Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic

malignancy (1), and more than 90%

is classified as epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) (2). The majority of EOC patients are

diagnosed at advanced stages and the overall 5-year survival rate

is approximately 40% (3). It has

been reported that invasion and metastasis process remains the

leading cause of recurrence and death from EOC and the molecular

mechanisms of invasiveness and the metastatic property are not

clearly understood.

Accumulating evidence reveals that epithelial to

mesenchymal transition (EMT), a well-recognized process by which

cells from a differentiated epithelial state could convert into a

dedifferentiated migratory mesenchymal phenotype, which plays an

essential role in the regulation of embryogenesis, organ fibrosis,

wound healing and cancer metastasis (4). The crucial events of EMT include

decreasing the cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin; increasing

more plastic mesenchymal proteins such as vimentin, N-cadherin, and

deregulating the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway

(5). Emerging evidence indicates

that EMT is of vital importance in obtaining invasive and migratory

ability in EOC (6–8). A number of transcription factors

(TFs), such as Twist, Snail, Slug, and zinc finger E-box binding

homeobox 1 (ZEB1)/2, are considered as the major inducers of EMT

that repress E-cadherin directly or indirectly in EOC cells

(9–13). Thus, EOC patients may benefit from

targeted therapies that inhibit EMT.

Emodin (1, 3, 8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone;

EMO) is a natural anthraquinone derivative in the roots and

rhizomes of Polygonum cuspidatum and Rheum palmatum,

possessing various biological activities such as anti-inflammatory,

anti-bacterial, antioxidant and anticancer properties (14–17).

EMO displays anticancer activities in several types of cancers,

including EOC. In one study it was elucidated that EMO exerted

antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects in A2780

(paclitaxel-sensitive) and A2780/taxol (paclitaxel-resistant) cells

by reducing the expression of anti-apoptotic molecules, such as

survivin and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) (18), whereas, EMO had potential to inhibit

tumor invasion and metastasis of HO-8910PM cells via repression of

the production of MMP-9 (19).

Studies in vitro also demonstrated that EMO was effective on

restraining SKOV3 and HO8910 cell invasion (20). However, the molecular mechanisms of

the anti-invasive and antimetastatic functions are unknown. In

previous studies, EMO was shown to exert inhibitory effects on cell

invasion and migration of colorectal and cervical cancer, and head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), which is associated with

the inhibition of EMT and deregulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling

pathway (21–23). Therefore, we speculated that EMO may

inhibit the EOC cells to undergo the EMT progress by regulation of

WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, consequently weakening the

invasiveness and meta-static ability.

We investigated the effects of EMO on EOC cells

in vitro. In the present study, we demonstrated that EMO

could inhibit EOC cells invasion and migration by suppressing EMT,

demonstrated by increased epithelial markers E-cadherin and keratin

and decreased mesenchymal markers vimentin and N-cadherin. One of

the molecular mechanisms was that EMO was able to activate glycogen

synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), which may targets β-catenin and then

decreases its target gene ZEB1 expression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

A2780, OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 cells, and human EOC cell

lines were purchased from the Conservation Genetics Chinese Academy

of Sciences (CAS) Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). A2780 cells were

maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco by Life Technologies, Grand

Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 2.0 g/l NaHCO3 and

10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco by Life Technologies,

Australia). OVCAR-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

supplemented with 2.0 g/l NaHCO3 and 20% FBS. SK-OV-3

cells were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO,

USA) with 2.2 g/l NaHCO3 and 10% FBS. All cell culture

supplements contained 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml

streptomycin (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd.).

Cells were kept at 37°C with subconfluence in 95% air and 5%

CO2 in a humidified incubator. EMO and inhibitor

SB216763, dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) at 50

mM stock solution respectively, were purchased from Sigma. For EMO

or SB216763 treatment, stock solution was added into culture medium

at a final concentration of <0.1% DMSO (v/v). DMSO solution

alone was used as a control for all experiments.

Cell viability assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (BestBio,

Shanghai, China) was used to study the influence of EMO on cell

proliferation. Cells were seeded at a density of 2.5×103

cells/well in 100 µl medium into 96-well plates. After

treatment with 20 µM EMO for 48 h, 10 µl of CCK-8 was

added to each well, followed with incubation for 2 h at 37°C. Cell

viability was determined by the absorbance at 450 nm in each well

measured by a plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Each

experiment was performed in quintuplicate.

Transwell Matrigel invasion assays

Cell invasion assay with a Matrigel-coated membrane

(1:4 dilution in serum-free medium; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA,

USA) was performed using 24-well Transwell inserts with a pore

diameter of 8-µm (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). When

cells were seeded into 6-well plates until treatment with EMO for

48 h when reaching confluence of 70–80%, 3×104 cells

were re-suspended in 200 µl serum-free medium and then

seeded into the upper chamber. Medium (750 µl) containing

10% FBS was added into the lower chamber. After incubation for 24

h, the cells on the upper surface of the filter were removed by

wiping with a cotton swab. The invaded cells on the lower surface

of the filter were fixed in methanol solution for 5 min and 3.7%

formaldehyde solution for 5 min, and then stained with Giemsa

(Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). Images were

captured by an Olympus IX51 inverted microscope (Olympus Optical,

Melville, NY, USA) and five visual fields (magnification, ×100)

were counted.

Western blot analysis

The total cellular proteins were extracted by adding

appropriate RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1%

Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and sodium

orthovanadate, sodium fluoride, EDTA, leupeptin] complemented a

protease inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (all from

Beyotime Biotechnology) for western blot analysis. After

centrifugation with 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min, the supernatants

were collected, then protein concentration was determined using BCA

protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and

whole lysates were mixed with 5X SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer

(both from Beyotime Biotechnology) at a ratio of 1:4. Samples were

heated at 95°C in metal bath for 5 min and were separated on

SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The separated proteins were then

transferred to a pure nitrocellulose blotting membrane (Pall Life

Sciences, Mexico). The membrane blots were probed with the

appropriate primary antibody at 4°C overnight and then incubation

with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibody. Signals

from the bound antibodies were detected with enhanced

chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA). The results were quantified by densitometry, using ImageJ

software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Primary antibodies against

matrix metallopro-teinase-9 (MMP-9), matrix metalloproteinase-2

(MMP-2), E-cadherin, keratin, N-cadherin, vimentin, ZEB1, GSK-3β,

β-catenin and glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Primary antibodies against phospho-Ser9-GSK-3β

(p-GSK-3βSer9) was purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), goat

anti-mouse IgG and rabbit anti-goat IgG were all obtained from

Zhongshan Jinqiao Biological Technology (Beijing, China).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

experiments

The sequence for ZEB1 specific siRNA (Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd., China) was: 5′-UGAUCAGCCUCAAUCUGCAAAUGCA-3′

and non-targeting scrambled siRNA was the negative control. Cells

were transfected with 50 nM of siRNA using NanoFectin transfection

reagent (Excell Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The transfection cocktail mixing 5

µl of NanoFectin transfection reagent and 245 µl

Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand) with 5 µl

siRNA and 245 µl Opti-MEM medium were incubated for 20 min

at room temperature. Then, the above mixtures were added to the

6-well plates with cells that had been seeded overnight to reach

50–60% confluence prior to transfection process. Transfection was

performed for 6 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator and the

old medium was changed with fresh complete medium for a further 12

h followed by EMO 20 µM treatment for 48 h. Then the cells

were harvested for Transwell assay and western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by

two-tailed Student's t-test using GraphPad Prism version 6.02

(GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and P<0.05 were

considered as significant. The data are shown as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD) from three independent assays.

Results

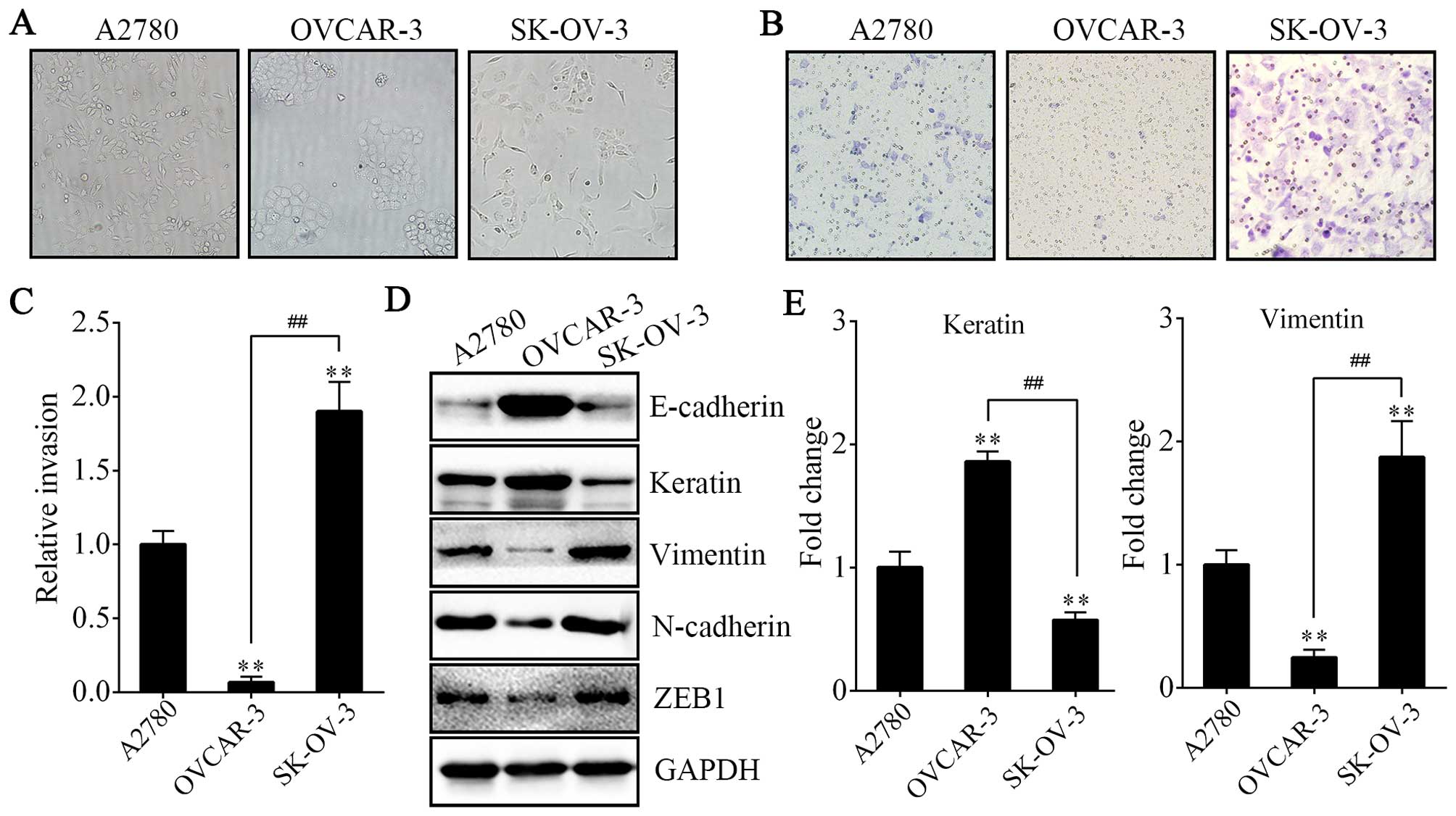

A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells exhibit a

spindle-like mesenchymal phenotype with more invasive ability than

OVCAR-3 cells

Before conducting the following experiment, we chose

cells with more invasive potential and having undergone EMT. First,

we compared the morphological characteristics of the human EOC cell

lines A2780, OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3. We found that the SK-OV-3 cells

displayed elongated fibroblastoid morphology while the OVCAR-3

cells showed a rounded shape, typical of an epithelial

cobblestone-like appearance, growing in clusters. Morphology

feature of A2780 cells was between epithelial round-shaped and

spindle-shaped mesenchymal form (Fig.

1A). The results above were in accordance with their relative

invasive properties and the expression of markers of epithelial and

mesenchymal phenotype (Fig. 1B–E).

The weakest invasive activity and highest expression of E-cadherin

and keratin (epithelial markers) were shown in OVCAR-3 cells;

however, vimentin, N-cadherin and ZEB1 (mesenchymal markers) were

rarely expressed. In contrast, the A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells

exhibited more invasive ability and expressed significantly lower

levels of E-cadherin and keratin and higher levels of vimentin,

N-cadherin and ZEB1. Thus, we used A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells to

undergo EMO treatment.

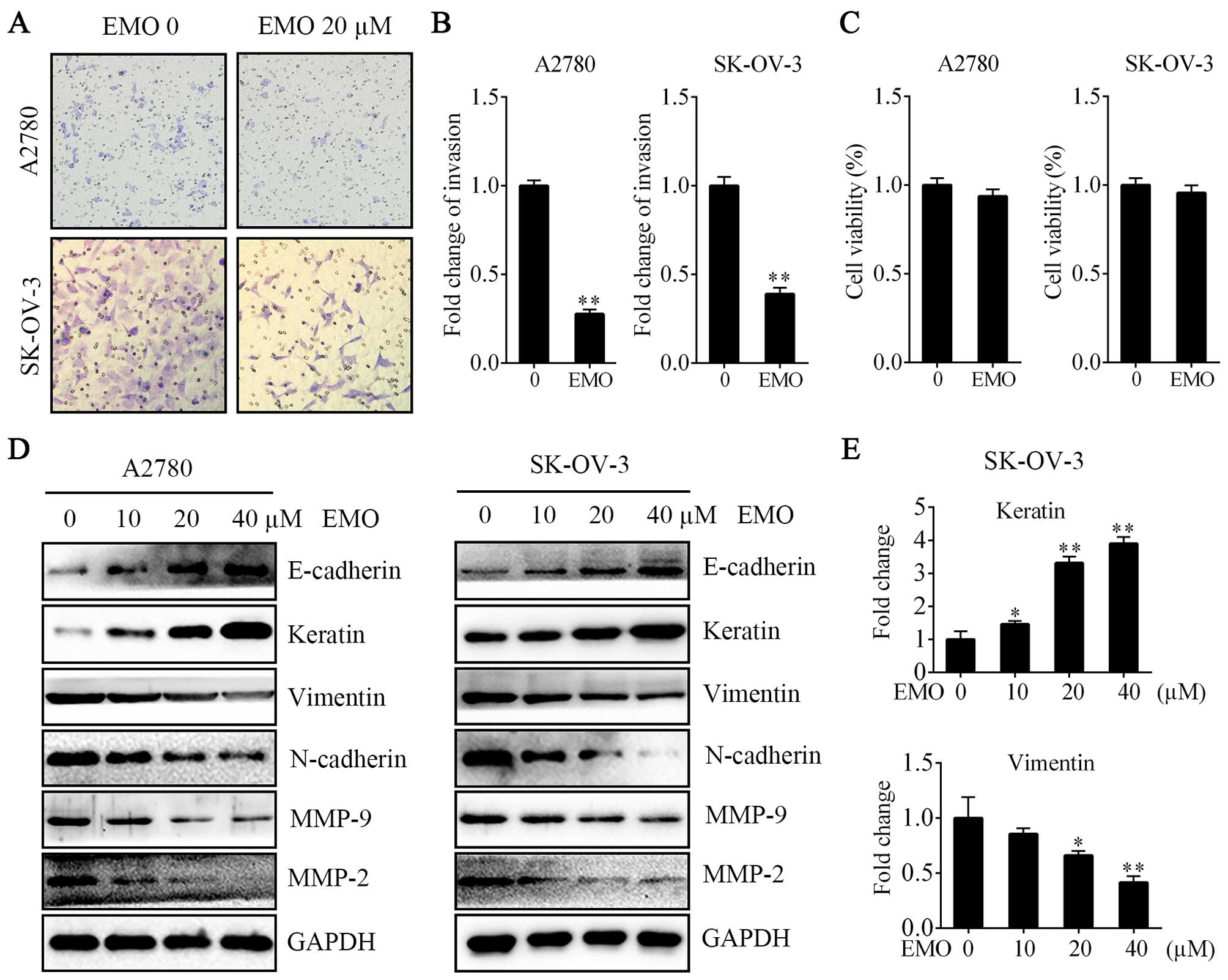

EMO suppresses the invasion property of

A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells by inhibiting EMT

To confirm that EMO inhibited the invasion of

ovarian cancer cells as previously reported, we performed Transwell

Matrigel invasion assays. We found that the invasion activities

were significantly decreased compared with the normal control group

in both A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells (Fig.

2A and B). Moreover, EMO 20 µM failed to regulate cell

proliferation ability (Fig. 2C). We

further studied whether EMO could change the EMT phenotype. After

the treatment of cells with various concentrations of EMO for 48 h,

upregulation of E-cadherin and keratin and downregulation of

vimentin, N-cadherin, MMP-9 and MMP-2 in a concentration-dependent

manner were observed (Fig. 2D and

E).

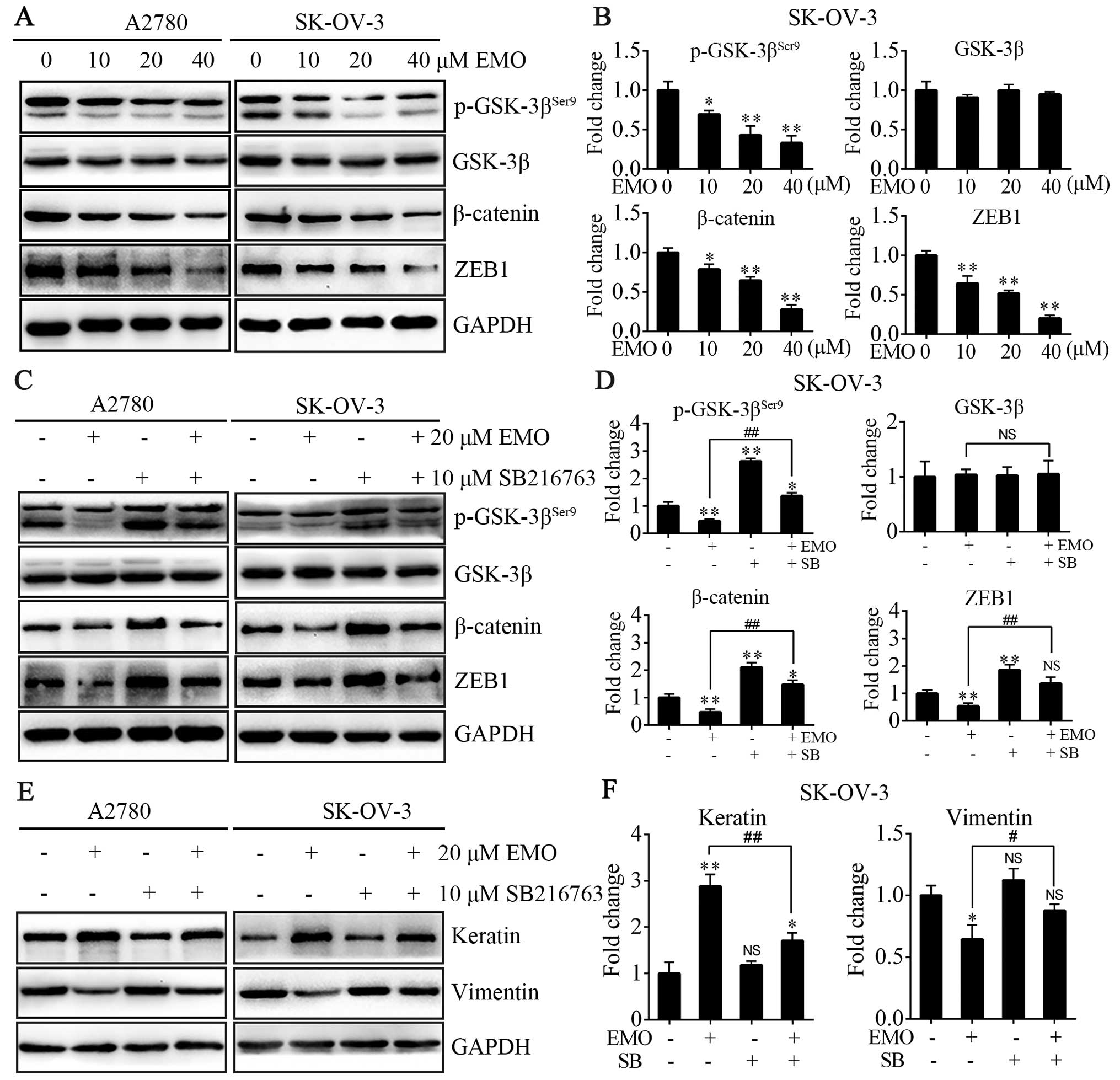

EMO inhibits WNT/β-catenin signaling

pathway and the expression of ZEB1 via GSK-3β activation

To investigate the functional mechanism of EMO

inhibition of EMT on A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells, we tested

WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and transcription factor ZEB1, both

closely connected with EMT. The cells were treated with EMO

concentrations ranging from 0 to 40 µM for 48 h. The data

showed that EMO treatment dose-dependently increased levels of

p-GSK-3βSer9, one of negative regulatory sites, led to

the increase of GSK-3β kinase activity accordingly, occurred in the

absence of any changes in total GSK-3β levels and decreased total

β-catenin protein levels (Fig. 3A and

B). EMO treatment also significantly decreased ZEB1 protein

levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3A and B). To further clarify that EMO

regulated the GSK-3β/β-catenin/ZEB1 pathways, cells were pretreated

with SB216763, a selective GSK-3β kinase inhibitor, and we found

that the effects of EMO were blocked (Fig. 3C and D). SB216763 treatment restored

EMO-induced decrease of p-GSK-3βSer9, β-catenin and ZEB1

protein expression. Furthermore, EMO treatment did not decrease

mesenchymal phenotype such as vimentin and slightly increased

epithelial phenotype such as keratin protein levels in the presence

of SB216763 compared to its absence (Fig. 3E and F).

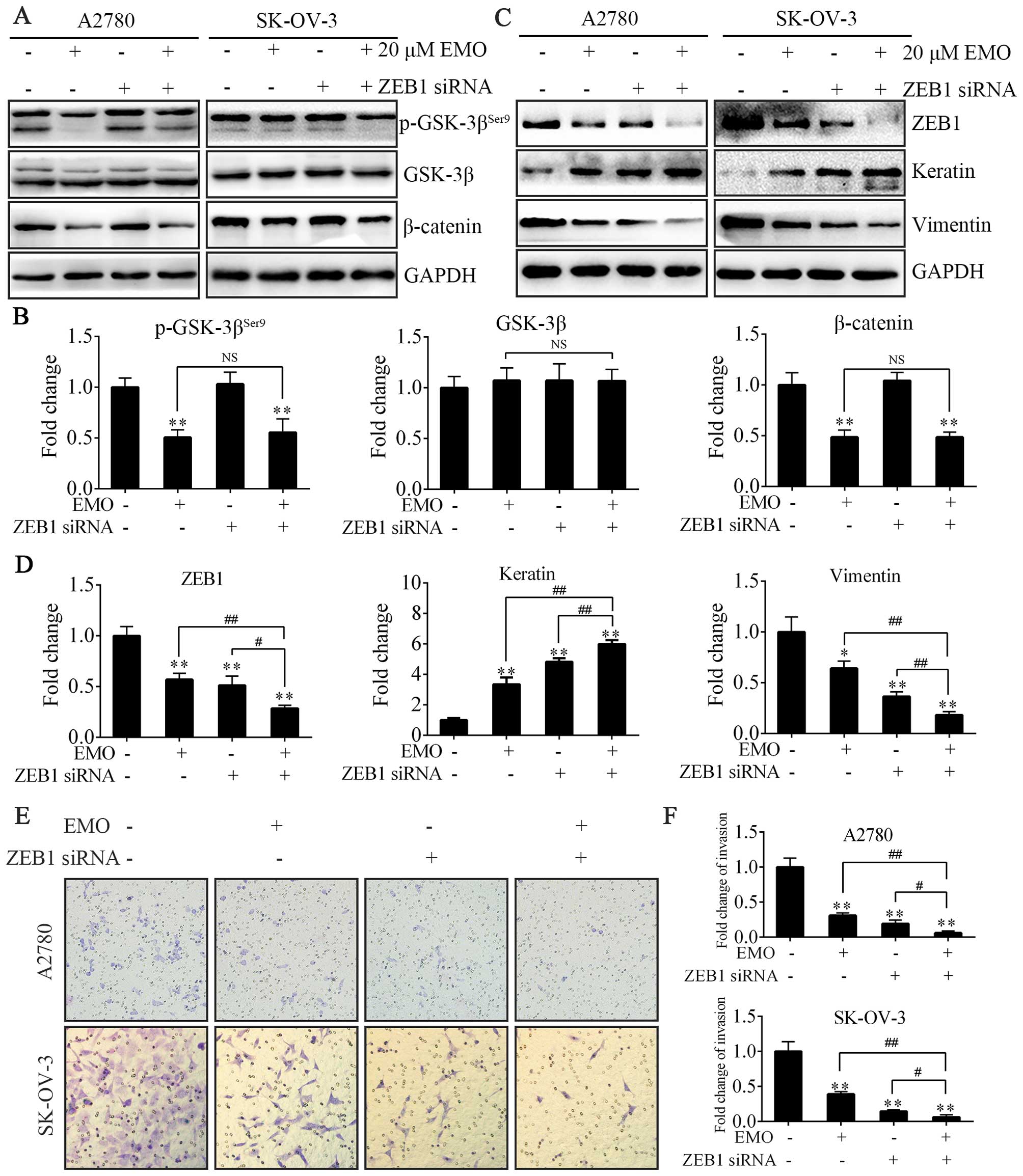

EMO represses EMT via ZEB1

inhibition

To further study the mechanism of inhibition of EMT,

ZEB1 siRNA was designed to evaluate the relationship between

WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and ZEB1. Either EMO treatment

alone or treatment of ZEB1-knockdown cells with EMO almost equally

played the same role in regulating the activity of GSK-3β and the

expression of β-catenin (Fig. 4A and

B). Actually, ZEB1 siRNA failed to participate in the above

process. Furthermore, we investigated the effects of EMO on cell

invasion followed by ZEB1 knockdown. Upon ZEB1 knockdown, A2780 and

SK-OV-3 cells treated with EMO exhibited more decreased invasion

capacity (Fig. 4E and F), decreased

vimentin protein levels and consistently more increased keratin

expression levels (Fig. 4C and D)

compared to ZEB1 knockdown or EMO treatment alone. Accordingly,

ZEB1 protein levels were lowest in the EMO-treated ZEB1 knockdown

cells (Fig. 4C and D).

Discussion

We have validated that A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells

displayed a spindle-like mesenchymal phenotype with higher invasive

property than OVCAR-3 cells. Then, we showed for the first time

that the inhibition of invasion and EMT by treating A2780 and

SK-OV-3 cells with different concentrations of EMO. No previous

studies had found the influence of EMO on

GSK-3β/β-catenin-regulated EMT markers, including ZEB1 in EOC.

Therefore, the present study provides the first report to explore

the role of GSK-3β/β-catenin/ZEB1 pathways in repressing EMT by

EMO.

We confirmed that A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells had

obviously lower protein levels of E-cadherin and keratin and higher

protein levels of vimentin, N-cadherin and transcription factor

ZEB1. We also showed that A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells had elongated

fibroblastoid mesenchymal phenotype with more invasive ability than

OVCAR-3 cells, which displayed epithelial cobblestone-like

morphology in line with earlier reports (24).

In agreement with previous studies showing that

exposure to EMO could inhibit EOC cells invasion and metastasis

(19,20), we further demonstrated the molecular

mechanism in the present study. We showed that EMO could target the

EMT process in A2780 and SK-OV-3 cells, as manifested by decreased

invasive capacities and alterations in the expression of

EMT-related markers, including upregulation of the expression of

E-cadherin and keratin, and downregulation of the expression of

vimentin, N-cadherin, MMP-9 and MMP-2. These results demonstrated

that EMO alters correlation of the gene products with EMT induction

or maintenance by repression of the mesenchymal phenotype of EOC

cells.

Previous reviews summarized that the combined action

of various signaling pathways, including WNT/β-catenin signaling

pathway, make a greater contribution to the initiation and

morphogenic process of the EMT (25). In particular, WNTs and their

downstream effectors could regulate the important processes for

tumor initiation, tumor growth, cell senescence and apoptosis,

differentiation and metastasis (26). Besides, WNT signaling pathway is

activated in EOC. One way of the upregulated signaling transduction

is directly through activating ligand, another is by a

ligand-independent increase in nuclear β-catenin via crosstalk with

other pathways. In addition, WNT signaling pathway was investigated

as a potential target in the development of new drugs for ovarian

cancer (27). Previous studies

showed that EMO possessed the capability of inhibiting the WNT

signaling pathway by downregulating T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphocyte

enhancer factor (LEF) transcriptional activity and inducing

morphological changes indicating MET accompanied by the increase in

E-cadherin expression in human colorectal cancer cells (SW480 and

SW620) (21). Besides, EMO

inhibited cell population and migration in cervical cancer cells

(SiHa and HeLa cells) and downregulated the WNT/β-catenin signaling

pathway activated by TGF-β through inhibiting β-catenin in HeLa

cells (22). Furthermore, in head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), EMO inhibited

Twist1-induced invasion and EMT by inhibiting the β-catenin and Akt

pathways in vitro and in vivo (23). In the present study, we demonstrated

for the first time that EMO had anti-invasive effect in A2780 and

SK-OV-3 cells, evidenced by the repression of EMT in vitro

and these effects were mediated by decreased phosphorylation of

GSK-3β on Ser9 site and total β-catenin levels and inhibition of

subsequent ZEB1 expression.

It is well known that reduction of the expression of

p-GSK-3βSer9 led to the increase of GSK-3β kinase

activity, followed by phosphorylation of β-catenin, a

multifunctional protein in WNT-mediated signal transduction,

leading to ubiquitylation or proteasomal degradation. Accordingly,

the non-phosphoform of β-catenin binds to TCF bind elements

(TBE)-specific DNA sequences that interact with TCF/LEF TFs after

it translocates into the nucleus, leading to the transcription of

WNT-responsive genes (28).

Moreover, ZEB1 is a direct target of β-catenin/TCF4 and acts also

as an effector of this signaling pathway in regulating genes

associated with tumor invasiveness in intestinal primary tumors and

colorectal cancer cell lines with mutant APC (29). In addition, PI3K/Akt targeting

GSK3β/β-catenin pathway could dynamically control the ZEB1 gene

transcription in bladder cancer cells (T24-L, lung metastasis)

(30). In our study, western blot

analysis showed that EMO decreased the expression of

p-GSK-3βSer9, total β-catenin and ZEB1, and these

effects were rescued by the selective GSK-3β inhibitor, SB216763.

Besides, cells treated with SB216763 alone expressed elevated

β-catenin and ZEB1 protein. These results suggest that EMO inhibits

EMT in EOC cells via activating GSK-3β followed by targeting

β-catenin and regulating its downstream target ZEB1.

Studies have demonstrated that a number of TFs were

shown to be key regulators of E-cadherin expression, including

Twist, Snail, Slug, ZEB1 and ZEB2 (31–34).

Among them, the ZEB1, encoded by the TCF8 gene, contributes to

malignant progression of various epithelial tumors. ZEB1 plays

crucial effects on induction of EMT by inhibiting expression of

E-cadherin and microRNAs, which induce an epithelial phenotype

(35). The downregulation of the

ZEB1 was found to be associated with the decreased colony-forming

ability and the cell migration ability in the human ovarian cancer

SK-OV-3 and HO8910 cells in vitro and also with the

attenuated tumorigenesis of the shZEB1-SKOV3 cells in nude mice by

blocking the EMT process (36). So

ZEB1 may be a potential therapeutic target in future clinical

trials for preventing and treating EOC metastases. In the present

study, concomitant knockdown of ZEB1 expression and EMO treatment

synergistically suppressed cell invasion and EMT at greater levels.

These results indicate that ZEB1 is a key regulator of cell

invasion and EMT in EMO-treated EOC cells. Besides, ZEB1 knockdown

alone did not affect GSK-3β activity and β-catenin levels.

Similarly, EMO treatment alone or treatment of ZEB1-knockdown cells

with EMO almost equally decreased p-GSK-3βSer9 and

β-catenin levels. The results suggest that ZEB1 is downstream of

β-catenin.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the

anti-invasive efficacy of EMO on EOC cells was associated with

inhibition of EMT. The mechanism may be that GSK-3β activation by

EMO treatment decreased expression of total β-catenin, leading to

repressed WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and sequentially the

decreased ZEB1 levels. Based on our findings, we provide additional

scientific evidence for the use of EMO in the treatment of EOC.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

Science and Technology Development Project of Shandong Province

(2008GG2NS02017) as well as National Natural Science Foundation of

China (NSFC) (81302268).

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 65:5–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Piek JM, van Diest PJ and Verheijen RH:

Ovarian carcinogenesis: An alternative hypothesis. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 622:79–87. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Banerjee S and Kaye SB: New strategies in

the treatment of ovarian cancer: Current clinical perspectives and

future potential. Clin Cancer Res. 19:961–968. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nieto MA: Epithelial plasticity: A common

theme in embryonic and cancer cells. Science. 342:12348502013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ghahhari NM and Babashah S: Interplay

between microRNAs and WNT/β-catenin signalling pathway regulates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Eur J Cancer.

51:1638–1649. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Vergara D, Merlot B, Lucot JP, Collinet P,

Vinatier D, Fournier I and Salzet M: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 291:59–66. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rosanò L, Spinella F, Di Castro V, Nicotra

MR, Dedhar S, de Herreros AG, Natali PG and Bagnato A: Endothelin-1

promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human ovarian

cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65:11649–11657. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Elloul S, Vaksman O, Stavnes HT, Trope CG,

Davidson B and Reich R: Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition

determinants as characteristics of ovarian carcinoma effusions.

Clin Exp Metastasis. 27:161–172. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nuti SV, Mor G, Li P and Yin G: TWIST and

ovarian cancer stem cells: Implications for chemoresistance and

metastasis. Oncotarget. 5:7260–7271. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yin G, Alvero AB, Craveiro V, Holmberg JC,

Fu HH, Montagna MK, Yang Y, Chefetz-Menaker I, Nuti S, Rossi M, et

al: Constitutive proteasomal degradation of TWIST-1 in

epithelial-ovarian cancer stem cells impacts differentiation and

metastatic potential. Oncogene. 32:39–49. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

11

|

Kurrey NK, Amit K and Bapat SA: Snail and

Slug are major determinants of ovarian cancer invasiveness at the

transcription level. Gynecol Oncol. 97:155–165. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Prislei S, Martinelli E, Zannoni GF,

Petrillo M, Filippetti F, Mariani M, Mozzetti S, Raspaglio G,

Scambia G and Ferlini C: Role and prognostic significance of the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition factor ZEB2 in ovarian cancer.

Oncotarget. 6:18966–18979. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E and Peter ME:

The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer

cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes

Dev. 22:894–907. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tian K, Zhang H, Chen X and Hu Z:

Determination of five anthraquinones in medicinal plants by

capillary zone electrophoresis with beta-cyclodextrin addition. J

Chromatogr A. 1123:134–137. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Srinivas G, Babykutty S, Sathiadevan PP

and Srinivas P: Molecular mechanism of emodin action: Transition

from laxative ingredient to an antitumor agent. Med Res Rev.

27:591–608. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Shrimali D, Shanmugam MK, Kumar AP, Zhang

J, Tan BK, Ahn KS and Sethi G: Targeted abrogation of diverse

signal transduction cascades by emodin for the treatment of

inflammatory disorders and cancer. Cancer Lett. 341:139–149. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hei ZQ, Huang HQ, Tan HM, Liu PQ, Zhao LZ,

Chen SR, Huang WG, Chen FY and Guo FF: Emodin inhibits dietary

induced atherosclerosis by antioxidation and regulation of the

sphingomyelin pathway in rabbits. Chin Med J. 119:868–870.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li J, Liu P, Mao H, Wanga A and Zhang X:

Emodin sensitizes paclitaxel-resistant human ovarian cancer cells

to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in vitro. Oncol Rep. 21:1605–1610.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhu F, Liu XG and Liang NC: Effect of

emodin and apigenin on invasion of human ovarian carcinoma

HO-8910PM cells in vitro. Ai Zheng. 22:358–362. 2003.In Chinese.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xue H, Chen Y, Cai X, Zhao L, He A, Guo K

and Zheng X: The combined effect of survivin-targeted shRNA and

emodin on the proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells.

Anticancer Drugs. 24:937–944. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pooja T and Karunagaran D: Emodin

suppresses Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells SW480 and

SW620. Eur J Pharmacol. 742:55–64. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Thacker PC and Karunagaran D: Curcumin and

emodin down-regulate TGF-β signaling pathway in human cervical

cancer cells. PLoS One. 10:e01200452015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Way TD, Huang JT, Chou CH, Huang CH, Yang

MH and Ho CT: Emodin represses TWIST1-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma cells by inhibiting the β-catenin and Akt pathways. Eur J

Cancer. 50:366–378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Davidowitz RA, Selfors LM, Iwanicki MP,

Elias KM, Karst A, Piao H, Ince TA, Drage MG, Dering J, Konecny GE,

et al: Mesenchymal gene program-expressing ovarian cancer spheroids

exhibit enhanced mesothelial clearance. J Clin Invest.

124:2611–2625. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Thiery JP and Sleeman JP: Complex networks

orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 7:131–142. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Anastas JN and Moon RT: WNT signalling

pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

13:11–26. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Arend RC, Londoño-Joshi AI, Straughn JM Jr

and Buchsbaum DJ: The Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ovarian cancer: A

review. Gynecol Oncol. 131:772–779. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Rao TP and Kühl M: An updated overview on

Wnt signaling pathways: A prelude for more. Circ Res.

106:1798–1806. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sánchez-Tilló E, de Barrios O, Siles L,

Cuatrecasas M, Castells A and Postigo A: β-catenin/TCF4 complex

induces the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-activator

ZEB1 to regulate tumor invasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:19204–19209. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wu K, Fan J, Zhang L, Ning Z, Zeng J, Zhou

J, Li L, Chen Y, Zhang T, Wang X, et al: PI3K/Akt to

GSK3β/β-catenin signaling cascade coordinates cell colonization for

bladder cancer bone metastasis through regulating ZEB1

transcription. Cell Signal. 24:2273–2282. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Moreno-Bueno G, Portillo F and Cano A:

Transcriptional regulation of cell polarity in EMT and cancer.

Oncogene. 27:6958–6969. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

De Craene B and Berx G: Regulatory

networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat

Rev Cancer. 13:97–110. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Khan MA, Chen HC, Zhang D and Fu J: Twist:

A molecular target in cancer therapeutics. Tumour Biol.

34:2497–2506. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Peinado H, Olmeda D and Cano A: Snail, Zeb

and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the

epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 7:415–428. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S and Brabletz T:

E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of

cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28:151–166. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen D, Wang J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Yang C,

Cao W, Zhang H, Liu Y and Dou J: Effect of down-regulated

transcriptional repressor ZEB1 on the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition of ovarian cancer cells. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

23:1357–1366. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|