Introduction

Recent advancements in imaging techniques include

positron emission tomography (PET) with [18F]

2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), which has been widely used for

clinical molecular imaging (1,2).

Several studies have described its usefulness in detecting primary

tumors and metastases for several types of cancer (3,4). In

particular, previous studies reported the increased FDG uptake in

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lesions (5). However, the sensitivity of HCC

detection with FDG-PET is only 50–55% (6–8), which

is significantly lower than the 98% detection rate for liver

metastasis from colorectal cancer (9). FDG-PET is therefore less useful for

detecting primary HCC lesions than conventional ultrasonography or

computed tomography.

Nevertheless, FDG-PET has received considerable

attention as a new modality with the ability to estimate the

malignant potential of tumors. Several studies have demonstrated

that FDG accumulation reflects tumor aggressiveness and predicts

poor survival (10–12). Therefore, FDG-PET has been used to

evaluate the malignant potential of tumors after chemotherapy

(13). New molecular-targeted

cancer therapies [such as vascular endothelial growth factor

inhibitor (bevacizumab) and epidermal growth factor receptor

inhibitor (cetuximab)] require new methods for monitoring treatment

progress (14), as they exert

cytostatic instead of the cytoreductive effects of traditional

chemotherapy. Compared with computed tomography, FDG-PET provides

information on tumor response to bevacizumab therapy earlier

(15). The multiple kinase

inhibitor sorafenib is a new molecular-targeted therapy approved

for the treatment of HCC. Given the strong FDG uptake observed in

HCC tumors, FDG-PET may be useful for evaluating the cytostatic

effects of this type of therapy (16).

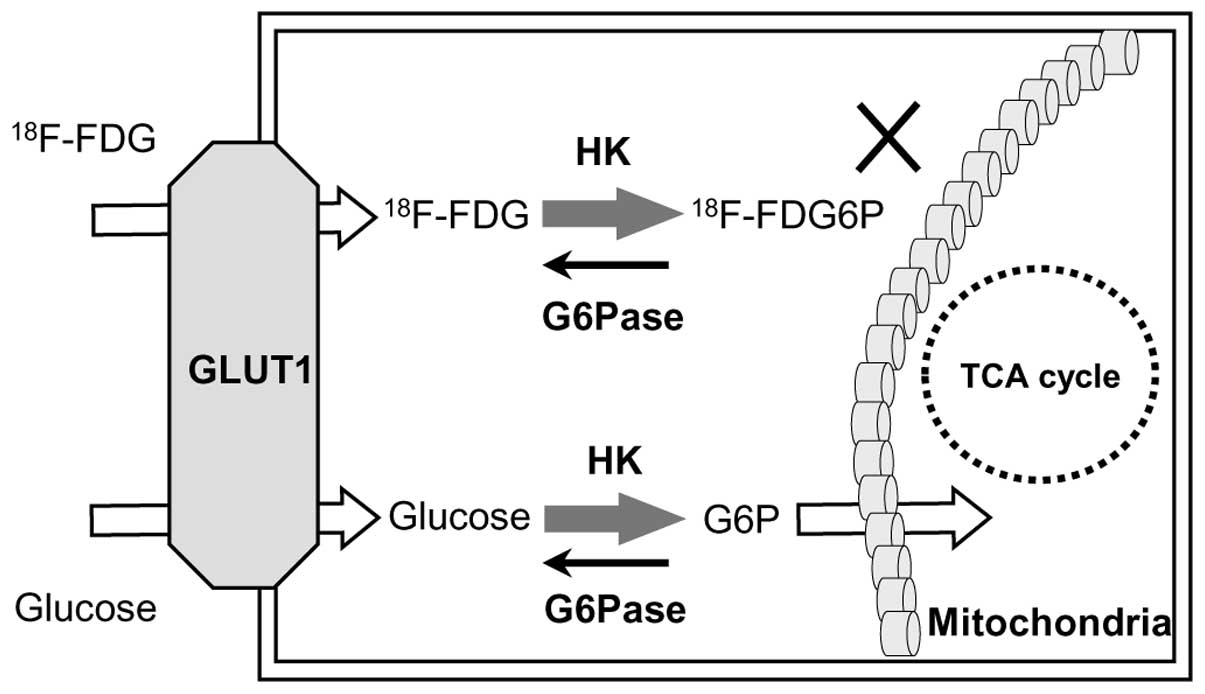

The molecular mechanisms involved in FDG imaging

relate to its uptake by glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and

metabolism by hexokinase (HK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase).

FDG accumulates in malignant cells via GLUT1 transport and HK

phosphorylation, as shown in Fig. 1

(17). G6Pase, a gluconeogenesis

enzyme strongly expressed in the liver (17,18),

counteracts HK phosphorylation by converting glucose-6-phosphate to

glucose. High G6Pase levels therefore reduce FDG accumulation by

accelerating the conversion of FDG-6-phosphate to FDG, leading to

its release from cells.

Although previous studies have evaluated the

molecular mechanisms underlying FDG-PET, most relied on

non-quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis such as positive or

negative staining. Since interpretation of these results is

subjective, it is difficult to determine the precise relationship

between the standardized uptake value (SUV) and glucose

metabolism-related protein levels. To determine the mechanisms

responsible for low FDG-PET efficacy in HCC, we evaluated glucose

metabolism-related protein expression in HCC with that of another

type of liver cancer (liver metastasis from colorectal cancer)

using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

(qRT-PCR). We then evaluated the relationship between protein

expression and SUV in each type of liver cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study included 34 patients with liver

cancer (21 male and 13 female; mean age ± SEM, 67.6±1.7 years) who

underwent FDG-PET prior to surgery in our hospital. Of these

patients, 20 had HCC (HCC group) and 14 had liver metastasis from

colorectal cancer (Meta group). Specimens consisting of the tumors

and surrounding normal liver tissue were immediately snap-frozen in

liquid nitrogen after surgical resection and stored at −80ºC. These

specimens were later thawed for isolation and analysis of mRNA

levels. Of the 20 HCC cases, 16 were moderately differentiated

(M/D) HCC, and four were poorly differentiated (P/D) HCC. The

protocol was approved by the institutional review board and all

patients provided written informed consent.

PET imaging

FDG-PET images were acquired with a PET scanner

(ECAT EXACT HR+, Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN, USA).

Patients fasted at least 5 h before FDG injection. Images were

reviewed on a Sun Microsystems workstation (Siemens/CTI) along

transverse, coronal, and sagittal planes with maximum intensity

projection images. The images were interpreted independently by two

experienced nuclear medicine physicians blinded to the clinical

data. Tumor lesions were identified as areas of focally increased

FDG uptake exceeding that of the surrounding normal tissue. A

region of interest was placed over each lesion to include the

highest levels of radioactivity. The maximum SUV was calculated

with the following formula: SUV = cdc/(di/w), where cdc is the

decay-corrected tracer tissue concentration (Bq/g), di is the

injected dose (Bq), and w is the body weight of the patient

(g).

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed to

determine levels of GLUT1 and GLUT2 in the liver cancer specimens.

Briefly, resected specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin

solution, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (4 μm). Slides were

incubated overnight at room temperature with primary rabbit

polyclonal antibodies against GLUT1 or GLUT2 (1:200 dilution).

Avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex staining was performed according

to the manufacturer’s instructions (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). Finally, the nuclei were counterstained with

hematoxylin.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the specimens by

guanidinium isothiocyanate-acid phenol extraction and quantified by

absorbance at 260 nm. Reverse transcription was carried out with 1

μg RNA, and the resulting cDNA was analyzed by real-time PCR with

Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and the ABI Prism 7000 (Applied

Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). Target-specific oligonucleotide

primers and probes were previously described (19,20).

As endogenous control, the amplification of 18S rRNA was used. The

relative value of mRNA expression indicates the ratio of the mRNA

expression to mean mRNA levels in normal liver after 18S rRNA

normalization. Primers and probes for 18S rRNA were obtained in a

Pre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagent kit (Applied Biosystems,

Stockholm, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. SUV values were

compared by Student’s t-test. Multiple one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) was used to assess differences in mRNA levels. Correlation

analyses were performed with the Spearman’s rank correlation test.

P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistically

significant differences.

Results

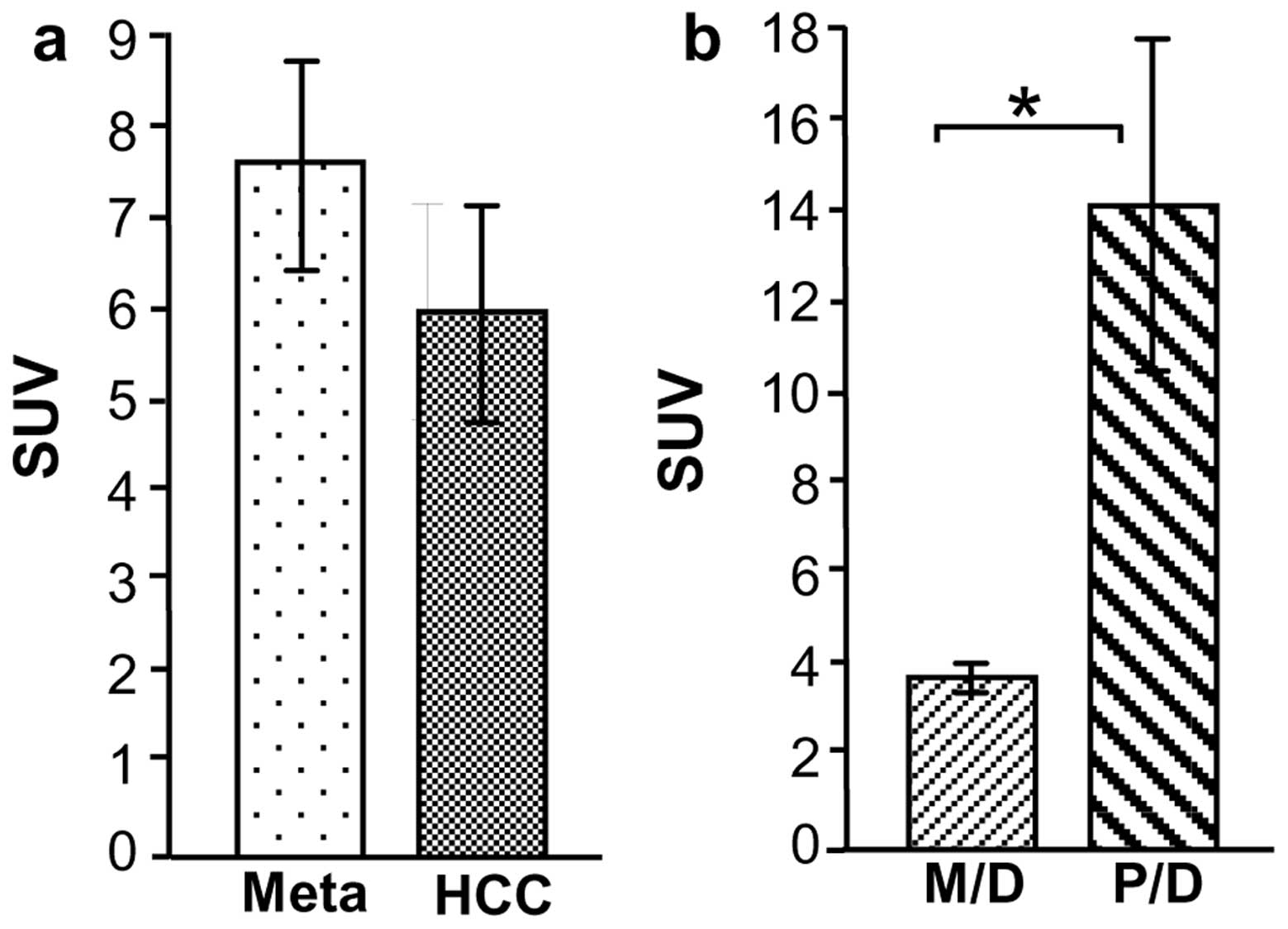

Tumor detection and SUV with FDG-PET

FDG-PET detected 15/20 HCC lesions (SUV, 6.1±1.2)

and 13/14 Meta lesions (SUV, 7.7±1.1) (Fig. 2a). Of the HCC cases, all four P/D

HCC lesions were detected by FDG-PET with a high mean SUV

(14.4±3.7). By contrast, 11/16 M/D HCC lesions were detected by

FDG-PET, and the mean SUV (4.0±0.3) was significantly lower than

that of P/D HCC (P<0.0001) (Fig.

2b).

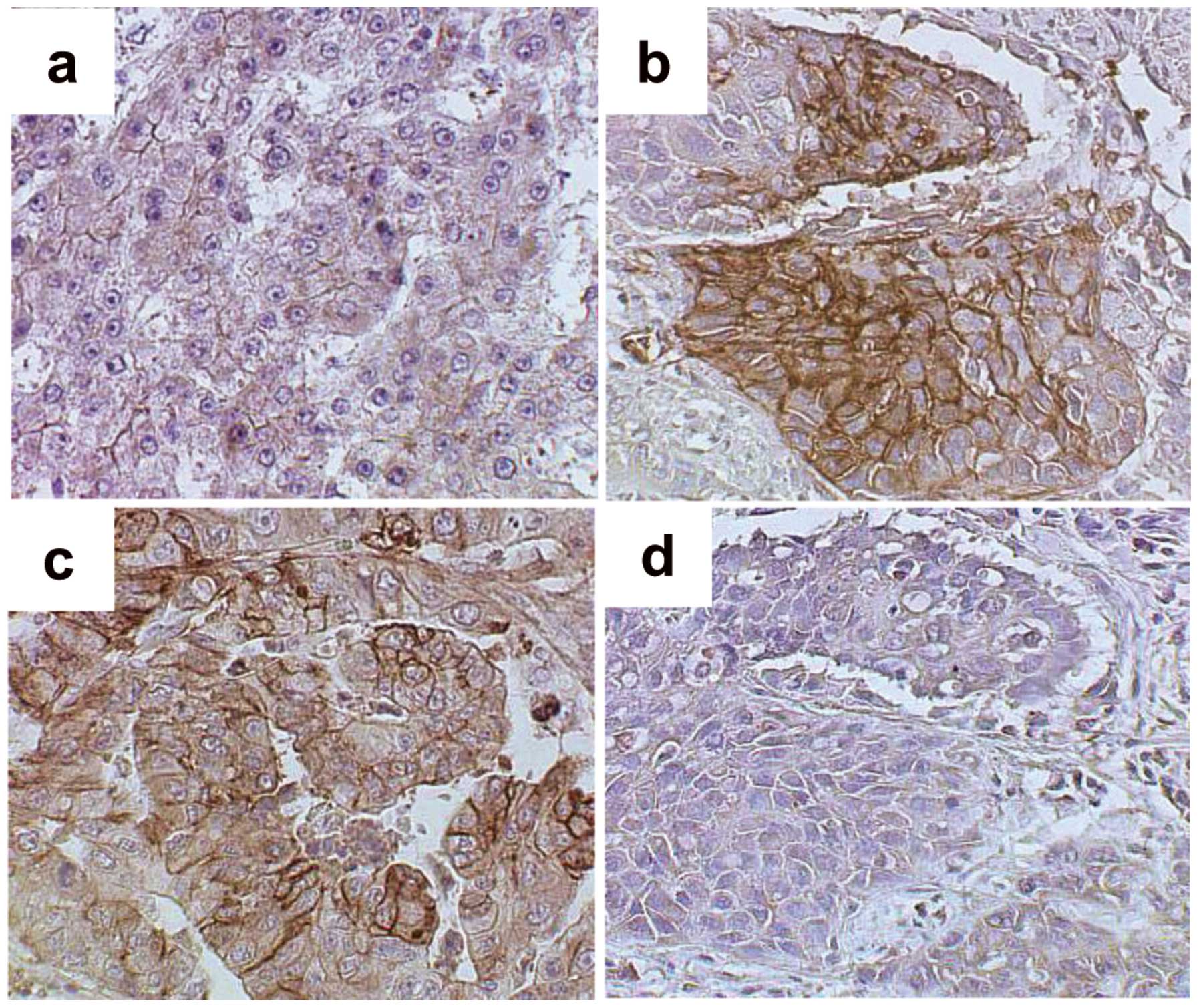

Immunohistochemical analysis of GLUT1 and

GLUT2

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying FDG

accumulation in liver cancer, tumor levels of GLUT1 and GLUT2 were

evaluated. The M/D HCC cell membranes showed only weak staining

with GLUT1 antibody (Fig. 3a), but

P/D HCC and Meta specimens showed relatively strong GLUT1 membrane

staining (Fig. 3b and c). Staining

with the GLUT2 antibody was not observed in P/D HCC cells (Fig. 3d).

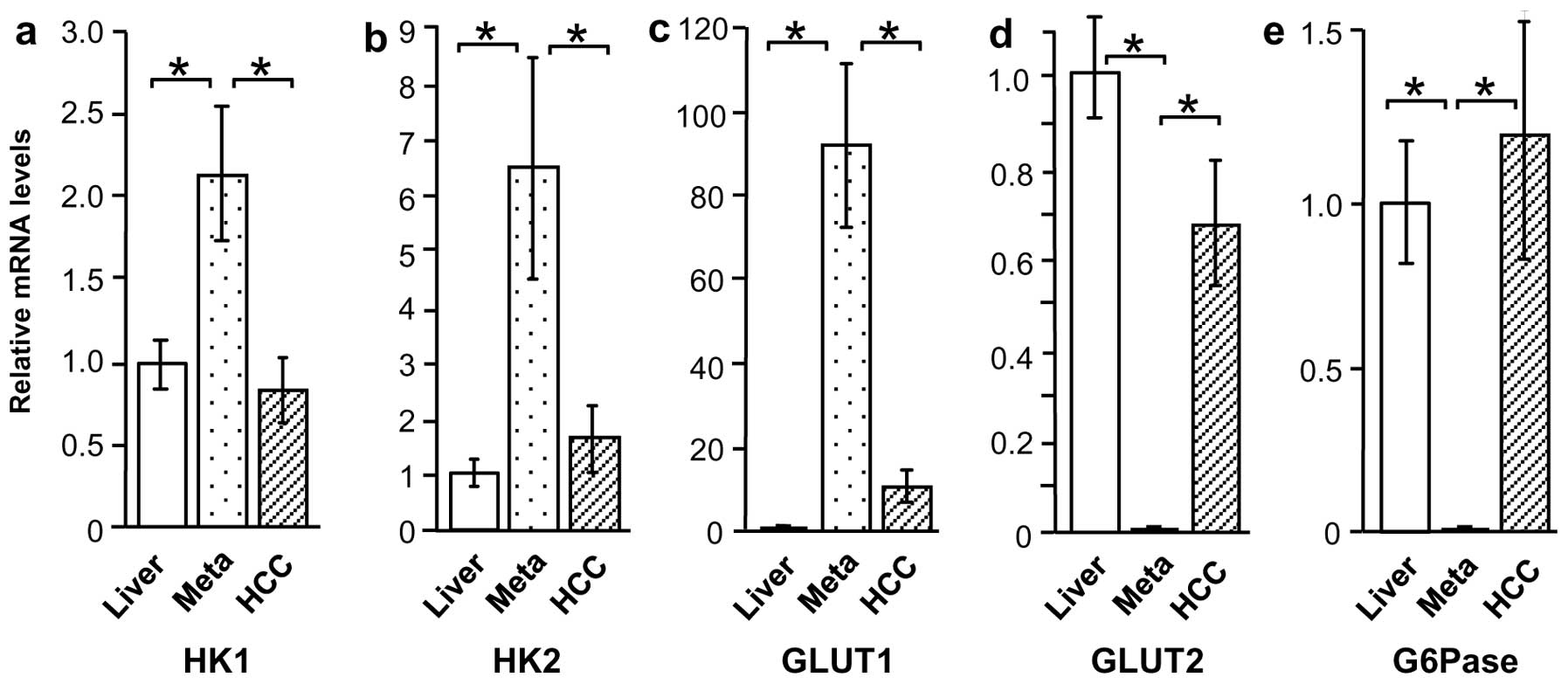

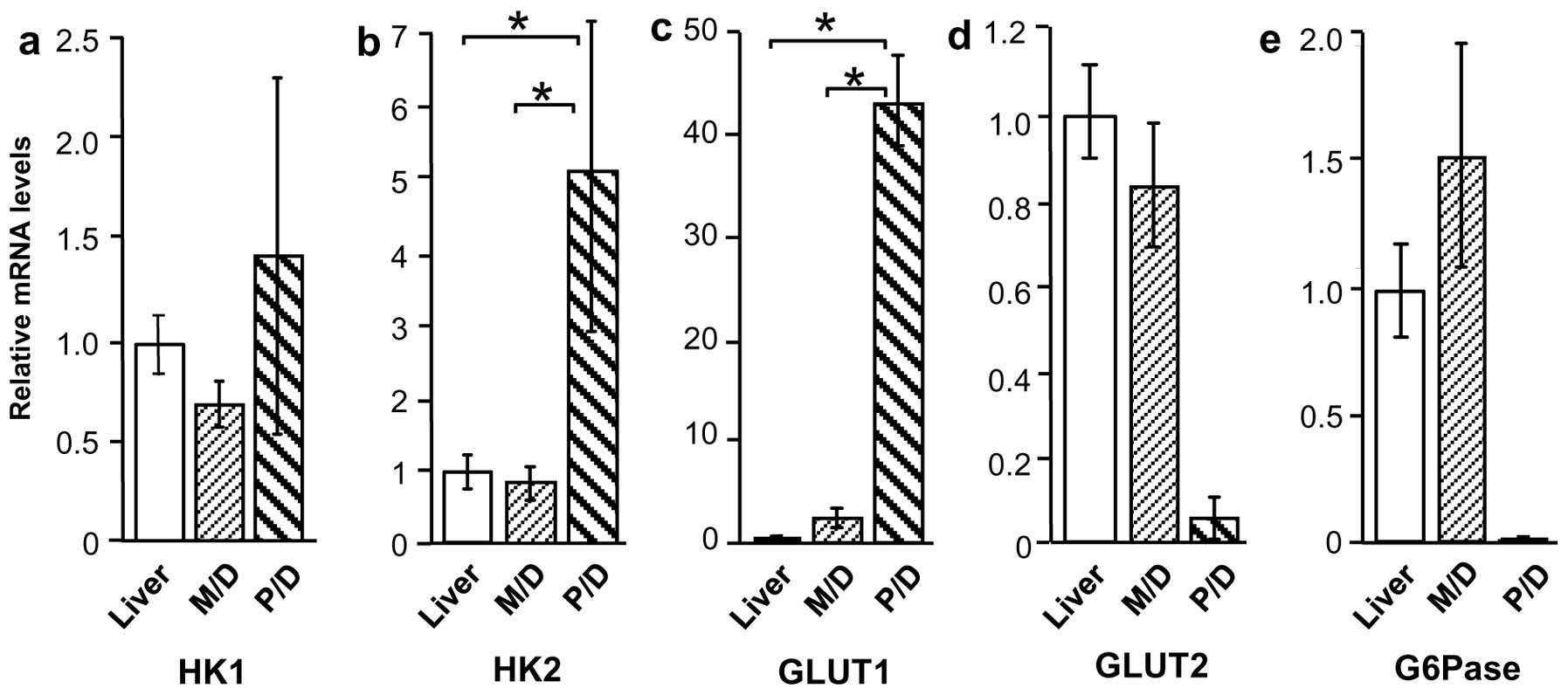

HK1, HK2, GLUT1, GLUT2, and G6Pase mRNA

levels in liver cancer and normal liver tissue

Based on the immunostaining results, the tissue

specimens were evaluated by qRT-PCR to determine expression of

glucose metabolism-related proteins GLUT1, GLUT2, HK1, HK2, and

G6Pase. Compared with normal liver tissue, HK1 and HK2 mRNA levels

were higher in Meta specimens (P<0.01), but were unchanged in

HCC specimens (Fig. 4a and b).

Similarly, GLUT1 expression was higher in Meta specimens than in

normal liver tissue (P<0.01), but was not significantly higher

in HCC specimens (Fig. 4c). By

contrast, GLUT2 and G6Pase mRNA levels were considerably lower in

Meta specimens (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) than in

normal tissue, but were unchanged in HCC specimens (Fig. 4d and e).

HK1, HK2, GLUT1, GLUT2, and G6Pase mRNA

levels according to HCC differentiation

Expression of glucose metabolism-related proteins in

M/D HCC and P/D HCC was also compared, revealing a considerable

difference in expression patterns. Although HK1 mRNA levels were

similar in the two groups, HK2 and GLUT1 mRNA levels were higher in

P/D HCC compared with M/D HCC and normal liver tissue (P<0.01)

(Fig. 5a–c). By contrast, GLUT2 and

G6Pase appeared to be lower in P/D HCC (18- and 142-fold,

respectively), but this increase was not significant (Fig. 5d and e).

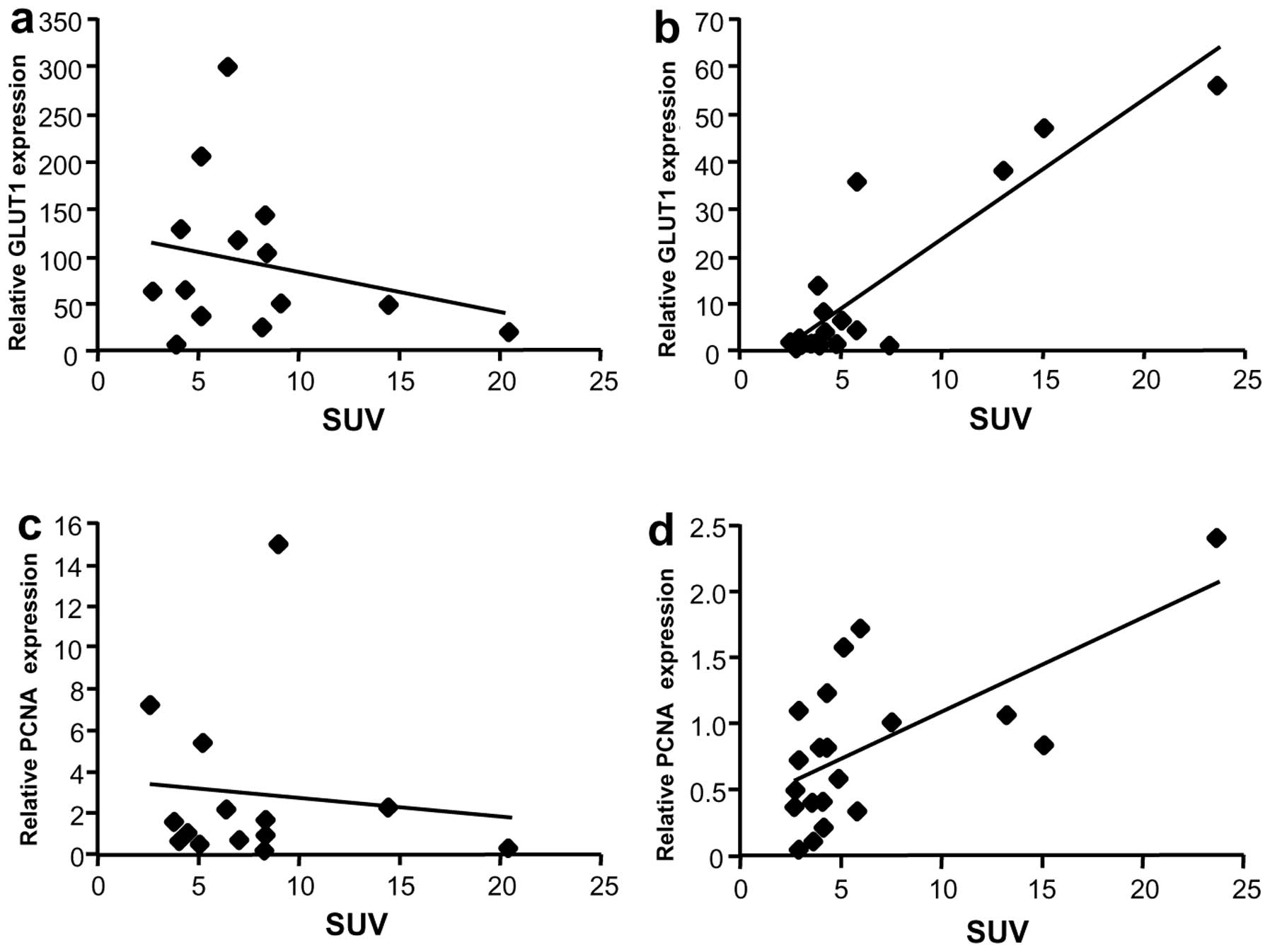

Correlation between SUV and mRNA levels

of GLUT1 or proliferating cell nuclear antigen

Since GLUT1 is overexpressed in liver cancer, the

relationship between GLUT1 mRNA expression and SUV was evaluated.

Although GLUT1 mRNA levels were not associated with SUV in the Meta

group (Fig. 6a), a correlation was

observed in the HCC group (rs=0.69, P=0.002) (Fig. 6b). To further evaluate the

relationship between SUV and tumor growth, mRNA levels of a

proliferation marker, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA),

were analyzed. No correlation was observed between PCNA mRNA levels

and SUV in Meta specimens (Fig.

6c), but a weak correlation was observed in HCC specimens

(Fig. 6d, rs=0.58, P=0.01).

Discussion

FDG-PET is used for diagnosis and tumor staging

essential for appropriate cancer management. However, FDG

accumulation is low in HCC tumors compared with other types of

cancer, such as lung cancer or malignant lymphoma (21,22).

Therefore, we investigated the mechanisms underlying FDG

accumulation by comparing two major forms of liver cancer, HCC and

colorectal cancer liver metastasis (Meta). We found that SUV

correlated with GLUT1 expression in HCC but not Meta specimens.

This finding may be due to the lower GLUT1 expression in HCC

tumors, particularly M/D HCC cases. Compared with surrounding

normal liver tissue, GLUT1 levels were 11-fold higher in HCC

specimens and 92-fold higher in Meta specimens. Thus, the number of

GLUT1 receptors in Meta tumors likely exceeds the requirements for

maximum FDG transport, accounting for the lack of association

between SUV and GLUT1 expression. The lower GLUT1 levels in HCC

suggest that this transporter may still be a rate-limiting factor

for FDG uptake, with the SUV dependent on GLUT1 increase.

SUV also correlated with tumor growth (assessed by

PCNA expression) in HCC specimens but not Meta specimens. The

increased energy provided by GLUT1 overexpression likely plays a

role in both HCC and Meta tumor growth; therefore, the reason for

the contrasting PCNA results is unclear. However, the PCNA

expression in Meta specimens was consistent with a previous study

(20). These results indicate that

SUV cannot always estimate tumor growth or prognosis in the

patients with liver metastasis of colorectal cancer.

GLUT1 is responsible for the cell basal glucose

requirements. The role of GLUT1 as the primary transporter in FDG

uptake for HCC is controversial as there are >10 GLUT family

isoforms, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and have

specific roles (23). Paudyal et

al (24) reported GLUT2

expression in 71% of HCCs and GLUT1 expression in only 16% of HCCs.

Roh et al (25) reported

that GLUT1 was expressed in 81.3% of cholangiocarcinomas but only

4.5% of HCCs. Taken together, these immunohistochemical studies

indicate that GLUT1 overexpression does not occur in all HCCs

(24). Our immunohistochemical

results showed relatively strong GLUT2 expression in HCC specimens;

however, the qRT-PCR results demonstrated that GLUT2 expression was

similar to that of the surrounding normal liver tissue. By

contrast, GLUT1 was clearly overexpressed in HCC in the present

study, with levels ~11-fold higher than those of the surrounding

normal tissue.

GLUT2 is expressed in hepatocytes, pancreatic β

cells, and the basolateral membranes of intestinal and renal

epithelial cells (26). In the

liver, GLUT2 expressed on hepatocyte membranes allows for the

bidirectional glucose transport, allowing glucose flux in and out

of cells (27). Unlike other GLUT

family members, GLUT2 is important for sensing glucose

concentration in the pancreas, intestinal glucose uptake, glucose

resorption by the kidney, and glucose uptake and release in the

liver (28). In humans, the

physiological glucose concentration is 5.6 mmol/l, and the GLUT1

and GLUT2 Michaelis constants are <20 mmol/l and 40 mmol/l,

respectively (28). Thus, GLUT1 has

a higher affinity for glucose than GLUT2, indicating that GLUT1

overexpression may provide a major advantage regarding glucose

uptake in cancer cells in the liver.

Previous studies reported that HK overexpression

also contributes to strong FDG uptake in HCC (29,30).

In this study, the mRNA levels of HK1 and HK2 were higher in Meta

specimens than in HCC specimens. The difference in HKs was

relatively small compared with the large difference in GLUT1

expression of the Meta or HCC. However, this transport protein may

still play a role in FDG uptake.

A molecular mechanism was also required to explain

differences in FDG uptake between M/D HCC and P/D HCC specimens.

However, it is important to note that the P/D HCC results were

derived from a small number of cases and showed considerable

variability in the results. Torizuka et al (17) reported that G6Pase activity was

lower in P/D HCC than in well-differentiated HCC or M/D HCC. Our

mRNA expression data were consistent with these results. In

addition, GLUT and HK mRNA levels were similar in P/D HCC and Meta

specimens. Of note, the G6Pase mRNA level of M/D HCC specimens was

218-fold greater than that of P/D HCC. Overexpression of G6Pase may

allow the FDG trapped in cells to be released into the bloodstream.

The SUV of HCC tumors may thus reflect how well HCC retains the

nature of normal liver tissue. High FDG accumulation in P/D HCC may

reflect increased GLUT1 expression and decreased G6Pase expression

compared with M/D HCC, which would explain why differentiated HCC

shows lower FDG accumulation compared with other malignancies.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that the

molecular mechanism for FDG-PET molecular imaging depends on GLUT1

and G6Pase expression. Low GLUT1 and high G6Pase expression

contribute to low FDG uptake in HCC tumors, preventing efficient

tumor detection. A pattern of high GLUT1 and low G6Pase expression

in P/D HCC facilitated FDG uptake similar to that of liver

metastasis from colorectal cancer. Finally, GLUT2 expression, while

important in normal hepatocytes, did not contribute to FDG uptake

in either type of liver cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the clinical staff

who cared for these patients. We also thank Dr Shoji Kimura for his

reliable experimental suggestions.

References

|

1

|

Fass L: Imaging and cancer. Mol Oncol.

2:115–152. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mawlawi O and Townsend DW: Multimodality

imaging: an update on PET/CT technology. Eur J Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 36(Suppl 1): 15–29. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schaefer O and Langer M: Detection of

recurrent rectal cancer with CT, MRI and PET/CT. Eur Radiol.

17:2044–2054. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sugiyama M, Sakahara H, Torizuka T, Kanno

T, Nakamura F, Futatsubashi M and Nakamura S: 18F-FDG PET in the

detection of extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma.

J Gastroenterol. 39:961–968. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Iwata Y, Shiomi S, Sasaki N, et al:

Clinical usefulness of positron emission tomography with

fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in the diagnosis of liver tumors.

Ann Nucl Med. 14:121–126. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Khan MA, Combs CS, Brunt EM, et al:

Positron emission tomography scanning in the evaluation of

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 32:792–797. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Trojan J, Schroeder O, Raedle J, et al:

Fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography for imaging of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 94:3314–3319. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nagaoka S, Itano S, Ishibashi M, et al:

Value of fusing PET plus CT images in hepatocellular carcinoma and

combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma patients with

extrahepatic metastases: preliminary findings. Liver Int.

26:781–788. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Akiyoshi T, Oya M, Fujimoto Y, et al:

Comparison of preoperative whole-body positron emission tomography

with MDCT in patients with primary colorectal cancer. Colorectal

Dis. 11:464–469. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al:

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and

outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer

Res. 13:427–433. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lee JD, Yun M, Lee JM, et al: Analysis of

gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinomas with regard

to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake pattern on positron emission

tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 31:1621–1630. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hatano E, Ikai I, Higashi T, et al:

Preoperative positron emission tomography with

fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose is predictive of prognosis in

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J

Surg. 30:1736–1741. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Byström P, Berglund A, Garske U, et al:

Early prediction of response to first-line chemotherapy by

sequential [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission

tomography in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol.

20:1057–1061. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chau I and Cunningham D: Treatment in

advanced colorectal cancer: what, when and how? Br J Cancer.

100:1704–1719. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

de Langen AJ, van den Boogaart V,

Lubberink M, et al: Monitoring response to antiangiogenic therapy

in non-small cell lung cancer using imaging markers derived from

PET and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Nucl Med. 52:48–55.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lee JH, Park JY, Kim do Y, et al:

Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET for hepatocellular carcinoma

patients treated with sorafenib. Liver Int. 31:1144–1149. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, et al: In

vivo assessment of glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma

with FDG-PET. J Nucl Med. 36:1811–1817. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Caracó C, Aloj L, Chen LY, Chou JY and

Eckelman WC: Cellular release of [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose as a

function of the glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme system. J Biol Chem.

275:18489–18494. 2000.

|

|

19

|

Kameyama R, Yamamoto Y, Izuishi K, Sano T

and Nishiyama Y: Correlation of 18F-FLT uptake with equilibrative

nucleoside transporter-1 and thymidine kinase-1 expressions in

gastrointestinal cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 32:460–465. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Izuishi K, Yamamoto Y, Sano T, et al:

Molecular mechanism underlying the detection of colorectal cancer

by 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose-positron emission tomography. J

Gastrointest Surg. 16:394–400. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Murakami K: FDG-PET for hepatobiliary and

pancreatic cancer: Advances and current limitations. World J Clin

Oncol. 2:229–236. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lin WY, Tsai SC and Hung GU: Value of

delayed 18F-FDG-PET imaging in the detection of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 26:315–321. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhao FQ and Keating AF: Functional

properties and genomics of glucose transporters. Curr Genomics.

8:113–128. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Paudyal B, Paudyal P, Oriuchi N, Tsushima

Y, Nakajima T and Endo K: Clinical implication of glucose transport

and metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 33:1047–1054. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Roh MS, Jeong JS, Kim YH, Kim MC and Hong

SH: Diagnostic utility of GLUT1 in the differential diagnosis of

liver carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology. 51:1315–1318.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wood IS and Trayhurn P: Glucose

transporters (GLUT and SGLT): expanded families of sugar transport

proteins. Br J Nutr. 89:3–9. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Brown GK: Glucose transporters: structure,

function and consequences of deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis.

23:237–246. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Leturque A, Brot-Laroche E, Le Gall M,

Stolarczyk E and Tobin V: The role of GLUT2 in dietary sugar

handling. J Physiol Biochem. 61:529–537. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ong LC, Jin Y, Song IC, Yu S, Zhang K and

Chow PK: 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in human tumor

cells is related to the expression of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II.

Acta Radiol. 49:1145–1153. 2008.

|

|

30

|

Paudyal B, Oriuchi N, Paudyal P, et al:

Clinicopathological presentation of varying 18F-FDG uptake and

expression of glucose transporter 1 and hexokinase II in cases of

hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma. Ann Nucl

Med. 22:83–86. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|