Introduction

Previous genomic studies identified several common

genetic variants that could play a role in large-vessel ischemic

stroke (LVIS) (1). Precise type of

their effect on brain ischemia remains unclear, and it is assumed

that common genetic variants could explain between 39–66% of

variation in ischemic stroke incidence (2). It has also been postulated that the

accumulated effect of the remaining uncommon or rare damaging

variants (called genetic burden) might explain a significant

portion of the genetic predisposition to many common diseases or

phenotypes (3,4). A small number of re-sequencing

reports of European patients with LVIS were published so far. These

studies have demonstrated that infrequent coding variants in

numerous genes might be linked to stroke (5–8).

Platelets have an important role in the pathogenesis

of LVIS based on their activation and adherence to the endothelium

within cerebral arteries, as well as progression of thrombus

(9,10). Most research strategies to date

revealed the effect of genetic variation on reactivity of platelets

and were obtained by analyzing common variants within candidate

genes and/or genome-wide association studies (GWAS), followed by

in vitro studies to assess platelet functions (11). Overall, previous studies on the

genetic background of platelet reactivity indicated that many

different genes contribute to platelet function. Thus far, the

potential contribution of genetic variants within genes encoding

proteins essential to thrombus formation in LVIS have been analyzed

in a small number of studies and the majority of them focused on

the common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within a few

genes associated with glycoproteins on the platelet surface

(11). The results of these

studies suggested that additional loci associated with platelet

functions are yet to be found and that the known loci may contain

high effect rare risk variants that have thus far gone undetected

by GWAS.

Rare coding variants appear to be restricted to

small populations and that was shown in only one previous study,

which concentrated on the re-sequencing of the common variants in

the platelet genes associated with membrane function (12). In addition, another recent

investigation revealed that the rare variants in receptors commonly

associated with platelet functions (e.g. purinergic receptors)

could be associated with the occurrence of LVIS in the Polish

population (13).

Thus, the objective of our current study was to

explain the contribution played by the another set of uncommon and

damaging genetic variants within selected genes associated with

changes in platelet functions in LVIS. We have chosen 54 genes

associated with less known or investigated biochemical processes

associated with platelet functions as the focus for the

re-sequencing study (14–21).

Materials and methods

Clinical material

The study was permitted by both local ethics

committee of the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw,

Poland, and Warsaw Medical University, Warsaw, Poland. The study

conduct conformed to the most recent version of the Declaration of

Helsinki. All participants in the study signed the informed

consent. Full description of the study cohort, including the

inclusion and exclusion criteria were published previously

(12,13,22–24).

Based on the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)

classification we included: i) All patients classified as having

ischemic stroke due to large-vessel atherosclerosis and ii) a

subset of patients classified as having ischemic stroke of unknown

etiology, provided they had at least 50% stenosis of the carotid

artery ipsilateral to the infarct side and no evidence or no

history of atrial fibrillation. Patient with the history of

hemorrhagic or embolic stroke were excluded from the study. As a

control group we used samples from age- and sex-matched 500

patients without history of stroke coming from the same

geographical area as patients with LVIS (13) and collected for unrelated studies

performed at Warsaw Medical University in Poland. Both cohorts of

patients (study and control) were white Caucasian of Polish

ethnicity and originated from central Poland. DNA extraction from

collected blood samples was done as described before (9).

Pooled sequencing

The list of 54 re-sequenced genes is shown in

Table I. These targets contain 846

exons and 10 adjoining bases beyond each exon on both sides. The

genetic loci were selected using the human database (H.

sapiens, hg19, GRCh37, February 2009). Pooled targeted

enrichment of DNA, from LVIS patients (five polls with 100 subjects

per pool) and 500 age-, sex-matched control patients, without

stroke history (five pools with 100 subjects per pool), was done as

described previously. Further explanation of re-sequencing and

analysis of data is provided in the Supplementary material

(Tables SI–SIV).

| Table I.List of 54 platelet genes with exons

sequenced in the present study. |

Table I.

List of 54 platelet genes with exons

sequenced in the present study.

| Author, year | Gene | Protein

encoded | Chromosome and

regions | (Ref.) |

|---|

| Janicki et

al, 2017 | FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE,

high affinity I, receptor for; γ polypeptide | 1q23.3region | (13) |

| Janicki et

al, 2017 | VAV3 | vav 3 guanine

nucleotide exchange factor | 1p13.3 | (13) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | RAF1 | v-raf-1 murine

leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 | 3p25.1 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated

protein kinase 14 | 6p21.31 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 | 9p24.1 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | MAP2K4 | Mitogen-activated

protein kinase kinase 4 17. p12 | 17p12 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | AKT2 | v-akt murine

thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 | 19q13.1-q13.2 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | MAP2K2 | Mitogen-activated

protein kinase kinase 2 | 19p13.3 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009 | GNAZ | Guanine nucleotide

binding protein (G protein), α z polypeptide | 22q11.22 | (14) |

| Jones et al,

2009; Goodall et al, 2010 | TRIM27 | Tripartite motif

containing 27 | 6p22.1 | (14,15) |

| Goodall et

al, 2010 | LRRFIP1 | Leucine rich repeat

(in FLII) interacting protein 1 | 2q37.3 | (15) |

| Goodall et

al, 2010 | COMMD7 | COMM domain

containing 7 | 20q11.21 | (15) |

| Postula et

al, 2013 | RGS7 | Regulator of

G-protein signaling 7 | 1q23.1 | (16) |

| Guerrero et

al, 2011 | LPAR1 | Lysophosphatidic

acid receptor 1 | 9q31.3 | (17) |

| Guerrero et

al, 2011 | MYO5B | Myosin VB | 18q21.1 | (17) |

| Mathias et

al, 2010 | LDHAL6A | Lactate

dehydrogenase A-like 6A | 11p15.1 | (18) |

| Mathias et

al, 2010 | ANKS1B | Ankyrin repeat and

sterile α motif domain containing 1B | 12q23.1 | (18) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010 | PIK3CG |

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, γ

polypeptide | 7q22.3 | (19) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010 | SHH | Sonic hedgehog

homolog | 7q36.3 | (19) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010 | JMJD1C | Jumonji domain

containing 1C | 10q21.2 | (19) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010 | MRVI1 | Murine retrovirus

integration site 1 homolog | 11p15.4 | (19) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | RGS18 | Regulator of

G-protein signaling 18 | 1q31.2 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | ST3GAL3 | ST3 β-galactoside

α-2,3-sialyltransferase 3 | 1p34.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | UGT1A10 | UDP

glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A10 | 2q37.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | NUP210 | Nucleoporin 210

kDa | 3p25.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | RAPGEF2 | Rap guanine

nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 2 | 4q32.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | ADAMTS2 | ADAM

metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 2 | 5q35.3 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | FBXL7 | F-box and

leucine-rich repeat protein 7 | 5p15.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | KLHL31 | Kelch-like family

member 31 | 6p12.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | GMDS | GDP-mannose

4,6-dehydtase | 6p25.3 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | WBSCR17 | Williams-Beuren

syndrome chromosome region 17 | 7q11.22 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | ATP6V1F | ATPase,

H+ transporting, lysosomal 14 kDa, V1 subunit F | 7q32.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | SGCZ | Sarcoglycan, ζ | 8p22 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | STMN4 | Stathmin-like

4 | 8p21.2 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PSKH2 | Protein serine

kinase H2 | 8q21.3 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PIP5K1B |

Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase,

type I, β | 9q21.11 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PTPRD | Protein tyrosine

phosphatase, receptor type, D | 9p24.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | MIPOL1 | Mirror-image

polydactyly 1 | 14q13.3-q21.1 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | SVIL | Supervillin | 10p11.23 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | CUBN | Cubilin (intrinsic

factor-cobalamin receptor) | 10p13 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | ST3GAL4 | ST3 β-galactoside

α-2,3-sialyltransferase 4 | 11q24.2 | (19,20) |

| Johnson, 2010

Johnson, 2011 | KCNQ1 | Potassium

voltage-gated channel, KQT-like subfamily, member 1 | 11p15.5-p15.4 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | HSD17B6 | Hydroxysteroid

(17-β) dehydrogenase 6 | 12q13.3 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | RAP1B | RAP1B, member of

RAS oncogene family | 12q15 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PTPN11 | Protein tyrosine

phosphatase, non-receptor type 11 | 12q24 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | THSD4 | Thrombospondin,

type I, domain containing 4 | 15q23 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | TAOK1 | TAO kinase 1 | 17q11.2 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | SETBP1 | SET binding protein

1 | 18q12.3 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 |

KIAA0802 | SOGA family member

2 | 18p11.22 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | CTCFL | CCCTC-binding

factor (zinc finger protein)-like | 20q13.31 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PCK1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate

carboxykinase 1 | 20q13.31 | (19,20) |

| Johnson et

al, 2010; Johnson, 2011 | PRNP | Prion protein | 20p 13 | (19,20) |

| Shiffman et

al, 2006*** | VAMP8 | Vesicle-associated

membrane protein 8 | 2p12-p11.2 | (21) |

| Lee et al,

2014 | GLIS3 | GLIS family zinc

finger 3 | 9p24.2 | (26) |

Verification of selected variants by

individual genotyping

Individual genotyping for selected markers in

individual DNA samples was performed using a custom Sequenom iPLEX

assay in conjunction with the Mass ARRAY platform (Sequenom Inc.,

La Jolla, CA, USA). Panels of SNP markers were designed using

Sequenom Assay Design 3.2 software (Sequenom Inc.), in a similar

fashion to the previously described methodology from our laboratory

(9,16,17).

Statistical analysis

A cumulative minor allele frequency (cMAF) was

utilized to show the allelic frequency of the investigated

variants, which encompasses all rare damaging variants individually

genotyped in the investigated cohorts, as well as within each of

the analyzed loci. Pearson Chi-square test was used in order to

analyze differences in cMAF for all individually genotyped variants

between the study and control cohorts (VassarStats: Website for

Statistical Computation on http://vassarstats.net/). The pooled minor allele test

(CMAT) (10,000 × permutations) was used for comparison of all

variants within investigated loci to estimate the statistical

significance of the observed differences in the accumulation of

variants. CMAT is a pooling method proposed by Zawistowski et

al (25) and works by

comparing weighted minor-allele counts (for cases and controls)

against the weighted major-allele counts (for cases and controls).

Although the CMAT test statistic is based on a chi-square

statistic, it does not follow a known distribution and its

significance has to be determined by a permutation procedure. The

calculations of CMAT were performed using AssotesR package (0.1-10)

from CRAN repository (cran.r-project.org/package=AssotesteR) and written by

Gaston Sanchez (gastonsanchez.com/) as documented at www.rdocumentation.org/packages/AssotesteR/versions/0.1-10.

The significance threshold was adjusted to the number of

re-sequenced loci, when needed (13,25).

Power and sample size

considerations

For the power calculations, instead of using

individual rare variants, we decided to use predicted cMAF for all

deleterious rare variants in the sequenced loci. We have followed a

self-sufficient, closed-form, maximum-likelihood estimator for

allele frequencies that accounts for errors associated with

sequencing, and a likelihood-ratio test statistic that provides a

simple means for evaluating the null hypothesis of monomorphism

(13,26,27).

Unbiased estimates of allele frequencies 10/N (where N is the

number of individuals sampled) appear to be achievable, and

near-certain identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism

(SNP) requires a cMAF of at least 0.01 (i.e., 10 variants per

cohort). In addition, because the power to detect significant

allele-frequency differences between the two populations is

limited, we set both the number of sampled individuals (500 in the

cohort) and depth of sequencing coverage in excess of 100.

Fluorescence-based (FLIPR) functional

assay for KCNQ1 variants

Chinese hamster ovaries cells (CHO) cultures stably

transfected with human muscarinic type 1 receptor (M1) were

purchased from cDNA Resource Center, Bloomberg, PA. The CHO-M1

cells were then transiently co-transfected with KCNQ1 cDNA

constructs. Wild-type KCNQ1 cDNA constructs (in pcDNA3.1) were

prepared by Watson Bio Sciences (Houston, TX, USA). The fidelity of

the mutations for each variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Details about the transfection techniques and cell culture

conditions used in our laboratory were published before (13).

The heterologous expressed potassium KCNQ1 channels

were inhibited by the M1 receptor agonist oxotremorine (OxoM, 10

nM), resulting in significant changes in membrane polarization

(fully antagonized by muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine at 1

µM-not shown).

The Fluorescence Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR) on

Flex Station 3 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) was employed

to measure the fluorescence changes. After the cells were loaded

with membrane dye, the plate with the cells and plate containing

OxoM (10 nM) were inserted into the plate reader. The raw

fluorescence readings were converted and plotted as the change in

relative fluorescence before (F0 baseline=100%) and after OxoM

application F), according to the formula ((F/F0)*100%). For all

experimental conditions, minimum fluorescence (Fmin) and maximum

fluorescence (Fmax) were recorded in triplicates after

administration. The summary data are presented as summary trend

lines for WT and mutants, as well as averages (with standard

deviations) for Fmax and Fmin and for each variant and WT cells

used in FLIPR experiments. The final data represent all

measurements done in triplicates and in three independent

experiments (cell populations). Data and statistical analysis were

performed using analysis of variance, followed by the Student's

t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Study design and sequencing

coverage

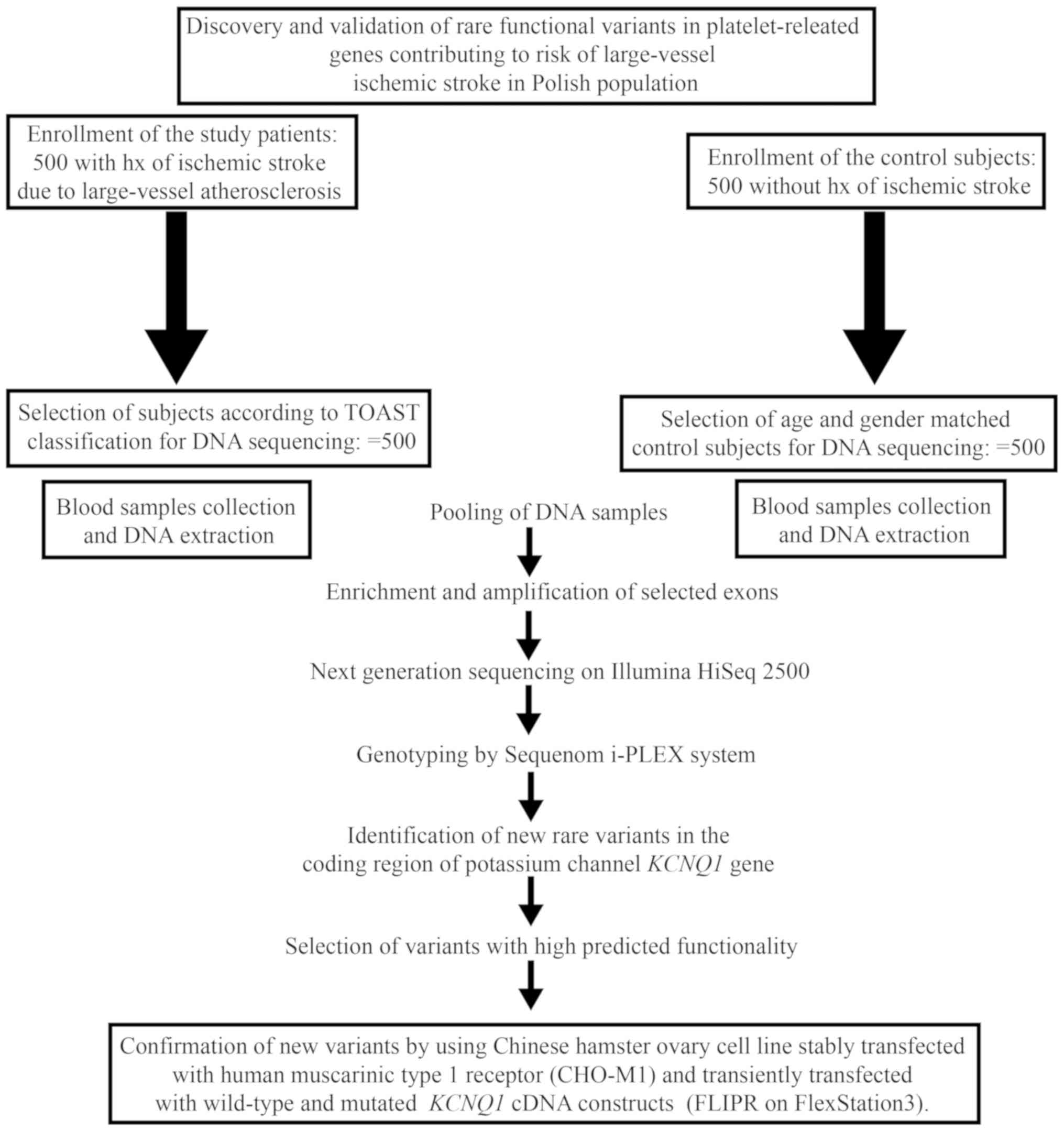

The design of the study is presented in Fig. 1. The enrichment of the target loci

resulted in coverage of 99.6% and produced 36.1 (22.7–45.9 range)

million reads which is 5.3 (3–7 range) Gbp per re-sequenced sample.

It relates to an average coverage of 12,000× per pool and an

average coverage of 120× per patient sample (range 21–369).

Selection of rare variants (based on

MAF<1%)

The step-wise analysis of the observed variants is

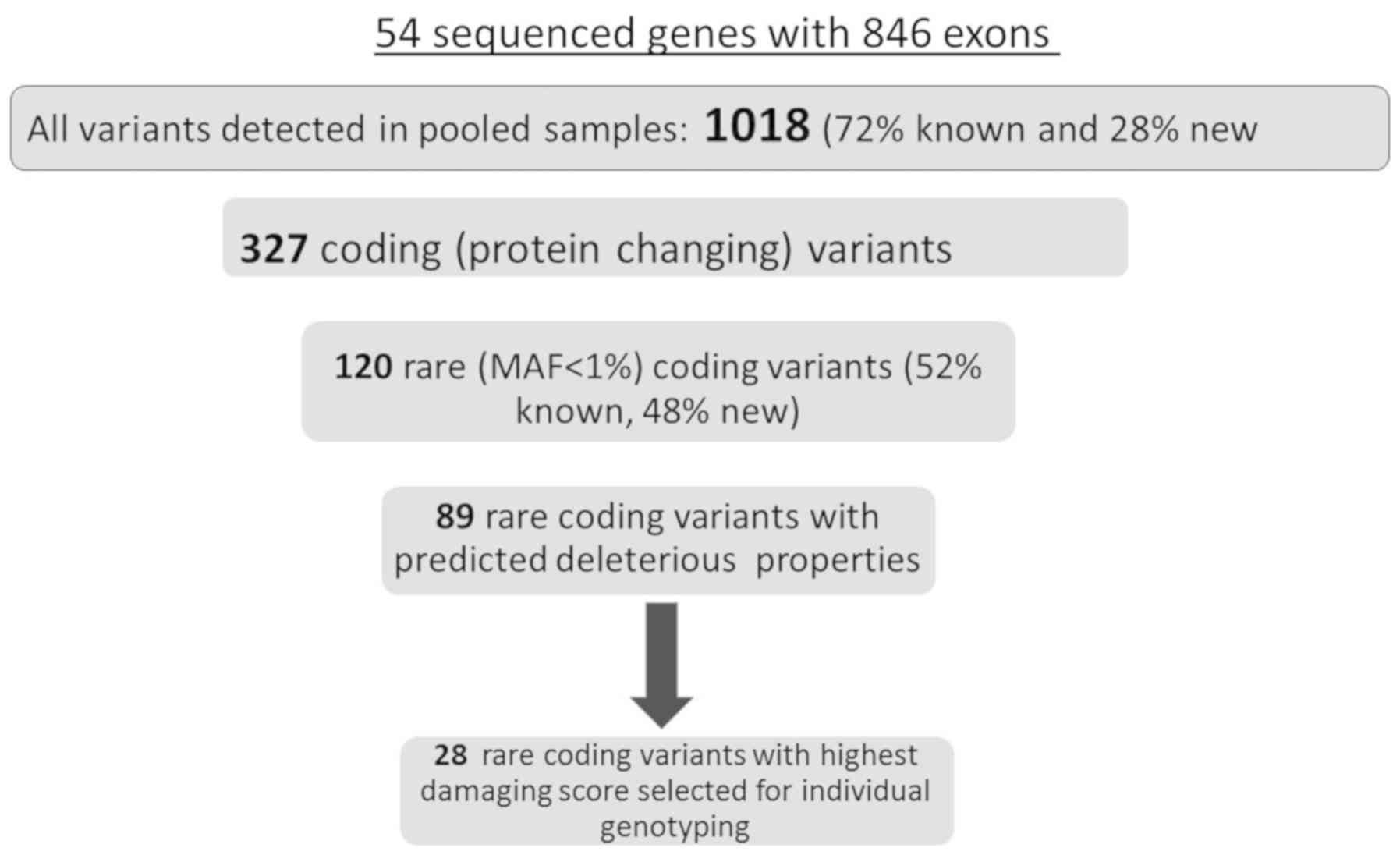

presented in Fig. 2. In total,

1018 unique variants, irrespective of MAF and with adequate quality

were observed in both investigated cohorts. The complete list of

all observed variants is provided in the Supplementary materials,

Tables SII for all non-coding

variants and SIII for all non-synonymous variants. Seventy two

percent of all variants were previously listed in the available

databases, and 28% were new. Out of all observed variants, 327

(32.1%) were located in the coding segments of the sequenced genes,

and the remainder was located in untranslated regions. Out of all

coding variants, 120 variants (Supplementary material, Table SIV-list of all rare non-synonymous

variants) were selected based on MAF <1% (i.e. rare variants)

(28), which consisted of 52 known

(by dbSNP149 November 2016) and 68 unlisted, novel variants.

Verification of selected variants by

individual genotyping

In total, 28 SNVs with the highest predicted

damaging score calculated by Combined Annotation Dependent

Depletion (CADD) score were chosen for individual genotyping. The

minimum CADD score of 10 served as a threshold for predicted

deleteriousness. The individual genotyping was performed in

patients from the original cohort and revealed that the identity of

all 28 initially selected variants could be confirmed by individual

genotyping, which indicates no sequencing errors for these

variants.

The initial statistical analysis utilized Pearsons

Chi-square test for the assessment of the differences in the

cumulative frequency of all 28 individually genotyped variants

between the investigated cohorts. There was a highly statistically

significant (P=0.00045) difference (cMAF control=1.2% vs. cMAF

stroke=3.6%) in cMAF for all damaging variants in the LVIS group

when compared with controls.

The statistical analysis of the number of variants

within the single gene loci was based on combined minor allele

association test (CMAT). The region-based, Bonferroni corrected,

significance threshold was P=0.00092 (nominal P=0.05/54 sequenced

genes). It demonstrated a statistically significant difference

(P=0.0009) between control and IS cohorts for the KCNQ1

location. The KCNQ1 exons locus contained 3 novel and 3

known rare and deleterious (CADD score range 13.22-39) coding

variants (Table II).

| Table II.cMAF for 28 rare and most damaging

variants observed in the individually genotyped patients from

control and LVIS cohorts. |

Table II.

cMAF for 28 rare and most damaging

variants observed in the individually genotyped patients from

control and LVIS cohorts.

| Gene locus | Number of carriers

in control cohort, n=500 | Number of carriers

in LVIS cohort, n=500 | P-value |

|---|

| ADAMT2 | 2 | 3 | 0.4 |

| CUBN | 0 | 4 | 0.06 |

| GLIS3 | 2 | 0 | 0.1 |

| KCNQ1 | 0 | 6 | 0.0009a |

| LDHAL6A | 3 | 2 | 0.4 |

| MAP2K2 | 0 | 2 | 0.2 |

| MIPOL1 | 0 | 2 | 0.8 |

| MTCL1 | 4 | 3 | 0.9 |

| MYO5B | 0 | 4 | 0.06 |

| PTPRJ | 0 | 2 | 0.1 |

| SHH | 0 | 2 | 0.1 |

| SVIL | 1 | 3 | 0.15 |

| UGT1A1 | 0 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Total number of

carriers and cMAF for all loci | 12 | 36 |

0.00045b |

| Odds ratio and 95%

confidence intervals (in brackets) |

| 3.07

(1.59–5.94) |

|

Functional analysis of selected rare

variants within KNCQ1 gene

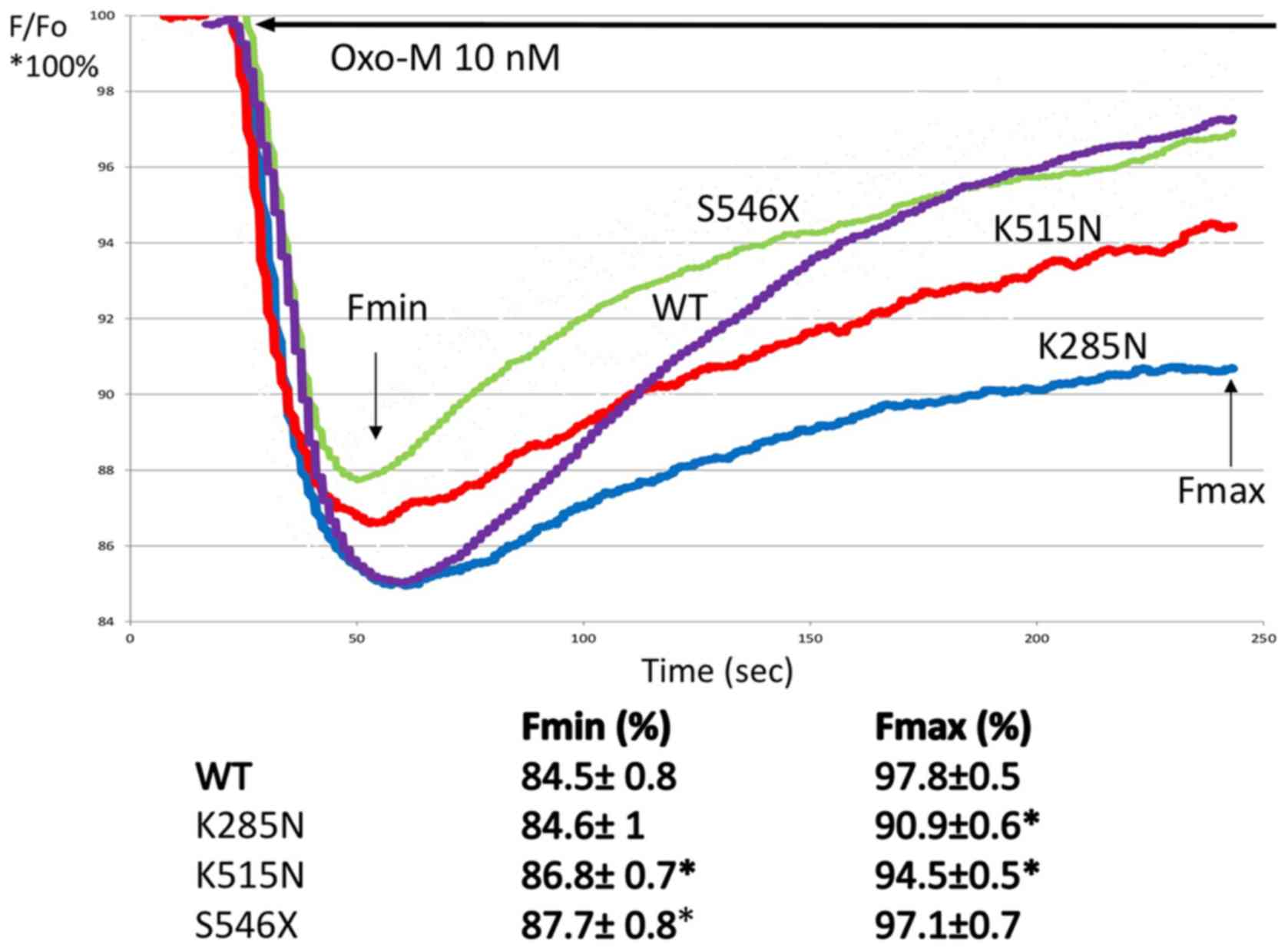

To evaluate whether the observed variants exert a

damaging effect on KCNQ1 function, we selected 3 novel and

most damaging variants from the KCNQ1 locus to examine the

coupling between the heterologous expressed human M1 receptor and

KCNQ1 channels in CHO-M1 cells (Table III). Fig. 3 shows the summary of changes in

relative fluorescence for CHO-M1 cells expressing wild-type

KCNQ1, and variants KCNQ1 c. G855T p. K285N,

KCNQ1 c. G1545T p. K515N, and KCNQ1 c. 1637A p.

S546X. Following oxoM application (final concentration 10 nM), the

fluorescence decreased rapidly, indicating corresponding changes in

cell membrane potential. We expressed the changes in fluorescence

both as the differences between baseline fluorescence and its

changes (in % of baseline=Fo=100%) over 250 sec after

administration of oxoM (shown as trend line for all observations)

and average values of minimum (Fmin) and maximum (Fmax) of relative

fluorescence during the recording period (separately for WT and

variants). The provided trend lines represent summary values for

all observations (2–3 independent cell cultures and all

measurements in triplicates of plate wells). A significant decrease

in fluorescence signal for each variant was observed after

administration of oxoM when compared with the KCNQ1

wild-type-expressing CHO-M1 cells. Correspondingly, the

statistically significant decrease (P<0.05 ANOVA, followed by

t-test) in the average Fmin and Fmax was observed for all 3

investigated variants, indicating at least partial loss-of-function

characteristics for variant proteins, when compared to WT.

| Figure 3.Effect of Oxo-M on relative

fluorescence in CHO-M1 cells heterologously expressing KCNQ1

wild-type and KCNQ1 variant channels. Each panel shows % change

(from baseline Fo=100%) of F in CHO-M1 transfected with wild-type

K285N, K515N and S546X variants (where X is random amino acid

substituted). Fluorescence signals were acquired before and during

Oxo-M (10 nM, solid line) application. The data are presented trend

lines for all the experimental points (2–3 independent experiments,

triplicate measurements). For each variant and the calculated Fmin

and Fmax relative fluorescence change, including standard deviation

was calculated. Fmax and Fmin averages were compared with WT using

analysis of variance, followed by a t-test. *P<0.05. Oxo-M,

oxotremorine; CHO-M1, human muscarinic type 1 receptor; KCNQ1,

potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1; F,

fluorescence; Fmin, minimum fluorescence; Fmax, maximum

fluorescence; Fo, baseline fluorescence; WT, wild-type. |

| Table III.Rare coding variants for KCNQ1

gene observed in the study patients, as identified by exome

sequencing and verified by individual genotyping. |

Table III.

Rare coding variants for KCNQ1

gene observed in the study patients, as identified by exome

sequencing and verified by individual genotyping.

| dbSNP | MAFctrl pooled | MAFstroke

pooled | MAF individual

genotyping in control | MAF in individual

genotyping in stroke | DNA change | Amino acid

change | CADD |

|---|

| rs12720457 | 0.80% | ND | 0.01% | ND | c.G1179T | p.K393N |

6.560 |

| novel | ND | 0.75% | ND | 0.1% | c.G4T | p.D2Y |

5.53 |

| rs199472712 | ND | 0.95% | ND | 0.1% | c.G724T | p.D242Y | 19.35 |

| Novel | ND | 0.74% | ND | 0.1% | c.G855T | p.K285N | 15.48 |

| Novel | ND | 0.65% | ND | 0.1% |

c.G1545T | p.K515N | 13.22 |

| rs199472793 | ND | 0.71% | ND | 0.1% | c.C1597T | p.R533W | 15.28 |

| Novel | ND | 0.85% | ND | 0.1% |

c.C1637A | p.S546X | 39 |

Discussion

We present the results of the analysis of the

genetic burden of the infrequent coding variants in 54 genes

associated with platelet function and its possible association with

LVIS. The assessment of MAF for the investigated uncommon coding

variants established that there was a significant accumulation of

those variants in the LVIS group when compared to the control

group. By grouping these variants by sequenced loci instead of

analyzing them individually, we were able to observe associations

which could be underpowered when applied to single variants, as

shown in previous studies of other traits (12,13).

In particular, we found an association between the increased

accumulation of rare variants in KCNQ1 locus and LVIS. It is

important to note that, with the exception of 3 already known

variants, the remaining 3 observed damaging variants within

KCNQ1 locus were novel. It is therefore likely that at least

some of the observed variants might be restricted to the Polish

cohort. So far detailed genotypes in the Polish population have

been rather poorly characterized in the available genomic

databases. This in turn might suggest that the verification of the

obtained results in the independent cohorts could be challenging.

For example, it was previously demonstrated that, at least in case

of rare damaging variants associated with ulcerative colitis, the

rare variants observed in the Dutch population could not be

replicated in a German cohort (29). Another study on inflammatory bowel

disease, that included several thousands of European individuals

and individuals of other ancestry, showed that although the

majority of the loci with MAF>5% were shared between different

ancestry groups (30), no such

similarities were observed for uncommon alleles. In fact, rare

variants were even more likely to be specific to a particular

population, as was confirmed by a recent sequencing study (31). What is more, rare variants might

differ significantly among even closely related populations

(32).

We were able to observe only few (out of several

hundreds) of previously listed rare coding variants in the

KCNQ1 locus, which might indicate either limited power of

the study or population-specific distribution of these variants.

Further studies in other populations will be helpful to verify if

the rare damaging variants in the KCNQ1 coding locus are

indeed associated with large-vessel IS, or also with other types of

stroke (small-vessel and embolic).

The KCNQ channels, members of the voltage-gated

(KV7.1) K+-selective channel subfamily, play

a major role in K+ ion transport. For instance, previous

studies have shown that both KV channels KCNA3 and G

protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK)

regulate platelet activation (33,34).

The presence of Kv7.1 channel in blood cells, including platelets,

suggests that they play a role in agonist-mediated regulation of

platelet-driven thrombotic pathways that is crucial to hemostasis

during IS (35,36).

Our in vitro results indicate that

oxoM-mediated changes in the membrane potential of cells expressing

M1 receptors and KCNQ1 channel variants were attenuated

(loss-of-function characteristics) when compared to cells

expressing the wild-type receptors. These findings suggest that the

signaling might be diminished in cells expressing the mutant KCNQ1

channels. The coding variants in KCNQ1 were previously

evaluated in different cardiovascular diseases and DM (37–41).

It has been also reported that obesity along with IS may modify

methylation of KCNQ1 gene and plasma KCNQ1 protein

concentration (38,39). The coding variants in KCNQ1 have

been reported to lead to congenital long QT syndrome (42), an autosomal dominant disorder.

Because of the demonstrated deleterious properties of the

investigated variants, it should be also considered that the stroke

patients in the study may have suffered from an ischemic stroke

secondary to a congenital disorder. Whether KCNQ1 variants are

disease-associated with ischemic stroke (possibly via platelet

function) or disease-causing for congenital QT syndrome (with

reportedly higher incidence of ischemic stroke is one of the

questions which should be clarified in the future investigations

(41).

Moreover, in one of the largest to date GWAS on

platelet function, KCNQ1 locus was discovered to contribute

to platelet function variability (19,20).

The exact mechanism of these interactions remains unknown, as

KCNQ1 is mostly co-assembled with the product of the

KCNE1 (minimal K+-channel protein) gene in the

heart to form a cardiac-delayed rectifier-like K+

current and the effect of KCNQ1 channels on platelet function has

not been not directly investigated so far. However, Gallego-Fabrega

et al (43) reported

recently that the methylation pattern of KCNQ1 locus might be

associated with vascular recurrence in aspirin-treated stroke

patients.

The study is limited by the absence of independent

verification of accumulation of deleterious KCNQ1 rare variants.

However, it was demonstrated previously that the occurrence of rare

variants, because of their private character, is often limited to

very restricted cohorts and has been difficult to repeat in other

cohorts, unless the confirmation cohorts are truly large (in this

case several tens of thousands of patients). The added drawback of

the presented research is that the direct effect of the observed

genomic variants on the platelet function (e.g. aggregation) was

not evaluated. This might raise an issue if the observed change in

the frequency of variants were entirely related to the platelet

function or, perhaps, some other mechanisms related to biochemical

pathways. Moreover, it should be noted that only a limited number

of all known genes related to platelet function were re-sequenced

in this study. We would like to stress that the results of

re-sequencing of the more frequently investigated 26 genes related

to platelet function were published by our group in the past

(13).

The outcome of this study indicates that the

increased accumulation of rare damaging variants in the exons of

the sequenced 54 platelet genes (and in particular for variants

located in the region of potassium channel KCNQ1 gene) could

be associated with LVIS. The mechanism of the interaction of these

variants with LVIS currently appears unclear and therefore requires

further investigations. It is also uncertain if our results could

be directly translated to other populations, as the variants

responsible for the observed associations appear to be limited to

the investigated cohort. Further studies in different, as well as

much larger cohorts, are required to address this problem.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Michal Karlinski

(Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw, Poland) and Dr

Agnieszka Cudna (Center for Preclinical Research and Technology

CEPT, Warsaw, Poland) for preparing the samples and database for

further analysis.

Funding

Research subject was implemented with CEPT

infrastructure financed by the European Union-the European Regional

Development Fund within the Operational Program ‘Innovative

economy’ for 2007–2013. The study was supported financially as part

of the research grant from the National Science Center OPUS

research grant (grant no. 2013/11/B/NZ7/01541).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

PKJ and MP conceived the concept and design for the

study, were involved in data collection and analysis, and

supervised the work. CE and VRV contributed to the design of the

research, and were involved in data collection and analysis. SS and

YIK verified the analytical methods. JP, AC, IKJ and DMG were

involved in data collection and analysis. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the

ethical standards of the responsible committee on human

experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki

Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was

obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Patient consent for publication

The consent for publication was obtained from all

patients included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

LVIS

|

large-vessel ischemic stroke

|

|

CHO-M1

|

human muscarinic type 1 receptor

|

|

FLIPR

|

fluorescence imaging plate reader

|

|

GWAS

|

genome wide association studies

|

|

SNP

|

single nucleotide polymorphism

|

|

CAD

|

coronary artery disease

|

|

cMAF

|

cumulative minor allele frequency

|

|

CMAT

|

combined minor allele test

|

|

SNVs

|

single nucleotide variants

|

|

Fmin

|

minimum fluorescence

|

|

Fmax

|

maximum fluorescence

|

|

CADD

|

Combined Annotation Dependent

Depletion

|

|

CHF

|

congestive heart failure

|

|

DM

|

diabetes mellitus

|

|

GIRK

|

G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying

K+ channels

|

References

|

1

|

Welter D, MacArthur J, Morales J, Burdett

T, Hall P, Junkins H, Klemm A, Flicek P, Manolio T, Hindorff L and

Parkinson H: The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of

SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D1001–D1006. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Holliday EG, Maguire JM, Evans TJ, Koblar

SA, Jannes J, Sturm JW, Hankey GJ, Baker R, Golledge J, Parsons MW,

et al: Common variants at 6p21.1 are associated with large artery

atherosclerotic stroke. Nat Genet. 44:1147–1151. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bevan S, Traylor M, Adib-Samii P, Malik R,

Paul NL, Jackson C, Farrall M, Rothwell PM, Sudlow C, Dichgans M

and Markus HS: Genetic heritability of ischemic stroke and the

contribution of previously reported candidate gene and genomewide

associations. Stroke. 43:3161–3167. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gibson G: Rare and common variants: Twenty

arguments. Nat Rev Genet. 13:135–145. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Genome of the Netherlands Consortium, .

Whole-genome sequence variation, population structure and

demographic history of the Dutch population. Nat Genet. 46:818–25.

2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cheng YC, Cole JW, Kittner SJ and Mitchell

BD: Genetics of ischemic stroke in young adults. Circ Cardiovasc

Genet. 7:383–392. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Auer PL, Nalls M, Meschia JF, Worrall BB,

Longstreth WT Jr, Seshadri S, Kooperberg C, Burger KM, Carlson CS,

Carty CL, et al: Rare and coding region genetic variants associated

with risk of ischemic stroke: The NHLBI exome sequence project.

JAMA Neurol. 72:781–788. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lindgren A: Stroke genetics: A review and

update. J Stroke. 16:114–123. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Anyanwu C, Hahn M, Nath M, Li J, Barone

FC, Rosenbaum DM and Zhou L: Platelets pleiotropic roles in

ischemic stroke. Austin J Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke. 3:10482016.

|

|

10

|

del Zoppo GJ: The role of platelets in

ischemic stroke. Neurology. 51 (Suppl 3):S9–S14. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Milanowski L, Pordzik J, Janicki PK and

Postula M: Common genetic variants in platelet surface receptors

and its association with ischemic stroke. Pharmacogenomics.

17:953–971. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Postula M, Janicki PK, Milanowski L,

Pordzik J, Eyileten C, Karlinski M, Wylezol P, Solarska M,

Czlonkowka A, Kurkowska-Jastrzebka I, et al: Association of

frequent genetic variants in platelet activation pathway genes with

large-vessel ischemic stroke in Polish population. Platelets.

28:66–73. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Janicki PK, Eyileten C, Ruiz-Velasco V,

Sedeek KA, Pordzik J, Czlonkowska A, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I,

Sugino S, Imamura-Kawasawa Y, Mirowska-Guzel D and Postula M:

Population-specific associations of deleterious rare variants in

coding region of P2RY1-P2RY12 purinergic receptor genes in

large-vessel ischemic stroke patients. Int J Mol Sci. 18:E26782017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jones CI, Bray S, Garner SF, Stephens J,

de Bono B, Angenent WG, Bentley D, Burns P, Coffey A, Deloukas P,

et al: A functional genomics approach reveals novel quantitative

trait loci associated with platelet signaling pathways. Blood.

114:1405–1416. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Goodall AH, Burns P, Salles I, Macaulay

IC, Jones CI, Ardissino D, de Bono B, Bray SL, Deckmyn H, Dudbridge

F, et al: Transcription profiling in human platelets reveals

LRRFIP1 as a novel protein regulating platelet function. Blood.

116:4646–4656. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Postula M, Janicki PK, Rosiak M,

Kaplon-Cieslicka A, Trzepla E, Filipiak KJ, Kosior DA, Czlonkowski

A and Opolski G: New single nucleotide polymorphisms associated

with differences in platelets reactivity in patients with type 2

diabetes treated with acetylsalicylic acid: Genome-wide association

approach and pooled DNA strategy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 36:65–73.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guerrero JA, Rivera J, Quiroga T,

Martinez-Perez A, Antón AI, Martínez C, Panes O, Vicente V,

Mezzano D, Soria JM and Corral J: Novel loci involved in platelet

function and platelet count identified by a genome-wide study

performed in children. Haematologica. 96:1335–1343. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mathias RA, Kim Y, Sung H, Yanek LR,

Mantese VJ, Hererra-Galeano JE, Ruczinski I, Wilson AF, Faraday N,

Becker LC and Becker DM: A combined genome-wide linkage and

association approach to find susceptibility loci for platelet

function phenotypes in European American and African American

families with coronary artery disease. BMC Med Genomics. 3:222010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Johnson AD, Yanek LR, Chen MH, Faraday N,

Larson MG, Tofler G, Lin SJ, Kraja AT, Province MA, Yang Q, et al:

Genome-wide meta-analyses identifies seven loci associated with

platelet aggregation in response to agonists. Nat Genet.

42:608–613. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Johnson AD: The genetics of common

variation affecting platelet development, function and

pharmaceutical targeting. J Thromb Haemost. 9 (Suppl 1):S246–S257.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Shiffman D, Rowland CM, Louie JZ, Luke MM,

Bare LA, Bolonick JI, Young BA, Catanese JJ, Stiggins CF, Pullinger

CR, et al: Gene variants of VAMP8 and HNRPUL1 are associated with

early-onset myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

26:1613–1618. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

No authors listed, . Stroke-1989.

Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy.

Report of the WHO task force on stroke and other cerebrovascular

disorders. Stroke. 20:1407–1431. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Foulkes MA, Wolf PA, Price TR, Mohr JP and

Hier DB: The stroke data bank: Design, methods, and baseline

characteristics. Stroke. 19:547–554. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Grabska K, Gromadzka G and Członkowska A:

Infections and ischemic stroke outcome. Neurol Res Int.

2011:6913482011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zawistowski M, Gopalahrishnan S, Ding J,

Li Y, Grimm S and Zöllner S: Extending rare-variant testing

strategies: Analysis of noncoding sequence and imputed genotypes.

Am J Hum Genet. 87:604–617. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee S, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M and Lin X:

Rare-variant association analysis: Study designs and statistical

tests. Am J Hum Genet. 95:5–23. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lynch M, Bost D, Wilson S, Maruki T and

Harrison S: Population-genetic inference from pooled-sequencing

data. Genome Biol Evol. 6:1210–1228. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O'Roak BJ,

Cooper GM and Shendure J: A general framework for estimating the

relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet.

46:310–315. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Visschedijk MC, Alberts R, Mucha S, Deelen

P, de Jong DJ, Pierik M, Spekhorst LM, Imhann F, van der Meulen-de

Jong AE, van der Woude CJ, et al: Pooled resequencing of 122

ulcerative colitis genes in a large dutch cohort suggests

population-specific associations of rare variants in MUC2. PLoS

One. 11:e01596092016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, Ng SC,

Alberts R, Takahashi A, Ripke S, Lee JC, Jostins L, Shah T, et al:

Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for

inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across

populations. Nat Genet. 47:979–986. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hong KW, Shin MS, Ahn YB, Lee HJ and Kim

HD: Genomewide association study on chronic periodontitis in Korean

population: Results from the Yangpyeong health cohort. J Clin

Periodontol. 42:703–710. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Prescott NJ, Lehne B, Stone K, Lee JC,

Taylor K, Knight J, Papouli E, Mirza MM, Simpson MA, Spain SL, et

al: Pooled sequencing of 531 genes in inflammatory bowel disease

identifies an associated rare variant in BTNL2 and implicates other

immune related genes. PLoS Genet. 11:e10049552015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

McCloskey C, Jones S, Amisten S, Snowden

RT, Kaczmarek LK, Erlinge D, Goodall AH, Forsythe ID and

Mahaut-Smith MP: Kv1.3 is the exclusive voltage-gated K+

channel of platelets and megakaryocytes: Roles in membrane

potential, Ca2+ signalling and platelet count. J

Physiol. 588:1399–1406. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shankar H, Kahner BN, Prabhakar J, Lakhani

P, Kim S and Kunapuli SP: G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying

potassium channels regulate ADP-induced cPLA2 activity in platelets

through Src family kinases. Blood. 108:3027–3034. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kapural L and Fein A: Suppression of the

voltage-gated K+ current of human megakaryocytes by

thrombin and prostacyclin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1355:331–342.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Schmidt EM, Münzer P, Borst O, Kraemer BF,

Schmid E, Urban B, Lindemann S, Ruth P, Gawaz M and Lang F: Ion

channels in the regulation of platelet migration. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 415:54–60. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Al-Shammari MS, Al-Ali R, Al-Balawi N,

Al-Enazi MS, Al-Muraikhi AA, Busaleh FN, Al-Sahwan AS, Al-Elq A,

Al-Nafaie AN, Borgio JF, et al: Type 2 diabetes associated variants

of KCNQ1 strongly confer the risk of cardiovascular disease among

the Saudi Arabian population. Genet Mol Biol. 40:586–590. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gómez-Úriz AM, Milagro FI, Mansego ML,

Cordero P, Abete I, De Arce A, Goyenechea E, Blázquez V,

Martínez-Zabaleta M, Martínez JA, et al: Obesity and ischemic

stroke modulate the methylation levels of KCNQ1 in white blood

cells. Hum Mol Genet. 24:1432–1440. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Abete I, Gómez-Úriz AM, Mansego ML, De

Arce A, Goyenechea E, Blázquez V, Martínez-Zabaleta MT,

González-Muniesa P, López De Munain A, et al: Epigenetic changes in

the methylation patterns of KCNQ1 and WT1 after a weight loss

intervention program in obese stroke patients. Curr Neurovasc Res.

12:321–333. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Harmer SC, Mohal JS, Royal AA, McKenna WJ,

Lambiase PD and Tinker A: Cellular mechanisms underlying the

increased disease severity seen for patients with long QT syndrome

caused by compound mutations in KCNQ1. Biochem J. 462:133–142.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu J, Wang F, Wu Y, Huang X, Sheng L, Xu

J, Zha B, Ding H, Chen Z and Sun T: Meta-analysis of the effect of

KCNQ1 gene polymorphism on the risk of type 2 diabetes. Mol Biol

Rep. 40:3557–3567. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Henninger N, Haussen DC, Kakouros N, Selim

M, Searls DE, Kumar S, Schlaug G and Caplan LR: QTc-prolongation in

posterior circulation stroke. Neurocrit Care. 19:167–175. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gallego-Fabrega C, Carrera C, Reny JL,

Fontana P, Slowik A, Pera J, Pezzini A, Serrano-Heras G, Segura T,

Bin Dukhyil AA, et al: PPM1A methylation is associated with

vascular recurrence in aspirin-treated patients. Stroke.

47:1926–1929. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|