Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is characterized

by myocardial necrosis caused by acute and persistent ischemia and

hypoxia of cardiac cells (1).

Clinically, AMI presents as sharp and persistent substernal pain

that cannot be fully relieved by resting or nitrate medications,

and is accompanied by elevated levels of serum myocardial enzymes,

including creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), as well

as abnormal progression on an electrocardiogram (2-4).

AMI can occur at the same time as arrhythmias, shock or heart

failure, and is often life threatening. This disease is most common

in North American and European countries, where ~1.5 million new

cases of AMI are reported in the United States annually (5,6). In

China, the incidence of AMI has continued to increase in the last

decade, with ≥500,000 new cases annually and ~2 million patients

currently diagnosed (7).

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is often the result of

different types of coronary artery disease, including myocardial

infarction, ischemic cardiomyopathy and sudden coronary death

(8). Reperfusion is a standard

therapy for acute cases of coronary artery diseases, including MI,

and is also an inevitable inducer of I/R injury of coronary

microvessels and myocardium (9-11).

Phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) is one of the 11

members of the PDE enzyme family that are known for their exclusive

ability to decompose cyclic nucleotides, and it can regulate

several biological processes (12). A recent microarray study identified

PDE4B as a metabolism-related gene that was strongly associated

with the onset and recurrence of AMI (13). Previous studies have reported that

activation of PDE4B induced cognitive impairment and neuronal

apoptosis, and aggravated neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in

the central nervous system (14,15).

Jun dimerization protein 2 (JDP2) is a bZip-type

transcription factor that belongs to the activator protein-1 (AP-1)

family (16). JDP2 upregulation in

mice has been reported to have a direct association with impaired

cardiac function manifested as cardiomyocyte apoptosis, cardiac

hypertrophy, fibrosis and inflammation (17).

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate

how PDE4B expression affected myocardial hypoxia/reoxygenation

(H/R) injury, and to determine the function of JDP2 in the

process.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics tools

JASPAR database (jaspar.genereg.net) which is a regularly maintained

open-access database storing manually curated transcription factors

(TF) binding profiles as position frequency matrices (PFMs) was

applied to predict the interaction between the transcription factor

JDP2 and PDE4B promoter.

Cell culture and treatment

H9c2 rat embryo heart-derived cardiomyocytes

(American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in low-glucose

DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37˚C. To create a hypoxic

condition, H9c2 cells were cultured at 37˚C for 6 h in serum-free

and glucose-free DMEM in a tri-gas incubator with 94%

N2, 5% CO2 and 1% O2.

Subsequently, cells were re-oxygenated for 2 h in DMEM supplemented

with 10% FBS in 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37˚C, as

previously described (18). Cells

incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 incubator

at 37˚C for 20 h were used as a control throughout the

experiments.

Cell transfection

Short hairpin (sh)RNA plasmids specific for PDE4B

which were ligated into the plasmid of U6/GFP/Neo [sh-PDE4B-1

forward,

5'-CCGGTACTCCTTCTCTGTGAAATTTCTCGAGAAATTTCACAGAGAAGGAGTATTTTTG-3'

and reverse,

5'-AATTCAAAAATACTCCTTCTCTGTGAAATTTCTCGAGAAATTTCACAGAGAAGGAGTA-3';

sh-PDE4B-2 forward,

5'-CCGGTCCATCTACAGTCTGAGATTACTCGAGTAATCTCAGACTGTAGATGGATTTTTG-3'

and reverse,

5'-AATTCAAAAATCCATCTACAGTCTGAGATTACTCGAGTAATCTCAGACTGTAGATGGA-3',

shRNA with empty vectors which was regarded as negative control

(NC), pcDNA3.1(+) JDP2 overexpression vector (Oe-JDP2) and Oe-NC

were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. H9c2 cells

(4x105 cells/well) were transfected with 50 nM

sh-PDE4B-1/2, sh-NC, Oe-JDP2 or Oe-NC using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After

incubation at 37˚C for 48 h, cells were harvested for subsequent

experiments.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from H9c2 cells using the

RNAeasy™ Viral RNA Isolation kit with Spin Column

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Total RNA was reverse

transcribed into cDNA using the Revert Aid™ cDNA

Synthesis kit (Takara Biotechnology co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, qPCR was performed using

BeyoFast™ Probe qPCR mix (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 95˚C for 30 sec, followed by denaturation at

95˚C for 10 sec and annealing at 55˚C for 30 sec for 40 cycles. The

following primers were used for qPCR: PDE4B forward,

5'-ACGGTGGCTCATACATGCT-3' and reverse, 5'-GTACCAGTCCCGACGAAGAG-3';

JDP2 forward, 5'-CCCAGGGACCTCGAGCTTT-3' and reverse,

5'-GGTCTTCAGCTCTGCGTTCA-3'; and GADPH forward,

5'-GAATGGGCAGCCGTTAGGAA-3' and reverse, 5'-AAAAGCATCACCCGGAGGAG-3'.

Relative expression levels were calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (19) and

normalized to the internal reference gene GAPDH.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from H9c2 cells using

RIPA lysis buffer (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and

quantified using a BCA kit (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). Proteins (20 µg per lane) were separated via 10%

SDS-PAGE (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and transferred onto

PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated at 4˚C overnight with

primary antibodies targeted against: PDE4B (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab14628; Abcam), Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab196495; Abcam), Bax

(1:1,000; cat. no. ab32503; Abcam), cleaved-caspase3 (1:1,000; cat.

no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), cleaved-caspase9

(1:1,000; cat. no. 10380-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), JDP2

(1:1,000; cat. no. orb336272; Biorbyt Ltd.) and GAPDH (1:10,000;

cat. no. ab181602; Abcam). Following the primary incubation,

membranes were incubated with a HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG

(H+L) secondary antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) at 37˚C for 2 h. Protein bands were

visualized using ECL reagents (PerkinElmer, Inc.) and analyzed by

Image J software (version 1.48v; National Institutes of Health).

GAPDH was used as the loading control.

Cell viability and cytotoxicity

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) assay was performed was to

assess cell viability. Briefly, H9c2 cells (2x103

cells/100 µl/well) were incubated with 10 µl/well CCK-8 solution in

a 96-well plate for 2 h. Subsequently, optical density was measured

at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

The LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) was used to detect H/R-induced cytotoxicity

according to the manufacturer's instructions. LDH activity was

measured at a wavelength of 490 nm using a microplate reader

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Detection of oxidative stress

levels

The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide

dismutase (SOD) in H9c2 cells were detected using MDA (A003-1-2)

and SOD (A001-3-2) assay kits (both Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute), respectively. The glutathione (GSH) to

glutathione oxidized (GSSG) ratio was measured using the GSH/GSSG

Ratio Assay kit (cat. no. KA6046; Abnova). Briefly, the cell

precipitate was collected via centrifugation at 1,600 x g for 10

min at 4˚C and freeze-thawed twice with liquid nitrogen and 37˚C

water baths prior to centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 10 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, working solution and NADPH solution from

the kits were prepared and added successively into the supernatant.

Following incubation, the absorbance at 412 nm was determined using

a microplate reader (BioTek instruments, inc.).

Measurement of apoptotic rate and

apoptosis-related proteins

H9c2 cell apoptosis was detected using the TUNEL

Apoptosis Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). After

washing with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4˚C

for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.3% PBS in Triton X-100 at room

temperature for 30 min and then incubated with 0.3%

H2O2 in PBS on ice for 2 min prior to biotin

labeling. Cells were incubated with TUNEL detection solution at

37˚C for 60 min in the dark and stained with 10 µg/ml DAPI

(Shanghai Haoyang Bio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37˚C for 2-3 min. In

total, three fields of view were selected at random and the images

were captured using a fluorescence microscope (magnification, x200;

Olympus Corporation). Apoptosis-related protein expression levels

were detected via western blotting according to the aforementioned

protocol.

Verification of interaction between

JDP2 and PDE4B

For the dual luciferase reporter assay, H9c2 cells

(5x105 cells/well) were seeded (1x104

cells/well) into 96-well plates. Subsequently, H9c2 cells were

co-transfected with PDE4B-WT and PDE4B-MUT, Oe-JDP2 or Oe-NC (0.5

µg) and Renilla luciferase reporter vector (Promega

Corporation) using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h at 37˚C. At 48 h

post-transfection, firefly luciferase activities was measured using

a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega Corporation) and

normalized to Renilla luciferase activities.

For the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay,

ultrasound-treated samples were centrifuged at 12,000-14,000 x g

for 5 min at 4˚C. A total of 300 µl SDS lysis buffer (Active Motif,

Inc.) was then used to lyse the cells, which were subsequently

sonicated at 150 Hz and sheared with four sets of 10 sec pulses on

wet ice using a high intensity ultrasonic processor. ChIP Dilution

Buffer containing 1 mM PMSF was prepared using the ChIP Assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and added to part of the

samples to serve as the input. A total of 40 µl protein A/G agarose

beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was added to the rest of the

samples. Following centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C,

supernatant (100 µl) was incubated with 5 µg anti-IgG (cat. no.

sc-2025; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or anti-JDP2 (cat. no.

sc-517133; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) primary antibodies and

protein A/G agarose at 4˚C overnight. The precipitated chromatin

was purified by phenol/chloroform/isoamyl extraction and analyzed

via RT-qPCR according to the aforementioned protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism (version 8; GraphPad Software, Inc.). All experiments were

performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from

at least three independent experiments. Comparisons between two

groups were analyzed using an unpaired Student's t-test, whereas

comparisons among multiple groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

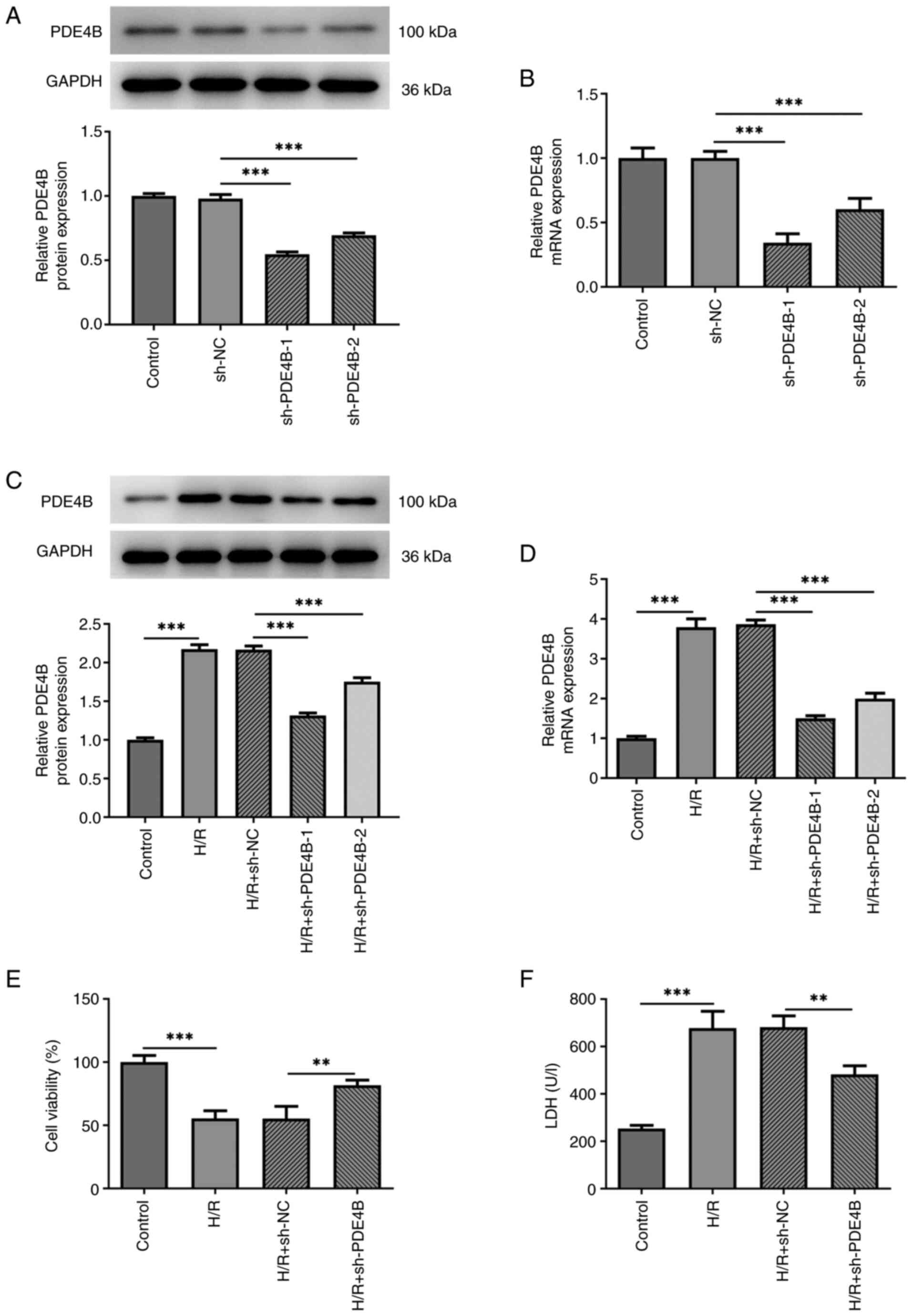

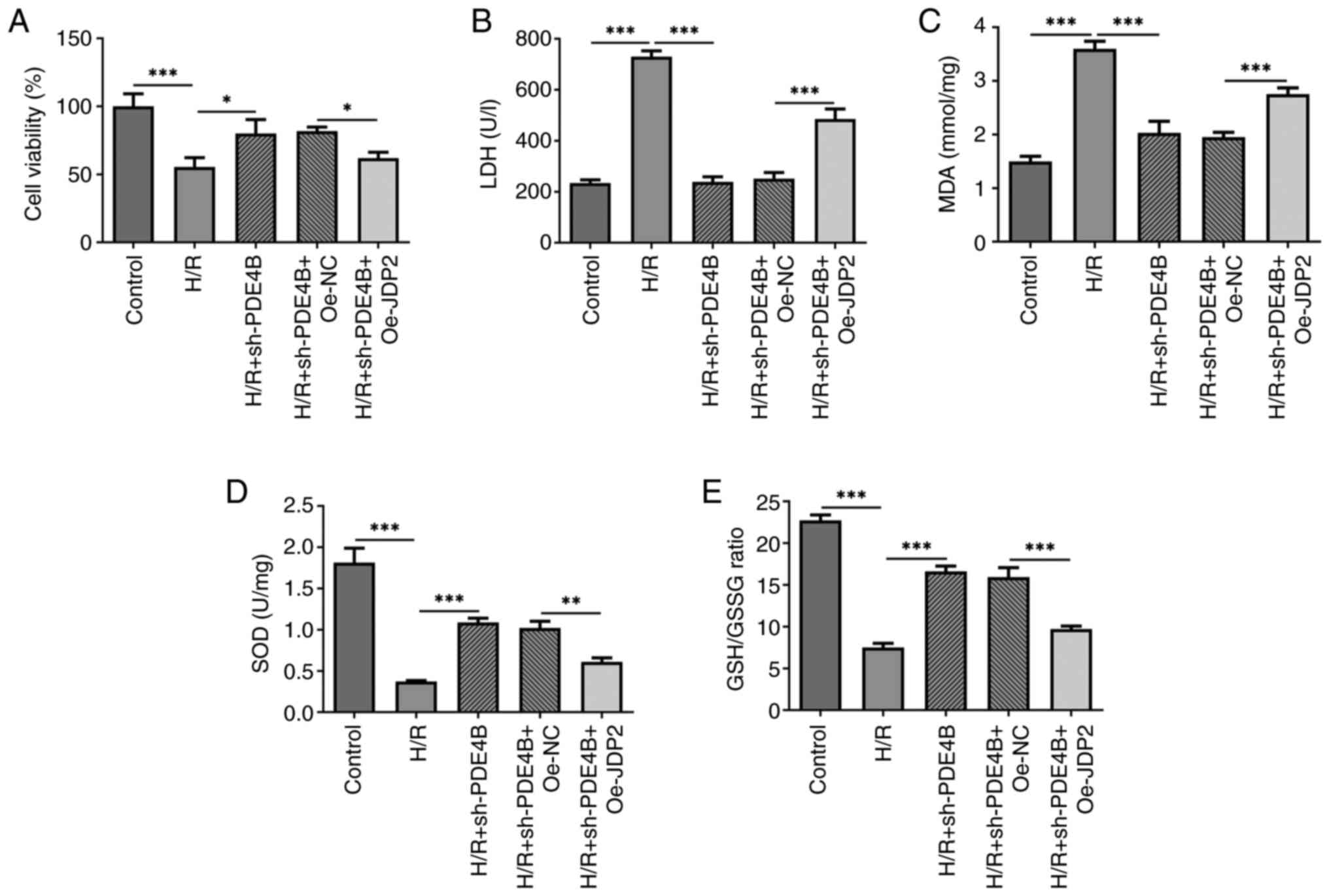

Effect of PDE4B knockdown on H9c2 cell

viability and cytotoxicity following H/R

Firstly, H9c2 cells were transfected with

sh-PDE4B-1/2 or sh-NC, and then PDE4B expression was detected via

RT-qPCR and western blotting (Fig.

1A and B). sh-PDE4B-1 and

sh-PDE4B-2 significantly decreased PDE4B expression levels compared

with sh-NC. Moreover, PDE4B was expressed at significantly higher

levels in H9c2 cells exposed to H/R compared with the control group

(Fig. 1C and D). In addition, transfection with

sh-PDE4B-1/2 significantly decreased the expression of PDE4B under

H/R conditions, with sh-PDE4B-1 displaying a higher knockdown

effect compared with sh-PDE4B-2 (Fig.

1C and D). Thus, sh-PDE4B-1

was selected for use in subsequent experiments. Compared with the

control group, cells exposed to H/R displayed a significant decline

in viability, whereas PDE4B interference significantly increased

cell viability under H/R conditions (Fig. 1E). Cytotoxicity detection in H9c2

cells demonstrated that PDE4B knockdown significantly decreased

H/R-induced upregulated LDH levels (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results

suggested that PDE4B knockdown prevented decreases in cell

viability and alleviated the cytotoxicity of H/R-stimulated H9c2

cells.

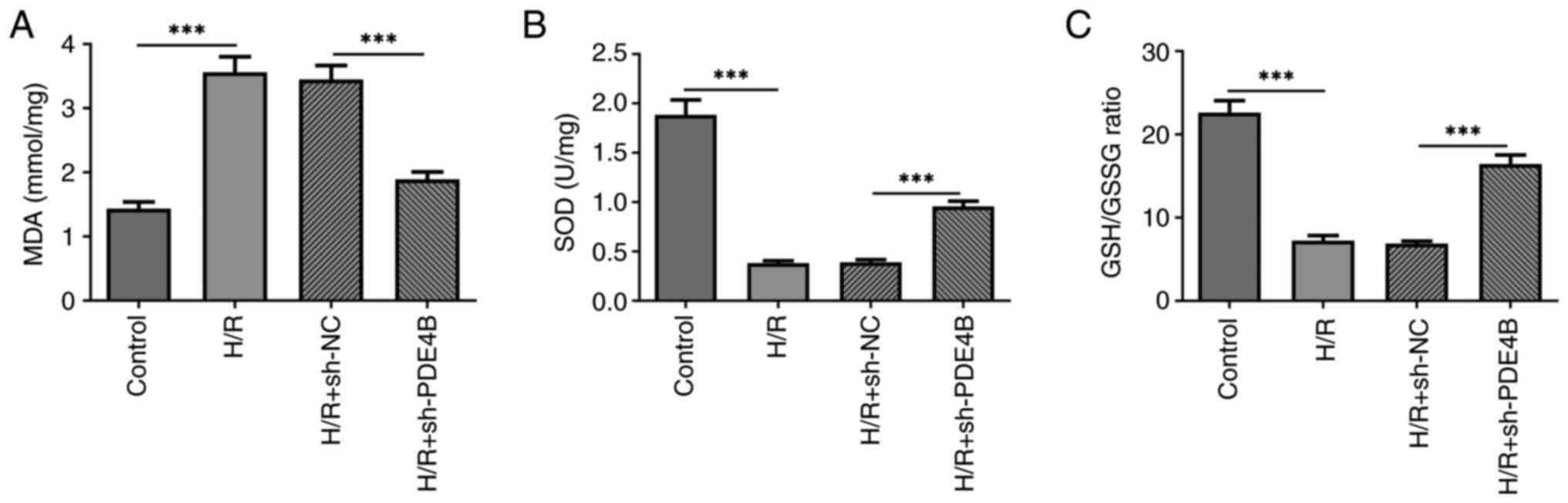

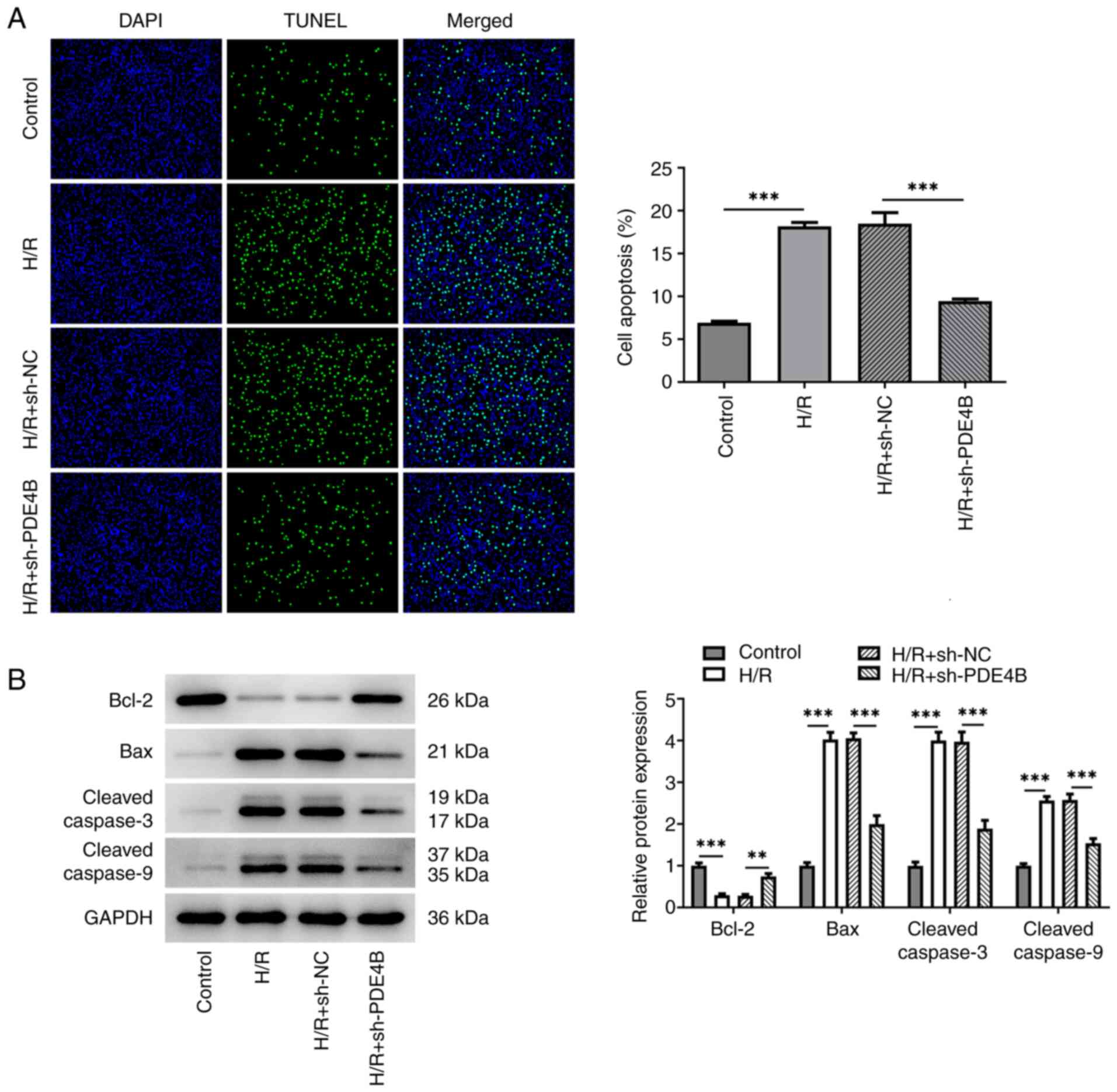

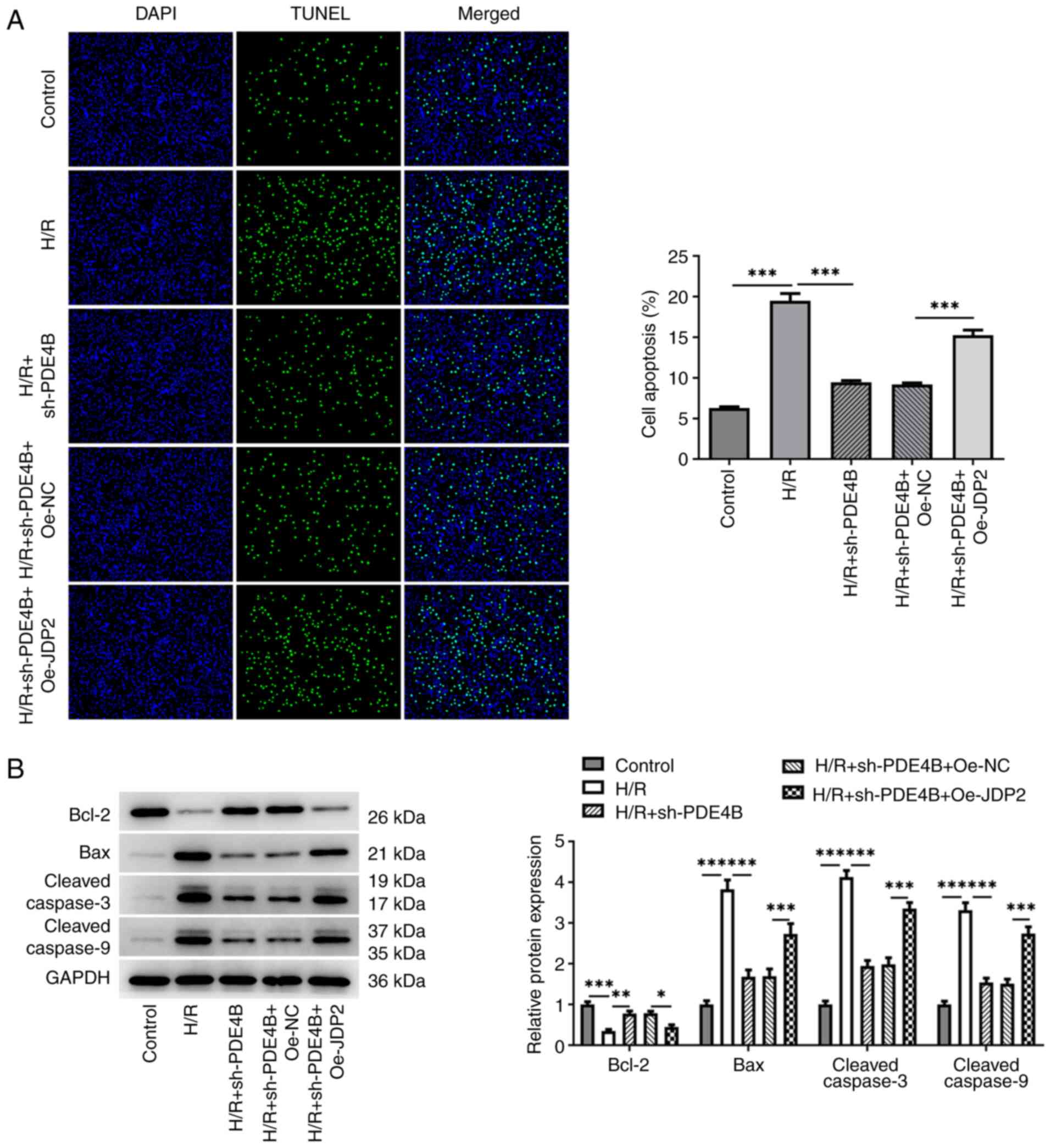

Effect of PDE4B knockdown on

H/R-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in H9c2 cells

The present study assessed the degrees of oxidative

stress and apoptosis of H9c2 cells following H/R, before and after

transfection with sh-PDE4B. The results demonstrated that the

concentration of MDA was significantly higher (Fig. 2A), whereas the concentration of SOD

and the GSH/GSSG ratio were significantly lower (Fig. 2B and C) in cells exposed to H/R compared with

those in the control group. However, PDE4B knockdown significantly

decreased the concentration of MDA, and significantly elevated the

concentration of SOD and the ratio of GSH to GSSG under H/R

conditions. In addition, the number of TUNEL+ cells was

significantly increased in the H/R group compared with the control

group, which was significantly reversed following PDE4B knockdown

(Fig. 3A). Consistently, in

H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression was

significantly decreased, whereas proapoptotic Bax expression was

significantly increased, and the expression levels of

cleaved-caspase3 and cleaved-caspase9 were significantly increased

compared with those in the control group. Notably, these effects

were significantly reversed following PDE4B knockdown (Fig. 3B). Collectively, these results

suggested that PDE4B knockdown ameliorated H/R-induced oxidative

stress and apoptosis in H9c2 cells.

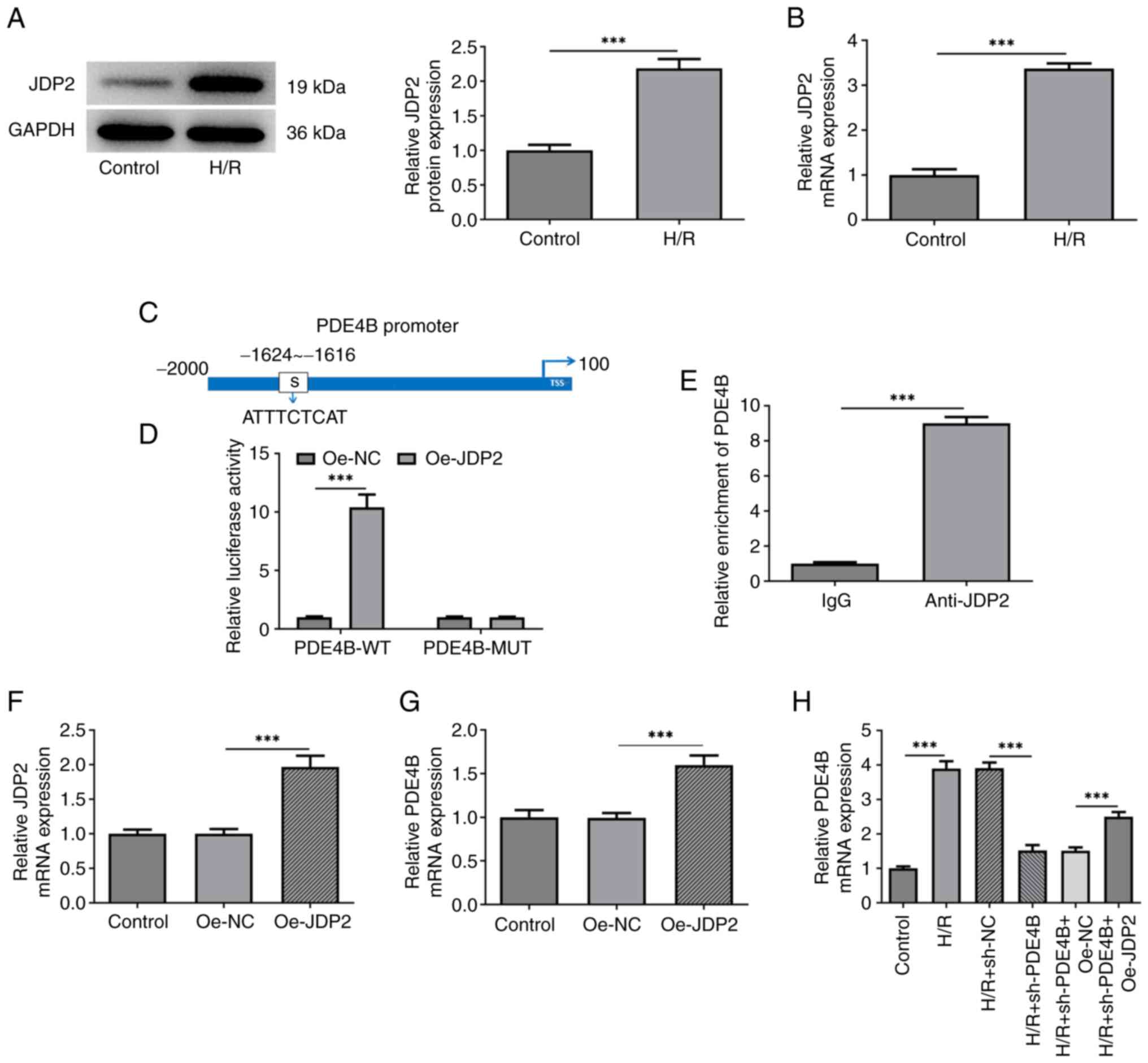

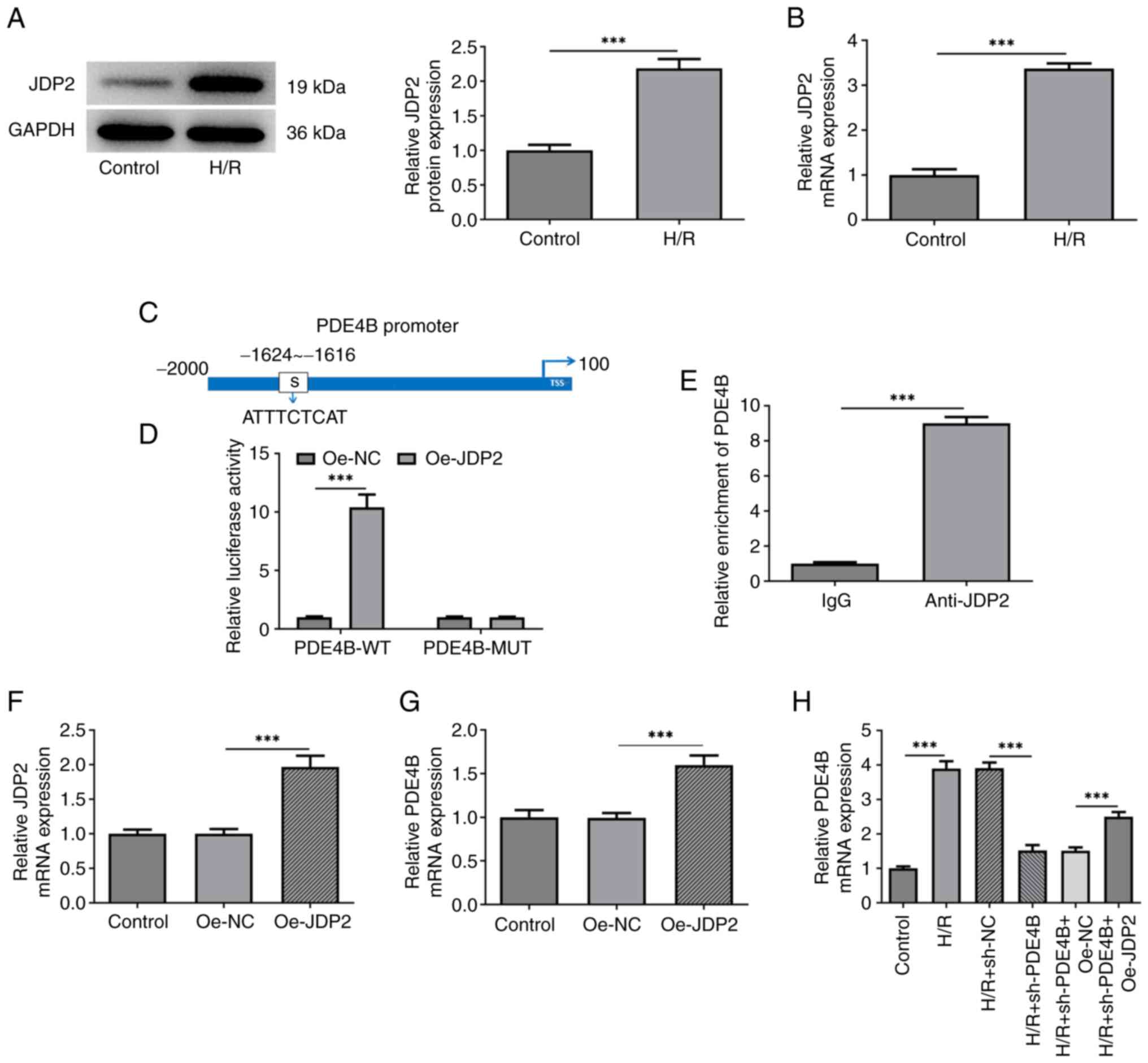

Binding interaction between PDE4B and

transcription factor JDP2

RT-qPCR and western blotting confirmed that JDP2

expression was upregulated in H9c2 cells following H/R (Fig. 4A and B). JASPAR was used to predict the binding

sites between JDP2 and PDE4B (Fig.

4C). This interaction was confirmed by performing dual

luciferase reporter and ChIP assays, which demonstrated

significantly upregulated luciferase activities in cells

co-transfected with PDE4B-wild-type (WT) and Oe-JDP2 compared with

those co-transfected with PDE4B-WT and Oe-NC. No apparent changes

were observed in the luciferase activity of PDE4B-MUT after

co-transfection of Oe-NC or Oe-JDP2 (Fig. 4D). Compared with cells treated with

IgG, significantly increased PDE4B expression was observed in cells

treated with anti-JDP2 (Fig. 4E).

The RT-qPCR results confirmed the successful transfection of

Oe-JDP2 in H9c2 cells (Fig. 4F).

mRNA level of PDE4B was also enhanced after transfection of Oe-JDP2

(Fig. 4G). Additionally, the

results demonstrated that JDP2 overexpression significantly

increased PDE4B expression in H9c2 cells exposed to H/R (Fig. 4H). Taken together, these results

suggested that the transcription factor JDP2 activated PDE4B in

H9c2 cells exposed to H/R.

| Figure 4JDP2 expression is upregulated in

H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells, which activates PDE4B expression. (A)

Western blotting and (B) RT-qPCR were performed to detect JDP2

expression in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells. (C) JASPAR database was

used to predict the binding sites between JDP2 and PDE4B promoter

regions. (D) Dual luciferase reporter assays were performed to

detect relative luciferase activities in cells co-transfected with

PDE4B-WT or MUT and Oe-NC or Oe-JDP2. (E) Chromatin

immunoprecipitation assays were performed to detect PDE4B

enrichment in IgG and anti-JDP2 groups. (F) RT-qPCR was performed

to assess the transfection efficiency of Oe-JDP2 in H9c2 cells. (G)

RT-qPCR was performed to detect PDE4B mRNA expression levels after

JDP2 overexpression in H9c2 cells. (H) RT-qPCR was performed to

detect PDE4B mRNA expression in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells following

transfection with sh-PDE4B or co-transfection with Oe-JDP2.

***P<0.001. JDP2, c-Jun dimerization protein 2; H/R,

hypoxia/reoxygenation; PDE4B, phosphodiesterase 4B; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; WT, wild-type; MUT, mutant;

Oe, overexpression; NC, negative control; sh, short hairpin

RNA. |

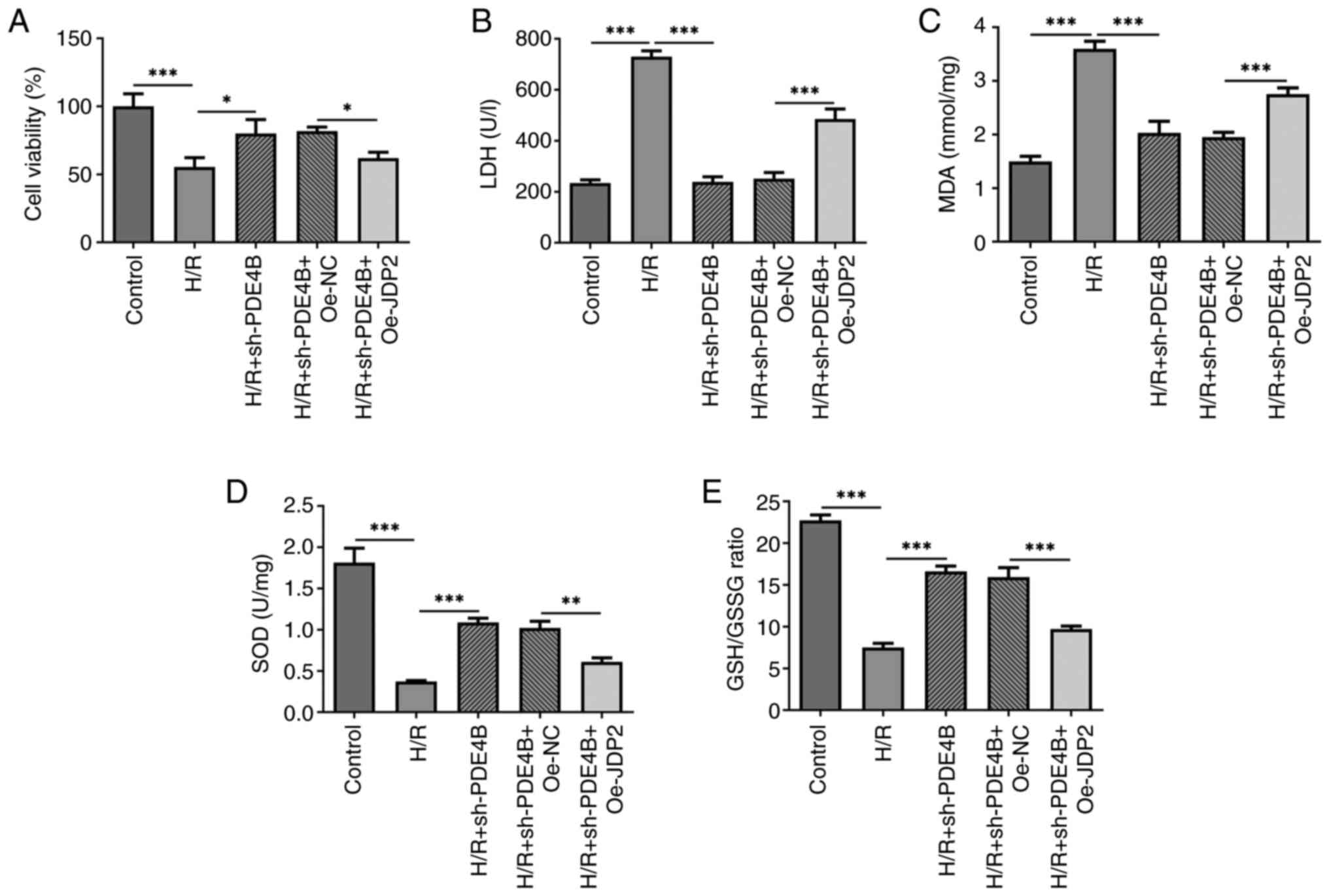

Role of JDP2 in PDE4B

knockdown-mediated alleviation of H9c2 cell injury following

H/R

The present study investigated how the interaction

between JDP2 and PDE4B affected H/R-induced H9c2 cell injury.

Analysis of cell viability and cytotoxicity under H/R conditions

demonstrated a significant decrease in H9c2 cell viability

(Fig. 5A) and a significant

increase in the level of LDH (Fig.

5B) following co-transfection with sh-PDE4B and Oe-JDP2

compared with that observed in sh-PDE4B + Oe-NC group. Therefore,

the results indicated that JDP2 overexpression reversed the effect

of PDE4B knockdown on H/R-induced H9c2 cell injury.

| Figure 5JDP2 overexpression partly reverses

the effects of PDE4B knockdown on cell viability, cytotoxicity and

oxidative stress in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells. Analysis of (A) cell

viability, (B) cytotoxicity, (C) MDA concentration, (D) SOD

concentration and (E) GSH/GSSG ratio in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells

following transfection with sh-PDE4B or co-transfection with

Oe-JDP2. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. JDP2, c-Jun dimerization protein 2;

PDE4B, phosphodiesterase 4B; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG,

glutathione oxidized; sh, short hairpin RNA; Oe, overexpression;

NC, negative control; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. |

Role of JDP2 in PDE4B

interference-alleviated oxidative stress and apoptosis of H9c2

cells following H/R

The results demonstrated significantly increased MDA

concentration (Fig. 5C), and

significantly decreased SOD concentration (Fig. 5D) and GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 5E) in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cells

co-transfected with sh-PDE4B and Oe-JDP2 compared with those

co-transfected with sh-PDE4B and Oe-NC. Notably, JDP overexpression

significantly increased the number of TUNEL+ cells

(Fig. 6A), decreased Bcl-2

expression, increased Bax expression, and increased the expression

levels of cleaved-caspase3 and cleaved-caspase9 following H/R in

PDE4B-knockdown H9c2 cells (Fig.

6B). Collectively, these results suggested that JDP2

overexpression reversed the ameliorative effect of PDE4B knockdown

on H/R-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in H9c2 cells.

Discussion

AMI is a serious consequence of atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease and coronary artery disease. Rapid

development of cardiac interventional therapy and bypass surgery

has improved the treatment of coronary heart disease (20). However, several issues associated

with AMI treatment remain, particularly cardiomyocyte necrosis or

apoptosis from prolonged myocardial ischemia (21,22).

Myocardial I/R injury is the primary pathological manifestation of

coronary artery disease, which continues to increase the global

morbidity and mortality of AMI despite therapeutic intervention

(23). Cytotoxic oxygen species

production, inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and interplay

between apoptosis and autophagy are critical participants in

I/R-induced cardiomyocyte injury (24-26).

Previous studies have reported the roles of certain

genes in the process of AMI (27-29).

In the present study, a high expression level of PDE4B expression

was observed in H9c2 cardiomyocytes exposed to H/R, indicating the

involvement of PDE4B in H/R-induced AMI. Aberrantly high PDE4B

expression has been identified as a contributing factor in the

pathogenesis of several diseases, including colorectal cancer,

neurological conditions and injury, allergy and heart failure

(30-33).

In the setting of oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced HT22 mouse

hippocampal neuronal cell injury, PDE4B overexpression promotes

endoplasmic reticulum stress and the release of reactive oxygen

species (34). Furthermore, PDE4B

knockdown in primary microglia increases LC-3II expression and

decreases inflammasome activity (35). The results of the present study

demonstrated that PDE4B knockdown increased H9c2 viability and

decreased cytotoxicity under H/R conditions. According to a study

on acute lung injury, PDE4B knockout could effectively inhibit

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation of the NF-κB-related

inflammatory response and generation of reactive oxygen species in

multiple pulmonary cell lines, including epithelial cells (A549),

microvascular endothelial cells (pulmonary microvascular

endothelial cells) and vascular smooth muscle cells (36). PDE4B has also been reported to be

upregulated in patients with acute kidney injury, whereas treatment

with rutaecarpine derivative compound-6c exerts an anti-oxidative

effect by downregulating PDE4B to protect kidney tubular epithelial

cells against oxidative stress and programmed cell death (37). The results of the present study

demonstrated that PDE4B knockdown alleviated H/R-induced oxidative

stress and apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes, which was consistent

with previous findings.

In the present study, the JASPAR database was used

to predict the binding sites between PDE4B promoter and JDP2, a

transcription factor that is differentially expressed in patients

with MI (38). In view of the

critical regulatory role of JDP2 in impaired cardiac function

(17), the present study also

confirmed that JDP2 was upregulated in H9c2 cells exposed to H/R,

and verified the interaction between JDP2 and the PDE4B promoter

region. In addition, JDP2 expression is activated by hypoxia in a

murine model of MI and is regulated by testis-specific transcript,

Y-linked 15-targeted microRNA-455-5p to prevent cardiomyocyte

apoptosis and rescue cell migration and invasion (39). In mice with traumatic brain injury,

LPS stimulates the expression of JDP2, and JDP2 overexpression

aggravates LPS-induced inflammation and apoptosis of mouse

astrocytes (40). Consistent with

these findings, the results of the present study demonstrated that

JDP2 overexpression attenuated the ameliorative effect of PDE4B

knockdown on cell viability, cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and

apoptosis in H/R-stimulated H9c2 cardiomyocytes.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrated that the transcription factor JDP2 activated PDE4B

expression to participate in H/R-induced oxidative and apoptotic

injuries of H9c2 cardiomyocytes, partially explaining the

pathogenic mechanism underlying myocardial I/R injury. Taken

together, the results of the present study suggested that PDE4B and

JDP2 may serve as promising biomarkers and therapeutic targets in

AMI diagnosis and treatment. However, further in vivo

studies are required to confirm the results of the present

study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SL and ZZ were responsible for the conception of the

study and the drafting of the manuscript. SL, YC, YJ, TX and XH

assisted in obtaining experimental data and analyzed the data. ZZ

revised the manuscript. SL and ZZ confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Pollard TJ: The acute myocardial

infarction. Prim Care. 27:631–649;vi. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Beltrame JF: Nitrate therapy in acute

myocardial infarction: Potion or poison? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther.

22:165–168. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jensen AE, Reikvam A and Asberg A:

Diagnostic efficiency of lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes in serum

after acute myocardial infarction. Scand J Clin Lab Invest.

50:285–289. 1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hurst JW: Thoughts about the abnormalities

in the electrocardiogram of patients with acute myocardial

infarction with emphasis on a more accurate method of interpreting

ST-segment displacement: Part I. Clin Cardiol. 30:381–390.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sattar Y and Alraies MC: Ventricular

aneurysm. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island,

FL, 2021.

|

|

6

|

Lindower P, Embrey R and Vandenberg B:

Echocardiographic diagnosis of mechanical complications in acute

myocardial infarction. Clin Intensive Care. 4:276–283.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li J, Li X, Wang Q, Hu S, Wang Y, Masoudi

FA, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM and Jiang L: China PEACE Collaborative

Group. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from

2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-retrospective acute myocardial

infarction study): A retrospective analysis of hospital data.

Lancet. 385:441–451. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Neri M, Riezzo I, Pascale N, Pomara C and

Turillazzi E: Ischemia/reperfusion injury following acute

myocardial infarction: A critical issue for clinicians and forensic

pathologists. Mediators Inflamm. 2017(7018393)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Bagai A, Dangas GD, Stone GW and Granger

CB: Reperfusion strategies in acute coronary syndromes. Circ Res.

114:1918–1928. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Borer JS and Lewis BS: Therapeutic

coronary reperfusion and reperfusion injury: An introduction.

Cardiology. 135(13)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhou H and Toan S: Pathological roles of

mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitochondrial dynamics in

cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomolecules.

10(85)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tibbo AJ and Baillie GS: Phosphodiesterase

4B: Master regulator of brain signaling. Cells.

9(1254)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xie H, Zha E and Zhang Y: Identification

of featured metabolism-related genes in patients with acute

myocardial infarction. Dis Markers. 2020(8880004)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Guo H, Cheng Y, Wang C, Wu J, Zou Z, Niu

B, Yu H, Wang H and Xu J: FFPM, a PDE4 inhibitor, reverses learning

and memory deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via cAMP/PKA/CREB

signaling and anti-inflammatory effects. Neuropharmacology.

116:260–269. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhong J, Yu H, Huang C, Zhong Q, Chen Y,

Xie J, Zhou Z, Xu J and Wang H: Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4

by FCPR16 protects SH-SY5Y cells against MPP+-induced

decline of mitochondrial membrane potential and oxidative stress.

Redox Biol. 16:47–58. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tsai MH, Wuputra K, Lin YC, Lin CS and

Yokoyama KK: Multiple functions of the histone chaperone Jun

dimerization protein 2. Gene. 590:193–200. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Heger J, Bornbaum J, Würfel A, Hill C,

Brockmann N, Gáspár R, Pálóczi J, Varga ZV, Sárközy M, Bencsik P,

et al: JDP2 overexpression provokes cardiac dysfunction in mice.

Sci Rep. 8(7647)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Duan Y, Cheng S, Jia L, Zhang Z and Chen

L: PDRPS7 protects cardiac cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury

through inactivation of JNKs. FEBS Open Bio. 10:593–606.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rocha EAV: Fifty years of coronary artery

bypass graft surgery. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 32:2–3.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang MX, Liu X, Li JM, Liu L, Lu W and

Chen GC: Inhibition of CACNA1H can alleviate endoplasmic reticulum

stress and reduce myocardial cell apoptosis caused by myocardial

infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:12887–12895.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chen YQ, Yang X, Xu W, Yan Y, Chen XM and

Huang ZQ: Knockdown of lncRNA TTTY15 alleviates myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury through the miR-374a-5p/FOXO1 axis.

IUBMB Life. 73:273–285. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Tibaut M, Mekis D and Petrovic D:

Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction and acute management

strategies. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 14:150–159.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Dong Y, Chen H, Gao J, Liu Y, Li J and

Wang J: Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and

autophagy in coronary heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 136:27–41.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shen Y, Liu X, Shi J and Wu X: Involvement

of Nrf2 in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Int J Biol

Macromol. 125:496–502. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Granger DN and Kvietys PR: Reperfusion

injury and reactive oxygen species: The evolution of a concept.

Redox Biol. 6:524–551. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lee SJ, Lee CK, Kang S, Park I, Kim YH,

Kim SK, Hong SP, Bae H, He Y, Kubota Y and Koh GY: Angiopoietin-2

exacerbates cardiac hypoxia and inflammation after myocardial

infarction. J Clin Invest. 128:5018–5033. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu Z, Ma C, Gu J and Yu M: Potential

biomarkers of acute myocardial infarction based on weighted gene

co-expression network analysis. Biomed Eng Online.

18(9)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Sheng X, Fan T and Jin X: Identification

of key genes involved in acute myocardial infarction by comparative

transcriptome analysis. Biomed Res Int.

2020(1470867)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pearse DD and Hughes ZA: PDE4B as a

microglia target to reduce neuroinflammation. Glia. 64:1698–1709.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zheng XY, Chen JC, Xie QM, Chen JQ and

Tang HF: Anti-inflammatory effect of ciclamilast in an allergic

model involving the expression of PDE4B. Mol Med Rep. 19:1728–1738.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Pleiman JK, Irving AA, Wang Z, Toraason E,

Clipson L, Dove WF, Deming DA and Newton MA: The conserved

protective cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase function PDE4B is expressed

in the adenoma and adjacent normal colonic epithelium of mammals

and silenced in colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet.

14(e1007611)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Karam S, Margaria JP, Bourcier A, Mika D,

Varin A, Bedioune I, Lindner M, Bouadjel K, Dessillons M, Gaudin F,

et al: Cardiac overexpression of PDE4B blunts β-adrenergic response

and maladaptive remodeling in heart failure. Circulation.

142:161–174. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Xu B, Qin Y, Li D, Cai N, Wu J, Jiang L,

Jie L, Zhou Z, Xu J and Wang H: Inhibition of PDE4 protects neurons

against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced endoplasmic reticulum

stress through activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Redox Biol.

28(101342)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

You T, Cheng Y, Zhong J, Bi B, Zeng B,

Zheng W, Wang H and Xu J: Roflupram, a phosphodiesterase 4

inhibitior, suppresses inflammasome activation through autophagy in

microglial cells. ACS Chem Neurosci. 8:2381–2392. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ma H, Shi J, Wang C, Guo L, Gong Y, Li J,

Gong Y, Yun F, Zhao H and Li E: Blockade of PDE4B limits lung

vascular permeability and lung inflammation in LPS-induced acute

lung injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 450:1560–1567.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Liu XQ, Jin J, Li Z, Jiang L, Dong YH, Cai

YT, Wu MF, Wang JN, Ma TT, Wen JG, et al: Rutaecarpine derivative

Cpd-6c alleviates acute kidney injury by targeting PDE4B, a key

enzyme mediating inflammation in cisplatin nephropathy. Biochem

Pharmacol. 180(114132)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang S and Cao N: Uncovering potential

differentially expressed miRNAs and targeted mRNAs in myocardial

infarction based on integrating analysis. Mol Med Rep.

22:4383–4395. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Huang S, Tao W, Guo Z, Cao J and Huang X:

Suppression of long noncoding RNA TTTY15 attenuates hypoxia-induced

cardiomyocytes injury by targeting miR-455-5p. Gene. 701:1–8.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang XH, Liu Q and Shao ZT: Deletion of

JDP2 improves neurological outcomes of traumatic brain injury (TBI)

in mice: Inactivation of caspase-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

504:805–811. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|