative PCR kit (MonAmp™

miRNA Universal Super Specificity qPCR Mix; cat. no. MQ00901; Monad

Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

following thermocycling conditions were performed: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec and combined annealing/extension at

60°C for 30 sec (two-step PCR). U6 was used as an internal

reference and the relative expression was calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (35). All

RT-qPCR primers were designed against Homo sapiens (human)

genes and synthesized by Anhui General Bioscience. The primer

sequences are listed in Table

III.

| Table III.RT-qPCR primer sequences. |

Table III.

RT-qPCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer

use/direction | Primer sequences

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| miR-301a | RT primer |

GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGAC[GCTTTG] |

| miR-301a | Forward |

GCCAGTGCAATAGTATTGTCAAAG |

| miR-301a | Reverse |

GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT |

| U6 | Forward |

CGCTTCGGCAGCACATATAC |

| U6 | Reverse |

CAGGGGCCATGCTAATCTT |

Cytotoxicity assay

AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells

were used to validate the hypoxic effect on gemcitabine resistance.

The MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1 and BxPC-3 and cells were used to validate

the effect of miR-301a on gemcitabine resistance. After the cells

were transfected with the miR-301a inhibitor for 24 h, they were

digested with trypsin and resuspended in a 96-well plate

(5×103 cells/well). After 6 h of adherence, the GEM drug

(Eli Lilly and Company) at various concentrations (0–50 µΜ; 0 µΜ as

the control group) was added. At 48 h after drug addition, the

original culture medium was discarded and fresh medium containing

10% Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. GK10001; GLPBIO Technology

LLC) was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1

h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader

to calculate the cell viability. Cell viability=[(As-Ab)/(Ac-Ab)]

×100% [As, experimental wells (containing cells, medium, CCK-8

solution and drug solution); Ac, control wells (containing cells,

medium and CCK-8 solution, but not containing drugs); Ab, blank

wells (containing medium and CCK-8 solution, but not containing

cells and drugs)].

Isolation and identification of

exosomes

The PANC-1 cells were used for the isolation and

identification of exosomes.

Extraction and identification of

exosomes using ultracentrifugation

Supernatants from cells treated under hypoxic and

normoxic conditions were collected, filtered through a 0.22 µm

filter and transferred into 50 ml centrifuge tubes. The tubes were

centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the cells. The

resulting supernatants were centrifuged at 4°C and 3,000 × g for 30

min to eliminate cellular debris. The clarified supernatants were

transferred into ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at, 10,000 ×

g for 40 min at 4°C. The supernatants from this step were

subsequently transferred into new ultracentrifuge tubes and

centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 2 h. After

ultracentrifugation, the supernatants were discarded and the

precipitate was resuspended in 100 ul PBS (cat. no. BL302A;

Biosharp Life Sciences) to obtain exosomes. The isolated exosomes

were stored at −80°C for subsequent experiments.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to

observe the morphology and size of the exosomes, with the sample

preparation steps as follows: Exosome pellets were first fixed with

2.5% glutaraldehyde (in 0.1 M PBS, Ph 7.4) at 4°C for 1 h, then

post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide at 4°C for 2 h. After

dehydration using gradient concentrations of ethanol (50, 70, 90

and 100%), the samples were embedded in Epon 812 epoxy resin and

incubated at room temperature overnight, before being cut into

70–100 nm ultrathin sections. The sections were then stained with

2% uranyl acetate at room temperature for 10 min, followed by 2%

lead citrate at room temperature for 10 min. Nanoparticle tracking

analysis (NTA) was used to detect the distribution of exosome

sizes.

Exosome uptake experiment

The hypoxia-derived exosome pellet was resuspended

in PBS and labelled with the membrane phospholipid dye PKH67

(green; cat. no. PKH67GL-1KT; MilliporeSigma) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Exosomes were incubated with 4 µl of PKH67

at room temperature for 5 min and the reaction was terminated by

adding 10% FBS. Unbound dye was removed by ultracentrifugation at

100,000 × g at 4°C for 2 h and labelled exosomes were resuspended

in serum-free DMEM. Normoxic PC cells were treated with

PKH67-labelled hypoxic exosomes for 12 h at 37°C. Following

co-culture, the cells were fixed at room temperature and stained

with DAPI (cat. no. C1002; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at

room temperature for 5 min to visualize the cell nuclei. Images of

the stained samples were captured under a laser confocal

microscope.

Bioinformatics analysis

TargetScan (targetscan.org/vert_80/) and starBase

(rnasysu.com/encori/) databases were used to predict the binding

sites between miRNAs and the target genes. TargetScan relies on

conserved seed matches in the 3′-UTR of genes annotated in RefSeq

and University of California, Santa Cruz genome alignments.

StarBase integrates 2,725 cross-linking and immunoprecipitation

(CLIP)-seq datasets [e.g., photoactivatable

ribonucleoside-enhanced-CLIP, a modified CLIP technique that uses

photoactivatable nucleosides to improve the accuracy of mapping

RNA-protein interaction sites; and high-throughput sequencing-CLIP,

an early CLIP derivative that combines cross-linking

immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing to identify

genome-wide RNA targets of RNA-binding proteins] and 100

degradome-seq datasets to prioritize experimentally supported

miRNA-target interactions.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.0; Dotmatics) was used

for statistical analysis and plotting. All the experiments were

repeated three times. The quantitative data that conformed to a

normal distribution are expressed as the means ± SE. An unpaired

t-test was used for comparisons between two groups. For >2

groups one-way ANOVA was conducted first, followed by two post-hoc

tests based on comparison goals: Tukey's honestly significant

difference test for pairwise comparisons among all groups (to

detect differences between every pair of groups), and Dunnett's

test for pairwise comparisons between each experimental group and

the control group (to focus on control-centred differences and

reduce type I errors). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

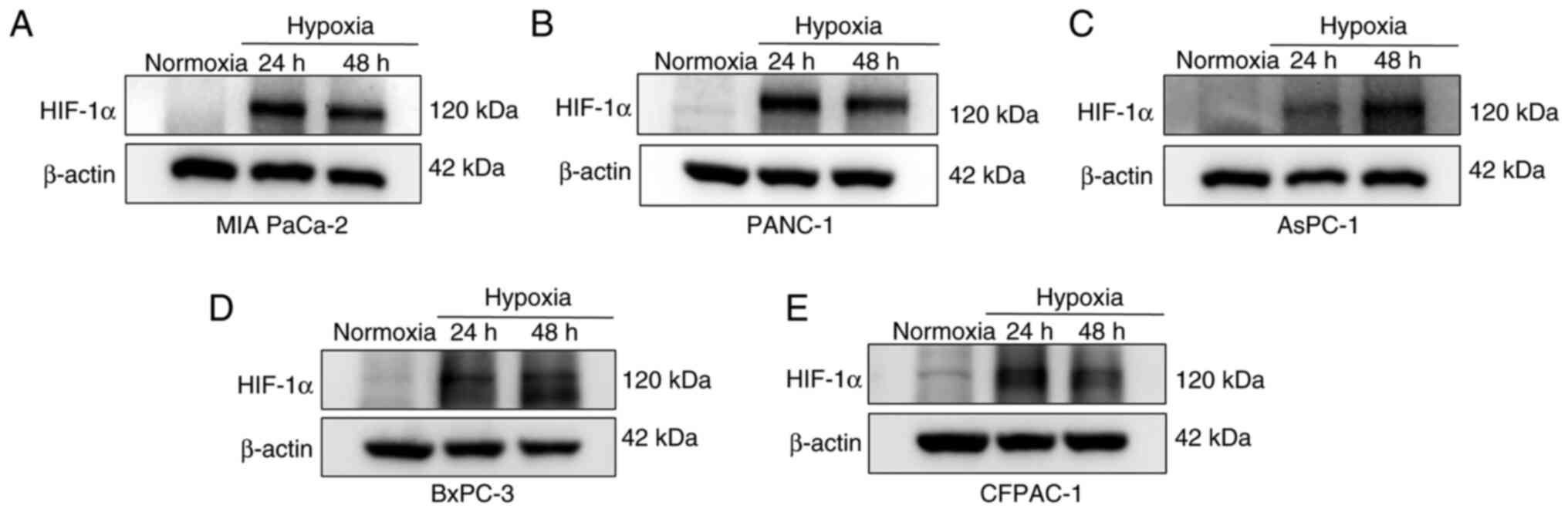

Hypoxia induces a substantial

accumulation of HIF-1α in PC cells

A physically hypoxic environment was used to

establish a hypoxic model. PC cells (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA

PaCa-2 and PANC-1) were cultured under hypoxic conditions for 24

and 48 h, with normoxic conditions serving as the baseline.

Detection of basal HIF-1α under normoxia serves two key purposes:

i) Baseline control to establish the natural expression level of

HIF-1α in oxygen-rich conditions, as even low, non-inducible HIF-1α

levels can occur in certain cell types (such as HCT116, human

colorectal cancer cells and CFPAC-1 cells) under normoxia (36); and ii) hypoxia model validation, by

comparing normoxic and hypoxic samples, the present study confirmed

that observed HIF-1α upregulation was hypoxia-induced and not an

experimental artifact. Western blotting was used to detect the

expression levels of HIF-1α protein in PC cells under normoxic and

hypoxic conditions. Compared with the results under normoxia, there

was a notable accumulation of HIF-1α protein in the PC cell lines

after 24 and 48 h under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1). Notably, HIF-1α accumulation

exhibited notable cell line-specific dynamics: BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA

PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells displayed marked HIF-1α induction at 24 h,

with levels plateauing or decreasing marginally by 48 h. AsPC-1

cells represented an outlier, with HIF-1α expression increasing

from 24 to 48 h.

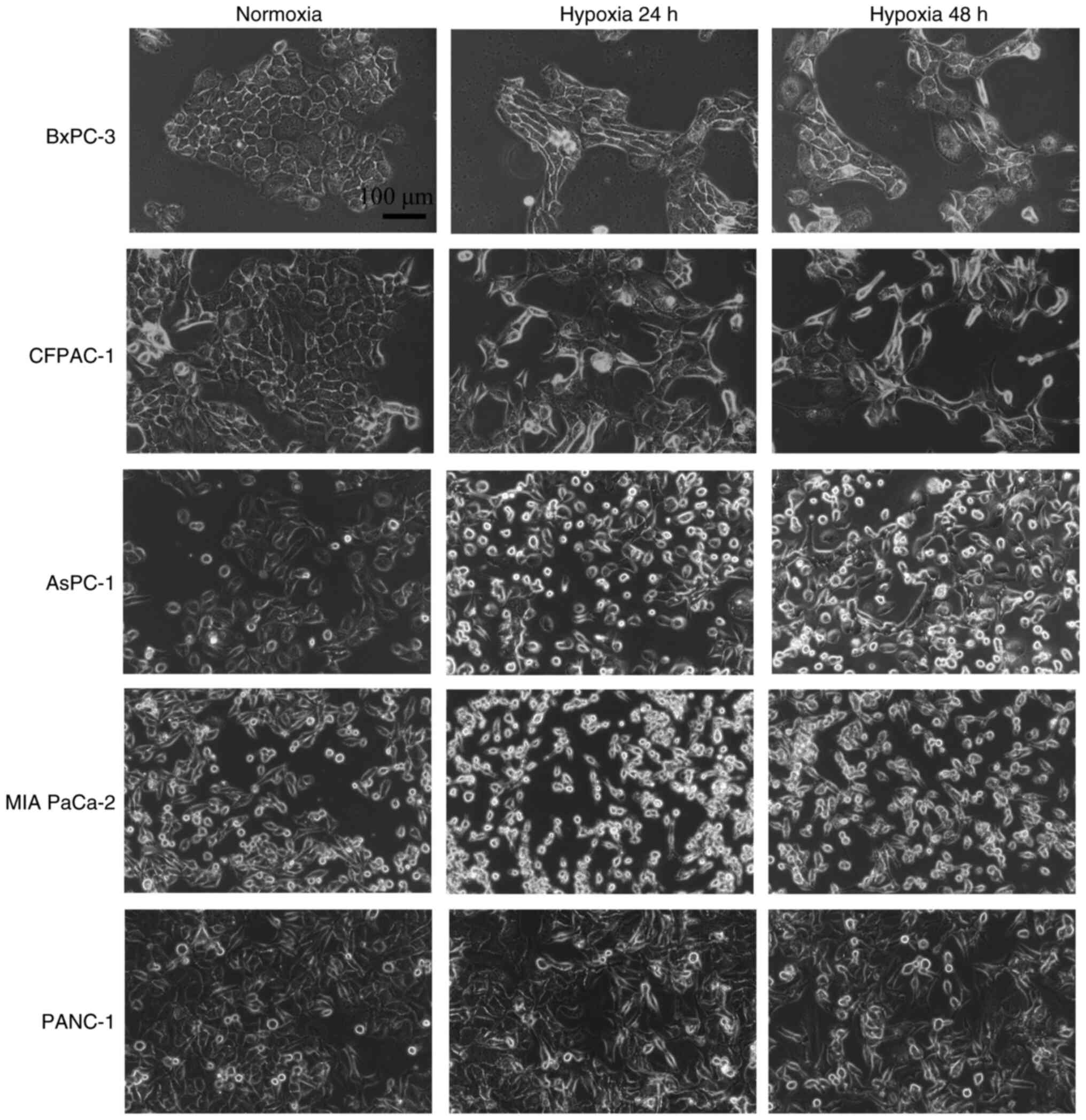

Morphological changes in PC cells

under hypoxic conditions

PC cells (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and

PANC-1) were cultured under normoxic conditions or hypoxic

conditions for 24 and 48 h and their morphologies were examined

under an inverted microscope. Compared with the normoxic state

observations, the BxPC-3 and CFPAC-1 cells under hypoxic conditions

displayed notable morphological changes characterized by a shift

from an epithelial morphology (oval shape with indistinct cell

boundaries) to a mesenchymal morphology (a spindle-shaped

morphology with well-defined cell margins). By contrast, AsPC-1,

MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells presented minimal morphological

alterations under hypoxia. While AsPC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells

occasionally demonstrated subtle cellular rounding or cytoplasmic

vacuolization at 48 h, potentially reflecting hypoxic stress or

early apoptotic changes, these changes did not represent a fully

mesenchymal phenotype and lacked the elongated, spindle-shaped

morphology observed in BxPC-3 and CFPAC-1 cells (Fig. 2).

Hypoxia upregulates the expression

levels of miR-301a and enhances GEM resistance in PC cells

The expression level of miR-301 was detected through

RT-qPCR experiments, which revealed that miR-301a in PC cells under

hypoxic conditions was significantly upregulated compared with that

in the normoxic group (Fig. 3A-E).

Notably, MIA PaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cells presented a unique temporal

pattern of miR-301a expression. Under hypoxia, the miR-301a levels

significantly increased at 24 h [1.4-fold in MIA PaCa-2 cells

(P<0.01) and 1.8-fold in BxPC-3 cells (P<0.001; Fig. 3A and D). However, by 48 h, the

expression had declined to baseline levels.

![Hypoxia upregulates the expression

levels of miR-301a and enhances GEM resistance in PC cells. (A-E)

Relative expression levels of miR-301a in PC cell lines [(A) MIA

PaCa-2, (B) PANC-1, (C) AsPC-1, (D) BxPC-3 and (E) CFPAC-1] were

detected using RT-qPCR following culture under normoxia conditions

and hypoxic conditions for 24 and 48 h. (F-J) Cell viability of PC

cells [(F) MIA PaCa-2, (G) PANC-1, (H) BxPC-3, (I) AsPC-1 and (J)

CFPAC-1] in both hypoxic and normoxic treatment groups was measured

using CCK-8 cytotoxicity assays upon exposure to various

concentrations of GEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. NO, normoxic; HO, hypoxic; PC, pancreatic cancer;

miR, microRNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; GEM, gemcitabine; CFPAC-1, cystic

fibrosis pancreatic adenocarcinoma; AsPC-1, ascites pancreatic

cancer 1; MIA PaCa-2, malignant inflammatory adenocarcinoma

pancreatic carcinoma-2.](/article_images/ol/30/6/ol-30-06-15352-g02.jpg) | Figure 3.Hypoxia upregulates the expression

levels of miR-301a and enhances GEM resistance in PC cells. (A-E)

Relative expression levels of miR-301a in PC cell lines [(A) MIA

PaCa-2, (B) PANC-1, (C) AsPC-1, (D) BxPC-3 and (E) CFPAC-1] were

detected using RT-qPCR following culture under normoxia conditions

and hypoxic conditions for 24 and 48 h. (F-J) Cell viability of PC

cells [(F) MIA PaCa-2, (G) PANC-1, (H) BxPC-3, (I) AsPC-1 and (J)

CFPAC-1] in both hypoxic and normoxic treatment groups was measured

using CCK-8 cytotoxicity assays upon exposure to various

concentrations of GEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. NO, normoxic; HO, hypoxic; PC, pancreatic cancer;

miR, microRNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; GEM, gemcitabine; CFPAC-1, cystic

fibrosis pancreatic adenocarcinoma; AsPC-1, ascites pancreatic

cancer 1; MIA PaCa-2, malignant inflammatory adenocarcinoma

pancreatic carcinoma-2. |

CCK-8 cytotoxicity assays were employed to measure

the cell viability in both the hypoxic and normoxic treatment

groups following their exposure to various concentrations of GEM.

The results (Fig. 3F-J) revealed

that the cell viability of the hypoxic treatment group was

significantly greater compared with that of the normoxic group at

different concentrations (P<0.05).

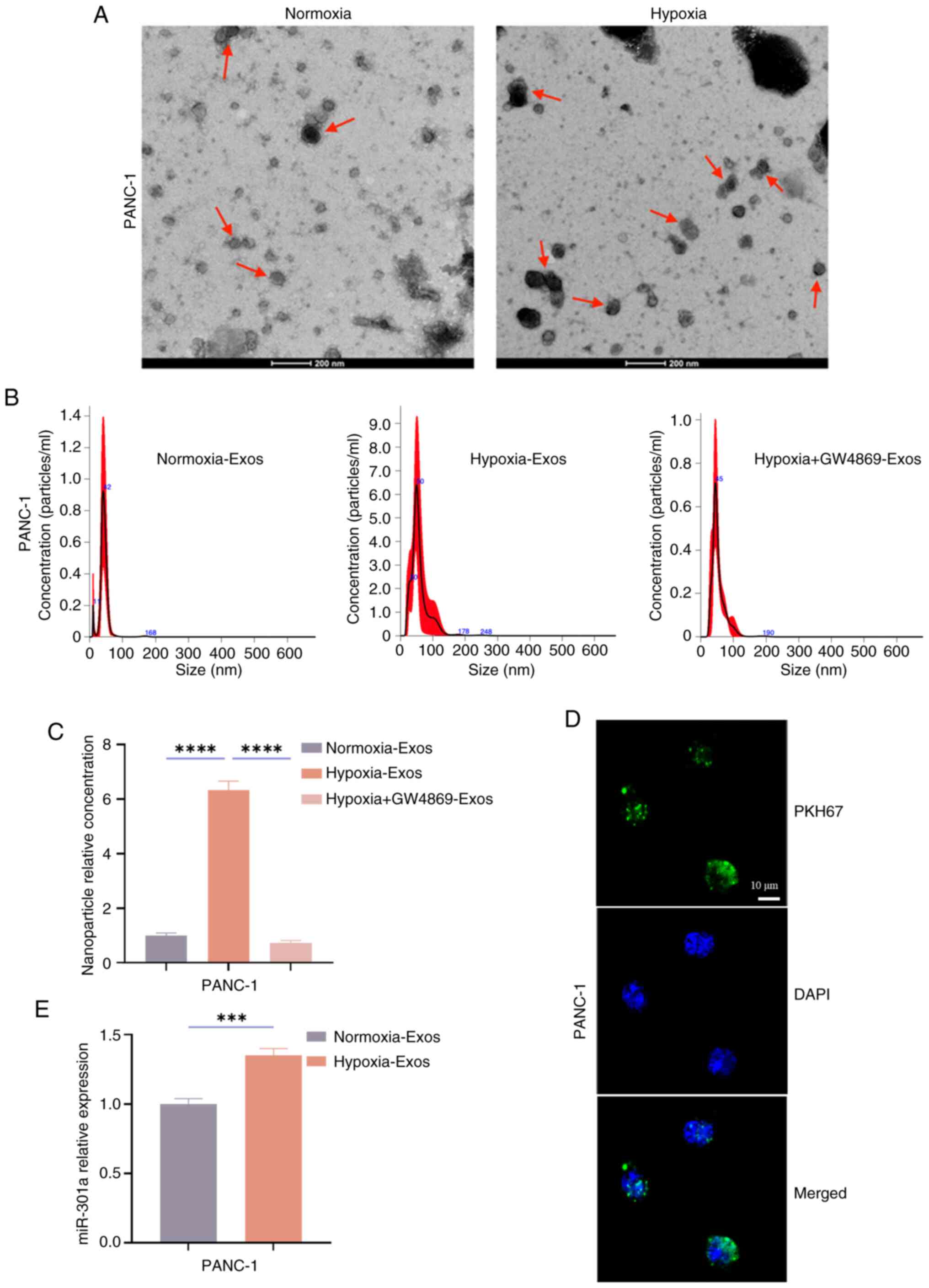

Hypoxia increases the number of

exosomes and facilitates their transfer to normoxic cells

After the hypoxia model was established, PANC-1

cells were selected for exosome experiments due to their robust

miR-301a upregulation under hypoxia. As shown in Fig. 3B, PANC-1 cells exhibited a 2.18-fold

increase in miR-301a expression at 48 h compared with normoxia

(P<0.0001), which makes PANC-1 cells ideal for modelling

exosome-mediated miR-301a transfer. Equal numbers of PANC-1 cells

were cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions for 48 h.

Exosomes from the supernatants of normoxic and hypoxic PANC-1 cells

were collected and identified. TEM was used to observe the

morphology of the isolated exosomes, which revealed that both

normoxic and hypoxic PANC-1-derived exosomes exhibited a

characteristic cup-shaped double-layered membrane structure

(Fig. 4A). NTA was used to analyse

the size distribution of the exosomes and the findings revealed

that the concentration of exosome particles in the ‘Hypoxia-Exos’

group was significantly greater compared with that in the

‘Normoxia-Exos’ group (P<0.0001) and that this secretion could

be inhibited (P<0.0001) by the exosome inhibitor GW4869

(Fig. 4B and C).

| Figure 4.Hypoxia induces an increase in

exosomes and facilitates their transfer to normoxic cells. (A) The

exosomes from PANC-1 cells cultured under normoxic and hypoxia

condition for 48 h were collected and their morphology was observed

by TEM; red arrows indicate the exosomes (scale bar, 200 nm). (B

and C) PANC-1 cells were cultured under normoxic and hypoxia

condition for 48 h and exosome inhibitor GW4869 was added to

hypoxia culture, exosomes were collected and NTA was used to

analyse the relative particle concentration in the Normoxia-Exos,

Hypoxia-Exos and Hypoxia + GW4869-Exos group. (D) Hypoxic

PANC-1-derived exosomes were collected and labelled with the

membrane phospholipid dye PKH67. After co-culture with normoxic

PANC-1 cells for 12 h, laser confocal microscopy was employed to

observe the endocytosis of labelled exosomes by normoxic PANC-1

cells (scale bar, 10 µm). (E) Following co-culturing the collected

normoxic and hypoxic-derived exosomes with normoxic PANC-1 cells

for 24 h, RT-qPCR was performed to detect the relative expression

level of the miR-301a. ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. TEM,

transmission electron microscopy; NTA, nanoparticle tracking

analysis; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; miR,

microRNA. |

To investigate intercellular exosome transfer,

hypoxic PANC-1-derived exosomes were labelled with the membrane dye

PKH67 and co-cultured with normoxic PANC-1 recipient cells for 12

h. Laser confocal microscopy demonstrated that hypoxic-derived

exosomes could be endocytosed by normoxic PANC-1 cells (Fig. 4D). After the collected normoxic and

hypoxic-derived exosomes were co-cultured with normoxic PANC-1

cells for 24 h, RT-qPCR was performed to detect the relative

expression level of the miR-301a gene. The results revealed that

the expression levels of miR-301a in the hypoxic Exos-treated group

was significantly greater compared with that in the Normoxic

Exos-treated group (P<0.001; Fig.

4E). These results indicated that hypoxia induces an increase

in the number of exosomes and facilitates the transfer of a large

amount of miR-301a to normoxic cells.

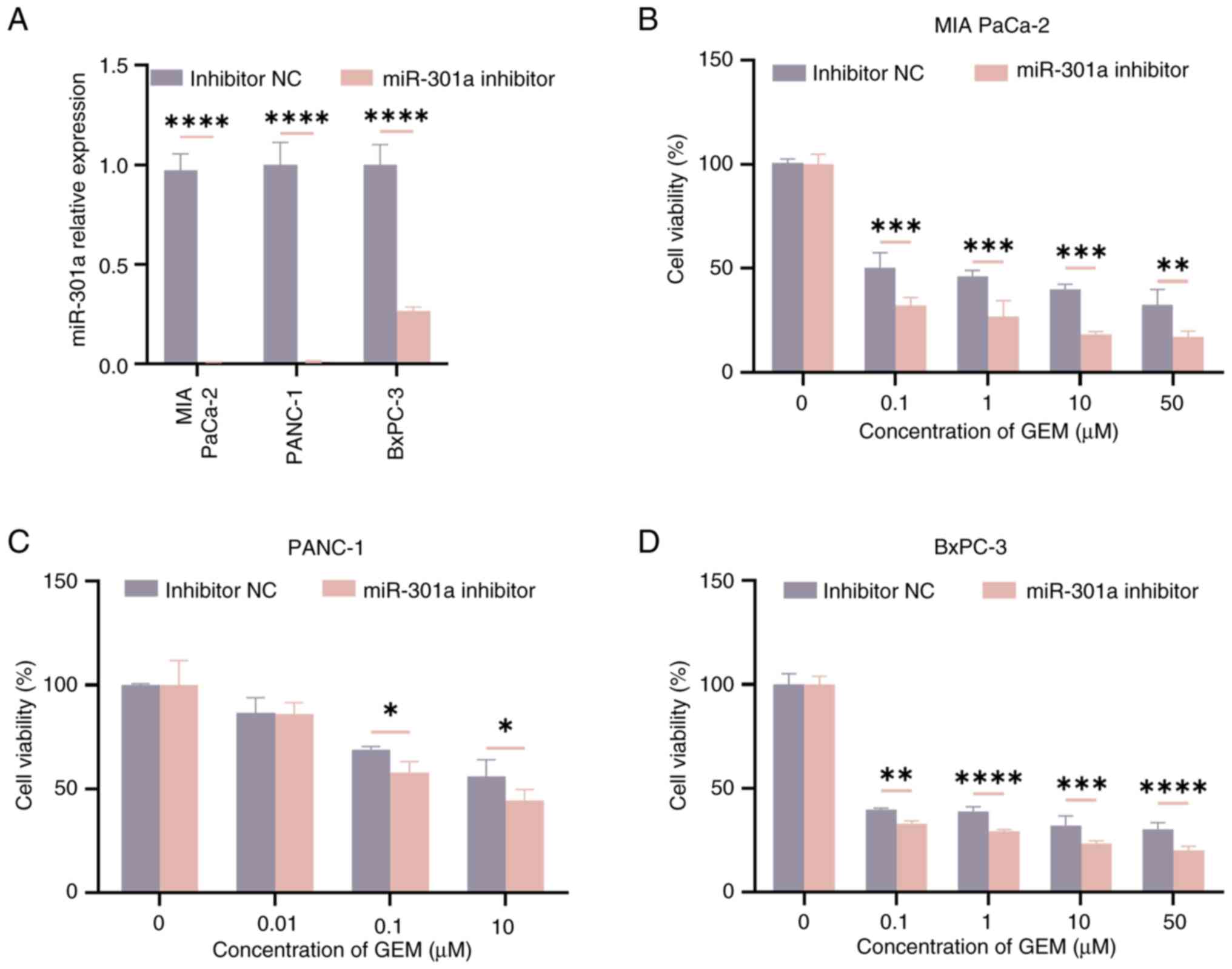

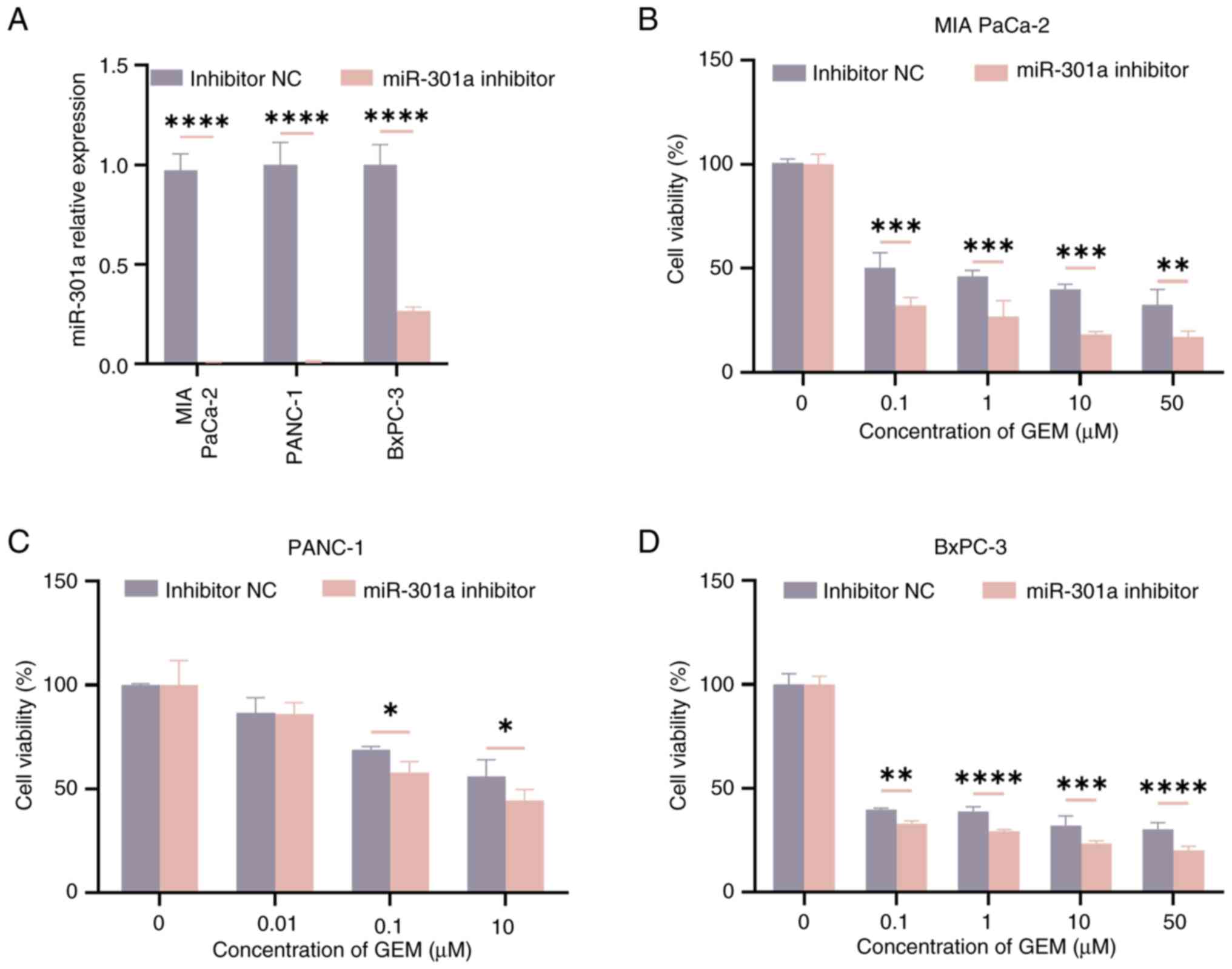

Effect of miR-301a on GEM resistance

in PC cells under normoxia

To explore the effect of hypoxia-derived exosomal

miR-301a on normoxic PC cells, a miR-301a inhibitor was transfected

into PC cells. Due to their high basal expression of miR-301a, MIA

PaCa-2, PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells were selected for these experiments

and RT-qPCR was used to verify the knockdown efficiency of

miR-301a. The results demonstrated that the knockdown efficiency of

miR-301a in the three cell lines was >70% (P<0.05; Fig. 5A). Subsequently, CCK-8 cytotoxicity

assays were performed to detect the resistance of PC cells to GEM

in both the inhibitor NC group and the miR-301a inhibitor group.

Notably, the GEM concentration gradients in Fig. 5B-D were tailored to the drug

sensitivity of each cell line, as determined by preliminary

dose-response experiments. The results indicated that, when the

cells were treated with different drug concentrations, the

viability of the cells in the miR-301a inhibitor group was lower

compared with that of the cells in the inhibitor NC group

(P<0.05; Fig. 5B-D).

| Figure 5.Regulatory mechanism of

hypoxia-derived exosome miR-301a on GEM resistance in normoxic PC

cells. (A) PC cells were transfected with inhibitor NC and miR-301a

inhibitor for 24 h and then the relative expression level of

miR-301a was detected by RT-qPCR. (B) MIA PaCa-2, (C) PANC-1, and

(D) BxPC-3 cells were treated with a gradient concentration of GEM

for 48 h. CCK-8 cytotoxicity assays were conducted to detect cell

viability in both the inhibitor NC group and the miR-301a inhibitor

group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001.

GEM, gemcitabine; miR, microRNA; PC, pancreatic cancer; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC, negative control;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8. |

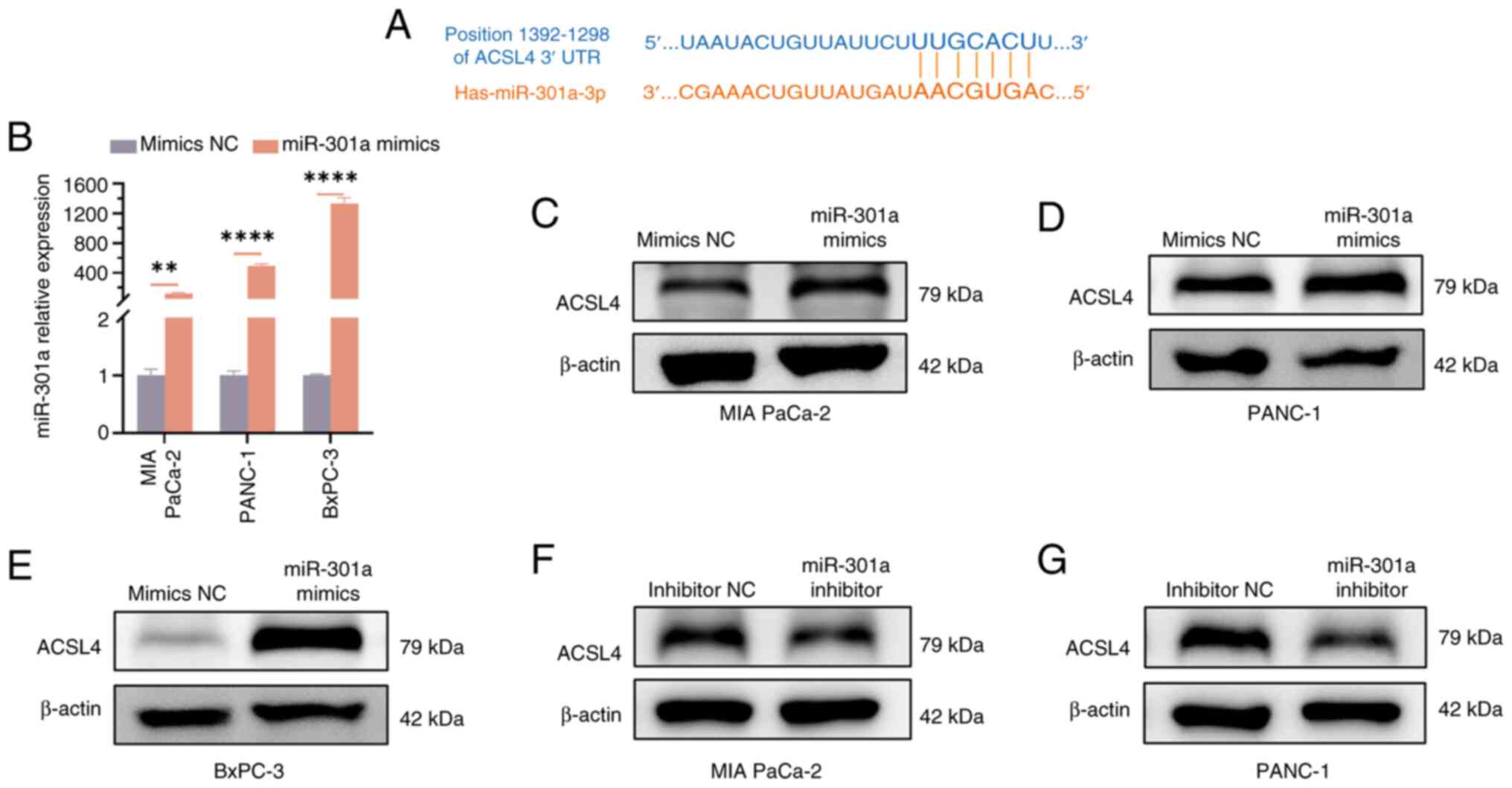

Regulatory mechanism of

hypoxia-derived exosomal miR-301a on GEM resistance in normoxic PC

cells

It has been reported that ACSL4 is associated with

GEM resistance (33). Further

bioinformatics analysis revealed a potential binding site between

miR-301a and ACSL4 (Fig. 6A). To

determine whether GEM resistance in PC cells is enhanced by

miR-301a through the regulation of ACSL4 expression, miR-301a

mimics were first transfected into PC cells and the effect of

miR-301a overexpression was verified using RT-qPCR. The results

revealed that the expression levels of miR-301a were significantly

increased in all three studied PC cell lines (P<0.05; Fig. 6B). Furthermore, western blotting

results indicated that when the expression level of miR-301a was

upregulated, the protein expression level of ACSL4 also increased

significantly (Fig. 6C-E).

Conversely, when miR-301a expression was inhibited, the ACSL4

protein level decreased markedly (Fig.

6F and G). These results suggested that hypoxia-derived

exosomal miR-301a further influences the GEM resistance of PC cells

by regulating the expression level of ACSL4 under normoxic

conditions.

Discussion

PC is a highly malignant tumour of the digestive

system, with persistently high incidence and mortality rates. As a

first-line chemotherapy drug for PC, GEM has been widely used in

clinical practice, yet the emergence of drug resistance has notably

limited its efficacy (8,37). In recent years, the role of the TME,

especially the hypoxic microenvironment, in tumour chemotherapy

resistance has attracted increasing attention (38). Previous studies have reported that

the hypoxic microenvironment increases glucose metabolism and

pyrimidine synthesis in tumour cells by inducing the upregulation

of HIF-1α, thereby leading to the resistance of PC cells to GEM

(39). Yoo et al (40) reported that hypoxia can also

regulate metabolic reprogramming through HIF-2α-mediated generation

of SLC1A5 variants, further enhancing the resistance of PC cells to

GEM. In the present study, a hypoxic model for PC cells was

established using physical hypoxia and the effectiveness of the

model was validated by detecting the level of HIF-1α protein.

Compared with that under normoxia, the protein level of HIF-1α was

markedly elevated after hypoxia treatment for 24 and 48 h.

Additionally, morphological changes in PC cells were observed under

hypoxic conditions. Further evaluation of cytotoxicity through

CCK-8 assays revealed that hypoxia treatment significantly reduced

the sensitivity of PC cells to GEM, which was consistent with

previously reported findings that hypoxia promoted chemotherapy

resistance in tumours (41).

Exosomes can carry various bioactive molecules, such

as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (for example, mRNAs, miRNAs),

and participate in intercellular communication and material

exchange. In various disease models, hypoxic stimulation not only

leads to an increase in the secretion of exosomes but also causes

alterations in their contents, which further affects the biological

effects on recipient cells. For example, in pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumours (17) and

chondrosarcomas (18,42), the hypoxic microenvironment induces

the production of several exosomes (such as carcinoembryonic

antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5, long non-coding RNA RAMP2

antisense RNA 1) by cells, resulting in M2 polarization of

tumour-associated macrophages, which in turn promotes tumour

invasion and metastasis. Furthermore, Liu et al (19) reported that the number of exosomes

derived from hypoxic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells increased

and could enhance fracture healing.

Exosomes released by tumour cells serve key roles in

tumour progression and drug resistance, particularly through their

small RNA molecules, such as miRNAs, which can regulate the

expression levels of target genes and influence the biological

characteristics of cells. Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun were

awarded the Nobel Prize in 2024 for their discovery of miRNAs and

their role in post-transcriptional gene regulation (43), which underscores the importance of

miRNAs in intercellular communication and gene expression

regulation and provides a theoretical foundation for the present

study experiments. Zhao et al (44) demonstrated that exosomal miR-934 can

induce M2 polarization of macrophages, thereby promoting liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. Furthermore, exosomal miR-522

secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumour

microenvironment is involved in chemotherapy resistance in gastric

cancer (45). Through a literature

review, it was found that miR-301a is differentially expressed in a

variety of malignant tumours and affects tumorigenesis and

development through different regulatory mechanisms. A previous

study has demonstrated that miR-301a is abnormally upregulated in

breast cancer and further promotes breast cancer cell

proliferation, metastasis, and cell cycle progression through the

cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1/sirtuin

1/Sox2 axis, accelerating the malignant progression of breast

cancer (21). Furthermore, miR-301a

can promote the proliferation of prostate cancer cells by

inhibiting the expression of p21 and SMAD4 (46). Qi et al (47) demonstrated that miR-301a is highly

expressed in PC. Rather than verifying or further exploring the

differential expression and regulatory mechanisms of miR-301a

itself, the present study focused on the impact and underlying

mechanisms of exosomal miR-301a on GEM drug resistance in PC under

hypoxic conditions, which aimed to provide a novel strategy for PC

treatment. These results indicated that the hypoxic

microenvironment markedly enhanced the resistance of PC cells to

GEM, accompanied by a marked increase in exosome secretion and

notable upregulation of miR-301a expression. Notably, MIA PaCa-2

and BxPC-3 cells presented a unique temporal pattern of miR-301a

expression. Under hypoxia, miR-301a levels increased significantly

at 24 h. However, by 48 h, expression had declined to baseline

levels. A literature review revealed that HIF-2α can regulate the

expression levels of miR-301a in PC cells under hypoxic conditions

(48). Furthermore, compared with

that in the 24 h hypoxic treatment, the protein level of HIF-2α

decreases at 48 h of hypoxic treatment. Therefore, it can be

hypothesized that the upregulation of miR-301a expression in MIA

PaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cell lines at 24 h and its downregulation at 48 h

are due to the regulation of HIF-2α. Our research group previously

reported that miR-301a expression was markedly increased in hypoxic

exosomes (25). Using exosome

co-culture experiments, it was verified that the number of

hypoxia-induced exosomes increased and that these exosomes could be

delivered to normoxic PC cells. To explore the role of exosomal

miR-301a, miR-301a knockdown experiments were conducted and the key

role of miR-301a in the resistance of PC to GEM was confirmed.

Compared with the NC group, miR-301a knockdown markedly reduced the

resistance of normoxic PC cells to GEM. These findings suggested

that the upregulation of miR-301a in hypoxic-derived exosomes is

one of the key mechanisms underlying GEM resistance in normoxic PC.

According to previous studies, miRNAs primarily act by binding to

the 3′-UTR of mRNAs, inducing mRNA degradation or inhibiting their

translation, thereby downregulating the expression of target genes.

In certain cases, they bind to the 5′-UTRs of mRNAs to positively

regulate target genes.

Previous studies have reported that miRNAs can

participate in disease progression by targeting and regulating

ACSL4 expression. For example, miR-23a-3p inhibits ferroptosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting ACSL4, thereby participating

in the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib

(31). Shi et al (32) reported that miR-20a-5p alleviates

renal ischaemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting ACSL4 expression.

Other studies have demonstrated that ACSL4 is also involved in PC

resistance to GEM, but the specific mechanism has not been fully

elucidated (33,49). In the present study, using

bioinformatics analysis, potential binding sites between miR-301a

and ACSL4 were identified, which led to the hypothesis that

miR-301a acts by binding to the 3′-UTR of ACSL4 mRNA. However,

validation experiments revealed that miR-301a overexpression

increased ACSL4 protein levels, whereas miR-301a knockdown

decreased ACSL4 expression, findings that contradict the

traditional negative regulatory pattern of miRNAs. It was

speculated that miR-301a might bind to the 5′-UTR of ACSL4 mRNA.,

but after consulting the bioinformatics databases, it was revealed

that there was no binding site for miR-301a on the 5′-UTR of ACSL4

mRNA. Based on these results, the present study proposes that

miR-301a may not directly target ACSL4 but instead it regulates

ACSL4 through an intermediate molecule, which provides a novel

direction for future research. Subsequent studies could focus on

identifying this potential intermediate molecule, with the aim of

uncovering novel therapeutic strategies and targets for PC and

other tumours.

In summary, a key mechanism was revealed in the

present study, whereby hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-301a is

transferred to normoxic PC cells via exosomes and contributes to

GEM resistance by regulating ACSL4. This finding not only provides

novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying GEM

resistance in PC but also offers potential targets for the

development of novel therapeutic strategies against PC in the

future. The specific interaction mechanism between miR-301a and

ACSL4, as well as potential treatment approaches targeting this

axis, remains to be explored in future research.

Notwithstanding the aforementioned findings, the

present study has certain limitations to note. First, the

intermediate molecule mediating miR-301a-induced regulation of

ACSL4 was not identified, leaving the exact regulatory cascade

unresolved. Second, in vivo validation using animal models

(such as orthotopic PC xenografts) is lacking, which limits the

translational relevance of the in vitro results. Finally, no

clinical specimens were analysed to determine the association of

miR-301a/ACSL4 expression with GEM response or patient outcomes,

thus hindering evaluation of their clinical potential as biomarkers

or targets. Addressing these limitations in future work will help

strengthen the clinical applicability of the current findings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Research Fund of Anhui

Institute of Translational Medicine (grant no. 2022zhyx-C71) and

the Graduate Scientific Research and Practice Innovation Project of

Anhui Medical University (grant no. YJS20230037).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WQ performed all cell culture, exosome isolation and

molecular biology experiments, including RT-qPCR, western blot and

CCK-8 assays. WQ conducted data analysis, prepared the initial data

summaries and drafted the manuscript. WaT conducted bioinformatics

prediction and analysis on the potential target genes of miR-301a,

and performed subsequent experimental validation using western

blotting, while MY provided key reagents, including PC cell lines

and exosome inhibitors and offered expertise in hypoxia modelling.

WeT and MY participated in data analysis and figure preparation.

WeT made substantial contributions to the analysis and

interpretation of experimental data (specifically verifying the

reliability of exosome isolation efficiency and miR-301a detection

data), revised the key intellectual content of the manuscript, and

reviewed the consistency of experimental descriptions and data

presentation. LZ designed and conducted supplementary experiments

(including CCK analysis for BxPC-3, AsPC-1 and CFPAC-1 cells

treated with GEM under normoxia/hypoxia) to address reviewer

feedback, obtained funding and helped respond to reviewers,

including clarifying methodologies and data interpretation. GL

conceived and designed the present study, supervised all

experimental work and interpreted the results, oversaw the overall

validation of data integrity and the accuracy of research outcomes.

GL revised the manuscript for intellectual content and ensured the

integrity of the data and the accuracy of the findings. WQ and GL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xiong Q, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Yang Y, Zhang Z,

Zhou Y, Zhang S, Zhou L, Wan X, Yang X, et al: tiRNA-Val-CAC-2

interacts with FUBP1 to promote pancreatic cancer metastasis by

activating c-MYC transcription. Oncogene. 43:1274–1287. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Munigala S, Almaskeen S, Subramaniam DS,

Bandi S, Bowe B, Xian H, Sheth SG, Burroughs TE and Agarwal B:

Acute pancreatitis recurrences augment long-term pancreatic cancer

risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 118:727–737. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Topal H, Aerts R, Laenen A, Collignon A,

Jaekers J, Geers J and Topal B: Survival after minimally invasive

vs open surgery for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JAMA Netw Open.

5:e22481472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Padrón LJ, Maurer DM, O'Hara MH, O'Reilly

EM, Wolff RA, Wainberg ZA, Ko AH, Fisher G, Rahma O, Lyman JP, et

al: Sotigalimab and/or nivolumab with chemotherapy in first-line

metastatic pancreatic cancer: Clinical and immunologic analyses

from the randomized phase 2 PRINCE trial. Nat Med. 28:1167–1177.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Li K, Tandurella JA, Gai J, Zhu Q, Lim SJ,

Thomas DL II, Xia T, Mo G, Mitchell JT, Montagne J, et al:

Multi-omic analyses of changes in the tumor microenvironment of

pancreatic adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant treatment with

anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Cell. 40:1374–1391. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu Y, Guo X, Xu P, Song Y, Huang J, Chen

X, Zhu W, Hao J and Gao S: Clinical outcomes of second-line

chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A

real-world study. Cancer Biol Med. 21:799–812. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Beutel AK and Halbrook CJ: Barriers and

opportunities for gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer therapy. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 324:C540–C552. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Patzak MS, Kari V, Patil S, Hamdan FH,

Goetze RG, Brunner M, Gaedcke J, Kitz J, Jodrell DI, Richards FM,

et al: Cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase 1A is overexpressed in pancreatic

cancer and mediates gemcitabine resistance by reducing

intracellular gemcitabine metabolites. EBioMedicine. 40:394–405.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P,

Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, Faluyi O, O'Reilly DA,

Cunningham D, Wadsley J, et al: Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine

and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with

resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): A multicentre, open-label,

randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 389:1011–1024. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hosein AN, Brekken RA and Maitra A:

Pancreatic cancer stroma: An update on therapeutic targeting

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:487–505. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wicks EE and Semenza GL: Hypoxia-inducible

factors: Cancer progression and clinical translation. J Clin

Invest. 132:e1598392022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mao Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Fu Z, Dong L and

Liu J: Hypoxia induced exosomal Circ-ZNF609 promotes pre-metastatic

niche formation and cancer progression via miR-150-5p/VEGFA and

HuR/ZO-1 axes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death

Discov. 10:1332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Song H, Qiu Z, Wang Y, Xi C, Zhang G, Sun

Z, Luo Q and Shen C: HIF-1α/YAP signaling rewrites glucose/iodine

metabolism program to promote papillary thyroid cancer progression.

Int J Biol Sci. 19:225–241. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang Q, Xiong L, Wei T, Liu Q, Yan L,

Chen J, Dai L, Shi L, Zhang W, Yang J, et al: Hypoxia-responsive

PPARGC1A/BAMBI/ACSL5 axis promotes progression and resistance to

lenvatinib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 42:1509–1523.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ye M, Lu F, Gu D, Xue B, Xu L, Hu C, Chen

J, Yu P, Zheng H, Gao Y, et al: Hypoxia exosome derived CEACAM5

promotes tumor-associated macrophages M2 polarization to accelerate

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors metastasis via MMP9. FASEB J.

38:e237622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hou SM, Lin CY, Fong YC and Tang CH:

Hypoxia-regulated exosomes mediate M2 macrophage polarization and

promote metastasis in chondrosarcoma. Aging (Albany NY).

15:13163–13175. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu W, Li L, Rong Y, Qian D, Chen J, Zhou

Z, Luo Y, Jiang D, Cheng L, Zhao S, et al: Hypoxic mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomes promote bone fracture healing by the transfer

of miR-126. Acta Biomater. 103:196–212. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang M, Zheng Y, Hao Q, Mao G, Dai Z, Zhai

Z, Lin S, Liang B, Kang H and Ma X: Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal

miR-210-3p promotes progression of triple-negative breast cancer

cells via NFIX-Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis. J Transl Med.

23:392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jia Y, Zhao J, Yang J, Shao J and Cai Z:

miR-301 regulates the SIRT1/SOX2 pathway via CPEB1 in the breast

cancer progression. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 22:13–26. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xia X, Wang S, Ni B, Xing S, Cao H, Zhang

Z, Yu F, Zhao E and Zhao G: Hypoxic gastric cancer-derived exosomes

promote progression and metastasis via MiR-301a-3p/PHD3/HIF-1α

positive feedback loop. Oncogene. 39:6231–6244. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Alves Â, Ferreira M, Eiras M, Lima L,

Medeiros R, Teixeira AL and Dias F: Exosome-derived

hsa-miR-200c-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p and hsa-miR-301a-3p as potential

biomarkers and therapeutic targets for restoration of PTEN

expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Biol Macromol.

302:1406072025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhong M, Huang Z, Wang L, Lin Z, Cao Z, Li

X, Zhang F, Wang H, Li Y and Ma X: Malignant transformation of

human bronchial epithelial cells induced by arsenic through

STAT3/miR-301a/SMAD4 loop. Sci Rep. 8:132912018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang X, Luo G, Zhang K, Cao J, Huang C,

Jiang T, Liu B, Su L and Qiu Z: Hypoxic tumor-derived exosomal

miR-301a mediates M2 macrophage polarization via PTEN/PI3K gamma to

promote pancreatic cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 78:4586–4598.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Luo G, Xia X, Wang X, Zhang K, Cao J,

Jiang T, Zhao Q and Qiu Z: miR-301a plays a pivotal role in

hypoxia-induced gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer. Exp

Cell Res. 369:120–128. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ding K, Liu C, Li L, Yang M, Jiang N, Luo

S and Sun L: Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: An essential target in

ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism. Chin Med J (Engl).

136:2521–2537. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Qiu Y, Wang X, Sun Y, Jin T, Tang R, Zhou

X, Xu M, Gan Y, Wang R, Luo H, et al: ACSL4-mediated membrane

phospholipid remodeling induces integrin β1 activation to

facilitate triple-negative breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res.

84:1856–1871. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen J, Ding C, Chen Y, Hu W, Yu C, Peng

C, Feng X, Cheng Q, Wu W, Lu Y, et al: ACSL4 reprograms fatty acid

metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma via c-Myc/SREBP1 pathway.

Cancer Lett. 502:154–165. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Grube J, Woitok MM, Mohs A, Erschfeld S,

Lynen C, Trautwein C and Otto T: ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis does

not represent a tumor-suppressive mechanism but ACSL4 rather

promotes liver cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 13:7042022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lu Y, Chan YT, Tan HY, Zhang C, Guo W, Xu

Y, Sharma R, Chen ZS, Zheng YC, Wang N and Feng Y: Epigenetic

regulation of ferroptosis via ETS1/miR-23a-3p/ACSL4 axis mediates

sorafenib resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 41:32022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Shi L, Song Z, Li Y, Huang J, Zhao F, Luo

Y, Wang J, Deng F, Shadekejiang H, Zhang M, et al: MiR-20a-5p

alleviates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting

ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis. Am J Transplant. 23:11–25. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Qi R, Bai Y, Li K, Liu N, Xu Y, Dal E,

Wang Y, Lin R, Wang H, Liu Z, et al: Cancer-associated fibroblasts

suppress ferroptosis and induce gemcitabine resistance in

pancreatic cancer cells by secreting exosome-derived

ACSL4-targeting miRNAs. Drug Resist Updat. 68:1009602023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Deer EL, González-Hernández J, Coursen JD,

Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, Firpo MA and Mulvihill SJ: Phenotype

and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas. 39:425–435.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li W, Zhou C, Yu L, Hou Z, Liu H, Kong L,

Xu Y, He J, Lan J, Ou Q, et al: Tumor-derived lactate promotes

resistance to bevacizumab treatment by facilitating autophagy

enhancer protein RUBCNL expression through histone H3 lysine 18

lactylation (H3K18la) in colorectal cancer. Autophagy. 20:114–130.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang L, Zhao S, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhao S,

Fang X and Zhang J: Hypoxic cancer-associated fibroblast exosomal

circSTAT3 drives triple negative breast cancer stemness via

miR-671-5p/NOTCH1 signaling. J Transl Med. 23:8142025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shukla SK, Purohit V, Mehla K, Gunda V,

Chaika NV, Vernucci E, King RJ, Abrego J, Goode GD, Dasgupta A, et

al: MUC1 and HIF-1alpha signaling crosstalk induces anabolic

glucose metabolism to impart gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Cell. 32:71–87. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yoo HC, Park SJ, Nam M, Kang J, Kim K, Yeo

JH, Kim JK, Heo Y, Lee HS, Lee MY, et al: A variant of SLC1A5 is a

mitochondrial glutamine transporter for metabolic reprogramming in

cancer cells. Cell Metab. 31:267–283. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ding J, Xie Y, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Ni B, Yan

J, Zhou T and Hao J: Hypoxic and acidic tumor

microenvironment-driven AVL9 promotes chemoresistance of pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma via the AVL9-IκBα-SKP1 complex.

Gastroenterology. 168:539–555. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cheng C, Zhang Z, Cheng F and Shao Z:

Exosomal lncRNA RAMP2-AS1 derived from chondrosarcoma cells

promotes angiogenesis through miR-2355-5p/VEGFR2 axis. Onco Targets

Ther. 13:3291–3301. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Organization NP, . Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine. 2024.https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2024/press–release/January

5–2025

|

|

44

|

Zhao S, Mi Y, Guan B, Zheng B, Wei P, Gu

Y, Zhang Z, Cai S, Xu Y, Li X, et al: Tumor-derived exosomal

miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1562020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, Ning T, Yang H,

Liu D, Zhang Q, Lin D, Ge S, Bai M, et al: CAF secreted miR-522

suppresses ferroptosis and promotes acquired chemo-resistance in

gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li X, Li J, Cai Y, Peng S, Wang J, Xiao Z,

Wang Y, Tao Y, Li J, Leng Q, et al: Hyperglycaemia-induced miR-301a

promotes cell proliferation by repressing p21 and Smad4 in prostate

cancer. Cancer Lett. 418:211–220. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Qi B, Wang Y, Zhu X, Gong Y, Jin J, Wu H,

Man X, Liu F, Yao W and Gao J: miR-301a-mediated crosstalk between

the Hedgehog and HIPPO/YAP signaling pathways promotes pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 26:24577612025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang KD, Hu B, Cen G, Yang YH, Chen WW,

Guo ZY, Wang XF, Zhao Q and Qiu ZJ: MiR-301a transcriptionally

activated by HIF-2α promotes hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal

transition by targeting TP63 in pancreatic cancer. World J

Gastroenterol. 26:2349–2373. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li J, Ma C, Cao P, Guo W, Wang P, Yang Y,

Ding B, Yin F, Li Z, Wang Y, et al: A CD147-targeted small-molecule

inhibitor potentiates gemcitabine efficacy by triggering

ferroptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep Med.

6:1022922025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Hypoxia upregulates the expression

levels of miR-301a and enhances GEM resistance in PC cells. (A-E)

Relative expression levels of miR-301a in PC cell lines [(A) MIA

PaCa-2, (B) PANC-1, (C) AsPC-1, (D) BxPC-3 and (E) CFPAC-1] were

detected using RT-qPCR following culture under normoxia conditions

and hypoxic conditions for 24 and 48 h. (F-J) Cell viability of PC

cells [(F) MIA PaCa-2, (G) PANC-1, (H) BxPC-3, (I) AsPC-1 and (J)

CFPAC-1] in both hypoxic and normoxic treatment groups was measured

using CCK-8 cytotoxicity assays upon exposure to various

concentrations of GEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. NO, normoxic; HO, hypoxic; PC, pancreatic cancer;

miR, microRNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; GEM, gemcitabine; CFPAC-1, cystic

fibrosis pancreatic adenocarcinoma; AsPC-1, ascites pancreatic

cancer 1; MIA PaCa-2, malignant inflammatory adenocarcinoma

pancreatic carcinoma-2.](/article_images/ol/30/6/ol-30-06-15352-g02.jpg)