Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignant

tumors among women and poses a significant threat to both health

and survival (1). In recent

decades, the burden of breast cancer has intensified in developing

countries due to rising incidence rates and persistently high

mortality (2). By 2040, it is

projected that population growth and aging alone will contribute to

>3 million new breast cancer cases and 1 million related deaths

annually (3). Current treatment

modalities include surgery, targeted therapies, immunotherapy,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy (4).

Among the chemotherapeutic agents, paclitaxel (PTX) plays a crucial

role in breast cancer management (5). However, the development of PTX

resistance during treatment remains a major clinical challenge,

often leading to therapeutic failure (6). Understanding the mechanisms underlying

PTX resistance and identifying effective reversal strategies is

therefore of great clinical importance.

Small breast epithelial mucin (SBEM) is a secreted

protein, the gene expression of which has been associated with

breast cancer prognosis (7).

Elevated SBEM expression has been linked to poorer clinical

outcomes, suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker

(8). Research indicates that SBEM

contributes to the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells

(9), potentially by regulating

extracellular matrix degradation, modulating cell adhesion and

altering the tumor microenvironment (10). However, the exact biological role of

SBEM in breast cancer remains unclear. SBEM has been identified as

a potential predictive biomarker for adjuvant chemotherapy in

breast cancer (11). PTX, a drug

frequently employed in combination chemotherapy regimens, still

faces limitations in its clinical application. This is due to

notable individual variations in drug sensitivities (5). To the best of our knowledge, no

studies have clearly revealed the association between SBEM and the

response to PTX, especially the role of SBEM in predicting PTX

sensitivity.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

signaling pathway plays a central role in the initiation,

progression and metastasis of breast cancer (12). Dysregulated MAPK activation promotes

tumor cancer cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis and

resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic agents (13), including PTX. Numerous studies have

confirmed that abnormal MAPK signaling is a key mechanism driving

PTX resistance (14–16). MAPK activity is primarily regulated

by a family of proteins known as dual-specificity phosphatases

(DUSPs) (17), also referred to as

MAPK phosphatases (MKPs), which are involved in signal

transduction, cell growth regulation and metabolism (18). Among this protein family, MKP7, also

known as dual specificity phosphatase 16 (DUSP16), is primarily

cytoplasmic and inhibits the activity of both p38 and JNK MAPKs

(19,20). DUSP16 also regulates ERK and p38MAP

activation and has been shown to influence AMPK signaling (21–23).

Additionally, abnormal DUSP16 expression is associated with

tumorigenesis, progression and metastasis (24). Despite this, the regulatory

relationship between SBEM and DUSP16 as well as their combined

influence on the AMPK signaling pathway remains largely

unexplored.

The primary objective of the present study was to

explore whether SBEM, by interacting with DUSP16 and activating the

AMPK signaling pathway, contributes to PTX resistance in patients

with breast cancer. Through a series of experiments and analyses,

the study aimed to determine if such a mechanism exists and leads

to the observed PTX resistance. This research also provides novel

insights into future treatment strategies and the improvement of

patient prognosis.

Materials and methods

Molecular docking

The 3D structure of the SBEM protein was predicted

using AlphaFold software 2 (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). PrankWeb (https://prankweb.cz/), a machine learning-based tool

employing a Random Forest algorithm trained on known binding sites,

was used to predict potential active sites (25). Through multi-sequence alignment

analysis using BioXM 2.7.1, MUCL1 (UniProt ID: Q96DR8) and MUCL3

(UniProt ID: Q3MIW9) were examined to identify conserved regions.

Subsequently, the 2D structure of the SBEM protein was analyzed

using PyMOL 2.5 (https://pymol.sourceforge.net). Briefly, based on the

protein structure confidence, 2D structure stability, active site

prediction and sequence alignment, Met1 was selected as the lattice

center and a docking box was established. The specific box

information was as follows: center_x=6.439; center_y=−0.223;

center_z=−12.452; size_x=73.15; size_y=73.15; and size_z=73.15. The

SDF format of PTX was obtained from the PubChem database

(https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and

converted to the PDB format using Open Babel (http://openbabel.org/index.html). The protein

structure was dehydrated, hydrogenated and its charge calculated

before being converted to the PDBQT format using AutoDockTools

1.5.7 (https://autodocksuite.scripps.edu/adt/). The ligand

was also hydrogenated, its torsional degrees of freedom were

determined and it was converted to the PDBQT format. The docking

box coordinates were defined and molecular docking was performed

using AutoDock Vina (https://vina.scripps.edu/). Visualization and 3D

analysis diagrams were generated using PyMOL 2.1.0.

Cell culture

Human breast cancer cell lines (SUM190PT, BT474,

AU565, SKBR3 and MCF7) and the normal mammary epithelial cell line

MCF10A were purchased from Qingqi (Shanghai) Biotechnology

Development Co., Ltd. All cell lines were authenticated by short

tandem repeat profiling to prevent cross-contamination. Cells were

thawed from liquid nitrogen, resuspended and cultured in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Beyotime Biotechnology; cat. no.

C0891) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Beyotime

Biotechnology; cat. no. C0235) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The

cells were placed in a cell incubator (Beyotime Biotechnology; cat.

no. E2392) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

Exponentially growing SUM190PT and SKBR3 cells were

treated with 2 ml trypsin digestion solution (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G4011) and incubated at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere (Suzhou Jiemei Electronics Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. CI-191C) for 3 min. Following incubation, 3 ml

high-glucose DMEM (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

G4524) was added and the cells were centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 3

min at 25°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was

resuspended in 3 ml DMEM. The cells were then seeded into 6-well

plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well and incubated

overnight. The following day, small interfering RNA (siRNA) and

overexpression vectors were mixed with Lipofectamine™ 3000

transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no.

L3000001) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The

transfection mixture was then added to the wells according to the

experimental requirements and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. siSBEM was

synthesized by GenScript Biotech Corporation, with a synthesis

amount of 2.5 nmol diluted to 100 µmol/l. The overexpression vector

backbone employed in this study was pcDNA3.1(+) (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. V79020). For cell transfection, 4 µg of

the pcDNA3.1(+) vector, at a concentration of 1 µg/µl, was

introduced into the cells. The siRNA interference and

overexpression primer sequences are shown in Tables SI and SII, respectively.

Construction of PTX-resistant SUM190PT

and SKBR3 cell lines

PTX-resistant breast cancer cells were developed

based on previously described methods (26). Details of the drug-induction

protocol are shown in Table SIII.

To confirm the stability of the resistance phenotype, the PTX

(MedChemExpress; cat. no. HY-B0015) concentration was gradually

increased until a final concentration of 500 nmol/l was reached.

The cells were then maintained at this concentration and

subcultured for at least 10 generations. IC50 values

were measured at the 5th, 10th and 20th generations post-withdrawal

of PTX. When the IC50 values showed minimal variation

and were significantly higher than those of the parental cell

lines, the resistance model was deemed successfully established.

The parental lines are denoted as SUM190PT and SKBR3, while their

drug resistant counterparts are referred to as SUM190PT/PTX and

SKBR3/PTX. Resistance success was confirmed by comparing cell

viability and resistance coefficients before and after PTX

exposure. Resistant cell lines were continuously cultured in 500

nmol/l PTX to maintain drug resistance.

Cell experimental grouping

To assess whether SBEM knockdown could reverse drug

resistance in SUM190PT/PTX cells, the following groups were

established: SUM190PT (control), SUM190PT + PTX, SUM190PT/PTX + PTX

+ si-negative control (NC) and SUM190PT/PTX + PTX + siSBEM. To

evaluate whether SBEM overexpression induces PTX resistance, SKBR3

cells, which have relatively low SBEM expression, were divided

into: SKBR3 (control), SKBR3/PTX + PTX, SKBR3 + PTX + Vector and

SKBR3 + PTX + oeSBEM. AMPK activator 13 (MedChemExpress; cat. no.

HY-155363), an AMPK signaling pathway activator (27), was used to investigate the role of

SBEM in regulating AMPK signaling. For this, SUM190PT/PTX cells

were divided into four groups: Control, AMPK activator 13, siSBEM

and AMPK activator 13 + siSBEM. Both SUM190PT and SKBR3 cells were

treated with PTX at a concentration of 500 nmol/l for 48 h.

Drug-resistant cell lines SUM190PT/PTX and SKBR3/PTX were

maintained in medium containing 500 nmol/l PTX. Cells transfected

with siRNA or overexpression plasmids were incubated at 37°C for 48

h. In all groups involving AMPK activator 13, the concentration was

set at 5 µmol/l with an incubation time at 37°C for 24 h (27).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Following transfection, breast cancer cells and

drug-resistant cell lines in the exponential growth phase were

harvested, digested and resuspended. Then, 3,000 cells per well

were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated overnight. PTX was

applied at varying concentrations (125, 250, 500, 1,000, 2,000,

4,000 and 8,000 nmol/l) and the cells were incubated for 48 h.

Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G4103) was added to each well and incubated for

an additional 3 h. Optical density at 450 nm was measured using a

microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no.

A51119500C). IC50 values and PTX resistance coefficients

were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 (Dotmatics).

Total RNA extraction

Cell suspensions were collected and centrifuged at

1,200 × g for 3 min at 25°C. The supernatant was discarded and 1 ml

RNA extraction reagent (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat.

no. G3013) was added, followed by a 5-min incubation at room

temperature. Next, 100 µl chloroform (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G3014) was added and the mixture was shaken

vigorously for 15 sec, then allowed to stand for 5 min at room

temperature. The sample was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at

4°C, and the aqueous phase was transferred to a new centrifuge

tube. Then, 500 µl isopropanol (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. 67-63-0) was added and incubated for 10 min at room

temperature. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C,

the supernatant was discarded. The RNA pellet was washed with 1 ml

75% ethanol (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

E809061), air-dried and resuspended in 50 µl sterile water (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G4700). The RNA

concentration was quantified for use in subsequent experiments.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was conducted according to the instructions

of the SweScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G3335). The PCR cycling program was as follows:

50°C for 30 min, 98°C for 2 min, followed by 39 cycles of 98°C for

15 sec, 55°C for 20 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. A final extension step

was carried out at 72°C for 5 min. The primer sequence (5′-3′)

information is as follows: SBEM forward, TCTGCCCAGAATCCGACAAC, and

reverse GGGCTTCATCATCAGCAGGA; GAPDH forward, CTGGGCTACACTGAGCACC,

and reverse AAGTGGTCGTTGAGGGCAATG. GAPDH was used as the internal

reference gene and the 2−∆∆Cq was used as the relative

expression level of the target gene mRNA (28).

Western blotting

Breast cancer cell suspensions were collected and

lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. G2002). Lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and

then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 25°C. The supernatant

was collected and proteins were denatured in a 95°C water bath for

15 min. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein

quantification kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

G2026). Cell lysis and protein-loading buffers (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0015) were added to normalize the

protein concentrations across samples. Then, 10 µl (30 µg) of each

protein solution was loaded into the wells of the gel (10%).

Electrophoresis was performed at 80 V for 30 min, followed by 120 V

for 60 min. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to

PVDF membranes at 260 mA for 2 h. PVDF membranes were blocked with

5% skim milk (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

GC310001) at room temperature for 2 h, then washed three times with

TBST (0.1% Tween 20) (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat.

no. G0004) for 5 min each. Primary antibody solutions were added

and incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubation, secondary

antibody solutions were applied and incubated at room temperature

for 1 h. Details of the antibodies, including manufacturer cat. no.

and dilution ratios, are provided in Table SIV. After washing with TBST,

chemiluminescent detection was performed using a luminescent

substrate (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G2161)

and images were captured using a gel imaging system (Mona

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. GD50202). Images were analyzed

with ImageJ 1.5.2a software (National Institutes of Health) for

subsequent statistical analyses.

Cell apoptosis

Exponentially growing breast cancer cells were

treated as aforementioned in the Cell experimental grouping

subsection, then centrifuged and resuspended as previously

described. According to the instructions of the flow cytometry

apoptosis detection kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. G1511), 5 µl FITC solution was added to each cell

suspension, followed by incubation in the dark at room temperature

for 30 min. Subsequently, PI solution was added and incubated in

the dark for an additional 5 min. Cells were analyzed using a

Attune™ NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat.

no. A24858) and Attune™ NxT software (version 6; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) within 2 h of staining.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Exponentially growing breast cancer cells were

treated as aforementioned in the Cell experimental grouping

subsection, then centrifuged and resuspended as previously

described. Cell lysis buffer was added according to the Co-IP kit

protocol (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P2179M) and

the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The

lysates were then centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 3 min at 25°C and

the supernatant was collected. Protein A/G magnetic beads

pre-conjugated with the primary antibody were added (20 µl of

magnetic bead suspension to every 500 µl of protein sample) and the

mixtures were incubated overnight at room temperature. After

incubation, the beads were washed with washing buffer and the

immunocomplexes bound to the beads were eluted using the elution

buffer. The eluted target proteins were analyzed via western

blotting. Antibody details are provided in Table SIV.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM

Corp.). All experiments were independently repeated at least three

times. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Comparisons between two groups were performed using unpaired

t-tests. Differences among multiple groups were assessed using

one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

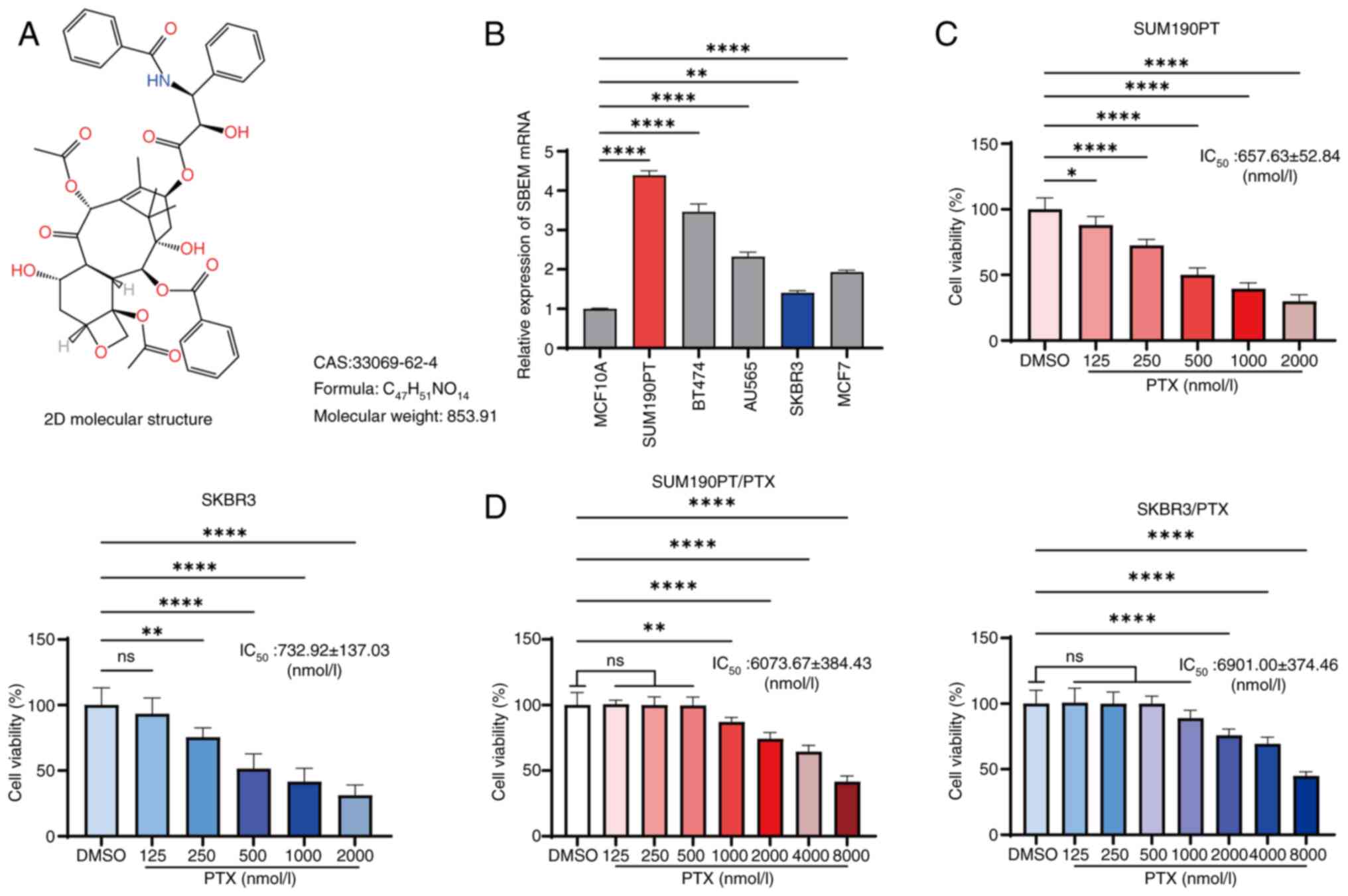

SBEM induces PTX drug resistance

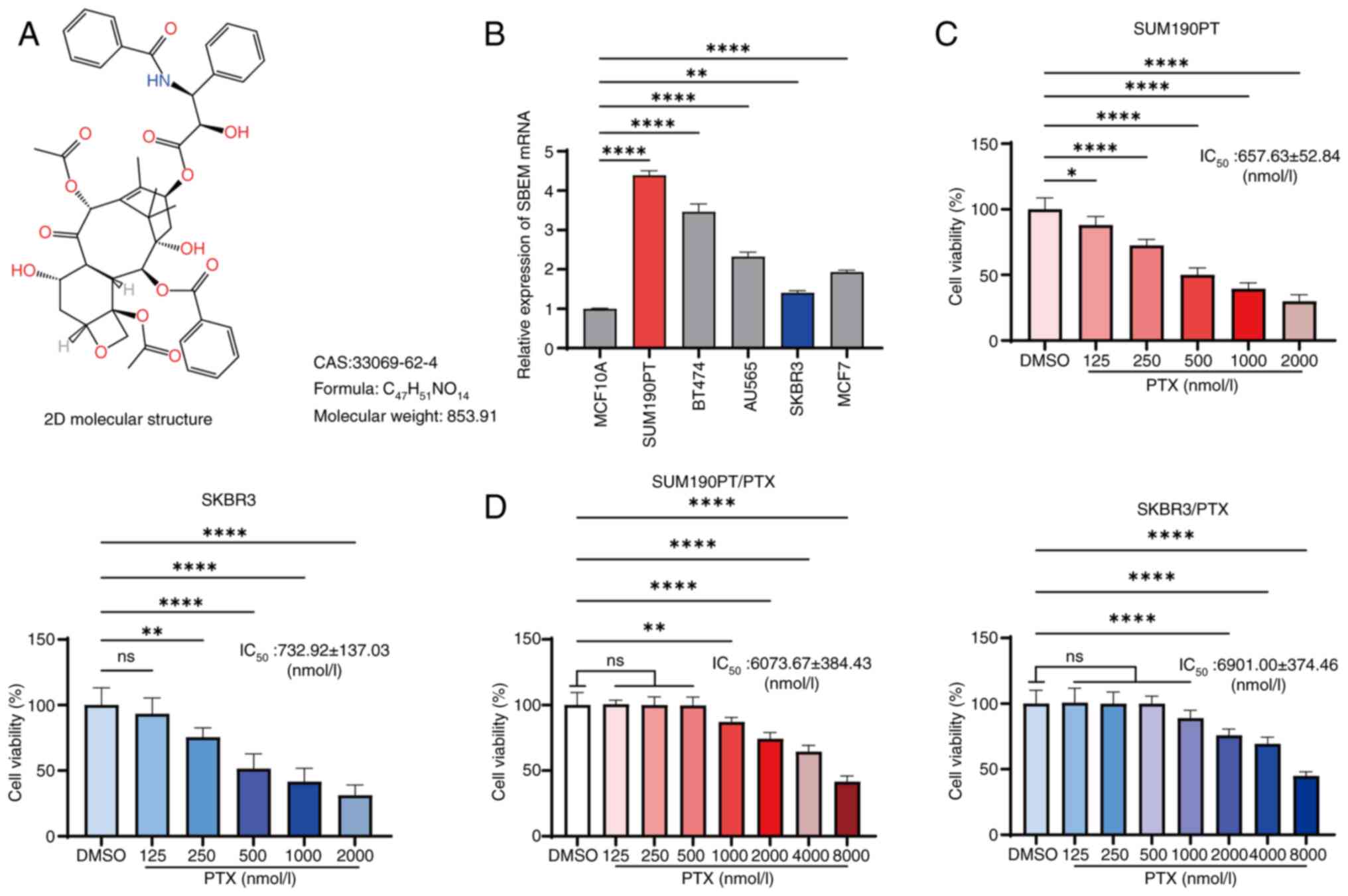

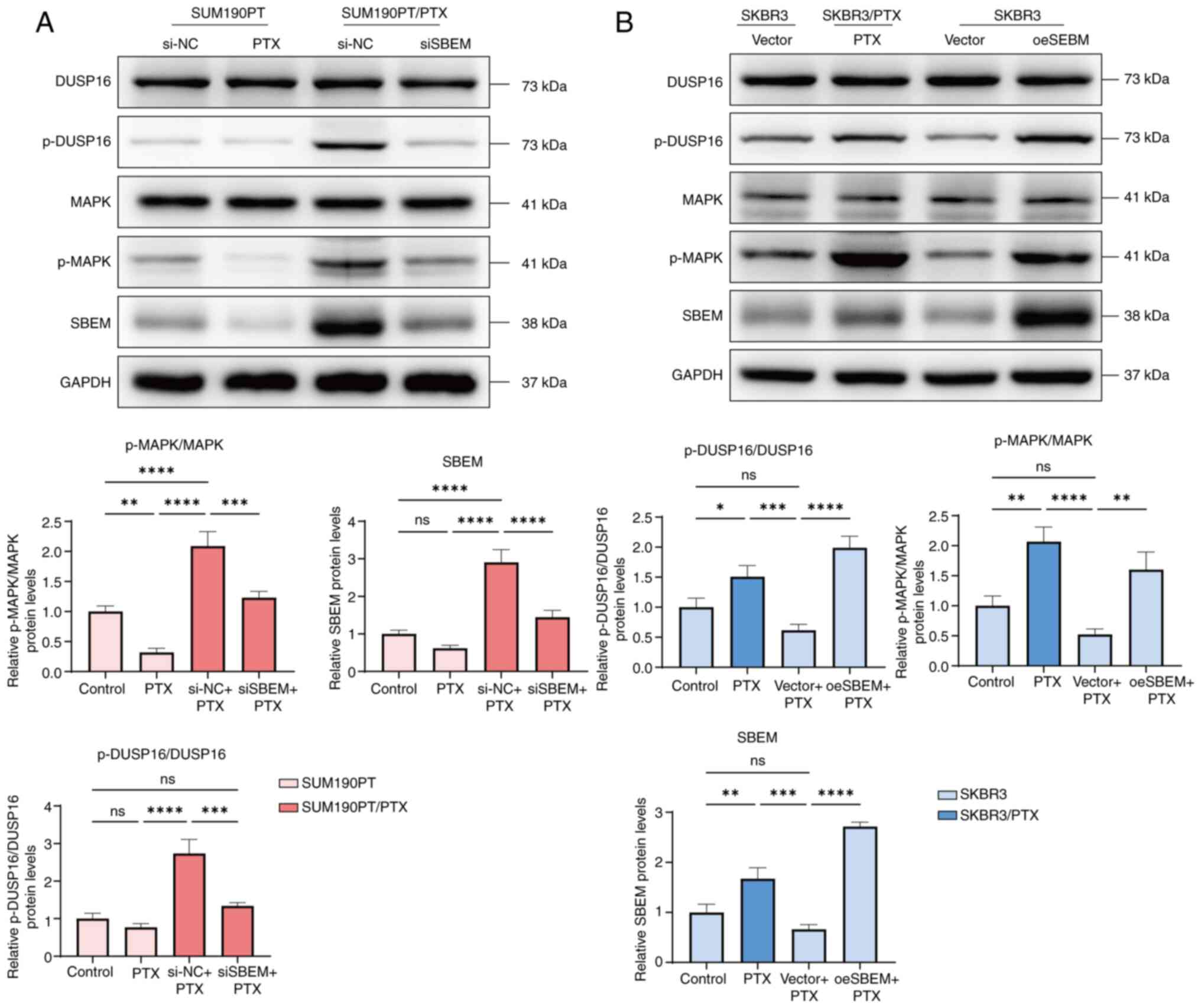

The 2D structural formula of PTX is shown in

Fig. 1A. The SBEM mRNA expression

levels in various breast cancer cell and normal breast epithelial

cell lines were assessed using RT-qPCR. Compared with MCF10A cells,

SBEM mRNA expression was highest in SUM190PT cells and lowest in

SKBR3 cells (Fig. 1B). Since SBEM

was highly expressed in the SUM190PT cell line, a knockdown cell

line using this cell line was initially planned. However, as the

present study focuses on drug-resistant strains, a SBEM-knockdown

cell line using the SUM190PT/PTX drug-resistant strain was

ultimately constructed. Additionally, SKBR3 cells, which have low

SBEM expression, were selected to create a SBEM-overexpressing cell

line. Knockdown and overexpression experiments in cell lines

representing the two extremes of SBEM expression were conducted to

more clearly observe the impact of SBEM modulation on cellular

behaviors, such as viability and PTX resistance. This maximized the

differences in experimental outcomes and enhanced the

persuasiveness of the findings.

| Figure 1.Inhibition of breast cancer cell

viability by PTX and the construction of PTX-resistant strains. (A)

2D molecular structure of PTX. (B) Relative expression levels of

SBEM mRNA in MCF10A, SUM190PT, BT474, AU565, SKBR3 and MCF7 cells

were measured using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction. (C) CCK-8 assay showing changes in the viability of

SUM190PT and SKBR3 cells treated with varying PTX concentrations.

(D) CCK-8 assay showing changes in the viability of SUM190PT/PTX

and SKBR3/PTX cells treated with varying PTX concentrations.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant; PTX,

paclitaxel; SBEM, small breast epithelial mucin; CCK-8, Cell

Counting Kit-8. |

The establishment of PTX-resistant cell lines was

validated using the CCK-8 assay. After 48 h of PTX treatment, the

SUM190PT and SKBR3 cell viabilities were significantly inhibited,

with IC50 values of 657.63±52.84 nmol/l and

732.92±137.03 nmol/l, respectively (Fig. 1C). By contrast, the PTX-resistant

SUM190PT/PTX and SKBR3/PTX cells exhibited respective

IC50 values of 6073.67±384.43 nmol/l and 6901.00±374.46

nmol/l, with corresponding resistance coefficients of 8.95±1.33 and

9.04±1.46 (Fig. 1D). These data

confirmed the successful generation of the PTX-resistant cell

lines.

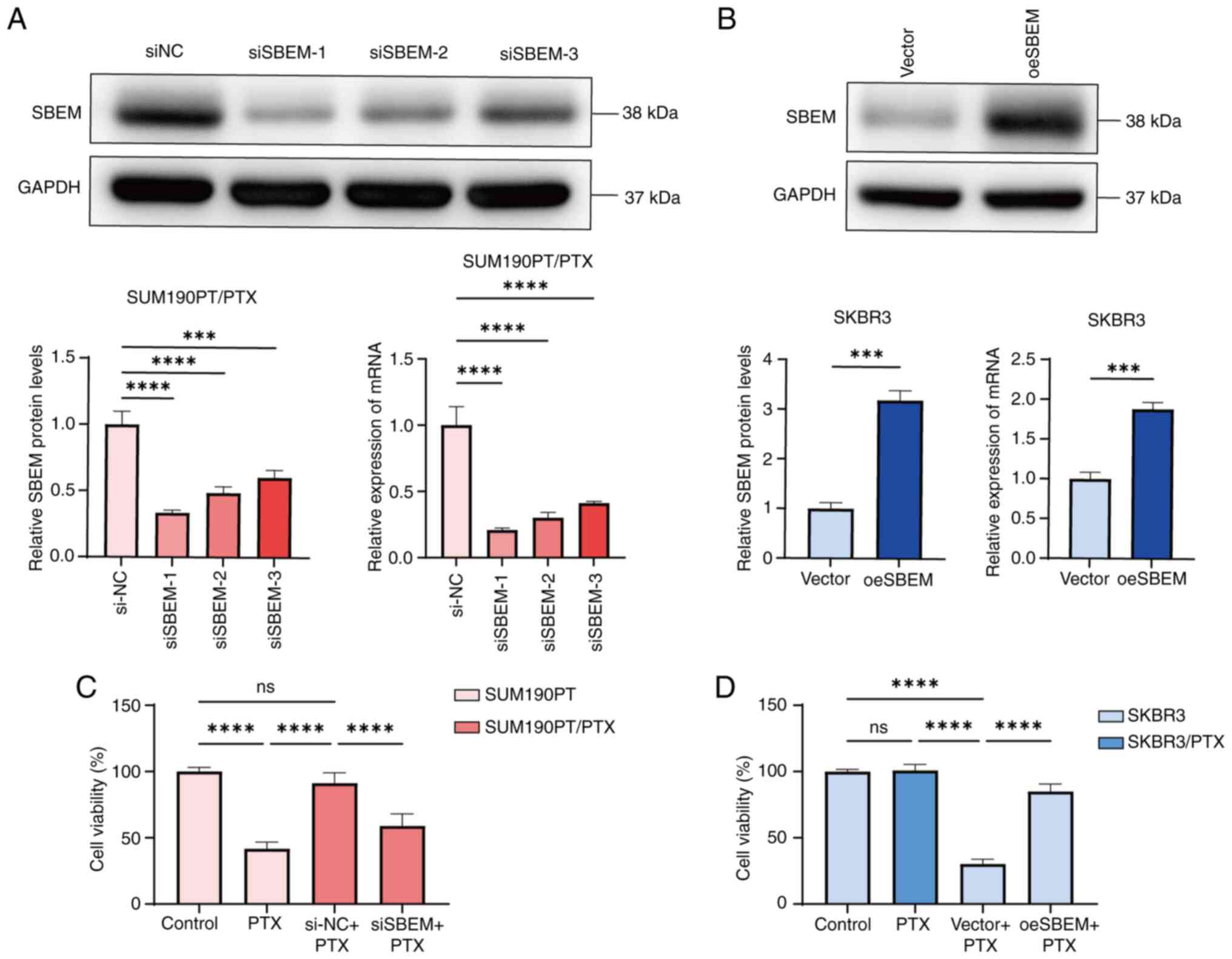

To further explore the association and potential

mechanism of SBEM in PTX resistance, cell lines with upregulated or

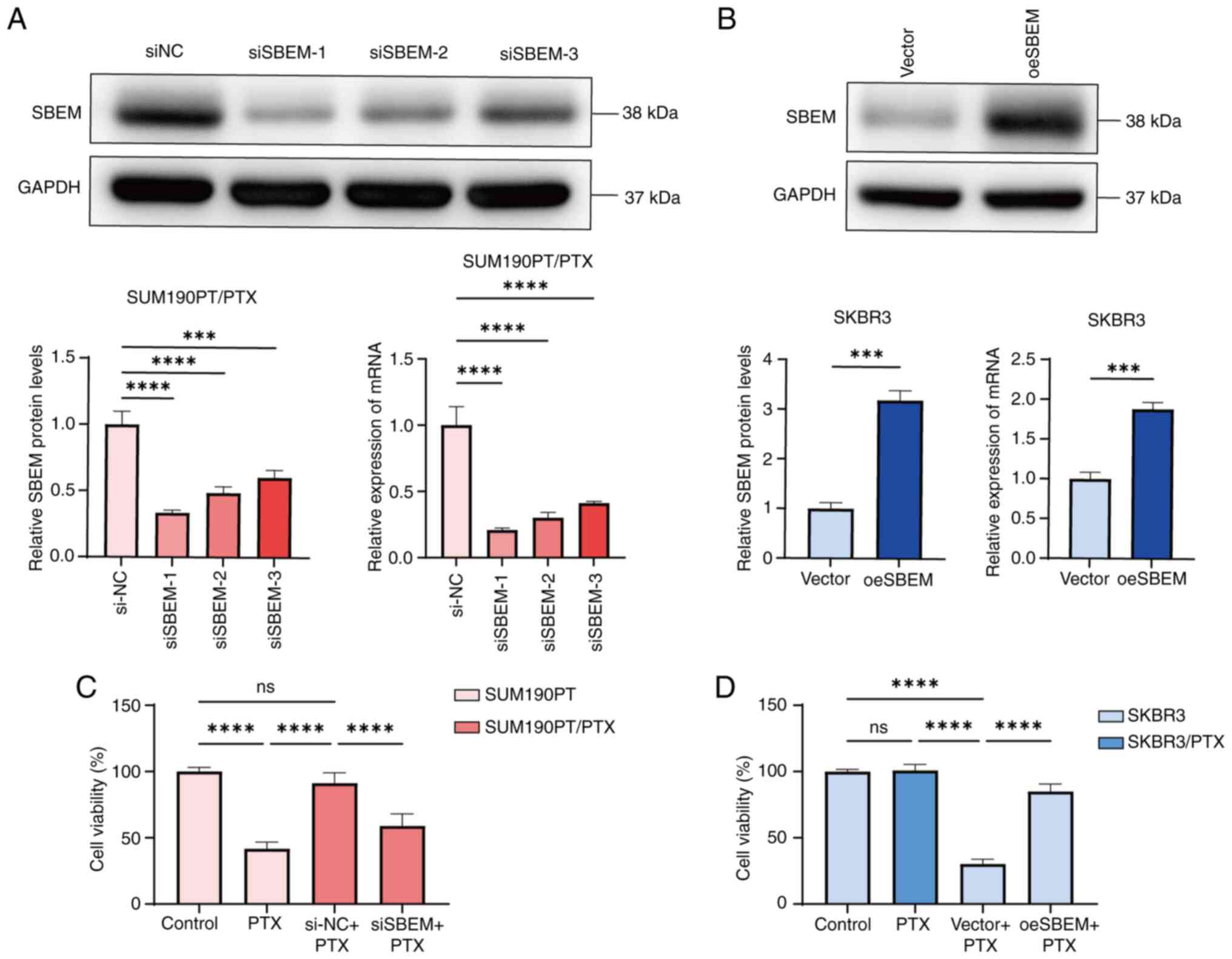

downregulated SBEM expression were established (Fig. 2A and B). Among the siRNAs tested,

siSBEM-1 most effectively inhibited both SBEM mRNA and protein

expression and was therefore selected for subsequent experiments.

The effects of SBEM knockdown and overexpression on the

proliferation of SUM190PT/PTX and SKBR3 cells were assessed using

the CCK-8 assay. The results demonstrated that SBEM knockdown

restored PTX sensitivity in SUM190PT/PTX cells, whereas SBEM

overexpression reduced PTX sensitivity (Fig. 2C and D). These findings suggest that

SBEM expression may be associated with PTX sensitivity in breast

cancer cells.

| Figure 2.Changes in SBEM expression and the

effect on PTX resistance. (A) Western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses

of SBEM protein and mRNA levels in SUM190PT/PTX cells 48 h

post-transfection with siSBEM. (B) Western blotting and RT-qPCR

analyses of SBEM protein and mRNA levels in SKBR3 cells 48 h

post-transfection with the SBEM overexpression plasmid. (C)

SUM190PT cells were treated with PTX (500 nmol/l) for 48 h. In the

case of SUM190PT/PTX cells, the PTX concentration in the

drug-resistant medium was maintained at 500 nmol/l. Subsequently,

siRNA (SBEM) was transfected for 48 h. The CCK-8 assay was used to

detect the changes in cell viability of SUM190PT and SUM190PT/PTX

cells after treatment. (D) SKBR3 cells were treated with PTX (500

nmol/l) for 48 h. Subsequently, the cells were transfected with the

SBEM-overexpressing plasmid and incubated for another 48 h. For

SKBR3/PTX cells, the PTX concentration in the drug-resistant medium

was maintained at 500 nmol/l. The CCK-8 assay was used to detect

the changes in cell viability of SKBR3 and SKBR3/PTX cells after

treatment. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant;

PTX, paclitaxel; SBEM, small breast epithelial mucin; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction;

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; si, small interfering (RNA); NC,

negative control; oe, overexpression. |

SBEM has binding sites for PTX and

interacts with DUSP16

While it was demonstrated that SBEM may be

associated with PTX sensitivity, its precise regulatory mechanism

remains unclear. The following analyses were conducted to screen

the rational domains of the SBEM protein. The prediction results

showed that the protein ipTM=-pTM=0.23, with a relatively low

overall confidence level (Fig.

S1A). In addition, amino acids 1–20 were predicted to form the

signal peptide region (Fig. S1B).

Next, PrankWeb was used, which is based on machine learning; it

learns the characteristics of a large number of known binding sites

through a Random Forest algorithm to predict the protein structure

(28). The results are shown in

Fig. S1C and the red area

represents the active site. The score of this active site (residue

site: 1) is >1 (score: 1.45) and the average AlphaFold score is

>70 (score: 83.21), both of which indicate a high level of

confidence in this site (27).

Additionally, it was noted that SBEM is also known as MUCL1. MUCL

has two subtypes: MUCL1 and MUCL3. To detect the conserved

sequences, a sequence alignment between MUCL1 (ID: Q96DR8) and

MUCL3 (ID: Q3MIW9) was performed (Fig.

S1D). The alignment results were consistent with the prediction

of the active site, both of which are located in the N-terminal

region. The molecular docking results showed that PTX can bind

tightly to SBEM (Fig. 3A). The

strongest calculated binding free energy was-6.4 kcal/mol. In

addition, each docking free energy was <-5.0 kcal/mol,

demonstrating a good binding between the two. PTX was predicted to

not only bind to the Pro84 amino acid of SBEM through a hydrogen

bond but also form hydrophobic interactions with Met1, Ala5, Val6

and Pro84. Most notably, the distance of each interaction was <4

Å, indicating a relatively strong bond energy (Table SV).

Additionally, to verify the interaction between SBEM

and DUSP16, a Co-IP assay was performed. DUSP16 was detected in the

SBEM IP, supporting a physical interaction between the two

proteins. Furthermore, SBEM knockdown led to a reduction in the

phosphorylated (p-)DUSP16 levels in the input group. However, no

significant change in total DUSP16 protein expression was observed

compared with the siNC group, suggesting that SBEM may regulate

DUSP16 phosphorylation rather than its expression (Fig. 3B).

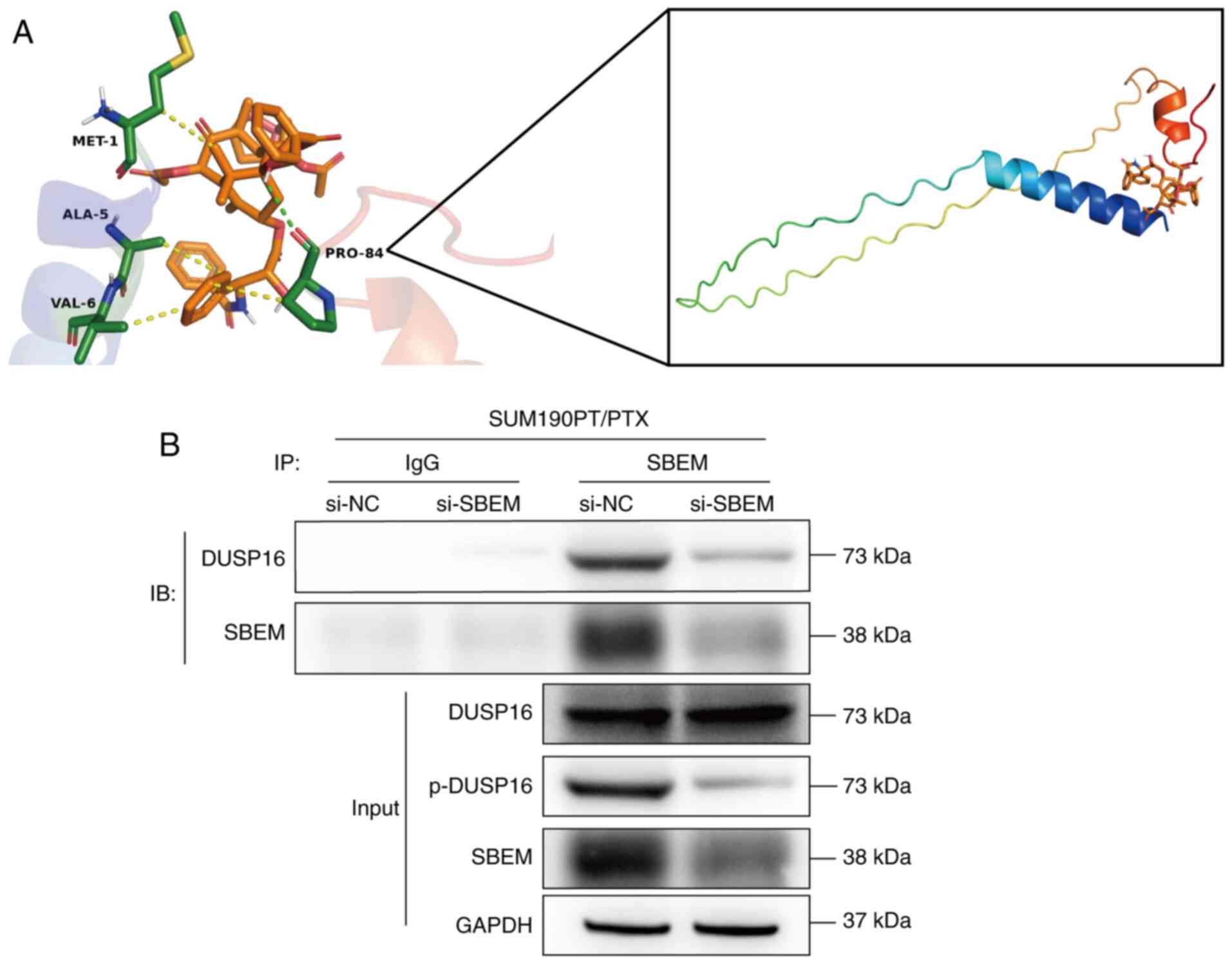

Downregulation of SBEM restores PTX

sensitivity in breast cancer cells

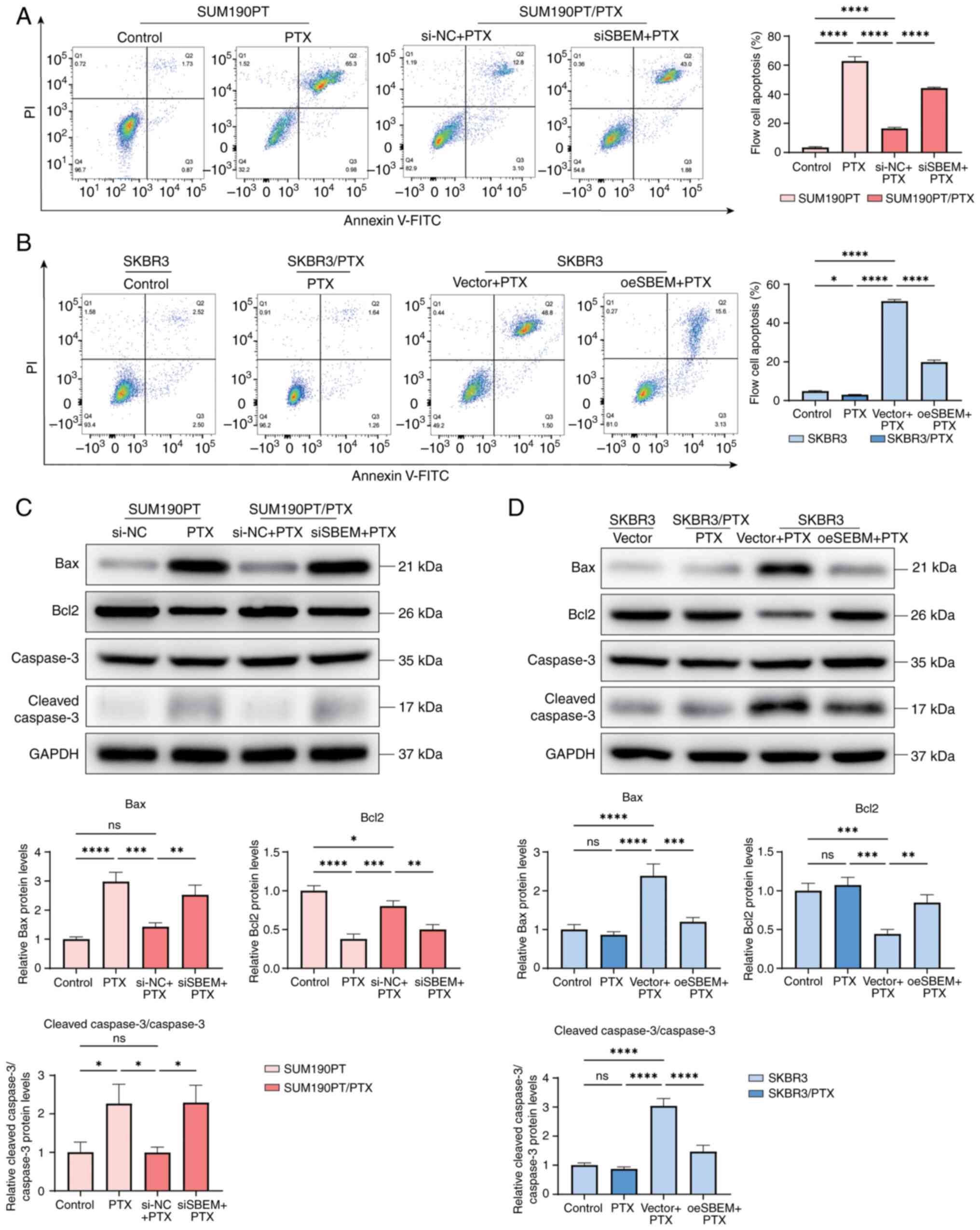

Following SBEM knockdown, the apoptosis rate of

SUM190PT/PTX cells (in culture medium containing 500 nmol/l PTX)

significantly increased. The apoptosis rate of the SBEM-knockdown

group increased approximately three-fold, rising from 16.53% in the

control group (siNC + PTX) to 44.25% in the knockdown group (siSBEM

+ PTX) (Fig. 4A). By contrast, SBEM

overexpression in SKBR3 cells (in culture medium containing 500

nmol/l PTX) significantly decreased apoptosis (Fig. 4B). To further investigate this

observation, the expression of apoptosis-related proteins was

analyzed.

| Figure 4.SBEM modulates PTX-induced apoptosis

in breast cancer cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in

SUM190PT/PTX and SUM190PT cells following various treatments. (B)

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in SKBR3/PTX and SKBR3 cells

following various treatments. (C) Western blot analysis of Bax,

Bcl2, Caspase-3 and cleaved-Caspase-3 in SUM190PT/PTX and SUM190PT

cells. (D) Western blot analysis of Bax, Bcl2, Caspase-3 and

cleaved-Caspase-3 in SKBR3/PTX and SKBR3 cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant;

PTX, paclitaxel; SBEM, small breast epithelial mucin; si, small

interfering (RNA); NC, negative control; oe, overexpression. |

In SUM190PT/PTX cells treated with PTX, compared

with the siNC + PTX group, the siSBEM + PTX group had increased

expression levels of Bax and cleaved-Caspase-3/Caspase-3, while the

Bcl2 expression was decreased (Fig.

4C). Conversely, in SKBR3 cells treated with PTX, compared with

the Vector + PTX group, overexpression of SBEM in the oeSBEM + PTX

group decreased the expression of Bax and

cleaved-Caspase-3/Caspase-3 and increased the expression of Bcl2

(Fig. 4D).

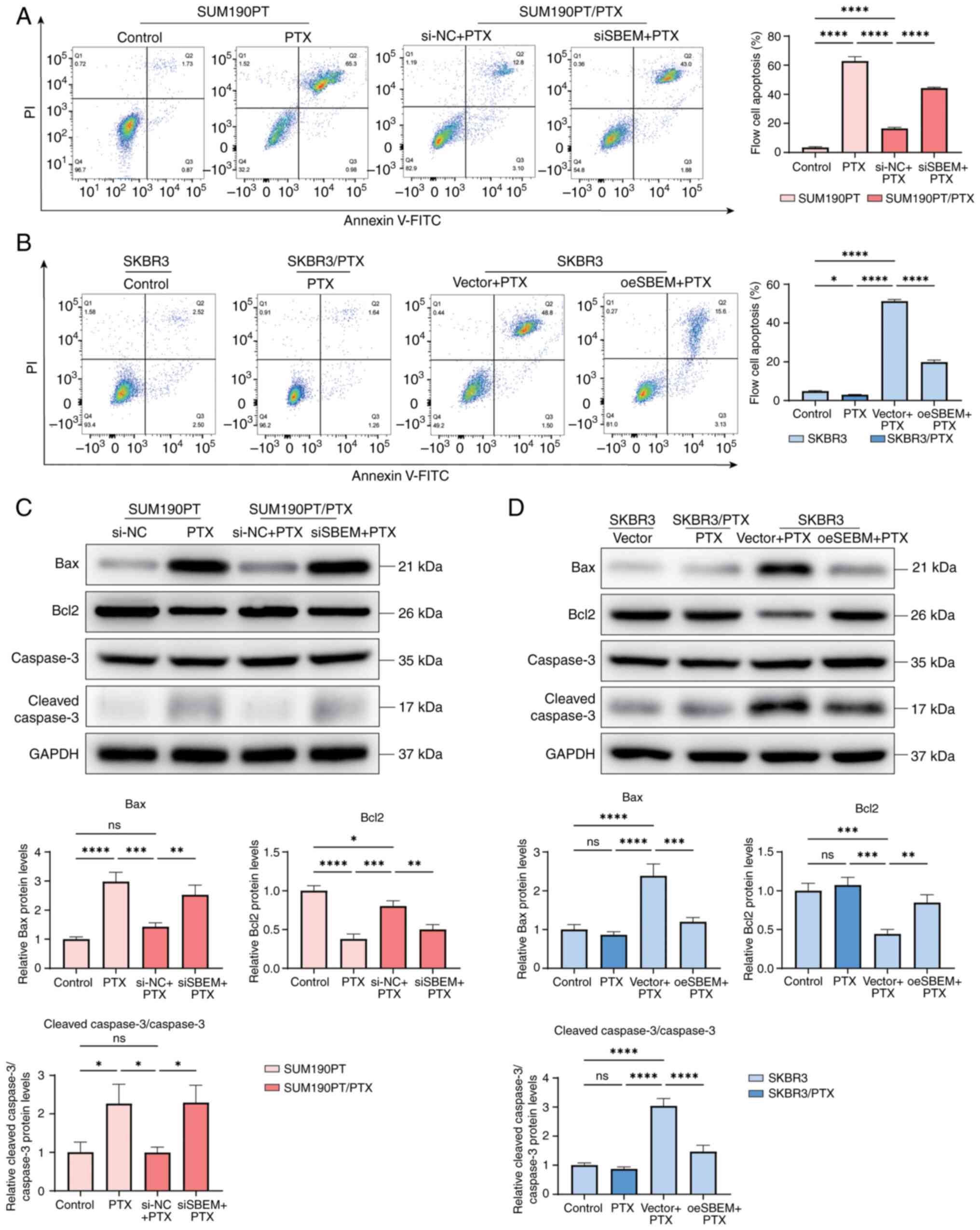

Downregulation of SBEM inhibits

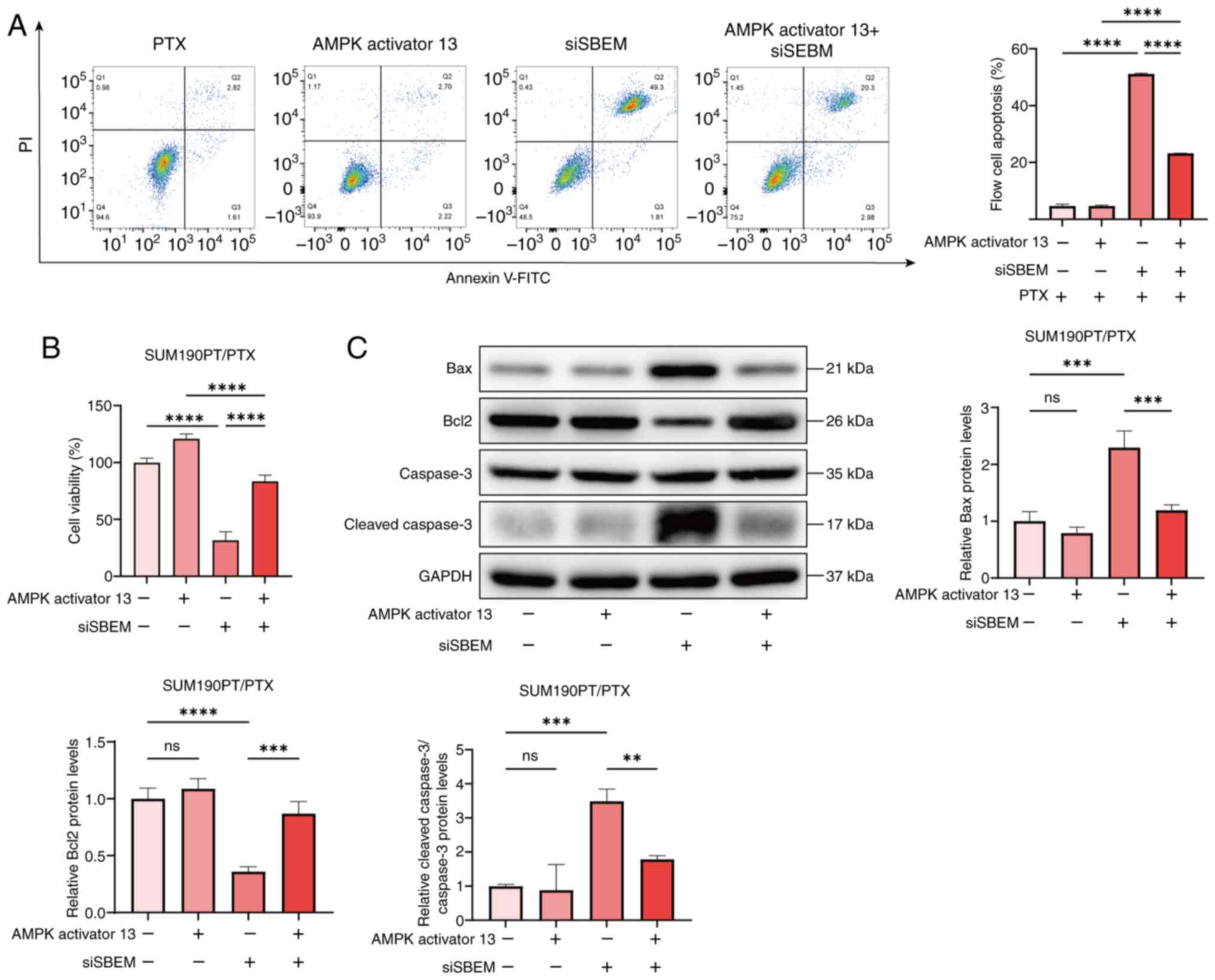

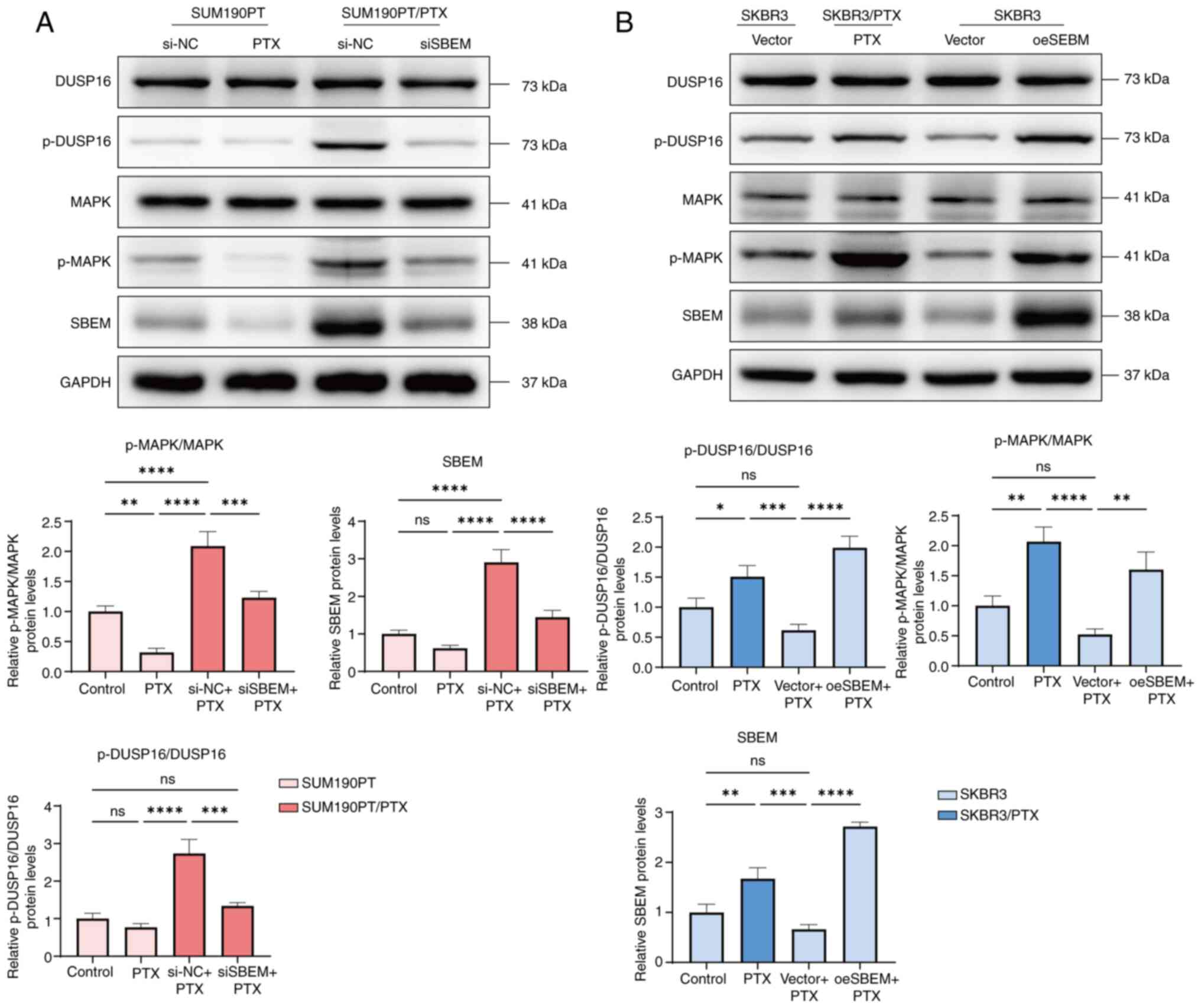

p-DUSP16 expression and the MAPK pathway

To elucidate the mechanism by which SBEM affects PTX

sensitivity, the expression levels of DUSP16 and MAPK-related

proteins were analyzed. In SUM190PT/PTX cells, compared with the

siNC + PTX group, knockdown of SBEM in the siSBEM + PTX group

decreased the ratios of p-DUSP16/DUSP16 and p-MAPK/MAPK (Fig. 5A). By contrast, in SKBR3 cells

treated with PTX, compared with the Vector + PTX group,

upregulation of SBEM in the oeSBEM + PTX group increased these

ratios (Fig. 5B). These findings

suggest that SBEM enhances DUSP16 phosphorylation and activates the

MAPK signaling pathway, thereby potentially contributing to PTX

resistance.

| Figure 5.SBEM regulates p-DUSP16 and the MAPK

signaling pathway. (A) Western blotting of DUSP16, p-DUSP16, MAPK,

p-MAPK and SBEM in SUM190PT and SUM190PT/PTX cells. (B) Western

blotting of DUSP16, p-DUSP16, MAPK, p-MAPK and SBEM in SKBR3 and

SKBR3/PTX cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. ns, not significant. PTX, paclitaxel; SBEM, small

breast epithelial mucin; DUSP16, dual specificity phosphatase 16;

p-, phosphorylated; si, small interfering (RNA); NC, negative

control; oe, overexpression, |

SBEM induces PTX resistance in breast

cancer cells by activating the MAPK pathway

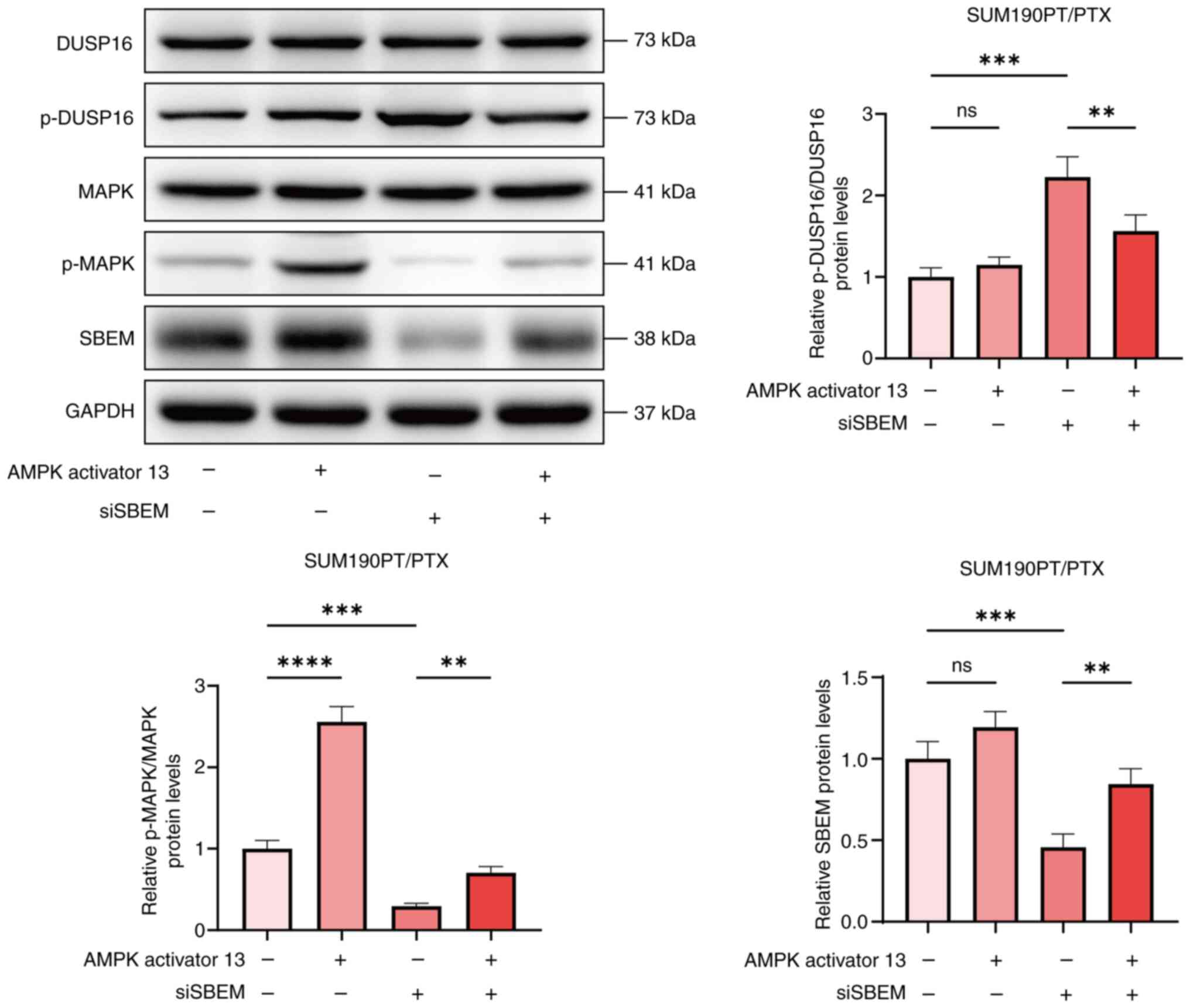

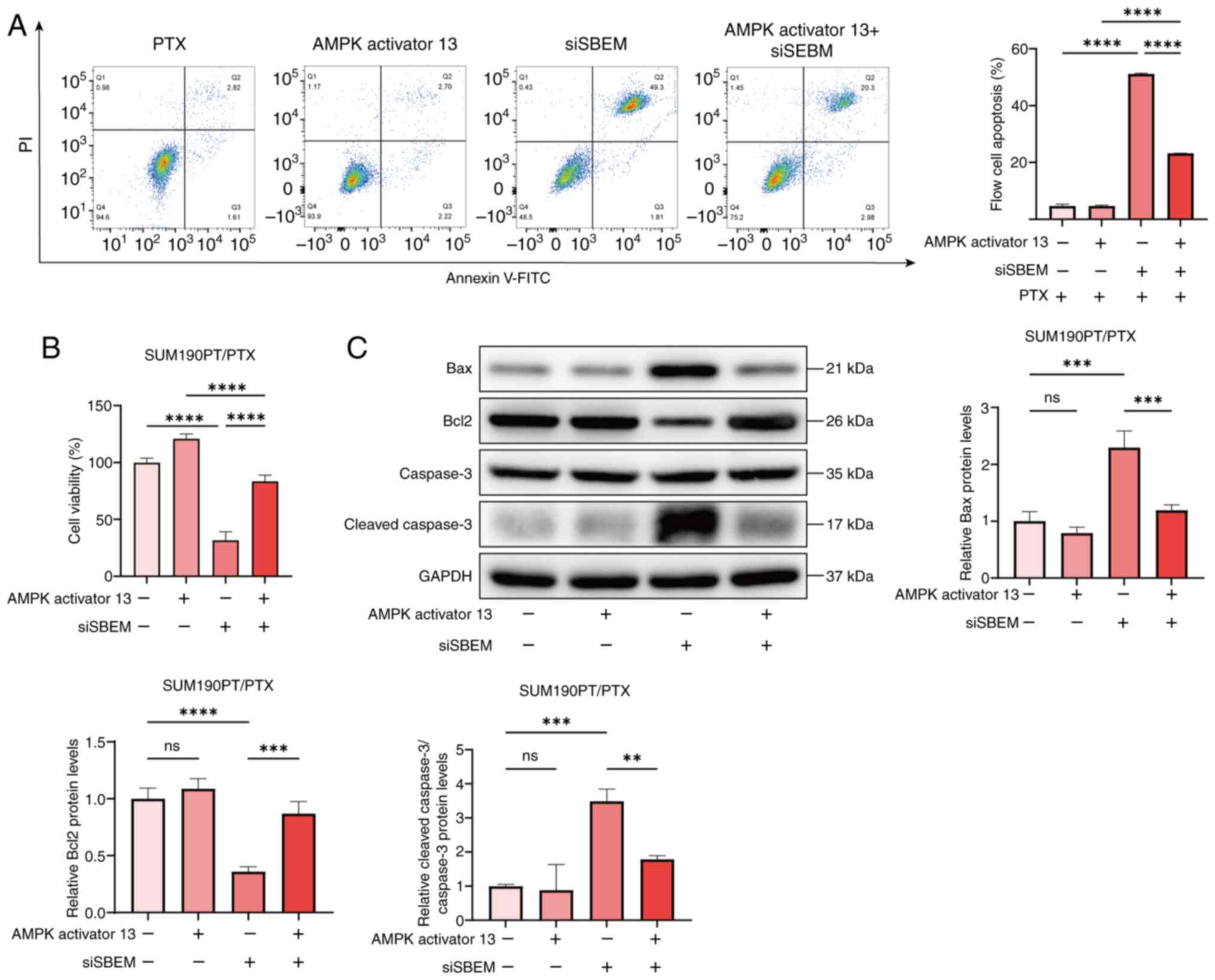

To further investigate the regulatory effect of SBEM

on the MAPK pathway, SUM190PT/PTX cells were treated with the MAPK

pathway activator, AMPK activator 13. The results showed that in

SUM190PT/PTX cells treated with PTX, compared with the siSBEM

group, the level of apoptosis in the siSBEM + AMPK activator 13

group decreased significantly while the cell viability increased

significantly. The results indicated that AMPK activator 13

counteracted the inhibitory effects of SBEM on the viability and

induction of apoptosis in SUM190PT/PTX cells (Fig. 6A and B). Furthermore, compared with

the siSBEM group, the addition of AMPK activator 13 (siSBEM + AMPK

activator 13 group) significantly reduced the levels of Bax and

cleaved-Caspase-3 and increased the expression of Bcl2 (Fig. 6C). The effect of AMPK activator 13

on apoptosis-related proteins reversed the impact of siSBEM.

| Figure 6.SBEM induces PTX resistance in breast

cancer cells by activating the AMPK pathway. (A) Flow cytometry

analysis of apoptosis in SUM190PT/PTX cells transfected with siRNA

for 48 h and treated with AMPK activator 13 (5 µmol/l) for 24 h.

(B) The treatment of SUM190PT/PTX cells was the same as

aforementioned. After the treatment, the change in cell viability

was determined by the CCK-8 assay. (C) The treatment of

SUM190PT/PTX cells was the same as aforementioned. After the

treatment, the relative expression levels of Bax, Bcl2, Caspase-3

and cleaved-Caspase-3 proteins were detected by western blotting.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant;

PTX, paclitaxel; SBEM, small breast epithelial mucin; CCK-8, Cell

Counting Kit-8; si, small interfering (RNA). |

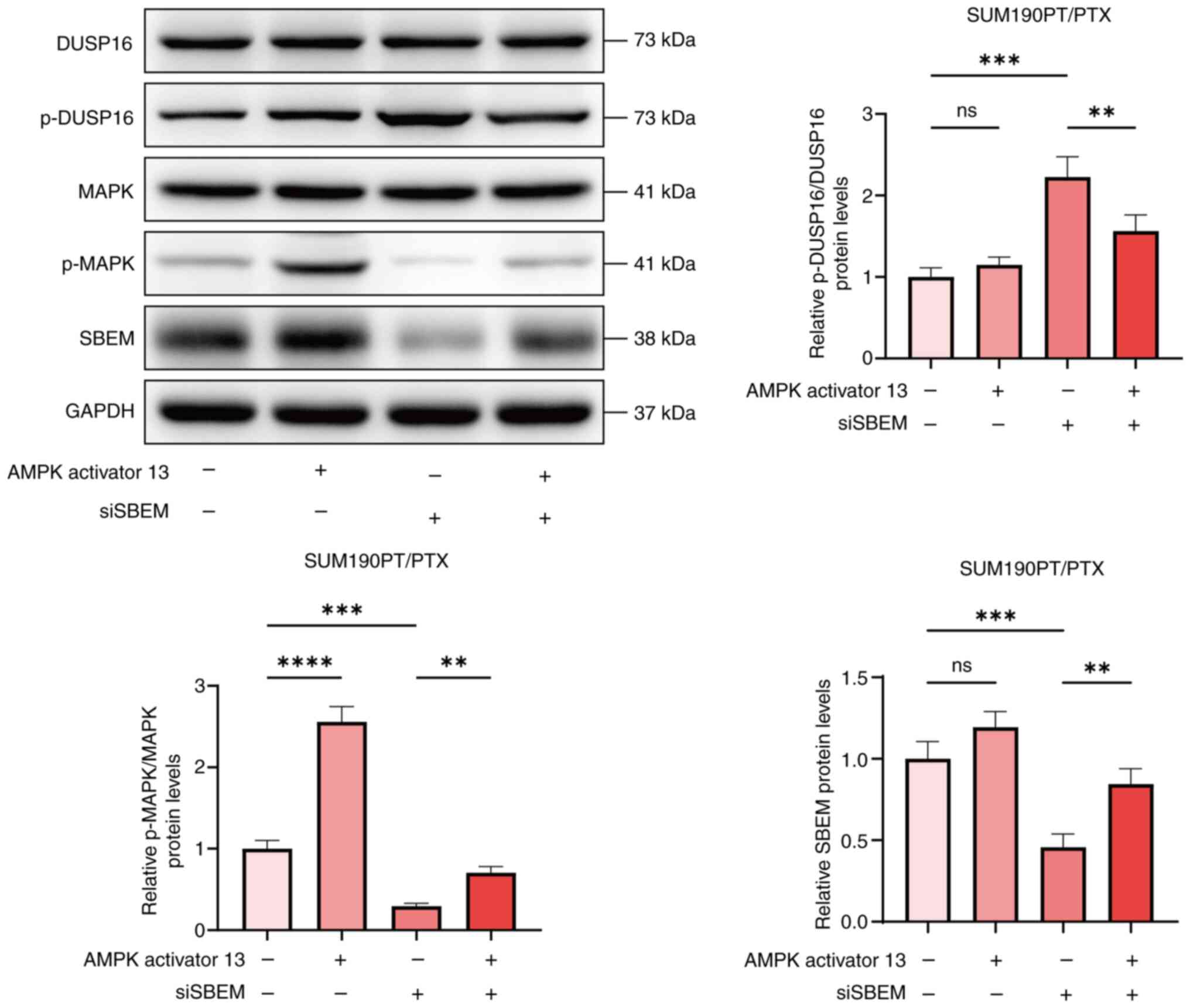

In addition, in SUM190PT/PTX cells treated with PTX,

compared with the siSBEM group, the p-DUSP16/DUSP16 level decreased

and the p-MAPK/MAPK level increased in the siSBEM + AMPK activator

13 group (Fig. 7). These findings

suggest that SBEM may contribute to drug resistance in breast

cancer cells by activating the MAPK pathway.

| Figure 7.AMPK activator 13 restores drug

sensitivity to PTX. Western blotting of DUSP16, p-DUSP16, MAPK,

p-MAPK and SBEM protein levels in SUM190PT/PTX cells transfected

with siRNA for 48 h and treated with AMPK activator 13 for 24 h.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant;

PTX, paclitaxel; SBEM, small breast epithelial mucin; DUSP16, dual

specificity phosphatase 16; p-, phosphorylated; si, small

interfering (RNA). |

Discussion

PTX, a key chemotherapeutic agent for breast cancer,

is frequently associated with the development of drug resistance,

making it crucial to investigate the underlying mechanisms of this

resistance (29). In the present

study, a predicted binding interaction between SBEM and PTX was

identified and it was demonstrated that downregulation of SBEM can

restore PTX sensitivity. However, the specific binding sites

(single or multiple) between PTX and SBEM remain unclear. In

future, we plan to utilize protein structure-based approaches such

as site-directed mutagenesis and crystallographic analysis to

systematically elucidate the interaction between PTX and SBEM. This

will further validate and refine the findings of the present study.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death (30), is one of the primary mechanisms by

which PTX exerts its anticancer effects. However, tumor cells often

develop resistance to PTX, diminishing its therapeutic efficacy

(31,32). The present study demonstrated that

overexpression of SBEM in SKBR3 cells conferred resistance to PTX

and reduced its cytotoxic effect. Conversely, SBEM knockdown in

SUM190PT/PTX cells restored apoptosis upon PTX treatment,

indicating that SBEM inhibits PTX-induced apoptosis. Bax, a member

of the Bcl2 protein family, plays a crucial role in PTX-induced

apoptosis by promoting mitochondrial membrane permeabilization

(33). During apoptosis, Bax

translocates from the cytoplasm to the mitochondrial membrane and

forms homodimers, increasing mitochondrial outer membrane

permeability and leading to the release of cytochrome c and other

pro-apoptotic factors, which activate the Caspase cascade and

ultimately induce apoptosis (34,35).

In line with this mechanism, the findings of the present study

revealed that SBEM downregulation significantly increased the

expression of Bax and cleaved-Caspase-3 proteins while reducing

Bcl2 expression, thereby promoting apoptosis in SUM190PT/PTX

cells.

PTX has been shown to activate the AMPK signaling

pathway, which plays an important role in its anticancer effects

(36,37). To further investigate the mechanism

of SBEM-induced PTX resistance, the present study focused on the

involvement of DUSP16 and the AMPK signaling pathways. AMPK, a

cellular energy sensor, is activated under conditions of energy

deficiency; it promotes catabolic pathways and inhibits anabolic

processes. The MAPK family, which includes ERK, JNK and p38,

responds to growth factors, stress and inflammatory signals to

regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation

(38). DUSP16 is mainly located

downstream of the MAPK signaling pathway, and its function is to

inhibit the activities of p38 and JNK MAPKs (19,20).

The results of the present study revealed an association between

SBEM and DUSP16 expression. Overexpression of SBEM significantly

increased the levels of p-DUSP16 and p-AMPK. Moreover, treatment

with an AMPK activator reversed the effects of siSBEM on breast

cancer apoptosis and associated protein expression. Therefore, we

hypothesize that SBEM may regulate PTX resistance by activating the

AMPK signaling pathway and inducing DUSP16 phosphorylation. The

results of the Co-IP experiment further confirmed that SBEM and

DUSP16 may interact with each other. However, based on the current

results, it cannot be determined whether SBEM and DUSP16 affect

protein expression through direct binding or indirect binding.

Therefore, further experimental verification is needed.

The major contribution of the present study is the

identification of SBEM as a regulator of DUSP16 phosphorylation and

the MAPK signaling pathway, ultimately promoting PTX resistance in

breast cancer cells. However, several limitations should be

acknowledged. In vivo validation using xenograft tumor mouse

models is necessary. Furthermore, SBEM expression should be

compared with established drug resistance markers, such as

P-glycoprotein and βIII-tubulin (39,40).

Although a positive association was observed between SBEM and

phosphorylated DUSP16 and MAPK proteins, the direct binding

relationship between SBEM and phosphorylated DUSP16 remains to be

elucidated and will be a key focus of future research.

Additionally, PTX resistance involves complex signaling networks,

necessitating further extensive investigation. At present, to the

best of our knowledge, the relationship between SBEM expression and

PTX resistance has not been examined in clinical breast cancer

samples. Future work will focus on clinical collaboration to

collect and analyze samples from patients with PTX-resistant breast

cancer, to further validate the clinical relevance and therapeutic

potential of targeting SBEM.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrated that downregulation of SBEM enhanced the sensitivity

of breast cancer cells to PTX by targeting DUSP16 and inhibiting

the MAPK signaling pathway. These findings suggest that SBEM could

serve as a therapeutic target to overcome PTX resistance. Thus, the

present study provides a theoretical basis for the use of SBEM

inhibitors in combination with PTX to improve treatment efficacy in

breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Wu Jieping Medical Foundation for

Special Fund of Clinical Scientific Research (grant no. 320.6750)

and Beijing Health League Foundation for Clinical and Medical

Research of Medical Research and Development Foundation

Project.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LL conceived, designed and supervised the study. NL

and XL performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. QY,

SL and JW collected the data. HS and YD were responsible for

conceptualization and data curation. XL revised the manuscript. NL

and XL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All the

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wilkinson L and Gathani T: Understanding

breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol.

95:202110332022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA,

Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A and Siegel RL: Breast cancer

statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 69:438–451. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A,

Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Gralow JR, Cardoso F, Siesling S

and Soerjomataram I: Current and future burden of breast cancer:

Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 66:15–23. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Thürlimann B,

Weber WP, Poortmans P, Regan MM, Senn HJ, Winer EP and Gnant M;

Panelists of the St Gallen Consensus Conference, : Customizing

local and systemic therapies for women with early breast cancer:

The St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for treatment of

early breast cancer 2021. Ann Oncol. 32:1216–1235. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Abu Samaan TM, Samec M, Liskova A, Kubatka

P and Büsselberg D: Paclitaxel's mechanistic and clinical effects

on breast cancer. Biomolecules. 9:7892019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dan VM, Raveendran RS and Baby S:

Resistance to intervention: Paclitaxel in breast cancer. Mini Rev

Med Chem. 21:1237–1268. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang Y, Lun X and Guo W: Expression of

TRPC1 and SBEM protein in breast cancer tissue and its relationship

with clinicopathological features and prognosis of patients. Oncol

Lett. 20:3922020.

|

|

8

|

Hao H, Yang L, Wang B, Sang Y and Liu X:

Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for

breast cancer patients. Open Life Sci. 18:202207842023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hao H, Wang B, Yang L, Sang Y, Xu W, Liu

W, Zhang L and Jiang D: miRNA-186-5p inhibits migration, invasion

and proliferation of breast cancer cells by targeting SBEM. Aging

(Albany NY). 15:6993–7007. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li QH, Liu ZZ, Ge Y, Liu X, Xie XD, Zheng

ZD, Ma YH and Liu B: Small breast epithelial mucin promotes the

invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells via promoting

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Rep. 44:509–518. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu ZZ, Xie XD, Qu SX, Zheng ZD and Wang

YK: Small breast epithelial mucin (SBEM) has the potential to be a

marker for predicting hematogenous micrometastasis and response to

neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis.

27:251–259. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wen S, Hou Y, Fu L, Xi L, Yang D, Zhao M,

Qin Y, Sun K, Teng Y and Liu M: Cancer-associated fibroblast

(CAF)-derived IL32 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and

metastasis via integrin β3-p38 MAPK signalling. Cancer Lett.

442:320–332. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Butti R, Das S, Gunasekaran VP, Yadav AS,

Kumar D and Kundu GC: Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in breast

cancer: Signaling, therapeutic implications and challenges. Mol

Cancer. 17:342018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ren C, Han X, Lu C, Yang T, Qiao P, Sun Y

and Yu Z: Ubiquitination of NF-κB p65 by FBXW2 suppresses breast

cancer stemness, tumorigenesis, and paclitaxel resistance. Cell

Death Differ. 29:381–392. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhou Y, Pang J, Liu H, Cui W, Cao J and

Shi G: Fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 promotes

autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells, contributing to nab-paclitaxel chemoresistance.

Med Oncol. 40:532022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhao PW, Cui JX and Wang XM: Upregulation

of p300 in paclitaxel-resistant TNBC: Implications for cell

proliferation via the PCK1/AMPK axis. Pharmacogenomics J. 24:52024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Abedini MR, Muller EJ, Bergeron R, Gray DA

and Tsang BK: Akt promotes chemoresistance in human ovarian cancer

cells by modulating cisplatin-induced, p53-dependent ubiquitination

of FLICE-like inhibitory protein. Oncogene. 29:11–25. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Caunt CJ and Keyse SM: Dual-specificity

MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs): Shaping the outcome of MAP kinase

signalling. FEBS J. 280:489–504. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cargnello M and Roux PP: Activation and

function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated

protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 75:50–83. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Roux PP and Blenis J: ERK and p38

MAPK-activated protein kinases: A family of protein kinases with

diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 68:320–344.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hoornaert I, Marynen P, Goris J, Sciot R

and Baens M: MAPK phosphatase DUSP16/MKP-7, a candidate tumor

suppressor for chromosome region 12p12-13, reduces BCR-ABL-induced

transformation. Oncogene. 22:7728–7736. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Low HB and Zhang Y: Regulatory roles of

MAPK phosphatases in cancer. Immune Netw. 16:85–98. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lu H, Tran L, Park Y, Chen I, Lan J, Xie Y

and Semenza GL: Reciprocal regulation of DUSP9 and DUSP16

expression by HIF1 controls ERK and p38 MAP kinase activity and

mediates chemotherapy-induced breast cancer stem cell enrichment.

Cancer Res. 78:4191–4202. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Keyse SM: Dual-specificity MAP kinase

phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27:253–261.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Polák L, Škoda P, Riedlová K, Krivák R,

Novotný M and Hoksza D: PrankWeb 4: A modular web server for

Protein-ligand binding site prediction and downstream analysis.

Nucleic Acids Res. 53:W466–W471. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Shi Y, Wang J, Tao S, Zhang S, Mao L, Shi

X, Wang W, Cheng C, Shi Y and Yang Q: miR-142-3p improves

paclitaxel sensitivity in resistant breast cancer by inhibiting

autophagy through the GNB2-AKT-mTOR pathway. Cell Signal.

103:1105662023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mishra T, Gupta S, Rai P, Khandelwal N,

Chourasiya M, Kushwaha V, Singh A, Varshney S, Gaikwad AN and

Narender T: Anti-adipogenic action of a novel oxazole derivative

through activation of AMPK pathway. Eur J Med Chem. 262:1158952023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhu Y, Wang A, Zhang S, Kim J, Xia J,

Zhang F, Wang D, Wang Q and Wang J: Paclitaxel-loaded ginsenoside

Rg3 liposomes for drug-resistant cancer therapy by dual targeting

of the tumor microenvironment and cancer cells. J Adv Res.

49:159–173. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fleisher TA: Apoptosis. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol. 78:245–950. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wu M, Xue L, Chen Y, Tang W, Guo Y, Xiong

J, Chen D, Zhu Q, Fu F and Wang S: Inhibition of checkpoint kinase

prevents human oocyte apoptosis induced by chemotherapy and allows

enhanced tumour chemotherapeutic efficacy. Hum Reprod.

38:1769–1783. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang BR, Han JB, Jiang Y, Xu S, Yang R,

Kong YG, Tao ZZ, Hua QQ, Zou Y and Chen SM: CENPN suppresses

autophagy and increases paclitaxel resistance in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells by inhibiting the CREB-VAMP8 signaling axis.

Autophagy. 20:329–348. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Habib TN, Altonsy MO, Ghanem SA, Salama MS

and Hosny MA: Optimizing combination therapy in prostate cancer:

Mechanistic insights into the synergistic effects of Paclitaxel and

Sulforaphane-induced apoptosis. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 25:52024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lin YW, Lin TT, Chen CH, Wang RH, Lin YH,

Tseng TY, Zhuang YJ, Tang SY, Lin YC, Pang JY, et al: Enhancing

efficacy of Albumin-bound paclitaxel for human lung and colorectal

cancers through autophagy receptor sequestosome 1

(SQSTM1)/p62-mediated nanodrug delivery and cancer therapy. ACS

Nano. 17:19033–19051. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Albuquerque T, Neves AR, Paul M, Biswas S,

Vuelta E, García-Tuñón I, Sánchez-Martin M, Quintela T and Costa D:

A Potential effect of circadian rhythm in the Delivery/therapeutic

performance of Paclitaxel-dendrimer nanosystems. J Funct Biomater.

14:3622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim JH, Lee JO, Kim N, Lee HJ, Lee YW, Kim

HI, Kim SJ, Park SH and Kim HS: Paclitaxel suppresses the viability

of breast tumor MCF7 cells through the regulation of EF1α and

FOXO3a by AMPK signaling. Int J Oncol. 47:1874–1880. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Tang Z, Zhang Y, Yu Z and Luo Z: Metformin

suppresses stemness of Non-small-cell lung cancer induced by

paclitaxel through FOXO3a. Int J Mol Sci. 24:166112023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yuan J, Dong X, Yap J and Hu J: The MAPK

and AMPK signalings: Interplay and implication in targeted cancer

therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1132020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chu J, Panfen E, Wang L, Marino A, Chen

XQ, Fancher RM, Landage R, Patil O, Desai SD, Shah D, et al:

Evaluation of encequidar as an intestinal P-gp and BCRP specific

inhibitor to assess the role of intestinal P-gp and BCRP in

Drug-drug interactions. Pharm Res. 40:2567–2584. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rieske P, Krynska B and Azizi SA: Human

Fibroblast-derived cell lines have characteristics of embryonic

stem cells and cells of Neuro-ectodermal origin. Differentiation.

73:474–483. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|