An adenovirus is a non-enveloped double-stranded DNA

virus with a symmetrical icosahedral structure (9). The genome is ~36 kb in length and can

encode >40 gene products (10).

These gene products are divided into three subtypes based on their

transcription start time, including early, middle and late stages

(11). Early gene products are

predominantly responsible for coding gene regulation, including the

E region, while late gene products are predominantly responsible

for coding structural proteins, including the L region (12,13). Among

adenovirus subtypes, adenovirus serotype 3 (Ad.3) and adenovirus

serotype 5 (Ad.5) are the most commonly studied subtypes, and Ad.5

is the most commonly used subtype (14). Following infection, the oncolytic

adenovirus initially recognizes specific receptors on the surface

of tumor cells and triggers their internalization (15). Subsequently, it enters tumor cells,

viral genomes migrate to the nucleus through microtubules, and

early viral proteins in the E1 region immediately begin to be

transcribed (16). The protein binds

to Rb to release the transcription factor, E2F, which also

activates the cell cycle, allowing oncolytic adenovirus-infected

cells to enter the S phase (6,17).

Concurrently, the E1A protein maintains p53 stability and inhibits

tumor growth by relying on the p53 pathway (18). The release of E2F also triggers the

coordinated activation of viral genes, which results in the

production of new virions, the lysis of infected cells and the

spread of viral offspring (19). The

oncolytic adenovirus continuously replicates in tumor cells,

eventually lysing tumor cells and infecting other tumor cells via

the same mechanism of action (20–23). Due

to the large loading capacity of the oncolytic adenovirus vector,

therapeutic genes are commonly inserted into the adenovirus vector

(24,25). Due to the continuous replication and

accumulation of adenoviruses in tumor cells, therapeutic genes are

expressed and thus spread, playing a synergistic antitumor role

(26).

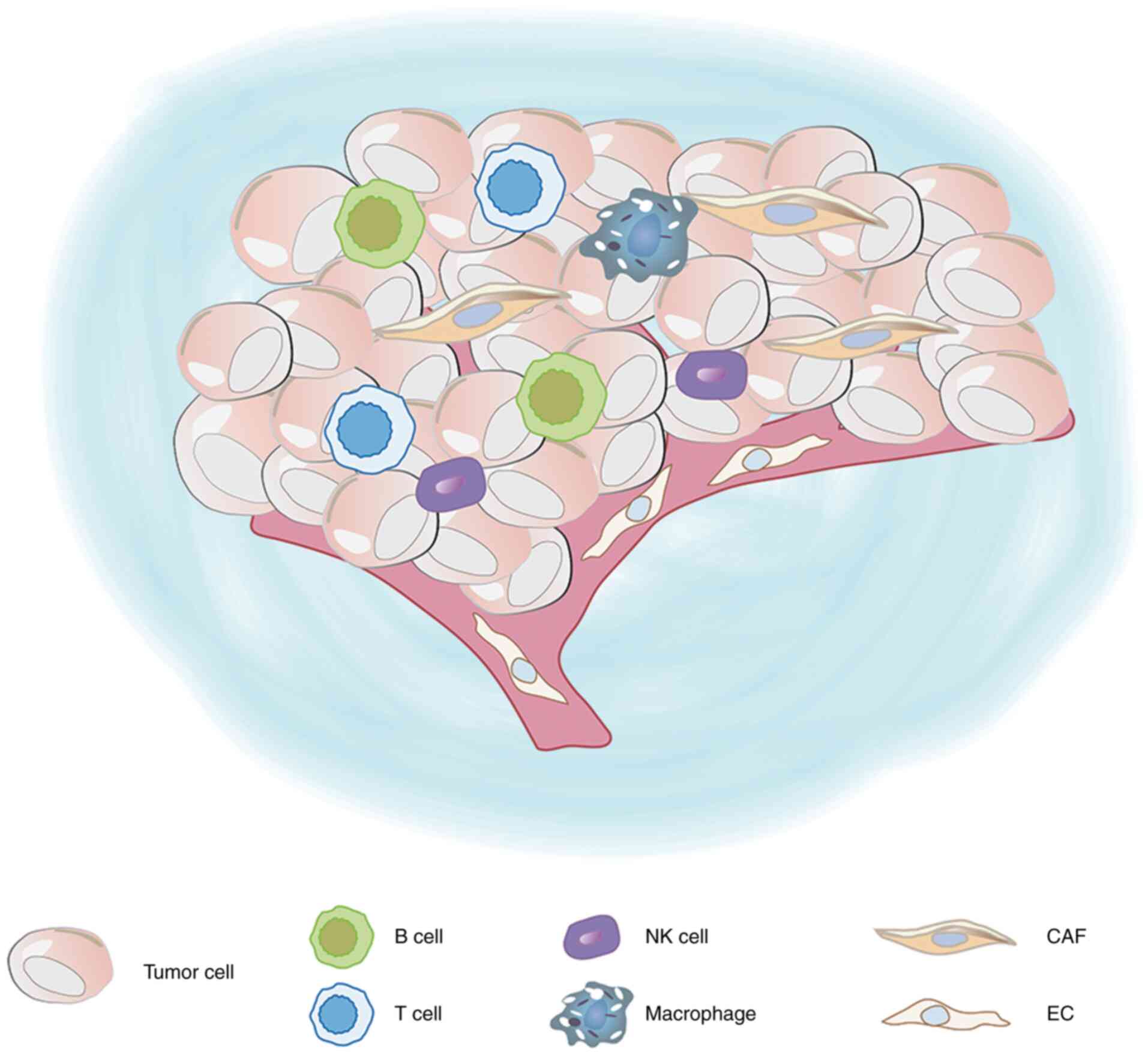

The TME is the internal environment for the growth

of tumors, which includes tumor cells (27,28),

stromal cells (tumor-associated vascular endothelial cells and

tumor-associated fibroblasts), immune cells [T lymphocytes and B

lymphocytes, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), dendritic cells

(DCs) and natural killer (NK) cells], the extracellular matrix

(ECM) and signaling molecules such as IL-4 and IL-10 (29–31). The

ECM includes various proteins, glycoproteins, proteoglycans and

other biochemical substances, which regulate vascular endothelial

cells and fibroblasts, and promote tumor growth and cell migration

(32) (Fig.

1). In the TME, tumor blood vessels are constantly supplying

oxygen and nutrients to support tumor growth (28,32–34). When

the tumor is exposed to hypoxic conditions locally, tumor blood

vessels receive signal stimulation and generate branches from

existing blood vessels (35,36). However, the structure of these tumor

vessels differs from that of normal vessels, with absence of

basement membranes, uneven diameter and size of the tubes, and

short circuit of arteries and veins, resulting in tumor

interstitial hypertension (37,38). Under

hypoxic conditions, tumor cells undergo glycolysis and produce more

lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the TME (39). Proton transport channels exist in all

parts of tumor tissues, which transfer the metabolized

H+ out of tumor tissues and maintain the pH in the TME

(40–42). However, pH reduction in normal tissues

results in necrosis, which is more conducive to tumor metastasis

and growth (43). Among the myeloid

progenitors cells located in the TME, myeloid-derived suppressor

cells (MDSCs), mast cells and most TAMs play key roles in promoting

tumor development (44). MDSCs are

immunosuppressive precursors of DCs, macrophages and granulocytes

(35,45). MDSCs maintain a normal tissue dynamic

balance in response to a variety of systemic infections and

injuries (33). Several animal models

have demonstrated that MDSCs can promote tumor angiogenesis and

disrupt the main mechanisms of immune surveillance by interfering

with antigen presentation, T-cell activation and NK cell killing of

DCs (46,47). It has also been reported that mast

cells are recruited into the tumor, where they release factors that

promote endothelial cell proliferation to promote tumor

angiogenesis (48–50). Increasing evidence suggests that

microenvironment-mediated external stimulation plays a key role in

tumor cell survival and drug resistance (28,51). The

complexity of the TME makes it difficult for the traditional

oncolytic virus to reverse the conditions set by the TME while

targeting tumor cells (27,52). The traditional oncolytic virus can

only inhibit the growth of tumor cells to a certain extent.

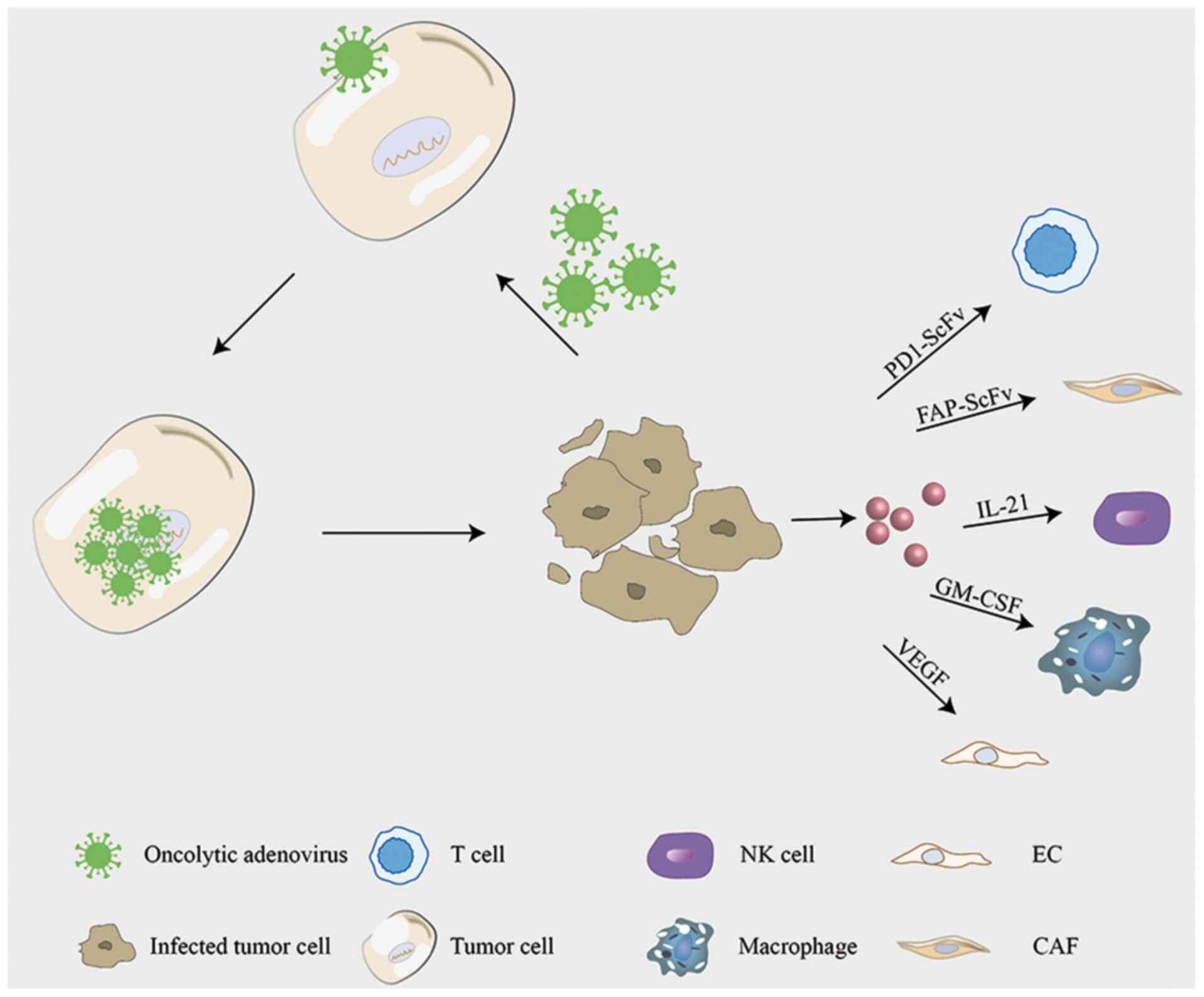

Owing to the constant improvement of genetic

engineering techniques, it is getting easier to develop oncolytic

adenovirus constructs with required properties. Preclinical trials

involve wild-type and recombinant oncolytic adenovirus (Table I), aimed to reverse the TME while

suppressing tumor cells (6,53) (Fig. 2).

Several oncolytic adenoviruses are currently undergoing clinical

trials as antitumor agents, and notably some progress has been made

in reversing the TME (Table II). An

ongoing clinical trial is testing RGD (Delta-24-rgd), a genetically

modified oncolytic adenovirus, as an agent against glioma. The

first results obtained in the phase I trials indicate that 20% of

patients showed durable responses and CD8+ T cells

infiltrated the tumor in large quantities (54). TILT-123 in preclinical studies altered

the cytokine balance in the TME towards Th1 and resulted in a

significant increase of the survival rate in severe combined

immunodeficiency (SCID) mice with human tumors (55,56). The

currently ongoing phase I trial is recruiting patients with solid

tumors to evaluate the safety.

DCs are derived from the bone marrow and play a key

role in inducing and maintaining antitumor immunity (57,58).

Infiltration of mature DCs into the tumor can enhance immune

activation and increase the recruitment of antitumor immune

effector cells and pathways (58,59).

However, in the TME, the antigen-presenting function of DCs may be

lost or inefficient (60). Tumor

cells can inhibit the function of DCs or change the TME by

recruiting immunosuppressive DCs (61). CD40 is a member of the tumor necrosis

factor receptor family and is expressed in DCs, which is a target

for infiltrating T cells (62). CD40L

is instantaneously expressed in T cells, which activates the

maturation of DCs and triggers the immune response. Adenovirus

delivery of CD40L induces DC activation, thereby inducing a Th1

immune response (63). The oncolytic

virus restricts CD40L expression in cancer cells, thus decreasing

systemic exposure and weakening the systemic immune response

(64,65). Currently, there are already two phase

I/II clinical trials involving LOAd703 that are recruiting

patients. One of the studies is recruiting patients with pancreatic

cancer to evaluate whether it supports the current treatment

standards for pancreatic cancer and whether it can improve the

survival rate of patients. Another study recruited patients with

malignant melanoma and monitored their tumor response, immune

response, virus shedding and survival rate. One of the major

virulence factors of bacteria was Helicobacter pylori

neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP), which is a TLR-2 agonist

capable of chemotaxis of neutrophils, and monocytes and stimulates

them to produce reactive oxygen species (66,67).

HP-NAP also induced Th1-polarized immune responses by stimulating

the secretion of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 and other

pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α

and IL-8 (68).

Ag-presenting-HP-NAP-activated DCs effectively amplified Ag

specific T cells, an important characteristic of mature DCs

(69). HP-NAP-activated DCs resulted

in Th1 cytokine secretion, with high IL-12 expression, relatively

low IL-10 secretion and migrated to CCL19 (69).

TAMs are divided into specific M1-like macrophage

subsets and specific M2-like macrophage subsets, and M1-like

macrophage subsets are activated by the classical pathway and exert

notable antitumor effects (70,71). In

the TME, specific M2-like macrophage subsets are the most common,

and their cytokines IL-6, TNF, IL-1 and IL-23 promote tumor growth

and metastasis and silence T-cell function (72,73).

Selective removal of specific M2-like macrophage subsets has become

a research hotspot. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating

factor (GM-CSF) can affect macrophages, promote their rapid

differentiation to mature macrophages, prolong the life of mature

macrophages, and enhance their cellular immune function (74). By inserting GM-CSF into the Ad5

vector, ONCS-102 induced notable antitumor immunity (75). ONCOS-102 is currently being assessed

in two phase I clinical trials in advanced peritoneal malignancies

and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ad-CD-GMCSF is an adenovirus

carrying cytomegalovirus promoter cytosine deaminase (CD) and

GM-CSF (75). Adenovirus vectors

expressing CD and GM-CSF are well tolerated in refractory tumors

(5). CD47 is a cell surface

transmembrane protein present in normal tissues (76). It is highly expressed in malignant

tumor cells and binds to signaling regulatory protein-α (SIRPα)

expressed on macrophages to inhibit macrophage phagocytosis,

resulting in immune escape. SIRPα-FC fusion protein inserted into

the oncolytic adenovirus vector blocks the binding of CD47 to

macrophages, leading to a large increase in macrophage infiltration

in tumor tissues, thus enhancing the antitumor effect (77). MMAD-IL13 loaded with IL13 demonstrated

enhanced antitumor effects by inducing apoptosis in the TME in

vivo, and decreased the percentage of specific M2-like

macrophages (78). Scott et al

(79) constructed a set of bivalent

and trivalent T-cell adapters (BiTEs/TriTEs), which can

specifically recognize CD3ε on T cells and the folate receptor or

CD206 on specific M2-like macrophages. T-cell adapters were used to

specifically direct the cytotoxicity of endogenous T cells to

M2-like macrophages and deplete M2-like macrophages in tumor

tissues. There was a significant increase in specific M1-like

macrophage fraction among surviving macrophages, indicating a

reversal of macrophage type in the TME (79).

NK cells have a notable antitumor effect in the

initial stages of tumors, which can eliminate tumor cells (30). However, at the advanced tumor stage,

NK cells gradually lose their antitumor ability and become

dysfunctional (80). IL-21 is

involved in NK cell differentiation (81), and the oncolytic adenovirus equipped

with IL-21 exerts an obvious inhibitory effect on the proliferation

of tumor cells (82). Similarly, NK

cells can be activated by IL-15 (83), and oncolytic adenovirus (Ad-E2F/IL15),

which expresses IL-15, can lyse tumor cells and coordinate with

immune cells to enhance the antitumor response (84).

CAFs are a major component of the tumor stroma,

which regulate the TME and influence the behavior of tumor cells,

and play crucial roles in the occurrence, development, invasion and

metastasis of tumors (85,86). Fibroblasts in the TME secrete growth

factors such as hepatocyte growth factor, fibroblast growth factor

and CXCL12 (87), which promote the

growth and survival of malignant cells, and act as chemokines to

induce the migration of other cells into the TME (88,89).

Concurrently, CAFs form a barrier in tumors and prevent the

effective penetration and transmission of oncolytic virus, thus

limiting its efficacy (90,91). By modifying oncolytic adenovirus, the

effects of tumor cells and CAFs will be inhibited at the same time

(92). Fibroblast activation

protein-α (FAP) is highly expressed in CAFs. The FAP single-chain

antibody is linked to an anti-human CD3 single-chain variable

region (scFv) and loaded into oncolytic adenovirus. FAP scFv, while

specifically recognizing and targeting CAFs, activates T cells and

enhances T-cell-mediated cytotoxic effects on tumor-associated

fibroblasts, thus weakening the cell barrier caused by CAFs and

enhancing oncolytic activity (24,53).

Blood vessels play a vital role in the development

of tumors, providing nutrition and metastasis channels for tumor

cells (93). The phenotype of

vascular endothelial cells changes in the TME. Tumor cells secrete

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other endothelial

growth factors to promote the generation of tumor

neovascularization (94). Given that

the downstream target gene of microRNA (miRNA/miR)-126 is VEGF

(95), miR-126 is loaded into the

oncolytic adenovirus, namely ADCEAP-miR126/34A, which decreases the

generation of tumor blood vessels (96). Concurrently, the VEGF promoter is

inserted into the adenovirus vector, targeting the tumor vascular

endothelial cells via the same mechanism of action enhancing the

oncolysis of adenovirus (97). IL-24

is a tumor suppressor molecule with broad-spectrum antitumor

activity (98). It inhibits the

growth of tumor cells by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis (99). A previous study has demonstrated that

while expressing IL24, CRAd-IL24 significantly increased the

release of virus particles and enhanced their antitumor effect

(6).

Checkpoint molecules are regulatory molecules that

play an inhibitory role in the immune system and are critical to

maintain tolerance, prevent an autoimmune response and minimize

tissue damage by controlling the timing and intensity of the immune

response (100,101). The expression of immunological

checkpoint molecules on immune cells suppresses the immune cell

function as the host fails to produce an effective antitumor immune

response. There are numerous receptors on tumorigenic immune escape

T cells, including co-stimulatory signal receptors that can

stimulate T-cell proliferation, and co-inhibitory signal receptors

that can inhibit T-cell proliferation (102). Immune checkpoint molecules are

predominantly inhibitory molecules, in which the immune checkpoint

on T cells suppresses the immune function of T cells, causing tumor

escape (103). However, the clinical

benefits of monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as

anti-programmed death-1 antibody, are limited to small populations

(104). Zhang et al (105) designed an adenovirus (Ad5-PC) to

express a soluble fusion protein (programmed cell death protein

1/CD137L), which significantly increased the number of T

lymphocytes in the TME and effectively improved the survival rate

of tumor-bearing mice (105). After

loading anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4)

antibody into the adenovirus vector, tumor cells were infected.

CTLA-4 antibody was significantly expressed in tumor cells and its

antitumor activity was significantly enhanced (106). Ad5/3-Δ24aCTLA4 can express CTLA-4

human intact monoclonal antibody, and in the normal donors and

patients with advanced solid tumors in the peripheral blood

mononuclear cells that were tested (107). Ad5/3-Δ24aCTLA4 significantly

enhanced the immune response and activated the pro-apoptotic effect

of T cells (107).

Recently, the transformation technology of oncolytic

adenoviruses has significantly progressed. However, increasing

evidence suggest concerns about the tumor-promoting effect of the

TME. Thus, the transformation of oncolytic viruses into TME has

become a research hot spot; however, the in vitro simulation

of the TME does not accurately reflect the human microenvironment.

Cytokines and growth factors were added to the cell culture, either

co-cultured with tumor cells and other cells, or with

three-dimensional scaffoldings to simulate the TME. However, due to

the complexity of the TME, it remains difficult to completely

simulate the human TME completely in vitro. Currently,

xenotransplantation of immunodeficient mice is the most commonly

used animal experimental method for studying human tumors. Briefly,

human tumor cells are inserted into mice; however, this fails to

fully reflect the human TME. Several factors affect the oncolytic

effect of an oncolytic virus. The strong immune response and severe

cytokine storm when the virus first enters the host may be fatal.

Subsequent challenges arise at later stages during elimination of

oncolytic virus by the immune system of the host. It is

hypothesized that the selection of oncolytic viruses will be the

focus of future research, and it will be individualized, with the

intent that the oncolytic virus most suitable for each patient can

be selected, based on the characteristics of the tumor cells and

the TME.

Not applicable.

This review was funded by Programs for the National

Natural Scientific Foundation of China (grant no. 81430035), the

Major National Science and Technology Projects-Major New Drug

Creation (grant no. 2019ZX09301-132), the Changjiang Scholars and

Innovative Research Team in University (grant no. IRT_15R13), and

the Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Special Project

(grant no. AD17129003).

Not applicable.

XW and YZ conceived the subject of the review. LZ

designed the review. XW wrote the manuscript, performed the

literature research as well as interpreted the relevant literature,

and prepared the figures. LZ analyzed the review critically for

important intellectual content. XW and LZ edited and revised the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Giraldo NA, Sanchez-Salas R, Peske JD,

Vano Y, Becht E, Petitprez F, Validire P, Ingels A, Cathelineau X,

Fridman WH and Sautès-Fridman C: The clinical role of the TME in

solid cancer. Br J Cancer. 120:45–53. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen Y, Liu J, Wang W, Xiang L, Wang J,

Liu S, Zhou H and Guo Z: High expression of hnRNPA1 promotes cell

invasion by inducing EMT in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep.

39:1693–1701. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Choi J, Gyamfi J, Jang H and Koo JS: The

role of tumor-associated macrophage in breast cancer biology.

Histol Histopathol. 33:133–145. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sun Y: Tumor microenvironment and cancer

therapy resistance. Cancer Lett. 380:205–215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Akbulut H, Coleri A, Sahin G, Tang Y and

Icli F: A bicistronic adenoviral vector carrying cytosine deaminase

and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor increases the

therapeutic efficacy of cancer gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther.

30:999–1007. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ashshi AM, El-Shemi AG, Dmitriev IP,

Kashentseva EA and Curiel DT: Combinatorial strategies based on

CRAd-IL24 and CRAd-ING4 virotherapy with anti-angiogenesis

treatment for ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 9:382016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Athanasopoulos T, Munye MM and Yanez-Munoz

RJ: Nonintegrating gene therapy vectors. Hematol Oncol Clin North

Am. 31:753–770. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Salzman R, Cook F, Hunt T, Malech HL,

Reilly P, Foss-Campbell B and Barrett D: Addressing the value of

gene therapy and enhancing patient access to transformative

treatments. Mol Ther. 26:2717–2726. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Stasiak AC and Stehle T: Human adenovirus

binding to host cell receptors: A structural view. Med Microbiol

Immunol. 209:325–333. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Greber UF and Flatt JW: Adenovirus entry:

From infection to immunity. Annu Rev Virol. 6:177–197. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hoeben RC and Uil TG: Adenovirus DNA

replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 5:a0130032013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gao J, Zhang W and Ehrhardt A: Expanding

the spectrum of adenoviral vectors for cancer therapy. Cancers

(Basel). 12:11392020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ip WH and Dobner T: Cell transformation by

the adenovirus oncogenes E1 and E4. FEBS Lett. 594:1848–1860. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bradley RR, Maxfield LF, Lynch DM,

Iampietro MJ, Borducchi EN and Barouch DH: Adenovirus serotype

5-specific neutralizing antibodies target multiple hexon

hypervariable regions. J Virol. 86:1267–1272. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Niemann J and Kuhnel F: Oncolytic viruses:

Adenoviruses. Virus Genes. 53:700–706. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Machitani M, Katayama K, Sakurai F, Matsui

H, Yamaguchi T, Suzuki T, Miyoshi H, Kawabata K and Mizuguchi H:

Development of an adenovirus vector lacking the expression of

virus-associated RNAs. J Control Release. 154:285–289. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zheng Y, Stamminger T and Hearing P:

E2F/Rb family proteins mediate interferon induced repression of

adenovirus immediate early transcription to promote persistent

viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 12:e10054152016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yamauchi S, Zhong B, Kawamura K, Yang S,

Kubo S, Shingyoji M, Sekine I, Tada Y, Tatsumi K, Shimada H, et al:

Cytotoxicity of replication-competent adenoviruses powered by an

exogenous regulatory region is not linearly correlated with the

viral infectivity/gene expression or with the E1A-activating

ability but is associated with the p53 genotypes. BMC Cancer.

17:6222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cervera-Carrascon V, Quixabeira DCA,

Havunen R, Santos JM, Kutvonen E, Clubb JHA, Siurala M, Heiniö C,

Zafar S, Koivula T, et al: Comparison of clinically relevant

oncolytic virus platforms for enhancing T cell therapy of solid

tumors. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 17:47–60. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Huang H, Liu Y, Liao W, Cao Y, Liu Q, Guo

Y, Lu Y and Xie Z: Oncolytic adenovirus programmed by synthetic

gene circuit for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 10:48012019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rosewell Shaw A and Suzuki M: Recent

advances in oncolytic adenovirus therapies for cancer. Curr Opin

Virol. 21:9–15. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ran L, Tan X, Li Y, Zhang H, Ma R, Ji T,

Dong W, Tong T, Liu Y, Chen D, et al: Delivery of oncolytic

adenovirus into the nucleus of tumorigenic cells by tumor

microparticles for virotherapy. Biomaterials. 89:56–66. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tazawaa H, Kagawab S and Fujiwarab T:

Oncolytic adenovirus-induced autophagy: Tumor-suppressive effect

and molecular basis. Acta Med Okayama. 67:333–342. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Freedman JD, Duffy MR, Lei-Rossmann J,

Muntzer A, Scott EM, Hagel J, Campo L, Bryant RJ, Verrill C,

Lambert A, et al: An oncolytic virus expressing a T-cell engager

simultaneously targets cancer and immunosuppressive stromal cells.

Cancer Res. 78:6852–6865. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jung KH, Choi IK, Lee HS, Yan HH, Son MK,

Ahn HM, Hong J, Yun CO and Hong SS: Oncolytic adenovirus expressing

relaxin (YDC002) enhances therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine

against pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 396:155–166. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yokoda RT, Nagalo BM and Borad MJ:

Oncolytic adenoviruses in gastrointestinal cancers. Biomedicines.

6:332018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Quail DF and Joyce JA: Microenvironmental

regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med.

19:1423–1437. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Belli C, Trapani D, Viale G, D'Amico P,

Duso BA, Della Vigna P, Orsi F and Curigliano G: Targeting the

microenvironment in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 65:22–32. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhong S, Jeong JH, Chen Z, Chen Z and Luo

JL: Targeting tumor microenvironment by small-molecule inhibitors.

Transl Oncol. 13:57–69. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Terren I, Orrantia A, Vitalle J,

Zenarruzabeitia O and Borrego F: NK cell metabolism and tumor

microenvironment. Front Immunol. 10:22782019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Maimela NR, Liu S and Zhang Y: Fates of

CD8+ T cells in tumor microenvironment. Comput Struct

Biotechnol J. 17:1–13. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Najafi M, Farhood B and Mortezaee K:

Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and degradation as cancer

drivers. J Cell Biochem. 120:2782–2790. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Guo S and Deng CX: Effect of stromal cells

in tumor microenvironment on metastasis initiation. Int J Biol Sci.

14:2083–2093. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jang I and Beningo KA: Integrins, CAFs and

mechanical forces in the progression of cancer. Cancers (Basel).

11:7212019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jarosz-Biej M, Smolarczyk R, Cichon T and

Kulach N: Tumor microenvironment as A ‘Game Changer’ in cancer

radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 20:32122019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Nishide S, Uchida J, Matsunaga S, Tokudome

K, Yamaguchi T, Kabei K, Moriya T, Miura K, Nakatani T and Tomita

S: Prolyl-hydroxylase inhibitors reconstitute tumor blood vessels

in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 143:122–126. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Carretero R, Sektioglu IM, Garbi N,

Salgado OC, Beckhove P and Hammerling GJ: Eosinophils orchestrate

cancer rejection by normalizing tumor vessels and enhancing

infiltration of CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 16:609–617. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhao H, Tian X, He L, Li Y, Pu W, Liu Q,

Tang J, Wu J, Cheng X, Liu Y, et al: Apj+ vessels drive

tumor growth and represent a tractable therapeutic target. Cell

Rep. 25:1241–1254.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M,

Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et

al: LDHA-Associated lactic acid production blunts tumor

immunosurveillance by T and NK cells. Cell Metab. 24:657–671. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S,

Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G,

Hoves S, et al: Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid

on human T cells. Blood. 109:3812–3819. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T,

Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC,

Phillips GM, et al: Functional polarization of tumour-associated

macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 513:559–563.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ohashi T, Aoki M, Tomita H, Akazawa T,

Sato K, Kuze B, Mizuta K, Hara A, Nagaoka H, Inoue N and Ito Y:

M2-like macrophage polarization in high lactic acid-producing head

and neck cancer. Cancer Sci. 108:1128–1134. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Urbanska K and Orzechowski A:

Unappreciated role of LDHA and LDHB to control apoptosis and

autophagy in tumor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 20:20852019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Fleming V, Hu X, Weber R, Nagibin V, Groth

C, Altevogt P, Utikal J and Umansky V: Targeting myeloid-derived

suppressor cells to bypass tumor-induced immunosuppression. Front

Immunol. 9:3982018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hinshaw DC and Shevde LA: The tumor

microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res.

79:4557–4566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Safarzadeh E, Orangi M, Mohammadi H,

Babaie F and Baradaran B: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells:

Important contributors to tumor progression and metastasis. J Cell

Physiol. 233:3024–3036. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dysthe M and Parihar R: Myeloid-Derived

suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1224:117–140. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ribatti D, Tamma R and Crivellato E: Cross

talk between natural killer cells and mast cells in tumor

angiogenesis. Inflamm Res. 68:19–23. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Albini A, Bruno A, Noonan DM and Mortara

L: Contribution to tumor angiogenesis from innate immune cells

within the tumor microenvironment: Implications for immunotherapy.

Front Immunol. 9:5272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kabiraj A, Jaiswal R, Singh A, Gupta J,

Singh A and Samadi FM: Immunohistochemical evaluation of tumor

angiogenesis and the role of mast cells in oral squamous cell

carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 14:495–502. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shee K, Yang W, Hinds JW, Hampsch RA, Varn

FS, Traphagen NA, Patel K, Cheng C, Jenkins NP, Kettenbach AN, et

al: Therapeutically targeting tumor microenvironment-mediated drug

resistance in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Exp Med.

215:895–910. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan

V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI,

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, et al: Understanding the tumor

immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med.

24:541–550. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

de Sostoa J, Fajardo CA, Moreno R, Ramos

MD, Farrera-Sal M and Alemany R: Targeting the tumor stroma with an

oncolytic adenovirus secreting a fibroblast activation

protein-targeted bispecific T-cell engager. J Immunother Cancer.

7:192019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lang FF, Conrad C, Gomez-Manzano C, Yung

WKA, Sawaya R, Weinberg JS, Prabhu SS, Rao G, Fuller GN, Aldape KD,

et al: Phase I Study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) Oncolytic

Adenovirus: Replication and immunotherapeutic effects in recurrent

malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 36:1419–1427. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Havunen R, Siurala M, Sorsa S,

Grönberg-Vähä-Koskela S, Behr M, Tähtinen S, Santos JM, Karell P,

Rusanen J, Nettelbeck DM, et al: Oncolytic adenoviruses armed with

tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-2 enable successful

adoptive cell therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 4:77–86. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Santos JM, Cervera-Carrascon V, Havunen R,

Zafar S, Siurala M, Sorsa S, Anttila M, Kanerva A and Hemminki A:

Adenovirus coding for interleukin-2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha

replaces lymphodepleting chemotherapy in adoptive T cell therapy.

Mol Ther. 26:2243–2254. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Lee YS and Radford KJ: The role of

dendritic cells in cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 348:123–178.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Palucka K and Banchereau J: Cancer

immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:265–277.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Parnas O, Jovanovic M, Eisenhaure TM,

Herbst RH, Dixit A, Ye CJ, Przybylski D, Platt RJ, Tirosh I,

Sanjana NE, et al: A genome-wide CRISPR screen in primary immune

cells to dissect regulatory networks. Cell. 162:675–686. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Oh DS and Lee HK: Autophagy protein ATG5

regulates CD36 expression and anti-tumor MHC class II antigen

presentation in dendritic cells. Autophagy. 15:2091–2106. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chen L, Hasni MS, Jondal M and Yakimchuk

K: Modification of anti-tumor immunity by tolerogenic dendritic

cells. Autoimmunity. 50:370–376. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Karnell JL, Rieder SA, Ettinger R and

Kolbeck R: Targeting the CD40-CD40L pathway in autoimmune diseases:

Humoral immunity and beyond. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 141:92–103. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Vitale LA, Thomas LJ, He LZ, O'Neill T,

Widger J, Crocker A, Sundarapandiyan K, Storey JR, Forsberg EM,

Weidlick J, et al: Development of CDX-1140, an agonist CD40

antibody for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

68:233–245. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Zafar S, Sorsa S, Siurala M, Hemminki O,

Havunen R, Cervera-Carrascon V, Santos JM, Wang H, Lieber A, De

Gruijl T, et al: CD40L coding oncolytic adenovirus allows long-term

survival of humanized mice receiving dendritic cell therapy.

Oncoimmunology. 7:e14908562018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Eriksson E, Milenova I, Wenthe J, Moreno

R, Alemany R and Loskog A: IL-6 signaling blockade during

CD40-mediated immune activation favors antitumor factors by

reducing TGF-β, collagen type I, and PD-L1/PD-1. J Immunol.

202:787–798. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Guo X, Ding C, Lu J, Zhou T, Liang T, Ji

Z, Xie P, Liu X and Kang Q: HP-NAP ameliorates OXA-induced atopic

dermatitis symptoms in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol.

42:416–422. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Codolo G, Fassan M, Munari F, Volpe A,

Bassi P, Rugge M, Pagano F, D'Elios MM and de Bernard M: HP-NAP

inhibits the growth of bladder cancer in mice by activating a

cytotoxic Th1 response. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 61:31–40. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

D'Elios MM, Amedei A, Cappon A, Del Prete

G and de Bernard M: The neutrophil-activating protein of

Helicobacter pylori (HP-NAP) as an immune modulating agent. FEMS

Immunol Med Microbiol. 50:157–164. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ramachandran M, Jin C, Yu D, Eriksson F

and Essand M: Vector-encoded Helicobacter pylori

neutrophil-activating protein promotes maturation of dendritic

cells with Th1 polarization and improved migration. J Immunol.

193:2287–2296. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi

L and Allavena P: Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment

targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:399–416. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Ubil E, Caskey L, Holtzhausen A, Hunter D,

Story C and Earp HS: Tumor-secreted Pros1 inhibits macrophage M1

polarization to reduce antitumor immune response. J Clin Invest.

128:2356–2369. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Myers KV, Amend SR and Pienta KJ:

Targeting Tyro3, Axl and MerTK (TAM receptors): Implications for

macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 18:942019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Huang YJ, Yang CK, Wei PL, Huynh TT,

Whang-Peng J, Meng TC, Hsiao M, Tzeng YM, Wu AT and Yen Y:

Ovatodiolide suppresses colon tumorigenesis and prevents

polarization of M2 tumor-associated macrophages through YAP

oncogenic pathways. J Hematol Oncol. 10:602017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Cho H, Seo Y, Loke KM, Kim SW, Oh SM, Kim

JH, Soh J, Kim HS, Lee H, Kim J, et al: Cancer-Stimulated CAFs

enhance monocyte differentiation and protumoral TAM activation via

IL6 and GM-CSF secretion. Clin Cancer Res. 24:5407–5421. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kuryk L, Moller AW, Garofalo M, Cerullo V,

Pesonen S, Alemany R and Jaderberg M: Antitumor-specific T-cell

responses induced by oncolytic adenovirus ONCOS-102

(AdV5/3-D24-GM-CSF) in peritoneal mesothelioma mouse model. J Med

Virol. 90:1669–1673. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hayat SMG, Biancon V, Pirro M, Jaafari MR,

Hatamipour M and Sahebkar A: CD47 role in the immune system and

application to cancer therapy. Cell Oncol (Dordr.). 43:19–30. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Huang Y, Lv SQ, Liu PY, Ye ZL, Yang H, Li

LF, Zhu HL, Wang Y, Cui LZ, Jiang DQ, et al: A SIRPα-Fc fusion

protein enhances the antitumor effect of oncolytic adenovirus

against ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 14:657–668. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zhang KL, Li RP, Zhang BP, Gao ST, Li B,

Huang CJ, Cao R, Cheng JY, Xie XD, Yu ZH and Feng XY: Efficacy of a

new oncolytic adenovirus armed with IL-13 against oral carcinoma

models. Onco Targets Ther. 12:6515–6523. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Scott EM, Jacobus EJ, Lyons B, Frost S,

Freedman JD, Dyer A, Khalique H, Taverner WK, Carr A, Champion BR,

et al: Bi- and tri-valent T cell engagers deplete tumour-associated

macrophages in cancer patient samples. J Immunother Cancer.

7:3202019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Yao C, Ni Z, Gong C, Zhu X, Wang L, Xu Z,

Zhou C, Li S, Zhou W, Zou C and Zhu S: Rocaglamide enhances NK

cell-mediated killing of non-small cell lung cancer cells by

inhibiting autophagy. Autophagy. 14:1831–1844. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Davis MR, Zhu Z, Hansen DM, Bai Q and Fang

Y: The role of IL-21 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett.

358:107–114. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Li Y, Li YF, Si CZ, Zhu YH, Jin Y, Zhu TT,

Liu MY and Liu GY: CCL21/IL21-armed oncolytic adenovirus enhances

antitumor activity against TERT-positive tumor cells. Virus Res.

220:172–178. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Rhode PR, Egan JO, Xu W, Hong H, Webb GM,

Chen X, Liu B, Zhu X, Wen J, You L, et al: Comparison of the

superagonist complex, ALT-803, to IL15 as cancer immunotherapeutics

in animal models. Cancer Immunol Res. 4:49–60. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Yan Y, Li S, Jia T, Du X, Xu Y, Zhao Y, Li

L, Liang K, Liang W, Sun H and Li R: Combined therapy with CTL

cells and oncolytic adenovirus expressing IL-15-induced enhanced

antitumor activity. Tumour Biol. 36:4535–4543. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kubo N, Araki K, Kuwano H and Shirabe K:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J

Gastroenterol. 22:6841–6850. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Chen X and Song E: Turning foes to

friends: Targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 18:99–115. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJ,

Deonarine A, Chan DS, Connell CM, Roberts EW, Zhao Q, Caballero OL,

et al: Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated

fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic

cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:20212–20217. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Erdogan B, Ao M, White LM, Means AL,

Brewer BM, Yang L, Washington MK, Shi C, Franco OE, Weaver AM, et

al: Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote directional cancer cell

migration by aligning fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 216:3799–3816.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Erdogan B and Webb DJ: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts modulate growth factor signaling and extracellular

matrix remodeling to regulate tumor metastasis. Biochem Soc Trans.

45:229–236. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Arwert EN, Milford EL, Rullan A, Derzsi S,

Hooper S, Kato T, Mansfield D, Melcher A, Harrington KJ and Sahai

E: STING and IRF3 in stromal fibroblasts enable sensing of genomic

stress in cancer cells to undermine oncolytic viral therapy. Nat

Cell Biol. 22:758–766. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Puig-Saus C, Gros A, Alemany R and

Cascallo M: Adenovirus i-leader truncation bioselected against

cancer-associated fibroblasts to overcome tumor stromal barriers.

Mol Ther. 20:54–62. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Jing Y, Chavez V, Ban Y, Acquavella N,

El-Ashry D, Pronin A, Chen X and Merchan JR: Molecular effects of

stromal-selective targeting by uPAR-retargeted oncolytic virus in

breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 15:1410–1420. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Czekierdowska S, Stachowicz N, Chrosciel M

and Czekierdowski A: Proliferation and maturation of intratumoral

blood vessels in women with malignant ovarian tumors assessed with

cancer stem cells marker nestin and platelet derived growth factor

PDGF-B. Ginekol Pol. 88:120–128. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik

U, Hovinga KE, Geber A, Fligelman B, Leversha M, Brennan C and

Tabar V: Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour

endothelium. Nature. 468:829–833. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X,

McAnally J, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN: The

endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity

and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 15:261–271. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Feng SD, Mao Z, Liu C, Nie YS, Sun B, Guo

M and Su C: Simultaneous overexpression of miR-126 and miR-34a

induces a superior antitumor efficacy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Onco Targets Ther. 10:5591–5604. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Harada A, Uchino J, Harada T, Nakagaki N,

Hisasue J, Fujita M and Takayama K: Vascular endothelial growth

factor promoter-based conditionally replicative adenoviruses

effectively suppress growth of malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Cancer Sci. 108:116–123. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chen QN, Chen X, Chen ZY, Nie FQ, Wei CC,

Ma HW, Wan L, Yan S, Ren SN and Wang ZX: Long intergenic non-coding

RNA 00152 promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation via

interacting with EZH2 and repressing IL24 expression. Mol Cancer.

16:172017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zhuo B, Wang R, Yin Y, Zhang H, Ma T, Liu

F, Cao H and Shi Y: Adenovirus arming human IL-24 inhibits

neuroblastoma cell proliferation in vitro and xenograft tumor

growth in vivo. Tumour Biol. 34:2419–2426. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zhang Y and Zheng J: Functions of immune

checkpoint molecules beyond immune evasion. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1248:201–226. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Li K and Tian H: Development of

small-molecule immune checkpoint inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1 as a new

therapeutic strategy for tumour immunotherapy. J Drug Target.

27:244–256. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Kurachi M, Barnitz RA, Yosef N, Odorizzi

PM, DiIorio MA, Lemieux ME, Yates K, Godec J, Klatt MG, Regev A, et

al: The transcription factor BATF operates as an essential

differentiation checkpoint in early effector CD8+ T cells. Nat

Immunol. 15:373–383. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Deng J, Wang ES, Jenkins RW, Li S, Dries

R, Yates K, Chhabra S, Huang W, Liu H, Aref AR, et al: CDK4/6

inhibition augments antitumor immunity by enhancing T-cell

activation. Cancer Discov. 8:216–233. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Johnson DB, Sullivan RJ and Menzies AM:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in challenging populations. Cancer.

123:1904–1911. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wei M, Mou T, Shi T, Ma

Y, Cai X, Li Y, Dong J and Wei J: Recombinant adenovirus expressing

a soluble fusion protein PD-1/CD137L subverts the suppression of

CD8+ T cells in HCC. Mol Ther. 27:1906–1918. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Du T, Shi G, Li YM, Zhang JF, Tian HW, Wei

YQ, Deng H and Yu DC: Tumor-specific oncolytic adenoviruses

expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor or

anti-CTLA4 antibody for the treatment of cancers. Cancer Gene Ther.

21:340–348. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Dias JD, Hemminki O, Diaconu I, Hirvinen

M, Bonetti A, Guse K, Escutenaire S, Kanerva A, Pesonen S, Löskog

A, et al: Targeted cancer immunotherapy with oncolytic adenovirus

coding for a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for CTLA-4.

Gene Ther. 19:988–998. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|