Introduction

To date, the potential side-effects of alternative

medicine remedies have remained largely elusive. Sodium bicarbonate

(baking soda) is a low-cost, accessible, over-the-counter

substance, widely recognized for its multiple uses. Most

frequently, it is consumed as an antacid, despite the availability

of proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers (1). The undesired effects of baking soda

misuse may present as different clinical scenarios, which have not

been systematized until now. While baking soda is generally

considered safe, various cases who developed metabolic alkalosis

and electrolyte imbalances due to baking soda overdose have been

documented (1). The present study

reported on a case of metabolic alkalosis caused by baking soda

misuse and provided a review of similar cases published to date. To

the best of our knowledge, the patient of the present study is the

first reported case of baking soda toxicity related to its oral

ingestion as an alternative remedy for gout.

Case report

Case presentation

A 69-year-old male patient was referred to the

neurology emergency department of ‘N. Oblu’ Emergency Hospital

(Iasi, Romania) in October 2021, by his family due to altered

mental state, including confusion, which started 2 days prior to

admission, with progressive worsening. The neurological exam did

not reveal any focal clinical signs and craniocerebral CT excluded

the possibility of an acute neurological event. A brief biological

investigation indicated elevated serum creatinine levels (4.02

mg/dl; normal range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dl), metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.61;

normal range, 7.31-7.41) bicarbonate levels in blood plasma of 53.2

mmol/l (normal range, 22-29 mmol/l) and hypokalemia (serum

potassium K+, 2.6 mEq/l; normal range, 3.5-5.1 mEq/l).

On the next day, the patient was consequently referred to the

Nephrology Department of the Clinical Hospital ‘Dr C.I. Parhon’

(Iasi, Romania) for further investigation.

Medical history. The patient's medical

history included gout diagnosed in 1974, without any rheumatology

consultation, for which the patient received intermittent treatment

with colchicine 1 mg once daily (od) (3-6 months/year), ketoprofen

100 mg twice daily (bid) and allopurinol 100 mg/day od. The

patient's cardiovascular antecedents included third-degree arterial

hypertension and permanent atrial fibrillation since 2015, for

which he was chronically anticoagulated with a direct oral

anticoagulant (DOAC) (apixaban 5 mg bid). The patient's home

medication also included a β-blocker (carvedilol 6.25 mg bid), an

angiotensin II receptor blocker (candesartan 8 mg bid), a diuretic

(indapamide 1.5 mg od) and a statin (atorvastatin 20 mg od). The

patient had recently undergone surgical interventions for a

perianal fistula, and on this occasion, examination revealed

elevated creatinine levels, interpreted in the context of chronic

uric acid nephropathy (1.9 mg/dl in April 2021). The perianal

fistula was interpreted in the context of prolonged sitting due to

the patient's occupation as a bus driver.

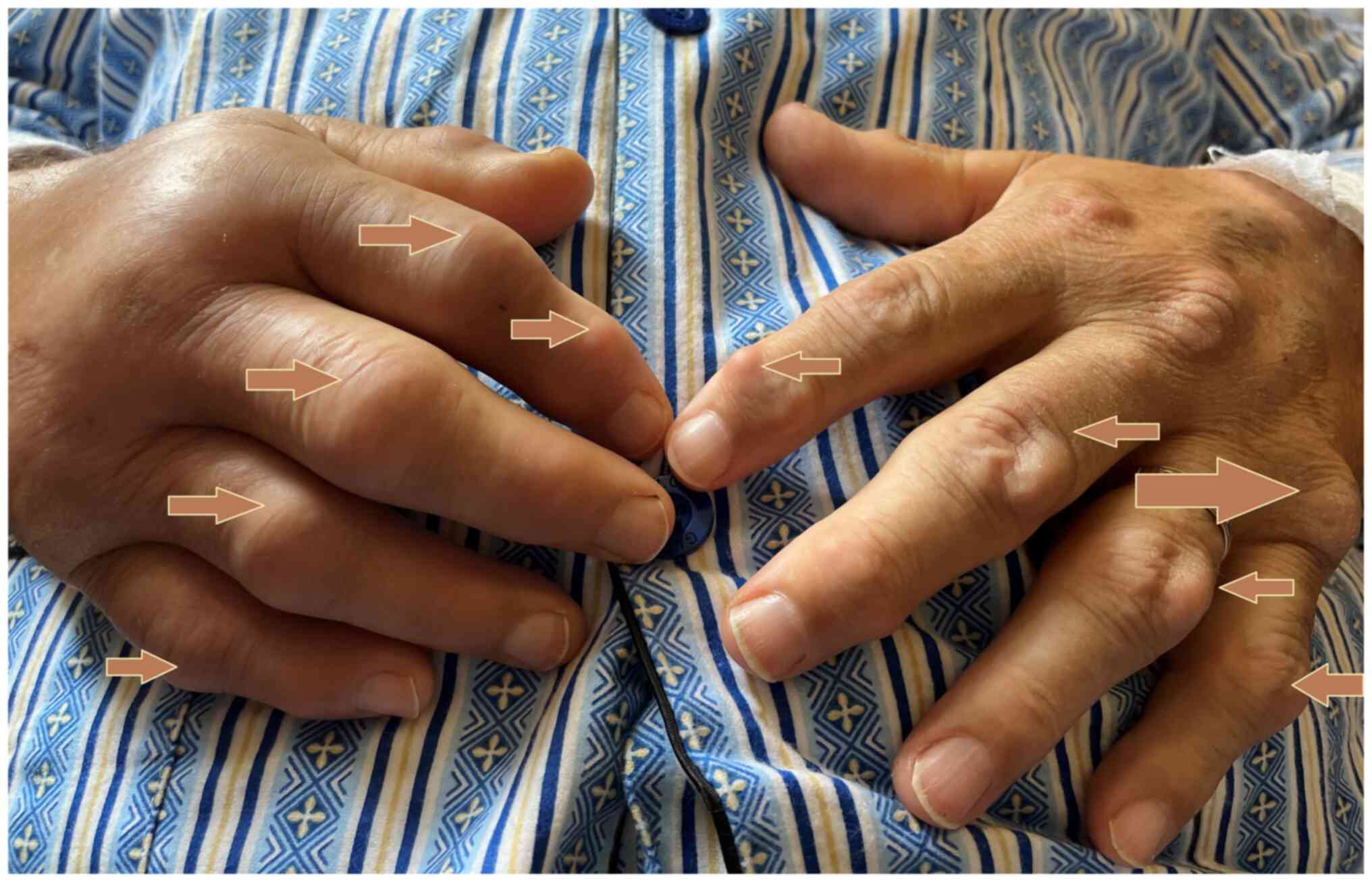

Physical examination upon admission. The

patient had an altered mental state, namely he was confused and

agitated, without fever (temperature of 36.5˚C), with a heart rate

of 100 beats/min, blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg, respiratory rate

of 13 breaths/min and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Close

examination revealed multiple tophi on the extremities and celsian

signs on the extremities (redness, swelling, heat and pain)

(Fig. 1). According to the 2015

ACR-EULAR Gout Classification Criteria, the score calculated for

our patient is 20 (out of 23) (2).

Cardiac examination revealed an irregular heart rate and rhythm

with no murmur or extra heart sounds. The lungs were clear of

auscultation bilaterally. No peripheral edema was noted.

The electrocardiogram on admission revealed atrial

fibrillation with a ventricular rate of 104 beats/min, a -15˚ QRS

axis and left anterior fascicular block.

The blood tests indicated elevated serum creatinine

and urea levels [creatinine, 4.02 mg/dl; urea, 148 mg/dl (normal

range, 20-49 mg/dl)]; hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.61);

bicarbonate, 53.2 mmol/l; pCO2, 53 mmHg; Cl, 78 mEq/l

(normal range, 94-110 mEq/l in blood plasma), hypokalemia

(K+, 2.6 mEq/l), elevated hepatic cytolysis enzymes,

including alanine transaminase (955 U/l; normal range, 4-33 U/l);

aspartate transaminase (1,091 U/l; normal range, 8-35 U/l),

hyperuricemia [serum uric acid (SUA), 10.3 mg/dl; normal range,

3.5-7 mg/dl], inflammatory syndrome [white blood cells,

10,920/mm3; normal range, 4,000-10,000/mm3;

C-reactive protein, 440 mg/l; normal range, <5 mg/l; erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) >140 mm/h; normal range, 1-10 mm/h];

and normocytic normochromic anemia [red blood cells, 3,49

million/mm3 (normal range,

4.6-6.0x106/mm3); hemoglobin, 10.5 g/dl,

(normal range, 13-16 g/dl); hematocrit, 35.2% (normal range,

40-50%). The secretion culture from the perianal fistula was

positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus

mirabilis.

Treatment of the patient

Given the patient's altered mental state, a thorough

anamnesis was only possible on the second day of hospitalization at

the nephrology department, revealing that the patient had consumed

20 g of baking soda dissolved in 2 liters of water per day as an

alternative treatment for ‘dissolving the tophi’ in the week prior

to admission.

Intravenous (iv) hydration with physiological serum

0.9% 1,000 ml, iv KCl 60 mEq/l/day was initiated along with

potassium correction, iv dexamethasone 6 mg and per os

colchicine 0.5 mg (1 tablet twice per day) for gout attack and

antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone 1 g twice per day in accordance

with the antibiogram for 7 days. The in-hospital response of the

patient was favorable, with remission of the hydro-electrolyte and

acid-base imbalances. At discharge, the hepatic injury and

inflammation markers were within normal limits and the creatinine

serum level was 1.9 mg/dl. Angiotensin II receptor blocker

treatment was ceased, with normal in-hospital blood pressure

control. Given the atrial fibrillation, heart rate,

CHA2D2-VASc score (a score used to assess the

risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation patients defined by the

Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, Diabetes

mellitus, Stroke, Vascular disease, Age 65-74 years, Sex

category-female) of 3 points and HAS-BLED score of 3 points (a

score to predict bleeding risk based on the following risk factors:

Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding

history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly - >65 years,

drugs/alcohol; a score over 3 indicates high bleeding risk), the

patient was discharged with instructions to continue his DOAC and

β-blocker therapy (3). In

addition, febuxostat therapy with a low starting dose (40 mg od)

was prescribed.

Treatment outcomes and follow-up

The 1-month follow-up revealed a euvolemic,

hemodynamically stable patient. Post-discharge creatinine levels

were stationary, while SUA levels improved (SUA, 6.5 mg/dl).

At-home blood pressure control was adequate without angiotensin II

receptor blocker. However, the patient complained about the acute

gout arthritis of his upper left limb (Fig. 2). At 1 day prior to his follow-up,

the patient consulted a rheumatologist who recommended short-term

colchicine administration and an increase of the dose of febuxostat

to 80 mg od.

Discussion

A literature search was performed in the

PubMed/MEDLINE and ScienceDirect/Elsevier electronic databases for

reported cases of sodium bicarbonate toxicity in adult patients.

Search terms included ‘baking soda misuse’, ‘baking soda toxicity’,

‘baking soda overdose’, ‘sodium bicarbonate misuse’, ‘sodium

bicarbonate toxicity’ and ‘sodium bicarbonate overdose’. References

from the included articles were also scanned to identify possible

additional publications.

EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters) bibliography manager

was used to check the title and abstracts of the retrieved and

screened articles. Duplicate articles were electronically and

manually removed (in the case of differences in the citation style

of the different journals). After screening all the relevant

articles found, a total of 21 clinical cases published between 1986

and 2020 were included. Basic characteristics of the studies were

summarized in Table I (name of the

first author, year of publication, medical history, baking soda

exposure, methods of diagnosis, laboratory values, reference test).

Baking soda is a commonly used remedy to counteract high acidity

symptoms, such as heartburn. However, other uses include the

treatment of hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, prevention of

contrast-induced nephropathy and urine alkalinization (4). According to popular beliefs, sodium

bicarbonate, as a strong base, neutralizes the acidic state in

which uric acid precipitates. Although no scientific evidence

supports these effects, baking soda has gained popularity as an

alternative treatment for gout. As an over-the-counter antacid,

baking soda is considered safe by the Food and Drug Administration

at a maximum daily dosage of 200 mEq sodium bicarbonate in young

individuals and 100 mEq sodium bicarbonate in those aged >60

years (5). One teaspoon (5 g) of

baking soda contains ~59 mEq of sodium bicarbonate (6). The patient of the present study

declared the intake of ~20 g of sodium bicarbonate, which

translates into ~238 mEq sodium bicarbonate, exceeding the

recommended safe dose.

| Table IList of reported cases of baking soda

toxicity in adult patients. |

Table I

List of reported cases of baking soda

toxicity in adult patients.

| First author,

year | Presentation | Medical history | Baking soda

exposure | Laboratory

values | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Al-Abri and Olson,

2013 | Metabolic alkalosis

Ventricular tachycardia | HTN DM

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome | Antacid replacement:

1 teaspoon of baking soda on an as needed basis for years | pH 7.5

HCO3 | (6) |

| 46 mmol/l |

| K+ 2.0

mEq/l |

| Na+ 122

mEq/l |

| Cl- 59

mEq/l |

| Cr 0.9 mg/dl |

| Cervantes et

al, 2020 | Metabolic

alkalosis | CKD G3bA1 HTN AF

Hyperlipidemia GERD | Topical use three

times/day for tooth hygiene for the previous 6 months | pH 7.5 | (8) |

| HCO3 44

mmol/l |

| K+ 3.6

mEq/l |

| Na+ 146

mEq/l |

| Cl- 95

mEq/l |

| Cr 1.37 mg/dl |

| Solak et al,

2009 | Metabolic alkalosis

Sleep apnea Volume overload Uncontrolled HTN | ESRD CHF DM type 2

Hypothyroidism Chronic gastritis | Antacid abuse: 4-5

packs of baking soda a day over the last month Cl- 83

mEq/l | pH 7 637 | (9) |

| HCO3 45

mmol/l |

| K+ 3.3

mEq/l |

| Na+ 141

mEq/l |

| Sahani et al,

2001 | Metabolic

alkalosis | ESRD | Hiccup relief:

Consumption of ¾ bottle of Bromo-Seltzer (containing 89 g sodium

bicarbonate) | pH 7.53

HCO3 | (10) |

| 40 mmol/l

K+ |

| 3.5 mEq/l |

| Na+ 143

mEq/l |

| Cl- 89

mEq/l |

| Cr 1.0 mg/dl |

| Galinko et al,

2017 | Metabolic alkalosis

Acute kidney injury Acute hypoxic respiratory failure Lactic

acidosis Altered mental state Ventricular tachycardia | HTN Meningioma

(surgical resection, ventriculoperitoneal shunt and radiation

therapy) Breast cancer | Alternative topical

treatment for breast cancer -113 g of baking soda applied topically

every 4 days for several weeks | pH 7.66 | (11) |

| HCO3

>45 mmol/l |

| K+ 2.6

mEq/l |

| Na+ 158

mEq/l |

| Cl- 92

mEq/l |

| Cr 1.9 mg/dl |

| Soliz et al,

2014 | Metabolic

alkalosis | Colon cancer

Sinonasal melanoma | Alternative

treatment for colon cancer: 1 liter of pH 7.8-8 water obtained from

bottled water, key lime juice a quarter of tablespoon baking

soda | pH 7.65 | (12) |

| HCO3 39

mmol/l |

| K+ 2.6

mEq/l |

| Na+ 123

mEq/l |

| Okada et al,

1996 | Metabolic alkalosis

and myoclonus | HTN Cerebral

infarction Gastrectomy (gastric ulcer) | Antacid (625 mg

sodium bicarbonate) for a 6-month period | pH 7.481 | (13) |

| HCO3

33.9 mmol/l |

| K+ 2.7

mEq/l |

| John et al,

2012 | Metabolic alkalosis

Respiratory alkalosis High-anion gap metabolic acidosis | Foot ulcers for 2

years | Ingestion and

application of baking soda to leg ulcers for 1.5 years | pH 7.69 | (14) |

| HCO3 54

mmol/l |

| K+ 1.8

mEq/l |

| Na+ 148

mEq/l |

| Cl- 73

mEq/l |

| Cr 3.4 mg/dl |

| Hughes et

al, 2016 | Metabolic alkalosis

Hypernatremia Hemorrhagic encephalopathy Altered mental state | Schizophrenia

Polysubstance abuse | Patient was unable

to explain cause of ingestion- 1 box of baking soda (454 g) | pH 7.53 | (15) |

| HCO3 50

mEq/l |

| K+ 2.5

mEq/l |

| Na+ 172

mEq/l |

| Cl- 98

mEq/l |

| Glucose |

| 433 mg/dl Cr |

| 1.85 mg/dl |

| Ajbani et

al, 2011 | Metabolic

alkalosis | HTN COPD | Antacid

replacement: Unknown quantity of baking soda over several

weeks | pH 7.59 | (16) |

| HCO3 56

mmol/l |

| K+ 1.7

mEq/l |

| Na+ 121

mEq/l |

| Cl- 53

mEq/l |

| Cr 3.3 mg/dl |

| Fitzgibbons and

Snoey, 1999 (Case 1) | Metabolic alkalosis

Ventricular tachydysrhythmia | Peptic ulcer

disease with perforation | Antacid

replacement: Several tablespoons of baking soda | pH 7.56 | (17) |

| HCO3 58

mmol/l |

| K+ 1.8

mEq/l |

| Na+ 129

mEq/l |

| Cl- 55

mEq/l |

| Cr 2.8 mg/dl |

| Fitzgibbons and

Snoey, 1999 (Case 2) | Metabolic alkalosis

Altered mental state | HTN Herpes zoster

infection Hepatitis | Antacid

replacement: One box of baking soda | pH 7.49 | (17) |

| HCO3 41

mmol/l |

| K+ 2.8

mEq/l |

| Na+ 146

mEq/l |

| Cl- 90

mEq/l |

| Cr 0.9 mg/dl |

| Thomas and Stone,

1994 | Metabolic

alkalosis | Alcoholic

esophagitis and gastritis | Antacid misuse:

10-12 oz of baking soda | pH 7.55 | (18) |

| HCO3

44.5 mmol/l |

| Na+ 136

mEq/l |

| K+ 2.5

mEq/l |

| Cl- 77

mEq/l |

| Cr 2.4 mg/dl |

| Gawarammana et

al, 2007 | Metabolic alkalosis

Coma (GCS 3/15) | N/A | Antacid: 2 liters

of Gaviscon in the prior 48 h | pH 7.54 | (19) |

| HCO3

50.6 mmol/l |

| K+ 1.6

mEq/l |

| Na+ 127

mEq/l |

| Cl- 66

mEq/l |

| Mennen and Slovis,

1988 | Metabolic alkalosis

Cardiopulmonary arrest Death | HTN Peptic ulcer

disease Alcohol abuse Seizure disorder | Antacid misuse:

Amount unknown | pH 7.73 | (20) |

| HCO3

>40 mmol/l |

| Na+ 154

mEq/l |

| K+ 3.2

mEq/l |

| Cl- 53

mEq/l |

| Cr 1.4 mg/dl |

| Forslund et

al, 2008 | Metabolic alkalosis

Epileptiformic convulsions Subdural hemorrhage Rhabdomyolysis | Alcohol abuse | Antacid abuse: 40

years history of baking soda abuse; 10-15 g daily initially, slowly

increasing up to 50 g daily during last year | pH 7.57 | (21) |

| HCO3 85

mmol/l |

| K+ 2.3

mEq/l |

| Na+ 147

mEq/l |

| Cl- 46

mEq/l |

| Yi et al,

2012 | Metabolic

alkalosis | Alcohol abuse | Antacid

replacement: 3-5 tablespoons daily | pH 7.6 | (22) |

| HCO3 53

mmol/l |

| K+ 1.6

mEq/l |

| Na+ 131

mEq/l |

| Cl- 65

mEq/l |

| Cr 3.8 mg/dl |

| Scolari Childress

and Myles, 2013 | Rhabdomyolysis

Peripartum cardiomyopathy | Pregnant, at 37

weeks of gestation with history of hyperemesis and iron-deficiency

anemia | Hiccup remedy: A

box of baking soda (454 g) every day for several years | Hb 8.2 g/dl Ht

26.3% | (23) |

| K+ 2.1

mmol/l |

| AST 134 U/l |

| ALT 60 U/l |

| Lazebnik et

al, 1986 | Stomach

rupture | N/A | Antacid misuse: One

tablespoon of sodium bicarbonate | N/A | (24) |

| Linford and James,

1986 | Metabolic

alkalosis | N/A | Bicarbonate abuse:

50-150 g daily | HCO3

>40 mmol/l K+ 1.8 mEq/l | (25) |

| Okada et al,

1999 | Metabolic alkalosis

Sleep apnea Hypertension | ESRD | Antacid

replacement: | pH 7.47

HCO3 | (26) |

| 40.1 mmol/l |

The increase in renal tubular pH by baking soda

alters the excretion of anti-inflammatory medications, increasing

their serum levels (7). In the

specific case of the present study, this may explain the onset of

acute kidney injury and liver toxicity as a result of high intake

of baking soda combined with ketoprofen. Caution should be advised

when prescribing sodium bicarbonate, particularly when combined

with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other

anti-inflammatory drugs.

Chronic interstitial nephritis that is associated

with hyperuricemia may be considered when SUA levels are

disproportionately high in contrast with the patient's renal

impairment (4). Patients usually

consult the medical unit with hypertension and mildly impaired

renal function. Minor proteinuria and tubular dysfunction may be

present (4). Given the patient's

poor response to allopurinol over the years, the choice of chronic

treatment recommendation for the present case was febuxostat, a

selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor, with a low starting dose (40

mg od). In contrast to allopurinol, febuxostat does not require

dose adjustments at a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate

and is associated with a smaller incidence of hypersensitivity or

nephrotoxicity (4). At the 1-month

follow-up, the patient's condition was under good control with

febuxostat treatment, with normal SUA levels.

Metabolic alkalosis due to baking soda oral

ingestion to treat dyspepsia has been previously reported. A number

of cases of adverse toxic effects of topically applied baking soda

have been reported, which was used as an alternative to

chemotherapy for breast (5) and

colon cancer (6), for the

treatment of leg ulcer (7) and as

a toothpaste additive (8). A

review indicated that the most common reasons for bicarbonate

exposure were antacid misuse (60.4%), urinary drug testing

alterations (11.5%), treatment of urinary tract infections (4.7%)

and as a means for body detoxification (4.7%) (1). A case of misuse as a remedy for gout

was also identified (1).

The most common presentation of baking soda toxicity

is metabolic alkalosis and electrolyte changes. Usually, the kidney

responds by increasing bicarbonate excretion, which may become

impaired in the setting of renal insufficiency or volume

contraction. Metabolic acidosis is a common finding in chronic

kidney disease (4). Though less

common in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing

hemodialysis, there were 2 reported cases of metabolic alkalosis

attributed to oral baking soda intake (9,10).

In spite of a history of third-degree arterial

hypertension, the patient of the present study had controlled blood

tension values without the use of any hypotensive agent both during

hospitalization and at the 1-month follow-up. However, further

monitoring is necessary to evaluate whether the effect is temporary

and investigate its cause. Previously, 2 cases who developed

hypotension and required vasopressors for hemodynamic support were

reported (11,12). One of them also exhibited a

decrease in anesthetic demand (12). On the other hand, transient daytime

hypertension has been observed, but was interpreted in the context

of sleep apnea (13).

The altered mental state of the patient of the

present study delayed the accurate identification of the underlying

cause of metabolic alkalosis. Mental state alterations are common

in patients with severe metabolic alkalosis. Agitation and

confusion (14-16),

dizziness with or without loss of consciousness (17,18),

stuttering (15), obnubilation

(11) and coma (19,20)

have been reported. For 1 case, hypernatremic hemorrhagic

encephalopathy due to baking soda ingestion was reported, with

multiple areas of intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage observed

on the cranial computed tomography (15). Neuromuscular symptoms are commonly

described in patients with severe metabolic alkalosis. Paresthesia

and carpopedal spasm without a positive Chvostek's sign (20), involuntary facial twitching

(15), increased motor tone with

flexion of elbows and wrists (20), myoclonus (13) and epileptiform convulsions

(21) have also been described.

Furthermore, 2 patients with sleep apnea were referred, which may

occur in the metabolic alkalosis setting due to central ventilatory

drive depression (9,13).

Patients with a history of alcohol abuse may have an

increased susceptibility to developing metabolic alkalosis due to

high baking soda intake (17,18,20-22).

Chronic alcoholics are more inclined to ingest antacids for

dyspepsia relief, while their dehydration status may promote and

aggravate metabolic alterations. Rhabdomyolysis has been reported

in an alcoholic patient (21) and

in pregnant patients with pica leading to baking soda intake

(23). Other systemic

complications, such as spontaneous gastric rupture, have also been

described (24).

In conclusion, the present study reported a case of

baking soda toxicity resulting in metabolic alkalosis, toxic acute

hepatitis and acute kidney injury. The case described herein

provided a challenge in establishing a diagnosis of metabolic

alkalosis with unknown etiology until thorough anamnesis was

possible. The present case report and literature review highlights

the importance of closely evaluating all the alternative therapies

that patients resort to. Exposure to these substances may not be

easily disclosed, as their implications are frequently underrated.

Physicians should be aware of the potential practices and

associated side effects in order to ensure prompt diagnosis and

adequate treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

All authors substantially contributed to this paper.

AD and LF designed the study, searched the literature and wrote the

first draft of the manuscript. CEV, IF and RA collected and

interpreted the relevant data. AD, LF and IF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. CEV and LF supervised the

literature review and revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of this case report, including medical information

and the accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Al-Abri SA and Kearney T: Baking soda

misuse as a home remedy: Case experience of the california poison

control system. J Clin Pharm Ther. 39:73–77. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J,

Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, Brown M, Choi H, Edwards NL, Janssens

HJ, et al: 2015 gout classification criteria: An American college

of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative

initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67:2557–2568. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo

E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA,

Dilaveris PE, et al: 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and

management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with

the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS): The

task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation

of the European society of cardiology (ESC) Developed with the

special contribution of the European heart rhythm association

(EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 42:373–498. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Feehally J, Floege J, Tonelli M and

Johndon RJ: Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology. 6th edition,

2019.

|

|

5

|

Jouffroy R and Vivien B: Sodium

bicarbonate administration and subsequent potassium concentration

in hyperkalemia treatment: Do not forget the initial pH-value. Am J

Emerg Med. 56:302–303. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Al-Abri SA and Olson KR: Baking soda can

settle the stomach but upset the heart: Case files of the Medical

Toxicology fellowship at the university of California, San

Francisco. J Med Toxicol. 9:255–258. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Senewiratne NL, Woodall A and Can AS:

Sodium Bicarbonate. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL,

2022.

|

|

8

|

Cervantes CE, Menez S, Jaar BG and

Hanouneh M: An unusual cause of metabolic alkalosis: Hiding in

plain sight. BMC Nephrol. 21(296)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Solak Y, Turkmen K, Atalay H and Turk S:

Baking soda induced severe metabolic alkalosis in a haemodialysis

patient. NDT Plus. 2:280–281. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sahani MM, Brennan JF, Nwakanma C, Chow

MT, Ing TS and Leehey DJ: Metabolic alkalosis in a hemodialysis

patient after ingestion of a large amount of an antacid medication.

Artif Organs. 25:313–315. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Galinko LB, Hsu SH, Gauran C, Fingerhood

ML, Pastores SM, Halpern NA and Chawla S: A basic therapy gone

awry. Am J Crit Care. 26:491–494. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Soliz J, Lim J and Zheng G: Anesthetic

management of a patient with sustained severe metabolic alkalosis

and electrolyte abnormalities caused by ingestion of baking soda.

Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2014(930153)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Okada K, Kono N, Kobayashi S and Yamaguchi

S: Metabolic alkalosis and myoclonus from antacid ingestion. Intern

Med. 35:515–516. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

John RS, Simoes S and Reddi AS: A patient

with foot ulcer and severe metabolic alkalosis. Am J Emerg Med.

30:260 e5–8. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hughes A, Brown A and Valento M:

Hemorrhagic encephalopathy from acute baking soda ingestion. West J

Emerg Med. 17:619–622. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ajbani K, Chansky ME and Baumann BM:

Homespun remedy, homespun toxicity: Baking soda ingestion for

dyspepsia. J Emerg Med. 40:e71–e74. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fitzgibbons LJ and Snoey ER: Severe

metabolic alkalosis due to baking soda ingestion: Case reports of

two patients with unsuspected antacid overdose. J Emerg Med.

17:57–61. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Thomas SH and Stone CK: Acute toxicity

from baking soda ingestion. Am J Emerg Med. 12:57–59.

1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Gawarammana IB, Coburn J, Greene S, Dargan

PI and Jones AL: Severe hypokalaemic metabolic alkalosis following

ingestion of gaviscon. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 45:176–178.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mennen M and Slovis CM: Severe metabolic

alkalosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 17:354–357.

1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Forslund T, Koistinen A, Anttinen J,

Wagner B and Miettinen M: Forty years abuse of baking soda,

rhabdomyolysis, glomerulonephritis, hypertension leading to renal

failure: A case report. Clin Med Case Rep. 1:83–87. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yi JH, Han SW, Song JS and Kim HJ:

Metabolic alkalosis from unsuspected ingestion: Use of urine pH and

anion gap. Am J Kidney Dis. 59:577–581. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Scolari Childress KM and Myles T: Baking

soda pica associated with rhabdomyolysis and cardiomyopathy in

pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 122(2 Pt 2):495–497. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lazebnik N, Iellin A and Michowitz M:

Spontaneous rupture of the normal stomach after sodium bicarbonate

ingestion. J Clin Gastroenterol. 8:454–456. 1986.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Linford SM and James HD: Sodium

bicarbonate abuse: A case report. Br J Psychiatry. 149:502–503.

1986.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Okada H, Inoue T, Takahira S, Sugahara S,

Nakamoto H and Suzuki H: Daytime hypertension, sleep apnea and

metabolic alkalosis in a haemodialysis patient-the result of sodium

bicarbonate abuse. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 14:452–454.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|