Introduction

Scalp-ear-nipple (SEN) syndrome is a rare,

autosomal-dominant disorder that commonly presents as cutis aplasia

of the scalp, minor anomalies of the external ears, digits and

nails, and malformation of the breast (1). In mice, homozygous deficiency of the

lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (Lef-1) gene results in the lack

of whiskers and the arrest of hair-follicle development, lack of

mammary glands and edentulism, indicating that Lef-1 may serve as a

potential candidate gene for treating SEN syndrome (2). Ten mutations in the broad-complex,

tramtrack and bric a brac (BTB) domain of potassium-channel

tetramerization-domain-containing 1 (KCTD1) have been identified in

ten families with SEN syndrome of European, Brazilian and North

African background (3). This

conserved domain regulates transcriptional activity, suggesting it

may serve a key role in KCTD1 protein function during ectodermal

development (3).

Transcription factor AP-2α-knockout mice exhibit a

number of severe developmental phenotypes, including neural tube,

body wall and craniofacial abnormality (4). Dominant AP-2α mutant Doarad results

in a missense mutation that affects the

Y58F59P60P61P62Y63

(PY) motif in the transactivation domain of AP-2α, causing a

misshapen malleus, incus and stapes (5). This P59L mutation in AP-2α leads to

increased transcriptional activation of AP-2α (5). Patients with Char syndrome have three

mutations in the basic DNA-binding domain and a PY motif in the

activation domain of the AP-2β gene, causing dominant-negative

effects. In the USA, individuals with Char syndrome who have a PY

motif P62R mutation in AP-2β have a higher incidence rate (10 of

14) of patent ductus arteriosus, but milder hand and facial

abnormal phenotypes compared with individuals with DNA-binding

domain mutations in AP-2α (6,7).

Point mutations or insertions/deletions in the conserved

DNA-binding domain in AP-2α, encoded by exons 4 and 5, cause the

majority of branchio-oculo-facial syndrome (BOFS) cases (8). BOFS is associated with >25

different mutations in AP-2α (9–12).

Therefore, AP-2α mutants have been associated with certain

developmental abnormalities.

Our previous study (13) demonstrated that KCTD1 binds with

AP-2α and decreases its transcriptional activity. KCTD15 is

associated with the KCTD1 protein in the KCTD family. It is likely

that KCTD15 functions during embryogenesis by interacting with the

activation domain of AP-2α to inhibit neural crest induction

(14). Individuals with KCTD15

mutations exhibit developmental defects in neural crest derivatives

and the torus lateralis (TLa) in the central nervous system,

resulting in a significant decrease in normal growth rates

(15,16). Moreover, both AP-2α and KCTD1

regulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. AP-2α directly interacts with

adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), stabilizing interactions between

APC and β-catenin, attenuating interactions between β-catenin and

transcription factor-4 in the nucleus and suppressing TOPFLASH

luciferase reporter activity in human colorectal cancer cells

(17). AP-2α-interacting protein

KCTD1 directly binds to β-catenin, enhances β-catenin

ubiquitination and degradation, which is dependent on casein kinase

1/glycogen synthase kinase-3β-mediated phosphorylation of

β-catenin, and inhibits the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway (18).

The present study aimed to investigate whether KCTD1

and AP-2α protein mutants reciprocally regulate their interactions

and inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The results

demonstrated that BTB domain mutations in KCTD1 were not associated

with AP-2α. The P59A mutation in the PY motif of AP-2α prevented

binding with KCTD1, but the majority of BTB domain mutations in

KCTD1 and PY motif mutations in AP-2α resulted in inhibited Wnt

pathway-responsive TOPFLASH reporter gene expression levels.

Wild-type KCTD1 suppressed the transcriptional activity of AP-2α

P60A and P61R to repress TOPFLASH reporter gene expression levels.

Moreover, wild-type KCTD1 and AP-2α downregulated β-catenin

expression levels and decreased the viability of SW480 cells. These

findings highlighted the importance of AP-2α and KCTD1 regulation

in maintaining a normal tissue phenotype.

Materials and methods

Plasmid generation

Recombinant overexpressing plasmids pCMV-Myc-AP-2α,

pCMV-HA-KCTD1, pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 and pEGFP-C1-AP-2α were generated as

previously described (13,18). The mutants AP-2α P61R and KCTD1

P20S, A30E, P31R, H33P and H33Q were also generated as previously

described (13,18). The KCTD1 mutants P31L, P31H, G62D,

D69E and H74P and AP-2α mutants P59A, P60A and 4A

(P59AP60AP61AY62A) were modified by PCR-based site-directed

mutagenesis and cloned into pCMV-Myc plasmids. Mutated primers are

presented in Table I. Reporter

vectors A2 and TOPFLASH were generated as previously described

(18,19). Eight recombinant plasmids were

sequenced using the Sanger method, in order to verify mutant site

points (Sangon Biotech, Co., Ltd.) (Fig. S1).

| Table I.Mutants of KCTD1 and AP-2α and their

PCR primers. |

Table I.

Mutants of KCTD1 and AP-2α and their

PCR primers.

| Gene | Mutant | Primer sequence

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| KCTD1 | P20S | F: TCTACTCCAGCACAACTCACA |

|

|

| R:

TGTGAGTTGTGCTGGAGTAGA |

|

| A30E | F:

ATCCAATGAGCCTGTCCACAT |

|

|

| R:

ATGTGGACAGGCTCATTGGAT |

|

| P31R | F:

CAATGCGCGTGTCCACATTGA |

|

|

| R:

TCAATGTGGACACGCGCATTG |

|

| P31L | F:

CAATGCGCTTGTCCACATTGA |

|

|

| R:

TCAATGTGGACAAGCGCATTG |

|

| P31H | F:

CAATGCGCATGTCCACATTGA |

|

|

| R:

TCAATGTGGACATGCGCATTG |

|

| H33P | F: CCATTGATGTGGGCGGCCAC |

|

|

| R:

GTGGCCGCCCACATCAATGG |

|

| H33Q | F:

CGCCTGTCCAAATTGATGTGG |

|

|

| R:

CCACATCAATTTGGACAGGCG |

|

| G62D | F:

TTTGATGATACAGAGCCCATTG |

|

|

| R:

CAATGGGCTCTGTATCATCAAA |

|

| D69E | F: AAGTCTCAAACAGCACTATTTC |

|

|

| R:

GAAATAGTGCTGTTTGAGACTT |

|

| H74P | F: CCTATTTCATTGACAGAGATGG |

|

|

| R:

CCATCTCTGTCAATGAAATAGG |

| AP-2α | P61R | F:

TTCCCCCCAAGATACCAGCCT |

|

|

| R:

AGGCTGGTATCTTGGGGGGAA |

|

| P59A | F:

ATACTTCGCCCCACCCTACC |

|

|

| R:

GGTAGGGTGGGGCGAAGTAT |

|

| P60A | F:

ACTTCCCCGCACCCTACCAG |

|

|

| R:

CTGGTAGGGTGCGGGGAAGT |

|

| 4A | F:

ATACTTCGCCGCAGCCGCCCAGCCT |

|

|

| R:

AGGCTGGGCGGCTGCGGCGAAGTAT |

Cell culture and transfection

SW480, 293 and HeLa cells (American Type Culture

Collection) were cultured in complete DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA). All cells were maintained with 10% fetal calf serum

(HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences), 2 mM glutamine, 10 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5%

CO2. The cells were transiently transfected with

different amounts of plasmid DNA (1 µg for luciferase reporter

assays; 6 µg for immunofluorescence analysis; 20 µg for

co-immunoprecipitation; Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) using

Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 6 h. The cells were collected 24–30 h

following transfection for subsequent experimentation.

Luciferase reporter assays

The 293 cells were cultured and transiently

transfected with 0.3 µg reporter plasmids A2 (generous gift of

Professor Trevor Williams) or pTOPFLASH (Clontech Laboratories,

Inc.) (18) and the indicated

plasmids (0.3 µg pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 and/or 0.3 µg of pCMV-Myc-AP-2α) in

12-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent as previously

described (20). Briefly, 0.1 µg

pCMV-LacZ plasmid (19) was

co-transfected in each well to measure transfection efficiency as

an internal β-galactosidase control. The total amount of 1 µg

plasmid DNA in each well was maintained by adding empty vector

pCMV-Myc (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) to each transfection.

β-galactosidase and luciferase activities were assessed 24 h after

transfection using a Promega Luciferase Assay system (Promega

Corporation) and a Turner TD20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs). The

luciferase activity is normalized relative to the β-galactosidase

control. A total of three experimental repeats were performed.

Immunofluorescence localization

analysis

HeLa cells were grown to ~70% confluence on glass

coverslips and transiently transfected with3 µg GFP-AP-2α and 3 µg

Myc-KCTD1 mutants or 3 µg Myc-AP-2α mutants and 3 µg HA-KCTD1. At

30 h post-transfection, cells were collected for immunofluorescence

staining, as previously described (19). Primary antibodies included Anti-Myc

mouse monoclonal antibody (clone. no. 9E10; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-HA rabbit polyclonal antibody (clone

no. Y-11) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 1:200 dilution for 1

h at 4°C. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. A27034)

and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. A-11005)

secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc. and used at 1:500 dilution for 45 min at

4°C. Hoechst 33258 (1 µg/ml) was used to stain the nuclei

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 5 min at 4°C. The fluorescence

signals were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss

AG).

Co-immunoprecipitation

The 293 cells were grown to ~80% confluence and

transiently transfected with 10 µg Myc-AP-2α and 10 µg Myc-KCTD1 in

10-cm dishes. At 30 h after transfection, cells were collected and

lysed as previously described (13). The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer

[50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2; 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100; 1%

(w/v) sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% (w/v) SDS] supplemented with

protease inhibitors. The cellular lysates were precleared with

protein A/G plus agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4°C

for 1 h, and then immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-KCTD1

polyclonal antibodies (21) and

protein A/G plus agarose. The immunoprecipitates were washed four

times for 15 min each in 1 ml 1% Triton buffer by keeping gentle

agitation and then centrifuged at 500 × g for 3 min at 4°C. The

immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE on 13% gels and detected

with mouse anti-Myc tag monoclonal antibody at 1:2,000 dilution

overnight at 4°C as described in the following Western blot

section. Pre-immune rabbit IgG (cat. no. sc-2027; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) was used as a negative control. The

quantification of immunoprecipitated bands was analyzed using

ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.48v, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Western blotting

SW480 cells were transiently transfected with

pCMV-Myc-AP-2α and/or pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 expression plasmids. At 24 h

after post-transfection, cells were collected and lysed in RIPA

buffer. The protein concentration of whole-cell extracts was

measured using a BCA assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Total protein (10 µg/lane) was resolved by SDS-PAGE on 12%

gels, then transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) at 4°C for 2 h at 100 V. The membrane was blocked with TBS

buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5; 0.9% (w/v) NaCl] with 1% BSA

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at 4°C. After blocking, the

membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against Myc-tag

(clone. no. 9E10; 1:2,000), β-catenin (E-5, 1:1,000), cyclin D1

(CCND1; clone. no. HD11; 1:1,000) and GAPDH (clone. no. 6C5;

1:5,000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C and

washed with TBS and 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 for 1 h. After washing, the

membrane was then incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. sc-2005,

1:7,500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at room temperature for 45

min followed by washing five times for 1 h. The signal was detected

with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and visualized with tanon-5200

system (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.).

Cell viability assays

A total of 3×103 transfected SW480 cells

were grown at 37°C in 96-well plates in octuplicate. Cell viability

was analyzed 24 h after transfection by adding 1 mg/ml MTT to each

well, followed by incubation for 4 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the

formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µl DMSO. The absorbance was

measured at 490 nm using a spectrophotometer. To detect the effects

of AP-2α and KCTD1 proteins on the sensitivity of SW480 cells to

sorafenib, SW480 cells were transfected and subsequently treated

with 20 µM cisplatin (DDP) for 24 h; viability was assessed by MTT,

aforementioned.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

statistical software (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc.). Data are presented

as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Significant

differences were determined using Student's t-test to compare two

groups, and two-way ANOVA to compare three or more groups.

Multi-group comparisons were analyzed using Tukey's post hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

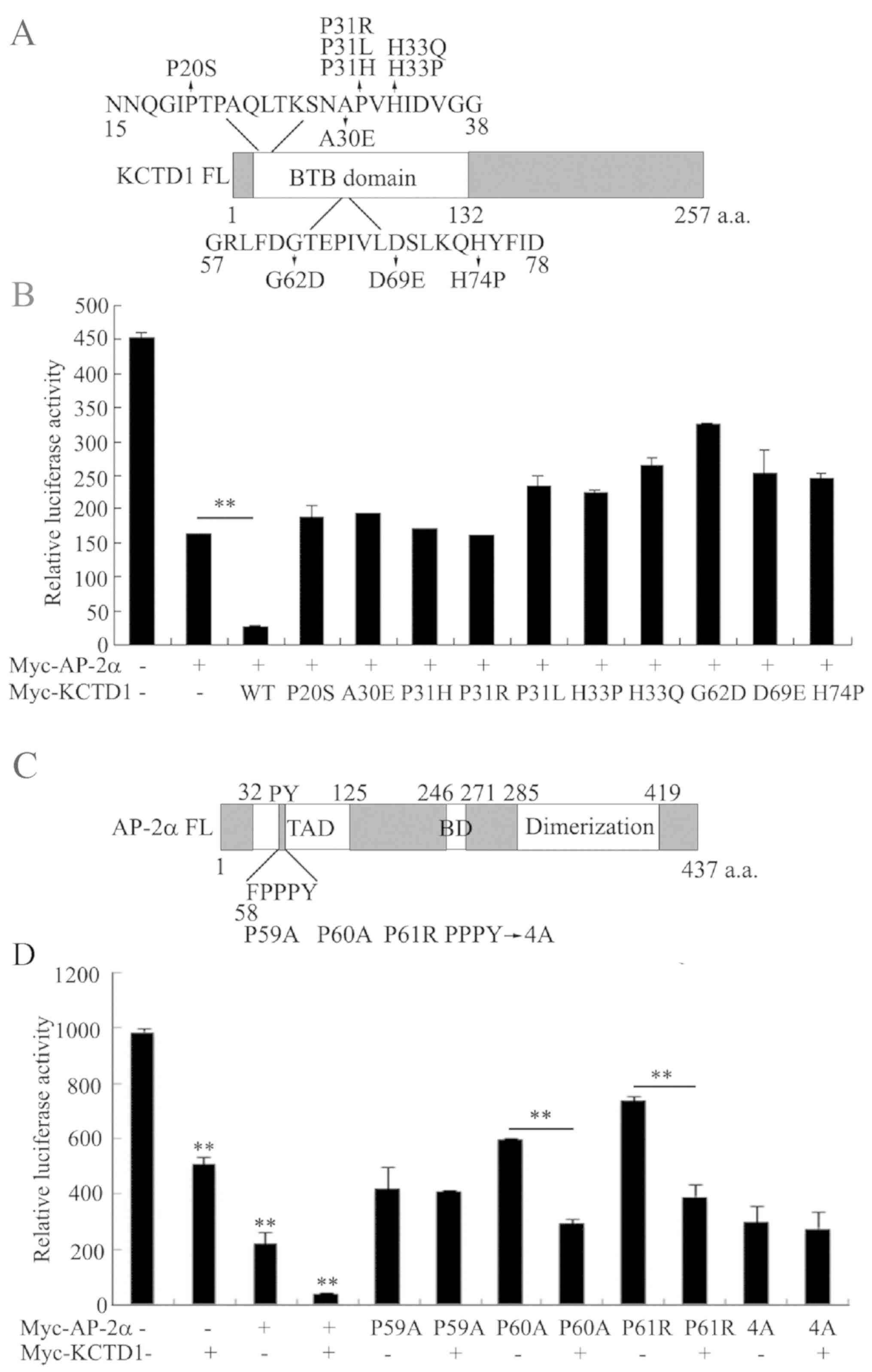

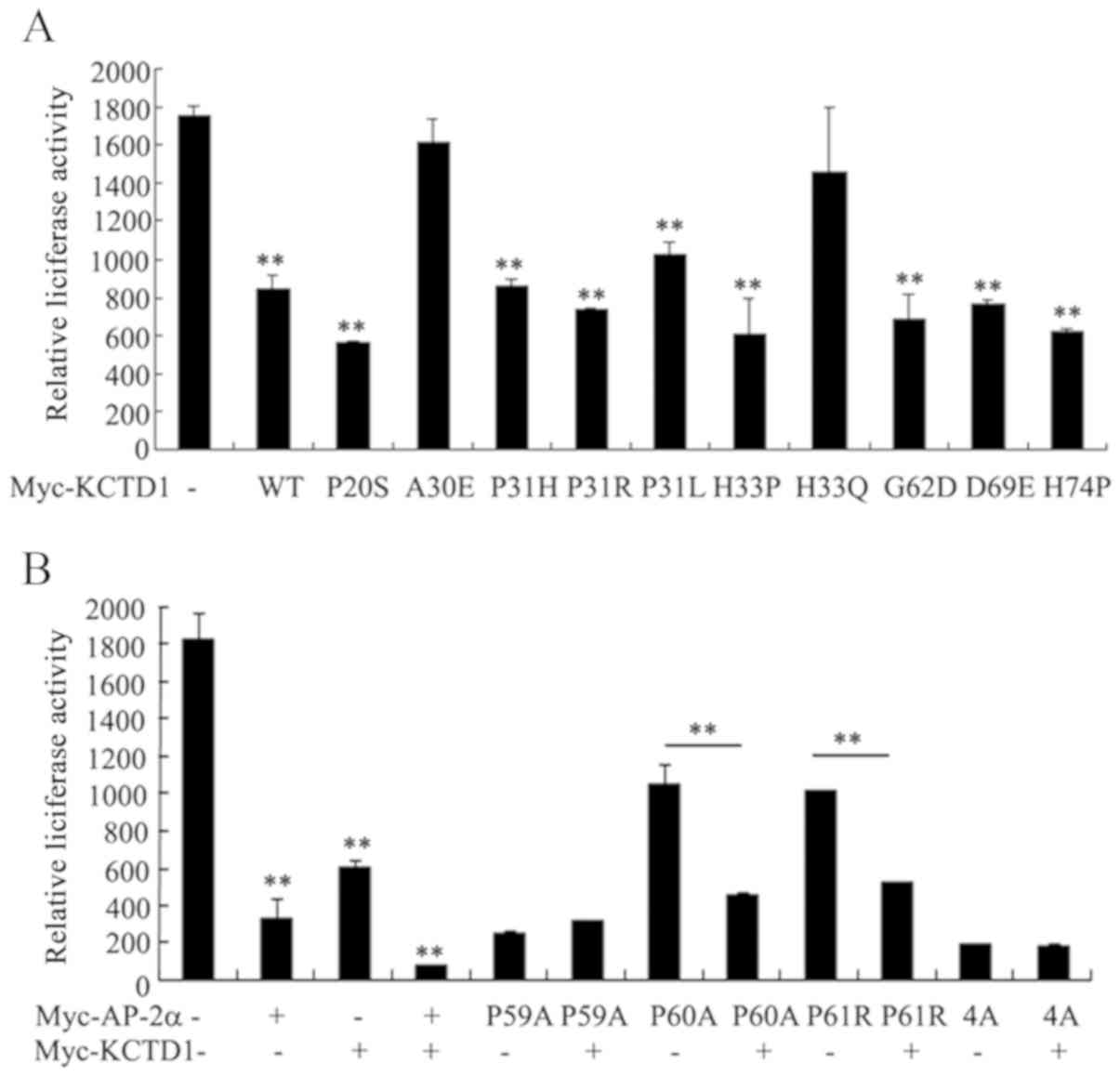

Known KCTD1 mutants have no inhibitory

effect on the transcriptional activity of AP-2α, and KCTD1 does not

repress the transcriptional activity of the AP-2αP59A mutation

All the known KCTD mutations in the BTB-domain lead

to SEN syndrome, whereas mutations in AP-2α possibly cause Char

syndrome. As the BTB domain of KCTD1 binds to the activation domain

of AP-2α and suppresses its transcriptional activity (13), it was investigated whether these

KCTD1 mutations affect AP-2α transcriptional activity (Fig. 1A). An A2 reporter plasmid with

three AP-2 binding sites was transiently transfected in the

presence or absence of pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 wild-type or KCTD1 mutants

into 293 cells. Consistent with previous results (13) wild-type KCTD1 overexpression

significantly decreased A2 luciferase activity, whereas 10 KCTD1

mutants had no effect on the transcriptional inhibition of AP-2α,

compared with wild-type KCTD1 (Fig.

1B).

The present study also investigated the effect of

KCTD1 on the transcriptional activity of AP-2α with mutations in

the PY motif (Fig. 1C), which is

required for a normal developmental phenotype (5). KCTD1 markedly repressed A2 luciferase

activity of AP-2α P60A and P61R, but not of AP-2α P59A or 4A,

indicating that the AP-2α mutation of amino acid 59 abrogated KCTD1

regulation (Fig. 1D). Taken

together, these data revealed that pathogenic mutations in KCTD1 or

AP-2α affect their regulatory mechanisms.

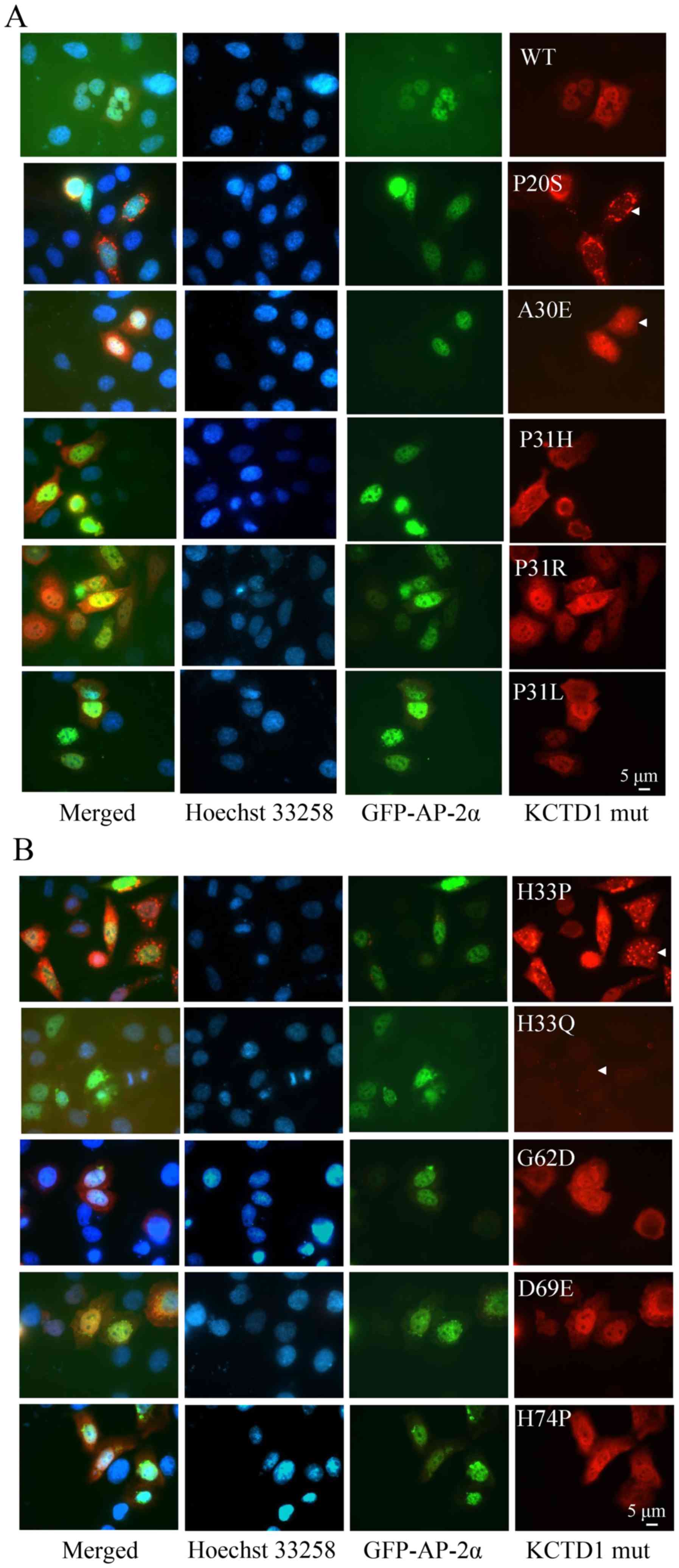

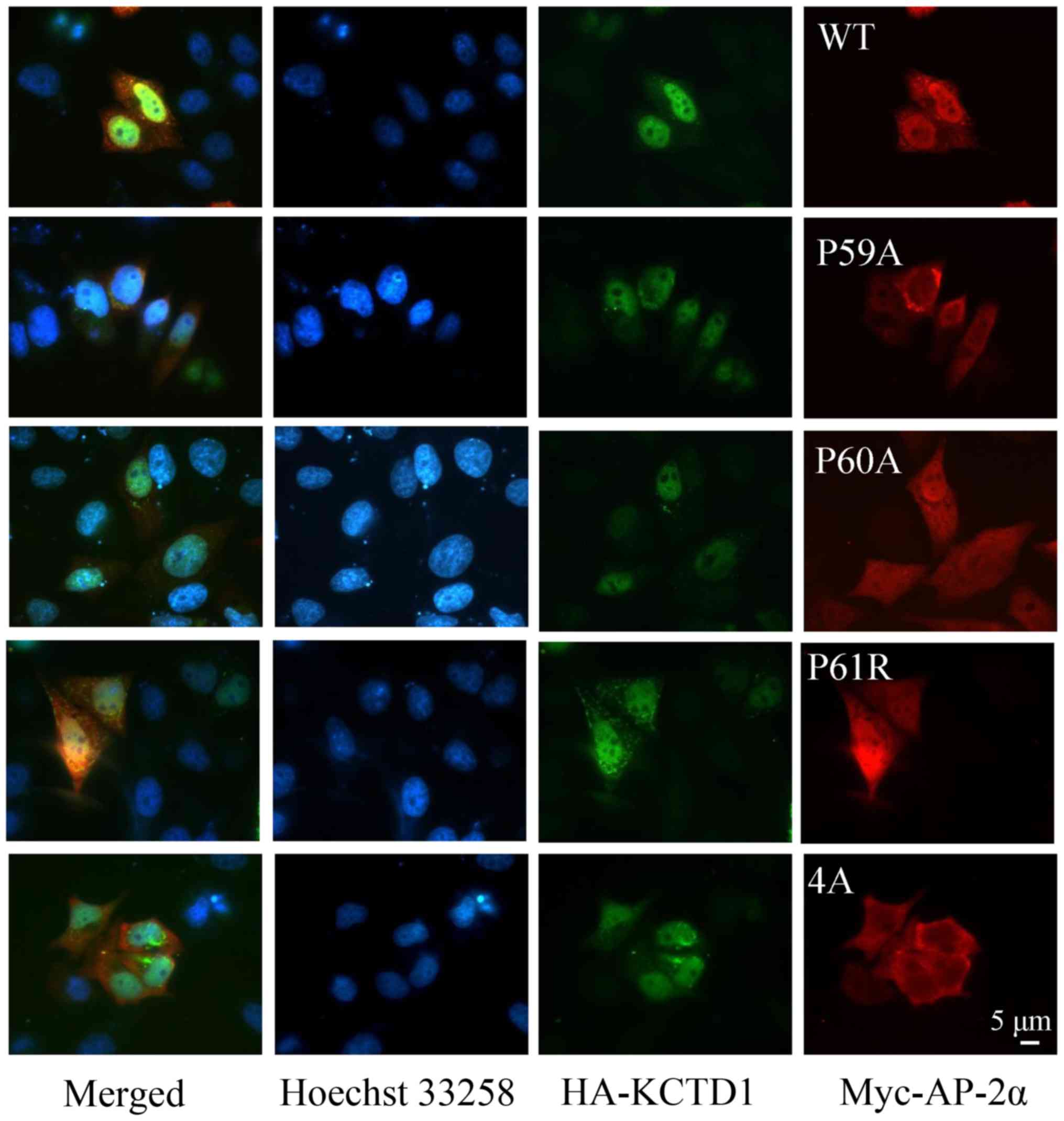

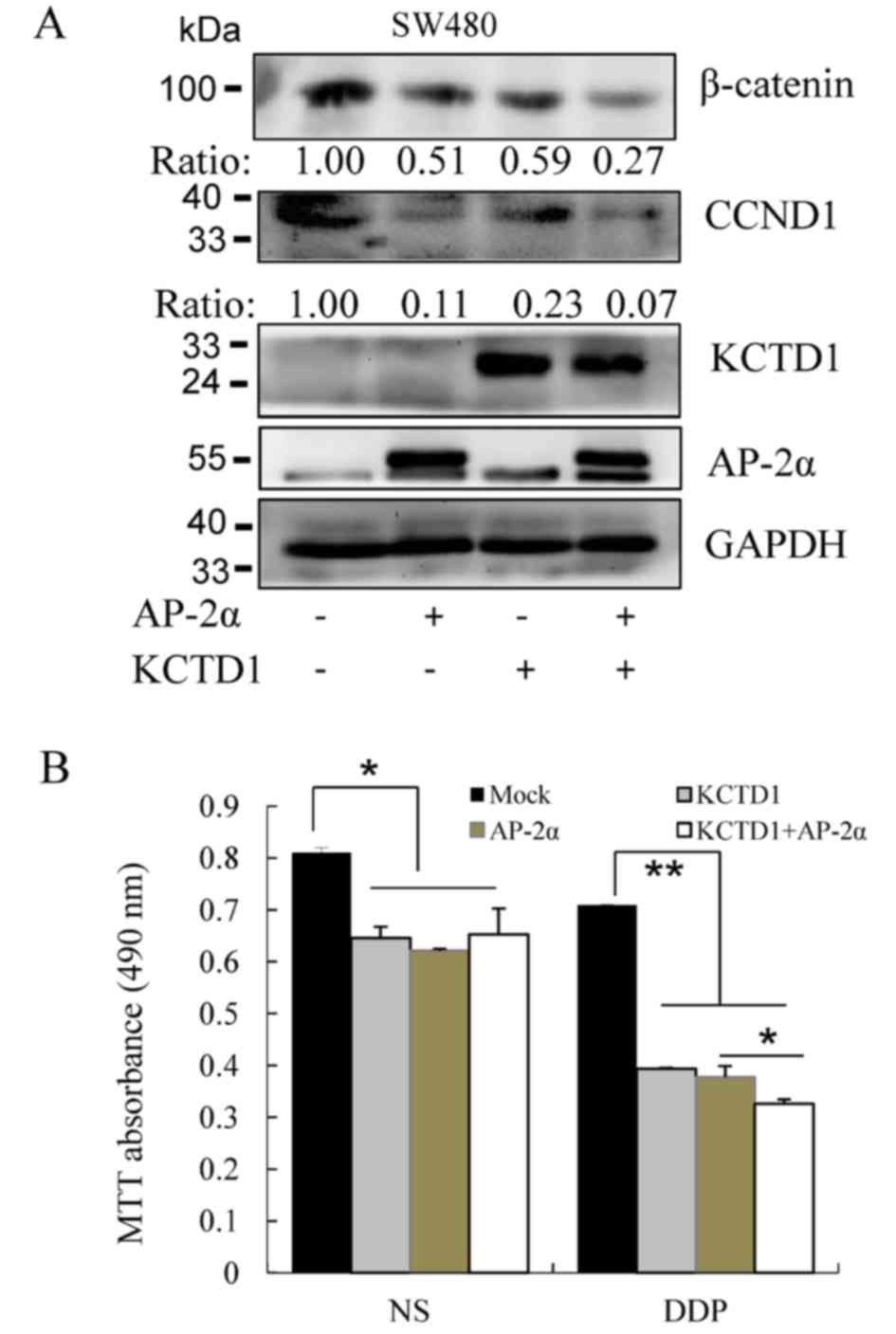

Altered cellular localization of KCTD1

and AP-2α mutants, compared with wild-type

Plasmids encoding mutant KCTD1 and AP-2α proteins

were transfected into 293 cells to investigate the localization of

both mutant proteins using immunofluorescence (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). It was observed that

wild-type KCTD1 localized with wild-type AP-2α, consistent with

previously reported results (13).

The KCTD1 mutants (A30E, P31R, P31L, H33Q, G62D, D69E and H74P)

were distributed throughout the whole cell, predominantly exhibited

strong fluorescence in the nucleus, and co-localized with AP-2α

(Fig. 2). However, localization of

KCTD1 P20S was detected in the nuclear membrane. KCTD1 P31H was

localized in the nuclear membrane and the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). KCTD1 H33P clustered in an

aggregated pattern in a significant portion of the cells (Fig. 2B). These data suggested that

wild-type KCTD1 and its mutant proteins primarily localized in the

nucleus, but KCTD1 mutants with mutated amino acids 20 and 31

localized to the nuclear membrane. In addition, wild-type AP-2α and

mutant P60A and P61R protein appeared to demonstrate strong

fluorescence in the nucleus and co-localized with KCTD1 protein.

However, the AP-2α P59A and 4A proteins were predominantly detected

in the cytoplasm and showed no overlap with KCTD1 protein (Fig. 3). These observations were

indicative of altered localization of KCTD1 and AP-2α.

| Figure 2.Cellular localization of KCTD1

mutants. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the

expression plasmids pEGFP-C1-AP-2α and pCMV-Myc-wild-type KCTD1 or

pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 mutants. (A) Localization of wild-type AP-2α and

wild-type KCTD1 or KCTD1 mutants including P20S, A30E, P31R, P31L,

P31H. (B) Localization of wild-type AP-2α and KCTD1 mutants

including H33P, H33Q, G62D, D69E and H74P. Images were captured at

36 h after transfection. Green, GFP-AP-2α expression; blue, Hoechst

33258 nuclear stain; red, KCTD1 WT and mutants; yellow indicates

overlapping expression. GFP, green fluorescent protein; KCTD1,

potassium-channel tetramerization-domain-containing 1; mut, mutant;

wt, wild-type. |

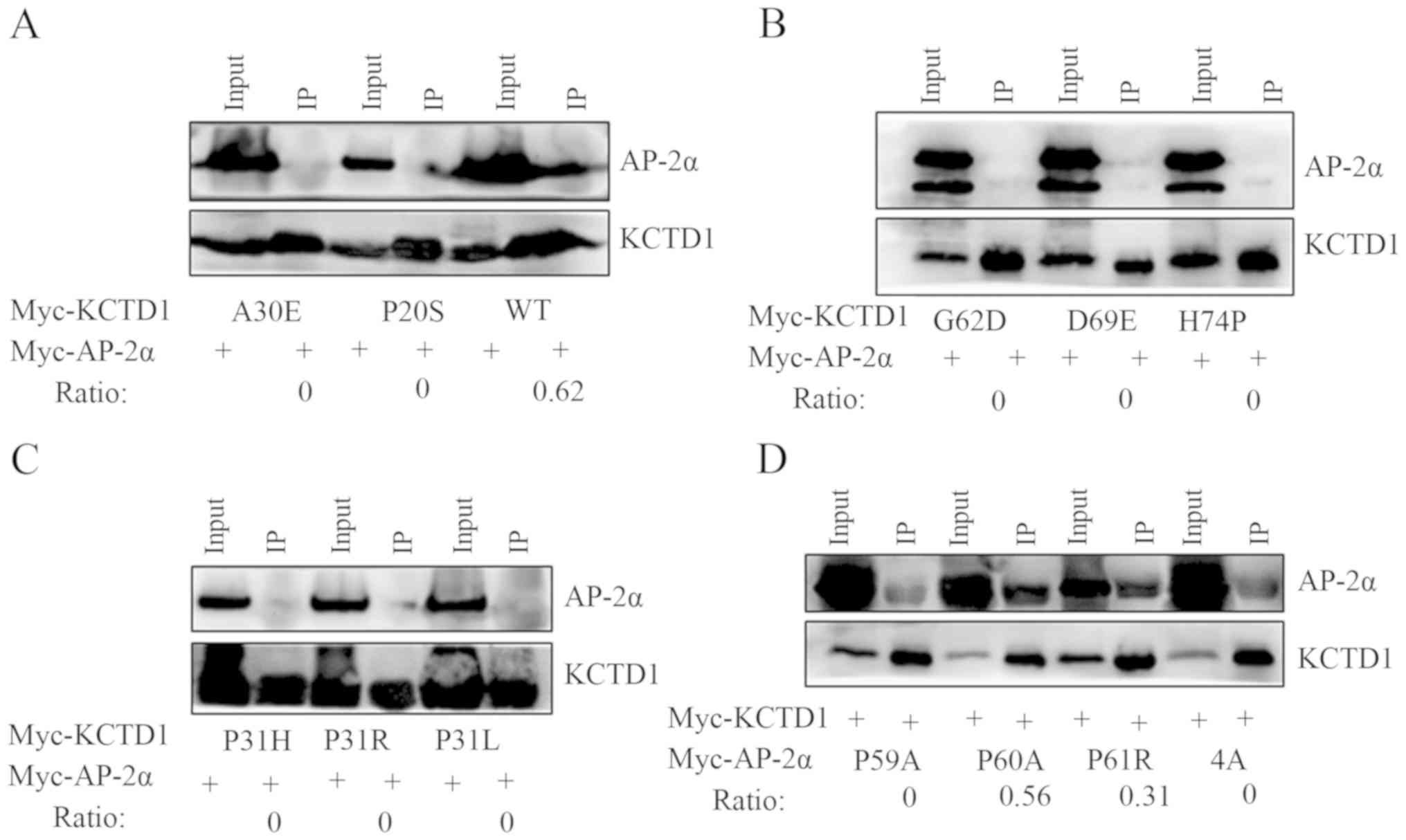

Protein interactions are altered

between KCTD1 mutants/wild-type AP-2α and wild-type KCTD1/AP-2α

P59A mutant

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis was performed to

investigate in vitro interactions between AP-2α and KCTD1

mutants. Anti-KCTD1 antibodies immunoprecipitated the wild-type

KCTD1/AP-2α complex but did not precipitate the KCTD1 mutant/AP-2α

protein complex (Fig. 4A-C).

Moreover, consistent with luciferase assay results, KCTD1 formed a

complex with AP-2α P60A and P61R, but not with AP-2α P59A or 4A

(Fig. 4D). These results

demonstrated that the KCTD1 mutants did not interact with AP-2α,

although some nucleic co-localization was observed for the AP-2α

and KCTD1 mutants, which indicated that KCTD1 mutations in the BTB

domain reduce its suppressive effects on AP-2α. However, KCTD1

continued to inhibit the transcriptional activation of AP-2α P60A

and P61R and formed a complex through protein-protein

interaction.

Differential regulation of KCTD1 and

AP-2α mutants on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

Wnt/β-catenin signaling serves a key role in

embryonic development and various diseases including bone disease

including osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome, cardiometabolic

disease and Parkinson's disease (22–25).

The present study investigated the effects of KCTD1 mutants on the

canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The TOPFLASH reporter

plasmid was transfected into 293 cells in the presence or absence

of pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 wild-type or KCTD1 mutants. The results

demonstrated that wild-type KCTD1 overexpression markedly

suppressed the Wnt pathway-responsive TOPFLASH reporter gene

activity (Fig. 5A). In addition,

the majority of KCTD1 mutants strongly inhibited the

transcriptional activity of the TOPFLASH reporter. KCTD1 A30E or

H33Q mutants had no effect on the transcriptional activity of the

TOPFLASH reporter, but eight other KCTD1 mutants significantly

decreased the transcription activity of the TOPFLASH reporter gene

to a similar extent as the wild-type KCTD1. In the H33Q KCTD1

mutant, the change from polar and charged His33 to a polar residue,

Gln (Q), did not inhibit TOPFLASH reporter activity. By contrast,

the change from His to Pro in the H33P mutant inhibited the

TOPFLASH reporter activity. Collectively, these results suggested

that Ala 30 and His 33 were important for KCTD1-mediated regulation

of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig.

5A). These data indicate that the pathogenic mechanisms

underlying certain KCTD1 mutants are primarily due to suppressed

Wnt/β-catenin signaling, resulting in specific abnormal phenotypes

in SEN syndrome.

AP-2α has been reported to inhibit TOPFLASH reporter

activity in a manner similar to KCTD1 (17,18).

AP-2α P59A and AP-2α 4A suppressed TOPFLASH activity to a similar

degree as wild-type AP-2α (Fig.

5B); AP-2α P60A and P61R also partially inhibited TOPFLASH

reporter activity. Notably, inhibition of TOPFLASH reporter

activity by AP-2α P60A and P61R was enhanced in cells

co-transfected with wild-type KCTD1, but KCTD1 had no effect on the

TOPFLASH reporter activity of AP-2α P59A or 4A (Fig. 5B). These results supported the

hypothesis that the AP-2α P59A mutant downregulates the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is unaffected by KCTD1.

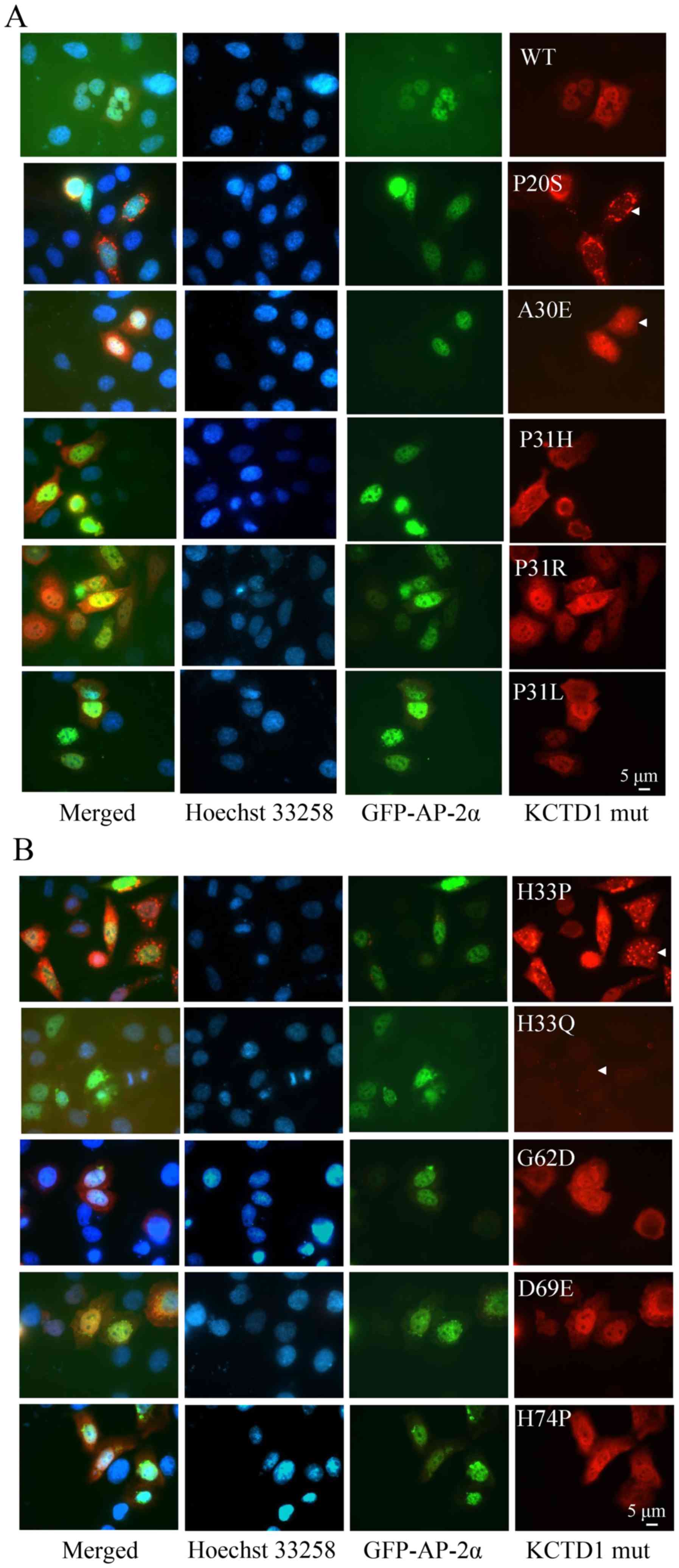

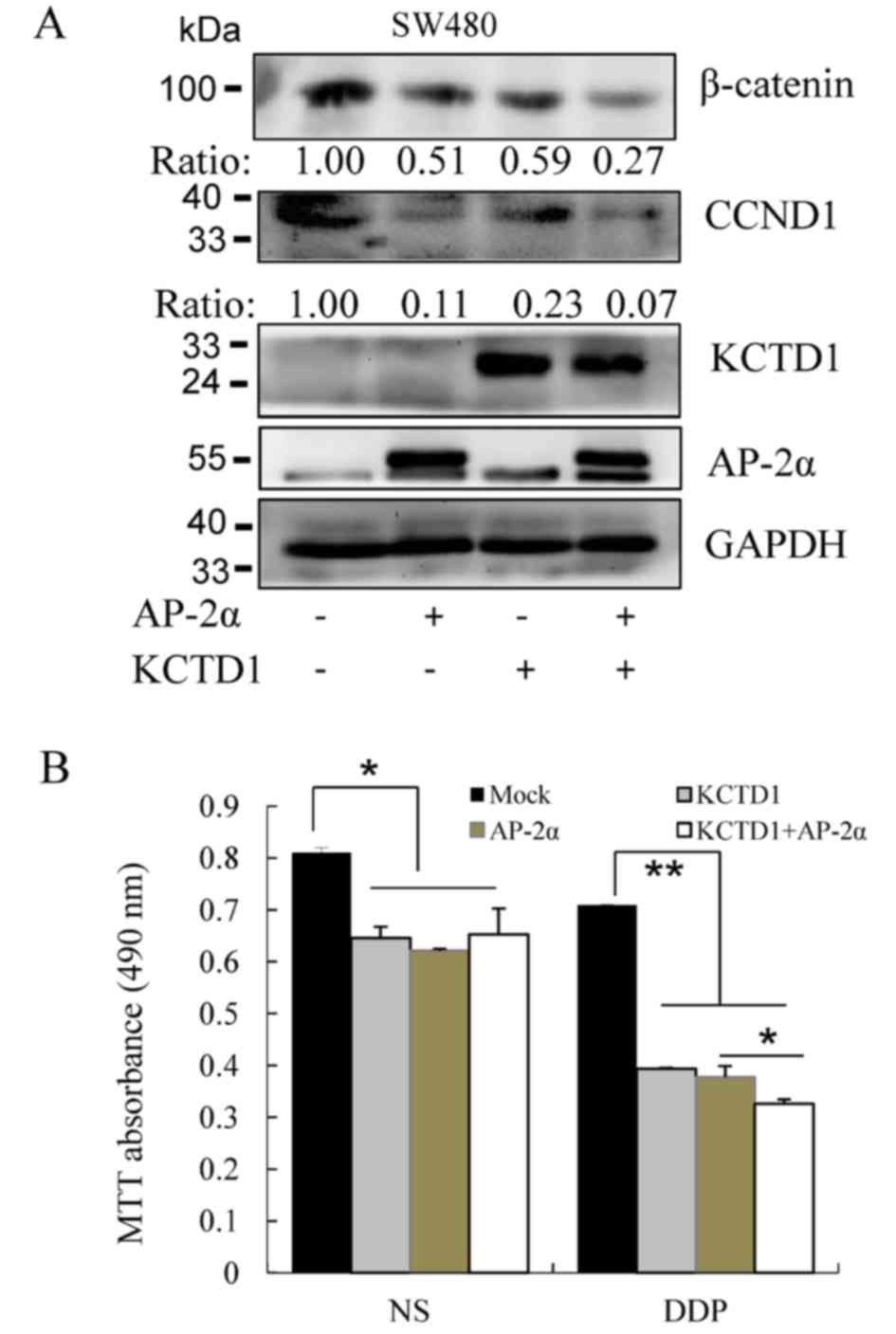

Finally, western blotting was performed to measure

the influence of AP-2α and KCTD1 proteins on the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway. KCTD1 and AP-2α overexpression (individually and in

combination) decreased β-catenin expression levels (Fig. 6A); downstream CCND1 expression

levels were also downregulated. Moreover, KCTD1 and AP-2α decreased

the survival of the SW480 cells, and 20 µM chemotherapeutic drug

cisplatin (DDP) exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect on the

viability of SW480 cells transfected with KCTD1 and/or AP-2α,

compared with the normal saline (NS) group (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrated that

KCTD1 and AP-2α downregulated β-catenin expression levels in the

canonical Wnt pathway and inhibited SW480 cell viability,

suggesting KCTD1 and AP-2α might regulate these syndromes through

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

| Figure 6.KCTD1 and AP-2α decrease SW480 cell

viability by downregulating β-catenin expression levels. (A) SW480

cells were transiently transfected with pCMV-Myc (Mock),

pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 and/or pCMV-Myc-AP-2α plasmids. At 24 h after

transfection, total cell lysates were harvested and detected by

western blotting using mouse monoclonal antibodies against

β-catenin, Myc-tag, CCND1 and GAPDH. GAPDH served as a loading

control for protein normalization. (B) Effects of overexpressed

KCTD1, AP-2α or DDP treatment on SW480 cells. SW480 cells were

transiently transfected with pCMV-Myc-KCTD1 and/or pCMV-Myc-AP-2α

plasmids and treated with or without 20 µM DDP for 24 h. Cell

viability was determined by MTT assays and absorbance was measured

at 490 nm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with controls (the Mock

group or the AP-2α group). KCTD1, potassium-channel

tetramerization-domain-containing 1; CCND1, cyclin D1; DDP,

cisplatin; NS, normal saline. |

Discussion

The BTB domain is crucial for transcriptional

regulation; proteins with a BTB domain primarily function as

transcriptional repressors (26–28).

BTB proteins, such as Bcl-6 and promyelocytic leukemia zinc-finger

(PLZF), are involved in a number of developmental processes, such

as limb formation, gastrulation, ovary morphogenesis, eye

development and hematopoietic stem cell fate determination

(29–33). The Bcl6 mutant does not interact

with co-repressors through its BTB domain, which results in

defective B cell proliferation and survival, disrupted formation of

germinal centers and suppressed affinity maturation of

immunoglobulin (34).

Specifically, residues 33–35 form the floor of the pocket and

residues 63, 64 and 66–68 form each wall in the secondary structure

of PLZF BTB domain (35). All

known KCTD mutants in SEN syndrome are caused by missense

mutations, and the BTB pocket is formed by a number of residues

(3). KCTD1 mutations associated

with SEN syndrome abrogate KCTD1 transcriptional repression

activity on transcription factor AP-2α (13). These missense mutations result in

the loss of KCTD1 function in a dominant-negative manner. This is

consistent with the present study results, which demonstrated that

alterations in the KCTD1 BTB domain had no effect on the

transcriptional repression of AP-2α owing to a lack of interaction,

despite a degree of co-localization. Notably, the present study

revealed that KCTD1 H33P was localized in a punctate pattern in the

cells. These findings were consistent with a previous study in

which amyloid precursor protein (APP) exhibited a punctate pattern

of immunofluorescence indicative of internalization from the cell

surface to an endosomal compartment (36), indicating that KCTD1 H33P may serve

important roles in internalization by endocytosis. To investigate

the function of KCTD1 mutants in maintaining a normal tissue

phenotype, as well as the regulatory association between KCTD1

mutants and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, normal cell lines, such as 293

cells, were selected as previously described (18). The majority of KCTD1 BTB domain

mutants suppressed the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, indicating that

substitutions of amino acids in cases of SEN syndrome do not wholly

disrupt transcriptional repression caused by BTB domain mutations

in KCTD1, although only KCTD1 A30E and H33Q displayed unchanged

TOPFLASH reporter activity. It was hypothesized that KCTD1

mutations that cause SEN syndrome may result in abnormal regulation

of AP-2α and developmental defects.

Char syndrome is characterized by patent ductus

arteriosis, facial dysmorphism and incurving fifth fingers

(37). The PY motif in AP-2

protein family is associated with Char syndrome as autosomal

dominant diseases (7). The PY

motif is conserved in the transcription activation domain of AP-2

proteins and KCTD1 binds to this transactivation domain. KCTD1

inhibited the transcriptional activation of AP-2α by three-fold,

whereas KCTD1 only suppressed the transcriptional activity of AP-2α

P60A and P61R by one-half, and did not decrease the transcriptional

activity of AP-2α P59A (Fig. 1D),

indicating that regulatory the AP-2α mutation could been influenced

by differential regulation of KCTD1.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway serves a key

role in embryonic developmental processes (22,38,39)

and carcinogenesis (40–42). Truncations in APC are frequently

found in familial adenomatous polyposis, a dominantly inherited

disease characterized by polyps in the colon and rectum (43,44).

Mutations in β-catenin and APC cause sporadic colon cancer and

other types of tumor, such as liver cancer and intraductal

papillary neoplasms of the bile duct (45–47).

KCTD1 directly binds to β-catenin, enhances its degradation and

inhibits the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (18). In the present study, AP-2α and

KCTD1 downregulated β-catenin expression levels in individual

transfection experiments and decreased SW480 cell viability,

although both of these proteins exhibited stronger inhibitory

effects on β-catenin protein levels and cell viability in

co-transfection experiments, potentially due to the negative

regulatory association between AP-2α and KCTD1. The chemotherapy

drug cisplatin enhanced the influence of both genes on SW480 cell

viability.

In summary, the present data demonstrated that KCTD1

mutants causing SEN syndrome did not bind AP-2α and exhibited no

inhibitory effects on AP-2α, and that KCTD1 was not associated with

AP-2α P59A-induced Char syndrome. The interactions between KCTD1

mutants/wild-type AP-2α or wild-type KCTD1/AP-2α mutants were

abrogated as a potential effect of altered localization, including

KCTD1 mutants P20S, P31H, H33P and AP-2α mutants P59A and 4A.

However, the majority of KCTD1 and AP-2α mutants inhibited TOPFLASH

reporter activity to different extents, and wild-type KCTD1 and

AP-2α downregulated β-catenin expression levels and decreased SW480

cell viability. Further investigation using an animal model is

required to fully elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of these

proteins in SEN and Char syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Limin Li (Hunan

Normal University, Changsha, China) for critical editing of the

manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by The National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81872256, 81770389

and 81272190), and The Cooperative Innovation Center of Engineering

and New Products for Developmental Biology of Hunan Province (grant

no. 20134486).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are

available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XD designed the present study and wrote the

manuscript. LH, LC, WH, ZY, LY, XL, QL and JQ performed the

experiments and analyzed the data. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Finlay AY and Marks R: An hereditary

syndrome of lumpy scalp, odd ears and rudimentary nipples. Br J

Dermatol. 99:423–430. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

van Steensel MA, Celli J, van Bokhoven JH

and Brunner HG: Probing the gene expression database for candidate

genes. Eur J Hum Genet. 7:910–919. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Marneros AG, Beck AE, Turner EH, McMillin

MJ, Edwards MJ, Field M, de Macena Sobreira NL, Perez ABA, Fortes

JAR, Lampe AK, et al: Mutations in KCTD1 cause scalp-ear-nipple

syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 92:621–626. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang J, Hagopian-Donaldson S, Serbedzija

G, Elsemore J, Plehn-Dujowich D, McMahon AP, Flavell RA and

Williams T: Neural tube, skeletal and body wall defects in mice

lacking transcription factor AP-2. Nature. 381:238–241. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ahituv N, Erven A, Fuchs H, Guy K,

Ashery-Padan R, Williams T, de Angelis MH, Avraham KB and Steel KP:

An ENU-induced mutation in AP-2alpha leads to middle ear and ocular

defects in doarad mice. Mamm Genome. 15:424–432. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sletten LJ and Pierpont ME: Familial

occurrence of patent ductus arteriosus. Am J Med Genet. 57:27–30.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhao F, Weismann CG, Satoda M, Pierpont

ME, Sweeney E, Thompson EM and Gelb BD: Novel TFAP2B mutations that

cause char syndrome provide a genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J

Hum Genet. 69:695–703. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li H, Sheridan R and Williams T: Analysis

of TFAP2A mutations in branchio-oculo-facial syndrome indicates

functional complexity within the AP-2α DNA-binding domain. Hum Mol

Genet. 22:3195–3206. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Milunsky JM, Maher TA, Zhao G, Roberts AE,

Stalker HJ, Zori RT, Burch MN, Clemens M, Mulliken JB, Smith R and

Lin AE: TFAP2A mutations result in branchio-oculo-facial syndrome.

Am J Hum Genet. 82:1171–1177. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Milunsky JM, Maher TM, Zhao G, Wang Z,

Mulliken JB, Chitayat D, Clemens M, Stalker HJ, Bauer M, Burch M,

et al: Genotype-phenotype analysis of the branchio-oculo-facial

syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 155A. 22–32. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dumitrescu AV, Milunsky JM, Longmuir SQ

and Drack AV: A family with branchio-oculo-facial syndrome with

primarily ocular involvement associated with mutation of the TFAP2A

gene. Ophthalmic Genet. 33:100–106. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Thomeer HG, Crins TT, Kamsteeg EJ,

Buijsman W, Cruysberg JR, Knoers NV and Cremers CWRJ: Clinical

presentation and the presence of hearing impairment in

branchio-oculo-facial syndrome: A new mutation in the TFAP2A gene.

Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 119:806–814. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ding X, Luo C, Zhou J, Zhong Y, Hu X, Zhou

F, Ren K, Gan L, He A, Zhu J, et al: The interaction of KCTD1 with

transcription factor AP-2alpha inhibits its transactivation. J Cell

Biochem. 106:285–295. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zarelli VE and Dawid IB: Inhibition of

neural crest formation by Kctd15 involves regulation of

transcription factor AP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:2870–2875.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Heffer A, Marquart GD, Aquilina-Beck A,

Saleem N, Burgess HA and Dawid IB: Generation and characterization

of Kctd15 mutations in zebrafish. PLoS One. 12:e01891622017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dutta S and Dawid IB: Kctd15 inhibits

neural crest formation by attenuating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling

output. Development. 137:3013–3018. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li Q and Dashwood RH: Activator protein

2alpha associates with adenomatous polyposis coli/beta-catenin and

inhibits beta-catenin/T-cell factor transcriptional activity in

colorectal cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 279:45669–45675. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li X, Chen C, Wang F, Huang W, Liang Z,

Xiao Y, Wei K, Wan Z, Hu X, Xiang S, et al: KCTD1 suppresses

canonical Wnt signaling pathway by enhancing β-catenin degradation.

PLoS One. 9:e943432014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ding X, Fan C, Zhou J, Zhong Y, Liu R, Ren

K, Hu X, Luo C, Xiao S, Wang Y, et al: GAS41 interacts with

transcription factor AP-2beta and stimulates AP-2beta-mediated

transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:2570–2578. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ding X, Yang Z, Zhou F, Wang F, Li X, Chen

C, Li X, Hu X, Xiang S and Zhang J: Transcription factor AP-2α

regulates acute myeloid leukemia cell proliferation by influencing

hoxa gene expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 45:1647–1656. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ding XF, Luo C, Ren KQ and Zhang J, Zhou

JL, Hu X, Liu RS, Wang Y, Gao X and Zhang J: Characterization and

expression of a human KCTD1 gene containing the BTB domain, which

mediates transcriptional repression and homomeric interactions. DNA

Cell Biol. 27:257–265. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Clevers H: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in

development and disease. Cell. 127:469–480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Baron R and Kneissel M: WNT signaling in

bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments.

Nat Med. 19:179–192. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gay A and Towler DA: Wnt signaling in

cardiovascular disease: Opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin

Lipidol. 28:387–396. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ng L, Kaur P, Bunnag N, Suresh J, Sung

ICH, Tan QH, Gruber J and Tolwinski NS: WNT signaling in disease.

Cells. 8:8262019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li X, Peng H, Schultz DC, Lopez-Guisa JM,

Rauscher FJ III and Marmorstein R: Structure-function studies of

the BTB/POZ transcriptional repression domain from the

promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger oncoprotein. Cancer Res.

59:5275–5282. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fedele M, Benvenuto G, Pero R, Majello B,

Battista S, Lembo F, Vollono E, Day PM, Santoro M, Lania L, et al:

A novel member of the BTB/POZ family, PATZ, associates with the

RNF4 RING finger protein and acts as a transcriptional repressor. J

Biol Chem. 275:7894–7901. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hoatlin ME, Zhi Y, Ball H, Silvey K,

Melnick A, Stone S, Arai S, Hawe N, Owen G, Zelent A and Licht JD:

A novel BTB/POZ transcriptional repressor protein interacts with

the fanconi anemia group C protein and PLZF. Blood. 94:3737–3747.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kelly KF and Daniel JM: POZ for

effect--POZ-ZF transcription factors in cancer and development.

Trends Cell Biol. 16:578–587. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kojima S, Hatano M, Okada S, Fukuda T,

Toyama Y, Yuasa S, Ito H and Tokuhisa T: Testicular germ cell

apoptosis in Bcl6-deficient mice. Development. 128:57–65.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Shaffer AL, Yu X, He Y, Boldrick J, Chan

EP and Staudt LM: BCL-6 represses genes that function in lymphocyte

differentiation, inflammation, and cell cycle control. Immunity.

13:199–212. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Barna M, Hawe N, Niswander L and Pandolfi

PP: Plzf regulates limb and axial skeletal patterning. Nat Genet.

25:166–172. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti

G, Manova K, Sukhwani M, Orwig KE, Wolgemuth DJ and Pandolfi PP:

Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells.

Nat Genet. 36:653–659. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Huang C, Hatzi K and Melnick A:

Lineage-specific functions of Bcl-6 in immunity and inflammation

are mediated by distinct biochemical mechanisms. Nat Immunol.

14:380–388. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ahmad KF, Engel CK and Prive GG: Crystal

structure of the BTB domain from PLZF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

95:12123–12128. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Carey RM, Balcz BA, Lopez-Coviella I and

Slack BE: Inhibition of dynamin-dependent endocytosis increases

shedding of the amyloid precursor protein ectodomain and reduces

generation of amyloid beta protein. BMC Cell Biol. 6:302005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Char F: Peculiar facies with short

philtrum, duck-bill lips, ptosis and low-set ears-a new syndrome?

Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 14:303–305. 1978.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Marston DJ, Roh M, Mikels AJ, Nusse R and

Goldstein B: Wnt signaling during caenorhabditis elegans embryonic

development. Methods Mol Biol. 469:103–111. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Munoz-Descalzo S, Hadjantonakis AK and

Arias AM: Wnt/ß-catenin signalling and the dynamics of fate

decisions in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem (ES) cells.

Semin Cell Dev Biol. 47-48:101–109. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang B, Tian T, Kalland KH, Ke X and Qu Y:

Targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling for cancer immunotherapy. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 39:648–658. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang W, Smits R, Hao H and He C:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling in liver cancers. Cancers (Basel).

11:9262019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jung YS and Park JI: Wnt signaling in

cancer: Therapeutic targeting of Wnt signaling beyond β-catenin and

the destruction complex. Exp Mol Med. 52:183–191. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y,

Ando H, Horii A, Koyama K, Utsunomiya J, Baba S and Hedge P:

Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer

patients. Science. 253:665–669. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Nakamura Y, Nishisho I, Kinzler KW,

Vogelstein B, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Ando H, Horii A and Nagase H:

Mutations of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in familial

polyposis coli patients and sporadic colorectal tumors. Princess

Takamatsu Symp. 22:285–292. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Suraweera N, Robinson J, Volikos E,

Guenther T, Talbot I, Tomlinson I and Silver A: Mutations within

Wnt pathway genes in sporadic colorectal cancers and cell lines.

Int J Cancer. 119:1837–1842. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Colnot S: Focusing on beta-catenin

activating mutations to refine liver tumor profiling. Hepatology.

64:1850–1852. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Fujikura K, Akita M, Ajiki T, Fukumoto T,

Itoh T and Zen Y: Recurrent mutations in APC and CTNNB1 and

activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in intraductal papillary

neoplasms of the bile duct: A whole exome sequencing study. Am J

Surg Pathol. 42:1674–1685. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|