Introduction

Macrophages are essential components of innate

immunity that serve a role in inflammation and host defense via

production of pro- or anti-inflammatory mediators in response to

various stimuli (1). Macrophages

respond to stimulation in a polarized manner. The differentiation

of macrophages to the classic activation (M1) phenotype is

triggered by interferon (IFN)-γ, bacterial lipopolysaccharide

(LPS), interleukin (IL)-1β, or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α),

whereas IL-3 or IL-13 stimulate macrophage differentiation of the

alternative activation phenotype (M2) (2–5). The

M1 phenotype is characterized by the expression of high levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, M2 macrophages express an

anti-inflammatory functional profile and are associated with wound

repair and angiogenesis (6).

Therefore, inflammatory associated diseases may result from a

sustained pro-inflammatory reaction and failure of

anti-inflammatory control mechanisms of macrophages.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a member

of the mammalian activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive

element binding protein (ATF/CREB) family of transcription factors,

is induced in a variety of stressed tissues, including mechanically

and toxin-injured liver tissue, blood-deprived heart tissue and

injured peripheral nerves (7,8). The

transcriptional target of ATF3 varies in different cell types and

conditions, which therefore leads to diverse effects on cell

survival, proliferation and death (9). In neurons, ATF3 is frequently

reported to be a novel neuronal marker of nerve injury, and

induction of ATF3 expression enhances nerve regeneration (10,11).

In cardiac myocytes, ATF3 is a novel cytoprotective factor in

doxorubicin-induced apoptosis (12). Additionally, it is reported that

ATF3 protects renal cells and b-cells against oxidative

stress-induced cell death and apoptosis (13). Therefore, ATF3 is a protective

factor in numerous tissues.

Conversely, ATF3 is an inducible transcriptional

repressor in innate immune cells, which regulates the magnitude and

duration of inducible pro-inflammatory gene expression. Recently,

it was revealed that ATF3 is an important transcriptional regulator

that inhibits the inflammatory response by modulating the

expression of cytokines and chemokines and demonstrated that ATF3

is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling in

macrophages (14). Activation of

TLR4 by LPS induces the expression of ATF3, which subsequently

inhibits the expression of various inflammatory genes induced by

TLR signaling, including IL-6, IL-12β, and TNF-α. Additionally,

ATF3 may modulate the expression levels of IFN-γ in macrophages by

controlling basal and inducible levels of IFN-β, and the expression

of genes downstream of IFN (15).

Therefore, ATF3 is able to negatively regulate transcription of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Understanding the exact

role of ATF3 in macrophages in the context of inflammation is of

primary concern, and may lead to the design of beneficial

therapeutics for inflammatory associated diseases. However, the

effects of ATF3 on recruitment and anti-inflammatory control

mechanisms of macrophages remain to be investigated.

The present study investigated whether ATF3 exerted

anti-inflammatory activities by modulating M1/M2 differentiation of

macrophages. Macrophage migration and markers of M1/M2 macrophages

were tested following overexpression of ATF3. Subsequently, the

underlying mechanism of how overexpression of ATF3 modulates

macrophage migration and M1/M2 polarization was investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells (American Type

Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum,

100 U/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5%

CO2. Wntpalmitoyltransferase inhibitor

(IWP-2,N-(6-M

ethyl-2-benzothiazolyl)-2-[(3,4,6,7-tetrahydro-4-oxo-3-phenylthieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2-yl)thio]-acetamide)

was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany)

and 30 µM was used to treat the cells.

Plasmids and siRNA transfection

For overexpression of ATF3, ATF3 cDNA generated from

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR; The primers used

for the cloning were: 5′-AAAAAGCTTATGATGCTTCAACATCCAGG-3′ and

5′-TTTGAATTCTTAGCTCTGCAATGTTCCTT-3′) was subcloned into a pcDNA™3.1

plasmid (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) between Hind3

and EcoR I sites to express ATF3 in abundance in E. coli

DH5α cells to generate an ATF3 expression plasmid. The third

generation of cells (5×105) were seeded into a 24-well

plate and transfected with the pcDNA-ATF3 or the empty

vector negative control plasmid, psDNA3.1(−), using Lipofectamine

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's protocol at 37°C. After incubation for 48 h, cells

were harvested and ATF3 expression was determined. To knockdown

ATF3 and tenascin (TNC), The third generation of cells

(5×105) were seeded into a 24-well plate and ATF3

siRNA, its negative control (sham), or TNC siRNA and its negative

control siRNA (scramble) were transfected at 37°C using

Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; 0.1

µM siRNA with 20 µl Lipofectamine). Following transfection for 48

h, the transfection medium was exchanged for normal medium and the

cells were used in the subsequent experiments or harvested for ATF3

and TNC expression measurement.

Migration assays

Migration assays were performed using 8 µm pore size

filters within 24-well transwell cell culture chambers with

polycarbonate filters (Corning Life Sciences, Glendale, Arizona,

USA) as previously described (16). A total of 5×105 cells

were transfected with pcDNA-ATF3 or the psDNA3.1(−), and

subsequently seeded into the upper chamber of the transwell.

Transwells were either uncoated (5 µm pore size) or coated with

Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) diluted 1:50 (8

µm pore size). As a chemoattractant, monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 (MCP-1; 100 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis,

MN, USA) was present in the lower wells. After incubation for 18 h

at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells in the lower chambers that

passed through the filter were counted under a Carl Zeiss Primo

Vert microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

Western blotting

Total protein was lysed using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Nantong, China). After determining the protein

concentration with a Bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China), ~30 µg of proteins were

loaded onto 10% gels and subjected to SDS-PAGE, prior to transfer

onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, membranes were blocked for 1 h in

a blocking solution (5% skimmed milk, 0.05% Tween 20) at 37°C and

probed with the following primary antibodies: Mouse anti-β-catenin

(2698; 1:1,000), rabbit anti-c-myc 9402; 1:1,000) and anti-cyclin

D1 (2292; 1:1,000; all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.,

Danvers, MA, USA), and mouse anti-ATF3 (sc81189; 1:500), rabbit

anti-TNC (sc20932; 1:1,000), and mouse anti-β-actin (sc130300;

1:1,000; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA)

at 4°C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit

anti-mouse (sc358917; 1:3,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or goat

anti-rabbit (RPN4301; 1:5,000; GE Healthcare Life Sciences,

Chalfont, UK) secondary antibodies were added to the membranes for

1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were detected using the

Enhanced Chemiluminescence substrate detection system (Amersham

Biosciences Corporation, Piscataway, USA). The intensities of the

resulting bands were quantified using Carestream Molecular Imaging

software version 5.0.2.30 (Carestream Health, Woodbridge, CT, USA)

on a Gel Logic 2000 imaging system (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Reverse transcription PCR was performed on an

Applied Biosystems® 7500 fast sequence detection system

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly,

total RNA was extracted using TRIzol® reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse

transcribed using the MMLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green

reagent (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Cycling conditions were

as follows: An initial predenaturation step at 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing

at 58°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec. The experiment

was performed three times. The relative expression levels of the

target genes were calculated using the 2−∆∆Cq method

(17) and normalized to GAPDH.

Forward and reverse sequences of the primers used for all target

genes and GAPDH are listed in Table

I.

| Table I.Primers used. |

Table I.

Primers used.

| Gene | Primer

sequences |

|---|

| MCP-1 | F:

5′-TCAGCCAGATGCAGTTAACGC-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-TGGATGCATTAGCTTCAGATTTACG-3′ |

| CD16 | F:

5′-GACAGTGTGACTCTGAAG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-GCACCTGTACTCTCCAC-3′ |

| iNOS | F:

5′-CCCTTCCGAATTTCTGGCAGCAGC-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-GGCTGTCAGAGCCTCGTGGCTTTGG-3′ |

| TNF-19α | F:

5′-TTGACCTCAGCGCTGAGTTG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-CCTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC-3′ |

| Arg-1 | F:

5′-CAGAAGAATGGAAGAGTCAG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-CAGATATGCAGGGAGTCACC-3′ |

| CD163 | F:

5′-ATGGGTGGACACAGAATGGTT-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-CAGGAGCGTTAGTGACAGCAG-3′ |

| Mrc-1 | F:

5′-TCTTTTACGAGAAGTTGGGGTCAG-3′ |

|

| F:

5′-ATCATTCCGTTCACAGAGGG-3′ |

| PPARγ | R:

5′-GGAGATCTCCAGTGATATCGACCA-3′ |

|

| F:

5′-ACGGCTTCTACGGATCGAAACT-3′ |

| TNC | R:

5′-GTTTGGAGACCGCAGAGAAGAA-3′ |

|

| F:

5′-TGTCCCCATATCTGCCCATCA-3′ |

| GAPDH | R:

5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTC-3′ |

|

| F:

5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′ |

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's

t-test. Experiments were repeated three times. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference

analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA).

Results

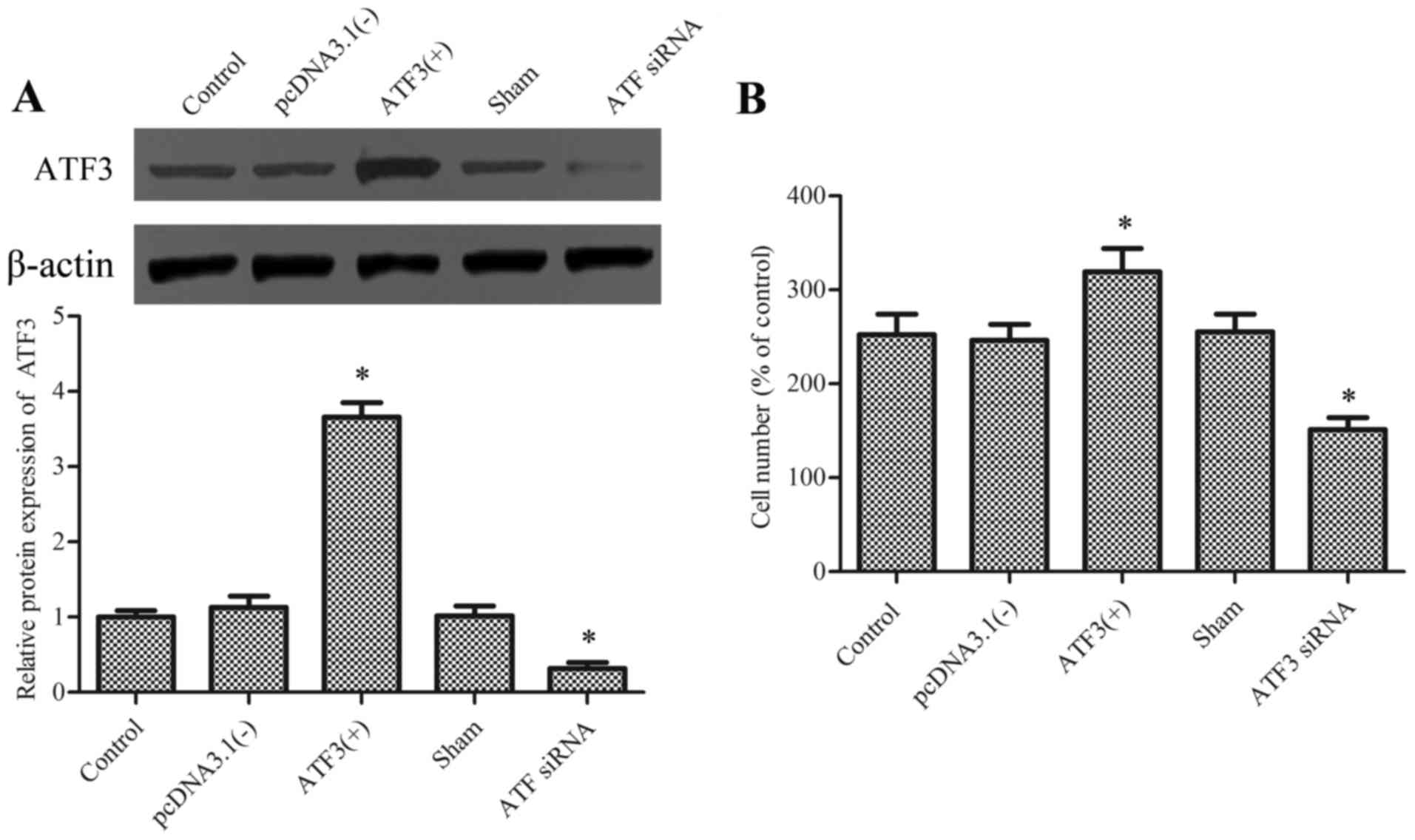

Overexpression of ATF3 promotes the

migration of macrophages

To examine whether ATF3 regulates macrophage

migration, the pcDNA-ATF3 plasmid and ATF3 siRNA were

utilized to overexpress and knockdown the ATF3 protein,

respectively (Fig. 1A). Cell

viability was tested using an MTT assay and the ATF3 siRNA had no

effect on cellular viability (data not show).

Subsequently, migration of macrophages was evaluated

in the presence of chemotaxis-inducing agent MCP-1. Results

demonstrated that overexpression of ATF3 significantly promoted the

migration of macrophages compared with the empty vector

[pcDNA3.1(−)], whereas knockdown of ATF3 significantly reduced

migration compared with the sham group and the difference between

the control and sham group were not significant (Fig. 1B).

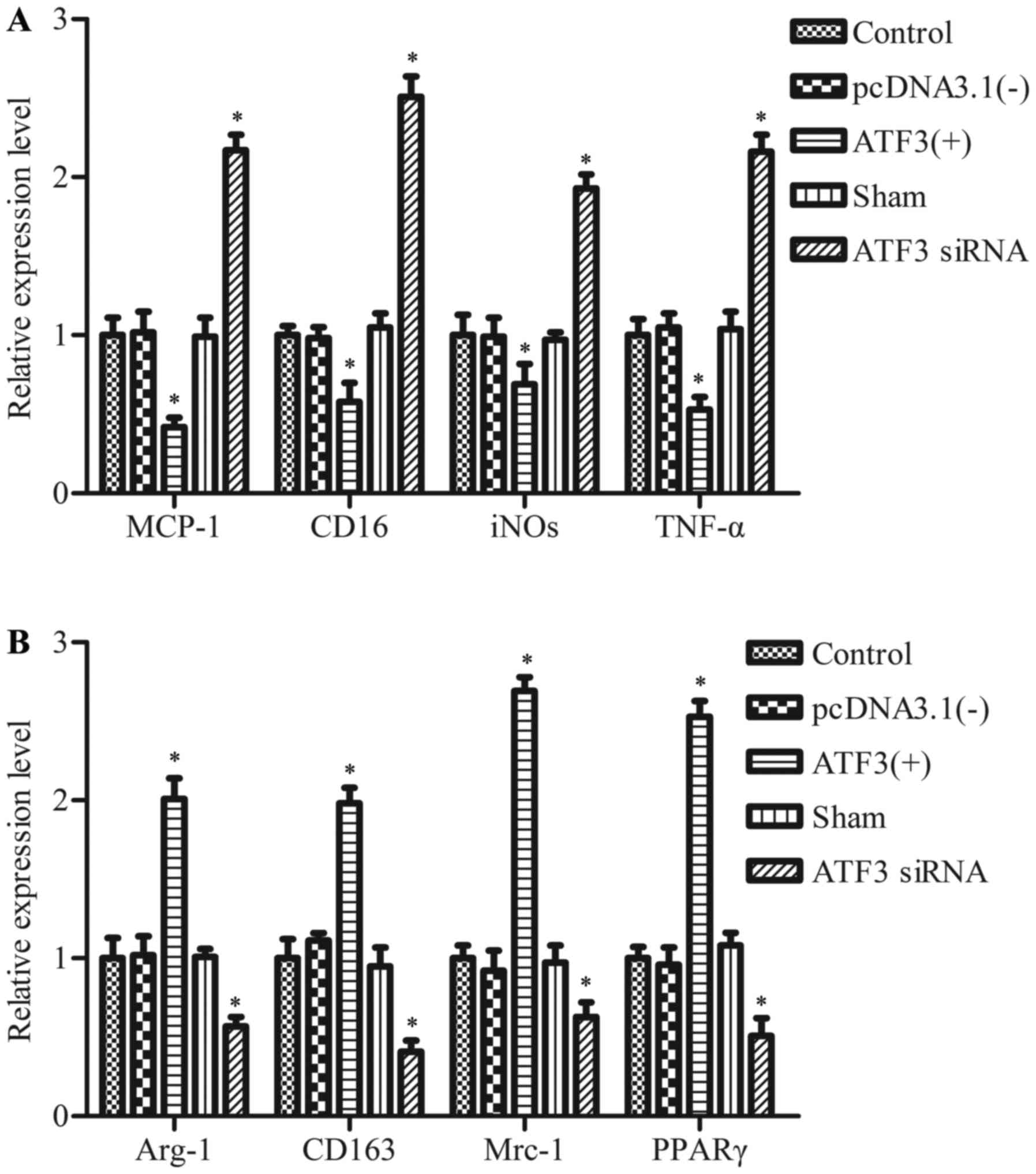

Overexpression of ATF3 promotes

macrophage differentiation of the M2 phenotype

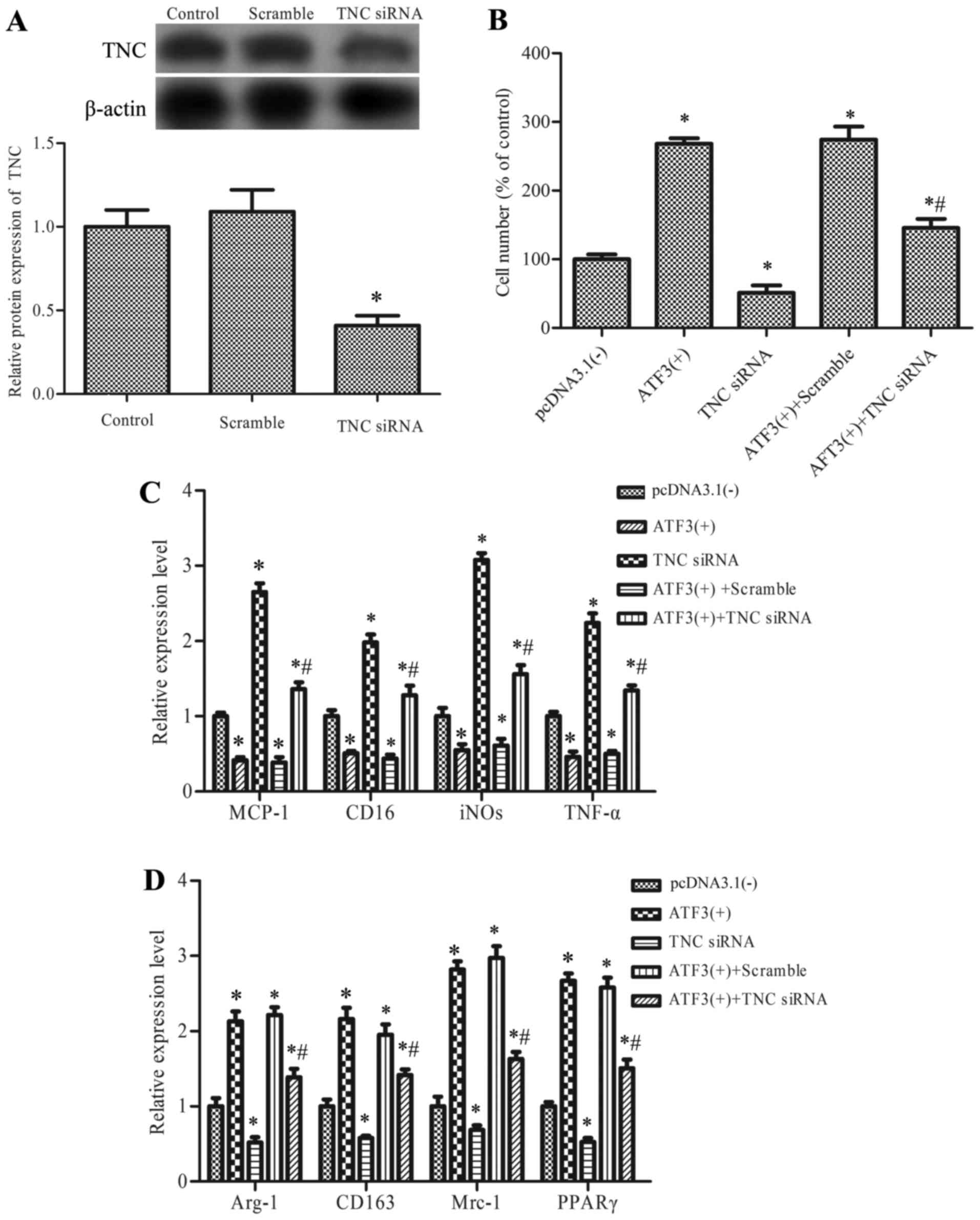

To determine the function of ATF3 in the process of

macrophage polarization, markers of the M1 phenotype [MCP-1,

inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cluster of differentiation

(CD) 16 and TNF-α] and the M2 phenotype [CD163, mannose receptor C

type 1 (Mrc-1), arginase 1 (Arg-1) and peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)] were measured. Results

revealed that the mRNA expression levels of M1-associated genes

encoding MCP-1, iNOS, CD16 and TNF-α, were reduced following

transfection with pcDNA-ATF3 compared with the empty vector

control group, and were enhanced following transfection with

ATF3 siRNA compared with the sham group (P<0.05; Fig. 2A). In addition, overexpression of

ATF3 in RAW 264.7 cells enhanced the expression levels of

the genes encoding CD163, Mrc-1, Arg-1 and PPARγ compared with the

empty vector control group, and these levels were then reduced by

knockdown of ATF3 compared with the sham group (P<0.05;

Fig. 2B). These results suggested

that ATF3 promotes polarization of M2 in macrophages.

| Figure 2.Effect of ATF3 overexpression on the

characterization of M1 or M2 macrophage polarization. RAW 264.7

cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 (−), pcDNA-ATF3 (ATF3 (+)),

ATF3 siRNA or negative control siRNA (sham) for 48 h. mRNA

expression levels of markers of the (A) M1 state and (B) M2 state

were determined using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

of the three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. sham or

pcDNA3.1 (−). ATF3, activating transcription factor 3; siRNA, short

interfering RNA; pcDNA3.1(−), empty vector; MCP-1, monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1; iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase;

CD, cluster of differentiation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor;

Mrc-1, mannose receptor C type 1; Arg-1, arginase 1; PPARγ,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. |

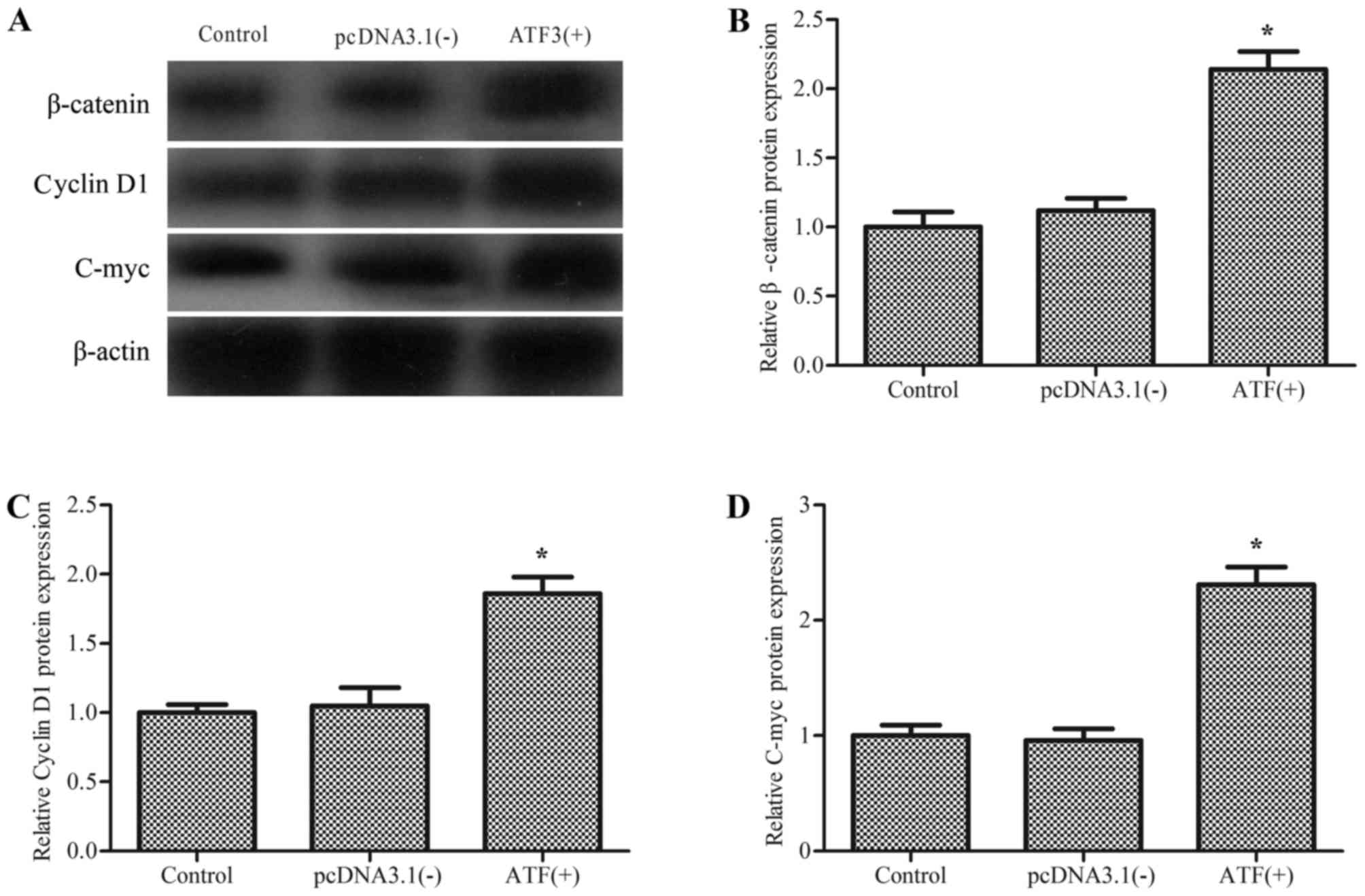

Overexpression of ATF3 activates the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

β-catenin, encoded by the CTNNB1 gene, is a

transcriptional co-activator and serves a role in the inflammatory

response (18,19). To explore the mechanism of ATF3

regulation of macrophage migration and M2 polarization, the effect

of ATF3 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling was investigated. As

demonstrated in Fig. 3,

overexpression of ATF3 resulted in enhanced expression levels of

β-catenin and its target genes cyclin D1 and c-myc compared with

cells transfected with the empty vector control. This suggested

that overexpression of ATF3 induced the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in macrophages.

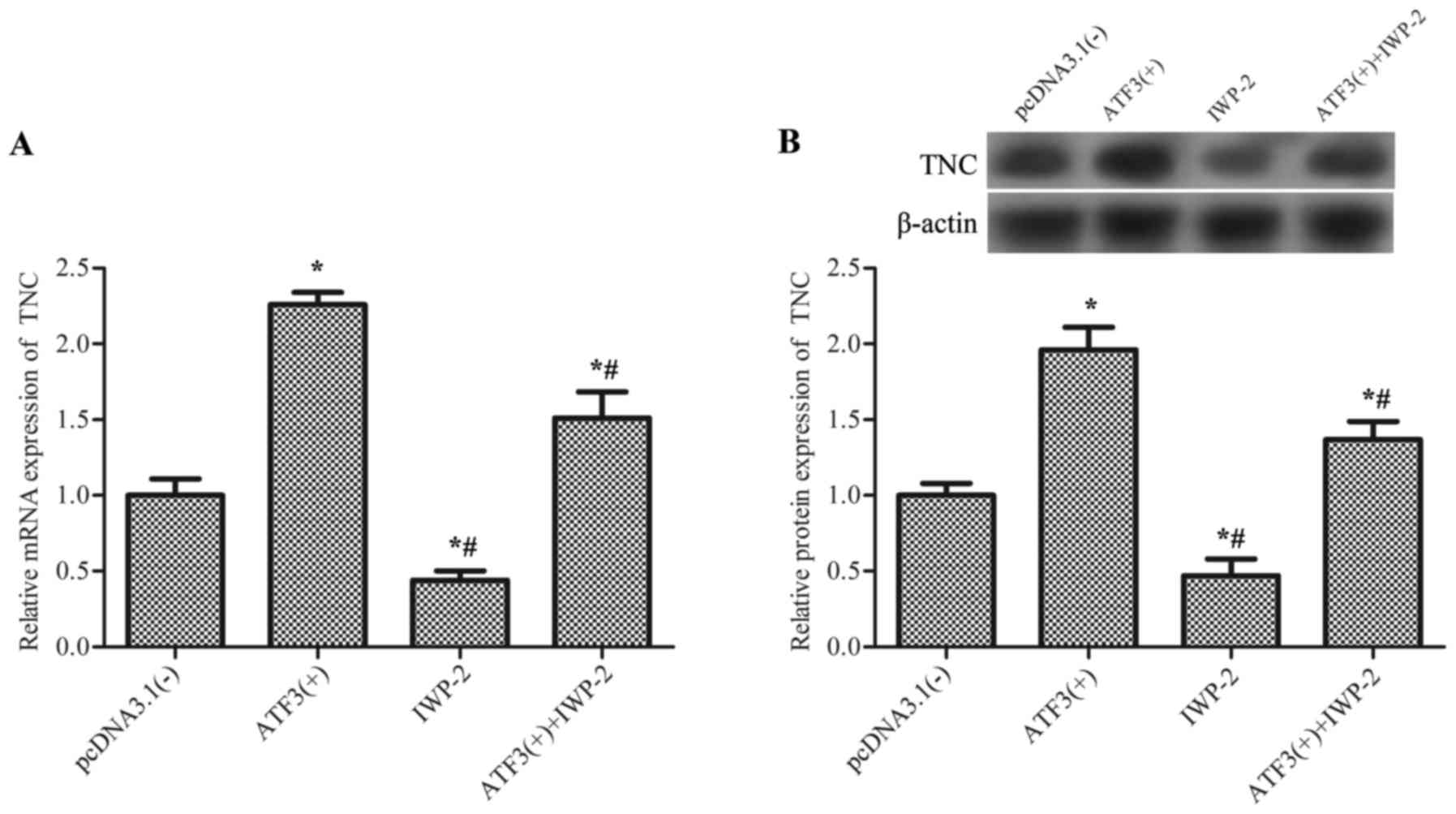

TNC is activated by ATF3 via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

The gene encoding TNC is a canonical Wnt target

(20), and serves a role in

macrophage behavior and function (21,22).

Therefore, the association between ATF3 and TNC was investigated.

Results revealed that overexpression of AFT3 significantly

upregulated the mRNA expression levels of TNC (Fig. 4A) and the TNC protein (Fig. 4B) compared with the empty vector

control, and this effect was partially inhibited by IWP-2, an

inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which suggested that ATF3

activates TNC via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

ATF3 regulates the migration and

polarization of M2 macrophages by upregulating TNC expression

levels

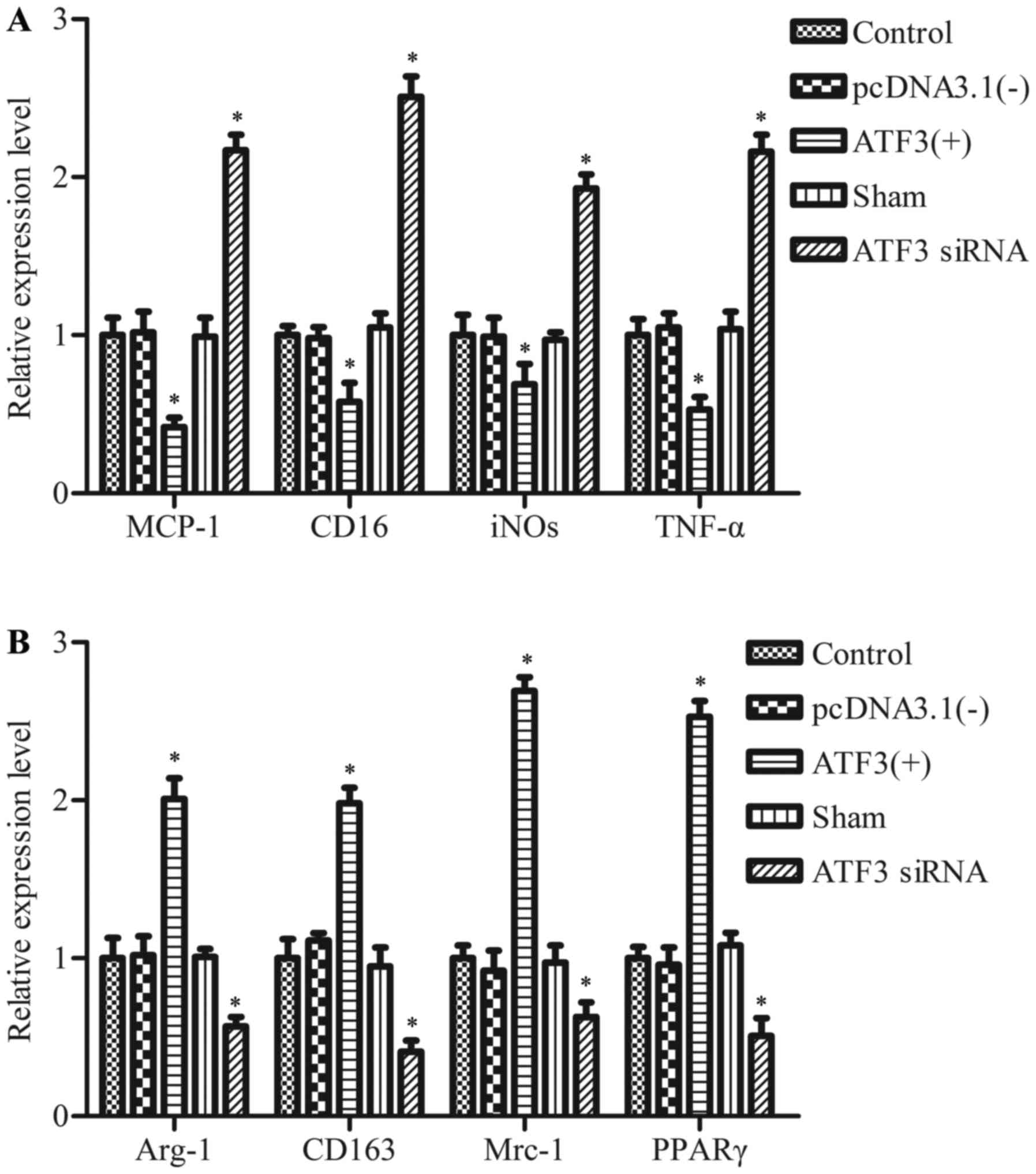

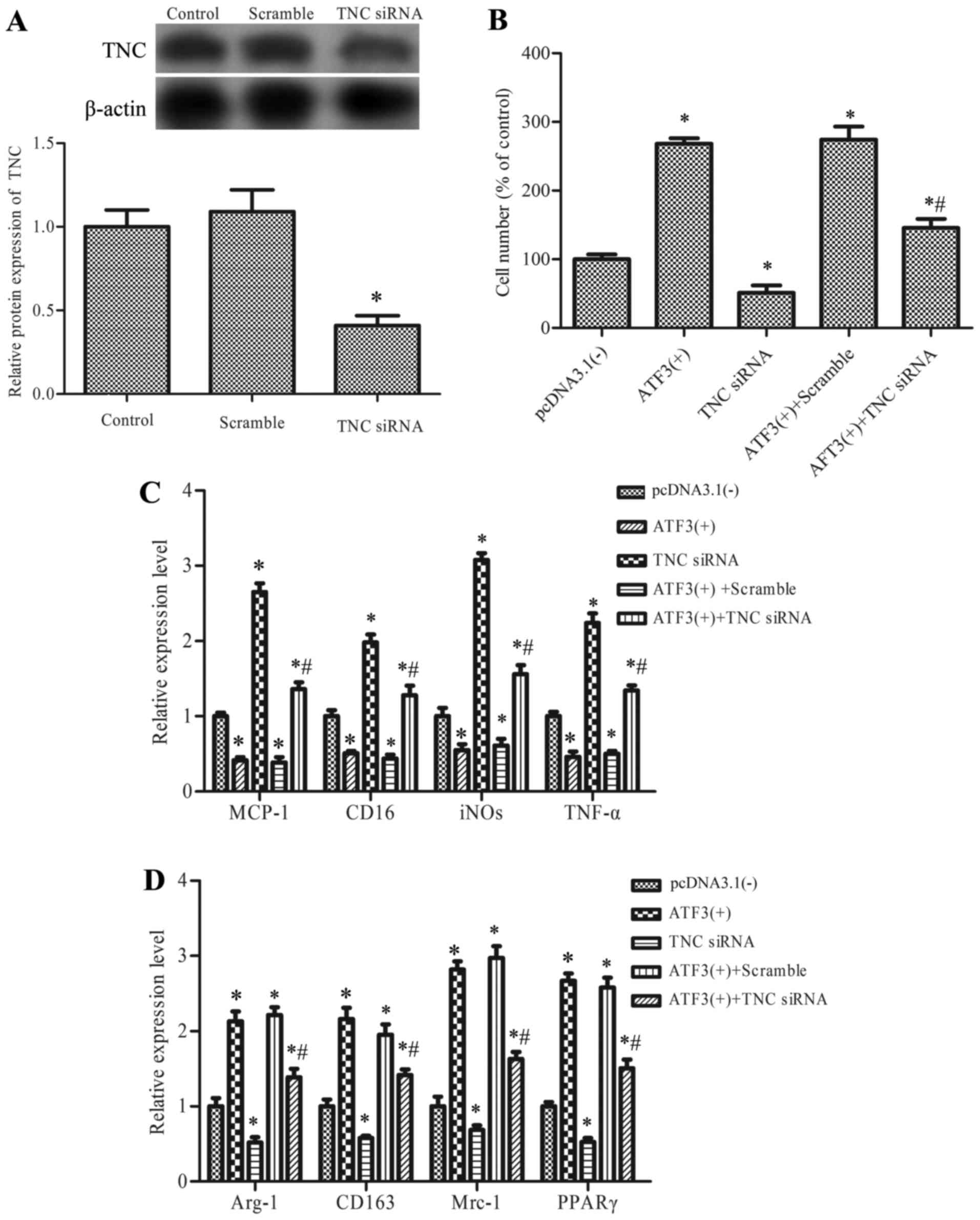

To further investigate the role of TNC in

ATF3-mediated macrophage migration and polarization, cells were

transfected with pcDNA-ATF3 and knockdown of TNC using

TNC siRNA (Fig. 5A), prior

to determining cell viability and the expression levels of

M2-associated genes. Results revealed that transfection of

pcDNA-ATF3 significantly promoted macrophage migration

compared with the empty vector control, whereas transfection with

TNC siRNA reduced the migration induced by pcDNA-ATF3

compared with the scrambled control group (Fig. 5B). In addition, the expression

levels of genes associated with the M1 phenotype that were

downregulated by pcDNA-ATF3 were enhanced by transfection

with TNC siRNA (Fig. 5C),

whereas M2 gene expression levels that were upregulated by

pcDNA-ATF3 were inhibited by TNC siRNA (Fig. 5D).

| Figure 5.The role of TNC in the regulation of

ATF3 on macrophage migration and M1/M2 polarization. (A) RAW 264.7

cells were transfected with TNC siRNA or negative control

siRNA (scramble). Cells without transfect vector were defined as

the control group. TNC protein expression levels were determined

using western blot and densitometric analysis. Cells were treated

with pcDNA-ATF (ATF3 (+)), TNC siRNA, ATF3(+)

+scramble or ATF3(+) +TNC siRNA. Cells without transfect

vector were defined as the control group. (B) macrophage migration,

(C) mRNA expression of markers of M1 state and (D) mRNA expression

of markers of the M2 state, were measured. Data are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation of the three independent experiments.

*P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1(−) and #P<0.05 vs. ATF3(+) +

scramble. ATF3, activating transcription factor 3; TNC, tenascin;

siRNA, short interfering RNA; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; CD, cluster of

differentiation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor; Mrc-1, mannose

receptor C type 1, Arg-1; arginase 1; PPARγ, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ. |

These results suggested that ATF3 regulates

macrophage migration and M2 polarization, in part, by upregulation

of TNC.

Discussion

Macrophages are primary producers of

pro-inflammatory mediators and the migration of macrophages from

the circulation into injured tissues serves a crucial role in wound

healing. Macrophage polarization is closely associated with

homeostatic tissue remodeling, resolution of inflammation,

remodeling and tissue repair (23). ATF3 is a transcriptional modulator,

induced by LPS and the TLR-dependent injury response, that

negatively regulates numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and

chemokines in macrophages (24).

Previous reviews have reported that ATF3 modulates the expression

levels of a number of inflammatory genes (25). Therefore, the present study

investigated the effect of ATF3 on macrophage migration and

polarization.

Migration of macrophages serves a role in the onset

and course of inflammation. Chen et al (26) revealed that the epithelium-derived

exosomal ATF3 inhibited the expression of monocyte chemoattractant

protein 1 and macrophage migration, and Zmuda et al

(27) suggested that ATF3 knockout

islets inhibited macrophage recruitment in vivo. The present

study revealed that overexpression of ATF3 promoted M2 marker

expression and suppressed the expression levels of M1-associated

markers. This suggested that ATF3 may reverse M1-polarized

macrophages to M2 phenotypes, and that the ATF3-mediated

anti-inflammatory function is closely associated with macrophage

phenotype. It is evident that ATF3 serves an important role in

injury in numerous tissues, and it was revealed that ATF3 may

protect against acute kidney and lung injury (28,29).

M2 macrophages exhibit immunoregulatory functions including defense

against infection, promotion of angiogenesis and wound healing

(30). The results of the present

study suggested that ATF3 may be a protective regulator for injured

tissues by promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages.

ATF3 serves a role in the cellular adaptive-response

network in response to signals perturbing homeostasis (25). Previous data has suggested that

ATF3 activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in human breast

cancer cells (31), which concurs

with the results of the present study, as overexpression of ATF3

activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in macrophages. Various

components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway are involved in

the inflammatory response, including in inflammatory conditions in

humans and in the LPS-treated macrophage cell line (32). Wnt upregulates the expression

levels of TNC (20), which is a

large hexameric extracellular matrix glycoprotein that is highly

expressed during embryonic development, cancer invasion and wound

healing. It has been reported that TNC may be expressed in

macrophages and regulates their behavior and function (21,22).

TNC has been suggested to act as pro-inflammatory modulator in

various diseases (33,34) and accelerates macrophage migration

(35). The results of the present

study demonstrated that overexpression of ATF3 upregulated TNC

expression levels via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. In

addition, the present study demonstrated that TNC was an effector

for ATF3 in modulating macrophage migration and M2

polarization.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that

overexpression of ATF3 in macrophage cells promoted their migration

to chemotaxis-inducing agent MCP-1, and influenced the M1/M2

phenotype. These results emphasize that ATF3 expression levels

affect macrophages, partially by upregulating TNC via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The present study may provide an

insight into the positive regulation of ATF3 on macrophage

migration, and tissue regeneration via modulation of the M2

macrophage.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81001196) and

Shaanxi Social Development for Science and Technology Project

(grant no. 2016SF-330).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ATF3

|

activating transcription factor 3

|

|

TNC

|

tenascin

|

|

IFN-γ

|

interferon-γ

|

|

TNF-α

|

tumor necrosis factor-α

|

|

ATF/CREB

|

activating transcription factor/cAMP

responsive element binding protein

|

|

TLR4

|

Toll-like receptor 4

|

References

|

1

|

Gordon S and Martinez FO: Alternative

activation of macrophages: Mechanism and functions. Immunity.

32:593–604. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A and

Locati M: Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci.

13:453–461. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kuroda E, Ho V, Ruschmann J, Antignano F,

Hamilton M, Rauh MJ, Antov A, Flavell RA, Sly LM and Krystal G:

SHIP represses the generation of IL-3-induced M2 macrophages by

inhibiting IL-4 production from basophils. J Immunol.

183:3652–3660. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Odegaard JI and Chawla A: Mechanisms of

macrophage activation in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat

Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 4:619–626. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Porcheray F, Viaud S, Rimaniol AC, Léone

C, Samah B, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Dormont D and Gras G: Macrophage

activation switching: An asset for the resolution of inflammation.

Clin Exp Immunol. 142:481–489. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gordon S: Alternative activation of

macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 3:23–35. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hai T and Hartman MG: The molecular

biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription

factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription

factors: Activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis.

Gene. 273:1–11. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE

and Sivaprasad U: ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 7:321–335.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thompson MR, Xu D and Williams BR: ATF3

transcription factor and its emerging roles in immunity and cancer.

J Mol Med (Berl). 87:1053–1060. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tsujino H, Kondo E, Fukuoka T, Dai Y,

Tokunaga A, Miki K, Yonenobu K, Ochi T and Noguchi K: Activating

transcription factor 3 (ATF3) induction by axotomy in sensory and

motoneurons: A novel neuronal marker of nerve injury. Mol Cell

Neurosci. 15:170–182. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Averill S, Michael GJ, Shortland PJ,

Leavesley RC, King VR, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB and Priestley JV:

NGF and GDNF ameliorate the increase in ATF3 expression which

occurs in dorsal root ganglion cells in response to peripheral

nerve injury. Eur J Neurosci. 19:1437–1445. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nobori K, Ito H, Tamamori-Adachi M, Adachi

S, Ono Y, Kawauchi J, Kitajima S, Marumo F and Isobe M: ATF3

inhibits doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes: A novel

cardioprotective role of ATF3. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 34:1387–1397.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yoshida T, Sugiura H, Mitobe M, Tsuchiya

K, Shirota S, Nishimura S, Shiohira S, Ito H, Nobori K, Gullans SR,

et al: ATF3 protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J

Am Soc Nephrol. 19:217–224. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nguyen CT, Kim EH, Luong TT, Pyo S and

Rhee DK: TLR4 mediates pneumolysin-induced ATF3 expression through

the JNK/p38 pathway in Streptococcus pneumoniae-infected RAW 264.7

cells. Mol Cells. 38:58–64. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Labzin LI, Schmidt SV, Masters SL, Beyer

M, Krebs W, Klee K, Stahl R, Lütjohann D, Schultze JL, Latz E and

De Nardo D: ATF3 is a key regulator of macrophage IFN responses. J

Immunol. 195:4446–4455. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lighvani S, Baik N, Diggs JE, Khaldoyanidi

S, Parmer RJ and Miles LA: Regulation of macrophage migration by a

novel plasminogen receptor Plg-R KT. Blood. 118:5622–5630. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim JS, Yeo S, Shin DG, Bae YS, Lee JJ,

Chin BR, Lee CH and Baek SH: Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta and

beta-catenin pathway is involved in toll-like receptor 4-mediated

NADPH oxidase 1 expression in macrophages. FEBS J. 277:2830–2837.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kraus C, Liehr T, Hülsken J, Behrens J,

Birchmeier W, Grzeschik KH and Ballhausen WG: Localization of the

human beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) to 3p21: A region implicated in

tumor development. Genomics. 23:272–274. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pedersen EA, Scannell CA, Menon R and

Lawlor ER: Tenascin C is a canonical Wnt target gene in Ewing

sarcoma and its expression is potentiated by R-spondin. Cancer Res.

74:3085. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kimura T, Tajiri K, Hlroe M, et al:

Tenascin-C regulates macrophage behavior during tissue repair after

myocardial infarction in mouse model. Molecular Biology Of The

CellAmer Soc Cell Biology. Bethesda, MD: pp. 20814–2755. 2014

|

|

22

|

Shimojo N, Hashizume R, Kanayama K, Hara

M, Suzuki Y, Nishioka T, Hiroe M, Yoshida T and Imanaka-Yoshida K:

Tenascin-C may accelerate cardiac fibrosis by activating

macrophages via the integrin αVβ3/nuclear factor-κB/interleukin-6

axis. Hypertension. 66:757–766. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica

A and Locati M: Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue

repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 229:176–185. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG,

Korb M, Roach JC, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H and Aderem A: Systems

biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of

Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 441:173–178. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hai T, Wolford CC and Chang YS: ATF3, a

hub of the cellular adaptive-response network, in the pathogenesis

of diseases: Is modulation of inflammation a unifying component?

Gene Expr. 15:1–11. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen HH, Lai PF, Lan YF, Cheng CF, Zhong

WB, Lin YF, Chen TW and Lin H: Exosomal ATF3 RNA attenuates

pro-inflammatory gene MCP-1 transcription in renal

ischemia-reperfusion. J Cell Physiol. 229:1202–1211. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zmuda EJ, Qi L, Zhu MX, Mirmira RG,

Montminy MR and Hai T: The roles of ATF3, an adaptive-response

gene, in high-fat-diet-induced diabetes and pancreatic beta-cell

dysfunction. Mol Endocrinol. 24:1423–1433. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li HF, Cheng CF, Liao WJ, Lin H and Yang

RB: ATF3-mediated epigenetic regulation protects against acute

kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 21:1003–1013. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shan Y, Akram A, Amatullah H, Zhou DY,

Gali PL, Maron-Gutierrez T, González-López A, Zhou L, Rocco PR,

Hwang D, et al: ATF3 protects pulmonary resident cells from acute

and ventilator-induced lung injury by preventing Nrf2 degradation.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 22:651–668. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Murray PJ and Wynn TA: Protective and

pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol.

11:723–737. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yan L, Della Coletta L, Powell KL, Shen J,

Thames H, Aldaz CM and MacLeod MC: Activation of the canonical

Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ATF3-induced mammary tumors. PLoS One.

6:e165152011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lee H, Bae S, Choi BW and Yoon Y:

WNT/β-catenin pathway is modulated in asthma patients and

LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophage cell line. Immunopharmacol

Immunotoxicol. 34:56–65. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Carey WA, Taylor GD, Dean WB and Bristow

JD: Tenascin-C deficiency attenuates TGF-ß-mediated fibrosis

following murine lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

299:L785–L793. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, Inglis

J, Trebaul A, Chan E, Drexler S, Sofat N, Kashiwagi M, Orend G, et

al: Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4

that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint

disease. Nature Med. 15:774–780. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shimojo N, Hashizume R, Kanayama K, Suzuki

Y, Hara M, Nishioka T, Yoshida T and Yoshida KI: A functional role

of tenascin-C in angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis.

Circulation. 130:A96322014.

|