Introduction

Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) has been used as a

treatment for high body temperatures, headaches and muscle pain for

more than a century. Accumulating evidence from large-scale

epidemiological studies, animal models and in vitro

experiments suggest that regular use of aspirin may reduce the risk

of cancer by inducing cancer cell apoptosis (1–3).

Findings of recent studies have indicated that aspirin is able to

block NF-κB activation (4,5), induce iNOS to produce NO (6,7),

inhibit COX-2 (8), ErbB2 (9) and Bcl-2 (10) and acetylate or phosphorylate p53

(3,11), inducing cell apoptosis or

proliferation inhibition. However, the cell pathways through which

aspirin exerts its anticancer effects are not well understood and

require further elucidation.

Apoptosis in anticancer strategies is a multi-step

process involving the activation of caspases, a family of cysteine

proteases. There are two types of apoptotic caspases: initiators

(caspases-2, -8, -9 and -10) and effectors (caspases-3, -6 and -7).

Initiator caspases cleave inactive pro-forms of effector caspases

to activate them and then effector caspases catalyze the specific

cleavage of other key cellular proteins to trigger the apoptotic

process. In aspirin-induced cancer cell apoptosis, caspase-3 and

other caspase family members were previously demonstrated to be

crucial upregulated factors (4,10,12,13).

The transcription factor AP-2 family, which consists

of AP-2α, β, γ, δ and ɛ, regulates the transcription of numerous

genes involved in mammalian development, the cell cycle, cell

proliferation, apoptosis and carcinogenesis by binding to the

genes’ promoter regions (14,15).

Several reports have suggested that AP-2α and AP-2γ are marked

functional activators for ErbB2 overexpression in mammary carcinoma

(16,17), while ErbB2 overexpression is

associated with increased tumorigenicity, enhanced metastasis, poor

prognosis and decreased chemosensitivity (18).

The aim of the present study was to demonstrate

whether aspirin induces apoptosis in MDA-MB-453 cells by

upregulating caspase-3 expression and activity. Caspase-3 was found

to be directly and negatively regulated by AP-2α, which is degraded

following aspirin treatment. The caspase-3 pathway appeared to

participate in aspirin-induced apoptosis of MDA-MB-453 cells

through the downregulation of AP-2α.

Materials and methods

Plasmids, siRNA and reagents

The full-length coding region of AP-2α was cloned

into a pCMV-Myc plasmid (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The

promoter region (nt −799 to nt +93 from the transcription start

codon) of caspase-3 was generated by PCR (19) and cloned into the luciferase

reporter plasmid pTAL-luc (Clontech), denoted pTAL-luc-caspase-3.

The primer sequences used were: 5′-CGGCTAGCC TTTTTCCTCATGATGTT-3′

(forward) and 5′-GAAGATC TGCCTCCTCATACCTTCTAC-3′ (reverse). Single

or double AP-2α binding site mutants were created by site-directed

mutation and denoted as pTAL-luc-M1, -M2 and -M3. Two specific

small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against AP-2α were purchased from

GenePharma Co. (Shanghai, China). The two siRNA sense sequences are

5′-UUUCUCAACCGACAA CAUUtt-3′ and 5′-CGAAGUCUUCUGUUCAGUUtt-3′.

Aspirin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and

solubilized in water.

Cell culture, transfection and

treatment

MDA-MB-453 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco-BRL,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Gibco-BRL), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were

cultured to 80% confluence and transiently transfected using

Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Aspirin treatment proceeded at 90%

confluence continuously in low-serum (0.5% FBS) medium for 24

h.

Cell proliferation assay

Inhibition of cell proliferation was evaluated by

the MTT assay (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. Briefly, MDA-MB-453 cells were placed in 24-well

plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well in 450-μl medium

and 24 h after attachment, the cells were treated with 0–20 mM

aspirin for a further 24 h. Then, 50 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml in PBS)

solution were added to each well and the cells were incubated for a

further 4 h, followed by the addition of 150 μl of dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich)/well. The cells were left for 30

min at room temperature to allow color development. Absorbance

values were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) reader (Model 680; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 570

nm.

Flow cytometric analysis of

apoptosis

Apoptotic and total dead cells were stained by the

Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) detection kit (Bender

MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. In brief, MDA-MB-453 cells (1×105

cells/well) were washed with 1X Annexin V binding buffer and

stained with Annexin V (5 μl) and PI (10 μl) for 15 min at room

temperature in the dark. Following the addition of 400 μl of

binding buffer, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur;

BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Caspase-3 activity assay

The activity of caspase-3 was determined using the

Caspase-3 Activity Detection kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Haimen, China). To evaluate the activity of

caspase-3, cell lysates were prepared following the designated

treatment. Assays were performed in 96-well plates by incubating 10

μl protein of cell lysate/sample with 10 μl caspase-3 substrate

(Ac-DEVD-pNA, 2 mM) in 80 μl of reaction buffer [1% NP-40, 20 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 137 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol] at 37°C for 5 h.

Absorbance values were determined using an enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Model 680; Bio-Rad) at 405

nm.

The detailed procedure including the standard curve

preparation was described in the manufacturer’s instructions. All

the experiments were performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction, semi-quantitative RT-PCR

and real-time PCR

Total RNA extraction, RT- and real-time PCR were

performed as described previously (9). The real-time PCR primers used were:

AP2α 5′-CTCAACCGACAACATTCC-3′ (forward) and

5′-CGGTGAACTCTTTGCATATC-3′ (reverse) (20); caspase-3 5′-CAGTGGAGGCCGACTTC

TTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGCACAAAGCGACTGGAT-3′ (reverse) (21). For semi-quantitative RT-PCR, DNA

was amplified under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C

for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for

30 sec and the number of cycles for amplification was 21–25. PCR

products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and

visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease

inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Equal amounts of protein were separated

on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF

membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking, the PVDF

membranes were washed three times for 10 min with TBST at room

temperature and incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature with

TBST-diluted primary antibodies, anti-AP2α (1:500) and

anti-caspase-3 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz,

CA, USA). Following extensive washing, the membranes were further

incubated with the secondary peroxidase-labeled antibodies

(1:2,000) in 5% non-fat dry milk/TBST for 1 h. The membranes were

again washed three times for 10 min with TBST at room temperature,

immunoreactivity was visualized using the enhanced

chemiluminescence ECL kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA)

and the membranes were exposed to Kodak film. The membranes were

then stripped and reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1,000; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) as a loading control.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

The ChIP assay was performed using the EZ ChIP™ kit

(Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as

previously described (22). The

antibodies used included anti-AP2α antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) and normal rabbit IgG (Millipore). The

caspase-3 promoter ChIP primers used in the present study were:

5′-AACACAGCATGCGTGGACCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCTCCTCATACCTTCTAC-3′

(reverse).

Luciferase reporter assays

MDA-MB-453 cells were seeded at 5×105

cells/well in 12-well plates and transfected at 80% confluence

using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. After 24 h of transfection, the luciferase activity

was measured using the luciferase reporter assay system (Promega,

Madison, WI, USA).

Statistical analysis

Results of bar graphs were expressed as the mean ±

SD obtained from three independent experiments. Statistical

differences were evaluated using the Student’s t-test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate statistically significant

differences.

Results

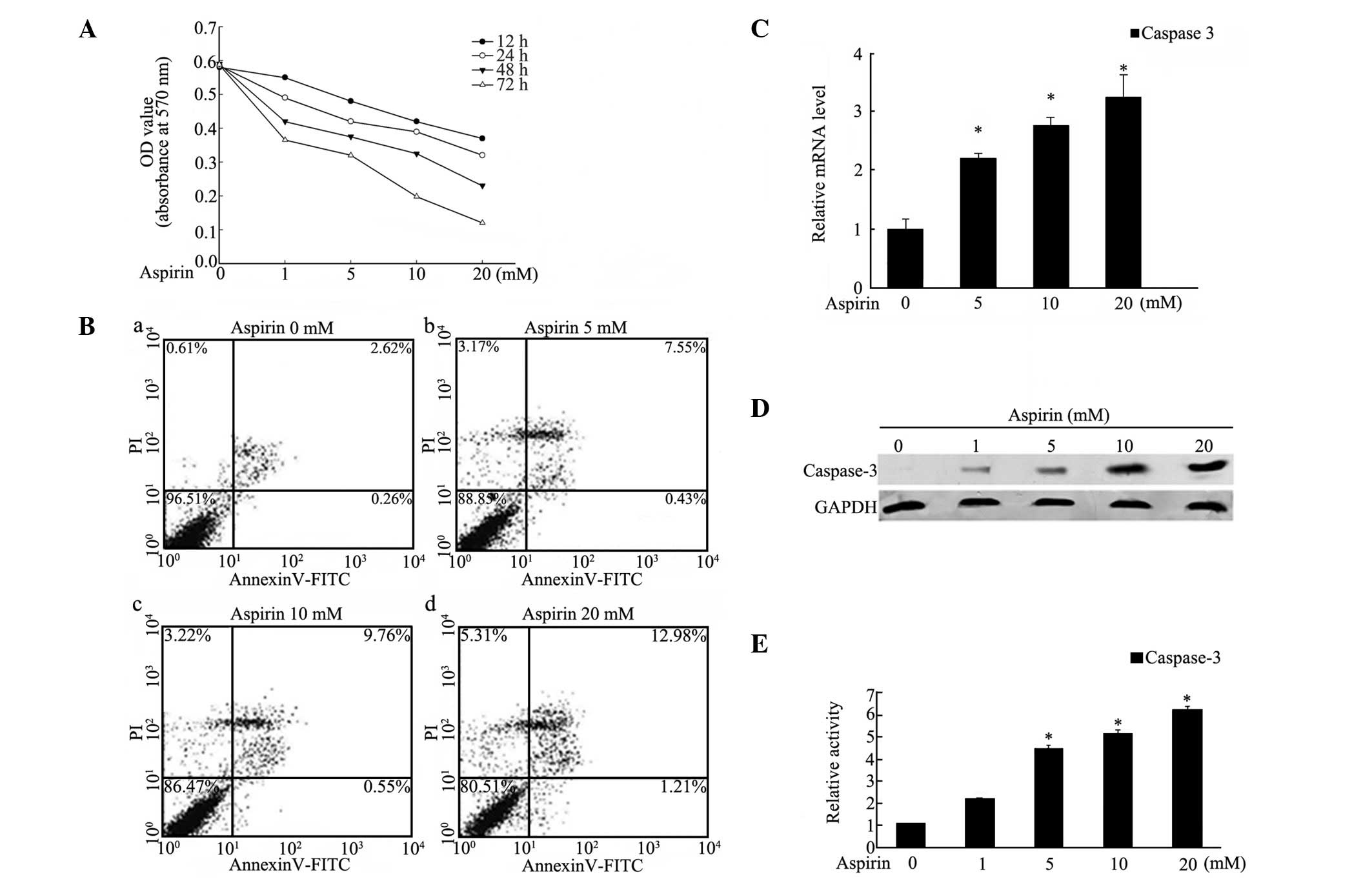

Aspirin induced apoptosis and upregulated

the expression and activity of caspase-3 in MDA-MB-453 cells

To evaluate the effect of aspirin on the

proliferation of human MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cells, the MTT

assay was used and the results indicated that aspirin decreased

cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). A significant antiproliferative

effect of aspirin appeared following treatment with 20 mM for

various time periods. The percentage of viable cells decreased to

62.38% under treatment with 20 mM of aspirin for 24 h and then to

18.97% after 72 h treatment, compared with the controls. To

investigate whether aspirin induced cell apoptosis and death, cells

were treated with various concentrations (0–20 mM) of aspirin for

24 h and then subjected to Annexin V/PI-based flow cytometry.

Exposure to aspirin significantly affected apoptosis in the

MDA-MB-453 cells (Fig. 1B). When

exposed to 20 mM aspirin for 24 h, the percentage of apoptotic

cells reached 12.98%, notably higher than the untreated cells. As

other studies have described upregulation of the expression and

activity of caspase-3 in gastric, cervical and prostate cancer cell

apoptosis (12,13,23,24),

the expression of caspase-3 was investigated by real-time PCR and

western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1C

and D, the mRNA and protein levels of caspase-3 were increased

in a dose-dependent manner when exposed to 0–20 mM aspirin for 24

h. Moreover, to investigate the expression of activated caspase-3,

the activity of caspase-3 was evaluated and the results showed that

activity was increased in a similar dose-dependent manner in

response to aspirin treatment for 24 h (Fig. 1E). These data suggested that

aspirin induced apoptosis in MDA-MB-453 cells via caspase-3

upregulation.

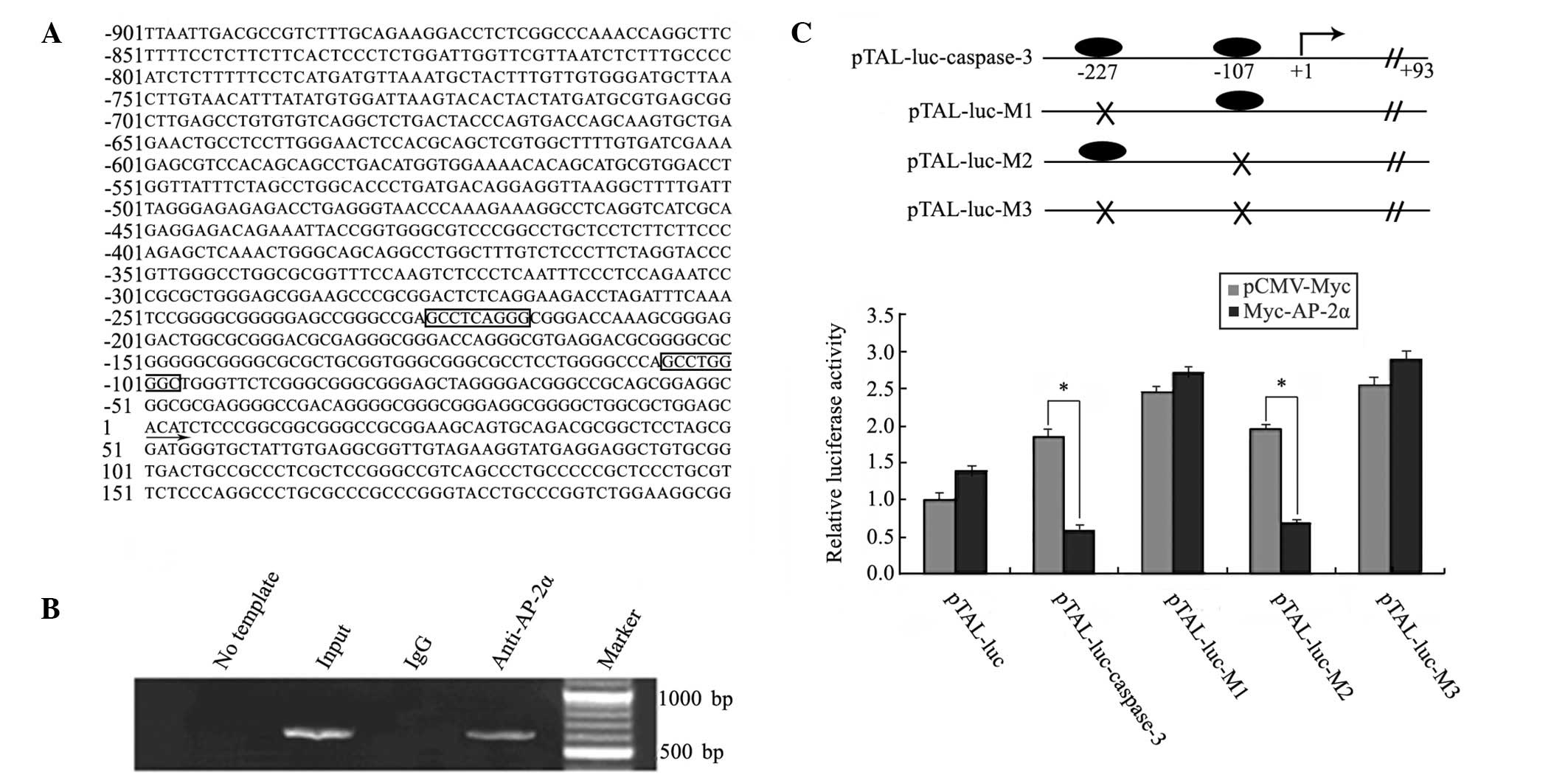

AP2α directly binds to the promoter

region of caspase-3 in MDA-MB-453 cells

Since the transcription level of caspase-3 is

upregulated in aspirin-treated MDA-MB-453 cells, the promoter

region of caspase-3 was analyzed by the JASPAR and MatInspector

programs. As shown in Fig. 2A, two

AP-2α consensus DNA-binding sites in the promoter region of

caspase-3 (nt −901 to nt +200 from transcription start codon) were

observed, nt −227 and nt −107. As AP-2α is important in mammary

carcinoma and highly expressed in MDA-MB-453 cells (16,17,25),

the direct binding of AP-2α to the caspase-3 promoter was

demonstrated by ChIP experiments (Fig.

2B). The predicted band was detected in the input and

AP-2α-ChIP-derived DNA samples, but not in the control

IgG-ChIP-derived DNA samples. To confirm the precise AP-2α binding

sites in the caspase-3 promoter, the promoter region (nt −799 to nt

+93) of caspase-3 was used for a luciferase reporter assay.

Wild-type and mutant promoter luciferase plasmids, including

pTAL-luc-caspase-3, pTAL-luc-M1 (nt −227), -M2 (nt −107) and -M3

(nt −227 and nt −107), were constructed and co-transfected with

pCMV-Myc or pCMV-Myc-AP-2α plasmids, independently. As shown in

Fig. 2C, compared with the

control, overexpression of AP-2α depressed the transcriptional

activities of the constructs pTAL-luc-caspase-3 and pTAL-luc-M2 by

~3-fold. However, pTAL-luc-M1 and -M3 eliminated the effect of

AP-2α, suggesting that AP-2α directly bound to the caspase-3

promoter at the nt −227 site.

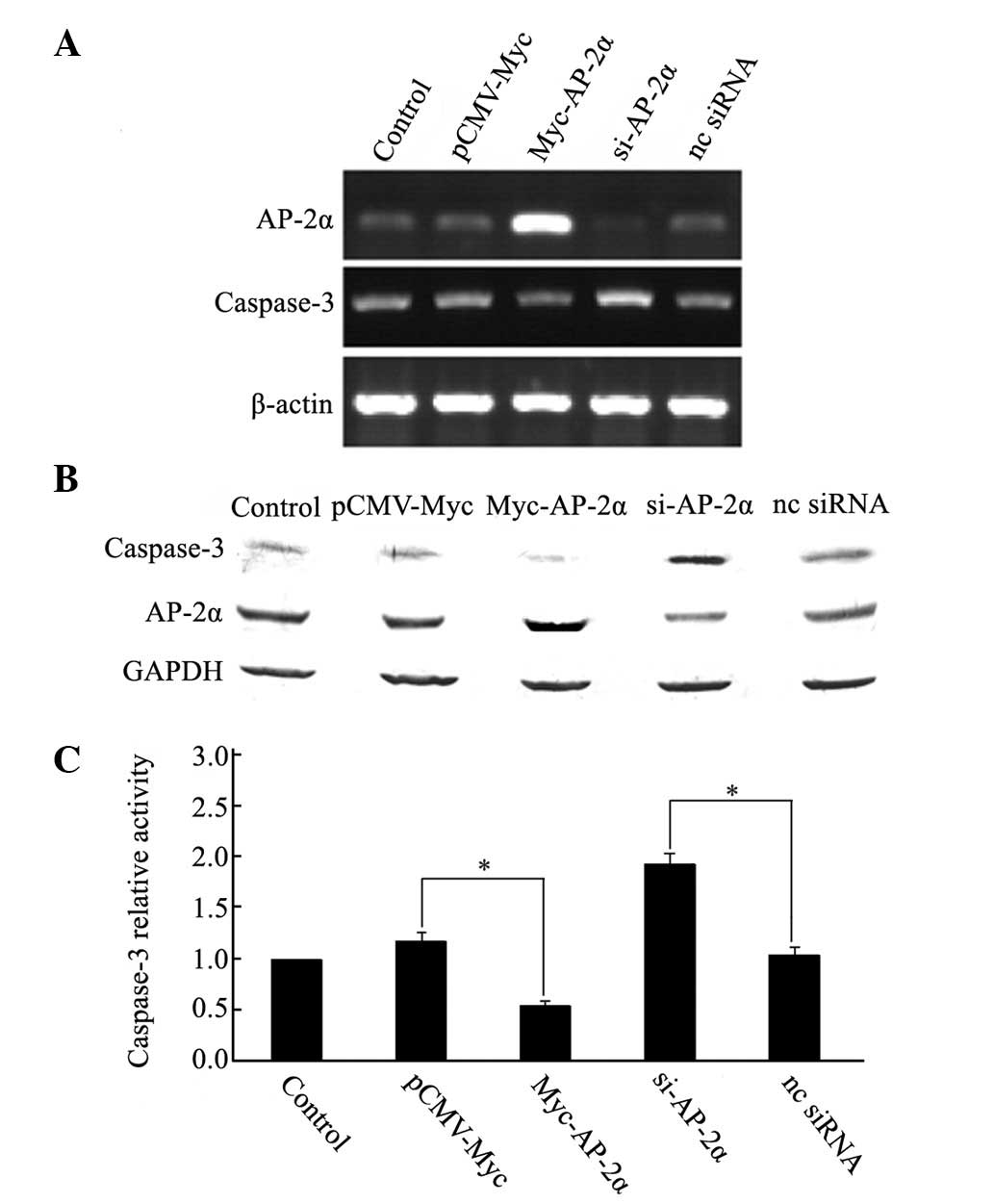

AP2α negatively regulated caspase-3 in

MDA-MB-453 cells

To determine whether this binding conferred positive

or negative regulation on caspase-3, the expression of AP-2α was

knocked down in MDA-MB-453 cells by siRNA and the expression of

caspase-3 was detected using semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western

blotting. Cells transfected with siRNAs against AP-2α showed clear

increases in caspase-3 mRNA (Fig.

3A) and protein levels (Fig.

3B). Expression of the activated caspase-3 was also enhanced,

as determined by a caspase-3 activity assay (Fig. 3C). However, overexpression of AP-2α

decreased the expression levels (Fig.

3A and B) and activity (Fig.

3C) of caspase-3, whereas the controls did not change.

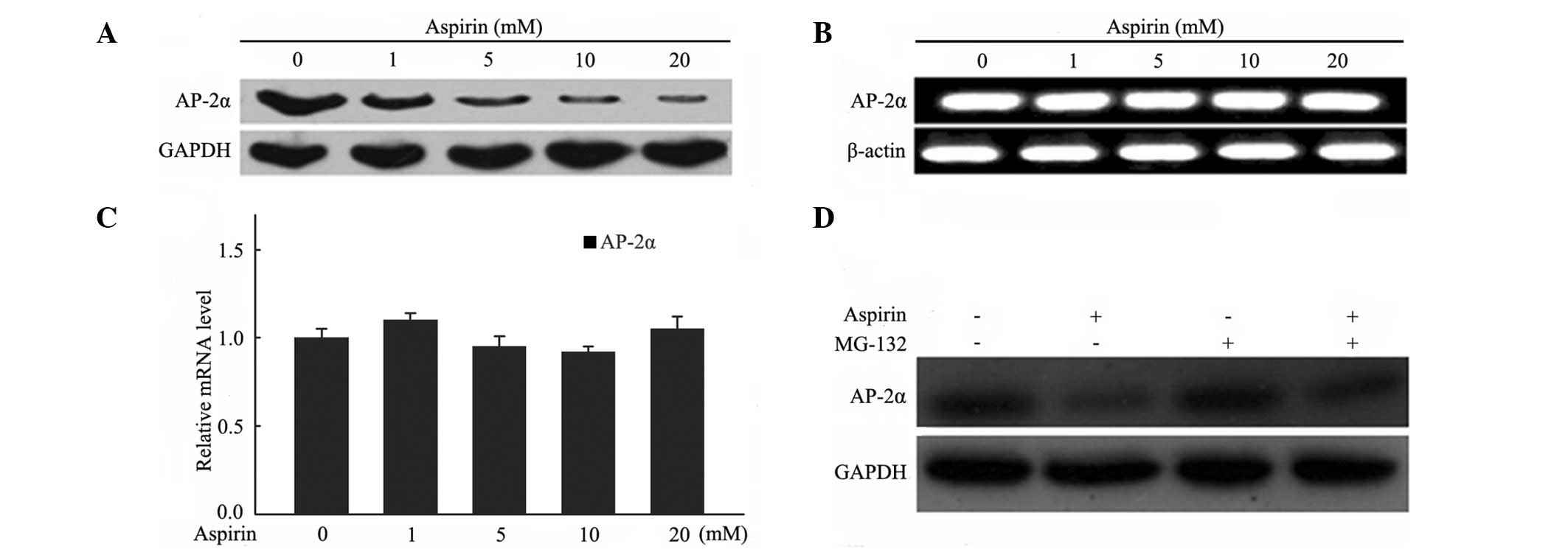

Aspirin induced the degradation of AP-2α

through the proteasome pathway in MDA-MB-453 cells

To investigate whether AP-2α responds to aspirin

treatment in MDA-MB-453 cells, the AP-2α expression levels of mRNA

and protein were evaluated. The results showed that the protein

level of AP-2α was downregulated in a dose-dependent manner in

MDA-MB-453 cells following exposure to various concentrations of

aspirin for 24 h (Fig. 4A).

However, no significant changes were observed in the mRNA levels in

the semi-quantitative and real-time PCR experiments (Fig. 4B and C). It appeared that aspirin

did not affect AP-2α expression at the transcriptional level.

A previous study reported that aspirin treatment

affects protein proteasomal degradation in breast cancer cells

(26). MG132, a proteasome

inhibitor, was used to evaluate whether it was able to block the

degradation of AP-2α in MDA-MB-453 cells following aspirin

treatment. Cells were pre-incubated with MG132 (20 μM) for 5 h

prior to aspirin (10 mM) treatment for 24 h and cell extracts were

used for western blotting to detect AP-2α expression. As shown in

Fig. 4D, the degradation of AP-2α

protein was blocked in the presence of MG132, suggesting that

aspirin induced AP-2α degradation via a proteasome-mediated

pathway.

Discussion

Aspirin has multiple effects and is involved in

various cellular processes. In the last few years, several studies

have shown that aspirin inhibits cancer cell proliferation and

induces apoptosis (3,11,24),

which is consistent with the present results that aspirin exhibits

the same activity in MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cells in a dose- and

time-dependent manner. Although the inhibition of certain proteins,

such as COX and NF-κB, may contribute to the anticancer effects of

aspirin (8,27), at present the pathways leading to

these effects remain to be determined.

In the present study, several novel observations

were reported, including a mechanism by which aspirin may exert its

anticancer effects. The present results showed that the expression

and activity of caspase-3 were upregulated following aspirin

treatment, suggesting that the induction of apoptosis by aspirin in

MDA-MB-453 cells may depend on the caspase pathway and caspase-3

was regulated at its transcriptional level. Promoter analysis then

revealed that AP-2α may be a regulator of caspase-3. Considering

the important roles of AP-2α in breast cancer and its high

expression levels in several breast cancer cell types including

MDA-MB-453 (16,25), further experiments were performed

to study the association between AP-2α and caspase-3. The data

showed that AP-2α negatively regulates caspase-3 transcription via

binding to the promoter region of caspase-3, thus downregulating

the expression of caspase-3 and decreasing its activity. The

expression of AP-2α in cells treated with aspirin was then

evaluated. The present results have shown that AP-2α was

downregulated following aspirin treatment at the protein but not

mRNA level. Aspirin has been reported to affect protein degradation

through the proteasome pathway (26). To assess whether this

downregulation of AP-2α depends on the proteasome pathway, MG132

was selected to block the proteasome pathway. MG132 abrogated the

aspirin-induced reduction of AP-2α.

From the present study, a working model may be

proposed. In this model, AP-2α negatively regulates caspase-3 by

binding to its proximal promoter region in AP-2α-positive cancer

cells. Aspirin promotes the proteasome pathway-dependent

degradation of AP-2α, which increases the expression of apoptotic

effector caspase-3, leading to an increase in activated caspase-3

and finally causing cell apoptosis. This suggests a novel mechanism

for aspirin in breast cancer treatment.

AP-2α acts as an oncogene, which is consistent with

previous reports (16,17,25,28).

However, there are also several lines of evidence indicating that

AP-2α may act as a tumor suppressor gene. Overexpression of AP-2α

induces apoptosis in a number of cancer cells (29–31).

AP-2α has been shown to act as both a tumor suppressor and an

oncogene in various cancer types that may depend on the expression

level and signaling pathways AP-2α is involved in. The controversy

concerning the role of AP-2α reflects the complexity of the cell

signaling pathways. However, a number of critical questions remain

to be answered in order to understand the mechanisms of

aspirin-induced apoptosis.

In summary, the present study demonstrated for the

first time that aspirin upregulates caspase-3 activity through the

downregulation of AP-2α gene expression, leading to the apoptosis

of human breast cancer cells. The present findings also suggest

that aspirin is a potentially powerful therapeutic agent for

various AP-2α-dependent human cancers.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30972624 and

81172112), New Century Excellent Talents in University

(NCET-10-0145), Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province

(2011FJ3140, 2011TT2008), Scientific Research Fund of Hunan

Provincial Education Department (11A072) and China Postdoctoral

Science Foundation (2012M511380).

References

|

1

|

Qiao L, Hanif R, Sphicas E, Shiff SJ and

Rigas B: Effect of aspirin on induction of apoptosis in HT-29 human

colon adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 55:53–64. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kutuk O and Basaga H: Aspirin inhibits

TNFalpha- and IL-1-induced NF-kappaB activation and sensitizes HeLa

cells to apoptosis. Cytokine. 25:229–237. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Alfonso LF, Srivenugopal KS, Arumugam TV,

Abbruscato TJ, Weidanz JA and Bhat GJ: Aspirin inhibits

camptothecin-induced p21CIP1 levels and potentiates

apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 34:597–608.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chattopadhyay M, Goswami S, Rodes DB, et

al: NO-releasing NSAIDs suppress NF-κB signaling in vitro and in

vivo through S-nitrosylation. Cancer Lett. 298:204–211.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang Z, Huang L, Zhao W and Rigas B:

Annexin 1 induced by anti-inflammatory drugs binds to NF-kappaB and

inhibits its activation: anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo.

Cancer Res. 70:2379–2388. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhou H, Huang L, Sun Y and Rigas B: Nitric

oxide-donating aspirin inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer

cells through redox-dependent signaling. Cancer Lett. 273:292–299.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rigas B and Williams JL: NO-donating

NSAIDs and cancer: an overview with a note on whether NO is

required for their action. Nitric Oxide. 19:199–204. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Harris RE, Beebe-Donk J, Doss H and Burr

Doss D: Aspirin, ibuprofen, and other non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer prevention: a critical review of

non-selective COX-2 blockade (Review). Oncol Rep. 13:559–583.

2005.

|

|

9

|

Xiang S, Sun Z, He Q, Yan F, Wang Y and

Zhang J: Aspirin inhibits ErbB2 to induce apoptosis in cervical

cancer cells. Med Oncol. 27:379–387. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim KM, Song JJ, An JY, Kwon YT and Lee

YJ: Pretreatment of acetylsalicylic acid promotes tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by

down-regulating BCL-2 gene expression. J Biol Chem.

280:41047–41056. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Luciani MG, Campregher C and Gasche C:

Aspirin blocks proliferation in colon cells by inducing a G1 arrest

and apoptosis through activation of the checkpoint kinase ATM.

Carcinogenesis. 28:2207–2217. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Royle JS, Ross JA, Ansell I, Bollina P,

Tulloch DN and Habib FK: Nitric oxide donating nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer

cell systems and human prostatic stroma via caspase-3. J Urol.

172:338–344. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gu Q, Wang JD, Xia HH, et al: Activation

of the caspase-8/Bid and Bax pathways in aspirin-induced apoptosis

in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 26:541–546. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hilger-Eversheim K, Moser M, Schorle H and

Buettner R: Regulatory roles of AP-2 transcription factors in

vertebrate development, apoptosis and cell-cycle control. Gene.

260:1–12. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Turner BC, Zhang J, Gumbs AA, et al:

Expression of AP-2 transcription factors in human breast cancer

correlates with the regulation of multiple growth factor signalling

pathways. Cancer Res. 58:5466–5472. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bosher JM, Williams T and Hurst HC: The

developmentally regulated transcription factor AP-2 is involved in

c-erbB-2 overexpression in human mammary carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 92:744–747. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bosher JM, Totty NF, Hsuan JJ, Williams T

and Hurst HC: A family of AP-2 proteins regulates c-erbB-2

expression in mammary carcinoma. Oncogene. 13:1701–1707.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Agus DB, Akita RW, Fox WD, et al:

Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and

prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2:127–137. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sudhakar C, Jain N and Swarup G: Sp1-like

sequences mediate human caspase-3 promoter activation by p73 and

cisplatin. FEBS J. 275:2200–2213. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hubert MA, Sherritt SL, Bachurski CJ and

Handwerger S: Involvement of transcription factor NR2F2 in human

trophoblast differentiation. PLoS One. 5:e94172010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ji BC, Hsu WH, Yang JS, et al: Gallic acid

induces apoptosis via caspase-3 and mitochondrion-dependent

pathways in vitro and suppresses lung xenograft tumor growth in

vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 57:7596–7604. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ailan H, Xiangwen X, Daolong R, et al:

Identification of target genes of transcription factor activator

protein 2 gamma in breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 9:2792009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Power JJ, Dennis MS, Redlak MJ and Miller

TA: Aspirin-induced mucosal cell death in human gastric cells:

evidence supporting an apoptotic mechanism. Dig Dis Sci.

49:1518–1525. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lee SK, Park MS and Nam MJ: Aspirin has

antitumor effects via expression of calpain gene in cervical cancer

cells. J Oncol. 2008:2853742008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Begon DY, Delacroix L, Vernimmen D,

Jackers P and Winkler R: Yin Yang 1 cooperates with activator

protein 2 to stimulate ERBB2 gene expression in mammary cancer

cells. J Biol Chem. 280:24428–24434. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lu M, Strohecker A, Chen F, et al: Aspirin

sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by reducing

survivin levels. Clin Cancer Res. 14:3168–3176. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

McCarty MF and Block KI: Preadministration

of high-dose salicylates, suppressors of NF-kappaB activation, may

increase the chemosensitivity of many cancers: an example of

proapoptotic signal modulation therapy. Integr Cancer Ther.

5:252–268. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhu CH and Domann FE: Dominant negative

interference of transcription factor AP-2 causes inhibition of

ErbB-3 expression and suppresses malignant cell growth. Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 71:47–57. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wajapeyee N and Somasundaram K: Cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis induction by activator protein 2alpha

(AP-2alpha) and the role of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 in

AP-2alpha-mediated growth inhibition. J Biol Chem. 278:52093–52101.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Müller FU, Loser K, Kleideiter U, et al:

Transcription factor AP-2alpha triggers apoptosis in cardiac

myocytes. Cell Death Differ. 11:485–493. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wajapeyee N, Britto R, Ravishankar HM and

Somasundaram K: Apoptosis induction by activator protein 2alpha

involves transcriptional repression of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem.

281:16207–16219. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|