Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are tumors with

neuroendocrine differentiation and expression of neuroendocrine

markers, which can occur in various organs; however, they most

commonly in the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for 55–70% of

all NEN cases (1). Esophageal

neuroendocrine carcinoma (ENEC) is a rare subtype within digestive

tract NENs, comprising only 0.4–1% of gastroenteropancreatic NENs.

ENEC is highly aggressive, prone to widespread metastasis and has a

markedly worse prognosis compared with other common types of

esophageal cancer, such as squamous cell carcinoma and

adenocarcinoma (2).

Epidemiological studies have indicated that ENEC is

more common in middle-aged and elderly men, and that it shows

geographical clustering with higher incidence rates in certain

regions, such as East Asia (including in China and Japan) (2,3). The

risk factors for ENEC partially overlap with those of esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), such as smoking, alcohol

consumption, and a diet characterized by the frequent consumption

of foods and beverages at very high temperatures (>65°C has been

classified as probably carcinogenic to humans by the International

Agency for Research on Cancer) (4),

which may induce DNA damage and epigenetic changes in the

esophageal mucosa (5,6). Certain patients with ENEC also present

with Barrett's esophagus, which suggests that chronic inflammation

might drive neuroendocrine differentiation through abnormal

proliferative signaling pathways (7).

ENEC exhibits high biological heterogeneity. Early

studies have suggested that it originates from amine precursor

uptake and decarboxylation cells in the esophageal mucosa, derived

from the neuroectoderm (8,9). However, more recent research has

proposed that it likely originates from pluripotent basal

epithelial stem cells in the esophagus, which can differentiate

into squamous or glandular epithelium under normal conditions but

may aberrantly differentiate into NEC under epigenetic or

microenvironmental pressure, forming mixed tumors (10).

The present review particularly focuses on ENEC due

to its distinct clinicopathological features and highly aggressive

biological behavior. This focused approach is predicated on the

distinct clinicopathological and molecular features of ENEC, which

are justified by the fundamental differences between ENEC and other

gastrointestinal NECs, particularly gastric NEC (GNEC). First, ENEC

and GNEC possess unique molecular profiles; ENECs are characterized

by a high frequency of co-mutations in tumor protein 53 and

retinoblastoma gene 1, resembling small cell lung cancer, whereas

GNECs exhibit considerable heterogeneity with alterations in genes

such as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1B and

dysregulation of pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin (11). Second, they arise from different

epidemiological origins; ENEC shares strong associations with risk

factors for ESCC (for example, smoking and alcohol) (12), whereas GNEC is often associated with

chronic atrophic gastritis analogous to gastric adenocarcinoma

(13). Notably, ENEC is associated

with a markedly worse prognosis compared with GNEC, as confirmed by

large-scale database analyses (3).

Current evidence for the management of ENEC is often extrapolated

from small cell lung cancer or aggregated with other NECs,

underscoring the need for this particular synthesis of

ENEC-specific data to provide clinicians with a nuanced overview of

contemporary management and potential future directions.

While the seminal review by Ma et al

(1) provided a key foundation to

understand ENEC, the subsequent 8 years (2017–2025) have witnessed

a paradigm shift in its management, which forms the core

contribution of current research. The present review synthesizes

these recent advances, which include the successful application of

immune checkpoint inhibitors (for example, nivolumab and

camrelizumab) (14–16), the emergence of combination

immunotherapy strategies targeting cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell

death protein-1 (PD-1) (17,18),

and novel regimens combining anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs) with immunotherapy (for example, anlotinib plus

camrelizumab) (19–21). The present review also provides a

key evaluation of refined chemotherapeutic approaches, such as the

validation of folinic acid + fluorouracil + irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in

second-line settings (22,23) and the exploration of modified

folinic acid + fluorouracil + irinotecan + oxaliplatin

(mFOLFIRINOX, which typically involves dose adjustments of the

constituent drugs to improve tolerability) (22), moving beyond the traditional

platinum-etoposide (EP) backbone. Furthermore, to translate

evidence into practice, the present review offers structured

guidance for clinicians, incorporating insights from recent trials

(24–26) and summaries of ongoing clinical

studies (for example, NCT04325425 and NCT04169672) (21,26).

This comprehensive and up-to-date review aimed to equip clinicians

with the knowledge to navigate the rapidly evolving therapeutic

landscape of this aggressive malignancy in the future.

Pathological features and diagnosis

Pathological classification

According to the 2019 World Health Organization

classification of digestive system NENs (27), NENs are classified into

well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), poorly

differentiated NECs and mixed neuroendocrine-non-NENs (MiNENs).

NETs are graded G1 to G3 based on mitotic count and Ki-67 index

(27). NECs are divided into small

cell NEC (SCNEC) and large cell NEC (LCNEC), with SCNEC accounting

for ~90% of all ENEC cases. Grossly, NECs often present as invasive

submucosal masses or ulcerative lesions with esophageal lumen

narrowing (28). Histologically,

SCNEC exhibits oat cell-like nests with necrosis, whereas LCNEC

features vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and rosette

structures. MiNENs contain ≥30% neuroendocrine components and may

also exhibit adenocarcinoma or squamous differentiation (29). In China, MiNENs are usually

squamous-dominant, whereas in Western countries, they often coexist

with adenocarcinoma (30) (Table I).

| Table I.Classification of NENs. |

Table I.

Classification of NENs.

| Type of NEN | Morphological and

molecular features |

|---|

| NET |

|

| G1 | Mitotic count,

<2/2 mm2 (or <2/10 HPF); Ki-67 index, ≤3% |

| G2 | Mitotic count,

2–10/2 mm2 (or 2–20/10 HPF); Ki-67, 3–20% |

| G3 | Mitotic count,

>10/2 mm2 (or >20/10 HPF); Ki-67, >20% |

| NEC |

|

| Small

cell NEC (accounts for | High mitotic count,

>10/2 mm2 (or >20/10 HPF); Ki-67, >20% (often

>55%) |

| ~90% of

esophageal NEC cases) |

|

| Large

cell NEC | High mitotic count,

>10/2 mm2; Ki-67, >20% (often >55%) |

| MiNEN | Biphasic tumor with

≥30% each of neuroendocrine (NET/NEC) and non-neuroendocrine

components |

Diagnosis

Pathological confirmation of NENs necessitates a

multimodal diagnostic approach. Immunohistochemically,

synaptophysin (Syn) exhibits high sensitivity (>95%) and is

expressed in virtually all NENs. Chromogranin A (CgA) is more

specific but less expressed in poorly differentiated NECs,

requiring additional markers such as CD56 and neuron-specific

enolase (31).

Insulinoma-associated protein 1, a sensitive and specific nuclear

marker for neuroendocrine differentiation, is increasingly used in

diagnostic panels, particularly when conventional markers are

equivocal (31–33). However, the interpretation of

immunohistochemical markers in NECs poses notable challenges. Key

interpretative pitfalls include: i) Heterogeneous or weak

expression levels of Syn and CgA in poorly differentiated tumors,

which may lead to false-negative diagnoses; ii) non-specific

staining of CD56 observed in a range of non-neuroendocrine

malignancies, such as small cell lung carcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma

and certain types of sarcoma; and iii) highly variable expression

patterns in MiNENs, underscoring the necessity of extensive tumor

sampling and the application of a comprehensive antibody panel to

prevent misclassification (32).

Imaging features of ENEC markedly overlap with ESCC

and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), making radiological

distinction challenging. Specifically, ENEC typically presents on

X-ray barium swallow as irregular mucosal destruction, strictures

or filling defects, similar to the appearances seen in ESCC and

EAC. On CT and enhanced CT, ENEC commonly manifests as focal or

circumferential wall thickening with heterogeneous enhancement,

patterns that are also frequently observed in advanced ESCC and

EAC. For ENEC, enhanced CT is crucial for assessing primary tumor

location, local invasion and distant metastasis (particularly to

the liver), with reported sensitivity for detecting liver

metastases reaching up to 79% (34,35).

Furthermore, endoscopic ultrasound accurately assesses tumor

origin, size and invasion depth, although it cannot reliably

differentiate ENEC from ESCC or EAC based solely on imaging

characteristics (34). PET-CT is

used for staging and recurrence detection (36). Somatostatin receptor (SSTR)

scintigraphy, using 111In-labeled octreotide, is more sensitive for

the detection of well-differentiated NETs and their metastases

(particularly in the liver and lungs). The sensitivity of SSTR

scintigraphy for poorly differentiated NECs is generally lower due

to reduced or absent SSTR expression (37).

The assessment of SSTR expression via functional

imaging also has potential therapeutic implications. Peptide

receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), such as

177Lu-oxodotreotide, is a well-established treatment

option for well-differentiated, SSTR+ NETs (38). However, to the best of our

knowledge, its role in poorly differentiated NECs, including ENEC,

remains limited and non-standard; this is primarily due to the

frequent absence or low density of SSTR expression in poorly

differentiated NECs, which precludes the use of SSTR-targeted

therapies (36). Therefore, patient

selection for PRRT in high-grade disease hinges on demonstrating

adequate SSTR expression on functional imaging, a finding that is

uncommon in NEC. Although anecdotal case reports exist (38,39),

robust clinical trial data supporting the efficacy of PRRT in ENEC

are currently lacking.

Treatment strategies

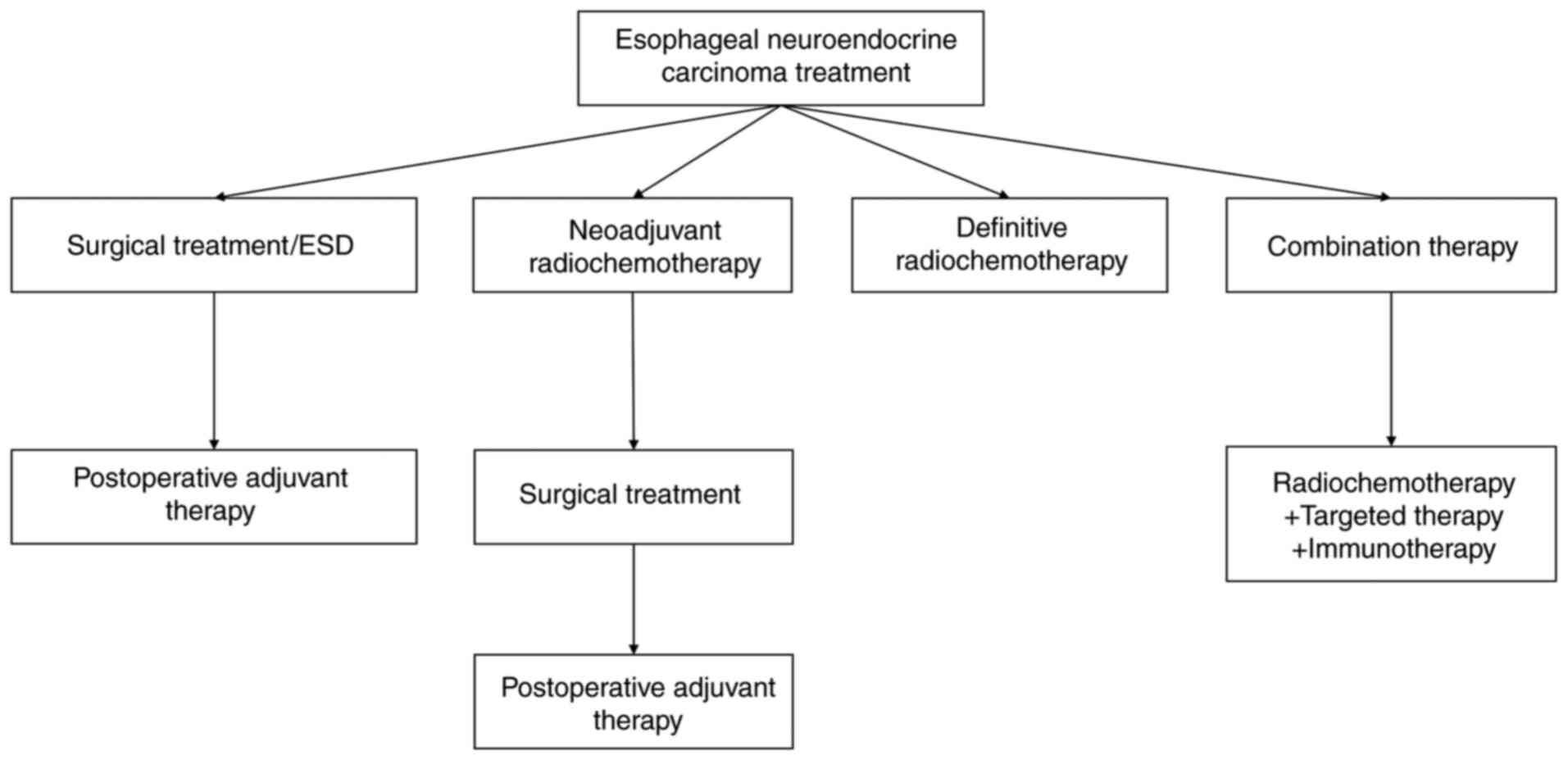

The management of ENEC involves a multimodal

approach, including surgery, platinum-based chemotherapy,

radiotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (Fig. 1).

Endoscopic treatment

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) can be

considered for highly selected cases of early ENEC confined to the

mucosa (Tis or T1a according to the American Joint Committee on

Cancer TNM staging system, 8th edition) (40) with a diameter of <1 cm (41). Although rare, such early cases have

been successfully treated with ESD. Case reports have described

patients achieving long-term disease-free survival following ESD

without adjuvant therapy (42,43).

For example, Fukui et al (42) documented a patient with pT1a ENEC

(muscularis mucosae invasion) who declined adjuvant therapy

post-ESD and remained recurrence-free during the 15-month

follow-up. Similarly, Cheng et al (43) reported a 3-year disease-free

survival in a case of NEC arising at the esophagogastric junction

without lymphovascular invasion, treated solely by ESD.

Neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant combined

surgery

Multimodal therapy combining neoadjuvant and/or

adjuvant therapy with surgery is standard for locally advanced

ENEC. Patients with resectable tumors and no lymph node metastasis

may undergo surgery first, followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy

if necessary (13). For initially

unresectable cases, neoadjuvant therapy may enable surgery

(1). Previous studies have

suggested that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery

markedly improves median overall survival (mOS) compared with

surgery or chemoradiotherapy alone (44–46).

In patients with initially unresectable locally

advanced ENEC, neoadjuvant therapy may facilitate surgical

conversion, followed by personalized adjuvant regimens (47). A multicenter trial by Shapiro et

al (48) demonstrated that

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy combined with surgery markedly

improved mOS in locally advanced ESCC (81.6 vs. 21.1 months) and

adenocarcinoma (43.2 vs. 27.1 months), establishing this approach

as the standard of care. Although ENEC was not included in this

previous study, extrapolation of these principles supports

guideline recommendations. The Clinical Practice Guidelines for

Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors conditionally

endorse neoadjuvant chemotherapy for borderline resectable ENEC

(49).

A previous systematic review revealed notably

increased survival outcomes with perioperative chemotherapy

(neoadjuvant, 31 months; adjuvant, 25 months) versus surgery alone

(9 months) in stage I–III ENEC, although no notable difference

existed between the adjuvant and neoadjuvant groups (50). Notably, adding radiotherapy to

neoadjuvant chemotherapy enhances surgical resectability and

pathological complete response rates but does not improve survival

(13). Awada et al (51) documented a case of poorly

differentiated ENEC treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and

surgery, achieving >5 years of survival.

Radiation therapy

For patients with locally advanced, inoperable ENEC

tumors, definitive chemoradiotherapy is recommended (52). Treatment plans should be based on

the extent of invasion and lymph node involvement. Combined

chemoradiotherapy yields a 3-year survival rate of ~31.6% (53). A Japanese retrospective study

further supported chemoradiotherapy as a viable option for locally

advanced ENEC (45). However,

unlike in limited-stage small cell lung cancer where it is a

standard of care, prophylactic brain irradiation is not routinely

recommended due to the low incidence of brain metastases in ENEC

(3).

Chemotherapy

First-line treatment

For advanced ENEC, systemic chemotherapy remains

essential (46). First-line

regimens are platinum-based doublets, either etoposide + platinum

(EP) or irinotecan + platinum (IP). Capecitabine with temozolomide

(CAPTEM), folinic acid + fluorouracil + oxaliplatin (FOLFOX),

FOLFIRI and FOLFIRINOX have also demonstrated activity (Table II) (54). Previous studies have reported

variable response rates [objective response rate (ORR), 14–75%] and

a median progression-free survival (PFS) time of 1.8–8.9 months

(25,54–56).

| Table II.Comparison between first-line

chemotherapy regimens. |

Table II.

Comparison between first-line

chemotherapy regimens.

| Regimen | Key data | Toxicity

profile | Evidence level |

|---|

| EP/EC | mOS, 12.5 months

(25); ORR, 14–75% (56,57);

mPFS, 5.36 months (25) | Neutropenia (90%),

anemia and thrombocytopenia |

Guideline-recommended (69) |

| IP | mOS, 10.9 months;

no notable difference vs. EP (25) | Diarrhea (50%),

neutropenia (60%) | Phase III

trial |

| CAPTEM | mOS, 12.6 months;

mPFS, 2.43 months (markedly lower compared with EP) (24) | Grade 3/4 adverse

events, 29% (markedly lower compared with EP) | Phase II trial |

| FOLFOX | DCR, 91.3%

(first-line); mPFS, 10 months (66) | Mild toxicity

(neurotoxicity and diarrhea) | Retrospective

study |

| FOLFIRI | DCR, 91%

(metastatic GI NEC) (67) | Neutropenia and

diarrhea | Small-sample

study |

| FOLFIRINOX | ORR, 46%; mOS, 17.8

months (n=8) (62) | High toxicity

(hematological and gastrointestinal) | Early

exploratory |

| mFOLFIRINOX | ORR, 77%; mOS, 20.6

months (n=35) (22) | Markedly higher

severe toxicity risk in women | Modified regimen

study |

The EP or etoposide and carboplatin (EC) regimen is

widely used in NEC, while IP demonstrates comparable efficacy but

distinct toxicity profiles. Retrospective studies have indicated

variable response rates (ORR, 14–75%) and a median PFS time of

1.8–8.9 months (57). The phase III

JCOG1213 TOPIC-NEC trial identified no notable difference in mOS

between EP and IP regimens (EP group, 12.5 months vs. IP group,

10.9 months). The ENEC subgroup (15.5% in EP vs. 9.3% in IP)

demonstrated no clear advantage in overall survival compared with

the IP regimen. Toxicity profiles differed; for example,

neutropenia occurred in 90% of patients treated with EP, whereas

diarrhea affected ~50% of patients treated with IP, necessitating

regimen selection based on individual tolerance (25). For patients who are

cisplatin-intolerant, the EC regimen serves as an alternative,

indicating efficacy comparable to EP (58). Notably, patients with Ki-67 >55%

exhibit lower ORR to platinum-based chemotherapy but improved

survival, a paradoxical phenomenon requiring further mechanistic

study and context-specific clinical strategies (59).

Despite high response rates, the short PFS of

first-line platinum-based regimens has prompted exploration of

alternative therapies. It is important to distinguish high-grade

NENs here; while the CAPTEM regimen is an option for advanced

well-differentiated G3 NET (neoplasia), it is not a standard

first-line therapy for poorly differentiated NEC. The role of

CAPTEM has primarily been explored in later-line settings (24,60).

Trials such as NCT04325425 are ongoing to compare mFOLFIRINOX and

EP regimens (61). FOLFOX and

FOLFIRI are being evaluated as alternatives or second-line

regimens, with varying degrees of disease control (62–64).

These exhibit antitumor activity in NEC; however, to the best of

our knowledge, randomized prospective phase II studies remain

limited and no international consensus exists. In a previous study

by Merola et al (65)

involving 72 patients with advanced cases (44.5% NET; 55.5% NEC),

FOLFOX achieved a disease control rate (DCR) of 75% and mPFS of 8

months, with first-line DCR reaching 91.3% (mPFS, 10 months) and

manageable toxicity. Extended treatment cycles were recommended for

well-tolerated patients. Du et al (66) reported a DCR of 91% for FOLFIRI in

11 metastatic gastrointestinal NEC cases. An early small-sample

study (n=8) of FOLFIRINOX demonstrated an ORR of 46% and mOS of

17.8 months in first-line treatment (61). A mFOLFIRINOX regimen (n=35) achieved

an ORR of 77% (mOS, 20.6 months), although severe toxicity in

female patients warrants caution (22). Most of these aforementioned studies

were retrospective with small sample sizes (n, 8–72), which

warrants the validation of FOLFOX efficacy. The ongoing randomized

phase II trial NCT04325425 comparing mFOLFIRINOX and EP regimens

may provide higher-level evidence for first-line NEC treatment

(26).

Second and multiple lines of

treatment

Second-line treatments have demonstrated limited

effectiveness (ORR, ~18%) (56).

Platinum rechallenge is considered for patients with progression

>6 months after first-line therapy (67). Irinotecan-based (FOLFIRI) and

oxaliplatin-based (FOLFOX) regimens are used in platinum-resistant

cases (62,64). Temozolomide-based regimens have

exhibited modest activity, particularly in O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT)-deficient tumors. Randomized trials are

ongoing to refine second-line therapy strategies. Table III compares the main second-line

chemotherapy regimens.

| Table III.Second-line chemotherapy regimens

comparison. |

Table III.

Second-line chemotherapy regimens

comparison.

| Regimen | mOS, months | mPFS, months | ORR, % | DCR, % | Evidence level |

|---|

| Platinum

rechallenge | 11.7 (71) | 3.2 (71) | 17/31 (56,70) | 62 (71) | Retrospective

study |

| FOLFIRI | 5.9–18 (63,64,72) | 4.4–5.8 (63,64,72) | - | 44-80 (63,64,72) | Heterogeneous

evidence |

| FOLFOX | - | - | - | 64 (65) | Retrospective

study |

| CAPTEM | 12.1–22 (74,76) | 5.86 (76) | 26 (61) | - | Evidence from

studies with conflicting results |

| Topoisomerase I

inhibitors | 4.3 (78) | 1.8 (78) | - | 15 (78) | TLC388 trial |

Platinum rechallenge

Current consensus, as reflected in international

guidelines such as those from the National Comprehensive Cancer

Network (NCCN) and expert group recommendations, recommends regimen

selection based on the duration of response to first-line

chemotherapy (67,68). Patients with a time to progression

of >6 months may consider EP rechallenge, whereas those with a

time to progression of ≤6 months may benefit from regimens such as

FOLFIRI or CAPTEM (67).

Platinum-based rechallenge strategies have achieved ORRs of 17 and

31% in extrapulmonary NEC (55,69).

In a nationwide multicenter study by Hadoux et al (70), platinum rechallenge chemotherapy

demonstrated a DCR of 62% (mPFS, 3.2 months; mOS, 11.7 months).

Patients with relapse-free intervals ≥3 months after first-line EP

chemotherapy who received rechallenge therapy had markedly longer

mOS (12 vs. 5.9 months). However, ENEC-specific subgroup analyses

were lacking.

FOLFIRI program

Irinotecan-based regimens have been demonstrated to

have heterogeneous efficacy. Previous studies have reported DCRs of

62–80% with FOLFIRI after platinum resistance (mPFS, 4–5.8 months;

mOS, 11–18 months) (62,63). The PRODIGE 41-BEVANEC study

validated FOLFIRI as a second-line option but identified no added

benefit with bevacizumab (23). By

contrast, Bardasi et al (71) demonstrated a lower DCR (44.1%; mOS,

5.9 months; mPFS, 4.4 months), highlighting discrepancies possibly

due to study design or population characteristics. While FOLFIRI

remains feasible after EP failure, its efficacy requires

confirmation in prospective trials with controlled confounding

factors. The NET-02 trial (n=102) compared liposomal irinotecan +

5-fluorouracil versus docetaxel in extrapulmonary NEC. Although no

notable difference in mPFS or mOS was observed, the 6-month PFS

rate doubled (29.6 vs. 13.8%), suggesting subgroup benefits. The

trial failed its primary endpoint, Therefore, the potential

advantage of the liposomal irinotecan combination regimen over

docetaxel remains to be fully elucidated (72).

FOLFOX program

A retrospective study by Hadoux et al

(64) demonstrated antitumor

activity of FOLFOX as second- or third-line therapy in

EP-refractory patients, with a DCR of 64% and <30% incidence of

major hematological toxicity. These findings suggested that FOLFOX

may offer survival benefits with manageable toxicity for aggressive

ENEC lacking backline options.

CAPTEM program

Temozolomide efficacy remains debatable.

Retrospective studies have reported an ORR of 26% and mOS of 22

months with CAPTEM in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic NEC after

first-line failure (60,73). However, a prospective phase II study

of temozolomide monotherapy (B160101021) demonstrated a lower ORR

and mOS with an mPFS of 1.8 months, albeit with minimal toxicity

(74). Notably, MGMT-deficient

patients exhibited partial responses, suggesting that MGMT

deficiency may serve as a potential predictive biomarker for

sensitivity to temozolomide-based chemotherapy. The recent

NCT04122911 trial reported improved outcomes (mPFS, 5.86 months;

mOS, 12.1 months) for second-line temozolomide (75). These findings indicate modest

efficacy and manageable toxicity, particularly in combination or

MGMT-deficient subgroups.

The NCT03387592 trial compared CAPTEM and FOLFIRI in

metastatic NEC. At 12 weeks, DCRs were 39.1% (CAPTEM) and 28.0%

(FOLFIRI), with no notable difference in 12-month survival (28.4

vs. 32.4%). Both regimens demonstrated mild toxicity (<35%

incidence). High microRNA expression was associated with poor

prognosis, offering insights for stratification. Early termination

of the trial (n=53) limited conclusions, but safety and similar

antitumor activity were confirmed (76).

Topoisomerase I inhibitors

Topoisomerase I inhibitor monotherapy lacks notable

efficacy in multiple studies and is not recommended in in major

oncology guidelines, such as the NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine

and Adrenal Tumors (26,68). The NCT02457273 trial evaluated the

novel camptothecin analog TLC388 in EP-refractory metastatic NEC,

demonstrating a DCR of 15% (mPFS, 1.8 months; mOS, 4.3 months). The

trial was halted due to unmet efficacy endpoints. However, MutS

homolog 6 mutations (40% of samples) in the studied cohort of

poorly differentiated NEC (including cases from various primary

sites) have been associated with tumor mutational burden, thus

suggesting potential for targeted therapies (77).

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy inhibits tumor growth and

proliferation by interfering with specific molecular targets. While

molecular-targeted drugs are approved for various solid tumors,

such as non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer and renal cell

carcinoma (78–80), their efficacy in NEC remains to be

elucidated. Current research focuses on mammalian target of

rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors and anti-angiogenic agents. It is

considered that with the continuous development of research,

traditional treatment combined with targeted therapy may provide

hope for patients in the future.

mTOR inhibitors

mTOR, a key kinase regulating cell proliferation,

metabolism and angiogenesis, promotes tumor progression and

represents a potential therapeutic target. Everolimus, an mTOR

inhibitor, has demonstrated limited efficacy as monotherapy in

phase II trials (mPFS, 1.2–1.3 months), but has shown enhanced

antitumor activity in combination regimens (81,82).

The NCT02695459 study reported that everolimus combined with

cisplatin was effective as first-line therapy for advanced

extrapulmonary NEC, which improved quality of life by avoiding

etoposide-related side effects. Subgroup analysis identified three

patients with sustained remission >1 year, suggesting there may

be molecular predictors of sensitivity that remain to be

identified; however, their specific identities remain to be

elucidated due to a lack of correlative biomarker analysis in the

trial (83). Similarly, NCT01317615

reported that everolimus combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel

was effective and well-tolerated in metastatic lung LCNEC (84). In contrast to the potential benefits

of mTOR inhibitors, trials such as PRODIGE 41-BEVANEC did not

report notable survival benefits from the addition of bevacizumab

to FOLFIRI (85).

Antitumor neovascular drugs

Bevacizumab, an anti-angiogenic agent, exhibits

variable efficacy in NEN. Early retrospective studies have

suggested that bevacizumab combined with temozolomide may provide

benefits for patients with poorly differentiated NEC, although

incomplete data have limited conclusions (23,73).

The PRODIGE 41-BEVANEC trial (NCT02820857) identified no survival

difference between FOLFIRI with or without bevacizumab in

platinum-resistant gastrointestinal-pancreatic NEC (6-month OS, 53

vs. 60%) (23). This may reflect

the high Ki-67 index (>55%) and complex angiogenesis of NEC

compared with vascular-dependent NET (G1-G2), which may demonstrate

improved response to bevacizumab. Retrospective studies have

supported combining bevacizumab with FOLFIRI, FOLFOX, FOLFIRINOX or

temozolomide for NET (23,85).

Immunotherapy

Checkpoint inhibitors [PD-1, programmed cell

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and CTLA-4] offer potential but lack

large-scale ENEC-specific evidence (72). Case reports have described complete

remission (CR) when combining immunotherapy with radiotherapy or

targeted agents, such as anlotinib or apatinib (14,15,19,20).

Dual immunotherapy (for example, nivolumab + ipilimumab)

demonstrates promise in high-grade NENs (17,18).

Immunotherapy combined with

radiotherapy

Takagi et al (14) reported complete response in a

patient with metastatic ENEC treated with nivolumab and

radiotherapy, maintaining relapse-free survival for 42 months

despite ≤1% PD-L1 expression, which suggests radiotherapy may

modulate the immune microenvironment. Hanzawa et al

(15) described sustained disease

control in unresectable esophagogastric NEC with nivolumab and

radiotherapy, achieving >4.5-year survival.

Immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy

Based on previous trials of extensive-stage small

cell lung cancer (86–89), immunotherapy combined with

platinum-based chemotherapy has been hypothesized to benefit

gastrointestinal NEC. Ongoing phase II trials (NCT03901378,

NCT03147404 and NCT03352934) are evaluating

pembrolizumab-chemotherapy and avelumab monotherapy. However, the

NET-001/002 trial reported a DCR of only 21% for avelumab in grade

2–3 NEN (90), which underscores

the need for optimized regimens.

Dual immunotherapy

Dual immunotherapy (CTLA-4 + PD-1 inhibition)

targets complementary immune pathways. The SWOG S1609 DART trial

reported a 26% ORR and 32% 6-month PFS with ipilimumab and

nivolumab in high-grade NEN, with manageable toxicity (grade 3/4

alanine aminotransferase elevation was most common) (17). The GETNE 1601 trial achieved a 36.1%

9-month survival rate with durvalumab and tremelimumab in

chemotherapy-refractory gastroenteropancreatic NEN (18). While promising, dual therapy

requires caution due to potential toxicity.

Immunotherapy combined with targeted

therapy

Combining checkpoint inhibitors with multi-target

TKIs such as surufatinib, anlotinib or apatinib demonstrate

promise. Previous studies have reported DCRs of >80% and durable

remission in certain cases (18,21).

The combination benefits from synergistic effects on the tumor

immune microenvironment (91).

Sulfatinib, a multi-target kinase inhibitor [VEGF

receptor VEGFR)1-3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) and

colony stimulating factor 1 receptor], approved for non-pancreatic

NET in China, combined with toripalimab (PD-1 inhibitor) achieved

an 80% DCR (mPFS, 4.1 months; mOS, 13.7 months) in advanced NEC

with manageable toxicity in the NCT04169672 trial (21). No further subgroup analyses were

performed in this trial.

Camrelizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) has demonstrated

efficacy in esophageal cancer, including ENEC. In a specific trial

including patients with esophageal cancer, ORRs ranging from 17.4

to 73.1% and a mOS of 8.3 months were reported, with efficacy

appearing to be influenced by PD-L1 expression and other

biomarkers, such as tumor mutational burden or microsatellite

instability (16). Liu et al

(16) reported camrelizumab

combined with apatinib (VEGFR-2 inhibitor) in third-line ENEC

recurrence, achieving >10-month PFS, which suggests that tumor

microenvironment modulation enhances efficacy.

Anlotinib, a multi-target TKI (VEGFR,

platelet-derived growth factor receptor, FGFR and c-Kit), improved

survival in the ALTER 1202 trial for small cell lung cancer

(92). Zhou et al (19) described a patient with metastatic

ENEC achieving 29-month PFS and >50-month OS with camrelizumab

and anlotinib after chemoradiation failure, reaching CR on

PET/CT.

Tislelizumab (PD-1 inhibitor), which has been

approved for the treatment of multiple malignancies such as

non-small cell lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (93), combined with anlotinib in

second-line metastatic ENEC achieved CR (PFS, 16 months; OS, 21

months) with minimal toxicity in an elderly patient (20).

Targeted-immunotherapy combinations synergistically

regulate the tumor microenvironment, offering a novel strategy to

overcome traditional treatment limitations. While current evidence

derives from small studies or case reports (14–16,19,20),

preliminary data have suggested manageable toxicity and survival

benefits. Future high-quality trials and translational research are

warranted to validate efficacy and optimize personalized

treatment.

Immunotherapy summary

Immunotherapy exploration in ENEC highlights

multidimensional advances. Radiotherapy combinations may enhance

efficacy by modulating the immune microenvironment. Dual

immunotherapy (CTLA-4 + PD-1 inhibition) improves ORR and survival

in high-grade NEN but requires caution regarding toxicity.

Chemotherapy combinations lack randomized trial validation in

gastrointestinal NEC despite success in small cell lung cancer.

Targeted-immunotherapy regimens remodel the tumor microenvironment,

achieving survival benefits. To the best of our knowledge, current

evidence is limited to small studies or case reports with

heterogeneous populations and undefined biomarkers. Future efforts

should prioritize prospective trials, tumor microenvironment

dynamics and epigenetic analyses to establish precision treatment

models and address drug resistance.

Conclusion

ENEC is a rare, highly aggressive gastrointestinal

tumor with diagnosis dependent on pathology and treatment requiring

stratified management. Endoscopic or surgical resection is

preferred in early stages, although curable cases are rare. For

locally advanced disease, neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapy plus surgery

or chemoradiotherapy improves survival. Platinum-based chemotherapy

remains first-line in advanced stages, with individualized

second-line regimens. Emerging therapies, particularly

immunotherapy and targeted therapies, have achieved long-term

remission in individual cases. Future large-scale clinical trials

are warranted to optimize molecular subtyping, refine therapeutic

strategies and improve outcomes for this high-grade malignancy.

Finally, although the exclusive focus on ENEC in the present review

is justified by its distinct biology, the omission of direct

comparisons with other gastrointestinal NECs (such as GNEC)

represents a limitation. Future studies integrating multi-origin

NEC data may help refine both site-specific and common therapeutic

strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Fangyuan Kong

(Department of Oncology, The General Hospital of Western Theater

Command, Chengdu, China) for their perspectives on the

multidisciplinary management of esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma

and Dr Yong Diao (Department of Oncology, The General Hospital of

Western Theater Command) for sharing their clinical experience

regarding immunotherapy in rare malignancies. Their specialized

knowledge enhanced the clinical viewpoints presented in the present

review.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JS and BH conceptualized the present review, curated

the literature, devised the methodology and prepared the original

draft. HZ and CJ contributed to the study conception and data

acquisition, performed systematic literature retrieval, data

extraction and validation, conducted the comparative analysis and

interpretation of data from the included literature, and were

responsible for the design and creation of all tables and figures.

HZ and CJ also participated in drafting and critically reviewing

the manuscript. LZ made substantial contributions to the conception

of the work, participated in drafting the manuscript and provided

critical revision for important intellectual content. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ma Z, Cai H and Cui Y: Progress in the

treatment of esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Tumour Biol.

39:10104283177113132017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fraenkel M, Kim MK, Faggiano A and Valk

GD: Epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 26:691–703. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dasari A, Mehta K, Byers LA, Sorbye H and

Yao JC: Comparative study of lung and extrapulmonary poorly

differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: A SEER database analysis

of 162,983 cases. Cancer. 124:807–815. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of

Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, . Drinking Coffee, Mate, and Very Hot

Beverages. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: pp.

4882018

|

|

5

|

Hirabayashi K, Zamboni G, Nishi T, Tanaka

A, Kajiwara H and Nakamura N: Histopathology of gastrointestinal

neuroendocrine neoplasms. Front Oncol. 3:22013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nevárez A, Saftoiu A and Bhutani MS:

Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: Clinico-

pathological features and therapeutic options. Curr Health Sci J.

37:31–34. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang Q, Fang DC, Yu CG, Zhang J and Chen

MH: Barrett's esophagus-related diseases remain uncommon in China.

J Dig Dis. 12:420–427. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Al Mansoor S, Ziske C and Schmidt-Wolf

IGH: Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: Patient data

metaanalysis and review of the literature. Ger Med Sci.

11:Doc122013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Imai T, Sannohe Y and Okano H: Oat cell

carcinoma (apudoma) of the esophagus: A case report. Cancer.

41:358–364. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Giannetta E, Guarnotta V, Rota F, de Cicco

F, Grillo F, Colao A and Faggiano A; NIKE: A rare rarity:

Neuroendocrine tumor of the esophagus. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

137:92–107. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu H, Yu Z, Liu Y, Guo L, Teng L, Guo L,

Liang L, Wang J, Gao J, Li R, et al: Genomic characterization

reveals distinct mutation landscapes and therapeutic implications

in neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 42:1367–1386. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ji A, Jin R, Zhang R and Li H: Primary

small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: Progression in the last

decade. Ann Transl Med. 8:5022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gonzalez RS: Diagnosis and management of

gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Surg Pathol Clin.

13:377–397. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Takagi K, Kamada T, Fuse Y, Kai W,

Takahashi J, Nakashima K, Nakaseko Y, Suzuki N, Yoshida M, Okada S,

et al: Nivolumab in combination with radiotherapy for metastatic

esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma after esophagectomy: A case

report. Surg Case Rep. 7:2212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hanzawa S, Asami S, Kanazawa T, Oono S and

Takakura N: Multimodal treatment with nivolumab contributes to

long-term survival in a case of unresectable esophagogastric

junction neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cureus. 16:e659812024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu L, Liu Y, Gong L, Zhang M and Wu W:

Salvage camrelizumab plus apatinib for relapsed esophageal

neuroendocrine carcinoma after esophagectomy: A case report and

review of the literature. Cancer Biol Ther. 21:983–989. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Patel SP, Othus M, Chae YK, Giles FJ,

Hansel DE, Singh PP, Fontaine A, Shah MH, Kasi A, Baghdadi TA, et

al: A phase II basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1

blockade in rare tumors (DART SWOG 1609) in patients with

nonpancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 26:2290–2296.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Capdevila J, Teule A, López C,

García-Carbonero R, Benavent M, Custodio A, Cubillo A, Alonso V,

Gordoa TA, Carmona-Bayonas A, et al: 1157O A multi-cohort phase II

study of durvalumab plus tremelimumab for the treatment of patients

(pts) with advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) of

gastroenteropancreatic or lung origin: The DUNE trial (GETNE 1601).

Ann Oncol. 31:S770–S771. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zhou L, Xu G, Chen T, Wang Q, Zhao J,

Zhang T, Duan R and Xia Y: Anlotinib plus camrelizumab achieved

long-term survival in a patient with metastatic esophageal

neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancer Rep (Hoboken).

6:e18552023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang Y, Liu X, Liang H, Liu W, Wang H and

Li T: Late-stage esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma in a patient

treated with tislelizumab combined with anlotinib: A case report. J

Int Med Res. 51:30006052311879422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang P, Shi S, Xu J, Chen Z, Song L,

Zhang X, Cheng Y, Zhang Y, Ye F, Li Z, et al: Surufatinib plus

toripalimab in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumours and

neuroendocrine carcinomas: An open-label, single-arm, multi-cohort

phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. 199:1135392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Borghesani M, Reni A, Lauricella E, Rossi

A, Moscarda V, Trevisani E, Torresan I, Al-Toubah T, Filoni E,

Luchini C, et al: Efficacy and toxicity analysis of mFOLFIRINOX in

high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. J Natl

Compr Canc Netw. 22:e2470052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Walter T, Lievre A, Coriat R, Malka D,

Elhajbi F, Di Fiore F, Hentic O, Smith D, Hautefeuille V, Roquin G,

et al: Bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI after failure of platinum-etoposide

first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced neuroendocrine

carcinoma (PRODIGE 41-BEVANEC): A randomised, multicentre,

non-comparative, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

24:297–306. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Eads JR, Catalano PJ, Fisher GA, Rubin D,

Iagaru A, Klimstra DS, Konda B, Kwong MS, Chan JA, de Jesus-Acosta

A, et al: Randomized phase II study of platinum and etoposide (EP)

versus temozolomide and capecitabine (CAPTEM) in patients (pts)

with advanced G3 non-small cell gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEPNENs): ECOG-ACRIN EA2142. J Clin

Oncol. 40 (16_suppl):S40202022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Morizane C, Machida N, Honma Y, Okusaka T,

Boku N, Kato K, Nomura S, Hiraoka N, Sekine S, Taniguchi H, et al:

Effectiveness of etoposide and cisplatin vs irinotecan and

cisplatin therapy for patients with advanced neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the digestive system: The TOPIC-nec phase 3 randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 8:1447–1455. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Weaver JMJ, Hubner RA, Valle JW and

McNamara MG: Selection of chemotherapy in advanced poorly

differentiated extra-pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancers

(Basel). 15:49512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, : The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang L, Sun X, Zou Y and Meng X: Small

cell type neuroendocrine carcinoma colliding with squamous cell

carcinoma at esophagus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7:1792–1795.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wilson CI, Summerall J, Willis I, Lubin J

and Inchausti BC: Esophageal collision tumor (Large cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma and papillary carcinoma) arising in a

Barrett esophagus. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 124:411–415. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Maru DM, Khurana H, Rashid A, Correa AM,

Anandasabapathy S, Krishnan S, Komaki R, Ajani JA, Swisher SG and

Hofstetter WL: Retrospective study of clinicopathologic features

and prognosis of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the

esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 32:1404–1411. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Klöppel G: Classification and pathology of

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat

Cancer. 18 (Suppl 1):S1–S16. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Capelli P, Fassan M and Scarpa A:

Pathology-grading and staging of GEP-NETs. Best Pract Res Clin

Gastroenterol. 26:705–717. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rooper LM, Bishop JA and Westra WH: INSM1

is a sensitive and specific marker of neuroendocrine

differentiation in head and neck tumors. Am J Surg Pathol.

42:665–671. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang D, Zhang GB, Yan L, Wei XE, Zhang YZ

and Li WB: CT and enhanced CT in diagnosis of gastrointestinal

neuroendocrine carcinomas. Abdom Imaging. 37:738–745. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Schott M, Klöppel G, Raffel A, Saleh A,

Knoefel WT and Scherbaum WA: Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the

gastrointestinal tract. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 108:305–312.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Islam O, Sarti K, Verbruggen L,

Vandersmissen V, Bulcke KV, Annys L, Verslype C, Van Laethem JL,

Kalantari HR, Janssens J, et al: Management of high-grade

neuroendocrine neoplasms: Impact of functional imaging. Endocr

Relat Cancer. 32:e2402312025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sahani DV, Bonaffini PA, Fernández-Del

Castillo C and Blake MA: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors: Role of imaging in diagnosis and management. Radiology.

266:38–61. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E,

Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, Mittra E, Kunz PL, Kulke MH, Jacene H,

et al: Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine

tumors. N Engl J Med. 376:125–135. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chan DS, Kanagaratnam AL, Pavlakis N and

Chan DL: Peptide receptor chemoradionuclide therapy for

neuroendocrine neoplasms: A systematic review. J Neuroendocrinol.

37:e133552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lee CG, Lim YJ, Park SJ, Jang BI, Choi SR,

Kim JK, Kim YT, Cho JY, Yang CH, Chun HJ, et al: The clinical

features and treatment modality of esophageal neuroendocrine

tumors: A multicenter study in Korea. BMC Cancer. 14:5692014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Fukui H, Dohi O, Miyazaki H, Yasuda T,

Yoshida T, Ishida T, Doi T, Hirose R, Inoue K, Harusato A, et al: A

case of endoscopic submucosal dissection for neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the esophagus with invasion to the muscularis mucosae.

Clin J Gastroenterol. 15:339–344. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheng YQ, Wang GF, Zhou XL, Lin M, Zhang

XW and Huang Q: Early adenocarcinoma mixed with a neuroendocrine

carcinoma component arising in the gastroesophageal junction: A

case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 16:563–570. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Vest M, Shah D, Nassar M and Niknam N:

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus with liver metastasis: A

case report. Cureus. 14:e288422022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Honma Y, Nagashima K, Hirano H, Shoji H,

Iwasa S, Takashima A, Okita N, Kato K, Boku N, Murakami N, et al:

Clinical outcomes of locally advanced esophageal neuroendocrine

carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Med. 9:595–604.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Alese OB, Jiang R, Shaib W, Wu C, Akce M,

Behera M and El-Rayes BF: High-grade gastrointestinal

neuroendocrine carcinoma management and outcomes: A national cancer

database study. Oncologist. 24:911–920. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Enjoji T, Kobayashi S, Hayashi K, Tetsuo

H, Matsumoto R, Maruya Y, Araki T, Honda T, Akazawa Y, Kanetaka K,

et al: Long-term survival after conversion surgery for an

esophageal neuroendocrine carcinoma: A case report. Gen Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg Cases. 3:282024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM,

van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, van Laarhoven

HWM, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Hospers GAP, Bonenkamp JJ, et al:

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for

oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): Long-term results of a

randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 16:1090–1098. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ito T, Masui T, Komoto I, Doi R, Osamura

RY, Sakurai A, Ikeda M, Takano K, Igarashi H, Shimatsu A, et al:

JNETS clinical practice guidelines for gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up: A

synopsis. J Gastroenterol. 56:1033–1044. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kikuchi Y, Shimada H, Yamaguchi K and

Igarashi Y: Systematic review of case reports of Japanese

esophageal neuroendocrine cell carcinoma in the Japanese

literature. Int Cancer Conf J. 8:47–57. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Awada H, Ali AH, Bakhshwin A and Daw H:

High-grade large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: A

case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep.

17:1442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shah MH, Goldner WS, Benson AB, Bergsland

E, Blaszkowsky LS, Brock P, Chan J, Das S, Dickson PV, Fanta P, et

al: Neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors, version 2.2021, NCCN

clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

19:839–868. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wong AT, Shao M, Rineer J, Osborn V,

Schwartz D and Schreiber D: Treatment and survival outcomes of

small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: An analysis of the National

cancer data base. Dis Esophagus. 30:1–5. 2017.

|

|

54

|

Moertel CG, Kvols LK, O'Connell MJ and

Rubin J: Treatment of neuroendocrine carcinomas with combined

etoposide and cisplatin. Evidence of major therapeutic activity in

the anaplastic variants of these neoplasms. Cancer. 68:227–232.

1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yamaguchi T, Machida N, Morizane C, Kasuga

A, Takahashi H, Sudo K, Nishina T, Tobimatsu K, Ishido K, Furuse J,

et al: Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy

for advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system.

Cancer Sci. 105:1176–1181. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

McNamara MG, Frizziero M, Jacobs T,

Lamarca A, Hubner RA, Valle JW and Amir E: Second-line treatment in

patients with advanced extra-pulmonary poorly differentiated

neuroendocrine carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ther Adv Med Oncol. 12:17588359209152992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ooki A, Osumi H, Fukuda K and Yamaguchi K:

Potent molecular-targeted therapies for gastro-entero-pancreatic

neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 42:1021–1054.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Imai H, Shirota H, Okita A, Komine K,

Saijo K, Takahashi M, Takahashi S, Takahashi M, Shimodaira H and

Ishioka C: Efficacy and safety of carboplatin and etoposide

combination chemotherapy for extrapulmonary neuroendocrine

carcinoma: A retrospective case series. Chemotherapy. 61:111–116.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, Vestermark

LW, Holt N, Osterlund P, Dueland S, Hofsli E, Guren MG, Ohrling K,

et al: Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival

in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine

carcinoma (WHO G3): The NORDIC NEC study. Ann Oncol. 24:152–160.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chan DL, Bergsland EK, Chan JA, Gadgil R,

Halfdanarson TR, Hornbacker K, Kelly V, Kunz PL, McGarrah PW, Raj

NP, et al: Temozolomide in grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms: A multicenter retrospective review.

Oncologist. 26:950–955. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Butt BP, Stokmo HL, Ladekarl M, Tabaksblat

EM, Sorbye H, Revheim ME and Hjortland GO: 1108P Folfirinox in the

treatment of advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

carsinomas. ESMO. 32:S9152021.

|

|

62

|

Hentic O, Hammel P, Couvelard A, Rebours

V, Zappa M, Palazzo M, Maire F, Goujon G, Gillet A, Lévy P, et al:

FOLFIRI regimen: An effective second-line chemotherapy after

failure of etoposide-platinum combination in patients with

neuroendocrine carcinomas grade 3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 19:751–757.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Sugiyama K, Shiraishi K, Sato M, Nishibori

R, Nozawa K and Kitagawa C: Salvage chemotherapy by folfiri regimen

for poorly differentiated gastrointestinal neuroendocrine

carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 52:947–951. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Hadoux J, Malka D, Planchard D, Scoazec

JY, Caramella C, Guigay J, Boige V, Leboulleux S, Burtin P,

Berdelou A, et al: Post-first-line FOLFOX chemotherapy for grade 3

neuroendocrine carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:289–298. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Merola E, Dal Buono A, Denecke T, Arsenic

R, Pape UF, Jann H, Wiedenmann B and Pavel ME: Efficacy and

toxicity of 5-Fluorouracil-Oxaliplatin in gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms. Pancreas. 49:912–917. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Du Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Wen F and Li Q:

First-line irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin

for high-grade metastatic gastrointestinal neuroendocrine

carcinoma. Tumori. 99:57–60. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Lamarca A, Frizziero M, Barriuso J,

McNamara MG, Hubner RA and Valle JW: Urgent need for consensus:

International survey of clinical practice exploring use of

platinum-etoposide chemotherapy for advanced extra-pulmonary high

grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (EP-G3-NEC). Clin Transl Oncol.

21:950–953. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Shah MH, Goldner WS, Benson AB, Bergsland

E, Blaszkowsky LS, Brock P, Chan J, Das S, Dickson PV, Fanta P, et

al: Neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors, version 2.2021, NCCN

clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

19:839–868. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Frizziero M, Spada F, Lamarca A, Kordatou

Z, Barriuso J, Nuttall C, McNamara MG, Hubner RA, Mansoor W,

Manoharan P, et al: Carboplatin in combination with oral or

intravenous etoposide for extra-pulmonary, poorly-differentiated

neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 109:100–112. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Hadoux J, Walter T, Kanaan C, Hescot S,

Hautefeuille V, Perrier M, Tauveron I, Laboureau S, Do Cao C,

Petorin C, et al: Second-line treatment and prognostic factors in

neuroendocrine carcinoma: the RBNEC study. Endocr Relat Cancer.

29:569–580. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Bardasi C, Spallanzani A, Benatti S, Spada

F, Laffi A, Antonuzzo L, Lavacchi D, Marconcini R, Ferrari M,

Rimini M, et al: Irinotecan-based chemotherapy in extrapulmonary

neuroendocrine carcinomas: Survival and safety data from a

multicentric Italian experience. Endocrine. 74:707–713. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

McNamara MG, Swain J, Craig Z, Sharma R,

Faluyi O, Wadsley J, Morgan C, Wall LR, Chau I, Reed N, et al:

NET-02: A randomised, non-comparative, phase II trial of

nal-IRI/5-FU or docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with

progressive poorly differentiated extra-pulmonary neuroendocrine

carcinoma. EClinicalMedicine. 60:1020152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Welin S, Sorbye H, Sebjornsen S, Knappskog

S, Busch C and Oberg K: Clinical effect of temozolomide-based

chemotherapy in poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma after

progression on first-line chemotherapy. Cancer. 117:4617–4622.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kobayashi N, Takeda Y, Okubo N, Suzuki A,

Tokuhisa M, Hiroshima Y and Ichikawa Y: Phase II study of

temozolomide monotherapy in patients with extrapulmonary

neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 112:1936–1942. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

von Arx C, Della Vittoria Scarpati G,

Cannella L, Clemente O, Marretta AL, Bracigliano A, Picozzi F,

Iervolino D, Granata V, Modica R, et al: A new schedule of one week

on/one week off temozolomide as second-line treatment of advanced

neuroendocrine carcinomas (TENEC-TRIAL): A multicenter, open-label,

single-arm, phase II trial. ESMO Open. 9:1030032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Bongiovanni A, Liverani C, Foca F, Bergamo

F, Leo S, Pusceddu S, Gelsomino F, Brizzi MP, Di Meglio G, Spada F,

et al: A randomized phase II trial of Captem or Folfiri as

second-line therapy in neuroendocrine carcinomas. Eur J Cancer.

208:1141292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chen MH, Chou WC, Hsiao CF, Jiang SS, Tsai

HJ, Liu YC, Hsu C, Shan YS, Hung YP, Hsich CH, et al: An

open-label, single-arm, two-stage, multicenter, phase II study to

evaluate the efficacy of TLC388 and genomic analysis for poorly

differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Oncologist. 25:e782–e788.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH,

Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, et

al: Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary

adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 361:947–957. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs

H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M,

et al: Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2

for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med.

344:783–792. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P,

Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik

C, Kim ST, et al: Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic

renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 356:115–124. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Okuyama H, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Furukawa M,

Ohkawa S, Hosokawa A, Kojima Y, Hara H, Murohisa G, Shioji K, et

al: A phase II trial of everolimus in patients with advanced

pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma refractory or intolerant to

platinum-containing chemotherapy (NECTOR Trial).

Neuroendocrinology. 110:988–993. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Tarhini A, Kotsakis A, Gooding W, Shuai Y,

Petro D, Friedland D, Belani CP, Dacic S and Argiris A: Phase II

study of everolimus (RAD001) in previously treated small cell lung

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 16:5900–5907. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Levy S, Verbeek WHM, Eskens FALM, van den

Berg JG, de Groot DJA, van Leerdam ME and Tesselaar MET: First-line

everolimus and cisplatin in patients with advanced extrapulmonary

neuroendocrine carcinoma: A nationwide phase 2 single-arm clinical

trial. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 14:175883592210770882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Christopoulos P, Engel-Riedel W, Grohé C,

Kropf-Sanchen C, von Pawel J, Gütz S, Kollmeier J, Eberhardt W,

Ukena D, Baum V, et al: Everolimus with paclitaxel and carboplatin

as first-line treatment for metastatic large-cell neuroendocrine

lung carcinoma: a multicenter phase II trial. Ann Oncol.

28:1898–1902. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Ünal Ç and Sağlam S: Metronomic

Temozolomide (mTMZ) and Bevacizumab-The Safe and Effective Frontier

for Treating Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs): A

Single-Center Experience. Cancers (Basel). 23:56882023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L,

Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, Huemer F, Losonczy G, Johnson ML, Nishio

M, et al: First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in

extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med.

379:2220–2229. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Liu SV, Reck M, Mansfield AS, Mok T,

Scherpereel A, Reinmuth N, Garassino MC, De Castro Carpeno J,

Califano R, Nishio M, et al: Updated overall survival and PD-L1

subgroup analysis of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung

cancer treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide

(IMpower133). J Clin Oncol. 39:619–630. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N,

Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, Hochmair MJ, Özgüroğlu M, Ji JH,

et al: Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide

in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer

(CASPIAN): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 394:1929–1939. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Goldman JW, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N,

Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, Hochmair MJ, Özgüroğlu M, Ji JH,

et al: Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus

platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line

treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN):

Updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3

trial. Lancet Oncol. 22:51–65. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Chan DL, Rodriguez-Freixinos V, Doherty M,

Wasson K, Iscoe N, Raskin W, Hallet J, Myrehaug S, Law C, Thawer A,

et al: Avelumab in unresectable/metastatic, progressive, grade 2–3

neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs): Combined results from NET-001 and

NET-002 trials. Eur J Cancer. 169:74–81. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Reddy SM, Reuben A and Wargo JA:

Influences of BRAF inhibitors on the immune microenvironment and

the rationale for combined molecular and immune targeted therapy.

Curr Oncol Rep. 18:422016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Cheng Y, Wang Q, Li K, Shi J, Liu Y, Wu L,

Han B, Chen G, He J, Wang J, et al: Anlotinib vs placebo as third-

or further-line treatment for patients with small cell lung cancer:

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 study. Br J

Cancer. 125:366–371. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Wang J, Lu S, Yu X, Hu Y, Sun Y, Wang Z,

Zhao J, Yu Y, Hu C, Yang K, et al: Tislelizumab plus chemotherapy

vs chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for advanced squamous

non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase 3 randomized clinical trial.

JAMA Oncol. 7:709–717. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|