AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a master

regulator of energy metabolism and forms a heterotrimer consisting

of a catalytic α-subunit and two regulatory subunits (β and γ).

AMPK is activated via the phosphorylation at Thr172 of the

α-subunit by liver kinase B1 (LKB1) through the interaction of

adenosine monophosphate (AMP) with the AMPK γ-subunit under

nutrient starvation (1–3). The other mechanism of AMPK activation

is the calcium-dependent phosphorylation at Thr172 of the α subunit

by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ)

(2,3). AMPK contributes to several cellular

events, such as protein synthesis, lipid metabolism, glucose

metabolism, anti-inflammation, redox regulation and anti-aging

(1–3). In addition, AICAR, an AMPK activator,

has been shown to suppress several diseases, such as acute and

relapsing colitis (4), autoimmune

encephalomyelitis (5) and acute lung

injury (6). Therefore, the

activation of AMPK may ameliorate inflammatory diseases.

Chronic inflammation has been reported to be a key

event in the development and progression of several diseases

(7–10) and is triggered by multiple immune

cells, including macrophages, T lymphocytes and mast cells

(11). Damage-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs), such as proteins, peptides, fatty acids and

lipoproteins derived from dead cells are recognized by

pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed on the immune cell

surface and induce the secretion of inflammatory molecules,

including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), C-C motif chemokine

2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2/MCP-1) and C-reactive

protein (CRP) (12–14). These molecules damage various tissues

and induce chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis

and type 2 diabetes.

In the present review, we summarize the

AMPK-activating effects of AGE and its components, and discuss the

association between AMPK activation and the ameliorating effects of

AGE on several inflammatory diseases.

AGE has been shown to trigger the activation of AMPK

in the liver, adipose tissues and gastrocnemius muscles in a model

of type 2 diabetes (34). In

addition, AGE has been shown to induce the phosphorylation of AMPK

in the liver in a mouse model of atherosclerosis (23). Accordingly, researchers have

demonstrated that AGE enhances AMPK activity in various tissues and

animal models. However, the mechanisms underlying AGE-induced AMPK

activation are not yet fully understood. Several natural compounds

have been shown to activate AMPK. Resveratrol from red grapes,

curcumin from the turmeric, and berberine from Coptis

chinensis trigger the phosphorylation of Thr172 of the AMPK

α-subunit by increasing the AMP/ATP ratio (38,39).

These compounds decrease ATP production through various mechanisms.

Resveratrol and curcumin inhibit the production of ATP by

suppressing mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase/ATP synthase, whereas

berberine decreases ATP production by blocking respiratory chain

complex I (38,39). SAMC has been shown to increase the

phosphorylation of LKB1 in the liver (37), whereas SAC promotes the activation of

CaMKKβ in human hepatocyte HepG2 cells (35). Therefore, both SAMC and SAC are major

constituents of AGE (15,16), and they are involved in the induction

of the phosphorylation of AMPK by increasing the AMP/ATP ratio

and/or intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Consequently,

AGE containing these components may induce the phosphorylation of

AMPK through these pathways.

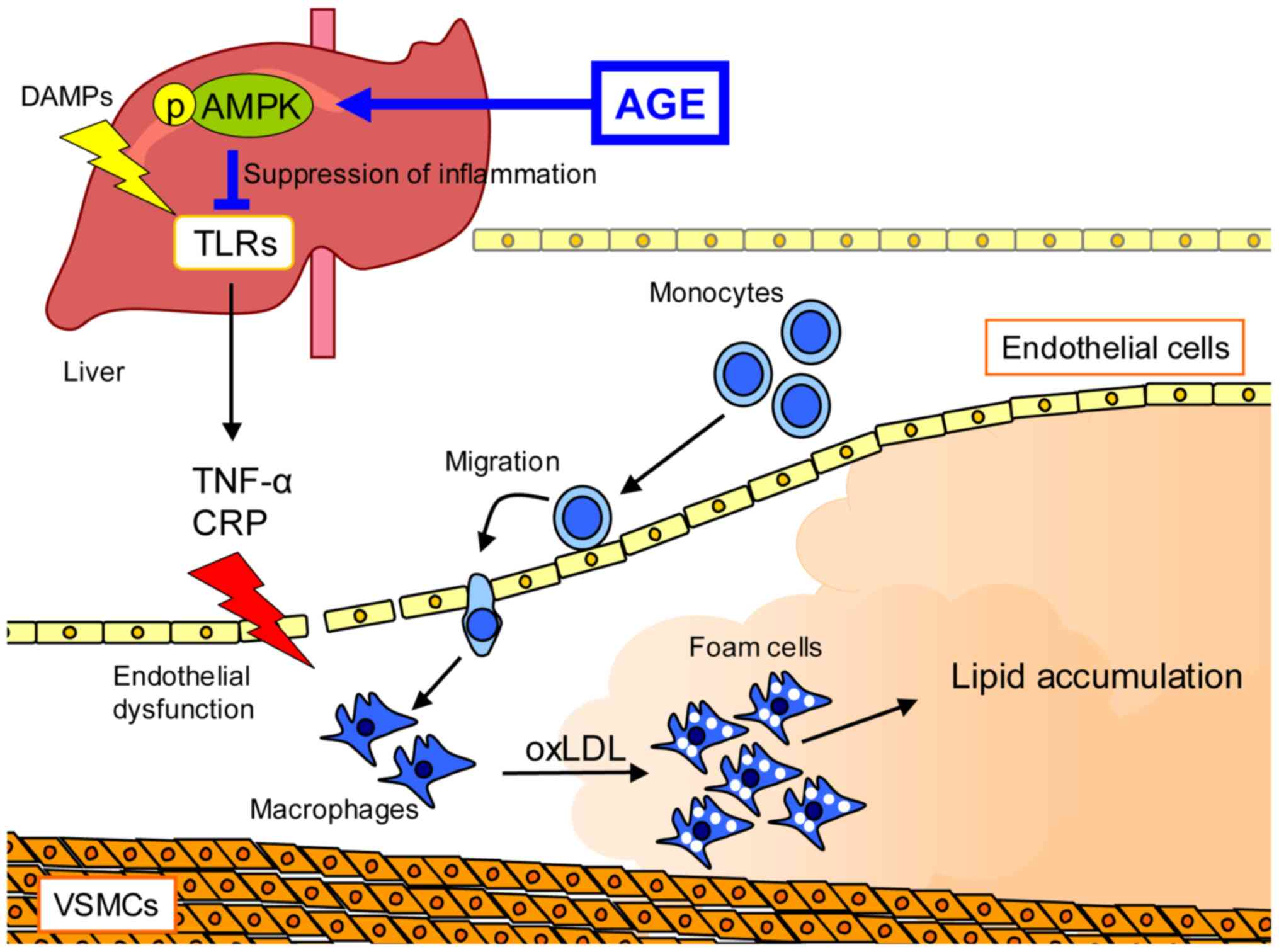

Atherosclerosis is a vascular inflammatory disease,

which causes macrophage infiltration, atherosclerotic lesion

formation and defective efferocytosis (40). AMPK regulates cell apoptosis,

inflammation, cholesterol efflux and efferocytosis via autophagy;

however, its function is impaired in atherosclerosis (41–44). AGE

has been shown to enhance the phosphorylation of AMPK in the livers

of apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE-KO) mice, a mouse model of

atherosclerosis (23). It has

previously been suggested that the activation of AMPK improves

several processes in atherosclerosis. Li et al reported that

the administration of the AMPK activator, S17834, reduced

lipogenesis and the atherosclerotic plaque region by inhibiting

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) cleavage

and nuclear translocation in low-density lipoprotein receptor

(LDLR)-knockout mice (45). In

addition, xanthohumol derived from the hop plant lowers plasma

lipids and inflammatory chemokine production by activating AMPK in

the liver (46). Furthermore,

berberine has been shown to suppress plaque formation by inhibiting

oxidative stress and vascular inflammation through the activation

of the AMPK-nuclear respiratory factor 1 signaling pathway

(47). These findings suggest that

AMPK inhibits plaque formation by modulating lipid metabolism, as

well as by exerting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

AGE has been shown to suppress lipid deposition in

the aorta and to prevent the elevation of serum CRP levels in

ApoE-KO mice (22,23). CRP secreted from hepatocytes is a

marker of chronic inflammation and systemic inflammation induced by

pro-inflammatory cytokines (48,49).

PRRs, including TLRs trigger the production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines by recognizing not only foreign pathogens, but also

cellular components, such as proteins, peptides, fatty acid and

lipoprotein, that are derived from dead cells. Accordingly, chronic

inflammation is caused by the continuous stimulation of these

components (12–14). AGE has been shown to inhibit the TLR

signaling pathway by reducing the phosphorylation of interleukin-1

receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), which is a key regulator of

TLR signaling, in ApoE-KO mice (23). The activation of AMPK also

contributes to the inhibition of the TLR signaling pathway via

several mechanisms (6,50,51).

S1PC induces the degradation of myeloid differentiation primary

response 88 (MyD88) by activating AMPK-mediated autophagy (19). SAC increases cholesterol efflux by

the induction of ATP-binding cassette protein A1 (ABCA1) expression

in THP-1 cells (52). In addition,

the pharmacological or genetic activation of AMPK increases ABCA1

expression through transcriptional activator liver X receptor α,

and promotes cholesterol efflux (53). Therefore, the activation of AMPK is

an important event for the amelioration of atherosclerosis and may

be a therapeutic target for this disease (Fig. 1).

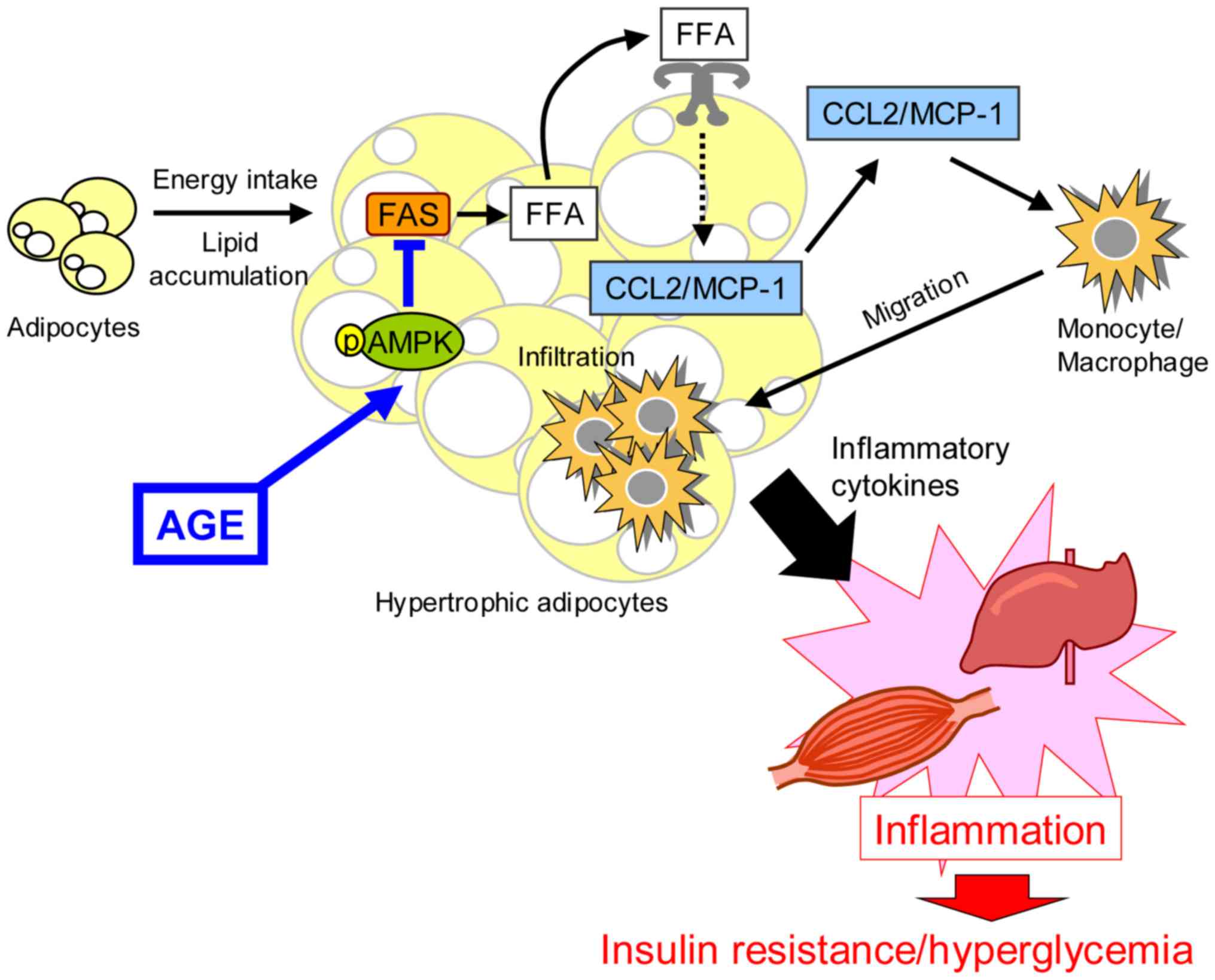

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia

and dyslipidemia associated with insulin resistance (54–56). In

addition, inflammation contributes to the disruption of insulin

signaling and the destruction of adipose homeostasis (57,58).

Furthermore, monocytes and macrophages infiltrate into adipose

tissues and produce inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α,

interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 (59–62).

AMPK is a key molecule for the prevention and/or amelioration of

type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (39,63).

Metformin has been used for the therapy of diabetes through the

activation of AMPK by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I of the

respiratory chain (64,65). Treatment with metformin has been

shown to reduce blood glucose levels, inhibit hepatic

gluconeogenesis and improve insulin sensitivity (66,67). In

addition, resveratrol has been shown to increase glucose uptake and

mitochondrial biogenesis via the activation of AMPK (68–70).

Furthermore, berberine has been shown to improve glucose

intolerance, reduce body weight, increase the expression of the

insulin receptor and LDLR, lower total and LDL cholesterol levels,

and reduce triglyceride levels (71,72).

Therefore, the activation of AMPK helps ameliorate type 2

diabetes.

AGE has been shown to increase the phosphorylation

of AMPK in Tsumura Suzuki Obese Diabetes (TSOD) mice, a mouse model

of type 2 diabetes (34). In

addition, AGE suppresses the plasma glycated albumin level and

improves glucose intolerance in TSOD mice. The level of glycated

albumin is proportional to the amount of glucose in plasma as

glucose nonenzymatically reacts with the amino group of proteins in

plasma (73,74). Blood glucose is taken up via glucose

transporter 4 (GLUT4) in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue

(75,76). However, the production of GLUT4 is

impaired through the inhibition of insulin signaling by

pro-inflammatory cytokines in diabetes (75,76).

Accordingly, inflammation induces insulin resistance and

hyperglycemia. Previous studies have suggested that AGE suppresses

inflammation in clinical trials and animal studies (23,28,29,34). AGE

has been shown to inhibit the expression of

Ccl2/Mcp-1 mRNA in adipose tissue and liver of TSOD

mice (34). PRRs, including TLRs

trigger the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by

recognizing antigens, whereas PRRs have been reported to recognize

not only foreign pathogens, but also cellular components (12–14).

Saturated free fatty acids (FFA) from adipose tissues have been

reported to activate TLR4 and trigger the production of

inflammatory cytokines in immune cells (57,58). The

level of FFA is regulated by fatty acid synthase (FAS), and AMPK

negatively regulates the expression of Fas mRNA by

modulating SREBP-1c (45,77). AGE has inhibited the expression of

Fas mRNA via the activation of AMPK (34). Therefore, AGE can ameliorate

hyperglycemia and insulin resistance by anti-inflammatory effect

via the activation of AMPK in TSOD mice (Fig. 2).

AGE ameliorates atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes

through the suppression of inflammation. In addition, AGE and its

components induce the activation of AMPK in several tissues and

cells. AMPK plays an important role in regulating the inflammatory

response through the inhibition of the TLR signaling pathway. Thus,

AMPK is considered as a possible therapeutic target for

inflammatory-related diseases. Therefore, AGE, which has a

promoting effect on AMPK activation, may prove to be a useful

preparation for the prevention and improvement of various diseases

associated with chronic inflammation.

The authors would like to thank Dr Takami Oka of

Wakunaga Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. for his helpful advice,

encouragement and critical reading of the manuscript.

No funding was received.

Not applicable.

SM, JIS and NM conceived this review. SM, KK and JIS

analyzed the relevant literature. SM wrote the manuscript and

constructed the figures. JIS, KK and NM critically revised the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Hardie DG, Ross FA and Hawley SA: AMPK: A

nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13:251–262. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mihaylova MM and Shaw RJ: The AMPK

signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and

metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 13:1016–1023. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Garcia D and Shaw RJ: AMPK: Mechanisms of

Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Mol

Cell. 66:789–800. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bai A, Ma AG, Yong M, Weiss CR, Ma Y, Guan

Q, Bernstein CN and Peng Z: AMPK agonist downregulates innate and

adaptive immune responses in TNBS-induced murine acute and

relapsing colitis. Biochem Pharmacol. 80:1708–1717. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nath N, Giri S, Prasad R, Salem ML, Singh

AK and Singh I: 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside: A

novel immunomodulator with therapeutic efficacy in experimental

autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 175:566–574. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhao X, Zmijewski JW, Lorne E, Liu G, Park

YJ, Tsuruta Y and Abraham E: Activation of AMPK attenuates

neutrophil proinflammatory activity and decreases the severity of

acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

295:L497–L504. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lorenzatti AJ and Servato ML: New evidence

on the role of inflammation in CVD risk. Curr Opin Cardiol.

34:418–423. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Geovanini GR and Libby P: Atherosclerosis

and inflammation: Overview and updates. Clin Sci (Lond).

132:1243–1252. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu CH, Abrams ND, Carrick DM, Chander P,

Dwyer J, Hamlet MRJ, Macchiarini F, PrabhuDas M, Shen GL, Tandon P,

et al: Biomarkers of chronic inflammation in disease development

and prevention: Challenges and opportunities. Nat Immunol.

18:1175–1180. 2017. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Arulselvan P, Fard MT, Tan WS, Gothai S,

Fakurazi S, Norhaizan ME and Kumar SS: Role of Antioxidants and

Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:52761302016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Conti P and Shaik-Dasthagirisaeb Y:

Atherosclerosis: A chronic inflammatory disease mediated by mast

cells. Cent Eur J Immunol. 40:380–386. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Piccinini AM and Midwood KS: DAMPening

inflammation by modulating TLR signalling. Mediators Inflamm.

2010:6723952010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vénéreau E, Ceriotti C and Bianchi ME:

DAMPs from Cell Death to New Life. Front Immunol. 6:4222015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Patel S: Danger-Associated Molecular

Patterns (DAMPs): The Derivatives and Triggers of Inflammation.

Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 18:632018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Matsutomo T and Kodera Y: Development of

an Analytic Method for Sulfur Compounds in Aged Garlic Extract with

the Use of a Postcolumn High Performance Liquid Chromatography

Method with Sulfur-Specific Detection. J Nutr. 146:450S–455S. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kodera Y, Ushijima M, Amano H, Suzuki JI

and Matsutomo T: Chemical and biological properties of

S−1-propenyl-l-cysteine in aged garlic extract. Molecules.

22:E5702017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nantz MP, Rowe CA, Muller CE, Creasy RA,

Stanilka JM and Percival SS: Supplementation with aged garlic

extract improves both NK and γδ-T cell function and reduces the

severity of cold and flu symptoms: A randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled nutrition intervention. Clin Nutr. 31:337–344.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xu C, Mathews AE, Rodrigues C, Eudy BJ,

Rowe CA, O'Donoughue A and Percival SS: Aged garlic extract

supplementation modifies inflammation and immunity of adults with

obesity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical

trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 24:148–155. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Suzuki JI, Kodera Y, Miki S, Ushijima M,

Takashima M, Matsutomo T and Morihara N: Anti-inflammatory action

of cysteine derivative S−1-propenylcysteine by inducing

MyD88 degradation. Sci Rep. 8:141482018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kyo E, Uda N, Kasuga S and Itakura Y:

Immunomodulatory effects of aged garlic extract. J Nutr. 131((3s)):

1075S–1079S. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Morihara N, Ide N and Weiss N: Aged garlic

extract inhibits CD36 expression in human macrophages via

modulation of the PPARgamma pathway. Phytother Res. 24:602–608.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Morihara N, Hino A, Yamaguchi T and Suzuki

J: Aged garlic extract suppresses the development of

atherosclerosis apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. J Nutr.

146:460S–463S. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Morihara N, Hino A, Miki S, Takashima M

and Suzuki JI: Aged garlic extract suppresses inflammation in

apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 61:17003082017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Matsumoto S, Nakanishi R, Li D, Alani A,

Rezaeian P, Prabhu S, Abraham J, Fahmy MA, Dailing C, Flores F, et

al: Aged Garlic Extract Reduces Low Attenuation Plaque in Coronary

Arteries of Patients with Metabolic Syndrome in a Prospective

Randomized Double-Blind Study. J Nutr. 146:427S–432S. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Budoff M: Aged garlic extract retards

progression of coronary artery calcification. J Nutr. 136

(Suppl):741S–744S. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ried K, Frank OR and Stocks NP: Aged

garlic extract reduces blood pressure in hypertensives: A

dose-response trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 67:64–70. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Matsutomo T, Ushijima M, Kodera Y,

Nakamoto M, Takashima M, Morihara N and Tamura K: Metabolomic study

on the antihypertensive effect of S−1-propenylcysteine in

spontaneously hypertensive rats using liquid chromatography coupled

with quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt

Technol Biomed Life Sci. 1046:147–155. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ried K, Travica N and Sali A: The effect

of aged garlic extract on blood pressure and other cardiovascular

risk factors in uncontrolled hypertensives: The AGE at Heart trial.

Integr Blood Press Control. 9:9–21. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ried K, Travica N and Sali A: The Effect

of Kyolic Aged Garlic Extract on Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and

Cardiovascular Markers in Hypertensives: The GarGIC Trial. Front

Nutr. 5:1222018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hiramatsu K, Tsuneyoshi T, Ogawa T and

Morihara N: Aged garlic extract enhances heme oxygenase-1 and

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit expression via the

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-antioxidant response

element signaling pathway in human endothelial cells. Nutr Res.

36:143–149. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tsuneyoshi T, Kunimura K and Morihara N:

S−1-Propenylcysteine augments BACH1 degradation and heme

oxygenase 1 expression in a nitric oxide-dependent manner in

endothelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 84:22–29. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Thomson M, Al-Qattan KK, Js D and Ali M:

Anti-diabetic and anti-oxidant potential of aged garlic extract

(AGE) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 16:172016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ushijima M, Takashima M, Kunimura K,

Kodera Y, Morihara N and Tamura K: Effects of

S−1-propenylcysteine, a sulfur compound in aged garlic

extract, on blood pressure and peripheral circulation in

spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 70:559–565.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Miki S, Inokuma KI, Takashima M, Nishida

M, Sasaki Y, Ushijima M, Suzuki JI and Morihara N: Aged garlic

extract suppresses the increase of plasma glycated albumin level

and enhances the AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue in

TSOD mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 61:16007972017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hwang YP, Kim HG, Choi JH, Do MT, Chung

YC, Jeong TC and Jeong HG: S-allylcysteine attenuates free

fatty acid-induced lipogenesis in human HepG2 cells through

activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J

Nutr Biochem. 24:1469–1478. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yu L, Di W, Dong X, Li Z, Xue X, Zhang J,

Wang Q, Xiao X, Han J, Yang Y, et al: Diallyl trisulfide exerts

cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in

diabetic state, role of AMPK-mediated AKT/GSK-3β/HIF-1α activation.

Oncotarget. 8:74791–74805. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xiao J, Guo R, Fung ML, Liong EC, Chang

RC, Ching YP and Tipoe GL: Garlic-Derived

S-Allylmercaptocysteine Ameliorates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver

Disease in a Rat Model through Inhibition of Apoptosis and

Enhancing Autophagy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2013:6429202013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim J, Yang G, Kim Y, Kim J and Ha J: AMPK

activators: Mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp

Mol Med. 48:e2242016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Coughlan KA, Valentine RJ, Ruderman NB and

Saha AK: AMPK activation: A therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes?

Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 7:241–253. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bäck M, Yurdagul A Jr, Tabas I, Öörni K

and Kovanen PT: Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis:

Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol.

16:389–406. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Salminen A, Hyttinen JM and Kaarniranta K:

AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-κB signaling and

inflammation: Impact on healthspan and lifespan. J Mol Med (Berl).

89:667–676. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Salminen A and Kaarniranta K:

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via

an integrated signaling network. Ageing Res Rev. 11:230–241. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ou H, Liu C, Feng W, Xiao X, Tang S and Mo

Z: Role of AMPK in atherosclerosis via autophagy regulation. Sci

China Life Sci. 61:1212–1221. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu-Bryan R: Inflammation and

intracellular metabolism: New targets in OA. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 23:1835–1842. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Y, Xu S, Mihaylova MM, Zheng B, Hou X,

Jiang B, Park O, Luo Z, Lefai E, Shyy JY, et al: AMPK

phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic

steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant

mice. Cell Metab. 13:376–388. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Doddapattar P, Radović B, Patankar JV,

Obrowsky S, Jandl K, Nusshold C, Kolb D, Vujić N, Doshi L, Chandak

PG, et al: Xanthohumol ameliorates atherosclerotic plaque

formation, hypercholesterolemia, and hepatic steatosis in

ApoE-deficient mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 57:1718–1728.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Q, Zhang M, Liang B, Shirwany N, Zhu

Y and Zou MH: Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase is

required for berberine-induced reduction of atherosclerosis in

mice: The role of uncoupling protein 2. PLoS One. 6:e254362011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL and De Block CE:

Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature.

444:875–880. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Shoelson SE, Lee J and Goldfine AB:

Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 116:1793–1801.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Rameshrad M, Maleki-Dizaji N, Soraya H,

Toutounchi NS, Barzegari A and Garjani A: Effect of A-769662, a

direct AMPK activator, on Tlr-4 expression and activity in mice

heart tissue. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 19:1308–1317. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mancini SJ, White AD, Bijland S,

Rutherford C, Graham D, Richter EA, Viollet B, Touyz RM, Palmer TM

and Salt IP: Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase rapidly

suppresses multiple pro-inflammatory pathways in adipocytes

including IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 phosphorylation. Mol

Cell Endocrinol. 440:44–56. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Malekpour-Dehkordi Z, Javadi E, Doosti M,

Paknejad M, Nourbakhsh M, Yassa N, Gerayesh-Nejad S and Heshmat R:

S-Allylcysteine, a garlic compound, increases ABCA1

expression in human THP-1 macrophages. Phytother Res. 27:357–361.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kemmerer M, Wittig I, Richter F, Brüne B

and Namgaladze D: AMPK activates LXRα and ABCA1 expression in human

macrophages. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 78:1–9. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Olokoba AB, Obateru OA and Olokoba LB:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of current trends. Oman Med J.

27:269–273. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kahn SE, Cooper ME and Del Prato S:

Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: Perspectives on

the past, present, and future. Lancet. 383:1068–1083. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry

RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, Hu FB, Kahn CR, Raz I, Shulman GI, et al:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 1:150192015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

de Luca C and Olefsky JM: Inflammation and

insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 582:97–105. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Mancuso P: The role of adipokines in

chronic inflammation. ImmunoTargets Ther. 5:47–56. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

McArdle MA, Finucane OM, Connaughton RM,

McMorrow AM and Roche HM: Mechanisms of obesity-induced

inflammation and insulin resistance: Insights into the emerging

role of nutritional strategies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

4:522013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

León-Pedroza JI, González-Tapia LA, del

Olmo-Gil E, Castellanos-Rodríguez D, Escobedo G and González-Chávez

A: Low-grade systemic inflammation and the development of metabolic

diseases: From the molecular evidence to the clinical practice. Cir

Cir. 83:543–551. 2015.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lumeng CN and Saltiel AR: Inflammatory

links between obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest.

121:2111–2117. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Rehman K and Akash MS: Mechanisms of

inflammatory responses and development of insulin resistance: How

are they interlinked? J Biomed Sci. 23:872016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang BB, Zhou G and Li C: AMPK: An

emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell

Metab. 9:407–416. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Hardie DG: AMPK: A target for drugs and

natural products with effects on both diabetes and cancer.

Diabetes. 62:2164–2172. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Rena G, Hardie DG and Pearson ER: The

mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 60:1577–1585.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Rojas LB and Gomes MB: Metformin: An old

but still the best treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab

Syndr. 5:62013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Setter SM, Iltz JL, Thams J and Campbell

RK: Metformin hydrochloride in the treatment of type 2 diabetes

mellitus: A clinical review with a focus on dual therapy. Clin

Ther. 25:2991–3026. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z,

Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P,

Elliott P, et al: Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and

protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and

PGC-1alpha. Cell. 127:1109–1122. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Price NL, Gomes AP, Ling AJ, Duarte FV,

Martin-Montalvo A, North BJ, Agarwal B, Ye L, Ramadori G, Teodoro

JS, et al: SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial

effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metab.

15:675–690. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhu X, Wu C, Qiu S, Yuan X and Li L:

Effects of resveratrol on glucose control and insulin sensitivity

in subjects with type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 14:602017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liang Y, Xu X, Yin M, Zhang Y, Huang L,

Chen R and Ni J: Effects of berberine on blood glucose in patients

with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic literature review and a

meta-analysis. Endocr J. 66:51–63. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lee YS, Kim WS, Kim KH, Yoon MJ, Cho HJ,

Shen Y, Ye JM, Lee CH, Oh WK, Kim CT, et al: Berberine, a natural

plant product, activates AMP-activated protein kinase with

beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic and insulin-resistant

states. Diabetes. 55:2256–2264. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Welsh KJ, Kirkman MS and Sacks DB: Role of

Glycated Proteins in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes:

Research Gaps and Future Directions. Diabetes Care. 39:1299–1306.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Anguizola J, Matsuda R, Barnaby OS, Hoy

KS, Wa C, DeBolt E, Koke M and Hage DS: Review: Glycation of human

serum albumin. Clin Chim Acta. 425:64–76. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Leto D and Saltiel AR: Regulation of

glucose transport by insulin: Traffic control of GLUT4. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 13:383–396. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Huang S and Czech MP: The GLUT4 glucose

transporter. Cell Metab. 5:237–252. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Bijland S, Mancini SJ and Salt IP: Role of

AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue metabolism and

inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond). 124:491–507. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|