Introduction

Globally, primary liver cancer ranks as the sixth

most prevalent cancer and was the third leading cause of

cancer-related deaths in 2022. Estimates indicate ~860,000 new

diagnoses and ~750,000 fatalities worldwide per year (1). In total, 75–85% of all primary liver

cancer cases are classified as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

(2). The principal treatment

modalities currently available for HCC include surgical

intervention, liver transplantation, chemotherapy and radiation

therapy (3). However, ~70% of

patients with HCC will experience a recurrence within 5 years

despite notable therapeutic advancements in recent decades, which

impacts their long-term survival outcomes and quality of life

(4,5). For clinicians, recurrence-free

survival (RFS) time serves as a critical parameter when formulating

individualized therapeutic strategies for patients with HCC

(6). Consequently, developing a

robust predictive model for the probability of HCC recurrence

represents a crucial clinical need.

Advances in large-scale sequencing technology have

enabled the development of multiple prognostic models utilizing

bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to predict HCC RFS. Gu et al

(7) designed a six-long non-coding

RNA signature for HCC RFS estimation and Wang et al

(8) constructed a seven-gene model.

However, despite the large amount of clinical information in the

bulk dataset, limitations of this sequencing technology result in

expression data that is the average of the expression in the bulk

tissue rather than the expression at the cellular level. This

introduces biological noise that may degrade model performance.

Recently, single-cell (sc)RNA-seq has been increasingly applied in

the study of HCC. Compared with bulk approaches, scRNA-seq

distinguishes individual cell populations and captures their

transcriptional activity at a cellular resolution, providing

notably more information to researchers (9–11).

Researchers increasingly favor combined analytical

frameworks incorporating both single-cell and bulk transcriptomic

data, as they can take advantage of the respective strengths of

both sequencing technologies. Zhou et al (12) identified prognostic ferroptosis

biomarkers that could guide individualized therapeutic strategies

for HCC by integrative analysis of transcriptomic data at different

resolutions. Yu et al (13)

characterized carcinoma-associated fibroblasts in HCC and

established a clinically relevant risk assessment model.

Furthermore, Wang et al (14) reported cellular heterogeneity and

immune infiltration in HCC and uncovered how they contribute to the

immunosuppressive microenvironment.

The present study combined single-cell and bulk

transcriptomic datasets and implemented integrative analysis to

establish an innovative predictive model for HCC recurrence

outcomes.

Materials and methods

Acquisition and cleaning of datasets

from patients with HCC

The present study incorporated one scRNA-seq dataset

and two bulk transcriptomic profiles from human HCC specimens. From

the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), the GSE242889

dataset was retrieved, which included single-cell transcriptomes

from five patients with HCC with corresponding peritumoral controls

(15). Among the five patients,

three were men and two were women, with a median age of 55 years

(range, 42–60 years). Bulk transcriptomic profiles with

corresponding clinical data were acquired from two independent

sources: The Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma

(TCGA-LIHC) dataset (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and the GEO dataset,

GSE76427 (16). For analytical

purposes, the TCGA-LIHC cohort served as the training cohort,

whereas the GSE76427 cohort was used for subsequent validation.

Subsequently, data cleanup was performed. In the TCGA-HCC dataset,

only the samples in which the histological type was HCC and the new

event type was locoregional recurrence, extrahepatic recurrence or

intrahepatic recurrence were included. In addition, for these two

bulk RNA-seq datasets, cases missing either RFS data (follow-up

time/status) or RNA-seq profiles data were excluded, even when

clinical annotations were available. Finally, a total of 342

patients with HCC and 50 normal controls from the TCGA-LIHC cohort

were included. The cohort comprised 230 men and 112 women, with a

median age of 61 years (range, 16–90 years). Additionally, 108

patients with HCC from the GSE76427 cohort were analyzed,

consisting of 86 men and 22 women, with a median age of 64 years

(range, 14–93 years).

Analysis of single-cell transcriptomic

profiles

The single-cell transcriptome dataset, GSE242889,

was merged using the Harmony algorithm (17). The samples were then analyzed as

described in our previous study (18), with modifications. First, quality

control measures excluded cells demonstrating either insufficient

sequencing depth (<200 detected genes) or potential multiplets

(>4,000 genes), along with those showing elevated mitochondrial

transcript proportions (≥50%). Second, cellular clustering was

performed using the FindClusters algorithm in Seurat (resolution

parameter, 0.8) (19), which

incorporates the first 17 principal components (PCs) as inputs.

Identifying the differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) associated with RFS

After the cells in the GSE242889 dataset were

classified and annotated, hepatocyte data were extracted for

subsequent analysis. The FindMarkers algorithm in Seurat was

employed to identify DEGs in hepatocytes derived from different

origin samples (19). The

statistical thresholds for DEGs were as follows:

|log2fold-change (FC)|>0.5 and adjusted P<0.05. In

the TCGA-LIHC dataset, differential expression analysis comparing

tumor and normal samples was performed using the ‘limma’ R package

(version 3.44.3) (20), and genes

with |log2 FC|>1 and adjusted P<0.05 were regarded

as DEGs. Subsequently, the associations between the gene expression

profiles and HCC recurrence outcomes were assessed using the

‘survfit’ function in the ‘survival’ package (https://github.com/therneau/survival;

version 3.2.7). The log-rank test result was interpreted with

P<0.05 indicating statistical significance. The overlapping

genes of these results were defined as the DEGs associated with

RFS.

Construction of the prognostic

signature

Survival-related DEGs were utilized as candidate

biomarkers to construct a prognostic signature. Least absolute

shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox penalized regression

analysis was performed using the R package ‘glmnet’ (version 4.1)

(21), and genes demonstrating

non-zero coefficients were incorporated into the final risk score

calculation. The risk score for each patient with HCC was

calculated as follows: Risk score=Σ (βi × Expi), where βi

represents the non-zero coefficients from LASSO Cox regression and

Expi denotes the expression levels of selected genes. Subsequently,

patients were dichotomized into high- and low-risk groups based on

median risk score stratification, followed by Kaplan-Meier survival

analysis.

Functional enrichment and immune

infiltration analysis

To identify the underlying mechanisms that affect

HCC, the DEGs between the high- and low-risk subgroups were

obtained. Functional enrichment analysis was then performed using

the ‘clusterProfiler’ package (version 4.7.1) to identify

significantly enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) terms among these DEGs

(22). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(GSEA) was performed for the genes in the prognostic signature to

further elucidate their biological functions. Additionally, the

relative abundances of 22 immune cell subtypes within HCC samples

were quantified using the CIBERSORT algorithm (23), and the immune-related score was

calculated using the ‘estimate’ R package (version 1.0.13)

(24).

Analysis of prognostic factors for

patients with HCC

To isolate independent recurrence predictors,

univariate Cox regression was first applied, followed by

multivariate analysis for 155 patients with HCC with complete

clinical variables. These variables included age, sex, body mass

index, tumor (T) stage, lymph node (N) stage, metastasis (M) stage,

grade, pathological stage, α-fetoprotein level, Child-Pugh score

and the risk score, which were classified using the appropriate

guidelines (25–27).

Validation of the prognostic

signature

Following prognostic signature development, external

validation was performed using the independent GSE76427 cohort. The

prognostic ability of the signature was first assessed using

time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

evaluation at 6-, 12- and 24-month intervals. Patients were

subsequently dichotomized into high- and low-risk subgroups using

the median risk score as the cutoff threshold, followed by

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

(Nanchang, China; approval no. 2024–078). Tissue samples were

collected at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

(Nanchang, China) from February 2024 to June 2024. Patients that

were diagnosed with HCC through pathological examination were

included in the present study, while any patients with coexisting

tumors were excluded from the study. A total of five HCC tissue

samples and five adjacent tissue samples were obtained following

documented informed consent from all study participants. Among the

patients, there were four men and one woman, with a median age of

51 years (range, 38–65 years).

RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed from the

HCC and normal tissues. For qPCR, the primers used are presented in

Table I. As the immunoglobulin λ

constant 2 (IGLC2) cDNA sequence was not available on the

National Center for Biotechnology Information website, it was

retrieved and aligned from Ensembl (http://ensemblgenomes.org/). The RT process proceeded

with an initial primer annealing step at 25°C for 5 min, followed

by the main cDNA synthesis reaction at 42°C for 30 min, which was

completed by a brief 5-sec heat inactivation step at 85°C. The qPCR

thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 30 sec. This was followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at

95°C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec.

Finally, a melting curve analysis was conducted by heating the

samples from 65 to 95°C. To ensure reliability, each experimental

procedure was performed in triplicate, and the study was

independently performed three times. Gene expression levels were

quantified using RT-qPCR with a PrimeScript™ RT Master

Mix (cat. no. RR036A; Takara Bio, Inc.) on an ABI 7500 Real-time

PCR system detection instrument (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), with relative expression determined using the

2−ΔΔCq method (28).

| Table I.Primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

|

| Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| GAPDH |

TCGTGGAAGGACTCATGACC |

TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA |

| CDKN2A |

GGGTTTTCGTGGTTCACATCC |

CTAGACGCTGGCTCCTCAGTA |

| CFHR3 |

TGCATCCGTGTCAATTCTTCA |

CTCGACTCTTGACTGTGGCA |

| CYP2C9 |

GCCTGAAACCCATAGTGGTG |

GGGGCTGCTCAAAATCTTGATG |

| HMGB2 |

CTCCAATACCCTCGGGTGG |

GAAGAAGGCGTACGAGGACA |

| IGLC2 |

CCCCCACCACGGGAGACTA |

AGGGTTTATTGAGTGCAGGGAG |

| JPT1 |

ATAGCTCCCGAGTTTTGCGG |

GCCACCACTAGACTTGGCAC |

Statistical analysis

R software (https://www.r-project.org/; version 4.2.3) was

utilized for statistical analysis. The data are presented as mean ±

SD from experiments conducted more than three times. Differences

between two groups were analyzed using a two-sided unpaired

Student's t-test. The Kaplan-Meier method was employed to plot

survival curves, and differences were assessed using the log-rank

test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine

independent factors. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

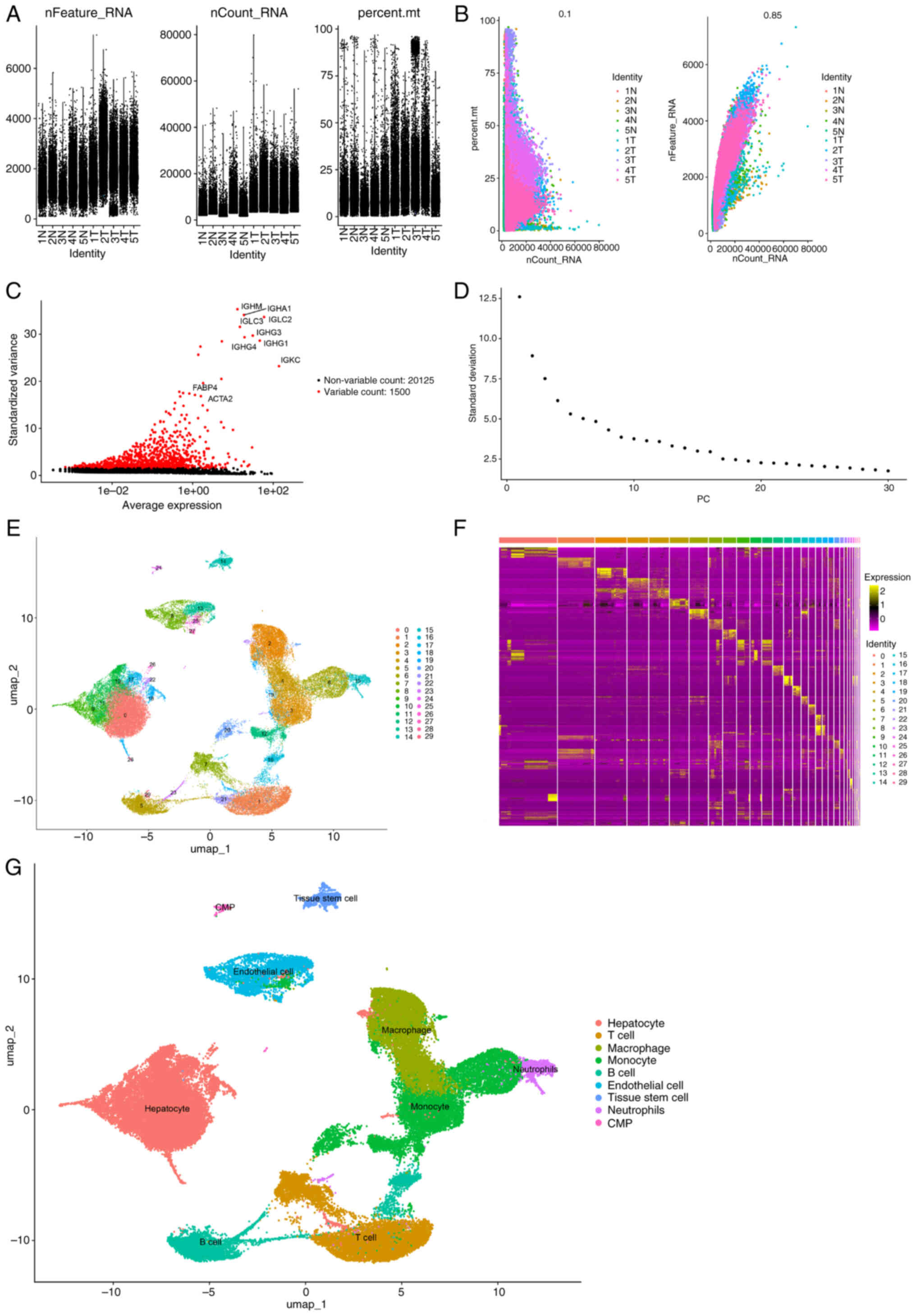

Cell types in the scRNA-seq

datasets

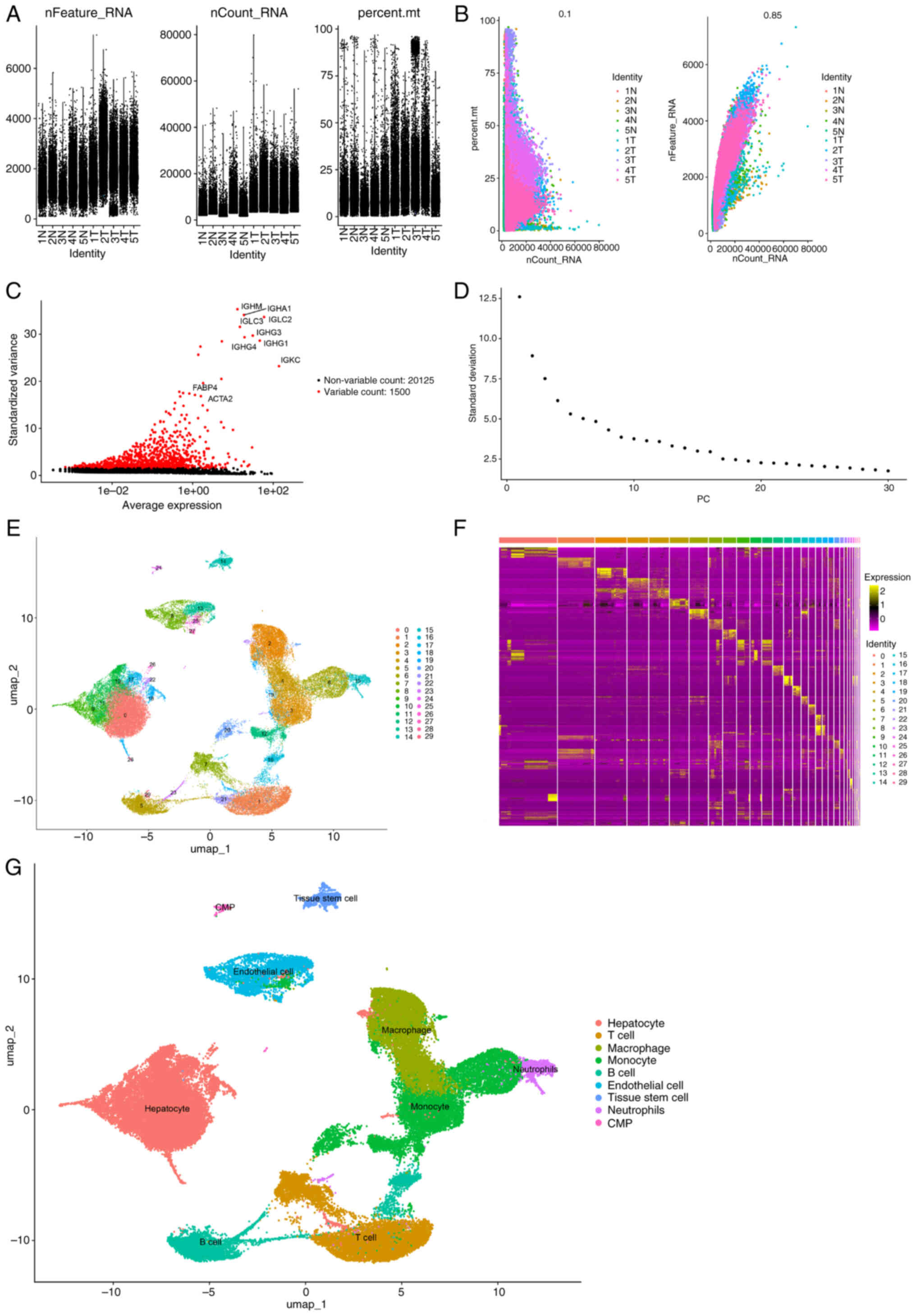

From the original 60,284 cells in the GSE242889

dataset, the quality control pipeline retained 57,219 cells that

passed all quality thresholds for downstream processing (Fig. 1A-D). The single-cell data were

subsequently segregated into 30 distinct clusters, from which

24,630 characteristic marker genes were detected (Fig. 1E; Table

SI). The 10 most significant markers per cluster were

visualized using a heatmap (Fig.

1F). The results revealed that clusters 0, 9, 10, 11, 17, 18,

22, 26 and 28, containing 20,317 cells, were hepatocytes; clusters

3, 6, 12, 19, 20 and 25, containing 10,299 cells, were monocytes;

clusters 1, 7 and 21, containing 6,824 cells, were T cells;

clusters 2 and 24, containing 8,693 cells, were macrophages;

clusters 5, 16, 23 and 29, containing 4,667 cells, were B cells;

clusters 8, 13 and 27, containing 3,749 cells, were endothelial

cells; cluster 14, containing 1,299 cells, was tissue stem cells;

cluster 15, containing 1,091 cells, was neutrophils; and cluster

24, containing 280 cells, was common myeloid progenitors (Fig. 1G).

| Figure 1.Processing of the GSE242889 dataset.

(A) Data from 57,219 cells were used for classification and

annotation analysis. (B) Correlation analysis of sequencing depth,

mitochondrial gene sequences and total intracellular sequences. (C)

Among the 21,625 genes analyzed, 1,500 had high variation and

20,125 had low intercellular variation. (D) A total of 17 PCs were

selected for further analysis. (E) Cells were divided into 30

separate clusters with a resolution of 0.8. (F) Heatmap displaying

the top 10 marker genes in each cluster. (G) UMAP plot

demonstrating the different cell types. CMP, common myeloid

progenitor; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; N,

normal; T, tumor. PCs, Principal Components; percent.mt, percentage

of the mitochondrial transcriptome. |

DEGs associated with RFS

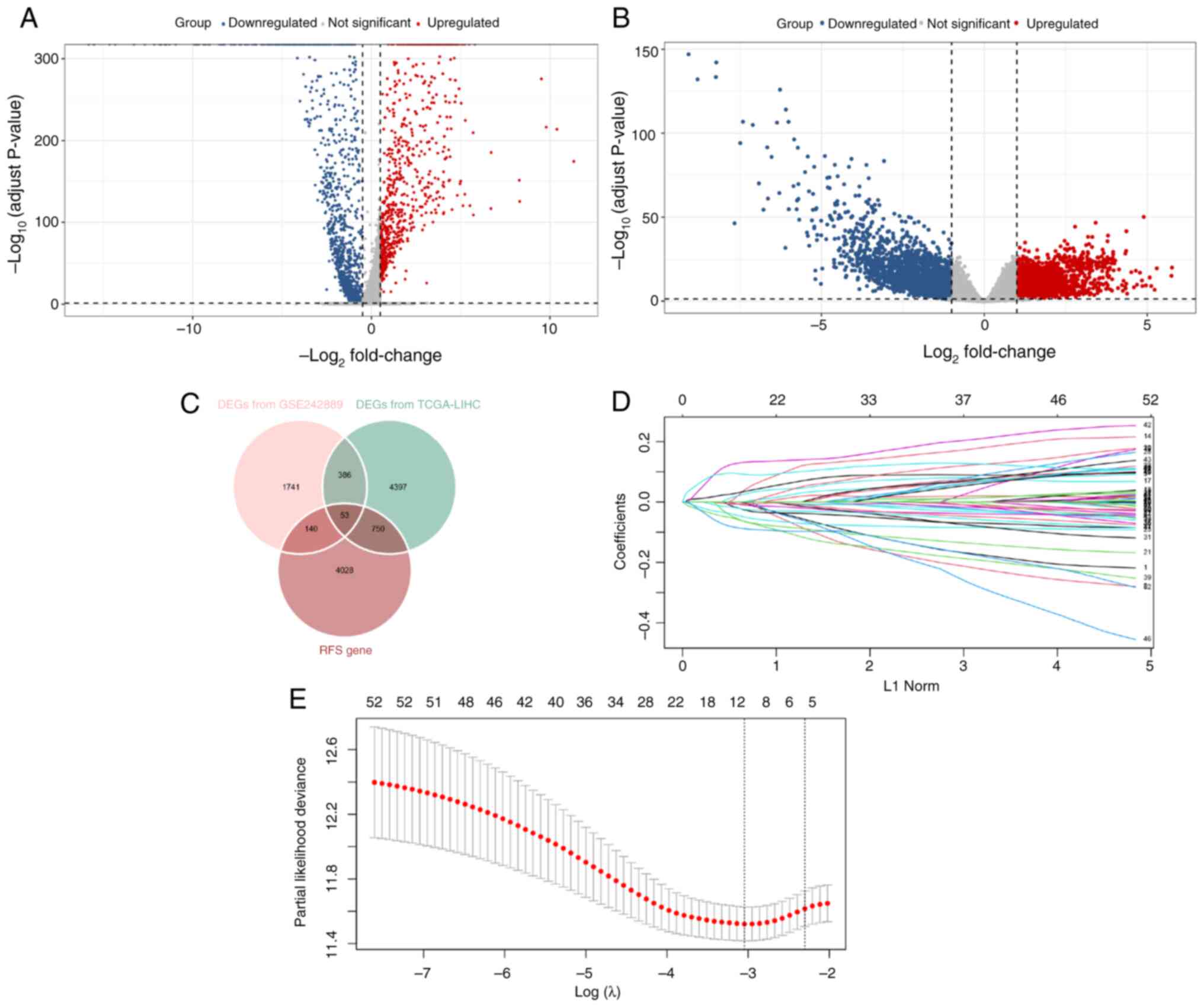

Among the 20,317 hepatocytes in the GSE242889

dataset, 17,560 cells were from HCC samples, and 2,757 cells were

from adjacent nontumor samples. A total of 2,320 DEGs were

identified in these cellular populations, comprising 752

significantly upregulated genes and 1,568 significantly

downregulated genes (Fig. 2A). In

the TCGA-LIHC dataset, 5,586 DEGs were detected, with 2,637

demonstrating increased expression and 2,949 showing decreased

expression levels (Fig. 2B). In

addition, the analysis revealed that 4,971 genes were significantly

associated with HCC recurrence outcomes. By intersecting these

results, 53 RFS-related DEGs were identified that were incorporated

into the prognostic signature (Fig.

2C).

Prognostic signature construction

Through regularization with LASSO Cox regression, a

risk score prognostic signature based on six genes

[cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), complement

factor H-related 3 (CFHR3), cytochrome P450 family 2

subfamily C member 9 (CYP2C9), high mobility group box 2

(HMGB2), IGLC2 and Jupiter microtubule-associated

homolog 1 (JPT1)] was constructed (Fig. 2D and E). The risk score was

calculated as follows: Risk score=(0.009 × expression of

CDKN2A)-(0.019 × expression of CFHR3)-(0.010 ×

expression of CYP2C9) + (0.019 × expression of

HMGB2)-(0.012 × expression of IGLC2) + (0.048 ×

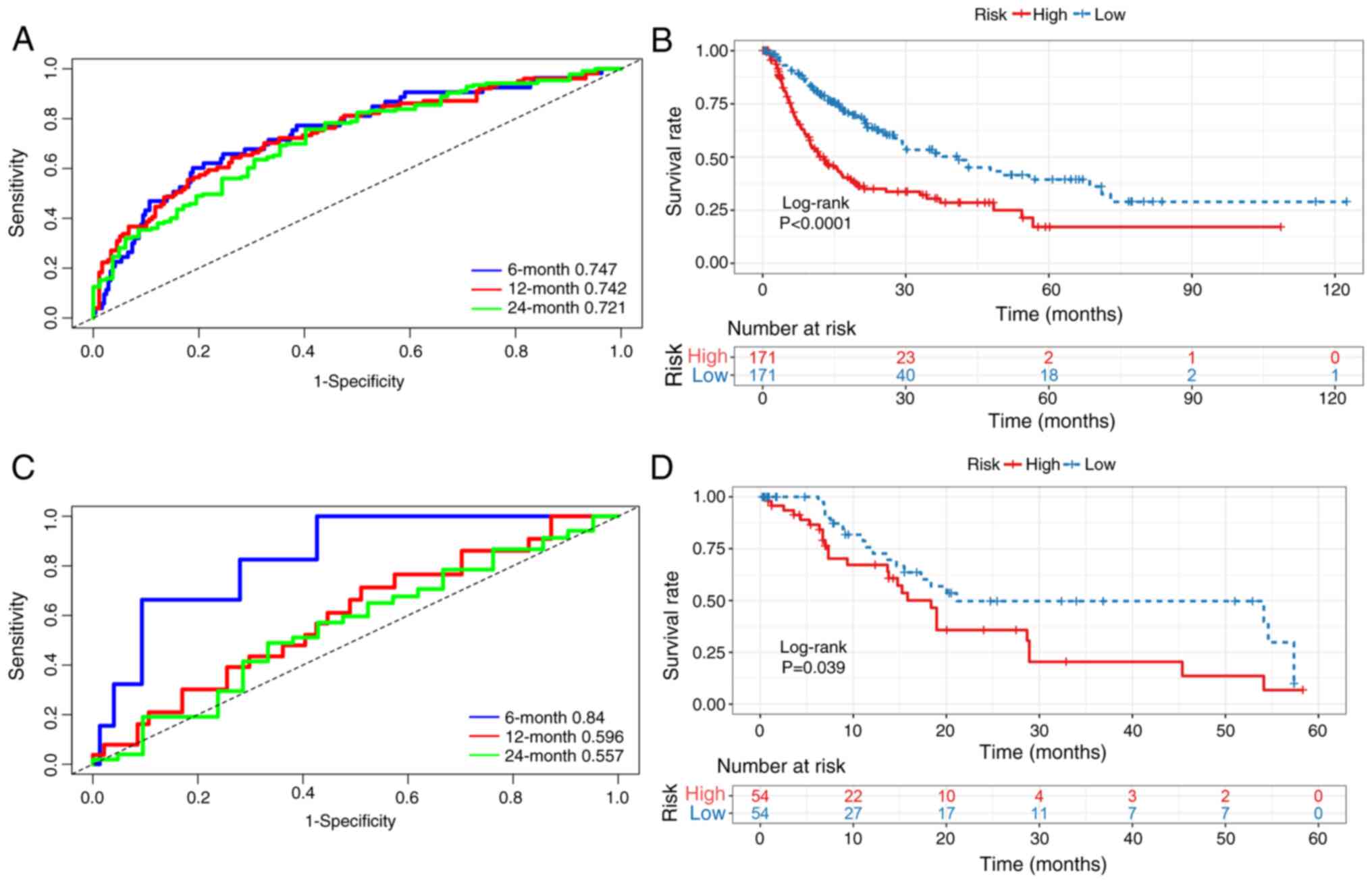

expression of JPT1). Time-dependent ROC analysis

demonstrated robust predictive accuracy for RFS, with 6-, 12- and

24-month area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.747, 0.742 and

0.721, respectively (Fig. 3A).

Furthermore, patients in the high-risk subgroup exhibited

significantly worse survival outcomes than those in the low-risk

subgroup (Fig. 3B).

Enrichment and immune infiltration

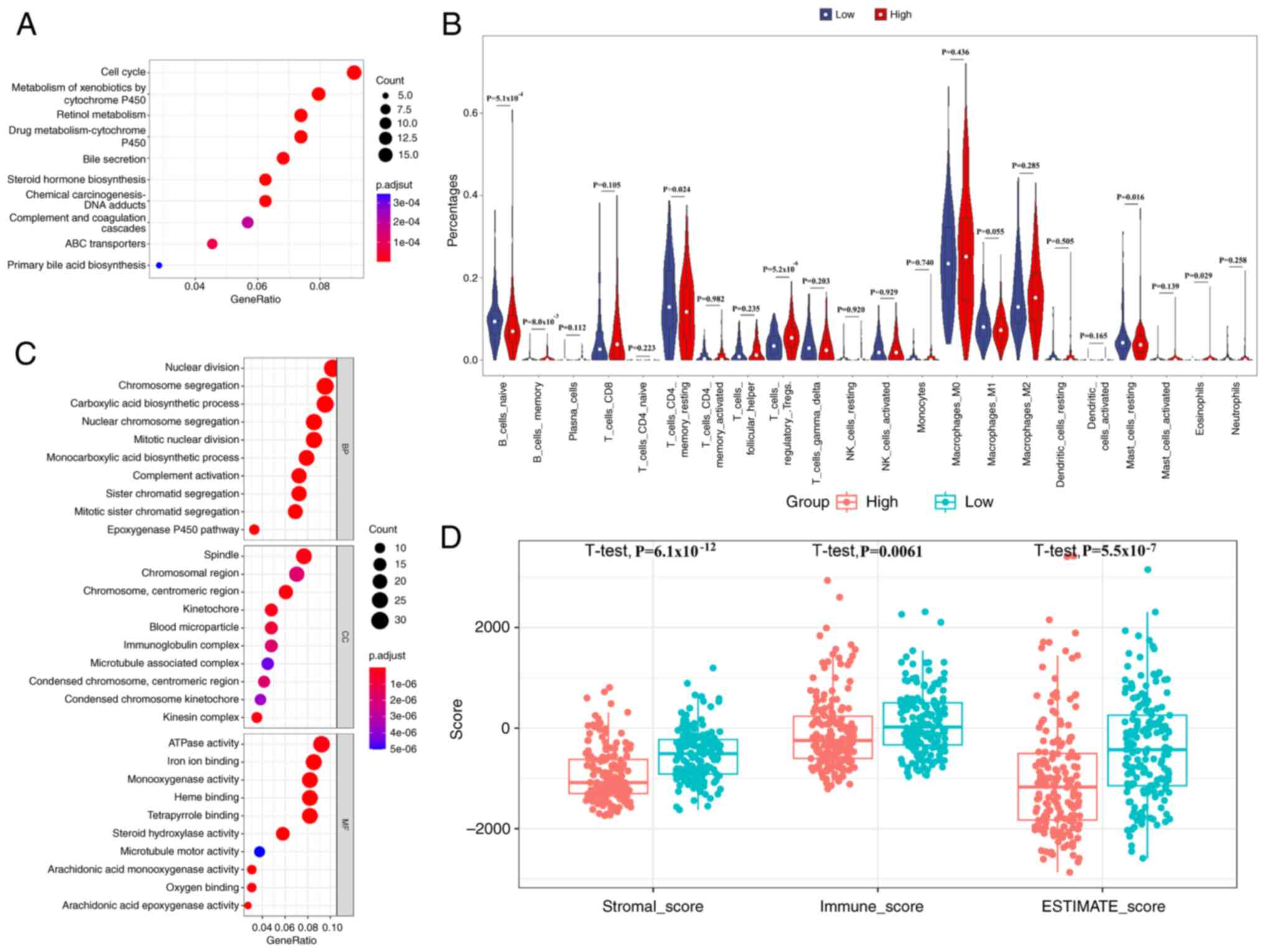

analyses

Differential expression analysis identified 525

genes distinguishing high- and low-risk patients. KEGG pathway

enrichment revealed predominant involvement in the ‘cell cycle’,

‘metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450’, ‘retinol

metabolism’, ‘drug metabolism-cytochrome P450’, ‘bile secretion’

and ‘chemical carcinogenesis-DNA adducts’ (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, GO analysis was used

to characterize the functional attributes of the identified DEGs

systematically (Fig. 4C).

Biological processes were predominantly associated with ‘nuclear

division’, ‘chromosome segregation’ and ‘carboxylic acid

biosynthetic process’, cellular components were enriched in

‘spindle’, ‘chromosomal region’ and ‘chromosome, centromeric

region’, and molecular functions were significantly represented by

‘ATPase activity’, ‘iron ion binding’ and ‘monooxygenase activity’.

The results of the GSEA analysis of the six genes are presented in

Fig. S1. In addition, CIBERSORT

analysis revealed that the high-risk cohort had significantly fewer

naive and memory B cells, memory resting CD4+ T cells

and resting mast cells than the low-risk cohort, indicating

immunosuppression (Fig. 4B).

Moreover, the stromal score, immune score and estimate score of the

high-risk group were significantly lower than those of the low-risk

group (Fig. 4D).

Prognostic independence of the risk

score signature

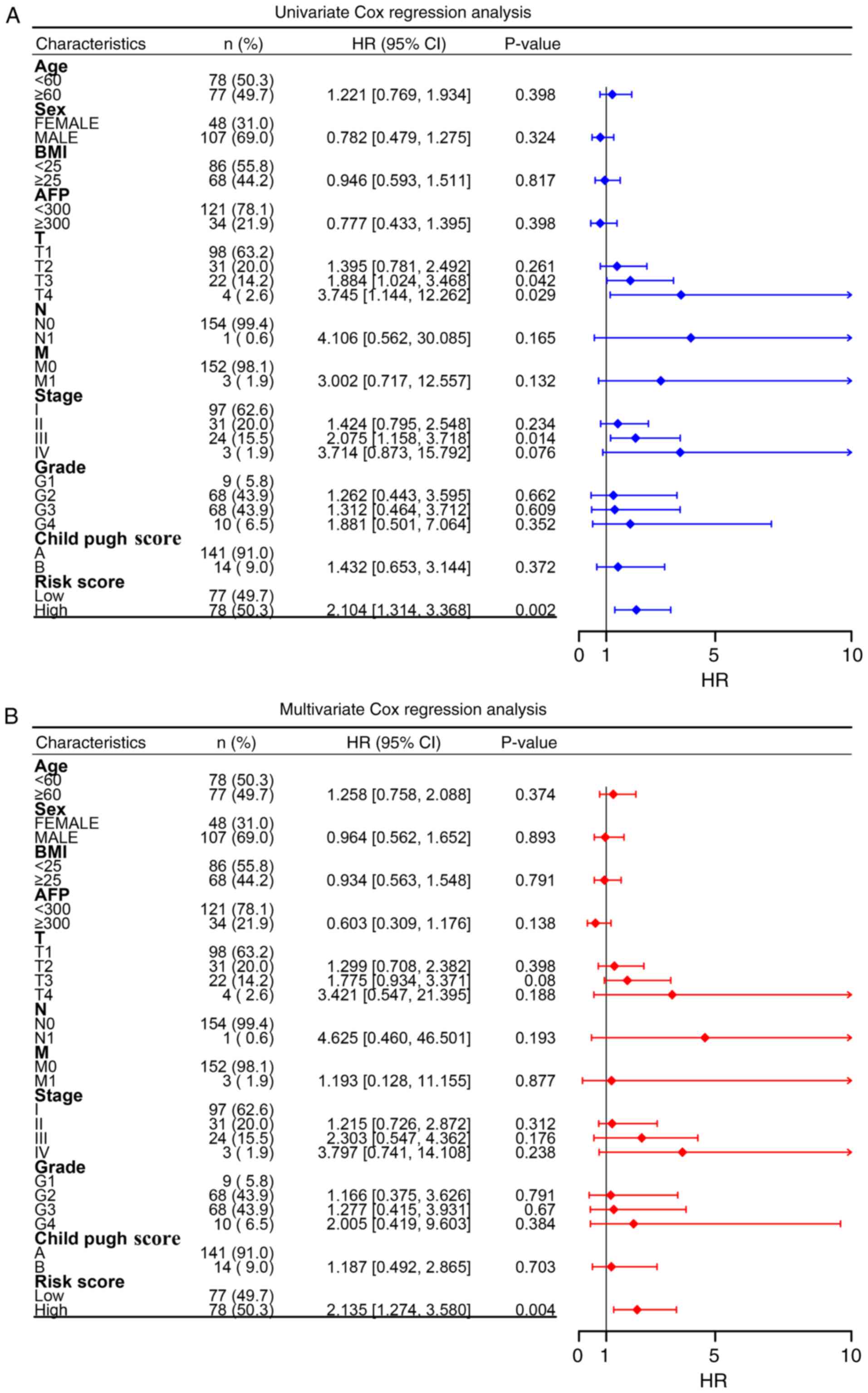

Univariate Cox regression revealed that T stage,

pathological stage and the risk score were significant predictors

of HCC recurrence (Fig. 5A).

However, subsequent adjustment demonstrated that only the

prognostic signature retained independent predictive value,

suggesting that HCC management could be augmented by incorporating

the molecular signature assessment for more precise recurrence

prediction (Fig. 5B).

Prognostic signature validation

As an externally validated dataset, the GSE76427

dataset was used to independently assess robustness and clinical

applicability of the prognostic signature. Time-dependent ROC

analysis demonstrated strong discriminative ability at 6 months

(AUC, 0.840), with a maintained predictive value at 12 months (AUC,

0.596) and 24 months (AUC, 0.557) (Fig.

3C). Consistent with these findings, Kaplan-Meier analysis

revealed significantly worse outcomes in the high-risk patients

compared with that in the low-risk patients (Fig. 3D), indicating the robust predictive

capacity of the integrated single-cell and bulk

transcriptome-derived signature.

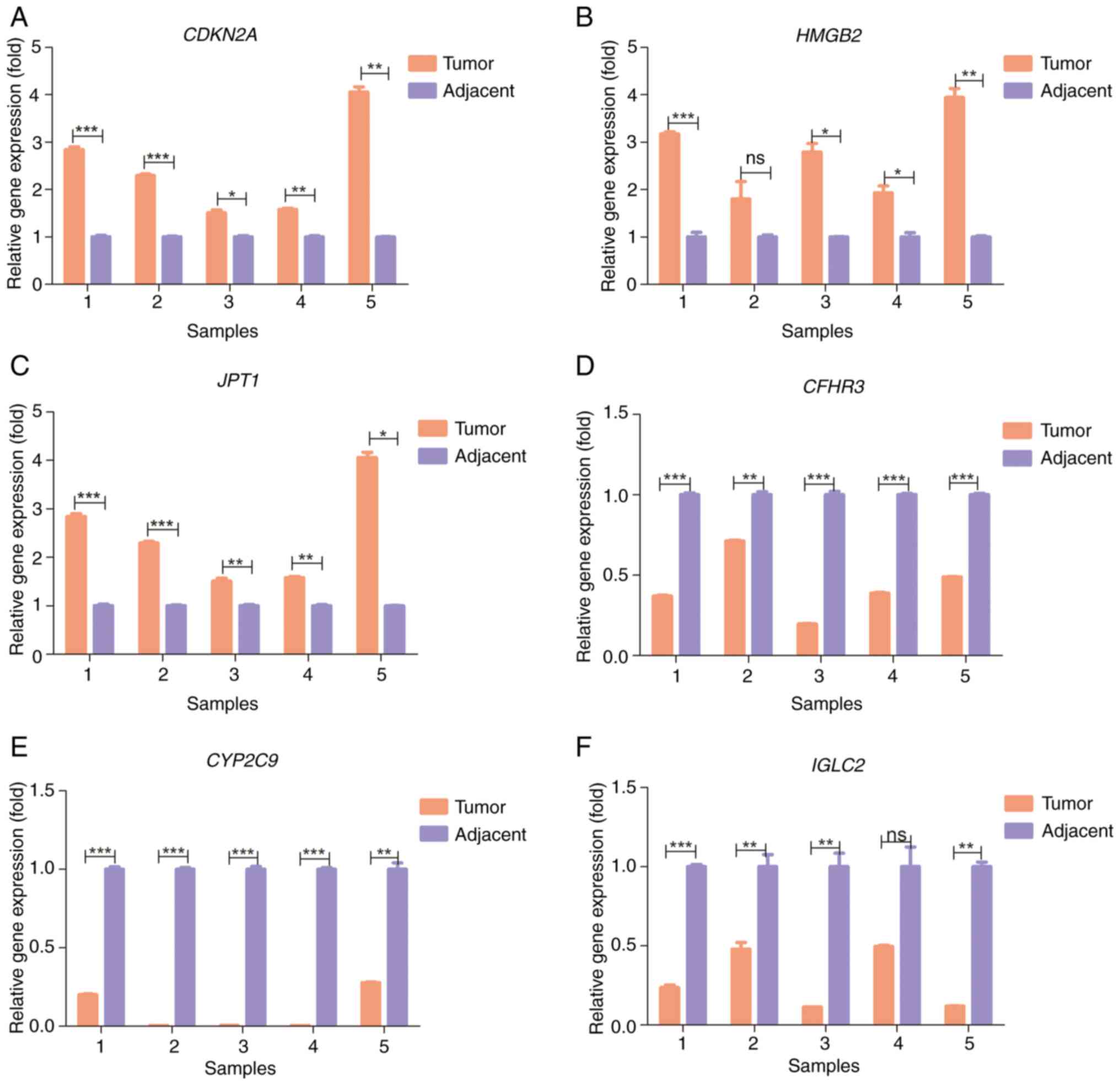

Clinical samples validation

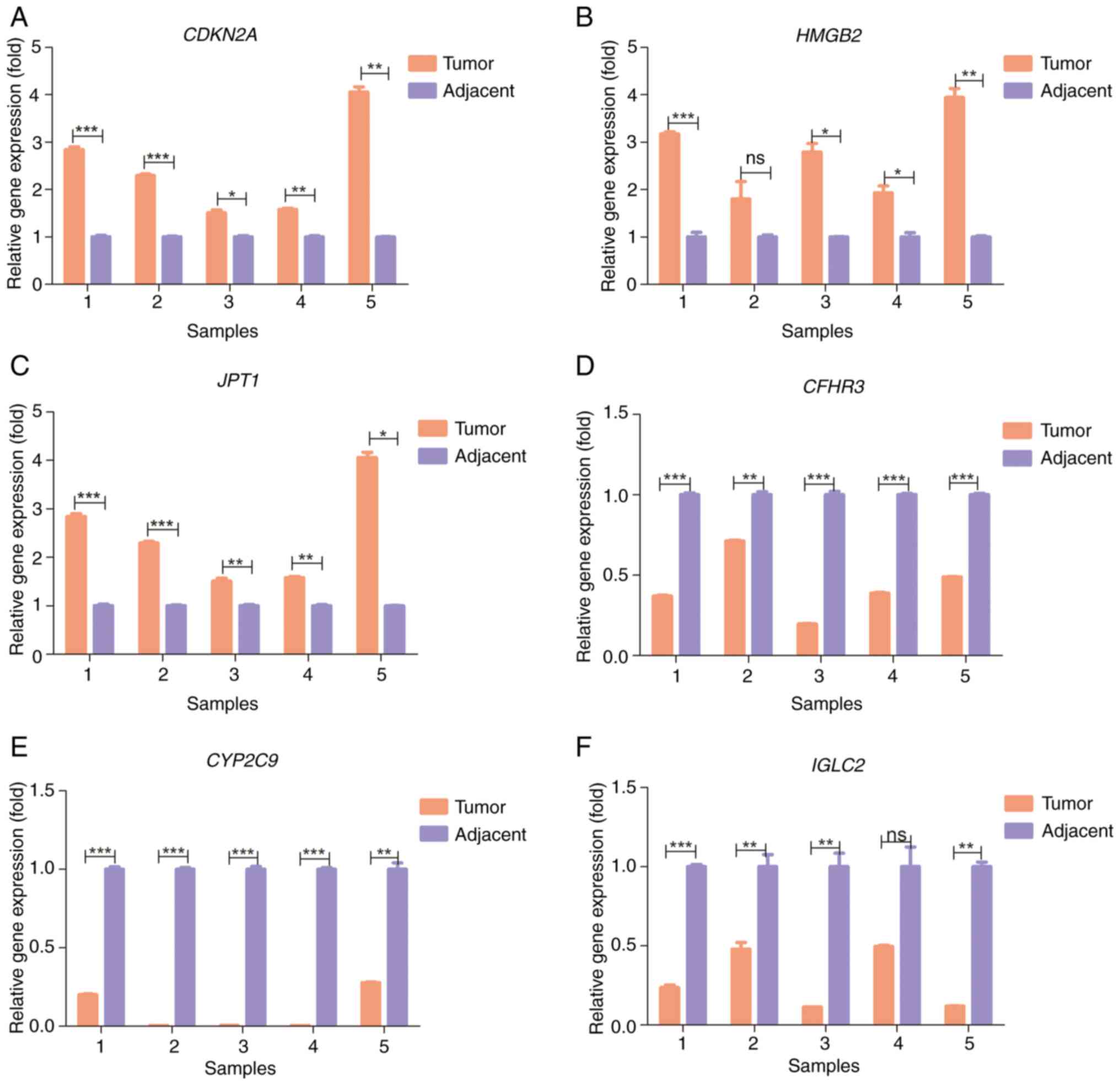

The RT-qPCR results revealed that CDKN2A,

HMGB2 and JPT1 were significantly upregulated in HCC

tumor tissues compared with in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 6A-C), whereas CFHR3, CYP2C9

and IGLC2 were significantly downregulated in tumor tissues,

compared with that in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 6D-F). Notably, these experimental

findings corroborated those of the prognostic signature,

reinforcing its validity and implying potential functional roles

for the signature genes.

| Figure 6.Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR of five pairs of tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues from

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Relative gene expression of

(A) CDKN2A, (B) HMGB2, (C) JPT1, (D)

CFHR3, (E) CYP2C9 and (F) IGLC2. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. CDKN2A, cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor 2A; CFHR3, complement factor H-related 3;

CYP2C9, cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9;

HMGB2, high mobility group box 2; IGLC2,

immunoglobulin λ constant 2; JPT1, Jupiter

microtubule-associated homolog 1; ns, not significant. |

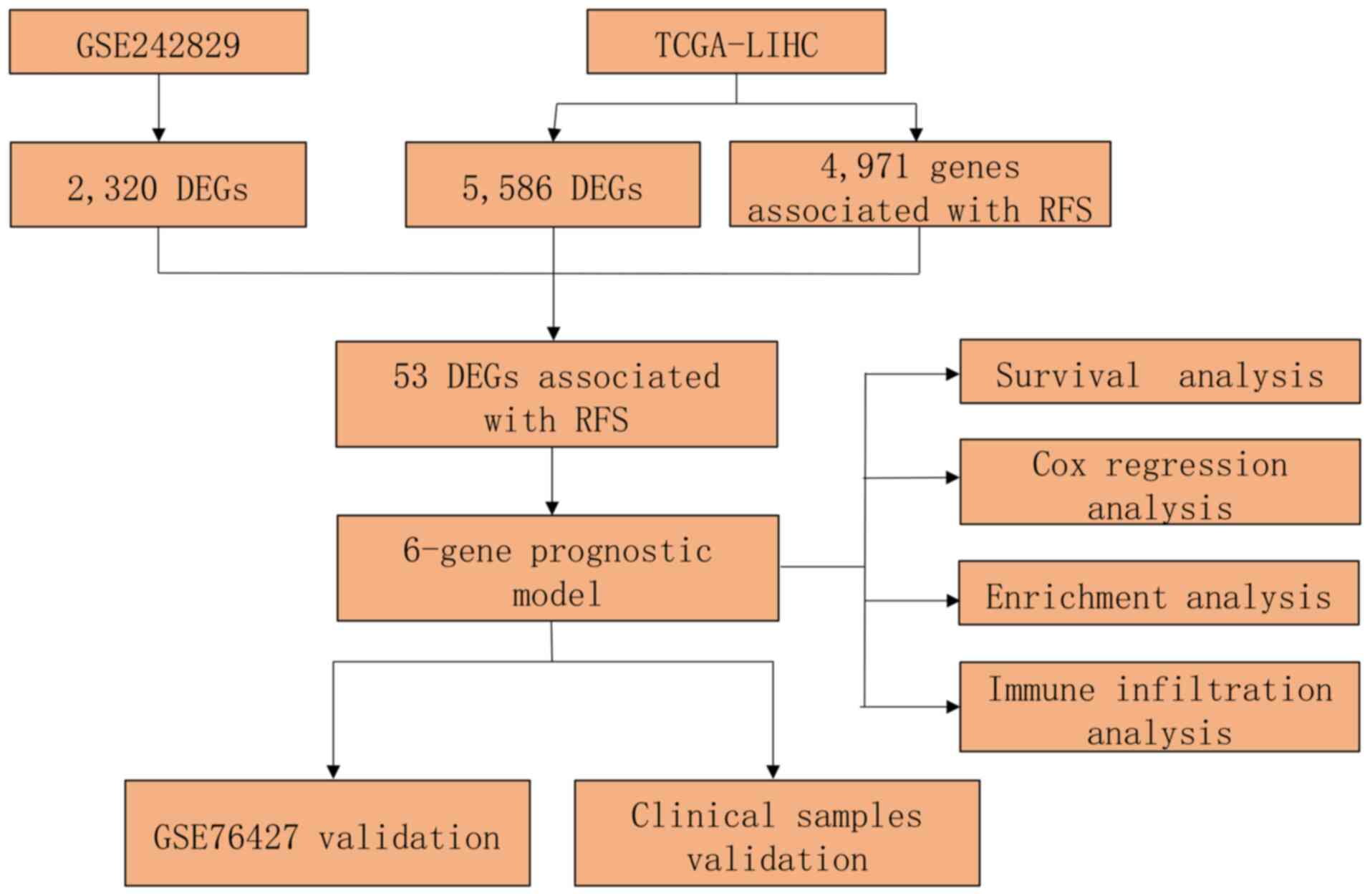

Discussion

The recurrence of HCC severely impairs patient

outcomes, representing a critical clinical challenge that demands

resolution. Although several prognostic models for HCC RFS have

been reported (8,29), there is a scarcity of models that

combine single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing for this purpose. The

present study first analyzed the scRNA-seq dataset GSE242889 and

extracted hepatocyte data to identify DEGs. The DEGs associated

with RFS from the bulk dataset TCGA-LIHC were simultaneously

acquired. LASSO Cox penalized regression analysis was subsequently

performed for these overlapping genes to establish the prognostic

model. External validation was performed with the GSE76427 dataset,

with additional experimental confirmation performed using RT-qPCR.

The overall study design is presented in Fig. 7.

In the training dataset, a six-gene (CDKN2A,

CFHR3, CYP2C9, HMGB2, IGLC2 and JPT1) prognostic

signature was constructed to calculate risk scores. To further

elucidate the biological functions of the six genes, GSEA was

performed and the supporting literature was searched. A previous

study suggested that, as an essential regulator of immune cell

functionality, CDKN2A could influence the outcomes of

patients with HCC through the modulation of tumor-associated

macrophages (30). CFHR3 is

a member of the complement factor H-related protein family

(31). Wan et al (32) reported that knockdown of

CFHR3 contributed to the invasion, proliferation and

migration of HCC by promoting STAT3 protein phosphorylation.

CYP2C9 mediates the breakdown of diverse carcinogens and

pharmaceutical molecules and has also been reported as a biomarker

for HCC diagnosis (33).

HMGB2 is a highly conserved nuclear protein that is a member

of the high mobility group protein family (34). Lu et al (35) reported that HMGB2 facilitates

HCC progression by activating the zinc finger E-box-binding

homeobox 1/vimentin axis. The results of the GSEA of the

aforementioned four genes are presented in Fig. S1A-D. JPT1 is also known as

HN1 and serves a critical role in HCC (36,37).

Notably, in the present study, GSEA indicated that it affects

multiple signaling pathways, such as fatty acid metabolism and bile

acid metabolism. Research on IGLC2 in HCC has not been

reported, to the best of our knowledge; however, the GSEA in the

present study suggested that epithelial mesenchymal transition,

inflammatory response and the interferon γ response could be

modulated by IGLC2.

The results of the KEGG analysis revealed

predominant enrichment of DEGs associated with the ‘cell cycle’,

‘metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450’, ‘drug

metabolism-cytochrome P450’ and ‘chemical carcinogenesis-DNA

adducts’. Several studies have suggested that the cell cycle is a

critical regulator of tumor growth and that the microenvironment

modulates HCC (38,39). Notably, in the present study,

CIBERSORT analysis revealed that the high-risk cohort had fewer

naive and memory B cells, memory resting CD4+ T cells

and resting mast cells than the low-risk cohort, which are features

of immunosuppression. Previous research has reported that

CD4+ T cells serve a pivotal role in orchestrating the

anti-HCC immune microenvironment, and their deficiency disrupts

intercellular immunological crosstalk and facilitates malignant

progression (40). Zhang et

al (41) investigated the

infiltration of B cells and their clinical significance in HCC and

reported that high infiltration of naive and memory B cells was

markedly associated with prolonged survival time. In addition, the

stromal score, immune score and estimate score of the high-risk

group in the presents study were lower than those of the low-risk

group. These findings indicate that there is a significant

difference in the immune microenvironment between the two groups,

and that this difference may be an important factor influencing

recurrence. Therefore, the aforementioned six genes could affect

HCC RFS via these molecular pathways.

In the validation dataset, GSE76427, the AUCs for

6-, 12- and 24-month RFS were 0.840, 0.596 and 0.557, respectively.

Kaplan-Meier analysis also revealed significantly worse outcomes in

high-risk patients than in low-risk patients. In addition, Cox

regression analysis revealed that only the prognostic signature

retained independent predictive value. Notably, the expression

levels of six genes were validated using RT-qPCR. The results

indicate that the prognostic signature has good credibility and

offers value as an independent predictor of the prognosis of

patients with HCC. Unlike previously reported models for predicting

RFS in patients with HCC, the prognostic signature in the present

study was constructed by integrating scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq

datasets. Using the prognostic signature, the individualized

survival probability could be calculated for each patient according

to the expression levels of the six genes. For patients at high

risk of recurrence, the model could prompt physicians to pay

greater attention to these patients and offer support for

physicians in making clinical decisions.

In summary, the present study constructed a

prognostic model for predicting RFS in patients with HCC via

integrated analysis of scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data. Unlike most

studies, the present study combined the model with the clinical

information of patients to evaluate whether the model is an

independent prognostic factor affecting survival. Furthermore,

experiments were used to assess the expression of the genes in the

model using clinical samples. This may partially compensate for the

shortcomings of other studies and greatly enhances the clinical

applicability of the model in the present study. Moreover, the

model could serve as a valuable reference tool for clinicians.

However, there are several limitations of the present study. First,

in the validation dataset, the time-dependent AUCs at 12 and 24

months (0.596 and 0.557, respectively) were relatively low,

possibly because as the follow-up period increases, the proportion

of patient deaths caused by non-tumor-related factors increases.

Additionally, as the present study was retrospective, further

prospective, large-scale trials are needed to validate the model.

Finally, the present study did not perform an in-depth experimental

exploration of how the six model genes affect HCC RFS, which needs

to be further explored.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 91210050).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LZ, WY and WL designed the study. WL, QH and ZL

performed the bioinformatic and statistical analyses. HL and XG

collected the stored clinical samples and acquired the data for

analysis. WY, JM and QL performed the experiments. WY and WL wrote

the original manuscript. LZ reviewed and revised the manuscript.

LZ, WY and WL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

(Nanchang, China; approval no. 2024-078). Documented written

informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

FC

|

fold-change

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

GSEA

|

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

LASSO

|

least absolute shrinkage and selection

operator

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

RFS

|

recurrence-free survival

|

|

RNA-seq

|

RNA sequencing

|

|

scRNA-seq

|

single-cell RNA-seq

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J,

Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA and Bray F: Global burden of 5 major

types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology.

159:335–349.e15. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Daher S, Massarwa M, Benson AA and Khoury

T: Current and future treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: An

updated comprehensive review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 6:69–78. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 380:1450–1462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Martínez-Chantar ML, Avila MA and Lu SC:

Hepatocellular carcinoma: Updates in pathogenesis, detection and

treatment. Cancers (Basel). 12:27292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Singal AG, Kudo M and Bruix J:

Breakthroughs in hepatocellular carcinoma therapies. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21:2135–2149. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gu JX, Zhang X, Miao RC, Xiang XH, Fu YN,

Zhang JY, Liu C and Qu K: Six-long non-coding RNA signature

predicts recurrence-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma.

World J Gastroenterol. 25:220–232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang W, Wang L, Xie X, Yan Y, Li Y and Lu

Q: A gene-based risk score model for predicting recurrence-free

survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer.

21:62021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guo DZ, Zhang X, Zhang SQ, Zhang SY, Zhang

XY, Yan JY, Dong SY, Zhu K, Yang XR, Fan J, et al: Single-cell

tumor heterogeneity landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma:

Unraveling the pro-metastatic subtype and its interaction loop with

fibroblasts. Mol Cancer. 23:1572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li X, Li R, Miao X, Zhou X, Wu B, Cao J,

Wang C, Li S and Cai J: Integrated single cell analysis reveals an

atlas of tumor associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Inflammation. 47:2077–2093. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sun Y, Wu L, Zhong Y, Zhou K, Hou Y, Wang

Z, Zhang Z, Xie J, Wang C, Chen D, et al: Single-cell landscape of

the ecosystem in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell.

184:404–421.e16. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou Q, Tao C, Ge Y, Yuan J, Pan F, Lin X

and Wang R: A novel single-cell model reveals

ferroptosis-associated biomarkers for individualized therapy and

prognostic prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Biol.

22:1332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yu L, Shen N, Shi Y, Shi X, Fu X, Li S,

Zhu B, Yu W and Zhang Y: Characterization of cancer-related

fibroblasts (CAF) in hepatocellular carcinoma and construction of

CAF-based risk signature based on single-cell RNA-seq and bulk

RNA-seq data. Front Immunol. 13:10097892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang T, Dang N, Tang G, Li Z, Li X, Shi B,

Xu Z, Li L, Yang X, Xu C and Ye K: Integrating bulk and single-cell

RNA sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity and immune

infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 16:2195–2213.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li K, Zhang R, Wen F, Zhao Y, Meng F, Li

Q, Hao A, Yang B, Lu Z, Cui Y and Zhou M: Single-cell dissection of

the multicellular ecosystem and molecular features underlying

microvascular invasion in HCC. Hepatology. 79:1293–1309. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Grinchuk OV, Yenamandra SP, Iyer R, Singh

M, Lee HK, Lim KH, Chow PK and Kuznetsov VA: Tumor-adjacent tissue

co-expression profile analysis reveals pro-oncogenic ribosomal gene

signature for prognosis of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol

Oncol. 12:89–113. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Korsunsky I, Millard N, Fan J, Slowikowski

K, Zhang F, Wei K, Baglaenko Y, Brenner M, Loh PR and Raychaudhuri

S: Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data

with Harmony. Nat Methods. 16:1289–1296. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lai W, Xie R, Chen C, Lou W, Yang H, Deng

L, Lu Q and Tang X: Integrated analysis of scRNA-seq and bulk

RNA-seq identifies FBXO2 as a candidate biomarker associated with

chemoresistance in HGSOC. Heliyon. 10:e284902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E

and Satija R: Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across

different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol.

36:411–420. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Friedman J, Hastie T and Tibshirani R:

Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate

descent. J Stat Softw. 33:1–22. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 4:26122013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Daniele B, Annunziata M, Barletta E,

Tinessa V and Di Maio M: Cancer of the liver italian program (CLIP)

score for staging hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 37 (Suppl

2):S206–S209. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Moris D, Martinino A, Schiltz S, Allen PJ,

Barbas A, Sudan D, King L, Berg C, Kim C, Bashir M, et al: Advances

in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: An overview of the

current and evolving therapeutic landscape for clinicians. CA

Cancer J Clin. May 20–2025.(Epub ahead of print). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kong J, Wang T, Shen S, Zhang Z, Yang X

and Wang W: A genomic-clinical nomogram predicting recurrence-free

survival for patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma.

PeerJ. 7:e79422019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Luo JP, Wang J and Huang JH: CDKN2A is a

prognostic biomarker and correlated with immune infiltrates in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Rep. 41:BSR202111032021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Skerka C, Chen Q, Fremeaux-Bacchi V and

Roumenina LT: Complement factor H related proteins (CFHRs). Mol

Immunol. 56:170–180. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wan Z, Li X, Luo X, Wang B, Zhou X and

Chen A: The miR-590-3p/CFHR3/STAT3 signaling pathway promotes cell

proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging

(Albany NY). 14:5783–5799. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu D, Green B, Marrone A, Guo Y, Kadlubar

S, Lin D, Fuscoe J, Pogribny I and Ning B: Suppression of CYP2C9 by

microRNA hsa-miR-128-3p in human liver cells and association with

hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 5:85342015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Starkova T, Polyanichko A, Tomilin AN and

Chikhirzhina E: Structure and functions of HMGB2 protein. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:83342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lu K, Zhao T, Yang L, Liu Y, Ruan X, Cui L

and Zhang Y: HMGB2 upregulation promotes the progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the activation of

ZEB1/vimentin axis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 14:2178–2191. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li M, Pang X, Xu H and Xiao L: CircSCMH1

accelerates sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma by

regulating HN1 expression via miR-485-5p. Mol Biotechnol.

67:304–316. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang R, Fu Y, Yao M, Cui X, Zhao Y, Lu X,

Li Y, Lin Y and He S: The HN1/HMGB1 axis promotes the proliferation

and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma and attenuates the

chemosensitivity to oxaliplatin. FEBS J. 289:6400–6419. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Qu M, Zhang G, Qu H, Vu A, Wu R, Tsukamoto

H, Jia Z, Huang W, Lenz HJ, Rich JN and Kay SA: Circadian regulator

BMAL1::CLOCK promotes cell proliferation in hepatocellular

carcinoma by controlling apoptosis and cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 120:e22148291202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu D, Zhang C, Liao G, Leng K, Dong B, Yu

Y, Tai H, Huang L, Luo F, Zhang B, et al: Targeting

uridine-cytidine kinase 2 induced cell cycle arrest through dual

mechanism and could improve the immune response of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 27:1052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang S, Meng L, Xu N, Chen H, Xiao Z, Lu

D, Fan X, Xia L, Chen J, Zheng S, et al: Hepatocellular

carcinoma-specific epigenetic checkpoints bidirectionally regulate

the antitumor immunity of CD4 + T cells. Cell Mol Immunol.

21:1296–1308. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang Z, Ma L, Goswami S, Ma J, Zheng B,

Duan M, Liu L, Zhang L, Shi J, Dong L, et al: Landscape of

infiltrating B cells and their clinical significance in human

hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 8:e15713882019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|