Introduction

The leaves of Perilla frutescens are commonly

used as decorative elements in Asia, including China, Japan and

Taiwan. Dried red Perilla leaves are also used as ‘soyou’ in

Chinese herbal medicine and are components of ‘saiboku-to’, which

is a Japanese herbal formula that is commonly used to treat asthma.

Previous studies have reported that Perilla frutescens leaf

extracts (PLE) display a range of biological activities, including

inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (1), suppression of IgA nephropathy

(2), and anti-inflammatory and

anti-allergic activity (3,4). However, the mechanisms underlying the

anti-inflammatory properties of PLE are not well understood.

Inflammation is a response of organisms to pathogens

and chemical or mechanical injury. Inflammatory response and tissue

damage are induced by inflammatory mediators generated through

upregulation of a number of inducible genes, including inducible

nitric oxide (iNOS), cyclooxygenase (COX)-2,

interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8. Nitric oxide (NO)

is a messenger molecule that has critical functions in vascular

regulation, host immune defense, neuronal signal transduction, and

other pathways (5–7). NO is produced from the conversion of

L-arginine to L-citrulline by the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in

the presence of oxygen and NADPH (8). NOS is inducible in macrophages and

hepatocytes, and is activated following infection (9). Therefore, inducible (i)NOS-derived NO

is an ubiquitous mediator of a wide range of inflammatory

conditions, and its expression level reflects the degree of

inflammation, thus providing a measure of the inflammatory response

(10,11). COX-2 also participates in immune

system modulation and is involved in pathophysiological events

(12). COX-2 is not expressed or

is slightly detectable in most tissues under normal conditions;

high expression of COX-2 following induction by pro-inflammatory

mediators such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is involved

in the pathogenesis of sepsis and inflammation (13,14).

In addition, compounds interfering with both iNOS and COX-2

generally act as inhibitors of a transcription factor required for

iNOS and COX-2 expression, nuclear factor (NF)-κB (15).

Macrophages play a crucial role in eliciting

NF-κB-related cascades at the acute phase of the inflammatory

response. LPS stimulation of mouse macrophages leads to increased

phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases

(MAPKs), such as extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2,

and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (16). Therefore, the development of

specific drugs to inhibit the production of these inflammatory

modulators may be effective in the treatment of inflammatory

diseases. In the present study, we investigated the

anti-inflammatory effects and the underlying mechanism of a P.

frutescens leaf extract (PLE). Specifically, we studied the

regulation of gene expression of iNOS, COX-2, and

pro-inflammatory cytokines in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with

LPS.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Aprotinin, leupeptin, LPS,

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide

(MTT), penicillin, streptomycin and other chemicals used in this

study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS)

and supplements for cell culture were purchased from Gibco-BRL

(Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Antibodies targeting phosphorylated Erk1/2

(p-Erk1/2), total Erk1/2 (t-Erk1/2), phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK),

total JNK (t-JNK), phosphorylated p38 (p-p38), total p38 (t-p38),

IκBα and NF-κB (p65 subunit) were purchased from Cell Signaling

Technologies (Beverly, MA, USA). The antibody targeting the

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies targeting mouse

and rabbit IgGs were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The

murine macrophage RAW264.7 cell line was obtained from the American

Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA).

Preparation of P. frutescens leaf extract

(PLE)

Perilla frutescens plants were purchased from

a certified herbal pharmacy (Chung-Yi Chinese Herbal Medicine

Pharmacy, Taichung, Taiwan). After dehydration, 100 g of the leaves

were homogenized, and the powder was passed through a mesh (0.05

mm). The filtered powder was resuspended into 1 liter of 100%

methanol and stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Following

filtration on a Whatman no. 1 filter paper, the solution was

lyophilized. Stock solution (20 mg/ml) of the extract was prepared

in dimethylsulfoxide, and stored at −20°C until further use.

Cell cultures and treatment

The RAW264.7 cells were incubated in DMEM

supplemented with 0.1% sodium bicarbonate, 2 mM glutamine,

penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and 10% FBS, and

were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5%

CO2. Following pre-incubation with different

concentrations of PLE for 4 h, 1 μg/ml LPS was added and then

incubated for 2 h (NO assay), 3 h (RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analysis), or

24 h (cell viability assay and cell morphology analyses).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by an assay based on

the mitochondrial-dependent reduction of MTT to formazan. Briefly,

10 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in DMEM) were added to the cell

supernatant and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After removal of the

medium, 2-propanol was added to lyse the cells and to solubilize

the formazan. The optical density of formazan was measured at 570

nm using a microplate reader (Benchmark; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Hercules, CA, USA). The optical density of formazan generated by

untreated cells was used to determine the 100% viability.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription

polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative (q)RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from individual samples,

according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using the RNeasy kit

(Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The purified RNA was used as a

template to generate cDNA using the RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA

Synthesis kit (Fermentas Life Sciences, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). The

primer sequences used for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are listed in Table I. RT-PCR experiments were performed

in triplicates for each sample. Amplifications were performed using

the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA, USA). For mRNA quantification, the FastStart

Universal SYBR-Green Master mix (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim,

Germany) was used. The cycle threshold (Ct) values were calculated

using the ΔΔCT method, and relative expression values were

expressed by normalizing to the expression of GAPDH. qRT-PCR

experiments were performed in duplicates for each sample. The size

of the PCR products was confirmed by agarose gel

electrophoresis.

| Table IPrimer sequences used for reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative

(q)RT-PCR. |

Table I

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative

(q)RT-PCR.

| Gene name | RT-PCR | qRT-PCR |

|---|

| IL-6 | F:

5′-ATGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGCGC-3′ | F:

5′-GTAGTGAGGAACAAGCCAGAGC-3′ |

| R:

5′-GAAGAGCCCTCAGGCTGGACTG-3′ | R:

5′-GGCATTTGTGGTTGGGTCA-3′ |

| IL-8 | F:

5′-AGATATTGCACGGGAGAA-3′ | F:

5′-CTCTTGGCAGCCTTCCTGATTT-3′ |

| R:

5′-GAAATAAAGGAGAAACCA-3′ | R:

5′-CGCAGTGTGGTCCACTCTCAAT-3′ |

| iNOS | F:

5′-CTGAGGGCTCTGTTGAGGTC-3′ | F:

5′-GGCAGCCTGTGAGACCTTTG-3′ |

| R:

5′-CCTTGTTCAGCTACGCCTTC-3′ | R:

5′-GCATTGGAAGTGAAGCGTTTC-3′ |

| COX2 | F:

5′-GGAGAGACTATCAAGATAGTGATC-3′ | F:

5′-CAGAACCGCATTGCCTCTG-3′ |

| R:

5′-ATGGTCAGTAGACCTTTACAGCTC-3′ | R:

5′-TTGTAACTTCTGGTCCTCATGTCGA-3′ |

| TNF-α | F:

5′-GCGACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAG-3′ | F:

5′-GACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT-3′ |

| R:

5′-TCCATGCCGTTGGCCAGGAGG-3′ | R:

5′-CCTCCACTTGGTGGTTTGCT-3′ |

| GAPDH | F:

5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ | F:

5′-ATGCCTCCTGCACCACCA-3′ |

| R:

5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ | R:

5′-CCATCACGCCACAGTTTCC-3′ |

NO assay

The NO level in cell culture supernatants was

determined using the Griess test. Briefly, cells were treated with

1, 5, or 15 μg/ml PLE for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1 μg/ml

LPS for 24 h. Nitrite in the culture supernatants was mixed with

the same volume of Griess reagent [1% sulfanilamide and 0.1%

N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 5% phosphoric

acid]. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm, and the nitrite

concentration was determined using sodium nitrite

(NaNO2) as a standard (17).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

To analyze the production of pro-inflammatory

mediators, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at an initial density

of 5×105 cells/ml, starved in serum-free medium for 16

h, pre-incubated with different concentrations of PLE (5, 10 and 20

μg/ml) for 1 h, then treated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 24 h. The

supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of IL-6, IL-8

and TNF-α, as well as of prostaglandin E2

(PGE2) were determined using DuoSet ELISA kits and the

Prostaglandin E2 Parameter Assay kit (R&D Systems,

Abingdon, UK) respectively, following the manufacturer’s

instructions.

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were washed with physiological saline and

incubated with lysis buffer [10 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, containing 15 mM

KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05%

v/v IGEPAL® CA-630, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

(PMSF), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 10 μg/ml

leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin] for 10 min. Following

centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was

transferred into a new Eppendorf tube, further centrifuged at

20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the new supernatant was collected

as the cytosolic fraction. The pellets containing the nuclei were

washed with physiological saline, incubated with a nucleus lysis

buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 0.1% v/v IGEPAL® CA-630, 1

M KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM

sodium fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin), and

then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting

supernatants were collected as the nuclear fraction.

Immunoblotting

Cells (5×105 cells/ml) were harvested,

washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and

lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v

IGEPAL® CA-630, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium fluoride, and 10

μg/ml aprotinin and leupeptin). The cell lysates were centrifuged

at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the debris. The

supernatants were collected and crude protein concentrations were

determined using the BCA™ protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL,

USA). Crude proteins (30 μg/lane) were electrophoresed and

transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA,

USA). After blocking with 5% w/v skimmed milk in PBS, the membrane

was incubated for 2 h with a 1/1,000 dilution of the specific

primary antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected using a 1/2,000

dilution of peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam) and

ECL chemiluminescence reagent (Millipore) as the substrate. Three

independent experiments were performed, and results were quantified

by densitometry.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation

(SD) of the mean from three independent experiments. Statistical

comparisons were performed by a one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA), followed by a Duncan multiple comparison test. Differences

were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

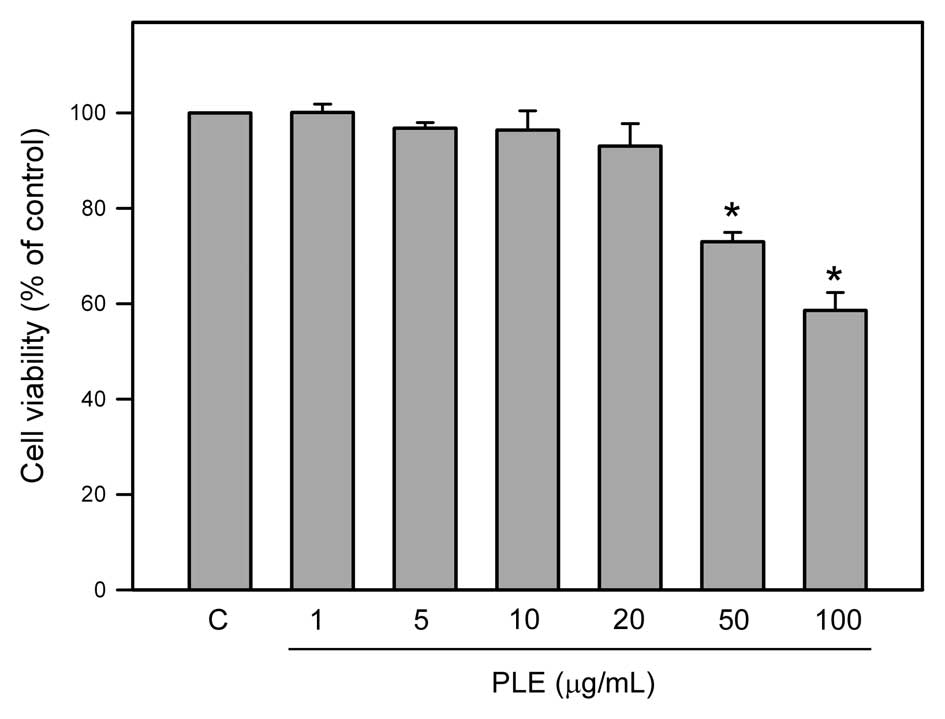

Effects of PLE on viability of murine

macrophage RAW264.7 cells

The cytotoxic effect of PLE on viability of RAW264.7

cells was investigated by the MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 1, the viability of RAW264.7 cells

was determined following incubation with different concentrations

(1, 5, 15, 30, 50 and 100 μg/ml) of PLE for 24 h. The results

revealed that treatment with concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/ml PLE

significantly decreased the viability of RAW264.7 cells (P<0.05)

compared to control (untreated) cells, while lower concentrations

(1, 5, 15 and 30 μg/ml) of PLE had no significant effect on

viability of RAW264.7 cells.

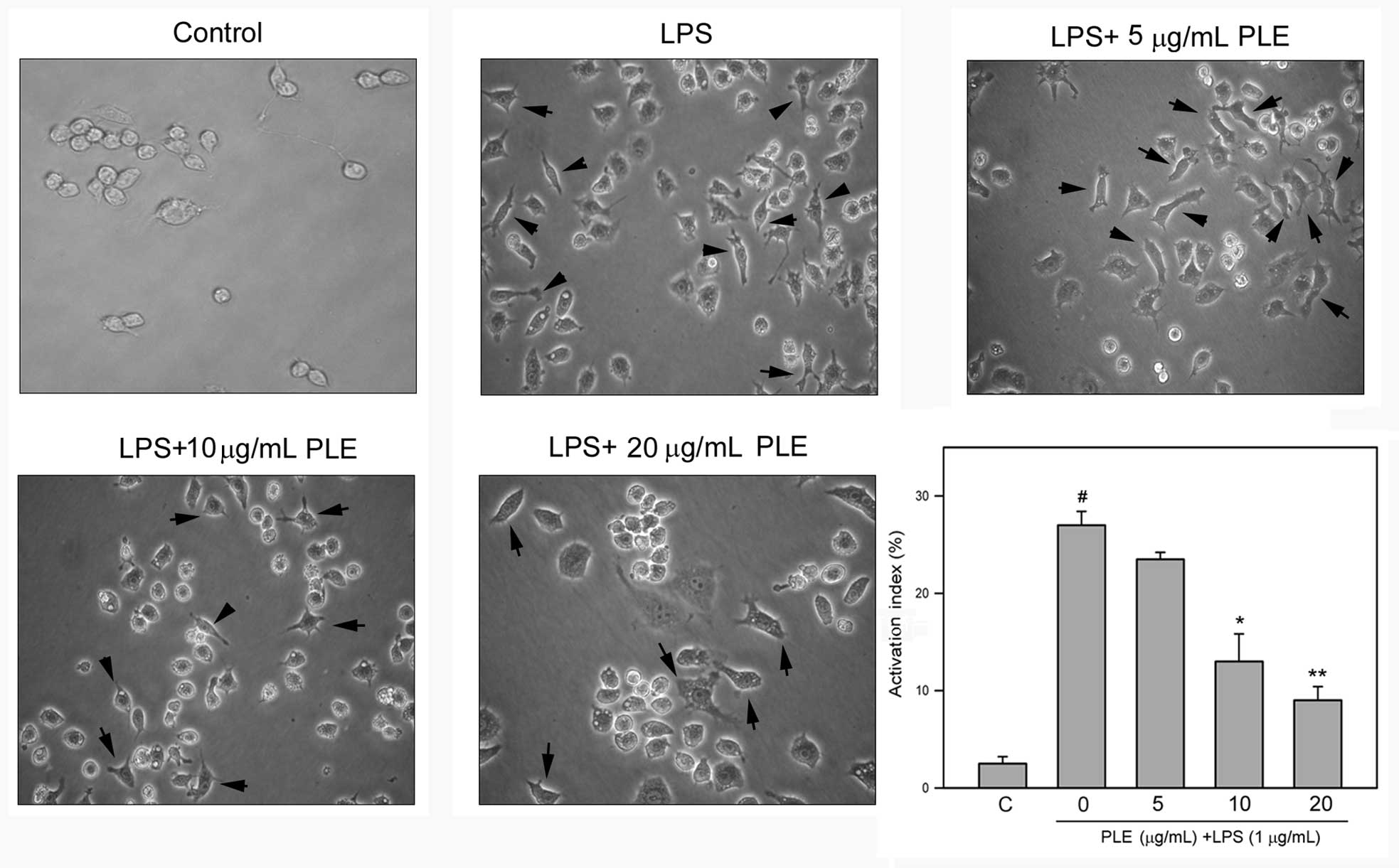

PLE inhibits LPS-induced dendritic

transformation of RAW264.7 cells

LPS is known to induce morphological transformation

of macrophage RAW264.7 cells (18). Therefore, whether PLE affects the

LPS-induced morphological changes of RAW264.7 cells was

investigated. As shown in Fig. 2,

LPS alone significantly induced the morphological transformation of

RAW264.7 cells to dendritic cells, and this transformation was

attenuated by PLE pretreatment in a dose-dependent manner. Further

quantitative analysis revealed that LPS significantly increases the

number of cells having a dendritic morphology to 27.0±0.5%

(P<0.05 as compared to the control). When cells were pretreated

with 10 or 15 μg/ml PLE and then treated with LPS, the number of

cells with dendritic morphology was decreased to 13.6±1.6 and

9.4±0.6%, respectively (P<0.05 as compared to LPS treatment

alone).

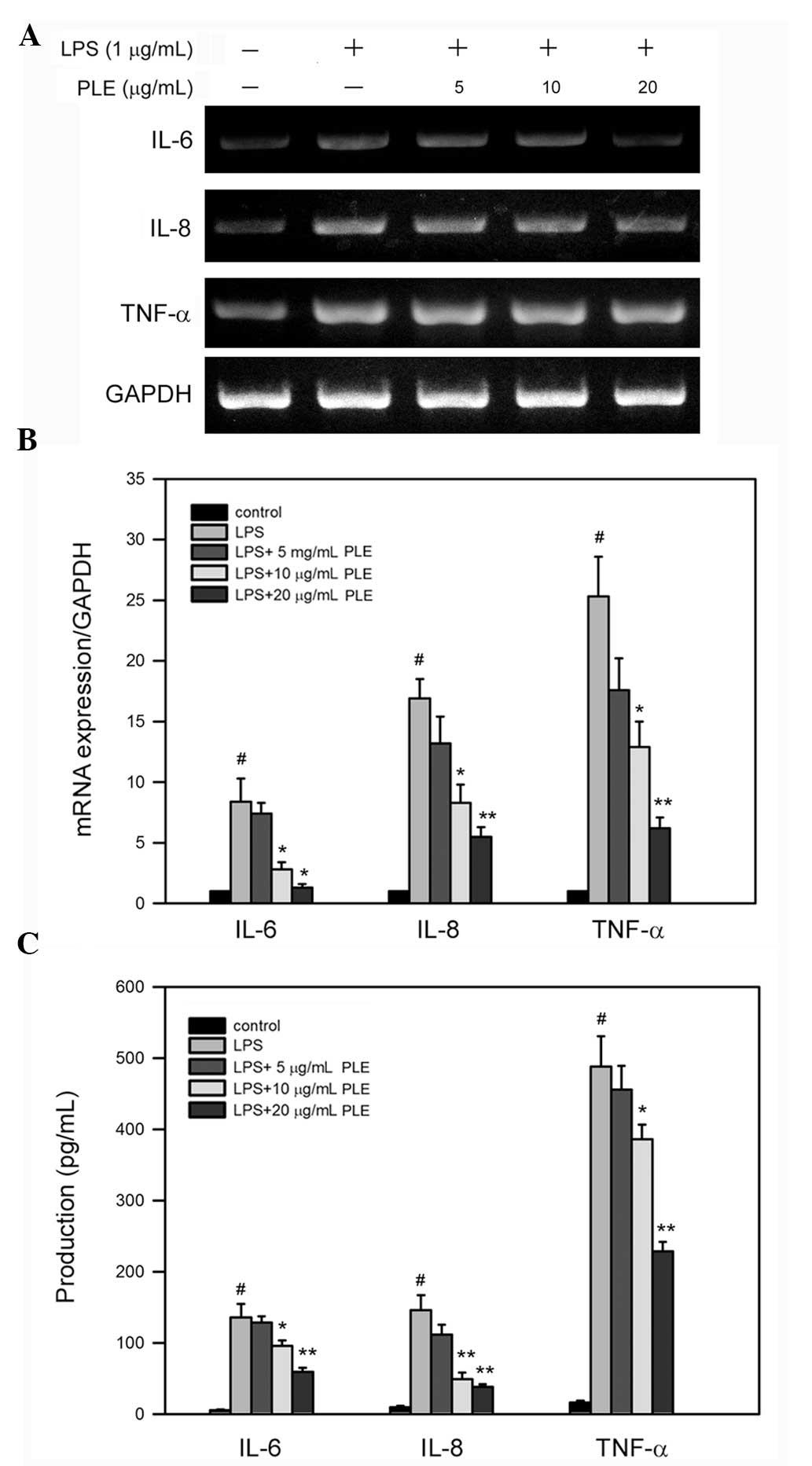

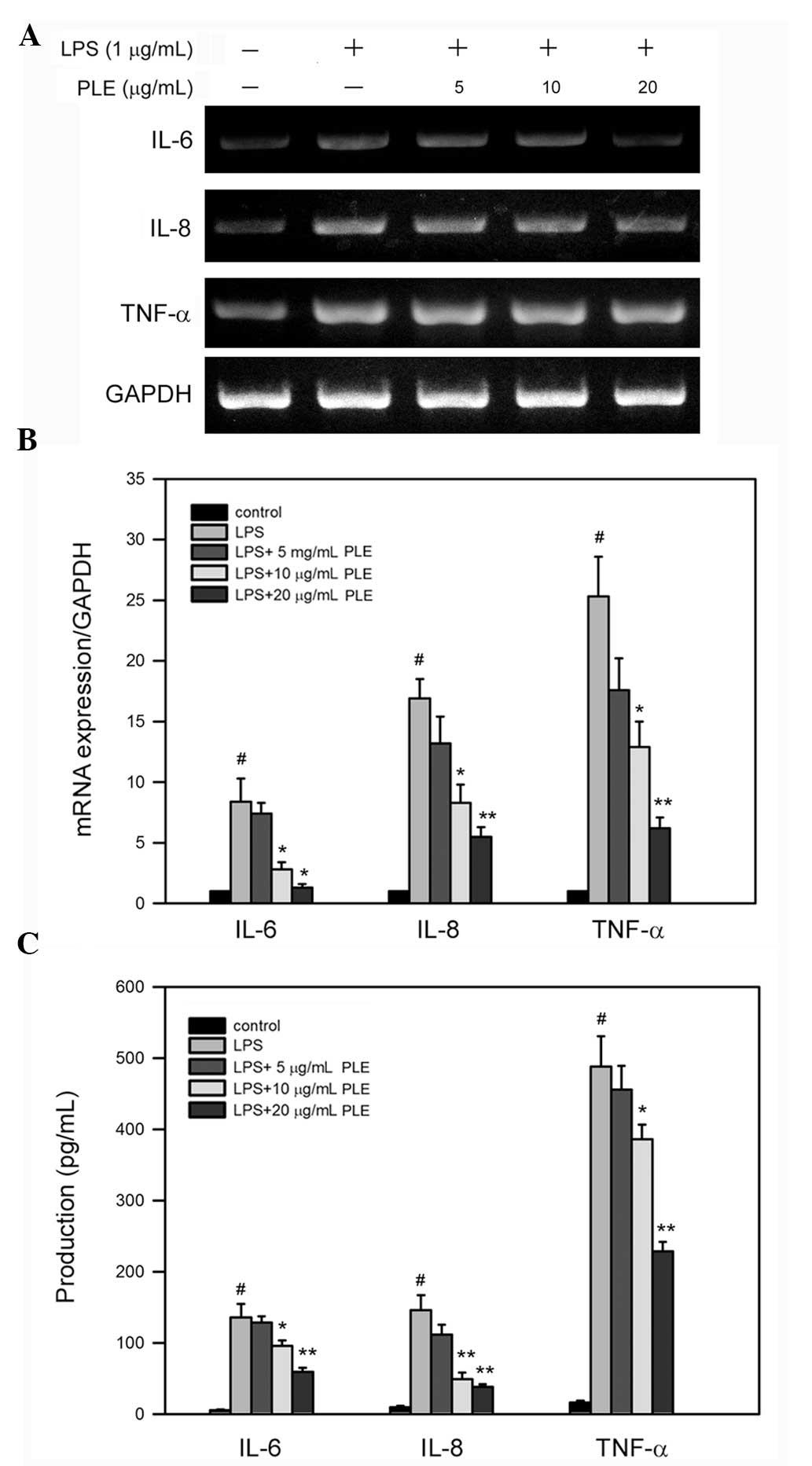

PLE inhibits LPS-induced mRNA expression

and production of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α in RAW264.7 cells

To investigate whether PLE affects the expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated macrophages, the mRNA

levels of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α were determined

in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells. RT-PCR analysis revealed that LPS

alone enhances the expression of IL-6, IL-8 and

TNF-α, and this increase is reverted by pretreatment with

PLE in a dose-dependent manner (Fig.

3A). Further quantitative analysis using qRT-PCR showed that

treatment with LPS alone significantly increases the mRNA levels of

IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, 3.9±0.4-, 13.8±1.5- and

5.4±0.3-fold respectively (Fig.

3B), as compared to the control (untreated cells). In RAW264.7

cells pretreated with 20 μg/ml PLE and then treated with 1 μg/ml

LPS, the mRNA levels of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α

were reduced 1.4±0.2-, 5.1±0.3- and 3.4±0.2-fold as compared to the

control, respectively (P<0.005 as compared to LPS alone).

| Figure 3PLE reduces the mRNA level and the

protein production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8 and

TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Cells were pre-incubated

with the indicated concentrations of PLE in the DMEM culture medium

for 4 h, and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 6 or 24 h.

Following treatment, the cells were lysed for mRNA extraction, and

the gene expression level was analyzed by (A) RT-PCR and quantified

by (B) qRT-PCR, while the culture medium was collected to quantify

the production of corresponding proteins by (C) ELISA. Bars denote

standard deviation (SD) of the mean from three independent

experiments. #P <0.05 as compared to the control

(untreated cells); *P<0.05 as compared to LPS alone.

PLE, Perilla frutescens leaf extract; IL, interleukin;

TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; RT-PCR,

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; q,

quantitative. |

In addition to mRNA expression, LPS alone increased

the protein production of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in RAW264.7 cells

(Fig. 3C) up to 135.7±18.9,

145.9±21.3 and 488.2±33.2 pg/ml/104 cells, respectively

(P<0.05 as compared to the control). PLE pretreatment

dose-dependently reduced the protein production of the tested

cytokines (Fig. 3C) up to 59.3±5.6

(IL-6), 38.2±3.9 (IL-8) and 228.7±13.3 pg/ml/104 cells

(TNF-α), respectively (P<0.05 as compared to LPS alone).

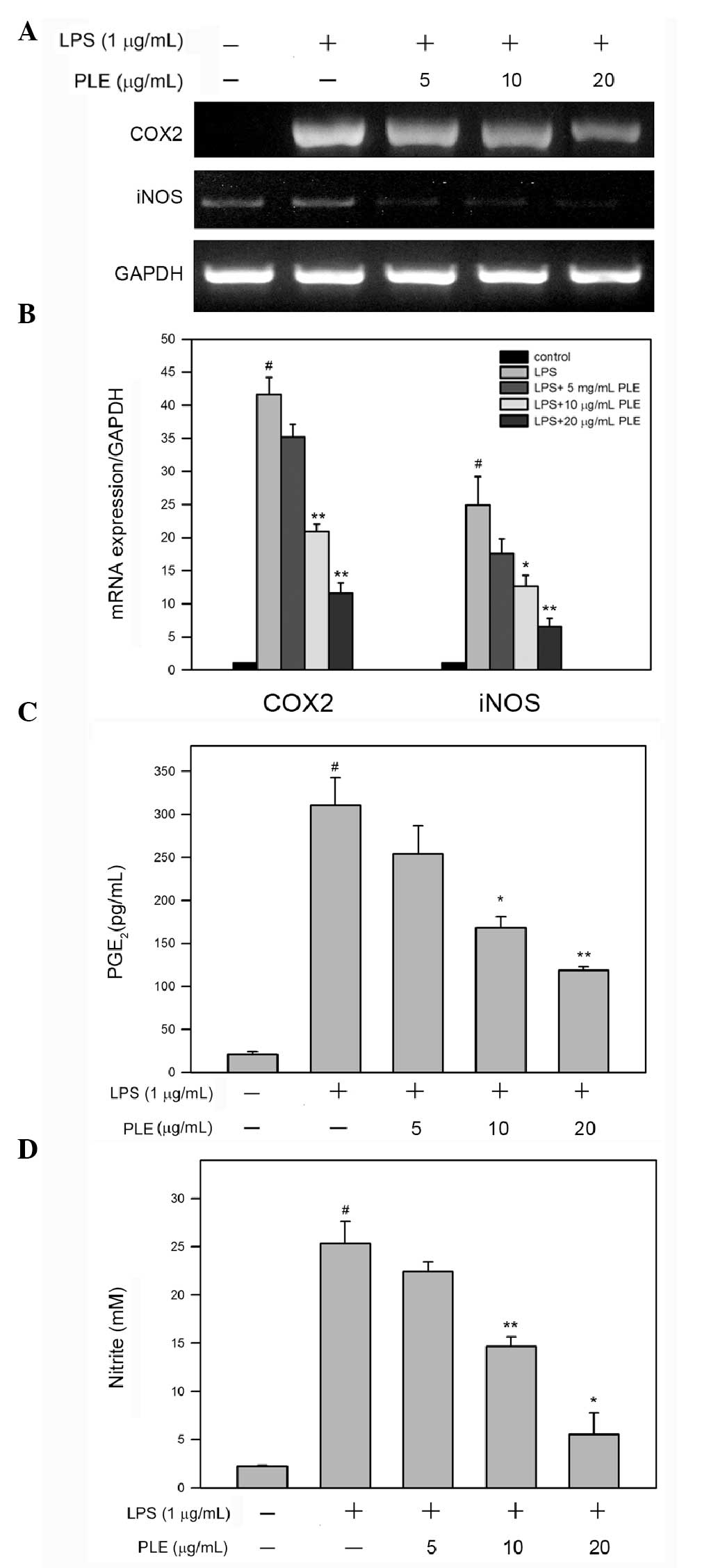

PLE inhibits LPS-induced mRNA expression

of COX-2 and iNOS and the production of PGE2 and NO in

RAW264.7 cells

COX-2 and iNOS are both critical enzymes associated

with macrophage-mediated development and progression of

inflammation (19–21); therefore, effects of PLE on the

mRNA level of COX-2 and iNOS were analyzed and

quantified in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. RT-PCR analysis showed

that LPS treatment alone enhances the expression of COX-2

and iNOS, and this increase was reverted by pretreatment

with PLE in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Further quantitative analysis

using qRT-PCR revealed that LPS alone significantly increases the

mRNA levels of COX-2 and iNOS, 41.6±2.6- and

24.9±4.3-fold, respectively, as compared to the control

(P<0.05). In RAW264.7 cells pretreated with 20 μg/ml PLE and

then treated with 1 μg/ml LPS, the mRNA levels of COX-2 and

iNOS were dose-dependently reduced (Fig. 4B) 11.6±1.5- and 6.6±1.2-fold as

compared to the control, respectively (P<0.05 as compared to LPS

alone).

Since mRNA expression of COX-2 and

iNOS in RAW264.7 cells treated with LPS was inhibited by PLE

pretreatment, the production of PGE2 and NO was further

assessed. As shown in Fig. 4C and

D, treatment with LPS alone significantly increased the

concentrations of PGE2 and NO up to 310.9±22.5 pg/ml and

25.3±1.6 μM, respectively. Upon pretreatment with 10 or 20 μg/ml

PLE, the concentration of PGE2 was reduced down to

168.1±9.2 pg/ml and 118.7±3.1 pg/ml, respectively, and the

concentration of NO was decreased to 14.7±0.7 and 5.5±1.3 μM,

respectively (P<0.05 as compared to LPS alone).

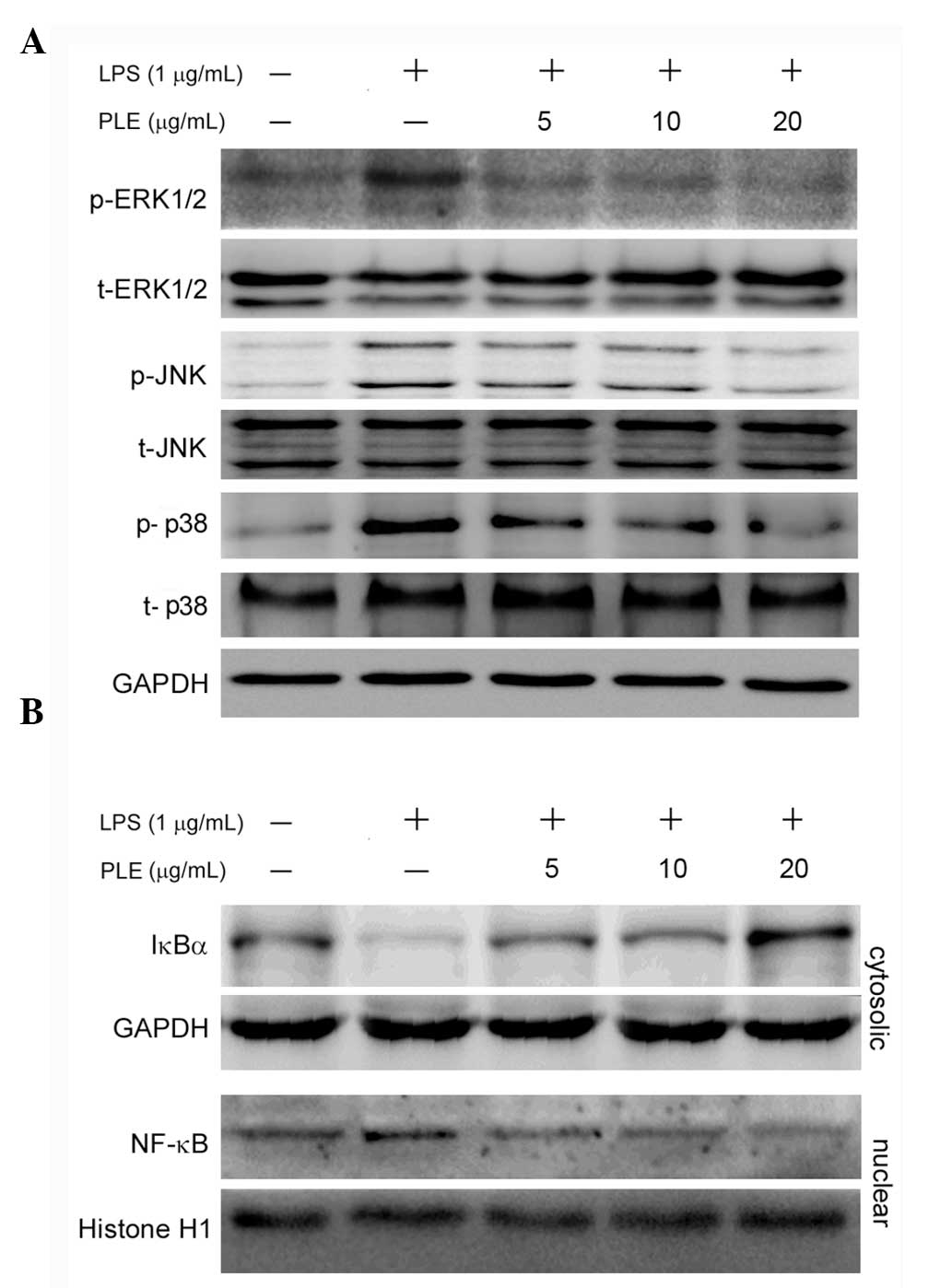

PLE inhibits phosphorylation of MAPKs,

the degradation of IκBα and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB in

LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells

Activation of MAPKs is known to be involved in

LPS-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (22–24).

To investigate whether PLE regulates activation of MAPKs in

response to LPS, the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK and p38

were determined by immunoblotting in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells.

As shown in Fig. 5A, LPS alone

considerably increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK and p38

in RAW264.7 cells, and pretreatment with 5, 10 or 20 μg/ml PLE

inhibited the LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK and p38 in

a dose-dependent manner.

The transcription factor NF-κB plays a pivotal role

in regulation of pro-inflammatory factors, and its nuclear

translocation is associated with the expression of these factors

(25). Thus, the effects of PLE on

the cytosolic level of IκBα (that inhibits the nuclear

translocation of NF-κB) and the nuclear level of NF-κB were

subsequently investigated in RAW264.7 cells exposed to LPS. As

shown in Fig. 5B, exposure of

RAW264.7 cells to LPS led to an important decrease in the cytosolic

IκBα level, accompanied by the expected increase in the nuclear

NF-κB level. However, PLE pretreatment restored the LPS-decreased

cytosolic IκBα level and reduced the nuclear NF-κB level that had

been increased by LPS treatment, in a dose-dependent manner. These

findings revealed that PLE inhibits not only the degradation of

IκBα, but also the nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

Discussion

Macrophages were reported to be directly involved in

the inflammatory response (26).

One of the most important roles of macrophages is the production of

various cytokines, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, growth

factors and chemokines as a response to signals such as bacterial

LPS (27). Although the bioactive

molecules produced by macrophages play important roles in

inflammation, these molecules were also shown to exert undesirable

effects to the cells (28).

Therefore, modulation of these products may provide potential

targets for the control of inflammatory diseases. IL-6 has various

biological effects in a number of chronic endothelial dysfunctions

such as modulation of hematopoiesis, proliferation and

differentiation of lymphocytes, and induction of acute-phase

reactions (29). IL-8 is generally

recognized as a key intermediate regulator in acute inflammatory

responses (30). TNF-α is an

important mediator produced by activated macrophages and was shown

to affect various biological processes, including the regulation

and the production of other cytokines (31,32).

Our findings revealed that PLE inhibits the dendritic

transformation of RAW264.7 cells and the expression of IL-6, IL-8

and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, suggesting that PLE may

attenuate the LPS-induced activation of macrophages and the

consequent production of inflammatory cytokines.

NO is an important mediator and regulator involved

in inflammatory responses. In activated inflammatory cells, NO is

produced at high levels by iNOS. COX-2 is regarded as a central

mediator of inflammation, and regulation of COX-2 was suggested to

be useful in the development of a therapeutic target (33). Moreover, the enzymatic activity of

COX-2 is directly affected by NO and iNOS (34,35).

Our results showed that PLE inhibits both COX-2 and

iNOS expression, as well as NO production, which further

supports that PLE can attenuate the inflammatory response.

LPS is known to activate several signaling kinases,

including ERK1/2, MEK (36), JNK,

AP-1 (22), p38 and other MAP

kinase family members (37). Our

findings show that PLE inhibits iNOS expression and NO

production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, which may relate to

the downregulation of NF-κB signaling components, including ERK1/2,

JNK and p38. The inhibitory effect of PLE on NF-κB, ERK1/2 and JNK

expression is crucial for the expression of iNOS.

In conclusion, the results from the present study

indicate that PLE displays important anti-inflammatory activity in

LPS-stimulated macrophage RAW264.7 cells, through inhibition of the

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of MAPK

activation, and of NF-κB nuclear translocation in response to

LPS.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by grants from the

National Science Council, Taiwan (nos. NSC99-2320-B-040-003-MY3 and

NSC99-2632-B-040-001-MY3).

References

|

1

|

Ueda H and Yamazaki M: Inhibition of tumor

necrosis factor-alpha production by orally administering a

Perilla leaf extract. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem.

61:1292–1295. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Makino T, Ono T, Muso E, Honda G and

Sasayama S: Suppressive effects of Perilla frutescens on

spontaneous IgA nephropathy in ddY mice. Nephron. 83:40–46.

1999.

|

|

3

|

Ueda H and Yamazaki M: Anti-inflammatory

and anti-allergic actions by oral administration of a

Perilla leaf extract in mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem.

65:1673–1675. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shin TY, Kim SH, Kim SH, et al: Inhibitory

effect of mast cell-mediated immediate-type allergic reactions in

rats by Perilla frutescens. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol.

22:489–500. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hortelano S, Zeini M and Bosca L: Nitric

oxide and resolution of inflammation. Methods Enzymol. 359:459–465.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Paige JS and Jaffrey SR: Pharmacologic

manipulation of nitric oxide signaling: targeting NOS dimerization

and protein-protein interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 7:97–114.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gao YT, Panda SP, Roman LJ, Martasek P,

Ishimura Y and Masters BS: Oxygen metabolism by neuronal

nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 282:7921–7929. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Breitbach K, Klocke S, Tschernig T, van

Rooijen N, Baumann U and Steinmetz I: Role of inducible nitric

oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase in early control of

Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in mice. Infect Immun.

74:6300–6309. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cunha IW, Lopes A, Falzoni R and Soares

FA: Sarcomas often express constitutive nitric oxide synthases

(NOS) but infrequently inducible NOS. Appl Immunohistochem Mol

Morphol. 14:404–410. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Farley KS, Wang LF, Razavi HM, et al:

Effects of macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase in murine

septic lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

290:L1164–L1172. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sacco RE, Waters WR, Rudolph KM and Drew

ML: Comparative nitric oxide production by LPS-stimulated

monocyte-derived macrophages from Ovis canadensis and Ovis aries.

Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 29:1–11. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rahman A, Yatsuzuka R, Jiang S, Ueda Y and

Kamei C: Involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 in allergic nasal

inflammation in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 6:1736–1742. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Geng Y, Zhang B and Lotz M: Protein

tyrosine kinase activation is required for lipopolysaccharide

induction of cytokines in human blood monocytes. J Immunol.

151:6692–6700. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim HS, Ye SK, Cho IH, et al:

8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine suppresses NO production and COX-2 activity

via Rac1/STATs signaling in LPS-induced brain microglia. Free Radic

Biol Med. 41:1392–1403. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Park HJ, Kim IT, Won JH, et al:

Anti-inflammatory activities of

ent-16alphaH,17-hydroxy-kauran-19-oic acid isolated from the roots

of Siegesbeckia pubescens are due to the inhibition of iNOS

and COX-2 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages via NF-kappaB

inactivation. Eur J Pharmacol. 558:185–193. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Nakano H, Shindo M, Sakon S, et al:

Differential regulation of IkappaB kinase alpha and beta by two

upstream kinases, NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and mitogen-activated

protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

95:3537–3542. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper

PL, Wishnok JS and Tannenbaum SR: Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and

[15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 126:131–138.

1982.

|

|

18

|

Saxena RK, Vallyathan V and Lewis DM:

Evidence for lipopolysaccharide-induced differentiation of RAW264.7

murine macrophage cell line into dendritic like cells. J Biosci.

28:129–134. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Onuchic AC, Machado CM, Saito RF, Rios FJ,

Jancar S and Chammas R: Expression of PAFR as part of a prosurvival

response to chemotherapy: a novel target for combination therapy in

melanoma. Mediators Inflamm. 2012:1754082012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen H, Ma F, Hu X, Jin T, Xiong C and

Teng X: Elevated COX2 expression and PGE2 production by

downregulation of RXRα in senescent macrophages. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 440:157–162. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Adesso S, Popolo A, Bianco G, et al: The

uremic toxin indoxyl sulphate enhances macrophage response to LPS.

PloS One. 8:e767782013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hambleton J, Weinstein SL, Lem L and

DeFranco AL: Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in bacterial

lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

93:2774–2778. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

An H, Yu Y, Zhang M, et al: Involvement of

ERK, p38 and NF-kappaB signal transduction in regulation of TLR2,

TLR4 and TLR9 gene expression induced by lipopolysaccharide in

mouse dendritic cells. Immunology. 106:38–45. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang W, Deng M, Liu X, Ai W, Tang Q and Hu

J: TLR4 activation induces nontolerant inflammatory response in

endothelial cells. Inflammation. 34:509–518. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tak PP and Firestein GS: NF-kappaB: a key

role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 107:7–11. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Murakami A, Nishizawa T, Egawa K, et al:

New class of linoleic acid metabolites biosynthesized by corn and

rice lipoxygenases: suppression of proinflammatory mediator

expression via attenuation of MAPK- and Akt-, but not PPARgamma-,

dependent pathways in stimulated macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol.

70:1330–1342. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Fujiwara N and Kobayashi K: Macrophages in

inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 4:281–286. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Heumann D and Roger T: Initial responses

to endotoxins and Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Chim Acta.

323:59–72. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Desai TR, Leeper NJ, Hynes KL and Gewertz

BL: Interleukin-6 causes endothelial barrier dysfunction via the

protein kinase C pathway. J Surg Res. 104:118–123. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Noda A, Kinoshita K, Sakurai A, Matsumoto

T, Mugishima H and Tanjoh K: Hyperglycemia and lipopolysaccharide

decrease depression effect of interleukin 8 production by

hypothermia: an experimental study with endothelial cells.

Intensive Care Med. 34:109–115. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hume DA, Underhill DM, Sweet MJ, Ozinsky

AO, Liew FY and Aderem A: Macrophages exposed continuously to

lipopolysaccharide and other agonists that act via toll-like

receptors exhibit a sustained and additive activation state. BMC

Immunol. 2:112001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Ashikawa K and

Bharti AC: The role of TNF and its family members in inflammation

and cancer: lessons from gene deletion. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm

Allergy. 1:327–341. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tsatsanis C, Androulidaki A, Venihaki M

and Margioris AN: Signalling networks regulating cyclooxygenase-2.

Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 38:1654–1661. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK,

Pandey MK and Sethi G: Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the

link? Biochem Pharmacol. 72:1605–1621. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Korhonen R, Lahti A, Kankaanranta H and

Moilanen E: Nitric oxide production and signaling in inflammation.

Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 4:471–479. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Geppert TD, Whitehurst CE, Thompson P and

Beutler B: Lipopolysaccharide signals activation of tumor necrosis

factor biosynthesis through the ras/raf-1/MEK/MAPK pathway. Mol

Med. 1:93–103. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Han J, Lee JD, Bibbs L and Ulevitch RJ: A

MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian

cells. Science. 265:808–811. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|