Introduction

Lymphatic metastasis is one of the crucial routes of

metastasis in cervical cancer (1)

and treatment failure in cervical cancer is often associated with

lymph node metastasis (2).

Lymphatic vessels are usually considered to serve a passive role in

metastasis, acting merely as a channel for tissue-invading tumor

cells (3). Previous studies have

focused on the immunoregulatory function of lymphatic endothelial

cells (LECs), which are active players in lymphatic metastasis

(3,4). However, it remains unknown whether and

how LECs actively regulate lymphatic metastasis in cancer.

Endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) is a

process via which endothelial cells (ECs) display considerable

plasticity in the transition to mesenchymal cells, which is crucial

for ECs to obtain migratory abilities similar to those of tumor

cells (5,6). During this process, ECs lose their

endothelial markers, such as E-cadherin and CDs, and acquire a

migratory phenotype and mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin and

fibroblast-specific protein 1 (5,6). LECs

also express E-cadherin and can be induced to enter

endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) via WNT5B and Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (7,8).

E-cadherin is a major component of epithelial cell junctions, as

well as a hallmark of EndMT (6,9).

However, the current understanding of the regulatory mechanism

underlying E-cadherin expression in EndMT remains limited. In EMT,

which is analogous to EndMT, epidermal growth factor is suggested

to induce the downregulation of E-cadherin via the ERK pathway

(10), which may activate a similar

signaling pathway in EndMT.

Semaphorins (Semas) are a large family of

extracellular signaling proteins that regulate the motility of

cells during the development of nevi (Sema3A, 3F, 6C and 6D), the

neuroendocrine system (Sema7A and 4D), the immune system (Sema4D),

the reproductive system (Sema3) and cancer progression (Sema4D, 3A

and 6D) (11-13).

Interestingly, Semas antagonize the effect of VEGF (13). In addition, several studies have

reported that Sema3F may affect lymphangiogenesis (14,15).

In a previous study, tumor-associated LECs (TLECs) were isolated

and normal LECs were obtained from tissues using in situ

laser capture microdissection, and it was determined that synthetic

membrane-bound Sema4C functioned as an autocrine factor that

promoted lymphangiogenesis (16).

However, the underlying mechanism of Sema4C in regulating TLEC

biological characteristics is largely unknown.

It has been revealed that tumors or metastasis may

rely, at least in part, on the gene regulatory events in cells that

constitute the primary tumor, as well as the tumor microenvironment

(TME) (17). LECs, which are one of

the most important components in the TME, also exhibit a unique

gene expression pattern compared with non-tumor LECs, such as the

expression of VEGFR3, which is activated under pathological

conditions, including cancer and inflammation (18). LECs bought from

ScienCell™ (cat. no. 2500) are separated from human

lymph nodes, according to the instructions of the cell line. The

differential expression level of genes between normal LECs and

TLECs prompted the present study to assess TLECs from tumors. Flow

cytometry has been indicated to be the most effective method for

isolating cells, as well as analyzing the TME (19,20).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study for the first time

used primary TLECs separated from mouse cervical tumors to study

LEC biological characterization.

The present study evaluated the role of Sema4C in

the transdifferentiation of primary TLECs to determine the tumor

cell-like invasive characteristics. The aim of the present study

was to investigate the effect of Sema4C on the migration of primary

TLEC isolated from tumor tissues by flow cytometry and its

mechanism using lentivirus infection to modulate the expression of

Sema4C. These findings indicated that regulation of the

Sema4C/ERK/E-cadherin pathway may be a novel target for cancer

therapy, which may potentially inhibit endothelial

transdifferentiation into tumor-like cells, thereby preventing the

lymphatic metastasis of cancer. The current preclinical study

provided novel insights into the role of Sema4C in TLECs and

demonstrated the active participation of TLECs in lymphatic

metastasis.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and cell line

All reagents used in the present study were of

analytical grade and are commercially available. The primary

antibodies used were as follows: Sema4C (cat. no. sc-136445; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan

receptor 1 (LYVE1) antibody-Alexa Fluor® 488 for flow

cytometry (cat. no. 53-0433-82; eBioscience; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.); LYVE1 antibody for immunohistochemistry (cat.

no. ab14917; Abcam); VEGFR3 (cat. no. ab51874; Abcam); E-cadherin

(cat. no. ab181296; Abcam); ERK1/2 (cat. no. ab17942; Abcam),

phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2 (cat. no. ab214362; Abcam) and β-actin

(cat. no. ab8227; Abcam). Biotinylated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin

for DAB staining (cat. no. K406511-2) was purchased from Agilent

Technologies, Inc. The ERK inhibitor PD98059 (cat. no. HY-12028)

was purchased from MedChemExpress and cells were treated with 30 mM

for 24 h at room temperature.

The mouse cervical cancer cell line U14 (cat. no.

YB-M060) was purchased from Shanghai Yubo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. 21870076;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) 37˚C with 5%

CO2.with 10% (v/v) FBS (cat. no. 16140071; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) NIH3T3 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast

cell line) was purchased from ATCC (cat. no. CRL-1658), cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (cat. no. 11885084; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% (v/v) FBS (cat. no.

16140071; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C with 5%

CO2. No antibiotics were used in the culture medium. The

use of primary LECs was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics

Committee of Shandong University.

Lentivirus for delivery of full-length

Sema4C and small interfering (si)RNA against Sema4C

All the lentiviruses used in the present study were

purchased from Wester Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (serial no.

WST201710015). Each lentiviral packaging system included a

four-plasmid system (Fig. S1). A

full-length mouse Sema4C open reading frame was obtained via PCR

(PrimeSTAR® HS DNA Polymerase; cat. no. R010A; Takara

BioInc.) (thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95˚C for 3 min

1 cycle, followed by 30 cycles of 94˚C for 30 sec, -55˚C for 40 sec

and -72˚C for 30 sec and 72˚C for 5 min for 1 cycle), using cDNA

(from TLECs) by agarose electrophoresis and gel-cutting recovery as

template (cat. no. DP219-03; Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd.) and the

primer sequences were as follows: Forward,

5'-AGGGTTCCAAGCTTAAGCGGCCGCGCCACCATGGCCCCACACTGGGCTGTCTGG-3' and

reverse, 5'-GATCCATCCCTAGGTAGATGCATTCATACTGAAGACTCCTCTGGGTTG-3'.

The lentivirus used for delivery of full-length Sema4C was LV5. The

final construction was termed LV5-Sema4C. The control construction

was LV5 negative control (empty vector, LV5NC).

The lentivirus used for delivery of siRNA against

Sema4C was LV3. The Sema4C siRNA sense sequence was

5'-CCUAUGCCUUCCAGCCCAADTDT-3' and antisense sequence was

5'-UUGGGCUGGAAGGCAUAGGDTDT-3', and the final construction was

termed LV3-siRNA. The sequence for the control siRNA was a

non-targeting sequence, sense, 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3' and

antisense, 5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA-3', and the lentiviral construct

was termed LV3NC. The Sema4C siRNA has been verified in a previous

study (10).

Animals

C57BL/6 female mice (age, 4-6 weeks; weight, 18-22

g) were purchased from Tengxin Biomedical Technology. The mice were

maintained in the accredited animal facility of Shandong

University. The animal facility had a controlled temperature

(23-25˚C), a 12/12 h light/dark cycle with lights on from 8:00 to

20:00, and a relative humidity (50-60%). The mice had free access

to standard food and water. Animals were cared for by qualified

personnel every day, including weekends and holidays, to monitor

their health and behavior. The hygienic status of the mice was

specific pathogen-free, according to the Association for Assessment

and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International

(Laboratory Animal Center of Tsinghua University) recommendations.

Each group contained 3 mice, and there were three time points (days

5, 7 and 14 after the injection of U14 cells) and 9 mice in total.

No mouse died until the end of the experiments. All the experiments

were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of

Health Guide of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All the

experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use

Committee of Shandong University for animal ethics [approval no.

KYLL-2015(KS)-079].

Mouse xenograft tumor model

The mice were anesthetized using

isoflurane/O2 flow (4% induction and 2% maintenance

dose) in an induction chamber. Forceps were used to touch the leg

of the mouse, which was used to confirm that the mouse was fully

unconscious. The mice received 100 µl (~1x107) U14

cells, resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium, subcutaneously into the

left shoulder. A total of 2 weeks after the injection, the animals

was euthanized and the tumor volume was calculated according to the

following formula: Length x width2/2(21). The cage was placed in a chamber with

CO2, and CO2 was turned on for ≥20 min at 2

l/min. The percentage of the chamber volume/min displaced by the

flow rate of CO2 was 20% (April 2019). CO2

was maintained for ≥1 min after the mice stopped breathing. The

sacrificed mice were placed on a polystyrene board, and the tumor

was removed and measured.

Separation of TLECs via flow

cytometry

Tumor tissue cells were dissociated using 1%

collagenase (cat. no. C2139; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min

at 37˚C and 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution, (cat. no. 25200056; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 5-8 min at room temperature.

Cell suspensions were filtered through cell sieves (200-µm mesh).

After incubation for 48 h at 37˚C with 5% CO2, the

suspended cells were removed and incubated with a monoclonal

antibody against mouse LYVE1-Alexa Fluor 488 or IgG1 kappa Isotype

Control-Alexa Fluor 488 (1:25; cat. no. 53-4714-80; EBioscience;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature for 30 min,

after adjusting the cell density to 5-8x106/ml. The

samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur apparatus (BD Biosciences)

and cells that expressed LYVE1 were isolated. LECs were cultured in

EBM-2 medium (Lonza Group Ltd.) with 2% (v/v) FBS (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C with 5% CO2.

Immunohistochemistry for the

quantification of lymphatic microvessel density (LMVD)

Immunohistochemical analysis of LYVE1 was performed

using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method. Fresh tissue was

fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and embedded using paraffin

at room temperature. Dewaxed and rehydrated 5-µm mouse tumor tissue

sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 10

min at room temperature and then rinsed with PBS for 3 times.

Sections were blocked with 5% BSA (w/v) in PBS (cat. no. A1993;

MilliporeSigma) for 20 min at room temperature and with a rabbit

polyclonal anti-mouse LYVE1 antibody (1:100 dilution) or with PBS

as the negative control overnight at 4˚C. The detection system was

Dako LSAB KIT (cat. no. K406511-2; Agilent Technologies, Inc).

Sections were then washed with PBS and biotinylated anti-rabbit

immunoglobulin (1:200) was added to the sections for 30 min at room

temperature. Peroxidase-conjugated avidin (1:400) was then applied

after the sections were washed with PBS. The peroxidase activity

was detected by exposing the sections to a solution of 0.05%

3,3'-diaminobenzidine and 0.01% H2O2 in

Tris-HCl buffer (3,3'-diaminobenzidine solution) for 10 min at room

temperature. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for

30 sec at room temperature. The stained sections were then analyzed

using standard light microscopy (Eclipse 200; Nikon Corporation).

Under a low magnification, the most vascularized intratumoral areas

were selected (hot spots). The number of immunostained lymphatic

vessels observed in three hot spot areas at x400 magnification was

counted. LMVD was expressed as the mean value (total number of

vessels in three hot spot microscopic fields/3).

Confocal microscopy imaging

Frozen tissue sections (5-µm, solidified in liquid

nitrogen) were blocked with 5% BSA (w/v) in PBS for 20 min at room

temperature. The LYVE1 (1:50) or Sema4C (1:20) primary antibodies

were applied to the slides at 4˚C overnight. After incubation with

the primary antibodies, the slides were washed three times with

cold PBS and incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse (cat.

no. A5608; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) or Cy3-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat, no. A0516; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at a 1:50 dilution in PBS for 30 min at room

temperature. The nuclei were stained for 5 min at room temperature

with DAPI. The slides were rinsed with PBS and observed using a

confocal microscope and 3 fields for analyzed per sample (Olympus

Corporation) (magnification, x600).

Immunohistochemistry for

identification of TLECs

Immunohistochemical identification analysis of TLECs

was performed using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method.

TLECs were incubated on coverslips (2x104/ml) in a

12-well plate and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at

room temperature. The cells were blocked with 5% BSA (cat. no.

A1993; MilliporeSigma w/v) in PBS for 60 min at room temperature,

and then incubated overnight at 4˚C with monoclonal anti-mouse

VEGFR3 antibody (1:30) and then washed with PBS. Goat-anti-rat

HRP-immunoglobulin (cat. no. ab97057; Abcam) was then added to the

sections for 30 min at 37˚C. After the sections were washed with

PBS, peroxidase-conjugated avidin (Dako; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.) was applied. The peroxidase activity was detected by exposing

the sections to a 3,3'-diaminobenzidine solution for 10 min at room

temperature. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin at 5

min at room temperature and analyzed using an inverted light

microscope (Olympus Corporation) (magnification, x100).

Cell transduction

The primary TLECs were cultured in 24-well tissue

culture plates or flasks at 37˚C with 5% CO2 in a

humidified incubator (Heraeus Group). For the lentiviral infection,

the cells (105/ml/well; 200 µl) were incubated with

lentivirus (MOI=40) when the cells were 70% confluent, according to

the preliminary experiment. The cells were infected for 72 h for

the subsequent experiments. The package system was a four-plasmid

system, including LV5-GFP/LV3-GFP, PG-p1-VSVG, PG-P2-REV and

PG-P3-RR, purchased from Wester Biological Technology Co., Ltd. The

results of transduction were detected using a confocal microscope

(Olympus Corporation; magnification, x100).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was isolated from transduced

TLECs using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed via RT

using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham;

Cytiva) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was

performed on an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection system (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using a QuantiTect SYBR

Green kit (Qiagen, Inc.). The primers were designed using Primer

Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc.), as identified using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST),

and were purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Each sample was run in triplicate. The conditions for the

qPCR reaction were as follows: One cycle at 50˚C for 15 min; one

cycle at 94˚C for 4 min; and 35 cycles at 94˚C for 20 sec, 60˚C for

30 sec and 70˚C for 35 sec. At the end of the PCR reaction, the

samples were subjected to a melting curve analysis to confirm the

specificity of the amplification. The Sema4C primer sequences were:

Forward, 5'-CCTCCCATCTGTATGTCTGCG-3' and reverse,

5'-GCTGGGTCATATGGGCATTTAC-3'. E-cadherin, forward

5'-TCCTTGGGTGGTCTTGAT-3' and reverse 5'-CATATCGCTGTTCTTCGTT-3'; ERK

1/2 forward, 5'-TCACACAGGGTTCTTGACAG-3' and reverse

5'-GGAGATCCAAGAATACCCA-3'. For the internal standard, the following

β-actin primer sequences were used: Forward,

5'-GAGACCTTCAACACCCCAGC-3' and reverse, 5'-ATGTCACGCACGATTTCCC-3'.

The method of quantification used was 2-ΔΔCq (22).

Immunoblotting

For western blot analyses, the TLEC cells treated

with lentivirus or/and PD98059 were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no.

P0013C; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) [50 mM Tris/HCl, pH

7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS and 0.5% (w/v) sodium

deoxycholate]. Equivalent amounts of the cell extracts (BCA method,

20 µg) were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF

membrane. The membranes were blocked in 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0)

containing 125 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skimmed milk for 1 h

at room temperature, and then incubated with the diluted primary

antibodies (Sema4C, 1:500; E-cadherin, ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2, all

1:2,000; β-actin, 1:1,000) at 4˚C overnight. After incubation with

the primary antibodies, the alkaline phosphatase-conjugated

anti-rabbit (cat. no. A9919; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and

anti-mouse (cat. no. A4312; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were added

at a 1:1,000 dilution. The immunoreactive bands were visualized

using the ECL western blotting technique. The software used for

densitometry was Image J v.1.8.0 (National Institutes of

Health).

Migration assay

For the migration assay, 5x103 TLEC

cells, treated with lentivirus or/and PD98059 were seeded in 100 µl

EBM-2 media with 1% FBS on the top of polyethylene terephthalate

membranes within Transwell cell culture inserts (24-well inserts;

pore size, 8 µm; Corning, Inc.). The bottom chamber was filled with

600 µl EBM-2 media containing 2% FBS and 100 µl supernatant from

NIH3T3 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line) to act as a

chemotactic factor. The cells were incubated for 48 h at 37˚C with

5% CO2. Subsequently, the cells were fixed in 2.5% (v/v)

glutaraldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and stained for 15

min with crystal violet at room temperature. Cells on the bottom

were visualized under an inverted light microscope (Leica

MicroSystems GmbH) and were quantified by counting the number of

cells in three randomly selected fields at a x100 magnification

(Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and

statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 13.0 software

(SPSS, Inc.). The experiments were repeated three times.

Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed

by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Separation of TLECs from a mouse

xenograft cervical tumor model

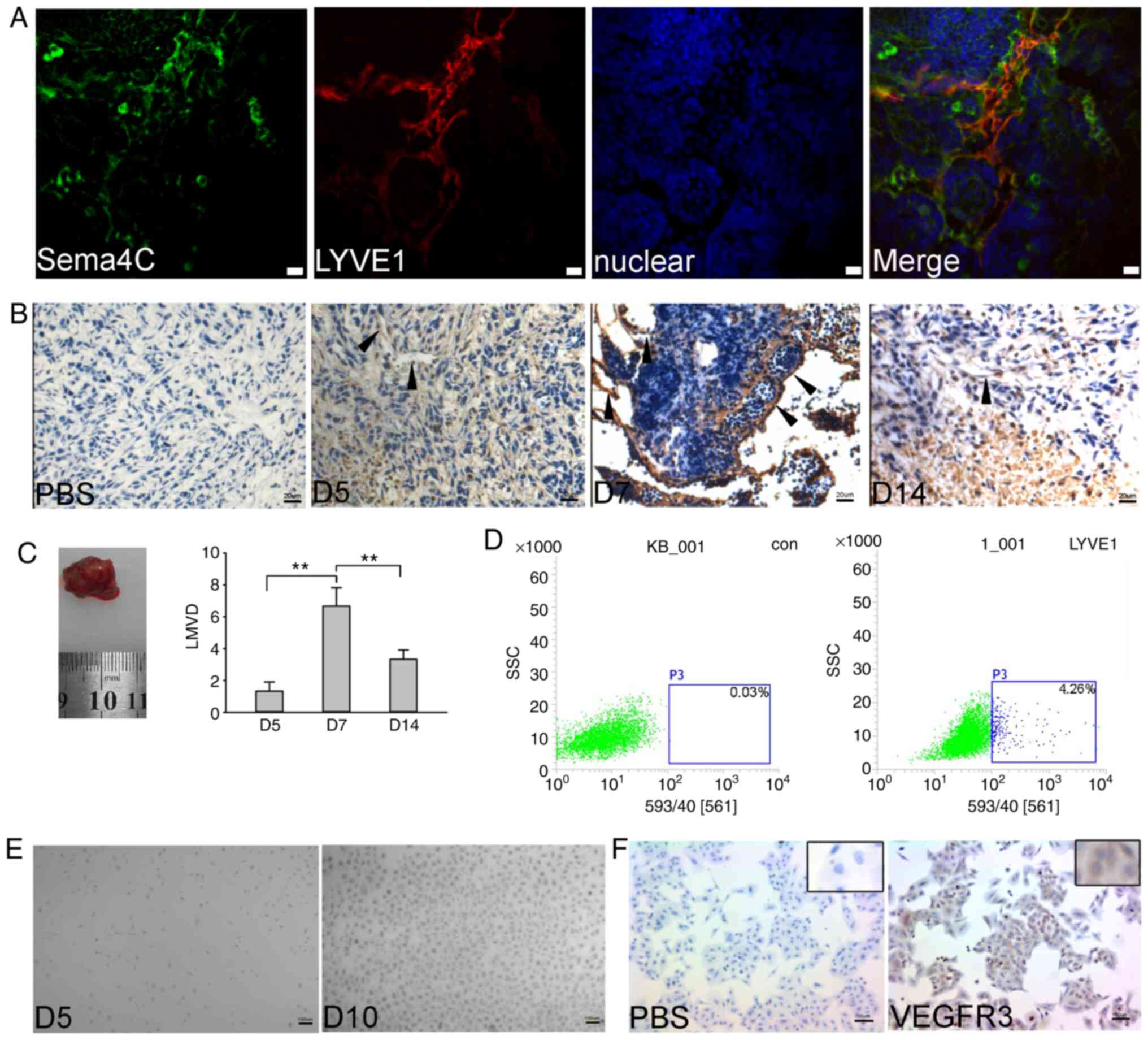

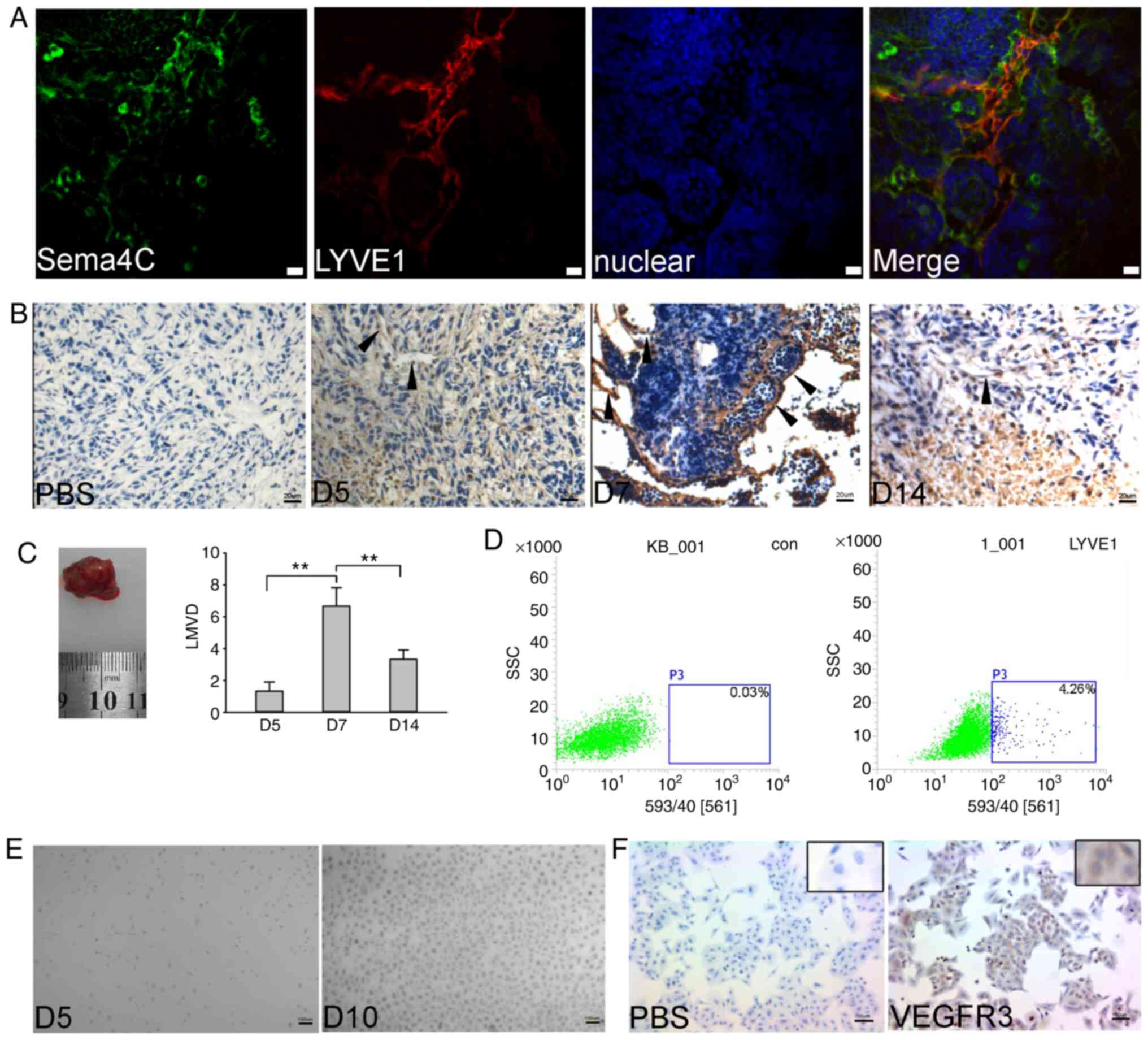

Our previous study detected the co-localization of

Sema4C and LYVE1 in human breast carcinoma (16). Firstly, the present study determined

the expression level of Sema4C in TLECs in mouse cervical tumor

tissue. Using a confocal microscope, LYVE1 was used to detect

lymphatic vessels, and co-localization (merge) was identified

between Sema4C (green) and LYVE1 (red; Fig. 1A). Primary TLECs were used to mimic

the entire TME of cervical tumors, including the immune and

proliferative conditions, as well as the interactions among cells,

using C57BL/6 mice with U14 tumor xenografts. U14 cells were

injected subcutaneously into the left shoulder, and LMVD was

examined using LYVE1 immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1B). As determined via LMVD analysis,

when the tumor grew to 1.0-1.5 cm3 [long diameter

(length), 1.4-1.8 cm; short diameters (width), 1.2-1.8 cm], ~1 week

after injection, the lymphatic vessel density notably increased,

compared with the 5 days group (Fig.

1C). After 14 days, massive necrosis occurred, and the density

of lymphatic vessels was significantly decreased, compared with the

7 days group. Therefore, the appropriate time for the isolation of

TLECs was considered to be day 7 after tumor cell injection.

Moreover, LYVE1-positive cells were separated via flow cytometry

(Fig. 1D). The cells were cultured

successfully and appeared as a typical monolayer (Fig. 1E). VEGFR3 was used to identify the

separated cells (Fig. 1F), and it

was observed that the majority of the cells were positive for

VEGFR3. Thus, the separated cells were positive for both LYVE1 and

VEGFR3.

| Figure 1TLECs isolated from a mouse xenograft

tumor. (A) Localization of Sema4C was detected in mouse tumor

tissue. In lymphatic vessels, Sema4C (green) was co-localized with

LYVE1 (red). Nuclei were identified via DAPI staining (blue). Scale

bars, 20 µm. (B) LYVE1 immunohistochemical analysis indicated that

day 7 after U14 cell injection was the most suitable time for

isolation of TLECs. Arrowheads demonstrate TLEC positive staining.

Scale bars, 20 µm. (C) Tumor image indicated the tumor size at day

7 after injection, and quantification of the numbers of lymphatic

vessels on day 5, 7 and 14 was performed. (D) Tumor tissues were

dissociated into a cell suspension and then stained for

LYVE1-phycoerythrin. LYVE1-positive cells were separated via flow

cytometry. The control group was used non-specific IgG. (E) TLECs

were cultured in EBM-2 medium for 5 and 10 days. Scale bars, 10 µm.

(F) VEGFR3-positive TLECs were identified via immunohistochemistry.

Scale bars, 100 µm. The experiments were repeated three times.

**P<0.01. TLECs, tumor-associated lymphatic

endothelial cells; LYVE1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan

receptor 1; Sema4C, semaphorin 4C; LMVD, lymphatic microvessel

density; SSC, side-scattered light; con, control. |

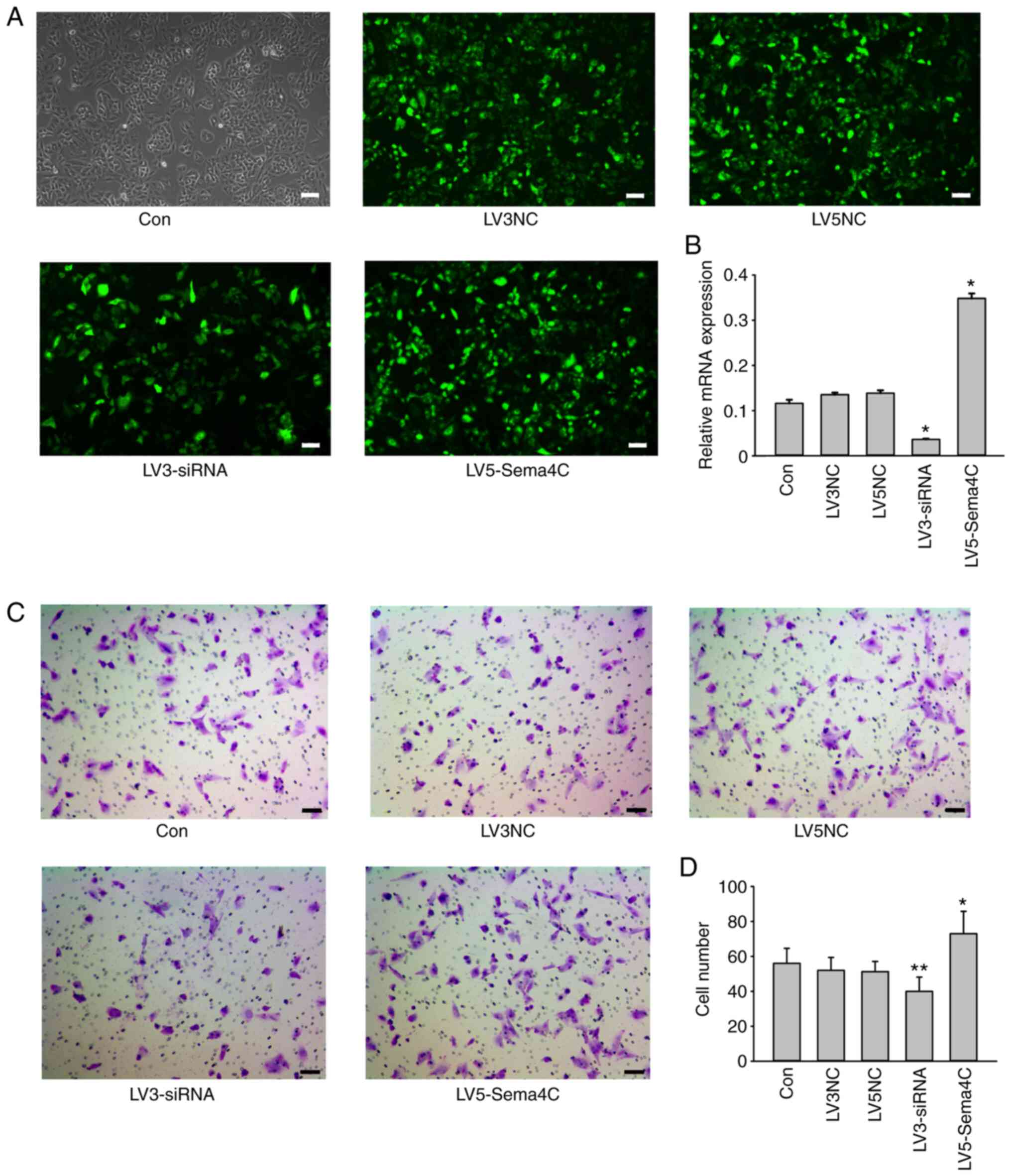

Sema4C regulates the migratory ability

of TLECs

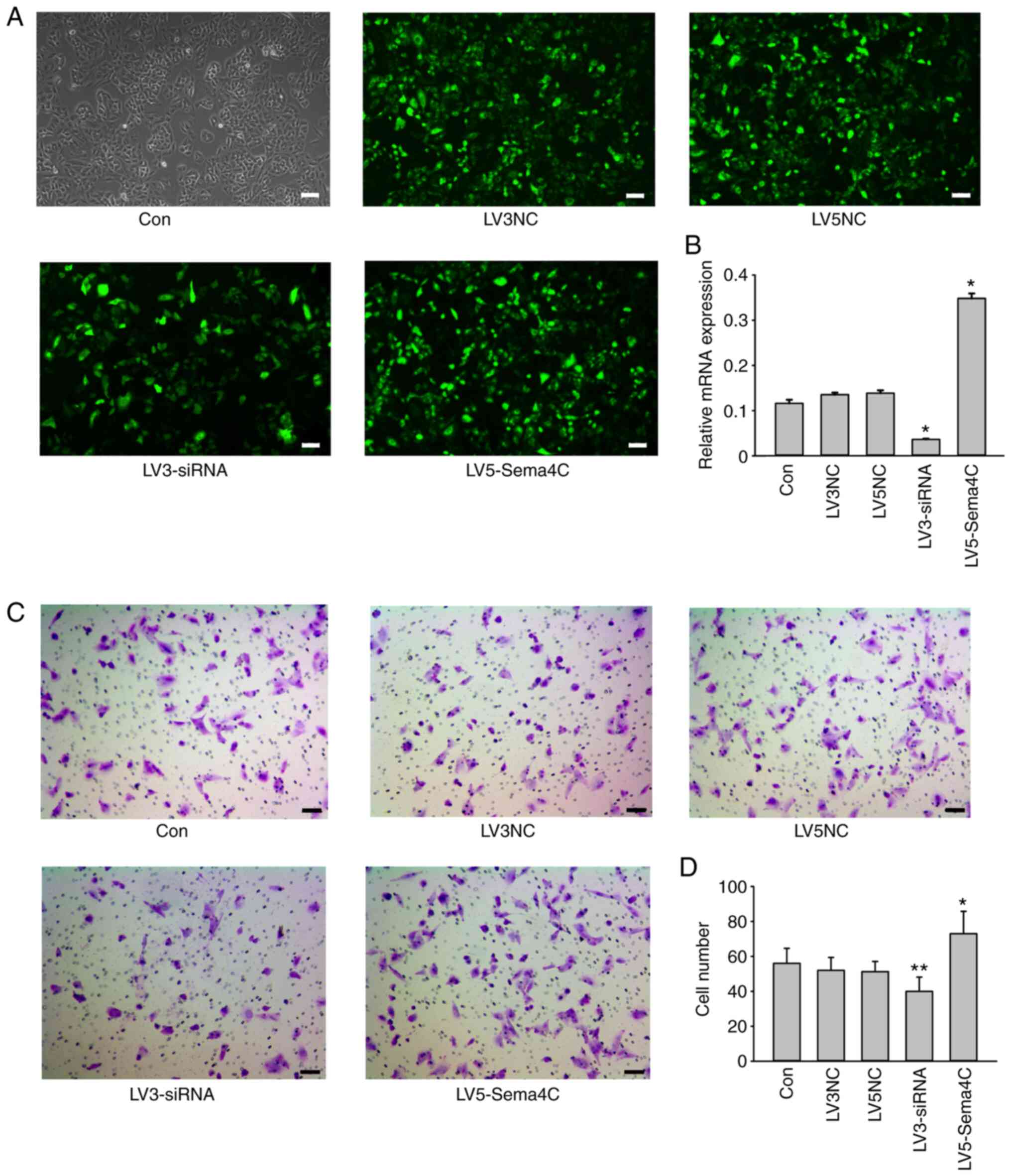

The expression levels of the target gene Sema4C were

altered via lentiviral infection, and non-infected cells were used

as blank controls (Fig. 2A).

LV3-siRNA and full-length LV5-Sema4C, as well as the control

lentiviruses LV3NC and LV5NC, all expressed green fluorescent

protein (GFP) at a MOI of 40 at 72 h after transduction. The

efficiency of the silencing lentivirus and the overexpression

lentivirus infection was ~90%, according to GFP expression assessed

via fluorescence microscopy. The qPCR results demonstrated a ~70%

reduction and a 3.5-fold increase in the Sema4C mRNA expression

levels in the LV3-siRNA and LV5-Sema4C groups, respectively,

compared with the control (Fig.

2B), both of which were statistically significant.

Subsequently, the effects of Sema4C on the invasiveness of the

TLECs were examined using a classical Transwell model. The number

of cells at the bottom of the membrane, which reflects the

migration of cells, was 56±9, 52±8, 51±6, 40±8 and 73±13 for the

control, LV3NC, LV5NC, LV3-siRNA and LV5-Sema4C groups,

respectively. Cells at the bottom of the membrane were

significantly reduced in the LV3-siRNA compared with the LV3NC

group, and significantly increased in the LV5-Sema4C compared with

the LV5NC group (Fig. 2C). Thus,

silencing of Sema4C inhibited, and overexpression of Sema4C

induced, the migratory ability of TLECs.

| Figure 2Role of Sema4C expression in the

migratory ability of TLECs. (A) TLECs treated with lentiviral

medium only, lentiviral control vector for Sema4C siRNA, lentiviral

control vector for full-length Sema4C, Sema4C siRNA and full-length

Sema4C. Scale bars, 10 µm. (B) TLECs with LV3-siRNA or LV5-Sema4C

were generated, and Sema4C mRNA expression was measured via reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. (C) Migratory ability of cells was

assessed using a Transwell assay. (D) Quantification of the number

of cells at the bottom of the Transwell chamber. The experiments

were repeated three times. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 LV3-siRNA group vs. LV3NC group; LV5-Sema4C

group vs. LV5NC group. Sema4C, semaphorin 4C; siRNA, small

interfering RNA; NC, negative control; TLECs, tumor-associated

lymphatic endothelial cells. |

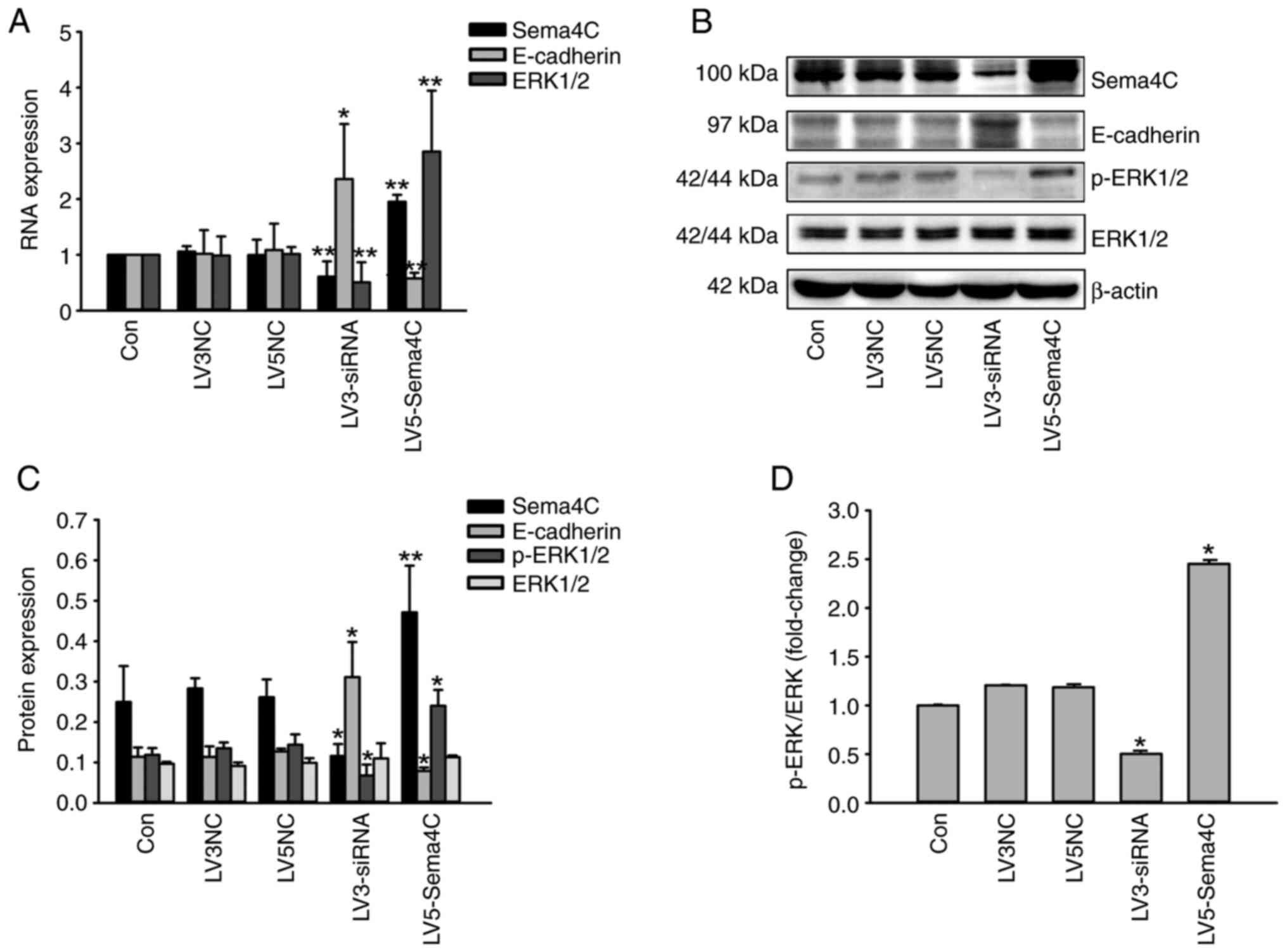

Sema4C regulates E-cadherin and ERK1/2

in TLECs

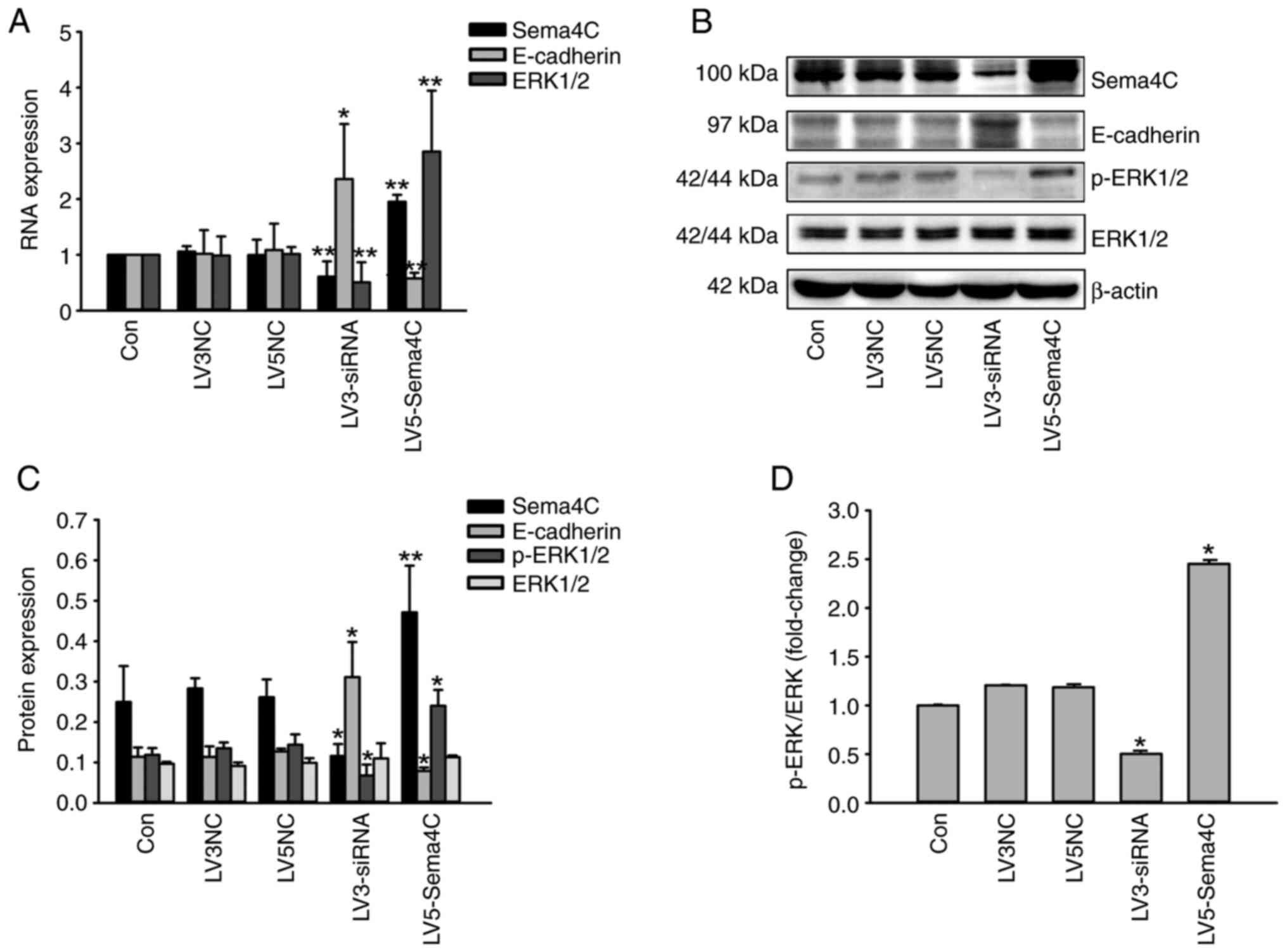

Based on the previously reported literature

(10), a possible signaling pathway

(Sema4C-E-caherin) underlying cell migration was investigated. It

was revealed that Sema4C overexpression significantly inhibited the

expression level of E-cadherin in the LV5-Sema4C group compared

with LV5NC, whereas silencing of Sema4C significantly promoted its

expression in the LV3-siRNA group compared with the LV3NC group.

Moreover, the expression level of p-ERK1/2, a protein

phosphorylation of ERK1/2 which constitutes the active form of

ERK1/2, was significantly altered after lentiviral infection of the

Sema4C full-length gene or Sema4C siRNA, compared with the LV5NC or

LV3NC group, respectively. p-ERK could not be tested at the RNA

level, so total ERK was tested at the RNA level to reveal the

regulation of Sema4C (Fig. 3A). At

the protein level, there were no significantly changes in total ERK

(Fig. 3B and C). Therefore, it was indicated that Sema4C

stimulated the phosphorylation of ERK. A similar pattern was

observed for mRNA and protein expression levels of Sema4C and

E-cadherin using RT-qPCR (Fig. 3A)

and western blotting (Fig. 3B and

C), respectively. Fig. 3D presents the p-ERK/ERK ratio in the

five groups, and it was indicated that the activation of ERK was

significantly reduced in the LV3-siRNA group compared with LV3NC,

while it was significantly enhanced in the LV5-Sema4C group

compared with LV5NC.

| Figure 3Role of Sema4C expression on

E-cadherin and ERK1/2 expression of tumor-associated lymphatic

endothelial cells. (A) Assessment of the mRNA expression levels of

Sema4C, E-cadherin and ERK1/2 using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. (B) Protein expression levels of

Sema4C, E-cadherin, p-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 were detected using

western blot analysis. (C) Semiquantitative analysis of protein

expression levels of Sema4C, E-cadherin, p-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2.

(D) Expression of p-ERK1/2 was normalized to total ERK1/2, and

represented as fold change over the control group. The experiments

were repeated three times. *P<0.05 LV5-Sema4C group

vs. LV5 NC group, **P<0.01 LV3-siRNA group vs. LV3NC

group. Sema4C, semaphorin 4C; p, phosphorylated; siRNA, small

interfering RNA; NC, negative control. |

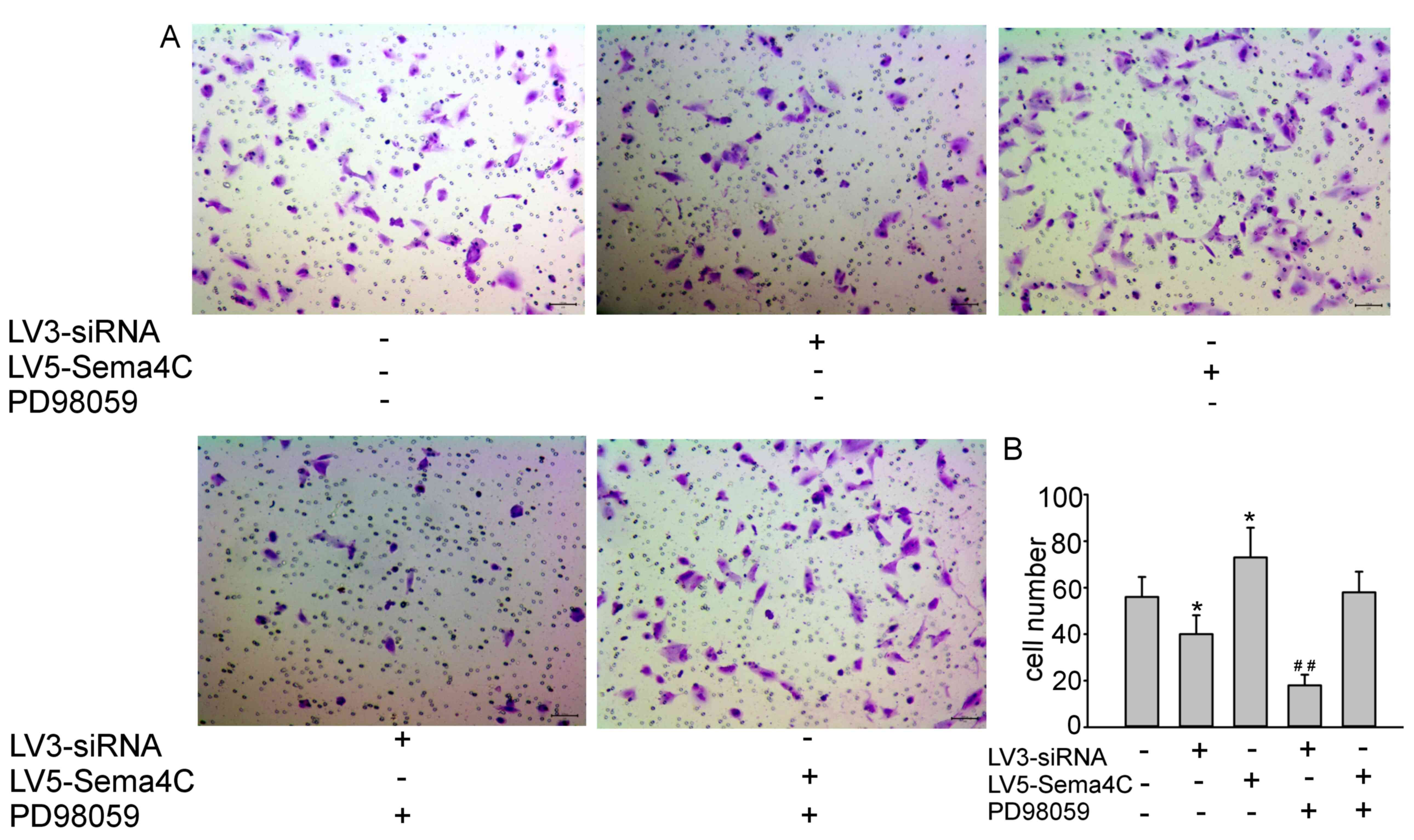

Sema4C regulates migration in TLECs

via ERK activation

It was hypothesized that Sema4C regulated EndMT

partially via the regulation of E-cadherin, which is one of the

most important characteristics of EndMT. The ERK inhibitor PD98059

(30 mM for 24 h at room temperature) was employed to determine the

alterations in the cell migratory ability following Sema4C

silencing or overexpression via lentiviral infection. The results

demonstrated that PD98059 enhanced the inhibition of cell migration

induced by Sema4C siRNA compared with the control group (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the addition of

PD98059 reversed the promotion of TLEC migration induced following

overexpression of Sema4C (Fig. 4A).

The cell numbers at the bottom of the membrane, as presented in the

bar graph, were 56±9, 40±8, 73±13, 18±5 and 58±9 for control,

LV3-siRN-, LV5-Sema4C, LV3-siRNA + PD98059 and LV5-Sema4C + PD98059

groups, respectively, reflecting the migration of the cells

(Fig. 4B).

ERK inhibitor stimulates E-cadherin

expression by blocking Sema4C

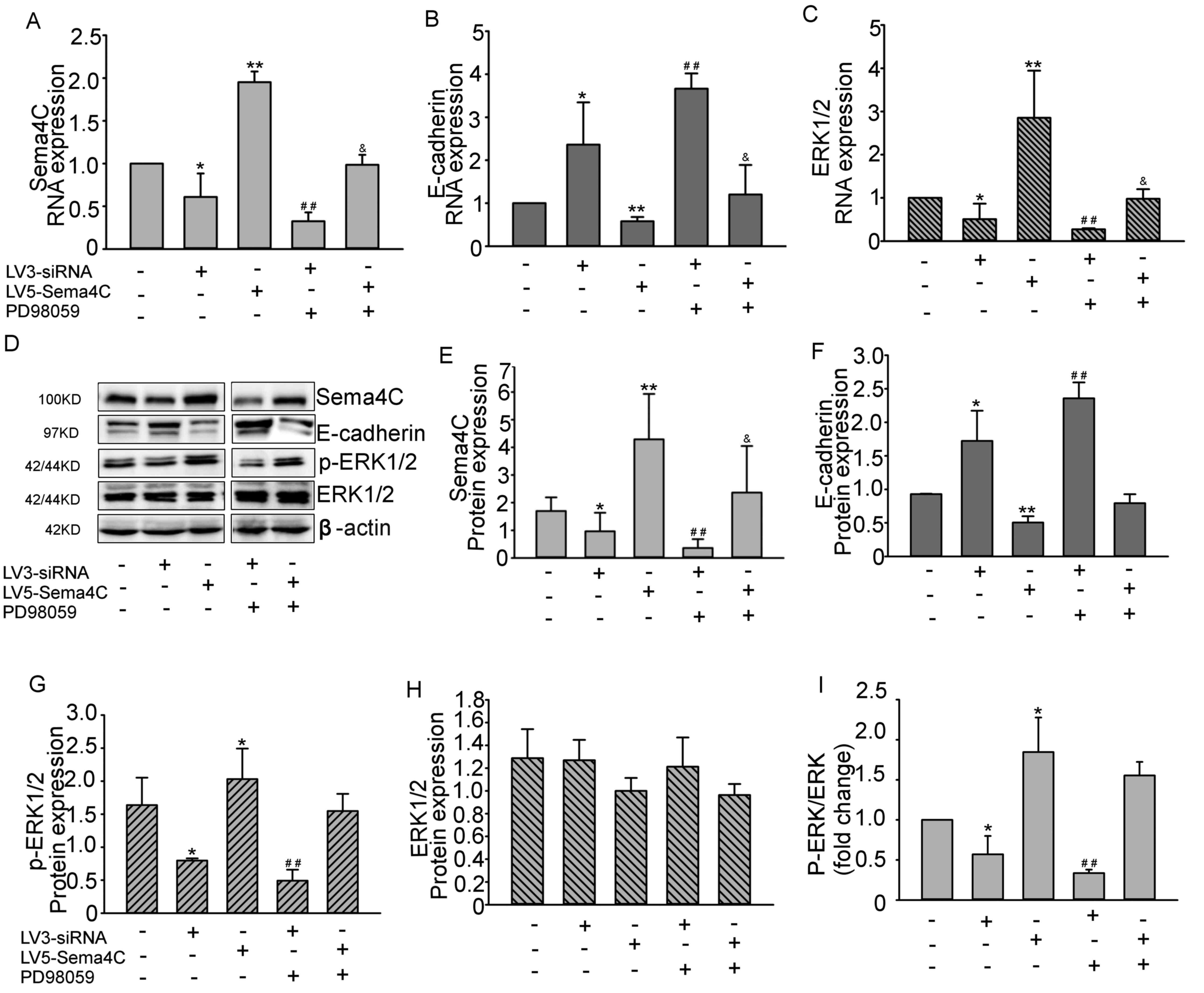

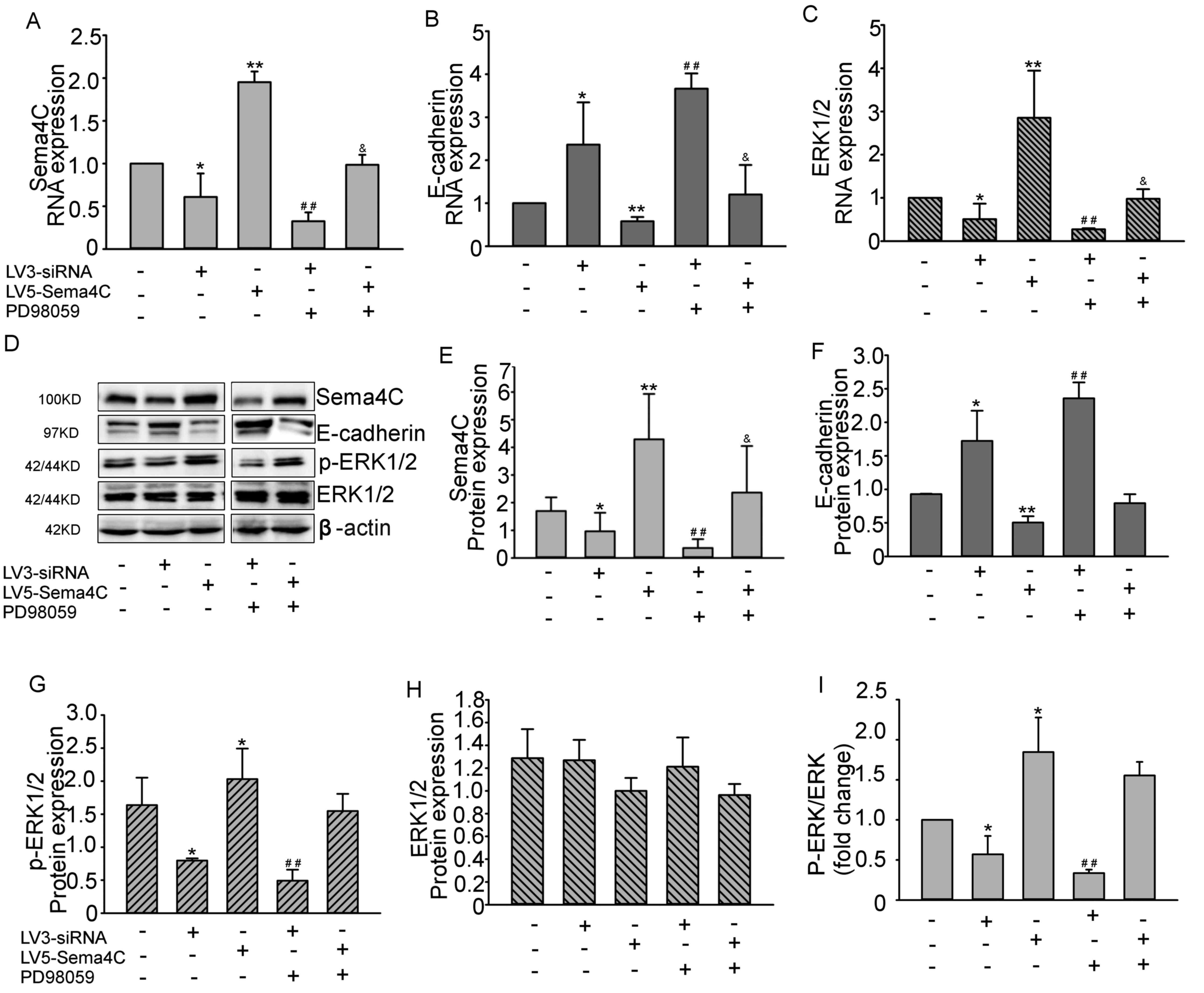

The ERK inhibitor was used to determine whether the

Sema4C-mediated regulation of E-cadherin was dependent on the

phosphorylation level of ERK1/2. It was revealed that Sema4C

silencing significantly inhibited the phosphorylation level of ERK

compared with control group (no treatment), and the introduction of

PD98059 further enhanced the upregulation of E-cadherin expression

induced by Sema4C siRNA infection, compared with the LV3-siRNA

group. However, inhibition of the phosphorylation of ERK1/2

partially reversed the downregulation of E-cadherin that was

mediated by Sema4C overexpression, compared with the LV5-Sema4C

group. The observed mRNA expression levels of Sema4C and E-cadherin

were in accordance with the protein expression levels (Fig. 5A, B

and D-F). As the phosphorylation of

ERK1/2 is indicative of the regulation of ERK1/2 at the protein

level, the mRNA expression levels of ERK1/2 were also measured

(Fig. 5C). Recovery of p-ERK1/2

expression was observed in the LV5-Sema4C + PD98059 group compared

with the LV5-Sema4C group, indicating that PD98059 can effectively

block the function of Sema4C (Fig.

5D and G). Moreover, ERK1/2

mRNA expression was significantly increased following Sema4C

overexpression, but ERK1/2 protein expression did not change

significantly, compared with the control group (Fig. 5C and H), the alteration of p-ERK/ERK ratio

showed the same alteration (Fig.

5I). Of note, the protein expression level of p-ERK1/2

exhibited the same tendency as the ERK1/2 mRNA expression. Thus,

the phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 was an effective modification

in the Sema4C signaling pathway.

| Figure 5Sema4C regulates E-cadherin

expression via the ERK pathway. mRNA expression levels of (A)

Sema4C, (B) E-cadherin and (C) total ERK1/2 in TLECs treated with

lentiviral medium only (control group), LV3-siRNA, LV5-Sema4C,

LV3-siRNA + PD98059 and LV5-Sema4C + PD98059. (D) Protein

expression levels of Sema4C, E-cadherin, p-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2

in TLECs treated with lentiviral medium only, LV3-siRNA,

LV5-Sema4C, LV3-siRNA + PD98059 and LV5-Sema4C + PD98059 detected

using western blot analysis. Semiquantitative analysis of protein

expression levels of (E) Sema4C, (F) E-cadherin, (G) p-ERK1/2 and

(H) total ERK1/2. (I) Expression of p-ERK1/2 was normalized to

total ERK1/2, and represented as fold change over the control

group. The experiments were repeated three times.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control group;

##P<0.01 vs. LV3-siRNA group;

&P<0.05 LV5-Sema4C group. Sema4C, semaphorin 4C;

p, phosphorylated; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TLECs,

tumor-associated lymphatic endothelial cells. |

Discussion

Tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis is a key

modulator of tumor metastasis, although the underlying mechanism

remains unknown. It was previously reported that the lymphatic

system actively participates in tumor metastasis (23), and that LECs serve important roles

in inducing immune tolerance (24).

The ability of LECs to promote immunosuppression may induce tumor

cell metastasis (24). A previous

study using in situ laser capture microdissection revealed

that the gene expression profile of human tumor LECs differed from

that of normal LECs, and demonstrated that Sema4C was

differentially expressed between LECs in tumor and normal tissues

(16). The present study focused on

the effect of LECs in attaining the cell invasive ability, which

was attributed, at least in part, to the higher expression of

Sema4C in tumor LECs.

There seem to be shared mechanisms between EMT and

EndMT, and E-cadherin appeared in both of them (5,25). It

has been reported that EndMT occurs in cancer and tissue fibrosis

(26), but the regulation of this

process requires further investigation. In addition, whether and

how LECs participate in EndMT to induce tumorous characteristics

during cancer development is yet to be elucidated. The biological

characteristics of LECs markedly change in tumors in vivo

compared with normal tissues (17).

Thus, in the present study, TLECs were isolated from mouse cervical

tumor tissues via flow cytometry. LYVE1 was used as the marker for

LEC separation (19), and VEGFR3 as

an identification marker (27).

It has been reported that certain factors exhibit

differences in their molecular mechanism between their membrane and

soluble forms. For example, full-length Sema3C is a tumor

angiogenesis inhibitor, whereas cleaved Sema3C is a tumor

progression promoter (28). A

previous study has revealed that biological properties differed

between the soluble and membrane forms of Sema4C (sSema4C and

mSema4C, respectively). For instance, sSema4C promoted

lymphangiogenesis, whereas mSema4C directed cell-cell contacts,

thereby providing the possibility of a new mechanism of mSema4C

functioning in LECs (16).

Therefore, the current study used lentiviral transfection for

consistent overexpression or silencing of Sema4C in TLECs.

In a previous study, Ras homolog family member A

(RhoA) was identified to be critical for Sema4C-mediated signaling

(17). One of the distinct cell

migration models, which is named amoeboid-type migration, is

characterized by a spherical or elongated cell shape and is

strongly dependent on Rho kinase activity (29). Thus, it was suggested that LECs

migrate and undergo EndMT via amoeboid-type migration, which could

be promoted by Sema4C, as indicated by the Transwell assay. A

spherical cell shape with a small number of short protrusions was

revealed in the cells after passing through the polyethylene

terephthalate membranes (29). Wu

et al (10) reported a p38

MAPK-dependent effect of Sema4C in terminal myogenic

differentiation, including ERK regulation, indicating a potential

signaling pathway of Sema4C. The present study revealed that the

promotion of the migratory ability of Sema4C-overexpressing LECs

was in part attributed to ERK activation-induced repression of

E-cadherin expression.

E-cadherin is a cell adhesive molecule that serves a

key role in cellular adhesion and migration, constitutes one of the

most important players in EndMT and can also be regulated by RhoA

(30). Previous studies reported a

novel role for E-cadherin in regulating LEC progeny in newly

synthesized lymphatic vessels (28,31).

In particular, forced disruption of E-cadherin-mediated

intercellular adhesion has been indicated to open the intercellular

junctions in LEC monolayers, as determined by a previous study

using Transwell assays (32). The

present study demonstrated that repression of E-cadherin was an

important molecular event for the promotion of the migratory

ability in Sema4C-overexpressing LECs. This finding was in line

with that of a previous study, which revealed that the

overexpression of Sema4C suppressed E-cadherin, induced vimentin

and promoted fibronectin secretion in human kidney cells (33). While the current results indicated

that E-cadherin was an important molecular target of Sema4C in

EndMT function, the downstream signaling pathways that were

impacted by the loss of E-cadherin expression and promoted the cell

migratory ability, along with the overexpression of Sema4C, are yet

to be determined.

The expression of E-cadherin is regulated by an

ERK-dependent mechanism (34,35).

Therefore, it will be interesting to determine whether the

regulation of the Sema4C-mediated E-cadherin expression and

migratory ability in LECs are activated by ERK. We focused on

protein phosphorylation, a post-translational modification (PTM)

with a prevalent role in the control of protein activity and signal

transduction) (36). p-ERK could

not be tested at the RNA level, so total ERK was tested at the RNA

level to reveal the regulation of Sema4C in the present study. The

application of an ERK inhibitor demonstrated that Sema4C regulated

E-cadherin, and this process was dependent on ERK activation. It

was revealed that the application of an ERK inhibitor could also

affect the expression levels of Sema4C, and therefore, further

studies are required to clarify whether other molecules are

involved in this pathway and the feedback loop. Wei et al

(16) revealed that Sema4C could be

expressed in TLECs and promote the proliferation and migration of

tumor cells by activating plexin-B2/MET signaling; however, the

study by Wei et al (16)

lacked molecular investigation in primary LECs. A previous study on

primary lymphatic endothelial cells has demonstrated that there are

differences between cultured cells and cells (37). Therefore, it is important to

understand the molecular characteristic of primary TLECs.

Subsequent studies should focus on additional

molecular markers of EndMT in LECs altered by Sema4C, as well as

the cell morphology alterations, such as cytoskeletal changes, to

demonstrate the role of Sema4C in regulating EndMT. Also, the

therapeutic effect of lentivirus-mediated inhibition should be

examined.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

Sema4C was expressed in TLECs via co-localization with LVYE1, and

identified that upregulation of Sema4C was an important molecular

mechanism that contributed to the induction of tumor-like

characteristics by suppressing E-cadherin expression.

Mechanistically, the process involved the activation of the ERK

pathway, which functioned upstream of E-cadherin and downstream of

Sema4C. Studies on TLECs are limited, and therefore, it will be

important to determine whether enhanced ERK activation during the

upregulation of Sema4C, as observed in TLECs, can induce tumor

lymphatic metastasis, which in turn could be targeted using

pharmacological approaches.

Supplementary Material

Lentiviral packaging systems. (A)

Four-plasmid system for LV5 lentivirus. (B) Four-plasmid system for

LV3 lentivirus.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Qingliang Wang

(Department of Medical Affairs, Qilu Hospital, Cheeloo College of

Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China) for his assistance

with the statistical analysis of the present study.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81502238

and 81602286), the Department of Medical and Health Science

Technology of Shandong Province (grant no. 2016w0345), the

Department of Science Technology of Jinan City (grant no.

201705051), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no.

2019T120594) and Natural Science Foundation General Project of

Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2020MH230).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

HW designed the experiments and wrote the paper. JP

and XL conceived the experiments, performed the molecular

experiments and analyzed the data. CL established the mouse model,

performed the histological examination of tumor and separated the

cells. MG performed the statistical analysis. HW and JP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All the experiments were conducted in accordance

with the National Institute of Health Guide of the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals. All the animal experimental protocols were

approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shandong

University for Animal Ethics [approval no. KYLL-2015(KS)-079]. The

use of primary LECs was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics

Committee of Shandong University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Frumovitz M: Sentinel lymph node biopsy

for cervical cancer patients-what's it gonna take? Gynecol Oncol.

144:3–4. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li H, Wu X and Cheng X: Advances in

diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. J Gynecol

Oncol. 27(e43)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hoshino A and Lyden D: Metastasis:

Lymphatic detours for cancer. Nature. 546:609–610. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lucas ED and Tamburini BAJ: Lymph node

lymphatic endothelial cell expansion and contraction and the

programming of the immune response. Front Immunol.

10(36)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Saito A: EMT and EndMT: Regulated in

similar ways? J Biochem. 153:493–495. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kourtidis A, Lu R, Pence LJ and

Anastasiadis PZ: A central role for cadherin signaling in cancer.

Exp Cell Res. 358:78–85. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang SH, Chang JS, Hsiao JR, Yen YC, Jiang

SS, Liu SH, Chen YL, Shen YY, Chang JY and Chen YW: Tumour

cell-derived WNT5B modulates in vitro lymphangiogenesis via

induction of partial endothelial-mesenchymal transition of

lymphatic endothelial cells. Oncogene. 36:1503–1515.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lee HR, Li F, Choi UY, Yu HR, Aldrovandi

GM, Feng P, Gao SJ, Hong YK and Jung JU: Deregulation of HDAC5 by

viral interferon regulatory factor 3 plays an essential role in

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced lymphangiogenesis.

mBio. 9:e02217–17. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Jiang L, Hao C, Li Z, Zhang P, Wang S,

Yang S, Wei F and Zhang J: miR-449a induces EndMT, promotes the

development of atherosclerosis by targeting the interaction between

AdipoR2 and E-cadherin in Lipid Rafts. Biomed Pharmacother.

109:2293–2304. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wu H, Wang X, Liu S, Wu Y, Zhao T, Chen X,

Zhu L, Wu Y, Ding X, Peng X, et al: Sema4C participates in myogenic

differentiation in vivo and in vitro through the p38 MAPK pathway.

Eur J Cell Biol. 86:331–344. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Elder AM, Tamburini BAJ, Crump LS, Black

SA, Wessells VM, Schedin PJ, Borges VF and Lyons TR: Semaphorin 7A

promotes macrophage-mediated lymphatic remodeling during postpartum

mammary gland involution and in breast cancer. Cancer Res.

78:6473–6485. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Acker DWM, Wong I, Kang M and Paradis S:

Semaphorin 4D promotes inhibitory synapse formation and suppresses

seizures in vivo. Epilepsia. 59:1257–1268. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sakurai A, Doci CL and Gutkind JS:

Semaphorin signaling in angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis and cancer.

Cell Res. 22:23–32. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Doçi CL, Mikelis CM, Lionakis MS, Molinolo

AA and Gutkind JS: Genetic identification of SEMA3F as an

antilymphangiogenic metastasis suppressor gene in head and neck

squamous carcinoma. Cancer Res. 75:2937–2948. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nasarre P, Gemmill RM and Drabkin HA: The

emerging role of class-3 semaphorins and their neuropilin receptors

in oncology. Onco Targets Ther. 7:1663–1687. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wei JC, Yang J, Liu D, Wu MF, Qiao L, Wang

JN, Ma QF, Zeng Z, Ye SM, Guo ES, et al: Tumor-associated lymphatic

endothelial cells promote lymphatic metastasis by highly expressing

and secreting SEMA4C. Clin Cancer Res. 23:214–224. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Albini A, Mirisola V and Pfeffer U:

Metastasis signatures: Genes regulating tumor-microenvironment

interactions predict metastatic behavior. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

27:75–83. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Olmeda D, Cerezo-Wallis D,

Riveiro-Falkenbach E, Pennacchi PC, Contreras-Alcalde M, Ibarz N,

Cifdaloz M, Catena X, Calvo TG, Cañón E, et al: Whole-body imaging

of lymphovascular niches identifies pre-metastatic roles of

midkine. Nature. 546:676–680. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Young YK, Bolt AM, Ahn R and Mann KK:

Analyzing the tumor microenvironment by flow cytometry. Methods Mol

Biol. 1458:95–110. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lukacs-Kornek V: The role of lymphatic

endothelial cells in liver injury and tumor development. Front

Immunol. 7(548)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Faustino-Rocha A, Oliveira PA,

Pinho-Oliveira J, Teixeira-Guedes C, Soares-Maia R, da Costa RG,

Colaço B, Pires MJ, Colaço J, Ferreira R and Ginja M: Estimation of

rat mammary tumor volume using caliper and ultrasonography

measurements. Lab Anim (NY). 42:217–224. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Humbert M, Hugues S and Dubrot J: Shaping

of peripheral T cell responses by lymphatic endothelial cells.

Front Immunol. 7(684)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ji RC: Lymph nodes and cancer metastasis:

New perspectives on the role of intranodal lymphatic sinuses. Int J

Mol Sci. 18(51)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Potenta S, Zeisberg E and Kalluri R: The

role of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer

progression. Br J Cancer. 99:1375–1379. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cho JG, Lee A, Chang W, Lee MS and Kim J:

Endothelial to mesenchymal transition represents a key link in the

interaction between inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Front

Immunol. 9(294)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Harris AR, Perez MJ and Munson JM:

Docetaxel facilitates lymphatic-tumor crosstalk to promote

lymphangiogenesis and cancer progression. BMC Cancer.

18(718)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mumblat Y, Kessler O, Ilan N and Neufeld

G: Full-length semaphorin-3C Is an inhibitor of tumor

lymphangiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 75:2177–2186.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lawson CD and Ridley AJ: Rho GTPase

signaling complexes in cell migration and invasion. J Cell Biol.

217:447–457. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lee G, Kim HJ and Kim HM: RhoA-JNK

regulates the E-cadherin junctions of human gingival epithelial

cells. J Dent Res. 95:284–291. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Connor AL, Kelley PM and Tempero RM:

Lymphatic endothelial lineage assemblage during corneal

lymphangiogenesis. Lab Invest. 96:270–282. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hou WH, Liu IH, Tsai CC, Johnson FE, Huang

SS and Huang JS: CRSBP-1/LYVE-1 ligands disrupt lymphatic

intercellular adhesion by inducing tyrosine phosphorylation and

internalization of VE-cadherin. J Cell Sci. 124:1231–1244.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhou QD, Ning Y, Zeng R, Chen L, Kou P, Xu

CO, Pei GC, Han M and Xu G: Erbin interacts with Sema4C and

inhibits Sema4C-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HK2

cells. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 33:672–679.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Marchese V, Juarez J, Patel P and

Hutter-Lobo D: Density-dependent ERK MAPK expression regulates

MMP-9 and influences growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 456:115–122.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Tang FY, Chiang EP, Chung JG, Lee HZ and

Hsu CY: S-allylcysteine modulates the expression of E-cadherin and

inhibits the malignant progression of human oral cancer. J Nutr

Biochem. 20:1013–1020. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kawata K, Yugi K, Hatano A, Kokaji T,

Tomizawa Y, Fujii M, Uda S, Kubota H, Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI and

Kuroda S: Reconstruction of global regulatory network from

signaling to cellular functions using phosphoproteomic data. Genes

Cells. 24:82–93. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wick N, Saharinen P, Saharinen J,

Gurnhofer E, Steiner CW, Raab I, Stokic D, Giovanoli P, Buchsbaum

S, Burchard A, et al: Transcriptomal comparison of human dermal

lymphatic endothelial cells ex vivo and in vitro. Physiol Genomics.

28:179–192. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|