Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) belongs to the human

γ-herpes virus, which infects ~90% of the human population.

Although the majority of EBV carriers have latent infection with no

significant clinical symptoms (1,2), EBV

infection can also drive human B cell proliferation and

transformation, triggering numerous neoplasm types and autoimmune

diseases, and a compromised immune system worsens the problem

(3). It has been reported that EBV

is associated with a variety of tumors, including Burkitt's

lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma [such as natural

killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma] (4)

and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (2,5),

suggesting that EBV may be a potential driving force for tumor

development. However, the mechanism behind this remains unclear,

and the development of anti-EBV targeting strategies remains

challenging (6,7).

EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), which

is a direct target gene of EBV nuclear antigen 2, has been reported

to be an oncogene (8) that plays a

major role in the regulation of tumor-related metabolism (9). LMP1 potentiates tumor growth through

activation of glycolysis (10),

mitochondrial function (11),

hypoxia-inducible factor 1 signaling (12), sterol regulatory element-binding

transcription factor 1 (SREBP1)-mediated lipogenesis (13) and programmed death-ligand 1

upregulation (14). Additionally,

LMP1 activates the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway

(15); NF-κB is then translocated

into the nucleus and subsequently activates related target genes

(16). It has been reported that

LMP1 promotes tumorigenesis through NF-κB-mediated peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1β (PGC1β)

upregulation (17). The PGC1

family, which includes PGC1α and PGC1β (18), plays an important role in

maintaining the balance of glucose and lipids involved in energy

metabolism through regulating various target genes as a

transcriptional coactivator (19).

Previous studies have reported that PGC1β expression triggers

tumorigenesis through mitochondrial metabolism, glycolysis and

redox balance (20–22). Our group has recently reported that

PGC1β promotes tumor growth via lactate dehydrogenase A

(LDHA)-mediated glycolysis (23) in

addition to SREBP1-mediated hexokinase domain component 1 (HKDC1)

upregulation, subsequently increasing mitochondrial metabolism

(24), although the detailed

mechanism for PGC1β-mediated tumorigenesis remains largely

unknown.

Our group has previously reported that LMP1 promotes

tumorigenesis through PGC1β upregulation (17), while numerous forms of lymphoma

exhibit upregulated PGC1β expression in the absence of EBV/LMP1.

The present study aimed to investigate the potential mechanism for

transient EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated persistent PGC1β activation

through epigenetic changes. The current in vitro findings

revealed that LMP1 knockdown in EBV-positive cells did not result

in a significant change in PGC1β expression or subsequent cell

proliferation.

In the present study, the potential mechanism for

PGC1β-mediated mitochondrial fission by upregulation of protein

dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) was evaluated (11). In addition, the potential reason why

transient exposure to either EBV or LMP1 causes persistent PGC1β

expression as well as the subsequent consequence of PGC1β

upregulation on tumor growth was investigated in both in

vitro and in vivo mouse model. The SNK6 cells were used

as tumor cell line to evaluate the potential effect on tumor growth

when the related genes were knocked down, while human primary

hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) were used to evaluate the potential

effect on tumorigenesis when the related genes were overexpressed.

Finally, the potential effects of EBV, LMP1 and PGC1 β on tumor

growth were evaluated through in vivo xenograft mouse model.

It was concluded that transient LMP1 expression caused persistent

PGC1β upregulation and tumor growth through epigenetic

modifications, thus elucidating the potential mechanism for

transient EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated tumorigenesis while explaining

why numerous forms of lymphoma show absence of EBV/LMP1.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

Human HSC were isolated from healthy peripheral

blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) cells using EasySep™ Human

Progenitor Cell Enrichment kit with Platelet Depletion (cat. no.

19356), while human NK cells were isolated from healthy PBMC cells

using EasySep™ Human NK Cell Isolation kit (Stemcell Technologies,

Inc.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. A number of

PBMCs, NK cells or isolated healthy HSC were conditionally

immortalized using hTERT lentivirus vector with an extended life

span to achieve a higher transfection efficiency and experimental

stability (25,26). Tumor cell lines, including B95-8,

Namalwa, HANK1, SNT8 and SNK6, were purchased from American Type

Culture Collection. The B95-8 cell line was used for EBV viral

production and subsequent concentration for the infection of HSC,

PBMCs or NK cells according to a previously described protocol

(27). The EBV LMP1 adenovirus for

LMP1 transient infection and related empty adenovirus control were

kindly provided by Dr Haimou Zhang (Hubei University, China).

Antibodies against CdxA (Cdx1; cat. no. sc-515146), Ets1 (c-Ets;

cat. no. sc-55581), forkhead box D3 (HFH2; cat. no. sc-517206),

GA-binding protein α (GABPα; cat. no. sc-28312), GATA1 (cat. no.

sc-265), GATA2 (cat. no. sc-267), Ki-67 (cat. no. sc-101861),

nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1; cat. no. sc-101102), NF-κB p65

(cat. no. sc-398442) and organic cation transporter 1 (Oct1; cat.

no. sc-8024) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Antibodies against DRP1 (cat. no. ab140494), optic atrophy 1 (OPA1;

cat. no. ab157457), mitofusin 2 (MFN2; cat. no. ab56889) and PGC1β

(cat. no. ab240188) were obtained from Abcam. Antibodies against

EBV LMP1 (cat. no. NBP1-79009) and 8-oxo-deoxyguanosine (dG) (cat.

no. 4354-MC-050) were obtained from Novus Biologicals, Ltd. The

small interfering RNA (siRNA) for GABPα and NRF1, and scrambled

control siRNA were purchased from Ambion (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), and the target sequences of siRNA were provided in Table SI. The expanded section of

Materials and methods is available in Appendix S1.

Preparation of DRP1 reporter

constructs

The DRP1 gene promoter (2 kb upstream) from Ensembl

gene ID: DNM1L-201 ENST00000266481.10 (for DRP1) (with the

following link: http://uswest.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Transcript/Summary?db=core;g=ENSG00000087470;r=12:32679303-32744350;t=ENST00000266481),

was amplified by PCR from SNK6 genomic DNA, and then subcloned into

the pGL3-basic vector (cat. no. E1751; Promega Corporation) by

using the following primers with restriction sites for MluI

and XhoI, respectively: DRP1 forward, 5′-gcgc-acgcgt-agt tgg

ggc cac agg tat gca-3′ (MluI) and reverse,

5′-atcg-ctcgag-aca gtt cgc ctc ctt cct cct-3′ (XhoI).

Preparation of gene knockdown

lentivirus

The shRNA lentivirus particles for human PGC1β,

human NFκB-p65, EBV LMP1 and non-target control were designed and

purchased from MilliporeSigma, and all the shRNA target sequences

were provided in Table SI. These

lentiviruses were used for infection of tumor cell lines (e.g.

SNK6). The treated cells were cultured in the presence of 10 µg/ml

puromycin, and the gene knockdown efficiency was evaluated by

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) based on an mRNA

decrease of >65% compared with that in the control group. The

primer sequences are shown in Table

SII (23,24).

Immunostaining

Treated SNK6 cells were transferred to coated cover

slips, and then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, incubated with 1% BSA

and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h, and blotted with 40 µg/ml primary

antibody against PGC1β, Ki-67 or 8-oxo-dG for 4 h. In

triple-staining experiments, the live cells were stained with

MitoTracker™ Green FM before fixation. After thorough washing, the

cells were incubated with either FITC or Texas Red-labeled

secondary antibody (1:1,000) for 1 h, and the cell nuclei were

further stained with 300 nM DAPI (cat. no. D9542; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA). The cells were visualized under a confocal microscope

and the staining was quantitated by ImageJ 1.52v software (National

Institutes of Health).

Mitochondria morphology by electron

microscopy

Treated cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at

room temperature for 15 min, and then dehydrated by using a series

of increasing concentrations of ethanol, and embedded in epoxy

resin and propylene oxide overnight. The 70 nm-thick sample

sections were then stained with lead citrate, and mitochondria

morphology was detected by double-blinded technicians using a

transmission electron microscope (28).

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation on the human PGC1β promoter was

evaluated by methylation-specific PCR according to a previously

described method with minor modifications (29–31).

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified from treated cells, and then

treated by bisulfite modification with EpiJET Bisulfite Conversion

kit (cat. no. K1461; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the DNA

was then amplified by using the following primers: Methylated

primers: Forward 5′-ttt tta aag tgt tgg gat tat agg c-3′ and

reverse 5′-acg tta cgt taa cgc taa acg a-3′; and unmethylated

primers: Forward 5′-ttt aaa gtg ttg gga tta tag gtg t-3′ and

reverse 5′-tca cat tac att aac act aaa caa a-3′. The product sizes

were as follows: 142 bp (methylated) with melting temperature (Tm)

66.4°C and 142 bp (unmethylated) with Tm 65.8°C; CpG island size:

197 bp. The methylation results were calculated by normalization of

the unmethylated PCR results (32).

In vivo mouse experiments

Tumor cells were treated, and then 2×106

viable cells in 0.1 ml PBS were injected into the lateral tail vein

of mice. The null mice receiving tail vein injections were

separated into the following 4 groups (n=9): i) Group 1 [control

(CTL)], conditionally immortalized HSC at passage #6 after vehicle

lentivirus infection; ii) group 2 (EBV), conditionally immortalized

HSC at passage #6 after EBV infection; iii) group 3 (LMP1↑),

conditionally immortalized HSC at passage #6 after LMP1 adenovirus

infection; and iv) group 4 (EBV/shPGC1β), conditionally

immortalized HSC at passage #6 after EBV infection and shPGC1β

lentivirus infection in the presence of 10 µg/ml puromycin. Mouse

survival was monitored and calculated; the tumor growth was

calculated; the lungs were isolated and stained with hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E); and the gene expression and superoxide anion

(O2−.) release from tumor tissues were

evaluated (7,23,33).

Statistical analysis

The mean level and standard deviation (SD) were

calculated and presented, and each experiment was performed for at

least 4 independent times (n=4) unless otherwise mentioned. The

data was analyzed as normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk test to

evaluate the normality of the data in SPSS 22 software (34), and the one-way ANOVA (analysis of

variance) together with Tukey-Kramer test were employed to

determine significant difference of different groups. The mouse

survival curve was established by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

followed by the log-rank test through SPSS 22 software, and

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference (33).

Results

LMP1 knockdown in EBV-positive tumor

cells does not reduce PGC1β-mediated tumorigenesis

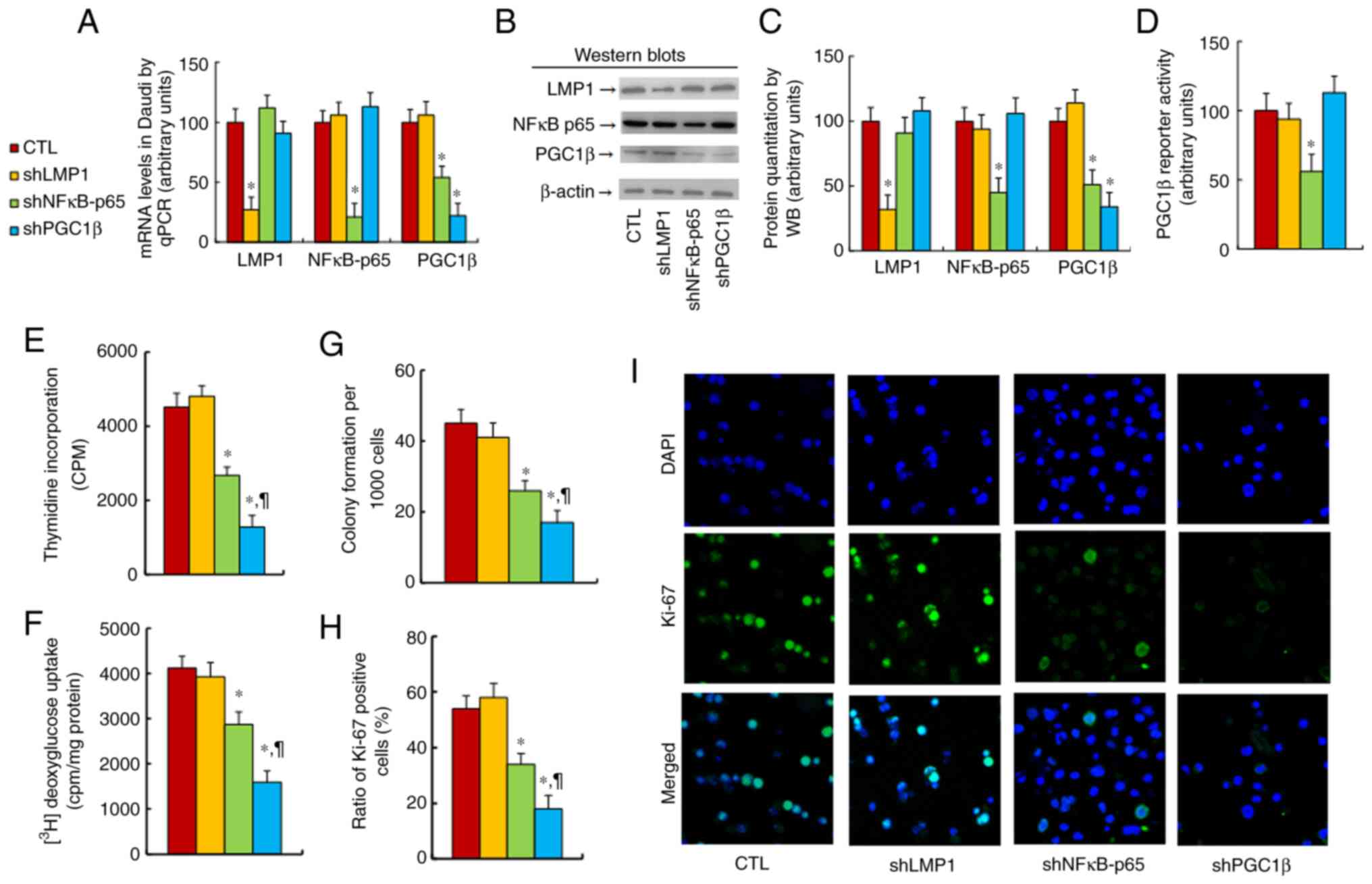

The effect of LMP1 on PGC1β expression was

determined. SNK6 cells were treated with CTL, shLMP1, shNF-κB-p65

or shPGC1β lentivirus before being harvested for biological assays.

It was found that knockdown of either NF-κB-p65 (shNF-κB-p65) or

PGC1β (shPGC1β) significantly reduced PGC1β mRNA levels in SNK6

cells compared with the findings in the CTL group, while LMP1

knockdown (shLMP1) had no effect (Fig.

1A). Next, the levels of proteins corresponding to the LMP1,

NF-κB-p65 and PGC1β genes were measured, and it was revealed that

the protein levels were similar to the mRNA levels (Figs. 1B and C, and S1A). Next, PGC1β reporter activity was

evaluated in the cells, and it was identified that shNF-κB-p65

treatment significantly reduced PGC1β reporter activity, while

shLMP1 and shPGC1β showed no effect (Fig. 1D). Gene expression was also

determined in other EBV-positive cell lines, including HANK1

(Fig. S2A) and SNT8 (Fig. S2B) cells, and it was found that

treatment with either shNF-κB-p65 or shPGC1β significantly reduced

the PGC1β mRNA levels, while shLMP1 showed no effect.

In addition, the potential effects of the treatment

on epigenetic changes on the PGC1β promoter were measured, and it

was observed that none of the treatments had a significant effect

on histone 3 methylation (Fig.

S3A), DNA methylation (Fig.

S3B), histone 3 acetylation (Fig.

S3C) or histone 4 methylation (Fig. S3D). Finally, the effect of

LMP1/PGC1β expression on tumor cell growth was explored, and it was

demonstrated that shLMP1 treatment had no effect, while treatment

with either shNF-κB-p65 or shPGC1β significantly reduced cellular

proliferation, as evaluated by thymidine incorporation (Fig. 1E), glucose uptake (Fig. 1F), colony formation assay (Fig. 1G) and Ki-67-positive cell rate

(Fig. 1H and I). It was concluded

that LMP1 knockdown did not affect PGC1β expression or its

subsequent tumorigenesis in EBV-positive cells.

PGC1β regulates DRP1 expression

through GABPα/NRF1 binding sites on the DRP1 promoter

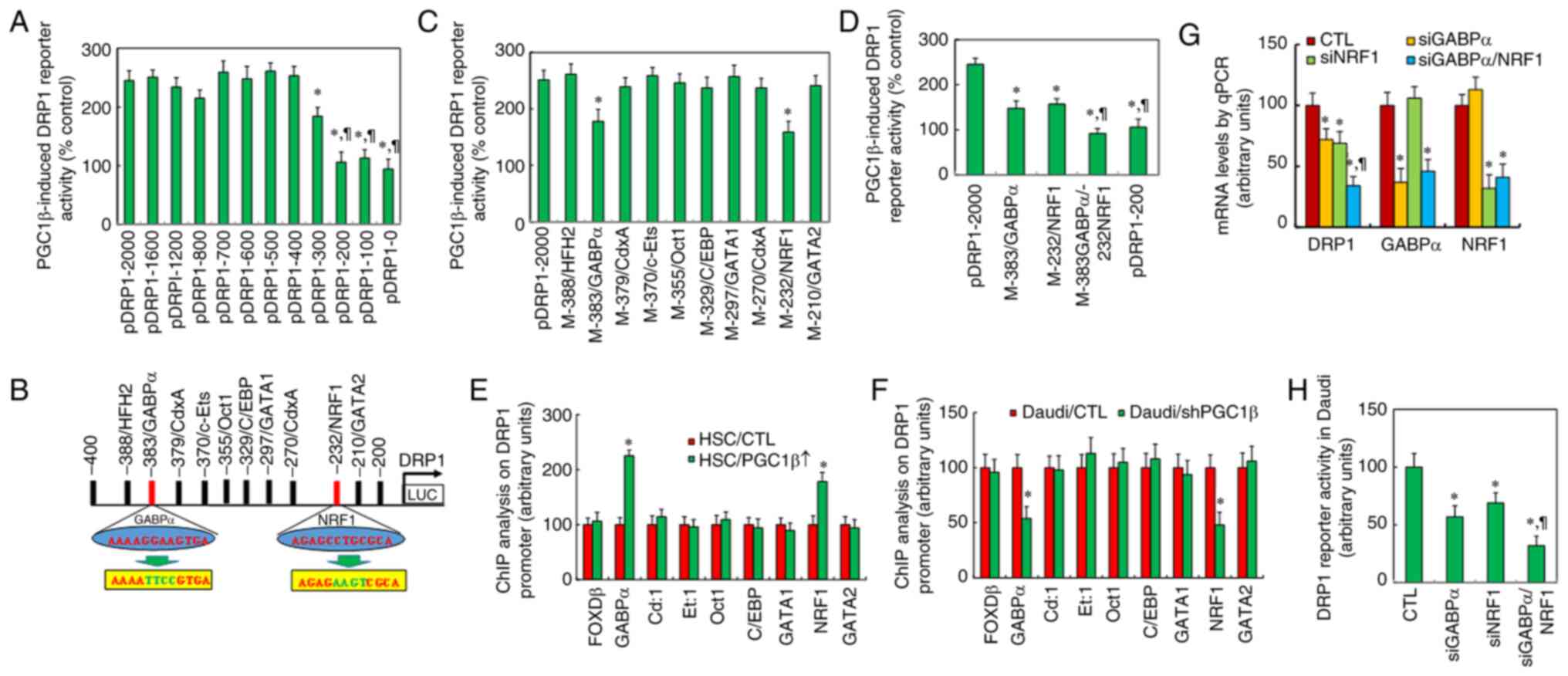

The current study determined the mechanism behind

PGC1β-mediated DRP1 regulation in immortalized HSC. Different

progressive 5′-promoter deletion constructs for DRP1 were generated

and transfected into HSC together with full-length DRP1 reporter

plasmids. The cells were then infected with either PGC1β or empty

lentivirus (CTL) for luciferase activity assay, and the results

showed that PGC1β-induced DRP1 reporter activity did not change

among the −2,000, −1,600, −1,200, −800, −700, −600, −500 and −400

deletion constructs (numbered according to the Ensembl gene ID:

DNM1L-201 ENST00000266481.10), while PGC1β-induced reporter

activation was partly decreased at −300 deletion and completely

disappeared at the −200-deletion construct. This indicates that the

PGC1β-responsive binding element is located in the range of −400 to

−200 on the DRP1 promoter (Fig.

2A).

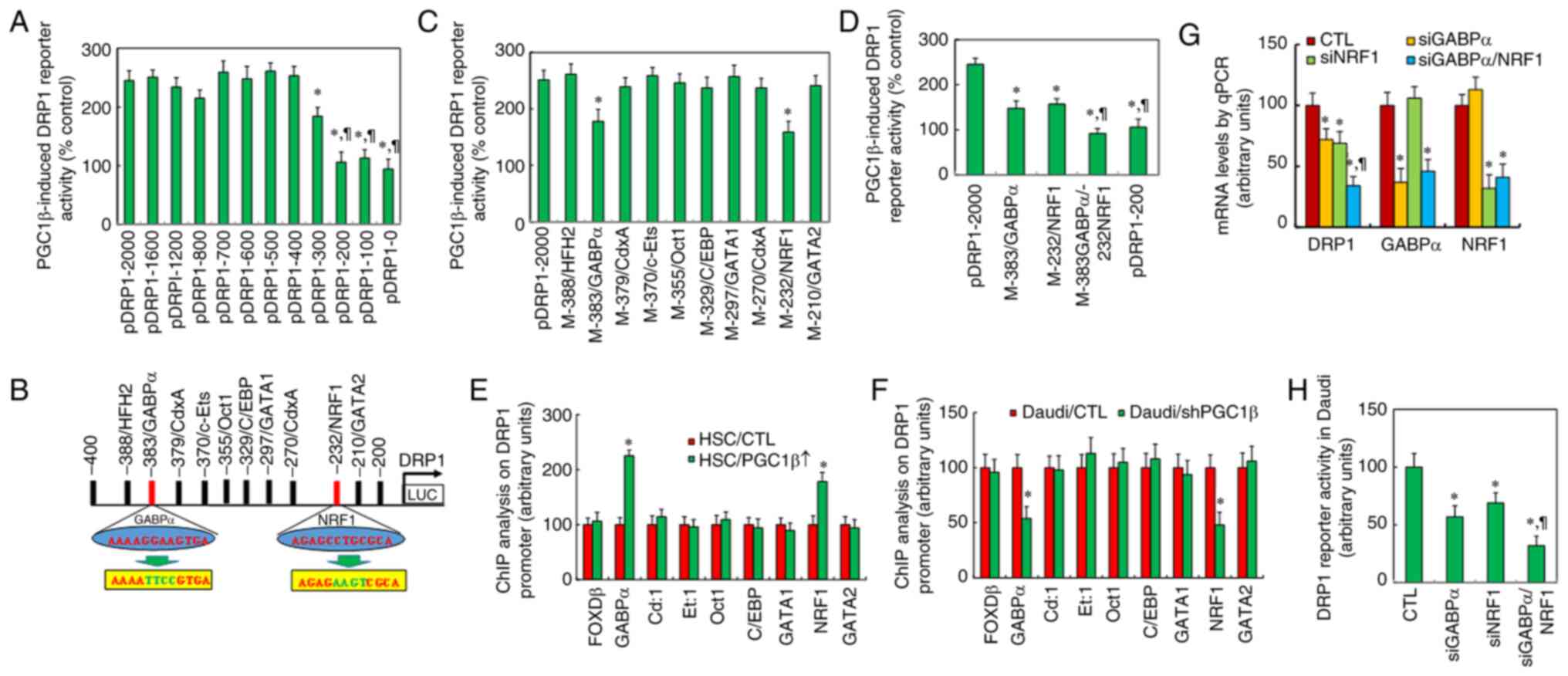

| Figure 2.Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-γ coactivator-1β regulates DRP1 expression through

GABPα/NRF1 binding sites on the DRP1 promoter. (A) Luciferase

activities for the indicated deletion reporter constructs in

immortalized HSC. *P<0.05 vs. pDRP1-2,000 group;

¶P<0.05 vs. pDRP1-300 group (n=5). (B) Schematic

model for potential transcriptional binding motif in the range of

−400 to −200 on the DRP1 promoter, with binding motif for GABPα and

NRF1 in red and related mutation sites in green. (C) Luciferase

activity for full-length DRP1 (pDRP1-2000) or the indicated

mutation reporter constructs. *P<0.05 vs. pDRP1-2,000 group

(n=5). (D) Luciferase activities for single or double mutants for

GABPα (−383) and/or NRF1 (−232). *P<0.05 vs. pDRP1-2,000 group;

¶P<0.05 vs. M-383/GABPα group (n=5). (E) ChIP

analysis (n=5). *P<0.05 vs. HSC/CTL group. (F) ChIP analysis

(n=5). *P<0.05 vs. SNK6/CTL group. (G and H) Small interfering

RNA was used to knockdown either GABPα or NRF1 in SNK6 cells for

further analysis. (G) mRNA levels were determined by quantitative

PCR (n=4). (H) DRP1 reporter activity (n=5). *P<0.05 vs. CTL

group. DRP1, dynamin-related protein 1; GABPα, GA-binding protein

α; NRF1, nuclear respiratory factor 1; CTL, control; HSC,

hematopoietic stem cells; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation. |

All the potential transcription factor binding sites

in the range of −400 to −200 were analyzed from the database, and

the following motifs were identified: HFH2, GABPα (marked in red),

CdxA, c-Ets, Oct1, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein, GATA1, NRF1

(marked in red) and GATA2 (Fig.

2B). All the single mutations were then generated on the full

length of the DRP1 reporter construct (p-DRP1-2000) for these

binding motifs for the luciferase reporter assay, and the results

showed that only single mutants for GABPα (from ggaa to ttcc, in

green at −383) and NRF1 (from cctg to aagt, in green at −232)

showed a significant reduction in reporter activity, indicating

that GABPα and NRF1 may be responsible for PGC1β-induced DRP1

activation (Fig. 2C). Next, GABPα

or NRF1 single or double mutants (M-383GABPα/-232NRF1) were

transfected for the reporter assay, and it was found that both

single mutants partly reduced, while the double mutants completely

reduced, the PGC1β-induced DRP1 reporter activation (Fig. 2D).

The binding abilities were then determined through

chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis on the DRP1 promoter. The

results revealed that both GABPα and NRF1 increased the binding

ability after PGC1β infection in HSC compared with that of the CTL

group, while other transcriptional factors had no effect (Fig. 2E). Additionally, both GABPα and NRF1

showed reduced binding ability after shPGC1β lentivirus infection

in SNK6 cells compared with that in the CTL group, while other

transcriptional factors had no effect (Fig. 2F).

Finally, the potential effect of GABPα and NRF1 on

DRP1 expression in SNK6 cells was determined by siRNA techniques,

and it was observed that GABPα and NRF1 were knocked down

successfully by siGABP and siNRF1 respectively. Additionally, the

DRP1 mRNA level was significantly decreased by single knockdown of

either GABPα or NRF1 compared with that of the CTL group, and the

DRP1 mRNA level was further decreased by double knockdown

(siGABPα/NRF1) compared with that of the single siGABPα group

(Fig. 2G). The DRP1 reporter

activity was also determined, and it was found to be similar to the

DRP1 mRNA levels (Fig. 2H). It was

concluded that DRP1 expression was regulated by PGC1β through GABPα

and NRF1 binding sites on the DRP1 promoter.

EBV/LMP1 exposure causes persistent

epigenetic modifications on the PGC1β promoter

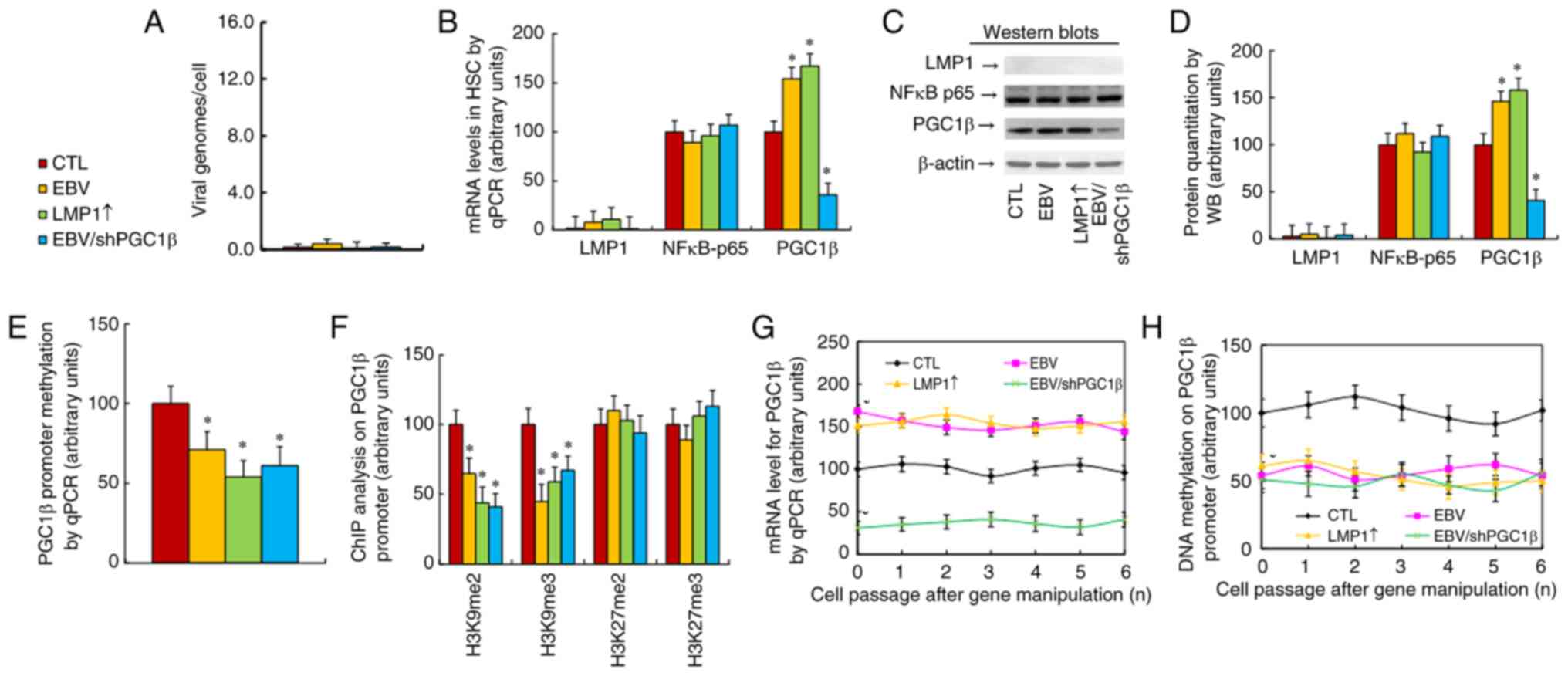

The present study evaluated the potential effect of

LMP1 expression on epigenetic changes on the PGC1β promoter.

Conditionally immortalized HSC were treated with CTL, transient EBV

infection, transient LMP1 infection by LMP1 adenovirus (LMP↑), or

EBV infection together with permanent PGC1β knockdown through

shPGC1β lentivirus in the presence of 10 µg/ml puromycin

(EBV/shPGC1β). The cells were continuously cultured from passage #1

to #6 before being harvested for analysis on different passages.

The properties of cells at passage #1 were first evaluated, and the

results revealed that EBV infection, including EBV and EBV/shPGC1β

treatments, significantly increased the quantity of EBV genome

copies compared with those of the CTL group (Fig. S4A). Additionally, treatments with

EBV, LMP1↑ and EBV/shPGC1β significantly increased LMP1 mRNA

levels. Moreover, treatments with EBV and LMP1↑ significantly

increased, while EBV/shPGC1β treatment significantly decreased, the

PGC1β mRNA levels. None of treatments had a significant effect on

NF-κB-p65 expression compared with that of the CTL group (Fig. S4B). The effect on epigenetic

changes on the PGC1β promoter at passage #1 was also determined,

and it was found that treatments with EBV, LMP1↑ and EBV/shPGC1β

significantly decreased the epigenetic modifications on H3K9me2 and

H3K9me3 (Fig. S4C) in addition to

DNA methylation (Fig. S4D). These

treatments had no effect on histone 4 methylation (Fig. S4E) or histone 3 acetylation

(Fig. S4F) compared with the CTL

group.

Next, the properties of cells at passage #6 were

determined. The results showed that the EBV genome was almost

non-detectable upon treatment with EBV, LMP1↑ or EBV/shPGC1β after

continuous culturing for 6 passages (Fig. 3A). Additionally, LMP1 mRNA was not

detectable, while the NF-κB-p65 mRNA levels showed no changes. On

the other hand, PGC1β mRNA remained increased after EBV and LMP1↑

treatment, while it remained decreased upon EBV/shPGC1β treatment

compared with that in the CTL group (Fig. 3B). The protein levels were also

measured, and the protein expression was similar to the mRNA levels

(Figs. 3C and D, and S1B). Epigenetic changes on the PGC1β

promoter were then determined, and it was found that treatments

with EBV, LMP1↑ and EBV/shPGC1β significantly decreased DNA

methylation (Fig. 3E) in addition

to epigenetic modifications on H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 (Fig. 3F), while having no effect on histone

3 acetylation (Fig. S5A) or

histone 4 methylation (Fig. S5B)

compared with the findings in the CTL group, where the epigenetic

modifications were similar to those noted in cells at passage

#1.

Finally, the PGC1β levels in cells from passage #1

to #6 were measured, and it was found that treatments with EBV and

LMP1↑ significantly increased, while EBV/shPGC1β decreased, PGC1β

mRNA. This remained persistent from passage #1 to #6 (Fig. 3G). The present study also measured

DNA methylation on the PGC1β promoter, and found that treatments

with EBV, LMP1↑ or EBV/shPGC1β significantly decreased DNA

methylation, which remained persistent from passage #1 to #6

(Fig. 3H). The potential effect of

LMP1 expression on PGC1β expression in other cells was also

determined, and it was revealed that treatments with EBV and LMP1↑

significantly increased, while EBV/shPGC1β treatment significantly

decreased, PGC1β expression in both PBMCs (Fig. S6A) and NK cells (Fig. S6B); this remained persistent from

passage #1 to #6. Thus, it was concluded that transient EBV/LMP1

exposure caused persistent epigenetic modifications on the PGC1β

promoter, which subsequently resulted in persistent PGC1β

upregulation even in the absence of EBV/LMP1.

EBV/LMP1 exposure ameliorates

oxidative stress, while PGC1β knockdown reverses this effect

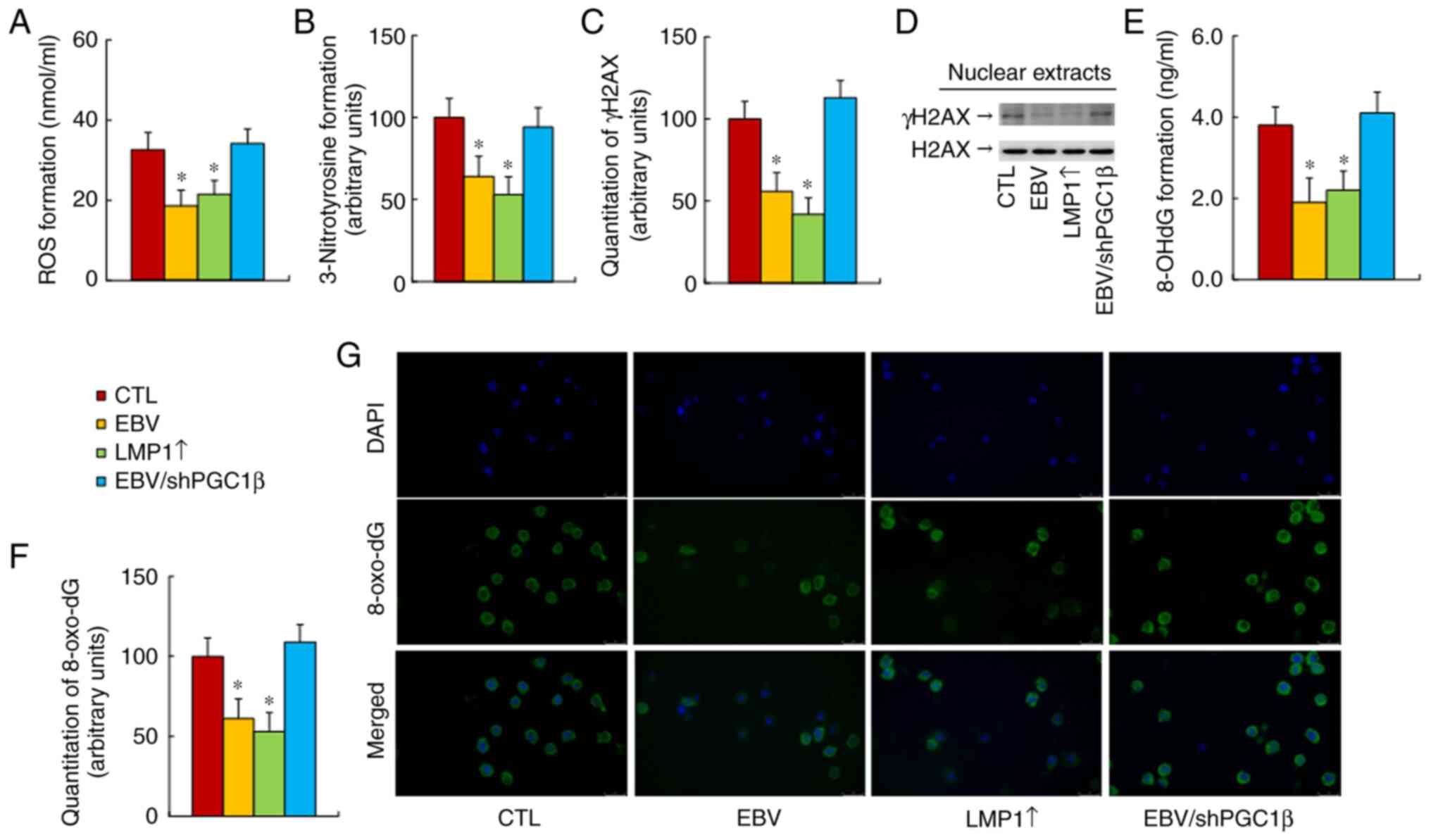

The current study evaluated the effect of EBV/LMP

expression on oxidative stress in treated cells at passage #6, and

found that both EBV and LMP1↑ treatments significantly decreased

reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig.

4A) and 3-nitrotyrosine formation (Fig. 4B) formation compared with those of

the CTL group, while PGC1β knockdown (EBV/shPGC1β) completely

reversed this effect. The oxidative stress-mediated DNA damage was

also determined, and the results showed that both EBV and LMP1↑

treatments significantly decreased γH2AX (Figs. 4C and D, and S1C), 8-OHdG (Fig. 4E) and 8-oxo-dG (Fig. 4F and G) formation, while PGC1β

knockdown completely reversed this effect. Thus, it was concluded

that EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated PGC1β expression ameliorated

oxidative stress.

EBV/LMP1 exposure potentiates

mitochondrial function, while PGC1β knockdown reverses this

effect

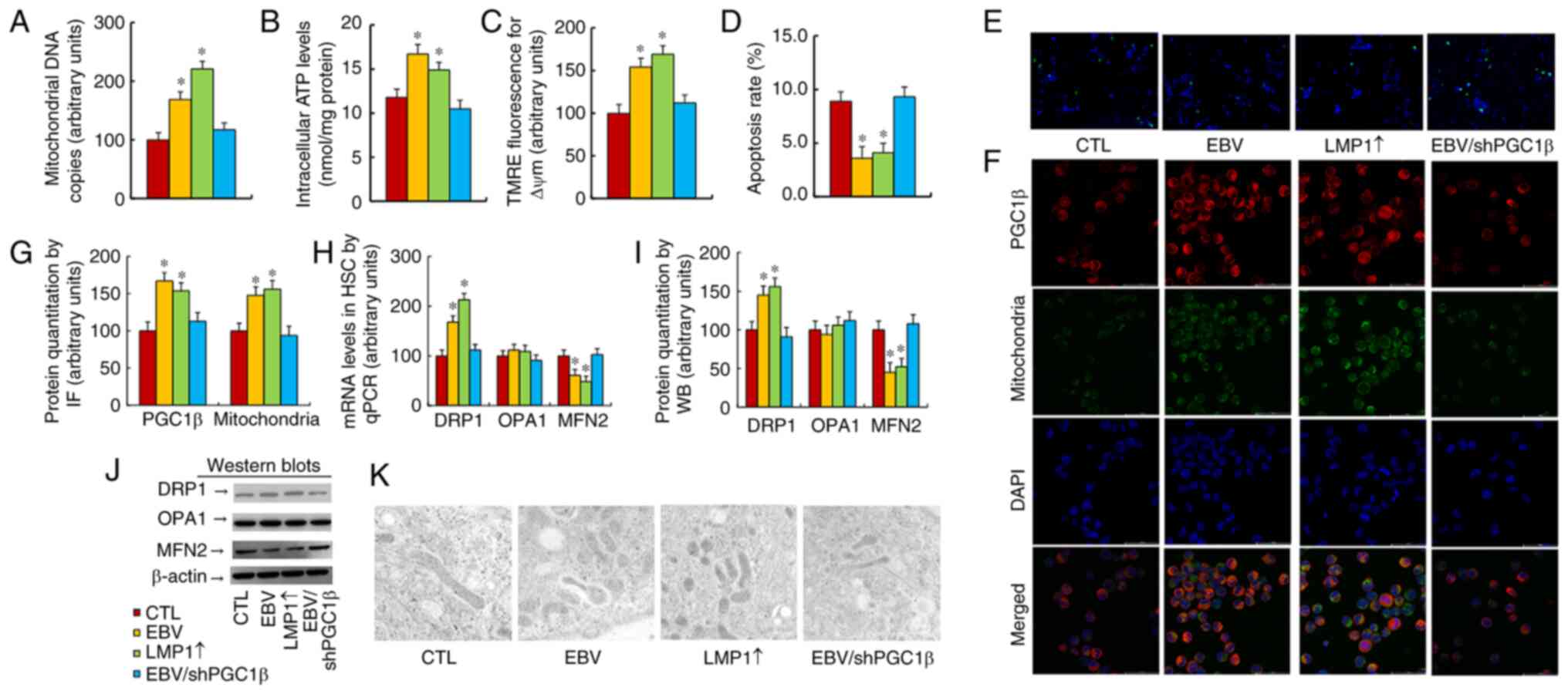

The present study evaluated the effect of EBV/LMP1

expression on mitochondrial function, and found that both EBV and

LMP1↑ treatments significantly increased mitochondrial DNA copies

(Fig. 5A), intracellular ATP level

(Fig. 5B) and mitochondrial

membrane potential (Fig. 5C), in

addition to decreasing the apoptotic rate (Figs. 4D and 5E) compared with the findings in the CTL

group. Notably, PGC1β knockdown completely reversed this

effect.

Mitochondrial mass and gene expression were then

evaluated, and the results revealed that both EBV and LMP1↑

treatments significantly increased PGC1β expression and

mitochondrial mass by immunostaining (Fig. 5F and G) compared with those of the

CTL group. Both EBV and LMP1↑ treatments significantly increased

DRP1 expression and decreased MFN2 expression, but had no effect on

OPA1 expression (Figs. 5H-J and

S1D). Finally, changes in

mitochondrial morphology were evaluated by using an electron

microscope, and it was found that both EBV and LMP1↑ treatments

significantly increased mitochondrial fission compared with that of

the CTL group, while PGC1β knockdown completely reversed this

effect (Fig. 5K). Therefore, it was

concluded that EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated PGC1β expression

potentiated mitochondrial function by upregulation of mitochondrial

fission.

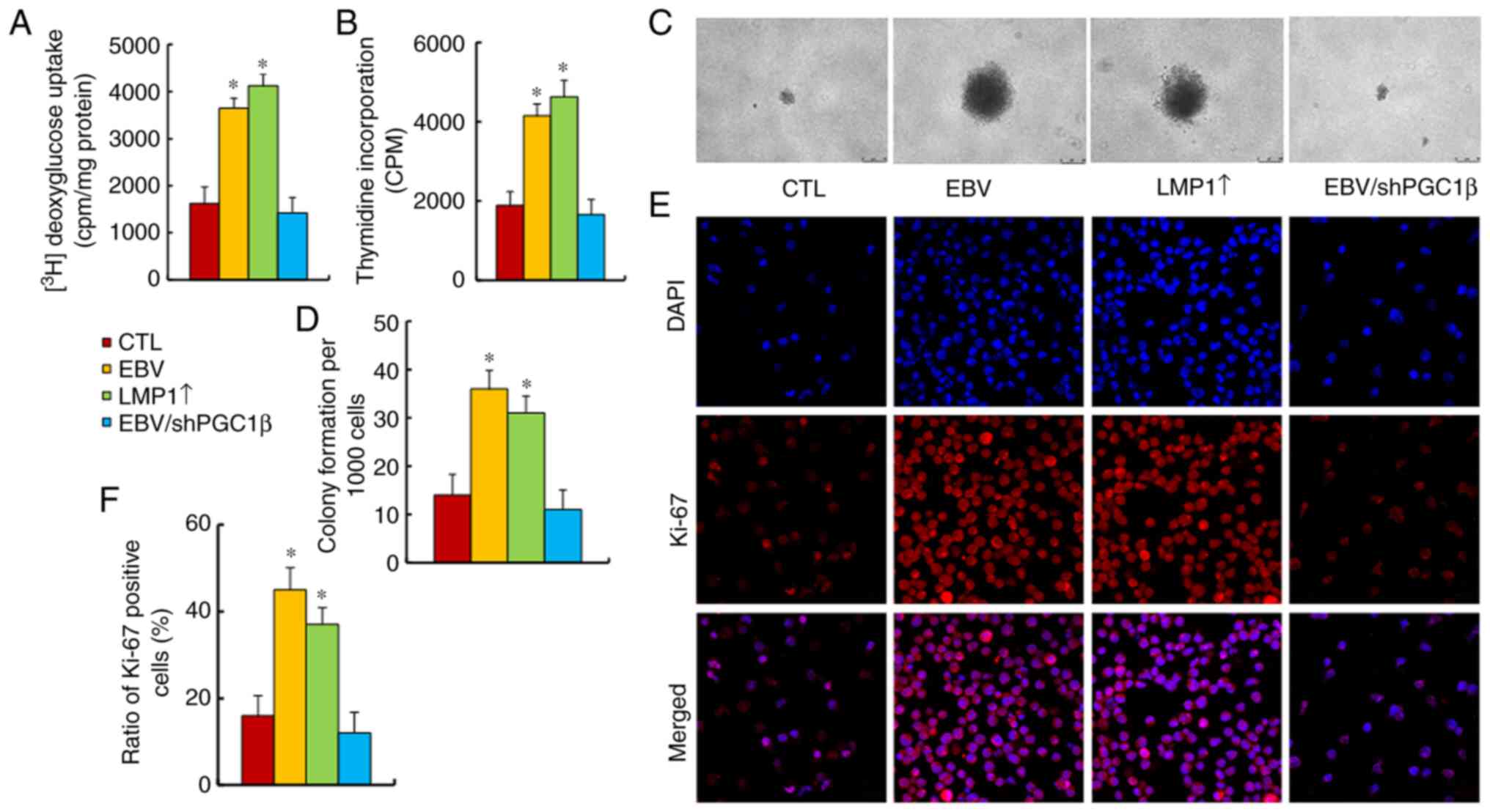

EBV/LMP1 exposure potentiates tumor

cell proliferation, while PGC1β knockdown reverses this effect

The present study evaluated the effect of EBV/LMP1

exposure on tumor cell proliferation, and found that both EBV and

LMP1↑ treatments significantly increased

[3H]-2-deoxyglucose uptake (Fig. 6A), cellular proliferation by

thymidine incorporation (Fig. 6B),

colony formation (Fig. 6C and D)

and Ki-67 positive cells (Fig. 6E and

F), compared with those in the CTL group. Of note, PGC1β

knockdown completely reversed this effect. Thus, it was concluded

that EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated PGC1β expression potentiated tumor

cell proliferation.

EBV/LMP1 exposure potentiates tumor

growth in vivo in mice, while PGC1β knockdown reverses this

effect

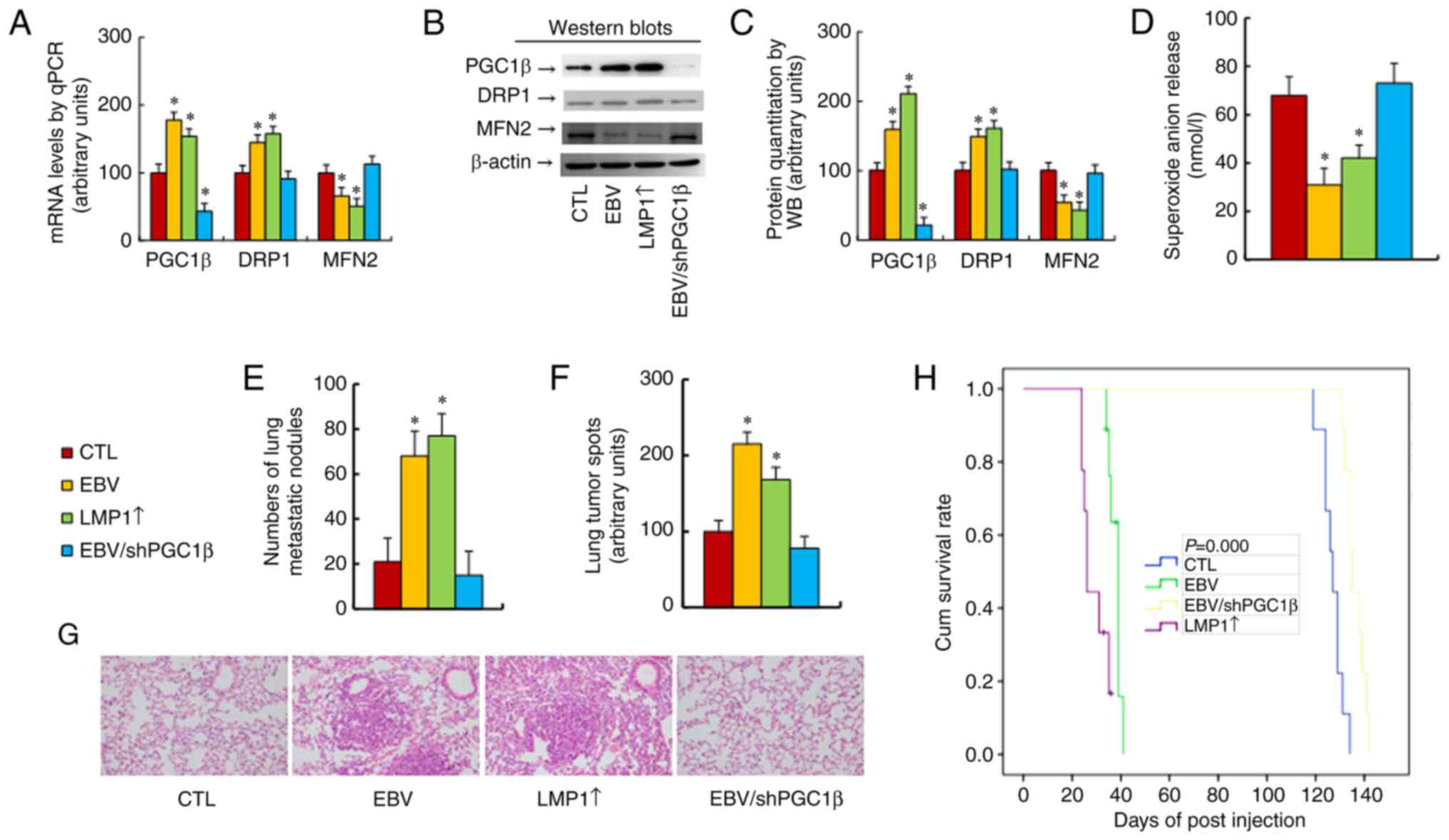

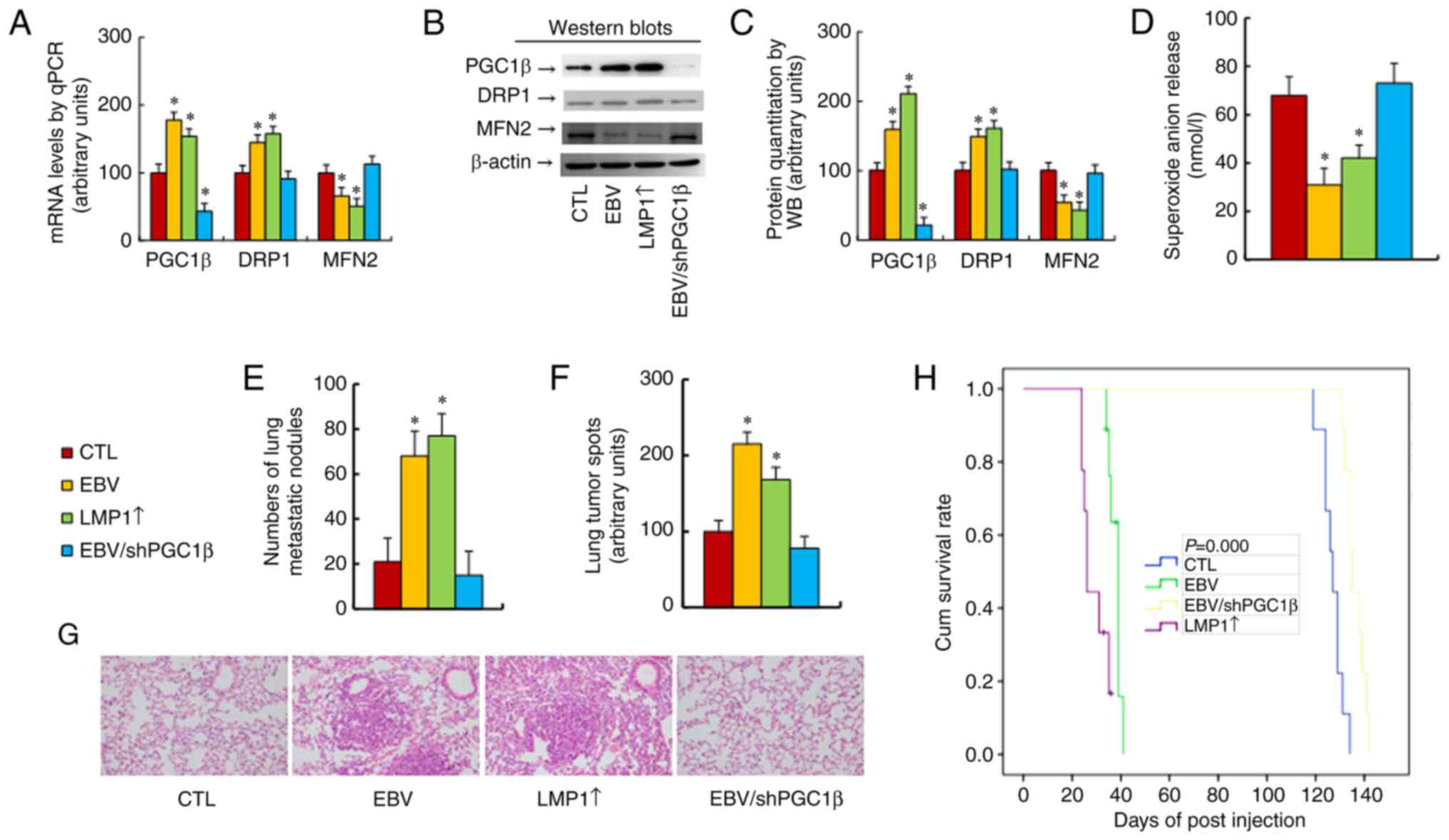

The current study determined the potential effect of

EBV/LMP1 expression on in vivo tumor growth. Treated cells

at passage #6 were harvested for tail vein injection to monitor the

process of tumor growth. Gene expression was first determined in

the tumor tissues, and it was found that cells that received

treatment with either EBV or LMP1↑ showed significantly increased

mRNA levels of PGC1β and DRP1 but decreased mRNA levels of MFN2

compared with those of the CTL group. PGC1β knockdown completely

reversed this effect (Fig. 7A).

| Figure 7.EBV/LMP1 exposure potentiates tumor

growth in vivo in mice, while PGC1β knockdown reverses this

effect. Conditionally immortalized hematopoietic stem cells were

treated with CTL, EBV, LMP1 adenovirus (LMP1↑) or EBV together with

shPGC1β lentivirus in the presence of 10 µg/ml puromycin

(EBV/shPGC1β). The cells were continuously cultured, and cells at

passage #6 were harvested for tail vein injection to monitor the

process of tumor growth in mice. (A-D) Isolated tumor tissues for

biological assays. (A) mRNA levels, as determined by quantitative

PCR (n=4). (B) Representative western blot bands. (C) Protein

quantitation of panel B (n=5). (D) Superoxide anion release (n=5).

(E) Tumor colony formation in lungs (n=9). (F) Quantification of

lung tumor spots (n=5). (G) Representative image of hematoxylin and

eosin staining for panel F. (H) Kaplan-Meier analysis of mouse

survival (n=9). *P<0.05 vs. CTL group. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus;

LMP1, latent membrane protein 1; PGC1β, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1β; CTL, control; sh,

short hairpin. |

Next, the protein levels were determined, and they

were identified to be similar to the mRNA levels (Figs. 7B and C, and S1E). Furthermore, both EBV and LMP1↑

treatments significantly decreased O2−.

release (Fig. 7D) and increased the

number of lung metastatic nodules (Fig.

7E) and lung tumor spots (Fig. 7F

and G) compared with the CTL group. In addition, both EBV and

LMP1↑ treatments significantly decreased mouse survival compared

with that of the CTL group (Fig.

7H). PGC1β knockdown completely reversed this effect. It was

concluded that EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated PGC1β expression

significantly potentiated tumor growth in vivo and shortened

mouse survival.

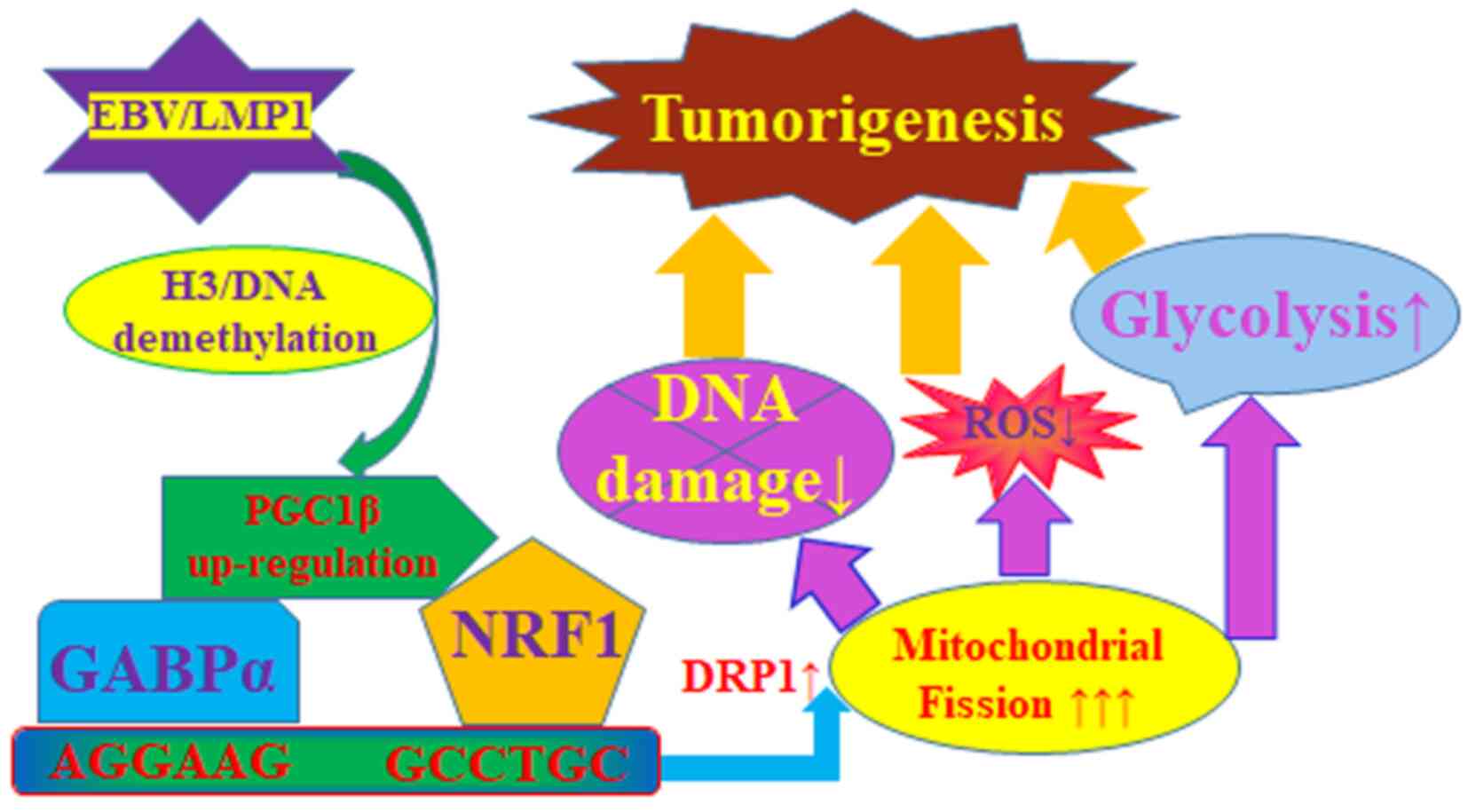

Schematic model of EBV/LMP1-mediated

epigenetic modifications and tumorigenesis through upregulation of

PGC1β and DRP1

The current study established a schematic model for

EBV/LMP1-mediated tumorigenesis through persistent epigenetic

changes on the PGC1β promoter and subsequent upregulation of PGC1β

and DRP1: Briefly, transient EBV/LMP1 exposure triggers epigenetic

changes, including decreased histone 3 methylation and DNA

methylation on the PGC1β promoter, resulting in persistent PGC1β

upregulation. Increased PGC1β expression upregulates DRP1

expression through the transcription factors GABPα and NRF1,

resulting in mitochondrial fission with potentiated glycolysis,

minimized oxidative stress and DNA damage. Taken together,

transient EBV/LMP1 exposure triggers persistent PGC1β upregulation

and tumorigenesis (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that LMP1 knockdown

in EBV-positive tumor cells did not suppress PGC1β expression or

tumor cell proliferation. However, transient LMP1 expression in HSC

caused epigenetic changes on the PGC1β promoter, resulting in

persistent PGC1β upregulation with potentiated DRP1 expression and

mitochondrial function, thus contributing to PGC1β-mediated

tumorigenesis.

As a potential oncogene (8), LMP1 transforms B cells and activates

the NF-κB signaling pathway through two domains of transformation

effector sites that are located at the C-terminus, subsequently

resulting in target gene expression and tumorigenesis (15–17).

The present study found that LMP1 expression triggered epigenetic

changes by demethylation of both histone 3 and DNA on the PGC1β

promoter, subsequently contributing to PGC1β upregulation. Our

preliminary study showed that EBV/LMP1 exposure could change the

expression of either DNA methyltransferases or histone

methyltransferases (35,36), subsequently contributing to

epigenetic changes. Currently, investigation on the potential

mechanism concerning EBV/LMP1-mediated epigenetic modifications is

underway in our laboratory. Notably, LMP1 expression-mediated

epigenetic changes and PGC1β upregulation were persistent even in

the absence of LMP1 after the cells were cultured from passage #1

to #6, indicating that LMP1-mediated tumorigenesis may be

independent from LMP1. This may explain why numerous forms of

lymphoma show absence of EBV/LMP1; thus, the current study

elucidated a novel mechanism and pathway for EBV/LMP1-mediated

tumorigenesis through epigenetic changes (37,38).

It has been reported that EBV/LMP1 can infect and transform B

lymphocytes (16), while the

present study showed that HSC could also be infected and

transformed, since numerous HSC could differentiate into either NK

or T cells, which may explain why EBV is associated with NK/T-cell

lymphoma (39).

It has been reported that DRP1 is responsible for

mitochondrial fission (11), while

both OPA1 and MFN2 are responsible for mitochondrial fusion

(40). The present study found that

EBV/LMP1 exposure induced DRP1 upregulation and MFN2

downregulation, but showed no effect on OPA1. This effect was

completely reversed by PGC1β knockdown, indicating that

EBV/LMP1-mediated mitochondrial fission/fusion gene expression was

mediated by PGC1β (41). Further

experiments showed that DRP1 was regulated by PGC1β through GABPα

and NRF1 binding sites located on the DRP1 promoter; however, the

potential mechanism for PGC1β-mediated MFN2 downregulation remains

unknown. Moreover, the present results revealed that

EBV/LMP1-mediated PGC1β expression significantly changed

mitochondrial morphology together with potentiated mitochondrial

function, including increased mitochondria DNA copies,

intracellular ATP levels and mitochondrial membrane potential, as

well as decreased apoptotic rate. Notably, EBV/LMP1-mediated PGC1β

expression significantly ameliorated oxidative stress and

subsequent DNA damage; this may be due to the fact that increased

mitochondrial replication partly diminishes ROS generation

(42).

PGC1β is a transcriptional coactivator that

regulates genes involved in mitochondrial function, and energy

balance and metabolism (19). It

has been reported that PGC1β contributes to tumorigenesis through

regulation of glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism (20–22,43,44).

Our group has recently found that PGC1β regulates tumor growth

through LDHA-mediated glycolysis and HKDC1-mediated mitochondrial

function (23,24). In the present study, it was found

that PGC1β contributed to tumorigenesis through DRP1-mediated

mitochondrial fission. Additionally, increased PGC1β expression

upregulates the expression of LDHA (23), HKDC1 (24) and OGG1 (45), resulting in potentiated glycolysis,

and minimized oxidative stress and DNA damage.

It has benn previously reported by the authors that

LMP1 upregulates the PGC1β expression through activation of nuclear

factor-κB (NFκB) pathway (17), but

did not show the reason as why and/or how NFκB is activated in the

presence of LMP1. The present study revealed that knockdown of

either LMP1, NFκB or PGC1β has no effect, while transient EBV/LMP1

exposure induces persistent demethylation on both histone 3 and DNA

on the PGC1β promoter, indicating that LMP1-mediated NFκB

activation is probably due to LMP1-mediated demethylation and

subsequently potentiated binding ability of NFκB on the PGC1β

promoter. Our future work involves investigating the potential

mechanism of LMP1-mediated persistent epigenetic changes with the

aim of addressing the following questions: i) How could

LMP1-mediated epigenetic modifications be reversed? ii) do

LMP1-mediated epigenetic changes only happen on the PGC1β promoter,

or do they also occur on other genes?; and iii) how could it be

determined whether upregulated PGC1β is due to historical LMP1

infection in EBV/LMP1 absent tumors? These questions are part of

our ongoing investigation.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

PGC1β modulated mitochondrial fission and glycolysis through DRP1

expression, and that EBV/LMP1 transient exposure triggered

persistent epigenetic changes with subsequent PGC1β upregulation

and tumor growth. These findings suggest a potential mechanism for

transient EBV/LMP1 exposure-mediated tumor growth through

persistent PCG1β expression and provide a hypothesis to explain why

numerous forms of lymphoma exhibit absence of EBV/LMP1.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the kind generous gift

from Dr Haimou Zhang (Hubei University, China) for providing EBV

LMP1 adenovirus.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82170191, 82100210 and 82201739),

the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (grant no.

2021A1515012185), the Shenzhen Municipal Science and Technology

Innovation (grant nos. JCYJ20160428172335984 and

JCYJ20220530160214031), the Research Foundation of Peking

University Shenzhen Hospital (grant nos. JCYJ2020017, JCYJ2021007

and KYQD202100X), the General Program for Clinical Research at

Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (grant no. LCYJ2021037), the

Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (grant ns. SZSM201612071),

the Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (grant ns.

SZXK078) and the Cell Technology Center and Transformation Base,

Innovation Center of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area,

Ministry of Science and Technology of China [grant no.

YCZYPT(2018)03-1].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article or from the corresponding author

on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

PY wrote the paper and designed the primers. PY and

HZ designed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the

results and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. JF and RL

performed part of the gene analysis and IHC staining experiments.

JC and WZ performed part of animal operation and biomedical

analysis. SC and PZ performed the remaining experiments. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The protocols for animal study (approval no.

2021-092) and human subjects (approval no. 2020-050) were approved

by the Committee from Peking University Shenzhen Hospital

(Shenzhen, China) and the written consents for human subjects were

given on the base of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DRP1

|

dynamin-related protein 1

|

|

EBV

|

Epstein-Barr virus

|

|

GABPα

|

GA-binding protein α

|

|

HKDC1

|

hexokinase domain component 1

|

|

HSC

|

hematopoietic stem cells

|

|

LDHA

|

lactate dehydrogenase A

|

|

LMP1

|

latent membrane protein 1

|

|

MFN2

|

mitofusin 2

|

|

MMP

|

mitochondrial membrane potential

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor-κB

|

|

NRF1

|

nuclear respiratory factor 1

|

|

NKTCL

|

natural killer/T-cell lymphoma

|

|

O2.-

|

superoxide anion

|

|

OGG1

|

8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1

|

|

OPA1

|

optic atrophy 1

|

|

PGC1β

|

peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-γ coactivator-1β

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

References

|

1

|

Wirtz T, Weber T, Kracker S, Sommermann T,

Rajewsky K and Yasuda T: Mouse model for acute Epstein-Barr virus

infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:13821–13826. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tsai MH, Lin X, Shumilov A, Bernhardt K,

Feederle R, Poirey R, Kopp-Schneider A, Pereira B, Almeida R and

Delecluse HJ: The biological properties of different Epstein-Barr

virus strains explain their association with various types of

cancers. Oncotarget. 8:10238–10254. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fujimoto A and Suzuki R: Epstein-barr

virus-associated Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders

after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Pathogenesis, risk

factors and clinical outcomes. Cancers (Basel). 12:3282020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang Y, Zhu Y, Cao JZ, Zhang YJ, Xu LM,

Yuan ZY, Wu JX, Wang W, Wu T, Lu B, et al: Risk-adapted therapy for

early-stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma: Analysis from

a multicenter study. Blood. 126:1424–1432. 15172015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lai J, Tan WJ, Too CT, Choo JA, Wong LH,

Mustafa FB, Srinivasan N, Lim AP, Zhong Y, Gascoigne NR, et al:

Targeting Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphoblastoid cells

using antibodies with T-cell receptor-like specificities. Blood.

128:1396–1407. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nam YS, Im KI, Kim N, Song Y, Lee JS, Jeon

YW and Cho SG: Down-regulation of intracellular reactive oxygen

species attenuates P-glycoprotein-associated chemoresistance in

Epstein-Barr virus-positive NK/T-cell lymphoma. Am J Transl Res.

11:1359–1373. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang H, Lu J, Jiao Y, Chen Q, Li M, Wang

Z, Yu Z, Huang X, Yao A, Gao Q, et al: Aspirin inhibits Natural

Killer/T-cell lymphoma by modulation of VEGF expression and

mitochondrial function. Front Oncol. 8:6792019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chou YC, Lin SJ, Lu J, Yeh TH, Chen CL,

Weng PL, Lin JH, Yao M and Tsai CH: Requirement for LMP1-induced

RON receptor tyrosine kinase in Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell

proliferation. Blood. 118:1340–1349. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang LW, Jiang S and Gewurz BE:

Epstein-barr virus LMP1-mediated oncogenicity. J Virol.

91:e01718–16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xiao L, Hu ZY, Dong X, Tan Z, Li W, Tang

M, Chen L, Yang L, Tao Y, Jiang Y, et al: Targeting Epstein-Barr

virus oncoprotein LMP1-mediated glycolysis sensitizes

nasopharyngeal carcinoma to radiation therapy. Oncogene.

33:4568–4578. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pal AD, Basak NP, Banerjee AS and Banerjee

S: Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-2A alters

mitochondrial dynamics promoting cellular migration mediated by

Notch signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 35:1592–1601. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wakisaka N, Kondo S, Yoshizaki T, Murono

S, Furukawa M and Pagano JS: Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane

protein 1 induces synthesis of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha.

Mol Cell Biol. 24:5223–5234. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lo AK, Lung RW, Dawson CW, Young LS, Ko

CW, Yeung WW, Kang W, To KF and Lo KW: Activation of sterol

regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1)-mediated lipogenesis

by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1)

promotes cell proliferation and progression of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. J Pathol. 246:180–190. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bi XW, Wang H, Zhang WW, Wang JH, Liu WJ,

Xia ZJ, Huang HQ, Jiang WQ, Zhang YJ and Wang L: PD-L1 is

upregulated by EBV-driven LMP1 through NF-κB pathway and correlates

with poor prognosis in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. J Hematol

Oncol. 9:1092016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Higuchi M, Izumi KM and Kieff E:

Epstein-Barr virus latent-infection membrane proteins are

palmitoylated and raft-associated: Protein 1 binds to the

cytoskeleton through TNF receptor cytoplasmic factors. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 98:4675–4680. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dudziak D, Kieser A, Dirmeier U,

Nimmerjahn F, Berchtold S, Steinkasserer A, Marschall G,

Hammerschmidt W, Laux G and Bornkamm GW: Latent membrane protein 1

of Epstein-Barr virus induces CD83 by the NF-kappaB signaling

pathway. J Virol. 77:8290–8298. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Feng J, Chen Q, Zhang P, Huang X, Xie W,

Zhang H and Yao P: Latent membrane Protein 1 promotes tumorigenesis

through upregulation of PGC1β signaling pathway. Stem Cell Rev Rep.

17:1486–1499. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lin J, Puigserver P, Donovan J, Tarr P and

Spiegelman BM: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

coactivator 1beta (PGC-1beta), a novel PGC-1-related transcription

coactivator associated with host cell factor. J Biol Chem.

277:1645–1648. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lin J, Handschin C and Spiegelman BM:

Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription

coactivators. Cell Metab. 1:361–370. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Deblois G, Chahrour G, Perry MC,

Sylvain-Drolet G, Muller WJ and Giguere V: Transcriptional control

of the ERBB2 amplicon by ERRalpha and PGC-1beta promotes mammary

gland tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 70:10277–10287. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bellafante E, Morgano A, Salvatore L,

Murzilli S, Di Tullio G, D'Orazio A, Latorre D, Villani G and

Moschetta A: PGC-1β promotes enterocyte lifespan and tumorigenesis

in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:E4523–E4531. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Piccinin E, Villani G and Moschetta A:

Metabolic aspects in NAFLD, NASH and hepatocellular carcinoma: The

role of PGC1 coactivators. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

16:160–174. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang H, Li L, Chen Q, Li M, Feng J, Sun

Y, Zhao R, Zhu Y, Lv Y, Zhu Z, et al: PGC1β regulates multiple

myeloma tumor growth through LDHA-mediated glycolytic metabolism.

Mol Oncol. 12:1579–1595. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen X, Lv Y, Sun Y, Zhang H, Xie W, Zhong

L, Chen Q, Li M, Li L, Feng J, et al: PGC1β regulates breast tumor

growth and metastasis by SREBP1-mediated HKDC1 expression. Front

Oncol. 9:2902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt

SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S and

Wright WE: Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase

into normal human cells. Science. 279:349–352. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kong D, Zhan Y, Liu Z, Ding T, Li M, Yu H,

Zhang L, Li H, Luo A, Zhang D, et al: SIRT1-mediated ERβ

suppression in the endothelium contributes to vascular aging. Aging

Cell. 15:1092–1102. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lan K, Verma SC, Murakami M, Bajaj B and

Robertson ES: Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): Infection, propagation,

quantitation, and storage. Curr Protoc Microbiol. Chapter 14: Unit

14E.2. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gong LJ, Wang XY, Gu WY and Wu X:

Pinocembrin ameliorates intermittent hypoxia-induced

neuroinflammation through BNIP3-dependent mitophagy in a murine

model of sleep apnea. J Neuroinflammation. 17:3372020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Cantor

M, Kirkner GJ, Spiegelman D, Makrigiorgos GM, Weisenberger DJ,

Laird PW, Loda M and Fuchs CS: Precision and performance

characteristics of bisulfite conversion and real-time PCR

(MethyLight) for quantitative DNA methylation analysis. J Mol

Diagn. 8:209–217. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz

LB, Blake C, Shibata D, Danenberg PV and Laird PW: MethyLight: A

high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids

Res. 28:E322000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, Kure S,

Kirkner GJ, Schernhammer ES, Hazra A, Hunter DJ, Quackenbush J,

Spiegelman D, et al: Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG

island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large

population-based sample. PLoS One. 3:e36982008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zou Y, Lu Q, Zheng D, Chu Z, Liu Z, Chen

H, Ruan Q, Ge X, Zhang Z, Wang X, et al: Prenatal levonorgestrel

exposure induces autism-like behavior in offspring through ERβ

suppression in the amygdala. Mol Autism. 8:462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang H, Li L, Li M, Huang X, Xie W, Xiang

W and Yao P: Combination of betulinic acid and chidamide inhibits

acute myeloid leukemia by suppression of the HIF1α pathway and

generation of reactive oxygen species. Oncotarget. 8:94743–94758.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ramezani G, Norouzi A, Arabshahi SKS,

Sohrabi Z, Zazoli AZ, Saravani S and Pourbairamian G: Study of

medical students' learning approaches and their association with

academic performance and problem-solving styles. J Educ Health

Promot. 11:2522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Vargas-Ayala RC, Jay A, Manara F, Maroui

MA, Hernandez-Vargas H, Diederichs A, Robitaille A, Sirand C,

Ceraolo MG, Romero-Medina MC, et al: Interplay between the

Epigenetic Enzyme Lysine (K)-Specific demethylase 2B and

Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. J Virol. 93:e00273–19. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shi F, Zhou M, Shang L, Du Q, Li Y, Xie L,

Liu X, Tang M, Luo X, Fan J, et al: EBV(LMP1)-induced metabolic

reprogramming inhibits necroptosis through the hypermethylation of

the RIP3 promoter. Theranostics. 9:2424–2438. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Martin KA, Lupey LN and Tempera I:

Epstein-Barr Virus oncoprotein LMP1 mediates epigenetic changes in

host gene expression through PARP1. J Virol. 90:8520–8530. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Leonard S, Wei W, Anderton J, Vockerodt M,

Rowe M, Murray PG and Woodman CB: Epigenetic and transcriptional

changes which follow Epstein-Barr virus infection of germinal

center B cells and their relevance to the pathogenesis of Hodgkin's

lymphoma. J Virol. 85:9568–9577. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen Z, Liu W, Zhang W, Ye Y, Guan P, Gao

L and Zhao S: Chronic active Epstein-Barr Virus infection of

T/NK-cell type mimicking classic hodgkin lymphoma:

Clinicopathologic and genetic features of 8 cases supporting a

variant with ‘Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg-like’ cells of NK phenotype.

Am J Surg Pathol. 43:1611–1621. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rodrigues T and Ferraz LS: Therapeutic

potential of targeting mitochondrial dynamics in cancer. Biochem

Pharmacol. 182:1142822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kelly DP and Scarpulla RC: Transcriptional

regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and

function. Genes Dev. 18:357–368. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu J, Ji L, Ruan Y, Wan Z, Lin Z, Xia S,

Tao L, Zheng J, Cai L, Wang Y, et al: UBQLN1 mediates sorafenib

resistance through regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS

homeostasis by targeting PGC1β in hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6:1902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chang CY, Kazmin D, Jasper JS, Kunder R,

Zuercher WJ and McDonnell DP: The metabolic regulator ERRalpha, a

downstream target of HER2/IGF-1R, as a therapeutic target in breast

cancer. Cancer Cell. 20:500–510. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Deblois G, St-Pierre J and Giguere V: The

PGC-1/ERR signaling axis in cancer. Oncogene. 32:3483–3490. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chen Q, Feng J, Wu J, Yu Z, Zhang W, Chen

Y, Yao P and Zhang H: HKDC1 C-terminal based peptides inhibit

extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma by modulation of

mitochondrial function and EBV suppression. Leukemia. 34:2736–2748.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|