Introduction

Lung cancer is a major cause of cancer-related

deaths worldwide and has limited treatment options. The numbers of

patients with lung cancer has been increased by 51% in the world

since 1985(1). Recent advances in

the treatment of lung cancer have increased our understanding of

tumor progression and disease biology. However, its cure and

survival rates remain poor, especially in advanced lung cancer.

Therefore, strategies to overcome drug resistance and develop new

drugs are required to increase the applicability of current

treatments to a larger lung cancer population (2,3).

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induces apoptosis via

interaction with the death receptors TRAILR1/death receptor (DR)4

and TRAILR2/DR5 in several types of cancer, but not in normal

cells. Despite the significant potential for use in cancer

treatment, the translation of TRAIL into clinical use has been

limited because of TRAIL resistance (4).

Oncogenic drivers in lung cancer are directed

against a large proportion of targeted therapies, which are more

prevalent in patients with only light exposure to tobacco smoke

(5). A large proportion of

glioblastoma patients continue to smoke or use e-cigarettes during

treatment, which may affect the efficacy of treatment (6). Nicotine is the primary component of

tobacco. Tobacco nicotine can lead to drug resistance during

glioblastoma chemotherapy (6).

Tobacco smoke induces LKB1/AMPK pathway deficiency by reducing

epithelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor

sensitivity in lung cancer (7).

Some studies show that lncRNAs might be useful drug

targets (8). A number of lncRNAs

play pivotal roles in lung cancer drug resistance (9). The lncRNA SNHGS is also involved in

cancers (10). To study whether

nicotine influences TRAIL resistance, the dysregulation of lncRNA

SNHGs in lung cancer tissues from smokers and nonsmokers was

screened. It was discovered that lncRNA SNHG5 was upregulated by

nicotine in lung cancer cells and that SNHG5 overexpression could

promote TRAIL resistance in lung cancer. The recruitment of

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) by overabundant

cytoplasm SNHG5 regulates cleaved caspase-3 expression to influence

cell apoptosis. The results showed that SNHG5/XIAP can promote

TRAIL resistance in lung cancer by altering cleaved caspase-3

expression, which is pivotal for lung cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Lung cancer tissues were collected from the Chaohu

Hospital affiliated to Anhui Medical University. All patients

signed informed consent for using samples. Inclusion criteria were

primary patients with lung cancer receiving surgery as initial

treatment and all clinicopathologic data were collected. Smoking

patients had been smoking for at least 20 years and smoked 20

cigarettes a day before surgical operation. The human ethics and

research ethics committees of Anhui Medical University approved the

study (approval no. 202104001).

Cells culture and transfection

Lung cancer cell lines of A549, HCC827 were obtained

from Cell Culture Center, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The

characteristics of A549 and HCC827 cell lines were identified by

STR analysis in 2020 and 2021 respectively. All experiments were

performed with mycoplasma-free cells. A549 and HCC827 cell lines

were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) with 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone; Cytiva), streptomycin

(100 µg/ml) and penicillin (100 U/ml). SNHG5 siRNAs, XIAP siRNAs

and control siRNAs were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd. The sequences of siRNA are in Table SI. A549 and HCC827 cells were

cultured in 6-well plates with 1x106 cells in 2 ml

complete medium for 24 h until they were 90% confluent. Cells were

transiently transfected with 50 nM SNHG5 siRNAs, XIAP siRNAs and

control siRNAs, respectively, using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's instructions. Following ~6 h of transfection at room

temperature, the medium was refreshed. The subsequent experiments

were performed after 48 h. Nicotine was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich

(cat. no. N3876). Nicotine was added to lung cancer cells with the

concentration 5 µg/ml or 10 µg/ml for an additional 24 h.

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

SNHG5 was identified by RT-qPCR. Cells were seeded

at a density of 1 million cells per ml for each subculture and a

minimum of 2 million cells were used for each RNA extraction. As

following the manufacturer's protocols, total cells or tissues RNAs

were extracted with TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The quantity and purity of RNA were measured with a Thermo

Scientific NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific Inc.). Regarding the cDNA synthesis, 1 µg total RNA was

reverse transcribed with the oligo(dT)18 primer and Reverse

Transcriptase M-MLV (Takara Bio Inc.) following the manufacturer's

instructions. qPCR was conducted using QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR

kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol on

a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows for Cq

values: 95˚C for 30 sec, followed with 40 cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec,

60˚C for 34 sec; and for melting curves: 95˚C for 15 sec, 60˚C for

1 min and 95˚C for 15 sec. All primers were designed using Primer

Premier 5.0 (Premier, Inc.). The primers were obtained from Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd. (Table SII).

RNA expression was normalized to GAPDH or U6. RNA relative

expression levels were calculated by using the 2-ΔΔCq

method (Bio-Rad CFX manager software 3.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) (11). The whole experiment

was repeated with two different sets of biological samples.

SNHG5 expression vector construction

and transfection

According to the instructions of the manufacturer,

total RNA in the cells was extracted by using Rneasy Mini kit

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The first-strand

complementary DNA (cDNA) of SNHG5 was obtained by using Maxima TM

First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and DNA was amplified using the primers (Table SII). RT-qPCR products and pcDNA3.1

vector were digested. The full-length sequence of SNHG5 was

inserted into pcDNA3.1 vector to obtain pcDNA3.1-SNHG5.

pcDNA3.1-SNHG5 and pcDNA3.1 empty vector were transfected in A549

and HCC827 cells as the overexpression group and control group,

respectively, using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were plated at a density of 500,000 cells/10-cm

plate 2 days prior to transfection. A total of 1 µg

SNHG5-overexpression plasmid and vector were transfected into the 6

well-plate cells, respectively. Following ~6 h of transfection, the

medium was refreshed. After 48 h, the cells were used for the

subsequent experiments.

Cellular fractionation

Norgen's cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA purification

kits (Norgen Biotek Corp.) were used to extract nuclear and

cytoplasmic RNA.

Apoptosis detection

The cells were washed three times using

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were stained using the

Annexin V/fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). The single cell

suspension was first incubated with 500 µl of 1X buffer, 5 µl of

Annexin V and 5 µl of Propidium Iodide (PI; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at 37˚C for 35 min in the dark. The cells were

detected by a FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and

analyzed by Win MDI. 2.9 software (TSRI Flow Cytometry Core

Facility). The rate of apoptosis was defined as the total

percentage of early and late apoptotic cells.

Western blotting

Using RIPA lysis buffer (RIPA; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) total protein was extracted from the cells. Using

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) the protein was quantified, and each sample (2 µg) was loaded

on 10% gels for SDS-PAGE. The protein was transferred on a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Sigma). Then the

membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk for ~2 h at room

temperature and the membrane was soaked in primary antibodies

against pro Caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab32150; Abcam), cleaved

Caspase-3 (1:500; cat. no. ab32042; Abcam) and GAPDH (1:1,000; cat.

no. bs-0755R; BIOSS) at 4˚C for 12 h and secondary antibodies (goat

anti-rabbit IgG H&L; 1:1,000; cat. no. bs-0295G; BIOSS) for 2 h

at room temperature. Bands were visualized by enhanced

chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL; cat. no. RPN3243; Cytiva) and

analyzed by ImageJ Software v1.53 (National Institutes of

Health).

RNA pull-down assay

SNHG5 and SNHG5-antisense were transcribed using the

templates of pcDNA3.1-SNHG5 and pcDNA3.1-SNHG5-antisense plasmids.

The plasmids were amplified. The primers are shown in the Table SI. Using Biotin-RNA Labeling Mix

(Roche Diagnostics) biotin-labeled RNAs were transcribed in vitro.

Then biotin-labeled RNAs were treated with RNase-free DNase I

(Takara Bio, Inc.) and purified with an RNeasy Mini kit (Roche

Diagnostics). RNA structure buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 7), 0.1 M KCl,

and 10 mM MgCl2] included biotinylated RNA was in 98˚C

for ~2 min, on ice for 5 min, and then kept at room temperature for

~35 min. Total protein lysates of A549 cells were mixed with

biotinylated RNA and incubated at room temperature. Streptavidin

agarose beads (5 µl; Cytiva; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were

added to each binding reaction and further incubated at room

temperature with rotation. The RNA-protein-beads compound were then

centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 1 min at room temperature and washed

three times with Wash buffer I and dissolved into RNase-free water.

After washes, the pull-down complexes were eluted by denaturation

in 1X protein loading buffer for 10 min at 100˚C. The samples were

then assessed by western blotting or proceeded to mass spectrometry

analysis. The captures were given electrophoresis with 12% sodium

dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel and silver stained. Mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS, A TripleTOF; AB Sciex Pte. Ltd.) identified

the protein bands after in-gel trypsin digestion.

RNA binding protein

immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

Magna RIP RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation

kit (Millipore Sigma) was used to perform RIP according to the

manufacturer's instructions in A549 cells induced by nicotine for

36 h. Antibody against XIAP obtained from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. The coprecipitated RNAs were adsorbed with

magnetic beads and detected by qPCR.

UV-RIP

A549 cells induced by nicotine for 36 h applied 100

mM 4-thiouridine (4-SU) were cultured for ~12 h. Then cells were

cross-linked by 365 nm UV light at a dose of 400 mJ/cm2

in UV-RIP assay. The other UV-RIP protocols were the same as

RIP.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS

software (version 15.0; SPSS, Inc.). The results were analyzed by

t-test or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test. Categorical

variables were analyzed by χ2 test. Data are presented

as the mean ± SEM. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

SNHG5 expression is increased in lung

cancer tissues from smokers

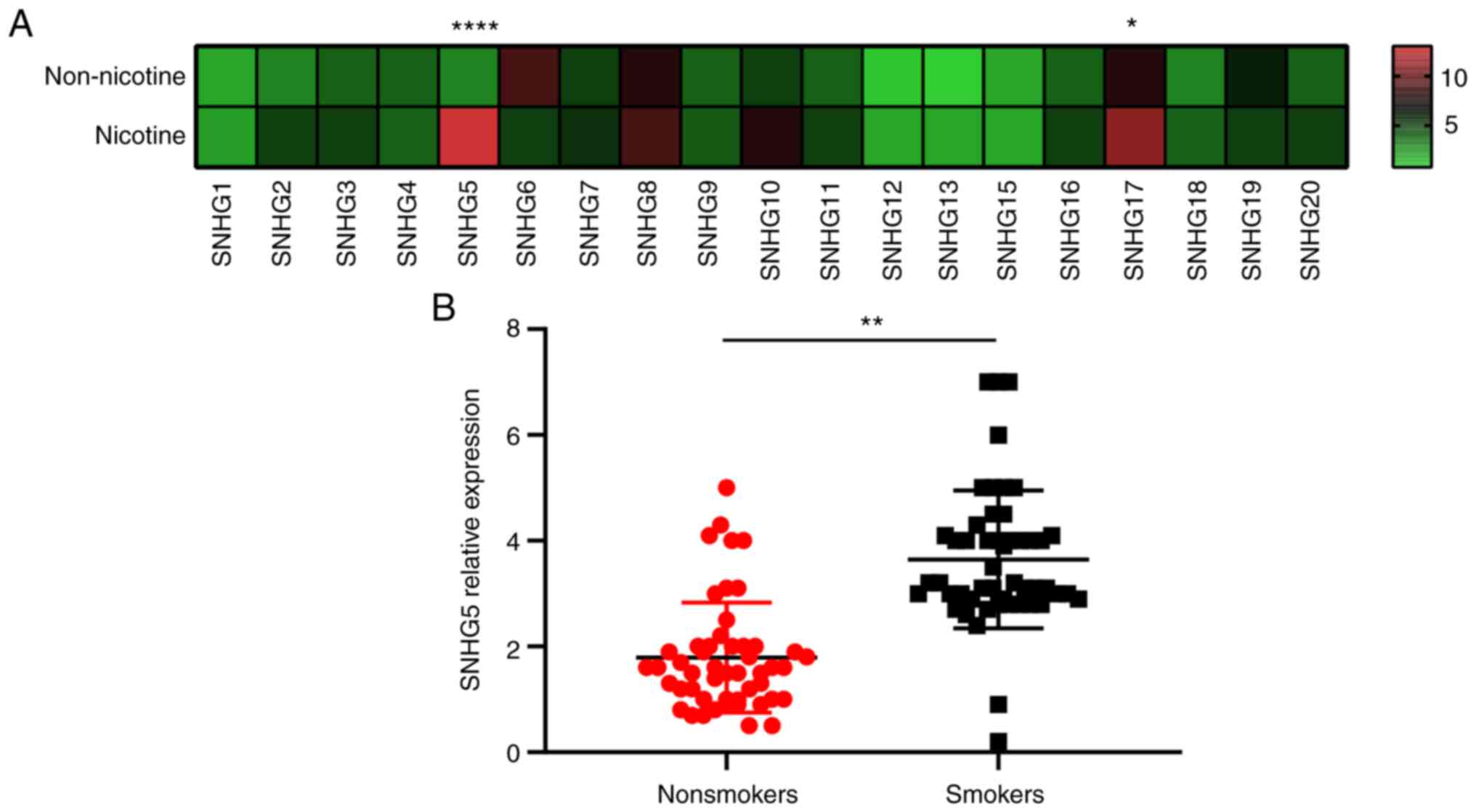

RT-qPCR was performed to identify the panel of SNHGs

in A549 cells. One group of cells was induced by nicotine and the

other group of cells was not induced. Among all the SNHGs tested,

nicotine induced increased expression of SNHG5 and SNHG17 in A549

cells, indicating that they might be important in lung cancer

(Fig. 1A). RT-qPCR was performed

on lung cancer samples from smokers (n=50) and nonsmokers (n=50). A

comparison between tissues from nonsmokers and smokers showed a

marked enhancement of SNHG5 expression and no increase in SNHG17

expression (Fig. 1B). There were

no significant correlations of SNHG5 expression with age, sex, or

the lung cancer tissue differentiation level of patients. However,

SNHG5 expression level was correlated with tumor node metastasis

stage (P=0.039), distant metastasis (P=0.040), lymph node

metastasis (P=0.002), and smoking (P=0.0004; Table SIII). These results suggested that

SNHG5 might play an important role in smokers with lung cancer.

SNHG5 is associated with TRAIL

resistance in lung cancer

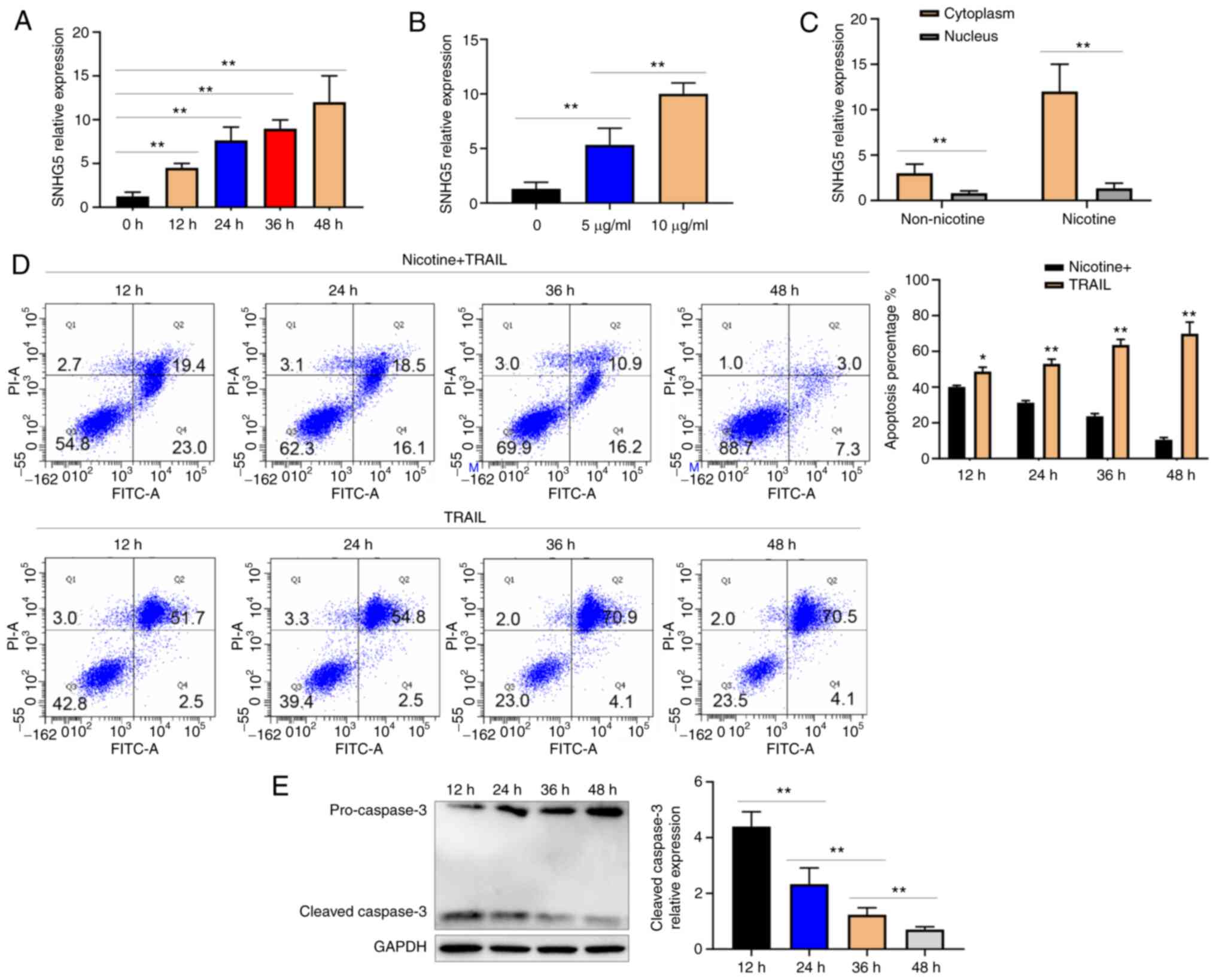

To further determine whether nicotine alters the

SNHG5 expression in vitro, the present study measured the SNHG5

expression following nicotine (10 µg/ml) induction in A549 cells at

different times. The cells were in good condition after nicotine

was applied. The results showed that SNHG5 expression increased

with nicotine induction in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The A549 cells were exposed to

different doses of nicotine (5 and 10 µg/ml) for 48 h. The SNHG5

expression increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Next, the SNHG5 expression in

the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of RNA of A549 cells exposed

to nicotine (10 µg/ml) for 48 h was quantified. It was found that

the SNHG5 upregulation was greater among cytoplasmic RNA than

nuclear RNA (Fig. 2C). Nicotine

(10 µg/ml) and TRAIL (1.6 µg/ml) were then added to A549 cells, and

flow cytometry was performed. Flow cytometry showed that the

apoptosis rate gradually decreased with increasing SNHG5

expression. The addition of TRAIL (1.6 µg/ml) alone to A549 cells

did not decrease the apoptosis rate (Fig. 2D). It was also found that the

expression of cleaved caspase-3 decreased with increasing SNHG5

expression, as detected by western blotting (Fig. 2E). The results showed that nicotine

promoted the expression of SNHG5 and SNHG5-induced TRAIL resistance

in lung cancer.

Knockdown of SNHG5 expression

decreases the TRAIL resistance in A549 and HCC827 cells

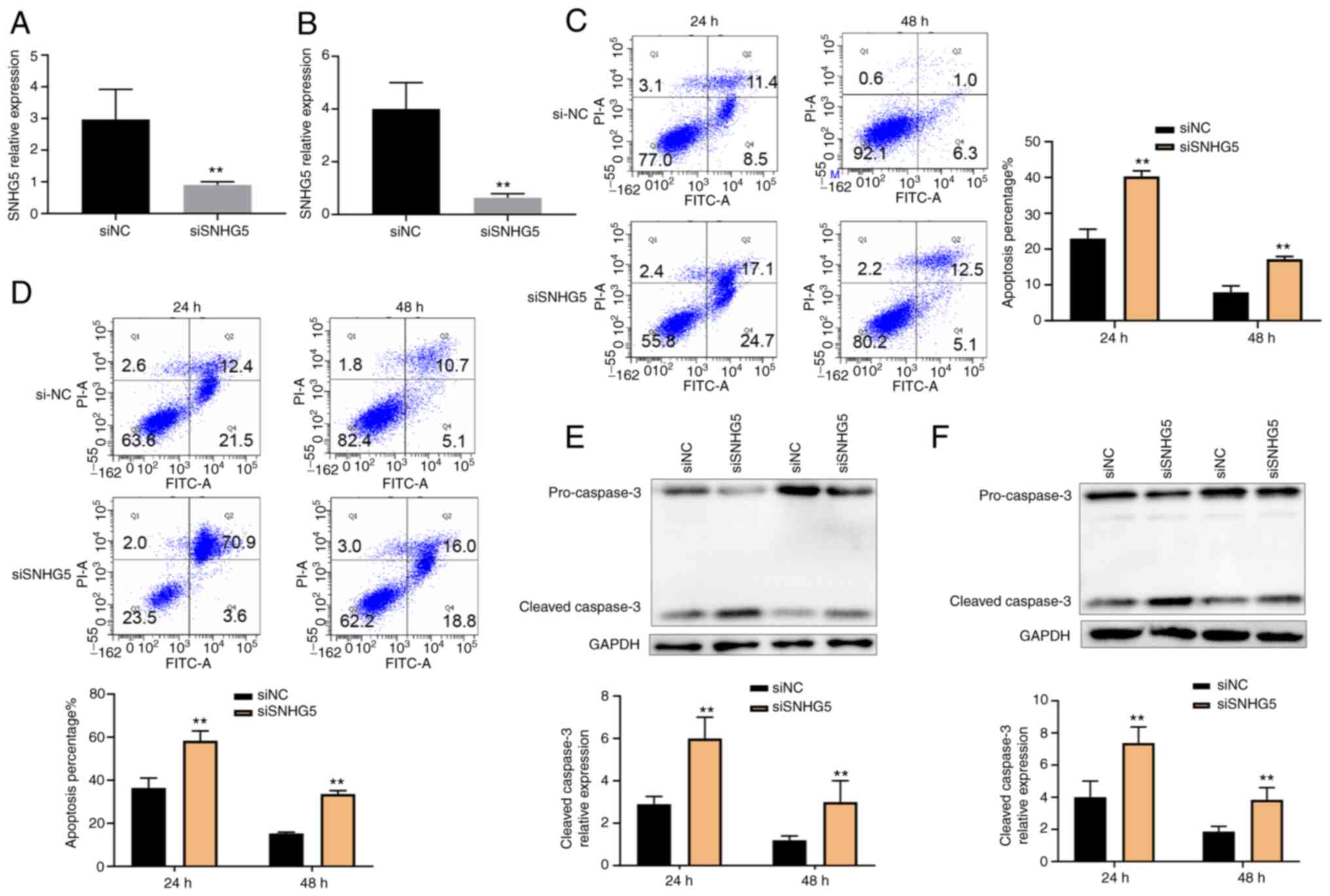

A549 and HCC827 cells were exposed to nicotine (10

µg/ml) and TRAIL (1.6 µg/ml). As shown in Fig. 3A and B, SNHG5 expression was significantly

knocked down in A549 and HCC827 cells by RT-qPCR of siRNA. The

siRNA sequences are presented in Table SI. SNHG5 knockdown resulted in a

markedly increased apoptosis rate in A549 and HCC827 cells as

measured by flow cytometry (Fig.

3C and D). Moreover, the

expression of cleaved caspase-3 was significantly increased with

decreasing SNHG5 expression (Fig.

3E and F). Collectively, these

data revealed a functional role of SNHG5 in TRAIL resistance.

SNHG5 overexpression increases TRAIL

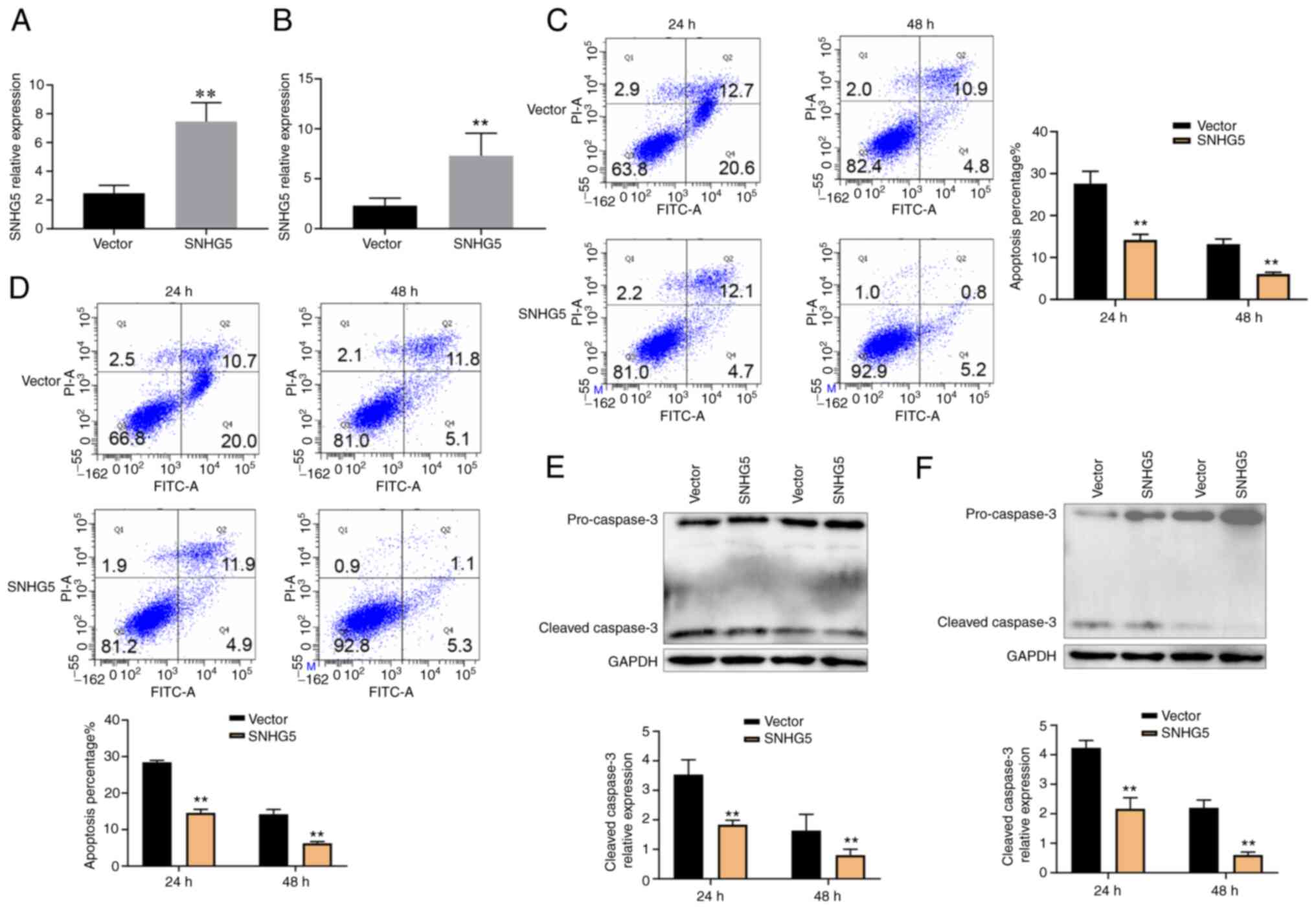

resistance in A549 and HCC827 cells

SNHG5 was overexpressed in A549 (Fig. 4A) and HCC827 (Fig. 4B) cells as revealed by RT-qPCR. The

cells were exposed to nicotine (10 µg/ml) and TRAIL (1.6 µg/ml) for

48 h. SNHG5 overexpression resulted in a significantly decreased

apoptosis rate in A549 and HCC827 cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 4C and D). The expression of cleaved caspase-3

decreased with increasing SNHG5 expression by western blotting

(Fig. 4E and F). Therefore, the results showed that

nicotine might promote SNHG5 overexpression, as well as suggested

an important role of SNHG5 in TRAIL resistance.

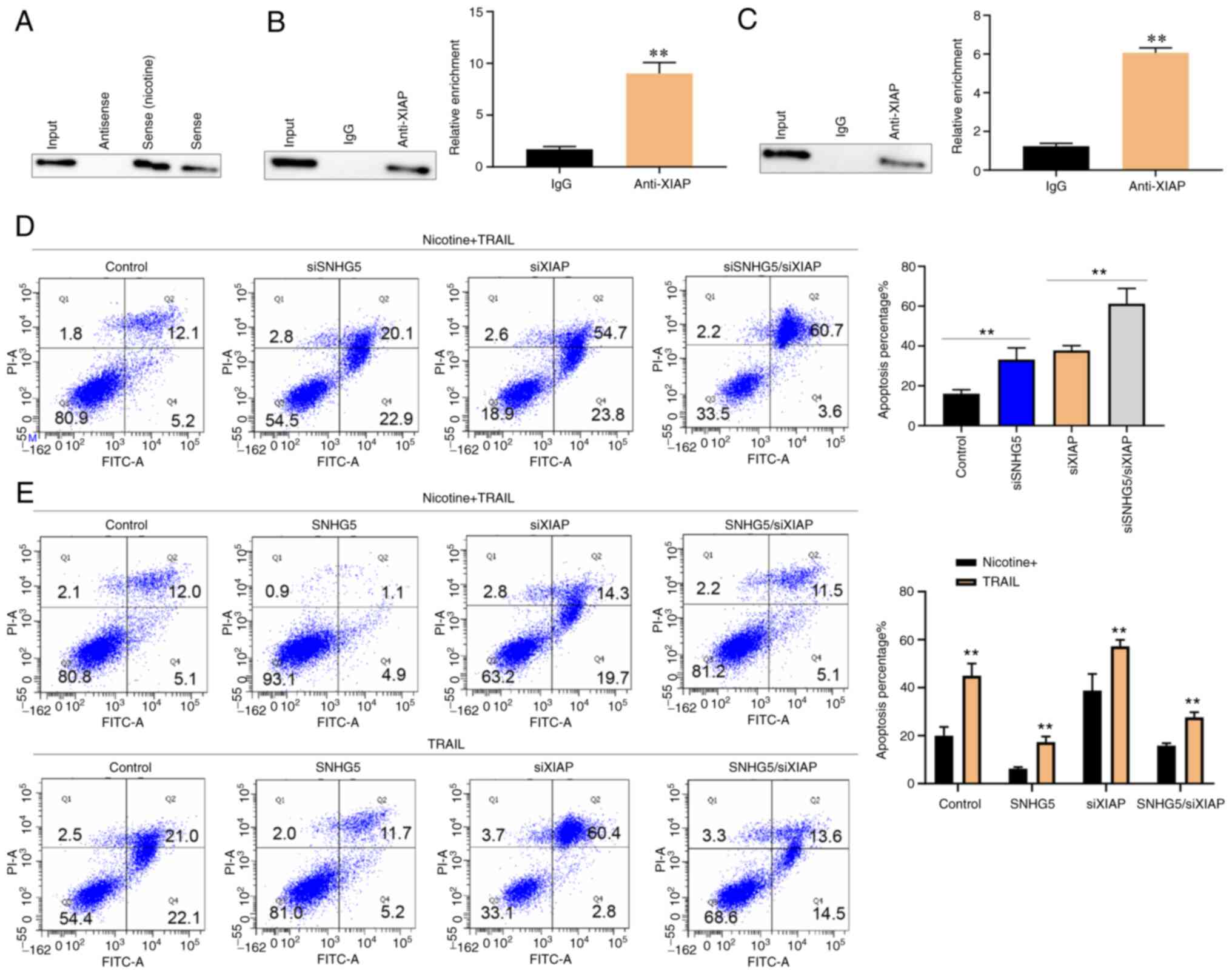

Cytoplasm SNHG5 directly interacts

with XIAP to regulate TRAIL resistance

The mechanistic insights into the mechanism and

interactions of SNHG5 were explored. As SNHG5 was simultaneously

located in the nucleus and cytoplasm, the possibility that SNHG5

functions by physically interacting with proteins was explored. A

biotinylated SNHG5 RNA pull-down assay and subsequent mass

spectrometry analysis of the differentially displayed bands

revealed that XIAP was the main protein bound to SNHG5. A number of

studies show that XIAP is involved in the apoptosis pathway

(12,13). The relationship between SNHG5 and

XIAP was studied using an immunoblot assay (Fig. 5A). RNA immunoprecipitation (UV-RIP)

assays with an XIAP-specific antibody confirmed a direct

interaction between SNHG5 and XIAP (Fig. 5B). Then, native RIP was performed

to confirm the binding between SHNG5 and XIAP (Fig. 5C). The interactive effects of SNHG5

and XIAP on the TRAIL resistance were evaluated using XIAP

knockdown in A549 cells. The cells were exposed to nicotine (10

µg/ml) and TRAIL (1.6 µg/ml) for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 5D, XIAP knockdown promoted A549 cell

apoptosis. In addition, apoptosis of SNHG5-knockdown A549 cells was

enhanced by XIAP knockdown. The TRAIL resistance in

SNHG5-overexpression A549 cells was rescued by XIAP siRNA with or

without nicotine treatment (Fig.

5E).

Discussion

In humans and other mammals, most small nucleolar

RNAs (snoRNAs) are located in the introns of protein-coding and

non-coding genes. Some previous studies assume that the host snoRNA

genes have no function and only carried the snoRNA-encoding

sequences in their introns. However, a number of SNHGs have been

found to play important roles in cancers (13-15).

The present study detected the SNHG expression in A549 cells

exposed to nicotine and found that SNHG5 expression was

significantly increased by nicotine treatment. The alterations

suggested that SNHG5 overexpression might be associated with

nicotine. The present study also found that SNHG5 expression was

significantly higher in lung cancer tissues from smokers compared

with those from nonsmokers. The results suggested that SNHG5

expression was related to important cell behaviors in lung cancer.

The present study also found that SNHG5 overexpression due to

nicotine treatment was associated with TRAIL resistance in lung

cancer. Tobacco nicotine plays a role in cancer drug resistance and

can inhibit cancer cell apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs

via increasing XIAP expression (16). Nicotine can suppress apoptosis by

inducing multi-site Bad phosphorylation (17); it can also activate Akt in a dose-

and time-dependent manner. Akt inhibitors can lead to a mild

reduction in chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, and the effects from

nicotine are blocked in A549 cells (18).

In the present study, SNHG5 directly interacted with

XIAP, which promoted TRAIL resistance by inhibiting the cleaved

caspase-3 expression in A549 and HCC827 cells. XIAP can bind

caspase-3 to suppress apoptosis (19-21).

The activity of processed caspases can be inhibited by XIAP, which

increases the threshold of apoptosis activation. Proapoptotic

factors, which are released from mitochondria, can inhibit XIAP.

The proapoptotic factors SMAC/DIABLO can bind and prevent XIAP

activity (22). High levels of

XIAP can explain inducible melanoma TRAIL resistance. SMAC is

released from the mitochondria and inhibits apoptosis by XIAP

(23). XIAP inhibitors promote

TRAIL-induced apoptosis and counter tumors in pancreatic cancer

(24,25). The present study showed that SNHG5

promoted TRAIL resistance, which explains the association with XIAP

in lung cancer. The results have significant implications regarding

our understanding of the roles of SNHG5.

SNHG5 was evidently increased in lung cancer cells

treated with nicotine. Tobacco nicotine induced SNHG5 expression

and promoted TRAIL resistance through SNHG5/XIAP. How SNHG5 and

XIAP to combine needs further detection. The present study provided

a new strategy to allow the use of TRAIL as a cancer treatment. A

small clinic sample size is the limitation of the present study.

Animal experiments are also required.

Supplementary Material

siRNA sequences.

Primers sequences.

Association between SNHG5 expression

and pathological features in 100 patients with lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Anhui

Medical University Project Fund (grant no. 2021xkj188).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed in the present

study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

XX, JX and XS collected and analyzed the data and

drafted the manuscript. XX and XS designed the project. CW, JD and

XS revised the manuscript. XX, JX, XS, CW and JD confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by

the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University (approval no.

202104001).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Akhtar N and Bansal JG: Risk factors of

lung cancer in nonsmoker. Curr Probl Cancer. 41:328–339.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D and Boshoff C:

The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature.

553:446–454. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL,

Kwon R, Curran WJ Jr, Wu YL and Paz-Ares L: Lung cancer: Current

therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 389:299–311.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Deng D and Shah K: TRAIL of hope meeting

resistance in cancer. Trends Cancer. 6:989–1001. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Middleton G, Fletcher P, Popat S, Savage

J, Summers Y, Greystoke A, Gilligan D, Cave J, O'Rourke N, Brewster

A, et al: The National lung matrix trial of personalized therapy in

lung cancer. Nature. 583:807–812. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McConnell DD, Carr SB and Litofsky NS:

Potential effects of nicotine on glioblastoma and

chemoradiotherapy: A review. Expert Rev Neurother. 19:545–555.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Cheng FJ, Chen CH, Tsai WC, Wang BW, Yu

MC, Hsia TC, Wei YL, Hsiao YC, Hu DW, Ho CY, et al: Cigarette

smoke-induced LKB1/AMPK pathway deficiency reduces EGFR TKI

sensitivity in NSCLC. Oncogene. 40:1162–1175. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liang WC, Ren JL, Wong CW, Chan SO, Waye

MM, Fu WM and Zhang JF: LncRNA-NEF antagonized epithelial to

mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis via cis-regulating

FOXA2 and inactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Oncogene.

37:1445–1456. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu MY, Li XQ, Gao TH, Cui Y, Ma N, Zhou Y

and Zhang GJ: Elevated HOTAIR expression associated with cisplatin

resistance in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Dis.

8:3314–3322. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yang Z, Li Q, Zheng X and Xie L: Long

Noncoding RNA small nucleolar host gene: A potential therapeutic

target in urological cancers. Front Oncol.

11(638721)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tu H and Costa M: XIAP's profile in human

cancer. Biomolecules. 10(1493)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zimta AA, Tigu AB, Braicu C, Stefan C,

Ionescu C and Berindan-Neagoe I: An emerging class of long

Non-coding RNA with oncogenic role arises from the snoRNA host

genes. Front Oncol. 10(389)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Qin Y, Sun W, Wang Z, Dong W, He L, Zhang

T and Zhang H: Long Non-Coding small nucleolar RNA host genes

(SNHGs) in endocrine-related cancers. Onco Targets Ther.

13:7699–7717. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yang T and Shen J: Small nucleolar RNAs

and SNHGs in the intestinal mucosal barrier: Emerging insights and

current roles. J Adv Res: Jun 11, 2022 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

16

|

Dasgupta P, Kinkade R, Joshi B, Decook C,

Haura E and Chellappan S: Nicotine inhibits apoptosis induced by

chemotherapeutic drugs by up-regulating XIAP and survivin. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:6332–6337. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jin Z, Gao F, Flagg T and Deng X: Nicotine

induces multi-site phosphorylation of Bad in association with

suppression of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 279:23837–23844.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhang J, Kamdar O, Le W, Rosen GD and

Upadhyay D: Nicotine induces resistance to chemotherapy by

modulating mitochondrial signaling in lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell

Mol Biol. 40:135–146. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R,

Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, Liddington RC and Salvesen GS: Structural

basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell. 104:791–800.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Von Karstedt S, Montinaro A and Walczak H:

Exploring the TRAILs less travelled: TRAIL in cancer biology and

therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 17:352–366. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Jost PJ, Grabow S, Gray D, McKenzie MD,

Nachbur U, Huang DC, Bouillet P, Thomas HE, Borner C, Silke J, et

al: XIAP discriminates between type I and type II FAS-induced

apoptosis. Nature. 460:1035–1039. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jost PJ and Vucic D: Regulation of cell

death and immunity by XIAP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

12(a036426)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Eberle J: Countering TRAIL resistance in

melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 11(656)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vogler M, Walczak H, Stadel D, Haas TL,

Genze F, Jovanovic M, Bhanot U, Hasel C, Möller P, Gschwend JE, et

al: Small molecule XIAP inhibitors enhance TRAIL-induced apoptosis

and antitumor activity in preclinical models of pancreatic

carcinoma. Cancer Res. 69:2425–2434. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Stadel D, Mohr A, Ref C, MacFarlane M,

Zhou S, Humphreys R, Bachem M, Cohen G, Möller P, Zwacka RM, et al:

TRAIL-induced apoptosis is preferentially mediated via TRAIL

receptor 1 in pancreatic carcinoma cells and profoundly enhanced by

XIAP inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 16:5734–5749. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|