Introduction

Conventional use of cyclosporine A (CsA) following

kidney transplantation is considered to be associated with the

development of chronic allograft nephropathy, which leads to a

gradual and irreversible loss of graft function and is a major

cause of redialysis following renal transplantation (1). At present, the mechanism of

CsA-induced nephrotoxicity (CAN) is not fully understood, however,

results indicate that CsA may lead to an increase in reactive

oxidative metabolites and reduced renal antioxidant capacity

(2). Oxidative stress is a major

trigger of CAN. CsA directly induces endothelial cell membrane

lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress in cells, which enhances

the production of oxygen free radicals (3,4). In

addition, CsA also blocks the formation of nitric oxide, thereby

increasing the damage caused by oxidative stress. Blocking the

expression of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) reduces the production of

reactive oxidative metabolites and improves kidney antioxidant

capacity (5,6). Curcumin (Cur) has been reported to

increase the proliferation, reduce the rate of apoptosis and reduce

the Bcl-2-associated X (Bax)/Bcl-2 ratio in human umbilical vein

endothelial cells (7).

Oxidative stress is also associated with the

occurrence of CAN (8).

Histological manifestations of CAN include progressive

glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis associated with

mononuclear cell infiltration and renal tubular atrophy, while the

primary clinical manifestations are progressive deterioration of

renal function, hypertension and proteinuria (9,10).

These manifestations are consistent with renal injury in which

oxidative stress is the major cause. There is also evidence that

oxidative stress is involved in the glomerular atrophy observed in

interstitial fibrosis of epithelial cells to fibroblasts during the

process of metaplasia (11).

Oxidative stress in chronic graft kidney glomerular atrophy

interstitial degeneration in an animal experimental model has also

been confirmed (12), increased

cell membrane unsaturated fatty acids and cholesterol lipid

peroxidation was observed, while the cell membrane fluidity was

decreased and permeability was increased, affecting the

membrane-associated enzyme involved in the biochemical process and

ion pump function. In addition, oxidative stress may also induce

the oxidation of biological macromolecules, and protein structure

and conformational were altered through the direct effect on the

sensitive amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine and

cysteine), or through lipid peroxidation products causing oxidative

damage, leading to cell death or apoptosis, tissue and organ damage

(13). Oxidative stress also leads

to the dysfunction of important intracellular organelles, such as

the mitochondrial inner membrane that functions in the oxidative

phosphorylation process, which leads to mitochondrial dysfunction

(14,15). Studies have demonstrated that

oxidative stress is also an important intracellular messenger,

activating various intracellular signaling pathways (16,17)

and mediating cell stress responses and injury responses. Oxidative

stress is an important pathogenic factor influencing the recovery

of short- and long-term function following renal transplantation

(18–20). The progression of CAN may be

alleviated according to the characteristics of its different stages

and the application of suitable antioxidants.

Cur is a yellow, acidic phenol that is extracted

from Curcuma longa L., also termed Turmeric, is one member

of ginger family (21). Cur is the

major active ingredient that has a pharmacological role. Cur is a

type of plant polyphenol that exhibits a wide range of biological

activities, including antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anticancer,

anti-atherosclerotic, antimutagenic and immunoregulatory effects

(22). Cur has antioxidant

capacity in neutral and acidic environments, and interferes with

cell signaling at various levels and affects biological enzyme

activity, angiogenesis and cell adhesion (23,24).

It was also reported in a preclinical study that Cur influences

gene transcription and induces apoptosis (25). In rat kidneys, Cur alleviates

damage caused by nephrotoxic substances, including doxorubicin,

cyclosporine, gentamicin, chloroquine and ischemia-reperfusion

injury due to its antioxidant properties (26–28).

The potential of Cur in the prevention and treatment of diabetic

nephropathy is primarily based on its antioxidative (29,30)

and antifibrotic (31) properties;

to the best of our knowledge, its role in inflammatory lesions has

not previously been reported. Cur is reported to inhibit the

activity of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase (32), reduce free radicals generated from

the arachidonic acid pathway, suppress xanthine oxidase activity

(33), decrease adenosine

metabolism of free radicals and interfere with nitric oxide

synthase activity (34) to reduce

the arginine metabolism of nitric oxide caused by the generation of

free radicals, thereby limiting oxygen free radical damage and

exhibiting a protective role. Cur may function in the antioxidant

process through various mechanisms (35,36):

Cur and its derivatives inhibit metal ion (Fe2+ and

Cu2+)-induced lipid peroxidation, inhibits oxidative

modification of low density lipoprotein and protects DNA from

oxidative lipid damage; Cur inhibits the production of reactive

oxygen species and scavenging free radicals (including ·OH, DPPH·

and O2−) and peroxide. Cur reduces serum and tissue

lipid peroxide levels and enhances superoxide dismutase (SOD) and

glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity; Cur inhibits NADPH

oxidase expression and the activation of xanthine oxidase 8; and

Cur inhibits the synthesis of nitric oxide or accelerates its

clearance so that levels in the kidney are low to prevent nitric

oxide toxicity. The effect of oxidative stress on chronic CsA renal

injury in rats and the effect of Cur on renal injury have not been

widely reported. Therefore, the present study aimed to provide an

experimental basis for the further development and application of

the natural active substance, Cur.

Materials and methods

Drugs

Cur, with a purity of 99.8%, was purchased from

Shijiazhuang spring letter Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shijiazhuang,

China; http://www.sjzcxswkj.com) and CsA was

obtained from Zhejiang Ruibang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Wenzhou,

China).

Primary reagents

Rabbit anti-human Bax primary antibody and

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary

antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

(Danvers, MA, USA). Rabbit anti-human Bcl-2 primary antibody and

β-actin primary antibody were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

SOD (cat no. A001-3), malondialdehyde (MDA; cat no. A003-1), GSH-Px

(cat no. A005), reactive oxygen species (ROS; cat no. E004) and

catalase (CAT; cat no. A007-1-1) detection kits were all purchased

from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China).

Other reagents were of domestic and analytical grade.

HK-2 human renal cells culture

HK-2 cells were purchased from Beijing Zhongyuan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The base medium

for this cell line was provided by Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA) as part of a kit: Keratinocyte

serum free medium (K-SFM; kit cat no. 17005-042). This kit was

supplied with each of the two additives required to grow this cell

line (bovine pituitary extract (BPE) and human recombinant

epidermal growth factor (EGF). The following components were added

the base medium: 0.05 mg/ml BPE-provided with the K-SFM kit; 5

ng/ml EGF-provided with the K-SFM kit. Atmosphere: air, 95%; carbon

dioxide (CO2), 5%, 37.0°C and humidity 70–80%.

Detection of oxidative stress in HK-2

human renal cells

HK-2 cells (2×104 cells/well) were

assigned to the following groups for 48 h at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 incubator: Control (equivalent volume of saline), 50

µM Cur, 2 µM CsA, 10 µM Cur + 2 µM CsA, 50 µM Cur + 2 µM CsA, 100

µM Cur + 2 µM CsA and 5 µM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Cells were washed with PBS,

collected in a test tube with 1 ml normal saline and lysed with an

ultrasonic crusher. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min

at 4°C, SOD activity and MDA levels in the supernatant were

measured by SOD and MDA kits, a GSH-Px detection kit was used to

measure GSH-Px activity, an ROS detection kit was used to measure

ROS levels and a CAT detection kit was used to determine CAT

activity.

MTT assay

HK-2 cells in logarithmic growth phase were

inoculated in 96-well plates (5×103 cells per well),

added with different concentrations of Cur (0.1, 1, 10, 100 and

1,000 µM) and then co-incubated with or without (2 µM) for 24 h at

37°C. After incubating at 37°C for 4 h with 20 µl MTT (5 mg/ml),

200 µl DMSO was added. After 10 min vibration, the absorbance value

of the mixture was measured at 560 nm using a microplate

reader.

Western blot analysis

HK-2 cells in the control and different treatment

groups were washed three times with cold PBS and lysed with RIPA

lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China;

cat. no. P0013B) on ice. Lysates were collected and centrifuged at

12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected and

protein concentration was determined by a BCA assay. A 10% SDS-PAGE

gel was prepared and samples were loaded (80 µg protein per lane),

and run on the gel. After 2 h of SDS-PAGE, proteins were

transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Subsequently,

blocking with 5% non-fat milk was performed for 1 h at room

temperature and the membranes were incubated with diluted primary

antibodies, including rabbit anti-human Bax (cat. no. 5023; 1:1,500

dilution), anti-β actin antibody (cat no. ab227387; 1:2,000

dilution) and Bcl-2 (cat. no. ab194583; 1:2,000 dilution)

antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed three times

with 1X TBS 0.1% Tween-20 and then the horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. no.

7074; 1:4,000) was added and incubated with the membrane at room

temperature for 2 h. Grey scale and area of the protein band were

analyzed by gel imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA) with enhanced chemiluminescent kit (SuperSignal;

Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat no. 34094). The protein

expression level was indicated by the integral grey value (D,

density) using Image J software (National Institutes of Health,

USA).

Apoptosis assay

HK-2 cells treated with medium or different drugs

for 48 h were collected and treated according to the Annexin V-FITC

Apoptosis Detection kit (Vazyme Biotech; cat no. a211-01). After

washing twice with PBS, cells were suspended with 1X binding

buffer, added with 5 µl of fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled

Annexin V and 5 µl of PI, and then mixed gently. After incubation

at room temperature for 15 min, the cells were analyzed by flow

cytometry. A total of 20,000 cells were analyzed each time.

CAN rats model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=60; 7 weeks of age),

clean grade and weighing 200–250 g, were purchased from the

Experimental Animal Center of Changzhou Cavens Laboratory Animal

Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China) and kept under controlled conditions

(temperature 23±1.5°C, relative humidity 40–60%, 0.03–0.04%

CO2, 12/12 light/dark cycle)- at the Animal Center of

Ningbo University (Ningbo, China). Rats were allowed free access to

drinking water and food. The present study was approved by the

animal ethical committee of the Medical School of Ningbo

university. The rats were randomly divided into four groups

according to their body weight, with n=6 per group: Control group,

Cur group (30 mg/kg/day) (37)-,

CsA group (20 mg/kg/day) and Cur (30 mg/kg/day) + CsA (20

mg/kg/day) group, all of which were administered for 21 days. The

control group received 0.9% sodium chloride injection (4 ml/kg/day,

intragastric) + vegetable oil (2 ml/kg/day, subcutaneous), the Cur

group received Cur (30 mg/kg/day, intragastric) + vegetable oil (2

ml/kg/day, subcutaneous), the CsA group received 0.9% sodium

chloride injection (4 ml/kg/day, intragastric) + CsA (20 mg/kg/day

dissolved in vegetable oil, subcutaneous) and the CsA + Cur group

received Cur (30 mg/kg/day, intragastric) + CsA (20 mg/kg/day

dissolved in vegetable oil, subcutaneous).

Renal function test

On the 22nd day, 24 h urine of rats was collected by

a metabolic cage. The rats were anesthetized with ether and 3.0–4.0

ml blood was collected to obtain serum by centrifugation at 1,400 ×

g for 30 min at 4°C. Serum/urine creatinine (Crea) and blood urea

nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured with a Hitachi Model 7060

automatic biochemical analyzer, and creatinine clearance (Ccr) was

calculated as follows: Ccr=[urine Crea concentration ×1 h urine

volume (ml)]/serum Crea concentration.

Histopathological examination

On the 22nd day, rat kidneys were fixed with 5%

formaldehyde at 4°C for 48 h to prepare paraffin blocks and tissue

sections (5 µm) following dehydration. For histological

investigation, the deparaffinized and rehydrated rat kidney tissue

sections were stained with hematoxylin for 15 min and 1% eosin for

3 min at room temperature by the Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat no. C0105). For periodic

acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, the slides were immersed in periodic

acid solution for 10 min, and then immersed in Schiff's solution

for 30 min at 20°C after being rinsed with distilled water 4 times

using a Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) Staining kit (cat no. ab150680).

After rinsing slides under hot running tap water, the slides were

stained with hematoxylin for 3 min, rinsed in running tap water for

3 min and applied the bluing reagent for 30 sec. Finally, the

distilled water rinsed slides were dehydrated through graded

alcohols. Expression of NF-κB in kidney tissue was detected by

immunohistochemistry. In brief, tissues in paraffin sections were

treated with the following procedures, including dewaxing,

incubation with anti-NF-kB p65 antibody (cat no. ab16502; 1:1,000

dilution) for overnight at 4°C and horse radish

peroxidse-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (CST; cat

no. 7074) for 2 h at room temperature, stained with DAB and mounted

with anti-fade oil. All sections were observed at ×200

magnification on a light microscope (37).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with PASW

Statistics 18.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Somers, USA). Data are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of

variance and the Tukey post-hoc test were used to analyze the

significance between the groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

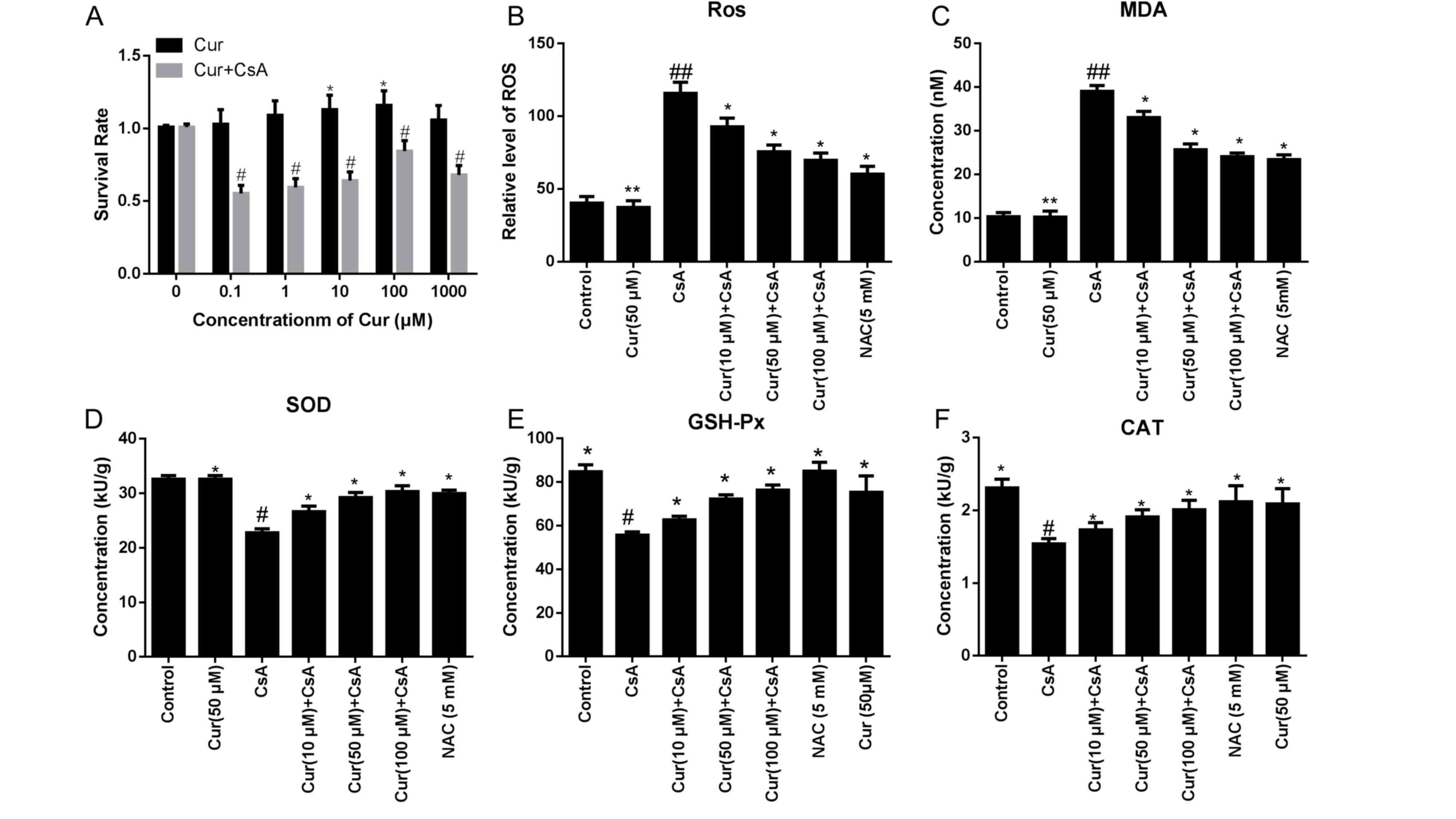

Cur alleviates oxidative stress in

CsA-treated HK-2 cells

In vitro, a concentration of 100 µM Cur improved

cell viability when treated with CsA, compared with lower

concentrations of Cur (Fig. 1A).

The levels of ROS and MDA were significantly downregulated in a

dose-dependent manner following treatment with Cur, compared with

the CsA alone group, as demonstrated in Fig. 1B and C. The ROS level in the CsA

alone group was 115.67±7.66 KU/g, while levels in the 100 µM Cur +

CsA group were 71.67±5.35 KU/g (P<0.01; Fig. 1B). MDA levels in the CsA alone

group were 39.01±1.36, while levels in the 100 µM Cur + CsA group

were 23.85±1.22 nM (P<0.01; Fig.

1C). In addition, the activity of SOD was increased in the 100

µM Cur + CsA group (22.76±0.73 KU/g in the CsA alone group vs.

32.6±0.66 KU/g in the 100 µM Cur + CsA group; P<0.05; Fig. 1D) and the GSH-Px activity was also

increased following treatment with 100 µM Cur (55.65±1.45 in the

CsA alone group vs. 76.04±2.07 KU/g in the 100 µM Cur + CsA group;

P<0.05; Fig. 1E). Furthermore,

CAT activity was increased in the 100 µM Cur-treated group compared

with the CsA alone group (1.54±0.07 in the CsA alone group vs.

2.31±0.12 KU/g in the 100 µM Cur + CsA group; P<0.05; Fig. 1F). CsA-induced increases in ROS and

MDA, and decreases in SOD, GSH-Px and CAT activity, were

dose-dependently reversed by treatment with Cur (Fig. 1B-F).

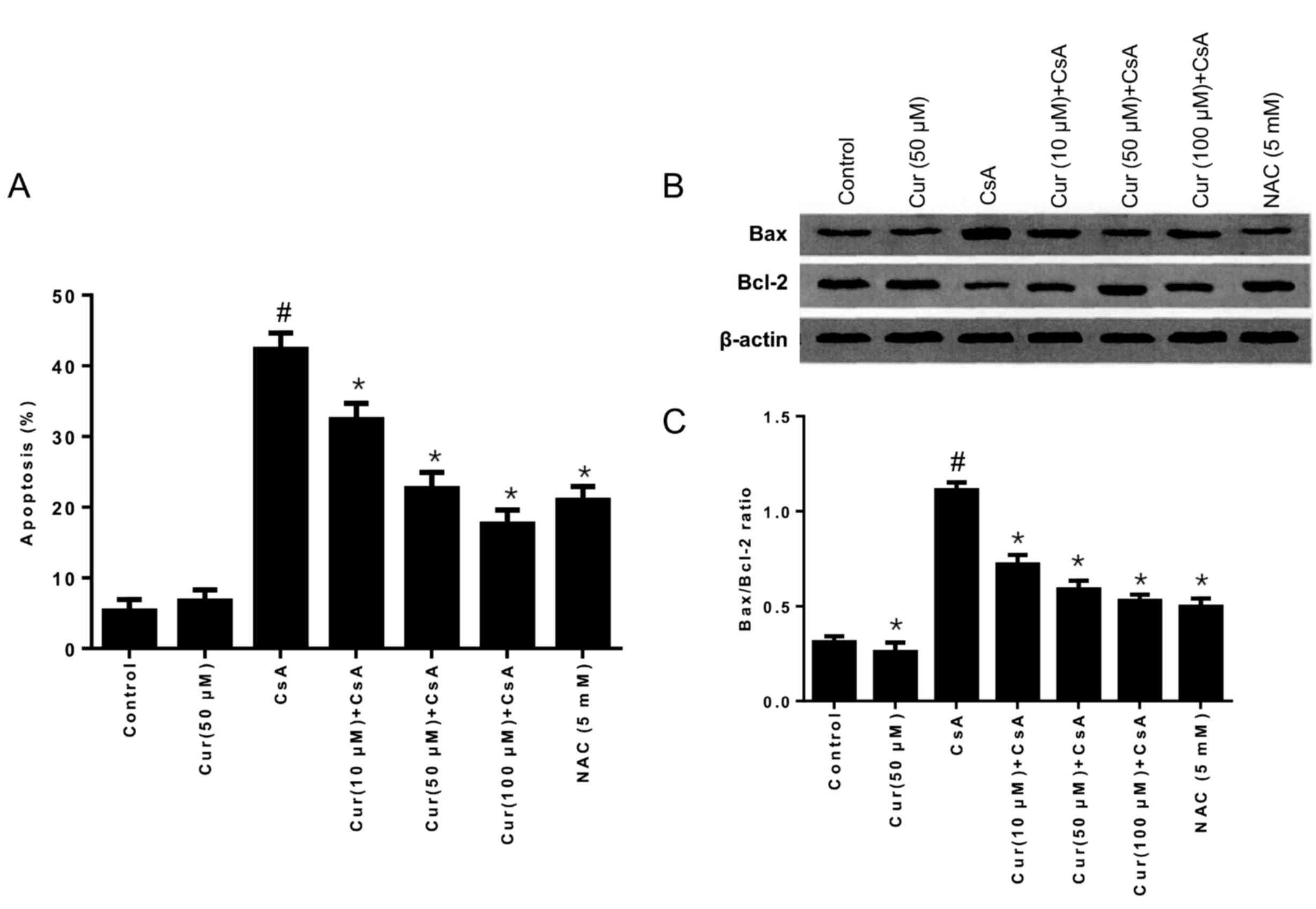

Effects of Cur on Bax and Bcl-2

protein expression

The results in Fig.

2A demonstrate that the rate of apoptosis was gradually

decreased with increasing concentrations of Cur in HK-2 cells,

compared with the CsA alone group, which indicated that Cur may

inhibit CsA-induced cell apoptosis. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 is an

important indicator in the balance between cell apoptosis and

survival. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was decreased when CsA was

combined with Cur treatment, compared with the CsA alone group, as

demonstrated in Fig. 2B and C,

which indicates that levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

were higher compared with the proapoptotic protein Bax, thus

indicating that Cur may improve cell survival in CsA-treated HK-2

cells.

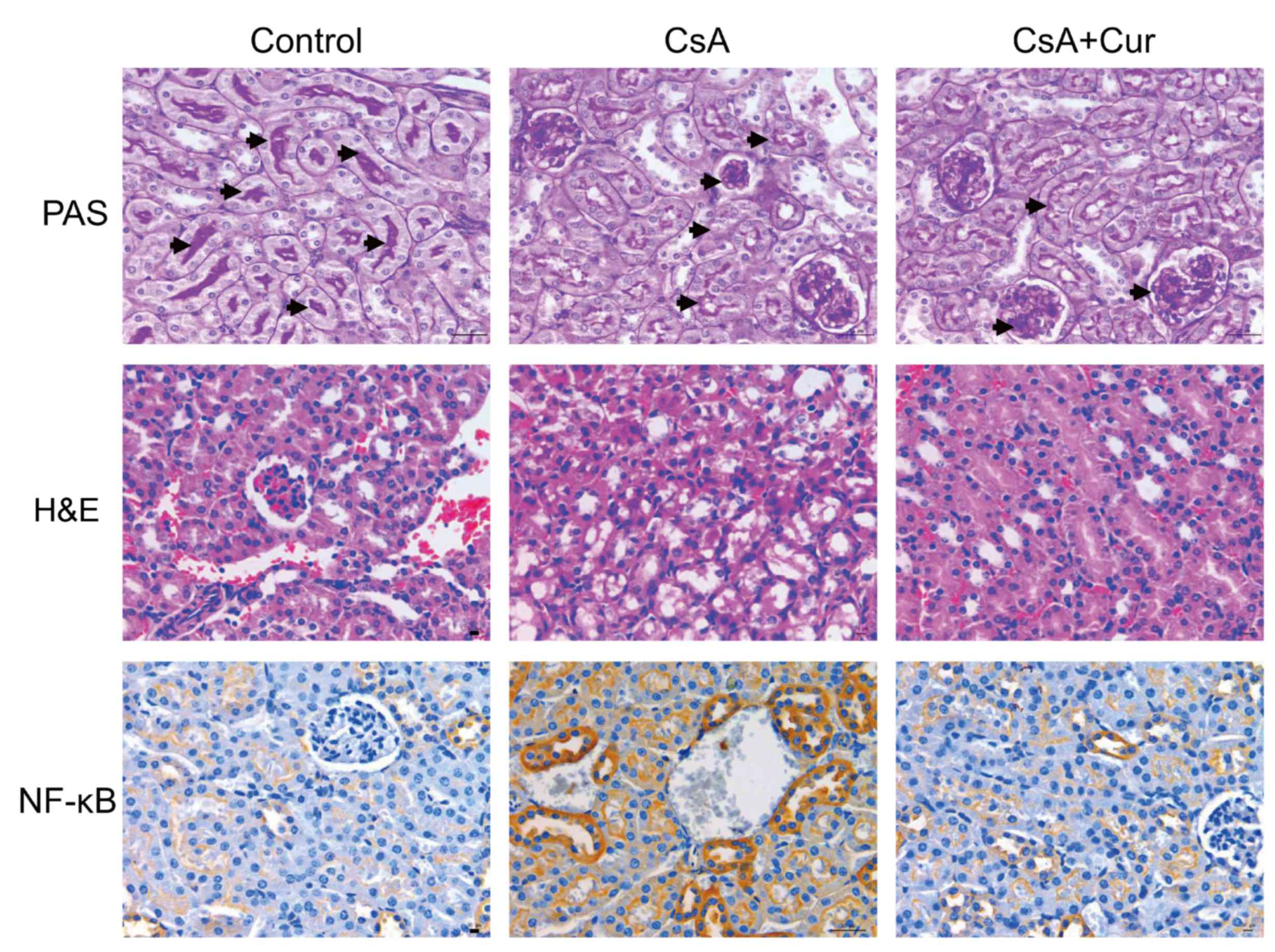

Effect of Cur on CsA-induced CAN model

in rats

To further evaluate the protective effect of Cur in

a CsA-induced rat nephrotoxicity model, renal histopathological

analysis was performed. Histopathological results are presented in

Fig. 3. Hematoxylin and eosin

staining demonstrated that the tissue sections of the control group

exhibited normal structure. By contrast, the kidneys of rats

treated with CsA exhibited marked histological changes, cellular

edema, vacuolar deformation and dissolution. These changes were

reduced when CsA was combined with Cur treatment. The nucleus

presented blue and the glomerular basement membrane was purple. The

glomerular volume was markedly increased in the CsA group, with

mesangial matrix hyperplasia (positive PAS staining), glomerular

swelling, an irregular morphology of certain glomeruli, lobulated

capillary loops and a markedly increased renal capsular space.

NF-κB-positive cell cytoplasm or nuclei were stained brown. The

results demonstrated that NF-κB-positive cells, and therefore

inflammation, were markedly increased in the CsA group compared

with the control group, which was reduced when CsA was combined

with Cur treatment.

Renal function in Cur-treated CAN

rats

As demonstrated in Table I, renal failure was induced by

continuous administration of CsA (20 mg/kg/day) for 21 days. The

serum Crea and BUN were significantly elevated and the Ccr rate was

significantly reduced (P<0.05) in the CsA alone group compared

with the control group. Cur (30 mg/kg/day) alone did not

significantly reduce renal function in rats compared with the

control group, however, Cur significantly improved CsA-induced

renal failure.

| Table I.Effect of Cur on CsA-induced renal

dysfunction in rats. |

Table I.

Effect of Cur on CsA-induced renal

dysfunction in rats.

| Group | BUN, mmol/l | Serum Crea,

µmol/l | Ccr, ml/min |

|---|

| Cur |

4.77±0.52 |

53.12±5.32 |

0.22±0.08 |

| CsA |

10.47±1.45c |

68.33±10.12b |

0.17±0.11a |

| Cur+CsA |

6.68±0.91b,e |

57.98±8.96a,d |

0.18±0.09d |

| Control |

4.88±0.71 |

49.62±6.23 |

0.22±0.06 |

Discussion

CsA is a cyclic polypeptide composed of 11 amino

acids. As a potent immunosuppressive agent, CsA specifically acts

on lymphocytes and inhibits the synthesis and release of

lymphokines, such as interleukin-2 (38). Quiescent lymphocytes are in the G0

phase of the cell cycle and the early G1 phase. Animal experiments

have demonstrated that CsA extended the survival time of allogeneic

organ transplantation and inhibited the cell-mediated immune

response (39). CsA-induced

dose-dependent renal toxicity is the primary reason for its limited

clinical application, which results in renal tubular atrophy,

vacuolar degeneration and renal failure (40). In the present study, rats were

given CsA for 21 consecutive days, and the results demonstrated

marked nephrotoxicity, with increased levels of Crea and BUN,

reduced Ccr and marked vacuolar degeneration and tubular atrophy in

the kidney. A previous study demonstrated that CsA-induced

increases in ROS, leading to cell membrane lipid peroxidation, is

one potential mechanism of CsA-induced nephrotoxicity, while

another study reported that CsA induced in vivo inducible

nitric oxide synthase expression, resulting in high concentrations

of nitric oxide and ROS generation, and increased free radical

activity (2). Peroxynitrite, a

powerful free radical, has been reported to regulate the

tricarboxylic acid cycle, mitochondrial function, electron transfer

and affect DNA synthesis, resulting in increased pathological

damage (34,41). The results of the present study,

from experiments on HK-2 cells, also confirmed that CsA treatment

significantly increased the levels of MDA and Bax protein

expression, and decreased SOD activity and Bcl-2 expression. Cur is

an excellent hydrogen or neutron donor and, during redox reactions

generated as a result of excessive free radicals, the body converts

free radicals into phenolic oxygen free radicals, which protects

the organism against free radical damage. In the body, Cur reacts

with free radicals to generate more stable phenolic oxygen free

radicals, thereby inactivating free radicals (27). In addition, Cur has been reported

to exhibit a protective effect against CsA-induced nephrotoxicity

in rats, as demonstrated by histological alterations and

Glutathione S-transferase immune expression (42). Tirkey et al (42) reported that, through its

antioxidant activity, Cur effectively salvaged CsA-induced

nephrotoxicity. Furthermore, Hu et al (43) demonstrated that the protective

effect of Cur may be mediated by inhibiting the hypermethylation of

the klotho promoter. The present study confirmed that Cur

significantly increased renal antioxidant capacity and decreased

the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in CsA-treated HK-2 cells, which may be

associated with the improvements in CsA-induced renal failure and

renal tubular deformation and cell vacuolization following Cur

treatment in rats. In addition, Tirkey et al (42) demonstrated that Cur markedly

reduced elevated levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances,

significantly attenuated renal dysfunction and increased the levels

of antioxidant enzymes in CsA-treated rats and normalized the

altered renal morphology. The development of renal diseases has

been previously associated with NF-κB activation. NF-κB regulates

the transcription of inflammatory factors in mesangial and tubular

epithelial cells; therefore, it has a central role in the

development and progression of renal disease (44). Wang et al (45) demonstrated that limb ischemic

preconditioning-induced renoprotection in contrast-induced

nephropathy may be dependent on increased renalase expression via

activation of the tumor necrosis factor-α/NF-κB pathway. Renalase

may contribute to the renal protective effect of delayed ischaemic

preconditioning via the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

(45,46). In conclusion, the present study

demonstrated that Cur exhibited a protective effect on CsA-induced

renal dysfunction, and the underlying mechanism may be associated

with the antioxidant capacity of Cur in experimental animals.

However, further investigation is required to determine whether Cur

may be used as a clinical adjuvant to reduce renal toxicity induced

by CsA.

Acknowledgements

This present study was funded by Ningbo Yinzhou

Science and Technology Bureau Project [grant no. 2011 (111)].

References

|

1

|

Jorga A, Holt DW and Johnston A:

Therapeutic drug monitoring of cyclosporine. Transplant Proc. 36 2

Suppl:pp. 396S–403S. 2004; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tedesco D and Haragsim L: Cyclosporine: A

review. J Transplant. 2012:2303862012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhong Z, Arteel GE, Connor HD, Yin M,

Frankenberg MV, Stachlewitz RF, Raleigh JA, Mason RP and Thurman

RG: Cyclosporin A increases hypoxia and free radical production in

rat kidneys: Prevention by dietary glycine. Am J Physiol.

275:F595–F604. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pérez de Lema G, Arribas I, Prieto A,

Parra T, de Arriba G, Rodríguez-Puyol D and Rodríguez-Puyol M:

Cyclosporin A-induced hydrogen peroxide synthesis by cultured human

mesangial cells is blocked by exogenous antioxidants. Life Sci.

62:1745–1753. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mariee AD and Abd-Ellah MF: Protective

effect of docosahexaenoic acid against cyclosporine A-induced

nephrotoxicity in rats: A possible mechanism of action. Ren Fail.

33:66–71. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tavares P, Fontes Ribeiro CA and Teixeira

F: Cyclosporin effect on noradrenaline release from the sympathetic

nervous endings of rat aorta. Pharmacol Res. 47:27–33. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wan Q and Liu ZY: Effect of curcumin on

human umbillcal veln endothellal cell injury induced by lipocalin

2. Chin J Arterioscler. 21:229–233. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

8

|

Djamali A, Reese S, Yracheta J, Oberley T,

Hullett D and Becker B: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and

oxidative stress in chronic allograft nephropathy. Am J Transplant.

5:500–509. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shrestha BM and Haylor J: Biological

pathways and potential targets for prevention and therapy of

chronic allograft nephropathy. Biomed Res Int. 2014:4824382014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Maryniak RK, First MR and Weiss MA:

Transplant glomerulopathy: Evolution of morphologically distinct

changes. Kidney Int. 27:799–806. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH,

Chinga F, Park AS, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J, et al: Defective

fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key

role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 21:37–46. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fonseca I, Reguengo H, Almeida M, Dias L,

Martins LS, Pedroso S, Santos J, Lobato L, Henriques AC and

Mendonça D: Oxidative stress in kidney transplantation:

Malondialdehyde is an early predictive marker of graft dysfunction.

Transplantation. 97:1058–1065. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Andersen JK: Oxidative stress in

neurodegeneration: Cause or consequence? Nat Med. 10 Suppl:S18–S25.

2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Priya DK, Gayathri R, Gunassekaran GR and

Sakthisekaran D: Protective role of sulforaphane against oxidative

stress mediated mitochondrial dysfunction induced by benzo(a)pyrene

in female Swiss albino mice. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 24:110–117. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wei Y, Clark SE, Thyfault JP, Uptergrove

GM, Li W, Whaley-Connell AT, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR and Ibdah JA:

Oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to

angiotensin II-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in

transgenic Ren2 rats. Am J Pathol. 174:1329–1337. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA and

Grodsky GM: Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling

pathways: A unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev.

23:599–622. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yu JH and Kim H: Oxidative stress and

inflammatory signaling in cerulein pancreatitis. World J

Gastroenterol. 20:17324–17329. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Romero F, Herrera J, Nava M and

Rodríguez-Iturbe B: Oxidative stress in renal transplantation with

uneventful postoperative course. Transplant Proc. 31:pp. 2315–2316.

1999; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ruiz MC, Moreno JM, Ruiz N, Vargas F,

Asensio C and Osuna A: Effect of statin treatment on oxidative

stress and renal function in renal transplantation. Transplant

Proc. 38:pp. 2431–2433. 2006; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Vostálová J, Galandáková A, Svobodová AR,

Kajabová M, Schneiderka P, Zapletalová J, Strebl P and Zadražil J:

Stabilization of oxidative stress 1 year after kidney

transplantation: Effect of calcineurin immunosuppressives. Ren

Fail. 34:952–959. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J,

Pauli GF and Walters MA: The essential medicinal chemistry of

curcumin. J Med Chem. 60:1620–1637. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gupta SC, Patchva S, Koh W and Aggarwal

BB: Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its

miraculous biological activities. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol.

39:283–299. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sharma M, Manoharlal R, Puri N and Prasad

R: Antifungal curcumin induces reactive oxygen species and triggers

an early apoptosis but prevents hyphae development by targeting the

global repressor TUP1 in Candida albicans. Biosci Rep. 30:391–404.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rahmani AH, Al Zohairy MA, Aly SM and Khan

MA: Curcumin: A potential candidate in prevention of cancer via

modulation of molecular pathways. Biomed Res Int. 2014:7616082014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Prakobwong S, Gupta SC, Kim JH, Sung B,

Pinlaor P, Hiraku Y, Wongkham S, Sripa B, Pinlaor S and Aggarwal

BB: Curcumin suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in

human biliary cancer cells through modulation of multiple cell

signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis. 32:1372–1380. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fujisawa S, Atsumi T, Ishihara M and

Kadoma Y: Cytotoxicity, ROS-generation activity and

radical-scavenging activity of curcumin and related compounds.

Anticancer Res. 24:563–569. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Calabrese V, Bates TE, Mancuso C,

Cornelius C, Ventimiglia B, Cambria MT, Di Renzo L, De Lorenzo A

and Dinkova-Kostova AT: Curcumin and the cellular stress response

in free radical-related diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 52:1062–1073.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Trujillo J, Chirino YI, Molina-Jijón E,

Andérica-Romero AC, Tapia E and Pedraza-Chaverrí J: Renoprotective

effect of the antioxidant curcumin: Recent findings. Redox Biol.

1:448–456. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pan Y, Wang Y, Cai L, Cai Y, Hu J, Yu C,

Li J, Feng Z, Yang S, Li X and Liang G: Inhibition of high

glucose-induced inflammatory response and macrophage infiltration

by a novel curcumin derivative prevents renal injury in diabetic

rats. Br J Pharmacol. 166:1169–1182. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kim BH, Lee ES, Choi R, Nawaboot J, Lee

MY, Lee EY, Kim HS and Chung CH: Protective effects of curcumin on

renal oxidative stress and lipid metabolism in a rat model of type

2 diabetic nephropathy. Yonsei Med J. 57:664–673. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pang XF, Zhang LH, Bai F, Wang NP, Garner

RE, McKallip RJ and Zhao ZQ: Attenuation of myocardial fibrosis

with curcumin is mediated by modulating expression of angiotensin

II AT1/AT2 receptors and ACE2 in rats. Drug Des Devel Ther.

9:6043–6054. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang MT, Lysz T, Ferraro T, Abidi TF,

Laskin JD and Conney AH: Inhibitory effects of curcumin on in vitro

lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase activities in mouse epidermis.

Cancer Res. 51:813–819. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shen L and Ji HF: Insights into the

inhibition of xanthine oxidase by curcumin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

19:5990–5993. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ben P, Liu J, Lu C, Xu Y, Xin Y, Fu J,

Huang H, Zhang Z, Gao Y, Luo L and Yin Z: Curcumin promotes

degradation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and suppresses its

enzyme activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol.

11:179–186. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tzankova V, Gorinova C, Kondeva-Burdina M,

Simeonova R, Philipov S, Konstantinov S, Petrov P, Galabov D and

Yoncheva K: Antioxidant response and biocompatibility of

curcumin-loaded triblock copolymeric micelles. Toxicol Mech

Methods. 27:72–80. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sun YM, Zhang HY, Chen DZ and Liu CB:

Theoretical elucidation on the antioxidant mechanism of curcumin: A

DFT study. Org Lett. 4:2909–2911. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hao CX, Su YJ, Wang QJ, et al: Inhibition

effect of curcumin on AP-1 DNA binding activity increased in the

kidney of experimental diabetic rats. J Med Pest Control.

27:417–418. 2011.(In Chinese).

|

|

38

|

Shin GT, Khanna A, Ding R, Sharma VK,

Lagman M, Li B and Suthanthiran M: In vivo expression of

transforming growth factor-beta1 in humans: Stimulation by

cyclosporine. Transplantation. 65:313–318. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Siemionow M, Ozer K, Izycki D, Unsal M and

Klimczak A: A new method of bone marrow transplantation leads to

extention of skin allograft survival. Transplant Proc. 37:pp.

2309–2314. 2005; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sereno J, Rodrigues-Santos P, Vala H,

Rocha-Pereira P, Alves R, Fernandes J, Santos-Silva A, Carvalho E,

Teixeira F and Reis F: Transition from cyclosporine-induced renal

dysfunction to nephrotoxicity in an in vivo rat model. Int J Mol

Sci. 15:8979–8997. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Buffoli B, Pechánová O, Kojsová S,

Andriantsitohaina R, Giugno L, Bianchi R and Rezzani R: Provinol

prevents CsA-induced nephrotoxicity by reducing reactive oxygen

species, iNOS, and NF-kB expression. J Histochem Cytochem.

53:1459–1468. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tirkey N, Kaur G, Vij G and Chopra K:

Curcumin, a diferuloylmethane, attenuates cyclosporine-induced

renal dysfunction and oxidative stress in rat kidneys. BMC

Pharmacol. 5:152005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hu Y, Mou L, Yang F, Tu H and Lin W:

Curcumin attenuates cyclosporine A-induced renal fibrosis by

inhibiting hypermethylation of the klotho promoter. Mol Med Rep.

14:3229–3236. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhang H and Sun SC: NF-κB in inflammation

and renal diseases. Cell Biosci. 5:632015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang F, Yin J, Lu Z, Zhang G, Li J, Xing

T, Zhuang S and Wang N: Limb ischemic preconditioning protects

against contrast-induced nephropathy via renalase. EBioMedicine.

9:356–365. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang F, Zhang G, Xing T, Lu Z, Li J, Peng

C, Liu G and Wang N: Renalase contributes to the renal protection

of delayed ischaemic preconditioning via the regulation of

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. J Cell Mol Med. 19:1400–1409. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|