Introduction

The majority of cancer mortalities are caused by

metastasis. Hematogenous metastasis includes multiple steps. First,

invasive cancer cells escape from the primary site into nearby

blood vessels (intravasation) and disseminate around the body

through the host circulation. Following this, the circulating

cancer cells exit the vessels to cross the endothelia and invade

secondary organ tissue (extravasation), where they proliferate to

form metastases (1). It is vital

to elucidate the detailed processes of these steps to prevent

metastasis, however, at present, the molecular mechanisms

underlying each step remain poorly understood.

In order to invade surrounding tissues, invasive

cancer cells form invadopodia, the filamentous actin

(F-actin)-based membrane protrusions required for degradation of

the extracellular matrix (ECM) and migration through the tissues

(2–4). It has been reported that invadopodia

play an essential role in the intravasation of cancer cells from

the primary site into the blood vessels (5). However, the importance of invadopodia

formation in extravasation from the blood vessels into the target

organs during metastasis, remains poorly understood.

In patients with aggressive bladder cancer, the most

common site of hematogenous metastasis is the lungs (6). The circulating bladder cancer cells

exit the lung microvessels by transendothelial invasion, to enter

the lung tissue. The present study assessed whether invadopodia

formation is involved in extravasation by analyzing lung metastasis

of aggressive bladder cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cells, reagents and antibodies

A human invasive and high-grade bladder cancer cell

line, YTS-1, was provided by Dr H. Kakizaki (Yamagata University,

Yamagata, Japan). YTS-1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium

(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria) with

5% CO2 at 37°C. Primary human lung microvascular

endothelial cells (HMVEC-L) were purchased from Lonza

(Walkersville, MD, USA) and maintained in EGM-2MV medium (Lonza).

All biochemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless

otherwise noted. Anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody (clone,

EP1922Y) and anti-actin polyclonal antibody were purchased from

Epitomics Inc. (Burlingame, CA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich,

respectively.

Stable transfectants

YTS-1 cells with reduced expression of cortactin

were generated by short hairpin (sh) RNA technology as previously

described (7). An shRNA expression

plasmid was constructed using pBAsi-hU6 Neo DNA (Takara Bio, Inc.,

Shiga, Japan). The shRNA sequence for cortactin was: GATC

CGCACGAGTCACAGAGAGATCTGTGAAGCCACAGATG

GGATCTCTCTGTGACTCGTGCT TTTTTA, the small interfering (si) RNA

sequence for cortactin is underlined. A human non-targeting siRNA

sequence (Accell Control siRNA kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA) was used to prepare the control cells expressing

non-targeting shRNA. The shRNA expression plasmids (knockdown and

control constructs), together with pTK-HyB, were introduced into

YTS-1 cells in a 10:1 molar ratio using Lipofectamine 2000

(Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Drug-resistant

colonies were selected in the presence of 200 μg/ml hygromycin B.

Two knockdown clones (designated cortKD-1 and -2) were selected

based on the cortactin expression levels. cortKD-1 and -2, and one

control clone (designated YTS control), were used for the assays

described in this study.

Western blot analysis

Total lysates of cancer cells were prepared by

solubilization in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1%

Igepal CA-630, 150 mM NaCl and proteinase inhibitors. The lysates

were resolved by SDS-PAGE on an 8–16% gradient gel (Invitrogen Life

Technologies) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane.

Western blotting was performed using specific primary antibodies

and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Signals

were visualized using the ECL PLUS detection system (GE Healthcare,

Amersham, UK).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells seeded on coverslips were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with phosphate-buffered serum

(PBS) containing 0.1% saponin and 1% bovine serum albumin. Cells

were stained with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled phalloidin (Invitrogen

Life Technologies), together with the monoclonal antibody against

cortactin, and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody

(Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used for primary antibody

detection. Cell staining was examined under an Olympus IX-71

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and LSM 710

Laser Scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen,

Germany).

Gelatin zymography

Gelatin zymography was performed in a 10% Novex

Zymogram pre-cast SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen Life Technologies) in

the presence of 0.1% gelatin under nonreduced conditions. Cells

(1×106) in 2 ml RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS were placed

in a single well (6-well dish) and grown to 80% confluence. Cells

were washed with PBS and incubated with 2 ml Opti-MEM (Invitrogen

Life Technologies) for 24 h. Conditioned media were collected and

subjected to SDS-PAGE. Gels were washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30

min at room temperature to remove SDS and incubated at 37°C

overnight in substrate buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)

and 5 mM CaCl2. Following this, cells were stained with

0.5% Coomasie Brilliant Blue R-250 in 50% methanol and 10% acetic

acid for 1 h. The bands of matrix metalloprotease-2 (MMP-2) appear

as clear bands against dark background due to its gelatin

degradation activity.

Matrigel and transendothelial invasion

assays

The two invasion assays were performed using a

conventional Transwell system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

For the Matrigel invasion assay, the bottom surface of the upper

chamber filter (8-μm pore size) was coated with 100 μg/ml

fibronectin and the top surface was covered with 1 mg/ml Matrigel

matrix (BD Biosciences). The lower chamber was filled with

serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. Bladder cancer cells

(5×104) were labeled with the Vybrant CFDA-SE Cell

Tracer kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and placed in the upper

chamber. Following incubation at 37°C for 24 h, non-migrated cells

remaining at the top surface of the filter were carefully removed

with cotton swabs. Migrated cells on the bottom surface were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde and counted under a fluorescence

microscope (Olympus IX-71). For transendothelial invasion assay,

HMVEC-L cells (1×105) were placed onto a collagen

I-coated upper chamber (8-μm pore size) and cultured over 2 days to

form a monolayer. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl

ester-labeled bladder cancer cells were re-suspended in EGM-2MV

medium and cells (5×104) were added onto the HMVEC-L

monolayer. Following incubation at 37°C for 24 h, non-migrated

cells were removed and migrated cells were fixed and counted.

Lung metastasis assay in nude mice

Bladder cancer cells (2×106) were

suspended in 0.1 ml serum-free RPMI-1640 medium and injected into

the tail vein of 6- to 8-week-old nude mice (BALB/cAJcI-nu/nu; Clea

Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After 3 weeks, lungs were harvested and

fixed with formalin. The left lung was removed and trisected. The

lung blocks were cut further into 4-μm sections and stained with

hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Lung metastatic foci were identified by

HE staining based on the histopathological findings, for example

abnormally high cell density and atypical nuclear morphology. The

degree of metastasis was evaluated by the proportion (%) of the

tumor area occupying the total lung area of the section. Images of

the lung were captured with a scanner (Epson Perfection 4990;

Epson, Tokyo, Japan) and the proportion (%) of the metastasized

tumor area was calculated using DP2-BSW software (Olympus). The

experiments were approved by the committee for animal experiments

of Oyokyo Kidney Research Institute (Hirosaki Hospital, Hirosaki,

Japan).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 12.0 statistical program (SPSS, Chicago,

IL, USA) was used. Statistically significant differences were

determined using the Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

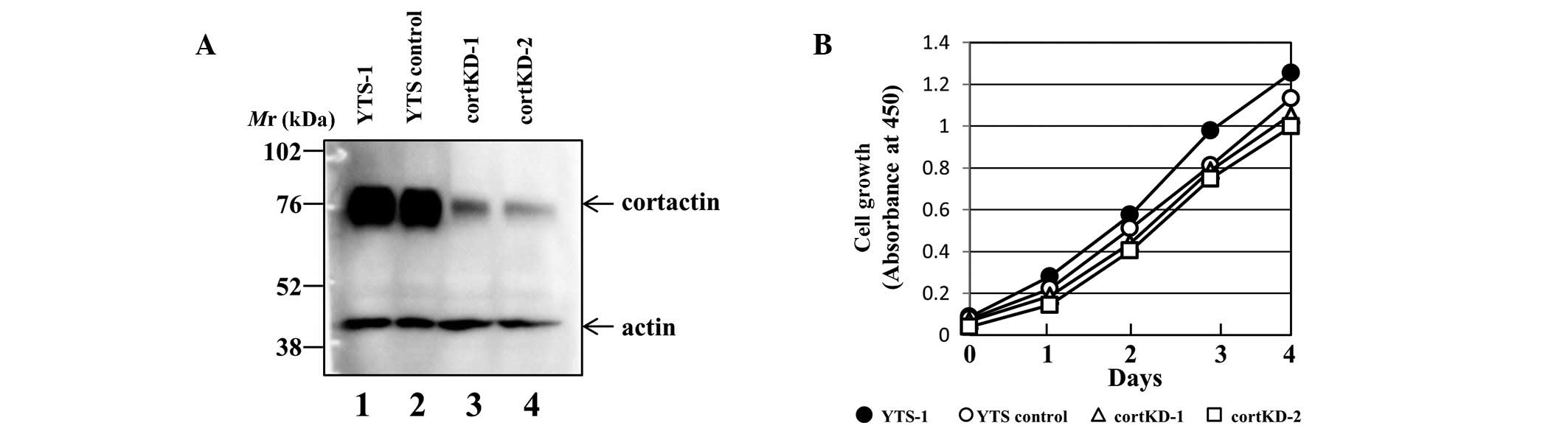

Establishment of cortactin knockdown

bladder cancer cells

To determine the contribution of invadopodia

formation to extravasation, the effect of a reduction of

invadopodia formation on cancer cell extravasation was analyzed. To

reduce invadopodia formation, the expression of cortactin in

invasive bladder cancer cells was silenced, as cortactin is an

invadopodium marker and one of the most important regulators for

invadopodia formation. Several stable cortactin knockdown cell

lines were established using an invasive bladder cancer cell line,

YTS-1. A YTS-1 cell line expressing non-targeting siRNA as a

control (designated YTS control) was also prepared. Western

blotting revealed that cortactin expression was reduced in two of

the knockdown cell lines (designated cortKD-1 and -2) compared with

parent YTS-1 and YTS controls (Fig.

1A). However, there was no significant difference in the growth

rate between these cell lines (Fig.

1B). The results from the assays using cortKD-1 are shown and

the two knockdown cell lines yielded almost identical results in

all assays.

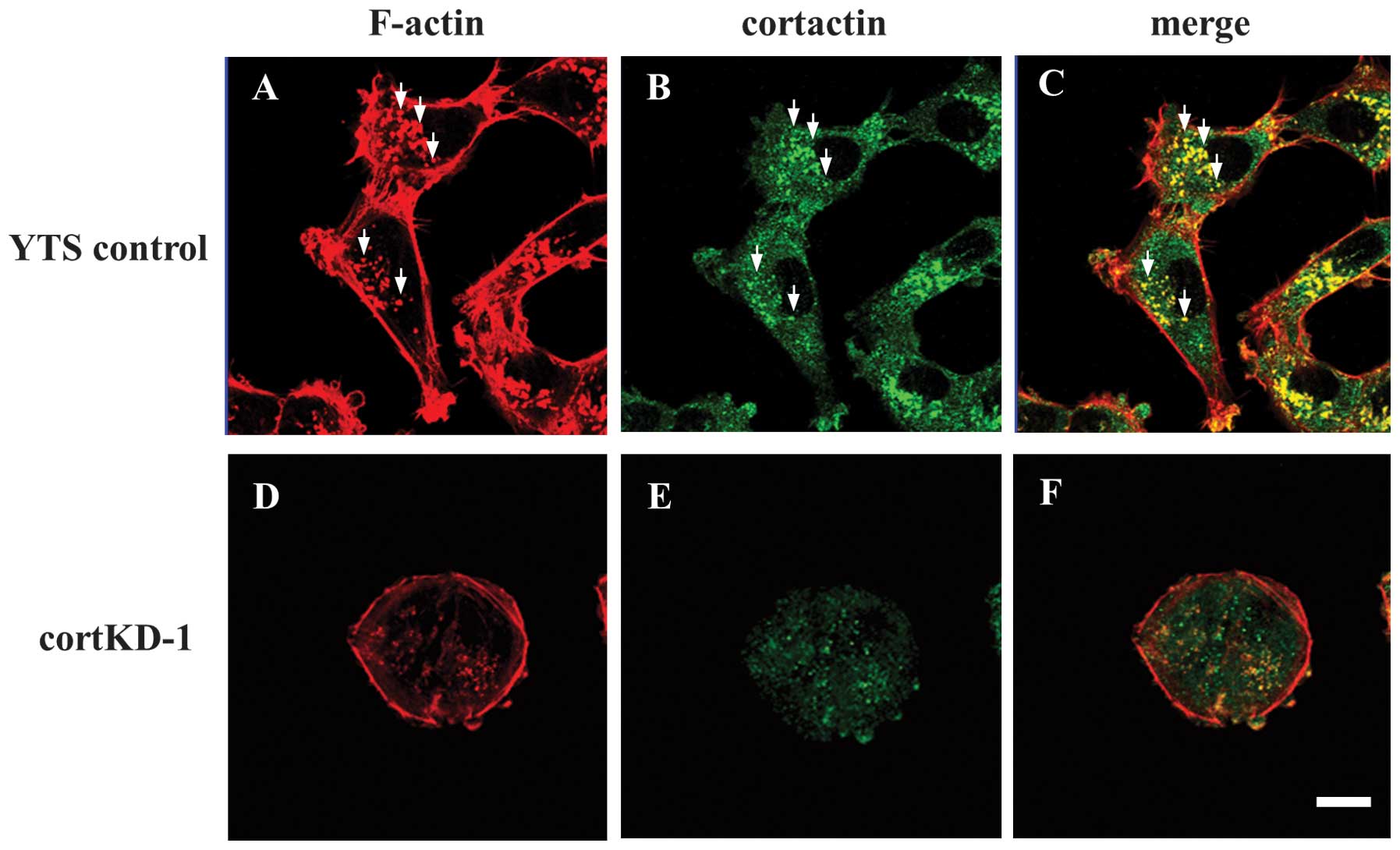

Reduction of invadopodia formation in

cortactin knockdown bladder cancer cells

Cortactin promotes invadopodia formation and

maturation in a number of cancer cells, and is also an invadopodium

marker (8–10). Cells were double-stained with

phallodin and anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody. Invadopodia in

YTS control cells were visualized by Alexa Fluor 568-labeled

phalloidin staining as F-actin-rich puncta (Fig. 2A). Several typical invadopodia were

indicated, as shown in Fig. 2A–C.

A portion of cortactin staining also exhibited a punctate pattern

(Fig. 2B) and co-localization of

cortactin with F-actin puncta indicated that the puncta were

invadopodia (Fig. 2C). In cortKD-1

cells, cortactin knockdown resulted in a marked cell-morphological

change to a round shape, and no invadopodia were observed (Fig. 2D–F). These results indicate that

invadopodia formation is impaired in cortactin knockdown bladder

cancer cells.

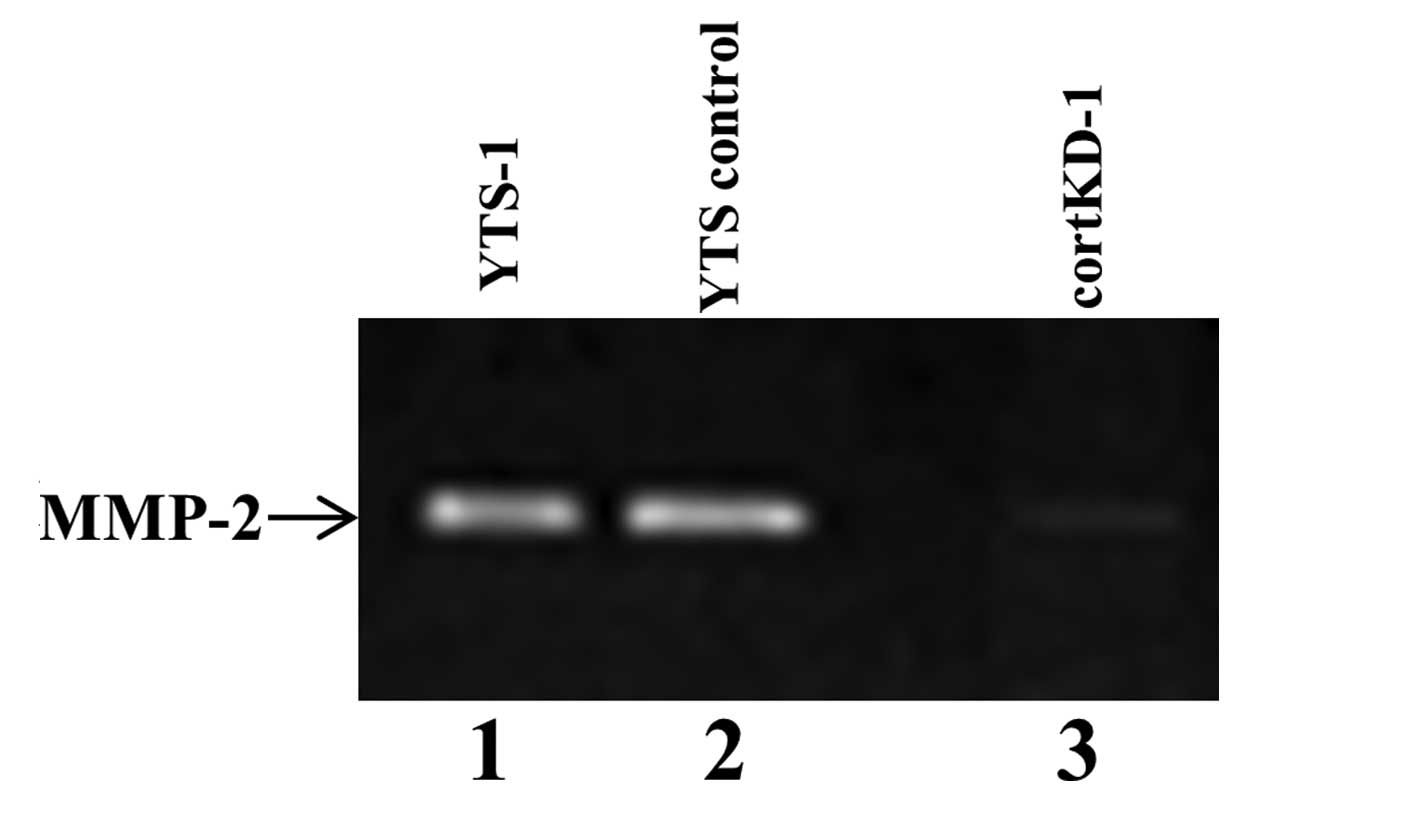

Reduced secretion of metalloproteinase in

cortactin knockdown cells

To examine if cortactin knockdown affects

invadopodia functions, the cells were assayed for the secretion of

matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, one of the most important

functions of invadopodia. Gelatin zymography revealed that large

amounts of MMP-2 were secreted by YTS-1 parent cells and YTS

control cells (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and

2). By contrast, the secretion of MMP-2 by cortactin knockdown was

markedly lower than that of YTS control cells (Fig. 3, lane 3), indicating that the

ability to secrete MMP-2 was markedly reduced in cortactin

knockdown cells.

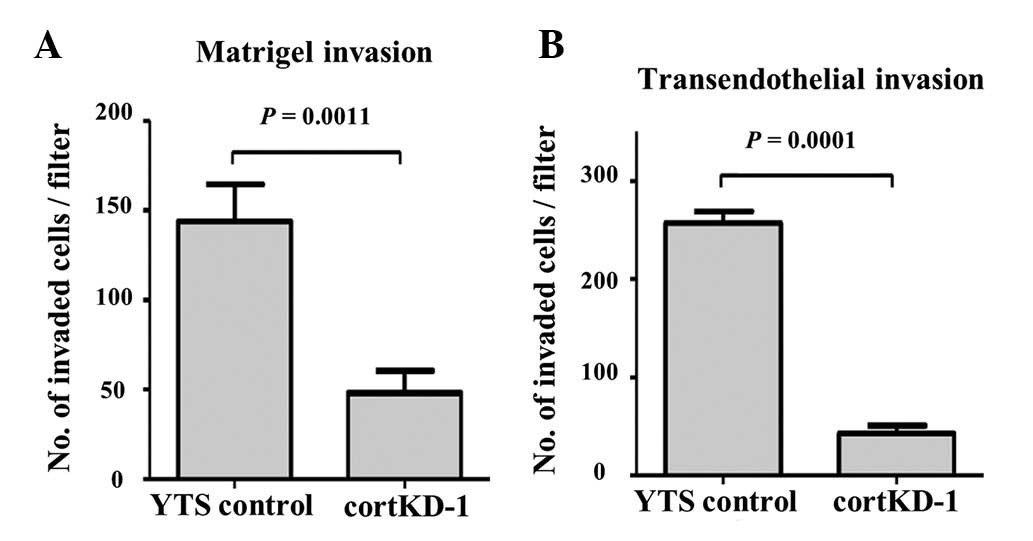

In vitro invasion capacity of cortactin

knockdown cells

Cortactin knockdown was found to impair invadopodia

formation and secretion of MMP-2 (Figs. 2 and 3). To examine whether defective formation

of invadopodia affects the invasion capacity of invasive cancer

cells, a Matrigel invasion assay was performed. cortKD-1 cells

exhibited a significantly lower invasion capacity through the

Matrigel matrix (Fig. 4A). This

result, taken together with Fig.

3, suggests that impaired invadopodia have a reduced capacity

to degrade and migrate through the ECM.

In order for bladder cancer cells to metastasize in

the lung, the cancer cells need to exit the circulation by

migrating through an endothelial monolayer of the lung

microvasculature. To determine the ability of cancer cells to

invade and migrate through a cellular endothelial barrier, the

transendothelial invasion capacity was measured. A transendothelial

invasion assay was performed, as previously described (11), in which cortKD-1 cells exhibited a

significantly lower transendothelial invasion capacity through the

endothelial monolayer of the lung microvascular vessels (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that

defective invadopodia formation by cortactin knockdown reduces the

invasion capacity through a Matrigel matrix and the endothelial

monolayer.

Tumor formation by cortactin knockdown

cells

To evaluate the role of invadopodia in cancer cell

extravasation for metastasis, the YTS control and cortKD-1 cells

were subjected to a lung metastasis assay, as this type of assay

closely mimics hematogenous metastasis (7,12).

Three weeks after cancer cell injection into mice, the lungs were

harvested and lung sections were examined for tumorous regions. A

large tumor area was observed on the lung section three weeks after

YTS control cells were injected (Fig.

5A). However, no tumor area was observed on the lung section

from the mice injected with cortKD-1 cells (Fig. 5B). When YTS control cells were

injected, all the mice exhibited lung metastases (n=6). By

contrast, none of the mice injected with cortKD-1 cells exhibited

detectable metastases (n=10) (Fig.

5C). The degree of metastasis of YTS control cells was 44.8%,

based on the proportion (%) of the tumor area occupying the total

lung area examined at lower magnification (x40; Fig. 5D). In order for invasive bladder

cancer cells to form metastatic foci in the lung, cancer cell

extravasation and proliferation in the lung are required. There was

no marked difference in the growth rate between YTS control and

cortKD-1 cells (Fig. 1B). However,

cortKD-1 cells exhibited a markedly lower degree of metastasis

compared with YTS control cells (Fig.

5). These results, taken together with the lower

transendothealial invasion capacity of cortKD-1 cells (Fig. 4B), suggests that the lower degree

of lung metastasis is due to reduced extravasation in the lung

tissues.

Discussion

Tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin by

non-receptor type tyrosine kinases, including Src and Arg, is a key

regulatory step for invadopodia formation (10,13,14).

It has been demonstrated that cortactin regulates invadopodia

formation in several types of cancer cell. Cortactin is also known

to regulate MMP secretion and matrix degradation, contributing to

the invasive character of cancer cells (15,16).

The present study demonstrated that cortactin plays a critical role

in invadopodia formation and MMP-2 secretion in invasive bladder

cancer cells (Figs. 2 and 3). Invadopodia formation regulated by

cortactin was also shown to be necessary for matrix degradation and

invasion by invasive bladder cancer cells (Fig. 4A).

Cancer cell extravasation is a decisive process for

metastasis whereby cancer cells exit the blood vessels to cross

endothelia and invade secondary organ tissues. Gligorijevi et

al previously demonstrated that invadopodia formation is

involved in cancer cell intravasation, using an in vivo

system (17). This study knocked

down the expression of neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

(N-WASP) in MTLn3 rat mammary gland adenocarcinoma cells. The

N-WASP knockdown MTLn3 cells demonstrated a markedly decreased

invadopodia formation, as N-WASP is an essential component of

invadopodia. When the N-WASP knockdown cells were implanted into

SCID mice, in vivo invadopodia formation and matrix

degradation were reduced in the area of intravasation. The present

study also demonstrated that invadopodia formation is involved in

cancer cell extravasation, using an in vivo system. The

invadopodia formation in invasive bladder cancer cells was reduced

by silencing cortactin, which is another essential component of

invadopodia. Subsequently, cortactin knockdown cells were subjected

to the in vivo tumor formation assay, which included cancer

cell extravasation. The lower rate of lung metastasis of cortKD-1

cells (Fig. 5) indicates that the

extravasation of cortKD-1 cells is impaired due to reduced

invadopodia formation.

In order for invasive cancer cells to extravasate,

the endothelial barrier surrounding blood vessels and the basement

membrane must be broken down (18). In the present study, perturbing the

function of cortactin by shRNA was found to reduce MMP-2 secretion,

invadopodia-mediated ECM degradation, transendothelial invasion and

in vivo tumor formation by invasive cancer cells. These

results indicate that cortactin-mediated invadopodia formation is

required for the invasion and extravasation process of bladder

cancer metastasis. In conclusion, the potential of cortactin as a

target for anti-invasion and anti-extravasation therapeutics should

be investigated further.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants-in-aid for

Scientific Research from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of

Science (nos. 22570131 and B22390301), the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (nos. 21791483 and

21791484) and Japan Science and Technology Agency (CREST).

References

|

1

|

Steeg PS: Tumor metastasis: mechanistic

insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 12:895–904. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Caldieri G, Ayala I, Attanasio F and

Buccione R: Cell and molecular biology of invadopodia. Int Rev Cell

Mol Biol. 275:1–34. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Linder S, Wiesner C and Himmel M:

Degrading devices: invadosomes in proteolytic cell invasion. Annu

Rev Cell Dev Biol. 27:185–211. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Murphy DA and Courtneidge SA: The ‘ins’

and ‘outs’ of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation

and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 12:413–426. 2011.

|

|

5

|

Yamaguchi H, Lorenz M, Kempiak S, et al:

Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the

N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J Cell Biol.

168:441–452. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Smith SC, Nicholson B, Nitz M, et al:

Profiling bladder cancer organ site-specific metastasis identifies

LAMC2 as a novel biomarker of hematogenous dissemination. Am J

Pathol. 174:371–379. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tsuboi S, Sutoh M, Hatakeyama S, et al: A

novel strategy for evasion of NK cell immunity by tumours

expressing core2 O-glycans. EMBO J. 30:3173–3185. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Artym VV, Zhang Y, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch

F, Yamada KM and Mueller SC: Dynamic interactions of cortactin and

membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase at invadopodia: defining

the stages of invadopodia formation and function. Cancer Res.

66:3034–3043. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ayala I, Baldassarre M, Giacchetti G, et

al: Multiple regulatory inputs converge on cortactin to control

invadopodia biogenesis and extracellular matrix degradation. J Cell

Sci. 121:369–378. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Oser M, Yamaguchi H, Mader CC, et al:

Cortactin regulates cofilin and N-WASp activities to control the

stages of invadopodium assembly and maturation. J Cell Biol.

186:571–587. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sugiyama N, Yoneyama MS, Hatakeyama S, et

al: In vivo selection of high-metastatic subline of bladder cancer

cell and its characterization. Oncol Res. 20:289–295. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hatakeyama S, Yamamoto H and Ohyama C:

Tumor formation assays. Methods Enzymol. 479:397–411. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mader CC, Oser M, Magalhaes MA, et al: An

EGFR-Src-Arg-cortactin pathway mediates functional maturation of

invadopodia and breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res.

71:1730–1741. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Oser M, Mader CC, Gil-Henn H, et al:

Specific tyrosine phosphorylation sites on cortactin regulate

Nck1-dependent actin polymerization in invadopodia. J Cell Sci.

123:3662–3673. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Clark ES and Weaver AM: A new role for

cortactin in invadopodia: regulation of protease secretion. Eur J

Cell Biol. 87:581–590. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kirkbride KC, Sung BH, Sinha S and Weaver

AM: Cortactin: a multifunctional regulator of cellular

invasiveness. Cell Adh Migr. 5:187–198. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gligorijevic B, Wyckoff J, Yamaguchi H,

Wang Y, Roussos ET and Condeelis J: N-WASP-mediated invadopodium

formation is involved in intravasation and lung metastasis of

mammary tumors. J Cell Sci. 125:724–734. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Al-Mehdi AB, Tozawa K, Fisher AB, Shientag

L, Lee A and Muschel RJ: Intravascular origin of metastasis from

the proliferation of endothelium-attached tumor cells: a new model

for metastasis. Nat Med. 6:100–102. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|