Introduction

Diabetes is a global epidemic that affects 300

million individuals worldwide and is one of the primary threats to

human health, with a markedly increasing incidence (1). Hyperglycemia is a feature of diabetes

mellitus and can cause numerous complications, including heart

disease, cataracts, kidney disease and nerve damage (1,2). The

primary causes of all forms of diabetes include the loss of insulin

or insufficient quantities of insulin production/secretion from

pancreatic β-cells in the islets of Langerhans (3).

The pancreas is the second largest gland in the body

and is composed of endocrine and exocrine components (3). Exocrine islets form an important

digestive system that produces digestive enzymes, including

chymotrypsin, amylase and lipase, which are used to digest

proteins, and degrade carbohydrates and fats. Endocrine islets are

the source of several hormones, including insulin and glucagon

(4,5). Insulin, which is secreted by β cells

in the pancreas, is the most important metabolic hormone for

controlling blood glucose. Loss of islet β cells may lead to

diabetes and require therapeutic intervention.

Regenerative medicine is considered as a valuable

therapeutic approach that has gained increasing acceptance

worldwide. Devising potential strategies to develop

insulin-producing β-cells might result in profound effects for the

treatment of diabetes. Previous studies in fish (6), mice (7) and frogs (8) have demonstrated the differentiation

potential of multipotent stem cells (SCs) (5). Controlled differentiation of SCs,

including embryonic (9), pancreatic

(10) and bone marrow mesenchymal

(11) SCs, into functional

insulin-producing cells (IPCs) fulfills the requirement of

transplantable β cells. However, the protocol for the controlled

differentiation of SCs is not completely understood.

Pancreas-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (PMSCs)

are one of the types of mesenchymal cells isolated from pancreatic

tissues. Compared with other cells types, PMSCs are highly enriched

during vascular development, chemotaxis and wound healing (12). PMSCs also possess the ability to

decrease hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes model mice after

intrapancreatic injection (12).

PMSCs are a potential therapeutic agent for regenerative medicine

applications (13). Recently, Lee

et al (13) reported a

two-step induced protocol to transform porcine-derived mesenchymal

cells into insulin-producing cells; although the function of

induced cells was estimated, the biological characterization and

morphological alterations of the induced cells were not

described.

In the present study, Bama miniature pig-derived

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were selected as the experimental

cell source for a number of reasons: i) Swine are an appropriate

animal model for humans, as they possess a high degree of

similarity in tissue structure and genetics with humans (14); ii) MSCs with high proliferative

capacity can be transformed into various cell types and display a

vital role in regenerative medicine (15); and iii) SCs derived from the

pancreas are more easily differentiated into functional β cells

compared with other cells (3). The

present study described a novel protocol for generating pancreatic

islet β cells that may serve as a model to facilitate the study of

the mechanisms controlling islet cell neogenesis and may aid in the

identification of pharmaceutical targets to treat insulin-dependent

diabetes.

Materials and methods

PMSC isolation, culture and

purification

All animal procedures were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chinese Academy of

Agricultural Sciences (approval no. IAS 2018–19, Beijing, China).

The 2–3-month-old Wuzhishan miniature pig (Sus scrofa; also

known as Bama miniature pigs) was provided by the Animal Husbandry

Experimental Base, Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of

Agricultural Sciences (16). The

animals were sacrificed through overdose of ketamine (100 mg/kg;

cat. no. 087K1253; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and xylazine (25

mg/kg; cat, no. KH070901; Hengrui Co.) (16). The pancreas was removed from each

miniature pig embryo (n=3). After thoroughly washing with PBS

buffer, tissue sections were dissected into 1-mm3 thick

segments and isolated via collagenase digestion under sterile

conditions. Tissues were digested with 5.5 mg/ml collagenase P

(Roche Diagnostics) for 60 min at 37°C with gentle agitation every

10 min. Following digestion, cells were neutralized with RPMI-1640

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell suspension was

filtered through a 74-µm mesh sieve and then centrifuged at 225 × g

for 15 min at room temperature. Cell pellets were resuspended with

RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells (1.5×106)

were seeded into plates and incubated at 37°C with 5%

CO2. Following incubation for 3–4 h, 104

non-adherent cells were removed and reseeded in a new plate. Cells

were incubated with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml

human-derived fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; PeproTech, Inc.) and

20 ng/ml human-derived epidermal growth factor (EGF; PeproTech,

Inc.) at 37°C. After 12 h, 100s of cells started growing with a

spindle shape. When the cells reached 80–90% adherence, they were

digested with 0.125% trypsin and considered as passage 1. Passage

4, passage 13 and passage 18 cells were obtained by the same

method. PMSCs were purified by the different adhesion time method

(17). According to the preliminary

experiment, PMSCs displayed a shorter adhesion time compared with

other cells types, thus PMSCs could be purified after the third

passage. In addition, PMSCs should be mesenchymal cell specific

marker Vimentin positive and display fibroblast-like morphology;

these were checked to assess the purity of isolated PMSCs.

Contaminating cells, such as blood and duct cells, displayed a

different adherence time and could be excluded by passaging.

Growth kinetics

Cells from passage 3, 8 and 16 were seeded

(1×104 cell/well) into 24-well plates. The cell

suspension was absorbed and dropped onto the edge of the cell

counting plate, and the mean value of four large squares was

calculated. Cell counting was repeated three times to obtain a mean

value for each large square. The cell count (cells/ml) was

calculated as follows: The mean cell number ×104. Cells

were counted every day for 7 days. The population doubling time

(PDT) was calculated according to the following formula:

PDT=(t-t0) xlog2/(log Nt-log N0),

where t0 is the starting time, t is the termination

time, N0 is the initial cell number and Nt is the

ultimate cell number.

Colony-formation assay

Cells from passage 3, 8 and 14 were seeded

(1×104 cell/well) into 24-well plates and cultured for 4

days. Then, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30

min at room temperature and stained with GIMSA (cat. no. C0133,

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the number of colony-forming units was

counted to calculate the colony-forming rate (%) according to the

following formula: (Number of colony-forming units/number of seeded

cells) ×100. The experiment was repeated three times to calculate

the mean value. The light microscope was used for images at ×4

magnification.

Immunofluorescence staining

Purified PMSCs were seeded into 6-well plates. At

70% confluence, cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and

permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

for 20 min in room temperature. Following blocking with 10% normal

goat serum (1:10; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) for 30 min at room

temperature, cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in 3% BSA

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) supplemented with the following primary

antibodies: Anti-pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (Pdx1; 1:200;

cat. no. ab47267; Abcam), anti-Vimentin (1:200; cat. no. ab8978;

Abcam), anti-neurogenin 3 (Ngn3; 1:200; cat. no. bs-0922R; Beijing

Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), anti-Nestin (1:200; cat. no.

ab221660; Abcam) and anti-CD45 (1:200; cat. no. ab10558; Abcam).

Following washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with a

FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody (1:200; cat.

no. ZF-0314; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) or anti-mouse Alexa Fluor

secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. sc-516608; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc) at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. Cells

were washed three times in the dark and then incubated with 1 µg/ml

DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 15 min in room temperature.

Stained cells were visualized and counted in eight randomly

selected non-overlapping fields of view using a TE-2000-E inverted

fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation). For the control group,

PBS was used in place of primary antibodies. Samples were assessed

in triplicate.

Flow cytometry

Differentiated cell clusters or PMSCs both at a

number of 106 were dispersed into single-cell

suspensions by incubation with trypsin for 1 min at 37°C. Cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature,

washed with PBS and blocked with 1% normal goat serum for 20 min at

room temperature. PMSCs were incubated with anti-CD73 (1:200; cat.

no. ab175396; Abcam), anti-CD90 (1:200; cat. no. ab222781; Abcam)

and anti-CD34 (1:200; cat. no. 81289; Abcam) primary antibodies for

biological characterization at 4°C overnight. IPCs and PMSCs were

resuspended in PBS with anti-insulin (1:200; cat. no. ab181547;

Abcam) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Following washing twice with

PBS, cells were incubated at room temperature with FITC-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; cat. no. bs-40295G-HRP; BIOSS) and

goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor IgG (1:200; cat. no. bs-40296-HRP;

BIOSS) secondary antibodies for 2 h. For the control group, cells

were only incubated with the secondary antibody and were not

incubated with specific primary antibodies. Following washing,

cells were analyzed using a Beckman Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer

(Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and Flow software (Beckman CXP 2.1; Beckman

Coulter, Inc.). Samples were assessed in triplicate. The assay was

conducted in 60-mm dishes.

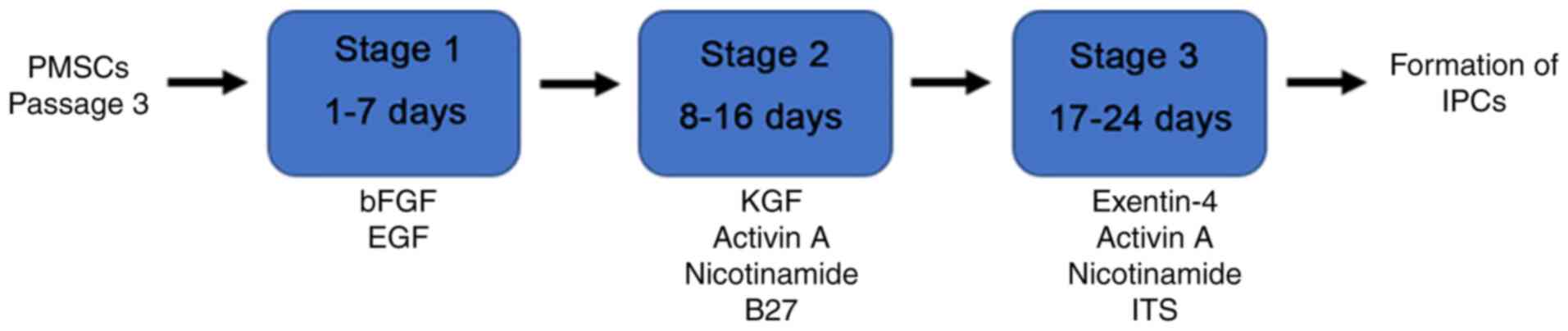

Transdifferentiation of PMSCs into

IPCs in vitro

At passage 3, PMSCs were transdifferentiated into

IPCs in vitro according to the protocol presented in

Fig. 1. Firstly, PMSCs were

incubated in medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml bFGF and 20 ng/ml

EGF for 7 days. Subsequently, cells were transferred into medium

containing 10 ng/ml keratinocyte growth factor (KGF; PeproTech,

Inc.), 10 ng/ml Activin A (PeproTech, Inc.), 10 mmol/l nicotinamide

(PeproTech, Inc.) and 2% B27 supplement (PeproTech, Inc.) for 9

days. Cells were transferred into medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml

Exendin-4 (PeproTech, Inc.), 10 ng/ml Activin A, 10 mmol/l

nicotinamide (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1 g/l

insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in

stage 3. All culture mediums were replaced every 2–3 days. The

control group was cultured in medium without any supplementation.

Cells were observed using an inverted light microscope every

day.

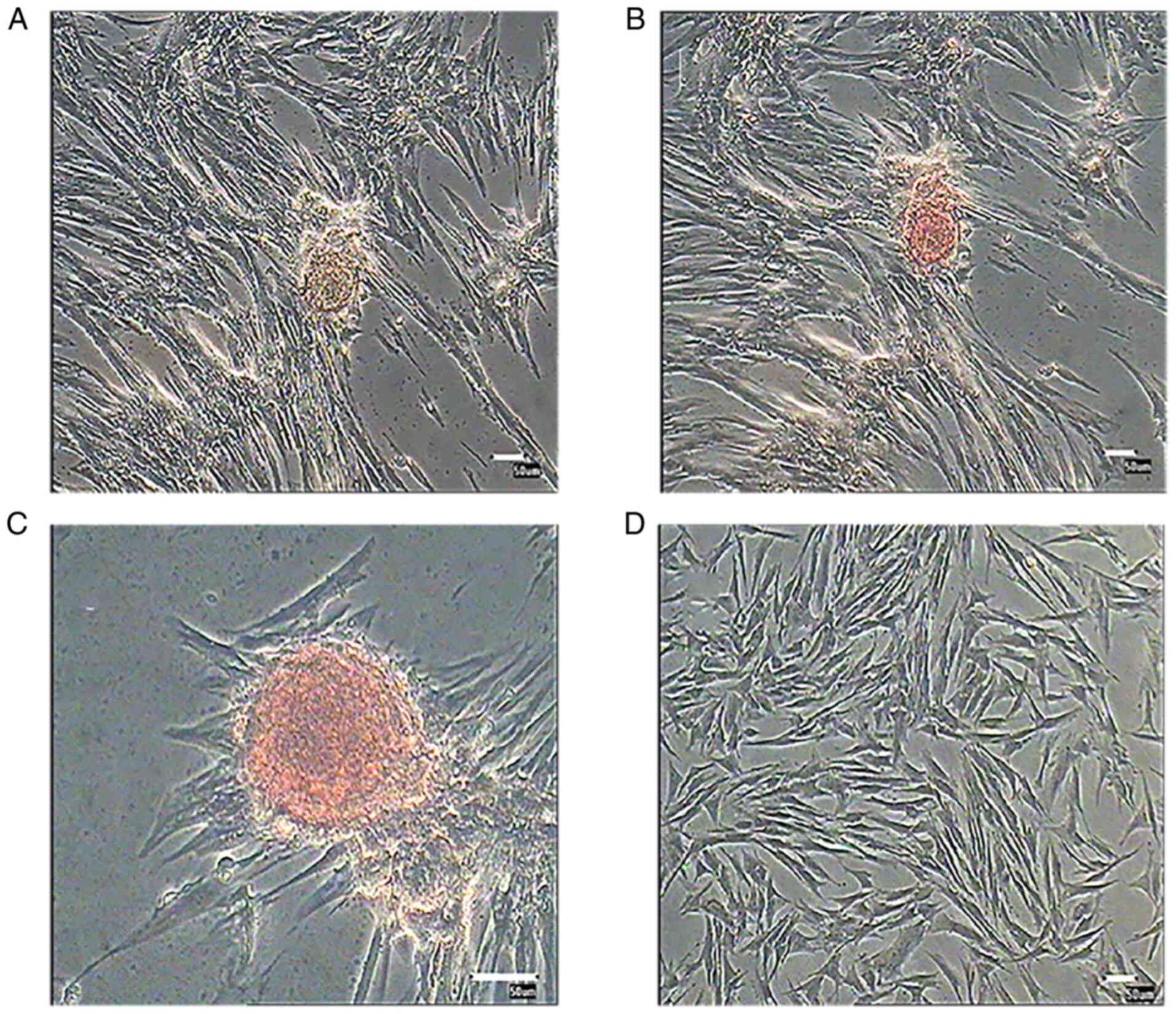

Dithizone (DTZ) staining

Following induction, cells were washed with PBS,

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and

stained with DTZ (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) staining solution for

30 min at room temperature. Stained cells were observed using a

light microscope. The staining protocol was based on a study

conducted by Shiroi et al (18). Samples were assessed in triplicate.

The assay was conducted in 60-mm dishes.

Immunofluorescence staining assays of

IPCs markers

According to the aforementioned protocol,

immunofluorescence staining was performed using primary antibodies

targeted against the following: Insulin (1:200; cat. no. ab9823;

Abcam), glucagon (1:200; cat. no. ab189279; Abcam), C-peptide

(1:200; cat. no. ab82696; Abcam) and NK6 homeobox 1 (Nkx6.1; 1:200;

cat. no. ab251565; Abcam). The nuclear was stained with DAPI (cat.

no. C1002; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 20 min at room

temperature. Samples were assessed in triplicate. The assay was

conducted in 60-mm dishes.

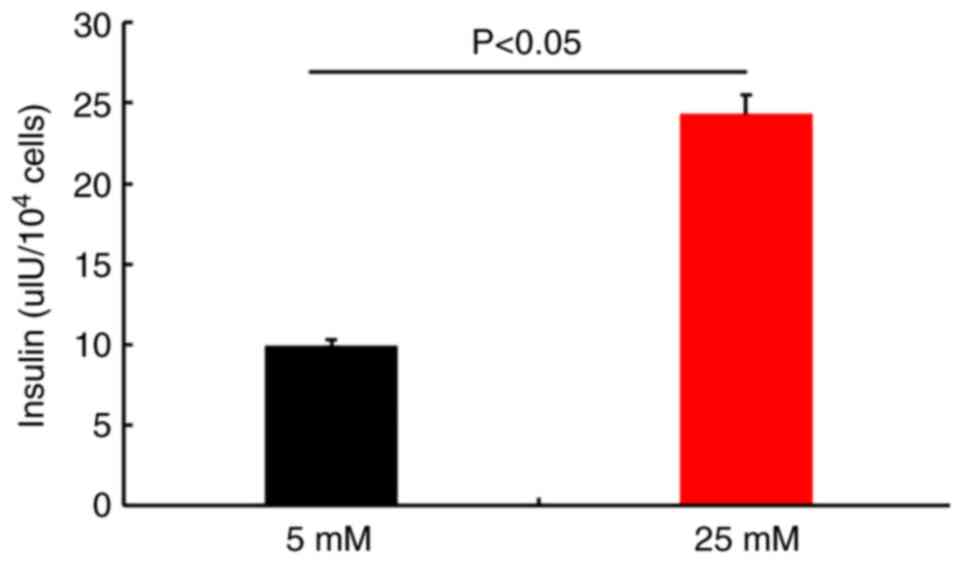

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

(GSIS)

Following washing with PBS, differentiated IPCs were

pre-cultured in low-glucose (2 mM) buffer for 1 h to remove

residual insulin. Cell clusters were washed twice with PBS and then

incubated in low-glucose (5 mM) buffer for 30 min at 37°C. The

supernatant was collected. Subsequently, cell clusters were washed

twice in PBS and then incubated in high-glucose (25 mM) buffer for

30 min at 37°C. The supernatant was collected via centrifugation at

339 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Cell clusters were

dispersed into single cells using trypsin and the cell number was

counted. Undifferentiated cell samples were used as controls.

Supernatant samples containing secreted insulin were processed

using the mouse insulin ELISA kit (cat. no. 0740; Pro Lab Marketing

Pvt. Ltd.), which displays 0.019 ng/ml super sensitivity. The

protocol was modified from the method described by Pagliuca et

al (19) and Bai et al

(20). Samples were assessed in

triplicate. The assay was conducted in 60-mm dishes. The experiment

was repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons among multiple groups were analyzed

using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test in

GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Comparisons between two

groups were analyzed using an unpaired Student's t-test.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

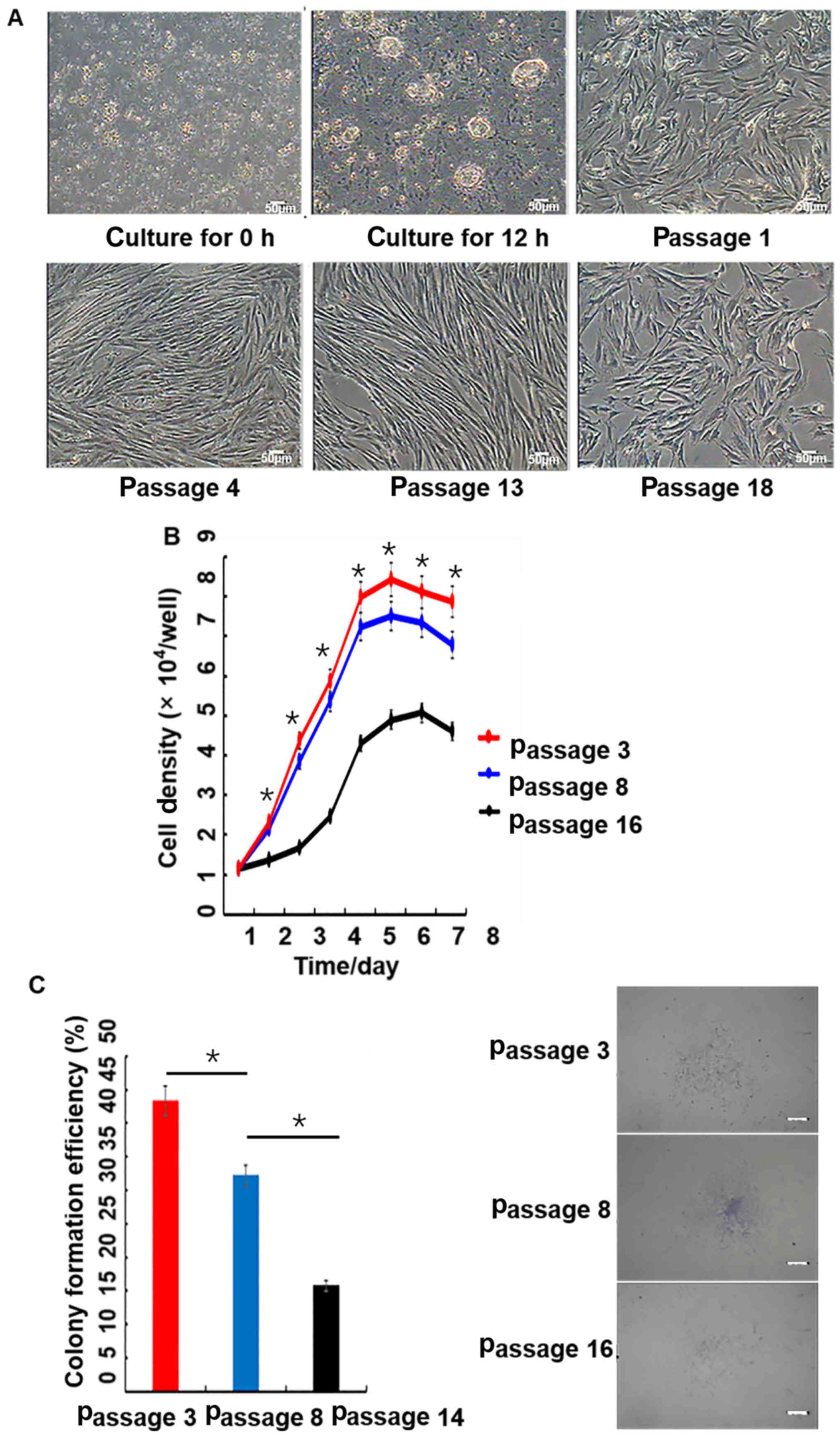

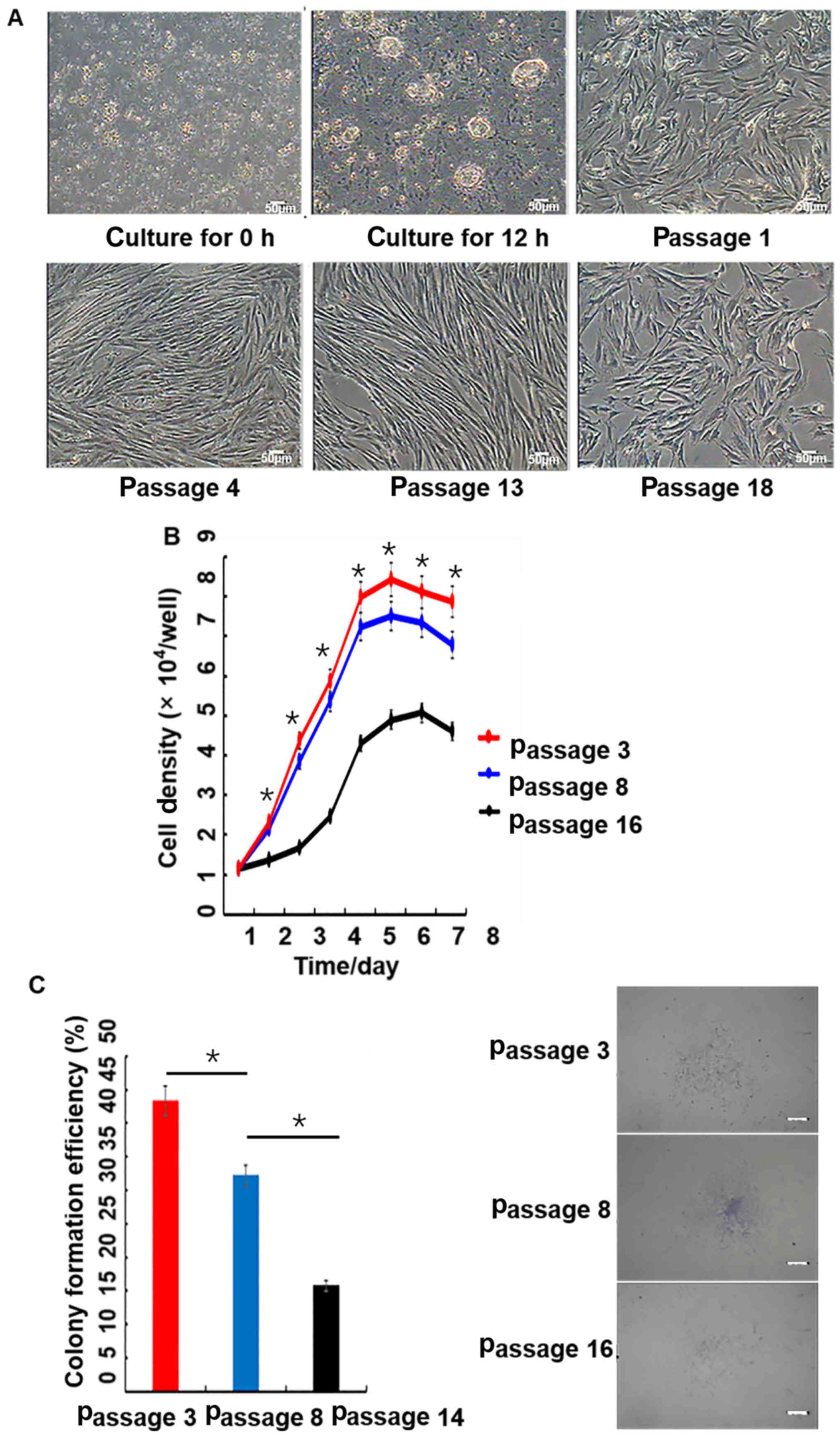

Morphological observation of

PMSCs

Following culture for 12 h, only a small number of

cells were attached to the plate. Adherent cells gradually

proliferated. In primary cultures, PMSCs were mixed with epithelial

cells and other different types of cells. At passage 4, PMSCs were

purified and displayed fibroblast-like morphology, with long

spindle-like and polygon-like cell features. At passage 18, PMSCs

rapidly expanded and then cell proliferation slowed down, resulting

in flattened cells with a lack of three-dimensional structure that

displayed signs of senescence (Fig.

2A).

| Figure 2.Morphology, growth curves and

colony-forming efficiency of porcine PMSCs in vitro. (A)

Morphology of cells at 0 and 12 h, as well as passages 1, 4, 13 and

18; scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Growth curves of PMSCs. The growth curves

of passage 3, 8 and 16 PMSCs were all sigmoidal. The growth rate of

passage 16 cells was significantly slower than younger passage

cells. The growth curves consisted of latent, logarithmic and

plateau phases. The population doubling time, which was calculated

from the growth curve, was ~48 h. Passage 3 has a significant

difference with passage 16. (C) Colony-formation assay. Colony

formation rates of PMSCs at passage 3, 8 and 14. Scale bar, 50 µm.

*P<0.05. PMSC, pancreas-derived mesenchymal stromal cell. |

Growth kinetics

The growth curve of PMSCs displayed a typical ‘S’

shape, cells underwent latency, logarithmic and plateau phases

(Fig. 2B). However, passage 16

cells proliferated significantly slower compared with passage 3 and

8 cells. Based on the growth curve, the PDT of PMSCs was estimated

to be ~48 h.

Colony-forming assay

At passage 3, 8 and 14, the colony-forming ability

of PMSCs was detected by microscopy. Colony-forming efficiencies

were 43.57, 32.48 and 16.00% at passage 3, 8 and 14, respectively

(Fig. 2C).

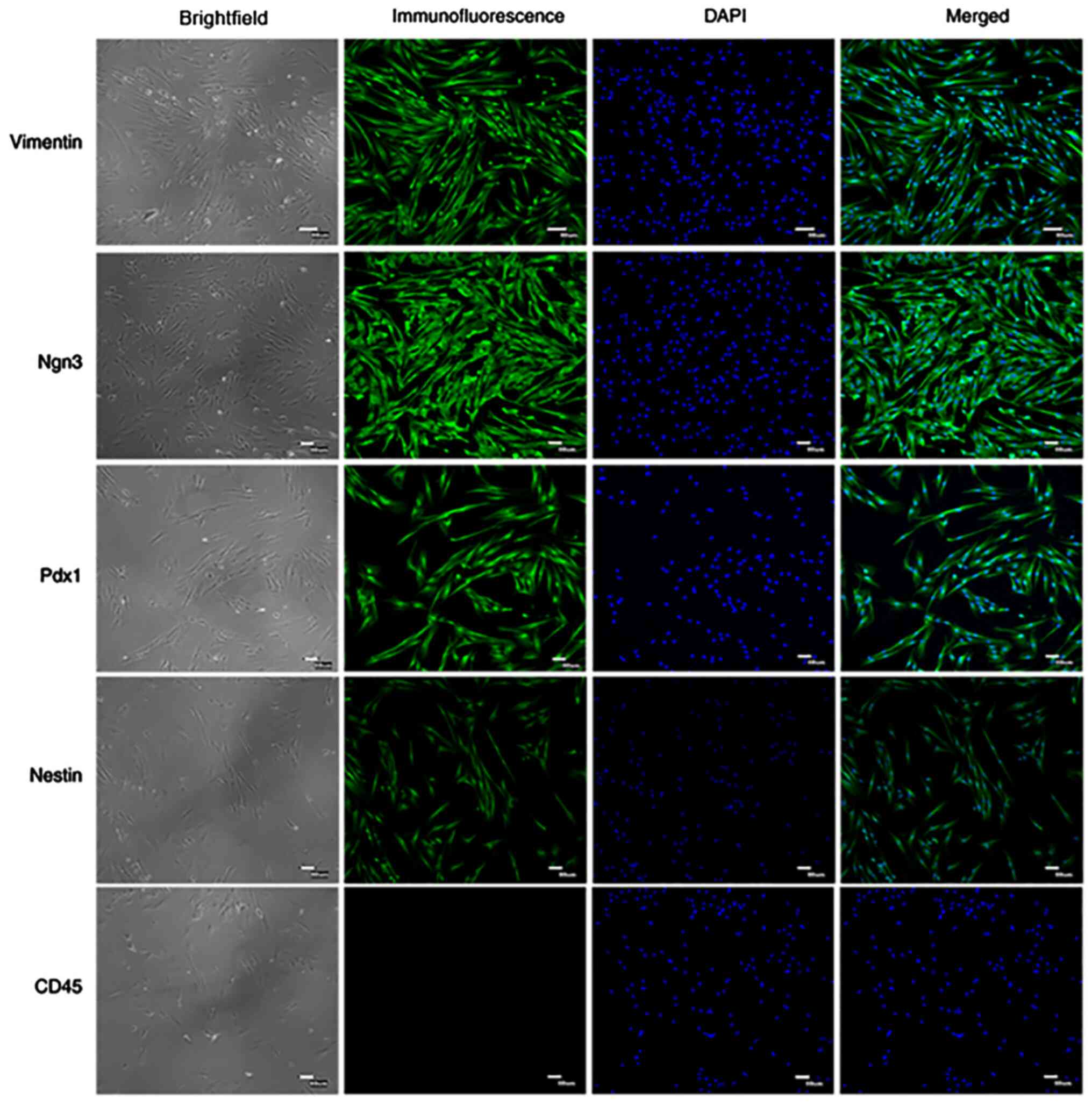

Immunofluorescence staining detection

of PMSC surface antigens markers

Specific surface markers, including Vimentin,

Nestin, Ngn3, Pdx1 and CD45, were detected by immunofluorescence

staining in passage 4 cells (Fig.

3). The results demonstrated that PMSCs positively expressed

Vimentin, Nestin, Ngn3 and Pdx1, but did not express CD45. Vimentin

is an important marker of mesenchymal cells (17) and the results demonstrated that

Vimentin was highly expressed in PMSCs.

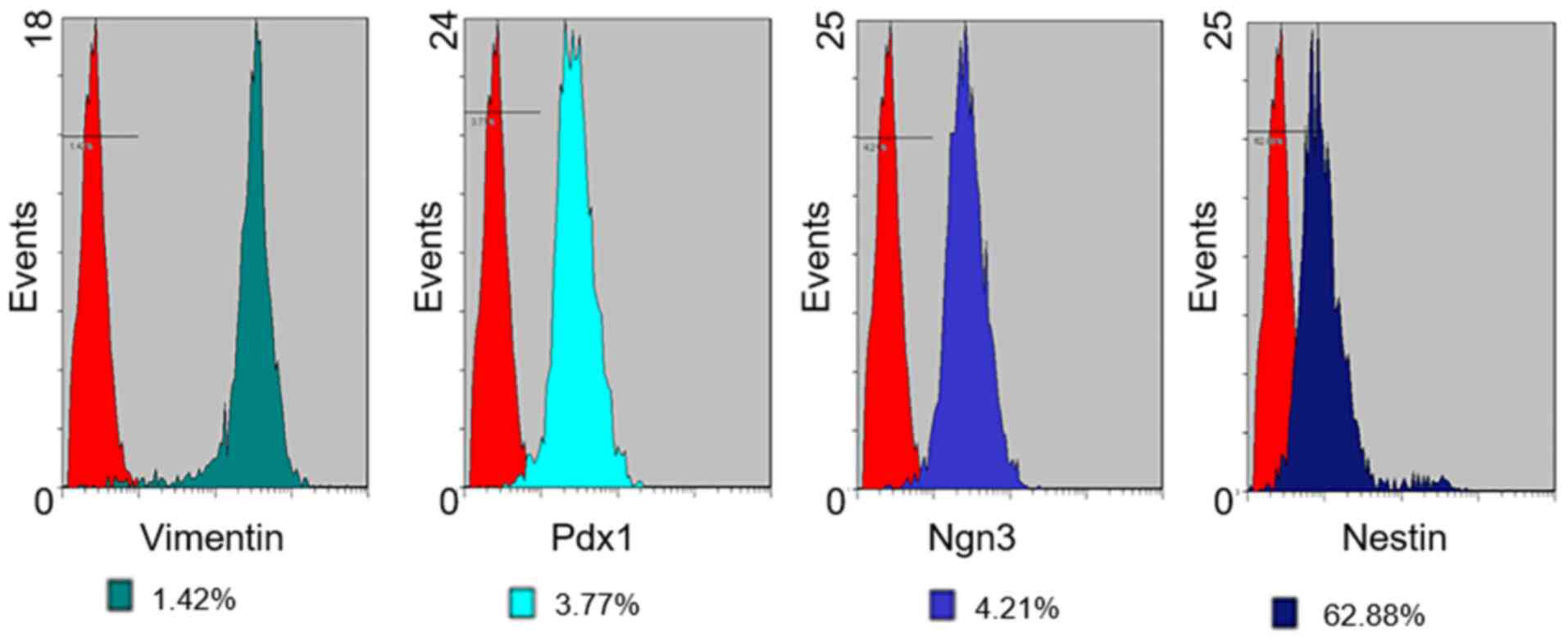

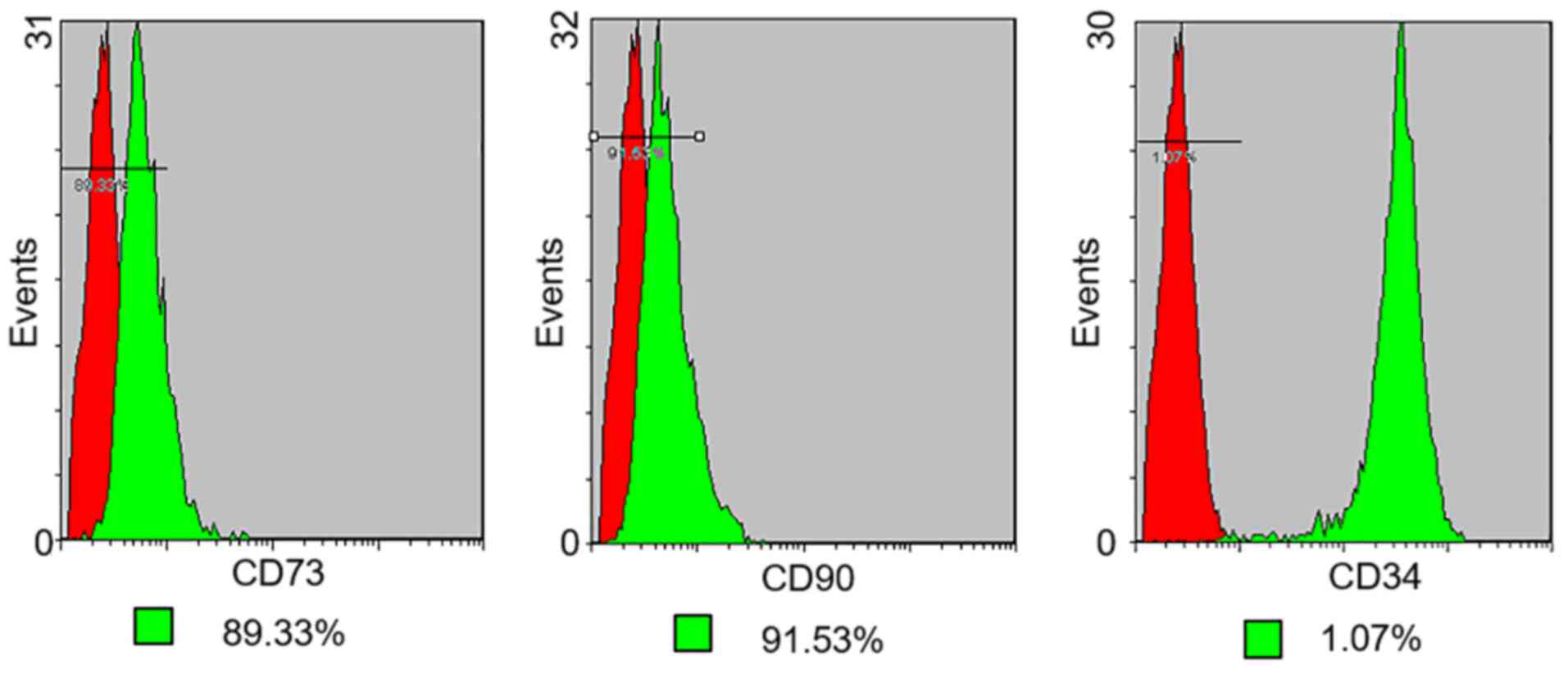

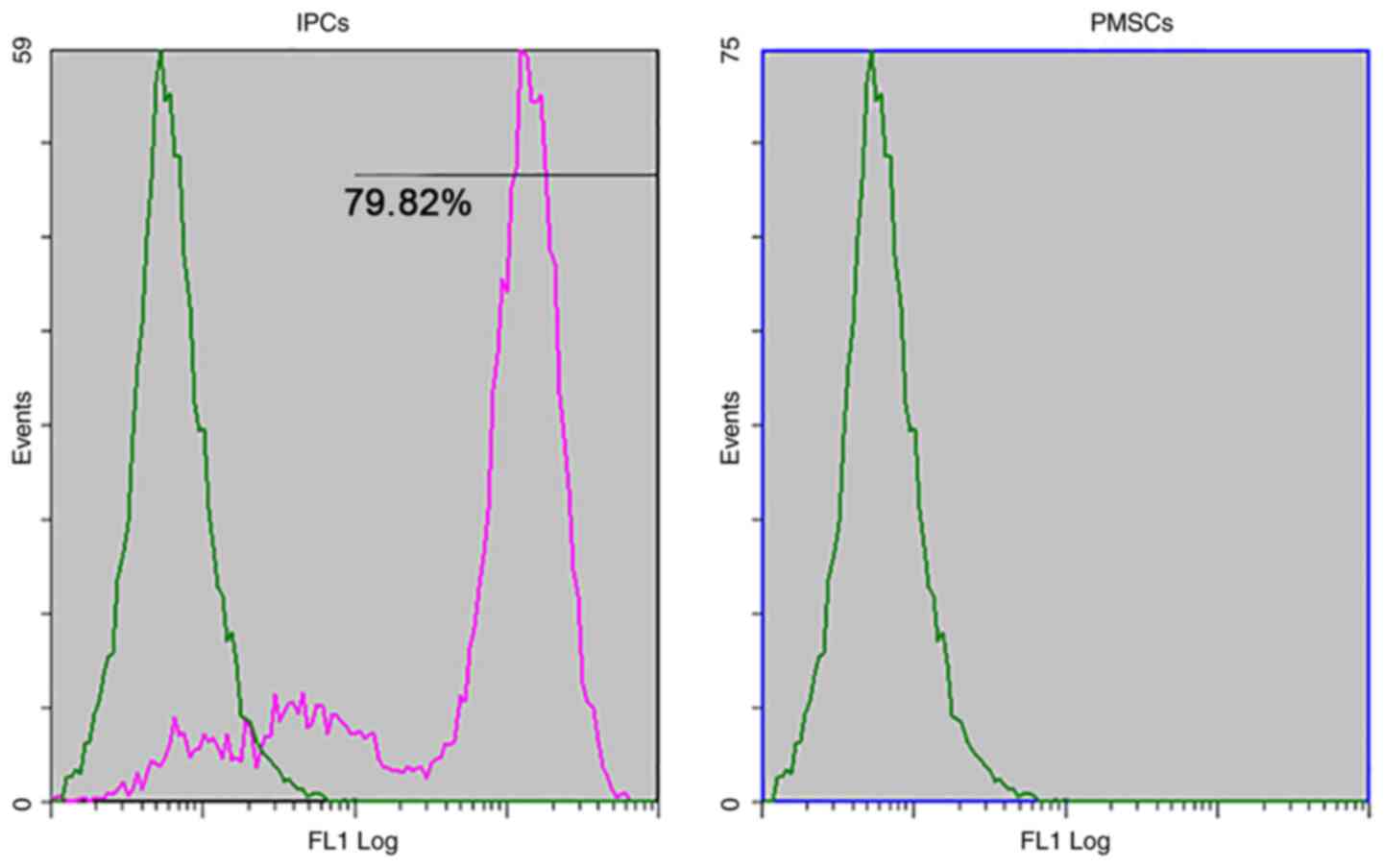

Flow cytometry

The expression of cell surface antigens by PMSCs in

early passage cells (up to passage 3) was analyzed by flow

cytometry (Figs. 4 and 5). Cultured PMSCs were composed of a

single phenotypic population. The positive rates of Vimentin, Pdx1,

Ngn3, Nestin, CD73, CD90 and CD34 were 98.58, 96.23, 95.79, 37.12,

89.33, 91.53 and 1.07%, respectively, which were calculated by 1

minus the rate of control rate.

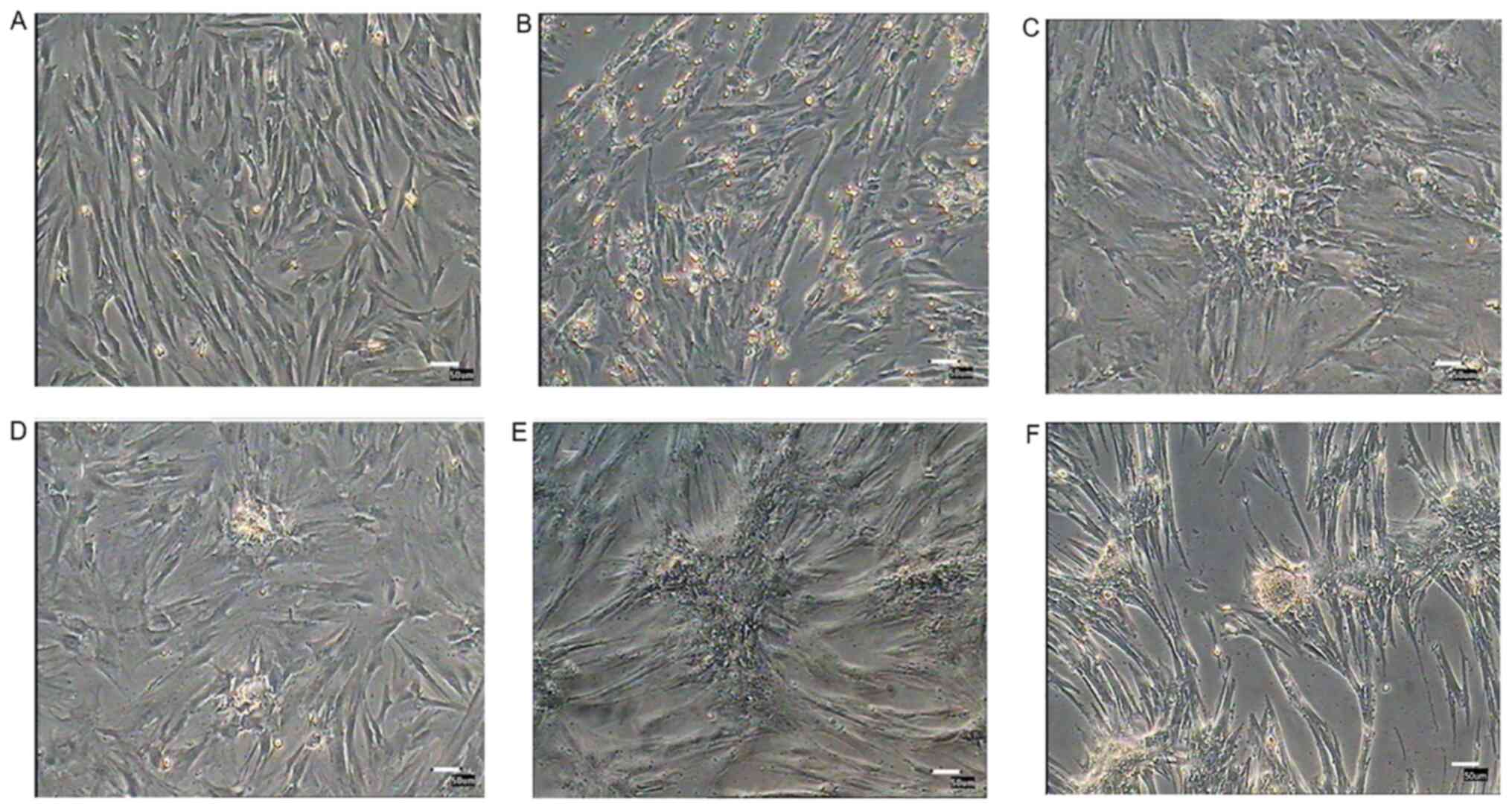

Morphological alterations and DTZ

staining of PMSC-derived IPCs

PMSCs at passage 3 were cultured in differentiation

medium for 3 weeks. Induced cells were observed daily for

morphological alterations. After 12 days, a number of small cell

clusters formed and the number of cell clusters increased as cells

differentiated (Fig. 6). After 3

weeks induction, cell clusters were stained with DTZ (Fig. 7) and showed a scarlet color.

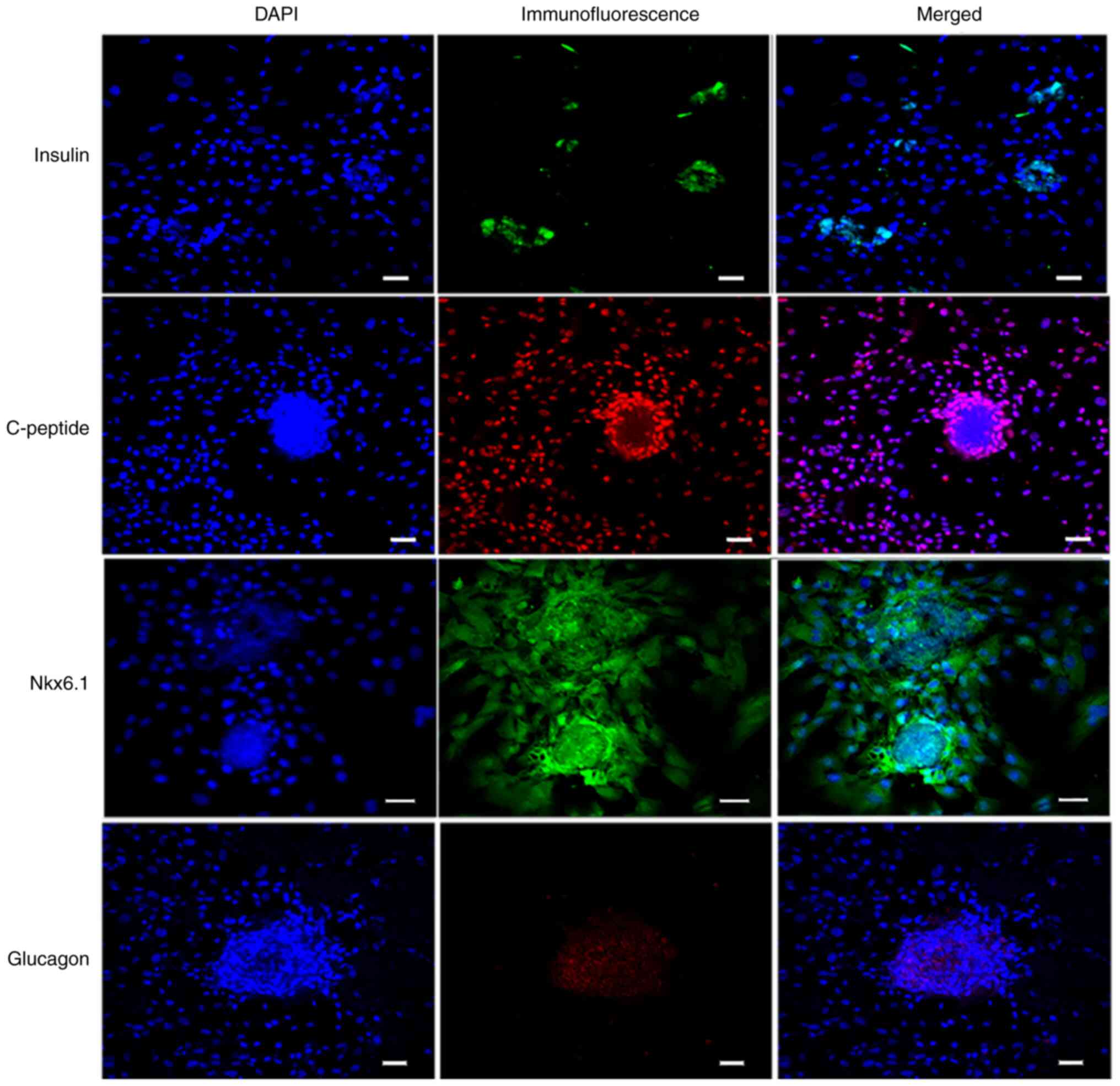

Immunofluorescence staining assays of

IPC markers

Differentiated cells were analyzed by performing an

immunofluorescence staining assay (Fig.

8). The differentiated islet-like cell clusters expressed

insulin and Nkx6.1, whereas the undifferentiated PMSCs around the

cell clusters did not express insulin and Nkx6.1. Glucagon staining

suggested that the differentiated cell clusters were monohormonal

cells. IPCs were positive for insulin and C-peptide, which are

stoichiometric byproducts of proinsulin processing (20). The results suggested that PMSCs were

differentiated into IPCs using the optimized three-step culture

procedure.

GSIS

Insulin secretion was evaluated by performing

ELISAs. The results demonstrated that newly generated IPCs secreted

insulin in response to glucose stimulation (Fig. 9). The differentiation rate of PMSCs

was determined by flow cytometry. The results demonstrated that

79.82±1.36% of the total number of differentiated cells were

insulin-positive (Fig. 10), which

suggested that PMSCs had differentiated into functional IPCs.

Discussion

SCs have multiple differentiation potentials and

display self-renewal capacities; under certain conditions, SCs

significantly proliferate and differentiate into specific lineages

(21). MSCs derived from the

mesoderm can also differentiate into multiple mesodermal and

nonmesodermal cell lineages in vitro (21,22).

Owing to their high proliferative ability, lack of adverse

influence from allogeneic antigens and autoantigens, and teratoma

formation abilities, MSCs are a promising source for clinical

research (23). The differentiation

of MSCs into IPCs from bone marrow- (24–26),

umbilical cord blood- (27,28), adipose- (29,30)

and placenta-derived (31) MSCs has

been described.

The present study described an optimized three-step

induction protocol, which was used to obtain IPCs from porcine

PMSCs. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that SCs present in

pancreatic ducts, islets and acini display a specific potential for

differentiation (13). Compared

with the two-step induction protocol (13), the clear morphology of islet-like

cells was a notable benefit observed with the three-step protocol

used in the present study. In addition, pancreatic SCs are derived

from pancreas ductal tissues and display a cobblestone like

morphology, whereas PMSCs are derived from acinar tissue and

display a fibroblast-like morphology (20). PMSCs can be isolated using a simpler

protocol and display a higher proliferation ability than pancreas

stem cells (21). The present study

induced PMSC transformation into IPCs using a three-step protocol.

Firstly, cell growth in a favorable microenvironment was sustained

by adding bFGF and EGF, which promoted cell development. Secondly,

Activin A, B27 KGF and nicotinamide were used to stimulate PMSC

neural and entoderm differentiation. Finally, ITS, Activin A,

nicotinamide and exendin-4 were added to the culture medium to

sustain entoderm differentiation and to stimulate cells into an

islet-like morphology. In addition, compared with other adult SCs,

PMSCs are more likely to form IPCs (21), which suggested that they may serve

as an ideal candidate for diabetes therapy.

The present study demonstrated the successful

expansion of porcine PMSCs in vitro and the differentiation

into IPC clusters after 3 weeks induction; PMSCs aggregated and

formed islet-like cell clusters that were DTZ-positive and

expressed specific markers of β cells. The GSIS experiment results

indicated that the differentiated cells secreted insulin in

response to glucose alterations. The weak expression of insulin

indicated that the protocol requires further revision. Thus, the

function of induced IPCs with the three-step protocol requires

additional investigation in vivo using animal models and

other MSC types, such as bone marrow, adipose and other cells in

vitro.

The results of the present study indicated that

PMSCs displayed a strong self-renewal capacity and expressed the

surface markers of MSCs. The present study also provided evidence

for the generation of functional IPCs from PMSCs using an optimized

three-step protocol. However, the present study only investigated

the function of IPCs in vitro and lacked investigation using

an in vivo animal model. In addition, the three-step

protocol required multiple factors and lasted for 3 weeks; thus,

attempts should be made to simplify and optimize the protocol

further. The application of the three-step protocol in other cells

types, such as MSCs, should also be investigated in the future as

it may be of great significance for the treatment of diabetes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by The National

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31201765, 31272403 and

31472064) and the earmarked fund for Modern Agri-industry

Technology Research System (grant no. nycytx-40-01).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SZ and QW performed the experiments, contributed to

data analysis, drafted the manuscript and were responsible for the

authenticity of data. HJ and HL revised the draft manuscript in the

Results and Discussion sections and also acquire the raw data. QY

and JY performed the data analysis. WG provided the final version

publication of the manuscript, designed the project and also

interpretated the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chinese Academy of

Agricultural Sciences (approval no. IAS 2018-19).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I,

Beagley J, Linnenkamp U and Shaw JE: Global estimates of diabetes

prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin

Pract. 103:137–149. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

De Paoli M and Werstuck GH: Role of

estrogen in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of

clinical and preclinical data. Can J Diabetes. 44:448–452. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhou Q and Melton DA: Pancreas

regeneration. Nature. 557:351–358. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pan FC and Brissova M: Pancreas

development in humans. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes.

21:77–82. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bakhti M, Böttcher A and Lickert H:

Modelling the endocrine pancreas in health and disease. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 15:155–171. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fathi E, Farahzadi R and Sheikhzadeh N:

Immunophenotypic characterization, multi-lineage differentiation

and aging of zebrafish heart and liver tissue-derived mesenchymal

stem cells as a novel approach in stem cell-based therapy. Tissue

Cell. 57:15–21. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Arnold K, Sarkar A, Yram MA, Polo JM,

Bronson R, Sengupta S, Seandel M, Geijsen N and Hochedlinger K:

Sox2(+) adult stem and progenitor cells are important for tissue

regeneration and survival of mice. Cell Stem Cell. 9:317–329. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gross JB and Hanken J: Use of fluorescent

dextran conjugates as a long-term marker of osteogenic neural crest

in frogs. Dev Dyn. 230:100–106. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yu F, Wei R, Yang J, Liu J, Yang K, Wang

H, Mu Y and Hong T: FoxO1 inhibition promotes differentiation of

human embryonic stem cells into insulin producing cells. Exp Cell

Res. 362:227–234. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tan J, Liu L, Li B, Xie Q, Sun J, Pu H and

Zhang L: Pancreatic stem cells differentiate into insulin-secreting

cells on fibroblast-modified PLGA membranes. Mater Sci Eng C Mater

Biol Appl. 97:593–601. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Daryabor G, Shiri EH and Kamali-Sarvestani

E: A simple method for the generation of insulin producing cells

from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol

Anim. 55:462–471. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cooper TT, Sherman SE, Bell GI, Ma J,

Kuljanin M, Jose SE, Lajoie GA and Hess DA: Characterization of a

Vimentin high/Nestinhigh proteome and tissue

regenerative secretome generated by human pancreas-derived

mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 38:666–682. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lee S, Moon S, Oh JY, Seo EH, Kim YH, Jun

E, Shim IK and Kim SC: Enhanced insulin production and

reprogramming efficiency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from

porcine pancreas using suitable induction medium.

Xenotransplantation. 26:e124512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Iqbal MA, Hong K, Kim JH and Choi Y:

Severe combined immunodeficiency pig as an emerging animal model

for human diseases and regenerative medicines. BMB Rep. 52:625–634.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fu X, Liu G, Halim A, Ju Y, Luo Q and Song

AG: Mesenchymal stem cell migration and tissue repair. Cells.

8:7842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xu J, Yu L, Guo J, Xiang J, Zheng Z, Gao

D, Shi B, Hao H, Jiao D, Zhong L, et al: Generation of pig induced

pluripotent stem cells using an extended pluripotent stem cell

culture system. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:1932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kleeblatt J, Schubert JK and Zimmermann R:

Detection of gaseous compounds by needle trap sampling and direct

thermal-desorption photoionization mass spectrometry: Concept and

demonstrative application to breath gas analysis. Anal Chem.

87:1773–1781. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shiroi A, Yoshikawa M, Yokota H, Fukui H,

Ishizaka S, Tatsumi K and Takahashi Y: Identification of

insulin-producing cells derived from embryonic stem cells by

zinc-chelating dithizone. Stem Cells. 20:284–292. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gürtler M, Segel

M, Van Dervort A, Ryu JH, Peterson QP, Greiner D and Melton DA:

Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell.

159:428–439. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bai C, Gao Y, Zhang X, Yang W and Guan W:

MicroRNA-34c acts as a bidirectional switch in the maturation of

insulin-producing cells derived from mesenchymal stem cells.

Oncotarget. 8:106844–106857. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu M and Han ZC: Mesenchymal stem cells:

biology and clinical potential in type 1 diabetes therapy. J Cell

Mol Med. 12:1155–1168. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang S, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Liu S, Zhao C,

Guan W and Zhao Y: Therapeutic potential of Bama miniature pig

adipose stem cells induced hepatocytes in a mouse model with acute

liver failure. Cytotechnology. 70:1131–1141. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Venkatesh K and Sen D: Mesenchymal stem

cells as a source of dopaminergic neurons: A potential cell based

therapy for parkinson's disease. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther.

12:326–347. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gabr MM, Zakaria MM, Refaie AF, Khater SM,

Ashamallah SA, Ismail AM, El-Halawani SM and Ghoneim MA:

Differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

into insulin-producing cells: Evidence for further maturation in

vivo. Biomed Res Int. 2015:5758372015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li X, Huang H, Liu X, Xia H and Li M: In

vitro generation of insulin-producing cells from the neonatal rat

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za

Zhi. 31:346–349. 2015.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang S, Zhao C, Liu S, Wang Y, Zhao Y,

Guan W and Zhu Z: Characteristics and multi-lineage differentiation

of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells derived from the Tibetan

mastiff. Mol Med Rep. 18:2097–2109. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Van Pham P, Thi-My Nguyen P, Thai-Quynh

Nguyen A, Minh Pham V, Nguyen-Tu Bui A, Thi-Tung Dang L, Gia Nguyen

K and Kim Phan N: Improved differentiation of umbilical cord

blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells

by PDX-1 mRNA transfection. Differentiation. 87:200–208. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tsai PJ, Wang HS, Shyr YM, Weng ZC, Tai

LC, Shyu JF and Chen TH: Transplantation of insulin-producing cells

from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of

streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Biomed Sci. 19:472012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhou H, Yang J, Xin T, Li D, Guo J, Hu S,

Zhou S, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Han T and Chen Y: Exendin-4 protects

adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from apoptosis induced by

hydrogen peroxide through the PI3K/Akt-Sfrp2 pathways. Free Radic

Biol Med. 77:363–375. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Karaoz E, Okcu A, Ünal ZS, Subasi C,

Saglam O and Duruksu G: Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal

cells efficiently differentiate into insulin-producing cells in

pancreatic islet microenvironment both in vitro and in vivo.

Cytotherapy. 15:557–570. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kadam S, Muthyala S, Nair P and Bhonde R:

Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells and islet-like cell

clusters generated from these cells as a novel source for stem cell

therapy in diabetes. Rev Diabet Stud. 7:168–182. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|