Introduction

Parkinsonism is a neurological syndrome and is

divided into primary and secondary parkinsonism. Primary

parkinsonism is caused by neurodegenerative disease and secondary

parkinsonism can be caused by a variety of factors, such as drugs,

vascular disease, toxicity, infection, and autoimmune, neoplastic,

metabolic, and functional diseases (1). The clinical symptoms are motor and

nonmotor. It is characterized by motor symptoms, including tremors,

rigidity, bradykinesia, gait disorders, and akinesia, and nonmotor

symptoms, such as cognitive decline, depression, anxiety, sleep

disturbance, and dysautonomia (2,3).

Accurate diagnosis of Parkinson's disease (PD) and parkinsonism

remains challenging. Clinical symptoms and levodopa challenge tests

are important for differentiation. PD typically responds better to

levodopa than parkinsonism (4).

Among adults, meningiomas occur most frequently in

individuals aged 65 and above. Overall, these tumors are observed

2.3 times more often in women than in men. Meningiomas are usually

benign and develop slowly. They are the most prevalent type of

extraparenchymal brain tumors, accounting for approximately 40% of

all brain tumors (5). The initial

symptoms of meningiomas typically include headaches, focal

symptoms, and cranial nerve symptoms. Some patients are diagnosed

without clinical symptoms during routine medical examinations. The

occurrence of meningiomas becomes more frequent as people get older

(5). Although meningiomas can

exhibit a range of clinical symptoms, parkinsonism is an unusual

initial symptom. Tumoral parkinsonism is rare and is defined as

parkinsonism that develops as a direct or indirect result of

tumors, such as infiltration or compression (6).

In this report, we present an unusual case of

meningioma in which parkinsonism manifested as the primary clinical

symptom. We describe the patient's clinical course of treatment,

explore the underlying mechanism responsible for this occurrence,

and predict symptom improvement based on preoperative imaging

findings.

Case report

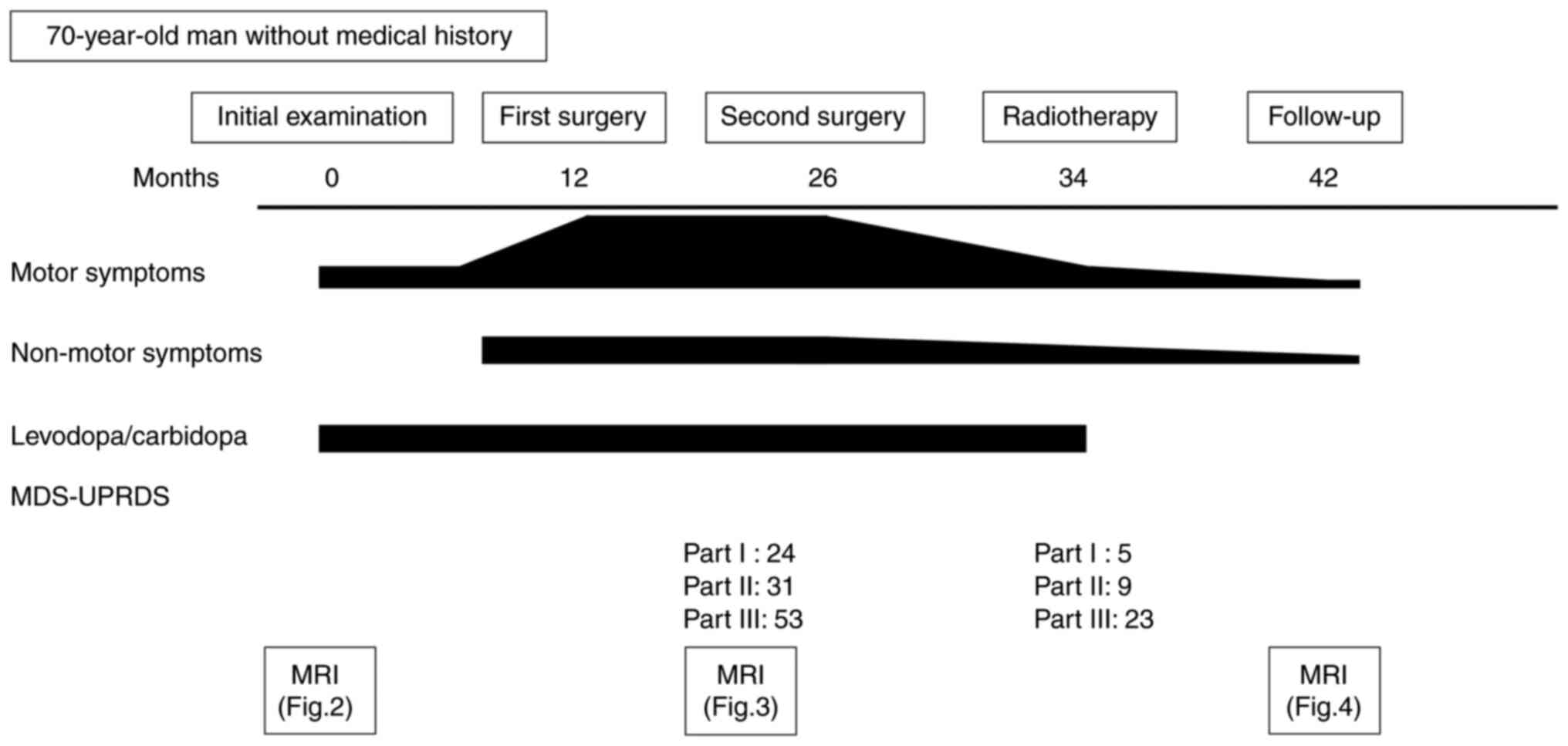

A 70-year-old man without a family history was

referred in November 2020 to the University of Occupational and

Environmental Health Hospital in Kitakyushu, Japan because of

involuntary movement 3 years prior to presentation. Examination

revealed resting tremors, pill-rolling tremors, and muscle rigidity

on the left side. Asymmetrical bradykinesia (left > right) and

mild postural instability were also observed. His eyeballs showed

no saccadic slowing or eye-movement limitations. Deep tendon

reflexes of the upper and lower extremities were normal. He did not

experienced paralysis and non-motor symptoms such as sensory

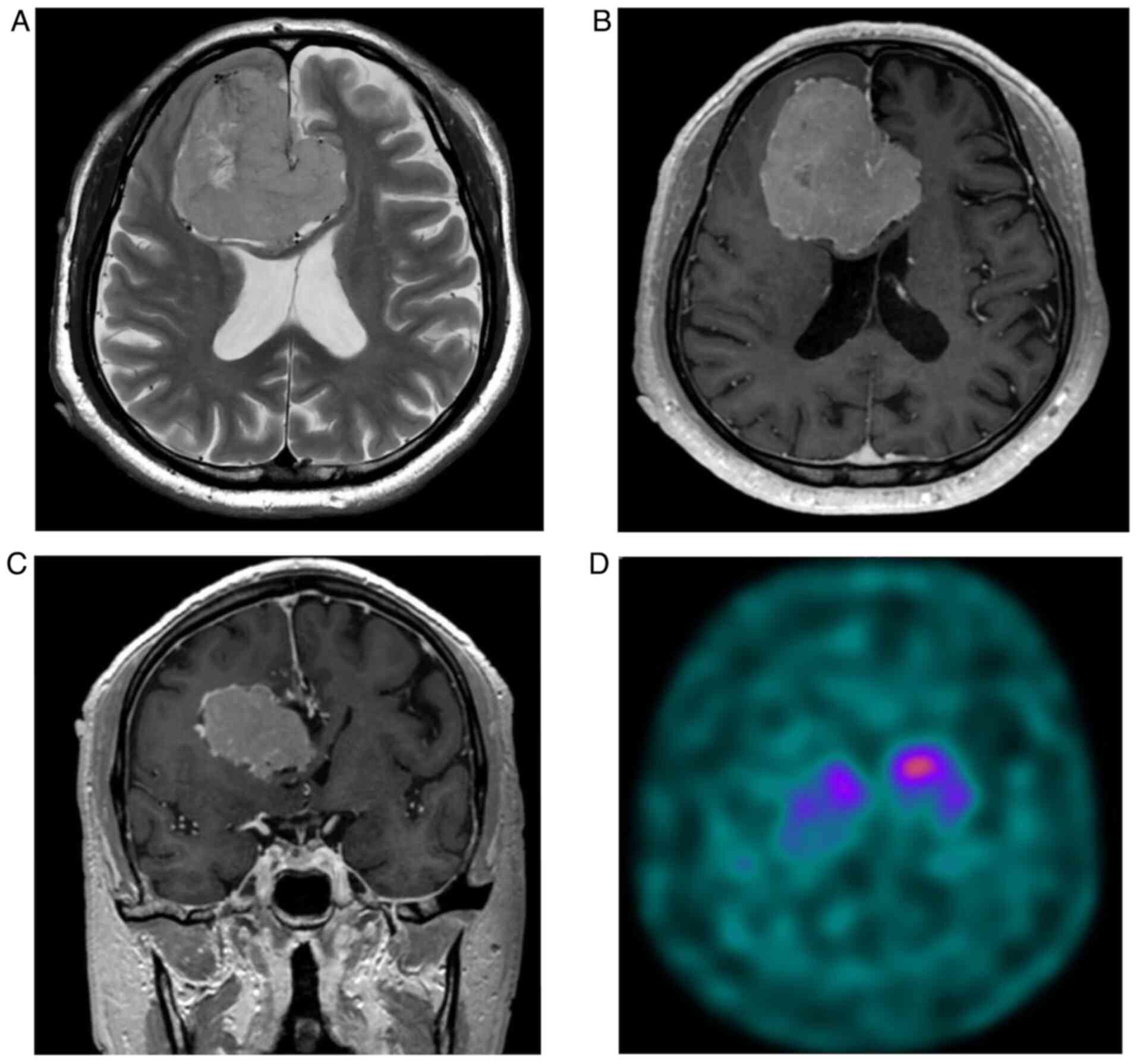

disorder, urinary incontinence, or cognitive decline (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

with T2-weighted images revealed dilated tortuous veins (Fig. 2A), and contrast-enhanced

T1-weighted imaging (CE-T1WI) revealed homogeneous enhancement of a

frontal lobe extra-axial giant lesion suggestive of a falx

meningioma (Fig. 2B and C). Dopamine transporter single-photon

emission computed tomography (DAT-SPECT) revealed decreased

123I-ioflupane uptake in the right striatum (Fig. 2D). Considering the diagnosis of PD

based on the DAT-SPECT findings, he was started on oral

levodopa/carbidopa. The patient refused surgery and was discharged

for frequent follow-up visits.

One year later, the patient continued to take

medication; however, his symptoms did not improve. Additionally,

his condition deteriorated, and he presented with urinary

incontinence, cognitive decline, and focal behavioral arrest

seizures. MRI with CE-T1WI revealed a growing tumor. The patient

subsequently underwent surgery. The tumor was removed using an

interhemispheric approach; however, it persisted due to

intraoperative blood loss. Pathological examination revealed the

proliferation of spindle or oval meningothelial cells, including

components arranged in fascicles or whorls, corresponding to a

transitional meningioma. The patient's symptoms did not improve

because the residual tumor compressed the right basal ganglia and

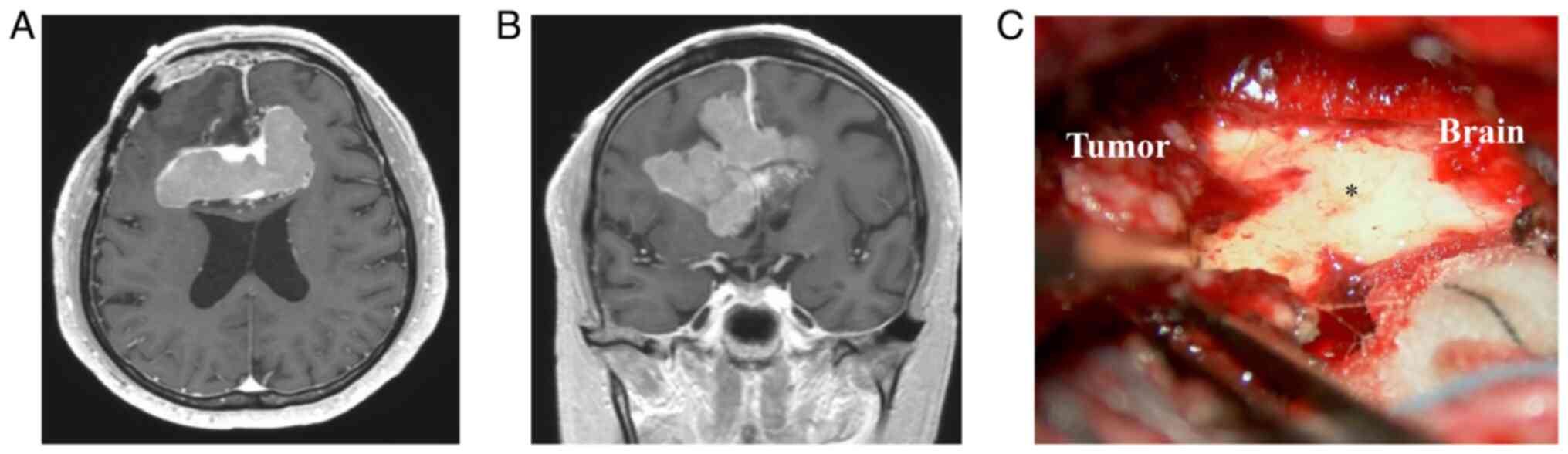

caused venous congestion. After 14 months, the residual tumor

enlarged. The Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson's Disease

Rating Scale (MDS-UPRDS) Part I score was 24. In brief, the patient

experienced non-motor symptoms of PD such as cognitive decline,

urinary incontinence, depression, and constipation. Parts II and

III had Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage 5 scores of 31 and 53,

respectively. MRI with CE-T1WI revealed a homogeneously enhanced

tumor (Fig. 3A and B). The patient then underwent surgery

again. The tumor was resected via an interhemispheric approach. The

interhemispheric fissure was identified by opening the dura mater

and the tumor, which was covered with a hard capsule. Although the

tumor was attached to the surrounding brain, the arachnoid membrane

was preserved in some areas (Fig.

3C). The pathology was similar to that observed after the

initial surgery, and the intraoperative findings showed no tumor

invasion of the brain. The patient did not develop any

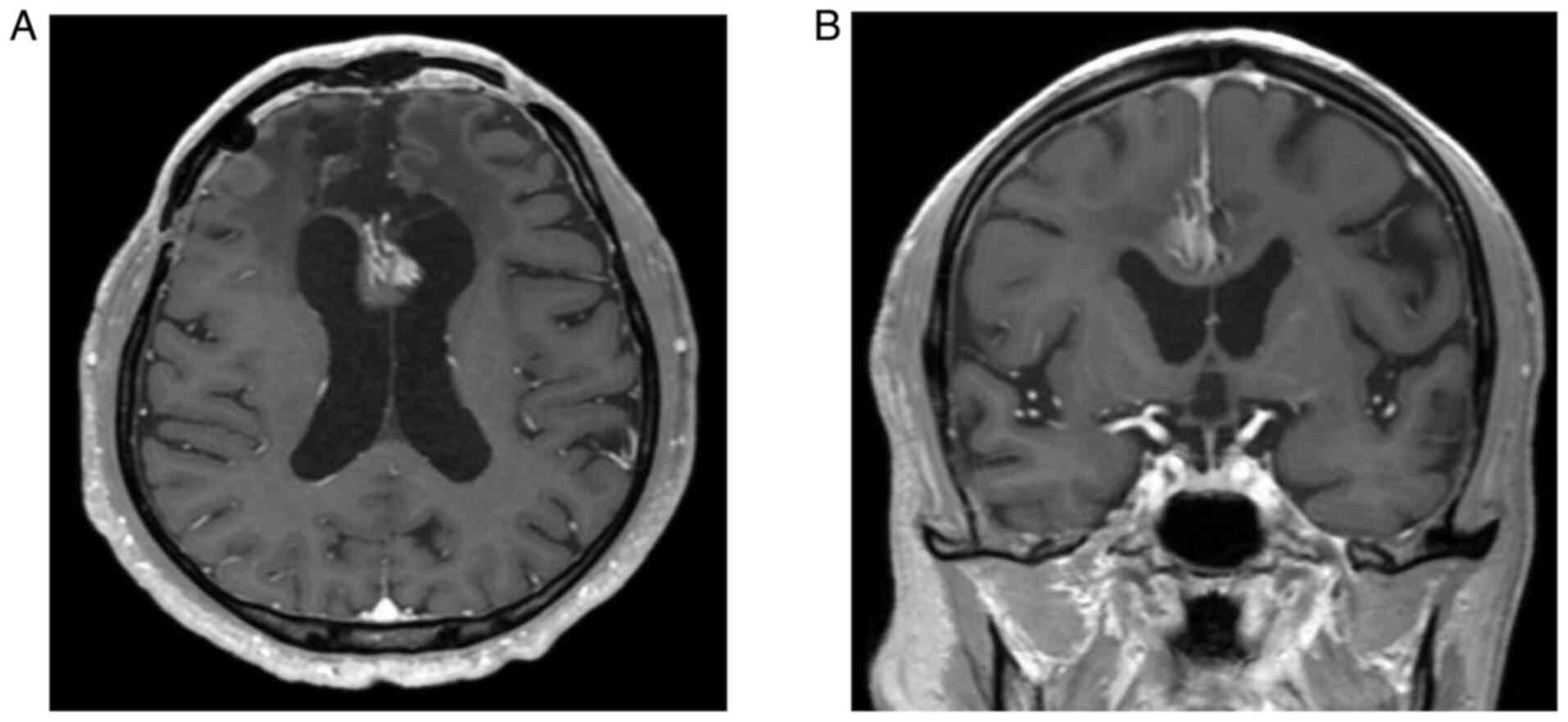

complications. Eight months later, the residual tumor had grown

slightly, and the patient underwent radiation therapy. The

MDS-UPRDS Part I score improved from 24 to 5. Overall, the

non-motor symptoms showed improvement, with the exception of minor

urinary incontinence and constipation. Parts II and III scored 9

and 23, respectively, as functions of H&Y stage 1. The patient

discontinued oral levodopa/carbidopa. Eight months later, an MRI

revealed a residual tumor; however, the basal ganglia were no

longer compressed (Fig. 4A and

B). The tumor was stable, and the

patient's symptoms did not change.

Discussion

Focal brain lesions can induce involuntary movement

disorders, such as hemichorea, hemiballism, dystonia, tremor,

myoclonus, parkinsonism, and asterixis (7). Cerebrovascular disease and stroke are

the major causes of this condition; however, other factors include

tumors, trauma, anoxia, and multiple sclerosis (7,8).

Parkinsonism has been observed in approximately 0.3% of patients

with supratentorial tumors, particularly those located in the

sphenoidal ridge or the frontal or parietal lobes (9). Brain tumors in the basal ganglia,

corpus callosum, periventricular white matter, midbrain, and

hypothalamus cause parkinsonism. Intraparenchymal tumors, such as

primary central nervous system lymphomas and gliomas, are

associated with parkinsonism (10,11).

Previous reports have described basal ganglia lymphoma-induced

parkinsonism, suggesting that tumor cell infiltration and damage to

neuronal membranes contribute to its development (11). Conversely, tumors with

extraparenchymal locations, such as meningiomas, may disrupt

neuronal circuits, including presynaptic dopaminergic neuronal

axons and the output pathway from the postsynaptic cells of the

basal ganglia circuit to the cortex. This disruption can result

from the mass effect of the tumor, leading to parkinsonism

(1). In tumor-associated

parkinsonism, DAT-SPECT may show decreased uptake due to tumor

invasion or compression (12,13).

In the present case, DAT SPECT revealed decreased

123I-ioflupane uptake in the right striatum.

Levodopa/carbidopa was administered for 1 year; however, symptoms

did not improve. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with

meningioma-associated parkinsonism.

We hypothesized that involuntary movements,

including parkinsonism, are associated with the following two

parallel pathways: the cortico-cerebellar-cortical pathway and the

dentato-rubro-olivary pathway (Guillain-Mollaret triangle)

(8). The

cortico-cerebellar-cortical pathway comprises major afferent and

efferent fibers. Afferent fibers extend from the frontal lobe to

the cerebellar cortex via the pons. In contrast, efferent fibers

extend from the dentate nucleus to the motor cortex via the red

nucleus and thalamus. The dentato-rubro-olivary pathway comprises

the inferior olivary nucleus (ION). Efferent fibers from the

dentate nucleus to the contralateral red nucleus, red nucleus to

the ipsilateral ION, and ION to the contralateral cerebellum form a

triangular circuit that governs motor activity. Both basal ganglia

and cerebellar circuits function as subcortical loops that receive

and return cortical information. Brain tumors can influence the

output pathway of the basal ganglia circuit from the postsynaptic

cells to the cortex. These pathways may be infiltrated and

compressed by tumors (8). It is

often difficult to alleviate symptoms when tumor infiltration is

involved; however, meningiomas are more prone to mechanical

compression than infiltration into the basal ganglia circuit and

show improvement after surgery. Involuntary movements in meningioma

are rare. Since 2010, to our knowledge, involuntary movements in

seven meningioma cases improved after surgery (Table I) (1,14-19).

The mean age at diagnosis was 54.9 years (range, 41-67 years), and

all patients were female. Several clinical symptoms have been

reported previously. Six patients presented with tremors, followed

by parkinsonism in five patients. Two of the five patients received

levodopa but responded poorly. All patients demonstrated laterality

of clinical symptoms as opposed to tumor location; however, only

one patient had a tumor located in the bifrontal region. Four

tumors were located in the sphenoid ridge, followed by the frontal

lobe and midbrain. The meningiomas were removed in all patients,

and the symptoms included involuntary movements due to compression,

which improved postoperatively. Only seven cases of involuntary

movement in meningiomas have been reported in the literature.

Involuntary movements in patients with tumors may mimic these

symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis. Clinical features are not well

known; however, for tremors and parkinsonism, especially when there

are laterality symptoms and opposite to tumor location, clinicians

should suspect the risk of tumor-associated involuntary

movements.

| Table ISummary of involuntary movements in

patients treated for meningioma since 2010. |

Table I

Summary of involuntary movements in

patients treated for meningioma since 2010.

| First author,

year | Case | Age, years/sex | Clinical

symptoms | Tumor location | Laterality | Treatment | Prognosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Diyora, 2014 | 1 | 50/F | Headache, dystonic

head tremor, resting tremor | Lt. sphenoid

ridge | Right | Surgery | Improved | (14) |

| Kim, 2014 | 2 | 58/F | Resting tremor,

bradykinesia, gait disorder | Lt. sphenoid

ridge | Right | Surgery | Improved | (1) |

| Kleib, 2016 | 3 | 41/F | Resting tremor,

bradykinesia, rigidity, paralysis | Lt. sphenoid

ridge | Right | Surgery | Improved | (15) |

| Fong, 2016 | 4 | 58/F | Hypomimic face,

hypophonic speech, gait disorder, resting pill-rolling tremor,

rigidity, bradykinesia | Lt. frontal

tumor | Right | Surgery | Improved | (16) |

| Labate, 2018 | 5 | 67/F | Ataxia, hypotension,

urinary incontinence, hyperreflexia, gait disorder, bradykinesia,

rigidity, postural and resting tremor | Lt. midbrain | Both | Surgery | Improved | (17) |

| Al-Janabi, 2019 | 6 | 65/F | Resting tremor,

bradykinesia, rigidity | Bil. anterior cranial

fossa | Right | Surgery | Improved | (18) |

| Inoue, 2021 | 7 | 45/F | Hemichorea | Rt. sphenoid

ridge | Left | Surgery | Improved | (19) |

| Present study | 8 | 70/M | Tremor, pill-rolling

tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, postural instability | Bil. anterior cranial

fossa | Left | Surgery | Improved | - |

In our cases, the patient showed laterality of

parkinsonism. The first surgery slightly improved the mechanical

compression but did not improve the parkinsonism because the venous

congestion did not improve; however, the second surgery improved

symptoms by relieving the compression of the basal ganglia and

venous congestion. Previous reports have focused on mechanical

compression caused by meningiomas, and the fact that the symptoms

did not improve after the first surgery, even though the mechanical

compression was relieved, may be due to cortical damage from venous

congestion. Considering tumors associated with parkinsonism is

important when clinicians suspect the laterality of parkinsonism.

Tumor removal decompresses the basal ganglia, resulting in the

improvement of parkinsonism, especially in meningiomas.

In conclusion, various pathogeneses, including

trauma, drug-induced cerebrovascular disorders, and brain tumors

can cause parkinsonism. This report presents a rare case of

meningioma presenting with parkinsonism as an initial manifestation

in an older adult. Parkinsonism is related to the

cortico-cerebellar-cortical pathway and the Guillain-Mollaret

triangle. Therefore, parkinsonism is rare in both intraparenchymal

and extraparenchymal tumors, however, parkinsonism caused by tumor

compression or venous congestion is more easily ameliorated than

that caused by tumor cell infiltration. Parkinsonism in patients

with brain tumors, particularly meningiomas, can be reversed with

surgical treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ST and SN drafted the manuscript and wrote the final

draft. KS, KF and JY revised the manuscript and provided

constructive feedback. SN and JY performed the surgeries. ST, KF,

KS and SN analyzed all the images. SN, KF and JY confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of the case details and associated

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kim J-I, Choi JK, Lee J-W and Hong JY:

Intracranial meningioma-induced parkinsonism. J Lifestyle Med.

4:101–103. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hayes MT: Parkinson's disease and

parkinsonism. Am J Med. 132:802–807. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tolosa E, Garrido A, Scholz SW and Poewe

W: Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Lancet

Neurol. 20:385–397. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sveinbjornsdottir S: The clinical symptoms

of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 139 (Suppl):318–324.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G,

Waite KA, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical

report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors

diagnosed in the United States in 2015-2019. Neuro Oncol. 24

(Suppl):v1–v95. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cedergren Weber G, Timpka J, Rydelius A,

Bengzon J and Odin P: Tumoral parkinsonism-Parkinsonism secondary

to brain tumors, paraneoplastic syndromes, intracranial

malformations, or oncological intervention, and the effect of

dopaminergic treatment. Brain Behav. 13(e3151)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Defebvre L and Krystkowiak P: Movement

disorders and stroke. Rev Neurol (Paris). 172:483–487.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Choi S-M: Movement disorders following

cerebrovascular lesions in cerebellar circuits. J Mov Disord.

9:80–88. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Krauss JK, Paduch T, Mundinger F and

Seeger W: Parkinsonism and rest tremor secondary to supratentorial

tumours sparing the basal ganglia. Acta Neurochir. 133:22–29.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Choi K-H, Choi S-M, Nam T-S and Lee M-C:

Astrocytoma in the third ventricle and hypothalamus presenting with

parkinsonism. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 51:144–146. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Merrill S, Mauler DJ, Richter KR,

Raghunathan A, Leis JF and Mrugala MM: Parkinsonism as a late

presentation of lymphomatosis cerebri following high-dose

chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for primary

central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurol. 267:2239–2244.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Okano R, Suzuki K, Nakano Y and Yamamoto

J: Primary central nervous system lymphoma presenting with

Parkinsonism as an initial manifestation: A case report and

literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 14(95)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Rodriguez W, Fedorova M and Chand P:

Levodopa-responsive parkinsonian syndrome secondary to a

compressive craniopharyngioma: A case report. Cureus.

15(e35621)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Diyora B, Kukreja S and Sharma A: Cerebral

meningioma presenting as dystonic head tremor. Mov Disord.

29(40)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kleib AS, Sid'Ahmed E, Salihy SM,

Boukhrissi N, Diagana M and Soumaré O: Hemiparkinsonism secondary

to sphenoid wing meningioma. Neurochirurgie. 62:281–283.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fong M, Ghahreman A, Masters L and Huynh

W: Large intracranial meningioma masquerading as Parkinson's

disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 87(1251)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Labate A, Nisticò R, Cherubini A and

Quattrone A: Midbrain meningioma causing subacute parkinsonism.

Neurol Clin Pract. 8:166–168. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Al-Janabi WSA, Zaman I and Memon AB:

Secondary parkinsonism due to a large anterior cranial fossa

meningioma. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 6(001055)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Inoue H, Yamamura R, Yamada K, Hamasaki T,

Inoue N and Mukasa A: Hemichorea induced by a sphenoid ridge

meningioma. Surg Neurol Int. 12(201)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|