Introduction

Breast cancer carries a considerable global burden

due to its high morbidity and mortality rates (1). Acknowledged as the most common cancer

affecting the female population worldwide, its incidence reached an

estimated 300,590 new cases, with 43,700 associated deaths (in both

sexes), in the United States by the year 2023 (2). In 2019, the Jordanian Cancer Registry

revealed that breast cancer represented 38.5% of all cancer cases

among female Jordanian patients (3). Histologically, invasive ductal

carcinoma of no special type constitutes the predominant subtype,

comprising 40–75% of all invasive breast carcinoma cases (4). Otherwise, there are other special

subtypes, each characterized by unique architectural,

immunohistochemical and prognostic features. One such rare subtype,

adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC), mimics the histology of salivary

gland tumors and is typically found in the salivary glands of the

head and neck region (5). Breast

cancer was shown to be the second most common site of AdCC

following the head and neck in a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology

and End Results database report (6). This variant represents <0.1% of all

breast cancer subtypes (7). AdCC

comprises three distinct subtypes: Classic, solid basaloid and

high-grade transformation; each exhibiting unique clinical

behaviors and prognostic outcomes (8). Although AdCC of the breast shares

features with its more aggressive salivary gland counterpart, and

typically lacks expression of estrogen receptors (ERs),

progesterone receptors (PRs) and human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 (HER2/neu), AdCC of the breast is nonetheless

characterized by an indolent clinical course and a favorable

prognosis (6,9). AdCC typically remains localized within

the breast region, with extremely rare lymph node involvement and

sparse occurrence of hematogenous metastases, primarily to the

lungs (10,11). In such cases, recurrence often

occurs after an extended period, commonly several years

post-resection (12). The present

study reports the case of a patient diagnosed with cT3N0M0

triple-negative AdCC of the breast. Notably, the clinical course

and tumor spread possessed a unique pattern, with rapid progression

over a span of 6 months, with the eventual clinical deterioration

and mortality of the patient.

Case report

In March 2022, a 77-year-old female patient

(Gravida, 22; Para, 12+10), was referred to the King Hussein Cancer

Center (Amman, Jordan) complaining of a painless, gradually

enlarging right breast mass associated with left nipple inversion

and tenderness for a 6-month duration. Apart from this, the

systemic review of symptoms did not yield any significant findings.

The patient was known to have a history of hypertension, diabetes

mellitus type II, osteoarthritis and chronic kidney disease. The

surgical history included an open cholecystectomy and hysterectomy

with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy performed at the age of 57

years related to post-menopausal bleeding due to non-malignant

causes. Menarche occurred at the age of 13 years, and the patient

had been in menopause for the past 22 years. There was no family

history of malignancies. The patient was a second-hand smoker with

no hormonal replacement therapy usage. During physical examination,

a mass measuring 4×5 cm was identified in the mid-upper quadrant

area of the right breast, situated 5 cm away from the nipple

areolar complex. The mass was mobile, without any concurrent skin

alterations or retraction of the right nipple. Notably, palpable

lymph nodes were observed in the ipsilateral axilla. Otherwise,

examination of the left breast, left axilla and bilateral

supraclavicular region revealed no notable findings.

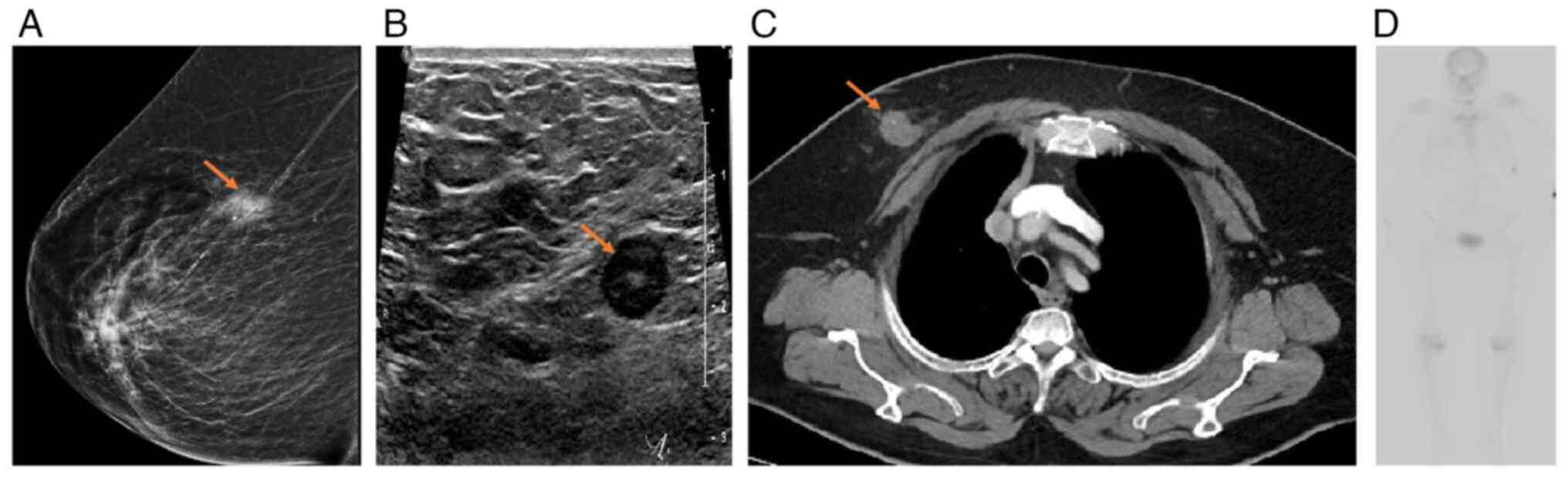

A mammogram demonstrated an irregular spiculated

hyperdense mass at the mid upper right breast ~9.5 cm away from the

nipple (Fig. 1A). Subsequent breast

ultrasound (U/S) imaging revealed an irregular, heterogeneous

hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins at the mid upper right

breast measuring 1.7×1.3×2 cm, with no concerning findings in the

left breast (Fig. 1B). Lymph node

involvement was notably absent in both axillae. Further staging

computed tomography (CT) scans revealed an ill-defined soft-tissue

lesion consistent with the previously identified right-sided breast

mass (Fig. 1C). Bone scans were

free of any active lesions, and there was no evidence of metastases

to nearby or distant organs (Fig.

1D). Additionally, CT scans revealed prominent subpectoral and

mediastinal lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side, measuring 0.8 cm

and 1.2 cm, respectively (Fig.

S1). A prior tru-cut biopsy performed outside our center

revealed Nottingham histological grade I invasive ductal carcinoma

and a ductal carcinoma in situ, characterized by a

cribriform pattern with intermediate nuclear grade (13). Repeated diagnostic testing was

performed to confirm the histological subtype and staging, to guide

the multidisciplinary tumor board management plan.

In May 2022, the patient underwent a wide local

excision along with additional excision of deep margins and a

biopsy of the sentinel lymph nodes. The procedure was carried out

successfully and there were no observed immediate or delayed

post-operative complications. Subsequent surgical pathology reports

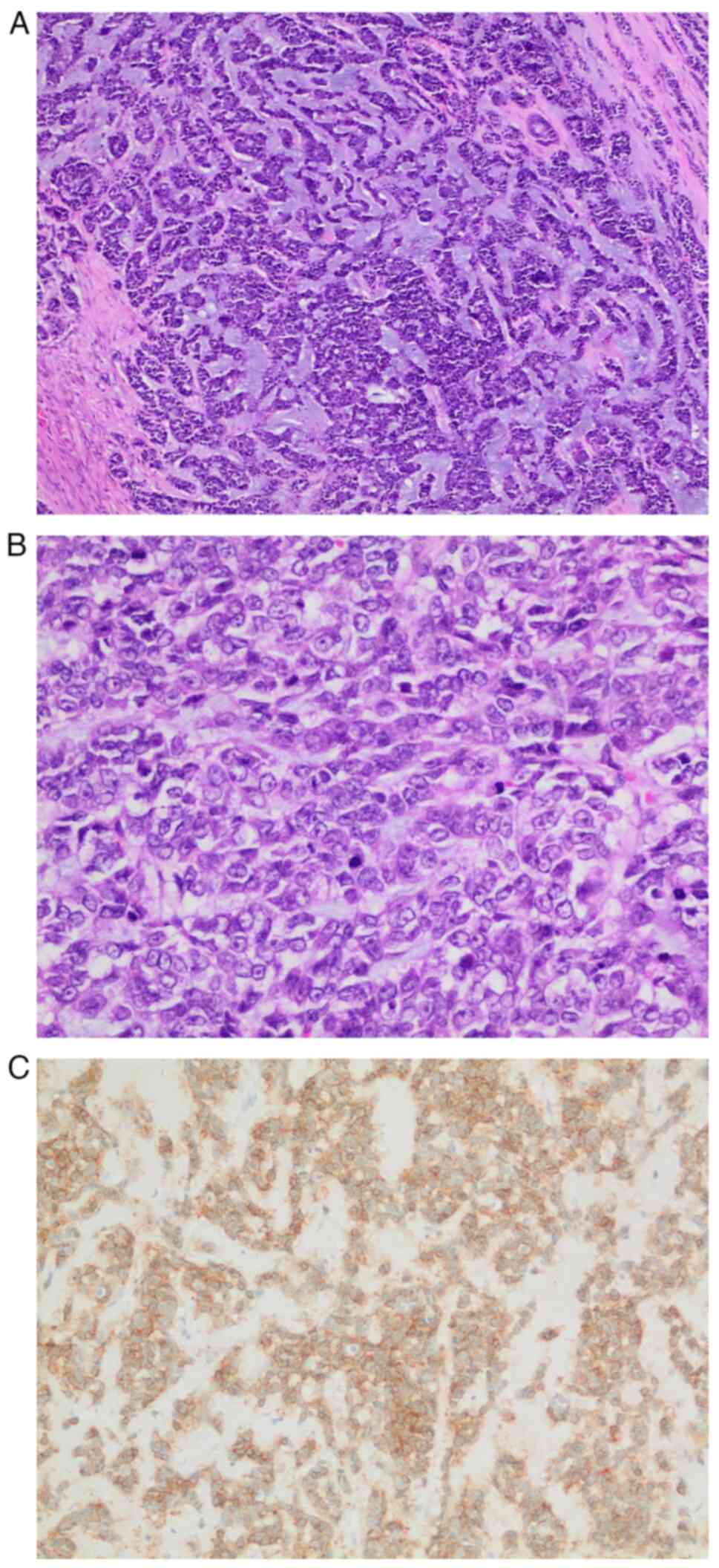

revealed a 6.4-cm-diameter tumor composed of basaloid epithelial

cells arranged in solid sheets, nests and tubules. Formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens were prepared by fixing

in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h at room temperature,

followed by paraffin embedding. Sections of 4-µm thickness were

cut, placed in an oven at 60°C for 15 min, stained with H&E

(hematoxylin for 8 min and eosin for 2 min at room temperature),

and examined using a light microscope. In some areas, the tumor

showed a lower grade component with evident myxoid stroma (Fig. 2A), whereas in other areas, the tumor

showed a higher nuclear grade with numerous mitotic figures

(Fig. 2B). The surgical margins

were free of tumor with the closest margin being the superior

margin at 0.3 cm. Perineural invasion was not observed. The tumor

was positive for c-Kit (Fig. 2C),

negative for S100 (Fig. S2) and

tumor protein p63 (p63) (Fig. S3),

and negative for chromogranin (Fig.

S4), synaptophysin (Fig. S5),

ER (Fig. S6) and HER2/neu

(Fig. S7), immunostaining

(procedure details described in Table

SI). The solid areas represented >30% of the tumor. The

diagnosis was consistent with solid-basaloid AdCC of the breast,

Nottingham grade II (13). Ductal

carcinoma in situ cribriform, intermediate grade was also

observed. The tumor was staged as pT3N0, per the American Joint

Committee on Cancer 8th edition staging system (14), indicating a large primary tumor size

with no extension to adjacent viscera or nearby lymph nodes.

The case was discussed at the multidisciplinary

tumor board meeting, and adjuvant radiation therapy was planned. At

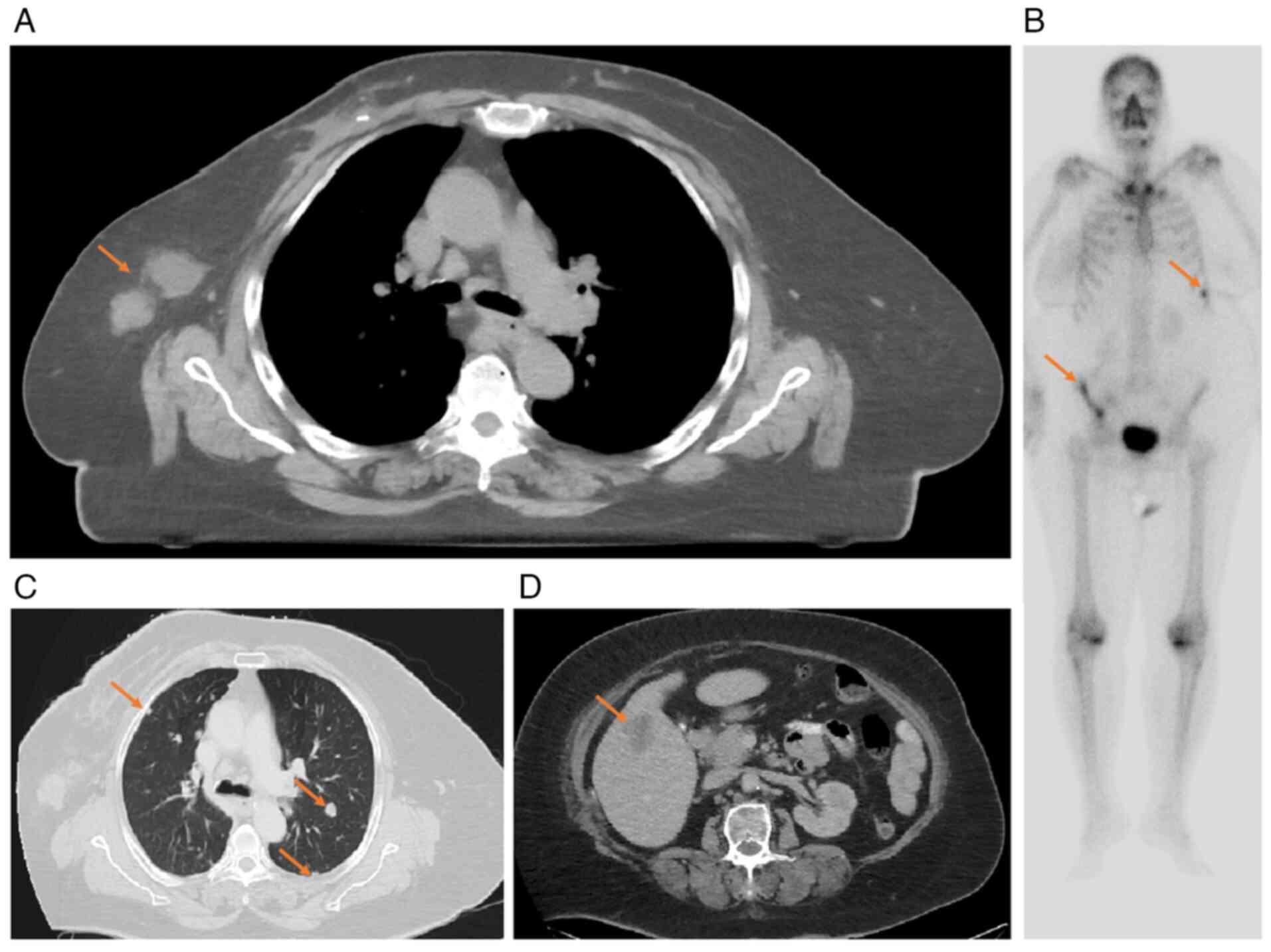

1.5 months post-resection, upon evaluation at the Radiation

Oncology Clinic at King Hussein Cancer Center for a CT simulation

scan, a suspected lesion was detected in the axillary region, with

a slightly atypical appearance (Fig.

3A). A U/S scan was requested, which revealed the presence of a

new complex mass at the right axillary tail. Subsequently, a

U/S-guided biopsy was performed, which confirmed the recurrence of

known primary AdCC. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, carried

out as aforementioned, of the axillary lesion revealed negative ER,

weakly positive (2%) PR and negative HER2/neu expression, a

proliferation index (Ki-67) of 50%, a limited number of cells

staining positive for p63 and focal positivity for cytokeratin 8/18

(data not shown).

Given the unexpected findings, new staging work up

was performed including bone scan revealed new multiple active

lesions in the right iliac bone and ribs (Fig. 3B) and CT scan which shown

significant disease progression manifested by new innumerable

metastatic pulmonary nodules in both lungs, new liver metastases,

new right axillary metastatic lymph nodes, new minimal right

pleural effusion and thickening suggestive of metastatic deposits

(Fig. 3C and D).

Prompted by the discovery of the new findings, the

treatment plan included the initiation of chemotherapy sessions

using weekly paclitaxel (144 mg) with a 20% dose reduction from the

first cycle due to the age of the patient. The patient completed a

total of three cycles. However, a multitude of complications

occurred due to factors relating to the advanced age of the

patient, comorbid conditions, side effects of chemotherapeutic

agents and tumor infiltration. The patient presented to the

Emergency Department on six occasions complaining of severe lower

back pain, an episode of falling down and recurrent urinary tract

infections. A CT scan revealed a non-displaced fracture in the

right superior iliac crest and an inferior iliac crest fracture.

Despite being on oral Tramal 100 mg twice daily, Tramal 50 mg every

8 h as needed, paracetamol 1,000 mg every 6 h, and gabapentin 300

mg three times daily, the patient continued to experience

significant pain. Consequently, the patient required multiple

admissions and palliative pain interventions, including haloperidol

1 mg IV every 4 h as needed, a continuous morphine sulfate infusion

at 0.2 mg/h, and morphine 2 mg/2 ml IV every 2 h as needed for

breakthrough pain. She also received multiple courses of

intravenous antibiotics, with the most recent being meropenem 1 g

diluted in 100 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride, infused over 30 min

every 8 h. Unfortunately, chemotherapy sessions were postponed and

subsequently discontinued due to a worsening clinical condition

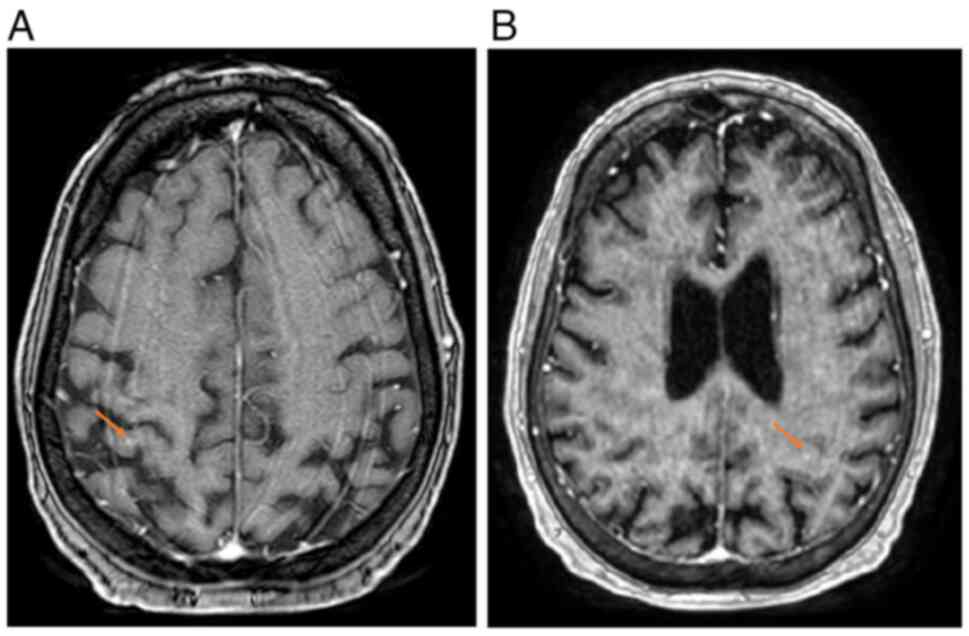

until stabilization was achieved. Over a span of 2 months, the

patient suffered from neurological symptoms, manifesting as a

decreased level of consciousness and seizures. Subsequent brain

magnetic resonance imaging findings confirmed the presence of small

bilateral hemispheric lesions suggestive of metastatic deposits

(Fig. 4A and B). Concurrently, the

urinary tract infections of the patient exhibited resistance to

treatment. A final CT scan performed before clinical deterioration

revealed no local recurrence of the right-sided breast cancer, with

a partial response of the right axillary lymph node, a mild

increase in right-sided pleural effusion and a new large lytic bone

metastasis in the right iliac bone, with a non-displaced fracture

of the right pubic bone (Fig.

S8).

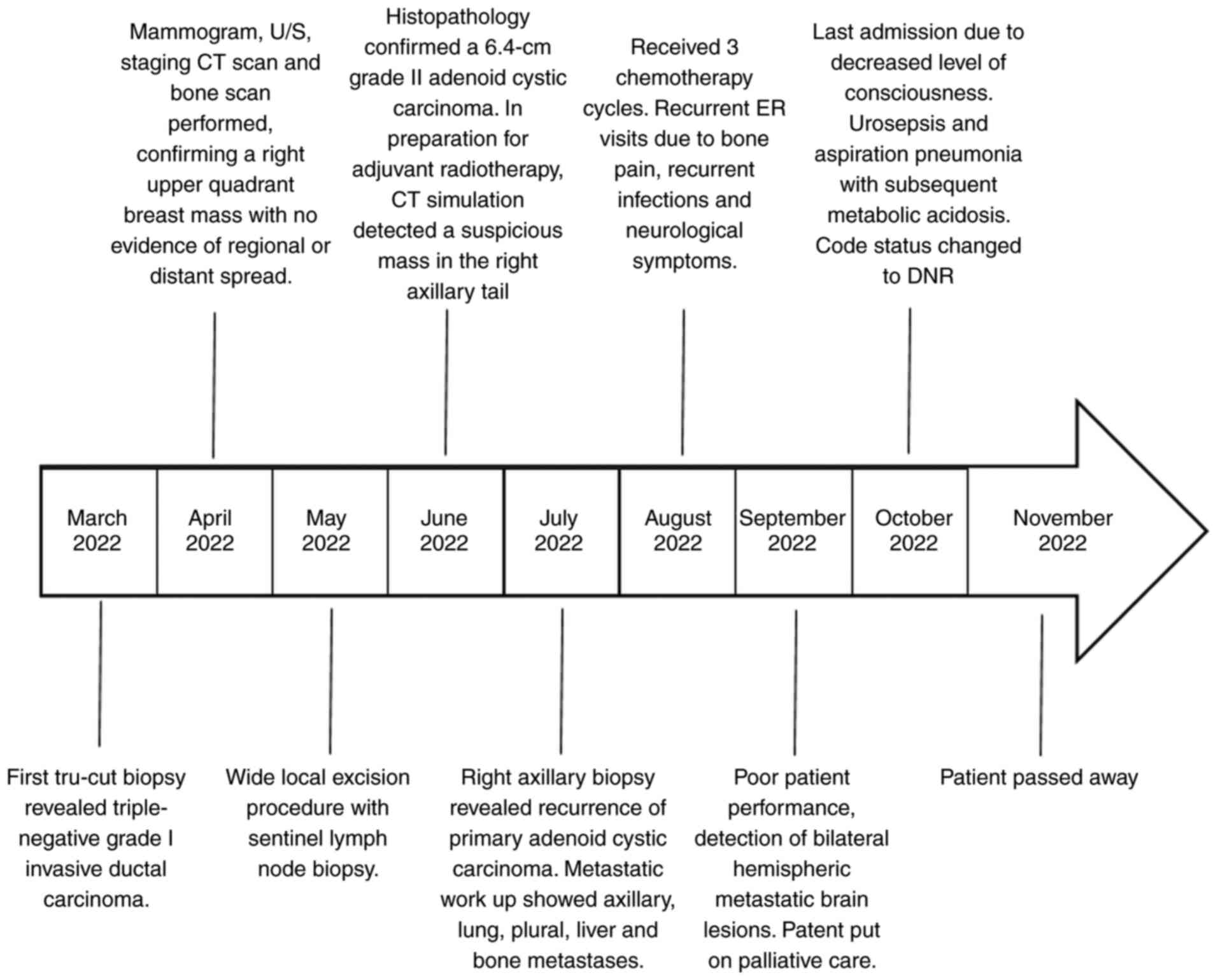

At 7 months after the initial diagnosis, the patient

presented with a decreased level of consciousness. Clinical and

diagnostic evaluation detected urosepsis, concomitant aspiration

pneumonia and an acute-on-chronic kidney disease, with resultant

metabolic acidosis and poor Glasgow Coma Scale (6/15) (15). After discussion with the family, the

code status of the patient was changed to ‘do not resuscitate’ and

the patient was administered comfort measures until they passed

away 2 weeks later. The patient timeline of events is summarized in

Fig. 5.

Discussion

It is considered that AdCC was first described as a

‘tumeur heteradenique’ by Robin and Laboulbene in 1853 (16). Subsequently, it was referred to as a

‘cylindroma’ due to the presence of cylindrical-shaped cells in a

hyaline stroma (17). In 1953, the

term AdCC was introduced by Foote and Frazell (18) to describe a distinct category

primarily arising in the minor salivary, parotid and submandibular

glands, comprising 3–5% of head and neck malignancies (18,19).

AdCC also manifests as a rare subtype of primary breast carcinomas,

which was first described by Geschickter and Copeland (20) in 1945. AdCC accounts for <0.1% of

all breast cancer cases and 0.058% of total AdCC cases (7,9,21).

In a comprehensive cohort covering a 30-year

interval, the age-adjusted incidence ratio was calculated to be

0.92 per 1 million person-years, predominantly affecting the female

population, with a median age of onset falling between 50 and 60

years (11). Jang et al

(22) reported lower overall

survival (OS) rates in head and neck AdCC cases in age groups

>70 years old compared with those in groups <45 years old.

Zhang et al (23) supported

the aforementioned association; however, conflicting opinions

exist, with studies indicating lower OS in both age extremes

(<45 and >60 years) (24,25).

Notably, the age of the patient in the present study at symptom

onset exceeded the average age documented in the aforementioned

reports (24,25).

The clinical presentation and imaging findings of

breast AdCC are non-specific, typically manifesting as a

well-circumscribed, palpable mass, with no predilection for the

left or right breast or specific quadrants (23). However, some studies have

demonstrated a preference for the submastoid and upper outer

quadrant region, while others have shown a 50% tendency for the

subareolar region (10,23,26,27).

Pain and tenderness upon palpation may be present, possibly due to

the perineural invasion of the lesion (28). In the present case, the latter

findings were not observed, as the histological assessment of the

resected mass revealed no evidence of perineural invasion. The

tumor usually ranges in size between 2 and 3 cm and exhibits a slow

growth pattern (29,30).

Imaging modalities are able to detect AdCC; however,

the efficacy of mammography in accurately distinguishing AdCC from

its benign differentials remains uncertain. Typically, AdCC

manifests as irregular masses with spiculated margins (7,31,32).

In the present case, mammography revealed an irregular spiculated

hyperdense mass, with a prior biopsy-proven confirmation of

malignancy. Breast U/S and staging CT scans supported these

findings; however, it is important to note the role that the

post-resection CT simulation scan played in the early detection of

recurrence. In the present case, CT simulation imaging was able to

detect a suspected atypical lesion in the axillary tail at 1.5

months post-resection, aligning with existing studies of the

paramount diagnostic value of the imaging technique in detecting

new lesions and planning therapeutic strategies (33–35).

Histologically, AdCC diagnosis relies on identifying

a dual cell population of myoepithelial and epithelial cells,

presenting true duct-like structures with microvilli-projecting

epithelial cells and pseudo-cyst structures lined by myoepithelial

cells (11,36,37).

AdCC is categorized according to the predominant growth structure

into one or a combination of three groups, namely, cribriform,

tubular and solid, with histological subdivisions holding

prognostic value (38). Ro et

al (39) proposed a

classification for breast AdCC. Grade I is characterized by the

absence of solid components, grade II exhibits <30% solid

components and grade III exhibits >30% solid components. The

2019 World Health Organization classification of Tumors of the

Breast highlights that the classic form of AdCC with predominant

cribriform and tubular differentiation is more prognostically

favorable, and such cases are recommended to undergo conservative

treatment, in contrast to solid-basaloid AdCC and high-grade AdCC,

which exhibit elevated rates of both local and distant recurrence

(40,41). A comprehensive analysis by

Slodkowska et al (42)

involving 108 AdCC cases revealed a significantly higher incidence

of distant metastasis in basaloid AdCC compared with that in

classic AdCC (40 vs. 8%; P<0.0004). In a study by Marco et

al (43), high-grade

transformation of AdCC presented with skin and lung involvement in

one patient, and lung, colon and brain involvement in a second

patient, both of whom eventually died of disease. Examination of

previously published case reports with distant metastases (Table I) (9,24,27,39,44–59),

reveals a prevailing incidence of solid-basaloid AdCC and

high-grade AdCC.

| Table I.Literature review of cases of breast

adenoid cystic carcinoma with aggressive behavior. |

Table I.

Literature review of cases of breast

adenoid cystic carcinoma with aggressive behavior.

| First author/s,

year | Age, years | Sex | Size

(grade/stage) | Genetic

alternations | Site of

metastasis | Lymph node

involvement | Surgical

intervention | Adjuvant

therapies | Time until

recurrence from primary surgery | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Vasudevan et

al, 2023 | ~60 | Female | 4.5×4×4 cm, 3×2.5×2

cm (high grade cribriform-solid); Ki-67, 70–80% | NR | Lung | None | Mastectomy | R | 11 Y | NR | (44) |

| Ji et al,

2022 | 50 | Female | 1.5 cm

(solid-basaloid) | (+) MYB

rearrangement | Lung | None | Lumpectomy | C + R | 2.5 Y | Alive | (24) |

|

| 59 | Female | 4.0 cm

(solid-basaloid) | (−) MYB

rearrangement | Liver | None | Mastectomy | C | 1.5 Y | Alive |

|

| Collins et

al, 2020 | 49 | Female | (High grade,

>30% solid components) | NR | Skin (multiple

sites) | NR | Lumpectomy | NR | 1.3 Y post initial

diagnosis | NR | (45) |

| Sołek et al,

2020 | 52 | Female | Stage IIA (T2N0Mx)

(high grade solid-basaloid) | NR | Lung | None | Mastectomy | R | 1 M | Alive | (46) |

|

| 41 | Female | Stage IA (T1N0Mx)

(high grade solid-basaloid) | NR | Lung, liver,

brain | NR | Lumpectomy | C + R | 1 Y | Alive |

|

| Mhamdi et

al, 2017 | 65 | Female | 8.0 cm | (−) MYB

rearrangement | Lung, liver, brain,

kidney | None | Mastectomy | R | 4 Y | Alive | (47) |

| Miyai et al,

2014 | 83 | Female | 3.0 cm (grade I)

(stage IV) | NR | Lung | None | Lumpectomy | None | 7 Y | Alive | (9) |

| Kim et

al, | 33 | Female | (pT2N0M0) | NR | Lung | None | Quadrantectomy | C + R | 2.6 Y | Alive | (27) |

| 2014 | 58 | Female | (pT2N0M0) | NR | Lung, liver,

bone | None | Mastectomy | C | 6.25 Y | Alive |

|

| D'Alfonso et

al, 2014 | 25 | Female | 6.5 cm (grade II,

cribriform-solid) | (−) MYB

rearrangement | Lung, liver,

brain | NR | Mastectomy | None | 5 Y | Dead | (48) |

|

| 55 | Female | 2.0 cm (grade III,

solid-basaloid) | (−) MYB

rearrangement | Lung | None | Mastectomy | None | 4.58 Y post initial

diagnosis | Alive |

|

| Silva et al,

2011 | 37 | Female | 3 cm

(solid-basaloid) (T2N1Mx) | NR | Lung, liver, bone,

brain | Yes | Mastectomy | None | 2 Y | Dead | (49) |

| Vranić et

al, 2007 | 76 | Female | 1.8 cm (pT1cN0MxR0,

cribriform-solid) | (+) PIK-3CA and

PTEN mutations | Kidney | None | Mastectomy | None | 5 Y | NR | (50) |

| Millar et

al, 2004 | 53 | Male | 4.0 cm | NR | Bone, brain | Yes | Mastectomy | R | 10 Y | Dead | (51) |

| Herzberg et

al, 1991 | 57 | Female | 1.5 cm

(cribriform) | NR | Lung, kidney | None | Mastectomy | None | 6 Y | Alive | (52) |

| Ro et al,

1987 | 53 | Female | 2.5 cm (grade

II) | NR | Lung, thigh,

skull | None | Mastectomy | None | 9 Y | Dead | (39) |

|

| 68 | Female | 0.7 cm (grade

II) | NR | Lung | None | Mastectomy | R | 5 Y | Alive |

|

|

| 64 | Female | 6.0 cm (grade

III) | NR | Liver, brain | Yes | Mastectomy | None | 1 Y | Dead |

|

| Koller et

al, 1986 | 49 | Female | NR | NR | Lung, brain | None | Mastectomy | None | 1 Y local

recurrence; 8 Y distant metastasis | Alive | (53) |

| Peters and Wolff,

1983 | 73 | Female | 1.0 cm | NR | Lung, liver | None | Mastectomy | None | 10 Y | Alive | (54) |

| Lim et al,

1979 | 48 | Female | NR | NR | Lung | None | Mastectomy | None | 9 Y | NR | (55) |

| Verani and Van

der Bel-Kahn, 1973 | 63 | Female | 2.0 cm | NR | Lung,

vertebrae | Yes | Mastectomy | None | 14 Y | Dead | (56) |

|

| 78 | Male | 3.5×3×2 cm | NR | Lung, liver | None | Mastectomy | None | 6 M | Dead |

|

| Elsner, 1970 | 44 | Female | NR | NR | Lung | NR | Mastectomy | None | 7 Y | NR | (57) |

| Wilson and Spell,

1967 | 54 | Female | 2.8 cm | NR | Ribs | Yes | Mastectomy | None | 6 Y | NR | (76) |

| O'Kell, 1964 | 73 | Female | NR | NR | Lung, inferior vena

cava | NR | Mastectomy | None | 3 Y | Dead | (58) |

| Nayer, 1957 | 39 | Female | NR | NR | Lung | None | Mastectomy | None | 8 Y | Dead | (59) |

| Present study | 77 | Female | 6.4 cm (grade II)

(Nottingham 6/9) (pT3N0) | NR | Lung, liver, bone,

brain | Yes | Lumpectomy | R planned | 1.5 M | Dead | - |

Following the American Joint Committee on Cancer

guidelines (60), the utilization

of the Nottingham score was endorsed in the present study, where

scores exceeding 5 represent a higher grade and poorer outcome. The

present case had a total score of 6/9 (tubular differentiation,

2/3; nuclear pleomorphism, 2/3; and mitotic activity, 2/3)

(13). Despite the favorable score,

the observed tumor size was 6.4 cm, surpassing the median size

reported in prior studies (7,61).

This notable size difference may have contributed as a factor to

the subsequent aggressive behavior of the tumor in the patient,

despite absence of initial extension to adjacent structures or

lymph nodes (30). Factors

affecting prognosis in AdCC of the breast include a solid growth

pattern (>30%), basaloid morphology, lymphovascular invasion,

perineural invasion, necrosis, lymph node involvement, positive

margins and high Nottingham grade (12,40).

In the present case, a few factors may have contributed to the

worse prognosis, including the presence of significant solid and

basaloid components, the large tumor size and the higher tumor

grade, along with the increased mitotic activity and Ki-67 value,

which eventually resulted in distant generalized metastasis.

IHC, genomic investigations and the distinct

polarity of cellular structures are pivotal in achieving an

accurate diagnosis of AdCC. This arises from the inherent challenge

in distinguishing the solid-basaloid variant of AdCC from the more

aggressive triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) with basal-like

features, where both entities share characteristics in terms of

negativity for ER, PR and HER2/neu receptors. Additionally, they

exhibit reactivity for basal high molecular weight CKs, including

CK5/6, CK14, CK17 and luminal progenitors CK8/18 (62). Specifically, the luminal cells in

AdCC exhibit positivity for CK7, CK8/18, epithelial membrane

antigen and c-KIT, while myoepithelial cells exhibit positivity for

CK5, CK5/6, CK14, CK17, p63, actin, calponin, S100, vimentin and

epidermal growth factor receptor (63,64). A

key difference between TNBC and AdCC lies in the loss of

myoepithelium, and the loss of reactivity to p63 and calponin in

TNBC (24). In the present case,

IHC analysis of the recurrent lesion revealed triple-negative

expression for ER, PR and HER2/neu, limited positivity for p63 and

focal positivity for CK8/18. Notably, the Ki-67 value was markedly

elevated at 50%, which is uncharacteristic of the proliferative

activity associated with low-grade AdCC. Wetterskog et al

(65) reported a low Ki-67 index in

69% of AdCC cases, with a moderate index in the remaining cases

(66). This observation is

particularly important, as Ki-67 has been established as a valuable

marker of cellular proliferation, with higher levels being

associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and poor clinical

outcomes (67). High Ki-67

expression was associated with advanced histological grade and

recurrence in a retrospective study (68). Another study found that Ki-67

immunoreactivity increased proportionally with tumor grade,

averaging 27.12% in grade I, 34.43% in grade II and 38.45% in grade

III tumors (69).

The majority of cases of AdCC of the breast harbor

the transcriptional activator Myb:: nuclear factor IB (MYB::NFIB)

fusion gene [t(6;9)(q22-23;p23-24)], which is considered a

molecular hallmark of the diagnosis (48). The gene fusion can be detected by

fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or PCR (65,70).

In the absence of molecular testing, diffuse and strong MYB protein

expression detected by IHC is often used as a surrogate,

particularly in conventional AdCC. However, this surrogate is less

reliable for solid variants. Massé et al (71) reported that only 19% of solid-type

AdCCs exhibited MYB gene rearrangements based on FISH, suggesting

that this variant may be a distinct molecular entity enriched for

CREB-binding protein and neurogenic locus notch homolog protein

pathway mutations. We acknowledge the absence of MYB::NFIB testing

in the present case due to institutional limitations. This

represents a diagnostic limitation, as molecular confirmation would

have further strengthened the diagnosis in the present study,

particularly given the aggressive clinical course and high-grade

histological features.

Breast AdCC is renowned for its indolent nature and

favorable prognosis, distinguishing itself from its salivary gland

counterpart and other forms of TNBC (54). Axillary lymph node involvement is

rare, with Arpino et al (72) documenting lymph node metastasis in

only 1 of 23 cases studied. Distant metastasis is also uncommon,

following a hematogenous route and silent progression, and often

emerging several years after the initial presentation. The lung is

the most frequently affected organ, along with the occasional

involvement of the liver, bones and brain (73). Consequently, various reports have

argued against routine axillary lymph node dissection during

surgery and underscored the importance of prolonged follow-up

during remission (47,74,75).

In the present study, to the best of our knowledge, all the

previously reported cases of breast AdCC with confirmed recurrence

and distant metastasis have been compiled and presented in Table I (9,24,27,39,44–59).

The present case, alongside the case reported by Sołek et al

(46) represent, to the best of our

knowledge, the only two reported instances in the literature where

the interval between resection and the detection of the first

metastatic lesion was <3 months. While Sołek et al

(46) exclusively reported lung

involvement, the present case reported a broad spectrum of

metastases, including those of the lungs, pleura, liver, bones and

brain, culminating in a fatal outcome. Additionally, the discussed

case is among the limited reports revealing axillary lymph node

involvement, joining the case reports by Silva et al

(49) Verani and Van der Bel-Kahn

(56), Wilson and Spell (76), and Ro et al (39) in mentioning this uncommon

manifestation.

Management strategies for AdCC of the breast vary

across different clinical recommendations, particularly concerning

the adoption of an aggressive surgical approach despite the

recognized indolent nature of the tumor (77). Ro et al (39) proposed a treatment strategy

involving local excision for grade I tumors, simple mastectomy for

grade II tumors and mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection

for grade III tumors. Hodgson et al (78) suggested a more comprehensive

approach due to the reported instances of positive margins

post-excision, irrespective of the year of surgery or local

practice patterns, but perhaps due to the silent and microscopic

infiltration of the tumor into breast tissue. This mechanism may

have contributed to the outcome of the present patient, as the

treatment plan involved a wide local excision surgery coupled with

radiotherapy sessions, which were halted by the discovery of local

and distant recurrence of the disease, and then the commencing of

chemotherapy. There is a consensus on the efficacy of lumpectomy or

mastectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy in achieving remission and

preventing recurrence, with no significant impact of adjuvant

chemotherapy on OS (11,51,79,80).

This was supported by a retrospective study of 488 AdCC cases

conducted by Gomez-Seoane et al (81), which demonstrated an increased OS

rate in the post-resection adjuvant radiation therapy group

compared with that in those subjected to surgery alone.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines

consider AdCC a favorable histology and only recommend adjuvant

chemotherapy for pathological node positive disease (82). Furthermore, limited responses to

neoadjuvant chemotherapy have been documented in solid-basaloid

variants, with a complete pathological response remaining rare

(83). However, evolving evidence

has raised the need to reconsider whether adjuvant chemotherapy

should be added for high-risk subtypes, particularly solid-basaloid

and high-grade AdCC. Such variants have shown to be associated with

more aggressive clinical behavior, higher rates of nodal

involvement and early distant metastasis (42).

There are several potential limitations to the

present study. First, its retrospective design may introduce bias

and limit the ability to establish causal relationships. Second,

the advanced age of the patient and their comorbidities presented

significant challenges in administering various therapeutic

options. Additionally, despite early surgical intervention, the

aggressive nature of the solid-basaloid subtype of AdCC resulted in

rapid metastasis and disease progression, underscoring the

limitations of current treatment strategies in managing high-risk

cases. In addition, the suitability of this tumor to represent a

high-grade metaplastic, triple-negative, matrix-producing carcinoma

is high. The case was subject to intradepartmental discussion and a

consensus diagnosis was made based on the available histology,

hormonal studies, immunohistochemical stains and clinical

presentation at the time of first diagnosis. The gold standard for

diagnosis is detecting MYB::NFIB gene fusion by molecular methods

or detecting upregulation of MYB expression by IHC; however,

neither tests were available at King Hussein Cancer Center. In

summary, despite its indolent nature, certain subtypes of AdCC of

the breast carry aggressive behavior manifested by short-term

locoregional and systemic spread. The present report highlights the

importance of a further understanding of AdCC of the breast, and

the challenges that can arise in achieving control of this

pathology.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL, FA and HAR designed the overall concept and

outline of the manuscript. HL and FA confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. HL, FA, LW, RA, WA, AA, OJ, IM and HAR have

contributed to methodology, data collection and the review of the

literature. HL, FA, LW, RA, WA, AA, OJ, IM and HAR contributed to

writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The requirement for consent for participation was

waived by the Institutional Review Board at King Hussein Cancer

Center (Amman, Jordan) due to the study nature and no added risk to

the participant.

Patient consent for publication

Consent for publication could not be obtained as the

patient passed away prior to the time of writing this report.

However, the Institutional Review Board at King Hussein Cancer

Center (Amman, Jordan) issued a determination waiving the

requirement for consent, as this case qualifies as non-human

subject research. All patient data have been fully anonymized in

compliance with ethical standards and publication guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jordan Ministry of Health,

Non-Communicable Diseases Directorate, Jordan Cancer Registry,

Cancer Incidence in Jordan, . 2019.

|

|

4

|

Masood S: Breast cancer subtypes:

Morphologic and biologic characterization. Womens Health (Lond).

12:1032016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bradley PJ: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the head and neck: A review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

12:127–132. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rahouma M, Khairallah S, Baudo M, Al-Thani

S, Dabsha A, Shenouda D, Mohamed A, Dimagli A, El Sherbiny M, Kamal

M, et al: Epidemiological study of adenoid cystic carcinoma and its

outcomes: insights from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end

results (SEER) database. Cancers (Basel). 16:33832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Glazebrook KN, Reynolds C, Smith RL,

Gimenez EI and Boughey JC: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 194:1391–1396. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Seethala RR: An update on grading of

salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 3:69–77. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Miyai K, Schwartz MR, Divatia MK, Anton

RC, Park YW, Ayala AG and Ro JY: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

breast: Recent advances. World J Clin Cases. 2:732–741. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kulkarni N, Pezzi CM, Greif JM, Suzanne

Klimberg V, Bailey L, Korourian S and Zuraek M: Rare breast cancer:

933 Adenoid cystic carcinomas from the national cancer data base.

Ann Surg Oncol. 20:2236–2241. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ghabach B, Anderson WF, Curtis RE, Huycke

MM, Lavigne JA and Dores GM: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast

in the United States (1977 to 2006): A population-based cohort

study. Breast Cancer Res. 12:R542010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Khoury T, Rosa M, Nayak A, Karabakhtsian

R, Fadare O, Li Z, Turner B, Fang Y, Kumarapeli A, Li X, et al:

Clinicopathologic predictors of clinical outcomes in mammary

adenoid cystic carcinoma: A multi-institutional study. Mod Pathol.

36:1000062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Lee AHS, Elston CW,

Grainge MJ, Hodi Z, Blamey RW and Ellis IO: Prognostic significance

of nottingham histologic grade in invasive breast carcinoma. J Clin

Oncol. 26:3153–3158. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Giuliano AE, Edge SB and Hortobagyi GN:

Eighth edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: Breast cancer.

Ann Surg Oncol. 25:1783–1785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Teasdale G and Jennett B: Assessment of

coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet.

2:81–84. 1974. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Otto RA: Tumours of the upper jaw. By

Donald Harrison and Valerie J. Lund, Churchill Livingstone, New

York, 1993, 351 pp, $150.00. Head Neck,. 17:275. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Andreasen S: Molecular features of adenoid

cystic carcinoma with an emphasis on microRNA expression. APMIS.

126 (Suppl 140):S7–S57. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Foote FW Jr and Frazell EL: Tumors of the

major salivary glands. Cancer. 6:1065–1133. 1953. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ellington CL, Goodman M, Kono SA, Grist W,

Wadsworth T, Chen AY, Owonikoko T, Ramalingam S, Shin DM, Khuri FR,

et al: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Incidence and

survival trends based on 1973–2007 surveillance, epidemiology, and

end results data. Cancer. 118:4444–4451. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Geschickter CF and Copeland MM: Diseases

of the breast: Diagnosis, pathology, treatment. J B Lippincott;

Philadelphia: 1945, PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rosen PP: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

breast. A morphologically heterogeneous neoplasm. Pathol Annu.

24:237–254. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jang S, Patel PN, Kimple RJ and McCulloch

TM: Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors of adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the head and neck. Anticancer Res. 37:3045–3052.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang W, Fang Y, Zhang Z and Wang J:

Management of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: A

single-institution study. Front Oncol. 11:6210122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ji J, Zhang F, Duan F, Yang H, Hou J, Liu

Y, Dai J, Liao Q, Chen X and Liu Q: Distinct clinicopathological

and genomic features in solid and basaloid adenoid cystic carcinoma

of the breast. Sci Rep. 12:85042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Choi Y, Kim SB, Yoon DH, Kim JY, Lee SW

and Cho KJ: Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of

adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope.

123:1430–1438. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Thomas DN, Asarian A and Xiao P: Adenoid

cystic carcinoma of the breast. J Surg Case Rep. 2019:rjy3552019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kim M, Lee DW, Im J, Suh KJ, Keam B, Moon

HG, Im SA, Han W, Park IA and Noh DY: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the breast: A case series of six patients and literature review.

Cancer Res Treat. 46:93–97. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

McClenathan JH and de la Roza G: Adenoid

cystic breast cancer. Am J Surg. 183:646–649. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Boujelbene N, Khabir A, Boujelbene N,

Jeanneret Sozzi W, Mirimanoff RO and Khanfir K: Clinical

review-breast adenoid cystic carcinoma. Breast. 21:124–127. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu Z, Wang M, Wang Y, Shen X and Li C:

Diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma in the breast: A case report

and literature review. Arch Med Sci. 18:279–283. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sheen-Chen SM, Eng HL, Chen WJ, Cheng YF

and Ko SF: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: Truly uncommon

or easily overlooked? Anticancer Res. 25:455–458. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Santamaría G, Velasco M, Zanón G, Farrús

B, Molina R, Solé M and Fernández PL: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the breast: Mammographic appearance and pathologic correlation. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 171:1679–1683. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Murakami R, Kumita SI, Yoshida T, Ishihara

K, Kiriyama T, Hakozaki K, Yanagihara K, Iida S and Tsuchiya S:

FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis of recurrent breast cancer. Acta

Radiol. 53:12–16. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yu Y, Schöder H, Zakeri K, Chen L, Kang

JJ, McBride SM, Tsai CJ, Gelblum DY, Boyle JO, Cracchiolo JR, et

al: Post-operative PET/CT improves the detection of early

recurrence of squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. Oral

Oncol. 141:1064002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kim B, Kim YC, Noh OK, Heo J, Lee HW, Kim

JH, Lee JH, Kim JK, Cho O, Oh YT and Chun M: Diagnostic evaluation

of simulation CT images for adjuvant radiotherapy in pancreatic

adenocarcinoma. Br J Radiol. 90:201702252017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Koss LG, Brannan CD and Ashikari R:

Histologic and ultrastructural features of adenoid cystic carcinoma

of the breast. Cancer. 26:1271–1279. 1970. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Anthony PP and James PD: Adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the breast: Prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and

histogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 28:647–655. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

da Cruz Perez DE, de Abreu Alves F, Nobuko

Nishimoto I, de Almeida OP and Kowalski LP: Prognostic factors in

head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 42:139–146.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ro JY, Silva EG and Stephen Gallager H:

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 18:1276–1281.

1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shin SJ and Rosen PP: Solid variant of

mammary adenoid cystic carcinoma with basaloid features: A study of

nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 26:413–420. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tan PH, Ellis I, Allison K, Brogi E, Fox

SB, Lakhani S, Lazar AJ, Morris EA, Sahin A, Salgado R, et al: The

2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the

breast. Histopathology. 77:181–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Slodkowska E, Xu B, Kos Z, Bane A, Barnard

M, Zubovits J, Iyengar P, Faragalla H, Turbin D, Williams P, et al:

Predictors of outcome in mammary adenoid cystic carcinoma: A

multi-institutional study. Am J Surg Pathol. 44:214–223. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Marco V, Garcia F, Rubio IT, Soler T,

Ferrazza L, Roig I, Mendez I, Andreu X, Mínguez CG and Tresserra F:

Adenoid cystic carcinoma and basaloid carcinoma of the breast: A

clinicopathological study. Rev Esp Patol. 54:242–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Vasudevan G, John AM, D K V and

Vallonthaiel AG: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast with late

recurrence and high-grade transformation. BMJ Case Rep.

16:e2523362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Collins K, Prieto VG and Aung PP: Unusual

presentations of primary and metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma

involving the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 42:967–971. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sołek JM, Braun M, Kalwas M,

Jesionek-Kupnicka D and Romańska HM: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the breast-an uncommon malignancy with unpredictable clinical

behaviour. A case series of three patients. Contemp Oncol (Pozn).

24:263–265. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Mhamdi HA, Kourie HR, Jungels C, Aftimos

P, Belbaraka R and Piccart-Gebhart M: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the breast-an aggressive presentation with pulmonary, kidney, and

brain metastases: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 11:3032017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

D'Alfonso TM, Mosquera JM, Macdonald TY,

Padilla J, Liu YF, Rubin MA and Shin SJ: MYB-NFIB gene fusion in

adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast with special focus paid to

the solid variant with basaloid features. Hum Pathol. 45:2270–2280.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Silva I, Tome V and Oliveira J: Adenoid

cystic carcinoma of the breast with cerebral metastisation: A

clinical novelty. BMJ Case Rep. 2011:bcr08201146922011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Vranić S, Bilalović N, Lee LMJ, Krušlin B,

Lilleberg SL and Gatalica Z: PIK3CA and PTEN mutations in adenoid

cystic carcinoma of the breast metastatic to kidney. Hum Pathol.

38:1425–1431. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Millar BAM, Kerba M, Youngson B, Lockwood

GA and Liu FF: The potential role of breast conservation surgery

and adjuvant breast radiation for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 87:225–232. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Herzberg AJ, Bossen EH and Walther PJ:

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the kidney. A

clinically symptomatic lesion requiring surgical management.

Cancer. 68:1015–1020. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Koller M, Ram Z, Findler G and Lipshitz M:

Brain metastasis: A rare manifestation of adenoid cystic carcinoma

of the breast. Surg Neurol. 26:470–472. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Peters GN and Wolff M: Adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the breast report of 11 new cases: Review of the

literature and discussion of biological behavior. Cancer.

52:680–686. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lim SK, Kovi JK and Warner OG: Adenoid

cystic carcinoma of breast with metastasis: A case report and

review of the literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 71:329–330.

1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Verani RR and Van der Bel-Kahn J: Mammary

adenoid cystic carcinoma with unusual features. Am J Clin Pathol.

59:653–658. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Elsner B: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

breast. Review of the literature and clinico-pathologic study of

seven patients. Pathol Eur. 5:357–364. 1970.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

O'Kell RT: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

breast. Mo Med. 61:855–858. 1964.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Nayer HR: Case report section; cylindroma

of the breast with pulmonary metastases. Dis Chest. 31:324–327.

1957. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhu H and Doğan BE: American joint

committee on cancer's staging system for breast cancer, eighth

edition: Summary for clinicians. Eur J Breast Health. 17:234–238.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Canyilmaz E, Uslu GH, Memiş Y, Bahat Z,

Yildiz K and Yoney A: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: A

case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 7:1599–1601. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Vranic S, Bender R, Palazzo J and Gatalica

Z: A review of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast with emphasis

on its molecular and genetic characteristics. Hum Pathol.

44:301–309. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Badve S, Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ, Baehner FL,

Decker T, Eusebi V, Fox SB, Ichihara S, Jacquemier J, Lakhani SR,

et al: Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: A critical

review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and

oncologists. Mod Pathol. 24:157–167. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K, Cheang M,

Karaca G, Hu Z, Hernandez-Boussard T, Livasy C, Cowan D, Dressler

L, et al: Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the

basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res.

10:5367–5374. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wetterskog D, Lopez-Garcia MA, Lambros MB,

A'Hern R, Geyer FC, Milanezi F, Cabral MC, Natrajan R, Gauthier A,

Shiu KK, et al: Adenoid cystic carcinomas constitute a genomically

distinct subgroup of triple-negative and basal-like breast cancers.

J Pathol. 226:84–96. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Kilickap S, Kaya Y, Yucel B, Tuncer E,

Babacan NA and Elagoz S: Higher Ki67 expression is associates with

unfavorable prognostic factors and shorter survival in breast

cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 15:1381–1385. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Davey MG, Hynes SO, Kerin MJ, Miller N and

Lowery AJ: Ki-67 as a prognostic biomarker in invasive breast

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13:44552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Al Zubidi M, Abdulhussain MM and Mohsin

AS: Assessment of the relationship between Ki-67 expression and

different clinicopathological factors of adenoid cystic carcinoma:

A retrospective immunohistochemical study. Int J Biomed.

15:141–145. 2025.

|

|

69

|

Bussari S, Jeergal PA, Sarode M, Namazi

NA, Kulkarni PG, Deshmukh A and Kulkarni D: Evaluation of

proliferative marker Ki-67 in adenoid cystic carcinoma: A

retrospective study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 20:211–215. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Persson M, Andrén Y, Mark J, Horlings HM,

Persson F and Stenman G: Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB

transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and

neck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:18740–18744. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Massé J, Truntzer C, Boidot R, Khalifa E,

Pérot G, Velasco V, Mayeur L, Billerey-Larmonier C, Blanchard L,

Charitansky H, et al: Solid-type adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

breast, a distinct molecular entity enriched in NOTCH and CREBBP

mutations. Mod Pathol. 33:1041–1055. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Arpino G, Clark GM, Mohsin S, Bardou VJ

and Elledge RM: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: Molecular

markers, treatment, and clinical outcome. Cancer. 94:2119–2127.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Marchiò C, Weigelt B and Reis-Filho JS:

Adenoid cystic carcinomas of the breast and salivary glands (or

‘The strange case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ of exocrine gland

carcinomas). J Clin Pathol. 63:220–228. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Cantù G: Adenoid cystic carcinoma. An

indolent but aggressive tumour. Part A: From aetiopathogenesis to

diagnosis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 41:206–214. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Page DL: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of

breast, a special histopathologic type with excellent prognosis.

Breast Cancer Res Treat. 93:189–190. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wilson WB and Spell JP: Adenoid cystic

carcinoma of breast: A case with recurrence and regional

metastasis. Ann Surg. 166:861–864. 1967. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Wang S, Ji X, Wei Y, Yu Z and Li N:

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: Review of the literature

and report of two cases. Oncol Lett. 4:701–704. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hodgson NC, Lytwyn A, Bacopulos S and

Elavathil L: Adenoid cystic breast carcinoma: High rates of margin

positivity after breast conserving surgery. Am J Clin Oncol.

33:28–31. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Khanfir K, Kallel A, Villette S, Belkacémi

Y, Vautravers C, Nguyen T, Miller R, Li YX, Taghian AG, Boersma L,

et al: Management of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: A rare

cancer network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 82:2118–2124.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Li L, Zhang D and Ma F: Adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the breast may be exempt from adjuvant chemotherapy. J

Clin Med. 11:44772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gomez-Seoane A, Davis A and Oyasiji T:

Treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: Is

postoperative radiation getting its due credit? Breast. 59:358–366.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J,

Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Bailey J,

Burstein HJ, et al: Breast Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical

Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:331–357. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Schulz-Costello K, Fan F, Schmolze D,

Arias-Stella JA III, Taylor L, Tseng J, Afkhami M, Rand JG, Jones

V, Farmah P and Han M: Solid basaloid adenoid cystic carcinoma of

the breast: A high-grade triple negative breast carcinoma which

rarely responds to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Hum Pathol.

157:1057602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|