Introduction

Globally, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PAAD)

accounted for 511,000 new cases and 467,000 deaths in 2022

(according to GLOBOCAN data), ranking as the sixth leading cause of

cancer-related mortality worldwide at present and contributing to

5% of all cancer-associated deaths. This mortality rate places PAAD

among the malignancies with the poorest prognosis (1). PAAD, while exhibiting a relatively low

incidence rate, carries a disproportionately high mortality rate.

Global epidemiological data indicate a rising incidence of PAAD

annually (2). Although less

prevalent than a number of other malignancies, PAAD imparts a worse

prognosis due to challenges in early detection and effective

treatment (3). Established risk

factors for PAAD development include smoking, obesity, high-fat

diets, chronic pancreatitis and genetic predisposition. Smoking

constitutes a primary modifiable risk factor, while genetic and

environmental influences also contribute markedly to disease

susceptibility (4). Current

therapeutic modalities for PAAD are primarily limited to surgical

resection, supplemented by radiotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted

agents such as Erlotinib (5).

However, clinical outcomes often remain suboptimal. Immunotherapy

has emerged as a promising therapeutic paradigm, aiming to harness

the host immune system to eradicate cancer cells (6). Consequently, immune checkpoint

inhibitors and related immunotherapeutics are being evaluated in

subsets of patients with PAAD (7).

However, the inherent immunological ‘cold’ nature of PAAD presents

a major barrier to immunotherapy efficacy. Converting these

immunologically quiescent tumors into ‘hot’, immune-responsive

lesions represents an important requirement for immunotherapy

efficacy (8).

The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway

represents a pivotal innate immune modulator with the potential to

convert immunologically ‘cold’ tumors into ‘hot’ microenvironments

(9). STING activation triggers the

production of type I interferons (IFNs) and other cytokines,

thereby reshaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) and modulating

immune cell activity (10). While

STING pathway activation has been linked to tumor progression and

metastasis in certain contexts, often regulated by epigenetic

mechanisms such as DNA methylation (11), its therapeutic manipulation holds

promise. At present, STING agonists are undergoing clinical trials

to evaluate their efficacy in patients with advanced cancer.

Furthermore, the potential application of STING agonists in

early-stage disease (12),

particularly before the establishment of robust immune evasion

mechanisms within the TME, is an active area of investigation

(13). Within the specific context

of PAAD, preclinical studies suggest that STING activation can

stimulate type I IFN production and promote dendritic cell (DC)

maturation (14). Despite this

promise, successful clinical translation faces notable hurdles,

including: i) An incomplete understanding of PAAD-specific STING

interactome dynamics (15); ii) the

induction of compensatory immunosuppressive mechanisms (e.g.,

myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion) that counteract agonist

efficacy (16); and notably, iii)

the absence of validated predictive biomarkers to stratify patients

likely to respond to STING activation treatment (17). Moreover, the efficacy of STING

agonists in PAAD may be contingent upon the specific TME

composition, patient genetics and the specific combination partners

used (e.g., chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors), as

synergistic interactions can significantly enhance their

therapeutic effect (18,19). In conclusion, elucidating the

mechanistic role and therapeutic potential of the STING pathway in

cancer immunotherapy has become a major research focus. Such

investigations are important not only for deepening the present

understanding of PAAD pathogenesis but also for developing novel

and effective therapeutic strategies against recalcitrant PAAD

malignancy.

The present study aimed to systematically map the

core regulatory components within the STING signaling-protein

interactome to construct a prognostic signature for PAAD.

Interactome mapping was pursued through comprehensive

protein-protein interaction network-centrality analysis.

Collectively, by decoding the STING-centered protein network, the

present study seeks to identify novel tractable targets for

potentiating STING agonism in PAAD treatment.

Material and methods

Bioinformatics

Patient data

Samples from a total of 353 patients with pancreatic

cancer were integrated from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA)-pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n=178) and GSE224564 (n=175)

datasets, and cases with incomplete clinical data were excluded.

The RNA sequencing and clinical data of 178 patients with PAAD were

obtained from TCGA (https://www.cancer.gov/). The PAAD dataset GSE224564

(20) was downloaded from GEO

(www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi) and included

the RNA sequencing and clinical data of 175 patients with PAAD.

Bioinformatic analysis

Differential gene expression between STING-based

subtypes (C1 vs. C2) was analyzed using DESeq2 (v1.38.3).

Functional enrichment was performed via clusterProfiler (v4.0)

using annotations from the Gene Ontology Consortium (http://geneontology.org) and KEGG Pathway Database

(https://www.genome.jp/kegg/), with

significance defined as a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value

<0.05. TME scores (immune/stromal) and tumor purity were

calculated using the ESTIMATE algorithm (v1.0.13; http://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/estimate/).

Immune cell infiltration was deconvoluted with CIBERSORTx

(https://cibersortx.stanford.edu) using

the LM22 signature matrix and 1,000 permutations. Mutation profiles

were processed via Maftools (v2.16.0) with TCGA somatic mutation

data. All statistical thresholds are explicitly stated in figure

legends. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed to

interpret the functional significance of the identified genes. GO

analysis (http://geneontology.org) was utilized

to categorize genes into biological processes, molecular functions

and cellular components. KEGG pathway analysis (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) was used to identify

significantly enriched signaling and metabolic pathways. The

analyses were performed using the clusterProfiler R package (v4.0),

with a significance threshold of an adjusted P-value <0.05.

Construction of STING pathway-related

gene prognostic signature in PAAD

Curated Cancer Cell Atlas (www.weizmann.ac.il/sites/3CA/) was used to identify

the expression of STING in the TME. STRING (cn.string-db.org) and

Genemiania (genemania.org) were used to identify 26 STING

pathway-related genes (Table SI).

The association between STING pathway-related genes and the

prognosis of patients with PAAD was evaluated via univariate cox

regression. A least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

(LASSO) Cox regression analysis was used for constructing the

signature for STING pathway-related genes. Bioinformatics analysis

of PAAD transcriptomic data from public cohorts (TCGA and GEO)

revealed that the majority of STING-related genes were highly

expressed in PAAD (significance defined as |log2(fold change)|>1

and adjusted P-value <0.05). Based on the expression levels of

these genes, PAAD patients from these cohorts were stratified into

high-risk and low-risk groups. These STING-related genes exerted

differential impacts on tumor mutational burden, immune

infiltration and response to immunotherapy. Prognostic STING

pathway-related genes were then selected via stepwise multivariate

Cox regression using the Akaike information criterion for model

optimization. Utilizing these genes, a prognostic model was

constructed (hazard ratio, 2.639; P<0.001) and externally

validated. Risk Score= ∑k=0ncoep (k)*x(k), where coef(k) and x(k)

represented the regression coefficients. The groups were divided

into high- and low-risk groups using the median risk score (1.476)

as the cut-off. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression were

used to evaluate independent factors, including clinical features

and the risk score in PAAD. The Tumor Immune Dysfunction and

Exclusion (TIDE) computational platform (https://tide.dfci.harvard.edu) was used to predict

response to immunotherapy in high- and low-risk PAAD patient groups

stratified by the STING-signature risk score.

Online database

The GEPIA (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/), Cbioportal (www.cbioportal.org), HPA (www.proteinatlas.org) and TISIDB

(cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php) databases were used to evaluate gene

expression, survival and clinical stage and grade (21) in patients with PAAD.

In vitro assays

Cell culture

293T cells (ATCC® CRL-3216™) and murine

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma Panc02 cells (cat. no. CRL-2553)

were cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium (Corning, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone™;

Cytiva). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5%

CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

routinely subcultured every 2–3 days using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cell density was

maintained at 60–80% confluency.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral vectors expressing short hairpin RNAs

(shRNAs) targeting interferon-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats (IFIT2), or corresponding scrambled

control shRNAs (sh-NC), were constructed using the pLKO.1-puro

backbone (cat. no. 8453; Addgene, Inc.). The shRNA sequences

(Table SII) were designed using

the Broad Institute TRC portal (v2.0) and validated by BLAST

(https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to ensure

target specificity. For overexpression, full-length zinc finger

DHHC-type containing 1 (ZDHHC1) complementary DNA (OriGene

Technologies, Inc.) was cloned into the pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro

vector (cat. no. CD510B-1; System Biosciences, LLC). In the ZDHHC1

overexpression experiment, cells transfected with the empty vector

(pCDNA3.1) served as the negative control to confirm that any

observed phenotypic changes were attributable to the expression of

the target gene rather than the vector itself. All constructs were

verified by Sanger sequencing. Lentiviral particles were produced

using a second-generation system by co-transfecting 293T cells

[American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)] cultured at 37°C with the

transfer vector (shRNA or overexpression plasmid), packaging

plasmid psPAX2 (cat. no. 12260; Addgene, Inc.) and envelope plasmid

pMD2.G (cat. no. 12259; Addgene, Inc.) at a 4:3:1 ratio (6:4.5:1.5

µg) using Lipofectamine® 3000 (cat. no. L3000015; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Following a 48- to 72-h transfection

period, viral supernatants were harvested, filtered through 0.45-µm

PVDF membranes, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (25,000 ×

g, at 4°C for 2 h). Panc02 cells were seeded in 6-well plates

(5×104 cells/well) and incubated until 40% confluency.

Cells were transduced with a multiplicity of infection of 15 used

to infect cells with lentivirus in the presence of 8 µg/ml

polybrene (cat. no. H9268; MilliporeSigma). After 24 h, the medium

was replaced with fresh complete DMEM. Transduced cells were

selected using 5 µg/ml puromycin (cat. no. ant-pr-1; InvivoGen) for

72 h. Positively selected cells were then maintained in 2 µg/ml

puromycin-containing medium for all subsequent experiments to

ensure stable expression. Knockdown or overexpression efficacy was

validated 7 days post-selection.

Western blotting

Panc02 cells (ATCC CRL-2553™) were lysed in RIPA

buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium

deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor

cocktail (cat. no. 11836170001; Roche Diagnostics, GmbH). Protein

concentration was determined by BCA assay. Samples (40 µg/lane)

were denatured in Laemmli buffer at 100°C for 10 min, separated on

10% gels using SDS-PAGE (GenScript), and transferred to PVDF

membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma). Membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat skimmed milk (cat. no. 1706404; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) in 0.1% TBST for 1 h at 25°C, followed by

overnight incubation at 4°C with the following primary antibodies:

Anti-IFIT2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab305231; Abcam), anti-ZDHHC1

(1:1,000; cat. no. ab223042; Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:1,000; cat.

no. CST 2118; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). After TBST washes,

membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:100,000; cat. no. 31460; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 1 h at 25°C. Signals were developed using SuperSignal™

West Pico PLUS substrate (cat.no. 34577; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and imaged with a ChemiDoc™ MP System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) controlled by Image Lab™ Software v6.1. Band intensity was

quantified by built-in densitometry tools.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8 assay)

In a standard 96-well plate, cells were seeded at

5,000 Panc02 cells per well (in 100 µl DMEM). The cells were then

incubated in a 37°C, 5% CO2 cell culture incubator for

24 h. Having pre-calculated the corresponding seeding volume per

well, CCK-8 solution (cat. no. CK04-13; Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.)

was added to each well at 10% of the total volume of the medium,

and the reaction proceeded in the dark for 1 h. The difference

between the OD values of the treatment group and sh-NC or vehicle

was calculated, then divided by the difference between the OD

values of the control cells. The resulting value was multiplied by

100% to obtain the cell survival rate.

TUNEL assay

Cells were seeded onto sterile glass coverslips

placed in 24-well culture plates at a density of 5×104

cells per well and allowed to adhere for 24 h. After adherence,

cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 30

min. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS (5 min per wash).

Cell membranes were permeabilized by incubation with pre-chilled

PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 on ice for 2 min, followed by two

washes with PBS. The TUNEL assay was performed using the In Situ

Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (cat. no. 11684795910; Roche

Diagnostics, GmbH). The TUNEL reaction mixture was prepared

according to the manufacturer's protocol by combining 50 µl Enzyme

Solution (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) with 450 µl Label

Solution (fluorescein-dUTP). This mixture was applied to cover the

samples, which were then incubated at 37°C in a humidified dark

chamber for 60 min. Unbound reagents were removed by washing three

times with PBS (5 min per wash). Nuclei were counterstained with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at 1 µg/ml in PBS for 10 min

at room temperature in the dark, followed by two final washes with

PBS. Samples were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant

(cat. no. P36930; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Apoptotic cells

(green fluorescence) and total nuclei (blue fluorescence) were

visualized using an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus

Corporation). Quantification was performed by counting

TUNEL-positive cells and total DAPI-stained nuclei in ≥10 randomly

selected fields of view per sample at ×200 magnification.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis component of this

study, R software (version 4.3.2; The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing) was used. This open-source software was downloaded from

the Comprehensive R Archive Network (https://cran.r-project.org/). Continuous variables

(expressed as mean ± standard deviation upon confirmation of

normality by Shapiro-Wilk test) and categorical variables (reported

as frequencies with proportions) were compared through

multivariable regression models adjusted for demographic/clinical

confounders; statistical significance was defined as bidirectional

P<0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple

comparisons. Survival endpoints were evaluated via stratified

log-rank tests and hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals). Data

from CCK-8, TUNEL and western blots were treated as continuous

variables. Differences between two experimental groups were

assessed exclusively by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests.

Differences between multiple experimental groups and a single

control group were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. To evaluate the monotonic

relationship between risk score and dendritic cells activated

score, Spearman's rank-order correlation analysis was employed.

This non-parametric method was selected since the data were either

ordinal or continuous but failed to meet the assumption of

normality, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

STING as an adverse prognostic factor

in PAAD

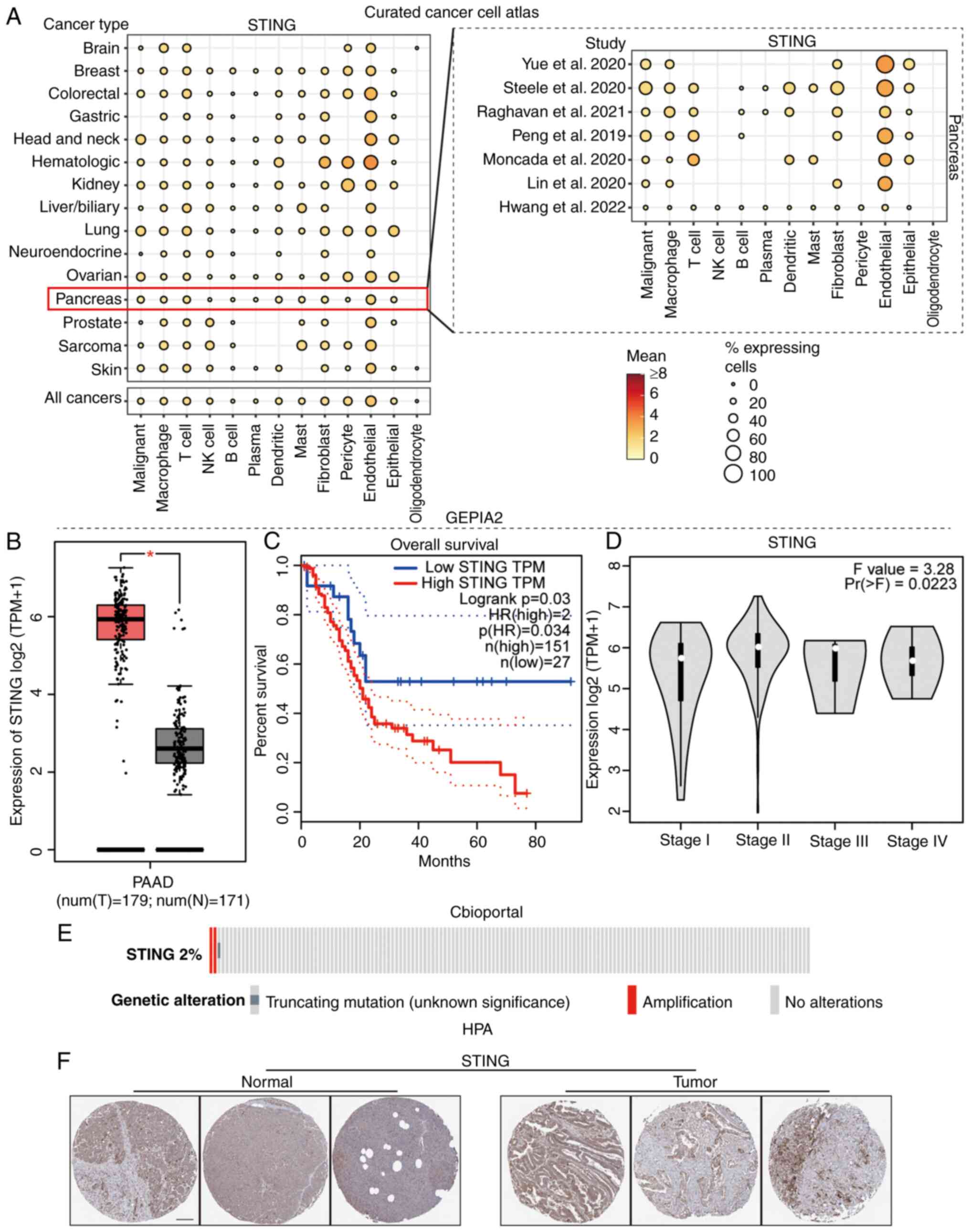

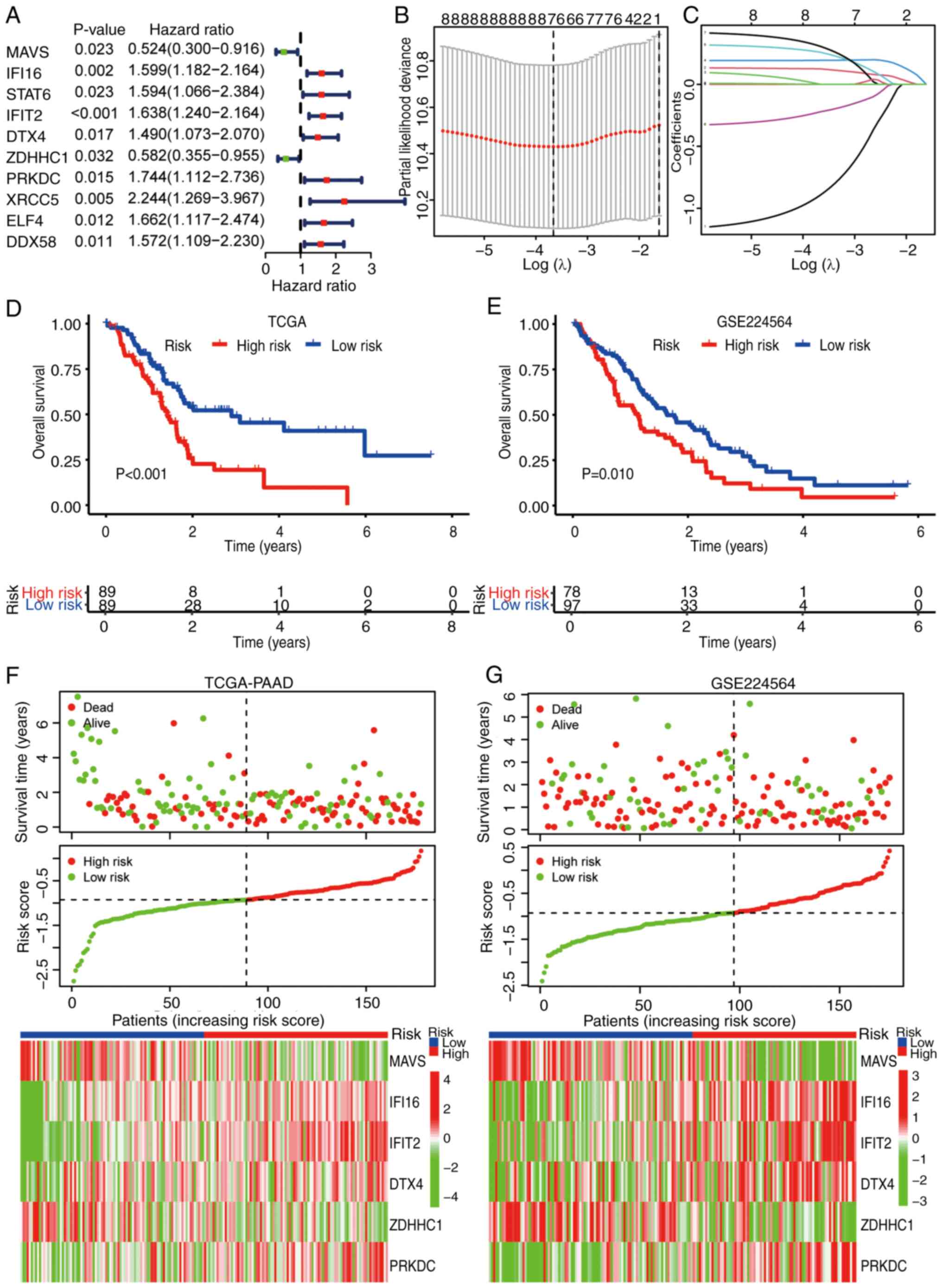

To elucidate the clinical significance of the STING

pathway in PAAD, its expression profile and prognostic relevance

were systematically analyzed. Analysis of the Curated Cancer Cell

Atlas revealed predominant STING expression within tumor cells,

macrophages, T cells and endothelial cells of the PAAD TME

(Fig. 1A) (The Cancer Genome Atlas

PAAD cohort; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-PAAD).

Utilizing GEPIA2, significantly elevated STING expression was

identified in PAAD compared with normal tissue (Fig. 1B), which was associated with a poor

patient prognosis (Fig. 1C) and

with progressively with advancing clinical stage (22) (Fig.

1D). Genomic analysis demonstrated that STING alterations in

PAAD primarily involved gene amplification (Fig. 1E). Immunohistochemical validation

via The Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org) confirmed stronger STING

protein staining in PAAD tissues compared with that in normal

pancreatic ductal epithelium, with STING predominantly localized

within cancer nests (Fig. 1F)

Collectively, these findings established STING as an adverse

prognostic factor in PAAD.

| Figure 1.Role of STING expression in PAAD. (A)

Heatmap comparing STING and immune-related gene expression profiles

in PAAD tumor microenvironment vs. adjacent normal tissue. (B) Box

plot demonstrating significantly elevated STING mRNA expression in

PAAD tumors (T) vs. normal pancreatic tissues (N) (*P<0.05)

(TCGA-PAAD (T) + Genotype-Tissue Expression; normal controls;

http://gtexportal.org). (C) Kaplan-Meier curves

comparing overall survival between PAAD patients with low vs. high

STING expression (log-rank test). (D) Violin plots showing STING

expression distribution across AJCC stages (I–IV) of PAAD. (E)

Oncoprint of STING genomic alterations (mutations, copy number

changes) in PAAD. (F) Human Protein Atlas representative

immunohistochemistry images of STING protein expression (PAAD

tissue; proteinatlas.org). Scale bar, 100 µm. STING, stimulator of

interferon genes; PAAD, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PAAD,

pancreatic adenocarcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NK, natural

killer; HR, hazard ratio; T, tumor; N, normal; TPM, transcripts per

million. |

Molecular subtyping of PAAD based on

STING pathway genes

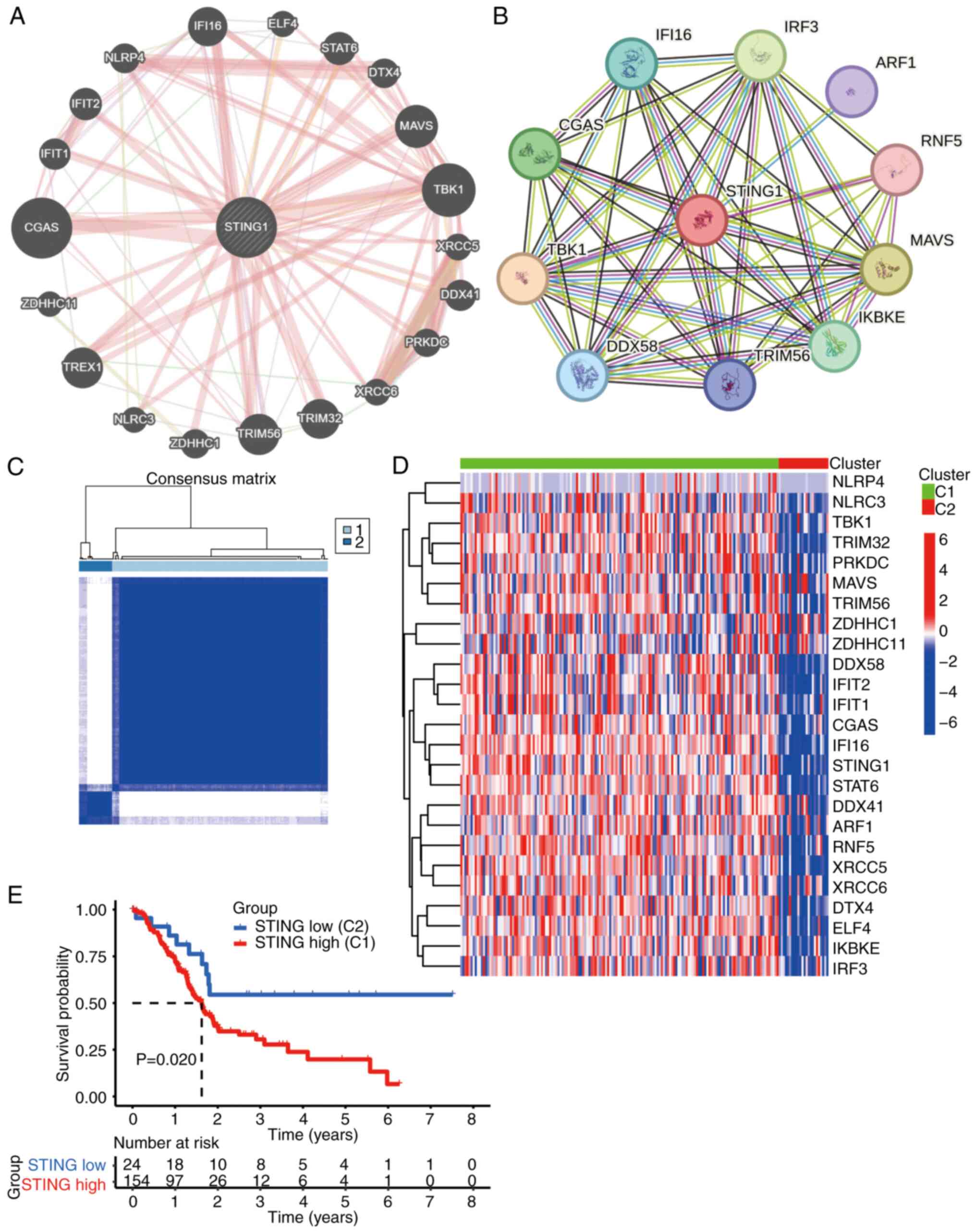

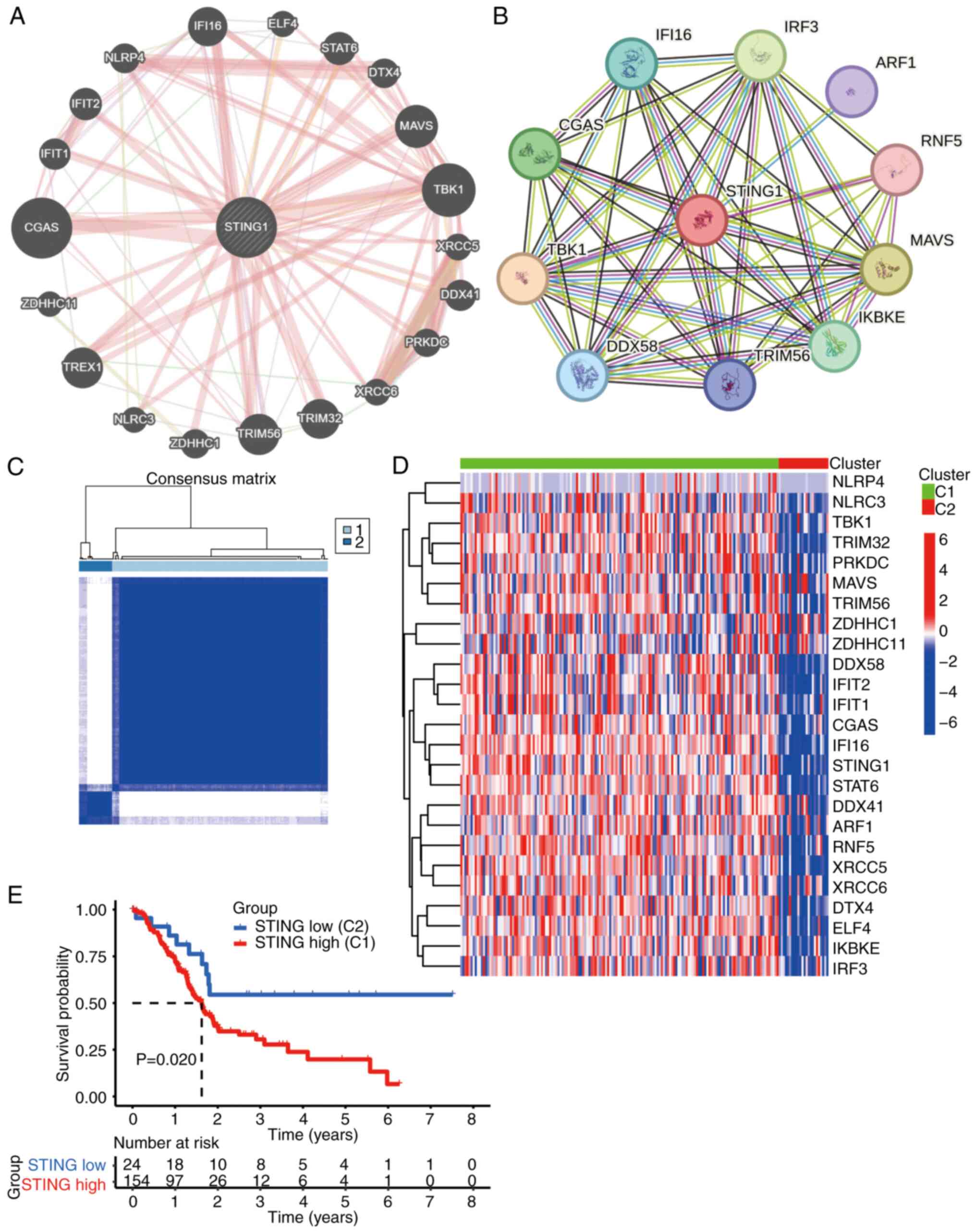

Given the prognostic relevance of STING, its core

signaling network was characterized to define molecular subtypes.

Protein-protein interaction analysis (performed using STRING

database v12.0; cn.string-db.org) identified 26 STING signaling

pathway-associated genes (Pearson r>0.6; all correlations

significant at P<0.001 after Benjamini-Hochberg correction)

(Fig. 2A and B). Unsupervised

clustering based on the expression profiles of these genes

stratified patients with PAAD (TCGA cohort) into two distinct

molecular subtypes: Cluster 1 (C1, STING-high) and Cluster 2 (C2,

STING-low) (Fig. 2C). Genes within

the STING pathway were significantly upregulated in the C1 subtype

(Fig. 2D). Survival analysis

confirmed that patients with the C1 subtype exhibited significantly

worse overall survival (Fig.

2E).

| Figure 2.Molecular characterization of STING

signaling pathway-related genes in PAAD. (A) Protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network of core STING signaling components

identified through STRING database analysis (minimum interaction

score: 0.4). (B) Expanded PPI network showing secondary interactors

of STING pathway genes (minimum interaction score: 0.7). (C)

Consensus matrix heatmap classifying patients with PAAD into two

molecular subtypes (C1 and C2) based on STING-related gene

expression patterns. (D) Heatmap comparing expression profiles of

STING-related genes across PAAD subtypes (C1 vs. C2) with

expression gradient key (red, high expression; blue, low

expression). (E) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing

significantly reduced overall survival in the STING-enriched

subtype (C1) compared with the STING-depleted subtype (C2). STING,

stimulator of interferon genes; PAAD, pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma; CGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; TBK1, TANK-binding

kinase 1; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; TRIM56,

tripartite motif-containing 56; TREX1, three prime repair

exonuclease 1; TRIM32, tripartite motif-containing 32; IFI16,

interferon γ inducible protein 16; IFIT1, interferon-induced

protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1; DDX41, DEAD-box helicase

41; NLRP4, NLR family pyrin domain containing 4; DTX4, deltex E3

ubiquitin ligase 4; ZDHHC1, zinc finger DHHC-type containing 1;

PRKDC, protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic subunit; XRCC, X-ray

repair cross complementing; ELF4, E74-like ETS transcription factor

4; NLRC3, NLR family CARD domain containing 3; ARF1, ARF GTPase 1;

DDX56, RNA sensor RIG-I; IKBKE, inhibitor of nuclear factor κB

kinase subunit ε; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3; RNF5, ring

finger protein 5. |

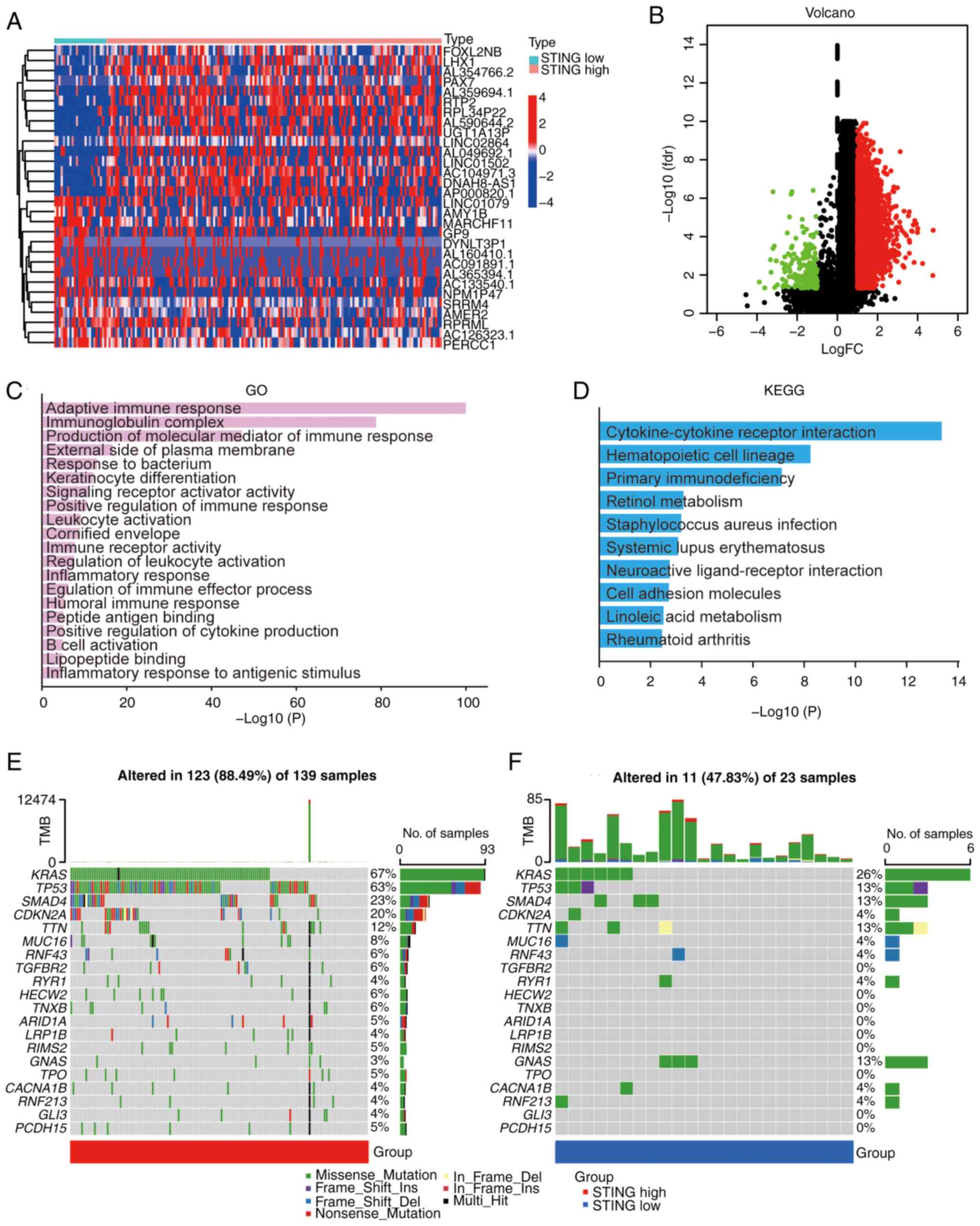

Genomic and immune landscape of

STING-defined subtypes

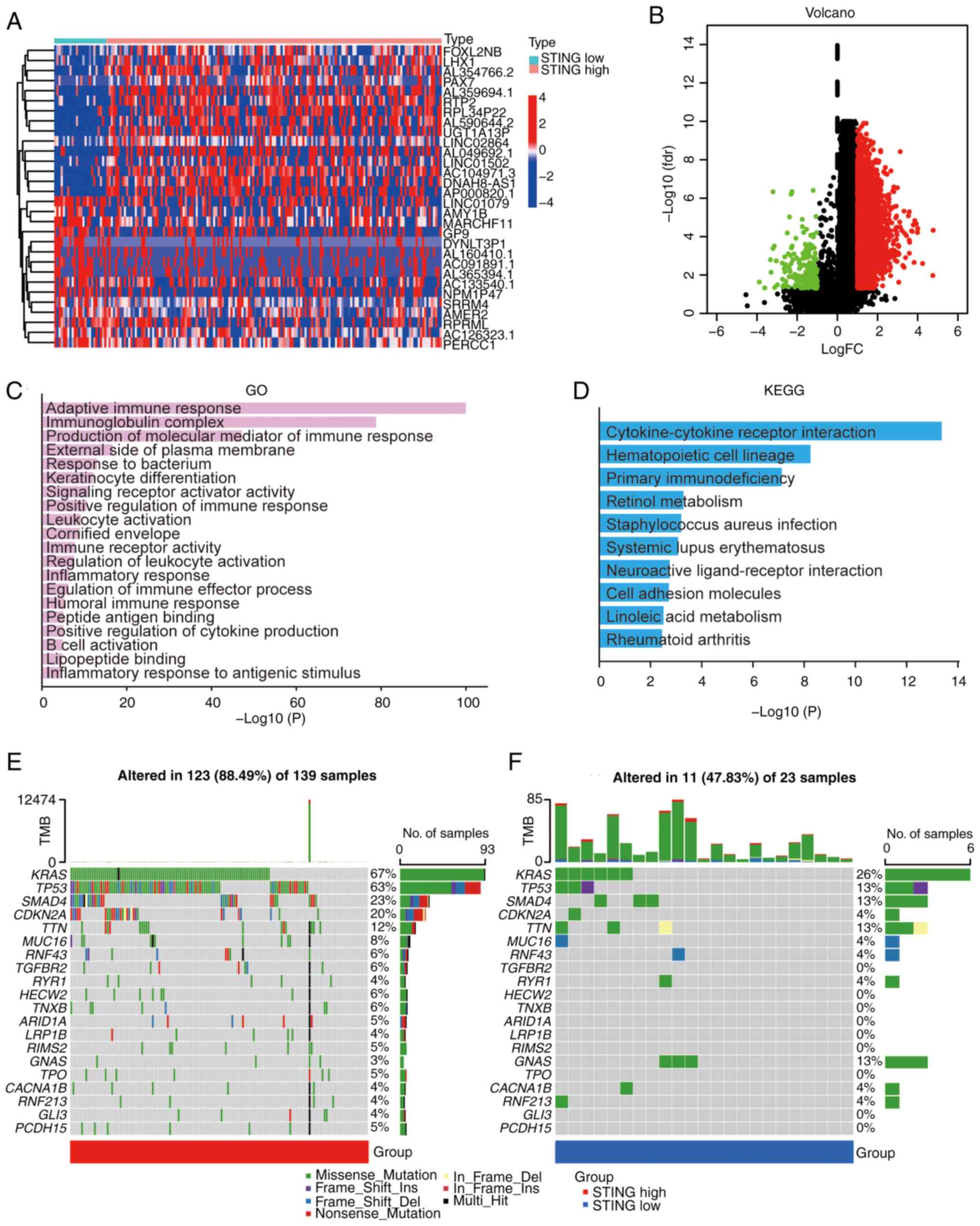

Differential gene expression analysis between C1 and

C2 subtypes revealed distinct transcriptional profiles (Fig. 3A and B). Gene Ontology (GO)

enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes highlighted

associations with ‘adaptive immune response’, ‘immunoglobulin

complex’ and ‘production of molecular mediator of immune response’

(Fig. 3C). Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis implicated

‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’, ‘hematopoietic cell

lineage’ and ‘primary immunodeficiency’ (Fig. 3D). Mutation profiling demonstrated

significantly higher tumor mutational burden in the C1 subtype

compared with that in the C2 subtype, characterized by frequent

mutations in key oncogenes (GTPase KRas, TP53-binding protein 1,

mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4, tumor suppressor ARF and

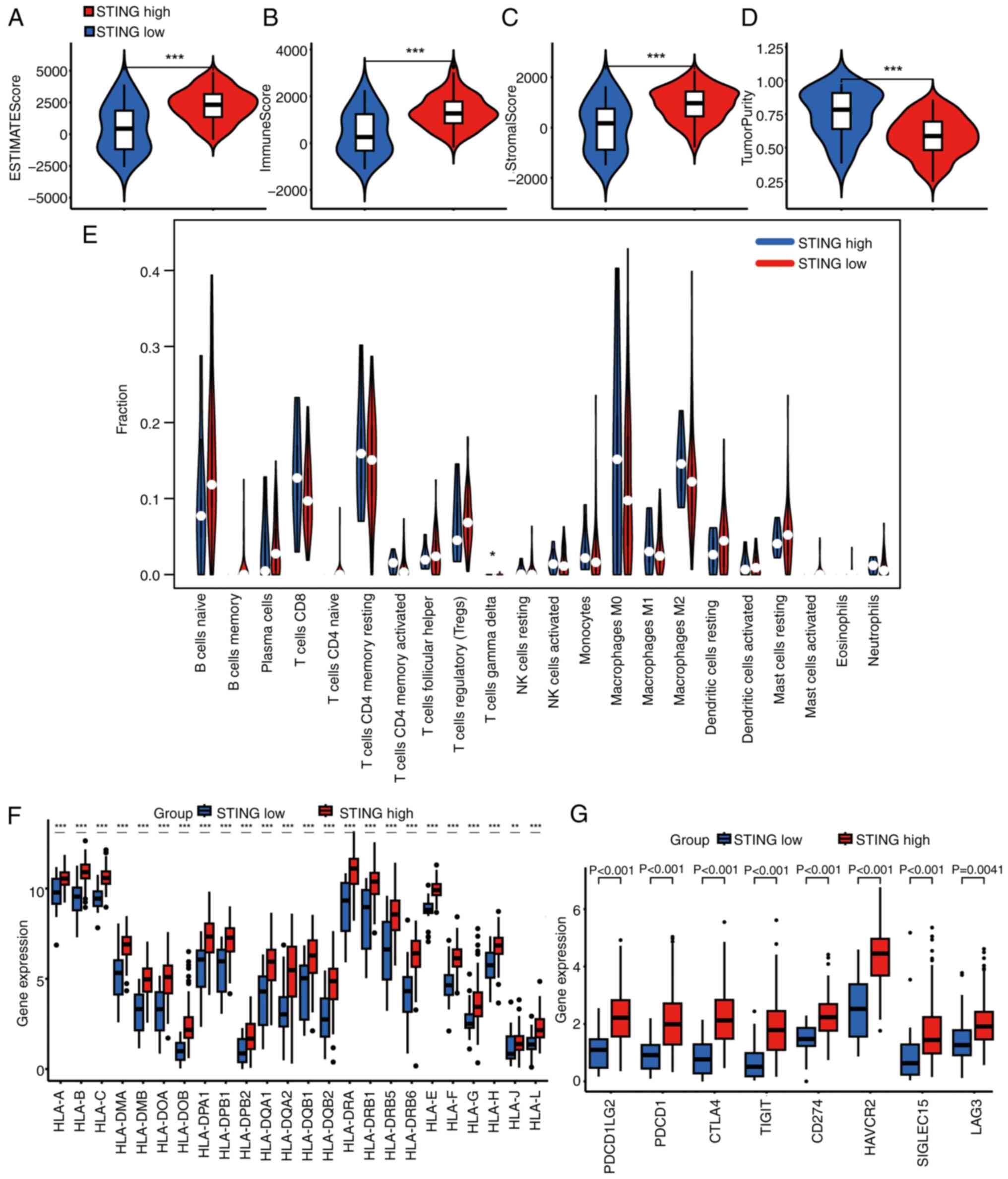

titin) (Fig. 3E and F). Evaluation

of TME composition using ESTIMATE revealed significantly higher

immune and stromal scores and lower tumor purity in C1 vs. C2

(Fig. 4A-D). CIBERSORTx

deconvolution further indicated elevated infiltration of T cells γ

δ in the C1 subtype (Fig. 4E).

Consistent with enhanced immunogenicity, C1 exhibited significantly

higher expression of human leukocyte antigen family genes and

immune checkpoint molecules relative to C2 (Fig. 4F and G).

| Figure 3.Gene characteristics of different

PAAD subtypes. (A) Heatmap of upregulated genes in STING1-enriched

subtype (C1) vs. STING1-depleted subtype (C2). (B) Heatmap of

downregulated genes in STING1-enriched subtype (C1) vs.

STING1-depleted subtype (C2). (red, high expression; blue, low

expression). (C) GO enrichment analysis showing top biological

processes in STING1-enriched subtype. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis showing top signaling pathways in STING1-enriched subtype.

(E) Mutational landscape of STING1-enriched subtype (C1) showing

frequent mutations in KRAS, TP53 and CDKN2A. (F) Mutational

landscape of STING1-depleted subtype (C2) showing distinct mutation

profile with SMAD4 alterations. PAAD, pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; FC,

fold-change; fdr, false discovery rate; TMB, tumor mutational

burden; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes. |

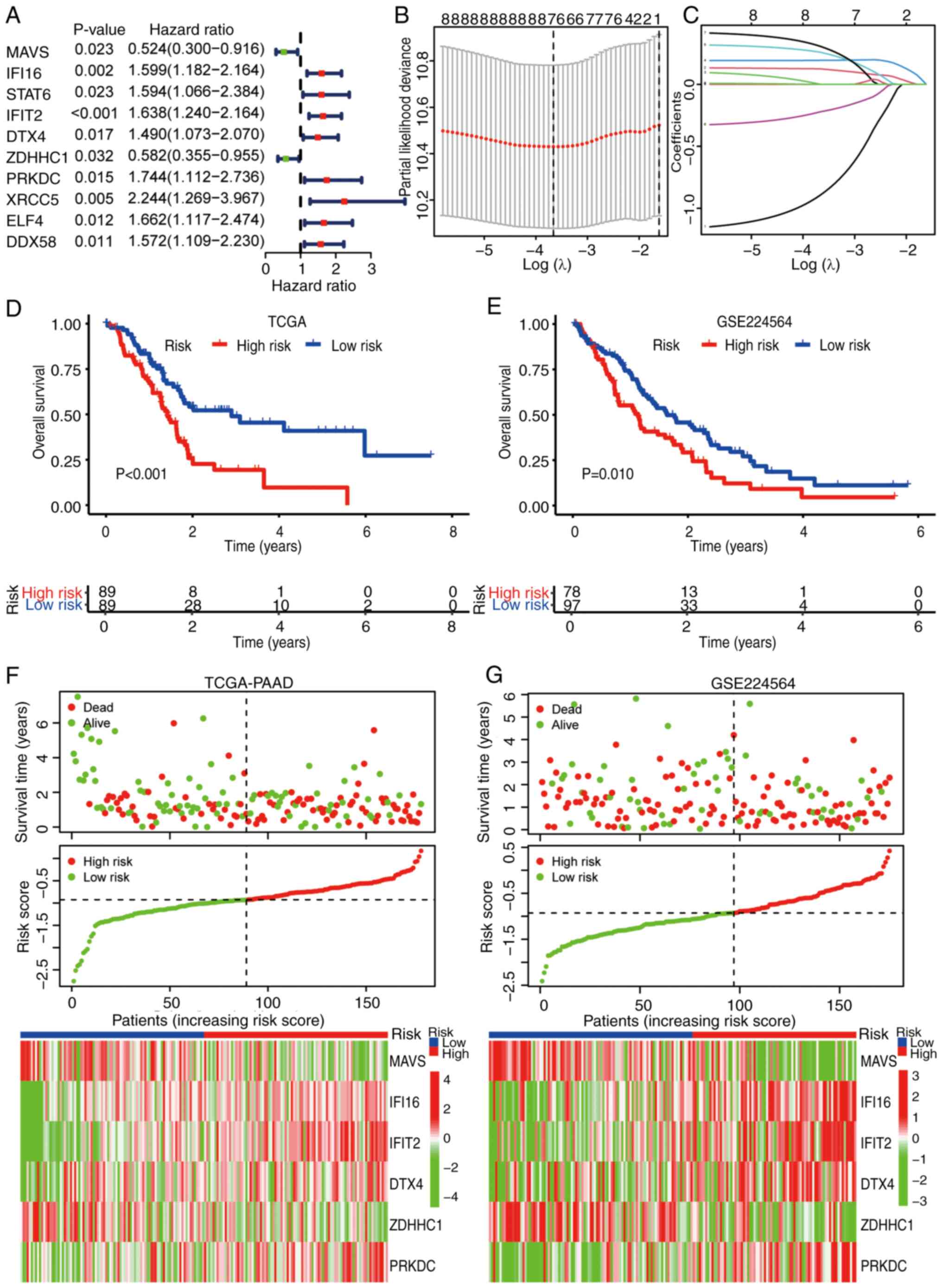

Development and validation of a STING

pathway prognostic signature

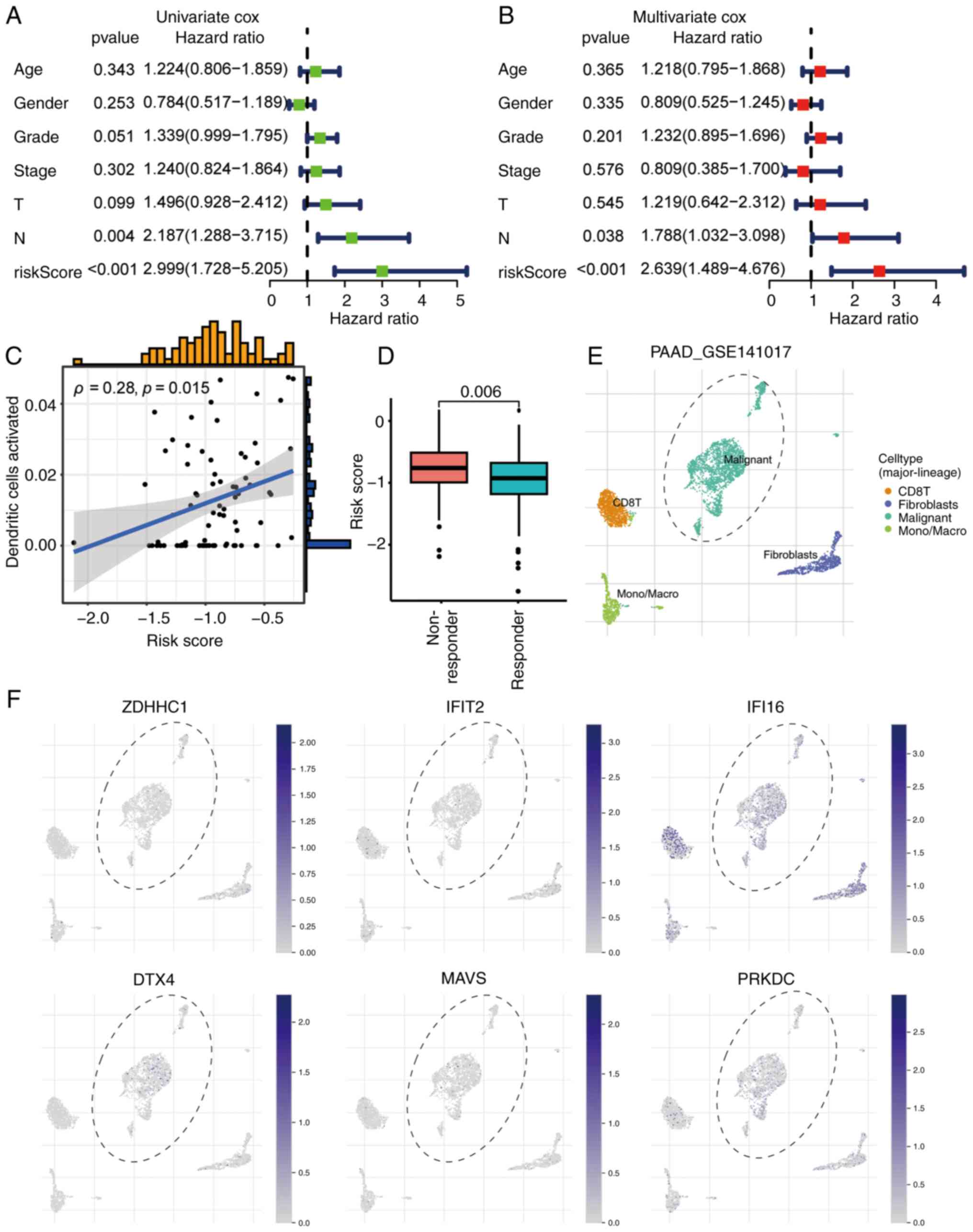

A risk prediction model was constructed to quantify

the prognostic heterogeneity associated with STING pathway

activity. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified 10 genes

among the 26 STING pathway genes that were significantly associated

with PAAD prognosis (Fig. 5A).

LASSO Cox regression refined these into a 6-gene prognostic

signature [deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 4, interferon γ inducible

protein 16, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS),

protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic subunit, ZDHHC1 and IFIT2]

(Fig. 5B and C). This signature

effectively stratified patients with PAAD into high- and low-risk

groups. Survival outcomes were significantly different in the TCGA

discovery cohort (Fig. 5D) and the

independent GSE224564 validation cohort (Fig. 5E). Expression patterns of the 6

signature genes were consistent across both TCGA (Fig. 5F) and validation cohort (Fig. 5G) datasets. Notably, multivariate

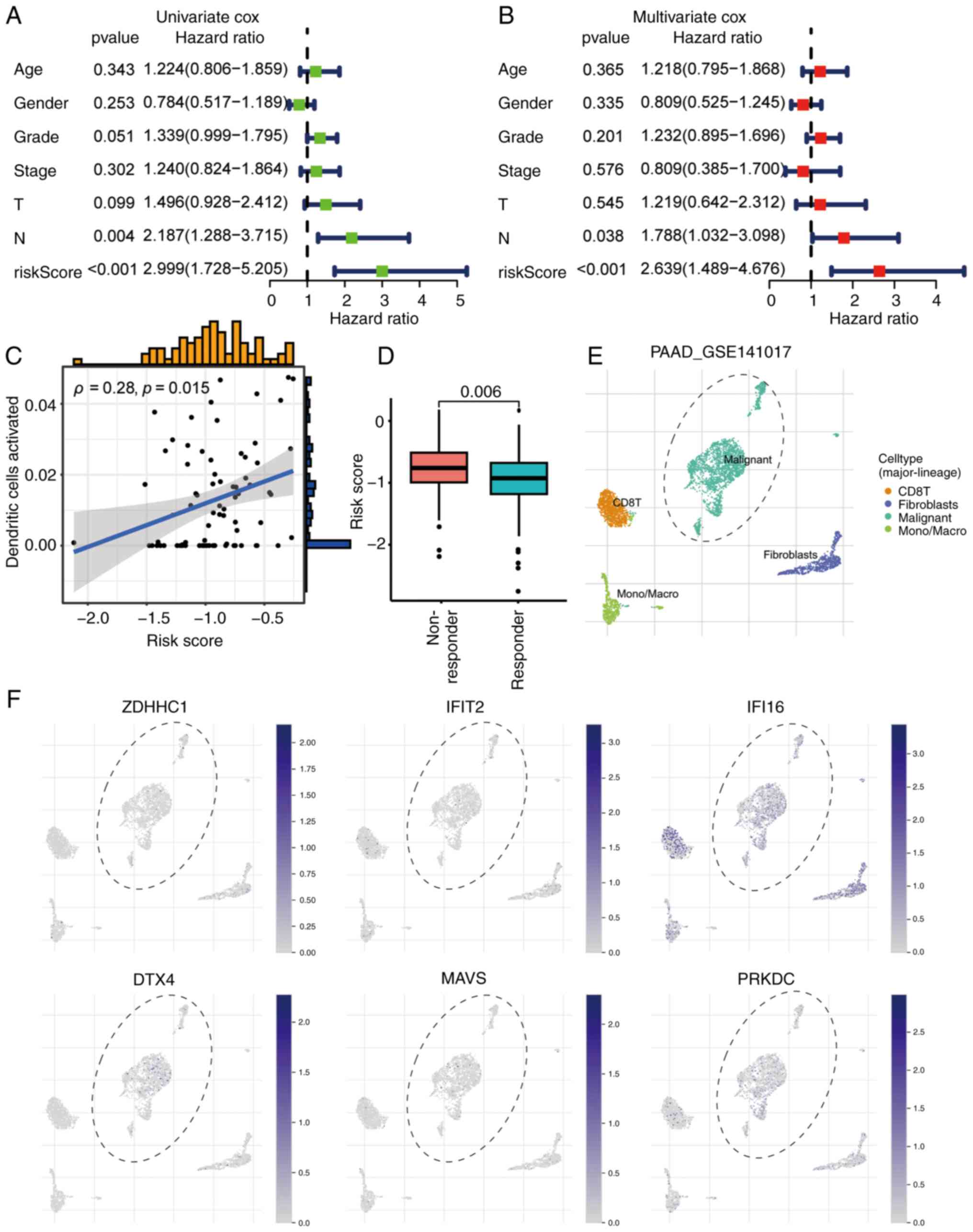

Cox regression analysis confirmed both the prognostic risk score

and N stage as independent predictors of survival in patients with

PAAD (Fig. 6A and B).

| Figure 5.Development and validation of a

STING1 signaling-related prognostic signature for PAAD. (A)

Univariate Cox regression analysis of STING1 pathway-related genes

in PAAD. Genes with significant prognostic value (P<0.05) are

included. (B) LASSO regression 10-fold cross-validation curve

showing optimal λ selection (minimum criteria). (C) LASSO

coefficient profiles of STING1-related genes across log(λ)

sequence. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for the prognostic

signature in TCGA-PAAD cohort (high-risk vs. low-risk groups;

cutoff: median risk score). (E) Validation of prognostic signature

in GSE224564 cohort. (F) Risk score distribution plot with

corresponding survival status and expression heatmap for 6

signature genes in TCGA-PAAD. (G) Validation in GSE224564 cohort

showing identical configuration to (F). STING, stimulator of

interferon genes; PAAD, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; LASSO,

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein;

IFI16, interferon γ inducible protein 16; IFIT2, interferon-induced

protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2; DTX4, deltex E3 ubiquitin

ligase 4; ZDHHC1, zinc finger DHHC-type containing 1; PRKDC,

protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic subunit; STAT6, signal

transducer and activator of transcription 6; XRCC5, X-ray repair

cross complementing: ELF4, E74-like ETS transcription factor 4;

DDX58, RNA sensor RIG-I. |

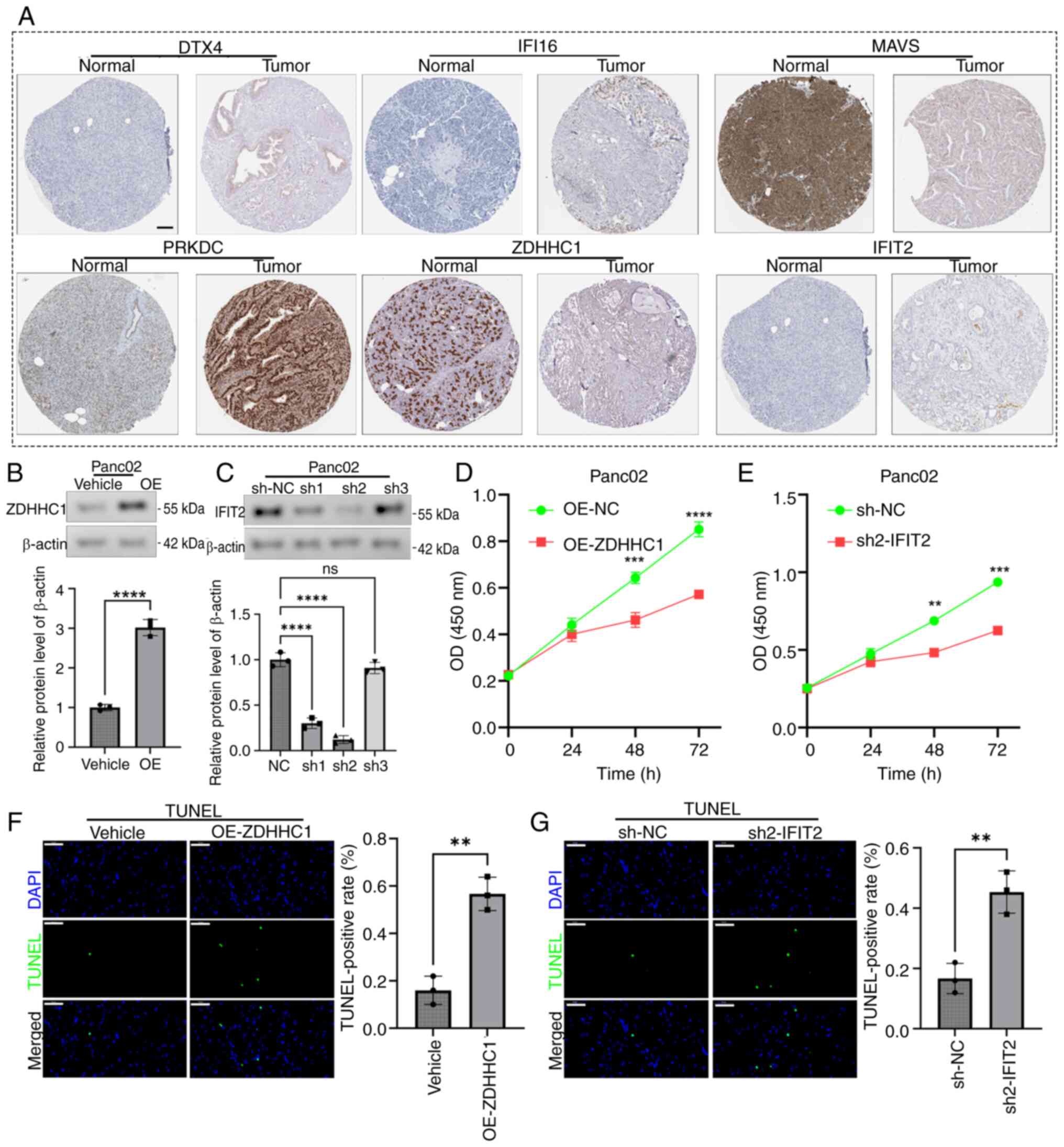

| Figure 6.Independent prognostic value and

immunotherapy relevance of the STING-related risk signature in

PAAD. (A) Univariate Cox regression analysis of clinical parameters

and risk score. (B) Multivariate Cox regression confirming the risk

score as an independent prognostic factor after adjusting for

covariates in (A). (C) Correlation analysis of risk score and

activated dendritic cell abundance. ‘Dendritic cells activated’

represents proportion scores derived from the xCell algorithm (0–1

scale), quantifying relative abundance in the tumor

microenvironment. Correlation was assessed using Spearman's rank

correlation analysis (Spearman's ρ=0.28; P=0.015). (D) Higher risk

scores in immunotherapy non-responders vs. responders (Mann-Whitney

U test). Single-cell RNA sequencing (GSE141017) visualization of

STING1 signature gene expression: (E) t-SNE plot showing cell-type

distribution. (F) Feature plots of signature gene expression across

the PAAD tumor microenvironment. STING, stimulator of interferon

genes; PAAD, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; T, tumor; N, node;

CD8T, T-cell surface glycoprotein CD8; ZDHHC1, zinc finger

DHHC-type containing 1; IFIT2, interferon-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats 2; IFI16, interferon γ inducible protein

16; DTX4, deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 4; MAVS, mitochondrial

antiviral-signaling protein; PRKDC, protein kinase DNA-activated

catalytic subunit; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma. |

Association of prognostic risk score

with immune features

The STING pathway-derived prognostic risk score

demonstrated significant biological relevance, showing a positive

correlation with DC activation as determined by Spearman's rank

correlation analysis (Fig. 6C).

Assessment using the TIDE algorithm revealed significantly higher

scores in high-risk vs. low-risk patients, indicating greater

immune evasion potential and reduced likelihood of response to

immune checkpoint blockade (Fig.

6D). Analysis of spatial expression (GSE141017) confirmed that

the 6 signature genes were predominantly expressed within tumor

cells of the PAAD TME (Fig. 6E and

F).

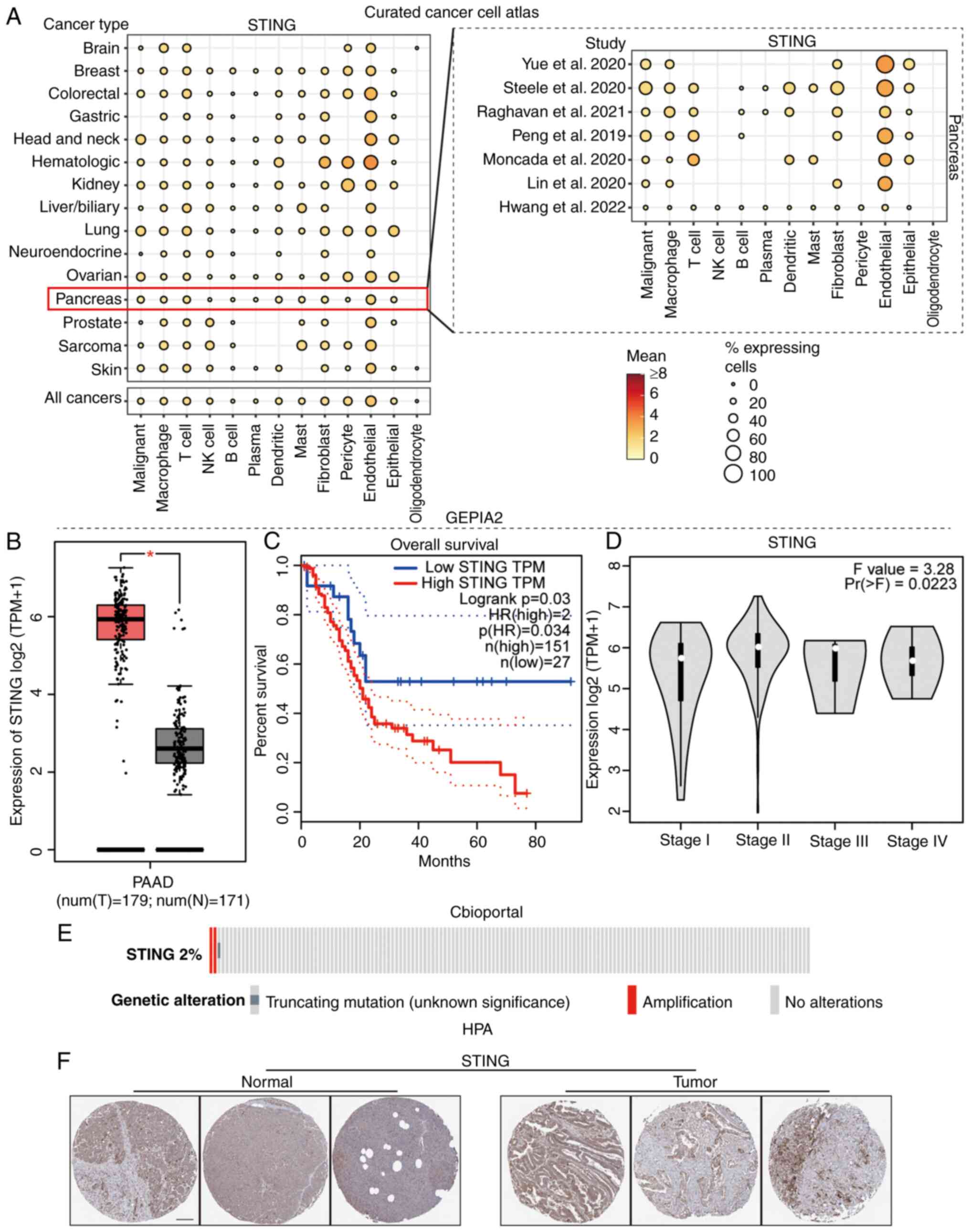

Functional validation of hub genes

IFIT2 and ZDHHC1

Given the established prognostic relevance of STING

in PAAD (characterized by high expression correlating with poor

patient outcomes in the present study), its core signaling network

was characterized to define molecular subtypes. While MAVS

demonstrated strong prognostic associations, its functional role in

PAAD has been extensively explored in prior literature (23). By contrast, ZDHHC1 and IFIT2, which

also showed significant prognostic value (Fig. S1), have received considerably less

attention in PAAD research. These genes were therefore prioritized

for validation, observing distinct expression dynamics: IFIT2

expression significantly increased with advancing AJCC 8th edition

tumor grade/stage (22) up to stage

III/grade 3 before declining in advanced disease, associated with a

poor prognosis, while ZDHHC1 expression decreased progressively

with tumor progression and was associated with favorable outcomes

(Fig. S1A-E). Immunohistochemical

validation using The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org) confirmed these protein

patterns in PAAD tissues (Fig. 7A).

Overexpression of ZDHHC1 was confirmed in the Panc-02 cells line

(Fig. 7B). Based on the confirmed

superior knockdown efficiency of sh2, the stable cell line

expressing sh2 was selected for all subsequent functional

experiments (Fig. 7C). Functional

studies in Panc02 cells revealed that overexpression of ZDHHC1

inhibited proliferation (Fig. 7D),

as did knockdown of IFIT2 (Fig.

7E). Overexpression of ZDHHC1 (Fig.

7F) and knockdown of IFIT2 (Fig.

7G) both promoted apoptosis. These results established IFIT2 as

a potential oncogene and ZDHHC1 as a potential tumor suppressor

within the STING pathway in PAAD.

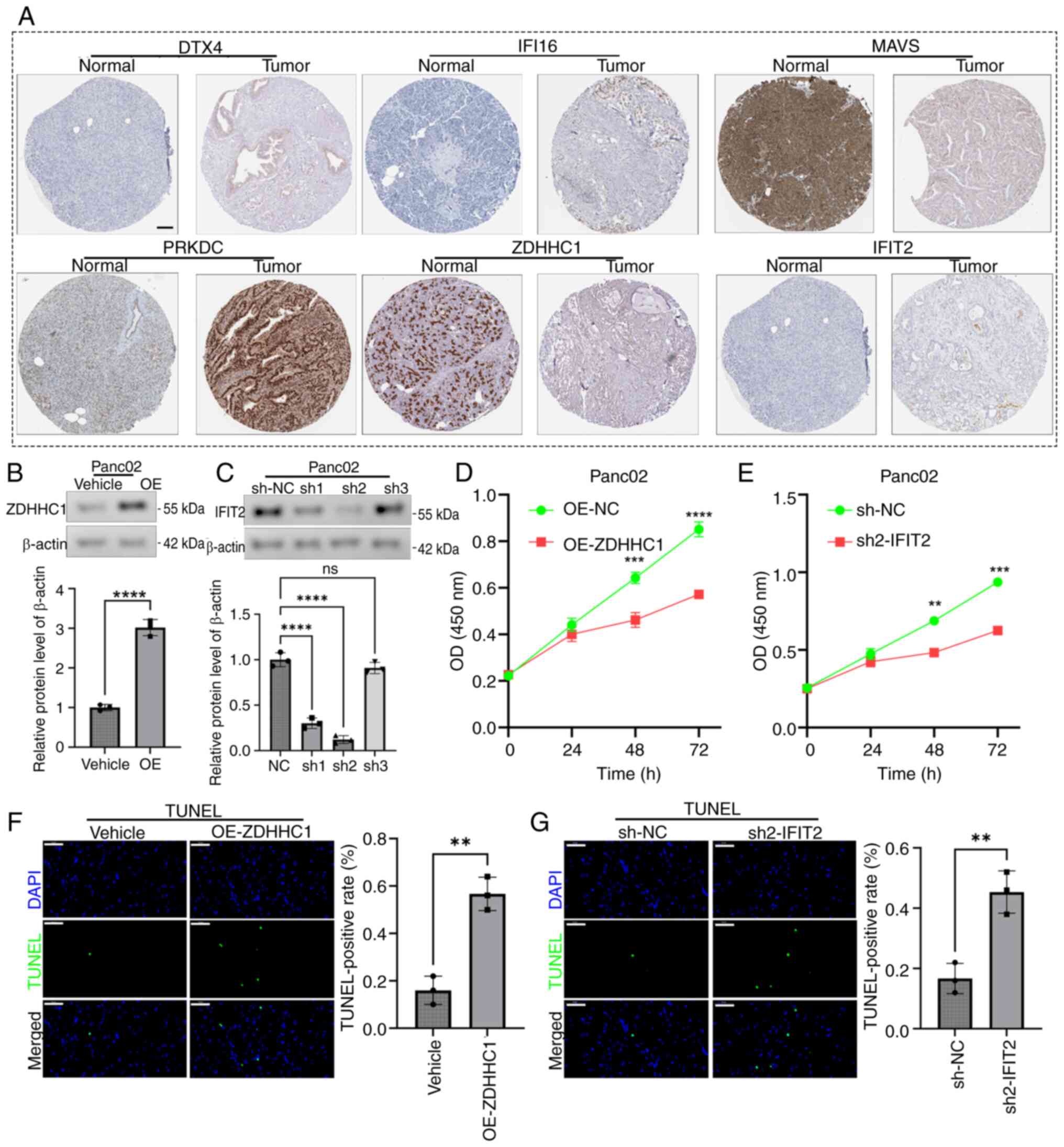

| Figure 7.Functional roles of IFIT2 and ZDHHC1

in PAAD oncobiology. (A) Human Protein Atlas representative

immunohistochemical staining of six prognostic signature genes in

PAAD tissues (proteinatlas.org). Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Western

blot and semi-quantification confirming successful ZDHHC1

overexpression in Panc02 cells (C) Western blot and

semi-quantification confirming IFIT2 knockout efficiency in Panc02

cells (****P<0.0001). (D) CCK-8 assay: ZDHHC1 overexpression

enhances Panc02 proliferation (***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs

OE-NC). (E) CCK-8 assay: IFIT2 knockout enhances Panc02

proliferation (**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. sh-NC). (F) TUNEL

assay (scale bar, 50 µm) demonstrating reduced apoptosis in

ZDHHC1-overexpressing Panc02 cells. (G) TUNEL assay (scale bar 50

µm) showing decreased apoptosis in IFIT2-knockout Panc02 cells

(**P<0.01). IFIT2, interferon-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats 2; ZDHHC1, zinc finger DHHC-type

containing 1; PAAD, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; OE,

overexpression; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; DTX4, deltex E3

ubiquitin ligase 4; IFI16, interferon γ inducible protein 16; MAVS,

mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; PRKDC, protein kinase

DNA-activated catalytic subunit; sh-NC, scrambled negative control

shRNA; ns, not significant. |

Discussion

PAAD presents a notable global health challenge,

ranking 12th in global cancer incidence but 7th in cancer-related

mortality rate according to 2020 data (24), with similar trends observed in China

(25). Bioinformatics has emerged

as a powerful tool for dissecting PAAD pathogenesis (26), enabling the identification of

potential biomarkers, therapeutic targets and immune evasion

mechanisms through the integrated analysis of genomic,

transcriptomic and tumor microenvironmental data (27).

Research into the STING signaling pathway in PAAD

reveals its complex duality. While STING agonists activate the

cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-STING pathway to induce IFN-I, trigger

adaptive immunity and exert cytotoxic effects on tumor cells

(11), clinical translation has

been hampered by intrinsic resistance mechanisms (28). These include STING-induced expansion

of regulatory B cells that suppress natural killer cell activity

(29) and the potential for chronic

pathway activation to promote immunosuppressive signaling

downstream of chromosomal instability (30). Nevertheless, STING agonism

demonstrates significant preclinical promise as it remodels the

PAAD tumor stroma and immune landscape, enhances cytotoxic T cell

infiltration while reducing the frequency of regulatory T cells

(31), activates DCs and reprograms

macrophages towards an immunostimulatory phenotype (32). Furthermore, synergistic strategies,

such as combining STING agonists with interleukin-35 blockade, show

enhanced antitumor efficacy (29).

Future progress may hinge on developing novel agonists (for

example, non-nucleotide compounds) and targeted delivery systems to

improve efficacy and minimize toxicity.

The present study provides novel insights into the

immune-related functions of STING and its associated genes within

the distinct context of PAAD. Notably, high expression of STING

pathway genes was identified to be associated with a poor prognosis

in PAAD. This association contrasts with observations in some other

cancer types (such as gastric cancer, colorectal cancer and

hepatocellular carcinoma) and potentially reflects the unique

immunobiology of the ‘cold’ nature of PAAD tumors. Using this, a

robust prognostic signature centered on STING pathway activity was

developed. Further functional prioritization within this signature

highlighted the notable, yet opposing, roles of IFIT2 and

ZDHHC1.

In the present study, IFIT2 emerged as a potential

oncogenic driver in PAAD. Elevated IFIT2 expression was associated

with advanced tumor grade/stage (22) and worse survival outcomes. This

association aligns with studies linking IFIT2 to chemotherapy

resistance in PAAD and its established role in regulating

inflammatory responses downstream of IFN signaling and pathogen

recognition (33). IFIT2 may

modulate the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME); evidence in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma shows that

methyltransferase-like protein 3-mediated neuronal membrane

glycoprotein M6-a modification regulates IFIT2, influencing

malignant progression and the TIME (34). While prognostic in oral squamous

cell carcinoma, the specific pro-tumorigenic mechanisms of IFIT2 in

PAAD warrant further investigation. Conversely, in the present

study, ZDHHC1 functioned as a putative tumor suppressor. ZDHHC1 is

frequently epigenetically silenced via promoter methylation across

various cancer types, such as gastric cancer, colorectal cancer and

hepatocellular carcinoma. Restoring ZDHHC1 expression exerts broad

antitumor effects, including the induction of apoptosis and

autophagy, cell cycle arrest, the inhibition of

migration/metastasis, the reversal of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and stemness (35), and

metabolic reprogramming via suppression of glycolysis and the

pentose phosphate pathway (36).

Mechanistically, ZDHHC1 acts as an S-palmitoyltransferase critical

for palmitoylating p53 at residues C135, C176 and C275, thereby

stabilizing and activating the master tumor suppressor activity of

p53 (37). Loss of ZDHHC1-mediated

p53 palmitoylation represents a novel evasion mechanism in cancer.

Although the role of ZDHHC1 in PAAD was previously undefined, the

present data positions ZDHHC1 as a compelling therapeutic target

meriting further exploration in PAAD.

While providing valuable mechanistic and prognostic

insights into STING signaling in PAAD, the present study has

several limitations: i) The reliance on protein-protein interaction

networks for gene selection may have excluded key epigenomic

regulators or microenvironmental modulators, limiting pathway

comprehensiveness; ii) despite internal-external validation (TCGA +

GSE224564, n=353), cohort size constraints limit statistical power

for detailed subtype-specific analyses and robust assessment of

treatment interactions; iii) while in vitro validation

confirmed IFIT2/ZDHHC1 functionality in Panc02 cells, the present

study lacked in vivo models to evaluate stromal crosstalk,

combinatorial gene perturbation assays to assess IFIT2-ZDHHC1

interplay and spatial resolution of immune effects (for example,

multiplexed T-cell infiltration mapping); iv) clinical translation

requires standardized detection protocols for biopsy specimens and

prospective trials stratifying immunotherapy based on risk scores;

and v) the cellular origin (cancer vs. immune) and temporal

dynamics of STING pathway gene expression during progression remain

unresolved. Future research should prioritize multi-center

signature validation, developing CRISPR-engineered dual-gene models

(IFIT2 knockout + ZDHHC1 overexpression) for in vivo

efficacy testing, employing spatial multi-omics (single cell RNA

sequencing and spatial proteomics) to resolve compartment-specific

expression and conducting STING agonist trials within

signature-defined patient subgroups.

In summary, the present study established and

validated a STING signaling pathway-derived prognostic gene

signature that effectively stratifies patients with PAAD. High-risk

patients identified by this signature exhibited significantly

poorer survival outcomes compared with low-risk patients, and

distinct immune microenvironment profiles. Notably, the

antagonistic roles of two core signature genes were functionally

validated: IFIT2 as a potential oncogene promoting proliferation

and suppressing apoptosis, and ZDHHC1 as a putative tumor

suppressor with the converse effects. The findings of the present

study underscore the notable clinical and biological relevance of

the STING pathway in PAAD. The identified genes, particularly IFIT2

and ZDHHC1, represent promising candidates for further mechanistic

exploration and potential targets for developing novel therapeutic

strategies against this lethal malignancy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WY and JLia contributed to the conceptualization,

reviewing and editing of the manuscript. JLi was responsible for

the curation of the data. YW provided the formal analysis and

supervision. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. JLi and YW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

PAAD

|

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

|

|

STING

|

stimulator of interferon genes

|

|

IFIT2

|

interferon-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats 2

|

|

ZDHHC1

|

zinc finger DHHC-type containing 1

|

|

LASSO

|

least absolute shrinkage and selection

operator

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

TIDE

|

Tumor Immune Dysfunction and

Exclusion

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Blackford AL, Canto MI, Dbouk M, Hruban

RH, Katona BW, Chak A, Brand RE, Syngal S, Farrell J, Kastrinos F,

et al: Pancreatic cancer surveillance and survival of high-risk

individuals. JAMA Oncol. 10:1087–1096. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Park W, Chawla A and O'Reilly EM:

Pancreatic cancer: A review. JAMA. 326:851–862. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Peduzzi G, Archibugi L, Farinella R, de

Leon Pisani RP, Vodickova L, Vodicka P, Kraja B, Sainz J,

Bars-Cortina D, Daniel N, et al: The exposome and pancreatic

cancer, lifestyle and environmental risk factors for PDAC. Semin

Cancer Biol. 113:100–129. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Springfeld C, Ferrone CR, Katz MHG, Philip

PA, Hong TS, Hackert T, Büchler MW and Neoptolemos J: Neoadjuvant

therapy for pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:318–337.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hu ZI and O'Reilly EM: Therapeutic

developments in pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

21:7–24. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sang W, Zhou Y, Chen H, Yu C, Dai L, Liu

Z, Chen L, Fang Y, Ma P, Wu X, et al: Receptor-interacting protein

kinase 2 is an immunotherapy target in pancreatic cancer. Cancer

Discov. 14:326–347. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ullman NA, Burchard PR, Dunne RF and

Linehan DC: Immunologic strategies in pancreatic cancer: Making

cold tumors hot. J Clin Oncol. 40:2789–2805. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhao K, Huang J, Zhao Y, Wang S, Xu J and

Yin K: Targeting STING in cancer: Challenges and emerging

opportunities. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1889832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang B, Xu P and Ablasser A: Regulation

of the cGAS-STING pathway. Annu Rev Immunol. 43:667–692. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tani T, Mathsyaraja H, Campisi M, Li ZH,

Haratani K, Fahey CG, Ota K, Mahadevan NR, Shi Y, Saito S, et al:

TREX1 inactivation unleashes cancer cell STING-interferon signaling

and promotes antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 14:752–765. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Luo J, Wang S, Yang Q, Fu Q, Zhu C, Li T,

Yang S, Zhao Y, Guo R, Ben X, et al: γδ T Cell-mediated tumor

immunity is tightly regulated by STING and TGF-β signaling

pathways. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24044322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu X, Hogg GD, Zuo C, Borcherding NC,

Baer JM, Lander VE, Kang LI, Knolhoff BL, Ahmad F, Osterhout RE, et

al: Context-dependent activation of STING-interferon signaling by

CD11b agonists enhances anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Cell.

41:1073–1090.e12. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tian X, Ai J, Tian X and Wei X: cGAS-STING

pathway agonists are promising vaccine adjuvants. Med Res Rev.

44:1768–1799. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen X, Xu Z, Li T, Thakur A, Wen Y, Zhang

K, Liu Y, Liang Q, Liu W, Qin JJ and Yan Y:

Nanomaterial-encapsulated STING agonists for immune modulation in

cancer therapy. Biomark Res. 12:22024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chin EN, Sulpizio A and Lairson LL:

Targeting STING to promote antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol.

33:189–203. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chen X, Meng F, Xu Y, Li T, Chen X and

Wang H: Chemically programmed STING-activating nano-liposomal

vesicles improve anticancer immunity. Nat Commun. 14:45842023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dosta P, Cryer AM, Dion MZ, Shiraishi T,

Langston SP, Lok D, Wang J, Harrison S, Hatten T, Ganno ML, et al:

Investigation of the enhanced antitumour potency of STING agonist

after conjugation to polymer nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol.

18:1351–1363. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wen Z, Sun F, Wang R, Wang W, Zhang H,

Yang F, Wang M, Wang Y and Li B: STING agonists: A range of eminent

mediators in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Signal. 134:1119142025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ohara Y, Tang W, Liu H, Yang S, Dorsey TH,

Cawley H, Moreno P, Chari R, Guest MR, Azizian A, et al:

SERPINB3-MYC axis induces the basal-like/squamous subtype and

enhances disease progression in pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep.

42:1134342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee M, Thomas AS, Lee SY, Cho YJ, Jung HS,

Yun WG, Han Y, Jang JY, Kluger MD and Kwon W: Reconsidering the

absence of extrapancreatic extension in T staging for pancreatic

adenocarcinoma in the AJCC (8th ed) staging manual using the

national cancer database. J Gastrointest Surg. 27:2484–2492. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kerschbaum-Gruber S, Kleinwächter A,

Popova K, Kneringer A, Appel LM, Stasny K, Röhrer A, Dias AB,

Benedum J, Walch L, et al: Cytosolic nucleic acid sensors and

interferon beta-1 activation drive radiation-induced anti-tumour

immune effects in human pancreatic cancer cells. Front Immunol.

15:12869422024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yin L, Wei J, Lu Z, Huang S, Gao H, Chen

J, Guo F, Tu M, Xiao B, Xi C, et al: Prevalence of germline

sequence variations among patients with pancreatic cancer in China.

JAMA Netw Open. 5:e21487212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Larson NB, Oberg AL, Adjei AA and Wang L:

A clinician's guide to bioinformatics for next-generation

sequencing. J Thorac Oncol. 18:143–157. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Petralia F, Ma W, Yaron TM, Caruso FP,

Tignor N, Wang JM, Charytonowicz D, Johnson JL, Huntsman EM, Marino

GB, et al: Pan-cancer proteogenomics characterization of tumor

immunity. Cell. 187:1255–1277.e27. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lv M, Chen M, Zhang R, Zhang W, Wang C,

Zhang Y, Wei X, Guan Y, Liu J, Feng K, et al: Manganese is critical

for antitumor immune responses via cGAS-STING and improves the

efficacy of clinical immunotherapy. Cell Res. 30:966–979. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li S, Mirlekar B, Johnson BM, Brickey WJ,

Wrobel JA, Yang N, Song D, Entwistle S, Tan X, Deng M, et al:

STING-induced regulatory B cells compromise NK function in cancer

immunity. Nature. 610:373–380. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li J, Hubisz MJ, Earlie EM, Duran MA, Hong

C, Varela AA, Lettera E, Deyell M, Tavora B, Havel JJ, et al:

Non-cell-autonomous cancer progression from chromosomal

instability. Nature. 620:1080–1088. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jneid B, Bochnakian A, Hoffmann C, Delisle

F, Djacoto E, Sirven P, Denizeau J, Sedlik C, Gerber-Ferder Y,

Fiore F, et al: Selective STING stimulation in dendritic cells

primes antitumor T cell responses. Sci Immunol. 8:eabn66122023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang J, Li S, Wang M, Wang X, Chen S, Sun

Z, Ren X, Huang G, Sumer BD, Yan N, et al: STING licensing of type

I dendritic cells potentiates antitumor immunity. Sci Immunol.

9:eadj39452024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yang Y, Song J, Zhao H, Zhang H and Guo M:

Patients with dermatomyositis shared partially similar

transcriptome signature with COVID-19 infection. Autoimmunity.

56:22209842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu QC, Tien YC, Shi YH, Chen S, Zhu YQ,

Huang XT, Huang CS, Zhao W and Yin XY: METTL3 promotes intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma progression by regulating IFIT2 expression in an

m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. Oncogene. 41:1622–1633.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhou B, Liu Y, Ma H, Zhang B, Lu B, Li S,

Liu T, Qi Y, Wang Y, Zhang M, et al: Zdhhc1 deficiency mitigates

foam cell formation and atherosclerosis by inhibiting PI3K-Akt-mTOR

signaling pathway through facilitating the nuclear translocation of

p110α. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1871:1675772025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Le X, Mu J, Peng W, Tang J, Xiang Q, Tian

S, Feng Y, He S, Qiu Z, Ren G, et al: DNA methylation downregulated

ZDHHC1 suppresses tumor growth by altering cellular metabolism and

inducing oxidative/ER stress-mediated apoptosis and pyroptosis.

Theranostics. 10:9495–9511. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tang J, Peng W, Feng Y, Le X, Wang K,

Xiang Q, Li L, Wang Y, Xu C, Mu J, et al: Cancer cells escape p53′s

tumor suppression through ablation of ZDHHC1-mediated p53

palmitoylation. Oncogene. 40:5416–5426. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|